Summary

Jail Ogaden is unthinkable. From the moment you are put there until the moment you are released, you do not know if you are alive or dead. You are tortured and humiliated day and night, you are starved, [and] you can’t sleep because there’s so many people.

—42-year-old Mohamed who spent five years without charge in Jail Ogaden, August 2017

In the heart of the eastern city of Jijiga, just five minutes from the University, lies one of the most notorious detention centers in Ethiopia. Jail Ogaden, officially known as Jijiga Central Prison, is home to thousands of prisoners, who are brutalized and neglected. Many have never been charged or convicted of any crime.

Former prisoners described a horrific reality of constant abuse and torture, with no access to adequate medical care, family, lawyers, or even, at times, food. Officials stripped naked and beat prisoners and forced them to perform humiliating acts in front of the entire prison population, as punishment and to instill shame and fear. In overcrowded cells, head prisoners, called kabbas, beat and harassed prisoners at night during interrogations, passing notes on to prison leaders who then chose some for further punishment. The purpose of the torture and humiliation was to coerce prisoners to “confess” to membership in the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), a banned opposition group.

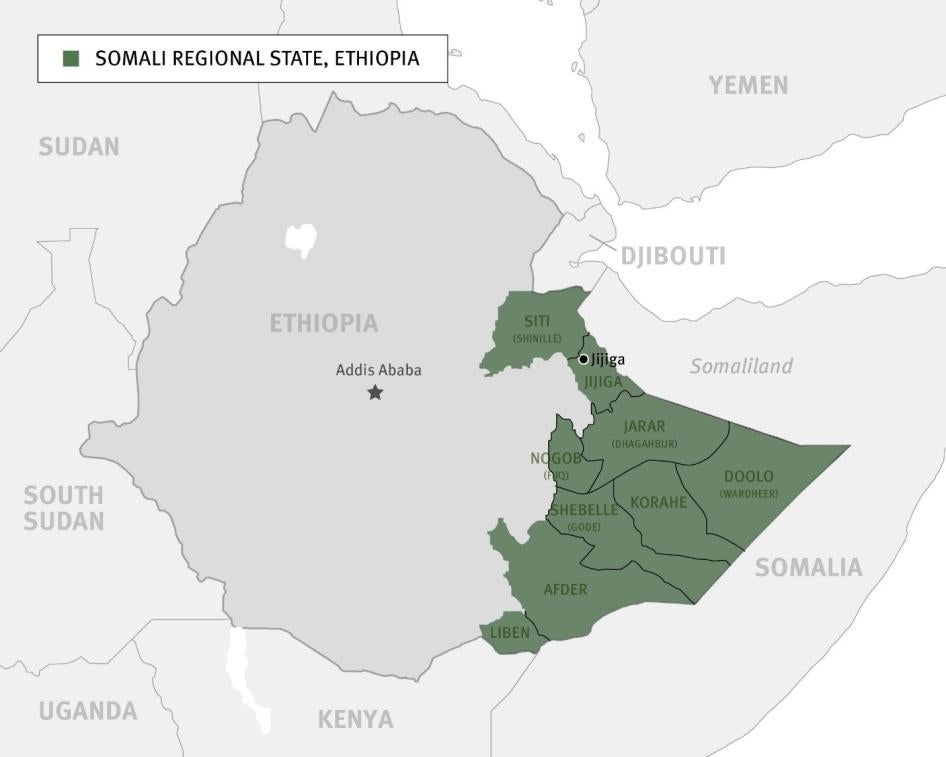

This report, based on almost 100 interviews, including 70 former prisoners of Jail Ogaden, documents torture and other serious abuses, including rape, long term arbitrary detention, and horrific detention conditions in Jail Ogaden in Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State (Somali Region) between 2011 and early 2018. Interviewees also included government officials and members of Somali Region security forces.

Many of the former prisoners interviewed said they saw people dying in their cells after being tortured by officials. Female former prisoners told of rape. Prison guards and the notorious Liyu police [“special” police in Amharic], brutalized prisoners, at the behest of regional authorities. The prison is subject to almost no meaningful scrutiny or oversight.

The cycle of torture, humiliating treatment, overcrowding, inadequate food, sleep deprivation, and lack of health care in Jail Ogaden is consistent with the government’s long-standing collective punishment of people who are perceived to support the ONLF. Human Rights Watch has previously documented how the Ethiopian army committed crimes against humanity and war crimes during counter insurgency operations against the ONLF in 2007 and 2008, including extrajudicial executions, torture and rape.

Rather than meaningfully investigate the crimes at that time, the Ethiopian government established the Liyu police who have committed a range of serious abuses in Somali Region since 2008. The Liyu police report to the Somali Region president, Abdi Mohamoud Omar, known as Abdi Illey.

In Jail Ogaden, disease is rampant, basic water and sanitation needs are systematically ignored, while prisoners report deaths in detention following the outbreak of infectious disease. Some former prisoners told Human Rights Watch that corpses sometimes remained in prisoners’ cells for several days.

Female prisoners gave birth in their cells without access to skilled birth attendants, often in grossly unhygienic conditions. The plight of children, some allegedly born in Jail Ogaden from rape by prison guards, is especially tragic. Former prisoners said that lactating mothers received no extra food, and that children received no education. Since 2013, prisoners have reportedly not been permitted any visitors, or to receive food or other goods from relatives.

Release of prisoners is often ad hoc and the length of prisoners’ sentences, when they have one, may have little bearing on when they are actually released.

Former prisoners said that senior Somali politicians including Abdi Illey and Somali Region head of security and head of the Liyu police Abdirahman Labagole appeared regularly at the prison to speak to the prison population. Many of the worst abusers have been the prison heads of Jail Ogaden. Not only do some of these officials appear to have ordered torture, rape and denial of food, but in some cases, former prisoners alleged that they were personally involved in committing rape and acts of torture.

In 2011, Somali Region officials carried out an 11-day evaluation of prison guard performance which corroborated many of patterns of abuse former prisoners described to Human Rights Watch. The evaluation was filmed at the request of Abdi Illey, and then shared with Human Rights Watch several years later when an advisor to Abdi Illey left Ethiopia. On film, guards detail torturing, raping, and extorting money from prisoners, and describe how various senior officials at Jail Ogaden directed them to engage in torture and rape.

The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC), a federal government body mandated to carry out investigations into allegations of human rights abuse, has inspected Jail Ogaden on many occasions since 2011, but there are no publicly available reports on those visits. It is not clear what actions, if any, were taken to hold anyone accountable for abuses uncovered during those inspections. Many former prisoners told Human Rights Watch that they had been prepped by prison officials on what to say and what not to say to the Commission. The most visibly injured, along with children and pregnant women, were reportedly held in secret rooms or moved out of the prison ahead of Commission visits. Those who spoke openly to Commission officials were brutally beaten, sometimes to death, in the days after the visits. The EHRC did not respond to our letter requesting information about their work to address abuses in Jail Ogaden.

Ethiopia’s federal system gives considerable autonomy to its regions, including the Somali Region, to carry out many governance functions. Regional detention facilities in Somali Region have little federal oversight and the regional government has neither the will nor capacity to monitor detention conditions.

Very few of the former prisoners we interviewed said they had ever been to court or been charged with any crime. Even when prisoners did appear in court, most did not have access to defense lawyers, could not present an adequate defense, and were confronted with courts that lack independence and are reluctant to challenge government abuses. This all leaves prisoners in Jail Ogaden with virtually no channels for redress.

Torture and impunity for torture are well-entrenched problems throughout Ethiopia. Human Rights Watch regularly receives reports of abusive interrogations countrywide using techniques such as severe beatings and water and genital torture, similar to what Jail Ogaden’s former prisoners describe. As far as Human Rights Watch is aware, there have been no reported instances of the federal government holding anyone accountable for torture, and prisoners’ complaints of torture in detention are routinely ignored by the courts.

The Ethiopian government’s response to requests for investigation into alleged rights abuses is to state that the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) can carry out such investigations, but EHRC investigations have generally not met the most basic standards of impartiality. There is little transparency around its work. The government has repeatedly rejected calls for independent international investigations into abuses and has ignored repeated requests from the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and eight other UN Special Rapporteurs to visit Ethiopia.

Ethiopia’s new prime minister, Dr. Abiy Ahmed, took office in April 2018. Since then, he has pledged to implement progressive reforms and his government has closed Maekelawi detention center in Addis Ababa, a site notorious for torture and abuse of prisoners. He also acknowledged that torture exists in Ethiopia in a June speech to parliament, a rare admission for an Ethiopian prime minister.

Thus far, however, the new prime minister has not stated how his government will tackle the larger problem of impunity for torture. While many former prisoners would welcome the closure of Jail Ogaden, such a move would not address the abusive nature of the region’s security forces, the impunity of those who engage in serious abuses, or the weak rule of law in Somali Region.

Ethiopia should comply with the provisions of its own constitution and fulfill its core obligations under international human rights law—in particular the absolute prohibition on torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment—by systemically addressing persistent allegations of torture and illegal detention. Ethiopia’s new prime minister and senior officials, including in the federal police and the military, should urgently and publicly condemn abuse of prisoners in Jail Ogaden and other prisons in Ethiopia, to send an unequivocal public message that mistreatment of prisoners will not be tolerated—and back up such announcements with disciplinary action and prosecutions of officials who engage in such practices.

In the face of numerous and horrific allegations, Dr Abiy Ahmed and parliament should establish a federal Commission of Experts (COE) for Somali Region. The Commission should investigate abuse at Jail Ogaden and recommend specific officials, regardless of rank, to face criminal charges for the mistreatment of prisoners. This should include specific investigations into senior Somali Region officials such as President Abdi Illey and current head of Liyu police Abdirahman Labagole.

Furthermore, authorities should allow access to Jail Ogaden and all other detention centers throughout the country to independent Ethiopian and international monitors, including human rights and humanitarian organizations, members of the diplomatic community, African Union human rights mechanisms, and UN mechanisms such as the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention.

Prime Minister Abiy should also take immediate steps to substantially reform the Liyu police and hold senior members of the Liyu police and Somali Region government to account for serious human rights violations, including torture in Jail Ogaden.

Recommendations

To the Prime Minister of Ethiopia

- Publicly and unequivocally condemn torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment in Ethiopia. Underscore that there is never a justifiable reason to use torture.

- Support the establishment of a federal Commission of Experts (COE) to examine abuses in Jail Ogaden. The COE’s tasks should include:

- a process for evaluating the case of each prisoner in Jail Ogaden to ensure that:

- those who have completed their sentences are released,

- those who have not been charged are either promptly charged based on credible evidence or are released immediately, and

- those who have been charged have a chance to defend themselves, with legal assistance, before an impartial court.

- an investigation into allegations of torture as raised by individual prisoners during their case determinations; and,

- recommendations for criminal charges against individual officials involved in abuse, regardless of their rank. This would include individuals who carried out acts of torture, those who directed it, and those with command responsibility over prison officials involved in abuse.

- If the Commission is not established, promptly order a transparent and impartial investigation into allegations of torture and ill-treatment and ensure that all personnel implicated in serious abuses, regardless of rank, are appropriately disciplined or prosecuted. Publicly release regular reports detailing the progress and results of investigations, and any actions taken against individuals implicated in abuse.

- Work with parliament to draft and define a clear legal mandate for regional Liyu “special” police forces across Ethiopia.

- Take immediate steps to substantially reform the Liyu police, which could include clarifying command responsibilities and disbanding abusive units.

- Ensure appropriate funding, oversight, and regulations to ensure Ethiopian prisons rapidly improve the conditions of detention and can meet the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.

- Allow independent monitoring of Jail Ogaden and other detention facilities and prisons by independent human rights monitors. This should include the ability to conduct private, confidential meetings with prisoners.

- Offer a standing invitation to relevant United Nations and African Union human rights mechanisms including the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to visit Ethiopia.

To the Ethiopian Parliament

- Work with the Prime Minister’s office to establish the federal Commission of Experts (COE) described above.

- Amend provisions in the Criminal Procedure Code that are contrary to Ethiopia’s international legal obligations to ensure that prisoners have prompt access to a lawyer, prevent unreasonably long pre-trial detention, and clarify evidentiary standards to ensure that no statements, confessions, or other information obtained as a result of torture or other ill-treatment can be accepted as evidence.

- Increase federal oversight of all places of detention in Somali Region.

- Ensure that the federal police, military, regional police, special police, prison guards, and other law enforcement personnel receive appropriate training on interrogation practices that adhere to international human rights standards.

- Ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

To the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission

- Conduct frequent, unannounced visits to Jail Ogaden and other detention centers, privately and confidentially interview prisoners, consider interviewing prisoners who have been released who may have less fear of reprisals, and follow-up on allegations of mistreatment.

- Take urgent steps to minimize the likelihood of reprisals against prisoners who speak to Commission staff during visits, including follow up visits to those prisoners who spoke to the Commission. Ensure that Commission staff alone can choose interviewees.

- Publish all reports that pertain to treatment of prisoners and conditions in Ethiopia’s detention centers. Make Jail Ogaden detention reports publicly available in both Amharic and Somali and indicate what steps, if any, were taken to improve prison conditions and hold to account individuals, including through command responsibility.

To the United Nations Human Rights Council

- Press for the release of all political prisoners or those individuals arbitrarily detained in Ethiopia’s Somali Region and elsewhere in Ethiopia.

- Urge Ethiopian officials to invite relevant UN human rights mechanisms, including the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to visit Ethiopia.

- Ensure a credible, independent and transparent investigation into the ongoing problem of torture in Ethiopia’s many places of detention.

To Ethiopia’s International Partners

- Publicly and privately raise concerns with Ethiopian government officials at all levels regarding arbitrary detention, torture, ill-treatment, and other human rights violations in Jail Ogaden and other detention facilities in Ethiopia.

- Donors that fund programs that may involve Ethiopia’s security forces should conduct thorough investigations into allegations of human rights violations by those security forces within places of detention to ensure funding is not going to abusive units.

- Actively seek unhindered access to detention facilities for international humanitarian and human rights organizations to monitor the conditions of those detained, and document cases of arbitrary detention.

- Urge Ethiopian officials to invite relevant UN and AU human rights mechanisms, including the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to visit Ethiopia.

- Publicly urge prompt, transparent, and impartial investigations into allegations of abuse in detention facilities.

- Investigate the extent to which block grants are being allocated to regional security budgets in Somali Region, used in part to fund the abusive Liyu police.

- Press the Ethiopian government to reform the abusive Liyu police.

To the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Working Group on Arbitrary Detention

- Seek an invitation to visit Ethiopia but consider, in absence of an invitation, alternative means to gather information and report on the issue.

To the UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers

- Seek an invitation to Ethiopia to investigate issues around the independence of the judiciary in Ethiopia, but with specific focus on Somali Region. Consider, in absence of an invitation, alternative means to gather information and report on the issue.

To the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR) Special Rapporteur on Prisons, Conditions of Detention and Policing in Africa

- Request an invitation to Ethiopia to investigate the situation of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment in detention in Ethiopia, including Jail Ogaden.

Methodology

This report documents patterns of serious, widespread human rights violations in Jijiga’s Central Prison, commonly called Jail Ogaden, which occurred between 2011 and early 2018. It is based on research conducted in Ethiopia and nine other countries in Africa, Europe and North America, primarily in 2017 and 2018. Over the course of investigating various allegations of abuse in Ethiopia’s Somali Region over the last 10 years, numerous individuals described to Human Rights Watch being detained in various places of detention, but in particular, Jail Ogaden.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 98 people, including 70 former Jail Ogaden prisoners. Thirty-two of the former prisoners were women. Interviewees also included family members of prisoners, regional government officials, and former Liyu police and other security and intelligence officials. All were interviewed individually in person, via telephone, or other secure communication methods. Those interviewed had a wide range of backgrounds, ages, gender, political and clan affiliations, and were from diverse geographical locations in Somali Region, to provide as broad a perspective as possible. Ten of the former prisoners interviewed, including two women, said they were under the age of 18 at the time of their detention. Age verification in Ethiopia’s Somali region is difficult. Many individuals we interviewed were not aware of their precise age and most rural residents, who make up the bulk of prisoners, do not have any birth or identity documents.

Human Rights Watch conducted some research for this report inside Ethiopia, but most victims of abuses were interviewed outside the country, where they were able to speak more openly about their experiences. The government frequently attempts to identify victims of and witnesses to human rights violations who provide information to the media or human rights groups. The authorities have harassed and detained individuals for providing information or meeting with international human rights investigators, journalists, and others. This often makes it impossible to assure the safety and confidentiality of victims of human rights violations interviewed inside the country.

The risks of reprisals are particularly significant in Somali Region, where Human Rights Watch has documented numerous cases of specific threats, harassment or arrests of family members of Ethiopian Somali diaspora who are active on social media, have participated in diaspora protests, or otherwise expressed criticism of the regional government. In at least one case, our research indicates that state agents killed family members of an Ethiopian in the diaspora who spoke out. Human Rights Watch documented such threats and intimidation against family members living in Somali Region whose relatives reside in eight of the nine countries where we conducted research. Consequently, in the footnotes to this report, all interviewees unless otherwise noted have been assigned numbers and in the report, interviewees have been assigned pseudonyms. Locations of interviews and key identifying information have been withheld to reduce likelihood of reprisals. All interviewees in Sections III-VI, unless otherwise noted, are former prisoners.

Human Rights Watch identified interviewees through various methods including torture survivor groups, community-based organizations and other former prisoners. Fifteen translators helped to interpret from Somali or Afan Oromo into English where necessary. No one interviewed for this report was offered any form of compensation. All interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview and its voluntary nature, including their right to stop the interview at any point, and gave informed consent to be interviewed.

Human Rights Watch also consulted court documents, medical reports, photos, videos and other relevant material, including academic articles, reports from nongovernmental organizations, and information collected by other credible experts and independent human rights investigators that could corroborate details or patterns of abuse described in the report.

Human Rights Watch also corroborated patterns of abuse from 2011 by reviewing 25 hours of video from an 11-day evaluation of Jail Ogaden prison guard performance. Senior Somali Region officials conducted the evaluation and Somali Region president Abdi Illey requested the sessions to be filmed. Years later, an advisor to Abdi Illey provided a copy of the video to Human Rights Watch and others working on abuses in Somali Region. Human Rights Watch took various steps to authenticate the video.

Throughout the research, Human Rights Watch took various precautions to verify the credibility of interviewees’ statements. Unless otherwise specified, all the patterns of abuses described in this report was based on at least two, and usually many more than two, independent sources including both interviews and secondary material.

This report does not purport to establish an exhaustive list of alleged perpetrators. Named individuals had clear command responsibility and control over prison guards during the time of serious abuses or personally carried out abuse according to more than two interviewees. Former prisoners we spoke to identified many other perpetrators who are not named in the report, but some of those allegations could not be fully corroborated because of the limited amount of interviews conducted, further underscoring the need for an independent investigation into abuses at Jail Ogaden.

This report is not an exhaustive account of all of the human rights abuses associated with Jail Ogaden. The Ethiopian government’s restrictions on access for independent investigators and hostility toward human rights research make it difficult to corroborate details of some incidents that have been described to Human Rights Watch, and we have not included those allegations here. While restrictions are countrywide, they are particularly draconian in Somali Region. Humanitarian actors, diplomats, and journalists are all restricted from traveling to many parts of Somali Region. There is also a serious lack of credible information published on the most basic aspects of Somali Region governance, justice, and human rights and a lack of transparency around Somali Region laws and government institutions.

The report covers abuses over a lengthy period. This is in part because of the lack of detailed information publicly available about Liyu police abuses in Somali Region since 2011. Also, during this period, based on interviews with victims, the patterns of abuse have not changed, and no one that we are aware of has been held to account for these abuses. The beginning of this period also coincides approximately with when the Liyu police took over functional control of the prison.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the government of Ethiopia and the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission in April 2018 to share the findings of this report and to request input. We also requested information regarding steps that the government may have taken to conduct investigations or discipline security forces responsible for abuses in Jail Ogaden. We requested a meeting to discuss these concerns. Copies of the letters were sent to the Ethiopian Embassy in Washington DC. In June, we followed up with the Embassy by email and telephone. We did not receive any response at time of writing. The letters are included in the appendices to this report. We welcome dialogue on these and other human rights issues with the government of Ethiopia and with the leadership of Somali Regional State.

I. Background

Torture in Ethiopia

Torture remains a serious and very underreported problem across Ethiopia. Human Rights Watch receives regular reports of torture in places of detention country-wide. [1] This includes police stations, prisons, military camps, and various unmarked places of detention.[2] Other NGOs and various media outlets have also reported on torture over many years.[3] Torture is pervasive across Ethiopia’s security and intelligence institutions, but some of the most brutal torture occurs at the hands of the Ethiopian military and, since 2010 in Somali Region, at the hands of the Liyu police.

While patterns vary country-wide, Ethiopian officials often rely on torture to extract confessions, typically regarding a prisoner’s connection to one of the groups that the government have designated as terrorist organizations, to gain information, or merely as punishment.[4]

The government’s response to regular allegations of torture is denial and to suggest that they are politically motivated.[5] The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission does not meaningfully investigate the many torture allegations, nor do any of the other oversight mechanisms, including the courts. Ethiopia has not responded to repeated requests from the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment for an invitation to visit the country.[6] Human rights groups and international organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) continue to be denied access to federal detention centers, including military camps, and to places of detention in Somali Region.[7]

Ethiopia is party to various international and regional treaties that confer legal obligations regarding the treatment of prisoners and the conduct of security personnel.[8] Article 424 of Ethiopia’s Criminal Code states that any public servant who threatens or treats a person under their custody “in an improper or brutal manner, or in a manner which is incompatible with human dignity or his office, especially by the use of blows, cruelty or physical or mental torture” is “punishable with simple imprisonment or fine, or in serious cases, with rigorous imprisonment not exceeding ten years and fine.”[9] Those who direct the use of “improper methods” are punishable “with rigorous imprisonment not exceeding fifteen years and fine.”[10]

Human Rights Watch is not aware of any cases where individuals were charged under this clause for committing or being responsible for, acts of torture. In 2010 the United Nations Committee against Torture raised concerns that the existing definition of “improper methods” in the 2004 Criminal Code was more limited in scope than the definition of torture under the Convention against Torture and urged revisions in the code.[11] At time of writing, there had been no such revisions.

The Ethiopian Criminal Procedure Code, in the process of revision, contains new responsibilities around interrogations but Human Rights Watch has not seen the final version.[12]

The Federal Police Commission Establishment Proclamation of 2011 also prohibits the use of “any inhumane or degrading treatment or act” by federal police officials, although it does not apply to security personnel at regional prisons.[13] Human Rights Watch was unable to ascertain whether a similar prohibition is included in regional proclamations.

Strategic Importance of Somali Regional State

Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State (Somali Region or SRS) is one of the poorest and most underdeveloped regions in Ethiopia, suffering from a lack of basic infrastructure, weak governance structures and institutions, and endemic food insecurity.[14] Its approximately five million people are mostly ethnic Somalis who are either pastoralists or agro-pastoralists.[15] A historical mistrust of what ethnic Somalis often describe as “habesha” or Ethiopian "highlander"-dominated culture has contributed to an ambivalent affiliation with Ethiopian national identity. In many ways, the region’s ethnic Somali population is culturally and economically intertwined with neighboring Somalia and Djibouti.

Somali Region is of strategic importance to the Ethiopian federal government in part because of its rich resources, in particular oil and natural gas, and because of its strategic transportation corridors to the sea.[16] Important trade routes through Somali Region are critical not only for import of much-needed goods but also for export of Ethiopian goods, critical for Ethiopia’s foreign currency shortage.[17]

The Ethiopian government’s security interests in Somali Region are to contain armed insurgents, secure the border between Somalia and Ethiopia from infiltration of armed groups that could prove a threat to Ethiopia, notably the armed Islamist group, Al-Shabab, and influence events in Somalia in line with its interests.[18]

In Somali Region there is virtually no independent media or civil society. There is very little judicial independence on politically-motivated cases, and citizens have no recourse for the many human rights abuses.[19] Both international and Ethiopian domestic media have extremely limited avenues for reporting on events in Somali Region amid difficult access restrictions.[20] Even within the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) government, the Somali Region’s ruling party, the Ethiopian Somali Peoples’ Democratic Party (ESPDP) has a marginal role and is not one of the four ruling coalition members.[21] There are no legally registered opposition parties in Somali Region that are strong enough to meaningfully contest elections.[22]

Conflict and Repression in Somali Regional State

In 1991, when the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) came to power following the ousting of the Derg, it implemented “ethnic federalism,” which gave meaningful autonomy to many of Ethiopia’s ethnic groups, including ethnic Somalis. [23] In the first regional elections, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), despite having limited political experience, won 60 percent of regional parliamentary seats.[24] Relations with Ethiopia’s ruling coalition soured over the next several years, however.[25]

In 1994, ONLF-EPRDF tensions came to a head when Somali Region parliament attempted to hold a referendum on self-determination.[26] The federal government promptly arrested the regional president and his deputy and most senior members of the regional administration were fired.[27] Having been effectively removed from government, the ONLF began an armed insurgency against the Ethiopian state inside of Somali Region.

ONLF Insurgency and the Rise of the Liyu Police

In April 2007, the intensity of the conflict in Somali Region increased when the ONLF attacked the Obole oil site, capturing and killing more than 70 Chinese and Ethiopian oil workers as well as scores of Ethiopian soldiers.[28] In May 2007, the ONLF was believed to be responsible for a grenade attack on then regional president, Abdullahi Hassan, in the capital, Jijiga, that killed five people and injured dozens, including Abdullahi.[29] Shortly thereafter the Ethiopian government commenced a large-scale counteroffensive to suppress the ONLF, and brought large numbers of military troops into the region.[30] Between 2007-2009, the Ethiopian military embarked on a brutal counterinsurgency campaign, forcibly displacing entire villages, and publicly executing individuals accused of supporting the ONLF. Rape of women was widely reported.[31] Many individuals were imprisoned without charge in military camps or makeshift detention centers.[32]

The collective punishment of the civilian population was a cornerstone of the strategy of the Ethiopian Defence Forces (EDF) during these years.[33] Human Rights Watch concluded that both the ONLF and the EDF committed war crimes and that the EDF was responsible for crimes against humanity. [34] The government has never taken steps to allow for an independent investigation of these abuses.

In 2009, the Liyu police emerged in Somali Region, a brutal special police force that reports directly to the president of Somali Region.[35] Comprised of ethnic Somalis, many of them from the Ogaden clan, the Liyu police slowly replaced the EDF in their battle against the ONLF inside Somali Region.[36] This shifted the conflict away from what many Ethiopian Somalis framed as an Ethiopia versus Somali conflict, one with long standing historical dimensions, into a conflict between different actors from within the same Ethiopian Somali clan. The Liyu police employed various recruitment strategies, including recruitment from prisons. In some cases, refusing recruitment into the Liyu police could be seen synonymous with sympathy for the rebels, which warranted imprisonment or worse.[37] Families and communities became divided, with some members supporting ONLF and others supporting the Liyu police. The EDF initially gave military training to the Liyu police, and the EDF retained oversight of their operations in the early years with Liyu police autonomy increasing over time.[38]

The Liyu police continued the EDF strategy of collective punishment of civilians who may support the ONLF and committed the same kinds of horrific abuses.[39] Human Rights Watch has received consistent reports since 2009 of very serious crimes allegedly committed by Liyu police, including deliberate massacres of people in villages, extrajudicial killings, torture, rape, and property destruction.[40] These alleged abuses have been focused in the areas where the ONLF are popular or were engaged in attacks on military targets. Targets of abuse have included relatives of ONLF members, or those the Liyu police perceive to have provided food, water, shelter or information to the ONLF.

While the ONLF still exists as an armed group, the frequency of attacks by ONLF has decreased greatly in recent years. [41]

Liyu police have also been more active outside of Ethiopia’s Somali Region, including inside both Somalia and Ethiopia’s Oromia region. In late 2017 over one million people were displaced from their homes along the border between Somali Region and Oromia, after a wave of attacks that communities attributed to the Liyu police.[42] In the meantime, sources inside Somali Region described to Human Rights Watch increased recruitment of Liyu police, including children, in the last six months.[43]

Withholding Humanitarian Assistance and Liyu Police Funding

Food insecurity in Somali Region is a serious and recurrent problem. During the decade long conflict with ONLF, security forces restricted access to grazing land and water points, confiscated household assets including livestock and camels, and looted property of those they perceive to support the ONLF.[44]

Human Rights Watch also receives reports of food aid, often distributed through government channels, being restricted for communities or families that are perceived to support the ONLF or who are perceived not to support Abdi Illey.[45]

Several former regional government officials described to Human Rights Watch how an effective humanitarian response is crippled by a sizeable percentage of Somali Region sectoral budgets[46] being funneled to Somali Region’s security budget, most of which goes to the Liyu police. Mohamed, 28, who worked in a financial capacity in one of the bureaus that routinely had money moved into the regional security budget said:

A significant percentage of our budget each year was moved into the regional security budget. Reports [for donors] would show money went to the appropriate areas, but we would not let them visit those areas for “security reasons.” We were also told we couldn’t do work in the areas where the ONLF has support because of security reasons. But there were no security issues in many of those areas. It was done to punish them, and the money we saved went straight to the Liyu police [budget].[47]

President Abdi Mohamoud Omar and Reprisals for Expression of Dissent

During the height of the EDF abuses in 2007-2008, the regional head of security was Abdi Mohamoud Omar [commonly known as “Abdi Illey”]. In July 2010, he became the president of Somali Region. Five individuals involved with Somali region security forces, including two former Liyu police members, told Human Rights Watch of the command responsibility he has over the Liyu police, describing how he regularly communicates with Liyu police regiments on various operational matters. One said that “no operation is carried out without his knowledge and his support.”[48] According to one widely-credited report, Abdi Illey maintains a close relationship with the EDF’s Eastern Command Post in Harar who are generally understood to retain oversight over Abdi Illey and security affairs in Somali Region.[49]

Criticism of the regional authorities, particularly of Abdi Illey, is not tolerated, either inside or outside of Somali Region. Family members of Ethiopian Somali diaspora have been targeted in Somali Region and have been arbitrarily detained, harassed, and had their property confiscated after their relatives in diaspora attended protests or were critical of Abdi Illey in social media posts. Human Rights Watch has documented these reprisals from diaspora in Australia, United States, Kenya, Somalia, and throughout Europe.[50]

II. Jail Ogaden

Jijiga Central Prison, commonly known as Jail Ogaden or Jail Ogadeni [Jeel Ogaden in Somali] is in Jijiga, the capital of Somali Region and is Somali Region’s main functioning regional prison. Estimates of prison population varied widely across time, but it is estimated there was an average of several thousand prisoners at any particular time between 2011-2017.[51] Within Somali Region, there are many other places of detention in local (kebele), district (woreda) and zonal police stations, EDF military camps, and Liyu police detention facilities.[52]

Physical Layout

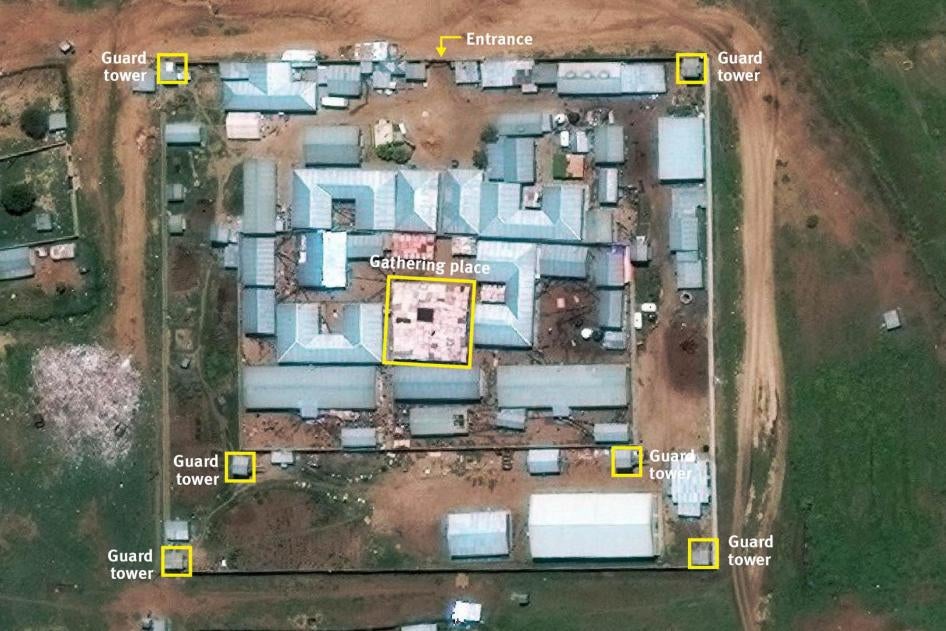

Jail Ogaden, located near Jijiga University, was built in 2001. The prison expanded in 2011, following the escape of some prisoners partially due to pervasive corruption involving prison guards.[53] At present the prison has an inner and outer wall and the majority of prisoners are held inside the inner wall in one of 23 cells. Meetings of the prison population are held in an open area in the middle, covered with a tarp. Civil servants and “high-ranking” prisoners, including at least three former Jail Ogaden prison heads, are housed in more spacious rooms in between the inner and outer walls. Men and women are segregated in different parts of the prison. Both male and female guards watch over the women’s section.[54]

There are eight guard towers around the inner and outer walls. At the base of these guard towers are rooms, some of which are below ground level, where high profile prisoners are kept, sometimes in solitary confinement. These rooms are also sometimes used to hide prisoners from visiting Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) officials.[55] Many prisoners reported being tortured in the area between the walls at night. Rooms 3 and 8 were the “punishment rooms” where the most intensive interrogations take place.[56]

Detention and abuse in Jail Ogaden is a key part of the strategy of collectively punishing and “rehabilitating” individuals the government believes are sympathetic to the ONLF to reduce their support for ONLF and to be more supportive of the government.[57] The need to support the government and to stop supporting the ONLF is frequently relayed by security officials in the prison-wide group meetings, kabba-led interrogations, and various individual interrogations. Beatings and punishment are seen as part of the rehabilitation process. Interviewees routinely described this kind of rehabilitation as the function of Jail Ogaden: “It is not a normal jail. You are there to be punished and “rehabilitated” for supporting the ONLF. It doesn’t matter if you do not [support], they want to make sure no one supports them ever again.”[58]

One prison guard discussed the ineffectiveness of that approach:

The inmates are brought to be rehabilitated and reformed but we don’t do that. What we do encourages them to redo or continue doing their vices because we torture them.[59]

Roles and Responsibilities in Jail Ogaden

Jail Ogaden is managed by aslubta [prison guards or “custodial corps”] and the Liyu police. As time has gone on, the Liyu police have taken on more and more responsibility in the prison. The role of the EDF has declined in parallel with their declined role in Somali Region more broadly, but they still use the prison occasionally.

Since 2012, the head of Jail Ogaden has typically been a member of the Liyu police and both Liyu police and the aslubta that work in the prison report to them. The head of Jail Ogaden reports to the Somali Region prison commissioner. While the Somali Region prison commissioner is responsible for all places of detention in Somali Region, in practice they are heavily involved in the day to day affairs of Jail Ogaden.[60] The regional commissioner reports to the Regional head of security, who at present is also the head of Liyu police.[61] Since 2011, those positions have been held by General Abdirahman Abdillahi Burale, commonly known as Abdirahman Labagole. He reports to the president of Somali Region, who since 2010, has been Abdi Illey.

Each prison cell has a head prisoner, called a kabba, and vice-kabbas. They are sometimes former Liyu police or aslubta who previously worked at Jail Ogaden.[62] The structure has evolved over time, but in general the kabba is responsible for handing out minor punishments, is responsible for group interrogations at night and sharing interrogation findings with prison guards, and in keeping discipline in the cell, including mediating arguments and determining where people sleep.[63]

Prison Population

The vast majority of Ethiopian Somalis in Jail Ogaden are from the Ogaden subclan, who also make up the bulk of the ONLF. Some of the prisoners are criminals, some are ONLF fighters, while many are civilians who are accused of supporting ONLF with food, water, shelter, or information.[64]

There are also some Oromo prisoners in Jail Ogaden, particularly those who reside in Somali Region. In addition, many Oromos, including asylum seekers, who are arrested in Somaliland and forcibly returned to Ethiopia are often held in Jail Ogaden.[65] These forced returns increased dramatically in mid-2017 as conflict along the Oromia-Somali Region border escalated.[66]

III. Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment

I was kept in solitary confinement in complete darkness for most of my [three-year] detention. I was only taken out at night for torture. They [prison officials] did many things to me - they electrocuted [applied electric shocks] my testicles, they tied wire around them, and they put a plastic bag with chili powder over my head. I often had a gag tied in my mouth so I wouldn’t scream too much. During the day, I was given very little food - one [piece of] bread and occasionally a bit of stew. They also raped my wife [who was also in Jail Ogaden]. She gave birth to a child that was not mine there.

—Abdusalem M., aged 28, March 2018.[67]

Almost all of the 70 former prisoners interviewed by Human Rights Watch described being tortured in Jail Ogaden and many showed Human Rights Watch physical scars from what they endured in detention. Almost all also reported seeing people being beaten and humiliated in front of large groups of people.

Former prisoners said that prison guards removed people from their cells during the night and later returned them injured, bleeding, shaking, and/or crying. In some instances, former prisoners said that prisoners died in the cells and they attributed these deaths to injuries sustained during interrogations.[68] One Oromo man described how, “…in my room, somebody would die every night. Some would die because of hunger. Some people would die because of the beatings. Sometimes the bodies would lie in our cells for multiple days.”[69]

The Convention against Torture (CAT), to which Ethiopia is a party, defines torture as “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person… when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official.” Under CAT, torture can include acts carried out for a broad range of purposes, including interrogation, intimidation and punishment.[70]

Torture Routines

Former prisoners described a brutal daily schedule of physical and psychological abuse and degradation and a weakened physical state from overcrowding, sleep deprivation, inadequate food, poor sanitation, and absence of health care.

There were three settings in which officers and kabbas (head prisoners) meted out physical brutality:

Individual torture: Most frequent during a prisoner’s early days of detention, prisoners were taken to individual rooms or outside areas and interrogated while being beaten and often tortured by prison officials.

Prison-wide meetings: All prisoners described large group meetings happening on a regular basis, usually in the mornings, where prison officials or regional government officials would speak. Former prisoners said that after 2011, these group meetings occurred with more frequency. The meetings, which usually lasted for several hours, usually had one of two purposes:

- to indoctrinate the prison population on how the government was good for the people and in favor of peace, while the ONLF were the enemies of the people; or,

- to interrogate or humiliate certain prisoners in front of the whole prison population.

“Abdullahi D.,” a 28-year-old man and former prisoner, told Human Rights Watch:

During my time [2013-2014], we had large meetings twice a week. There were various people who would speak to us, including Abdirahman Labagole. They would bring prisoners up on stage in front of the prisoners and tell them to admit what they have done and to give information “Did you support ONLF?” or “How did you start the idea to criticize the president [Abdi Illey]?” Or ladies accused of supporting ONLF will also be on stage and a male prisoner would be asked “Which of these ladies did you gang rape when you were ONLF? Point out that woman.” He would be forced to say “I gang-raped that one.” They make you say the most ridiculous things to humiliate you: for example, they would force you to say you raped sheep or goats. If you don’t say these things, you will be beaten.[71]

“Ayan A.,” a 40-year-old woman and former prisoner, described the types of punishments that were common at these meetings:

Often they would line up some men and women, take off their clothes and make them stand in front of the other inmates. Five times I saw them tie a jerry can full of water to a naked man’s genitals and make him walk around. They once made me lie naked on the ground in front of everyone and roll around in the mud while they beat me with sticks. Once they made an old man stand naked with his daughter…you would feel such shame after these treatments in front of all the other prisoners.[72]

Sometimes pro-government and anti-ONLF entertainment took place during these meetings. One man said: “On Saturdays sometimes we had music, but if people didn’t clap loud to show they like the message they would be taken away for punishment.”[73]

Evening Small Group Interrogations: Most prisoners described smaller group interrogations inside rooms in the evenings where prisoners were divided into groups and interrogated by other members of the group or by the kabbas.

Sometimes these interrogations would involve one prisoner in front of the room who was interrogated by the other prisoners in the room. Other times the room was divided into smaller groups, usually in fives, but sometimes as many as 15 prisoners. An individual prisoner would be made to stand to be interrogated by other members of the group. The goal was to get the individual to confess to playing some role in support of the ONLF and to show remorse. The kabba or prison guard would supervise, taking notes, occasionally hitting with sticks both the person who was being interrogated and others in the cell who were not participating or who fell asleep.[74] Notes of the interrogation would be shared with prison guards. In some cases, if the information was seen as particularly revealing, that individual would be taken away by the aslubta or Liyu police in the morning or the following evening for more individual interrogation.[75] Responsibility for managing these interrogations fell on the kabbas but in some rooms prison guards or Liyu police would participate.[76] According to our research, in the men’s rooms this would happen most nights, particularly since 2013. In the women’s rooms, it was less frequent.

“Ali H.,” a 32-year-old man and former prisoner, described:

When night falls the evaluations start. It is only inmates doing this to each other, in the morning the report is given to the guards. The more you deny, the worse the torture. The better the confession, the less the beatings. The more you admit to during the evaluation, the more people will clap and if you don’t admit to things the kabbas or prisoners will beat you right there.[77]

|

The 2011 Gemgema Evaluation of Prison Guards

In 2011, senior regional government officials carried out a 14-day gemgema [group evaluation] of prison guards [aslubta]. The president of the Somali region Abdi Illey was travelling internationally at the time and asked one of his presidential advisors Abdullahi Hussein to have the session filmed so he could watch it upon his return. In 2012, Abdullahi Hussein fled Ethiopia to Sweden and brought with him 25 hours of film from this assessment and dozens of hours of other films from other meetings and events around Somali Region. Human Rights Watch has reviewed the footage. On the video, prison guards spoke openly about being involved in serious human rights violations, including torture and rape. Many described then-regional prison commissioner Abdi Bede directing them to carry out these acts and being involved in the pervasive problem of prison guards raping women in the prison. Among the many individuals who were named for their involvement in the abuse was the then head of Jail Ogaden, Mohamed Sheikh Ahmed [commonly known as “Aweys”]. Prison guards described inadequate training, corruption, and death of numerous inmates from torture and mistreatment. Senior government officials leading the evaluation included head of Liyu police Abdirahman Labagole, regional vice president Abdullahi Yusuf Werar [commonly known as Abdullahi “Ethiopia”] and regional prison commissioner, Abdi Bede Osman. During this period, President Abdi Illey filmed many of his activities around Somali Region, including the mock execution of the two detained Swedish journalists Martin Schibbye and Johan Persson, meetings, Liyu police graduations, and this evaluation. He often used these materials to promote himself and the activities of the security and development sectors. Gemgemas are common across Ethiopia and involve an open-ended evaluation of the performance of a government employee or political party member by their colleagues. These evaluations can be tied to promotions, demotions or dismissals and can last many days. Human Rights Watch could not immediately ascertain if there was a specific purpose to this particular gemgema. Human Rights Watch has been unable to ascertain what disciplinary actions, if any, occurred as a result of the findings brought forward during the gemgema. Immediately after the assessment Abdi Bede was promoted to Head of Security for the president. |

Beatings

Virtually all prisoners described regular beatings by prison officials, either with hands, boots, gun butts, wooden sticks, metal sticks, or plastic wires. Sometimes cold or dirty water was thrown on prisoners prior to beatings.

Beatings were carried out at all times of day and at various locations in the prison. Sometimes individuals were targeted for beatings, while other times guards and kabbas would beat prisoners indiscriminately. One prisoner described the frequency: “they beat you at night, they beat you in the day. They beat you when you line up for the toilet, they beat you during meetings, the kabba beats you in your room. They beat you all the time!”[78]

“Halima H.,” a 26-year-old woman and former prisoner, told Human Rights Watch:

They [prison guards] took chili powder and ash from the fire and mixed it with water. We were tied suspended from the ceiling. They throw dirty water over you, then they would beat us with the stick from the fire. Other times they lie us down and pour water on us and then beat us. When we knew they were coming we would put on more clothes so that we would have more padding when we were hit.[79]

Several prisoners described prisoners being taken out of rooms and beaten at night under the lights to intimidate others. “Abdullahi N.,” a 28-year-old man and former prisoner, described his experience in 2012:

Certain strong prisoners are picked and everyone must watch them be beaten. This was done to intimidate others. At midnight, 1 a.m., 2 a.m., they would put on lights so people could watch. Sometimes they would slap them, sometimes hit with sticks, sometimes hands were tied behind back, or sometimes they would put chili powder in people’s eyes. One man was beaten while being accused of inciting prisoners. They kicked him in the stomach. When he fell, they beat him until he died. I was 20 meters away from this, there was nothing I could do.[80]

The then regional head of security and vice-president of Somali Region Abdullahi Yusuf Werar [commonly known as Abdullahi “Ethiopia”] acknowledged torture during the recorded evaluation: “My interpretation is that this was common and majority of the officers used to undertake it.”[81]

Also in that video, one prison guard said:

It was a common knowledge that the police and the prisoners were tortured. I was a security detail for the commissioner [Abdi Bede]. He used to alert us when someone is to be beaten up…. During the beating, some policemen were credited for holding the torch well and others were praised for carrying out the beatings well. Whoever fails to beat the prisoners was tortured.[82]

Many prisoners spoke about the revolving door of prisoners becoming prison guards or Liyu police who then became prisoners again: “they do to others what was done to them.”[83] One guard described this pattern:

I cannot deny or hide there was torture. When I was a prisoner I was beaten every night. My ribs are broken because of it. And when I got out, I was never trained or attended any seminar. I took my cudgel [stick] and started enforcing the law that was already in place. No one can deny that.[84]

During the 2011 evaluation, numerous prison guards spoke of Abdi Bede and Mohamed Sheikh Ahmed (commonly known as “Aweys”), then head of Jail Ogaden, directing them to carry out torture.[85]

|

Torture of Prison Guards

During the 2011 group evaluation 12 prison guards said senior officials expected them to beat prisoners and that if they refused they would be beaten or arrested. A prison guard said: We exercised torture and beatings. It was an order from the office. If we catch a prisoner and we do nothing, we were beaten ourselves. How many times was I beaten for that? … I was detained for eight nights because I didn’t participate in beating a prisoner. It was not something we chose to do; we were forced. If you lag behind, you are beaten up and told you are ‘flesh’ [soft]. We were treated like prisoners; hands tied/handcuffed behind our back and watered [tortured using water] if we hesitate beating a prisoner. We were saving our bones [protecting ourselves]. Former prison guards described ranks being only given to those that “carry out the torture.” One man described: “For instance, [name withheld] was a police commander and he was stripped of his rank, beaten up and assigned outside because he didn’t beat people. We did it out of fear for our lives.” One commander in the aslubta described: “I was detained for seven nights for not beating a prisoner. I even stopped the commissioner [Abdi Bede] from beating the police when no one else dared.” Another prison guard said: “One night I declined to beat a prisoner. Aweys [Mohamed Sheikh Ahmed, head of Jail Ogaden] slapped me and I have a hearing problem on the left ear as a result.” |

Rape and Other Sexual Violence

Some women said they were taken away from the prison at night to either Gidib, (the water reservoir on the outskirts of Jijiga), houses of regional government officials or Liyu police, or other unknown locations, where they were raped.[86] Women were often raped by members of Liyu police and the women usually knew only the roles the perpetrators played at Jail Ogaden, not their names. Most of the 32 female prisoners interviewed described seeing women being taken away from their cells at night, and often, but not always, returned in the morning or later the same night. Prisoners reported that guards and Liyu police who took women away were sometimes drunk or under the influence of khat, a mild stimulant grown in the Ethiopian highlands and popular among Somalis.[87] Women often came back crying, with ripped clothes, and described their ordeal to the other prisoners, or implied that they had been raped.[88]

“Halima H.,” a 26-year-old woman and former prisoner, told Human Rights Watch about women being returned from Gidib: “Most nights, some women are taken out of the prison. But not all return. But if you return, you have been to Gidib and have been raped. They all tell us.”[89] Three women who were taken to Gidib described being raped by either Liyu police or EDF personnel who brought them to the reservoir.[90]

Women who said they were raped in Jail Ogaden by either Liyu police or prison guards were either taken to a room located near the guard’s quarters or outside of their cells but within the prison complex.[91] Many women reported being raped multiple times over the course of their sentences.[92]

Senior officials facilitated rape of prisoners. One former Liyu police officer described going to Jail Ogaden to “get some ladies” for Abdirahman Labagole, the head of the Liyu police. “He told me to bring him some ladies that were in the jail. Just any ladies. We are just free to enter and take people, there is no process for us.”[93] Four former prisoners said that senior prison official Shamaahiye Sheikh Farah [commonly known as Shamaahiye] raped women.[94]

One woman said: “He [Shamaahiye] raped many people from our room. He would come and before he would take them out would say ‘I am doing this for your humanity.’” [95]

Another woman said: “I was there when he [Shamaahiye] ordered the military [Liyu police] to rape the girls. He was saying this in front of a group of women: ‘You are our donkeys, even God cannot save you from us.’ And then they took some away. I was raped by one of those [Liyu police] men several weeks later.” [96]

Prison guards usually took women away from the cell one at a time and most described individual rapes, but several women spoke of incidents where several women were raped at the same time. “Hodan D.,” a 40-year-old woman and former prisoner, said:

Once they lined up seven women and raped them, I saw all this. They called specific people out of the room. They were raped in an area where you can see [the rapes] and hear their screams.[97]

Both male and female prison guards spoke about the prevalence of rape in Jail Ogaden during the 2011 evaluation, with one saying, “Rape was just normal.”[98]

Ten of the prisoners also described being raped in their original places of detention before they got to Jail Ogaden, either by members of the EDF or Liyu police.

“Amina H.,” 34 described the psychological impact of rape in the prison: “You would hear screams all the time. When people came back to the room, you see them shaking, shivering and crying… Every night I was scared because I wondered if I would be next.”[99]

Male prisoners described serious physical and psychological abuse stemming from humiliation and shame when they were pressured to rape female prisoners.

“Abdirahman Y.”, a 31-year-old man and former prisoner, said:

They [prison officials] used to order men who were prisoners to rape female prisoners. If they refused, they would threaten to kill them. They would point pistols at them and put the pistol in someone’s mouth. When it happened to me they brought me out of the room. There was a woman there I had never seen, they told me to rape her like “I did when I was with [the ONLF].” I refused so they threw me on the ground and started to beat me, soldiers walked over me, and I fainted.[100]

There are no mechanisms available to report rape, either inside the prison or more broadly in Somali Region.

Genital Torture of Men

Human Rights Watch interviewed six men who described having their genitals (penis and/or testicles) tied to heavy weights, water bottles, or bottles of sand when they were prisoners at Jail Ogaden. Some said this occurred in front of other inmates while others said it occurred during individual interrogations. Ten male prisoners interviewed described seeing individuals being returned to their cells exhibiting injuries apparently suffered as a result of this kind of torture.[101] One man told Human Rights Watch, “Twice they tied a bottle filled with water around my testicles. I would [also] have to hold heavy containers of sand up with my two hands. For others they took a container with sand and tied it around their testicles. Sometimes this happen[ed] at public meetings as an example to [intimidate] others.”[102]

Victims said they were unable to control urine, had generalized groin pain, had an inability to get an erection, and were infertile, which they attributed to the torture.[103] Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have documented similar methods of torture in places of detention in Ethiopia, particularly in Oromia.[104]

Water Torture

Thirteen former prisoners described being immersed in water, either as an interrogation technique or as punishment. Former prisoners told Human Rights Watch about being held for prolonged periods in various pools of water in between the walls of Jail Ogaden. Sometimes they would be immersed up to their chest in the water, other times prison guards submerged their heads in the water until they were about to faint, then pulled them out, asked them questions and then repeated the immersion.[105] “Fatuma M.,” a 26-year-old woman and former prisoner, described:

They would tie our hands together with rope, put us in the pool deeper than my head and keep you in. They would put around 10 people in that pool at a time. …They ask you all the usual questions: “Who do you know from ONLF? How did you support them?” Some people they pull out and there is no response from them. I don’t know if they died.[106]

One young man described being kept tied in a cold pool of water between the walls all night. In the morning, his hands and feet were tied to stakes in the ground and he was held there in his underwear the entire day in the hot sun before being returned to solitary confinement.

Ten former prisoners said that at night EDF, Liyu police, or aslubta took them to Gidib for interrogations.[107] There, prisoners were tied and their heads were submerged in water until they almost fainted, and then they were pulled out for questioning. Four prisoners described seeing at least six people being tied and just thrown into the reservoir to drown.[108]

“Abdusalem M.,”a 26-year-old man and former prisoner, told Human Rights Watch:

They [Liyu police] tied my feet and then my hands separately. They would either throw me in and then pull me out just before I drown or hold me from my ankles into the water. They pulled me out just as I was losing consciousness. Then they would put me on the ground a few feet away, wait until I vomit, and then do it again….Some people would die from this. When they pull us out they would show us the dead bodies lying there “that will be you next if you don’t give us info”.[109]

Prisoners told Human Rights Watch that cold temperatures in Jijiga made the immersion even more excruciating.[110] Five prisoners described groups of people being taken out of their cells at night.[111] In the morning only some of those in the group would return and many of those individuals said they had been at Gidib.[112] Those that were taken out and did not return are never located.

Stress Positions

Six former prisoners described being tied in uncomfortable positions for long periods of time, either at night or in the hot sun. Some prisoners said they had been tied in fig position, a common practice in detention in Ethiopia where arms and feet are tied together behind the back.[113] Some former prisoners also described having heavy objects put on their backs while in fig. [114]

“Fatuma M.,” a 26-year-old woman and former prisoner, said: “Fig is very hard on the shoulders. Everyone in my room was tied in fig at some point.” [115]

Stripped Naked

Twelve former prisoners described witnessing individuals being stripped naked and degraded in various ways.[116] In one instance three former prisoners said that several hundred men were stripped naked, forced to hold each other’s genitals and then pressed tightly together in a line.[117]

“Mohamed Y.,” a 32-year-old man and former prisoner, said:

I witnessed hundreds of men being undressed completely. It was at night and it was raining and muddy. They had called us out of the room, told us to take our clothes off, lie down and roll in the mud. Then some of us were taken back to our rooms naked. Others were told to walk in line holding each other’s genitals. Once you go back into the room you can let go. The guards took pictures of this laughing. [118]

“Ali S.,” a 28-year-old man and former prisoner, described another incident:

One of the nights in 2012, nine rooms were opened. And we were all asked to come out of the rooms naked. There were big lights outside. We were asked to look at each other while naked. This was really embarrassing because some of us were close relatives, and some were in-laws. They then told us to lie down and roll on the ground which was muddy because they had poured a lot of water on the ground. That jail is generally very cold so with cold mud on my body while I was naked it was freezing.[119]

Others, both men and women, were stripped naked and interrogated in front of large segments of the prison population.[120] Others were stripped naked and told to verbally abuse each other.[121]

Rolling in Hot Ash

Several inmates described being forced to roll in hot ashes.[122] One witness said he saw the practice in 2014: “They [Liyu police] will make fire and when the fire is out they make people roll in it. They get burns that we see later. I saw people roll in the fire.[123]

“Fatuma M,” a 26-year-old woman and former prisoner, described:

They used to come at night and take everyone out of our room: the pregnant, the children, everyone! They used to put us in several lines. They had very dirty water from washing clothes. They would take a small container of this water and throw it on us. Then they beat us with a stick or tube. Reason they put water on us is when you are wet the beating hurts more. They also used to make a fire and when the ash was ready they used to make us roll in it. It was very hot. I have some burns from that. The coals would go through our clothes right away. We used to have conversations in prison about keeping those clothes with the burn holes for when Abdi Illey gets charged. [124]

Solitary Confinement and Room 8

Certain high-profile prisoners were held in solitary confinement, particularly during the initial days and weeks of their detention. Four individuals described being held in solitary confinement in small rooms that were inside of larger rooms, including in room 8.[125] Other former prisoners said they had been held in small “holes in the ground” between the walls, particularly in 2011-2012.[126]

“Khalid M.,” a 50-year-old man and former prisoner, described being held there in 2014:

I was once kept in a hole. It is deep and only fits one person. They removed my clothes, tied my hands and put me there for one night. It is tight, you cannot sit. It is covered by a cement lid – it is heavy, so you couldn’t push it off.[127]

Eight former prisoners said that they were taken to rooms underneath the guard towers and held there, [128] six of whom were kept in solitary confinement there for up to three months.[129]

Ten prisoners described being held in room 8 where the most important prisoners were taken for limited periods of time for very intensive interrogation over days and weeks, often in solitary confinement.[130] One person, in solitary confinement for 15 days, described the impact of being held alone: “I did not know if it was day or night, or if I was alive or dead. When I got released into the main jail, I wanted to talk to everyone.”[131]

“Hassan A.,” a 28-year-old man and former prisoner, described his seven-day experience in room 8:

In room 8, there are many smaller rooms. The small rooms are for standing, only a skinny person can get in. There is no space in there. There are two hooks in there and they hang you by your arms from those hooks. Your feet just touch the ground and your face is against the wall. They would throw water in the room and at times it was at my mid-calves. Most nights they would come and question “are you confessing to being ONLF? If you say yes, we will take you out.” On the eighth night I was finally taken out to a pool of water between the walls. I was naked like the day I was born. They made me roll in that mud before putting me back into the pool.[132]

“Ahmed L.,” a 38-year-old man and former prisoner, described his three months of detention in room 8 in 2014:

In room 8, there are many small rooms and sometimes there are many inches of freezing cold water in up to your ankles or knees. Then they [prison officials] pull you out and just beat and beat until you are close to death. Then you are put back in the small room. You don’t know if you are alive or dead. The only time I would be let out is when we were taken to an area outside room 8 where cold water is poured over you and they beat you mercilessly while you were forced to roll in the mud. It is called galgalin [place where camels sit and roll themselves in sand]. They beat me in so many ways there. They beat my fingernails. They made me grab my ears with hands behind my thighs. You have to stay like that. If you fall down, they beat you till you are unconscious. I was happy when I got into the bigger rooms because at least I could finally talk [to other prisoners].[133]

Psychological Trauma

Many former prisoners told Human Rights Watch about the psychological trauma they sustained as a result of witnessing torture or being ordered to inflict abuse on fellow prisoners.

“Abdirahman Y.,” 31, described:

We were always being told to humiliate each other, but the worst was one day they brought together a number of prisoners and each was told to beat another person to death. They had metal sticks to give us for this. I was told if I refused then I had to kill myself. When we refused, they just beat us - but it’s that constant psychological punishment that is the worst.[134]

Former prisoners described not only their own physical experience with torture, but the psychological anguish of seeing physically injured and traumatized people returned to their rooms after being tortured, and hearing screams, hitting and crying throughout the night and sometimes during the day.[135]

“Amina H.,” a 34-year-old woman and former prisoner, said:

Every night I could hear them hitting people. I heard so much crying. In the morning when people are sitting in front of my house eating breakfast everyone would speak quietly about who had been taken away the night before: “Mr so and so was killed by beating last night, or so and so was raped last night.” Every morning we would go through the list of those who had died or just didn’t return to their cell. We lived in a constant state of fear that we would be next.[136]

Numerous prisoners also spoke of the fear of being taken to the “punishment rooms”, also known as room numbers 3 and 8. “Ahmed S.,” a 40-year-old man and former prisoner, described:

I saw these rooms from the outside and spoke to the prisoners about them. They would beat prisoners [who were held there] all night and there is no air. In the morning sometimes they would carry bodies out on a stretcher through the main compound to the ambulance that was waiting in the outer courtyard near the gate. We were all usually out in the [inner] courtyard then so we would see this and it would terrify us. We believe they are taken to Karamarda hospital [in Jijiga] but usually they don’t come back. [137]

“Ahmed S.,” described the trauma associated with seeing the injuries of those who have been tortured: “five or six in my room are taken at night. The worst ones are the former ONLF fighters - some don’t come back, but those that do we can see their condition when they come back. It is indescribable. Many die in the following hours.”[138]

IV. Other Inhumane Prison Conditions

Overcrowding

Former prisoners said that serious overcrowding in Jail Ogaden meant that they were forced to take turns sleeping or being packed tightly together when they tried to sleep. One man said, “When we sleep on our sides, we can’t turn over without asking your neighbor to stand up so we can both turn over.”[139] Kabbas and vice kabbas, at times, assigned positions and instructed prisoners how to arrange themselves given the severe space limitations.[140]

“Abdirizak F.,” a 42-year-old man and former prisoner, told Human Rights Watch about the role of his kabba in assigning people to sleep:

After the assessments, we would take turns sleeping. The kabba and his assistants would measure length of forearm and say two people can sleep there. When one person sleeps, one would stand. [141]

A number of prisoners described how infection and disease spread quickly due to the overcrowding and the many inmates who had open untreated wounds from torture.[142] Overcrowding seemed particularly bad up until 2012. Former inmates told Human Rights Watch that there were times where there would be mass releases of prisoners if overcrowding was reaching a breaking point.[143] Male interviewees consistently reported overcrowding, while some women reported similar overcrowding and at other times they reported adequate space.[144]

Inadequate Food

Former prisoners said that access to food was woefully inadequate and many described the lack of food as exacerbating the impact of torture and mistreatment.[145] Prisoners said inadequate food made it more difficult to recover from torture, leading to the death of some prisoners.[146]

Until 2011, family members could bring food to Jail Ogaden for prisoners, but in 2011 and 2012 families reported that the food was not reaching the prisoners. In the 2011 assessment video, prison guards described eating food that was brought by family members and intended for detainees. Former prisoners said that since 2013, food from outside is no longer permitted.[147]

There were reports of people bringing food to prisoners in Jail Ogaden and ending up getting arrested.[148] One former prisoner said, “Those who brought us food, they would beat them and say ‘you are bringing food to ONLF.’” [149]

Most prisoners who were in Jail Ogaden after 2013 described grossly inadequate food, particularly a lack of meat or other protein sources, and all described hunger as one of the biggest challenges they faced in the prison.[150]

Former prisoners told Human Rights Watch that prison officials sometimes also withheld food from prisoners as a form of punishment.[151] Sometimes kabbas would play a role in the distribution of food and some prisoners reported kabbas preventing them from receiving food as part of routine punishments.[152]

“Abdullahi D.,” a 28-year-old man and former prisoner, described how desperate the food situation was in year 2014 in his room:

There was one injera per day and they would divide it for four people. People were desperate, everyone was starving. One guy was sick and vomited. Another guy started eating the vomit. And then the guard came and started hitting him. I saw all of this.[153]

Nine former prisoners described an incident in 2013, when Caynsane [Caynsane Sheikh Mohamed] was in charge of Jail Ogaden, when food was severely restricted for all prisoners for around one week as punishment.[154] All nine of the former prisoners described people dying during this incident.

“Ahmed L.,” a 38-year-old man and former prisoner, said: