Summary

I hope that my children will go back to school, and become better people, because they can’t do that working in tobacco farming. Tobacco growing is a very difficult field. It makes one grow old before their time.

— Anne, 36-year-old hired tobacco worker and mother of three child tobacco workers, ages 11, 13, and 15, December 2016

In November 2017, President Robert Mugabe’s 37-year rule of Zimbabwe came to an end on the back of military intervention, and Emmerson Mnangagwa, his former deputy, took office as the country’s new president. In an inauguration address delivered in Harare on November 24, 2017, Mnangagwa outlined his plans to help the country’s troubled economy recover, saying, “Our economic policy will be predicated on our agriculture, which is the mainstay.” He added, “Our quest for economic development must be premised on our timeless goal to establish and sustain a just and equitable society firmly based on our historical, cultural and social experience, as well as on our aspirations for better lives for all our people.”

Tobacco farming is a pillar of Zimbabwe’s economy. Tobacco is the country’s most valuable export commodity—generating US$933.7 million in 2016—and the crop is particularly significant to Zimbabwean authorities’ efforts to revive the economy. However, Human Rights Watch research in 2016 and 2017 into conditions on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe revealed an industry tainted by child labor and confronted by other serious human rights problems as well. Zimbabwean authorities and tobacco companies should take urgent steps to address child labor and other human rights abuses that may be undermining the sector’s contributions to economic growth and improved livelihoods.

In March 2017, Human Rights Watch met Panashe, a 50-year-old small-scale tobacco farmer in Manicaland, and one of 125 people involved in tobacco production interviewed for this report. Panashe supported his family with earnings from cultivating a half hectare of tobacco. In 2016, he did not make any profit. “Last year, we had the problem of hail, and we failed to get anything,” he said. Without any earnings from the previous season, Panashe said he was unable to pay workers to help on his farm: “We face the problem of labor. In tobacco, you cannot work alone…. I cannot manage to hire workers because I don’t have anything.” As a result, he relied on help from his 16-year-old daughter and 12-year-old niece. “They do everything,” he said. “They are overworked.”

Panashe described how he and his wife often felt sick while working in tobacco farming, suffering headaches and dizziness—both symptoms consistent with acute nicotine poisoning, which happens when workers absorb nicotine through their skin while handling tobacco plants. No one had ever informed Panashe or his family about nicotine poisoning, or how to prevent and treat it, even though he and his wife both suffered symptoms frequently. “I haven’t ever heard about it,” he said. “I haven’t heard of anyone knowing about this.” He also said he handled pesticides without adequate protective equipment, and sometimes suffered chest pain and blurred vision. “It really does affect us,” he said.

This report—based on extensive field research and interviews with 64 small-scale tobacco farmers like Panashe, as well as 61 hired workers on tobacco farms in the largest tobacco-growing provinces in Zimbabwe—found several serious human rights problems in the tobacco sector. Many children under 18 work in hazardous conditions on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe, often performing tasks that threaten their health and safety or interfere with their education. Adults involved in tobacco production—both small-scale farmers and hired workers—face serious health and safety risks, but the government and tobacco companies are failing to ensure that workers have sufficient information, training, and equipment to protect themselves. Hired workers on some large-scale tobacco farms said they were pushed to work excessive hours without overtime compensation, denied their wages, and forced to go weeks or months without pay.

Zimbabwe is among the top tobacco producers in the world. Tobacco production is central to the country’s economy, and tens of thousands of small-scale farmers, and thousands of hired workers on tobacco farms, rely on tobacco cultivation for their livelihoods. Yet, the government of Zimbabwe is failing to meet its international human rights obligations to protect children’s rights and is also failing to tackle other workers’ rights abuses in the tobacco sector. As President Mnangagwa’s administration strives to promote Zimbabwe’s economic growth, authorities should address human abuses faced by the small-scale farmers and hired workers sustaining the tobacco industry.

Tobacco companies also have an important role in respecting human rights in Zimbabwe’s tobacco sector. Many major global tobacco product manufacturers, such as British American Tobacco, and leaf merchant companies like Alliance One International and Universal Leaf Tobacco who supply to other major manufacturers, purchase tobacco in Zimbabwe. Human Rights Watch contacted these companies and 28 others regarding human rights concerns in tobacco farming in Zimbabwe and requested information about the policies and systems companies have in place to identify, prevent, and address human rights abuses in their supply chains.

Most companies, including nearly all of the major global tobacco companies, said they have detailed human rights due diligence policies in place and gave overviews of their efforts to conduct training on and monitoring of those policies in Zimbabwe. Human Rights Watch’s research, however, found that small-scale farmers and hired workers on some large-scale tobacco farms faced abuses that these policies intend to prevent and remedy. Our research suggests companies are generally not doing enough to prevent and address human rights abuses throughout the supply chain.

Companies should review their human rights policies to ensure training and communication of standards to all farmers and workers, including in remote areas, using clear, straightforward materials and methods; ensure all workers and farmers are provided written contracts, with labor requirements and protections clearly articulated, and receive copies of these contracts; and that company representatives, especially field staff visiting farms, are adequately trained and held accountable for communicating standards to farmers and workers and implementing human rights policies throughout the supply chain.

Understanding the effectiveness of company policies, implementation, and monitoring is hindered by the fact that none of the companies that Human Rights Watch contacted for this report have publicly disclosed sufficient and detailed information about how they apply their policies to their supply chain, how they monitor to prevent or address problems, or how they evaluate their efforts to address human rights concerns in their supply chains. Transparency is a crucial element of effective human rights due diligence and facilitates external assessments of the effectiveness of companies’ human rights policies.

With respect to child labor, most tobacco companies that Human Rights Watch contacted now have policies prohibiting children from performing most tasks in which they have direct contact with green tobacco, a significant step toward protecting children from health hazards such as nicotine poisoning. However, none of the companies contacted for this report prohibit children from all contact with tobacco, including handling dried tobacco, which Human Rights Watch research in Zimbabwe and other countries has linked to respiratory symptoms, such as coughing, sneezing, difficulty breathing, or tightness in the chest, and other adverse health impacts on children. Human Rights Watch calls on all companies and the government of Zimbabwe, to prohibit children from any work involving contact with tobacco, as a policy that is both maximally protective and the most straightforward for companies to communicate, implement, and monitor throughout the supply chain.

***

Farmers have cultivated tobacco in Zimbabwe for more than a century. Though the volume of production fluctuates from year to year based on economic and political factors and weather, in 2016, the last year for which data is available, Zimbabwe was the world’s sixth-largest producer of tobacco.

Poverty in Zimbabwe is widespread, particularly in rural areas. In 2011, nearly three-quarters of the population lived below the national poverty line. A cash shortage in recent years has crippled the economy, leading the nation’s Central Bank to impose limits on cash withdrawals and to introduce a form of local currency—bond notes—triggering widespread fears of inflation and further economic deterioration.

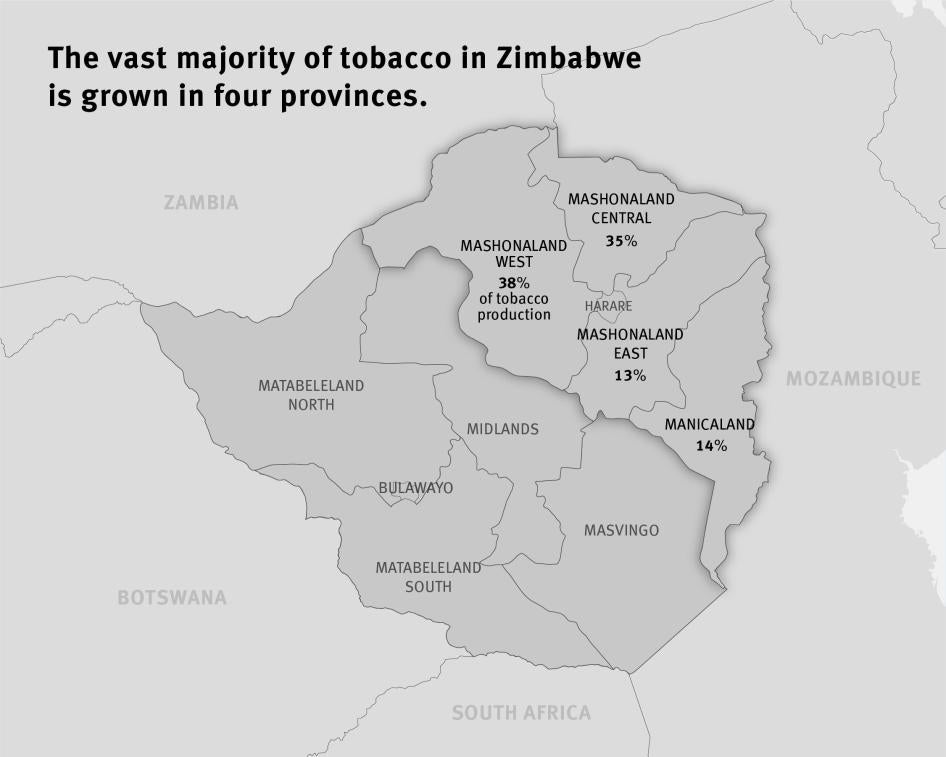

The controversial “fast track” land reform program introduced in 2000 by the ruling party—the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF)—has radically altered the nature of tobacco production in Zimbabwe. Under the program, the government seized thousands of large-scale commercial farms owned by white farmers and redistributed plots of land, including many that were given to landless black Zimbabweans. Since the start of the fast track land reform process, the number of active tobacco growers in Zimbabwe increased dramatically, from around 8,500 growers in 2000, to more than 73,000 in 2016, at least in part due to the government subdividing and redistributing some large farms. Zimbabwe’s Tobacco Industry and Marketing Board (TIMB) reports that 99 percent of tobacco is grown in one of four provinces: Mashonaland West, Mashonaland Central, Mashonaland East, and Manicaland.

Child Labor in Tobacco Farming

Human Rights Watch interviewed 14 child tobacco workers, ages 12 to 17, as well as 11 young adults, ages 18 to 22, who started working in tobacco farming as children. In addition, many other interviewees told Human Rights Watch that children work on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe. More than half of the 64 small-scale farmers interviewed for this report said that children under 18 worked on their tobacco farms—either their own children or family members, or children they hired to work on their farms. About half of the hired adult tobacco workers we interviewed said children under 18 worked with them, either also as hired workers, or informally assisting their parents, who were hired workers. Primary and secondary school teachers from tobacco-growing regions described to Human Rights Watch how children’s participation in tobacco farming contributed to absenteeism and made it difficult for their students to keep up with schoolwork.

In all of the provinces where Human Rights Watch conducted research, regardless of the size of farms or the nature of the work, interviewees explained that children work on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe due to poverty.

Zimbabwean law sets 16 as the minimum age for children to work in any sector and prohibits children under 18 from performing hazardous work. A 2001 amendment to the Children’s Act specifies several types of work that are considered hazardous work for children, including any work, “which is likely to jeopardise or interfere with the education of that child or young person” and any work “involving contact with any hazardous substance, article or process.” However, Zimbabwean law and regulations do not specifically prohibit children from handling tobacco.

Hazardous Work

Human Rights Watch found that work in tobacco farming in Zimbabwe poses significant risks to children’s health and safety, consistent with our findings in Kazakhstan, the United States, and Indonesia. Children working on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe are exposed to nicotine and toxic pesticides. They sometimes work very long hours handling green or dried tobacco leaves. The children interviewed for this report described sickness while working in tobacco farming, including specific symptoms associated with acute nicotine poisoning and pesticide exposure.

All of the child workers interviewed for this report said they had experienced at least one symptom consistent with acute nicotine poisoning—nausea, vomiting, headaches, or dizziness—while handling tobacco. For example, Davidzo, 15, started working on a neighbor’s tobacco farm with his grandmother when he was 14. He said he vomited the first time he worked with the crop in 2015. “The first day I started working in tobacco, that’s when I vomited. I was feeling that I didn’t have power,” he said describing how his body felt weak. Though he only vomited once, Davidzo said he often gets headaches while working with tobacco, especially when he carries the harvested leaves. “I started to feel like I was spinning,” he said. “Since I started this [work], I always feel headaches and I feel dizzy. I feel like I don’t have the power to do anything.”

Children are particularly vulnerable to nicotine poisoning because of their size, and because they are less likely than adults to have developed a tolerance to nicotine. The long-term effects of nicotine absorption through the skin have not been studied, but public health research on smoking suggests that nicotine exposure during childhood and adolescence may have lasting consequences on brain development.

In addition, many of the child tobacco workers interviewed for this report said they were exposed to pesticides while working on tobacco farms. Some children mixed, handled, or applied pesticides directly. Others were exposed when pesticides were applied to areas close to where they were working, or by re-entering fields that had been very recently sprayed. Many children reported immediate illness after having contact with pesticides.

Sixteen-year-old Tanaka described how he got sick after he poured a chemical used to help color the tobacco leaves into a backpack sprayer and applied it to the crop. “The smell affects me,” he said. “It stays with me and only clears after I take a bath. It causes nausea, and you lose your appetite.” He said he had experienced the feeling many times, most recently three days prior to his interview with Human Rights Watch. He said he wore overalls and a coat, but he had no gloves and nothing to cover his nose and mouth.

Rufaro and Zendaya, both 15, worked together on a tobacco farm in Mashonaland Central. Both girls said they had vomited after entering fields that had just been sprayed. “[It happens] when they spray the chemicals. It’s because of the smell. It’s so bad,” said Zendaya. “Most of the people, they vomit,” added Rufaro. “We were working in fields that had been sprayed. We were picking worms [off of the leaves]. They spray first, and then the worms come out, and then we go [into the field] and get them. Every time they spray, people go home sick [after work].”

Pesticide exposure has been associated with long-term and chronic health effects including respiratory problems, cancer, depression, neurologic deficits, and reproductive health problems. Children are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of toxic exposures as their brains and bodies are still developing.

Several children also reported respiratory symptoms while working with dried tobacco, such as coughing, sneezing, difficulty breathing, or tightness in the chest. Fungai, 16, worked on five tobacco farms in Mashonaland Central, where he lived with his mother and two older siblings. He said he suffered respiratory symptoms while grading dried tobacco: “During grading, you’re sneezing and having trouble breathing. It’s the smell of the tobacco. Once it hits you it’s like you’ve been burned.”

Child Labor and Education

Zimbabwe has committed to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which sets a target for all countries to offer all children free, equitable, and quality primary and secondary education by 2030. The goals are also in line with the country’s international and regional human rights obligations to realize the right to primary and secondary education for all. While Zimbabwe’s constitution requires the government to promote “free and compulsory basic education for children,” many families have to pay fees or levies for their children to go to public schools. Children are only required to attend school through age 12, even though the minimum age to begin working is 16. The compulsory education age is low relative to many other countries in the African Union, and Human Rights Watch research suggests that children in Zimbabwe face barriers to completing their compulsory education and accessing secondary school.

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that primary school fees were typically $10 to $15 per term, and secondary school fees were higher—sometimes close to $150 for the first term, and $35 to $50 for subsequent terms. Parents, children, teachers, and worker advocates interviewed for this report said that school fees posed a barrier to children’s education, and many interviewees said the fees became prohibitively expensive for their families, particularly in secondary school. Some interviewees said school administrators sent children home, or refused to provide end-of-year exam results if school fees were unpaid. Interviewees also described how indirect educational costs for things like books and uniforms posed a challenge for many families.

It was beyond the scope of this report to investigate barriers in access to primary and secondary education across all sectors, as the focus of our research was child labor and human rights abuses on tobacco farms. In research in other countries, Human Rights Watch has found that school fees pose a barrier to education for many children. In Zimbabwe, the difficulties accessing education because of school fees likely affect many low-income families outside of the tobacco sector, though our research suggests children in small-scale tobacco farming families may face particular risks continuing their education, due to the nature of their financial cycles. Many small-scale tobacco farmers told Human Rights Watch that they received earnings only during one part of the year after selling tobacco, and therefore often struggled to pay school fees at the start of the academic term beginning in January. Small-scale farmers in other types of agricultural production may face similar challenges due to their financial cycles.

Teachers in tobacco growing regions told Human Rights Watch that their students were often absent during the tobacco growing season, particularly during the labor-intensive periods of planting and harvesting, making it difficult for them to keep up with their school work. Joseph, a grade 5 teacher in Mashonaland West, said one-quarter of his 43 students worked on tobacco farms. “It causes a lot of absenteeism,” he said. “You find out of 63 days of the term, a child is coming 15 to 24 days only,” he said.

Northern Tobacco, in its 2017 monitoring of one tobacco-growing region from which it sources in Zimbabwe, confirmed high rates of absenteeism due to farmers’ difficulty paying school fees and risks of child labor during the most labor-intensive tobacco farming periods.

Some children missed school to work for hire on tobacco farms to raise money for their school fees. For example, Davidzo, a 15-year-old boy in Mashonaland Central, missed 15 days of class to work in tobacco farming. He said, “I had to absent myself from school because I needed school fees.” When he returned to school, he was punished by his teachers. “I was beaten…. I was so disappointed because I was trying to make an effort to work to raise my school fees. I thought I was doing good for myself.” Davidzo said he could not continue to secondary school due to the recurring challenge of paying school fees, so he dropped out.

Other interviewees said children missed school to help their own families with tobacco farming tasks. Some children and young adults interviewed for this report had never attended school or had dropped out before completing their desired level of education to work in tobacco farming. In most of these cases, interviewees said families were unable to cover the cost of their school fees. “I stopped [school] at grade 6,” said, Farai, a 14-year-old tobacco worker in Mashonaland Central. “We couldn’t afford to pay the fees. It was very painful.”

Health and Safety Risks for Adult Tobacco Workers

Like the child workers we interviewed, adult tobacco workers—both small-scale farmers and hired workers on farms of various sizes—were exposed to nicotine and toxic pesticides while working, and many suffered health effects that they attributed to their work on tobacco farms. Interviewees reported that neither government officials nor company representatives had provided them with adequate information about nicotine poisoning and pesticide exposure, or with sufficient training to protect themselves. They also said that they were not provided with, and often lacked the means to procure equipment necessary to protect themselves.

Almost none of the small-scale farmers or hired workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch knew about acute nicotine poisoning, or Green Tobacco Sickness (GTS), or how to protect themselves from it. However, most had experienced symptoms consistent with nicotine poisoning while working, including nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, headaches, and dizziness. Even the contract farmers interviewed for this report, who regularly met with representatives of tobacco companies, had very little, if any, information about nicotine poisoning.

For example, Admire, a 43-year-old tobacco farmer from Manicaland, had sold tobacco through a contract with a tobacco company for seven years, yet he said no one from the company ever informed him about GTS, even though he and most of his family members had suffered symptoms consistent with nicotine poisoning. Admire said his 17-year-old son had even vomited while handling tobacco. “When we’re hanging tobacco, we normally feel weak or vomit, and get a headache and dizziness,” he said. “We have never heard that kind of education,” he said. “You fall sick, but you don't know what it is.”

Nearly all small-scale farmers and many hired farmworkers interviewed for this report said they handled toxic chemicals while working on tobacco farms. While most small-scale farmers and hired farmworkers had some understanding that pesticides could be dangerous, many had not received comprehensive education or training about how to protect themselves and other workers from exposure. Many interviewees handled chemicals without any protective equipment, or with improper or incomplete protection. Interviewees reported illness after coming into contact with toxic chemicals, including nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, stomach pain, headaches, dizziness, skin irritation (particularly of the face), chest pain, blurred vision, eye irritation, respiratory irritation, and other symptoms. Zimbabwean regulations require employers to ensure that workers handling hazardous substances, including pesticides, are informed about the risks of the work, and provided with proper protective equipment.

Union organizers in multiple provinces told Human Rights Watch that the lack of protective equipment was a chief concern among the workers on farms they served. At the time of writing, stakeholders were working to develop a regulation on health and safety in the agricultural sector. In the absence of this regulation, the legal and regulatory framework has lacked comprehensive safety and health protections for agricultural workers, leaving them particularly vulnerable to occupational illnesses and injuries.

Labor Rights Abuses

Human Rights Watch documented serious labor rights abuses on large-scale tobacco farms, including excessive working hours without overtime compensation and late or non-payment of wages.

Many of the hired workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, including some children, said employers pressured them to work past their designated working hours without additional compensation. Some workers said they were asked to work on Sundays, their designated rest days, without overtime compensation or compensatory time off (the ability to take another day to rest). While some workers said overtime work was voluntary, others said they feared reprisals for refusing to work overtime, citing examples of fellow employees who had been dismissed from work for several days, or permanently, after declining to work overtime.

Many workers reported that employers delayed payments to workers, from a few days up to weeks or months. On some farms, when employers delayed wage payments, they allowed employees to buy basic foodstuffs and household goods on credit in employer-owned shops, sometimes at inflated prices. The money spent in these shops was then deducted from their wages. In the absence of wages, several workers explained that they had no choice but to acquire essential items through their employers. Some workers said they were paid less than they were owed or promised, without explanation.

In many cases, the incidents described to Human Rights Watch appear to constitute violations of Zimbabwean labor law and regulations. The 2014 collective bargaining agreement for the agricultural industry stipulates that agricultural workers should not exceed 208 hours of work per month, and requires employers to pay “double the employee’s current wage” for overtime worked on a day off, and “one and a half times the employee’s current wage for time worked in excess of the ordinary monthly hours of work.” The agreement requires employers to provide wages in cash within two to four days of the end of the working period (week or month, respectively).

Other Human Rights Problems

Very few of the hired workers on small or large-scale farms who were interviewed for this report said they had ever seen a labor inspector or other government official visit their workplace to inspect working conditions. Most workers said that as far as they knew, union organizers were the only people to inspect conditions at their workplaces and speak with them about grievances. In response to Human Rights Watch’s request for information regarding labor inspection in the agricultural sector, the Zimbabwean government stated that it has 120 labor inspectors, and carried out 2,500 labor inspections in all sectors between 2015 and early 2018. It reported that “no record of any violations were received,” though it reported that a 2014 labor force survey found the prevalence of child labor across sectors is around 4.6 percent. According to the government’s response, there were “no cases of child labour in the tobacco sector which the government is aware of.”

According to the US Department of Labor (DOL), the Zimbabwean government carried out 866 labor inspections at worksites in 2016 and documented 436 child labor violations in all sectors that year. DOL maintained that the Zimbabwean government lacked sufficient labor inspectors to enforce labor laws effectively.

Among the small-scale contract farmers interviewed for this report, many reported that they did not receive copies of the contracts they signed with tobacco companies, leaving them vulnerable to risks if a company was to modify the terms of a contract unilaterally, or deny the existence of a contractual relationship. Many farmers told Human Rights Watch that only company representatives retained a copy of the contract agreements. Human Rights Watch did not document any instances of companies unilaterally modifying the terms of a contract or denying the existence of a contract.

Many farmers said there were provisions of the contract that they did not understand or that company representatives did not explain to them. Some farmers said they felt rushed during the contract-signing process and did not have sufficient time to understand fully their contractual requirements. For example, Winston, a 28-year-old farmer in Mashonaland Central, said, “The form is too long. They just tell you where to sign. Reading and understanding it, that's another thing altogether.” Winston said he was part of a group of 10 farmers who were all contracted with the same company. He said a company representative asked them to sign their contract forms as a group: “Normally, they only have an hour to get us to sign the forms. He [the company representative] attends to us as a group…. 10 farmers in one hour. He’ll be telling you he’s in a hurry.”

The Tobacco Supply Chain

Tobacco grown in Zimbabwe enters the supply chains of some of the world’s largest tobacco companies. Companies sourcing tobacco from Zimbabwe have a responsibility to ensure that their business operations do not contribute to child labor and other human rights abuses, in line with the United Nations (UN) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Human Rights Watch shared its findings with the largest tobacco companies operating in Zimbabwe and requested information about their human rights policies and practices. Based on the responses we received and publicly-available information, we analyzed current practices regarding human rights due diligence in the tobacco industry in Zimbabwe.

Since 2004, Zimbabwe has had two systems for the sale of tobacco: contract farming and auction. In 2016, the last year for which data is available, contract tobacco sales accounted for 82 percent of Zimbabwe’s total tobacco production, while auction sales accounted for 18 percent.

Under the auction system, tobacco growers independently cover the costs associated with cultivation, deliver their crop to an auction floor of their choice, and sell it to the highest bidder. Under the contract farming system, farmers sign contracts agreeing to sell tobacco leaf to specific companies. The companies provide the inputs required for tobacco production, such as seeds and chemicals, and guarantee to buy all the tobacco contracted at prices equal to or higher than those offered on the auction floors at the end of the season.

Human Rights Watch wrote to 31 tobacco companies, including the eight companies that accounted for 86 percent of the tobacco purchase market share in Zimbabwe in 2016. We also wrote to several companies with whom we had previously corresponded regarding child labor on tobacco farms in other countries. The companies included 12 multinational tobacco companies: Altria Group, Alliance One International (AOI), British American Tobacco (BAT), China National Tobacco Corporation, Intercontinental Leaf Tobacco (ILT), Contraf Nicotex Tobacco GmbH (CNT), Imperial Tobacco (Imperial), Japan Tobacco International (JTI), Rift Valley Corporation/Northern Tobacco (NT), Premium Tobacco Group (Premium)/Premium Tobacco Zimbabwe (PTZ), Philip Morris International (PMI) and Universal Corporation (Universal); and three Zimbabwean tobacco leaf merchant companies: Boostafrica Traders (Boostafrica), Chidziva Tobacco Processors (Chidziva), and Curverid Tobacco Limited (Curverid). We did not contact other Zimbabwean companies with smaller market shares.

Altria Group and Philip Morris International stated that they do not purchase tobacco in Zimbabwe. Intercontinental Leaf Tobacco, and China National Tobacco Company, which operates in Zimbabwe through its wholly-owned subsidiary, Tian Ze, did not respond to Human Rights Watch. Boostafrica responded to Human Rights Watch but requested that the response be kept confidential.

Human Rights Watch also wrote to 16 additional companies authorized to purchase tobacco from auction floors in Zimbabwe in 2017. None of these companies responded to our letters.

Most tobacco companies purchasing tobacco in Zimbabwe that responded to Human Rights Watch stated they have detailed child labor and labor policies in place, including a prohibition on children performing most tasks involving contact with green tobacco, which they implement in their direct contracting. Companies also consistently stated that they have systems in place to monitor implementation of these policies and to take action in the event of identification of non-compliance, largely focused on correction and improvement, with the option of non-renewal of contract in the event of serious abuses or ongoing non-compliance.

No company that responded to Human Rights Watch indicated that they conduct any type of human rights due diligence in the auction system. Several companies, including Imperial and Universal, acknowledged the difficulty or impossibility of monitoring labor conditions among growers who sell tobacco on auction floors.

For contracted growers, in their responses to Human Rights Watch, all companies said that they provide training on health and safety through group meetings with farmers in farming communities and during visits to farms by company technicians. Topics include GTS, pesticide and chemical use, the use of protective equipment, as well as the prohibition of child labor. Few of the contracted farmers interviewed by Human Rights Watch stated that they had received the type of comprehensive training described by the companies. Most farmers stated that they had received some training and education about health and safety on pesticides. No farmers stated that they had received sufficient personal protective equipment from the contracting company, and few had purchased complete equipment themselves, due to the costs. Very few said they had comprehensive information about nicotine poisoning or GTS and how to prevent it; most had never heard of GTS. Some farmers stated that they received information about child labor, although many had not. Very few reported any known penalties for children performing hazardous work. Other farmers said that company representatives who visited farms largely, or exclusively, shared information related to successful tobacco cultivation.

Hired farmworkers on large-scale contract farms told Human Rights Watch that company representatives visited the farms where they worked, but that representatives spoke only with farm management, not workers. Many hired workers said their employers did not provide them with complete or effective protective equipment.

Human Rights Watch found that while companies made an effort to provide overviews and some details of their efforts in response to our inquiries, they did not disclose sufficient information to allow for external stakeholders to make an objective assessment as to whether a company is identifying key human rights problems, addressing them effectively, and improving human rights compliance in its supply chain. Northern Tobacco, one of the largest buyers of tobacco in Zimbabwe, provided the most complete report of the methods and outcomes of monitoring in 2017 in one tobacco growing region in Zimbabwe, which can serve as a good example of transparent reporting.

None of the companies contacted publish sufficient information on their websites or otherwise. Publishing clear, comprehensive information about a company’s monitoring system is an essential component of effective due diligence and sends a message that companies are willing to be accountable when human rights abuses are found in their supply chain.

Key Recommendations

To the Government and the Parliament of Zimbabwe

- Revise the list of hazardous occupations for children set out in the 2001 amendment to the Children’s Act, or enact a new law or regulation, to explicitly prohibit children from working in direct contact with tobacco in any form.

- Vigorously investigate and monitor child labor and human rights violations on tobacco farms, including small-scale farms.

To the Ministry of Health and Child Care

- Develop and implement an extensive public education and training program to promote awareness of the health risks of work in tobacco farming. At a minimum, ensure that the program includes information on the risks of exposure to nicotine, pesticides, and the special vulnerability of children; prevention and treatment of acute nicotine poisoning (Green Tobacco Sickness); the safe handling and storage of pesticides; methods to prevent occupational and take-home pesticide exposure; and the use of personal protective equipment.

To All Companies Purchasing Tobacco from Zimbabwe

- Adopt a global human rights policy prohibiting the use of child labor anywhere in the supply chain, if the company has not yet done so. The policy should specify that hazardous work for children under 18 is prohibited, including any work in which children have direct contact with tobacco in any form. The policy should also include specific provisions regarding labor rights and occupational safety and health.

- Conduct regular and rigorous monitoring in the supply chain for child labor and other human rights risks, and engage entities with expertise in human rights and child labor to conduct regular third-party monitoring in the supply chain.

- Regularly publish detailed information about internal and external monitoring in a form and frequency consistent with the guidelines on transparency and accountability in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted field research for this report in 2016 and 2017 in five provinces of Zimbabwe: Harare, Mashonaland West, Mashonaland Central, Mashonaland East, and Manicaland.

We interviewed 125 people involved in tobacco farming in Zimbabwe, including 64 small-scale tobacco farmers and 61 hired workers on tobacco farms of various sizes. Human Rights Watch interviewed 14 child workers, ages 12 to 17, and 11 young adults, ages 18 to 22, who started working on tobacco farms as children. Human Rights Watch did not seek to interview owners of large-scale farms.

In addition, we interviewed 22 other individuals, including representatives of nongovernmental organizations and trade unions, teachers, school administrators, journalists, and others. In total, Human Rights Watch interviewed 147 people for this report.

Human Rights Watch identified interviewees through outreach in tobacco farming communities, and with assistance from journalists and independent organizations. The small-scale farmers and hired workers we interviewed may not be representative of the broader population of tobacco workers nationwide. Still, Human Rights Watch observed patterns and similarities in our field research in multiple provinces, which we present in this report. We make no claims about the prevalence of child labor or the other human rights abuses we documented, but we describe patterns of abuses that may be present across the tobacco sector.

Interviews were conducted in English or Shona, at times with help from interpreters. Human Rights Watch held most interviews individually and in private, though some people were interviewed in pairs or small groups. Interviews were held primarily in homes or in the offices of independent organizations assisting with our research. Some participants were interviewed in public spaces in their communities or near tobacco auction floors in Harare. No one was interviewed in the presence of their employer or any government official.

Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be collected and used. Interviewers assured participants that they could decline to participate, end the interview at any time, or decline to answer any questions, without any negative consequences. All interviewees provided verbal informed consent to participate. Some interviewees chose not to share their names with Human Rights Watch for security reasons. The names of all interviewees quoted in this report have been changed to protect their safety.

Human Rights Watch did not provide anyone with compensation in exchange for an interview. We provided funds to our partner organizations to reimburse the costs of transportation for all interviewees who traveled to central locations to meet with us. We also provided modest meal stipends to those who spent several hours in transit to participate in interviews.

Interviews were semi-structured and covered topics related to tobacco production in Zimbabwe, health and safety, and access to education for children. Most interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes, and all interviews took place in person. All the accounts reported here, unless otherwise noted, reflect experiences interviewees had on tobacco farms in 2016 or 2017.

Human Rights Watch also analyzed relevant laws and policies and conducted a review of secondary sources, including public health studies, reports prepared by the Zimbabwean government and international groups, and other sources.

Due to security concerns for interviewees, and the difficult environment in Zimbabwe for civil society activists, we did not reach out to government officials until we had concluded our interviews with tobacco workers. In September 2017, and again in January 2018, we sent letters to Zimbabwean authorities, including the Office of the President and Cabinet; the Ministry of Agriculture, Mechanisation, and Irrigation; the Ministry of Environment; the Ministry of Health and Child Care; the Ministry of Justice and Legal Affairs; the Ministry of Lands, Land Reform, and Resettlement; the Ministry of Media, Information, and Publicity; the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education; and the Ministry of Public Service, Labour, and Social Welfare. The Ministry of Health and Child Care, the Ministry of Lands, Land Reform, and Resettlement, and the Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare responded acknowledging that they received our letters. In March 2018, Human Rights Watch received a response from the Ministry of Public Service, Labour, and Social Welfare via an email from a labor officer. We did not receive responses from any other government entities. We published our correspondence with the government in an appendix to this report on the Human Rights Watch website.

In August and September 2017, Human Rights Watch sent letters to 31 tobacco product manufacturing and leaf supply companies. These include the companies responsible for 86 percent of the market share of tobacco purchases in Zimbabwe in 2016, as well as some of the world’s largest multinational tobacco companies Human Rights Watch had previously met and corresponded with regarding child labor in tobacco farming in other countries.[1] In the letters, we shared our research findings and requested information about each company’s human rights policies and practices. Thirteen companies responded. In December 2017, Human Rights Watch exchanged additional correspondence with several of the companies. We published our full correspondence with the companies in the appendix to this report, available on the Human Rights Watch website.

Terminology

In this report, “child” and “children” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law.

The term “child labor,” consistent with International Labour Organization standards, is used to refer to any work performed by children below the minimum age of employment or children under age 18 engaged in hazardous work.

Throughout the report, we use the terms “hired worker” or “hired farmworker” to refer to individuals paid to work on tobacco farms of various sizes. In general, we use the term “farmer” to refer to the person with primary responsibility for a farm’s operations. We use the term “worker” to refer to any individual involved in tobacco production, including family workers and hired workers.

We use the term “small-scale farm” to refer to farms that cultivated three hectares of tobacco or less (some were communal farms, and some were A1 farms, as explained in Section I). We use the term “large-scale farm” to refer to larger farms ranging in size from several dozen to several hundred hectares that required a large workforce (some were large-scale commercial farms, and some were A2 farms). Some children and adults interviewed for this report were unable to specify the size of the farms where they worked, so we asked them to estimate the number of workers to give a sense of the scale.

I. Background

Farmers have cultivated tobacco in Zimbabwe for more than a century.[2] Though the volume of production fluctuates from year to year based on economic and political factors and weather, in 2016 Zimbabwe was the world’s sixth-largest producer of tobacco and is consistently one of the largest producers in Africa.[3] In November 2017, following military intervention, Emmerson Mnangagwa succeeded Robert Mugabe as president and pledged to pursue economic recovery through an economic policy “predicated on our agriculture.”[4]

In a context marked by broader economic challenges, tobacco production remains a pillar of Zimbabwe’s economy; it is the country’s most valuable export commodity, with tobacco exports generating more than US$933 million in 2016.[5] According to the Tobacco Industry and Marketing Board (TIMB), a body established to “control and regulate the marketing of tobacco in Zimbabwe,” more than three-quarters of Zimbabwe’s tobacco is exported.[6] Tobacco from Zimbabwe is exported to 62 countries. Top export destinations include China (responsible for 42 percent of the country’s tobacco exports), South Africa, Belgium, United Arab Emirates, and Indonesia.[7]

Economic Context

The Zimbabwean Ministry of Agriculture reports that agriculture provides livelihoods to 80 percent of the country’s 15.6 million people, accounting for 14 to 18.5 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 33 percent of foreign earnings.[8] Poverty in Zimbabwe is widespread, particularly in rural areas.[9] In 2011, the last year for which data is available, nearly three-quarters of the population lived below the national poverty line, and more than one in five Zimbabweans survived on less than $1.90 per day.[10]

Major droughts in 2015 and 2016 reduced agricultural output and exacerbated rural poverty.[11] A cash shortage in recent years has crippled the economy, leading the Central Bank to impose limits on cash withdrawals and to introduce bond notes—a form of local currency—triggering widespread fears of inflation and further economic deterioration.[12]

At the start of the tobacco sales season in 2017, government officials praised tobacco farmers, calling them “heroes,” and projected that tobacco sales could boost Zimbabwe’s troubled economy.[13] However, tobacco sales and earnings in 2017 fell short of government projections, likely due to excessive rainfall.[14]

Land Reform

The controversial “fast track” land reform program, introduced in 2000 by the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), radically altered the nature of tobacco production in the country.[15] Under the program, the government announced it would seize thousands of large-scale commercial farms owned by white farmers and redistribute plots of land to landless black Zimbabweans. In the chaotic process that followed, in some cases veterans of Zimbabwe’s liberation war and militias loyal to the ruling party invaded farms and seized lands that they then redistributed in a highly politicized and largely unregulated process, at times carrying out serious acts of violence.[16]

By 2009, the government had expropriated 10 million hectares of agricultural land (more than 6,000 properties), and allocated plots to more than 168,000 beneficiaries, creating nearly 146,000 new smallholder (known as A1) farms and nearly 23,000 new larger-scale (A2) farms.[17] Since the start of the fast track land reform process, the number of active tobacco growers in Zimbabwe increased dramatically, from around 8,500 growers in 2000, to more than 73,000 in 2016.[18] TIMB assigns tobacco growers one of four designations based on the land they farm: A1 resettlement farms, A2 resettlement farms, communal farms (small-scale farms where residents traditionally practiced subsistence agriculture), or commercial farms. Almost half of all registered growers in 2016 farmed in communal areas.[19]

Tobacco Production in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe’s Tobacco Industry and Marketing Board (TIMB) reports that nearly all of the country’s tobacco is grown in one of four provinces: Mashonaland West (38 percent), Mashonaland Central (35 percent), Manicaland (14 percent), and Mashonaland East (13 percent).[20]

Tobacco Farming and Curing Process

Flue-cured tobacco, a type of tobacco that is dried in heated curing barns, is the most common type of tobacco leaf grown in Zimbabwe.[21] Human Rights Watch interviewed people involved in flue-cured tobacco production on small-scale farms and larger commercial farms. The tobacco farming and curing process differed slightly depending on the size of the farm, the size of the labor force, and the level of mechanization.

On small-scale farms (A1 or communal farms), farmers interviewed by Human Rights Watch typically planted between one-half of a hectare and three hectares of tobacco to sell for profit. Many of these farmers also grew maize, vegetables, or other crops for subsistence. Most small-scale tobacco farmers relied primarily on family labor, and then hired daily workers to assist with tasks at labor-intensive points of the growing season, such as planting, harvesting, and grading. In the description that follows, we refer to all individuals working in tobacco farming as “farmworkers,” a term that includes farmers, their family members who worked on their farms, and hired workers involved in tobacco production.

For small-scale farmers who lacked irrigation equipment, the tobacco growing season began with the preparation of seedbeds and fields sometime between June and September. At the onset of the rainy season in October or November, farmworkers transplanted tobacco plants into the fields. As the plants matured, farmworkers weeded the fields and applied pesticides and fertilizers to the crop as needed. Some farmworkers told Human Rights Watch they “topped” tobacco (removed large flowers that grew from the tops of plants) and removed “suckers” (nuisance leaves) to help the plant grow. When the plants had matured, usually between January and March, farmworkers harvested the leaves in stages, through a series of separate harvests, starting from the bottom of the plant. Farmworkers picked tobacco leaves by hand, carried them under their arms or stacked them on the ground in fields, and then carried them to carts to be transported to curing barns.

Flue-cured tobacco is dried in heated curing barns. Farmworkers typically tied or clipped tobacco leaves onto wooden sticks, and loaded the sticks into the rafters of brick curing barns heated by fire. Farmworkers maintained fires that distributed heat through pipes (“flues”) in barns. After several days, farmworkers removed the dried leaves, sorted them according to color and size (a process called “grading”), and then compressed them to form bales.

Tobacco production on large-scale farms (A2 or large-scale commercial farms) followed the same farming and curing process described above, though the scale of cultivation was significantly greater. Human Rights Watch interviewed hired farmworkers who worked on large farms between 25 and 600 hectares in size, which produced tobacco, as well as in some cases other crops such as maize or potatoes. These farms often had irrigation equipment that allowed farmworkers to begin transplanting tobacco seedlings into fields in September, before the start of the rainy season, and to harvest the crop earlier, beginning around December. Due to the considerable size of these farms, and the diversity of crops, farmers typically employed farmworkers all year, or for many months at a time. Workers often specialized in particular tasks, such as spraying pesticides, harvesting (reaping) tobacco, hanging tobacco in barns, or grading. Some of these farms used newly constructed metal barns (often called “tunnels” by workers) to cure tobacco.

Tobacco Supply Chain

Since 2004, Zimbabwe has had two systems for the sale of flue-cured tobacco: contract farming and auction. The Tobacco Industry and Marketing Board (TIMB) regulates both systems, “to ensure the orderly exchange of tobacco between the grower and the buyer,” including by determining the dates for tobacco sales to begin and end.[22]

Under the auction system, tobacco growers independently cover the costs associated with cultivation, deliver their crop to an auction floor of their choice, and sell it to the highest bidder. In the 2017 growing season, TIMB licensed three auction floors, all located in Harare: Tobacco Sales Floor (TSF), Boka Tobacco Floors (BTF), and Premier Tobacco Auction Floor (PTAF). TIMB authorized 24 entities to purchase tobacco from these floors.[23] Growers book a sales slot and deliver their crop to one of these floors, and a TIMB classifier judges the quality of the leaf. Different quality leaf earns different prices. TIMB regulates the buying and selling process and resolves any disputes between growers and buyers regarding the quality or price of the crop.[24]

In 2004, contract farming was introduced in Zimbabwe. Under this system, farmers sign contracts agreeing to sell tobacco leaf to specific companies. The companies provide the inputs required for tobacco production, such as seeds and chemicals, and guarantee to buy all the tobacco contracted at prices (per grade) equal to or higher than those prevailing on the auction floors at the end of the season, as required by the TIMB.[25] In 2017, TIMB authorized 20 companies to contract with tobacco growers in Zimbabwe.[26]

In 2016, the last year for which data is available, contract tobacco sales accounted for 82 percent of Zimbabwe’s total tobacco production, while auction sales accounted for 18 percent.[27] Sixty-five percent of growers sold their tobacco through contracts, while 35 percent sold through auction floors.[28]

II. Findings

Human Rights Watch documented instances of child labor on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe, including children under 18 performing hazardous work and children working as hired laborers below the national minimum age of employment. In addition, Human Rights Watch found that adults involved in tobacco production face serious health and safety risks, labor rights abuses, and other human rights problems.

Child Labor in Tobacco Farming

Children and young adults interviewed for this report described working in dangerous conditions on tobacco farms. In addition, many other interviewees told Human Rights Watch that children work on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe. More than half of the small-scale farmers interviewed for this report said that children under 18 worked on their tobacco farms—either their own children or family members, or children they hired to work on their farms. About half of the hired adult tobacco workers we interviewed said children under 18 worked with them, either also as hired workers, or informally assisting their parents, who were hired workers. Primary and secondary school teachers from tobacco-growing regions described to Human Rights Watch how children’s participation in tobacco farming contributed to absenteeism and made it difficult for their students to keep up with schoolwork.

Zimbabwean labor law sets 16 as the minimum age for children to be employed in any sector, and prohibits children under 18 from performing hazardous work.[29] In addition, the Children’s Act specifies that no parent or guardian may allow any child to engage in hazardous labor, or cause or allow “a child or young person of school-going age” to miss school in order to work.[30] Many companies purchasing tobacco from Zimbabwe have policies in place that prohibit children under 18 from performing many or most tobacco farming tasks, as detailed in Section IV of this report.

Some small-scale farmers said that company representatives or government workers had told them children under 18 were prohibited from working in tobacco farming. Others had never received information about hazardous child labor, health risks for children working in tobacco farming, or the minimum age for children to work. Most small-scale farmers we interviewed, even those who were aware of a rule regarding children’s participation in tobacco farming, said they were not aware of any penalties associated with child labor violations.

Human Rights Watch documented child labor in tobacco farming among both children who were still enrolled in school and children who had dropped out, most often in secondary school, or during the transition from primary to secondary school. In some cases, interviewees told Human Rights Watch that children under 18 worked only on their own families’ small-scale tobacco farms without pay.[31] Some children combined family labor and hired labor on other farms.[32] In other cases, interviewees said children were hired to work as paid laborers on tobacco farms of various sizes, including on some large-scale farms.[33]

The types of tasks children performed, and the nature of their work varied. Some interviewees said children performed only a few tasks on tobacco farms, while others said that children worked throughout the growing season and performed a range of tasks such as planting, weeding, harvesting, and grading tobacco.

Hazardous Child Labor in Tobacco Farming

While not all work is harmful to children, the International Labour Organization (ILO) defines hazardous work as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.”[34] The ILO considers agriculture “one of the three most dangerous sectors in terms of work-related fatalities, non-fatal accidents, and occupational diseases.”[35]

Zimbabwean law prohibits children under 18 from performing hazardous work, defined as, “any work which is likely to jeopardise that person’s health, safety or morals, which shall include but not be limited to work involving such activities as may be prescribed.”[36] A 2001 amendment to the Children’s Act specifies that hazardous work for children includes any work, “which is likely to jeopardise or interfere with the education of that child or young person”; “involving contact with any hazardous substance, article or process…”; “that exposes a child or young person to electronically-powered handtools, cutting or grinding blades”; and “that exposes a child or young person to extreme heat, cold, noise or whole body vibration….”[37] This list does not specifically prohibit children from handling tobacco. According to the ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR), the Zimbabwean government first indicated in 2003 that it was in the process of revising the list of types of hazardous work prohibited for children under 18, but it has not yet adopted any revisions.[38]

Human Rights Watch found that work in tobacco farming in Zimbabwe poses significant risks to children’s health and safety, consistent with our findings in Kazakhstan, the United States, and Indonesia.[39] Children working on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe are exposed to nicotine, toxic pesticides, and other dangers. All of the children interviewed for this report described sickness while working in tobacco farming, including specific symptoms associated with acute nicotine poisoning and pesticide exposure, as described below. Some children also reported health problems while working with dried tobacco. Some small-scale farmers described how their children experienced these symptoms while working on the family farm.

Based on our field research and analysis of international law and public health literature, Human Rights Watch has concluded that any work involving direct contact with tobacco in any form is hazardous and should be prohibited for children under 18.[40]

Nicotine Poisoning

All children interviewed for this report described handling and coming into contact with tobacco plants and leaves at various points in the growing season, and many other interviewees, including small-scale farmers and adult hired workers, said children performed farming tasks that involved direct contact with tobacco. Nicotine is a toxin that is present in tobacco plants and leaves in any form.[41] Public health research has shown that tobacco workers absorb nicotine through their skin while handling tobacco.[42] Studies have found that non-smoking adult tobacco workers have similar levels of nicotine in their bodies as smokers in the general population.[43]

In the short-term, absorption of nicotine through the skin can lead to acute nicotine poisoning, called Green Tobacco Sickness, an occupational health risk specific to tobacco farming. Green Tobacco Sickness occurs when workers absorb nicotine through their skin while having contact with tobacco plants, particularly when plants are wet.[44] Research has shown nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and headaches are the most common symptoms of acute nicotine poisoning.[45] All the child workers interviewed for this report said they had experienced at least one symptom consistent with acute nicotine poisoning while weeding in tobacco fields, pruning tobacco plants, removing suckers (nuisance leaves), harvesting leaves, carrying harvested leaves, putting tobacco leaves in clips, or working in curing barns.

For example, Davidzo, 15, started doing piece work on a neighbor’s tobacco farm with his grandmother when he was 14. He said he vomited the first time he worked with the crop in 2015. “The first day I started working in tobacco, that’s when I vomited. I was feeling that I didn’t have power,” he said describing how his body felt weak. Though he only vomited once, Davidzo said he often gets headaches while working with tobacco, especially when he carries the harvested leaves. “I started to feel like I was spinning,” he said. “Since I started this [work], I always feel headaches and I feel dizzy. I feel like I don’t have the power to do anything.”[46]

Fourteen-year-old Farai, who worked on his family’s tobacco farm and several neighbors’ farms in Mashonaland Central, described how he felt while harvesting tobacco. “I get headaches,” he said, placing both of his hands on his head. “When we are in the field, the sun is too hot, and my head starts to ache. Usually it starts around my eyes, and the pain moves around until it’s throbbing…. At times I have a sharp pain in my stomach when we are putting the leaves, carrying them to the tractor.”[47]

“When we’re plucking the suckers—maybe it’s because of the smell of the tobacco—what affects me is headaches,” said 15-year-old Zendaya, who also worked on several tobacco farms in Mashonaland Central. “[The pain], it’s in the forehead.” Rufaro, also 15, worked with Zendaya and described feeling lightheaded while removing suckers from tobacco plants. “You see dark,” she said. “You fail to see, and then you see dark… The problem is with the eyes.”[48]

Praise, a 17-year-old worker, also complained of headaches while working on a large-scale tobacco farm in Mashonaland West. “During the first harvest in December, … the odor of the leaves feels like it gets in your body. For three to four days you are feeling that same odor [in your body] and it causes headaches. You feel like the veins in your head want to come out. The pain is stretching all over your head.” He also said he suffered nausea while loading tobacco into “trolleys” for curing. “When we take the leaves into the trolleys, we have to work close to the leaves, so most of the time we feel nausea…. I felt like that strong odor settled on my chest, and I couldn’t eat. It moved downwards into my stomach,” he said.[49]

Acute nicotine poisoning generally lasts between a few hours and a few days,[50] and although it is rarely life-threatening, severe cases may result in dehydration which requires emergency treatment.[51] Children are particularly vulnerable to nicotine poisoning because of their size, and because they are less likely than adults to have developed a tolerance to nicotine.[52]

The long-term effects of nicotine absorption through the skin have not been studied, but public health research on smoking suggests that nicotine exposure during childhood and adolescence may have lasting consequences on brain development.[53] The prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for executive function and attention, is one of the last parts of the brain to mature and continues developing throughout adolescence and into early adulthood.[54] The prefrontal cortex is particularly susceptible to the impacts of stimulants, such as nicotine. Nicotine exposure in adolescence has been associated with mood disorders, and problems with memory, attention, impulse control, and cognition later in life.[55]

Exposure to Pesticides and Other Chemicals

Most child tobacco workers interviewed for this report said they were exposed to pesticides while working on tobacco farms. Some children mixed, handled, or applied pesticides directly. Others were exposed when pesticides were applied to areas close to where they were working, or by re-entering fields that had been very recently sprayed.[56] Many children reported immediate illness after having contact with pesticides. The 2001 amendment to the Children’s Act prohibits children under 18 from performing any work, “involving contact with any hazardous substance, article or process,”[57] and the Environmental Management Act of 2002 defines a “hazardous substance” as “any substance, whether solid, liquid, or gaseous, or any organism which is injurious to human health or the environment.”[58] Statutory Instrument 12 of 2007 outlines the Environmental Management Act’s regulations and specifically includes pesticides among the substances considered hazardous.[59] In its response to Human Rights Watch, the government confirmed that “the use of chemicals” would be considered hazardous work for children.[60]

Mercy, a 12-year-old child tobacco worker in Mashonaland Central, described how she applied pesticides to the small-scale farms where she worked: “We take the chemical and put it in the water. We carry the knapsack on our backs and start to spray. I feel like vomiting because the chemical smells very bad.” Mercy said her employer provided her with gloves to use while spraying, but she received no other protective equipment.[61]

Sixteen-year-old Tanaka described how he got sick after he poured a chemical used to help color the tobacco leaves into a backpack sprayer and applied it to the crop. “The smell affects me,” he says. “It stays with me and only clears after I take a bath. It causes nausea, and you lose your appetite.” He said he had experienced the feeling many times, most recently three days prior to his interview with Human Rights Watch. He said he wore overalls and a coat, but he had no gloves and nothing to cover his nose and mouth.[62]

Some child workers said they did not apply chemicals on tobacco farms, but they helped to mix them, often without any protective equipment. For example, Terrence, a 14-year-old tobacco worker in Mashonaland Central, said, “I will be carrying the water buckets to put in the knapsack where they already have the chemicals. We just pour the water in [to the knapsack], we don’t spray. The smell that comes out once we pour the water in is strong. They [other workers] told me, ‘Don’t open your mouth because the smell will choke you,’” he said. Terrence waited next to the field to refill the knapsack with his bucket while other workers sprayed the fields. “We were waiting outside so when the chemical is finished, then we can pour in the water. We were just standing outside the field while he [an adult worker] was in the field [spraying],” he said. “We would smell it while he was spraying. When we go home, I start to feel dizzy,” he said. “I was feeling nausea, like I want to vomit, but I won’t vomit.”[63]

Other children interviewed for this report described working near areas where other workers were applying chemicals to tobacco fields. “They were fumigating the tobacco leaves, and we were weeding,” said 17-year-old Malcolm, a child tobacco worker in Mashonaland West. “We were feeling dizzy from the smell of the chemical,” he said. “It was in the same field. My face was itching.”[64] Praise, also 17, had a similar experience working on a large commercial farm in Mashonaland West: “There is this chemical called Carrot. If it’s sprayed and it’s windy, the wind carries the smell to my eyes. I feel like my eyes are burning.”[65]

In addition, some children said they were asked to enter fields that had been very recently sprayed with chemicals. Rufaro and Zendaya, both 15, worked together on a tobacco farm in Mashonaland Central. Both girls said they had vomited after entering fields that had just been sprayed. “[It happens] when they spray the chemicals. It’s because of the smell. It’s so bad,” said Zendaya. “Most of the people, they vomit,” added Rufaro. “We were working in fields that had been sprayed. We were picking worms [off of the leaves]. They spray first, and then the worms come out, and then we got [into the field] and get them. Every time they spray, people go home sick [after work].”[66]

Pesticides enter the human body when they are inhaled, ingested, or absorbed through the skin. Pesticides pose serious health risks to the individuals applying them, as well as to other individuals nearby. Research has shown tobacco workers may also suffer chronic exposure through contact with pesticide residues remaining on plants and in soil.[67]

Though Human Rights Watch could not determine the precise toxicity of the chemicals used on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe, pesticide exposure is associated with acute health problems including nausea, dizziness, vomiting, headaches, abdominal pain, and skin and eye problems.[68] Exposure to large doses of pesticides can have severe health effects including loss of consciousness, coma, and death.[69]

Long-term and chronic health effects of pesticide exposure are well documented and include respiratory problems, cancer, depression, neurologic deficits, and reproductive health problems.[70] Children are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of toxic exposures as their brains and bodies are still developing.[71] Many pesticides are highly toxic to the brain and reproductive health system,[72] both of which continue to grow and develop during childhood and adolescence.[73]

While pesticides are applied to many crops on farms around the world, tobacco workers may be at especially high risk for pesticide exposure given the nature of tobacco farming.[74] Tobacco plants are planted very close together and grow to one to three meters in height.[75] Workers often spend extended periods of time with much of their bodies brushing up against pesticide-treated leaves. In addition, directly handling pesticide-treated leaves during topping, suckering, or hand-harvesting increases exposure, particularly in the absence of effective protective gear and handwashing.[76]

Health Problems while Working with Dried Tobacco

Several children reported respiratory symptoms while working with dried tobacco, such as coughing, sneezing, difficulty breathing, or tightness in the chest. Fungai, 16, worked on five tobacco farms in Mashonaland Central, where he lived with his mother and two older siblings. He said he suffered respiratory symptoms while grading dried tobacco: “During grading, you’re sneezing and having trouble breathing. It’s the smell of the tobacco. Once it hits you it’s like you’ve been burned.”[77] Some described these symptoms as “flu,” a term often used in Zimbabwe to describe the symptoms of a common cold: coughing, sneezing, and congestion.[78] Farai, a 14-year-old worker in Mashonaland Central, described how he felt when working around dried tobacco: “You feel like sneezing.”[79]

“During tobacco season, particularly curing time, I always have chest pains and coughing,” said 18-year-old Moses, who started working on his family’s tobacco farm in Mashonaland West at age 16. Moses said his family stored dried tobacco leaves inside their home before selling them. “We normally share our bedroom with cured tobacco, and the air isn’t good. It’s not safe. I also feel dizzy and have headaches.”[80]

Northern Tobacco (NT), the company with the second-largest market share of tobacco purchases in Zimbabwe in 2016, included information on the hazards to children of exposure to dust while working in tobacco farming in its 2017 Grower’s Guide on Child Labour in Tobacco Farming. In a section outlining hazards in agriculture, the document states, “Children who work in tobacco production are exposed to dust when preparing the land, weeding, harvesting, curing, grading and transporting tobacco leaves. Respiratory, skin and eye problems such as allergies and asthma, are common reactions.”[81]

Child Labor and Education

Despite a constitutional requirement to promote “free and compulsory basic education for children,” the Zimbabwean government does not provide a truly free public education to all children. Many families have to pay fees or levies for their children to go to public schools, even at the primary level. Children are only required to attend school through age 12, even though the minimum age to begin working is 16.[82] The Children’s Act prohibits anyone from employing or engaging any school-age children in work during school hours.[83] Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that primary school fees were typically US$10 to $15 per term, and secondary school fees were higher—sometimes close to $150 for the first term, and $35 to $50 for subsequent terms. Nearly everyone interviewed for this report said that school fees posed a barrier to children’s education, and many interviewees said the fees became prohibitively expensive for their families, particularly in secondary school. Though the government has stated that children should not be sent home from school for non-payment of fees, some interviewees said school administrators sent children home, or refused to provide end-of-year exam results if school fees were unpaid.

Human Rights Watch’s findings were consistent with a 2017 study into rural livelihoods by the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC), a consortium of Zimbabwe government agencies, UN agencies, and other organizations. The report found, “The high proportion of children who were turned away from school due to non-payment of school fees is worrisome,” and called for stricter monitoring of the government’s policy that no child should be denied access to school for failing to pay fees.[84]

Interviewees also described how indirect educational costs for things like books and uniforms posed a challenge for many families. Some interviewees told Human Rights Watch that uniforms cost around $15, and books cost from $0.20 to $6 each, depending on the subject and grade level.[85]

It was beyond the scope of this report to investigate barriers in access to primary and secondary education across all sectors, as the focus of our research was child labor and human rights abuses on tobacco farms. In research in other countries, Human Rights Watch has found that school fees pose a barrier to education for many children.[86] In Zimbabwe, the difficulties accessing education because of school fees likely affect many low-income families outside of the tobacco sector. UNICEF reports that even though overall enrollment has increased in Zimbabwe, more than 1.2 million children ages 3 to 16 are out of school.[87] Still, our research suggests children in small-scale tobacco farming families may face particular risks continuing their education, due to the nature of their financial cycles. Small-scale farmers in other types of agricultural production may face similar challenges.

Tobacco Farming Financial Challenges and Education

Many small-scale tobacco farmers told Human Rights Watch that due to the nature of their financial cycles—in which they received earnings only during one part of the year after selling tobacco—they often struggled to pay school fees at the start of the first academic term each year in January. For example, Edward, a 35-year-old contract farmer in Mashonaland Central, explained that he owed $250 to the schools for his four children’s fees for the first term of 2017. “We haven’t sold tobacco yet,” he said. “When I go to the auction floors to sell my tobacco, that’s when I’ll be able to pay.” He said his children were sent home from school nearly half of the time when the fees were unpaid. “For that term, the children don’t learn well because they are constantly being sent home…. It affects their [academic] results. They won’t be in class when others are learning,” he said.[88]

Many tobacco companies recognize that children in tobacco farming families may be at risk of missing school, either to help on the farm or because of difficulty paying school fees.[89] A 2017 assessment by Northern Tobacco in one tobacco-growing region from which it sources in Zimbabwe confirmed high rates of absenteeism due to farmers’ difficulty paying school fees and risks of child labor during the most labor-intensive tobacco farming periods. The assessment found, “Some of small scale growers’ school-going children only attend school during second term after tobacco sales. First term and third term there is high absenteeism due to lack of school fees. Child labor is high in some areas during tobacco peak season which leads to high absenteeism rate among local schools.”[90]

In a letter to Human Rights Watch, Alliance One International described how it allowed growers contracted with its subsidiary, Mashonaland Tobacco Company, to retain a portion of their earnings from tobacco sales prior to paying off their debts to the company, in order to allow growers to pay their hired laborers and to have money for school fees and other educational costs for their children: “This mitigates the risk of child labor and enables the children of both the farmer and his/her labor to attend school,” the company said.[91]

Missing School to Work

Some teachers in tobacco growing regions told Human Rights Watch that their students often missed classes during the tobacco growing season, particularly during the labor-intensive periods of planting and harvesting, making it difficult for them to keep up with their school work.