Summary

Too many times I’m given too many pills…. [Until they wear off], I can’t even talk. I have a thick tongue when they do that. I ask them not to [give me the antipsychotic drugs]. When I say that, they threaten to remove me from the [nursing] home. They get me so I can’t think. I don’t want anything to make me change the person I am.

—Walter L., an 81-year-old man given antipsychotic drugs in a Texas nursing facility, December 2016.

It used to be like a death prison here. We cut our antipsychotics in half in six months. Half our residents were on antipsychotics. Only 10 percent of our residents have a mental illness.

—A director of nursing at a facility in Kansas that succeeded in reducing its rate of antipsychotic drug use, January 2017.

In an average week, nursing facilities in the United States administer antipsychotic drugs to over 179,000 people who do not have diagnoses for which the drugs are approved. The drugs are often given without free and informed consent, which requires a decision based on a discussion of the purpose, risks, benefits, and alternatives to the medical intervention as well as the absence of pressure or coercion in making the decision. Most of these individuals—like most people in nursing homes—have Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia. According to US Government Accountability Office (GAO) analysis, facilities often use the drugs to control common symptoms of the disease.

While these symptoms can be distressing for the people who experience them, their families, and nursing facility staff, evidence from clinical trials of the benefits of treating these symptoms with antipsychotic drugs is weak. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) never approved them for this use and has warned against its use for these symptoms. Studies find that on average, antipsychotic drugs almost double the risk of death in older people with dementia. When the drugs are administered without informed consent, people are not making the choice to take such a risk.

The drugs’ sedative effect, rather than any anticipated medical benefit, too often drives the high prevalence of use in people with dementia. Antipsychotic drugs alter consciousness and can adversely affect an individual’s ability to interact with others. They can also make it easier for understaffed facilities, with direct care workers inadequately trained in dementia care, to manage the people who live there. In many facilities, inadequate staff numbers and training make it nearly impossible to take an individualized, comprehensive approach to care. Many nursing facilities have staffing levels well below what experts consider the minimum needed to provide appropriate care.

Federal regulations require individuals to be fully informed about their treatment and provide the right to refuse treatment. Some state laws require informed consent prior to the administration of antipsychotic drugs to nursing home residents. Yet nursing facilities often fail to obtain consent or even to make any effort to do so. While all medical interventions should follow from informed consent, it is particularly egregious to administer a drug posing such severe risks and little chance of benefit without it.

Such nonconsensual use and use without an appropriate medical indication are inconsistent with human rights norms. The drugs’ use as a chemical restraint—for staff convenience or to discipline or punish a resident—could constitute abuse under domestic law and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment under international law.

The US has domestic and international legal obligations to protect people who live in nursing facilities from the inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs, among other violations of their rights. These obligations are particularly important as people in nursing facilities are often at heightened risk of neglect and abuse. Many individuals in nursing facilities are physically frail, have cognitive disabilities, and are isolated from their communities. Often, they are unable or not permitted to leave the facility alone. Many depend entirely on the institution’s good faith and have no realistic avenues to help or safety when that good faith is violated.

US authorities, in particular the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) within the US Department of Health and Human Services, are failing in their duty to protect some of the nation’s most at-risk older people. On paper, nursing home residents have strong legal protections of their rights, but in practice, enforcement is often lacking. Although the federal government has initiated programs to reduce nursing homes’ use of antipsychotic medications and the prevalence of antipsychotic drug use has decreased in recent years, the ongoing forced and medically inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs continues to violate the rights of vast numbers of residents of nursing facilities. The US government should use its full authority to enforce longstanding laws, including by penalizing noncompliance to a degree sufficient to act as an effective deterrent, to end this practice.

***

This report documents nursing facilities’ inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs in older people as well as the administration of the drugs without informed consent, both of which arise primarily from inadequate enforcement of existing laws and regulations. The report is based on visits by Human Rights Watch researchers to 109 nursing facilities, mostly with above-average rates of antipsychotic medication use, between October 2016 and March 2017 in California, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, New York, and Texas; 323 interviews with people living in nursing facilities, their families, nursing facility staff, long-term care and disability experts, officials, advocacy organizations, long-term care ombudsmen, and others; analysis of publicly available data; and a review of regulatory standards, government reports, and academic studies.

This report is especially relevant at this time because the US is aging rapidly. Most of the people in the nursing facilities Human Rights Watch visited are over the age of 65. Older people now account for one in seven Americans, almost 50 million people. The number of older Americans is expected to double by 2060. The number of Americans with Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, is expected to increase from 5 million today to 15 million in 2050. The system of long-term care services and supports will have to meet the needs—and respect the rights—of this growing population in coming years.

Social Harm and Health Risks Caused by Antipsychotic Drugs Used Unnecessarily or as Chemical Restraints

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline on the Use of Antipsychotics to Treat Agitation or Psychosis in Patients with Dementia states that, after eliminating or addressing underlying medical, physical, social, or environmental factors giving rise to manifestations of distress associated with dementia, antipsychotic drugs “can be appropriate” as a means to “minimize the risk of violence, reduce patient distress, improve the patient’s quality of life, and reduce caregiver burden.” However, given the “at best small” potential benefits and the “consistent evidence that antipsychotics are associated with clinically significant adverse effects, including mortality,” it is essential that the drug treatment is only attempted when appropriate.

Nursing facility staff, individuals living in facilities, their families, long-term care advocates, and others told Human Rights Watch that the drugs are not used only as a last resort, after all factors potentially giving rise to a person’s distress have been ruled out, and after nonpharmacologic interventions have been attempted unsuccessfully. Instead, antipsychotic drugs are used sometimes almost by default for the convenience of the facility, including to control people who are difficult to manage.

One facility social worker said that one of the most common “behaviors” leading to antipsychotic drug prescriptions was someone constantly crying out, “help me, help me, help me.” An 87-year-old woman reflected that at her prior facility, which gave her antipsychotic drugs against her will, “they just wanted you to do things just the way they wanted.” A social worker who used to work in a nursing facility said the underlying issue is that “the nursing homes don’t want behaviors. They want docile.” A state surveyor said: “I see way too many people overmedicated.... [Facilities] see it as a cost-effective way to control behaviors.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed people who live in nursing homes and their family members who described the harmful cognitive, social, and emotional consequences of the medications that all too often should never have been administered in the first place: sedation, cognitive decline, fear, and frustration at not being able to communicate. Most or all antipsychotic drugs are associated with sedation and fatigue in people with dementia.

A 62-year-old woman in a nursing facility in Texas who said she was given Seroquel, a common antipsychotic drug, without her knowledge or consent said: “[It] knocks you out. It’s a powerful, powerful drug. I sleep all the time. I have to ask people what the day is.” The daughter of a 75-year-old woman in Kansas said that when the nursing facility began giving her mother an antipsychotic drug, her mother “would just sit there like this. No personality. Just a zombie.... The fight is gone.”

Nursing staff, social workers, long-term care ombudsmen, and state surveyors echoed this perception. One director of nursing said: “You actually see them decline when they’re on an antipsychotic. I think it’s sadder than watching someone with dementia decline.”

Lack of Informed Consent Prior to Antipsychotic Medication Administration

The use of antipsychotic drugs to control people without their knowledge or against their will in nonemergency situations violates international human rights. The practicalities of obtaining consent from an older person with dementia can be fraught. However, in many of the cases Human Rights Watch documented, nursing facilities made no effort to obtain meaningful, informed consent from the individual or a health proxy before administering the medications in cases where it clearly would have been possible to do so.

Our research suggests that in many other cases, facilities that purport to seek consent fail to provide sufficient information for consent to be informed; pressure individuals to give consent; or fail to have a free and informed consent procedure and documentation system in place. Under international human rights law, in the absence of free and informed consent, a nonemergency medical intervention that is not necessary to address a life-threatening condition is forced treatment.

One former nursing facility administrator explained:

The facility usually gets informed consent like this: they call you up. They say, “X, Y, and Z is happening with your mom. This is going to help her.” Black box warning (the government’s strongest warning to draw attention to serious or life-threatening risks of a prescription drug)? “It’s best just not to read that.” The risks? They gloss over them. They say, “That only happens once in a while, and we’ll look for problems.” We sell it. And, by the way, we already started them on it.

A current director of nursing admitted, “We are supposed to be doing informed consent. It’s on the agenda. But really antipsychotics are a go-to thing. ‘Give ‘em some Risperdal and Seroquel.’ We tell the family as we’re processing the order. The family is notified.” The daughter of a woman in a nursing facility described having consented to antipsychotic drugs for her mother without understanding the risks: “I had no idea, not at all, that the drugs were dangerous. I had no idea.... I’m guessing most people have no idea.”

A detailed examination of the question of legal capacity—the right to exercise one’s own rights and to make decisions on one's own behalf—is outside the scope of this report. Because many people living in nursing facilities have dementia and other progressive conditions that affect their cognitive ability, it is a highly complex question how medical and other decisions concerning their care should be made in a rights-respecting manner. In US nursing facilities, substituted decision-making—where a family member or other third party, whether voluntarily designated in advance or not, makes decisions on an individual’s behalf—is common.

Government Obligations

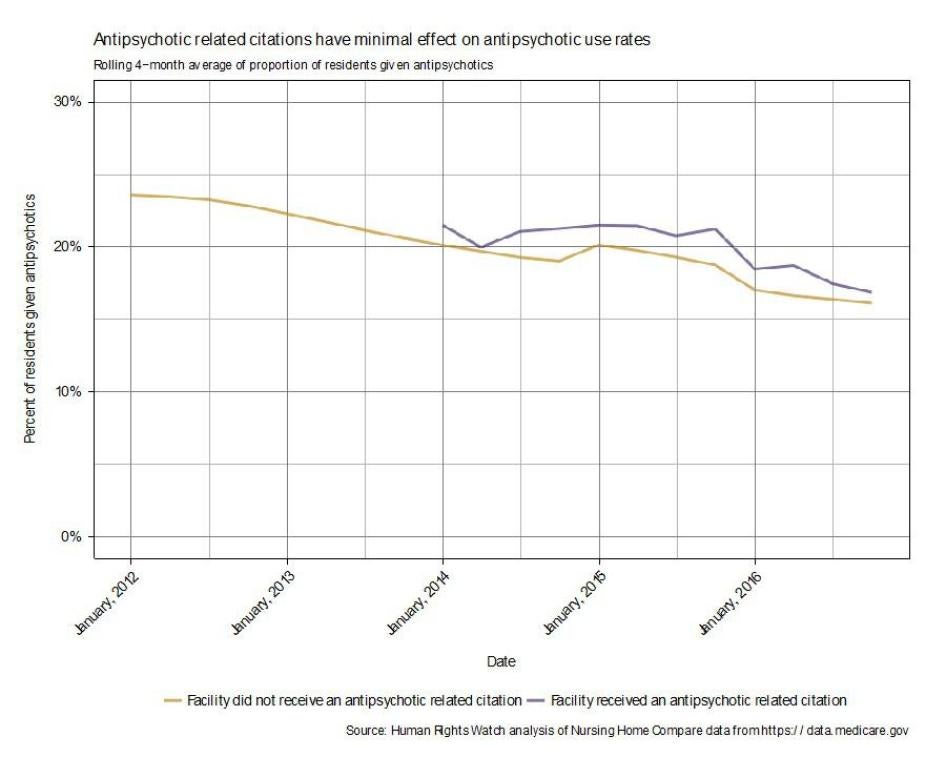

In 2012, CMS created the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes, in recognition of the unacceptably high prevalence of antipsychotic drug use. While the initiative—which set targets for the industry to reduce antipsychotic drug rates—may have contributed to the reduction of the use of antipsychotic medications over the last six years, it cannot substitute for the effective regulation of nursing homes, including by ensuring that facilities face meaningful sanctions for noncompliance with mandatory standards. Our research found that CMS is not using its full authority to address this issue. Recently, CMS is in fact moving in the opposite direction, limiting the severity of financial penalties and the regulatory standards with which facilities must comply.

CMS and the state agencies with which it contracts to enforce federal regulations are not meeting their obligation to protect people from the nonconsensual, inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs. Human Rights Watch identified several key areas of concern:

- Failure to adequately enforce the right to be fully informed and to refuse treatment or to require free and informed consent requirement. The Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987 grants residents the right “to be fully informed in advance about care and treatment,” to participate in care planning, and to refuse treatment without penalty. If it were enforced fully, these protections would not differ substantially from the right to free and informed consent. However, without adequate enforcement, current practice falls far short of this protection.

- Lack of minimum staffing regulations. Adequate numbers of sufficiently competent staff are at the crux of nursing facility care. Yet government regulations do not set a minimum staffing requirement for nursing facilities, instead requiring that facilities determine for themselves what amounts to “sufficient” and “competent” staff for their residents. While experts put minimum adequate nursing staffing time at 4.1 to 4.8 hours per resident per day, most facilities self-reported to the government providing less than that; almost one thousand facilities self-reported providing less than three hours of staff time per day.

- Weak enforcement of federal regulations specifically banning chemical restraints and unnecessary drugs. Federal regulations prohibit chemical restraints—drugs used for the convenience of staff or to discipline residents without a medical purpose—and unnecessary drugs: a technical term meaning drugs used without adequate clinical indication, monitoring, or tapering. The regulations also provide for the right to refuse treatment. However, federal and state enforcement of these regulations is so weak that the drugs are routinely misused without significant penalty. Almost all antipsychotic drug-related deficiency citations in recent years have been determined to be at the level of causing “no actual harm,” curtailing the applicability and severity of financial sanctions.

With such vast numbers of nursing facility residents still getting antipsychotic drugs that many do not need, do not want, and that put their lives and quality of life at risk, federal and state governments need to do more to ensure that the rights of residents are adequately protected. An industry entrusted to provide care—and paid billions of public and private dollars to do so—cannot justify compounding the vulnerabilities, challenges, and loss that people often experience with dementia and institutionalization.

Key Recommendations

Federal and state government agencies should take steps to end the inappropriate and nonconsensual use of antipsychotic medications in nursing facilities. In particular, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and other government agencies should:

- End the inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs in older people with dementia in nursing facilities, including many instances where they are administered without free and informed consent; used as chemical restraints; or where their use qualifies as an “unnecessary drug.” CMS and state agencies should use the regulatory and enforcement tools at their disposable to ensure that routine violations of regulations that help to safeguard individuals’ human rights cease.

- Require nursing facilities and residents’ physicians to seek free and informed consent prior to the administration of antipsychotic medications to nursing facility residents. Federal regulations providing for the right to be fully informed and to refuse treatment—as well as state laws that provide for informed consent—should be enforced more effectively. The establishment in the federal regulations of a right to informed consent may improve protection in practice by clarifying the right’s content and underscoring its significance. Congress and CMS should require that consent be documented and revisited as appropriate.

- Ensure nurse staffing numbers and training levels are adequate. CMS should establish minimum nurse staffing levels for facilities or undertake other effective measures to address understaffing, inadequate training, and high turnover rates in many nursing facilities. Implementation of the payroll-based staffing data collection system, as required by the Affordable Care Act, should be completed, particularly with regard to nursing staff who provide direct resident care. This includes public reporting of staff-to-resident hours of care per day and turnover and retention rates in each nursing home certified by Medicare and Medicaid.

- Strengthen enforcement on particular subjects linked to the inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs, including care planning requirements and transfer and discharge rights. CMS should improve inspection and penalty guidance and enforcement practices related to antipsychotic drugs. Surveyors should follow CMS guidance indicating that many inappropriate uses of antipsychotic drugs amount to Level 3 or 4—actual harm and immediate jeopardy—severity of violations.

Methodology

This report focuses on the inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs among older people, primarily with dementia, in nursing facilities across the US. Many older people who live in nursing facilities or reside there temporarily are at risk of suffering from this abuse. They rely on the government’s enforcement of federal regulations to protect their rights, including to be free from unnecessary drugs, drug treatment to which they object, and sedating drugs administered for the convenience of facility staff. Human Rights Watch found that enforcement is inadequate to deter the misuse of antipsychotic drugs.

This topic was chosen because of the paradox that misuse of the drugs has been well-documented for decades, prohibited by law, and yet persists as a pervasive, serious problem. The amount of publicly available data on nursing homes and antipsychotic drugs specifically made it feasible to conduct the research. The project was also chosen to attempt to amplify the voice and highlight the circumstances of some of the most isolated individuals: not only by living in nursing homes or having dementia, but also by being under the influence of the psychotropic medication.

The report is based on interviews with 323 people in New York, Texas, Kansas, Illinois, California, and Florida between October 2016 and March 2017. Additional interviews were conducted over the phone from September 2016 to April 2017. In addition, Human Rights Watch consulted secondary sources, conducted significant background research, and analyzed copious amounts of data.

These six states were selected for multiple reasons. California and Texas have the highest number of nursing facilities, with 1,219 and 1,212 respectively in 2014. California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas have among the highest numbers of nursing facility residents of any state. Excluding facilities where less than half of the residents are over age 65, Texas and New York lead all states in terms of the number of nursing home residents taking antipsychotic drugs without an exclusionary diagnosis of schizophrenia, Huntington’s disease, or Tourette syndrome. Kansas, Texas, and Illinois have some of the highest proportions of residents on antipsychotic drugs. More detailed data on these states and their rankings nationally can be found in Appendix 3. Most of these states were also chosen based on their strong citizen advocacy organizations working on nursing facility reform and resident rights protection and their long-term care ombudsman programs.

In the six states, Human Rights Watch interviewed 74 people between the ages of 37 and 93 who live in nursing facilities, including 15 under the age of 65. All of the individuals in nursing facilities had cognitive, psychosocial, and/or physical disabilities. Almost all of the individuals were in facilities with high rates of antipsychotic drug use; in many cases, they or someone who knows them told Human Rights Watch that they currently or previously took antipsychotic drugs. However, not all interviewees claimed to take antipsychotic drugs, and it was not possible to view the medical records of the majority of interviewees.

We interviewed 36 family members of residents, 20 long-term care ombudsmen, 18 advocates including attorneys, 10 state and federal government officials, 90 facility administrators, nursing, and social services staff, and six medical professionals such as pharmacists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and doctors. We have omitted people’s names or used pseudonyms where names or other identifying information may compromise the privacy of individuals or invite possible reprisals.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 69 experts, including lawyers, academic researchers, professors, journalists, doctors (in addition to those interviewed associated with nursing facilities or nursing facility residents mentioned above), government officials, and advocates. Human Rights Watch sent letters to CMS, the American Health Care Association (AHCA), and LeadingAge—the government agency that oversees the nursing facility industry, the for-profit trade association, and the nonprofit trade association, respectively—with questions regarding this report’s findings. We received responses from AHCA and LeadingAge (see Appendices 6 and 7). We did not receive a response from CMS at time of writing.

Human Rights Watch visited 109 facilities. In 17 of the 109 facilities, we were not allowed to conduct research. Of the remaining 92, sometimes our entry was with explicit permission of the facility, sometimes with permission of the person we were visiting, and sometimes without permission of the facility but without objection. In some cases, we talked to staff only and not residents.

Two of the 109 facilities were in New York, 25 in Texas, 20 in Kansas, 16 in Illinois, 23 in California, and 23 in Florida. One of the 109 has since closed. All facilities were skilled nursing facilities or nursing facilities rather than assisted living facilities, and all received some combination of payment through Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, and private pay. The US Department of Veterans Affairs operates community living centers, nursing homes, and state veterans’ homes across the country as well, as part of the Veterans Health Administration; they are regulated differently and outside the scope of this project. Facilities were selected based on publicly available data on the average percentage of residents without an exclusionary diagnosis given at least one antipsychotic medication in the last quarter.

We primarily visited facilities with a majority population over the age of 65. As of 2010, 16 percent of the nation’s nursing home population was between the ages of 31 and 64. Younger people live in nursing facilities for a variety of reasons. However, nursing homes with majorities of younger people and high rates of antipsychotic drug use tend to have greater concentrations of people with psychosocial disabilities. While the administration of antipsychotic drugs may be inappropriate despite psychiatric diagnoses for which the drugs are approved, the root of the rights violations may be distinct, and this report was limited to the demographic of older people, often with dementia.

Of the 109 facilities visited, 79 facilities (72 percent) were for-profit and corporate owned; five (5 percent) were for-profit and individually owned; five (5 percent) were for-profit and part of a partnership government hospital district; 16 facilities (15 percent) were nonprofit and corporate owned; and one facility (1 percent) was nonprofit and church related.

Researchers were refused admission or asked to leave shortly after arriving in 24 facilities. In some cases, administrators had notice of our interest in visiting and refused to meet or allow us to speak with residents who might wish to speak with us. In other cases, facilities did not have notice and requested that we return at another time.

Whenever possible, Human Rights Watch spoke directly with people who live in nursing facilities. In some cases, nursing facility administrators, directors of nursing, directors of social services, or business or admissions officers refused our request to speak with residents. Some facilities claimed that no resident was their own “responsible party” and that they thus could not consent to an interview.

Where access to residents was not blocked, Human Rights Watch sought to interview residents and staff in private so that they could speak openly without fear of potential retaliation. In some facilities, finding locations that afforded sufficient privacy was difficult. As a result, in some cases, with the interviewee’s permission, we conducted interviews in rooms where the interviewee’s roommate was asleep or watching television. In other cases, we conducted interviews in an activity room or at the end of a hallway that was out of ear shot of other people, but not fully secluded.

Human Rights Watch asked interviewees questions on a wide range of issues, including use of antipsychotic medicines; quality of care; quality of life; demographics of the facility residents; access to health care and rehabilitative services; respect for free and informed consent; autonomy; privacy; visitation; and discharge rights.

Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish. Human Rights Watch obtained the consent of each interviewee; explained the aim of the research; how information collected would be used; and informed them that they could discontinue the interview at any time and could decline to answer questions without consequence. Human Rights Watch provided no personal service or benefit and informed interviewees that their participation was voluntary and confidential.

Finding and interviewing people on antipsychotic drugs is difficult for a number of reasons. First, many are unaware because they were never informed, or are unable to recall, that they are on these medications. Facility staff sometimes do not inform the individuals concerned—or their relatives, the legal representative in some cases—that they are being given antipsychotic drugs.

Second, the effect of the medications can make it difficult to respond to interview questions, and the drugs often make people drowsy.

Third, most people in nursing homes have dementia or other cognitive disability. Additionally, most people given antipsychotic drugs without an “exclusionary diagnosis”—schizophrenia, Huntington’s disease, or Tourette syndrome, the most clear-cut and common conditions for which antipsychotic drugs are approved—have dementia, which affects memory and the ability to express oneself understandably.

Fourth, privacy concerns make determining who is receiving the medications difficult.

Fifth, nursing facility staff often do not consider residents to be their own “responsible party”—a term of art frequently used in an overly broad manner to indicate who can exercise a person’s rights. In many cases, facility staff decided on behalf of all residents that Human Rights Watch could not interact with them, often justifying that decision by invoking the need to protect residents.

Informed consent and legal capacity—the right to exercise one’s rights and to make decisions—are critical human rights linked inextricably with the question of appropriate antipsychotic drug use. The administration of psychoactive medication may violate a person’s rights if it is not administered with informed consent. Legal capacity controls whose consent is necessary and valid. However, a comprehensive analysis of consent and legal capacity is beyond the scope of this report. The report focuses on violations of the right to informed consent in cases where it was clearly possible for the facility to seek it, either because a person lacked any severe cognitive disability or because the person had voluntarily designated a proxy to act on their behalf.

Because of significant practical challenges, the residents interviewed do not reflect the most isolated and at-risk people in nursing facilities: people who are on their own, without family or friend visiting or communicating with the facility staff, and who have significant cognitive disabilities that impair their ability to communicate or advocate on their own behalf. Compounding the aforementioned challenges in interviewing residents, for these “unbefriended” or “unrepresented” individuals, there is the additional barrier of not having any intermediary person to identify and connect Human Rights Watch researchers to the person living in the nursing facility.

It is these individuals with severe cognitive disabilities and without someone to assist their communication or decision-making whose rights to legal capacity and informed consent are at the greatest risk of violation. However, they are also the individuals whom it is hardest to access to inquire about an interview and hardest to interview. As a result, the rights violations documented in this report reflect those experienced by people in nursing homes either able to more easily communicate with Human Rights Watch researchers or those experienced by people with family or friends involved in their care.

This report does not analyze nonconsensual use of antipsychotics in nursing facilities on persons who have a diagnosis for which antipsychotics have been approved. Rather, it focuses on the use of these drugs on people with dementia. This report also does not address the process in which people are placed in nursing homes. These issues are complex and go beyond the scope of this report.

Human Rights Watch relied upon several data sets for the quantitative analysis involved in this report, including one provided by Nursing Home Compare. This website, maintained by CMS, provides facility- and state-level data based on the Minimum Data Set (MDS), a federally mandated national database of periodic, individual, clinical, comprehensive assessments of all residents in Medicare and Medicaid certified nursing homes. Nursing facilities submit electronically the MDS information. Nursing Home Compare includes other self-reported and governmental surveyor-reported data for all facilities in the country certified to receive payment from Medicare and Medicaid, which is almost all facilities nationwide.

Despite the volume of publicly available data on the use of antipsychotic drugs in nursing facilities, a number of significant challenges arose in conducting quantitative analyses. First, it is not possible to determine from a single publicly available data set the proportion of all individuals with dementia in nursing facilities without a psychiatric or neurological diagnosis for which an antipsychotic drug is clinically indicated that takes antipsychotic medication. Second, a significant amount of the data on nursing homes is self-reported by those facilities, some of which could be inaccurate and as such may influence the results of statistical tests that Human Rights Watch ran.

Nonetheless, through quantitative data analysis, Human Rights Watch was able to estimate the total numbers of people who receive antipsychotic drugs, live in nursing facilities with a majority population over the age of 65, and do not have an exclusionary diagnosis. (Age 65 is a rough cut-off point to exclude people who are younger and given antipsychotic drugs, appropriately or not, since this research was focused on older people.) We also analyzed antipsychotic drug-related deficiency citations, which are federal and state government inspectors’ findings of facilities’ noncompliance with the federal regulations that establish minimum health and safety standards for the industry. A detailed description of the methodology used can be found in Appendix 4.

I. Background

Long-Term Care in the US

The population of the US is growing older. Between 2005 and 2015, the country’s population aged 65 and over increased by 30 percent. Older people now account for one in seven Americans: almost 50 million people, over 26 million women and over 21 million men.[1] By 2060, the number of older Americans (age 65 and older) is expected to double to almost 100 million, or one in four Americans.[2] The population aged 85 and over is growing particularly rapidly and is expected to triple by 2050.[3] The US population will include so many older people in the coming decades because of the baby boom generation is aging while fertility rates continue to decline and life expectancy rates have increased.[4]

As the older population increases, more people will experience age-related disabilities, and dementia in particular.[5] Today, over 5 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia, involving the loss of cognitive abilities, memory, and language.[6] By 2050, as many as 16 million Americans could have Alzheimer’s disease; currently, one person in the United States develops the condition almost every minute of every day.[7]

With the growth in older populations and the increases in debilitating conditions such as dementia, the need for long-term care and support services will grow rapidly. Although some forms of dementia have earlier onset, the disease is associated with older age: increasing age is the “greatest known risk factor” for Alzheimer’s disease.[8] Experts estimate that approximately 70 percent of people aged 65 and over will require long-term services and support, ranging from limited support in their own homes and communities to around-the-clock care in institutional settings.[9]

In the US, older people receive long-term care in a variety of settings: at home, in institutional facilities, and in in-between settings like retirement communities, senior housing, assisted living facilities, and board and care homes. Skilled nursing facilities (which provides short-term rehabilitation) and nursing facilities (for long-term care) provide certified and regulated services to people with significant healthcare and assistance needs.

Of the 6 million older people receiving long-term care, about 4 million receive care from a home health agency at home.[10] About 1.2 million people aged 65 and over lived in 15,600 nursing facilities in 2014, and almost 780,000 people lived in other residential care communities.[11] The proportion of people living in institutional settings increases with age because care needs become more intensive.[12]

Other institutional care settings like assisted living are non-medical and provide minimal supervision. Medicare and Medicaid do not pay for assisted living in most cases.[13] Medicare is the primary provider of health insurance to people aged 65 and older in the United States. It includes four parts: Parts A, B, C, and D, covering hospital insurance (including the first 100, rehabilitative days in a skilled nursing facility); medical insurance (such as doctors, outpatient care, medical equipment, and preventive services); private companies’ health plans (Medicare Advantage); and prescription drugs (including long-stay nursing facility residents’ drug prescriptions), respectively.[14]

Medicaid, which is the primary public health insurance program for people with low income in the US and is jointly administered by the federal government and the states, is the primary payer for long-term care, accounting for 51 percent of the nursing home industry’s expenditures.[15] Consequently, to receive institutional long-term care outside of a nursing facility requires significant private resources, estimated at over US$3,000 per month.[16]

The total cost of long-term care varies by context. In 2015, the median annual cost of living in a nursing facility was over $90,000, roughly twice the cost of having a home health aide and five times the cost of an adult day health care program (almost $18,000).[17] Long-term care costs vary significantly by state. For example, a semi-private skilled nursing home room in the most expensive states (Alaska, Connecticut, and Massachusetts) costs almost three times as much as in the least expensive states (Texas, Missouri, and Louisiana), $143,000–$168,000 compared to $56,000–$61,000 annually. Moreover, home health aides in the most expensive states (Massachusetts, Alaska, and New Jersey) cost almost twice as much as in the least expensive states (Alabama, Louisiana, and West Virginia), $28–$31 versus $17–$19 hourly.[18] In 2013, approximately half of Medicare beneficiaries, which include older people and younger people with disabilities, earned less than $23,500 per year.[19]

Despite the common perception that Medicare is for older people and Medicaid is for the poor, many people in the middle class in nursing facilities depend on Medicaid. Many people who saved for assisted living or other non-nursing facility care spend down their savings rapidly. In 2012, paying privately for the median cost of a nursing home ($81,030) would cost 252 percent of the median household income ($34,381) for people aged 65 and up.[20] One in three people turning 65 may require care from a nursing facility at some point in their life, and three-quarters of long-term nursing facility residents will be covered by Medicaid at some point.[21]

The US Nursing Facility Industry

Seventy percent of nursing facilities in the US—about 11,000—are owned by for-profit companies, and almost 25 percent are nonprofit.[22] About 6 percent are publicly owned, most of which (46 percent) are owned by counties, followed by hospital districts (21 percent), states (14 percent), city-county (9 percent), city (8 percent), and the federal government (1 percent).[23] In 2014, almost three in five nursing facilities were part of a chain, meaning they were owned by an entity that owns multiple facilities.[24] Private equity firms own about 12 percent of all nursing facilities (18 percent of for-profit ones).[25] Ten chains own the facilities in which 14 percent of the nation’s residents live, the largest concentration.[26]

In 2015, the nursing facility industry, assisted living, and other types of long-term care recorded annual revenues of $156.8 billion, 41 percent of which came from Medicaid and 21 percent from Medicare.[27] Medicare and Medicaid have provided the financial foundation of the nursing facility industry since their creation.[28]

The federal government regulates the nursing facility industry through the Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987, requiring facilities to meet certain standards to be certified and paid by Medicare and Medicaid.[29] CMS contracts with state agencies to certify facilities and to ensure “substantial compliance” with minimum health and safety requirements.[30]

In subsequent sections, this report describes the inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs in older people with dementia in US nursing facilities—including use without valid medical reason; for the convenience of staff; inconsistent with federal regulatory requirements; and without informed consent. The report discusses the inadequacy of federal regulations, enforcement, and access to private remedies for harm.

This background section describing the long-term care system provides the context to understand—and highlights the salience of—facilities’ abuses and governmental shortcomings. The population is aging, and long-term care services and supports, including nursing homes, are more likely to be necessary as age-related disabilities rise. It is not only the poor who end up in nursing facilities but many people in the middle class: people who never had and never anticipated relying on Medicaid. Dementia—a risk factor for being given antipsychotic drugs in nursing homes inappropriately, until the government enforces protections against such abuse more effectively—affects people across income, gender, and race.

The industry’s reliance on Medicare and Medicaid described in this section, as well as the breakdown in the industry by ownership status, with the prevalence of chain ownership, relate to regulatory and enforcement concerns. As noted, facilities are required to comply with certain standards of care to receive certification and payment from Medicare and Medicaid: these health insurance programs are the government’s basis for regulating facilities.

II. The Risks and Harms of Antipsychotic Medications on People with Dementia in Nursing Facilities

I would just shut off and not say anything. [It] was a very traumatic time.

—Madeline C., an 86-year-old woman at a nursing facility in Illinois describing being on antipsychotic medications, February 2017.[31]

Antipsychotic drugs were originally developed to treat schizophrenia. The first generation—so-called “conventional” antipsychotics, such as Haldol (haloperidol)—was developed in the 1950s, and a second generation—called “atypical” antipsychotics, such as Seroquel (quetiapine)—was developed in the 1980s.[32] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved some of these medicines for treatment of other conditions since then, such as Tourette syndrome and bipolar disorder.[33] The FDA has not approved antipsychotic drugs for treating symptoms of dementia.

Antipsychotic medications are one of several classes of psychotropic drugs affecting the central nervous system. Psychotropic drugs include anti-anxiety medications, anti-depressants, hypnotics, anxiolytics and sedatives like benzodiazepines (e.g., Xanax, Ativan, Valium, Klonopin), anticonvulsants, and mood stabilizers (e.g., Depakote or lithium, often used for bipolar disorder), some of which have comparable effects to antipsychotic drugs and all of which are used prevalently in nursing facilities.[34] (CMS has expressed concern that, as the use of antipsychotic drugs in people with dementia is discouraged as inappropriate, these other classes of medications should not replace them.[35]) Other types of psychotropic drugs, such as anti-anxiety drugs, can have similar sedating properties and cause adverse effects if used inappropriately. In revising federal regulations in 2016, CMS wrote:

Expanding the requirements for antipsychotic drugs to psychotropic drugs will expand protections for residents prescribed drugs that have an increased potential for being prescribed inappropriately or for reasons other than the resident’s benefit, such as for the purpose of a chemical restraint.[36]

Antipsychotic medicines are widely used off-label, that is, for indications or purposes for which the FDA has not approved them. Off-label use of medication is both common and legal. However, the problem with the use of antipsychotic drug in older people with dementia is beyond the issue of legality. As the FDA states in the boxed warning manufacturers must include on conventional and atypical antipsychotic drug labels, elderly patients with “dementia-related psychosis” treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death.[37] It is uncommon for the FDA to require a boxed warning regarding a never-approved use of a drug. Neither off-label use nor the use warned against in boxed warnings affects Medicare coverage of the drug.[38]

The boxed warning on antipsychotic drugs for use in older people with dementia is based on findings that the drugs increase the risk of death in older people with dementia.[39]

Quetiapine Fumarate (SEROQUEL XR®) Extended-release tablets 200mg*, once daily WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death compared to placebo. Analyses of seventeen placebo-controlled trials . . . in these patients revealed a risk of death in the drug-treated patients of between 1.6 and 1.7 times that seen in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group. Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature. [This drug] is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].[40] |

|

A Mock-Up of the Boxed Warning on Antipsychotic Drugs. |

Aside from raising the risk of death, the drugs’ side effects include severe nervous system problems; neuroleptic malignant syndrome (a life-threatening reaction associated with severe muscular rigidity, fever, and altered mental status); tardive dyskinesia (characterized by stiff, jerking movements that may be permanent once they start and whose likelihood of onset increases the longer antipsychotic drugs are taken); high blood sugar and diabetes; and low blood pressure, which causes dizziness and fainting.[41] Other side effects include increased mortality, cerebrovascular events (stroke), cardiovascular effects, blood clots, central and autonomic nervous system problems, visual disturbances, metabolic effects, extrapyramidal symptoms, fall risk and hip fracture, irreversible cognitive decompensation, and pneumonia.[42]

In the context of nursing facilities, the most common use of these medications is in older people with dementia for the “behavioral and psychological symptoms of the disease.”[43] A 2012 Office of Inspector General investigation found that Medicare processed 1.4 million claims for atypical antipsychotic drugs from nursing facilities in 2007. Older people with dementia accounted for 88 percent of the 1.4 million claims.[44] Only 4.7 percent of these claims were for medications that were not used in older people with dementia and were not used for an off-label use. In other words, they were used for someone with schizophrenia or another psychiatric or neurological condition for which the drugs are approved.[45]

The medical reason for prescribing antipsychotic drugs to people with dementia, usually as a last resort, is that dementia is often accompanied by irritability, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, wandering, disinhibition, anxiety, and depression—what some medical professionals call “behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.”[46]

Some studies find that a majority of people with dementia will develop at least one of these symptoms and that individuals in nursing facilities tend to have more severe symptoms than people in other care settings.[47] These symptoms can be distressing and dangerous to the individuals experiencing them and to those around them, including family and caregivers.[48] Nursing facility staff that administer antipsychotic drugs to older people inappropriately but who are not administering them intentionally for staff convenience often appear to believe that the drugs are the best or only treatment option for someone seemingly in distress.

Dementia-related symptoms may result from “underlying neurochemical changes,” changes in the body’s nervous system, associated with dementia or from an external or underlying situation such as pain or personal needs.[49] Pain is often underreported in people with dementia.[50] Unlike schizophrenia and other psychiatric conditions, the “behaviors” of people with dementia often arise from feelings of loneliness, boredom, depression, anxiety, sun-downing (increased agitation or distress in early evening), apathy, distrust of new caregivers, hunger, dehydration, impairment of the brain’s executive function, grief, noise stress, and delirium.[51]

In addition to unmet physical needs, symptoms may be a “response to environmental triggers,” such as being ignored unless a person screams (which inadvertently reinforces the “behavior” of screaming); alternatively, symptoms may be “consequences of a mismatch between the environment and patients’ abilities to process and act upon cues, expectations and demands.”[52] An example of such a distressing mismatch is “resisting care” when expected to be showered if it frightens a person by association with a prior fall. In its revised guidance that intended to go into effect in November 2017, CMS states:

Behavioral or psychological expressions are occasionally related to the brain disease in dementia; however, they may also be caused or exacerbated by environmental triggers. Such expressions or indications of distress often represent a person’s attempt to communicate an unmet need, discomfort, or thoughts that they can no longer articulate.[53]

Experts agree on the importance of attempting nonpharmacologic interventions with individuals with dementia-related symptoms; federal regulations also require such interventions unless clinically contraindicated (when the intervention should not be used due to adverse effects).[54] These interventions follow these steps: evaluating and understanding the origin of the “behavior”; ruling out underlying physical illness, infection, or needs; addressing any underlying dementia-related or environmental issue; and re-evaluating the care plan based on its effectiveness.[55]

Examples of nonpharmacologic interventions include:

- Reducing boredom, pain, loneliness, and similar experiences by changing a person’s activities, surroundings, opportunities, and access to relationships;

- Creating individualized sleep, hygiene, bathroom, and other daily routines that the person prefers;

- Ensuring staff are consistent and familiar to the individual;

- Physical and cognitive exercises; and

- Many types of therapy (music, aroma, reminiscence, behavioral, pet, light, etc.).[56]

Fundamentally, many of these interventions are ways of making an institutional environment conform to an individual’s needs; it is the converse that can give rise to distress, discomfort, and disorientation. Older people and people with dementia should be included and consulted on non-pharmacologic alternatives and other matters that affect their lives and well-being. Including residents shows that their opinions and perspectives about their own care are respected and valued. Even when people with cognitive disabilities have difficulties expressing themselves verbally, they can often indicate some preferences otherwise.

Some medical experts believe and CMS endorses that if it is not possible to address underlying medical, physical, social, or environmental factors in some people, an antipsychotic drug “can minimize the risk of violence, reduce patient distress, improve the patient’s quality of life, and reduce caregiver burden.”[57] The evidence of the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic intervention is mixed.[58] According to the American Psychiatric Association, which issued practice guidelines on the use of antipsychotic drugs in people with dementia, the “expert consensus suggests that use of an antipsychotic medication in individuals with dementia can be appropriate.”[59]

Yet the guidelines conclude, “in clinical trials, the benefits of antipsychotic medications are at best small.”[60] Meanwhile, countering these meager potential benefits is the “consistent evidence that antipsychotics are associated with clinically significant adverse effects, including mortality.”[61] The risks vary depending on the type and stage of dementia, other conditions the person has; other drugs the person takes; the dosing and duration of the antipsychotic drug; and the particular antipsychotic drug.[62]

Similarly, CMS has warned against inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs, given the risks that are unwarranted when the drugs do not serve a medical purpose:

It has been a common practice to use various types of psychopharmacological medications in nursing homes to try to address behavioral or psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) without first determining whether there is an underlying medical, physical, functional, psychosocial, emotional, psychiatric, or environmental cause of the behaviors…. When antipsychotic medications are used without an adequate rationale, or for the sole purpose of limiting or controlling behavior of an unidentified cause, there is little chance that they will be effective, and they commonly cause complications.[63]

Human Rights Watch uses the term “inappropriate” to describe use of the drug in older people with dementia that is: inconsistent with recommendations of medical experts and authorities, such as the American Psychiatric Association and FDA; inconsistent with federal regulations governing nursing homes, which overlap significantly with medical experts’ recommendations; and administered without free and informed consent except in cases of emergency. Concretely, “inappropriate use” in people with dementia often entails use that is not a last resort, use excessive in dose or duration, use without appropriate monitoring of side effects, or use not based on an informed choice about treatment options.

Massive Use of Antipsychotic Medications

It is essential that antipsychotic drugs be used cautiously in people with dementia, only where medically appropriate, and only with informed consent because of the propensity for nursing facilities to use the drugs for non-medical purposes and because of the high risk and low likelihood of benefit even when used for medical reasons. However, Human Rights Watch’s analysis of data on the prevalence of use in people without “exclusionary diagnoses” and interviews with this category of people strongly suggest that such limited use is not what occurs in practice.

Nursing facilities in the US use antipsychotic medications on a massive scale. Every week, facilities administer antipsychotic drugs to over 179,000 long-stay residents (residing in the facility for more than 100 days) who do not have an exclusionary diagnosis—of schizophrenia, Huntington’s disease, or Tourette syndrome, psychiatric and neurological diseases for which the drugs are approved—and most of whom have dementia.[64] At the end of 2016, CMS’s official measure was that 16 percent of long-stay nursing home residents were receiving an antipsychotic medication without one of these three exclusionary diagnoses.[65]

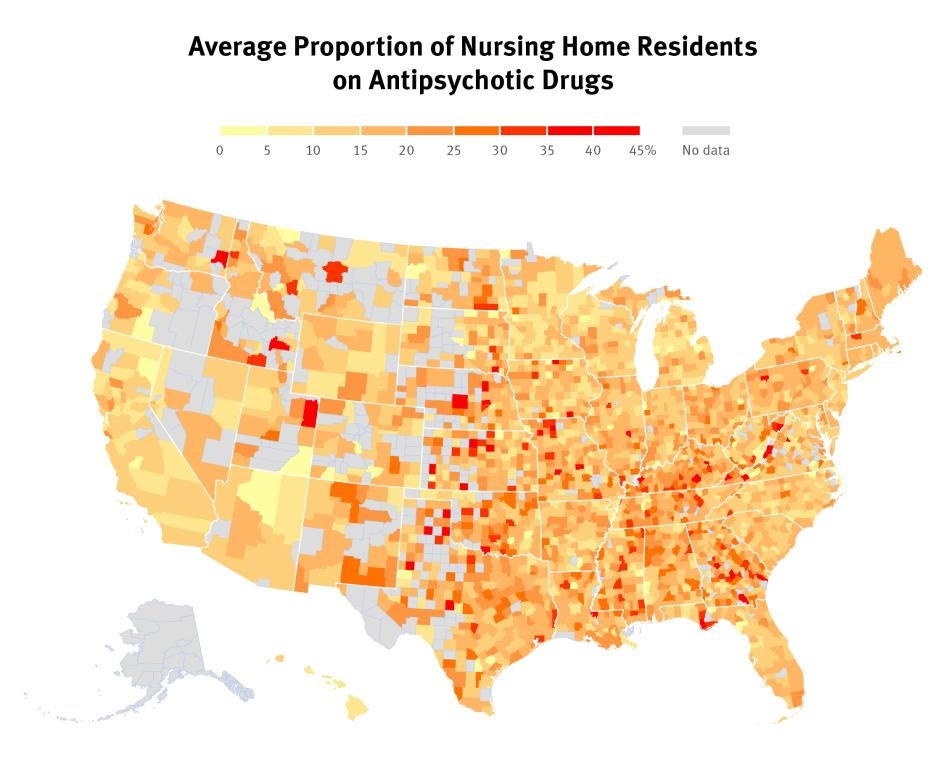

While the national average rate of use of antipsychotic medications among older people in nursing facilities without an appropriate diagnosis has declined in recent years, current prescription rates vary significantly across the country (see Map 1).

Antipsychotic medications not only have adverse medical consequences, but also have social and emotional effects on nursing facility residents and their families. To capture these consequences of forced and inappropriate antipsychotic drug administration, Human Rights Watch interviewed people living in nursing facilities who had dementia and were currently on antipsychotic medications or had been on them previously, as well as their family members. We spoke with 74 residents and 36 family members in all six states. Residents described the trauma of losing their ability to communicate, to think, and to remain awake. Family described the pain of witnessing these losses in a loved one.

Of course, dementia itself causes significant losses, affecting cognition, communication, memory, and other functions. It is impossible without a comprehensive medical evaluation, if then, to determine the direct cause of any individual changes in residents described here. However, most or all antipsychotic drugs in people with dementia are associated with sedation and fatigue.[66] (The type, dose, duration, drug-drug interaction, and other characteristics of antipsychotic drug treatment, as well as a person’s health condition aside from dementia, influence the effects the medications have.[67]) Family members described cognitive and energetic improvements once antipsychotic drugs were stopped—even if the underlying dementia persisted.

Many of the following cases illustrate the psychosocial harm associated with sedation.[68] While they are not testimonies from medical experts who could authoritatively conclude that the antipsychotic drugs caused the sedation described, these descriptions by residents and family members are representative of what antipsychotic drugs in older people with dementia often induce.[69] Moreover, in each of the following cases (except one where the individual took the drugs until she was receiving hospice care and died), the sedative effect ceased when they stopped taking antipsychotic drugs.

Ruth D., a 62-year-old woman who said she was given Seroquel (an antipsychotic medication) without her knowledge or consent in a nursing facility in Texas said: “[It] knocks you out. It’s a powerful, powerful drug. I sleep all the time. I have to ask people what the day is.”[70] The woman described being given the medication against her will, including in her food: “They crush it so you don’t know what you’re getting fed.” When asked to take Seroquel, she would tell nursing staff that she did not want to take it, and that she did not want to eat the food if she suspected the drug was in it. Ms. D continued to object as well as she could to being administered antipsychotic drugs until her discharge from the nursing facility the day after Human Rights Watch interviewed her.

Walter L., an 81-year-old man told Human Rights Watch that antipsychotic medicines “get me so I can’t think.”[71] According to his wife, Anna L., who is his healthcare proxy, he was given them without his or her knowledge or consent. Mr. L told Human Rights Watch that he never again wanted to take something that made him “change the person that I am.” Ms. L. described that when her husband was on the medications he was just “staring straight ahead,” not knowing she was even there. “I leaned him up against the wall, I came back three hours later, and he had not moved,” she said.[72] Ms. L. learned of the drug after a nurse privately alerted her. After changing facilities, the antipsychotic drug was discontinued.

Madeline C., an 87-year-old woman in a facility in Illinois, described the effect of antipsychotic medications administered in a prior nursing facility. She had been placed in a dementia unit. The woman said that when she “just about went crazy” from being in a locked unit with no activities, she “started speaking out, saying things were not right.” After that, she said, “suddenly I was very sleepy,” adding, “you feel like you’re going to die there.” She said she later learned that the facility had given her an antipsychotic drug. At the time of the interview, the woman was in a different facility that had discontinued the drug. “The fog lifted.... There’s the old Madeline again.”[73] Being at the prior facility was “a very traumatic time.”[74]

Alma G., the sister and power of attorney of Mariela O., an 84-year-old woman with dementia who died in 2017, said that her sister’s nursing facility gave her an antipsychotic drug to ease the burden of bathing her.[75] She said, “They give my sister medication to sedate her on the days of her shower: Monday, Wednesday, Friday—an antipsychotic. They give her so much she sleeps through the lunch hour and supper.”[76]

Kirsten D., the daughter and power of attorney of Joan D., a 75-year-old woman in Kansas, said that when the nursing facility began giving her mother antipsychotic and other psychotropic medications, “she would be asleep when I visited. She slept a lot. They’d say she’s adjusting to the meds. I went back weeks later. She would just sit there like this.”[77]

Joan D. said that she tried to avoid taking the antipsychotic drugs—including by hiding them in her dinner roll—because of their effect on her. “I didn’t want to take it so I didn’t. I didn’t want to feel that way.”[78] She explained further that “I try not to take it. Sometimes I have to.”

Kirsten D. described her mother on the antipsychotic medication as “no personality. Just a zombie…. The fight is gone. It’s gone. That’s what worries me the most.... I think she’s learned to keep it contained. She was vibrant, full of life.... She’s still in there.”[79] After significant effort to find another facility with an opening that would accept her mother, Ms. D. moved her mother to another nursing home that ceased the medication. Ms. D said that her mother became lively, talkative, friendly, and mobile again without the medication.

In New York, Dorothy R., the daughter and power of attorney of a woman in a nursing facility, told Human Rights Watch that a nurse informed her that the sudden decline in her mother’s health and cognition was due to her mother “getting older.” After an advocate’s lecture on antipsychotic drugs alerted her to the impact of antipsychotic drugs, Ms. R. requested a list of all the medications her mother was taking. She succeeded in having the facility discontinue the administration of an antipsychotic drug after discovering that the facility had put her on one without her or her mother’s knowledge or consent.[80]

In several cases, we documented how people with dementia seemed to improve dramatically once the antipsychotic drugs were discontinued. Laura F., the daughter of a resident in California, initially saw her mother’s decline as an irreversible, progressive result of her age: “You know, she’s 90. Yesterday, she’s alert. Now she’s not. That’s what happens.”[81] But when the nursing facility took her mother, Selina C., off Risperdal, the antipsychotic medication she had been on for over two years at that point, Ms. F. said the mother she had known returned:

Lo and behold, she can talk again. She can read again ... she’s conversing ... it’s not just that she can walk now ... it’s her personality. She came back. She had been sleeping all the time. She was totally incoherent. She had no memory at all. She recognized no one. On the meds, she couldn’t remember if you were there while you were there.... She was drugged![82]

In this case, the antipsychotic medication had been initiated in a board and care home (similar to assisted living but smaller, with only six or fewer residents). Ms. F., her mother’s power of attorney, had consented to their use but had not been given full information about their side effects and risks. Upon Ms. C.’s admission to a nursing home, staff continued the antipsychotic drug. Once Ms. F. learned of its potential harm and insisted that the facility stop giving it to her mother, staff complied.

Human Rights Watch also visited some facilities that significantly reduced levels of antipsychotic drug use in the last year as a result of federal and state educational and training efforts, or due to governmental or corporate owners’ pressure. Interviews with nursing home administrators, directors of nursing, and other nursing staff provided another angle of insight into the extent to which antipsychotic drugs are used inappropriately. In many cases, staff of nursing homes that had reduced the use of antipsychotic drugs now felt very strongly that the drugs not be used inappropriately.

The director of nursing at one facility in Kansas who led an effort to reduce the rate of antipsychotic drug use in people with dementia reflected on the experience to Human Rights Watch: “It used to be like a death prison here. We cut our antipsychotics in half in six months. Half our residents were on antipsychotics. Only 10 percent of our residents have a mental illness.”[83] She continued:

Some doctors are misinformed. When we said we wanted to reduce the antipsychotics, we had to fight with the doctor. He said: ‘You understand if I do this they’re all going to go crazy?’But they don’t have behaviors because they need an antipsychotic. You actually see them decline when they’re on an antipsychotic. It’s just an adjustment when they’re first admitted.

There was a woman who would stand at the nurse’s station sobbing. We should have done a root cause analysis. But instead we shipped her off to psych. She was gone within a year: stiff muscles, couldn’t walk or talk. I think it’s sadder than watching someone with dementia decline.

You can reduce antipsychotics…. Residents have behaviors because their needs are not met. Not because of a lack of staff. We reduced the rate drastically and haven’t had to change staffing levels one bit. We did increase staff for activities, but not CNAs [certified nurse aides].

Taking off antipsychotics affects people differently: some are more verbal, more disruptive, louder, but not violent. Some sleep more, some sleep less. We had to educate the staff: don’t put them back on immediately. All antipsychotic prescriptions go through me. I do not allow PRN [prescription to take as needed] antipsychotics. Giving someone a Haldol one time has never been effective. It has to build up in the system.[84]

At another facility in Kansas, a nurse told Human Rights Watch about their experience reducing use, echoing many of the same themes:

We were at 55 percent antipsychotic drug rate before. Now we’re down to only people with a diagnosis [for which the FDA has approved the medications] on the drugs. They have a better quality of life because they’re not sedated. We’re not controlling their emotions or their dementia.At first everyone was like, ‘This is going to be awful. What do they want us to do?’ But we started with a resident with fewer behaviors and just did one or two a week. It was amazing. It’s helpful: it actually minimizes behaviors.

Before, when we slapped them with antipsychotics, they had to be in a wheelchair because they were so drugged up. But now that we’re meeting their needs, it’s easier on staff…. Their ADLs [activities of daily living] are better, their functioning.

If a resident comes in on an antipsychotic, we go over the info. We say, ‘We don’t usually use those here.’ The family usually agrees. If we start the reduction and it doesn’t work, we tell a geriatric psychiatrist to see them once a week. We have not had to change our staffing numbers. Without the antipsychotics, the residents take less time.[85]

In Illinois, the director of nursing at a facility explained a similar course of action:

This is our biggest, biggest issue: taking people off. You have to make an attempt to reduce. If someone is taking two antipsychotics, you try to lower the dose and you try taking them off one. We attempt reductions quarterly. We have not had problems with behaviors after slow reductions…. The pharmacist sends a report monthly, giving recommendations [to reduce] every month….We used to have a big antipsychotics problem. In 2011 more than half of the residents took them. Now everyone on an antipsychotic has a diagnosis. Usually they’re a totally different person, they’re back to life.[86]

An administrator in California described procedures his nursing facility has put in place to reduce reliance on antipsychotic medicines:

Our psychotropic committee meets monthly. We review all the patients on psychotropics. In 2010, more than 30 percent of the residents were on antipsychotics. Now it is just over 10 percent…. If someone is admitted with an antipsychotic, we monitor them for 72 hours. We notify the doctor. We observe the behavior. [Our consultant psychiatrist] comes in to assess if it’s necessary. We gather the baseline to have a point of comparison. We look at the diagnosis. If we get someone from geri-psych, they’re often agitated in the unit. Their behavior is not consistent. We put psychotropic medication on hold. We don’t restart it. We give them a chance to adjust.[87]

|

Inside Nursing Facilities with High Rates of Off-Label Antipsychotic Drug Use The conditions in about 20 of the 109 facilities visited, across all six states, were disturbingly grim. It was not uncommon for facilities to have stenches of urine, in particular on locked dementia units. Many facilities visited on weekends appeared to be severely understaffed. Many facilities were located in old buildings, sometimes former hospitals. The bare, cinderblock rooms—with uniform, old furniture and no privacy except a curtain with a runner on the ceiling—feel like “wards,” though use of the word is discouraged. People were often heard screaming or calling for help. Call light alarms—buttons residents can press that produces sound and light up at a nursing station to alert staff—would often make noise unceasingly. Human Rights Watch researchers encountered residents who desperately needed an aide to help them use the bathroom. In one case, we observed a nurse aide walk past a resident lying on the floor exposed, proceeding to carry a food tray. In several cases, residents had bruised faces or eyes that staff seemed unable to explain. Researchers observed individuals apparently trapped in “geri-chairs,” a geriatric recliner chair positioned in such a way that they could not get out. Positioning someone in this way constitutes a physical restraint.[88] Many people’s heads rested on tables or on their chests. Residents slept on couches in the lobby. It was unusual to visit a facility in which people were not sitting in wheelchairs arranged around a nursing station. Human Rights Watch staff observed very few activities aside from meals and television. Many facilities evinced a startling lack of privacy. Nursing staff enter residents’ rooms unannounced. We often saw staff who failed to close residents’ doors before engaging in tasks that exposed them, such as continence care and some types of therapy. Human Rights Watch observed residents being pushed in wheelchairs to shower rooms with only a sheet draped across their front. We observed residents moving about the facility with catheter bags exposed. |

III. Inappropriate and Non-Consensual Use of Antipsychotic Medications

The inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs on people with dementia in nursing facilities raises two principal human rights concerns. First, antipsychotic drugs are often administered without a medical purpose—as a last resort to treat psychosis in dementia, although they have not been found to be effective to this end—and for the convenience of facility staff. Such medically unnecessary use of medication may amount to torture or ill-treatment under international law. It may also amount to a prohibited “unnecessary drug” or a chemical restraint—a form of abuse—under US law. Second, these medications are frequently administered without free and informed consent. This practice constitutes forced medication under international law.

Chemical Restraints and Unnecessary Drugs: Use of Antipsychotic Medications for Reasons Other than Medical Need

Antipsychotic drugs are frequently administered to older people with dementia without clinical indication (a valid medical reason). This practice may in some cases rise to the level of torture or cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. As noted by the UN special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment in a 2013 report: “medical treatments of an intrusive and irreversible nature, when lacking a therapeutic purpose, may constitute torture or ill-treatment when enforced or administered without the free and informed consent of the person concerned.”[89] In June 2017, the UN special rapporteur on the right to health noted that informed consent is “a core element of the right to health, both as a freedom and an integral part of its enjoyment.”[90]

US regulations establish that antipsychotic drugs cannot be administered to nursing facility residents without a medical need based on a comprehensive assessment.[91] However, in some facilities, medical need is often not the primary reason antipsychotic drugs are prescribed and comprehensive assessments are not routinely conducted to determine whether a medical basis exists. CMS recognized facilities’ improper use of the drugs:

It has been a common practice to use various types of psycho-pharmacological medications in nursing homes to try to address behavioral or psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) without first determining whether there is an underlying medical, physical, functional, psychosocial, emotional, psychiatric, or environmental cause of the behaviors.[92]

Interviews with residents, family members, and facility staff provide numerous examples that residents are administered antipsychotic drugs without meaningful assessment of their medical necessity—an important consideration, though not one that, alone, justifies administering the medication.

A Culture of Antipsychotic Medication Use

Government reports and academic literature identify a “culture” of antipsychotic drug use as one of the potential explanations for their widespread use. In this context, the “culture” of a nursing facility, meaning the “shared values, beliefs and assumptions” of staff, “may exhibit itself as a facility-level preference for certain therapeutic modalities.”[93] When the prescriber and individual receiving treatment interact infrequently, which is often the case in nursing homes, the general treatment approaches may take on heightened significance: without routine personal evaluations by a physician prior to medication decisions, these decisions may follow even more heavily from the existing “beliefs and assumptions” about treatment, and may be less specific to the individual and circumstances at hand.[94] A 2015 study by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that so-called setting-specific factors—such as staff leadership, training and education levels, and quantity of staff—were the principal determinants of the prevalence of antipsychotic drug use rather than patient-specific factors, such as medical conditions or behaviors.[95] Academic studies have found that facility characteristics—not just a resident’s behavioral or neuro-psychiatric symptoms—are a strong predictor of the prevalence of psychotropic medication use.[96] One study found that “new nursing home residents admitted to facilities with high antipsychotic drug prescribing rates were 1.4 times more likely to receive antipsychotics, even after controlling for patient-specific factors.”[97]

In facilities with such a culture of the widespread use of these medicines, the off-label drug use is generally accepted as typical and unproblematic—even the best course of action for the resident. The GAO study found that in such facilities, nursing staff are more likely to believe the medications are truly helpful to residents, and are more likely to have lower levels of education and training around dementia and appropriate use of antipsychotic medicines. Studies have shown that low education among staff about antipsychotic use among people with dementia results in higher rates of use.[98] The GAO report also found that insufficient staff to engage residents in activities and to provide oversight of them may “make the nursing home residents susceptible to higher antipsychotic drug use.”[99]

In a letter to Human Rights Watch, the American Health Care Association (AHCA), the for-profit nursing home trade association, wrote:

[The] biggest challenge we have found is the mindset that clinicians, nurses and family all have that ‘behaviors’ in dementia are abnormal, resulting from dementia and that medications are an effective treatment. Difficulty in changing this belief is the greatest challenge.[100]

To this end, the AHCA has produced a fact sheet on antipsychotic drugs and people with dementia to inform families about the dangers and ineffectiveness of their use.[101]

Human Rights Watch obtained testimony from staff suggesting a culture in some facilities of excessive antipsychotic drug use in residents. In Texas, a facility’s admissions director seemed to believe that residents should be given the medication: “It’s a red alert if they don’t take them. We try to get them to.”[102] A nurse at a facility elsewhere in Texas, said: “If they’re agitated or having a moment and they don’t have a prescription, we call the doctor or psychiatrist…. If we still can’t handle them, we send them to behavioral [a psychiatric hospital].”[103]

Lena D., the daughter and power of attorney of Lucinda D., an 88-year-old woman in a California nursing facility, said she felt that the facility only attempted to silence with antipsychotic medication the symptoms that disturbed staff. To Ms. D, it was obvious that her mother had physiological conditions, such as an infection causing smell and fever, requiring medical attention instead of antipsychotic drugs to dull the expression of distress. “Every little thing, they want to put you on psych meds,” she said.[104] Ms. D. said that her mother was screaming from pain. “She would be sitting there, slumped over, mucus everywhere. I would go over and say, ‘She’s sick.’ UTI [urinary tract infection], pneumonia, pulmonary embolism—I’d scream too,” Ms. D. said, listing a number of the infections and harms she says that her mother has endured.[105]

In many instances, people living in nursing facility and their relatives—like most people—are inclined to defer to the recommendations of the healthcare provider unless they have a reason not to do so. As one long-time expert in Kansas put it: “The family rarely objects. They think, ‘They’re the doctor. They’re not going to hurt my mom.’”[106] A nurse in Texas explained: “If the medication is on the psychoactive list, we need consent.[107] We call the guardian, get verbal consent. Or not, if it’s declined. Then we’d call the doctor and start over. But we’ve never had to deal with a decline. Families want the best, and they trust the physician to do that.”[108]