Summary

[Senator and boxing legend] Manny Pacquiao says we’re not human. They should just let us be.

– Edgar T., an 18-year-old gay high school student in Manila, February 2017

Schools should be safe places for everyone. But in the Philippines, students who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) too often find that their schooling experience is marred by bullying, discrimination, lack of access to LGBT-related information, and in some cases, physical or sexual assault. These abuses can cause deep and lasting harm and curtail students’ right to education, protected under Philippine and international law.

In recent years, lawmakers and school administrators in the Philippines have recognized that bullying of LGBT youth is a serious problem, and designed interventions to address it. In 2012, the Department of Education (DepEd), which oversees primary and secondary schools, enacted a Child Protection Policy designed to address bullying and discrimination in schools, including on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. The following year, Congress passed the Anti-Bullying Law of 2013, with implementing rules and regulations that enumerate sexual orientation and gender identity as prohibited grounds for bullying and harassment. The adoption of these policies sends a strong signal that bullying and discrimination are unacceptable and should not be tolerated in educational institutions.

But these policies, while strong on paper, have not been adequately enforced. In the absence of effective implementation and monitoring, many LGBT youth continue to experience bullying and harassment in school. The adverse treatment they experience from peers and teachers is compounded by discriminatory policies that stigmatize and disadvantage LGBT students and by the lack of information and resources about LGBT issues available in schools.

This report is based on interviews and group discussions conducted in 10 cities on the major Philippine islands of Luzon and the Visayas with 76 secondary school students or recent graduates who identified as LGBT or questioning, 22 students or recent graduates who did not identify as LGBT or questioning, and 46 parents, teachers, counselors, administrators, service providers, and experts on education. It examines three broad areas in which LGBT students encounter problems—bullying and harassment, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, and a lack of information and resources—and recommends steps that lawmakers, DepEd, and school administrators should take to uphold LGBT students’ right to a safe and affirming educational environment.

The incidents described in this report illustrate the vital importance of expanding and enforcing protections for LGBT youth in schools. Despite prohibitions on bullying, for example, students across the Philippines described patterns of bullying and mistreatment that went unchecked by school staff. Carlos M., a 19-year-old gay student from Olongapo City, said: “When I was in high school, they’d push me, punch me. When I’d get out of school, they’d follow me [and] push me, call me ‘gay,’ ‘faggot,’ things like that.” While verbal bullying appeared to be the most prevalent problem that LGBT students faced, physical bullying and sexualized harassment were also worryingly common—and while students were most often the culprits, teachers ignored or participated in bullying as well. The effects of this bullying were devastating to the youth who were targeted. Benjie A., a 20-year-old gay man in Manila who was bullied throughout his education, said, “I was depressed, I was bullied, I didn’t know my sexuality, I felt unloved, and I felt alone all the time. And I had friends, but I still felt so lonely. I was listing ways to die.”

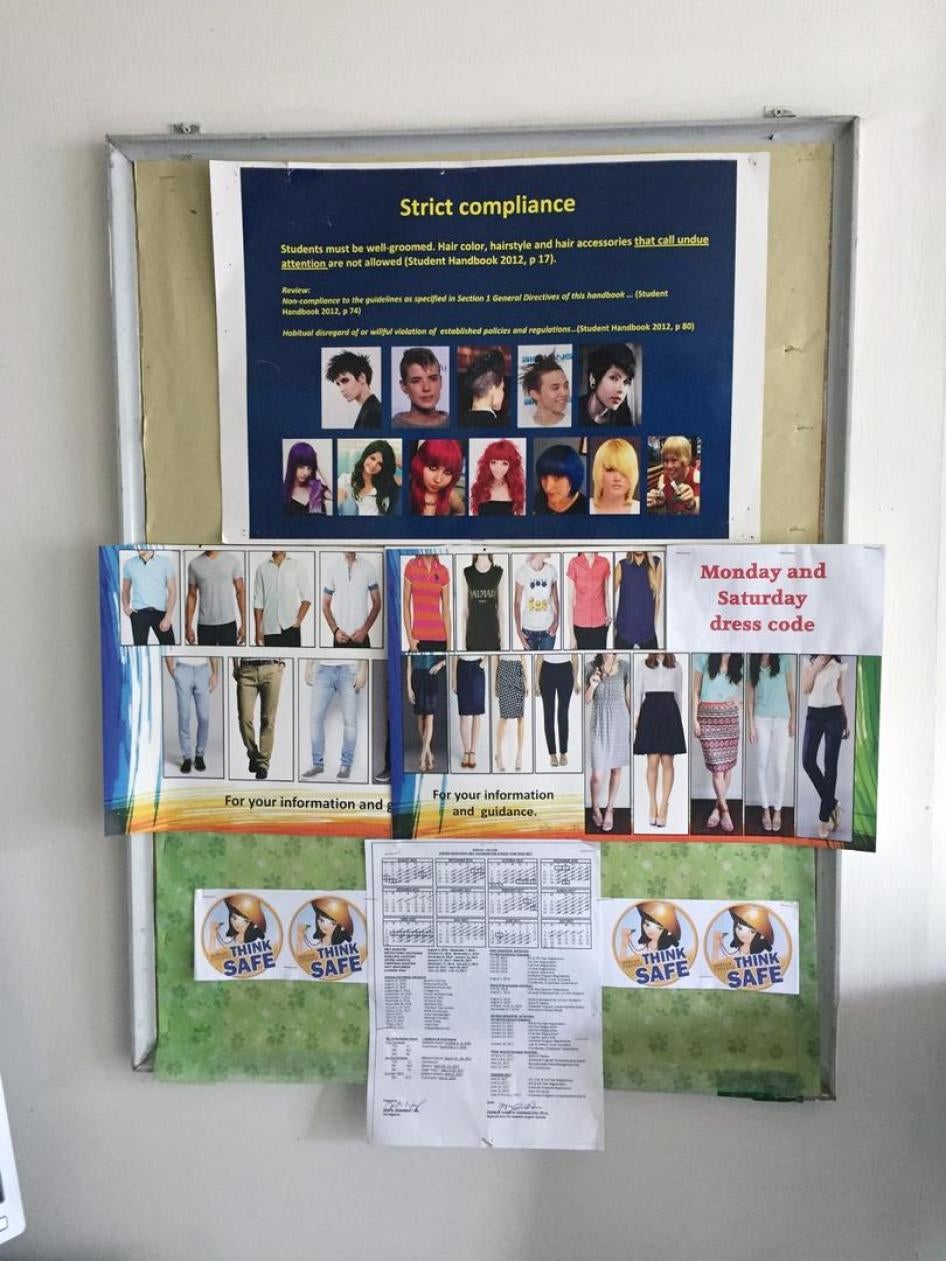

The mistreatment that students faced in schools was exacerbated by discriminatory policies and practices that excluded them from fully participating in the school environment. Schools impose rigid gender norms on students in a variety of ways—for example, through gendered uniforms or dress codes, restrictions on hair length, gendered restrooms, classes and activities that differ for boys and girls, and close scrutiny of same-sex friendships and relationships. For example, Marisol D., a 21-year-old transgender woman, said:

When I was in high school, there was a teacher who always went around and if you had long hair, she would call you up to the front of the class and cut your hair in front of the students. That happened to me many times. It made me feel terrible: I cried because I saw my classmates watching me getting my hair cut.

These policies are particularly difficult for transgender students, who are typically treated as their sex assigned at birth rather than their gender identity. But they can also be challenging for students who are gender non-conforming, and feel most comfortable expressing themselves or participating in activities that the school considers inappropriate for their sex.

Efforts to address discrimination against LGBT people have met with resistance, including by religious leaders. The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) has condemned violence and discrimination against LGBT people, but in practice, the Roman Catholic Church has resisted laws and policies that would protect LGBT rights. The CBCP has sought to weaken anti-discrimination legislation pending before Congress, for example, and has opposed implementation of comprehensive sexuality education in schools. Representatives of the Church warn that recognizing LGBT rights will open the door to same-sex marriage, and oppose legislation that might promote divorce, euthanasia, abortion, total population control, and homosexual marriage, which they group under the acronym “DEATH.” In a country that is more than 80 percent Catholic, opposition from the Church influences how LGBT issues are addressed in families and schools, with many parents and teachers telling students that being LGBT is immoral or wrong.

One way that schools can address bullying and discrimination and ameliorate their effects is by providing educational resources to students, teachers, and staff to familiarize them with LGBT people and issues. Unfortunately, positive information and resources regarding sexual orientation and gender identity are exceedingly rare in secondary schools in the Philippines. When students do learn about LGBT people and issues in schools, the messages are typically negative, rejecting same-sex relationships and transgender identities as immoral or unnatural. Juan N., a 22-year-old transgender man who had attended high school in Manila, said, “There would be a lecture where they’d somehow pass by the topic of homosexuality and show you, try to illustrate that in the Bible, in Christian theology, homosexuality is a sin, and if you want to be a good Christian you shouldn’t engage in those activities.” Virtually all the students interviewed by Human Rights Watch said the limited sexuality education they received did not include information that was relevant to them as LGBT youth, and few reported having access to supportive guidance counselors or school personnel.

When students face these issues—whether in isolation or together—the school can become a difficult or hostile environment. In addition to physical and psychological injury, students described how bullying, discrimination, and exclusion caused them to lose concentration, skip class, or seek to transfer schools—all impairing their right to education. For the right to education to have meaning for all students—including LGBT students—teachers, administrators, and lawmakers need to work together with LGBT advocates to ensure that schools become safer and more inclusive places for LGBT children to learn.

Key Recommendations

To the Congress of the Philippines

- Enact an anti-discrimination bill that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, including in education, employment, health care, and public accommodations.

To the Department of Education

- Create a system to gather and publish data about bullying on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in schools. Revise forms to more clearly differentiate and record incidents of gender-based bullying on the basis of sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity, and include these categories on all forms related to bullying, abuse, or violence against children.

- Revise the standard sexuality education curriculum to ensure it aligns with UNESCO’s guidelines for comprehensive sexuality education, is medically and scientifically accurate, is inclusive of LGBT youth, and covers same-sex activity on equal footing with other sexual activity.

- Issue an order instructing schools to respect students’ gender identity with regard to dress codes, access to facilities, and participation in curricular and extracurricular activities.

To Local Officials

- Enact local ordinances to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, particularly in education, employment, healthcare, and public accommodations.

To School Administrators

- Adopt anti-bullying and anti-discrimination policies that are inclusive of sexual orientation and gender identity, inform students how they should report incidents of bullying, and specify consequences for bullying.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted the research for this report between September 2016 and February 2017 in 10 cities on the major islands of Luzon and the Visayas in the Philippines. To identify interviewees, we conducted outreach through LGBT student groups, particularly at the university level. Human Rights Watch interviewed members of those groups as well as students who were known to those groups, whether or not they had experienced discrimination in school. We sought interviews with students of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities, but gay boys and transgender girls were disproportionately represented among the students identified by LGBT groups and the students who attended the group discussions.

Human Rights Watch conducted a total of 144 interviews, including with 73 secondary school students or recent graduates who affirmatively identified as LGBT or questioning, 25 students or recent graduates who did not affirmatively identify as LGBT or questioning, and 46 parents, teachers, counselors, administrators, service providers, and experts on education. Of the LGBT students, 33 identified as gay, 12 identified as transgender girls, 10 identified as bisexual girls, 6 identified as lesbians, 4 identified only as “LGBT,” 3 identified as transgender boys, 2 identified as bisexual boys, 2 identified as questioning, and 1 identified as a panromantic girl.

Interviews were conducted in English or in Tagalog or Visayan with the assistance of a translator. No compensation was paid to interviewees. Whenever possible, interviews were conducted one-on-one in a private setting. Researchers also spoke with interviewees in pairs, trios, or small groups when students asked to meet together or when time and space constraints required meeting with members of student organizations simultaneously. Researchers obtained oral informed consent from interviewees after explaining the purpose of the interviews, how the material would be used, that interviewees did not need to answer any questions, and that they could stop the interview at any time. When students were interviewed in groups, those who were present but did not actively volunteer information were not counted in our final pool of interviewees.

Human Rights Watch sent a copy of the findings in this report by email, fax, and post to DepEd on May 15, 2017 to obtain their input on the issues students identified. Human Rights Watch requested input from DepEd by June 2, 2017 to incorporate their views into this report, but did not receive a response.

In this report, pseudonyms are used for all interviewees who are students, teachers, or administrators in schools. Unless requested by interviewees, pseudonyms are not used for individuals and organizations who work in a public capacity on the issues discussed in this report.

Glossary

|

Bading |

A slang term for “gay” in Tagalog, usually used pejoratively. |

|

Bakla |

A Tagalog term for a person assigned male at birth whose gender expression is feminine and who may identify as gay or as a woman; it can be used pejoratively as a slur for an effeminate individual. |

|

Bayot |

A Cebuano term for a person assigned male at birth whose gender expression is feminine and who may identify as gay or as a woman; it can be used pejoratively as a slur for an effeminate individual.

|

|

Bisexual |

A sexual orientation in which a person is sexually or romantically attracted to both men and women.

|

|

Cisgender |

The gender identity of people whose sex assigned at birth conforms to their identified or lived gender.

|

|

Gay |

Synonym in many parts of the world for homosexual; primarily used here to refer to the sexual orientation of a man whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is towards other men. In the Philippines, the term “gay” can also refer to a person who is assigned male at birth but expresses themselves in a feminine manner or identifies as a woman.

|

|

Gender Identity |

A person’s internal, deeply felt sense of being female or male, neither, both, or something other than female and male. A person’s gender identity does not necessarily correspond to their sex assigned at birth.

|

|

Gender-Fluid |

A descriptor for people whose gender fluctuates and may differ over time. |

|

Gender Non-Conforming |

A descriptor for people who do not conform to stereotypical appearances, behaviors, or traits associated with their sex assigned at birth. |

|

Homosexual |

A sexual orientation in which a person’s primary sexual and romantic attractions are toward people of the same sex. |

|

Lesbian |

A sexual orientation in which a woman is primarily sexually or romantically attracted to other women. |

|

LGBT |

An acronym to describe those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. |

|

Panromantic |

A sexual orientation in which one’s romantic attraction is not restricted by sex assigned at birth, gender, or gender identity. |

|

Sexual Orientation |

A person’s sense of attraction to, or sexual desire for, individuals of the same sex, another sex, both, or neither. |

|

Tibo |

A slang term for “lesbian” in Tagalog, usually used pejoratively. |

|

Tomboy |

A term for a person assigned female at birth whose gender expression is masculine and who may identify as lesbian or as a man; it can be used pejoratively as a slur for a masculine individual who was assigned female at birth. |

|

Transgender |

The gender identity of people whose sex assigned at birth does not conform to their identified or lived gender. |

I. Background

The Philippines has a long history of robust LGBT advocacy. In 1996, LGBT individuals and groups held a solidarity march to commemorate Pride in Manila, which many activists describe as the first known Pride March in Asia.[1] Lawmakers began introducing bills to advance the rights of LGBT people in the country in 1995, including variations of a comprehensive anti-discrimination bill that has been reintroduced periodically since 2000.[2]

In the absence of federal legislation, local government units across the Philippines have begun to enact their own anti-discrimination ordinances that prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. As of June 2017, 15 municipalities and 5 provinces had ordinances prohibiting some forms of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.[3] Attitudes toward LGBT people are relatively open and tolerant; a survey conducted in 2013 found that 73 percent of Filipinos believe “society should accept homosexuality,” up from 64 percent who believed the same in 2002.[4] President Rodrigo Duterte has generally been supportive of LGBT rights as well. During his time as mayor, Davao City passed an LGBT-inclusive anti-discrimination ordinance, and on the campaign trail, he vocally condemned bullying and discrimination against LGBT people.[5]

Nonetheless, many of the basic protections sought by activists remain elusive. A bill that would prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation—and in later versions, gender identity—in employment, education, health care, housing, and other sectors has been regularly introduced in Congress since 2000.[6] The Anti-Discrimination Bill, or ADB, passed out of committee in the House of Representatives for the first time in 2015, but never received a second reading on the House floor and never passed out of committee in the Senate.[7] In the current Congress, the ADB has passed out of committee in the Senate for the first time, but at time of writing, it has not yet passed out of committee in the House.[8]

The anti-discrimination ordinances that have passed in the absence of federal legislation remain largely symbolic, as Quezon City is the only local government unit to follow the passage of its ordinance with implementing rules and regulations that are required to make such an ordinance enforceable.[9] Even if fully enforced, these municipal and provincial ordinances would collectively cover only 15 percent of the population of the Philippines.[10]

In a pair of decisions, the Supreme Court limited the possibility of legal gender recognition, ruling that intersex people may legally change their gender under existing law but transgender people may not.[11] The Philippines does not recognize same-sex partnerships, and although Duterte signaled openness to marriage equality in early 2016 while campaigning for the presidency and his legislative allies promised to support same-sex marriage legislation, he appeared to reverse course and express opposition to marriage equality in a speech in early 2017.[12] Moreover, HIV transmission rates have soared in recent years among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women, due to a combination of stigma, a lack of comprehensive sexuality education, barriers to obtaining condoms, and laws that prevent children under age 18 from purchasing condoms or accessing HIV testing without parental consent.[13]

Many of the efforts to advance LGBT rights have met with resistance from the Catholic Church, which has been an influential political force on matters of sex and sexuality. While the CBCP rejects discrimination against LGBT people in principle, it has frequently opposed efforts to prohibit that discrimination in practice. In 2017, for example, the Church sought amendments to pending anti-discrimination legislation that would prohibit same-sex marriage and allow religious objectors to opt out of recognizing LGBT rights.[14] It has also resisted efforts to promote sexuality education and safer sex in schools.[15]

The Church vocally opposes divorce, euthanasia, abortion, total population control, and homosexual marriage—which it groups under the acronym “DEATH”—and rejects recognition of LGBT rights with particular fervor when it is concerned those rights might eventually open the door to same-sex unions.[16] Beyond its influence in law and policy, the Church has shaped attitudes toward homosexuality and transgender identities throughout the country; citing religious doctrine, teachers, counselors, and other authority figures often impress upon students that it is immoral or unnatural to be LGBT.

In spite of this opposition, activists’ lengthy efforts to engage policymakers on LGBT issues have led to important protections for LGBT youth, as discussed below. But these protections have not been effectively implemented. They will need to be strengthened and expanded if they are to uphold the rights of LGBT youth in schools.

Existing Protections for LGBT Youth and Their Limitations

Child Protection Policy

In 2012, DepEd enacted a Child Protection Policy, which it describes as a “zero tolerance policy for any act of child abuse, exploitation, violence, discrimination, bullying and other forms of abuse.”[17] Among the acts prohibited by the policy are all forms of bullying and discrimination in schools, including on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.[18]

The policy requires all public and private schools to establish a “child protection committee,” which is to draft a school child protection policy to be reviewed every three years; develop programs to protect students and systems to identify, monitor, and refer cases of abuse; and coordinate with parents and government agencies.[19] The Child Protection Policy also details a clear protocol for handling bullying incidents and dictates that investigation by school personnel and reporting by the school head or schools division superintendent should be swift.[20]

As advocates have pointed out, however, monitoring and implementation of the Child Protection Policy is uneven. One analysis notes that “[u]nfortunately, no monitoring is done on its implementation and hence whether it is helping LGBT children in schools.”[21] A collective of LGBT organizations in early 2017 concluded “such mechanisms did not deter the prevalence of violence [LGBT] children experience.”[22] In interviews with Human Rights Watch, advocates and school personnel noted that many child protection committees are not trained to recognize or deal with LGBT issues, and overlook policies and practices, discussed below, that overtly discriminate against LGBT youth.[23]

The Anti-Bullying Law

In 2013, the Philippine Congress passed the Anti-Bullying Law of 2013, which instructs elementary and secondary schools to “adopt policies to address the existence of bullying in their respective institutions.”[24] At a minimum, these policies are supposed to prohibit bullying on or near school grounds, bullying and cyberbullying off school grounds that interferes with a student’s schooling, and retaliation against those who report bullying. The policies should also identify how bullying will be punished, establish procedures for reporting and redressing bullying, enable students to report bullying anonymously, educate students, parents, and guardians about bullying and the school’s policies to prevent and address it, and make a public record of statistics on bullying in the school.[25]

The Anti-Bullying Law does not specify classes of students at heightened risk for bullying. The implementing rules and regulations for the law, however, explain that the term “bullying” includes “gender-based bullying,” which “refers to any act that humiliates or excludes a person on the basis of perceived or actual sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).”[26] With the promulgation of these implementing rules and regulations, the Philippines became the first country in the region to specifically refer to bullying on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in its laws.[27]

The Anti-Bullying Law does not shield against all types of bullying, however. It does not account for instances where teachers bully LGBT youth.[28] As described in this report, many students and administrators are unaware of school bullying policies. Further, many students told Human Rights Watch that they did not feel comfortable reporting bullying, or did not know how to report bullying or what the consequences would be for themselves or the perpetrator. The datasets that DepEd releases regarding reported incidents do not disaggregate bullying on the basis of SOGI, so there is no available data to identify when such bullying occurs or what steps might be effective in preventing it.[29]

As with the Child Protection Policy, the implementation and monitoring of the Anti-Bullying Law has proven difficult. A United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) report observed that only 38 percent of schools submitted child protection or anti-bullying policies in 2013, and the “low rate of submission has been attributed to a low level of awareness of requirements of the Act and weak monitoring of compliance.”[30]

Comprehensive Sexuality Education

LGBT rights activists in the Philippines have long called for comprehensive sexuality education in schools. In 2012, Congress passed the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Law, which provides that “[t]he State shall provide age- and development-appropriate reproductive health education to adolescents which shall be taught by adequately trained teachers.”[31] The law and its implementing rules and regulations require public schools to use the DepEd curriculum and allow private schools to use the curriculum or submit their own curriculum for approval from DepEd, promoting a uniform baseline of information in both private and public schools.[32] In response to lengthy delays, President Duterte issued an executive order in January 2017 requiring agencies to implement the law; in part, the order instructs DepEd to “implement a gender-sensitive and rights-based comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) in the school curriculum.”[33]

DepEd has previously incorporated some sexuality education materials into school curricula, but implementation is uneven. The sexuality education curriculum has not yet incorporated the recommendations developed by experts, teachers, parents, students, and other stakeholders, nor has it been accompanied to date by training to ensure that it is taught correctly and effectively.[34] At the time of writing, there were no sexuality education modules targeted at LGBT youth.[35]

Effects of Bullying and Discrimination

As DepEd and the Congress recognized with their initial efforts to address bullying in schools, exclusion and marginalization can exact a damaging toll on the rights and well-being of LGBT youth. In addition to the documentation contained in this report, data collected by the Philippine government, academics, and civil society organizations illustrate how bullying and harassment, discrimination, and a lack of access to information and resources are adversely affecting LGBT youth across the Philippines.

In the Philippines, as elsewhere, violence and discrimination place LGBT youth at heightened risk of adverse physical and mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, substance use, and suicide.[36] As the Psychological Association of the Philippines has noted, “LGBT Filipinos often confront social pressures to hide, suppress or even attempt to change their identities and expressions as conditions for their social acceptance and enjoyment of rights. Although many LGBTs learn to cope with this social stigma, these experiences can cause serious psychological distress, including immediate consequences such as fear, sadness, alienation, anger and internalized stigma.”[37] This has been borne out in small-scale empirical studies on LGBT youth and mental health in schools. One such study found that LGBT high schoolers were preoccupied with stigma, violence, bullying, discrimination in school, and anxiety over their future career prospects.[38] Nor do these problems end upon graduation from high school; another study determined that “LGBT college students exhibited extremely underdeveloped emotional and social capacity because they continue to experience stigma, prejudice and discrimination in the Philippine society that served as specific stressors that have an impact on their emotional and social intelligent behaviors.”[39]

On a broader scale, the increased risk of suicidal thoughts and attempts for LGBT youth is evident in nationally representative data. The results of the Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Survey 3, for example, indicate that 16 percent of young gay and bisexual men in the Philippines had contemplated suicide, while only 8 percent of young heterosexual men had done so.[40] Young gay and bisexual men were also more likely to attempt suicide, with 39 percent of those who had contemplated suicide actually attempting suicide, compared to 26 percent of their heterosexual peers.[41] A similar trend was evident for young lesbian and bisexual women; 27 percent of young lesbian and bisexual women contemplated suicide compared to 18 percent of young heterosexual women,[42] and of those who considered suicide, 6.6 percent of lesbian and bisexual women made suicide attempts compared to only 3.9 percent of their heterosexual peers.[43] GALANG, a Philippine nongovernmental organization that works with lesbian and bisexual women and transgender people, found even higher rates among their constituencies. In a survey conducted in 2015, researchers from GALANG found that 18 percent of LBT respondents, who were almost all between the ages of 18 and 29, had attempted suicide.[44]

II. Bullying and Harassment

Whether it takes physical, verbal, or sexualized forms, in person or on social media, bullying endangers the safety, health, and education of LGBT youth.[45] Studies in the Philippines and elsewhere have found that, among young LGBT people, “low self-esteem and poor self-acceptance, combined with discrimination was also linked to destructive coping behaviours such as substance use or unprotected sex due to anxiety, isolation and depression.”[46] Benjie A., a 20-year-old gay man in Manila who was bullied throughout his education, said, “I was depressed, I was bullied, I didn’t know my sexuality, I felt unloved, and I felt alone all the time. And I had friends, but I still felt so lonely. I was listing ways to die.”[47]

When schools are unwelcoming, students may skip classes or drop out of school entirely. Felix P., a 22-year-old gay high school student in Legazpi, said, “I’ve skipped school because of teasing. In order to keep myself in a peaceful place, I tend not to go to school. Instead, I go to the mall or a friend’s house. I just get tired of the discrimination at school.”[48] Francis C., a 19-year-old gay student from Pulilan, said, “I just felt like I was so dumb. I wanted to stay at home, I didn’t want to go to school. And I would stay at home. Once I stayed at home for two weeks.”[49]

In many instances, the repercussions of bullying are long-lasting. Geoff Morgado, a social worker, observed that for some students bullying “turns into depression, because they feel they don’t belong,” and he believed that many students drop out because “[t]hey feel they don’t have a support group and feel isolated.”[50] Students who skip class, forgo educational opportunities, or drop out of school may experience the effects of these decisions throughout their lifespan. As a UNESCO report on school bullying notes, “[e]xclusion and stigma in education can also have life-long impacts on employment options, economic earning potential, and access to benefits and social protection.”[51]

Physical Bullying

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, students described physical bullying that took various forms, including punching, hitting, and shoving. Most of the students who described physical bullying to Human Rights Watch were gay and bisexual boys or transgender girls. These incidents persisted even after the passage of the Anti-Bullying Law. Carlos M., a 19-year-old gay student from Olongapo City, said: “When I was in high school, they’d push me, punch me. When I’d get out of school, they’d follow me [and] push me, call me ‘gay,’ ‘faggot,’ things like that.”[52] Felix P., a 22-year-old gay high school student in Legazpi, said, “People will throw books and notebooks at me, crumpled paper, chalk, erasers, and harder things, like a piece of wood.”[53] Benjie A., a 20-year-old gay man in Manila, said that once a classmate pushed him down the stairs at his high school, and added he still avoided his assailant as an adult for fear of physical violence.[54]

As detailed below, very few of the students interviewed reported bullying to teachers, either because they felt that reporting would not resolve the bullying or because they feared that reporting would lead to retaliation by other students and make the situation worse. In some instances, teachers also participated in harassment. Such behavior is not only discriminatory toward students of different sexual orientations and gender identities, but deters students from turning to teachers and administrators for help when they are bullied or harassed by their peers.

Sexual Assault and Harassment

For many LGBT students, bullying is often sexual in nature. Eric Manalastas, a professor of psychology at the University of the Philippines who has studied LGBT youth issues, observed “a theme of being highly sexualized and sexually harassed, especially for the gender non-conforming male students.”[55] Geoff Morgado, a social worker, described working with LGBT youth who told him that other students “grab the hand, or arm lock the child, or they force them into doggy style position. ‘This is what you want, right, this is what you want?’”[56] In interviews with Human Rights Watch, LGBT students described similar patterns of harassment and sexual assault in schools.

Gabby W., a 16-year-old transgender girl at a school in Bayombong, described a series of incidents that she experienced, including other students attempting to strip off her clothes in public, being forced into a restroom and sexually assaulted, and—on a separate occasion—being locked in a cubicle in a men’s restroom and sexually assaulted.[57]

Several gay or bisexual boys and transgender girls told Human Rights Watch that their fellow students had subjected them to simulated sexual activity or mock rape. Ruby S., a 16-year-old transgender girl who had attended high school in Batangas, described “[s]tudents acting like they were raping me, and then my friends saying, oh you enjoyed it, he’s cute. One of my classmates even said that LGBT people are lustful in nature, so it’s because you’re a flirt.”[58]

Gabriel K., a 19-year-old gay student who attended high school in Manila, similarly noted his classmates would “grab my hands, and they’d touch them to their private parts, and they’ll say to me that’s what gay is, that’s it.”[59] Jerome B., a 19-year-old gay man from Cebu City, recalled: “The worst thing, physically speaking, is they would—ironically, they hate gays, but they would dry hump me.… It was like rape to me. I felt violated.”[60]

Other LGBT students recounted slurs and stereotypes that were highly sexualized—for example, being catcalled in school or being labeled as sex workers. Sean B., a 17-year-old gay student in Bayombong, recalled how other students would shout “50 pesos, 50 pesos!” as he walked past, because “[t]hey think that we’re prostitutes.”[61] Gabby W., a 16-year-old transgender girl at the same school, said: “I feel bad about it—it’s so embarrassing. You’re walking around hundreds of people, and they shout that… and that shapes the perception of other people about us, that yelling by other people.”[62] Melvin O., a 22-year-old bisexual man from Malolos, recalled how in high school “people, especially the guys, would just sexually harass you, like you’re gay, you want my dick, stuff like that.”[63]

Rhye Gentoleo, a member of the Quezon City Pride Council, a city commission designed to enforce LGBT rights protections, observed that LGBT youth often face considerable pressure from heterosexual, cisgender peers to be sexually active because they are LGBT: “And that’s how the LGBT kids are being bullied as well. ‘Oh, you’re gay, can you satisfy me?’ They’re being challenged, how far can you go as a gay, how far can you go as a lesbian. And they have different ways of coping—some are hiding, but a lot of them are taking the challenge, being sexually active, without thinking of the consequences.”[64] As discussed below, the sexualization of LGBT youth is exacerbated by the absence of LGBT-inclusive sexuality education, which leaves many youth ill-equipped to protect themselves and their sexual health.

Verbal Harassment

The most common form of bullying that LGBT students reported in interviews with Human Rights Watch was verbal harassment. This included chants of “bakla, bakla,” “bayot, bayot,” “tomboy,” or “tibo,” using local terms for gay, lesbian, or transgender students in a mocking fashion.[65]

Daniel R., an 18-year-old gay student in Bacacay, said “People will say gay—they’ll say ‘gay, gay,’ repeating it, and insulting us.”[66] Ernesto N., a gay teacher in Cebu City, observed, “Here in the Philippines, being called bayot, it’s discrimination. It’s being told you’re nothing, you’re lower than dirt. That you’re a sinner, that you should go to Hell.”[67]

Many students described being labeled as sinners or aberrations. Leon S., a 19-year-old gay student from Malolos, said that “[s]tudents would say that homosexuality is a sin.”[68] Marco L., a 17-year-old gay student in Bacacay, said that “[p]eople say ipako sa krus, that you should be crucified.”[69] Gabriel K., a 19-year-old gay student who attended high school in Manila, said people told gay students “that you have to be crucified because you’re a sinner.”[70]

Anthony T., a gay student at a high school in Cebu City, said: “Some of my classmates who are religious say, ‘Why are you gay? It’s a sin. Only men and women are in the Bible.’ And I say, ‘I don’t want to be like this, but it’s what I’m feeling right now.’ Even if I try, I can’t change it. And if they ask why I am a gay and why do I like gays, I say, ‘it’s how I feel, I’ve tried, and I can’t be a man.’”[71]

Others described how they were treated as though they were diseased or contagious. Felix P., a 22-year-old gay high school student in Legazpi, noted: “Here, they call us ‘carriers’—there’s a stereotype that gays are responsible for HIV.”[72] Benjie A., a 20-year-old gay man in Manila, recalled a classmate telling him “don’t come near me because you’ll make me gay.”[73]

Some students noted verbal harassment that was predicated on the idea that their sexual orientation or gender identity was a choice. Analyn V., a 17-year-old bisexual girl in Mandaue City, observed, “It is inevitable that they’ll judge—like, you should date a real man instead of a lesbian because your beauty is wasted.”[74] Dalisay N., a 20-year-old panromantic woman who had attended high school in Manila, said: “When I was walking with my girlfriend, [other students] would tease us—they would say things like ‘it’s better if you have a boyfriend,’ or they would shout things like ‘you don’t even have a penis.’”[75]

The high levels of verbal harassment that LGBT youth faced in schools had repercussions for their experiences in schools. Teasing prompted some students to remain closeted, particularly in the absence of other positive resources to counteract negative messaging. Jerome B., a 19-year-old gay man from Cebu City, remarked, “For the majority of my life, I was in the closet. It’s really hard for me to express what I feel. In my school, being gay is really—it’s really the worst thing you could be. You’ll be treated like shit…. So being gay was a curse, I thought for a long time.”[76]

Some students altered their behavior or personality in an attempt to avoid disapproval from classmates. Patrick G., a 19-year-old gay man who had attended high school in Cainta, said:

They were teasing me for being effeminate. I developed this concept of how a man should walk, how a man should talk. It became—maybe because of them calling me malamya [effeminate], I became the person that I’m not. I was forced to be masculine, just for them to stop teasing me.[77]

Patrick’s experience is not unique. As one elementary school counselor observed, youth are “quite intimidated that kids will call them gay—even in Grade Six, you can tell that they don’t want to be called gay or lesbian.”[78] When verbal harassment became unbearable, some students removed themselves from the school environment entirely. Ella M., a 23-year-old transgender woman who had attended high school in Manila, noted that “[v]erbal bullying was why I transferred.”[79]

In addition to verbal harassment by peers, many LGBT students described verbal harassment and slurs from teachers and administrators. Patrick G., a 19-year-old gay man, said that at his high school in Cainta, “[s]ometimes teachers would join in with ‘bakla, bakla.’”[80] Jerome B., a 19-year-old gay man from Cebu City, said that “it really feels bad, because the only figure you can count on is your teacher, and they’re joining in the fun, so who should I tell about my problems?”[81]

Often, disapproval from teachers was expressed in overtly religious terms. Wes L., an 18-year-old gay student at a high school in Bacacay, said, “My teacher in school told me that people are created by God, and God created man and woman. They say that gays are the black sheep of the family, and sinners.”[82] Danica J., a 19-year-old lesbian woman who had attended a high school in Cainta, described how a teacher “told me not to be lesbian anymore, and then he prayed over my head. He prayed for me. There were no supportive teachers at the school.”[83]

In some cases, disapproval from teachers was voiced in front of other students, reinforcing the idea that LGBT youth are wrong or immoral. Gabriel K., a 19-year-old gay student who attended high school in Manila, recalled how a teacher brought him before his peers and “compared me to the others—that being gay is not welcome into heaven, and made an example in front of the whole class.”[84] Benjie A., a 20-year-old gay man in Manila, recalled how a teacher in elementary school called him and two other effeminate students in front of her biology class to tell the students:

There’s no such thing as gays and lesbians. There’s man and woman, and marriage is only between a man and a woman.” And I was only turning 12—I hadn’t hit puberty at the time, and you’re telling me not to be gay!? How could I even tell? And everyone was looking at me—I was like, okay, teacher, I respect your religion, but come on, I’ve been bullied for five years. Haven’t I had enough?[85]

Cyberbullying

As students interact with their peers on social media and in other virtual spaces, cyberbullying has increasingly impacted LGBT youth in schools. LGBT students described anti-LGBT comments and slurs as well as rapidly spreading rumors facilitated by social media.

Leon S., a 19-year-old gay student from Malolos, said: “They would post things online, which is a far easier thing to do than say it personally.... I would post something, and they would comment about my sexual orientation. It was the usual, bakla, bading.”[86] Marisol D., a 21-year-old transgender woman, similarly noted, “Some of my friends would put comments like bakla, bakla on my posts. You just ignore it… [b]ecause if they see that you’re being affected they’ll bully you more.”[87] Carlos M., a 19-year-old gay student from Olongapo City, said, “My classmates would post stuff online—memes against LGBT, Satan saying ‘I’m waiting for you here.’”[88]

Jack M., an 18-year-old gay high school student in Bayombong, was a victim of rumors spread through social media: “They’ll make up stories. People will tell others [online] that I had sex with a person, even if it’s not true.”[89]

Cyberbullying also draws on stereotypes about LGBT students, and particularly transgender women and girls, with harsh disapprobation for those who were perceived to fall short of social expectations. Geoff Morgado, a social worker, observed that:

There are lots of trans women who are coming out on different platforms on social media, and they’re really bullied. Because people will base it on the looks—if you’re a trans woman, especially, they’ll say you’re not allowed to be a trans woman because you’re too ugly, or your skin is so dark. They say you have to be pretty, you have to be white, or you have to look like a woman before they decide you’re a transgender woman.[90]

Morgado added that many same-sex couples in schools must also contend with comments on social media criticizing their conformity to gender norms and the appropriateness of same-sex pairings.[91]

Intervention and Reporting

Human Rights Watch heard repeatedly that schools fail to instruct students about what bullying entails, how to report incidents when they occur, and what the repercussions will be. As a result, many schools convey tacit acceptance to perpetrators and leave victims unaware of whether or how they can seek help.

Both the Child Protection Policy and Anti-Bullying Law require that schools develop and convey policies regarding bullying and harassment. Nonetheless, many students interviewed by Human Rights Watch indicated they were unaware of the policies in place. Danica J., a 19-year-old lesbian woman who had attended high school in Cainta, said, “We didn’t get any information about bullying as high school students.”[92] Others said they had received some instruction on bullying, but it was incomplete or did not address LGBT issues. Leon S., a 19-year-old gay student from Malolos, said “[t]he school did anti-bullying seminars, but it didn’t really address bullying about your sexual identity—the seminar is more general in scope.”[93]

When students do not know how to report bullying and harassment or do not believe that reporting would be effective, they are unlikely to bring incidents to the attention of teachers and administrators. Jerome B., a 19-year-old gay man from Cebu City, said:

I would not tell the teacher. I was too ashamed. Because if I would tell the teacher, they would say, oh, you’re such a gay person, you have such weak feelings, you’re such a tattle tale. So I would just keep it to myself and endured the harassment for a long time, until I graduated.[94]

Some students attributed their reluctance to report bullying to the negative messages about LGBT people they’d received from teachers. Students identified negative messaging in various classes, including “values education,” a subject taught throughout secondary school to instill positive values and morals in Filipino youth. Although many students told Human Rights Watch that their values education courses were largely secular and focused on topics like respect and responsibility, others described overtly religious lessons that disparaged LGBT people. Dalisay N., a 20-year-old panromantic woman who had attended high school in Manila, remarked: “There’s a lot of teasing and bullying, but we don’t talk about it with teachers or counselors. I think that’s because of what they’re trying to teach us, in values education, things like that.”[95]

Interviews with LGBT students indicate that many teachers fail to intervene when they witness bullying or harassment occurring or it is brought to their attention, even since passage of the Anti-Bullying Law, which in turn discourages students from reporting cases of bullying. Analyn V., a 17-year-old bisexual girl in Mandaue City, said, “Teachers don’t step in. They think it’s a joke. But some jokes are below the belt. We conceal being hurt because maybe they think it’s overreacting.”[96] “The teachers don’t say anything or get mad —if they hear people saying bakla, they just smile or laugh,” said Felix P., a 22-year-old gay high school student in Legazpi. “Teachers might ask the students to stop, but they don’t punish them. And as soon as they leave, the bullying happens again.”[97]

In some instances, teachers and administrators may not have intervened because they had not received proper training or were unsure of their responsibilities. In one interview, a high-level administrator at a high school in Mandaue City remarked that she had never heard of the Anti-Bullying Law.[98] In another interview, a DepEd trainer and educator erroneously stated that the law did not cover LGBT students.[99] According to Rowena Legaspi of the Children’s Legal Rights and Development Center, uncertainty about existing protections is due in part to the tendency for school administrators to simply adopt policy templates from DepEd without tailoring them to the school environment, undergoing training, or fully understanding what is being implemented.[100]

***

As a coalition of Philippine organizations has noted, in many instances, “[b]ullying and other forms of violence within the schools or education settings is steered by institutional policies,” for example, “through gender-insensitive curricula, SOGI-insensitive school policies (e.g. required haircuts and dress codes), and [a] culture of bullying.”[101] As evidenced in the following sections, the many forms of exclusion and marginalization that LGBT youth experience in Philippine schools can reinforce one another. In schools where LGBT youth lack information and resources, for example, they may struggle more deeply with their sexual orientation or gender identity or be unsure where to turn for help. In schools where policies discriminate against LGBT youth, they may be placed in situations where bullying by peers is likely to occur and may feel administrators are unlikely to help them.

III. Creating a Hostile Environment

In addition to bullying and harassment, LGBT students encounter various forms of discrimination that make educational environments hostile or unwelcoming. To ensure that all youth feel safe and included in schools, school administrators should examine policies and practices that punish LGBT students for relationships that are considered acceptable for their heterosexual peers, restrict gender expression and access to facilities, and stereotype LGBT youth in a discriminatory manner.

Discrimination takes a toll on LGBT students’ mental health and ability to learn. Some students who encountered discrimination in schools reported that they struggled with depression and anxiety.[102] Others told Human Rights Watch that discrimination made it difficult to concentrate on the material or participate in class,[103] or caused them to skip classes, take a leave of absence, or drop out entirely.[104]

Both the Philippine Constitution and the Philippines’ international treaty obligations recognize a right to education. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has emphasized that the right to education, like other rights, must not be limited on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.[105] For educational environments to effectively serve all youth, they must treat LGBT youth the same as they treat their non-LGBT peers.

School Enforcement of Stereotyped Gender Norms

Uniforms and Hair Length Restrictions

It is common practice for secondary schools in the Philippines to require students to wear uniforms. Under these policies, the attire is gender-specific and the two options, male or female, are typically imposed upon students according to the sex they were assigned at birth.

In addition to clothing, many secondary schools have strict hair-length restrictions for their students, particularly for boys. Almost all interviewees reported that boys could not grow out their hair past ear-length or dye their hair at their schools, and many also noted that girls were prohibited from wearing their hair shorter than a permissible length.

Students whose gender expression differed from the norms associated with their sex assigned at birth told Human Rights Watch how these restrictions impeded their education. Students reported that being forced to dress or present themselves in a manner that was inconsistent with their gender expression made them unhappy[106] and uncomfortable,[107] lessened their confidence,[108] and impaired their concentration.[109] As Del M., a 14-year-old lesbian student who was allowed to wear the boys’ uniform, remarked, “It’s easier for me to learn wearing the boys’ uniform.”[110]

At many of these schools, students who did not conform to the uniform and hair-length requirements faced disciplinary action. Common punishments included being sent to the guidance or discipline offices and mandatory community service. Ella M., a 23-year-old transgender woman who had attended high school in Manila, described being punished solely on this basis of her general gender presentation. She said that her school’s handbook punished an “act of effeminacy,” not further defined, with “a conduct grade of 75, which basically means you did something really really bad. I might as well have cheated.”[111]

For many transgender or gender non-conforming students, the strict uniform and hair-length requirements were sources of intense anxiety and humiliation, and in some cases led to extended school absences and even leaving schooling entirely.[112]

Marisol D., a 21-year-old transgender woman, said:

When I was in high school, there was a teacher who always went around and if you had long hair, she would call you up to the front of the class and cut your hair in front of the students. That happened to me many times. It made me feel terrible. I cried because I saw my classmates watching me getting my hair cut.[113]

Other interviewees reported similar incidents in which teachers or prefects would publicly call out students in violation of the restrictions and forcibly cut their hair in front of the class.

Jerome B., a 19-year-old gay man, said that in his high school in Cebu City:

It applies for all boys. If [your hair] touches the ear and you don’t cut it, the school will cut it for you, and they do it in front of your classmates. The Student Affairs Officer who enforces the rules, once a month he would go to each classroom and knock, and say, “All those with long hair go outside,” and he would go one by one with these large, rusty scissors like the kind you see in horror movies, and they’d cut our hair in front of everybody….

I think on purpose, he’d cut it very badly.[114]

In most cases, teachers and administrators provided little to no explanation for the hair-length requirements when students asked about the policies at their respective schools. Felix P., a 22-year-old gay high school student in Legazpi, told Human Rights Watch:

Before, I used to have long hair. I entered the school grounds, but the school administrator asked me to cut [my] hair or else I couldn’t go in. So I was forced to cut my hair and wear the male uniform.… There’s no explanation about cutting the hair. I’ve asked them if having short or long hair will affect my performance as a student, and the administrators say, “No, you just have to cut your hair, you’re a boy.”[115]

As Lyn C., a 19-year-old transgender woman in Manila, recounted, gendered clothing requirements also extended to school-sponsored events such as prom nights:

For our prom night, I asked our principal if I could wear a gown, but he didn’t allow it. Back in high school I didn’t have long hair or makeup, so he said, “What would you look like as a boy wearing a gown? It’s ridiculous!” I felt really discriminated against. I had a friend who was also transgender and we were both begging the administration but they wouldn’t allow it. They told us that we would be an embarrassment to the school, that people would laugh at us at prom, and that “You’re guys and you need to wear guys’ clothes.”[116]

In some instances, students were able to request a full switch of the uniforms according to their gender identity. However, agreements to alter uniform requirements were usually not the result of consistently applied policies designed to respect students’ right to free expression of their gender identity, but rather of the compassion of a specific school administrator or principal. In one of the few such cases Human Rights Watch documented, a lesbian student was permitted to wear the boys' uniform primarily because the school’s principal was himself openly gay and supportive of the petition.[117]

Even when students are formally permitted to wear the uniforms of their choice, however, school personnel at times harass or humiliate them in practice. Gabby W., a 16-year-old transgender girl in high school in Bayombong, told Human Rights Watch:

They’re questioning us about our makeup and dress… not only the students, but the teachers too. It’s so disrespectful. We enter the gate and the security guard will say, “Why is your hair so long, are you a girl?” And it really hurts our feelings.[118]

|

Uniform and Hair Length Restrictions in Universities Although this report focuses on secondary schools, many interviewees said they had experienced similar issues with uniform and hair-length restrictions at the university level. In some extreme cases, students who repeatedly “cross-dressed”—a term that schools and some students used to describe gay, lesbian, or transgender students expressing their gender in school—were suspended or even expelled. According to Danica J., a 19-year-old lesbian woman at a university in Manila, “people are punished if they violate the uniform policy. It’s like a disciplinary action. They won’t let you in if you’re cross-dressing, and after a couple times, you can be suspended or expelled.”[119] As one 19-year-old university student in Caloocan told Human Rights Watch, In our school, there are policies that if you cross-dress you will be suspended for one day. Your freedom of expression is very limited. I know we had policies against LGBTQ. We had hair-length restrictions—for guys, the shaved hair has to be three inches on the side, four inches in the back. So every time, if the hair passes three to four inches, the faculty will cut our hair. And even here in the university, the handbook says male students must only have hair to their ears.[120] Even in universities without formal uniform or hair-length policies, however, transgender and gender-fluid students sometimes reported harassment or reprisals from teachers, classmates, and administrators when they expressed their gender. Patrick G., a 19-year-old gay man in Manila, said that despite a policy at his university guaranteeing students the freedom to dress based on their gender expression, he was aware of one case in which the Discipline Office (DO) summoned a transgender woman to interrogate her about her clothing: “She was within the scope of the policy, but the DO said, ‘Are you not ashamed of what you’re wearing? Are you not thinking of how others will think about how you dress?’”[121] Dalisay N., a 20-year-old panromantic woman at a university in Caloocan, said: When I enrolled in college, I even talked to the head of the office for student affairs, and told her I’m not comfortable wearing a skirt. They allow us to wear Carlos M., a 19-year-old gay student at the same university, said that university security guards forced transgender women to go home if they were wearing makeup or long hair.[123] According to Lyn C., a 19-year-old transgender woman at a university in Manila: The first three years of my school days we were just hiding ourselves, because if the guards and administration know that we’re transgender we’ll be punished. When the guard knows you’re transgender, you’ll be sanctioned. They’d send you to the discipline office… you’d get community service or suspension. It was really difficult for us, to hide our very identities.[124] Lyn’s university removed its uniform and hair-length restrictions in January 2017 after years of persistent advocacy from student groups. However, even after the changes, some students still faced discrimination from teachers. Several interviewees also told Human Rights Watch that they or their classmates had dropped out of classes or transferred sections at their universities to avoid conflicts with professors who were hostile to transgender students.[125] Certain departments and colleges also tend to have more stringent uniform and hair-length restrictions than their affiliated universities, often forcing transgender students to conform in order to matriculate. Some students and professors identified colleges of hospitality, management, and education among those requiring gendered clothing, irrespective of the broader university’s policies.[126] |

Access to Facilities

For students who are transgender or identify as a sex other than their sex assigned at birth, rigid gender restrictions can be stressful and make learning difficult. One of the areas where gender restrictions arose most often for LGBT interviewees was in access to toilet facilities, known in the Philippines as “comfort rooms” (CRs). Most interviewees said that their schools required students to use CRs that aligned with their sex assigned at birth, regardless of how they identified or where they were most comfortable. Some said that both female and male CRs posed safety risks or made them uncomfortable, but that all-gender restrooms were scarce.

Requiring students to use restrooms that did not match their gender identity or expression put them at risk of bullying and harassment. Gabby W., a 16-year-old transgender girl in Bayombong, said that “boys peep on us when we use the boy’s restroom,” and “they say we’re trying to have sex with them, things like that.”[127] Reyna L., a 24-year-old transgender woman, agreed: “Boys or male persons are always vigilant when it comes to gays and transgenders. Any time they see us going in the CR, they sometimes look at you like I’m going to do something, with malice, or look at us like a maniac.”[128] Because of this, Gabby said, “Sometimes you don’t have a choice but to go home and use your own restroom.”[129]

Some schools punish students for using the CRs where they felt comfortable. Ruby S., a 16-year-old transgender girl who attended high school in Batangas, said:

I was called by the administration when I used the CR for the girls. They said you’re not allowed to use it just because you feel like you’re a girl. They used that as a black mark on my campaign for student council. They said, even though he wants to be student council president, he doesn’t follow the rules.[130]

Even students who were not formally punished described being humiliated by faculty and staff policing gendered spaces. Alon B., a gay teacher in Cebu City, said that the administration at the school where he taught had posted “a printed sign that says only biological females are able to be in this bathroom.”[131]

At least one secondary school has created all-gender CRs that any person can use regardless of their gender identity.[132] But while some students may feel more comfortable using all-gender CRs, others prefer to use the same CRs that everybody else uses. Reyna L., a 24-year-old transgender woman, said, “I’d like to use the female comfort room, and be treated as a normal person…. If I can’t, I’d rather not use it at all.”[133] Allowing students to use CRs consistent with their gender identity can be a simple and uncontroversial step that makes a positive difference for transgender youth. Ella M., a 23-year-old transgender woman from Manila, noted that when she transferred to a new high school:

I was able to use the girls’ bathroom, freely, since most of the peers were really supportive. And there hasn’t been any incidents of, like, adverse reactions to some guys going into the girls’ bathroom. My teacher knew I was doing it—he just warned me that some girls might get offended. But nobody complained.[134]

|

Access to Facilities in Universities Policies that prevent students from accessing restrooms consistent with their gender identity exist in post-secondary institutions as well. Dalisay N., a 20-year-old panromantic woman at a university in Caloocan, said: Some of the trans women in our support group, the guards would shout, “Why are you using that restroom? You’re not allowed in there,” which for me is disrespectful. Why do they care? They’re just putting on makeup, and they just want to feel safe when they pee. Because there’s a lot of teasing and bullying in the men’s room.[135] Marisol D., a 21-year-old transgender woman, said that in her university, instructors reported transgender students to the discipline office for using the “wrong” restroom.[136] Ace F., a 24-year-old gay man in Manila, noted that another member of his university’s LGBT group “was apprehended by our school administration—she’s a transgender woman and she used a girl’s bathroom. The office of student behavior gave her a minor disciplinary offense.”[137] As in secondary schools, university policies that prevent students from accessing facilities on the basis of their gender identity are discriminatory and function to undermine student safety, health, privacy, and the right to education. |

Gender Classifications

Even when students identify as transgender, some teachers and administrators insist on treating them as their sex assigned at birth. David O., a high school teacher in Mandaue City, recounted a story in which a transgender boy and his parent wanted the school to socially recognize him as a boy, but another teacher insisted that the student was female and should be treated as a girl.[138]

Imposing strictly gendered activities and requiring students to participate according to their sex assigned at birth can constitute discrimination and impair the right to education. Human Rights Watch found that some schools require boys to take physical education classes and girls to take arts classes, for example, which reinforces stereotypes and deprives boys who want to pursue art and girls who want to pursue sports of educational opportunities.[139] It can also be profoundly stigmatizing and uncomfortable for students. As Felix P., a 22-year-old gay high school student in Legazpi, said: “During flag ceremony, students used to line themselves up by male or female, and I think it’s really difficult—which line should I go in? I don’t think I’m welcome in the boys’ group, and I’m not allowed to go in the women’s group.”[140]

Hostility Toward Same-Sex Relationships

Many schools in the Philippines have policies restricting public displays of affection among students, and outline those policies in student handbooks or codes of conduct. Yet LGBT students reported that their relationships were policed more carefully or punished more harshly than their non-LGBT peers. In particular, young lesbian and bisexual women and transgender men who attended exclusive schools—those that are only open to one sex—reported that their friendships and relationships were closely scrutinized and policed by school staff.

Juan N., a 22-year-old transgender man who had attended high school in Manila, said:

When I was in high school, I had a girlfriend, but we were really careful about it, because once it becomes known—especially to admins, who are mostly nuns, and when your teachers know you’re in a relationship with another woman, they try to correct you, they would reprimand you, give you violations based on what you’ve done.[141]

Angelica R., a 22-year-old bisexual woman who had attended high school in Manila, said that more masculine girls were especially targeted to keep them from becoming close with other girls:

If someone is really butch, our professors are always watching us. They’re talking among themselves and student council to pinpoint who was involved in same-sex relationships. There’s not much bullying among the students, but it was oppression from the administration. I remember this particular experience where one of our professors went into our class and said, did you know, girls are for boys, girls are not for girls, we know who’s involved in same-sex relationships, and if you don’t stand up, we’ll make you stand up.… So as a result, some of my butch classmates would attempt to be feminine, they would hide it, they would wear more feminine clothes. You could see they were unhappy. It’s a struggle.[142]

The same standards were not applied to heterosexual students, as teachers and administrators acknowledged. Even a gay teacher defended this double standard, citing social and religious conventions. Ernesto N., a gay teacher in Cebu City, said of same-sex couples dating in schools: “It’s just like having sex in school! Goodness! It’s really our culture.... For boys and girls it’s okay, but not for LGBT.”[143]

Pressure to Conform to Stereotypes

LGBT youth also described the pressure that teachers and administrators imposed on them to act in a stereotypical fashion.

Many of the LGBT youth interviewed by Human Rights Watch emphasized that, to the extent they were respected in school, they had earned that respect by being better students than their peers. Often, this meant that LGBT students were tasked with more work or responsibilities than other students as part of the price they paid to be accepted and respected. Eric Manalastas, a psychology professor at the University of the Philippines who has conducted research on LGBT youth issues, found that:

[G]ay students or those who are out or coded as gay [are sometimes] given extra work at school, including extracurricular work—being asked to be the MC at an event, or fixing the stage for a performance, being asked to clean up after school. Because of a stereotype that they’re reliable, or combine the best of both male and female students, a kind of androgynous thing going on. I hear that from students but also teachers—teachers who say, I love my gay students, they’re so helpful, I ask them to stay after school. They’re tasked with leadership roles.[144]

In a similar vein, one university instructor told Human Rights Watch that “as faculty members, we’re often delegating responsibilities to members of the LGBT community because we know they’ll do it well.”[145] Rodrigo S., a gay high school teacher in Dipolog City, observed: “I guess there are pressures for gay children—and I see this—to do really well in class, I guess, because that kind of saves you from being bullied. Like, you ought to get somewhere so people won’t make fun. A lot of my students wanted to excel in whatever they were doing, being artistic, because they wanted to be accepted. A lot of my gay students were at the top of the class.”[146]

In interviews, it appeared that many LGBT students had internalized the message that their acceptance as LGBT was conditional on being dutiful, talented members of the school community. Virgil D., a 20-year-old gay man in high school in Bacacay, said, “I think the gays should dress properly and be responsible. And then they’ll be treated well.”[147] Mary B., an 18-year-old transgender woman in a high school in Manila, said:

For us to be better accepted, we’re taking proactive measures to be accepted into the community. We’re setting good examples. We engage in extracurricular activities, we organize events for the school, we stop bullying when we see it, we promote child protection. We become model citizens, model students, and it improves our stature.[148]

Manalastas found that the demand to be “respectable” put a heavy burden on LGBT students who did not conform: “It may be that gay students are warmly received, generally speaking, but if you’re characterized as one of the indecent ones—perceived as very sexual, very loud, very gender non-conforming or outré, it’s different.” He added that LGBT people from lower socioeconomic strata often face double discrimination, as exemplified by the common insult baklang kalye—“you’re bakla and also you come from the streets, you don’t have a proper house, you’re poor.”[149]

Some students were keenly aware of these conditions and expressed frustration with them, voicing a desire to be treated with the same inherent respect as their non-LGBT classmates. Felix P., a 22-year-old gay high school student in Legazpi, said:

Sometimes teachers say things like you have to respect gays and lesbians because they’re the breadwinners for their family, they’re reliable, they’re good at makeup, costume making, talent…. I’m proud of being gay—my teacher says something good about being gay, but why do I have to earn that respect? It’s not 100 percent good. Some of my gay classmates don’t have those talents, and how does that make them feel?[150]

Jerome B., a 19-year-old gay man from Cebu City, described another stereotype that he found oppressive: the idea that gay males should be entertainers, jokers, and talented performers. He said classmates and teachers:

…put so much pressure on me that because I’m gay, I should be comedic, I should be funny all the time, I should joke—and I’m not that kind of person, to crack jokes and sing and entertain. In our entertainment industry, gays are usually presented as comic relief. And that’s okay at some point, but that’s it? There’s more to being gay than being funny and entertainers. And because of that, usually our job opportunities are being limited to being a hairdresser, working at a salon, being a comedian. And I’d like to be a researcher or a lawyer. We’re diverse people, like straight people.[151]

When students and teachers reinforce these stereotypes, they put pressure on those who do not fit preconceived notions of being gay and constrain their education and employment options. In an interview with Human Rights Watch, a local government official who had organized a job training program for LGBT people noted that the program specifically trained LGBT people to be clowns and hosts for pageants and other events.[152]

Young lesbian women encounter different stereotypes. Dalisay N., a 20-year-old panromantic woman who had attended high school in Manila, observed that lesbian girls were particularly disadvantaged by teachers because “the lesbian community, they don’t see us like that, like the gays, the creative ones who do something artsy, that gay people are at the top of the list.”[153] Instead, according to Eric Manalastas, “the stereotype with lesbians is that they’re dangerous, a danger to other female students. Not in terms of being violent, but maybe as predatory. Or generally a bad influence—not good for moral development—as though they aren’t also adolescents themselves.”[154] In interviews with Human Rights Watch, young bisexual women recounted how teachers scrutinized girls they considered “butch” or masculine, and took steps to separate them from other girls to prevent them from becoming close.[155]

For youth who are transgender, pressure to “pass” according to their gender identity and, for transgender girls, to achieve high standards of physical beauty, were a serious source of stress for those who felt they lacked the ability or resources to meet the expectations of others.

These stereotypes were among the most consistent themes in interviews with LGBT youth. They illustrate how attitudes and informal practices, even when well-intentioned, can place heavy expectations on LGBT youth and undermine the notion that all youth are deserving of respect and acceptance. They underscore the importance of anti-bullying efforts, information and resources, and antidiscrimination policies that emphasize that all students, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity, have rights that must be respected in schools.

IV. Exclusion from Curricula and Resources

When LGBT students face hostility in their homes, communities, and peer groups, access to affirming information and resources is vitally important. In interviews, however, few LGBT students in the Philippines felt that their schools provided adequate access to information and resources about sexual orientation, gender identity, and being LGBT.

As scholars have noted, heterosexism—or the assumption that heterosexuality is the natural or preferable form of human sexuality—can take two different forms in educational settings: “(1) denigration, including overt discrimination, anti-gay remarks, and other forms of explicit homophobia against gay and lesbian students and teachers, or (2) denial, the presumption that gay and lesbian sexualities and identities simply do not exist and that heterosexual concerns are the only issues worth discussing.”[156] By neglecting or disparaging LGBT youth, both forms of heterosexism, alongside cisnormativity—the assumption that people’s gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth, sometimes accompanied by denigration of transgender identities—are harmful to the rights and well-being of LGBT students in the Philippines.

A recent analysis of issues related to sexual orientation and gender identity in the Philippines found that LGBT youth are often neglected in school environments, particularly in light of strong constitutional protections for academic freedom, which give schools considerable leeway to design curricula and resources.[157] In interviews with Human Rights Watch, LGBT students described how the absence of information and resources proved detrimental to their rights and well-being and why DepEd, lawmakers, and school administrators should embrace inclusive reforms.

School Curricula

Very few of the LGBT students interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they encountered positive portrayals of LGBT people as part of the school curriculum.

In many cases, LGBT people were simply invisible, with no acknowledgment that people are LGBT or discussion of LGBT history, literature, or other issues. One study found that, in elementary school textbooks required by DepEd:

[C]haracters that portray femininity are always women, while men always portray masculinity. There is a clear binary and strict gender attributes and roles between the two genders; and both gender are always portrayed in a ‘fixed’ stereotypical manner…. Hence, with the strict portrayal of women as feminine and continuously at home, while men [are] masculine as the breadwinner, couples, as heterosexuals, are legitimized and naturalized, leaving no room for other forms of sexuality…. These discourses do not leave any room for diverse forms of family, such as single-headed families, families with overseas contract workers, families that are cared for by young or aging people, homosexual couples, to name a few. It only legitimizes the heterosexual couple and renounc[es] other forms.[158]

Students confirmed that discussions of LGBT people in classes where LGBT issues might arise—for example, history, literature, biology, or psychology—are exceedingly rare. As Leah O., a 14-year-old bisexual girl in Marikina, said, “The teachers don’t mention LGBT.”[159] Alex R., a 17-year-old gay boy from San Miguel, similarly noted, “I didn’t hear teachers say anything about LGBT issues in class.”[160]