Summary

For the last 25 years, Israel has imposed increasingly strict restrictions on travel to and from the Gaza Strip. Those restrictions affect nearly every aspect of life in Gaza, including the ability of human rights workers to document violations of human rights and international humanitarian law (IHL) and to advocate for their remediation. While Israel makes exceptions to its travel ban for what it calls humanitarian reasons, as a rule, it does not permit Palestinian, Israeli and foreign staff of human rights organizations to enter or leave Gaza. Israel controls Gaza’s airspace and territorial waters and has prevented the operation of an airport or seaport for the past two decades, rendering Palestinians in Gaza dependent on foreign ports to travel abroad. It also severely restricts all travel between Gaza and the West Bank, recognized as a single territorial unit, even when the transit does not take place via Israeli territory.

Egypt has kept its border crossing with Gaza, Rafah crossing, mostly closed since 2013, opening it every several weeks to allow passage for a few thousand people. It has refused permission for foreign human rights workers to enter Gaza via the Rafah crossing in recent years and has restricted the ability of Palestinian human rights workers to cross. In justifying its restrictions on access via Rafah, Egypt says that Israel, as the occupying power, is responsible for Gaza, and it also cites the security situation in the area of Egypt's Sinai Peninsula bordering Gaza, where an affiliate of the Islamic State has engaged in violent confrontations with the Egyptian military since 2013, killing hundreds. But Egypt began greatly restricting transit through Rafah before the security situation in the Sinai deteriorated and shortly after the military's July 2013 removal of former President Mohamed Morsy, whom the military accused of receiving support from Hamas. While Egypt does not owe obligations to Palestinians under the law of occupation and can, with some important limitations, decide whom to allow to enter its territory, its actions are exacerbating the impact of Israel’s travel restrictions on residents of Gaza.

The Israeli government justifies the restrictions on travel, including travel for human rights workers, on two grounds. First, it says, travel between Gaza and Israel inherently endangers Israeli security, whether the travelers are Palestinians or not, and irrespective of any individualized risk assessment for a particular person. Second, it says, its obligations toward Gaza are limited to allowing passage for exceptional humanitarian circumstances only, and job-related travel for human rights workers does not qualify as exceptionally humanitarian.

Without the ability to get staff, consultants and volunteers into and out of Gaza, Palestinian human rights groups find it difficult to maintain programs across Gaza and the West Bank, which Israel recognized as a single territorial unit, and about which there is international consensus that is it occupied territory.[1] Palestinian human rights workers from Gaza are all but barred from accessing training and professional development opportunities outside Gaza and from meeting with their West Bank-based colleagues. Foreign and Israeli staff of human rights organizations are ordinarily not permitted into Gaza, limiting their ability to identify, research and advocate against human rights and IHL abuses and keeping experts from applying specialized knowledge to the research and documentation of IHL violations, including possible war crimes.

The Hamas authorities in Gaza, for their part, have not taken adequate steps to protect human rights defenders against retaliation for criticizing armed groups in Gaza, and in some cases they have arrested and harassed Palestinians who express criticism of the Hamas regime.

The prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) has opened a preliminary examination into possible serious crimes committed in Palestine, including Gaza, as of June 13, 2014. A key factor the prosecutor will consider in determining whether to open a formal investigation is whether any credible national proceedings exist that would preclude the ICC’s involvement. Under what is known as the principle of complementarity, the ICC is a court of last resort, stepping in only where national authorities are unable or unwilling to conduct genuine domestic proceedings.

In public statements and documents, the Israeli government and military have argued vigorously that the Israeli mechanism for investigating potential war crimes meets international standards and that Israeli officials are actively and genuinely investigating all relevant claims and information regarding potential violations of IHL. The Israeli authorities acknowledge the difficulty of collecting evidence from inside Gaza, where Israel no longer has a permanent ground troop presence, and of receiving complaints and information from witnesses and victims inside Gaza, who fear and distrust the Israeli military. However, they cite, among other means, cooperation with and reliance on human rights and other nongovernmental organizations as an important means of receiving information about potential violations of IHL and obtaining the cooperation of Palestinian witnesses. Yet the restrictions that the Israeli military imposes on access for human rights workers make it more difficult for human rights workers to document potential violations. These restrictions hamper what is, by the Israeli government’s own acknowledgement, a significant source of information and evidence about potential IHL violations, raising questions not just about the capability of the Israeli authorities to investigate potential violations of the laws of war but also their willingness to do so.

Israel’s restrictions on access to and from Gaza go far beyond what is permitted by international humanitarian law and human rights law. Because Israel continues to exercise control over significant aspects of life in Gaza, it continues to have obligations under the law of occupation in the areas in which it continues to exercise control – primarily to allow the movement of people and goods. While the law of occupation allows Israel to restrict travel for imperative reasons of security, the generalized travel ban it imposes is vastly disproportionate to any concrete security threat. Israel is also required, under the law of occupation as codified in Article 43 of the Hague Regulations,[2] to permit the proper functioning of civil society, including human rights organizations and activity. The ban also runs afoul of Israel’s obligations to respect the human rights of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, including their right to freedom of movement, which includes, with some limitations, a right to enter and leave one’s country and to choose one’s place of residence within it.

Israel should bring its policy on access to Gaza into conformity with its obligations under IHL and human rights law. It should do so by facilitating access to and from Gaza for all Palestinians, subject to individualized security screenings and inspections. In particular, it should facilitate access for Palestinian human rights workers, whose activities are an essential part of a properly functioning society and who are part of a civil society that, by the Israeli government’s own admission, plays an important role in documenting and advocating against potential war crimes and violations of IHL. Israel should also strongly consider permitting access to Gaza for foreign human rights workers, who contribute to the proper functioning of normal civilian life by providing assistance to local human rights groups, strengthening civil society, and helping to protect victims. The work of such organizations defending human rights has been recognized as worthy of protection by the United Nations General Assembly.

Human Rights Watch also recommends that the International Criminal Court open a formal investigation into the situation in Palestine in order to ensure accountability for any potential serious crimes committed in Palestine since June 2014. It recommends that the Hamas authorities in Gaza take steps to protect human rights activists and allow them to document violations by all sides, including by Hamas and armed Palestinian groups inside Gaza.

Egypt also should consider the impact of its closure of the border with Gaza on the rights of Palestinians living there, as well as its obligations to uphold the Fourth Geneva Convention, which provides protections for people living under occupation.

Recommendations

To the Israeli Defense Ministry and Interior Ministry

- End the generalized ban on travel to and from Gaza, and permit the free movement of people to and from Gaza, subject to individual security screenings and physical inspection. Such screenings should take place in a transparent, non-arbitrary manner, should give individuals an opportunity to challenge refusals directly before the Israeli authorities, and should balance measures to protect against specific, concrete security threats with Israel’s obligations toward Palestinians living in Gaza.

- Until the travel ban is lifted, add human rights workers to the categories of Palestinians permitted to travel between Gaza, Israel and the West Bank and to travel abroad from Gaza in order to access work meetings, trainings, conferences, and other professional development opportunities, including rest and relaxation breaks.

- Allow foreign and Israeli human rights organizations to send personnel, consultants, volunteers and experts into Gaza in order to engage in work-related documentation, training, research, and advocacy.

- Facilitate access to ports for travel abroad. Until Palestinians are permitted to reopen and reestablish their airport and open a seaport, allow Palestinians to use Israeli ports for travel.

To the International Criminal Court’s Office of the Prosecutor

- In evaluating the credibility of Israel’s domestic investigations, take into consideration Israel's policy on travel for human rights workers, including the effect of the travel restrictions on the quality and extent of the information that reaches Israeli military authorities and how this may reflect on the ability and willingness of the authorities to conduct genuine proceedings.

- Raise concerns with Israeli authorities about their policy toward the movement into and out of Gaza for human rights workers.

To the Hamas Authorities in Gaza

- Protect human rights workers in Gaza from all threats of retaliation or harm, physical or otherwise, stemming from their research and advocacy regarding human rights and IHL violations, including abuses by armed groups in Gaza.

- Refrain from arresting, censoring or otherwise taking action against people in Gaza who peacefully document human rights and IHL violations and express criticism of the government, including human rights activists, journalists, and others.

- Conduct genuine investigations into alleged serious crimes committed by armed Palestinian groups in Gaza during the 2014 war.

To Egypt

- Like all parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention, Egypt should do everything within its power to ensure the universal application of the Convention’s humanitarian provisions, including protections for civilians living under occupation.. Egypt should also allow access for United Nations Human Rights investigators and consider the impact of its border closure on the rights of Palestinians to travel to and from Gaza.

Methodology

This report examines Israel’s policy on allowing access into and out of Gaza for staff members, consultants, volunteers and other personnel working with Palestinian, Israeli, and foreign human rights organizations. It also examines the impact of that policy on the ability of the Israeli authorities to investigate adequately violations of IHL that allegedly occurred in Gaza or are otherwise related to the conduct of hostilities between the Israeli military and armed Palestinian groups in Gaza.

A Human Rights Watch researcher and two Human Rights Watch research assistants conducted 12 interviews with representatives of four Palestinian human rights organizations based in Gaza, two foreign human rights organizations, and one Israeli human rights organization. Four of these organizations play a prominent role in documenting abuses stemming from the conduct of hostilities between Israel and Palestinian armed groups in Gaza.

We also reviewed documents published by the Israeli Defense Ministry outlining the criteria for entering and leaving Gaza, court documents in which the Israeli authorities explained their policy regarding access for Gaza and its rationale, written responses to individual requests to travel to and from Gaza, and public statements, written and oral, made by the Israeli authorities regarding their mechanisms for investigating violations of IHL by Israeli armed forces and the nature of their relationship with human rights organizations.

We reviewed publications by these human rights organizations, including a 2016 report on the effect of the travel restrictions on civil society organizations and reports issued by human rights groups on the conduct of hostilities during the summer of 2014. Human Rights Watch wrote to the Israeli military attorney general (MAG) seeking comment and received a letter in response, the full text of which is included in the annex to this report.

In the course of researching this report, Human Rights Watch repeatedly requested permission for its foreign staff members to enter Gaza. The Israeli authorities refused most of those requests, but they approved the last request on an exceptional basis, as will be described in the report, and two representatives of Human Rights Watch visited Gaza in September 2016.

All interviewees freely consented to be interviewed. Human Rights Watch explained to them the purpose of the interview and how the information gathered would be used, and did not offer any remuneration.

I. Closure of Gaza

The Gaza Strip, the West Bank and Israel, together make up the land that was mandatory Palestine, governed by the UK, in the post-World War I era. The cultural, political, economic, social and familial ties between these areas run deep, and for most of the modern era there was freedom of movement across the region. The 1948 Arab-Israeli War divided these areas, leaving Gaza under Egyptian military occupation, the West Bank under Jordanian rule, and Israel as a sovereign state. Palestinian refugees from what became Israel fled or were expelled to Gaza, and today 72 percent of Gaza’s 1.8 million residents are refugees or their descendants.[3] The Israeli capture of Gaza and the West Bank in 1967 led to all the areas coming under the control of Israel, with Israel establishing two military governments to rule Gaza and the West Bank.

For the first two decades of the Israeli occupation, Palestinians were mostly permitted to travel between Israel, Gaza and the West Bank, effectively rejuvenating the historical ties that had been interrupted in 1948. While the Israeli military declared Gaza and the West Bank to be closed military zones, it issued a series of “general exit permits” mostly allowing Palestinians to travel without need of an individualized permit, unless individually prohibited.[4]

In 1991, during the first Intifada or Palestinian uprising and against the backdrop of the first Gulf War in which Iraq bombed Israel, the Israeli military canceled the general exit permit that had been in place and gradually began to require Palestinians to obtain individual permits to travel. Although the 1995 Oslo Peace Accords recognized Gaza and the West Bank as a “single territorial unit,” during the 1990s it became increasingly difficult to travel between the two areas, and in 1995 Israel built a fence along its border with Gaza.[5] With some ebbs and flows, between 1991 and 2005, travel into and out of Gaza became increasingly restricted.[6] The restrictions coincided with escalations of violence, including armed clashes between armed groups in Gaza and the Israeli military, attacks on the crossings between Gaza and Israel, and bombings targeting Israeli civilians inside Israel and the Gaza Strip.

For most of that time period, the Israeli military, which controlled access between Gaza and the outside world, justified the travel restrictions by citing security concerns or military necessity. The restrictions included both individual travel bans, based on assessments by the Israel Security Agency (ISA or Shin Bet), and generalized restrictions, such as closing crossings, blocking entire categories of people from traveling, or limiting travel to humanitarian cases.[7]

In 2005, Israel removed the civilian settlements it had established in the Gaza Strip, ended its permanent ground troop presence there, and withdrew from the Gaza-Egypt border. At that time, the rationale for imposing travel restrictions began to shift. Israel claimed that it no longer occupied the Gaza Strip and that it therefore no longer owed obligations to Palestinian residents of Gaza under the law of occupation, including a duty to permit travel.[8] In September 2007, following the collapse of a Palestinian national unity government and the takeover of internal control of Gaza by the Hamas movement, the Israeli government issued a cabinet decision announcing restrictions on the movement of people and goods into and out of Gaza, including in order to weaken the economy in Gaza, which the government declared to be a “hostile territory.”[9]

The Israeli government calls its policy restricting access into and out of Gaza “the separation policy,” which it says serves both security and political goals.[10] It says it wants to restrict travel between Gaza and the West Bank to a minimum in order to avoid transferring “a human terrorist network” from Gaza to the West Bank,[11] the latter of which has a porous border with Israel and is home to a half million Israeli settlers. Today, access into and out of Gaza for Palestinians is limited to “exceptional humanitarian circumstances, with an emphasis on urgent medical cases,”[12] although Israel also considers hundreds of senior merchants and others eligible to travel.

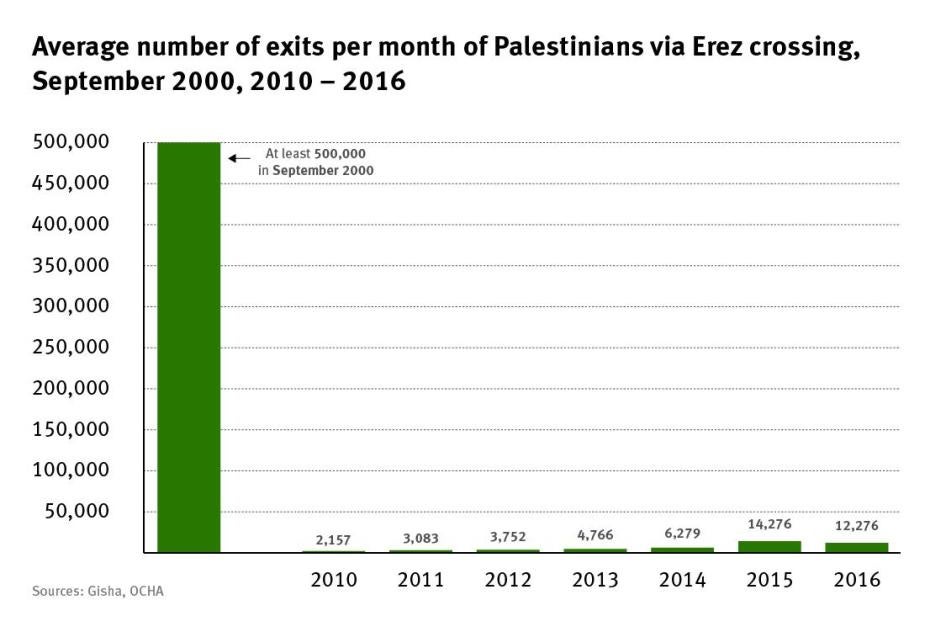

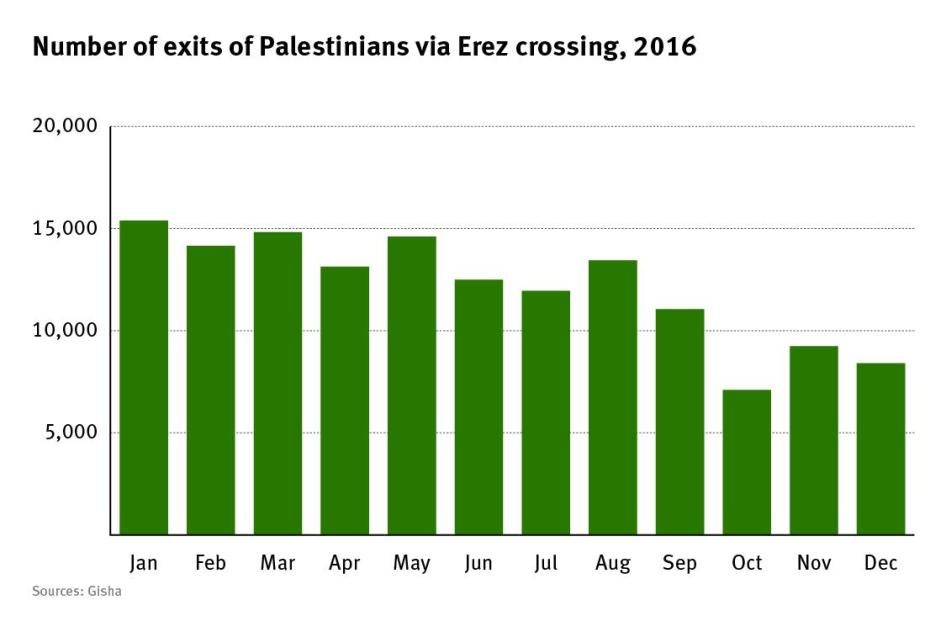

In 2016, there were on average 12,150 crossings per month of Palestinians from Gaza entering Israel and the West Bank,[13] compared with more than half a million crossings in September 2000, on the eve of the outbreak of the second Intifada or Palestinian uprising.[14] The number of crossings is much higher than the number of people who travel because some travelers, especially merchants, travel multiple times per month. Access for Palestinians between Gaza, Israel and the West Bank is barely more than 2 percent of what it was in September 2000, and most of Gaza’s nearly 2 million residents are not permitted to travel.

Also in 2016, an average of 700 representatives of international organizations, primarily humanitarian aid workers, traveled between Gaza and Israel and the West Bank each month. There is additional travel by foreigners (people listed on neither the Palestinian nor the Israeli population registry) between Gaza and Israel and the West Bank each month via the Erez passenger crossing, including journalists, diplomats and those traveling to visit immediate family members in cases of death, grave illness, or weddings.[15] Still, access via the Erez crossing has risen from what appears to be an all-time low in 2008, a year in which the criteria were particularly restrictive. That year, there were only about 2,000 crossings per month of Palestinians from Gaza to Israel, mostly medical patients and their companions, diplomats, and humanitarian aid workers.[16]

These restrictions have devastated the economy in Gaza,[17] separated families,[18] blocked access to medical care[19] and educational opportunities,[20] thwarted reconstruction,[21] and deepened the split between Gaza and the West Bank, a rupture exacerbated by the 2007 Palestinian factional split that left Fatah governing the West Bank and Hamas governing Gaza.

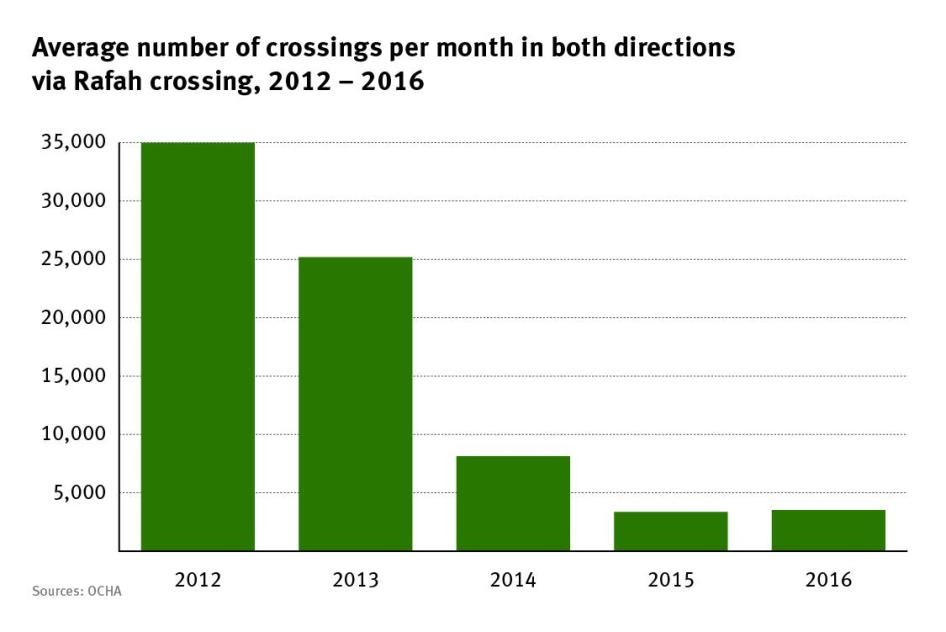

Israel withdrew from the Rafah border crossing between Gaza and Egypt in 2005, leaving Egypt and Hamas in control of their respective sides. Egypt has kept the Rafah crossing mostly closed since the 2013 overthrow of President Mohamed Morsy, reflecting strained relations between the new Egyptian government and the Hamas government in Gaza, which is affiliated with Morsy’s Muslim Brotherhood party. On the rare days that the Rafah crossing opens, once every several weeks, access is limited to the few thousand people who can cross before it closes. Priorities are determined by the Hamas government and the Egyptian authorities. In 2016, there were 3,520 crossings per month of Palestinians between Egypt and Gaza in both directions, compared with a monthly average of 34,991 in 2012.[22] In other words, access for Palestinians between Gaza and Egypt is just ten percent of what it was in 2012, and the Rafah crossing is closed most of the time. Egypt had been the gateway to travel abroad for Palestinians in Gaza but is now mostly closed off to them.

Israel controls Gaza’s airspace and territorial waters and, citing security concerns, permits no air or sea travel to or from there.[23]

For all these reasons, travel via the Erez crossing is the primary route for travel between Gaza, Israel, the West Bank, and foreign countries.

II. Access for Human Rights Workers

The umbrella organization PNGO, whose membership includes only some of Palestine’s civil society groups, lists 135 nongovernmental organizations working in fields such as development, culture, education, environment, and human rights.[24] Dozens of Palestinian human rights organizations are either based in Gaza or conduct activities in Gaza. Among these are human rights organizations that research and report on violations of IHL or the laws of war, including during escalations of violence between Israel and armed Palestinian groups in Gaza. In addition, at least two Israeli human rights organizations conduct research in Gaza through permanent field researchers who live there, and foreign human rights organizations either employ permanent staff members or periodically conduct research in Gaza. Human Rights Watch has employed a permanent research assistant in Gaza since 2009.

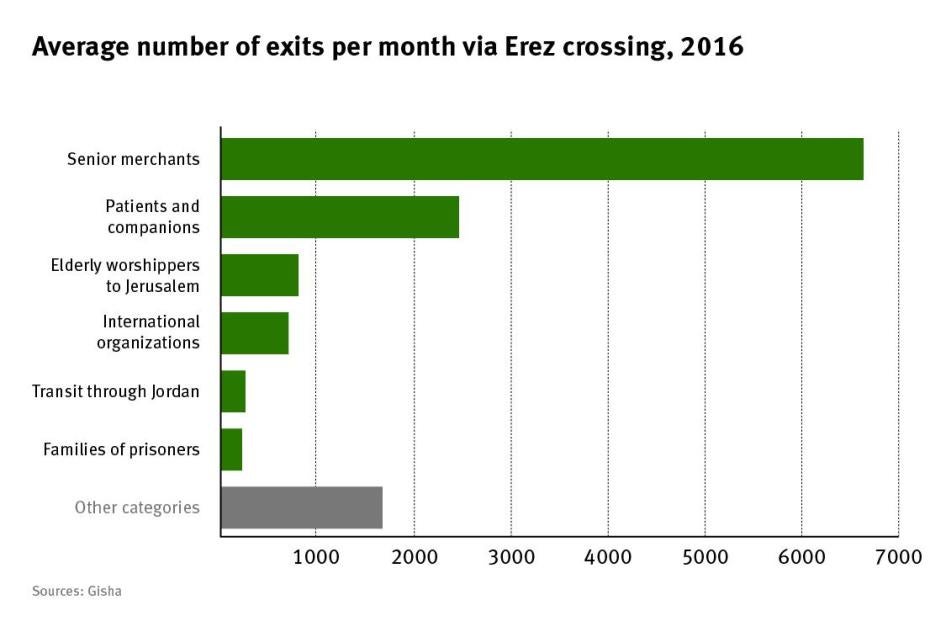

Israeli Policy on Travel

The Israeli military considers both Gaza and the West Bank to be under a “closure,” meaning the default rule is that Palestinians may not travel into Israel or between Gaza and the West Bank unless they qualify for enumerated exceptions that change periodically. Following extensive litigation under Israel’s Freedom of Information Act,[25] the Israeli Defense Ministry now publishes its criteria for travel between Gaza, the West Bank and Israel, called “permissions in the closure.”[26] The criteria permit travel for patients seeking medical care outside Gaza and their companions, “senior merchants” purchasing goods from Israel or the West Bank, family visits for immediate family in cases of death, grave illness or weddings, elderly worshippers traveling to Jerusalem, visits to relatives incarcerated in Israel,[27] and others. Senior merchants make up the largest category of Palestinians entering Israel, accounting for 54 percent of all crossings by Palestinians, with medical patients accounting for 21 percent. [28] The third largest category of people crossing are employees of international organizations, who constitute nearly 5 percent of all crossings by Palestinians into Israel from Gaza, more than 700 per month.[29] This last category includes Palestinian employees or contractors of diplomatic representations or international aid organizations registered with the Israeli ministries of Social Welfare, Foreign Affairs, or Interior.[30]

Belonging to one of these approved categories qualifies an individual to apply for a travel permit but does not guarantee they will receive one. Access in some categories is subject to quotas, and access for all travelers is subject to a security screening by the ISA. Such screenings are nontransparent, and when the ISA objects to granting a permit, little or no information about the nature of the security allegations are available to the applicant or their legal representative.

Human rights workers – Palestinian, Israeli or foreign – are not included in the categories of people eligible to travel through the Erez crossing. When Palestinian, Israeli or foreign human rights organizations request access for staff, visitors or volunteers, the Israeli government systematically refuses. In some cases, the Israeli military claimed that it would not allow travel for employees of human rights organizations because those organizations have not registered with the Israeli authorities as international organizations.[31] Yet registration appears limited to diplomatic representations such as foreign embassies or the United Nations and “international aid organizations providing assistance to the Palestinian territories.”[32] No publicly available procedure has been established for allowing human rights organizations to register. Since 2013, the Israeli human rights group Gisha has asked multiple government agencies for information regarding the supposed ability of international organizations, other than aid organizations and diplomats, to register for purposes of requesting travel permits, but no government agency has taken responsibility for such registration, and a procedure to request recognition does not appear to exist.[33]

In a failed court challenge of that policy, brought by the Israeli human rights groups B’Tselem and Gisha when they sought permission for B’Tselem’s field researchers from Gaza to attend meetings and trainings in Jerusalem, the Israeli authorities explained the distinction they draw between humanitarian organizations and human rights organizations for purposes of travel into and out of Gaza:

As far as recognized international organizations are concerned, we are talking about organizations such as the International Red Cross, the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Refugee Works Agency (UNRWA), the United Nations Development Corporation (UNDP), and the like, which work in the Gaza Strip and Judea and Samaria for the purpose of humanitarian assistance to residents of the Strip, including in areas such as welfare, education, health, etc.…[34]

The policy, according to the Israeli government, promotes the foreign policy interests of the State of Israel by allowing passage for employees of certain international organizations and diplomatic representatives and workers whose passage is needed to fulfil Israel’s commitment “not to harm the humanitarian minimum that residents of the Strip need – including giving travel permits in appropriate humanitarian circumstances.”[35]

The standard reply to travel requests from human rights organizations is that travel to and from Gaza is limited to exceptional humanitarian circumstances, and that travel to facilitate human rights work does not meet those criteria.[36] As noted, the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem has repeatedly failed to get permission for its field researchers to leave Gaza for meetings with the rest of the staff in Jerusalem.[37] The Gaza-based Palestinian human rights groups the Palestinian Center for Human Rights (PCHR) and al-Mezan Center for Human Rights continue to request permits for their staff members invited to workshops, trainings, meetings and conferences, but they routinely and repeatedly receive refusals.[38]

While the explanation differs slightly, the Israeli military also refuses to allow foreign human rights workers living in Israel or visiting it to enter Gaza at least since 2012. Amnesty International, a leading human rights group based in London that has documented human rights and IHL violations in Gaza since the 1980’s, has tried for the last four years to get its staff into Gaza. The last time Israel granted permission was June 2012. When hostilities between Israel and armed Palestinian groups in Gaza erupted in November 2012, the Israeli military authorities refused or failed to respond to multiple requests from Amnesty International to enter both during and after the fighting. Amnesty International was able to get its staff into Gaza in 2012 via the Egyptian border, which was open at that time. By the next period of hostilities in July and August 2014, the Egyptian border had closed. Amnesty International submitted four separate requests to the Israeli authorities during the fighting, but the authorities refused. Immediately following the hostilities, Amnesty International appealed the refusal through an ombudsman branch of the Israeli military, also with no success. [39]

In July 2015, a lawyer acting on behalf of Amnesty International requested access for the group’s foreign staff. In September 2015, the Israeli military refused the request. [40]

Separately, Amnesty International approached the Israeli Foreign Ministry and the Israeli Ministry of Social Affairs to try to register as an international organization in order to obtain access to Gaza, but officials told Amnesty International that it does not fit the criteria for registration.[41]

Human Rights Watch has also repeatedly tried to get its staff into Gaza, but beginning in 2009 the Israeli military authorities refused or failed to answer requests. During and immediately after the 2014 hostilities, Human Rights Watch made multiple unsuccessful requests to enter Gaza via the Erez crossing. In one response, the Israeli military authorities said they only accept requests from organizations registered with the Ministry of Welfare (limited to international aid organizations) or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (limited to diplomats) and referred Human Rights Watch to another branch of the military.[42] That department refused the request, saying that it only approved entry for doctors and medical staff.[43] The authorities made an exception in September 2016, after seven years of refusals, and allowed two foreign staff members of Human Rights Watch to enter Gaza, after they requested permission to do so in order to advocate on behalf of Israeli civilians held by armed Palestinian groups in Gaza. The authorities categorized that positive response as a one-time exception, falling outside the criteria established by military policy.[44]

As of 2013, the Egyptian authorities have also refused to allow foreign human rights workers to enter Gaza during one of the infrequent openings of the Rafah border crossing, effectively closing Gaza off from the global staff of these human rights organizations and external experts invited by local groups. Neither Human Rights Watch nor Amnesty International was able to get foreign staff into Gaza during or immediately after the 2014 hostilities. In justifying its restrictions on access via Rafah, Egypt says that assuring access to and from Gaza is the responsibility of Israel, which is an occupying power in Gaza, and it also cites the security situation in the Sinai Desert, the area in Egypt bordering Gaza where armed groups engage in violent confrontations with Egyptian security forces.[45] Yet at other points in time, Egypt has managed to keep Rafah open, despite the activities of armed groups in Sinai.

In a recent letter to Human Rights Watch, the Israeli military explained why it does not permit foreign staff of human rights organizations to enter Gaza from Israel:

Exit by foreigners, lawfully present in Israel, from Israel into the Gaza Strip and their subsequent return to Israel raise the inherent risk associated with unmonitored travel between the Gaza Strip and Israel. This is partly the reason why it has been decided that exit from Israel into the Gaza Strip by foreign nationals will be permitted in humanitarian cases only and subject to the policy in effect at the time.[46]

On the one hand, the Israeli authorities interpret the criterion “humanitarian” in a narrow way, to include humanitarian circumstances personal to an applicant, such as illness or mourning the death of a family member, but to exclude human rights workers conducting work with clear humanitarian implications, such as training in rehabilitating torture victims[47] or security training to protect a staff member.[48] On the other hand, within those same narrow criteria, Israel permits nearly 7,000 crossings by merchants each month for the purpose of buying goods and 700 crossings monthly by representatives of international organizations, where, especially in the case of the merchants, one person might make multiple crossings each month.[49]

ISA Security Screenings

All requests to travel via the Erez crossing are subject to security screenings by the ISA or Shin Bet, as it is commonly known. In some cases, the military authorities reject requests to travel based on an individualized assessment that travel by a particular person poses a security risk. Human rights groups have criticized the lack of transparency and apparent arbitrariness of the screening process.[50]

The policy described above, however, is a test that is applied to permit requests even before a person is screened by the ISA. In other words, the Israeli military first determines whether a person meets the eligibility requirement to request a permit, and only if the request meets the criteria do the military authorities consider an ISA evaluation. The refusals addressed in this report refer to refusals based on the first test: i.e. whether a person meets the criteria for travel. In some cases, human rights workers have been allowed to travel via Erez for a reason unrelated to their work in human rights organizations, meaning they have cleared the ISA screening, but when those same people request a work-related permit the military authorities refuse.[51]

Impact on Human Rights Work

The restrictions on travel make it more difficult for human rights organizations – Palestinian, Israeli and foreign – to do their work documenting human rights and IHL violations and advocating against them. The Israeli human rights group Gisha documented some of these difficulties in an extensive study on the effects of the travel restrictions on 32 civil society organizations in Gaza and the West Bank, including human rights groups.[52] By conducting interviews and focus groups, Gisha found that the inability to travel blocked access to training, impeded intra-organizational and inter-organizational working relationships and collaboration, contributed to waste and duplication of resources, made it harder to get funding, cut off access to stress-management and stress-relief opportunities, and made it more difficult for young civil society leaders to emerge and advance.

These obstacles have a direct effect on the work of human rights organizations documenting violations of the laws of war, including possible war crimes, and advocating for their remediation.

Palestinian Human Rights Workers in Gaza Isolated

Palestinian human rights workers living in Gaza find it very difficult to participate in trainings, conferences, workshops or meetings held outside Gaza, whether in the West Bank, Israel, or abroad. For Gaza-based employees of groups based in the West Bank, Israel or foreign countries, the lack of actual contact with colleagues and supervisors highlights a sense of isolation and makes it more difficult to develop and sustain the kind of working relationships that maximize productivity and creativity. Kareem Jubran, director of field research at the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem, supervises three field researchers working in the Gaza Strip. He was last able to meet two of them in 2012, when the Rafah crossing with Egypt was still open, and they traveled from Gaza to Egypt to Jordan to meet him and other staff members of the Jerusalem-based group:

The problem is with training … I’m always trying to explain things over the telephone. When we talk about the work plan, it takes time to discuss and persuade regarding what our needs are there, what we want. If I could give them more tools, research ability, theoretical knowledge regarding international law, it would help us a lot more. We are always trying to get them to trainings in Gaza, but it’s not the same as a program you build yourself. There’s also the emotional strain on them, the danger and the mental difficulty. A person like that needs to feel as if he’s part of a larger team. And he doesn’t have that feeling when he’s working in the field alone … they don’t know the staff, there are no human faces, and that affects the professional relationships … I felt that when I met them in Amman. After three years of telephone contact, I had developed a stereotype in my head of who they were. And then I discovered that their personalities were different. And from then on, it was easier to supervise them, to understand them, to know their sensitivities. It’s important for a long-term work relationship.[53]

Human rights workers in Gaza report feeling cut off from others in their field and unable to communicate their perspectives at gatherings and conferences. Fadel Mezni is a researcher at the Palestinian Center for Human Rights (PCHR). “There is no exchange or updates of ideas and principles,” he said. “The Gaza representation – their voice is silenced. In addition to the personal cost of not developing professional skills, that is the deeper, wider cost.”[54]

PCHR’s deputy director, Jaber Wishah, said that the inability to get staff out of Gaza meant that his organization could not bring its findings to international fora but rather had to rely on colleague organizations to represent its work. Advocacy is also difficult to plan, he said, because the group does not know if or when it can get staff outside, and when staff members get stuck outside Gaza waiting for the Rafah crossing to reopen, the cost of an extended stay strains the organizational budget.[55]

Bahjat al-Helou is the training coordinator at the Gaza office of the Independent Commission for Human Rights, a statutorily-created commission that monitors human rights compliance by the Palestinian authorities. Its headquarters is in the West Bank. He said organizational planning was difficult across the two branches without the ability to meet face to face:

I wouldn’t say the quality of our work product is lowered. We work passionately and tirelessly. But it affects the impact of our reporting and fact-finding missions. We cannot present our work. Something is lost when the person from Gaza is relying on West Bank colleagues to present and run advocacy campaigns on our behalf.[56]

Second, the travel restrictions mean that outside experts and human rights workers cannot get into Gaza, including for training or volunteer work. Wishah of PCHR said that even when he has been able to secure funding for external experts to train staff, that training has mostly taken place via teleconference, due to the inability to obtain permits. For similar reasons, PCHR has difficulty getting foreign interns and volunteers, and they often have to work out of a small PCHR satellite office in the West Bank.[57]

During and after escalations of violence, especially, the inability to get external experts or even UN investigators and human rights experts into Gaza makes it difficult to conduct documentation and reporting on potential violations of IHL. During the large-scale military operation in July and August of 2014, the Israeli authorities refused repeated requests by the global human rights organizations Amnesty International[58] and Human Rights Watch to send specially-trained emergencies researchers and weapons experts into Gaza. It also refused entry to a commission of inquiry established by the United Nations Human Rights Council to investigate potential crimes committed during the 2014 fighting.[59] While researchers at Palestinian human rights groups inside Gaza have experience in documenting the conduct of hostilities, they do not have specialized weapons training and so rely on the engineering unit of the Palestinian police to analyze shrapnel and other remains in order to determine which weapons were used and how. In 2012, external weapons experts were able to enter Gaza via Rafah to support local human rights groups, but in 2014, no external experts were able to get in.

“It would have been helpful to have external weapons experts enter Gaza” in 2014, Samir Zaqout, field research unit coordinator at the Palestinian human rights group Al-Mezan, said.[60]

Foreign Human Rights Groups Shut Out

The inability to get foreigners into Gaza is also problematic for international human rights organizations based abroad, even if they employ research assistants who are residents of Gaza.

The last time that Amnesty International was able to get staff members into Gaza was in 2012. In the summer of 2012, Israel granted permission for a delegation from Amnesty International to enter Gaza via the Erez crossing for a research project related to detention practices by the Gaza authorities. In November 2012, during the large-scale military operation, a delegation of two researchers and a weapons expert seeking to document IHL violations stemming from the conflict were not permitted to enter through Israel but reached Gaza via the Rafah crossing, which was open at that time. By 2014, however, Rafah had closed, and Israel rejected multiple requests to allow emergencies researchers and weapons and medical experts into Gaza from Israel.[61] Instead, Amnesty International worked with two local researchers hired temporarily. The external team was not even able to get safety equipment, including helmets and flak jackets, to the local researchers. Saleh Hijazi, one of the researchers responsible for Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory who was based in the UK at the time, said that without the ability to work directly with staff on the ground, he felt like he was “managing the field researcher more than focusing on the research itself ... the questions weren’t necessarily what we needed. The photographs as well were sometimes meaningless.” He said the biggest problem was the lack of military and medical experts who could examine evidence first-hand. “It’s a major loss not having these experts on the ground,” Hijazi said.[62]

The Amnesty International research team directed the local researchers by phone and Internet, and much time was spent uploading photos to be sent for analysis and sending researchers back to the field to bring supplementary information. Hijazi said that Amnesty International would have been able to do more research, and more quickly, had the team of experts been able to reach Gaza during the war and immediately afterward.

Human Rights Watch experienced similar difficulties during the 2014 war.[63] With the exception of a one-time entry in September 2016, it was last able to get foreign staff members into Gaza via Israel in 2008. Thereafter, with one exception, the Israeli authorities refused or failed to respond to repeated requests to enter Gaza throughout the years. Until 2012, Human Rights Watch was able to get into Gaza via Egypt, but after Egypt closed the Rafah crossing to regular traffic in 2013, the Egyptian authorities also refused Human Rights Watch’s requests to enter Gaza, citing security. In 2014, the emergencies researcher, weapons expert and Israel and Palestine researcher directed the work of a consultant and a research assistant in Gaza via telephone and Internet communication. Communications with the staff on the ground were unreliable and slow. The consultant and research assistant would send photos and sketch the damage from the bombings for the weapons expert to review remotely, at best an imperfect solution.

Bill van Esveld was the Israel and Palestine researcher at the time for Human Rights Watch who directed the work of the consultant and research assistant from inside Israel:

There were a number of cases in which we needed more but we couldn’t go back, and so we dropped the cases … It’s not that we stopped reporting on them because we didn’t think there was a violation [of IHL], we stopped reporting on them because we couldn’t get the information we needed with the people on the ground that we had … It’s extraordinarily frustrating and demoralizing. Your job is to be in a place as an independent monitor. And you’re blinded. You’re not allowed to be in place, so you’re operating by remote control.

For Human Rights Watch, part of the benefit of having staff on the ground with extensive experience in conflict situations is the ability to make strategic decisions on the kind of research to make a priority, including distinguishing between IHL violations that are aberrations and violations that appear to be part of a policy. The lost time in communicating with local researchers and the lack of direct access to sites and victims limited the kind of research that Human Rights Watch could do.

In particular, not having foreign staff on the ground made it difficult to research issues that could put local staff at risk, such as IHL violations by armed Palestinian groups in Gaza. Hijazi of Amnesty International said that he was cautious to ask local staff to research violations by officials or armed groups inside Gaza that are considered sensitive, out of concern that they might be subject to retaliation. It was easier to do that kind of documentation, he said, with a foreign staff member who can travel in and out of Gaza and therefore be removed for safety reasons if necessary. Human Rights Watch has similar safety concerns and would also be better equipped to research potential IHL violations by armed groups or the Gaza authorities if its non-national staff were able to travel freely to and from Gaza. Human Rights Watch has documented arrests, harassment and torture of Palestinians in Gaza perceived to have gone too far in their criticism of the Hamas government.[64]

Representatives of the Palestinian human rights groups al-Mezan and PCHR said that although it was sensitive for residents of Gaza to report on IHL and human rights violations by armed groups or Hamas, their groups had the clout and protection to be able to do so. During the 2014 military operation, PCHR published a statement condemning Hamas for the summary executions, many of which were captured in television footage, of at least 23 men accused of collaborating with Israel.[65] A UN Commission of Inquiry[66], whose staff was not able to reach Gaza, raised concerns about additional IHL violations by armed Palestinian groups in Gaza, including deliberate and indiscriminate firing on Israeli civilians, putting Palestinian civilians at risk by firing from populated areas inside Gaza and storing weapons in civilian structures including schools.[67] None of the human rights groups based in Gaza published research on these issues, however, or on any other alleged Palestinian IHL violation, other than the summary executions.

Indeed, in the past, Palestinians in Gaza who have criticized the government or armed groups on issues considered to be sensitive have faced retaliation. In 2012, the director of international relations at al-Mezan published an opinion piece criticizing the government and armed groups in Gaza for putting civilians at risk, including by storing weapons in civilian areas.[68] Following the publication, unidentified assailants attacked him twice;[69] the Gaza authorities made no arrests in the case. That incident is far from isolated. Human Rights Watch has documented arrests and physical abuse of journalists and activists who have criticized the Hamas government, directly or indirectly,[70] and foreign journalists have complained about attempts by the Hamas government to censor their reporting, including during wartime.[71]

III. Role of Human Rights Groups in Israeli Investigations

While the Israeli authorities limit the ability of human rights groups to conduct their work in Gaza, they nonetheless cite cooperation with human rights groups as an important element of their mechanism for investigating potential violations of the laws of war.

Palestine acceded to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court in January 2015 and gave the court a retroactive mandate to June 13, 2014, a period that includes the 2014 military operation in Gaza. The ICC prosecutor is currently conducting a preliminary examination into the situation. The Office of the Prosecutor’s ongoing inquiry includes analyzing whether national authorities are genuinely carrying out credible investigations and, if appropriate, prosecutions in relation to potential cases being considered for investigation by the court.

While the Israeli government has declined to cooperate with UN commissions of inquiry that have examined successive rounds of fighting in Gaza, and Israel has not acceded to the ICC treaty, it has issued a number of public statements that address the nature and adequacy of its domestic mechanisms for investigating and prosecuting IHL violations, including war crimes.

Cooperation Between Human Rights Groups and the Israeli Government

The View of the Israeli Government

In describing its mechanism for investigating and prosecuting IHL violations and other misconduct by soldiers and police, the Israeli authorities emphasize that human rights organizations help them to overcome a number of obstacles they face in learning about and investigating alleged IHL violations in the Gaza Strip. The Israeli military attorney general, who is responsible for investigating and prosecuting IHL violations among Israeli soldiers, notes that its investigations of violations that allegedly took place in Gaza are difficult because Israel no longer has a permanent ground troop presence there and cannot easily access physical evidence or witnesses:

First, the arena in which the crime was (allegedly) committed is – usually – outside the territory of the State of Israel, and in many cases in an area controlled by an enemy nation (south Lebanon) or hostile entities (the Gaza Strip). This fact significantly limits, and sometimes even completely thwarts, the ability of the investigators to visit the area and collect physical evidence found there … in addition, there are potential witnesses who hesitate to cooperate with the investigation because it is conducted by IDF officials, and there are others who refrain from providing relevant information about the activities of terrorist organizations in the area where the incident took place, out of fear of retribution.[72]

In a position paper submitted to the Turkel Commission, an Israeli governmental inquiry that examined, among other things, the adequacy of the Israeli investigatory mechanism, then-Military Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit wrote:

Throughout the years, the military investigatory police have adopted various techniques that allow investigators to overcome many of the difficulties. Thus, there is a close relationship between the military investigatory police and human rights organizations representing Palestinian complainants, and through them, these complainants and additional witnesses are summoned to give their version of events. Assistance from human rights groups allows the investigators to overcome the fear of Palestinian residents from a meeting with IDF officials [emphasis in original].[73]

According to the Military Advocate General’s office, the Israeli military receives information about possible IHL violations via individual complainants and human rights groups representing these individuals, as well as media and other reports of incidents.[74]

Indeed, following the 2014 military escalation, the Israeli Foreign Ministry issued a report on Israel’s investigative mechanisms that emphasized the importance of an “active community of domestic and international non-governmental organizations, which are a source of many of the allegations of misconduct."[75] The Foreign Ministry further noted that NGOs assist witnesses and victims in submitting complaints and providing more information to military investigators, and that human rights organizations act as a check on military decisions, appealing decisions to close investigations before the Israeli civilian authorities and Israeli courts.[76]

The View of Human Rights Groups

The Israeli, Palestinian and foreign human rights organizations cited by the Israeli authorities have been publicly critical of the Israeli investigative mechanisms, and one of them, the Israeli organization B’Tselem, has announced that it will no longer cooperate with the Israeli military investigations, calling them a “whitewash.”[77] Other groups continue to file complaints before the Israeli military authorities and even to facilitate witness testimony and supplementary information. The Palestinian human rights organizations al-Mezan and PCHR, working as part of a coalition to document alleged IHL violations in 2014, submitted 354 complaints to the Israeli military authorities.[78]

At the request of the military authorities, these groups provided additional information in more than a hundred cases. Al-Mezan facilitated witness testimony at the Erez crossing in nine cases, and in four other cases, the witnesses declined to meet the military authorities, citing fear and concern about the psycho-social effects of revisiting the trauma through testimony.[79] These groups are highly critical of the Israeli investigation mechanisms and have called for the International Criminal Court prosecutor to investigate the situation.[80] However they confirm that they do proactively share their information with the Israeli military authorities, in an attempt to facilitate accountability for IHL violations and war crimes.

Yet the limitations the Israeli military places on the ability of human rights organization to operate raise questions not only about the ability of the Israeli authorities to investigate potential war crimes but also their willingness to do so. The Israeli military says that it relies on human rights organizations to provide evidence of alleged wrong-doing that it has difficulty obtaining because it has no investigators on the ground. Military investigators do indeed seek out information from these groups. Yet the Israeli military authorities systematically deny human rights groups the access they need to maximize their ability to detect and document potential serious crimes. For example, in 2014 the Israeli military’s refusal to issue permits meant that there were no independent weapons experts in Gaza who could review evidence directly, and the only weapons analysts available were those working for the Gaza authorities’ police department. The refusal to allow experts into Gaza – and the systematic refusal to permit human rights workers in Gaza to access the training and work meetings they need to do their jobs well – would seem to undermine the nature, extent and quality of the documentation that the Israeli military says it needs from human rights groups, compromising the capacity of the Israeli military to investigate potential war crimes. On the other hand, the policy of disallowing travel for human rights workers, in contrast to the hundreds of permits issued each month for humanitarian aid workers, for example, and the thousands of permits issued each month in total, also calls into question the willingness of the Israeli military to investigate potential war crimes. If the Israeli military was genuinely motivated to detect potential wrong-doing by soldiers and officers, why does it tie the hands of the human rights workers on the ground who, as the Israeli government acknowledges, are best-positioned to detect and document violations?

Response from Israeli Government

While preparing this report, Human Rights Watch sought and received comment and information from the Israeli authorities. In a response dated August 29, 2016, the military attorney general stated that it attributes “great importance” to its dialogue with human rights organizations, and that it maintains an “extensive and daily dialogue” with Israeli, Palestinian and foreign NGOs, including regarding allegations of misconduct during hostilities. The MAG’s Office said that it received 500 complaints relating to 360 individual incidents during the 2014 hostilities, some of which came from nongovernmental organizations. In addition, it said, it reviews reports published by Israeli, Palestinian, and foreign human rights organizations.

The MAG’s Office expressed criticism of those reports, writing that they “in many cases suffer from methodological, factual and legal flaws (for example, they rely on reporting from Palestinian sources without investigating their reliability, they identify terrorist activists as ‘civilians’ and incorrectly apply the laws of war). Sometimes these reports even exhibit a clear bias.”

However, the MAG’s Office wrote, “to the extent that these reports include information that is prima facie reliable and sufficiently concrete, the claims raised in these reports are passed along in order to make a decision about whether to open an inquiry or investigation or to receive a full picture as part of an ongoing inquiry or investigation.”

The MAG’s Office went on to write that “conducting investigations of operational incidents that took place during combat, in hostile territory, involves many difficulties. Despite these difficulties, the military investigative police make many efforts to conduct these investigations thoroughly, effectively and quickly, and receiving help from nongovernmental organizations is part of these efforts.” According to the MAG, human rights groups supply affidavits and physical evidence and facilitate witnesses giving testimony to military investigators.

The MAG’s Office did not directly address Human Rights Watch’s question regarding the apparent contradiction between the importance the authorities say they attach to the work of human rights organizations and the travel limitations they impose, but it said that the assistance provided by human rights organizations in inquiries related to the 2014 hostilities was effective, “despite unavoidable restrictions imposed on travel between Israel and the Gaza Strip due to weighty security and political considerations.”[81]

IV. International Law

Israeli Obligations to Palestinians in Gaza

Israel significantly reduced its control over Gaza in 2005, when it withdrew its permanent ground troop presence and civilian settlements. However, it continues to control movement into and out of Gaza, except for the Rafah crossing, and it controls all crossings between Gaza and the West Bank.

Israel, of course, controls its own border with Gaza. It controls Gaza’s territorial waters and airspace, and, citing security concerns, does not allow people in Gaza to operate an airport or seaport, making them dependent on foreign ports for travel abroad.[82] It also controls all travel between Gaza and the West Bank, irrespective of whether or not the traveler crosses through Israel. So even if a Palestinian human rights defender leaves Gaza for a trip to Europe and then flies to Jordan, Israel will not allow them to enter the West Bank to attend a meeting or workshop, even though they do not seek transit via Israel.[83] Such control allows the Israeli authorities to control the Palestinian population registry, including deciding who will be listed as a resident of Gaza or the West Bank, and the rates for the customs and value added taxes that it collects on behalf of the Palestinian Authority on goods entering the common market.[84] It controls a so-called “no-go” zone inside Gaza, near the border with Israel, which constitutes 17 percent of the territory of Gaza and a third of its arable land, as well as significant parts of Gaza’s infrastructure.[85]

In light of these controls that Israel effectively exercises over the lives and welfare of Gazans, Israel continues to owe obligations toward Palestinians in Gaza under the law of occupation. This “functional” approach to interpreting Israel’s obligations,[86] adopted by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), means that the framework of the law of occupation, including Article 43 of the Hague Regulations, applies to Israel’s regulation of movement to and from Gaza. This is how the ICRC explains it:

The ICRC considers, however, that in some specific and rather exceptional cases – in particular when foreign forces withdraw from occupied territory (or parts thereof) but retain key elements of authority or other important governmental functions usually performed by an occupying power – the law of occupation may continue to apply within the territorial and functional limits of such competences. Indeed, despite the lack of the physical presence of foreign forces in the territory concerned, the retained authority may amount to effective control for the purposes of the law of occupation and entail the continued application of the relevant provisions of this body of norms. This is referred to as the ‘functional approach’ to the application of occupation law. This test will apply to the extent that the foreign forces still exercise, within all or part of the territory, governmental functions acquired when the occupation was undoubtedly established and ongoing.

The functional approach described above permits a more precise delineation of the legal framework applicable to situations in which it is difficult to determine, with certainty, whether an occupation has ended or not.

It may be argued that technological and military developments have made it possible to assert effective control over a foreign territory (or parts thereof) without a continuous foreign military presence in the concerned area. In such situations, it is important to take into account the extent of authority retained by the foreign forces rather than to focus exclusively on the means by which it is actually exercised. It should also be recognized that, in these circumstances, the geographical contiguity between belligerent States could facilitate the remote exercise of effective control. For instance, it may permit an occupying power that has relocated its troops outside the territory to reassert its full authority in a reasonably short period of time. The continued application of the relevant provisions of the law of occupation is all the more important in this scenario as these were specifically designed to regulate the sharing of authority – and the resulting assignment of responsibilities – between the belligerent States concerned.[87]

While Israel claims that the law of occupation no longer applies to its actions toward Gaza,[88] the official position of the ICRC, and of the United Nations, is that Israel remains an occupying power in Gaza.[89]

The functional approach to the law of occupation means that responsibility is assigned commensurate with control. Where, for example, the Gaza authorities fail to protect human rights defenders who criticize the behavior of armed groups, it is they who bear responsibility because they operate a police force that controls daily life inside Gaza and should provide protection. But where, for example, the Israeli military refuses to allow human rights defenders to access training outside Gaza, it is the Israeli military that bears responsibility because it controls movement into and out of Gaza.

Article 43 of the Hague Regulations of 1907 outlines the powers and responsibilities of an occupying power. It authorizes an occupant to take restrictive measures that are militarily necessary but also requires the occupant to restore public order, meaning to facilitate normal civilian life to the extent possible.[90] Israel is authorized to restrict travel for concrete security reasons, and it has the sovereign authority to regulate who crosses through Israeli territory, for example on the way to the West Bank or foreign countries, but it must balance its military needs and its authority to regulate who may enter Israel with its obligations to facilitate normal life to protected persons living under occupation.

As an occupying power, Israel also has an obligation to respect the human rights of Palestinians living in Gaza and the West Bank,[91] including their right to freedom of movement throughout the Palestinian territory[92] and the rights for which freedom of movement is a precondition, for example the right to education[93] and the right to work.[94] Palestinians enjoy a right to travel – without arbitrary restrictions – between the two parts of the Palestinian territory, Gaza and the West Bank, which Israel recognized as a single territorial unit, to leave the Palestinian territory and to return to it. Individuals also have a right to leave their own country.[95] Under international human rights law, the right to travel can be restricted for security reasons and to protect public health, morals, public order and the rights and freedoms of others. Any such restrictions, however, must be proportional, and “the restrictions must not impair the essence of the right; the relation between right and restriction, between norm and exception, must not be reversed.”[96]

These obligations limit the ability of the Israeli government to restrict travel into and out of Gaza mostly to cases in which it is necessary to meet concrete, individualized security needs. The Israeli authorities also have an obligation to facilitate the proper functioning of civil society inside Gaza, including the human rights community which works to further protections for vulnerable members of society, develop democratic values and promote fundamental individual rights – all part of developing normal life in Gaza. There is an obligation to permit Palestinian human rights defenders to travel in and out of Gaza. However, Israel should normally not block the travel of foreign human rights defenders, present in Israel, who seek permission to enter Gaza.

The Israeli authorities should act in accordance with the United Nations Declaration on human rights defenders.[97] The Declaration states that individuals and groups working to defend human rights should be able to access resources, that NGOs have an important role to play in protecting human rights, and that limitations on the work of human rights defenders should accord with applicable international obligations.[98] Israeli authorities should consider the resources that Palestinian human rights defenders seek to access in the form of trainings abroad and foreign experts entering Gaza. In regulating access, they should take note of the role that human rights defenders play in developing and maintaining a society that protects and promotes human rights. While the declaration is not legally binding, it represents the consensus of the international community and enshrines rights protected in other instruments, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[99] Respect for its principles can be seen as part of facilitating normal civilian life for Palestinians who have lived under occupation for the last 50 years and seek to develop and enshrine human rights protections as part of public life in the occupied territory.

Analysis of Israel’s Travel Restrictions

Israel’s current criteria for evaluating travel requests – citing generalized security threats to limit travel to exceptional humanitarian circumstances personal to the applicant – are inconsistent with these obligations. It is noteworthy that in some cases, human rights workers receive permits to travel via the Erez crossing for an event sponsored by an international organization, medical treatment or other non-work related reasons, but the Israeli authorities refuse to allow those same individuals to travel to further their human rights work. Normal civilian life in Gaza requires allowing people to access family members, educational and economic opportunities, medical care, and other rights for which freedom of movement is a precondition. Travel, including for human rights and health workers, is also necessary for meeting humanitarian needs, and it is required by Israel’s obligations, under the Fourth Geneva Convention, to facilitate humanitarian access in Gaza.[100]

The restrictions imposed appear to contradict Israel’s own policy, as articulated by the most senior political and military officials including the prime minister, the defense minister and the army chief-of-staff, to improve living conditions in Gaza in order to enhance stability and security.[101] A properly functioning civil society helps communities thrive.

Israel has the sovereign authority to determine who may enter its borders. But Israel is barring Palestinians in Gaza from traveling abroad via their own ports, thus rendering them dependent on Israel for access. In addition, its authority to bar entry into Israel should be balanced by the obligations it assumes as the occupying power and its signing of international agreements requiring it to allow Palestinians to travel and choose their place of residence within the single territorial unit that Gaza and the West Bank comprise.[102]

Israel’s restriction on Palestinians traveling between Gaza and the West Bank is based on its characterization of the West Bank as a closed military zone and its characterization of Palestinians whose addresses are listed in Gaza within the Israeli-controlled population registry as foreigners with respect to the right to enter the West Bank. Based on that position, Palestinians with addresses listed in Gaza are barred from entering the West Bank via Jordan, through the Allenby crossing, which does not require entry into Israel. In other words, Israeli restrictions on travel for Gaza residents go beyond its interest in regulating who enters its own territory. They promote a policy to keep Palestinian residents of Gaza from entering the West Bank irrespective of whether or not that travel takes place via Israel.

Furthermore, Israel generally prevents foreigners, including human rights workers, already present in Israel, from crossing through the Erez crossing in order to reach Gaza. The substance of the restriction, therefore, is not refusal to allow foreigners to enter Israel but rather refusal to allow them to enter Gaza from Israeli territory, at a time when Israel is also preventing the operation of an airport or seaport that would allow independent access.

At the same time that Israel bars travel for human rights workers, since 2008 it has increased the number of crossings via Erez to thousands each month, a small fraction of the level of travel recorded prior to the outbreak of the second Intifada or uprising, but still an indication that, whatever security concerns may exist, much more can be done. Israel acknowledges that it weighs foreign policy considerations in determining which categories of Palestinians may travel, for example allowing travel at the request of diplomats from friendly nations or for football players, at the request of the world football organization FIFA. Israel should also take into account its obligations under IHL and human rights law and allow human rights workers the access they need to maximize the effectiveness of their work.

Egypt’s Role

Egypt is not an occupying power in Gaza and therefore, despite the devastating effect that its border closure has on life in Gaza, its legal responsibilities toward Gaza residents are more limited than those of Israel.[103] Like all parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention, Egypt should do everything within its power to ensure the universal application of the Convention’s humanitarian provisions, including protections for civilians living under occupation who are unable to travel due to unlawful restrictions imposed by the occupying power.[104] Egypt’s obligations to permit access into and out of Gaza also include facilitating humanitarian access and supplies to persons affected by armed conflict. The Egyptian authorities should also consider the impact of their border closure on the rights of Palestinians living in Gaza who are unable to travel in and out of Gaza through other routes. They should ensure that their decisions are transparent, free from arbitrariness and take into consideration the human rights of those affected. They should consider possible additional responsibilities they may have under the right of transit, usually invoked in cases of enclaves or land-locked states, and enshrined in a number of bilateral and multilateral treaties.[105] Gaza’s access to the sea for travel abroad has been blocked by Israel since 1967, rendering it dependent on neighboring states for transit. Given the importance of the Rafah crossing, Egypt should consider allowing transit via its territory, subject to security considerations. Certainly, Egypt has legitimate security concerns regarding the Sinai desert, but it should find a way to address them through means less extreme than total closure of the border, most of the time, especially considering the fact that it kept Rafah mostly open between 2010 and 2013, despite the activities of armed groups in Sinai during that time. The current border closures take place in the context of repressive activities taken against the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, which is allied with Hamas.

Egypt should normally permit passage for human rights workers, especially Palestinian workers and United Nations human rights investigators, into and out of Gaza. Egypt may also have additional duties under its human rights obligations, including the African Charter of Human and People’s Rights.[106]

ICC Prosecutor’s Office’s Role

The ICC prosecutor should consider Israeli restrictions on travel by human rights workers in assessing whether Israeli domestic legal authorities can effectively investigate potential serious crimes committed in Palestine since June 2014, particularly in assessing what is known as “complementarity”. Under ICC rules and jurisprudence, the ICC will not prosecute alleged serious crimes if domestic proceedings are ongoing or have been conducted, unless the national authority is unwilling or unable to conduct genuine investigations and prosecutions.[107] Even at the stage of preliminary examinations, the ICC prosecutor considers whether a case would be inadmissible due to the existence of genuine national investigations and prosecutions.

In its November 2016 report on ongoing preliminary examinations, the ICC prosecutor indicated that her office “will assess information on potentially relevant national proceedings, as necessary and appropriate.”[108] In deciding whether a case would be admissible, the ICC prosecutor examines whether national proceedings are taking place and if so, whether the authorities are genuinely able and willing to investigate and prosecute.[109] In the event that a person has already been tried for a crime or crimes, the ICC will not prosecute that individual for the same conduct, unless the domestic proceedings were not conducted independently or impartially in accordance with international due process norms or were conducted in a manner which, under the circumstances, “was inconsistent with an intent to bring the person concerned to justice.”[110]

While the two criteria – willingness and ability – are distinct, the ICC pre-trial chamber often assesses them together, as they are related.

In assessing the willingness of national authorities to carry out genuine investigations, the prosecutor considers, among other things, whether the way the proceedings are conducted indicates an intent to shield persons from criminal responsibility. The prosecutor can assess such intent by indicators that include “manifestly insufficient steps in the investigation or prosecution,” “flawed forensic examination,” and “lack of resources devoted to the proceedings at hand as compared with overall capacities.”[111]

In assessing the ability of national authorities to carry out genuine investigations, the prosecutor considers, among other things, “the ability of the competent authorities to exercise their judicial powers in the territory concerned” and “the absence of conditions of security for witnesses, investigators, prosecutors and judges or the lack of adequate protection systems.”[112] The ICC’s pre-trial chamber has in the past considered a national authority’s inability to obtain the necessary testimony from witnesses as an indicator of its inability to conduct adequate investigations and prosecutions.[113]

When it comes to the admissibility of cases being prosecuted, the assessment is holistic, with the ICC’s pre-trial chamber examining the entirety of the domestic proceedings, to determine their genuineness, including the availability of necessary witness testimony and documentary evidence.[114]

At this preliminary stage, in which the ICC prosecutor is examining the willingness of the Israeli authorities to investigate and prosecute potential serious crimes committed as part of the 2014 hostilities, she should consider the contradiction between the importance that the Israeli authorities’ state they attach to the role of human rights groups in obtaining evidence and witness testimony – and the steps the Israeli authorities take to limit and constrain the work of those same groups, Palestinian, foreign, and Israeli.

In evaluating the ability of the Israeli authorities to conduct genuine investigations, the prosecutor should consider the restrictions imposed by the Israel authorities on human rights workers which have, in turn, limited their ability to collect evidence for potential cases. Human rights organizations can be essential in identifying possible victims and providing physical evidence gathered in the context of their own investigations, as the Israeli Military Attorney General’s Office notes. However, the very tight restrictions on travel by Palestinian human rights workers and the blanket ban on workers from foreign human rights organizations entering Gaza limit the scope of witness testimony and physical evidence that can be available to the Israeli authorities.

The prosecutor should consider the limitations on forensic evidence available to the Israeli authorities as a result of their refusal to allow outside weapons experts into Gaza and to allow human rights workers in Gaza to leave Gaza in order to obtain training and certification. Further, Palestinian victims and witnesses may not be easily persuaded to come forward in light of their high levels of distrust of Israeli authorities, making it even more difficult to bring forward criminal cases and making the effective interventions of human rights organizations even more critical.