Summary

Basically, because of this law [SSMPA] the police treat people in any way that they please. They torture, force people to confess, and when they hear about a gathering of men, they just head over to make arrests.

-Executive Director of an Abuja NGO, October 2015

Vigilante groups have added homosexuality to their “terms of reference.” These groups are organized by community members, given authorization by the community to maintain some sort of order and “security.”

-Executive Director of a Minna, Niger State NGO, October 2015

On January 7, 2014, Nigeria’s former president, Goodluck Jonathan, signed the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill (SSMPA) into law. The notional purpose of the SSMPA is to prohibit marriage between persons of the same sex. In reality, its scope is much wider. The law forbids any cohabitation between same-sex sexual partners and bans any “public show of same sex amorous relationship.” The SSMPA imposes a 10-year prison sentence on anyone who “registers, operates or participates in gay clubs, societies and organization” or “supports” the activities of such organizations. Punishments are severe, ranging from 10 to 14 years in prison. Such provisions build on existing legislation in Nigeria, but go much further: while the colonial-era criminal and penal codes outlawed sexual acts between members of the same sex, the SSMPA effectively criminalizes lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

This report documents the human rights impact of the SSMPA on LGBT individuals and its effects on the activities of non-governmental organizations that provide services to LGBT people. This followed consultations with Nigeria-based LGBT activists and groups, and mainstream human rights organizations.

While existing legislation already criminalizes consensual same-sex conduct in Nigeria, the report found that the SSMPA, in many ways, officially authorizes abuses against LGBT people, effectively making a bad situation worse. The passage of the SSMPA was immediately followed by extensive media reports of high levels of violence, including mob attacks and extortion against LGBT people. Human rights groups and United Nations officials expressed grave concern about the scope the law, its vague provisions, and the severity of punishments. On February 5, 2014, following the passage of the SSMPA, the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders in Africa noted with concern in a press release, “the increase in cases of physical violence, aggression, arbitrary detention and harassment of human rights defenders working on sexual minority issues.”

While Human Rights Watch found no evidence that any individual has been prosecuted or sentenced under the SSMPA, the report concludes that its impact appears to be far-reaching and severe. The heated public debate and heightened media interest in the law have made homosexuality more visible and LGBT people even more vulnerable than they already were. Many LGBT individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that prior to the enactment of the SSMPA in January 2014, the general public objected to homosexuality primarily on the basis of religious beliefs and perceptions of what constitutes African culture and tradition. The law has become a tool being used by some police officers and members of the public to legitimize multiple human rights violations perpetrated against LGBT people. Such violations include torture, sexual violence, arbitrary detention, violations of due process rights, and extortion. Human Rights Watch research indicates that since January 2014, there have been rising incidents of mob violence, with groups of people gathering together and acting with a common intent of committing acts of violence against persons based on their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity.

For instance, in February 2014 in Gishiri village, Abuja, a group of approximately 50 people armed with machetes, clubs, whips, and metal wires dragged people from their homes and severely beat at least 14 men whom they suspected of being gay. Three victims told Human Rights Watch that their attackers chanted: “We are doing [President Goodluck] Jonathan’s work: cleansing the community of gays.” Another victim said that the attackers also shouted: “Jungle justice! No more gays!”

Arbitrary arrest and extortion by police is commonplace under the SSMPA. Interviewees in Ibadan and other places told Human Rights Watch that they had been detained by the police multiple times since the passage of the SSMPA. Human Rights Watch interviewed eight of the 21 young men who were arrested, but not charged, at a birthday party in Ibadan. They told Human Rights Watch that members of the public informed the police that gay men were gathered together and when police arrived and found a bag of condoms that belonged to an HIV peer educator, they were all arrested. They were held in police custody for four days, and released, without charge, after paying bribes ranging from 10,000-25,000 Naira (approximately US$32-64). These individuals said they had never been subjected to questioning, arrest, or detention prior to the enactment of this law. Individuals who have been arrested and detained are released on “bail,” usually after offering bribes to the police. Faced with 14 years’ imprisonment, several interviewees said they had little choice but to pay.

Lesbians and gay men interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the law has had an insidious effect on individual self-expression. Since January 2014, several said that they had adopted self-censoring behavior by significantly and consciously altering their gender presentation to avoid detection or suspicion by members of the public and to avoid arrest and extortion. They told Human Rights Watch that this was not necessarily a major concern prior to the passage of the SSMPA. Lesbian and bisexual women in particular reported that fear of being perceived as “guilty by association” led them to avoid associating with other LGBT community members, increasing their isolation and, in some cases, eventually compelling them to marry an opposite-sex partner, have children, and conform to socially proscribed gender norms.

The SSMPA contributes significantly to a climate of impunity for crimes committed against LGBT people, including physical and sexual violence. LGBT victims of crime said the law inhibited them from reporting to authorities due to fear of exposure and arrest. “No way would we file a complaint,” Henry, a victim of mob violence in Lagos, said. “When it’s an LGBT issue, you can’t file a complaint.” Henry told Human Rights that the mob attack in June 2014 in Lagos was the first time that he had been a victim of violence because of his sexual orientation, and that prior to the SSMPA, he had no reason to file complaints with the police.

Interviewees, including representatives of mainstream human rights organizations, said the SSMPA has created opportunities for people to act out their homophobia with brutality and without fear of legal consequences. Under the auspices of the SSMPA, police have raided the offices of NGOs that provide legal and HIV services to LGBT communities. For example, shortly after the SSMPA passed in January 2014, police raided an HIV awareness meeting in Abuja and arrested 12 participants on suspicion of “promoting homosexuality.” They were detained in police custody, without charge, for three weeks, before paying a bribe of 100,000 Naira (approximately $318) to secure their release.

Punitive legal environments, stigma, and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, together with high levels of physical, psychological, or sexual violence against gay men and other men who have sex with men (MSM), impedes sustainable national responses to HIV. When acts of violence are committed or condoned by officials or national authorities, including law enforcement officials, this leads to a climate of fear that fuels human rights violations and deters gay men and other MSM from seeking and adhering to HIV prevention, treatment, care, and support services.

The SSMPA contravenes basic tenets of the Nigerian Constitution, including respect for dignity and prohibition of torture. It also goes against several regional and international human rights treaties which Nigeria has ratified, including the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Human rights treaties impose legal obligations on Nigeria to prohibit discrimination; ensure equal protection of the law; respect and protect rights to freedom of association, expression, privacy, and the highest attainable standard of health; prevent arbitrary arrests and torture or cruel, degrading, and inhuman treatment; and exercise due diligence in protecting persons, including LGBT individuals, from all forms of violence, whether perpetrated by state or non-state actors.

In November 2015, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights urged the Nigerian government to review the SSMPA in order to prohibit violence and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity and ensure access to HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for LGBT individuals.

Nigerian authorities should act swiftly to protect LGBT people from violence, whether committed by state or non-state actors. Law enforcement officials should stop all forms of abuse and violence against LGBT people, including arbitrary arrest and detention, torture in custody, and extortion, and without delay ensure that they are able to file criminal complaints against perpetrators.

The government of Nigeria, including the Ministry of Health and the National Agency for the Control of AIDS, should:

- Advocate for the repeal of the specific provisions of the SSMPA that criminalize the formation of and support to LGBT organizations;

- Promote effective measures to prevent discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in health care settings; and

- Ensure that key populations, including gay men, MSM, and transgender individuals have access to HIV services, care, and treatment.

The National Human Rights Commission should ensure that the Committee of Human Rights Experts, established in November 2015, mandated to compile a list of laws to be reviewed for compliance with human rights norms and standards, prioritizes the SSMPA for review. One of the key functions vested in national human rights institutions is to receive and investigate complaints of human rights abuses. In terms of the Human Rights Commission Act of 1995, as amended in 2010, the Commission enjoys quasi-judicial powers to summon persons, evidence, and to award compensation and enforce its decisions. The Commission should utilize this protective mandate to investigate human rights abuses committed against LGBT persons.

Recommendations

To the Government of Nigeria

- Investigate all claims of extortion, arbitrary arrests and detention, torture, and inhuman treatment by police officers and prosecute those responsible for human rights abuses against LGBT people.

- Publicly condemn all acts of violence, including mob attacks, committed by state and non-state actors on the basis of real or perceived sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Act with due diligence to protect LGBT individuals against human rights abuses, including by effectively implementing all appropriate laws, including the Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act, 2015, in order to prohibit and punish all forms of violence, including violence and human rights abuses committed on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Review the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act, 2014 with a view to creating an enabling environment for LGBT individuals, human rights defenders, and organizations to exercise their constitutional rights to freedom of association and expression.

- Elaborate and ensure the effective implementation of laws and policies in accordance with regional and international human rights treaties to which Nigeria is a state party.

- Invite the Special Mechanisms of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, in particular the Special Rapporteurs on Human Rights Defenders, and on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information, to conduct unrestricted visits to Nigeria.

- Ensure the effective implementation of all the recommendations contained in the Concluding Observations adopted at the 57th Ordinary Session of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and in particular:

- Review the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act (SSMPA).

- Adopt all necessary legislative and policy measures in order to protect LGBT individuals from violence and ensure that LGBT organizations exercise their constitutional rights to freedom of association and expression.

- Conduct a human rights-based review of the SSMPA in order to ensure the successful implementation of the recently adopted HIV and AIDS (Anti-Discrimination) Act, 2014 law and allow for non-discriminatory access to health care services for LGBT persons, in line with international guidelines and human rights obligations.

- Take all necessary measures to raise awareness about the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and other human rights instruments among the Nigerian populace, including through its incorporation in the curricula of formal and vocational institutions, and through other informal civic education programs.

- In accordance with obligations under international human rights treaties, take all necessary measures to ensure the respect for and protection of human rights of LGBT persons in Nigeria.

- Adopt legislative measures to protect human rights defenders in conformity with the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Defenders 1998 and the Commission’s Resolutions on Human Rights Defenders including ACHPR/Resolution 69 (XXXV) 04, ACHPR/Resolution 119 (XXXXII) 07, and ACHPR/Res.196 (L) 11, and also create a forum for dialogue with civil society. In particular:

- Take political, administrative, and legislative measures to ensure that human rights defenders working on sexual orientation and gender identity issues, including women human rights defenders, work in an enabling environment that is free of stigma, reprisals, or criminal prosecution as a result of their human rights protection activities.

To the Nigeria Police Force and the Ministry of Police Affairs

- Issue clear directives to Commissioners of Police and other senior police officers to ensure that the police do not engage in extortion, bribe-taking, and other corrupt acts on the basis of SSMPA, against LGBT individuals and other people.

- Ensure that the Human Rights Desks at Police Stations provide a safe environment for LGBT persons to report police abuses and that the complaints are processed and investigated without undue delay.

- Investigate in a prompt and thorough manner all law enforcement officials implicated in arbitrary arrests, extortion, torture in detention, and other human rights abuses of persons on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Establish effective systems to record and investigate all acts of violence against LGBT persons.

- In collaboration with civil society organizations, implement rigorous training programs for police officers on the Nigerian Constitution and its applicability to LGBT people in Nigeria.

- Publicly condemn the police practice of using the SSMPA to extort LGBT people.

- Develop and implement appropriate awareness-raising interventions on the human rights of LGBT persons in Nigeria.

To the Federal Ministry of Health

- Ensure that training for all medical professionals and health care workers includes a component on discrimination and HIV issues affecting LGBT people.

- Ensure the effective implementation of and compliance with the HIV/AIDS (Anti-Discrimination) Act, 2014 that makes it illegal to discriminate against people based on their HIV status.

- Publicly condemn cases in which organizations, peer educators, and outreach workers providing services to LGBT people are targeted for arrest and extortion by the police or threatened with violence by members of the public.

- Advocate for the review of the SSMPA in order to improve access to HIV prevention and treatment services for LGBT people and MSM.

To the National Agency for the Control of AIDS

- Ensure the effective implementation of all the recommendations in the 2015 Report on the Legal Environment Assessment for HIV/AIDS Response in Nigeria.

- Establish sensitization programs for the Police, National Assembly, and members of the public on the provisions and implications of the SSMPA and the HIV/AIDS (Anti-Discrimination) Act, 2014.

- Conduct an independent nationwide study to assess the impact of the SSMPA particularly on the health-seeking behavior of gay men and MSM since January 2014.

- Ensure that training programs for employees of the Agency and other appropriate persons include a component on the prohibition of discrimination in HIV services for LGBT people.

To the National Human Rights Commission

- Instruct the Commission’s Committee of Human Rights Experts to include the SSMPA on its list of laws to be reviewed for consistency with the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and regional and international human rights norms and standards.

- Develop plans and allocate adequate resources to ensure systematic documentation and monitoring of human rights violations associated with the SSMPA.

- Collect accurate sex-disaggregated data relating to acts of violence and discrimination due to real or perceived sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Investigate all human rights violations based on sexual orientation and gender identity in accordance with the protection mandate.

- Actively engage with LGBT human rights organizations in order to encourage LGBT persons to file complaints with the Commission.

- Act in accordance with its mandates to act as a source of human rights information for the government and the public, to raise awareness about the human rights impact of the SSMPA, and to receive and investigate complaints from LGBT individuals alleging human rights abuses committed against them.

To the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- Ensure the Nigerian government’s compliance with obligations set out in the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and with recommendations set out in ACHPR Resolution 275: Protection against Violence and other Human Rights Violations against Persons on the basis of their real or imputed Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity by:

- Engaging Nigeria in a constructive dialogue during the bi-annual ordinary sessions of the African Commission on progress, obstacles, plans, and other measures that have been adopted to ensure implementation of recommendations.

- In accordance with article 45(1) and as necessary, article 58 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, conduct a country visit to Nigeria to promote human rights and investigate human rights violations, including human rights abuses of LGBT individuals.

- Work with stakeholders in Nigeria to institutionalize formal processes of dialogue with human rights defenders who work on sexual orientation and gender identity issues and develop concrete protection and monitoring mechanisms for national and regional levels.

- Ensure that special mechanisms integrate sexual orientation and gender identity issues in the execution of their mandates, including when adopting thematic and country-specific resolutions and elaborating thematic studies and reports.

Glossary

Bisexual: Sexual orientation of a person who is sexually and romantically attracted to both men and women.

Gay: Synonym in many parts of the world for homosexual; used here to refer to the sexual orientation of a man whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward other men.

Gender: Social and cultural codes (as opposed to biological sex) used to distinguish between what a society considers “masculine” or “feminine” conduct.

Gender identity:A person’s internal, deeply felt sense of being female or male, both, or something other than female and male. A person’s gender identity does not necessarily correspond to the biological sex assigned at birth.

Homophobia: Fear and contempt of homosexuals, usually based on negative stereotypes of homosexuality.

Homosexual: Sexual orientation of a person whose primary sexual and romantic attractions are toward people of the same sex.

Human rights defender: A term used to describe people who, individually or with others, act to promote or protect human rights.

Key Populations / Key Populations at Higher Risk of HIV Exposure:Those most likely to be exposed to HIV or to transmit it. In most settings, those at high risk of HIV exposure include men who have sex with men, transgender people, people who inject drugs, sex workers and their clients, and serodiscordant (couples in which one partner is HIV positive and one is HIV negative).

LGBT: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender; an inclusive term for groups and identities sometimes associated together as “sexual minorities.”

Lesbian: Sexual orientation of a female whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward other females.

Member of the community: A Nigerian term used by LGBT individuals and others to articulate their belonging to the LGBT community in Nigeria.

Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM):Men who have sexual relations with persons of the same sex, but may or may not identify themselves as gay or bisexual. MSM may or may not also have sexual relationships with women.

Sexual orientation: The way a person’s sexual and romantic desires are directed. The term describes whether a person is attracted primarily to people of the same sex, the opposite sex, both or neither.

Sex Work: The commercial exchange of sexual services between consenting adults.

Transgender: The gender identity of people whose birth gender (which they were declared to have upon birth) does not conform to their lived and/or perceived gender (the gender that they are most comfortable with expressing or would express given a choice). A transgender person usually adopts, or would prefer to adopt, a gender expression in consonance with their preferred gender but may or may not desire to permanently alter their bodily characteristics in order to conform to their preferred gender.

Methodology

This report is based primarily on interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers in Nigeria from October 2015 to November 2015, telephone interviews in December 2015 and March 2016, as well as interviews with Nigerian activists in Banjul, The Gambia in April 2016, during the course of the 58th Ordinary session of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

In October and November 2015, Human Rights Watch conducted in-depth research in Nigeria to assess the human rights impact of the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act, 2013 (SSMPA) on LGBT people and on Nigeria-based organizations that provide services to LGBT people or advocate for their rights. The research was conducted following extensive consultations with Nigeria-based LGBT activists and organizations.

While recognizing that existing legislation in Nigeria criminalizes consensual same-sex conduct, this report is strictly limited to the impact of the SSMPA. On the basis of extensive media reports and consultations with LGBT groups, it became clear that the enactment of the SSMPA was immediately followed by high levels of violence, including mob attacks, arbitrary arrests, and detention and extortion against LGBT people by some police officers and members of the public. This report finds that the SSMPA has exacerbated human rights abuses against LGBT people in Nigeria.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 73 Nigerians who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) as well as representatives of 15 Nigeria-based non-governmental organizations. In the course of conducting the research, interviewees would initially identify as a “member of the community” and with further clarification, identify as either gay or lesbian. We interviewed two persons who identify as transgender women and since we did not conduct any interviews with intersex persons, the acronym used throughout the report is LGBT.

Human Rights Watch conducted field research in Abuja, Lagos, and Ibadan, and interviewed activists working with LGBT people and on a range of other human rights issues, in particular access to HIV services and treatment, from Kano, Kaduna, Delta, Cross River, Zamfara, and Niger States. The cities were chosen based on the presence of non-governmental organizations and community-based activists. Human Rights Watch worked with activists in Nigeria to identify relevant NGOs and their representatives, who in turn helped Human Rights Watch identify victims of violence in various Nigerian states.

Interviews were conducted in English and without interpreters. Participants were all informed of the purpose of the interview and they provided their consent orally. All interviews conducted in person were held in secure locations identified by the interviewee. Interviewees were not compensated, but we reimbursed transport costs, and the cost of a meal where necessary, to those who travelled from their homes to meet Human Rights Watch researchers. Interviewees from Kano, Cross River, Zamfara, and Niger States were reimbursed for transport costs and provided with overnight accommodation and meals. The report uses pseudonyms, unless otherwise noted, to protect interviewees against possible reprisals.

In addition to in-depth interviews with victims of human rights violations and NGO representatives, Human Rights Watch met with representatives of the National Agency for the Control of AIDS, the diplomatic community, and United Nations officials based in Abuja in order to gain a broader understanding of the impact of the SSMPA. The report draws from relevant published sources, including court decisions, reports of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and United Nations documents as well as reports by other human rights organizations and, as relevant, academic articles.

On January 15, 2016, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Nigeria National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), providing a brief summary of preliminary research findings (Annex 3). In this correspondence we requested that the Committee of Human Rights Experts, established by the NHRC in November 2015, include the SSMPA on its list of laws to be reviewed for consistency with the Nigerian Constitution as well as regional and international human rights norms and standards. The Commission has not responded to our letter at time of writing.

On October 3, 2016, Human Rights Watch wrote to the NHRC to present an advance and embargoed draft copy of the relevant section of the report, to request an official response and to inquire whether the SSMPA is included in the list of laws for review (see Annex 4). On October 6, the Executive Director of the NHRC responded by email, confirming that the SSMPA is one of the laws he has “personally requested the Committee to specifically consider” (see Annex 7). On October 3, 2016, Human Rights Watch wrote to officials in the Ministry of Police (see Annex 5) and the National Agency for the Control of AIDS (see Annex 6) to present an advance and embargoed draft copy of the relevant section of our report and to request an official response. The Ministry of Police and the National Agency for the Control of AIDS have not responded to our letters at time of writing.

I. Background

In March 2015, President Muhammadu Buhari was elected to a four-year term, replacing Goodluck Jonathan. The new administration is confronted with a multitude of profound human rights challenges, ranging from the conflict in the northeast between the militant group Boko Haram and Nigeria’s security forces; the humanitarian crisis faced by 2.5 million internally displaced persons, particularly women and girls; and corruption and weak governance in public sector institutions, including in law enforcement and legislative frameworks.[1] The human rights abuses suffered by LGBT people in Nigeria following the enactment of the SSMPA must be understood within this broader context, and not in isolation from or as exception to other human rights violations.

According to the Nigeria Bureau of Statistics, the unemployment rate was recorded at 12.1 percent in the first quarter of 2016, or 9.485 million unemployed people.[2] Nigeria is a country in which religion plays a significant role in people’s lives, including LGBT individuals. Christianity predominates in southern states and Islam in northern states. The country has the second highest burden of HIV in Africa; of all people living with HIV globally, 9 percent of them live in Nigeria. An estimated 3.2 million people are currently living with HIV.[3] According to the Nigeria National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA), key affected populations (KAPs), which include men who have sex with men (MSM) and their partners, contribute 32 percent of new infections.[4]

The 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria protects a range of fundamental rights, including respect for dignity of the person and prohibition of torture, inhuman, or degrading treatment; personal liberty; privacy; due process rights; and the rights to freely assemble and associate with other persons, including forming any association for the protection of one’s interest.[5] According to Section 15(2) of the Constitution, a citizen of Nigeria may not be discriminated against on the grounds of “place of origin, sex, religion, status, ethnic or linguistic association or ties.”[6]

Sexual orientation and gender identity is not enumerated as a prohibited ground for discrimination in Nigeria’s Constitution. The Human Rights Committee, the United Nations treaty body that monitors state parties’ compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, in determining a case before it, confirmed that, “the reference to ‘sex’ in articles 2, paragraph 1 and 26 is to be taken as including sexual orientation.”[7] Nigeria has ratified several regional and international treaties that obligate it to respect and protect rights to freedom of association, expression, privacy, and the highest attainable standard of health; to prevent arbitrary arrests and torture; and to exercise due diligence in protecting persons, including LGBT individuals, from all forms of violence, whether perpetrated by state or non-state actors.

Two laws passed in 2015 are noted as positive developments in the context of the protection of LGBT persons in Nigeria, in the event that they are effectively implemented and without discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. On May 25, 2015, the National Assembly enacted the Violence against Persons (Prohibition) Act, 2015 (the Prohibition of Violence Act).[8] The purpose of this law is “to eliminate violence in private and public life, prohibit all forms of violence against persons and to provide maximum protection and effective remedies for victims and punishment of offenders.”[9] The law addresses and criminalizes the various forms of violence to which LGBT people in Nigeria are routinely subjected, including sexual violence, with its expanded definition of rape to include male rape. In March 2016, the Nigerian president signed into law the HIV/AIDS (Anti-Discrimination) Act, 2014. The purpose of this law is to prevent discrimination based on real or perceived HIV status and to ensure access to health care and other services to everyone, presumably including LGBT people.[10]

The Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act, 2013 was introduced into a legal context that already criminalized consensual adult same-sex conduct. The Nigeria Criminal Code Act of 1990, with origins in the colonial era, contains provisions dealing with Offences against Morality committed by men that carry terms of imprisonment of up to 14 years.[11] The Sharia Penal code adopted by several northern Nigerian states prohibits and punishes sexual activities between persons of the same sex, with the maximum penalty for men being death by stoning, and for women, whipping and/or imprisonment.[12]

This report does not document arrests or prosecutions under the Criminal Code or Sharia Penal Code. In 2011, some Nigerian human rights organizations, in collaboration with their regional and international partners, submitted a Shadow Report to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights documenting instances of arrests and prosecution in Sharia Courts, particularly in Bauchi and Kaduna, and other human rights abuses on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in other parts of the country.[13] Representatives of LGBT organizations and other individuals told Human Rights Watch that while there were arrests and human rights abuses prior to January 2014, there was a noticeable increase, after the enactment of the SSMPA, in violence and extortion by police and members of the public.

First introduced in March 2006, the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill was met with strong opposition from domestic, regional, and international human rights groups—including United Nations officials, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and domestic and international human rights organizations—which predicted it would lead to arbitrary arrests, extortion, and marginalization of the already stigmatized LGBT population.[14]

During the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) process at the UN Human Rights Council[15] on October 22, 2013, Nigeria rejected recommendations to revise laws discriminating against LGBT persons, enact legislation to prevent violence against people based on sexual orientation, and refrain from signing into law any new legislation to further criminalize LGBT people and same-sex relations.[16]

President Jonathan remained undeterred and signed the bill into law on January 7, 2014. On June 6, 2016, Jonathan justified his actions in respect of the law as respect for democracy and the will of a population that opposed same-sex unions: “98 per cent of Nigerians did not think that same-sex marriage should be accepted by our society,” he said. “The bill was passed by 100 percent of my country’s National Assembly. Therefore as a democratic leader with deep respect for the law, I had to put my seal of approval on it.”[17]

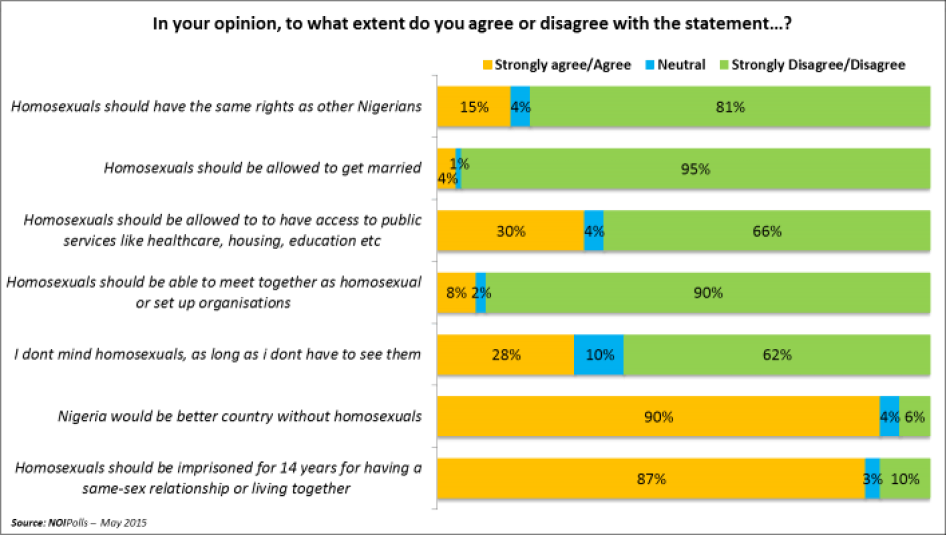

A June 2013 poll conducted by NOIPolls, prior to the enactment of the SSMPA, found that for moral and religious reasons, approximately 92 percent of Nigerians supported the proposed law, and did not see it as infringing on the human rights of the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community.[18] In 2015, NOIPolls, in partnership with The Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERs),[19] a Nigeria-based non-governmental organization working to protect and promote the human rights of sexual minorities, and Bisi Alimi Foundation,[20] an entity that works to encourage the acceptance of LGBT people in Nigeria, conducted a second poll following complaints that the SSMPA enables law enforcement agencies to violate the human rights of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals.[21] The findings of the second poll, that 87 percent of Nigerians continued to support the SSMPA, is significant in that it demonstrates a 5 percent decrease in the number of people who support the SSMPA.[22] Further, 15 percent believed homosexuals should have equal rights and 30 percent believed lesbian, gay, and bisexual people should have the same access to public services such as health care, housing, and education.[23] While the general public continues to support the prohibition and criminalization of same-sex marriage and civil unions in Nigeria, it is significant that nearly a third of Nigerians do not agree with discrimination in access to socioeconomic rights for lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons.

Source: NOI Polls[24]

The purported aim of the SSMPA is to prohibit marriage or civil unions between persons of the same sex and impose criminal penalties for persons convicted of entering such a union.[25] In reality, its scope is much wider. The law forbids any cohabitation between same-sex sexual partners; bans any “public show of same sex amorous relationship;” and prohibits anyone from forming, operating, or supporting “gay clubs, societies and organizations.”[26] Punishments are severe, ranging from 10 to 14 years in prison.[27]

When the law was passed in January 2014, it elicited concern from the international community, including the United Nations and the African Commission, about its potential impact on human rights. On January 14, 2014, former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navanethem Pillay, called the SSMPA a “draconian new law” that “makes an already bad situation worse”:[28]

Rarely have I seen a piece of legislation that in so few paragraphs directly violates so many basic, universal human rights … rights to privacy and non-discrimination, rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly, rights to freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention: this law undermines all of them.

High Commissioner Pillay predicted the law risked “reinforcing existing prejudices towards members of the LGBT community, and may provoke an upsurge in violence and discrimination.”[29] At the same time, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund) warned that the SSMPA would impede access to HIV services for LGBT people in Nigeria.[30]

On February 5, 2014, Commissioner Alapini-Gansou, Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders in Africa, a special mechanism of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, voiced concern about “physical violence, aggression, arbitrary detention and harassment carried out against human rights defenders dealing with sexual minority rights issues” in the wake of the law being passed.[31] In October 2015, Martin Ejidike, a Senior Human Rights Advisor with the United Nations in Abuja, told Human Rights Watch: “The law has opened up an avenue for extortion by some unscrupulous law enforcement officials.”[32]

The report finds that while the SSMPA was introduced into a legal context that already criminalized consensual same-sex conduct and an already pervasive homophobic climate, it has had profoundly negative human rights impact on LGBT people in Nigeria. In an interview published by PEN America, Bisi Alimi, an activist and writer of Nigerian origin states:

Before [the law], I think there was a conscious effort on the part of the attacker to think, where do I stand–If I beat up a gay person and get arrested, what is the law going to say? Now, there’s awareness that if I beat up a gay person, I’m actually doing justice, protecting the law of the land. The law has given people that boldness.[33]

Findings from a quantitative cohort study designed to assess the impact of the law on health-seeking behavior confirmed the above-stated observations by UNAIDS and the Global Fund. The study, conducted between March 2013 and August 2014, assessed the engagement of MSM from Abuja in HIV prevention and treatment services at a clinical site located within a community-based organization.[34] The SSMPA was enacted midway through the study, between enrollment and data collection. The findings below illustrate a sharp and immediate negative impact of the SSMPA on stigma, discrimination, and engagement in HIV prevention and treatment services.

Source: The Lancet[35]

Source: The Lancet[36]

The researchers of the cohort study,[37] finding a higher proportion of MSM reporting discrimination and stigma after the passage of the Act, concluded that:

Gay men and MSM in Abuja, Nigeria, experienced increased stigma and discrimination after the signing of the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act. Reports of fear of seeking health care, avoidance of health care, absence of safe spaces to socialize with other MSM, blackmail, and verbal harassment remained steady in the months of enrolment and follow-up before the law, then immediately increased in the post-law period … incidence of both fear of seeking health care and absence of safe spaces were significantly greater post-law than pre-law.[38]

Despite these research findings and dozens of statements from those directly affected and organizations that provide services to LGBT people, NACA continues to make official statements oblivious to the tangible climate of fear created by the passage of the SSMPA. NACA officials have denied knowledge of, if not outright refuted, widespread views that the law has had a negative impact on health-seeking behavior.[39]

SSMPA: Reality and Perceptions

Representatives of non-governmental organizations told Human Rights Watch that because the law is overly broad and with certain vague provisions, it is widely misunderstood by the general public.

LGBT individuals and representatives of LGBT organizations told Human Rights Watch that the one common misconception since the passage of the SSMPA is that homosexual identity is now a criminal offence, that members of the public have a duty to report any person they know or suspect to be homosexual, and that failure to do so is also a crime.[40] In reality, there are no specific provisions that expressly require members of the public to report LGBT people to authorities, nor does the law criminalize failure to report.

Christopher from Ibadan told Human Rights Watch that a friend of his father, a church minister, told him: “If you don’t send your son away, you could get 10 years in prison and your son 14 years.”[41] His father evicted him from his home in March 2014 and he has not seen his family since.

A representative of a human rights organization in Nigeria told Human Rights Watch that there is also no space for robust public debate about the impact of the law.[42] This has led to a situation in which LGBT people also misunderstand the law and now perceive themselves to be criminals. John, a lawyer based in Abuja, who regularly assists LGBT individuals who have been arbitrarily arrested by the police, said this misperception meant LGBT people may not report crimes committed against them, including crimes committed by police officers.[43] He told Human Rights Watch: “When clients who have been arbitrarily arrested call me, they don’t want to be named, they beg me to negotiate with the police.”[44]

The law has also had an inhibiting effect on public speech, contributing to a lack of awareness and misunderstandings about the law, but also about sexual orientation and gender identity more generally. According to a representative of a Lagos-based NGO interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Banjul, the Gambia:

During a radio interview in March 2016, the producer of the show said that we should not say anything that hints at or is specifically related to sexual orientation, not to demonstrate any support for sexual orientation issues or sympathy to homosexuality, in particular male homosexuality.[45]

In 2015 the National Agency for the Control of AIDS and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) conducted a legal assessment to identify and review HIV, health, and related laws, including the SSMPA, to establish impact of laws on the national response to HIV and AIDS.[46] The report, “Legal Environment Assessment for HIV/AIDS Response in Nigeria,” concludes that there is limited understanding of the provisions of the SSMPA, stating, “apart from the fact that they have not read the law, the Police have also given the impression that the law is aimed at arresting homosexuals.[47]

II. Public Violence against LGBT People

The SSMPA has for sure empowered the public to take the law into their own hands. People are routinely paraded in public, naked, for supposedly being caught in the act. They use the naked parade to rob, extort, humiliate, and shame us. They say they are preserving the so-called Nigerian African culture.

-Human Rights Defender, Abuja, November 2015

The SSMPA has helped create a generalized climate of fear and self-censorship for LGBT people and contributed to a culture of impunity for police and members of the general public.

LGBT individuals and human rights defenders in Nigeria told Human Rights Watch that following the enactment of the SSMPA, they have been at particular risk of violence from members of the public because of their real or perceived sexual orientation. This violence takes many forms, including public beatings, sexual violence, psychological violence, and deprivations of their liberty.

Mob Violence

This report finds, according to LGBT individuals and representatives of organizations interviewed by Human Rights Watch, that since the passage of the SSMPA, various suburbs in some Nigerian cities appear to have witnessed an upsurge in violence directed against LGBT people. Mob attacks, in which groups of people in public settings hunt down and beat individuals, have taken place in broad daylight while the police have stood by or, in some cases, actively participated in the violent attacks. LGBT individuals and organizations told Human Rights Watch that mob attacks, strictly on the basis of a person’s real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity, did not take place prior to the passage of the SSMPA. In the first reported incident of mob violence in Abuja, police officers accompanied the mob.[48] The mob attacks have taken place in different parts of the country, with varying levels of brutality.[49]

An activist who has worked with LGBT people for over 15 years in several Nigerian cities told Human Rights Watch:

Vigilante groups have added homosexuality to their terms of reference. These groups are organized by community members, given authorization by the community to maintain some sort of order and security for the community. Neighbors are now equipped with a tool that makes them hunters, and gay people are the prey. They enter homes in the middle of the night hoping to find people in compromising positions.[50]

Members of the public who participated in mob violence are believed to have been motivated by the enactment of the SSMPA. In February 2014, in Gishiri village, Abuja, a group of about 50 people stormed the homes of individuals and severely beat at least 14 men who they suspected of being gay.[51]

Peter, another victim of the Gishiri mob attack told Human Rights what he witnessed on the night of the attack in Gishiri village:

There were many people, carrying different types of weapons. One of them said they have been sent by the President to deal with gay people. The mob was going from house to house looking for gay people, and they had police officers with them. We could not sleep in our house that night; we had to sleep under a bridge.[52]

Human Rights Watch does not have evidence proving that the former president of Nigeria issued such instructions to members of the public.

According to Olu, 20 to 30 men came to his door wielding knives and pieces of cut glass:

They said, “We don’t want gays!” They demanded we come outside, but we were afraid. At that time, as one of my friends was coming home, they attacked him with wood with nails. They held him down and beat him. They said: “If you don’t come out we will kill him!” So the three of us went out and tried to fight. They were beating us, threatening to strip us naked…. I had a lot of injuries. I had a dislocated shoulder, bruises, and a cut on my head from the beating. I had to have stitches on my head. They used all kinds of things—wood, iron—to hit us.[53]

On January 21, just a few days after the SSMPA was passed, Debbie, a transgender woman, was beaten by a group of six men in Ado Ekiti, the capital of Ekiti State. She told Human Rights Watch that while she was at home with her boyfriend, six hefty guys knocked on the door and said, “We will kill you! You will get 14 years in prison!”[54] Debbie says:

We were beaten black and blue. I was hurting so much. I was shouting, “Help, help!” Some neighbors rushed over and the hoodlums ran away and we were taken to the chemist [pharmacy] for medicines. When we came home the men were waiting for us. They said, “If you don’t pack out, we will burn your house overnight. You are in a country that doesn’t allow homosexuality.”

The combined threat to kill and send some someone to prison for 14 years may seem incoherent. Nevertheless, it is essential to appreciate the myriad ways in which the SSMPA is used by members of the general public to instill a profound sense of fear in the lives of LGBT people. This was not the last time that Debbie was assaulted by members of the public simply because of her sexual orientation and gender identity. On December 25, 2014, at approximately 6 a.m. while she was leaving a party in Ibadan, Oyo State, four men stopped her in the street and started shouting, “He’s a fag! He’s a fag!” They proceeded to beat her up and stole all her belongings. Debbie pretended she was dead in order to save herself.

In other cases, family members have initiated mob violence. On July 20, 2014, in a town in Kano, the capital of Kano State, 24-year-old Binta, a devout Muslim, and her female partner were found in the bedroom by her partner’s uncle.[55] The uncle alerted the neighbors. Approximately 20 people gathered, beat the couple, and marched them to the home of the traditional leader of the area. Binta told Human Rights Watch that the group beat them with canes, dragged them on the ground, and insulted them. She told Human Rights Watch that this incident had a profound impact on both their lives. Her partner was disowned by her family. Binta was forced to leave her home in Kano, abandoning her accounting studies. She relocated to Abuja.

In Ibadan, on December 14, 2014, a mob invaded a home and took three suspected gay men, by force, to the local government office, where they were locked up overnight in a shipping container. Desmond, one of the three, told Human Rights Watch what happened the next morning:

The [local government] chairman brought us to the middle of the street and his men beat us mercilessly. They tied our hands and legs to a wooden pole outside.… They had made us take our clothes off that morning. We were in our underwear when they beat us … the whole street was full of people gathered to watch. There were dozens of people watching and shouting, “Beat them! Beat them! Beat the homosexuals!” They were flogging us, beating us mercilessly. Six guys were beating us. They were ordered by the Chairman of the community.… They used rope, canes, wood to beat us. Each of them had a different weapon.… As they beat us, they said, “Say you are gays! Say it!” After the beating my friend fell sick. A week later he died.

The men were released after Desmond’s mother paid 15,000 Naira (approximately $48) to the community chairman.[56]

Efe, a 23-year old gay man and student of Office Technology and Management in Lagos, told Human Rights Watch that on September 1, 2014, he was physically attacked by a man he had met at a party and who knew of his sexual orientation.[57] He said that the man invited him back to his home but when they arrived, he was joined by 20 of his neighbors, all men, and they proceeded to beat him up:

I thought the man was also gay, so I went to his home with him. They were punching me and using sticks to beat me. They tried to extort money from me, but I didn’t have any. They only stopped when an old man intervened. But they took me to the police station, and the man whom I had met at the party informed the police that I had tried to rape him. Even though that wasn’t true, I couldn’t defend myself. My father had to bail me out, and that was when he found out I was gay and disowned me. I was in the hospital for three days with swollen eyes and a swelling head because of the beating.[58]

Sexual Violence

Several interviewees observed that perpetrators of targeted sexual violence against LGBT persons act with a sense of impunity, emboldened both by the apparent license provided by the law, and, perhaps, by the silencing effect of a climate of fear. Also, sexual violence is often at the hands of acquaintances, who are aware of the victim’s sexual orientation. The statements set out below do not suggest that LGBT people did not experience sexual violence prior to the passage of the SSMPA; as indicated above, this reports finds that the law has made a bad situation worse.

Sharon fled from her family home in Kano in early 2014 after her mother expelled her upon learning that she was a lesbian.[59] She sought refuge with a male acquaintance in Abuja, who ended up raping her a week later. “He threatened me that day, and said if I report to the police he would tell them that I am a lesbian,” she told Human Rights Watch. “If the police find out that I am a lesbian they will lock me up for 14 years. So I did not report.”[60]

A representative of a lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (LBT) organization in Cross River State told Human Rights Watch that in 2014, she personally documented three cases (two in Cross River State and one in neighboring Akwa Ibom State) in which groups of two to five men had gang-raped lesbians in the wake of the passage of the SSMPA.[61]

She explained: “In Calabar [Cross River State capital], people now just take the law into their own hands because the SSMPA was widely publicized in the media. And people think it is okay to ‘fix’ anyone who is a lesbian.”[62] She described the three cases to Human Rights Watch. In every instance, the victim did not report the rape to the police or any other legal or medical authorities due to the fear of prosecution and imprisonment under the SSMPA:

- In April 2014, a 23-year-old university student who was visiting her girlfriend was gang-raped by the girlfriend’s two brothers who found them in the bedroom together. The brothers said that the student was corrupting their sister and that “she will enjoy them today.”

- In October 2014, in Akwa Ibom State, her lesbian friend went to visit a woman she had met online. She arrived at the house to find she had been set up and she was attacked by five men. The men kept her locked up for three days, repeatedly raped her, beat her, and recorded the assault. They threatened her, saying that if she reported them to the police, they would send recordings of the sexual assault to her parents and her school, and that if she did not stop her lesbian lifestyle, they would post the videos all over social media.

- In November 2014, in Cross River State, a young woman was visiting her girlfriend when three men, neighbors, arrived at the house and raped her. She believes that this was a set-up. She went to the hospital for treatment of the injuries sustained during the rape, but did not disclose to hospital officials that she had been raped.

The UN special rapporteur on violence against women has noted that in many countries, “lesbian women face an increased risk of becoming victims of violence, especially rape, because of widely held prejudices and myths, including for instance, that lesbian women would change their sexual orientation if they are raped by a man.”[63] Indeed, as The Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERS) notes in its 2015 Violations Report, the perpetrators who raped the young woman Oshodi in Lagos said: “instead of looking for men to love she is loving women and if strong men have sex with her that will change her orientation.”[64]

Other instances of punitive rape post-SSMPA have been reported. Human Rights Watch documented at least five cases in which both women and men were raped in apparent attempts to punish or “cure” them of their sexual orientation. Again, with perpetrators “taking the law into their own hands,” the SSMPA provided cover for this kind of targeted sexual assault.

Human Rights Watch interviewed gay men who reported that they had been sexually assaulted after the SSMPA was passed, by perpetrators who knew about the law. These victims also did not report the crimes. While LGBT people may indeed have been victims of sexual violence prior to January 2014, those interviewed by Human Rights Watch stated that the perpetrators cited the SSMPA during the attacks.

Jason, a gay man in Lagos, met a man through a mobile phone dating app in January 2015, and, after chatting with him, went to meet him at a hotel. However, once Jason entered the hotel room, six men barged in and began beating him. Jason told Human Rights Watch:

I wanted to run, but they told me that the police were outside and if I go out without my clothes on, I’d be caught and sentenced to 14 years because they had caught me in the act. I stayed. The seven of them raped me for three days in the hotel. They took photos and videos of each other having sex with me. They hid their faces, but not mine. They said they would sell the photos and video to a popular blogger…. They did not use protection when they were raping me.[65]

The men also forced Jason to hand over his bank card and PIN number, and then withdrew 45,000 Naira (approximately $148) from his account. Jason did not report the gang rape to the police.

III. Police Abuse of LGBT People

The SSMPA has contributed to an environment in which the police engage in extortion and commit crimes against LGBT people. The law prohibits the “public show of same-sex amorous relationship directly or indirectly,” but the vague wording and lack of clarity about what conduct is actually prohibited means that any person who expresses, or is perceived to express, same-sex attraction in public is at risk of arrest.

LGBT people are fearful of arrest and imprisonment on the basis of their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity and many interviewees reported a new and profound fear of extortion, violence, and abuse at the hands of the police.

Humiliating Tactics during Arrests

At least 17 people interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that they had been detained by the police for the first time in their lives, some of them multiple times, since the passage of the SSMPA. It appears that the SSMPA is used as a tool by the police to humiliate and degrade LGBT individuals, with flagrant impunity, often in the presence of members of the public.

George, an openly gay man from Ibadan, who has been arrested multiple times since the law was passed, told Human Rights Watch that his friend’s mother arranged for them to be arrested in January 2014, just two days before the SSMPA was passed.[66] His friend’s mother telephoned him and asked him to come to the police station. George described how they were humiliated at the police station:

My friend had also been arrested. The police told us to take off all our clothes, and they beat us up. They had a board marked with white chalk: “Gay men arrested.” They told me to hold the board in front of my chest and they took pictures. All this happened in the main lobby area of the police station where members of the public were also present.[67]

George and his friend were detained for three days, during which time the police cursed and beat them up, calling them “idiot gays.” In May 2015, George was again arrested along with 20 other men while attending a birthday celebration in Ibadan.[68] He described what happened when the police arrived at the party:

We were about to start eating when about eight police officers arrived with big machine guns. They tied our clothes together, the ends of our shirts, and marched us to the van, all 21 of us. We were all squeezed into the van, sitting on each other’s laps. Immediately when we arrived at Apata police station [Ibadan], the police told us to take our clothes off. We had only underwear—boxer shorts—on. The police had found a bag of 200 sealed condoms that belonged to a peer educator who was also attending the party. They took the condoms out of the bag, told us to stand in front of the condoms, and gave one of the guys a board written: “21 gay men suspected.” Pictures were taken, the police had called a commercial photographer to take the pictures, but this is normal practice in Nigeria.[69]

Oscar, a 22-year-old gay man from Lagos, told Human Rights Watch that on April 16, 2015, while visiting a friend in Ibadan, he and five of his friends saw police vans, with seven police officers in front of his friend’s house when they returned from church.[70] All six were arrested, beaten up at the police station, told to strip naked, and photographed. They were detained for seven days and only released after the father of one of the detainees paid 200,000 Naira each (approximately $635) to secure their release.

According to Oscar, on their last day in detention, the police loaded them onto the back of an open police jeep and drove them around the city to show members of the public the gay men who had been arrested.

Arbitrary Arrests, Extortion, and Violence

Human Rights Watch found a pattern of arbitrary arrests and extortion in the wake of the SSMPA. In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed several men who had been assaulted and tortured during arrests and detention.

LGBT individuals and members of organizations and networks that provide services and support to the LGBT community reported that they had to set aside funds in order to pay extortion demanded by the police.

A representative of a Lagos-based human rights organization told Human Rights Watch that since the SSMPA was enacted, the organization has paid about 450,000 Naira (approximately $1,450) in bribes to prevent the arrest or secure the release of members of the LGBT community.[71] In nearly all incidents reported to Human Rights Watch, victims and the organizations that support them said they felt compelled to pay extortion fees, or “bail,” due to the threat of 14 years’ imprisonment.

None of the individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch were formally charged with any crime under the SSMPA. For instance, neither George nor his friend, arrested on the eve of the passage of the SSMPA, were formally charged with any offence. He was only released after his family paid “bail” of 20,000 Naira (approximately $64).

Harry, a gay man and peer educator from Lagos, told Human Rights that in February 2015, his 23-year-old friend was stopped by the police in the street in Lagos.[72] The police had gone through his phone and found gay porn videos and nude photos of men. According to Harry:

They took him to the police station. He called me to bail him out. They printed out everything that he had on his phone. I saw it when I went to the police station. The police asked for 200,000 Naira (approximately $635) to “bail” him out. We negotiated it down to 50,000 Naira (approximately $160).[73]

Violence during Arrest and in Detention

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they had been humiliated, physically abused, and tortured by police while in police custody solely because they were suspected of being gay men.

Jason, a 22-year-old gay man from Lagos, said police arrested him at home in August 2015 after a group of men who had previously gang-raped him reported him to the police as being gay.[74] He told Human Rights Watch that police beat him with belts and gun butts and inserted a stick into his anus. He was able to contact his parents, who paid a 78,000 Naira (approximately $250) bribe to get him released.

Human Rights Watch interviewed eight of the 21 young men who were arrested, but not formally charged, at the birthday party in May 2015 in Ibadan. They told Human Rights Watch that at the police station, police beat several of them, including with rifle butts and wooden planks. They were held in police cells for four days wearing only their underwear and eventually released after paying bribes ranging from 10,000-25,000 Naira each (approximately $32-64).[75]

In early 2014, James, a 25-year-old gay man, visited a man whom he met online in Ado Ekiti, southwest Nigeria.[76] When he arrived at the man’s house, a man he believed to be a police investigator was also present.[77] James described what happened next:

Soon after I got there this state investigator friend left. But a little while later he came back with two other guys. The three of them started screaming at us: “Why are you doing this? There are so many ladies in this country, why do you go on being gay?” They kicked us, slapped us, and collected our phones. They asked: “Where is your money?” They got our ATM cards, forced us into their car, and drove us to the bank. They seized my phone, ATM, PIN, and withdrew 35,000 Naira (approximately $110). They took our money and then drove us to the police station.[78]

At the police station, they attempted to report the robbery to the police, but the policeman at the station responded, “Is it true you are doing this? [That you are gay].” The men who had brought them to the police station handed over their phones to the police for the police to search for incriminating “evidence.” According to James, the police slapped them and beat them up with a “koboko” (a whip made of cow skin or horse tail) all over their bodies while shouting, “Tell us the truth! Why are you doing this!?” After three days in detention, and paying another 15,000 Naira (approximately $48) each to the Divisional Police Officer in charge of the police station, they were released.

Abioye, a cleaner at a government office, said that police in Ibadan arrested him in June 2015 on his way home from work.[79] He was taken to Ijokodo Police Station where they proceeded to slap, choke, and punch him, forcing him to unlock his phone so that they could inspect his pictures. They beat him further when they saw pictures of him with his partner. He was detained for three days, and released only after his brother paid police a 45,000 Naira bribe (approximately $142).[80]

In Abuja, in January 2014, shortly after the SSMPA was passed, police raided an HIV services and treatment meeting hosted by Ben, a peer educator. The police arrested 12 of the 24 people attending the meeting.[81]

Ben told Human Rights Watch what happened after they were arrested:

We were held at a police station.[82] There were two cells, six of us in each. They did not give us food or water. At first our friends were scared to come and attend to us. For the first three days we had no food or water. After three days people from my office came to the station and brought us food. We slept on the floor of the police cell; there was no mattress or bed. We were not allowed to make any calls; the police had taken our phones away. We did not have a lawyer. For the first three days the police beat us very badly, they beat all of us, called us names, saying “you are demonic, you’re setting the country back.” They beat us with whips. We were screaming, begging them to stop. Three police officers carrying whips would come into the cell once a day and beat us. They hit me mostly on my back and head. They hit me so much I can’t even say how many times. The beating would last for maybe 30 minutes or more. After I was released I had to go to the hospital for treatment because of the injuries and the malaria that I contracted. The guys I was detained with also had wounds and some got stomach ulcers because we were not getting meals. At the hospital, we could not tell them what happened to us, because if they knew, we would not be treated.[83]

Ben said they all spent three weeks in police custody, without being formally charged with any offence, and finally released after they paid a 100,000 Naira bribe (approximately $318) to the police. On a daily basis, the police would say, “since you are gay, you must pay. How much do you have in your account? Gay men are so rich.”[84] Ben told Human Rights Watch that the SSMPA has provided an opportunity to the police and others to intimidate and extort MSM because they know that LGBT people are afraid of prosecution and 14 years’ imprisonment.[85]

Invasion of Privacy

LGBT individuals reported numerous incidents during which their rights to privacy were violated simply because of their sexual orientation. The SSMPA goes far beyond simply criminalizing same-sex sexual relations. It also prohibits “significant relationships” and “stable unions” between partners of the same sex, dramatically limiting the right to privacy.[86]

In one clear case of violation of the right to privacy, Nathan was arrested in December 2014 in Ibadan simply for being in an apartment with two other gay men: “There were three of us young guys in the flat.… Two of us had gone to visit [the friend who lives there]. The neighbor came over and said, ‘since Goodluck passed the law, we shouldn’t be together in the place.’”[87]

Nathan told Human Rights Watch that police arrested him and the other two men, forced them to strip down to their underwear while in custody, accused them of being gay (without filing any formal charge), and released them four days later after they paid a 20,000 Naira bribe (approximately $64).[88]

Many gay men interviewed by Human Rights Watch said the police cite the law when searching their mobile phones for “evidence” and upon arrest and detention at police stations.

Efe, a 23-year-old gay man from Lagos, said police regularly stop and search anyone who appears to be gay, based on dress or physical appearance. He has been stopped by police in Lagos at least four times, and on two separate occasions, he paid 10,000 Naira (approximately $32) to avoid detention:

They stop us because under the law if you are “suspicious” you must be searched. They suspect you might be gay just by how you look…. They go through your phone and if they see any photos, anything that might point out that you’re gay, they threaten to detain you and you could get 14 years in prison.[89]

IV. A Climate of Fear

The SSMPA has created a climate of fear: it effectively criminalizes public expressions of LGBT identity and the ability of LGBT people to form community organizations, resulting in self-censorship. LGBT interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they feel compelled to conceal their sexual orientation or gender identity because the SSMPA gives members of the public tacit permission to commit acts of violence against them with impunity. In cases where LGBT individuals are victims of crime, they are often afraid to report to the police for fear of being arrested and imprisoned for 14 years.

Self-censorship

We are not free to express ourselves, not free to show who we are. If we express ourselves, we would go to prison for 14 years.

-Darren, 21 years old, Ibadan, October 2015

Hazel, a representative of an LBT organization in Cross Rivers State, told Human Rights Watch that most of the community members are butch[90] lesbians. According to Hazel, one day in June 2014, a lesbian, dressed in masculine clothing, was walking home from school when she was arrested, beaten, and detained by the police for two days. After that she stopped dressing in masculine clothing, and has stopped associating with community members.[91]

Hazel said that a majority of lesbians in Calabar, Cross River State capital, have changed their dress code from masculine to very feminine in order to protect themselves from violence at the hands of the public and police. Other women, who identify as lesbian or bisexual, talked at length about the general pressure on all women to conform to society’s expectations in respect of their sex and gender roles—to get married—and have children—stating that this pressure has increased since the SSMPA was passed.

Sharon, from Enugu State and who identifies as bisexual, told Human Rights Watch that she decided to marry a male friend from high school in July 2015 because of this pressure: “For as long as I am in Nigeria, I will stay married.… If the law was not passed in 2014, I would never have decided to get married.… The law [SSMPA] forced me to make a decision to marry my friend.”[92]

Alice, a 28-year-old lesbian who has lived in Abuja for the past 15 years, told Human Rights Watch that the SSMPA has given her no choice but to marry a man, even though this is not what she wanted:

I heard about the law [SSMPA] the same day it was passed. The law has created a huge sense of fear in our hearts … of the consequences of being found out to be gay. Before the law there was hostility but not so much violence.… I do not want to get married to a man, I am a lesbian, but I will eventually marry a man if the law is not taken away.… I do not have a choice because of this law, it makes me feel like a prisoner.[93]

Mary, a representative of an LBT organization in Abuja told Human Rights Watch that the passage of the SSMPA has led to many women, who were out prior to the enactment, “retreating into the closet out of fear for their safety and security.”[94]

Hazel, the representative of the organization in Calabar, told Human Rights Watch that lesbians are ashamed to talk about the abuse they experience and are afraid of being exposed as lesbians:

Lesbian women do not like to talk about these things that happen to them. It’s too difficult and they feel ashamed. Also, many of the LBT women are afraid of coming to our offices because we share a space with MSM … police are always coming around to ask what is going on in the building.… They feel they would be exposed. So where can they get help? Nowhere.[95]

The SSMPA has also instilled fear in gay men. A 21-year-old gay man in Lagos told Human Rights Watch: “I act very normal and pretend to be straight wherever I go. I have to act normal so that I don’t bring attention to myself. If you don’t act normal, all eyes will be on you and you don’t want that to happen.”[96]

Oscar, one of the 21 men arrested at a birthday party in Ibadan, told Human Rights Watch that after that incident, he decided to start “looking manly” to avoid police attention. He said that he could not bear another arrest and detention for “looking like a gay man.”[97] Another young, gay man who was a victim of the Gishiri village mob attack in Abuja, said that he has had to exercise extreme caution in his home, neighborhood, and in public places:

Within the community there are very effeminate gay men, we tell them to be very careful. My landlord is a policeman and he asked me if I was gay. I denied it. I have asked my effeminate friends not to come to my house anymore. If they come, they are not allowed to leave [until] it is dark because I don’t want the neighbors to suspect that I am also gay. You have to be very careful in the streets: how you walk, what you wear, and how you talk.[98]

Ishmael, also a victim of the Gishiri village attack, lost all his belongings on the night of the attack, fled his home, and now lives in a small village in Abuja.[99] He told Human Rights Watch: “I had to change the way I walk and dress to avoid unwanted comments and harassment. Since that time, I do not feel free to express myself.”[100] Ismael said that since the attack, he has heard people in his neighborhood say, “kill them [members of the gay community].” Ishmael and his friends said that there is no one to help them, no one to protect them, and now they are in hiding.

During the interview with Human Rights Watch, Ismael recalled how, prior to the enactment of the SSMPA, LGBT people would hold regular parties and even pageants. Since the passage of the law, however, the climate of fear has put an end to that. He said that now they cannot even talk about being gay for fear of mob violence, arrest, and the possibility of spending 14 years in prison.

Tom, a gay man from Lagos, told Human Rights Watch that it has been very difficult for men who are effeminate. They have to “tone down,” be less flamboyant, and pretend to be straight. Tom described the situation before and after the SSMPA was passed:

It used to be that people would look at you and say, “He’s gay!” in order to harass you. That’s always been there. But now, people take advantage of the law. It pushes LGBT people to be discrete. I have tried to man up, and be cautious and observant about where I go.

Fear of Reporting Crimes

The SSMPA is an obstacle to accessing justice. For people who are open about their sexual orientation or gender identity, the law represents a direct threat. However, under the law, anyone is a potential suspect based on who they live with or how they express themselves, including what they wear or how they behave.

LGBT victims of crimes, including public beatings, theft, rape, and extortion, told Human Rights Watch that they did not file or report complaints with the police because they feared that they would be treated as criminals under the SSMPA. Several interviewees also cited fear of being outed as a reason not to report offences. Many of those Human Rights Watch interviewed said that this law has created a climate of fear for LGBT people that was not necessarily present or pervasive prior to January 2014, because of the over-broad provisions of the SSMPA. Human Rights Watch does not have information or records of complaints filed by LGBT people with the police prior to the passage of the SSMPA.

Hazel, the representative of an LBT organization in Cross River State told Human Rights Watch that she was aware of cases where lesbians in particular did not report sexual assault to the police.[101] Reluctance to report sexual abuse is especially true for lesbian and bisexual women, who are not only more vulnerable to physical and sexual violence, but also less likely to report abuses than other members of the LGBT community.

Henry, the victim of mob violence in Lagos in June 2014, captured the feelings of many victims: “No way would we file a complaint. When it’s an LGBT issue, you can’t file a complaint.… The police could lie. Then it’s your word against theirs. For the judge, as long as they are hearing ‘gay’.… Forget it.”[102]

Clive, a gay man who lives in Abuja, told Human Rights Watch that since the law was passed, a lot of community members have gone back into hiding because of fear. They had heard about people being beaten up in Abuja and got scared. According to Clive, “people get attacked for being gay but the fear will not let them report this to the police, they are afraid of going to prison. So no one is reporting crimes.”[103]