Summary

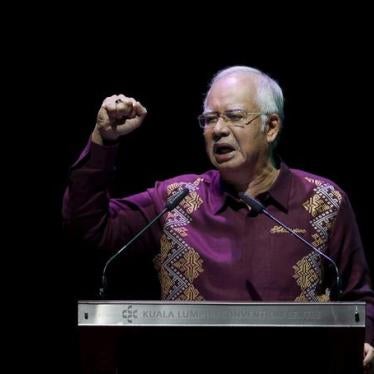

Malaysia’s use of criminal laws to arrest, question, and prosecute individuals for peaceful speech and assembly has deepened in the year since Human Rights Watch published Creating a Culture of Fear: The Criminalization of Expression in Malaysia in October 2015.[1] The Malaysian authorities have moved forward with the prosecutions of many of those featured in that report, and continue to use the overly broad and vaguely worded criminal laws identified there to harass, arrest, and prosecute those critical of the government or of members of Malaysia’s royal families.

The Sedition Act and the Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) remain the laws most frequently used against critical speech in Malaysia. Those criticizing the administration of Prime Minister Najib Razak or commenting on the government’s handling of a major corruption scandal have been particular targets. The long-running corruption scandal involving the government-owned investment fund 1 Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) has prompted calls from politicians, civil society activists, and commentators for Prime Minster Najib to resign from office. Rather than treating such statements as part of normal give-and-take in a democratic society, the Malaysian authorities have treated such speech as criminal, investigating those involved for sedition, “activity detrimental to parliamentary democracy,” and violations of the Communications and Multimedia Act.

Similarly, the government has pursued those making comments on social media deemed “insulting” to Najib or members of royal families with criminal investigations and charges under the Sedition Act, the Communications and Multimedia Act, and provisions of the penal code. The government has also continued to prosecute individuals for exercising their right to peaceful assembly under Malaysia’s overly restrictive Peaceful Assembly Act, and has used the Official Secrets Act to shield reports on the 1MDB scandal from public view.

Rather than amending the laws to bring them into line with international legal standards, as recommended in Human Rights Watch’s 2015 report, the Malaysian government has moved in the opposite direction by suggesting it would strengthen some of the rights-offending laws, particularly those that can be used against speech on social media.

Human Rights Watch reiterates its call for the Malaysian government to cease using criminal laws against peaceful speech and assembly, and to bring its laws and policies into line with international human rights law and standards for the protection of freedom of expression and assembly.

Glossary of Terms and Acronyms

1MDB : 1 Malaysia Development Berhad

Bersih: Coalition for Free and Fair Elections

BN: Barisan Nasional, or National Front

CMA:Communications and Multimedia Act

LTAT: Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera, or Armed Forces Fund Board

MCMC: Multimedia and Communications Commission

MP: Member of Parliament

OSA: Official Secrets Act

PAC: Parliamentary Accounts Committee

RM: Malaysian Ringgit

TMI: The Malaysian Insider

Communications and Multimedia Act

Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) has become the government’s weapon of choice against those criticizing or satirizing the government or Malaysia’s rulers. Section 233(1) provides criminal penalties of up to one year in prison for a communication that “is obscene, indecent, false, menacing or offensive in character with intent to annoy, abuse, threaten or harass another person” (emphasis added). The broadly worded provision has been repeatedly used against individuals alleged to have insulted Najib or members of Malaysia’s royal families on social media, against those calling for Najib to resign, and against an online news portal for posting information about the 1MDB corruption scandal.[2]

Criminal Investigations and Charges for “Insulting” Speech: Najib

In January 2016, after Attorney General Mohamed Apandi Ali announced that he was clearing Najib of any wrongdoing in the 1MDB scandal,[3] graphic artist Fahmi Reza posted on Twitter a clown-face image of Najib with white powder on his face, arched brows, and a blood-red mouth, along with the caption: “In 2015, the Sedition Act was used 91 times. Tapi dalam negara yang penuh dengan korupsi, kita semua penghasut [But in a country full of corruption, we are all instigators].”[4]

The following day, the Police Cyber Investigation Response Center notified him that he had been placed under police surveillance, and police questioned him under section 233 of the CMA and section 504 of the penal code, another abusive law identified in our 2015 report which criminalizes “intentional insults” that are likely to cause the person insulted to breach the public peace or commit some other offense.[5] Fahmi Reza nonetheless continued to use the image, and on June 4, 2016, police arrested him and three others for selling T-shirts featuring the clown-face image, telling them they would be charged with sedition.[6] Two days later, on June 6, police followed through and charged Reza with two counts of violating section 233(1) for his original posts of the image.[7] His case has been transferred to the newly created Cyber Court,[8] established in July to handle cyber offenses, and was pending at the time of writing.[9]

Others who shared the image have also been subjected to police scrutiny. Police called in opposition Member of Parliament (MP) Nurul Izzah for questioning under section 233 after she shared the image on Facebook.[10] In another case in April 2016, police charged Muhammad Zhafiri Zuhdi with violating penal code section 504 (criminalizing “intentional insult with intent to provoke a breach of the peace”) for putting stickers bearing the Najib clown-face image on a police car after a rally protesting the Goods and Services Tax.[11] He has pleaded not guilty and the case was pending at time of writing.

On July 2, 2016, police arrested a 76-year-old man and detained him for three days for allegedly posting an “offensive” image of Najib in a WhatsApp message.[12] Johor police chief Wan Ahmad Najmuddin Mohd said that the man uploaded the image under the name “Pa Ya” in a WhatsApp group titled “Discussion on Malay politics.”[13] At the end of the first three-day remand, the police asked that the man, who was reportedly suffering from diabetes and hypertension, be remanded for an additional period, but the magistrate rejected the application.[14] Extending the use of the CMA to WhatsApp messages that are circulated to a limited and specific group of recipients is a troubling expansion in use of the law.[15]

On September 4, activist Lawrence Jeyaraj was arrested and held overnight for investigation of two Facebook posts that allegedly “insulted” Prime Minister Najib. The following day he was remanded for two days. His lawyer, Eric Paulsen, reported that Jeyaraj was being investigated under section 233 of the CMA and section 504 of the penal code.[16]

Criminal Investigations/Charges for “Insulting” Speech: Johor Royal Family

Social media posts deemed insulting to the Johor royal family are also being treated as criminal expression, with Malaysian human rights group Suara Rakyat Malaysia (Suaram) reporting that at least 13 such cases were filed during the first half of 2016.[17] On June 7, 2016, a court sentenced 19-year-old Mohammed Amirul Azwan Mohammad Shakri to a year in prison after he pleaded guilty to 14 counts of insulting the Sultan of Johor on Facebook.[18] He appealed his sentence as excessive,[19] and the court released him on bail pending appeal.[20] On September 15, the Kuala Lumpur High Court ordered that, instead of a one-year prison sentence, Shakri be sent to a Henry Gurney reform school until he turns 21—effectively increasing the time he will be confined.[21] Football fan Masyhur Abdullah was also arrested and questioned for social media posts criticizing the crown prince of Johor, Tunku Ismail Sultan Ibrahim, and his ownership of the Johor football club.[22]

Police charged activist Khalid Ismath with 11 counts of violating section 233 of the CMA for posts on a solidarity page for Kamal Hisham Jaafar, a former legal adviser to the Johor royal family who was detained on allegations of corruption. Police first arrested Ismath under the CMA on October 7, 2015, and detained him for 3 days. Immediately after his release on October 9, police arrested him under the Sedition Act for a tweet allegedly criticising the detention of 1MDB critic Khairuddin Abu Hassan and lawyer Matthias Chang.[23] He was again remanded, this time for four days. On October 13, he was charged with 11 counts under the CMA and 3 counts of violating section 4(1) of the Sedition Act, and denied bail.[24] He was held in custody until October 29, when he was granted interim bail of RM5,000 per charge, or a total of RM70,000 (US$16,932).[25]

Criminal Investigations for Calling for Resignation of Najib

Those calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Najib over allegations of corruption have also been subjected to criminal investigations under the CMA. Joe Haidy, a blogger who started a Facebook page, LetakJawatan, that has called for Najib’s resignation, was called in for questioning under section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act in December 2015.[26]

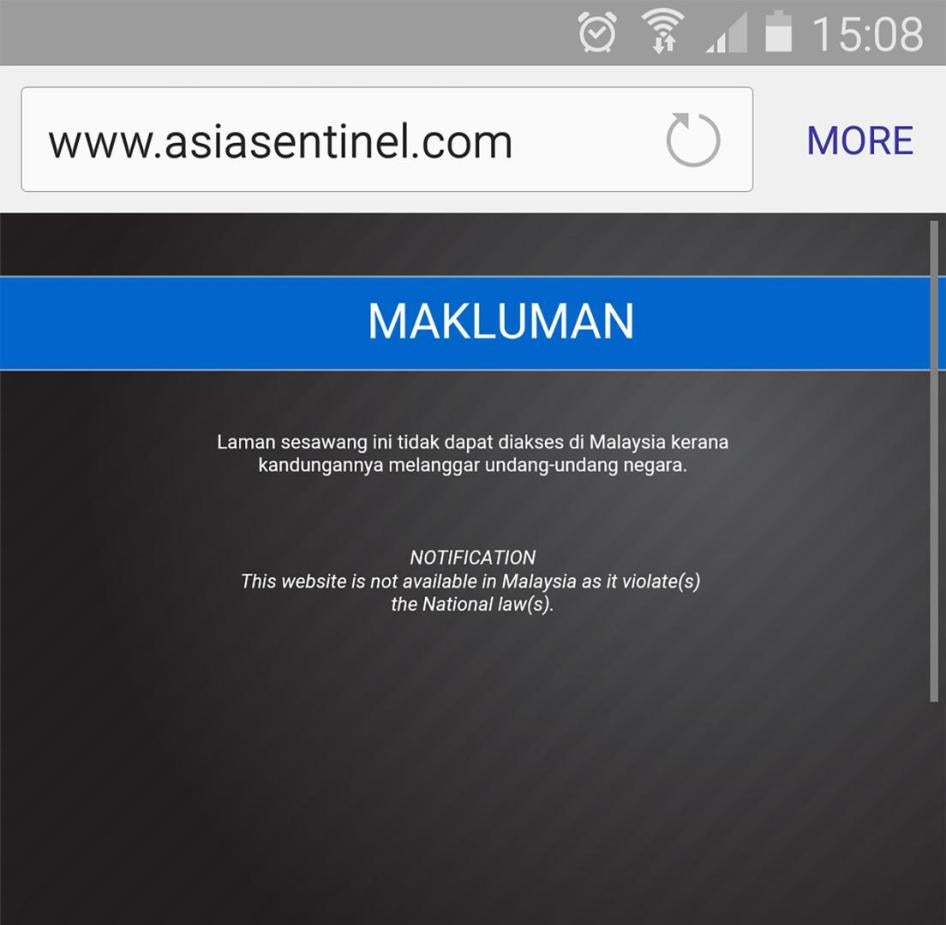

Website Blocking

Although then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed pledged in 1996 to not censor the internet, and Najib repeated that pledge in 2011, Malaysian authorities have repeatedly used the CMA to block websites, including those reporting on allegations of government corruption.[27] In January 2016, the government announced that it had formed a special committee to “tackle social media abuse.”[28] Minister for Communications and Multimedia Sallah Said Keruak said that “stern action will be taken against those who use social media for the purpose of defaming, abusing, or inciting others to belittle the position of or instill hatred towards the institutions of government.”[29]

In March 2016, Deputy Communications and Multimedia Minister Datuk Jailani Johari stated that the special committee had blocked 52 media websites in the first three months of 2016.[30] In total, according to Johari, the government had blocked 399 websites.[31] Since the Malaysian Multimedia and Communications Commission (MCMC) does not appear to maintain a public list of those websites that have been blocked or the reasons why they have been blocked, it is impossible to verify his assertion that the blocked websites “included those on gambling, cheating and prostitution, those with pornographic content, those put up in bad taste and fake.”[32]

However, some of the websites known to have been blocked were reporting on the 1MDB scandal and other political issues. Authorities blocked the UK-based website Sarawak Report in June 2015, and blocked the website Medium, which was posting Sarawak Report’s articles, in January 2016. Authorities also blocked the Malaysia Chronicle, a website reporting on Malaysian political issues that has been consistently critical of the government, the regional news website Asia Sentinel,[33] and several local blog sites commenting on political matters.[34] Sarawak Report, Medium, Malaysia Chronicle, and Asia Sentinel remained blocked at time of writing.[35]

The blocking of TMI’s website prompted an unusually frank statement from the United States Department of State, raising concerns about the Malaysian government’s “actions to restrict access to domestic and international reporting on Malaysian current affairs.”[37] The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) defended the blocking, stating that the government “has a responsibility to maintain peace, stability and harmony in the country and to safeguard the multiracial and multicultural values, norms and practices in Malaysia.”[38] However, the MFA statement did not shed any further light on which articles or content had led to the MCMC’s decision.

On March 14, while it was still blocked by the authorities, The Malaysian Insider shut down, citing commercial reasons.[39] The portal’s editor, Jahabar Sadiq, told the BBC that the site depended heavily on traffic from Malaysia and had been losing money since it was blocked, with advertisers holding off on buying ads until the block was lifted.[40]

The use of the CMA to block access to websites reporting on serious allegations of corruption and other political issues violates not only the rights of those who posted the information, but also those seeking to access information on matters of public interest.

Proposed Amendments to the Communications and Multimedia Act

Despite the existence of overly broad restrictions on expression in the Communications and Multimedia Act, which Human Rights Watch documented in Creating a Culture of Fear, Malaysian authorities repeatedly have called for still greater power to censor social media. On June 26, 2016, Azalina Othman Said, the minister who oversees legal affairs in the Prime Minister’s Department, called for the government to “review and upgrade cyber-related legislation to curb abuses of information technology and the social media.”[41] The authorities have already drafted amendments to the CMA. While the draft amendments have not been publicly disclosed, they are reported to include a requirement that news websites and political bloggers register with the government,[42] increased penalties, and broader powers for the government to take down content.[43]

Sedition Act

The colonial-era Sedition Act 1948, which criminalizes any conduct with a “seditious tendency,” including a tendency to “excite disaffection” against or “bring into hatred or contempt” the government, the king or the ruler of any state, continues to be used to arrest and prosecute critical speech. The law does not require the government to prove intent, and carries a penalty of up to three years in prison, a fine of RM5,000 (US$1,220), or both.

Constitutional Challenges

In October 2015, the Malaysian Federal Court, the country’s highest court, rejected a constitutional challenge to the Sedition Act brought by law professor Azmi Sharom, whom police charged with sedition for expressing his legal opinion that actions taken in peninsular Perak state during a crisis in 2009 were illegal and should not be repeated.[44] Sharom’s primary challenge to the Sedition Act contended that the law had not been passed by the national parliament because it had been carried over from British colonial rule. In ruling against Sharom, the Federal Court went on to state more broadly that the Sedition Act was compatible with article 10 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia, which guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression. The court’s reasoning focused in part on article 10(2)(a) of the constitution, which permits parliament to impose restrictions on the right to freedom of expression “as it deems necessary or expedient in the interest of the security of the Federation.”

The Federal Court determined that parliament, and not the courts, should make the assessment of what is “necessary or expedient” in balancing fundamental rights with security interests. In so doing, the court deferred to a legislature that has recently expanded the government’s powers to crack down on freedom of expression, and considerably limited the judiciary’s own oversight role in safeguarding fundamental rights.

Several other individuals facing sedition charges have also filed constitutional challenges, many of which focus on the lack of an intent requirement in the law. N. Surendren’s application to refer the constitutional question to the Federal Court was rejected on April 14, 2016, with the High Court ruling that the questions he sought to raise had already been decided by the Federal Court.[45] Tamrin Ghafar’s constitutional challenge was similarly rejected in May 2016.[46] Applications by Lawyers for Liberty founder Eric Paulsen, the cartoonist Zunar, and opposition MP Sivarasa Rasiah to refer constitutional challenges to the Sedition Act to the Federal Court are still pending.

Sedition Charges

In the past year, the Malaysian authorities have continued to investigate and file new sedition charges against critics of the government, many of which relate to acts done months before the charges were filed. Many of the cases relate to statements made criticizing the Federal Court decision affirming the sodomy conviction of opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim in February 2015, a prosecution that many observers view as politically motivated.[47]

Recent Sedition Act cases include:

- Mohammad Fakrulrazi, vice president of Parti Amanah Negara, was charged with sedition on September 8, 2015, for calling for the release of Ibrahim at a rally in February 2015.[48] On August 25, 2016, he was found guilty and sentenced to eight months in jail.[49]

- Opposition MP Sivarasa Rasiah was charged with sedition on October 21, 2015, based on statements he made about the imprisonment of opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim at a KitaLawan rally on March 7, 2015.[50] The case is pending, and he has filed a constitutional challenge to the Sedition Act.

- S. Arulchelvan, one of the key leaders of the opposition Parti Socialis Malaysia (PSM), was charged with sedition on November 23, 2015, based on a statement the party issued in February 2015 criticizing the Federal Court verdict in the case of Anwar Ibrahim.[51] Police arrested and held him overnight for investigation on February 19, 2015, but did not charge him until nine months later.[52]

- Activist Lawrence Jayaraj, another person investigated for sedition in February 2015 for criticizing the Anwar verdict, was charged with sedition nine months later, in November 2015.[53] The case is pending.

- Police called in three lawyers for questioning under the Sedition Act after they submitted a motion at the Malaysian Bar’s annual general meeting calling for Attorney General Apandi to resign.[54] At the meeting on March 29, 2015, the Bar voted in favor of the resolution, which called on the attorney general to resign to restore public confidence in the administration of justice in light of his decision to “clear” the prime minister of corruption charges.[55] At the time of writing, the lawyers had still not been charged.

- Azrul Mohammed Khalib, who posted a petition on the website Change.org asking people to sign the Citizens’ Declaration, was called in for questioning under the Sedition Act on April 21, 2016.[56] The Citizens' Declaration was launched in March 2016 by an alliance of former and current members of the longtime ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) alliance, members of the political opposition, and civil society groups, and called for Najib to be removed from office by legal means.

- On April 1, 2016, police arrested former Solidariti Mahasiswa Malaysia (SMM) student activist Ahmad Shukri Kamarudin and detained him for five days for investigation of allegedly seditious statements he made about the Sultan of Johor on Twitter in 2012—four years earlier.[57] Shukri had been detained and questioned regarding the same statements in 2012, but never charged.

- Shazni Munir, a political activist with the opposition Parti Amanah, was called in for questioning on April 4, 2016, regarding an article he wrote for Free Malaysia Today about the impact of the Goods and Services Tax on Malaysians. At the end of the article, he called on people to join an anti-tax rally scheduled for April 2. His comments were then reported in Bicara News as calling for people to topple the Barisan Nasional through “riots,” and the inspector general of police instructed the police to arrest him.[58] After giving his statement to police, the police proceeded to arrest and hold him overnight, then held him for an additional two days.[59] He was released on bail on April 6.[60] Police told him that he was being investigated for sedition and “activity detrimental to parliamentary democracy.”[61]

“Bebas Anwar” billboards

In March 2016, billboards appeared in Selangor state bearing the face of imprisoned opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, captioned “#BebasAnwar” (“#FreeAnwar”) and describing him as a political prisoner. Inspector General of Police Khalid Abu Bakar ordered that the billboards be removed as they “could be considered seditious” and were “aimed at confusing the people.”[62] The police immediately took down the billboards, and then launched a sedition investigation of Azmin Ali, the chief minister of Selangor, for “allowing” the billboards.[63] The police also investigated People’s Justice Party (Parti Keadilan Rakyat, PKR) state assembly member Lee Khai Loon for sedition in relation to statements Loon made condemning the police for unilaterally taking down the billboards,[64] and called in PKR communications director Fahmi Fadzil for questioning.[65] No formal charges had been filed in these cases at the time of writing.

May 2013 Forum Cases

Five of the six individuals charged with sedition for speeches at a gathering on May 13, 2013, calling for audience members to challenge the results of the recently concluded 2013 election were convicted of sedition in separate trials since 2014.[66] The remaining case is still pending. In each case, the authorities took a remarkably punitive position, pushing hard for the imposition of prison sentences.

- Hishamuddin Rais, a 64-year-old activist, was convicted of sedition in January 2015 and fined RM5,000 (US$1,220). The government appealed, arguing that he should be sentenced to prison, and the High Court increased the sentence to nine months in prison.[67] Rais appealed to the Court of Appeals, which ruled on May 16, 2016, that the High Court erred in imposing a custodial sentence.[68]

- Activist Adam Adli bin Abdul Halim was convicted of sedition in September 2014 and sentenced to one year in prison. The sentence was reduced on appeal by the High Court to a fine of RM5,000 in February 2016.[69] The government notified Adli in April 2016 that it was appealing the reduction in sentence.[70]

- Safwan Anang was convicted of sedition in September 2014 and sentenced to 10 months in prison. The sentence was reduced on appeal to the High Court to a fine of RM5000.[71] The government is appealing the reduction in sentence, seeking reinstatement of a prison term. On July 18, 2016, the Court of Appeals adjourned to consider its decision in the case.[72] No decision had been issued at time of writing.

- Haris Ibrahim was convicted of sedition on April 14, 2016, and sentenced to eight months in prison. He is appealing his conviction and sentence, and the government is cross-appealing seeking a heavier penalty.[73]

- PKR MP Tian Chua was convicted of sedition on September 28, 2016. He is appealing his conviction and sentence.[74]

- Tamrin Ghafar’s sedition case is still pending, following the High Court’s rejection of his constitutional challenge to the statute.

The Malaysian authorities dropped sedition charges in two cases that had received considerable international attention.[75] The authorities dropped charges against Teresa Kok for a satirical Chinese New Year video in November 2015, 18 months after she was first charged.[76] Authorities dropped charges against academic Azmi Sharom in February 2016, almost 18 months after he was charged for having expressed his legal opinion that actions taken in peninsular Perak state during a crisis in 2009 were illegal and should not be repeated.[77]

Prosecutions for Peaceful Protests

The Malaysian authorities continue to prosecute individuals for participation in peaceful protests and other assemblies, in violation of Malaysia’s international legal obligations.

Prosecutions for Failure to Give Notice

Human Rights Watch reported in Creating a Culture of Fear that Malaysia was using the Peaceful Assembly Act to arrest and prosecute peaceful protesters for failing to give advance notice of their intent to assemble. On April 25, 2014, the Malaysian Court of Appeals held that issuing criminal penalties for failure to give notice is unconstitutional.[78] As we documented, despite that court ruling the police continued to cite the Peaceful Assembly Act when arresting peaceful protesters.[79]

On October 1, 2015, a different Court of Appeals panel issued a conflicting decision, holding that the criminal penalties were not in violation of Malaysia’s constitution.[80] Five days after the Court of Appeals decision, on October 6, 2015, the government charged Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad, whose challenge to the Peaceful Assembly Act led to the earlier decision holding section 9(5) unconstitutional, with violating section 9(5) of the Peaceful Assembly Act. This is the third time that Nazmi has been charged with violating section 9(5) for the same rally—a Black 505 rally on May 8, 2013, protesting alleged malfeasance during the 2013 general election.[81]

According to Steven Thiruneelakandan, the president of the Malaysian Bar, until the conflict between the two decisions is resolved by Malaysia’s Federal Court, police and the lower courts are normally free to choose which decision to follow, leaving Malaysia’s citizens with no clarity on the state of the law.[82] However, on September 7, 2016, the Court of Appeals ruled that when two decisions conflict, the later decision prevails.[83] Whether or not the Malaysian Constitution allows imposition of criminal penalties for failure to give advance notice of a peaceful assembly, imposition of such penalties violates international legal standards for protection of freedom of assembly.

International norms establish that no one should be held criminally liable for the mere act of organizing or participating in a peaceful assembly.[84] The imposition of criminal penalties on individuals who fail to notify the government of their intent to peacefully assemble is disproportionate to any legitimate state interest that might be served.[85]

Prosecutions for Bersih 4.0 Rallies

The Malaysian authorities have sought to hold the organizers of the large Bersih 4.0 rallies held on August 29 and 30, 2015, in Kuala Lumpur and Kota Kinabalu (in the state of Sabah) respectively, criminally liable for failure to give notice of those rallies despite the fact that, at the time the rallies were held, section 9(5) of the PAA had been held unconstitutional by the Court of Appeals.[86] On October 22, 2015, the authorities charged Jannie Lasimbang, the vice-chairperson of the Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections (popularly known as Bersih) for the state of Sabah and organizer of Bersih 4.0 in Kota Kinabalu, with failing to give notice of that rally.[87] On November 3, 2015, the authorities charged Bersih chairperson Maria Chin Abdullah with failing to give notice of the Bersih 4.0 rally that took place in Kuala Lumpur on the same date.[88]

Abdullah moved to strike down the charges, arguing that, at the time the rally was held, the criminal provisions of the Peaceful Assembly Act had been held unconstitutional. Her lawyers also noted that Abdullah had attempted to provide notice of the rally to the police at Dang Wangi police station in Kuala Lumpur, but the police refused to accept the notice. On April 18, 2016, the High Court rejected her application to dismiss the charges, holding that the second of the two Court of Appeals rulings could be applied retroactively, and that Abdullah had failed to give notice at Brickfields Police Station, where the rally started.[89] The Court of Appeals reversed. In a decision on September 7, 2016, the court held that it was a violation of article 7(1) of the Malaysian Constitution to punish someone for an action that was not, at the time it occurred, a criminal offense.[90]

Despite the September 7 decision by the Court of Appeals, the case against Jannie Lasimberg has yet to be dismissed.

Investigations Relating to Other Peaceful Assemblies

The Malaysian authorities also have continued to call individuals in for questioning for protests that took place months, and sometimes years, earlier. On June 22, 2016, the police recorded statements by Abdul Aziz Bari, Safwan Anang, and Fahmi Zainol about an assembly that took place outside International Islamic University on November 8, 2014. On that date, the university closed off its entrance gates and turned off its lights to prevent an academic freedom talk from taking place inside the campus. Because law professor Abdul Aziz and the other speakers, activists Safwan Anang and Fahmi Zainol, were barred from entering the campus, the students arranged to have the talk take place outside the campus gates.[91] Eighteen months later, the police called the three men in for investigation.

On May 5, 2016, police called in MPs Tian Chua and Sivarasa Rasiah for questioning under section 9 of the Peaceful Assembly Act for failing to give notice of a protest held outside Sungai Buloh Prison on February 9, 2016, to mark the one-year anniversary of the imprisonment of Anwar Ibrahim.[92] Tian Chua reported that he was also being investigated for taking part in a solidarity gathering outside Sungai Buloh Prison that took place on December 6, 2015.[93]

On May 26, 2016, seven months after she held a candlelight vigil for her imprisoned husband Khalid Ismath, police called in Nadzirah Yaakop for questioning under the Peaceful Assembly Act.[94] As of the time of writing she had not been charged with an offense.

Prosecutions for “Unlawful Street Protests”

Section 4(1)(c) of the Peaceful Assembly Act specifies that the right to assemble under the act “shall not extend to…street protests,” defined in the statute as “an open air assembly which begins with a meeting at a specific place and consists of walking in a mass march or rally for the purpose of objecting to or advancing a particular cause of causes.”

Participating in a “street protest” is punishable by a fine not exceeding RM10,000 (US$2,440).[95] As discussed in Creating a Culture of Fear, a blanket prohibition on street protests is a violation of international legal standards for the protection of freedom of assembly.[96]

On September 8, 2015, the Malaysian authorities charged eight activities and opposition politicians under section 4(2)(c) for their participation in KitaLawan rallies in February and March 2015. Bersih chairperson Maria Chin Abdullah was charged together with Bersih secretariat member Mandeep Singh, opposition PKR MP Sim Tze Tzin, and activist Fariz Musa for their participation in a KitaLawan rally on March 28. Police also charged Fariz Musa, along with activist Adam Adli, for participation in a KitaLawan rally on February 28. PKR State Assemblyman Lee Chean Chung, PKR State Assemblyman Chang Lih Kang, and activist Rosan Azan Mat Rasep were charged in relation to the March 21 Kitalawan rally.

All three groups of defendants moved to challenge the constitutionality of the ban on street protests. Those legal challenges were pending at time of writing.

Prosecutions for Unlawful Assembly under Penal Code of Malaysia

On May 31, 2016, almost two years after a June 2013 rally outside the gates of parliament protesting the outcome of the 2013 general election, the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court convicted 15 activists of “unlawful assembly” under section 143 of the Penal Code of Malaysia, of whom 10 were convicted of the additional charge of rioting under section 147. Among those convicted were activist Adam Adli Abdul Hakim, PKR member Badrul Hisham Shaharin, known as Chegubard, and 68-year-old activist Anne Ooi, known as Auntie Bersih.[97] All are appealing their convictions.

These convictions for involvement in the Black 505 rallies rely on the provisions of Malaysia’s colonial-era penal code on unlawful assembly. An unlawful assembly, as defined in section 141 of the penal code, includes any group of five or more people who have as their common object to “overawe” the government or any public servant by criminal force, or show of criminal force, “to resist the execution of any law, or of any legal process,” or “to commit any mischief or criminal trespass, or other offence.” Participation in an “unlawful assembly” can be punished with up to six months in prison, a fine, or both.[98]

While these provisions appear to be directed at violent gatherings, the definition of unlawful assembly in section 141 is overly broad. Assemblies that have as their purpose “mischief”—a term that is subject to wide and varying interpretations—are not necessarily violent, and assemblies intended to “resist the execution of any law or any legal process” could well be peaceful. By criminalizing such assemblies without regard to whether or not they are actually violent, the law violates international norms for protection of the right of peaceful assembly.

Under international human rights law, an assembly should be deemed peaceful so long as its organizers have not professed violent intentions and the conduct of the assembly is non-violent.[99] A non-violent intent should be presumed unless there is compelling and demonstrable evidence that those organizing or participating in that particular event intend to use, advocate, or incite imminent violence.[100] As the United Nations special rapporteur on the right of peaceful assembly has made clear, the right to peaceful assembly is an individual right, so an assembly cannot be considered violent under international law just because a few people in the assembly take violent action.[101]

Similarly, individuals who do not engage in violence or incitement to violence cannot, under international law, be held responsible for the actions of those who do.[102] Section 146 of the law, which deems every participant in an assembly guilty of rioting if any participant in the assembly uses force or violence, is in clear violation of this international legal standard.[103] Where a few people are violent, the police have the responsibility to find ways to apprehend and hold them accountable, using the least disruptive means possible.[104] There is no lawful justification for prosecuting individuals who have not themselves engaged in violent conduct or incitement.

Investigations for “TangkapMO1” Rally

In August 2016, after the US Department of Justice issued a civil forfeiture complaint to seize assets purchased with funds allegedly taken from 1MDB, a group of students organized a rally calling for the individual referred to as “Malaysian Official No. 1” in the complaint and widely believed to be Prime Minister Najib, to be identified and prosecuted. Although the student organizers notified the police of the planned rally as required by the Peaceful Assembly Act, the police declared the notice invalid after Kuala Lumpur City Hall refused to give the students permission to hold the rally in Merdeka Square.[105] Although the police did not interfere with the rally, which took place peacefully on August 27, nine individuals, including TangkapMO1 coalition spokesperson Anis Syafiqah Md Yusof, opposition MP Teo Kok Seong, and PKR Youth Chief Nik Nazmi, were called in for questioning on September 1.[106] According to attorney Melissa Sasidaran, the activists are being investigated not only for violation of the Peaceful Assembly Act, but also for sedition and “activity detrimental to parliamentary democracy” under section 124B of the penal code.

On September 6, the police questioned Bersih chairperson Maria Chin Abdullah and activist Hishamuddin Rais under the Peaceful Assembly Act and section 505(b) of the penal code, another overly broad law that criminalizes statements “likely to cause fear and alarm to the public” that may induce someone to commit an offense against public tranquility, and questioned former Bersih 2.0 co-chair A. Samad Said and PKR MP Chua Tian Chang’s secretary, Rozan Azen Mat Rasip, for violation of the Peaceful Assembly Act.[107]

Official Secrets Act

As discussed in Creating a Culture of Fear, Malaysia’s Official Secrets Act is an outdated, overly broad law that places virtually no limits on what can be designated “secret” and runs counter to the public’s interest in access to information about government activity.[108] In the year since HRW’s 2015 report, the Malaysian government has aggressively used the Official Secrets Act to suppress information about the 1MDB scandal—a matter of great public interest in Malaysia—and to prosecute those who reveal information about it. Faced with ongoing leaks of information regarding the 1MDB scandal, the government has also threatened to increase the penalties under the Official Secrets Act to life in prison.[109]

In February 2016, the auditor-general completed his report on the 1MDB scandal and submitted it to the Parliamentary Accounts Committee (PAC). However, in March it was disclosed that the government had designated the report an “official secret.”[110] Hasan Arifin, chair of the Parliamentary Accounts Committee, told the media that "the federal audit report on 1MDB will no longer be classified a state secret under the Official Secrets Act (OSA) once the PAC tables its findings on it in parliament.”[111] Although the Parliamentary Accounts Committee tabled its findings in parliament on April 7, the auditor-general’s report remained a state secret at time of writing.[112]

The continued classification of documents on a matter of significant public interest, with no demonstration that the disclosure of those documents would threaten national security or public order, is inconsistent with international standards on public access to information. According to the Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information (the Tshwane Principles), a purported national security interest is not a legitimate basis for refusal to disclose information:

if its real purpose or primary impact is to protect an interest unrelated to national security, such as protection of government or officials from embarrassment or exposure of wrongdoing; concealment of information about human rights violations, any other violation of law, or the functioning of public institutions; strengthening or perpetuating a particular political interest, party, or ideology; or suppression of lawful protests.[113]

On March 22, 2016, opposition MP Rafizi Ramli, who was investigating the alleged failure of the Armed Forces Fund Board (Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera or LTAT)[114] to make timely payments to retired servicemen, challenged the government to confirm that the army fund’s involvement as a contractor on a 1MDB contract was not affecting the fund’s ability to pay the servicemen’s pensions on time.[115] Both 1MDB and LTAT denied that the servicemen were not being paid, and denied that 1MDB had any outstanding payments to the construction arm of the army fund.[116] The next day, Ramli alleges, an unidentified person left a document in his office that appeared to be a page from the auditor-general’s report, which Ramli said supports his belief that 1MDB owed significant amounts of money to the army fund. On March 28, he displayed the document at a public news conference, although he did not provide a copy of it to the media.[117]

On April 5, police arrested Ramli at the gates of parliament and subsequently charged him with two counts of violating the Official Secrets Act and one count of criminal defamation. He was charged with unlawfully retaining an official secret in violation of section 8(1)(c)(iii) of the act, and endangering the secrecy of an official secret in violation of section 8(1)(c)(iv). If convicted, he faces up to seven years in prison on each count.

On September 1, 2016, the trial court found that the prosecution had established a prima facie case that Ramli had both possessed and exposed an official secret and ordered him to enter his defense.[118] His trial was ongoing at the time of writing.

According to the Tshwane Principles, criminal cases against those who leak information should be contemplated only if the information disclosed poses a “real and identifiable threat of causing significant harm” to national security.[119] Moreover, public interest in the disclosure should be available as a defense in any such prosecution.[120] Malaysia’s Official Secrets Act, which does not require a showing that the disclosure posed any risk to national security and does not allow a defense of public interest, is in violation of these principles.

Recommendations

Since Human Rights Watch published Creating a Culture of Fear in October 2015, Malaysia’s government has continued to use the many overbroad and abusive laws identified in the report to suppress peaceful expression and assembly. With calls to strengthen some of those laws rather than narrow or repeal them, the situation for activists, political opposition members, and those using social media has deteriorated, harming Malaysia’s democracy and its international reputation.

To reverse that decline, Malaysia should act with urgency to bring its laws and policies into line with international law and standards. The following recommendations include many of those previously set forth in Creating a Culture of Fear, as well as new recommendations regarding the Communications and Multimedia Act, the Official Secrets Act, and the unlawful assembly and rioting provisions of Malaysia’s penal code.

To the Government of Malaysia

- Sign and promptly ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, and the International Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families—all of which contain provisions providing protection for freedom of expression.

- Withdraw proposed amendments to further restrict the right to freedom of expression under the Communications and Multimedia Act

- Amend penal code sections 141 to 147 on unlawful assembly as follows:

- Amend section 141 of the penal code to narrow the definition of “unlawful assembly” to assemblies for which there is compelling and demonstrable evidence that those organizing or participating in the assembly intend to use or incite imminent violence;

- Amend sections 142 and 143 of the penal code to limit criminal prosecution for participation in an unlawful assembly to those who the government can demonstrate used or incited imminent violence;

- Repeal section 146 of the penal code, which deems every participant in an assembly guilty of rioting if any member of the assembly uses unlawful force or violence;and

- Repeal section 147 of the penal code to eliminate the ill-defined offense of “rioting” and prosecute any individual who engages in violence or force during an assembly under the provisions of the penal code dealing with assault or other violent acts.

- Repeal the Sedition Act in its entirety.

- Amend the Communications and Multimedia Act as follows:

- Repeal sections 211(1) and 233(1) or significantly amend them to restrict their application to clearly defined categories of speech that pose a real risk to national security or public order, and where the restriction on speech is proportionate to the risk the speech creates, ensuring that the terms used in the law are clearly defined and limited in scope in order to limit the discretion of local officials in application of the law;

- Ensure that hate speech is only restricted where it clearly constitutes direct and intentional incitement to violence, discrimination or hostility against an individual or clearly defined group of persons in circumstances in which such violence, discrimination or hostility is imminent and alternative measures to prevent such conduct are not reasonably available;

- Ensure that speech that is merely offensive or annoying is not restricted under the law; and

- Ensure that any further amendments to “strengthen” the Communications and Multimedia Act that are proposed by the government are consistent with international standards for freedom of expression, and are drafted in close consultation with SUHAKAM and Malaysian civil society groups.

- Amend The Peaceful Assembly Act as follows:

- Repeal section 9(5) to eliminate the criminal penalties for failure to give advance notice of an assembly;

- Repeal the limitation on street protests in section 4(1)(c) and the 4(2)(c);

- Repeal sections 4(1)(a) and 4(1)(e), which exclude children and non-nationals from the right to participate in assemblies, and sections 4(2)(a) and 4(2)(e), which impose criminal penalties on a non-citizen who organizes or participates in an assembly and on anyone who brings a child to an assembly;

- Amend section 10 to limit the information required to be provided in advance of an assembly to that required to facilitate the assembly and ensure public safety, such as date, time, location and expected number of participants;

- Amend section 9 to shorten the time period for advance notice and to provide an exception to the notice requirement for spontaneous assemblies where it is not practicable to give advance notice; and

- Revise the law to make clear that the police do not have the authority to impose conditions on what is said at an assembly other than to restrict speech that constitutes direct and intentional incitement to violence, discrimination or hostility against an individual or clearly defined group of persons in circumstances in which such violence, discrimination, or hostility is imminent and alternative measures to prevent such conduct are not reasonably available.

- Amend the Official Secrets Act to:

- Narrowly define “official secrets” in accordance with international standards, and limit those who can designate documents to be official secrets to the fewest number of senior officials that is administratively efficient;

- Amend the Official Secrets Act to specifically allow judicial review of classification decisions;

- Amend section 8(1) to criminalize only disclosures of clearly defined categories of documents, to require proof by the government that the disclosure poses a real and identifiable threat risk of causing significant harm to national security, and to allow for a defense of public interest;

- Repeal section 8(2) to eliminate the criminal penalties for receipt or disclosure of information by persons who are not government personnel;

- Amend section 3 to penalize only conduct that the government can establish poses a real risk to national security; and

- Amend section 16 to eliminate the use of “known character” as a basis for showing that the defendant’s purpose in acting was one prejudicial to the safety or interests of Malaysia.

- Repeal section 504 of the penal code to eliminate the criminal penalties for “insulting” speech.

- Amend section 505(b) of the penal code to criminalize only speech that is intended to incite violence or serious public disorder, and clearly define those terms to ensure that they conform to international standards.

To The Minister of Home Affairs

- Establish a clear policy limiting the application of penal code section 143 to participants in assemblies who engage in violent conduct. Participation in a peaceful assembly should never be considered a violation of section 143.

- Instruct the Inspector General of Police to inform all police departments about the specific details of this policy.

To the Attorney General’s Chambers

- Drop all investigations and charges under the Sedition Act.

- Apply to the court to vacate the sedition convictions of Adam Adli, Safwan Anang, Hishamuddin Rais, Haris Ibrahim, and Tian Chua related to speeches they made on May 13, 2013, protesting the outcome of the 2013 elections. Drop the sedition prosecutions of Tian Chua and Tamrin Ghafar for speeches made at the same rally.

- Drop all prosecutions and investigations for insulting speech and establish a clear policy that insulting someone should never be considered a criminal offense.

- Drop all charges and investigations against those who participated in or organized peaceful protests.

- End the abusive use of sections 124B and 124C of the penal code to arrest and charge peaceful commentators and protesters using their right to free expression to demand answers from Prime Minister Najib Razak and his government about the alleged corruption involving state sovereign wealth fund 1MDB.

To the Inspector General of Police

- Cease issuing orders via social media to police to undertake investigations based on tweets, Facebook posts, and other social media content. Remind all police departments that criticism of government and of public officials, including police, is appropriate and lawful in a democratic society.

- Instruct all police departments that peaceful assemblies should not be considered “activity detrimental to parliamentary democracy” and that sections 124B and 124C of the penal code should not be used as a basis to arrest peaceful protesters or those planning peaceful assemblies, or to order them to appear for questioning.

- Instruct all police departments that it is their duty to facilitate peaceful assemblies, not to hinder them. Persons and groups who are organizing assemblies or rallies should be permitted to hold their events within sight and sound of their intended audience, and the police should take appropriate steps to protect the safety of all participants.

- Instruct all police departments to avoid late night or evening arrests of persons charged with crimes unless necessary to prevent flight or the destruction of evidence.

- Instruct all police departments that, unless there is a clear and compelling reason indicating that an individual will not comply with a police summons relating to an investigation, the individual should be permitted to appear voluntarily to give a statement.

- Instruct all police departments that under no circumstances should arrest and remand be used as a form of preventive detention.

To the Malaysian Multimedia and Communications Commission

- Stop using the Communications and Multimedia Act to restrict public discussion of matters of public interest, including the allegations of official corruption and malfeasance regarding 1MDB. Disputes regarding the specifics of information posted online should be addressed in the public forum rather than through blocking access to that information.

- End the block on the websites Sarawak Report, Medium, Malaysia Chronicle and Asia Sentinal and drop any criminal investigations against those websites, their editorial teams, and those who provide content to the sites.

- Pending the amendment of the Communications and Multimedia Act, give clear guidance to your investigating officers that application of sections 211(1) and 233(1) should be strictly limited to speech that poses a real and significant risk to national security or public order.

- Commission officers should be specifically informed that offensive or annoying speech should not be subjected to prosecution, and that hate speech should only be restricted where it constitutes direct and intentional incitement to violence, discrimination or hostility against an individual or clearly defined group of persons in circumstances in which such violence, discrimination or hostility is imminent and alternative measures to prevent such conduct are not reasonably available.

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Linda Lakhdhir, a legal advisor in the Asia Division of Human Rights Watch. It was edited by Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director; James Ross, legal and policy director; and Joseph Saunders, deputy program director. Brad Adams, Asia director, provided additional review. Production assistance was provided by Daniel Lee, Asia associate; Olivia Hunter, photography and publications associate; Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager; and Jose Martinez, administrative senior coordinator.