Summary

Thirty-seven percent of girls in Nepal marry before age 18 and 10 percent are married by age 15, in spite of the fact that the minimum age of marriage under Nepali law is 20 years of age. Boys also often marry young in Nepal, though in lower numbers than girls. UNICEF data indicates that Nepal has the third highest rate of child marriage in Asia, after Bangladesh and India.

In interviewing dozens of children and young people, Human Rights Watch learned that these marriages result from a web of factors including poverty, lack of access to education, child labor, social pressures, and harmful practices. Cutting across all of these is entrenched gender inequality, and damaging social norms that make girls less valued than boys in Nepali society.

Many of the marriages we heard about were arranged—and, often, forced—by girls’ parents, or other family members. In some areas of the country, families marry girls at ages as young as one and half years old. We heard some children describe their unions as “love marriages.” In Nepal, the term love marriage is commonly used to refer to a marriage not arranged by the bride and groom’s families. Usually it refers to a situation where the two spouses have decided themselves to get married, sometimes over the opposition of one or both of their families. Although different from arranged marriages, love marriages among children are often triggered by the same social and economic factors.

The consequences of child marriage amongst those we interviewed are deeply harmful. Married children usually dropped out of school. Married girls had babies early, sometimes because they did not have information about and access to contraception, and sometimes because their in-laws and husbands pressured them to give birth as soon, and as frequently, as possible.

Early childbearing is risky for both mother and child, and many girls and their babies suffer devastating health consequences. Six of the young women we interviewed had babies that had died, and two of them had each endured the death of two of their children.

Our interviews also echoed what research has shown globally: girls who marry as children are more likely to be victims of domestic violence than women who marry later. We interviewed girls who endure constant beatings and verbal abuse at the hands of their husbands and in-laws, girls who are raped repeatedly by their husbands, girls who are forced to work constantly, and girls who have been abandoned by their husbands and in-laws.

The Nepal government has taken some action to stop the practice of child marriage, but not enough. A national plan to reduce child marriage has met with long delays. Protective factors, such as access to quality schools and health information and services, remain out of reach for many children.

This report is based primarily on interviews with 104 children and young adults who married as children, as well as interviews with parents, teachers, health care workers, police officers, government officials, activists, and experts.

We conducted interviews across Nepal. While the majority of interviewees were Hindu, we also interviewed people from Nepal’s Buddhist, Muslim, and Christian communities. Although our interviewees came from a range of ethnic and caste backgrounds, the majority of the married children we interviewed were from Nepal’s Dalit or indigenous communities, a reflection of the fact that child marriage is more prevalent in marginalized and lower caste communities. Due to entrenched and dehumanizing discriminatory practices by both state and non-state actors, Dalit and Janjati communities, as indigenous groups are called in Nepal, are deprived of their basic civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights. Affected communities face severe restrictions and limited access to resources, services, and development, keeping most in severe poverty.

We sat with woman and girls who had married as children—in their homes, under trees, in the fields where they were working—and asked them to tell us about how they ended up marrying as children, and why, and how it affected their lives. We also interviewed family members of married children, educators, health workers, police officers, community leaders, and experts from NGOs working to end child marriage.

Dalit, Tharu, and other indigenous women and girls are particularly disadvantaged in Nepal due to the intersectional discrimination of caste and gender. They suffer from multiple forms of discrimination based on caste, gender and poverty, which make them highly vulnerable to physical assaults, including rape and sexual exploitation, and other crimes which often go unpunished.

Child marriage in Nepal is driven by a complex web of factors, but key among them is gender discrimination, especially when combined with poverty. Discriminatory social norms mean that girls are often seen as a “burden” to be unloaded as early as possible through marriage. This perception is driven by the convention that sons stay with, and financially support, their parents throughout their lives, while girls go to live with and “belong to” their husband and in-laws. This practice creates clear financial incentives for a family to prioritize education and even basic survival needs, such as food, for boys over girls.

Economic and Social Pressures

Poverty was a theme in many of these girls’ lives; many described going hungry, and some parents said they had married off girls because they could not feed them. Some girls said they welcomed a child marriage because they hoped it might mean they had more to eat, a hope that was not always fulfilled.

Social pressures often encourage child marriage. In some communities it is seen as “normal” for girls to marry immediately after they reach puberty; in some areas girls marry even earlier. The payment of dowry, by a bride’s family to a husband’s family, remains widespread, although it is illegal; the expectation that a bride’s family will pay a higher dowry in return for a better-educated husband, or to marry off an older girl, creates financial incentives for child marriage.

In some communities in Nepal, marriages happen in two stages, with a marriage ceremony taking place first, followed some years later by a ceremony called a gauna, which marks the moment when the bride goes to live with her husband and in-laws. This practice is common in communities where children are married prior to puberty; the gauna often takes place after the child reaches puberty. In these situations, however, the first ceremony is not an engagement—it is a marriage, and can be as difficult to dissolve as any other marriage. Children who have married and are awaiting their gauna often described their entire childhood being altered by the knowledge that they were already married, and the gauna often took place while they were still far too young for marriage.

Many girls are married off just after—or sometimes just before—they begin menstruating. Some parents and grandparents believe that they will go to heaven if they marry off girls prior to menstruation. Many more believe that when a girl menstruates for the first time, she is ready for marriage, and that it is in the family’s interest to get her married as quickly as possible to avoid the risk of her engaging in a premarital relationship. Other girls—and boys—marry later in their teens, still too young to physically and emotionally bear the burdens of marriage.

Lack of Access to Education

Quality education provides protection from child marriage—girls who are in school are less likely to marry—but education is a distant dream for many girls. A majority of the married girls we interviewed had little or no education. Often this was because they had been forced to work instead of going to school. Some worked in their family’s homes, but many worked outside the home in paid labor, usually as agricultural or domestic workers, often from the age of eight or nine or even earlier.

Parents are deterred from sending their children to school because the schools are often physically inaccessible as well as perceived as being of poor quality. While the Nepal government aims to make primary education compulsory, and basic education is compulsory according to the constitution, the government does not have adequate mechanisms in place to compel children to attend school. Gender discrimination means that in some communities Human Rights Watch visited, parents often send sons to school, but not daughters, or send only their sons to higher-quality private schools.

The lack of education about sexual and reproductive health is a particular problem. Many of the married girls we interviewed said they had no information about contraception. This lack of knowledge sometimes prompts child marriage. As one activist told Human Rights Watch, girls often rush to marry because they are worried they will become pregnant once they are in a relationship, “even by holding hands.”

Love Marriages

A growing number of children are marrying spouses of their own choosing, sometimes at young ages. We met girls as young as 12 who said they had eloped. Some children interviewed for this report said they chose a so-called love marriage to escape difficult or abusive circumstances.

Others said they eloped because they knew that they were about to be forced into an arranged marriage. These children said they preferred to choose their own spouse but they said their first preference would have been to delay marriage entirely.

Many girls said they faced such deprivation—including hunger—at home that they looked for a husband they thought could feed them. Often, boys and young men seem to have been encouraged to secure a willing young bride by parents who want a new daughter-in-law as an unpaid domestic worker in their home.

Girls who had love marriages also described the impact of rumors and gossip on their choice to marry. When rumors spread about a pair being in a relationship—particularly if the relationship is rumored to be sexual—girls and boys often feel they have no choice but to marry immediately. In some cases, even mistaken rumors prompted a rushed marriage.

Girls who had been sexually active sometimes fell pregnant, or even just feared pregnancy, and rushed into marriages they felt were the only way to salvage their future. With little access to information about sexuality and contraception, especially for children not in school, girls have little ability to understand, let alone control, their own reproductive choices.

Government Action to End Child Marriage

At the July 2014 international “Girl Summit” in London, Nepal’s Minister of Women, Children, and Social Welfare pledged to strive to end child marriage by 2020. By the time the Nepal government held its own national “Girl Summit” in Kathmandu in March 2016, this goal had shifted to ending child marriage by 2030, to align with the 2030 end date of the global Sustainable Development Goals.

At the 2014 summit, the minister presented a five-point plan for how Nepal would achieve this goal. Nepal, like all other UN member states, is also committed to implement the Sustainable Development Goals during the period from 2016 to 2030, which include a target of eliminating “all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilations.”

The government has worked with partners, including the United Nations and NGOs, to develop a National Strategy to End Child Marriage, intended to be a foundation for a detailed National Plan of Action to End Child Marriage with funds budgeted for its implementation. The planned launch of the strategy has been postponed, however, in part because of the disruption caused by the April 2015 earthquake. At the time of writing, it has not yet been launched, although the government “endorsed” the strategy at the March 23, 2016 Nepal “Girl Summit.”

While the Nepal government has taken some important steps to increase access to education and healthcare, the adolescent girls most at risk of child marriage often have little or no contact with the educational and health systems. The government does not have a functioning system to ensure that all children attend primary school. Rates of school attendance, especially for girls, are low in many of the communities we visited, and in spite of government data indicating high rates of enrollment and attendance, a large proportion of the married girls we interviewed had had little or no education. Government health facilities provide free family planning services, but fail to reach many young people—married and unmarried—who need information and supplies. Schools are supposed to teach a module about sexual and reproductive health, but this information fails to reach many of the children most at risk for child marriage—children who are out of school or behind in school.

The government needs to do much more to prevent child marriage and to help married children. It should make good quality education accessible to all children and enforce the constitutional provision making primary education compulsory. Government schools and health workers should work to prevent child marriage, by intervening in specific cases, raising awareness, and equipping children with the information they need to make informed choices about sex and reproduction. Local government offices should play an active role in raising awareness about the law regarding child marriage and preventing child marriages.

Child marriage is illegal in Nepal and has been since 1963. The current law sets the minimum age of marriage at 20 for both men and women. Under the law, adults who marry children, family members and other adults who arrange marriages of children, and religious leaders who perform child marriages are all committing crimes and are subject to prosecution. Arranging a child marriage or marrying a child is punishable by imprisonment and fines, which vary depending on the age and gender of the child involved. These range from six months to three years in prison and a fine of 1,000 to 10,000 rupees (US$9-$94) if the case involves a girl under the age of ten. The lowest penalty under the law is a fine of up to 700 rupees ($6.60) for a person who has finalized arrangements for a child marriage which has not yet taken place.

In many of the communities we visited, however, we saw little evidence of the government working effectively to try to prevent child marriage or mitigate the harm that married children experience. There were few programs to promote public awareness of the problem and where they existed they were often the work of NGOs rather than the government. Police rarely intervene to prevent child marriages, and appear to almost never do so in the absence of a complaint. Local government officials only sometimes refuse to register under-age marriages.

Nepal has pledged to end child marriage and taken steps toward developing a national plan to achieve this goal. But it is time for action. Any effective strategy should address the root causes of child marriage, especially gender discrimination, which is embedded in both social structures and the legal system.

This report, which appears as the government is set to develop its plan to combat child marriage, seeks to support that process with recommendations drawn directly from the experiences of the married children we interviewed.

Key Recommendations

Prevention of child marriage should go hand in hand with broader efforts to empower women and girls, end domestic violence and child labor, and increase access to education and health services. The government should incorporate prevention of child marriage into its efforts to reduce poverty, and take steps to end caste and ethnicity-based discrimination that plays a key role in driving girls into marriage. The government should ensure that all interventions to prevent child marriage and assist married children put the best interests of the child first and never leave children worse off.

To the Government of Nepal

- Reform Nepal’s law prohibiting child marriage to make it more effective. Reforms should:

- include tougher punishments for those who arrange or conduct child marriages;

- remove provisions that discriminate based on gender;

- establish a requirement that anyone conducting or registering a marriage verify the age of the spouses;

- provide support services and compensation to victims of child marriage; and

- increase the statute of limitations for legal action regarding a child marriage until the married child reaches at least the age of 21.

- Ensure that national law upholds international rights and standards regarding child marriage and that these laws are fully implemented by police, courts, and other government officials.

- Prioritize Nepal’s achievement of the target on ending child marriage by 2030 under goal 5 on gender equity and empowering all women and girls in the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals.

- As a follow up to the National Strategy to End Child Marriage, develop and implement the planned National Plan of Action to End Child Marriage through a consultative process with all relevant parts of government and with civil society, community leaders, Dalit and indigenous peoples’ rights groups, faith-based leaders, and young people. Ensure that the plan encompasses prevention of both arranged and love marriage, and consists of detailed plans with clear lines of responsibility across different government institutions, adequate resources, and time-bound and measurable intermediary benchmarks to track progress toward meeting the government’s goal of ending child marriage by 2030.

- Raise awareness of the law regarding child marriage and the harm caused by child marriage, enlist religious, political, and local leaders as partners in preventing child marriage, and take specific actions at the community level to end child marriage.

- Implement a system of universal compulsory birth and marriage registration, ensure registration records are accessible throughout the country, and hold officials responsible if they knowingly permit or register child marriages.

- Ensure that children, especially girls, have access to good quality education and remain in education for as many years as possible.

- Take urgent steps to make primary education compulsory in practice.

- Improve and expand the teaching of education modules for all school children on sexual and reproductive health, and establish programs in all schools to prevent child marriage and keep married children in school.

- Provide necessary information about sexual and reproductive health and risks of child marriage to out-of-school children, especially in marginalized communities.

Methodology

This report is primarily based on research conducted in Nepal in March, April, and September 2015. The report is based on 149 interviews, the majority of them with married children or young adults who had married as children. Using best estimates in cases where interviewees did not know their age, our research included interviews with 38 married children who were still under the age of 18 and 66 young adults under the age of 25 who had married as children. The majority of interviewees were girls and young women, but these numbers include eight married boys and young men who married as boys.

Many interviewees did not know how old they were, or at what age they had married. In these cases, we asked female interviewees when their marriage occurred in relation to the onset of their menstruation, which research suggests is, on average, around age 12 to 13.[1] Girls usually remembered this, even if they didn’t know their age, and it provided clues to the approximate age of marriage for these girls.

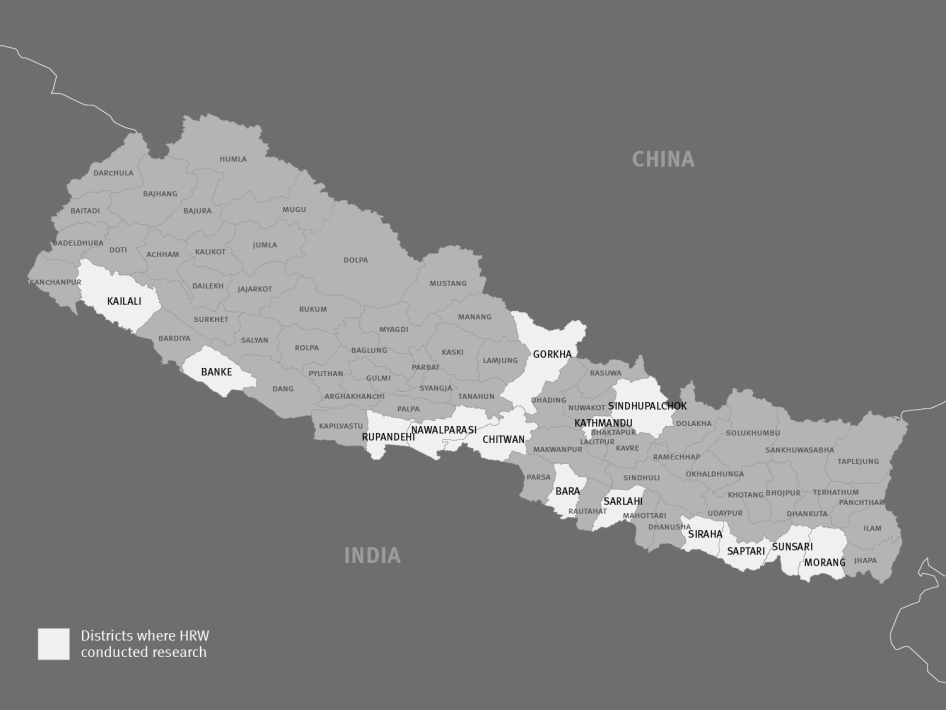

Human Rights Watch conducted interviews in 14 districts—Banke, Bara, Chitwan, Gorkha, Kailali, Kathmandu, Morang, Nawalparasi, Rupandehi, Saptari, Sarlahi, Sindhupalchuk,Siraha, and Sunsari. The majority of the districts are in the Terai region, but we also conducted interviews in two districts in the north of country. These districts were chosen to include interviewees from different regions, and to provide a good sampling across the Terai, where a large proportion of Nepal’s population lives close to the porous border with India. While the majority of the married children we interviewed were from Dalit and indigenous communities, we also interviewed some girls across different religions, ethnic groups, and castes. The majority of interviewees lived in rural and sometimes remote areas, but we also interviewed residents of towns and cities. We also conducted interviews with family members of married children.

A Human Rights Watch researcher conducted interviews with married children and family members in local languages, including Nepali, Hindi, Tamang, Awadhi, Maithli, and Tharu, through a female interpreter. In a few cases, difficulties in interpretation required the use of two interpreters, one from the local language into Nepali and another from Nepali to English.

All interviewees were advised of the purpose of the research and how the information would be used. We explained the voluntary nature of the interview and that they could refuse to be interviewed, refuse to answer any question, and terminate the interview at any point. The majority of interviews were recorded, with the interviewees’ consent, for later reference; all interviewees were given the choice to refuse having the interview recorded. Interviewees did not receive any compensation.

The interviews were usually conducted at the interviewee’s home. They were almost always conducted with only the interviewee, translator(s), and Human Rights Watch researcher(s) present, except in cases when the interviewee’s young child or children were present at the interviewee’s request. In a small number of cases, the interviewee asked to have another person present, a request we accommodated, or a family member insisted on being present. In the latter situations, we modified the interview and did not ask about more sensitive topics, such as family violence or issues relating to sexual and reproductive health.

We identified interviewees and interview locations with assistance from NGOs working in these communities. The presence of these NGOs meant that interviewees were already connected with NGOs with some capacity to assist with obtaining legal, medical, and social services where needed. Many of the married children Human Rights Watch interviewed lacked basic information about family planning and contraception. For these interviewees, Human Rights Watch, in the course of the interview, provided basic information about the types of contraception available through government health posts and referred the interviewee to seek advice and services at the nearest health post.

Twenty-eight additional interviews with government and private health workers and school officials, police, activists, NGO workers, and representatives of the National Human Rights Commission, local and international NGOs, and international organizations provided context and background information. These interviews were conducted in many of the same districts, as well as in Kathmandu. Some were conducted in English; the rest in local languages through an interpreter.

The names of the married children and family members have been changed to pseudonyms to protect their privacy. We have, however, for the most part chosen pseudonyms that match the caste or ethnic identities of the interviewees. The names of other interviewees have sometimes been withheld at their request.

In this report, “child” and “children” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law.

The exchange rate at the time of the research was US$1 = 106 Nepali rupees; this rate has been used for conversions in the text, which have sometimes been rounded to the nearest dollar.

Terminology

This report distinguishes between arranged child marriages and so-called “love marriages”:

Arranged marriages: Typically, arranged marriages are agreed between the parents and other family members of the children, who often have little or no say over whether or to whom they get married.

Love marriages: In Nepal, the term “love marriage” is commonly used to refer to a marriage not arranged by the bride and groom’s families. It refers to a situation where the two spouses have decided themselves to get married, sometimes over the opposition of one or both of their families.

In practice, distinctions between arranged marriages and love marriages are often blurred, and often the same factors trigger both.

I.Background

This is the time for us to sing and play—not look after the house. So I was not happy.

—Mangala Maji, age 16 or 17, and 3 months pregnant, discussing her arranged marriage 6 months earlier.[2]

Globally, 700 million women alive today married as children.[3] One-third of these married before the age of 15.[4] Almost half of all child brides globally live in South Asia.[5] Nepal has the third highest rate of child marriage in Asia, after Bangladesh and India.[6]

In Nepal, both girls and boys are at risk of child marriage, although girls are more likely to be married as children. According to UNICEF, 37 percent of girls in Nepal marry before age 18. Ten percent are married by age 15.[7][8] A 2012 NGO study found that 34 percent of boys marry before age 19.[9]

The prevalence of child marriage varies significantly among Nepal’s many ethnic, religious, and caste groups, with rate of child marriage highest among marginalized and lower caste communities; a 2012 study found that among the disadvantaged Dalit caste, the rate of marriage before the age of 19 is 87 percent in Nepal’s Terai region, and 65 percent in the hills region.[10] Rates of child marriage are also higher among people who have spent fewer years in education, and higher among Muslims and Hindus than Buddhists and Christians.[11]

There are some indications that child marriage amongst some age groups for girls is declining in Nepal. A review of the government’s data, collected through Demographic and Health Surveys, found that between 1995 to 2007, marriage of girls under the age of 14 declined by 57 percent, and by 27 percent amongst girls age 14 and 15 years. The study found that marriage of girls age 16 to 17 increased by 11 percent. These figures combined accounted for an overall decline of 15 percent between 1995 and 2007 in the number of girls marrying before the age of 18.[12]

There are worrying signs, however, that progress toward ending child marriage may be in jeopardy. A 2012 study by Save the Children, World Vision International, and Plan International qualitatively found that some respondents reported that child marriage was on the rise in their area, a change some attributed to the increasing number of love marriages.[13] So striking was this finding that the researchers referred to it as a “paradigm shift.” In the same study, among those who had married early, 15 percent of female respondents and 14 percent of male respondents cited “self desire,” which the report also describes as “love and fulfillment of sexual desire,” as a cause of child marriage. Thirty-two percent of heads of households said that “willingness of children/self desire” was a reason for child marriages occurring in their household.

One of the particularly concerning findings of the 2012 report is that when respondents reported their own age of marriage, marriage before the age of 19 was higher among men age 20-24 than among older men, suggesting that marriages of boys may be increasing. For women, while the rate of marriage before the age of 19 was lower among women age 20-24 than for many of the older categories, there were exceptions; women age 25-29 and age 40-44 had married later than women age 20-24.[14]

Weak Enforcement and a Weak Law

The government needs to be strong. I never heard of a single arrest or of police intervening to prevent a child marriage.

—Primary school principal in Sunsari district.[15]

Child marriage is illegal in Nepal and has been since 1963.[16] The child marriage provisions of Nepal’s general code (the Muluki Ain) were amended in 2002 and 2015 and currently set the age of marriage at 20 for women and men.[17]

Arranging a child marriage or marrying a child is a crime punishable by imprisonment and fines; the law does not distinguish between those who arrange marriages (such as parents and other family members or matchmakers) and those who conduct marriages such as religious leaders. The most serious penalty—for the marriage of a girl under the age of ten—is six months’ to three years’ imprisonment and a fine of up to 10,000 rupees (US$94).[18] The lowest penalty under the law is a fine of up to 700 rupees ($6.60) for a person who has finalized arrangements for a child marriage which has not yet taken place.[19] The law does not impose penalties on officials who register child marriages.

The law provides that any marriage arranged or solemnized without the consent of both spouses shall be void.[20] It also provides that if a girl or boy married under the age of 18 and no children have been born from the marriage, she or he may ask to have the marriage declared void when she or he reaches the age of 18.[21]

Despite legal provisions prohibiting child marriage, enforcement of the law is weak, as attested to by the continued prevalence of the practice.

The problem is not just one of enforcement. In a 2007 joint analysis of Nepal’s law and approach to child marriage, UNIFEM and the Forum for Women, Law and Development identified a number of gaps in Nepal’s legal framework for preventing child marriage. These included:

- inappropriately low punishments for the crime of child marriage;

- wide discretionary power for the courts in determining punishment for child marriage;

- inconsistent definitions of the term “child” across different laws;

- discriminatory provisions in the Muluki Ain which set punishments differently depending on the gender of the married child;

- no requirement that those solemnizing marriages determine the ages of the spouses or at least use reasonable efforts to do so;

- lack of assistance to married children aside from criminal prosecution of those responsible for the marriage; low compensation to victims of child marriage; and

- an unfairly short statute of limitations permitting prosecution only when cases are brought within three months of the marriage.[22]

Dalit and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Nepal

Dalit and indigenous communities face severe restrictions and limited access to resources, services, and development, keeping most in severe poverty. As socially and economically excluded and marginalized communities, the rights of these communities are also compromised including their rights to health, education, water and sanitation, security, political representation, and access to decision-making in state and private institutions.[23]

In Nepal, descent-based discrimination has persisted for centuries, with marginalized communities not just denied fair access to resources, but excluded through practices of untouchability and bias. A decade-long Maoist insurgency from 1996 to 2006 sought, in part, to end entrenched feudal practices. After the conflict ended, political parties committed to reform and an end to discrimination, but years passed without agreement on a new constitution.

Following devastating earthquakes in 2015, on April 25 and May 12, the four main ruling political parties announced that they had broken through a more than six-year deadlock on the formation of a new constitution. The draft constitution, however, was finalized after only one week of public consultation, and failed to address the central concerns of those living in Nepal’s southern Terai region, historically the country’s most marginalized communities, leading to months of protests and violence there.

The new constitution does, however, provide for quotas to assist Dalit and marginalized groups. Implementing policies to end discrimination, and ensuring that those most in need benefit, still remains a challenge.

International Context

Globally, there has been increasing attention in recent years to the need to end child marriage. Child marriage, along with female genital mutilation, was the subject of a “Girl Summit” in the United Kingdom in July 2013, and resolutions on child marriage in the United Nations Human Rights Council and the General Assembly helped pave the way for a successful push by activists to make ending child marriage a specific target in the 2016-2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Sustainable Development Goal Five, “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls,” includes nine targets, one of which is, “Eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation.”[24] The Sustainable Development Goals represent an agreement by all countries to strive to achieve the goals and to make it a priority to do so.

The growing attention to child marriage has been accompanied by greater donor support for work to end child marriage, and a mobilization of aid and civil society organizations working to support this effort. A number of countries with high rates of child marriage, including Nepal, have made commitments to reform. At the 2014 London “Girl Summit,” Nepal pledged to strive to end child marriage by 2020 and has subsequently worked to develop a strategy to achieve this goal.[25] This goal was later changed to ending child marriage by 2030.[26]

II.Factors Driving Child Marriages

In some cases where a girl is 13, she asks her parents, ‘Will you get me married, or shall I elope?

—NGO worker, Morang district.[27]

Poverty, lack of access to education, child labor, social pressures, lack of access to family planning information and contraceptive supplies,[28] and harmful practices including dowry and beliefs about menstruation and virginity typically drive child marriage in Nepal. Many people in Nepal draw a distinction between arranged marriages and love marriages, based on whether the spouse is chosen by the parents or by the child or children. When it comes to the effect on the child, however, as well as the factors driving the marriage, this distinction is often irrelevant.

Many of the factors that trigger love marriages also encourage children to agree to or ask for an arranged child marriage. Across dozens of interviews Human Rights Watch conducted with children who had had love marriages, the picture that emerged was one where the impetus to marry was often abuse, poverty, or coercion. Most importantly, children who choose their own spouses typically experience the same harms as children who have arranged or forced marriages.

Love MarriagesHuman Rights Watch asked many interviewees for their views on the causes of the increased number of love marriages of children. Many blamed modern technology—including mobile phones and Facebook—saying that technology encouraged romantic relationships between children that would not have happened previously. Some saw increased school attendance as giving children more ways to meet potential romantic partners, with love marriages a result. “Now kids just run away. They don’t stay home. They go to school and fall in love and elope,” said an elderly woman in Gorkha, who had married at age 12. “Kids are very free these days. Before they were obedient to what their parents said.” Some children told Human Rights Watch they enter into love marriages because they know that their parents will marry them soon anyway, but they prefer to choose their own spouse. These children said, while they may prefer the spouse they chose to one chosen by their parents, their first preference would have been to delay marriage entirely. “My parents were searching, searching for a groom, and I was in love with someone, so I eloped,” Sunita Lam said. She married at age 16 to a man who was 19 or 20 who she had met over the phone a year earlier when he dialed a wrong number and reached her by accident. “The first time I met him was at our marriage,” she said. Sunita did not tell her family that she was getting married. “They would scold me. My parents wanted me to marry someone they had chosen. There were two or three proposals. My parents liked them, but I didn’t.” |

Poverty and Food Insecurity

We were very poor. We had difficulty finding two meals every day. I was made to work when it was my age to study.

—Ramita T., eloped at age 12.[29]

Many girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch described growing up in poverty so severe that their families sometimes saw child marriage—marrying off their daughters as early as possible—as a means to try to ensure the survival of the rest of the family in the face of hunger. “People have a lot of kids,” an NGO worker in Morang district said. “They think it’s better to get her married, not keep her here and have to feed her.”[30]

“My daughters were okay with getting married because our situation was not good at home,” Rama Bajgain said, discussing why she arranged marriages for her daughters when they were 15 and 16 years old. “They thought they might get a better life with proper food and clothing after marriage. It was not forced marriage. There was no income, only expenditures in the form of four kids. I would work for 12 and a half rupees (US 12 cents) per day. When I fell sick they would all go hungry. Everyone saw what I went through.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed Rama next to the ruins of her house, which she said had taken her 31 years to build; it was destroyed in the April 2015 earthquake. Rama doesn’t think they’ll be able to rebuild it. She and her husband and their two sons are now living in a shed with the family’s buffalo.[31]

Some of the girls interviewed who had entered into love marriages said they had done so as an economic survival strategy.

For some girls, marriage did mean they were more likely to have enough to eat. “Life is better here,” Khushi Sarki said about her in-laws’ house. She is 15 or 16 years old, has been married for five years and has two children. “At my parents’ house, there was not enough food. We were very poor. Here we have some land to cultivate so at least we can eat.”[32]

Although tradition typically dictates that a bride goes to live with her husband and his family, in some situations a child marriage can be a way to bring another wage-earner into the home. Khushbu Kumari married at the age of 13. She is the oldest of six girls. Her father is a rickshaw puller and was struggling to support the family. “My husband’s parents were dead. He came to this village and looked for a wife by himself. My parents said, ‘We are already poor,’ but he said, ‘I will work and give you what I earn” Khushbu said. Khushbu’s husband works as a laborer; his wages have helped keep the family afloat.[33]

Parents sometimes saw marriage as a way to protect their daughters when illness or other life circumstances threatened the family’s financial situation.

“I did not want to get married, but I had to because there was no one to take care of me,” Babita Tharu said. “My mother went to live with her second husband and his first wife, so she couldn’t keep me along,” Babita said. “So my father married me off. We had no food and no proper clothes to wear.” Babita married at age 13 to a man who was about 19. He and his parents are abusive to her.[34]

Even love marriages are sometimes prompted by a parent’s illness. “My father-in-law was sick—that’s why he wanted to get his son married as soon as possible,” said Sarala Pariyar, who was about 16 and in class eight when she married a boy she had met through her sister. The couple eloped after Sarala’s parents refused to let her marry.[35]

Lack of Access to Education

“I didn’t want to get married—I wept a lot when my father said I was getting married. But there was no education. My father had a lot of goats and those goats were our only education.”

—Rama Bajgain, married at age 16.[36]

Research in 18 of the 20 countries with the highest rates of child marriage has shown that a girl’s level of education is the strongest predictor of her age of marriage.[37] Around the world, girls with more education are less likely to marry as children; for example, girls with secondary schooling are up to six times less likely to marry as children than girls with little or no education.[38]

Nepal has historically had low rates of education and literacy. The government says that 44 percent of women and 23 percent of men never attended school.[39] Fifty-six percent of women and 28 percent of men lack the education to read a simple sentence, according to the government.[40]

The situation is improving, but for children growing up today access to education remains limited. Although Nepal’s constitution states that “Every citizen shall have the right to get compulsory and free education up to the basic level and free education up to the secondary level from the State,” there are no effective mechanisms to compel children to attend school. According to one set of Nepali government data, over 95 percent of children enroll in primary school, but in another set of data from 2010/2011, the enrollment level is significantly lower at 78 percent.[41] Government data indicates that 70 percent of children who enroll in school complete primary education, and 60 percent of children attend secondary school.[42] Poorer children were more likely to be deprived of education, with 76 percent enrollment in the poorest quintile versus 83 percent in the richest.[43] Children in the Terai (72 percent enrollment) were more disadvantaged than children in the mountains (88 percent) and hills (85 percent).[44]

The World Bank raised some doubts about the accuracy of government data in its 2015 review of the government’s education reform program, writing, “Verification of the current system suggests irregularities in reporting data…the incentive to over-report enrollment data has increased with the introduction of per capita financing.”[45]

Many married girls described the connection between leaving school and getting married. “I had stopped going to school and was just staying at home,” Sitara Thapa, who had an arranged marriage at age 15 said. “So my parents thought why have her just stay home, and married me off. I didn’t want to get married.”[46]

Girls who had love marriages also often pointed to lack of access to education as a cause of their decision to marry early. “If I had studied I would have known better—I would have known about marriage and everything,” said Kamal Kumari Pariyar, who was forced to leave school at age 10 to become a domestic worker and then eloped at age 13.[47] A large proportion of the married girls interviewed for this report had little or no education. The most common reason for not attending school was that poverty had forced them to work instead. Other reasons that interviewees gave for girls not going to school included discrimination against girls within both families and schools, poor quality education in government schools, corporal punishment in schools, costs associated with education, and lack of water and sanitation facilities in schools.

Poor Quality Education and the Impact of Gender Discrimination

Many parents cited what they saw as poor quality of education in government schools as a reason that they—or their children—had not attended. The perception that government schools do not deliver adequate education drove some parents to make great efforts to try to pay for their children to attend private school instead, particularly in favor of boys.

“Children don’t actually learn anything in government school,” said Sitara Thapa, who left school at 13 and married at 15, explaining why she and her husband, who works as a cook in India, are struggling to raise the money to send their young daughter to private school.[48]

The government’s own assessment supports this view. In 2015, the Ministry of Education wrote that “key quality concerns” included “poor infrastructure, poor and unprofessional management, lack of learning, resources (even textbooks are not available on time), diversity of student background in terms of culture, language, economic conditions, discriminatory social contexts in terms of caste and ethnicity, and most importantly lack of child friendly environment… [S]erious problems and challenges stand in the form of grade repetition, drop out, cycle completion, and learning achievement.”[49]

A number of the married girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had attended school briefly—sometimes for as little as one day—and then left because they had been hit and beaten with sticks by teachers.

Parvati Satar said she went to school for only two or three days. “My teacher beat me, so I ran away,” she said. “I never went back. My dad used to say, ‘Go to school, go to school.’ But I never went. My dad beat me, but even then I didn’t go.”[50]

Discrimination against girls means that often boys have more access to education than girls. “Only my brothers went to school,” said Sapana K., who married at age 10 or 11. “I never went to school—not for one day. My family was poor so I had to look after the home.”[51]

Gender discrimination also means that when girls have access to education, it is often of poorer quality than that provided to boys. "My brother studied in private school. Me and my sister went to government school, because of discrimination between sons and daughters,” Shabnam Poudel, who had a forced marriage at age 18, said.[52]

A headmaster of a government school in Sindhupalchuk said that girls outnumbered boys in his school significantly, with girls making up 58 percent of the students from nursery to class ten. He explained, however, that this should not been seen as a mark of progress for girls, but actually the opposite. “It is our tradition to give more importance to boys, so they go to private school and to Kathmandu to study,” he said. “So it’s the girls who are left in the local government school.”

The government’s failure to provide good quality public education for all children, and the resulting desire by parents to try to send their children to private school even if doing so is beyond their financial means, exacerbates disparities between the quality of education received by girls and boys.

There was some optimism that these disparities are declining over time. The principal of a private primary school in Sunsari district said that in the ten years that his school had operated, the number of girls attending had increased over time from zero to currently 40 percent of the student body. “People thought spending money on girls’ education is spending money on nothing,” he said. “But slowly people are becoming aware of girls’ value and the value of education for girls.”

Costs Associated with Government Schooling

Some families also struggled to meet costs associated with sending a child to a government school, in spite of the fact that under government law and policy, as well as international law, primary education is meant to be free.

“My father stopped my schooling because he could not afford my fees, stationery, and uniform,” Kalika Majhgainya, age 16, who studied to class 6, said. She said she asked her father not to get her married and offered to stay at home and work if she could not go to school, but he refused. She married at age 14.[53]

“The school asks for money for everything—for enrolment, for stationery,” said Antara Chamar, who decided not to send her seven children to school. “There is no facility in the school, no education, no clothes, so no incentive to go.”[54]

Managing Menstrual Hygiene

When girls do attend school, they are at increased risk of dropping out as they reach adolescence. One reason for this may be stigma attached to menstruation, and a lack of water and sanitation facilities at schools that would make it easier for girls manage their hygiene during menstruation without missing school days. Research suggests that in some areas up to thirty percent of girls in Nepal do not attend school during their menstrual periods, creating major and repeated gaps in their attendance and making them more likely to leave school entirely.[55] Only 36 percent of schools in Nepal have separate toilets for girls.[56]

“The government should build toilets in schools,” said Chandni Rai, age 19. “We had a toilet, but it was not good. If there are proper toilets, girls will feel better when they are on their periods and have to change their pads. Many girls stay home during their periods. They were marked absent and wouldn’t be able to learn. They couldn’t catch up because the course would have moved on. They would try to sit with their friends and catch up, but the teacher wouldn’t repeat [information]. Some of them left school because of this. Some got married then, some did not.”[57]

Nepal also has harmful practices associated with menstruation that contribute to pushing girls out of school. Traditionally, girls and women during menstruation are considered unclean and are forbidden from touching or mingling with other people. In some communities in the far- and mid-western regions of the country, a more extreme version of this exclusionary tradition is practiced. As many as 95 percent of families in these regions practice chaupadi, where women and girls are confined to a shed during menstruation. In addition to often being banned from the home entirely, women and girls in families that practice chaupadi face many other restrictions during menstruation, sometimes including being barred from school. Even when not barred, girls often face social and family pressures to stay home during menstruation.[58]

Child Labor

The most common reason married children gave for having not attended school was that they had to work instead. “Parents ask their kids to go and earn rather than study,” a NGO worker in Kailali said.[59]

Child labor is common in Nepal, with about 40 percent of children working, the great majority in rural areas.[60] While not all work by older children is harmful or illegal, in Nepal two-thirds of working children are below the age of 14, and half of working children are in occupations likely to interfere with their education or be harmful to them.[61] Girls are more likely to work than boys (48 percent versus 36 percent) and 60 percent of children in hazardous work are girls.[62]

“I could have gone to school and understood [the lessons] if I wasn’t so tired from working,” Lalita Thapa, age 17, said. She married at age 15 or 16, and left school at age 14. “When you’re a girl, you have to work. I started working at age 12.”[63]

Many girls were kept at home to do housework and look after siblings.

“I was a good student—I never failed in class,” said Sovita Pariyar, age 17, who left school when she was in class 5. “But I couldn’t continue as my mother was ill and my sisters were married. I had the responsibility of the house.” Sovita never returned to school and she eloped when she was about 15 years old and was eight months pregnant at the time of the interview. “I feel sad when I see children going to school,” she said. “I wish I could go to school.”[64]

Other girls were sent out to do agricultural work for often little pay from young ages. Some were only paid in crops. “I had to work from quite young as a farm hand—from age six or seven,” Khushi Sarki, who never went to school and married at age 10 or 11, said. “I was paid in rice—one day [of work] for one kilogram of rice.”[65]

Other children were sent to be domestic workers, sometimes far from home. "We were so poor I worked as a servant just to feed myself,” said Babita T., who married at age 11. “I started working when I was eight or nine. I looked after a baby. [My employers] said I could go to school too. But when I got there they never sent me.” Babita earned 400 rupees (US $3.77) a month, which she gave to her father, who did not work.[66]

A daughter-in-law is often seen as a free domestic worker, and with depressing frequency girls who said they had entered love marriages described their husband’s parents urging their son to secure a bride to do the work in the home. Women and girls often bear all or most of the responsibility for domestic labor in the household, including cooking, cleaning, caregiving, fetching water, washing clothes, and other work that is typically time-consuming, unpaid, and undervalued. Domestic work can be particularly backbreaking in rural areas with few facilities, such as running water. In many Nepali families, the brunt of domestic work customarily falls to young daughters-in-law.

“I used to go to my father-in-law’s house to cook for them, because they had no one to help them,” said Rita Tharu, age 17, who eloped at age 16, with a man who was 21 years old. “When I came back, my father said, ‘I won’t let you go there again,’ so I had to run away. My mother-in-law used to go and work in the daytime, and my husband only had a younger brother, so my husband’s family was looking for a daughter-in-law. I eloped and he brought me to his house. I was in class five, but I left because I got married—I had to work in the house.”[67]

For some girls, their family’s livelihood was produced in the home and they participated from a young age.

Rojina Chamar said she started helping to weave baskets when she was three or four years old. “Within two or three years, we are handed the knives to start working,” she said. She grew up as one of eight children in a family of basket weavers. She doesn’t know when she married, but her gauna [a ritual marking the moment when a girl goes to live with her husband] was when she was nine or ten years old. She said: “They never sent me to school. They tossed me this bamboo weaving and we were poor, so I learned this rather than going to school.”[68]

Children who were orphaned or abandoned by their parents were especially likely to have to work from an early age. Nikita B. began working as a domestic worker at age eight, after her mother died and her father remarried, leaving Nikita to care for her two younger brothers. “I was paid 500 rupees ($4.72) per month,” Nikita said. “My father took that. I took my brothers wherever I worked.” Nikita never attended school. When she was 13, her maternal aunt arranged a marriage for her to a man about ten years older than her.[69]

For some girls Human Rights Watch interviewed, marriage seemed like the best option to escape harmful labor. “My father used to drink a lot and used to tell me to go and work in bad places and I used to refuse because it was dangerous and I could be raped,” Kamala Kumari Pariyar said. Her parents forced her to leave school and work as a domestic worker at age 10. At age 13 she eloped.[70]

Social Pressures and Harmful Practices

My parents were afraid I would run away—or that people would talk and say ‘She’s grown up.’ Parents think if girls grow up [without getting married] they run away or get pregnant. If parents are educated and girls are also educated, it will help in this matter.[71]

—Binita Khan, who married after her first menstrual period.

Discriminatory gender roles and social pressures drive child marriage and are an obstacle to ending it. Tradition usually dictates that boys remain with—and financially support—their parents, while girls who marry join their husbands’ family. This tradition encourages families to prioritize education, support, even food, for sons over daughters, and even to try to avoid having daughters.

Marriage Immediately or Soon After Puberty

As soon as a girl grows up, she has to be married off—as soon as she has her period.

—Sarika Khatun, who had an arranged marriage after her fourth or fifth menstrual period.[72]

There is a perception in some families and some communities that the onset of puberty means that it is time for a girl to marry and many girls are married soon after they begin menstruation. Often, parents see marriage as a way to prevent risks they associate with the onset of their daughter’s puberty, for example that she will form a romantic relationship, have sex, become pregnant, or elope. “In my society if a girl is young, people think she might elope or do something wrong, so she should get married,” said Jyoti Atri, who had an arranged marriage at age 17.

Sometimes the choice of a child bride is explicitly about ensuring virginity of the bride.[73] Rekha Kamat accepted a proposal from a 25-year-old neighbor to marry her 14-year-old daughter. “He said his parents were pressuring him to marry and had even found some girls,” Rekha said. “But they were older and might have had an affair or even been engaged before or had an abortion. So he wanted a younger girl. We got her married because it would be easier for her future—so she wouldn’t have any affair or elope. I’m satisfied that I managed to prevent her from having an affair.”[74]

The stigma attached to premarital romances is accompanied by even deeper stigma regarding premarital sex. In this environment, unmarried girls and boys have great difficulty obtaining the information and contraception they need to prevent pregnancy, and when girls become pregnant, they often feel they have no choice but to marry immediately.

Ritu Malik had a love marriage with a classmate when she was 15 years old and three months pregnant. “I hadn’t even thought about marriage—I got married because I was pregnant. I had studied a unit in school on family planning, but I had no idea how to do it. We were taken to the hospital for a demonstration [of family planning] but I didn’t go because I felt ashamed. If I could have avoided getting pregnant, I would still be studying.”[75]

So urgent is the rush to marry in the event of a suspected pregnancy, that a couple may not even take the time to confirm it. Purushottam N., age 18 or 19, had eloped a year earlier with a girl who was 15. “There were rumors in the village and it could be a problem for the girl’s family,” he said. “The girl said to me that she was pregnant—it was a lie. So we had to run away. Four or five days after we ran away I knew she wasn’t pregnant. I didn’t want to get married, but the conditions made me.”[76]

Young people also sometimes see early marriage as a necessary—and desirable—step to allow them to deal with sexual urges. “People listen to their friends and run away,” said Rita Pariyar, whose parents agreed to her marriage at age 17 to a boy that she had chosen herself. “Friends say, ‘If you marry you can run away and have sex with your husband and it’s so good.’”[77]

Beliefs about the “right” age to marry can also affect boys. Naveen A. married at age 13 to a bride about a year younger. “I did not want to get married and I told them that, but they got me married,” he said. “It’s like this in our community. I was the only son and my parents were getting old. They said they wouldn’t want to die without seeing their daughter-in-law.”[78]

Beliefs about the impact of puberty on a girl’s behavior and a view that marriage is a way to prevent girls from bringing shame to their family are sometimes mixed with religious beliefs.

“Older people think they will go to heaven when young people get married,” said Ramila Kumari, who married at about age 12 to a man who was 22. “My grandmother’s wish was to see her oldest grandchild married before she died. She thought she would die [soon]. My grandmother really forced my parents to get me married.”[79]

Even adults who said that they opposed child marriage often meant only the marriage of young children, and advocated that girls be allowed to marry well below age 18. A community leader who proudly described his work to try to prevent child marriage told Human Rights Watch, “I personally tell every village that to marry at age 12 to 14 is child marriage. It’s okay to marry at 15–you are no longer a child then. The right age of marriage is 20 for boys and 15 for girls.” [80]

Marriage Before Puberty

My parents kept telling me I was married—and also to be careful because I was married. They meant to warn me not to like other boys.

—Pinky Kumari, married at age three or four years old.[81]

Some children in Nepal are married when they are still small children. These marriages may be motivated by a desire to avoid dowry, a fear that it may be difficult to find a husband for a daughter later on, or by social pressures in communities where this practice is common.[82] While we encountered only a few of these cases in our research, they were some of the most shocking examples of how harmful practices relating to marriage can rob children not only of their freedom and safety from early adolescence on, but also throughout their entire childhood.

“I don’t even remember when I was married,” said Kanchan Kumari. She is 15 or 16 years old now, and married at age three or four. She came to live with her husband after a gauna when she was nine or ten years old, and has two children and was seven months pregnant with a third at the time of the interview.[83]

“My mother told me I was crying a lot at my bride’s house [the day of my wedding],” Narendra Chamar said. “People brought me to [my mother to] breastfeed and then took me back to get married.” Narendra was one and half years old at the time of his wedding and his wife was six months old. “It’s a tradition in this caste to get married very early,” he said. Narendra said he was ten years old before he understood he was married. When he was 16, his bride came to live with him and they met for the first time since the wedding. “I was scared,” he said. “The bride came in, and I ran away to Delhi for three or four months. But then family and friends said, ‘You are married. You can’t get another wife. You have to come back.’ So I did.”[84]

Sometimes the same rationale that is used to justify marrying a girl as soon as she reaches puberty—that she might have a relationship or elope—is used to justify marriages of girls approaching puberty. “Whoever has a daughter in their house has to worry,” said Kamlesh Devi Sarki, whose parents arranged a marriage for her almost two years before she began menstruating. “Parents are afraid that she would run away with a guy.”[85]

Although children who are married early often do not begin living together until the bride has commenced menstruation, the fact that they are married typically casts a shadow over their entire childhood. “My parents kept telling me I was already married, so it stuck in my head,” Sushma Devi C. who married when she was four years old said.

In some communities, families believe that there are spiritual benefits to marrying girls before they reach puberty.[86] “In my culture, there is a norm that if you get married before you get your period, you will go to heaven,” said Pramila Pandey, whose marriage at age 14 was arranged by her parents.”[87] “I married at age 13 because it’s a tradition in my caste—giving away a virginal girl,” said Ranjita Bishwokarma, who began menstruating a year after her marriage. “Then [my father] becomes eligible for heaven. He has to do this with all of his daughters.”[88]

The social pressure in communities where early marriage is practiced means that girls sometimes believe that early marriages are to their benefit.

Antara Chamar, age 45, is the mother of 7 children, ranging in age from 10 to 28 years old. She married off all of her children at ages ranging from 2 to 5 years old, as was normal in her community. She says these early marriages were stopped, however, starting about five years ago. “We have a committee that has prohibited us from getting married early—they issued an order,” she said. “A journalist came and got some people arrested for child marriage. Now they get married at 28 or 30 years old.” Antara welcomes the change. “My kids got married early, but my grandkids will not get married early,” she said. “One of my daughters got married and her husband left her. If they were older, they could talk and solve problems.”[89]

A health worker in Sarlahi district said that early marriages had been a regular practice in the community his hospital serves, but they were becoming less common. “People are still getting married very young, but even for them it has changed. They used to get married at birth or just after. Now it is a bit later—but still too early.”[90]

Quashing Rumors and Gossip

Stigma regarding pre-marital sex in Nepal, especially for girls, means that families can be deeply invested in controlling girls’ sexuality, and rumors can have enormous destructive power in shaping a girl’s future.

A number of girls who had love marriages described the impact of rumors and gossip on their choice to marry. “My mother-in-law spread rumors about me. She wanted someone to work in the house. I refused my husband’s advances, so she thought by spreading rumors, I’d be forced to marry him,” said Rajita T., who had what she described as a love marriage when she was 12 or 13 and her husband was about 18 years old. Rajita said that her marriage has been difficult and her mother-in-law abusive. “I would not have married him at any cost ever if that rumor had not spread,” she said.[91]

Even a friendship between a girl and a boy can lead to gossip and abuse. Sanjita Pariyar was friends with a boy a year older than her. She is high caste and he is lower caste. “The teachers would call me out of class and say, ‘He’s lower caste—you shouldn’t talk with him or be seen with him.’ They used to beat me with sticks and pull me out of morning assembly and beat me in front of my friends. They said, ‘We’re doing it for her own good because she’s going around with a lower class boy.” Sanjita said that when this abuse started, she and the boy were only friends, but over time they became romantically involved and decided they needed to elope. “My future changed because of these teachers. I don’t wish this on anyone else.” Sanjita was 15 when she married and said if she hadn’t felt pressured to marry and harassed in school, she would have waited to marry until after she had completed all of her studies and become financially independent—and she suspects she would have married someone else she met in the course of her studies, not her present husband.[92]

Many young people described carrying on relationships secretively, but when others become aware of, suspect, or even spread false rumors of a relationship, young people sometimes feel they have no choice but to swiftly marry.

Parbati Rai struck up a gradual romance with the pastor of a church she attended where she also did volunteer work. “I used to come and help out and slowly he started liking me and the way I worked,” she said about her husband. Parbati was 17 and her husband 22 at the time of marriage. “We were not actually prepared to get married then,” Parbati said. “But I was visiting this place frequently and rumors were starting and my brother said we should get married.”[93]

The ease with which rumors spread, and the harm they can do, especially to a girl’s reputation, mean that gossip can easily be deployed maliciously. In some cases, even mistaken rumors prompted a rushed marriage. “There was a lot of gossip of an affair that I was not having,” said Aarati BK, age 18, who married at age 16. “I was angry. I was angry with everyone.” While battling false rumors, Aarati met a boy she liked. “As soon as I met this guy, I ran away. We got married two days after we met. I eloped to his home.”[94]

Caste and Child marriage

Nepal’s entrenched caste system and discriminatory attitudes based on caste have a significant impact on marriage decisions, including situations where parents cite the necessity of finding a husband of a desirable caste as a justification for a child marriage. “My daughter was 14 years old, and had started going out with friends and some of the friends had boyfriends and some were lower caste boys,” said Rekha Kamat, who arranged for her daughter, at age 14, to marry a 25-year-old neighbor. “I was afraid she would also go out with a lower caste boy and we are high caste and I can’t allow that. So when this proposal came and this boy is high caste and lives nearby, I thought it’s good—she can be safely married, and I can always have my daughter in front of my eyes.”[95]

Some interviewees said the increase in love marriages among children related to growing numbers of relationships between young people of different castes, with children eloping due to their parents’ caste-based opposition to the relationship. Others cited a preference by parents in some areas for their children to marry a spouse from a different village, which leads them to oppose relationships with neighbors or classmates. They said children sometimes eloped in response to this opposition.[96]

Exchange Marriages

In some communities, in both mountainous and plains regions of Nepal, child marriages occasionally happen through what are known as “exchange marriages” where a boy and girl from one family marry a boy and girl from another family.[97]

“I was exchanged,” said Babita Tharu, who married at age 11 to a man about 8 years older than her. “That means my brother married a girl from this village and I married my brother’s wife’s brother…. Because we were so poor, no one would give their hand to us. Because we were so poor we couldn’t pay for any wedding party or anything.”[98]

Escaping Deprivation or Abuse at Home

Some girls entered into child marriages as a means to escape an abusive home. “My dad used to drink a lot. He didn’t own anything and we didn’t have enough to eat, so I had to run away,” said Priyanka Tharu, who eloped at age 14.[99]

“All my troubles started after my mother remarried,” Ramita T. said, explaining why she had a love marriage when she was 12 and her husband was 15. “I would not have married early [otherwise]. My stepfather used to beat me often.”[100]

Parents sometimes abused girls specifically in response to the girl having a romantic relationship—often causing her to flee. “My parents would shout and scream at me about this relationship, because he was lower caste. They used to beat me as well to try to get me to give him up. They beat me more times than I can count,” Rita Malik said. “He lived nearby. Everyone knew about it, and they told my parents,” she said. The couple eloped to Kathmandu when Ritu was 15. “If my parents hadn’t scolded and beaten me so much, I could still be home studying.”[101]

Several girls said their marriages were prompted by their having been abused for attending school instead of working in order to contribute to the family income. “When I used to come back from school I had to work every day. And every day my mother was drinking and would say, ‘Everyone’s daughters are working but you just go to school and don’t work.’ And she would scold so there was a lot of tension,” said Sharmila Bote, who eloped at age 16 with her next-door neighbor.[102]

Dowry

I want to get my dowry back, but whenever I go there, I’m beaten up.

—Priti Devi Satar, married at 15, and thrown out with her baby son by her in-laws after complaints that the dowry paid by her family—an ox, a bicycle, and home utensils—was insufficient.[103]

While dowry is not practiced across all communities in Nepal, and is illegal under Nepali law, it is common in some communities that a bride’s family will provide household goods, cash, jewelry, or other items to the family of their daughter’s new husband at the time of the marriage.[104] For families from communities where dowry is practiced, the need to pay dowry can be a substantial and, for poor families, a sometimes crippling burden.

Parents sometimes feel compelled to go to great lengths to pay the dowry necessary to secure a son-in-law that they feel matches their family’s status. “The amount of dowry has to do with the boy’s achievements,” an NGO worker in the Terai said. “It might be double what the boy’s parents spent on the boy’s education. Parents sell land, take loans with bad interest rates—they spend their lives trying to repay [what they owe for dowry].”[105]

Dowry can be a factor encouraging early arranged child marriages. In some communities, dowry increases as a girl gets older. “If parents find a suitable boy they get their daughter married,” a social mobilizer in Rupandehi said. “Because after two or three years the dowry will go up.”[106]

“My parents were afraid that I would run away, get pregnant, or they will have to give a lot of dowry,” said Priti Devi Satar, who married at age 15. “So they married me early.”[107]

“My daughters-in-law were poor, so we didn’t ask for any dowry,” said Noori Ansari, a mother of five children, including two married sons. “But some guys came to see my daughter and asked for 200,000 rupees ($1,887). Even if I sell this house I won’t get that. Without dowry a guy won’t accept my daughter. She should get married now.” Noori’s daughter is 16 years old.[108]

Dowry practices may also play a role in encouraging child love marriages. Dowry is not expected in cases of love marriage—a factor that may decrease parental objections to such marriages and even lead to parents encouraging them.[109] “There was no dowry because it was an elopement,” said Sarala Pariyar, who eloped at age 16. “Otherwise we have a tradition of giving dowry.”[110]

Parvati Satar married three or four years after she began menstruating. She describes her marriage as a love marriage, but her parents agreed to the marriage. “If I had married another groom he would have demanded dowry, but because my husband is from here and he liked me, there was no dowry,” Lakshmi said. “My parents were happy about this.”[111] While many girls who had love marriages said that their parents had objected to their marriages, the ability to forego paying dowry also provides a significant incentive not to stand in the way.

Migration

He couldn’t find work here. This is the first time he worked overseas. I’m all alone. I live with my mother-in-law—she’s barely breathing, she’s so sick.

—Rita Pariyar, married at 17 and mother of a one-and-a-half-year-old daughter, whose husband left three months earlier for a three-year contract in a factory in Malaysia.[112]

Nepal has become a major sending country of migrant workers. Between 2008/2009 and 2013/2014, over 2.2 million Nepali workers obtained permits for overseas employment, a staggering eight percent of the country’s population.[113] The movement of workers in and out of the country, and the stress on families who have members away for extended periods, has led families to adapt in ways that sometimes affect decisions about child marriage.

“My father wanted to go abroad, and he thought he couldn’t leave me alone with my mother,” said Jyoti Atri. “He thought, ‘She should get married.’” Jyoti married at age 17 to a husband her parents chose, and her father left to go to Punjab, India for 3 years to work as a laborer in a rice meal factory.[114]

“My husband was planning to go for foreign employment and my parents were going to look for a husband for me,” Sarmila BK, age 17, said, explaining why she eloped with her 19-year-old husband 4 months after they met. Her husband went to Qatar after the marriage to work in a glass factory. It was his first time going to work overseas; he signed a contract for three years and will not be able to come back to Nepal during that period. Meanwhile Sarmila is living with her husband’s parents. She says life is more difficult there than it was with her parents, as she has to work more, and she is estranged from her parents because her father is so angry that she eloped. “My father thought he would marry me off, and I did it myself,” she said. “He would have married me at age 20 or 21. My husband wanted to get married before he went overseas because he was afraid I would marry someone else while he was away.” Sarmila was in school until she married but has now quit and hopes to learn her in-laws’ profession, tailoring, instead.[115]

For other families, though, migration for employment seemed to potentially delay marriage. “People’s economic status has improved because of remittances from the Gulf, Korea, Malaysia, India, Japan, Hong Kong,” the head of a private hospital in Nawalparasi said. “At least one or two men from each household have gone for foreign employment…. Men want to earn first and then marry, and girls prefer men who have already earned, so this is causing later marriages. Lots of women are also going for international jobs—they are mostly unmarried.”[116]

Many of the married girls Human Rights Watch interviewed were married to men working overseas. Most seemed not to mind their husbands’ absence—and some, particularly those in abusive relationships, welcomed it. For some young brides, though, their husband’s absence amplified their feeling of isolation and of being forced to grow up too quickly.

Women account for about five percent of Nepal’s migrant workers, a proportion that is growing quickly.[117] Seventy-five percent of female migrant workers are married, and women and girls may face pressure not to migrate prior to marriage based on the view that migration may harm their reputation and make it harder for them to marry later.[118]

III.Consequences of Child Marriage

The United Nations Population Fund recently described the impact of child marriage on girls and their families in the following terms: “Child marriage robs girls of their girlhood, entrenching them and their future families in poverty, limiting their life choices, and generating high development costs for communities.”[119] Married children and adults who had married as children interviewed for this report echoed these findings, speaking poignantly of the harm they had seen in their own lives as a result of child marriage.

Termination of Education

“When girls are married they have to stay at home and can’t study. Same with boys—when they get married they have to work. It’s better for both of them if they study and grow up. If they marry early their whole life is spoiled.”

—Pramila Pandey, who had an arranged marriage at age 14.[120]