Summary

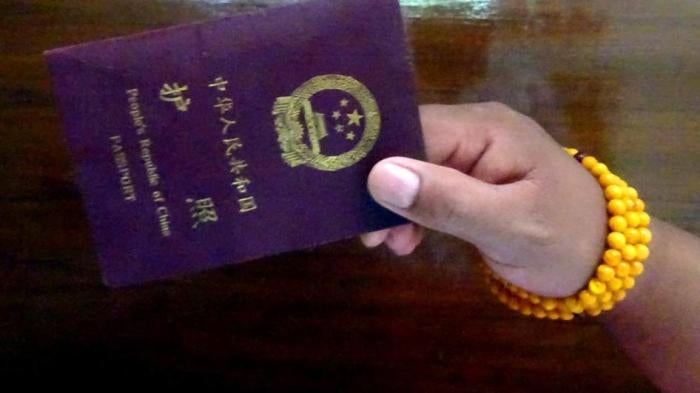

Getting a passport is harder for a Tibetan than getting into heaven. This is one of those “preferential policies” given to us Tibetans by [China’s] central government.

—Post by a Tibetan blogger on a Chinese-language website, October 2012

This report focuses on the way that passports are issued in China. It shows that since 2002, a two-track system has been gradually put in place: one that is quick and straightforward, and another that is extremely slow. The fast-track system is available in areas that are largely populated by the country’s ethnic Chinese majority, while the slow-track system has been imposed in areas populated mainly by Tibetans and certain other religious minorities.

In the parts of China with the fast-track system, a passport application only requires approval from one office—the local branch of the Exit and Entry Administration under the Ministry of Public Security—and these offices are required either to issue a passport to any citizen within 15 days of an application or to explain the delay.[1] But residents of areas with slow-track processing are subjected to extremely long delays, often lasting several years, before passports are issued, or are routinely denied passports for no valid reason.

The two-track passport system thus allows residents of ethnic Chinese areas of China to travel abroad easily, but denies residents of Tibetan, Uyghur, and some Hui areas equal access to foreign travel.

Official documents from Tibetan and other areas with slow-track processing show that these restrictions, though also affecting ethnic Chinese residents of those areas, were initially designed in part to stop Tibetan Buddhists, Uyghurs, and Hui Muslims from religiously motivated travel—for Tibetans, attendance at teachings of the Dalai Lama in India; for certain Muslims, independent pilgrimages to Mecca. Chinese authorities appear to regard these forms of travel as a potential cover for subversive political activity and in some Tibetan areas attending certain religious teachings abroad has been proscribed by law since 2012 as a separatist political activity (see Appendices I and III).

This system of restrictions on foreign travel for members of certain religious minorities has been taken to an extreme in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). Since 2012 the TAR authorities have ordered the confiscation of all ordinary passports held by registered residents of the region, over 90 percent of whom are Tibetans,[2] and appear to have issued no replacements for them. This has prevented nearly all of the three million residents of the region from any foreign travel since that time, except for those who are regarded as traveling on official government business.

Restrictions on access to the region and lack of publicly available data make it impossible to assess the full extent of these restrictions. But our study of a wide array of official documents, websites, and news sources; our review of social media traffic on the question; and our face-to-face interviews with 12 people from the region, some well versed in conditions in the TAR as a whole, found no evidence of a confiscated ordinary passport being returned or replaced in the TAR, or of a new ordinary passport being issued there, since 2012.

Although all areas in China with slow-track passport processing require lengthy delays before passports are issued, Human Rights Watch is unaware of any other area in China besides the TAR where a near-total ban on the issuance of ordinary passports is in force.

These policies and their implementation do not apply to all Tibetans, Uyghurs or Muslims in China, since those registered as residents of cities such as Beijing or Chengdu can obtain passports in the same way as any other resident of that area. Rather, they apply only to certain areas in China that have substantial Tibetan or Muslim populations. Within those areas, these policies are discriminatory whether in intent or effect and impose burdensome requirements that place restrictions on freedom of movement across borders and that contravene international law. By explicitly prohibiting certain forms of pilgrimage, the policies and practices also violate the right to freedom of religion.

The TAR authorities implemented the near-total ban on foreign travel for ordinary residents of the TAR by taking advantage of China’s nationwide rollout of “ePassports.” The Chinese government began issuing these new passports, which include biometric data stored on an embedded chip, across the country to replace expiring old-style passports in May 2012.[3] Since then, passport holders in China are routinely issued ePassports once their old passports have expired.

But in the TAR, the authorities used the rollout of the new passports as an opportunity to demand that all ordinary passports in the TAR be handed in immediately to the authorities. On April 29, 2012, just days before the national rollout began, the TAR authorities issued an internal instruction, Notice No. 22 (see Appendix II), which stated that “using the opportunity of the national launch of ePassports in May of this year, all still-valid ordinary passports in our region shall be withdrawn without exception.”[4] The TAR government then required all residents of the region to hand in their passports, even if these remained valid for several years before expiring, supposedly to be replaced by ePassports. This demand was never made public. Instead, it was communicated orally through visits by local officials to individual passport-holders. Old-style passports that were not handed over after such a visit were cancelled.

Since that time, the TAR authorities are not known to have issued any replacement passports or new passports except for travelers on official business. Notice No. 22 stated that ordinary passports “shall be reissued … following strict review and approval” and instructed officials to “strictly control approvals for the issuance of ordinary passports” (see Appendix II).[5] The Notice also outlined a new passport application procedure for residents of the TAR that is onerous and appears effectively impossible to complete. It requires passport applications to go through 10 separate stages. Approval has to be obtained from different authorities or offices at each stage, ranging from the applicant’s Neighborhood Committee or Village Committee to the top-most level of the Public Security Bureau in the region, before a final decision can be made on each passport application (see box on p. 22 below).

The main elements of this internal order, including the new passport application process, were issued as a public regulation on May 6, 2012 (see Appendix III).[6] That document made it clear that all passport applicants in the TAR must face the rigorous new application system if they wished to obtain a new passport.[7] The May 6 regulations, however, made no mention of the internal order one week earlier recalling all existing ordinary passports in the TAR.

Figures for the number of passports issued in the TAR as a whole have not been made public, but in Chamdo (Ch.: Changdu), one of the seven prefecture-level administrations in the TAR, only two passports were issued in all of 2012, according to a report on the TAR government’s main Internet portal.[8] The prefecture has a population of over 650,000 people. According to the same report, 222 passports were confiscated from individuals in Chamdo Prefecture in 2012 for “safekeeping,” and a further 106 passports were confiscated from residents in the prefecture who had traveled abroad to attend religious teachings by the Dalai Lama in India that year.

The TAR authorities have denied that there is a ban on the issuance of ordinary passports in the region. Instead, they say there are simply delays in processing applications.[9] Our research indicates, however, that the few residents of the TAR who have been allowed to travel since 2012 have almost all been government officials or businessmen with strong connections to the authorities, who were issued semi-official “public affairs passports” as opposed to “ordinary passports.” These passport-holders are required to hand their passports back to the authorities immediately after they return.[10]

There are increasing reports of similar restrictions on foreign travel by Uyghurs and other residents of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). The question of access to passports in Xinjiang is not studied in this report, but on April 30, 2015, all residents holding ordinary passports in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in the XUAR were ordered to hand their passports in to their local police station or face cancellation of the passports (see Appendix V). The prefecture has a population of about three million, of whom 65 percent are members of Muslim minorities. The announcement suggests that further restrictions on foreign travel for residents of Xinjiang are likely.

These developments take place at a time when already-limited respect for human rights, including the rights to freedom of expression, religion, and to a fair trial, is further threatened in the TAR. Since unprecedented protests in the TAR capital, Lhasa, and across the plateau in March 2008, access to Tibetan areas for journalists, diplomats, and other independent observers has become exponentially more difficult, and movement of Tibetans in and out of the region far more restricted. Chinese authorities monitor and censor telecommunications, Internet activity, and messaging, and have increased limitations on access to foreign Tibetan language broadcasts through the jamming and confiscation of satellite reception dishes. They have also stepped up efforts to prevent neighboring countries, particularly Nepal and India, from assisting or accepting asylum claimants from Tibet, and have harassed Tibetan communities in Nepal involved in documenting or protesting conditions in the TAR and adjoining provinces within China which have significant Tibetan populations.

Human Rights Watch urges the Chinese government to immediately ensure that criteria and procedures for the issuance of passports and foreign travel for residents of the TAR, the XUAR, and other minority areas are the same as those for residents in the rest of China. The government should end discriminatory passport practices on the basis of religion or ethnicity and take appropriate action against officials who fail to do so. The government should also ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and incorporate the right to freedom of movement into domestic law.

Recommendations

The Government of China should:

- Ensure that the criteria and procedures for issuing passports for foreign travel are the same for all citizens of China, including Tibetans, Uighurs, and Hui.

- Immediately implement fast-track passport processing in the Tibet Autonomous Region, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and other areas where it has not been introduced to ensure equal rights to freedom of movement.

- Allow all passport-holders to retain and use their passports until their validity has expired and return valid passports being held by the authorities without lawful justification.

- Investigate and take appropriate disciplinary or prosecutorial action against any official who has implemented passport regulations on a discriminatory basis, including for reasons of religious belief or ethnicity, resulting in delays in the issuance of passports or the prevention of foreign travel.

- Cease treating attendance at religious events or teachings abroad, including those conducted by the Dalai Lama and other Tibetan religious figures, as unlawful activities.

- Ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights without reservations and incorporate international law on the right to freedom of movement into domestic law.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch research for this report is based primarily on official documents issued by the TAR authorities, supplemented by interviews with Tibetans and others from the region. Extensive information about passport procedures in the TAR and other Tibetan areas was also obtained from publicly available, official, online sources in China, including local government websites, official online newspapers, and online chat-rooms run by local government agencies to answer questions from the public. Some public bulletin boards and social media in China were also accessed. A search of academic articles in Chinese on this topic was made, but did not produce usable results. The online sources and documents cited in this report were in almost all cases published in Chinese or Tibetan and translated into English by Human Rights Watch.

Interviews were conducted in Tibetan and then translated into English by Human Rights Watch researchers. No incentives or inducements were offered to the interviewees, who agreed to speak to Human Rights Watch on the sole condition that their anonymity was assured. Since the number of Tibetans from the TAR who are now able to travel abroad is so small, and in order to protect interviewees from repercussions to the greatest possible extent, the report does not include biographical details of the interviewees or the location of the interviews.

The scope of this research was necessarily limited by constraints imposed by the Chinese government. The government is hostile to research by international human rights organizations, and strictly limits the activities of domestic civil society organizations on a variety of subjects, particularly those related to human rights violations.

A copy of the two internal notices on travel restrictions issued by the TAR authorities in 2012, which are cited in this report, was provided to Human Rights Watch by a third party. A separate translation of one of the notices was published by the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy (TCHRD), an advocacy group based in India, as part of a report issued on May 5, 2015,[11] after research for this report had been completed.

I. Passport Applications in China: Two Systems

Border entry and exit administration structures within Public Security agencies should issue ordinary passports within 15 days of receiving the application materials. When a passport is not issued due to non-compliance, a formal written explanation should be provided, and the applicant should be informed of their right to pursue an administrative review of the application or to file a civil suit.

—Regulations on passport processing in Shunyi District (Beijing)[12]

There are many bright young Tibetan businessmen in Lhasa and other cities in TAR. Some of them are yuan millionaires running all sorts of businesses, but none have the opportunity to set up a business overseas, as the [ethnic] Chinese do. None have bought a house or opened a bank account overseas, not even in Hong Kong.

—Tibetan businessperson from Lhasa, February 2015

Before 2002, applicants for passports in China were required to compile a significant volume of documentary material in support of their applications. Before being allowed to apply for a passport, they underwent a lengthy and protracted procedure that included completing a “political examination” (Ch.: zhengzhi shencha). In late 2002, the Entry and Exit Administration under the Ministry of Public Security, the agency responsible for issuing passports, initiated a new system with the stated intention of simplifying the passport application process and bringing it “into line with international standards.” The new system was launched by declaring Shanghai Municipality as the country’s first “area where passports are provided on application” (Ch.: anxu shenling huzhao diqu), a system also known as “passport application on demand.”

This “on demand” procedure has since been extended to the vast majority of localities: by 2014, 89 percent of the 339 prefecture-level areas in China had received permission from the Ministry of Public Security to implement fast-track passport processing. All that is required to apply for a passport in one of these areas is a valid identity card and a household registration document (hukou), in addition to a completed application form and the relevant processing fees.

However, a number of prefecture-level areas in China have not been granted permission to use the fast-track passport application system and are still required to use the pre-2002 system. They are officially referred to as “areas where passports are supplied not on application” (Ch.: fei anxu shenling huzhao diqu) or as areas where “passports are supplied conditionally on application” (Ch.: an tiaojian shenling huzhao).

As of October 2014, just 36 of the 339 prefecture-level administrations and 8 of the 2,853 county-level administrations were still using the old, slow-track passport application system and had not received permission to use the new “on demand” system.

Types of PassportsChina issues four types of passports. Diplomatic passports (Ch.: waijiao huzhao) and service passports (Ch.: gongwu huzhao) are issued to senior national government and diplomatic figures and entitle the holders to diplomatic immunity and other privileges under international law. “Public affairs passports” (Ch.: yingong putong huzhao) are given to several categories of people. According to an explanation on the website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, they include “persons from state-owned and collective enterprises, institutions and non-governmental organizations who go abroad to engage in such activities as non-intergovernmental and non-governmental trade, and technical, cultural, educational, health and religious exchanges, including publicly dispatched students for overseas study, and persons engaging in advanced studies or academic exchanges.” “Ordinary passports” (Ch.: yinsi putong huzhao) are in theory available to all citizens who apply, aside from defendants in a pending criminal case or those who are considered a “threat to state security,” and so forth. It is passports of this type that TAR authorities required residents to hand in to local police stations in 2012 and that have not been returned or replaced. |

Applicants from these areas are required to provide far more extensive documentation in support of their passport applications than elsewhere in China. For them, the passport application process still includes many of the time-consuming and bureaucratic requirements that were in place prior to 2002. These include the “political examination” prior to application and the presentation of extensive documentary materials in support of each application. In many cases such areas impose additional restrictions on travel for their residents, such as allowing them to travel as tourists only if they join groups organized by certain travel companies that are officially registered with the government in their locality.[13]

II. The Slow-Track System: Areas with Substantial Tibetan or Muslim Populations

Why is it so hard for minority nationalities to apply for a passport? I’m from Qinghai, I’m Tibetan, and I work for a charity project. I don’t know what the policy is, but I’ve heard that we’ve been put among people of special interest by public security. We provide charitable assistance projects to impoverished areas, so why are we being regarded as terrorists? I’ve passed all the exams to go abroad for further study, but when I applied for a passport I need certificates like: certification from the court, certification from the procuracy, household registration certification, a seal from public security, and a seal from the Entry and Exit Administration, and then in the end I didn’t have certification from State Security so the application was stuck [Ch.: bei kazhu le]! I wonder if anyone else applying for a passport had to get all this certification. Can anyone help me think of what to do? Thank you!

—An anonymous writer to an online Q&A site, August 10, 2010

The prefecture-level administrations that still use the old passport processing system are, with one exception, all areas with substantial Tibetan or Muslim populations. These areas consist of all of the seven administrative areas within the TAR; all of the 14 administrative areas within the XUAR; and the 13 Tibetan or Hui autonomous prefectures in Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan provinces.[14] No Tibetan or Uyghur autonomous areas have been permitted to use the new passport application system, and at least two Hui autonomous areas have also been denied access to this system.[15]

Minority areas excluded from fast-track passport processing as of October 2014[16]

|

Provinces with prefectures that are not permitted fast-track passport processing |

Number of prefectures not permitted fast-track processing |

Number of prefectures not permitted fast-track processing that have substantial Tibetan or Muslim populations |

|

Xinjiang |

14 |

14 |

|

TAR |

7 |

7 |

|

Jiangxi |

1 |

0 |

|

Sichuan |

2 |

2 |

|

Yunnan |

1 |

1 |

|

Gansu |

2 |

2 |

|

Qinghai |

8 |

8 |

|

Total |

36 |

35 |

As the chart above demonstrates, only one prefecture-level area in China without a substantial Tibetan or Muslim population (Jingdezhen prefecture in Jiangxi Province) was still awaiting fast-track processing permission as of October 2014.[17]

The practice of singling out certain areas populated by Tibetans and Uyghurs, and in some cases Hui Muslims, for exclusion from fast-track passport processing is also evident at the county-level: two counties in Gansu Province that are designated as Tibetan or Hui autonomous areas are specifically excluded from permission to use the fast-track system, even though they are within a prefecture or city that has such permission. In a 2014 list of areas allowed to issue passports on demand, the prefecture-level entity given permission to use fast-track processing is named first, followed by the name of the autonomous county within it which is excluded from this provision: “Wuwei City, except Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County” and “Tianshui Prefecture (City), except Zhangjiachuan Hui Autonomous County.”[18]

Under Chinese law, all residents of these areas are in principle equally affected by regulations regarding foreign travel, irrespective of their ethnicity. Nevertheless, these three communities (Tibetans, Uyghurs, or Hui) constitute significant sectors of the population in these areas, and in most cases are the largest demographic group. In addition, as discussed in subsequent sections of this report, the regulations in some localities focus on restrictions regarding forms of travel that are specific to these peoples, such as religious pilgrimages. All three of these ethnic groups have long-established traditions of religious pilgrimage abroad, and Tibetans and Uyghurs in addition have histories of recent protest against Chinese rule. The exclusion of these areas from the fast-track passport application system twelve years after it was first introduced suggests that authorities discriminate against members of these minority nationalities in these areas by limiting or impeding their access to foreign travel.

Other than in the TAR and reportedly the XUAR, residents in all jurisdictions categorized as “areas where passports are supplied not on application” (i.e., where the fast-track system is not in place), such as the Tibetan areas of Sichuan and Qinghai, can sometimes obtain passports, but typically only after long or extremely long delays that are not found in other parts of China. Tibetans and others applying for a passport in these areas to visit relatives abroad, for example, still have to provide documentary evidence issued by the local police station in the areas where they are registered. This documentation has to show in most cases that the family member who is going to be visited abroad is an immediate family member—a parent, spouse or direct offspring—of the applicant. It also has to include the original letter of invitation from the family member, usually with the envelope showing a postmark, along with documentary evidence of the family member’s right to reside in the country of intended travel.[19]

Human Rights Watch knows of numerous cases of Tibetans in Qinghai and Sichuan provinces waiting for up to five years before being allowed a passport, apparently without any explanation being given for the delay. Human Rights Watch has also received information about numerous cases of Tibetans in Sichuan and Qinghai provinces who have not been allowed a passport despite completing the application process, and have not been given any valid explanation for the refusal of their application.

According to Chinese law, passports can only be refused to citizens with criminal records, former detainees, suspects in pending criminal cases, parties to unresolved civil cases, those whose travel is judged to harm “national security and the interests of society,” people who submit fraudulent applications, and certain other classes of people.[20] In the cases studied by Human Rights Watch, Tibetans from Sichuan and Qinghai provinces who were refused passports did not belong to any of these categories and the refusals appeared to be arbitrary or based on their ethnicity.

Human Rights Watch has also uncovered instances of extreme delays for Tibetan citizens of China who have applied for renewal of their passports while abroad. In one instance in 2013-2014, a Tibetan had to wait in another country for over a year while the Chinese authorities processed a standard renewal application that would have taken only a few weeks for a non-Tibetan citizen of China.[21]

Restrictions of these kinds do not apply to all Tibetans throughout China. Tibetans registered as residents of the Tibetan autonomous prefecture within Yunnan Province, Dechen (Ch.: Diqing), do not appear to face abnormal delays or restrictions in obtaining passports, and Human Rights Watch has documented about 10 cases of Tibetans from that area who have received new-issue passports (‘ePassports’). Similarly, Tibetans registered in areas of China that are not autonomous areas and that accordingly allow “passport application on demand,” such as Beijing or Chengdu, are normally able to obtain passports in the same way as other Chinese citizens. Apart from the exceptions noted above in Jiangxi and Fujian provinces, the restrictions described in this report appear to be specific to certain, but not all, areas within China that are designated as Tibetan, Uyghur, or Hui autonomous regions, prefectures, or counties.

III. Passport Restrictions and Limitations on Religious Travel

The government always says that Tibetans keep contacts with the exile government and the Dalai Lama, and give donations to their organizations and “splittist” activities. This is the reason why Tibetans can’t get passports and travel freely.

—Tibetan from Lhasa, February 2015

Part of the initial impetus for retaining restrictive passport policies after 2002 was to prevent travel for certain forms of religious study and pilgrimage. This was evident in procedures issued in the early 2000s by the Chinese government governing foreign travel by members of religious minorities. These procedures explicitly attempted to control religious pilgrimages abroad. In particular, the government wanted to limit Muslim participation in the Hajj to official groups that would be managed and arranged by the authorities, and to discourage individual pilgrimage. Soon after this, the authorities began to limit other forms of individual travel by Uyghurs and some other Muslim groups in China, and also to limit travel by Tibetans.

A set of official regulations governing passport application procedures in Gansu Province published in early 2008 shows that people planning to undertake a pilgrimage abroad were subject to restrictions that did not apply to travelers who had no evident religious purpose. The Gansu regulations instructed officials to deny a passport application if they suspected that the applicant might have been intending to travel abroad to attend “Buddhist rituals” or to participate in the Hajj as an independent traveler rather than joining an authorized tour group permitted to organize such religious activities.

The regulations also listed different requirements for people in “special areas”—the Tibetan and Hui areas of the province—when applying for a passport compared to those who were living elsewhere in the province. The requirements were stricter for students from “special areas” attempting to pursue their studies abroad, or for residents of these areas who applied to visit relatives abroad (see Appendix IV). Similar measures have long been in force in the XUAR as well, a largely Muslim area.

When additional regulations restricting foreign travel were introduced in the TAR in 2012, it was again made clear that these were linked to religious practice by Tibetans. The new regulations declared that attending a religious event abroad, namely teachings by the Dalai Lama, the long-exiled political and religious leader of the Tibetan people, was considered to be a subversive political activity. Since that time, official concern about foreign pilgrimages by Chinese citizens belonging to religious minorities has become more acute, especially in Tibetan areas, and in the TAR has expanded to include all forms of private travel.

The 2012 restrictions on passport applications in the TAR appear to have been shaped by the official response to a particular Tibetan Buddhist ceremony known as the Kalachakra Initiation, which took place in northern India from December 31, 2011 to January 10, 2012. Some 7,000 Tibetans from the TAR and other parts of China traveled to attend religious teachings given by the Dalai Lama during this event. These Tibetans had been issued passports in late 2011 by the TAR authorities or other provincial authorities in China that allowed them to travel legally to Nepal, from where they had transited to India. The fact that so many were allowed passports to attend the teachings was seen at the time as evidence of a possible policy relaxation by Beijing.

However, Chinese authorities detained many of these Tibetans once they returned to the TAR from Nepal even though they had the requisite travel documentation for travelling there. [22] The authorities said that their travel onwards from Nepal to India to attend Dalai Lama teachings had constituted participation in “splittist” activities.[23] Between January and April 2012 thousands of the Tibetan detainees, many of whom were elderly retirees, were sent to various detention facilities in the TAR where they underwent “re-education” for up to three months. Returnees who were caught carrying videos or religious texts relating to the teachings were reportedly subjected to police investigations. Although Tibetans re-entering Tibet (China) at the China-Nepal border are often detained and imprisoned if they had previously left China without valid travel documents, the detention without additional reason of returning Tibetans who had traveled on legal papers was unprecedented.

Approximately 700 ethnic Chinese passport-holders also attended the Dalai Lama’s teachings in India at that time,[24] but none are known to have been detained or punished on their return to China.[25] This strongly suggests that Tibetans detained for attendance at the Dalai Lama’s teachings in 2012 were targeted for participation in a religious activity based solely on their ethnicity.

A connection between the passport controls and attempts to stop attendance at teachings by the Dalai Lama is strongly suggested in two internal orders circulated in the TAR in April 2012. The first of these, Notice No. 22, imposed stringent new conditions on passport applications in the TAR, but it gave no reason for these other than saying that they were needed “in order to further regulate our Region’s passport handling, approvals, and issuance work” (see Appendix II). It thus appeared to be merely following national instructions to facilitate the issuing of new, electronic passports, though in fact it went considerably beyond that goal.

When Notice No. 22 was distributed to offices in the TAR, however, it was accompanied by another internal notice, dated three days earlier. The notice announced the “Punishment Regulations for Chinese Communist Party Members and Public Servants who Leave the Country to Participate in Such Splittist Activities as the Dalai clique’s ‘Kalachakra.’” Issued on April 26, 2012, it made no mention of passports or new passport procedures (see Appendix I). Instead, it ordered government and Party officials in the TAR not to attend any religious services or teachings organized by the “Dalai clique” and described attendance at such teachings as “crimes of secession and undermining national unity.” It prescribed administrative punishments—which are levied by the Party rather than the courts—for officials caught in such acts, ranging from expulsion from the Party and dismissal from one’s job to a reduction in pension and loss of benefits for retirees.

The fact that the two notices were issued in rapid succession strongly suggests that the TAR authorities crafted the new restrictions on passport applications in part to prevent attendance at the religious teachings, seen in this case as a form of pro-independence activity. This linkage was made explicit when the public version of the two internal notices was issued on May 6, 2012 (see Appendix III). It lists the new restrictions on passport applications in the TAR as the main component in its effort to stop Tibetans attending events such as the Kalachakra initiation, which it describes as a strategy by “the Dalai clique” to entice people to take part in activities promoting independence for Tibet.

|

Excerpt from TAR Regulations of May 6, 2012, on Strictly Forbidding Exiting the Border to Participate in “Splittist Activities” Article 2: The Dalai clique is luring the masses into participating in various activities such as the “Kalachakra,” advocating “Tibetan independence” thinking, using religion to harm the unity of the nationalities and the unification of the country, and completely deviating from the religious traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, constituting the criminal behavior of splitting the nation. |

The May 6 regulations applied to “all residents within the administrative area of the autonomous region” as well as “incoming business people and workers without exception,” apparently encompassing Tibetans from Tibetan areas outside the TAR, which lie mainly within Sichuan, Qinghai, and Gansu provinces. It declared that any attempts by residents or migrants in the TAR to cross the border to attend teachings by the Dalai Lama would be “punished according to the law” (article 7.4), while serious offenders, such as “planners, organizers, or backbone elements” of attempts to attend such teachings, would be subject to criminal proceedings (article 7.1).

The extent of criminal punishment is not specified, but a number of additional administrative penalties are listed: any persons (Ch.: renyuan) caught travelling to hear the Dalai Lama teach will be banned “without exception” from ever having a job in any government institution or a state-owned enterprise (article 7.8), be required “without exception to undergo concentrated education (Ch.: jizhong jiaoyu)” (article 7.4), and banned from receiving any future financial subsidies and “any new preferential policies, subsidies or grants” (article 7.6). In addition, traders from outside the TAR caught going outside the country to attend such religious events will be banned from doing business in the region (article 7.3).

The regulations state that passport application procedures must be strengthened, including “conducting a thorough cleansing (Ch.: qingli) of persons holding a passport who go abroad on private travel” again for the purpose of preventing travel abroad in order to attend teachings by the Dalai Lama. This is also true of the section in the regulations that bans any office of the Public Security Bureau in the TAR other than the one at the highest (provincial) level from approving passport applications (article 6). The regulations also declare that all future applications for ordinary passports must be “examined and reviewed” in turn by offices at “village (neighborhood), township (town), county (city, district), and prefectural (city) levels” before being submitted to the regional-level Public Security Department for approval. Again, the reason is to prevent travel to attend teachings by the Dalai Lama.

Those wishing to attend religious teachings by the Dalai Lama and willing to travel abroad from Tibet to do so will almost all be Tibetans, specifically Tibetan Buddhists. Although the restrictions on access to passports in the TAR are never said in official documents to apply specifically to Tibetans or Tibetan Buddhists—they are equally applicable in law to ethnic Chinese and other non-Tibetan residents of the region—the wording and presentation of the 2012 documents indicate that the restrictions are aimed at Tibetans, and in particular at Tibetans who are practicing Buddhists and are religious followers of the Dalai Lama.

IV. Restrictions in the TAR

In recent years, many Chinese officials and businessmen in Lhasa have started sending their kids to study abroad ... [M]any wealthy Tibetan families badly want to take this opportunity, but they can’t. It’s because they can’t get passports for their children and have no access to information. It also seems that the government takes a negative view of [Tibetans’] political attitude.

—Tibetan businessperson, February 2015.

In principle, although residents of the TAR and of the Tibetan prefectures in Sichuan, Qinghai, and Gansu are restricted to the slow-track system in passport applications, they should be able to get a passport once they have undergone a political examination and completed the lengthy application process.

But the new procedures introduced by the TAR authorities in 2012 involved numerous restrictions and demands that go far beyond those in the other areas denied permission to use the fast-track system. As noted above, the primary difference between procedures in the TAR and all other areas of China, except parts of Xinjiang, was the recall or confiscation of all ordinary passports. This was carried out by using the nationwide roll-out of “ePassports” in May 2012 as an excuse to require TAR residents to hand in their passports immediately. In the rest of China, the new-style passports are being issued only once the validity of an old-style passport has expired. But in the TAR, all residents were required to hand their passports in to the authorities even if they still had many years to run before expiration.

The recall of ordinary passports in the TAR was not done by issuing a blanket order to the public (as was done in Ili, a prefecture within Xinjiang, in 2015, as explained below). Instead, local offices in each jurisdiction within the TAR—usually Neighborhood Committees—individually contacted each resident who was known to possess an ordinary passport. According to Human Rights Watch interviewees, when a resident handed over a passport, police would list the passport in a register and issue a receipt with the passport number on it. The registration of the passport number meant that it remained valid.[26] That validity is, however, purely theoretical, unless the officials can be persuaded to return the passport or replace it.

Some Tibetans told Human Rights Watch that they tried to hide their passports, claim that they had been lost, or left them in Chinese cities outside the TAR. But in at least some cases, this prompted the authorities to cancel the missing passports. In two cases documented by Human Rights Watch, Tibetans from the TAR who had been told to hand their passports over but had not done so were stopped at airports when they later tried to travel abroad and were not allowed to leave China.[27]

The individual-contact system used for the recall of ordinary passports in the TAR resulted in some omissions in implementation. Human Rights Watch knows of two Tibetan passport-holders from the TAR whose cases were overlooked by the TAR authorities. They had not received orders from their local Neighborhood Committee or police station to hand over their passports. Their passports remained valid for foreign travel. However, once they return to the TAR, they expect their passports will come to the attention of local officials and be confiscated.

Although all ordinary passports in the TAR were recalled from May 2012 onwards, Tibetan officials and government employees in the TAR, together with a number of wealthy Tibetan businesspeople from the region, have been issued “public affairs passports” or in some cases have been allowed to retain their old ones. They have then been allowed to use these to travel abroad for specific purposes designated as public affairs.

The first TAR residents allowed to travel abroad on such passports after the withdrawal of ordinary passports in the TAR in 2012 were two government staff members from the TAR, one Tibetan and one ethnic Chinese. They had to wait three months to get their public affairs passports issued or returned. They were not allowed to bring their wives or family members with them, unlike delegates from other parts of China sent on the same mission abroad.[28]

A Tibetan who told Human Rights Watch that he had been able to reclaim his public affairs passport for a business trip abroad in 2015 said he was only able to recover it after being interviewed at length by police about the nature of his trip and about whom he was planning to meet. He was told to report back to the same police station in China as soon as he returned and to hand over the passport within 45 days.[29]

Besides the recall of ordinary passports, in 2012 the TAR authorities also introduced a new and exceptionally difficult passport application system. As noted above, Notice No. 22 (2012) requires any TAR resident applying for an ordinary passport to obtain approval from 10 different offices. As far as is known, the stringency of this requirement is unmatched elsewhere in China. Human Rights Watch could not find any evidence that any ordinary passports have been issued in the TAR since this procedure was introduced.

|

The 10 Stages of the Application Process for an Ordinary Passport in the TAR A summary based on the instructions given in Notice No. 22, April 29, 2012

|

Notice No. 22 imposes further restrictions on TAR residents who might be able to obtain an ordinary passport in the future. These include requirements that any person (Ch. renyuan) who in the future receives a passport from the TAR must sign “a declaration of responsibility” when they receive their passports, “guaranteeing that on leaving the country they will not engage in any activities that threaten national security or national interests.”[30] It orders all such persons from the TAR who in the future obtain passports, including holders of ordinary passports and those travelling as tourists, to hand over their passports to the police “for unified safekeeping” on return from each trip abroad, a measure that is not required of holders of ordinary passports elsewhere in China.

In addition, the new regulations require police to visit and interview passport-holders from the TAR when they return from a foreign trip and to “conduct a face-to-face interview” to see if anything illegal took place during their trip abroad.

Notice No. 22 also imposes restrictions on TAR residents travelling on official business. It states that “public affairs passports must be returned to the agency nominated by the issuing department within seven days of returning to the country for safe-keeping or for cancelation.”[31] It also orders that government employees are no longer allowed to hold ordinary passports except in special circumstances and then only after rigorous checks at the highest level.

The set of regulations issued on May 6, 2012 (see Appendix III), which appears to be the public version of Notice No. 22, enhanced the status of some of the instructions into law.[32] The regulations outline the same prohibitive requirements for passport applicants as are listed in the internal notice, but with fewer details.

The May 6 regulations threaten “strict punishment” for any officials who “take an ambiguous attitude” or are weak in applying the new restrictions on travel abroad by TAR residents and government employees. It lists numerous forms of punishment for any residents of the TAR who travel abroad in order to attend teachings by the Dalai Lama (see above).

In particular, it states that any persons (Ch.: renyuan) from the TAR trying to return to China after attending such events abroad “shall without exception not be permitted to enter the border” (article 8)—apparently an order that they should be banned from returning to China.[33] This rule appears to deny people who infringe this provision their internationally protected right to return to their own country.[34]

Other procedures concerning foreign travel for Tibetans have also been tightened. For example, since 2012, some neighborhood offices in the TAR have told local residents that letters from Tibetan family members living abroad will no longer be accepted as supporting materials for passport applications, adding one more obstacle to travel abroad.[35] Family reunion is only one of the forms of foreign travel theoretically allowed for Tibetans and other citizens of China—others include tourism, study, and business—but family reunion is the one most relevant to ordinary Tibetans. This unwritten change to existing rules appears to be another attempt to frustrate Tibetan efforts to obtain permission to travel abroad.

As a result of these measures, while Tibetans in the eastern Tibetan regions face long delays in acquiring passports and are often refused a passport for no valid reason, for the last three years the vast majority of residents of the TAR have not been able to recover a passport once it has been confiscated, to replace an old passport with a new electronic one, or to obtain a new passport, except those allowed to travel on official business or able to get a passport from another jurisdiction outside the TAR. The vast majority of TAR residents, who are overwhelmingly Tibetans, have not been allowed any form of foreign travel during this time.

These restrictions on foreign travel are in addition to numerous well-documented reports of restrictions on the internal movement of Tibetans between Tibetan areas. In particular, from 2012 the TAR authorities required eastern Tibetans to present additional letters of guarantee and other official documents in order to enter the TAR or Lhasa. Such requirements were not applied to non-Tibetans, who were allowed to enter just by showing normal identity cards, if anything. These discriminatory requirements were reportedly only dropped in late 2014 after direct intervention by top leaders in Beijing.[36]

Chinese Government Claims

Chinese authorities in the TAR have denied that there is a ban or restriction on issuing passports to Tibetans or other residents of the region, and assert that the application process is lengthy because it is more complex than in the past. When the ethnic Chinese wife of a soldier serving in the TAR, who was originally from Sichuan Province, wrote to a Lhasa government website in 2014 complaining that she was unable to get a passport, the official response was that “the claim … that almost everyone with a Tibet residence permit cannot get a passport or travel permit is subjective, one-sided, and inaccurate.” The government’s explanation for the failure to issue a passport was that “in accordance with current autonomous region policies for residents applying for a passport or travel permit, specific and detailed application materials must be provided.”[37]

That TAR authorities have denied the existence of any ban could mean that the national government in Beijing has not authorized such a step or has ordered that it be deniable. The contradiction between the official position on the issue and the actual situation on the ground has led to confusion among the general public in Tibet, as demonstrated by speculation on social media about the causes and extent of the restrictions and occasional online rumors that they are about to be lifted.

However, at least eight people from Lhasa independently told Human Rights Watch that ordinary Tibetans in the TAR have not been able to get passports there since 2012. There are also widespread indications on social media of a blanket refusal of passport applications from ordinary Tibetans in the TAR.

In an October 2014 posting, since deleted, on WeChat, a popular Chinese micro-blog site, a contributor reported that they had gone to a passport office in Lhasa to enquire about making an application but had been told that passports were still not being issued to Tibetans, whether individually or as part of tour groups. “Therefore, it is not true that Tibetans can get a passport to travel abroad. It is just a daydream,” the contributor wrote.[38]

One Tibetan, writing in June 2013 to a website that allows readers to submit legal questions that are then answered on an ad hoc basis by lawyers, asked:

Dear Lawyer. I want to know why we Tibetans are unable to get a passport. What about the laws and regulations of the People’s Republic of China? There are many of us Tibetan compatriots who want to know what’s happening, so can I trouble you for a detailed explanation?[39]

In May 2015, according to foreign media reports, travel agents in various parts of China received official instructions not to allow residents of any Tibetan autonomous area to join tourism groups travelling to Hong Kong or Macao or abroad between May 20 and July 15,2015.[40] At least four travel agents in China interviewed by Radio Free Asia were said to have interpreted this instruction as applying to Tibetans from those areas. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any previous such prohibition in China on foreign tourism by members of a specific ethnicity or residents of an ethnic minority area. The order may be intended to prevent Tibetans from attending celebrations abroad of the 80th birthday of the Dalai Lama on July 6, 2015.

A Tibetan businessperson from Lhasa told Human Rights Watch that two Tibetan friends applied for passports in July 2014 to travel to Nepal on business. They approached their local Neighborhood Committee—a quasi-governmental office that carries out local administration for the government and the Party in urban areas—as required by the new regulations. But they were refused permission to apply by the head of the Neighborhood Committee. The official told the interviewee’s friends that all such committees had been instructed by the Lhasa municipal government to refuse passport applications.

Certain Tibetan businesspeople have been allowed to travel on semi-official “public affairs passports,” but this concession has been limited. As a result, according to some interviewees, many Tibetan traders are reported to have lost their means of making a living. Up until 2012 several hundred Tibetan traders had traveled regularly between Nepal and Tibet, importing Nepali handicrafts and housewares, as part of a centuries-old tradition of artisan trading between Tibet and Nepal. Since the new restrictions on Tibetans from the TAR were introduced, Chinese entrepreneurs have stepped in to take over the trade, according to a Tibetan trader who told Human Rights Watch that to his knowledge there are no longer any Tibetans running businesses in the Nepali cities of Kathmandu or Pokhara.[41]

Can Tibetans travel abroad? A classmate said the local Public Security Bureau told him when he was applying for a passport that he can’t leave the country.[42]

The slowdown on travel by Tibetan traders and ordinary residents to Nepal has coincided with an increase in the numbers of travelers to Nepal from elsewhere in China. According to a report in the official media in the TAR, 600 people applied for a Nepalese visa on a single day in Lhasa, and up to 200,000 were expected to apply in 2015.[43] These travelers are believed to be primarily ethnic Chinese citizens from areas of China other than the TAR or, in a very small number of cases, TAR residents who have been permitted to travel on official business. A photograph of the Nepalese consulate in Lhasa from July 2014 shows large numbers of applicants lining up for visas for Nepal; the photographer, a local Tibetan, reported seeing few if any Tibetans in the queue, though this claim could not be substantiated.

One impact of the restrictions on foreign travel for Tibetans has been an increase in the number of Tibetans going on pilgrimages within Tibet or the eastern Tibetan areas within China, rather than traveling to India or Nepal. One Tibetan told Human Rights Watch, “As a result of the travel restriction policy for Tibetans, there are thousands of Tibetans from the Lhasa area going to Qinghai Province to attend teachings or on pilgrimages.”[44] The person reported that because of the large number of visitors to those sites, pilgrims from the TAR now have to obtain travel permits from local police stations in the TAR before they can go to inland China.[45] Human Rights Watch has not been able to confirm reports about this reported new requirement.

Travel by Ethnic Chinese Residents of the TAR

The 2012 regulations governing passport applications in the TAR do not differentiate applicants by ethnicity. A number of interviewees reported that they knew of ethnic Chinese residents of the TAR who also could not recover their ordinary passports or obtain new ones.

However, there is some anecdotal evidence that the requirements are being applied in a discriminatory fashion. Two Tibetan interviewees separately told Human Rights Watch that officials in certain neighborhood committees in Lhasa had specifically informed them that the new restrictions did not apply to ethnic Chinese residents in their locality. According to one, the official had said that, “If we were [ethnic] Chinese he could write the supporting letter…. Stopping the issue of new passports and renewals is only for Tibetans. The decision specifically targets ordinary Tibetans but has not affected [ethnic] Chinese who live in Tibet.”[46]

Another interviewee stated that the rapidly increasing number of ethnic Chinese businessmen travelling to Nepal included many ethnic Chinese residents of the TAR, suggesting that far more Chinese businessmen in the TAR have been issued “public affairs passports” since 2012 than have Tibetans.[47] In one case documented by Human Rights Watch, an ethnic Chinese resident of the TAR was able to use her public affairs passport for a private holiday in Nepal.

Another source interviewed by Human Rights Watch claimed that in the TAR, ethnic Chinese residents with public affairs passports were allowed to retain their passports after returning from foreign trips, while he and other Tibetans he knew who had the same kind of passport had to submit theirs to their local police station on their return from each journey.[48] Human Rights Watch could not corroborate this account.

Evidence from Xinjiang

A US-based monitoring group, the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), reported similar restrictions on the issuance of passports in the XUAR, where a majority of the population are members of ethnic minorities. According to UHRP, a policy of withdrawing passports held by Uyghurs was in effect in Xinjiang as early as 2006, and since then Uighur applicants have had to pay large bribes to recover or obtain a passport. According to the group, since serious rioting took place in the regional capital, Urumchi, in July 2009, the authorities in Xinjiang have routinely denied passport applications submitted by Uyghurs.[49]

Partial confirmation of these reports emerged in April 2015, when the authorities in Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in the XUAR issued a public notice requiring all residents with ordinary passports to hand them in to their local police station “for concentrated management” (see Appendix V). The notice did not give any reason for the recall and did not say under what conditions residents could reclaim their passports from police stations. According to The New York Times, police in Ili prefecture stopped issuing ordinary passports for individual travel in November 2014.[50]

These reports suggest that the current passport policy in the XUAR is roughly the same as the policy initiated in 2012 in the TAR, and that XUAR authorities may be taking formal steps to further limit individual travel abroad by local residents.

V. International Legal Standards

The right to freedom of movement is recognized under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,[51] the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.[52] As a signatory to the ICCPR,[53] China is prohibited from taking actions that would interfere with the right that “[e]veryone shall be free to leave any country, including his own.”[54]

China may only limit the movement of people inside the country where “provided by law … and necessary to protect national security, public order, public health or morals, or the rights and freedoms of others.”[55] In addition, these restrictions must be non-discriminatory and be “necessary” to achieve one or more legitimate aims. Any such restrictions on a person’s free movement must be proportionate in relation to the aim sought to be achieved by the restriction and carefully balanced against the specific reason for the restriction being put in place.[56]

Any restriction on freedom of movement must not have a discriminatory effect,[57] which has been described by the United Nations Human Rights Committee as:

Any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference which is based on any ground such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, and which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by all persons, on an equal footing, of all rights and freedoms.[58]

The Constitution of the People’s Republic of China guarantees citizens’ freedom of religious belief and prohibits discrimination on the basis of religion.[59]

Any restriction on freedom of movement must be clearly and precisely set out in domestic law. The principal reasons for this requirement are to prevent officials from taking arbitrary decisions and to ensure that people whose right to free movement is restricted understand their rights.[60] Restrictions on freedom of movement invoking lawful aims must be specific about how, for example, national security would be threatened if the people prohibited from leaving were allowed to leave. The restrictions also must be shown to be necessary to achieve the aim.[61]

Finally, any restriction must be the least restrictive measure possible to achieve the legitimate aim. In deciding how to identify the least restrictive measure possible, the government needs to balance three factors: (i) the extent of the restriction; (ii) the impact on peoples’ exercise of the right affected, and any other negative impact on their lives; and (iii) why the restriction is necessary to bring about the desired aim.

China’s passport system in the TAR, and likely in the XUAR as well, do not meet international standards protecting the right to freedom of movement. By all accounts the regulations are enforced in a manner that discriminates on the basis of religion or ethnicity. While the evidence available to us demonstrates that the regulations have an apparent discriminatory purpose, they in any event have an unlawful discriminatory effect. Restrictions imposed specifically to prevent attendance at Buddhist or Muslim religious events abroad also violate the right to freedom of religious belief. And the Chinese government’s restrictions on freedom of movement, even if they were not discriminatory, would fail to meet international standards for such restrictions: they are indefinite and broad-based and so disproportionate to any legitimate government aim.

Appendix I

Internal Notice issued by the TAR Authorities, April 26, 2012. Unofficial translation from Chinese.

[Page 1]

Notice on Printing the “Punishment Regulations for Chinese Communist Party Members and Public Servants who Leave the Country to Participate in Such Splittist Activities as the Dalai clique’s ‘Kalachakra’ (Experimental)”

Chinese Communist Party TAR Discipline Inspection Committee.

TAR Supervision Department.

(Notice)

TAR Discipline and Inspection Committee (2012) No. 51.

Notice on Printing the “Punishment Regulations for Chinese Communist Party Members and Public Servants who Leave the Country to Participate in Such Splittist Activities as the Dalai clique’s ‘Kalachakra’ (Experimental)”

To all prefectures and prefecture-level city committees, regional committees, and each departmental committee, and to Party groups in all autonomous regional committees, offices, departments, and bureaus, and all people’s collective Party groups (Party committees):

With the agreement of the regional Party committee and government, this printing of the “Punishment Regulations for Chinese Communist Party Members and Public Servants who Leave the Country to Participate in Such Splittist Activities as the Dalai clique’s ‘Kalachakra’ (Experimental)” is hereby issued to you to be conscientiously and thoroughly implemented.

TAR Chinese Communist Party Discipline Inspection Committee

TAR Supervision Department

April 26, 2012

[Page 2]

TAR Chinese Communist Party Discipline Inspection Committee

TAR Supervision Department

Punishment Regulations for Chinese Communist Party Members and Public Servants who Leave the Country to Participate in Such Splittist Activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra”

(Experimental)

In order to uphold the unification of the Motherland and the unity of the nationalities, to strictly enforce Party discipline and government discipline, and to strictly forbid Chinese Communist Party members and public servants from exiting the border to participate in such splittist activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra,” these regulations are formulated in accordance with the provisions of the “Chinese Communist Party Discipline Punishment Rules” and the “Administrative Agency Public Servant Punishment Rules.”

Article 1

Exiting the border to participate in such splittist activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra” is an adherence to the Dalai clique’s plot to split the Motherland and harm the unity of the nationalities, and a serious violation of political discipline. Without exception, Chinese Communist Party members and public servants are not permitted to leave the country to participate in such splittist activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra.”

Article 2

These regulations are applicable to Chinese Communist Party members, public servants, state workers under civil servant management, and other personnel in positions with state administration agencies who leave the country to participate in such illegal activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra.”

Article 3

Chinese Communist Party members who leave the country to participate in such illegal activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra” and who are planners, organizers, or backbone elements, shall be punished [Ch.: chufen] with expulsion from the Party.

Other participating Chinese Communist Party members shall be punished by a warning or a serious warning in minor circumstances; in relatively serious circumstances they shall be punished with removal from their Party positions or probation while remaining in the Party. In serious circumstances, they shall be punished by expulsion from the Party.

Chinese Communist Party members who are deceived or coerced into participating and who express repentance following criticism and education may avoid punishment. However, they must be ordered to conduct a thorough review.

Article 4

Public servants who leave the country to participate in such illegal activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra” and who are planners, organizers, or backbone elements, shall be punished by expulsion.

Other participating civil servants shall punished by a demerit or a major demerit in minor circumstances; in relatively serious circumstances they shall be punished by demotion or removal from their post; in serious circumstances they shall be punished by expulsion.

Public servants who are deceived or coerced into participating and who express repentance following criticism and education may avoid punishment. However, they must be ordered to conduct a thorough review.

Retired civil servants who leave the country to participate in such illegal activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra” may avoid punishment. However, they must be ordered to conduct a thorough review. In relatively serious circumstances they shall be handled dependent upon conditions by a corresponding reduction or deduction in pension, and a reduction in political privileges and living privileges.

Article 5

These regulations may be referred to for implementation against any government agency contract personnel, non-state workers under civil servant management, workers directly under TAR government agencies (including institutions), and professionals at state-owned and state-invested enterprises who leave the country to participate in such illegal activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra.”

Article 6

Splittist activities referred to in these regulations includes all kinds of activities organized abroad by the Dalai clique with the aim of splitting the Motherland and harming the unity of the nationalities, including the “Wheel of Time Kalachara.”

Article 7

“Minor circumstances” referred to in these regulations indicates being able to recognize one’s mistakes following education and expressing repentance; “relatively serious circumstances” referred to in these regulations indicates not having a clear understanding of one’s mistakes, and not making a clear expression of repentance following education; “serious circumstances” indicates a bad attitude and refusing to repent.

Article 8

Persons (Ch.: renyuan) who leave the country to participate in such illegal activities as the Dalai clique’s “Kalachakra” and who are able to confess to the problem on their own volition, or who report on others on their own volition, or who make other meritorious expressions shall be punished lightly or avoid punishment.

Article 9

The TAR Chinese Communist Party Discipline Inspection Committee and the TAR Supervision Department are responsible for interpreting these regulations.

Article 10

These regulations are effective from the day of promulgation.

Copies sent to:

Central Discipline Inspection Committee, Supervision Department

TAR Party Committee, autonomous regional People’s Government

Each Prefecture and Prefecture-Level City Party Committee and Supervision Bureau, the Regional Discipline Inspection Committee and Supervision Department, each Stationed Discipline Group and Supervision Office, Regional-Level Discipline Work Committee, Regional Education Discipline Work Committee

TAR CCP Discipline Inspection Committee General Office Printed on April 26, 2012

Total 300 copies

Appendix II

Internal Notice issued by the TAR authorities, April 29, 2012. Unofficial translation from Chinese.

[Page 1]

TAR Party Committee General Office Document

TAR Party Committee GenOffDoc (2012) No. 22

TAR Party Committee General Office

TAR People’s Government General Office

Notice on Printing “Suggestions on Further Strengthening Our Region’s Passport Handling, Approvals, and Issuance Management”

All prefecture and prefecture-level city Party committees, all administrative offices and the Lhasa City People’s Government, the Regional Party committee and all departmental committees, all committees, offices, departments and bureau in the autonomous region, and all People’s collectives:

“Suggestions on Further Strengthening Our Region’s Passport Handling, Approvals and Issuance Management” has been approved by the regional Party committee and government, and is hereby issued to you in print. Please integrate realities and implement conscientiously and thoroughly.

[Page 2]

TAR Party Committee General Office

TAR People’s Government General Office

April 29, 2012

(This document has been sent to prefectural department levels, and to county Party committees and county governments.)

[Page 3]

Suggestions on Further Strengthening Our Region’s Passport Handling, Approvals, and Issuance Management

In order to further regulate our Region’s passport handling, approvals and issuance work and in accordance with relevant national laws and regulations, and by integrating the work realities of our region, the following work suggestions are specially proposed:

I. Earnestly strengthen management work over citizens’ handling, approvals and issuance of ordinary passports

- Using the opportunity of the national launch of ePassports in May of this year, all still-valid ordinary passports in our region shall be withdrawn without exception. Those needing to apply for an ordinary passport shall be re-issued with an ordinary ePassport following strict review and approval.

- Strictly control approvals for the issuance of ordinary passports. Ordinary passport applications and issuance shall be carried out under a system of “apply in the domicile, examine at the prefecture, unified approval by the regional Public Security Department.” First, all citizens in the region without exception and in accordance with the principle of local management, when applying for an ordinary passport shall apply to the prefecture-level (prefecture-level city) public security agency where their household is registered; the regional Entry and Exit Administration of the Public Security Department shall no longer accept or handle applications. Second, ordinary passport applicants must provide a self-completed application to be delivered in person to their local village (neighborhood) committee, township (town) People’s Government (neighborhood affairs office) and police station for initial examination. The police station shall submit the application materials to the township (town) People’s Government (neighborhood affairs office) for review by the leaders, and report it to the county (county-level city, district) Public Security Bureau for handling. Following a review by the county (county-level city, district) Public Security Bureau, the application materials shall be sent to the county (county-level city, district) People’s Government leaders for examination and approval and for them to provide their opinions. After reporting to the prefecture-level (prefecture-level city) Public Security Exit and Entry Administration, the application materials shall be delivered to the principal leaders of the prefecture-level (prefecture-level city) Public Security Bureau (Office) for examination and approval, and then reported to the principal leaders of the [prefecture] administration (Government) for review and approval. Once all formalities are complete, the prefecture-level (prefecture-level city) Public Security Entry and Exit Administration departments shall report to the Regional Public Security Department Entry and Exit Administration for review and approval, and issuance. Upon returning to the country, passport-holders without exception must hand their passport in to the local prefecture-level (prefecture-level city) Public Security Exit and Entry Administration department for unified safe-keeping.

- Strictly limit state workers holding ordinary passports. When prefecture (prefecture-level city) Public Security Exit and Entry Administration departments receive a citizen’s application for an ordinary passport, an examination should be carried out of the applicant’s application materials and the applicant should be interviewed to ascertain whether or not they are a state worker. On the principle of not issuing ordinary passports to state workers in our region, if an ordinary passport is required for crossing the border due to exceptional circumstances, cadres at county-level and below shall be reviewed and approved by their local prefecture (prefecture-level city) Party committee Organization Department; cadres above county level applying for an ordinary passport shall be reviewed and approved by the autonomous regional Party committee Organization Department. Upon returning to the country from traveling abroad, all passports without exception must be handed in to the passport-holder’s local Organization Department at the county-level (county-level city, district) or above for unified safe-keeping.

- Implement a system of persons [Ch.: renyuan] with ordinary passports signing a declaration of responsibility [Ch.: zeren shu]. When such persons collect an ordinary passport for the purpose of private foreign travel, they must sign a declaration of responsibility in person at the prefecture (prefecture-level) Public Security Exit and Entry Administration, guaranteeing that on leaving the country they will not engage in any activities that threaten national security or national interests, or other illegal criminal activities. The Public Security Exit and Entry Administration must seek out a visit with the passport holder on their return and conduct a face-to-face interview, and if any illegal activities are discovered, the passports without exception shall be canceled or declared invalid.

II. Conscientiously carry out good work on tour group passport applications

In accordance with Article 9, Chapter II of the “Tourist Agency Regulations” promulgated by the State Council, and the provisions of Article 10, Chapter II of the “Detailed Implementation Measures,” earnestly strengthen the handling of tour groups’ ordinary passports.

- When travel agency tour groups travel abroad, citizens from our region applying for an ordinary passport necessary for travel must carry out their passport application in strict accordance with the relevant provisions, being checked and approved one-by-one, and in strict accordance with the principle of “whoever checks also approves and is also responsible.” Travel agencies must sign a formal travel contract with the traveler.

- When travel agencies complete their handling of passports, a responsible person shall go the autonomous regional Tourism Bureau Supervision and Management Office to receive a “Form for a Namelist of Chinese Citizens Leaving the Country in a Tour Group,” and complete it conscientiously. Once completed by the tour group operator, the third copy of the “Form for a Namelist of Chinese Citizens Leaving the Country in a Tour Group” shall be retained by the autonomous regional Tourism Bureau Supervision and Management Office.

- Strict tour-group management of passports. Regarding citizens from our Region who have participated in a tour group and applied for an ordinary passport, and upon such tour group participants’ return to the country, without exception, their passports shall be collected and handed in to the prefecture (prefecture-level city) Public Security Exit and Entry Administration department by the travel agency organizing the tour group for safe-keeping.

III. Further strengthen management work on the approval and issuance of public affairs passports

- Strictly strengthen management work on public affairs passports in accordance with the “Notice on Printing ‘Diplomatic Passport, Service Passport, and Public Affairs Passport Retrieval Measures’ (MFA Doc [2006] No. 60)” issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the “Notice on ‘Detailed Measures on the TAR Public Affairs Passports Issuance and Management Implementation’ (Experimental)” and the “Notice on the ‘TAR Public Affairs Passport Retrieval and Management Detailed Implementation Measures’ (TAR External Affairs Doc [2007] No. 53)” issued by the TAR External Affairs Office, and in accordance with the spirit of the “Notice on Printing ‘Diplomatic Passport, Service Passport and Public Affairs Passport Issuance and Management Measures’ (MFA Doc [2006] No. 23).”

- All tour groups and individuals traveling abroad on public affairs who apply for a public affairs passport must handle formalities though application channels for going abroad on public affairs. Public affairs passports must be returned to the agency nominated by the issuing department within seven days of returning to the country for safe-keeping or for cancelation. Individuals or work units which delay handing in passports or who do not carry out document management provisions shall be temporarily prevented from going abroad on public service.

- Strengthen passport management for foreign travel by enterprises and work units in our region, increasing the rigor of approvals for public affairs passports for going abroad on public affairs, and put an end to ordinary passport-holders going abroad to conduct public affairs.

Copies sent to:

TAR Military District Political Department, Air Force Lhasa Command Office Party

TAR Party Committee General Office Private Secretary’s Office. Printed on April 29, 2012.

Appendix III

TAR regulations issued May 6, 2012. Unofficial translation from Chinese.[62]

TAR Regulations on Strictly Forbidding Exiting the Border to Participate in Splittist Activities Such as the Dalai Clique’s “Kalachakra”

(May 6, 2012, Promulgation of Tibet Autonomous Region People’s Government Order No. 110, effective from the date of promulgation.)

Article 1:

In accordance with the provisions of the “PRC State Security Law Implementation Measures,” “Religious Affairs Regulations” and relevant Entry and Exit Administration laws and regulations, it is forbidden for all residents within the administrative area of the autonomous region to leave the country in order to participate in any form of splittist activity such as the “Kalachakra” [Ch.: fahui] held by the Dalai clique.

These regulations are formulated by integrating the realities of the autonomous region.

Article 2: