Silenced and Forgotten

Survivors of Nepal’s Conflict-Era Sexual Violence

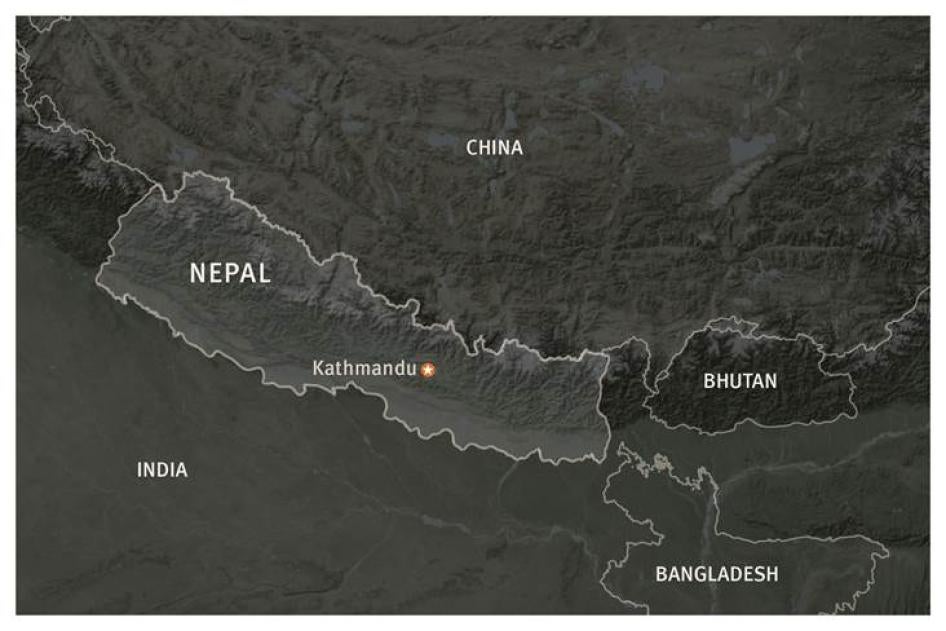

Map of Nepal

Summary

Nepal’s decade-long civil war between government forces and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) (CPN-M) claimed more than 13,000 lives and left at least 1,300 people missing. Until the 2006 peace agreement both government security forces and the Maoists were responsible for grave human rights abuses, including unlawful killings, torture, and enforced disappearances.

What has remained largely undisclosed is the sexual violence that occurred during the conflict. With the assistance of Advocacy Forum, a Kathmandu-based human rights group, Human Rights Watch researchers met with dozens of women, a few of whom described rape and sexual assault that occurred when they were still children, including one who was 12-years-old at the time.

Both security forces and Maoist combatants committed physical, verbal, and sexual violence. Members of the security forces raped and sexually abused female combatants after arrest, and targeted female relatives of Maoist suspects, or those they believed to be Maoist supporters because they provided food and shelter. Maoist combatants raped women who stood up to them and refused to support their party’s activities. In some cases we documented, women were targeted if they were found alone; in other instances, male relatives were nearby and could not or did not intervene.

Nepal’s government has acknowledged that women suffered rape during these years. Yet it has failed to deliver on its promise to end impunity for abusers, or to seek justice and reparations for victims of human rights violations. These include victims of sexual violence who are excluded from the Interim Relief Program (IRP) that compensates individuals whose family members were killed or disappeared during the war.

Furthermore, the government has yet to introduce comprehensive medical or psycho-social programs to benefit survivors of sexual violence from the conflict-era and help them to cope with the long-term consequences of violence. These could include physical ailments such as chronic pelvic pain, gynecological and pregnancy complications, back pain, migraines, premenstrual syndrome, and gastrointestinal disorders. Many women also spoke of ongoing emotional and mental distress, sometimes fueled by rejection or ridicule by husbands, family, or the community.

“[S]ometimes when he gets very angry he brings it [the rape by Maoists] up and says I am a loose woman and I should get out of the house,” Santoshi, who was raped by two men in 2006, said of her husband. “His behavior towards me changed after this happened. We were happy before this…. I feel worthless.”

To this day, fear of stigma and abuse means that many women have never told their families, or even their husbands, about the abuse they suffered.

In March 2013, the government passed a Truth and Reconciliation Commission ordinance that called for a high-level commission to investigate serious human rights violations committed during the 1996-2006 armed conflict. Troublingly, however, it granted the commission discretion to recommend amnesty for perpetrators. In January 2014, Nepal’s Supreme Court struck down the ordinance, and directed the government to produce a bill consistent with Nepal’s obligations under international law, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child which prohibits sexual violence.

The following month, in February, Sushil Koirala of the Nepali Congress Party was nominated prime minister of Nepal. The new Constituent Assembly is expected to draft a constitution to make good on the peace agreement, which includes among other things, the promise of justice and accountability for the conflict’s victims. However, one of the first actions of the new government was to enact a law establishing the Commission on Investigation of Disappeared Persons, Truth and Reconciliation, which falls short of the January Supreme Court directive. It has been challenged through public interest litigation before the Supreme Court. The case has been heard, and a verdict is pending.

However, renewed momentum around a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), and the drafting of a new constitution, means there is now an opportunity to rectify these historical injustices and ensure accountability for conflict-era rape and other forms of sexual violence.

The new government should take immediate steps to investigate sexual violence during the conflict, hold those responsible to account, and ensure that victims receive effective remedies including medico-psychological counseling and reparations. It should also remove significant barriers to justice, including a 35-day reporting limitation from the date of a rape, and amend the rape laws to include other forms of sexual assault.

Physical, Verbal, and Sexual Assault

Women and girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch described being verbally, physically, and sexually assaulted by both sides in the conflict, although there were fewer accounts of sexual violence by Maoists.

Sometimes the rapes were carried out by a single assailant; in other cases, women described being gang-raped. In some instances, the women said they had lost consciousness during the attack and did not know for sure how many men had raped them. Human Rights Watch documented at least four instances where sexual assault by the security forces included insertion of objects inside women’s vaginas, forced oral or anal sex, or forced masturbation. In one case, a woman said that police had rubbed salt and chili powder into her vagina.

Some women, including Nandita, described being raped as their children looked on, and of being wrested from infants that they were holding. “He was crying a lot, and had been slapped a few times by the men,” Nandita said of her son, who witnessed her assault. Manorama was raped in 2002 just 11 days after giving birth, while she was at home recovering from childbirth. In a few cases, women had children because of the rapes, or suspected the children they subsequently bore were the result of their attacks.

In most cases, the sexual assaults were accompanied by verbal attacks that included calling the women derogatory names, such as randi (whore), and dire warnings not to tell anyone about the incident.

A few women also described horrifying physical attacks, often preceding the rape. When Rekha resisted her attacker, a Maoist combatant, in 2003, he hit her so hard that the skin from her skull and forehead came off, and hung “like a curtain” in front of her face. She received 36 stiches.

Human Rights Watch researchers documented cases where women or girls who were Maoist combatants or relatives of Maoist combatants were illegally detained, tortured, and raped in custody. Gayatri, a minor at the time, was a secondary school student when Maoists forcibly recruited her. Government forces captured her in 2001, and, she says, raped her while she was illegally detained at an army camp, leading to severe vaginal bleeding:

The rapes would start only at night and continued for many days. I was blindfolded throughout. My hands were untied after the first few days. There were around five or six officers every night.

Security forces also raped women during search operations, often in their own homes, particularly if they were relatives of Maoists. Women said they were punished for providing food and shelter to the Maoists whose demands, they said, they could not refuse.

Human Rights Watch researchers also documented a few cases of rape in Maoist custody, although far less than by security forces.

Meena angered the Maoists because she refused to join their indoctrination programs. She was abducted in April 2004 while gathering wood in the jungle. She spent about four months with the Maoists, moving from place to place with them, and said she was repeatedly raped, including gang-raped, before she escaped.

The first time I was raped was the day after my capture, in one of the goatherd huts.…Three of them came into the hut, and immediately one of them told me to take my clothes off.…They all three took turns raping me. Afterwards, they told me that I’d be killed if I dared tell anyone….

Lack of Psycho-Social Support

Even a decade after the conflict, many of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch continue to display signs of trauma, underlining the need for immediate assistance.

The government still does not have a standard protocol for the treatment and medico-legal examination of rape survivors to provide therapeutic care and secure any likely medical evidence in a timely manner. There are also insufficient training programs for doctors on the therapeutic and medico-legal aspects of sexual assault.

Access to psycho-social support services are not just important for those who have been raped, but also their immediate family and community. In some cases, women interviewed censored themselves because they were afraid of being mistreated or rejected by their husbands and in-laws. Sita, who was raped by security forces in September 2002, says her husband often becomes enraged and subjects her to physical violence because of the attack, even though more than 10 years have passed.

Advocacy Forum has facilitated some medical support when possible by connecting victims to mental health experts in the capital. But unless the Nepal government ensures that survivors of sexual assault and their families can seek counseling through government health services to cope with sexual assault and its fallout, it will be difficult for individual nongovernmental efforts to reach out to women systematically and help them to overcome stigma or prevent domestic violence.

More importantly, the government has an obligation to provide such services for survivors of sexual assault and their families, especially where the psycho-social impact deters them from seeking justice. The government should also expand its efforts to provide interventions to curb domestic violence, which will also assist rape survivors who experience domestic violence as a consequence of the rape.

Lack of Medical Treatment and Documentation

The lack of medical and psycho-social services during the conflict made it all the more difficult for survivors of rape to secure any possible medical evidence. For example, one survivor who was raped in February 2003 went to a doctor and reported the rape because she was anxious about HIV transmission. But the doctor, a private practitioner, did not have the training to provide her any information about medico-legal evidence, nor did he attempt to gather such evidence.

Madhavi, who was raped in her village by security forces, says that initially she was too distressed to look after her injuries and also had no money. “The soldiers took all the money. How could I go to the hospital? I also did not want to live,” she said.

While most of the women did not seek medical care, those that needed treatment for injuries usually did not tell the doctor they were raped because of fear or stigma. Bipasha’s husband told Human Rights Watch how terrified they were to report how security forces raped his wife. “There was so much fear. We did not dare say anything to anyone, police, doctors, no one…,” he said.

Even in cases where women and girls had medical examinations soon after the sexual assault, they did not have access to the records, or they destroyed the file for fear of being caught with it. After the end of the conflict, it was impossible for women to secure any likely medical evidence of the sexual assault because of the time that had elapsed.

Barriers to Justice

Even though most women we spoke with described incidents of sexual violence which occurred at least 10 years ago, survivors told us that they continue to feel a deep sense of injustice at being left out of reparation and justice mechanisms.

In their interviews, the women told Human Rights Watch that a combination of social stigma and the fear of retaliation by the perpetrators prevented them from reporting these crimes soon after they occurred. Only after peace was restored did they feel emboldened to come forward and speak about their experience. It is possible that many others continue to suffer the consequence of sexual abuse in silence, fearing social stigma or because they lack faith in the criminal justice system.

Most of the women who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that it was inconceivable to them to report sexual assault to the police during the conflict, especially when the combatants were themselves the perpetrators. “They threatened to kill me if I spoke about the rapes,” said Nirmala, who was raped by Maoists.

Threats of violence and even death also deterred women from speaking at the time, and continue to haunt them years later. Radhika, who was repeatedly raped after she was taken into police custody and illegally detained for many days, said, “I remember the DSP [District Superintendent of Police] telling me before release that I wouldn’t live if I dared talk about what had happened.”

For victims who dare to report the abuse, Nepal’s criminal justice system also acts as a barrier by imposing a 35-day reporting limitation rule from the date of the rape. Acknowledging that such a rule hampers access to justice, the Supreme Court of Nepal ordered the government to revise the rule, but there has been no progress to date.

The Road Ahead: Justice and Reparations

The time that has passed since the attacks, and the fact that most women could not lodge complaints at the time, means that the Nepal government will have to take the initiative, investigate the allegations, and identify perpetrators to the best of their abilities.

The army, police, and armed police—which shared a joint command system during “the Emergency,” as the civil war 2001-2005 period is widely known—should cooperate with such an investigation instead of protecting abusers. Maoists have also been reluctant to hold perpetrators of human rights violations to account. In two cases that Human Rights Watch documented, local Maoist leadership did accept the rape allegations and punished the perpetrators by publicly beating them and forcing them out of the village. Perpetrators should instead face trial under Nepali law. The Maoist system of “people’s courts” that prevailed during the conflict did not provide fair or adequate redress for such crimes.

The procedures adopted by the proposed Truth and Reconciliation Commission and any investigations and trials should be gender-sensitive and designed and adequately resourced to protect the privacy and dignity of survivors to minimize stigma and avoid re-traumatizing them and their families. It should have resources to order special victim and witness protection measures should the need arise. The government should also take special measures to encourage women to report these crimes, such as raising awareness, and ensuring each police station has female police officers who are properly trained to handle complaints of sexual assaults. Many victims say that they fear the perpetrators will be protected.

Nepal’s government should introduce a reparation program for survivors of conflict-era sexual violence that is not contingent on successful prosecution and provides compensation and other services to individuals who come forward with their experiences of sexual violence. It should also include community-level interventions that address at least three critical needs of survivors of sexual violence and torture: long-term health care, mental health services, and livelihood support, especially for those who have developed disabilities as a result of the violence or torture.

If the new government is committed to justice for conflict-era abuses, it should pay immediate attention to assisting those who, for years, are suffering the consequences of sexual violence that they endured.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Nepal

- Ensure that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission or any other independent commission is specifically tasked with a mandate to investigate allegations of conflict-related rape and other forms of sexual violence.

- Develop, in consultation with local women’s rights groups and women from conflict-affected communities, a reparations program that meets international standards.

- Implement legislative, policy, and programmatic changes as part of a larger reparative framework to rectify underlying legal, policy, and programmatic barriers or gaps that prevented conflict-era rape survivors from seeking justice.

- Ensure women’s participation in the peace process, including in any truth commissions, and ensure that the commissions comply with international standards.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted the research for this report in collaboration with Advocacy Forum, a Nepali nongovernmental organization that specializes in documenting human rights violations and seeking legal redress.

For several years, Advocacy Forum has facilitated medical treatment and legal assistance to those affected by the 1996-2006 conflict in many parts of Nepal. In the course of its work, Advocacy Forum learned of women’s experiences of different forms of sexual violence during the conflict. [1]

In April-May 2013, Human Rights Watch worked with Advocacy Forum to identify women willing to be interviewed about their experiences of sexual assault during the conflict. Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with over 50 women. A combination of immense social stigma attached to sexual assault, fear of retaliation, and women’s inability to travel to a safe location for interviews narrowed the pool of women whom Human Rights Watch was able to interview.

Several women shared their experiences of sexual assault that occurred when they were still children under the age of 18.

Due to logistical constraints Human Rights Watch was only able to interview women who lived primarily in the southern Terai region. Human Rights Watch chose this region because it is home to indigenous Tharu and other disenfranchised communities which have long been isolated and ignored by the ruling elite in Kathmandu, and witnessed intensive anti-Maoist operations during the conflict because Maoists found support there.

Human Rights Watch also chose districts in the western hill regions where the Maoists held control. We gathered information in cases where either security forces or Maoist combatants were identified as perpetrators.

Human Rights Watch findings in this report are not quantitative, but show that sexual abuse during the conflict may have been common, and broader documentation is needed once the state is able to provide adequate witness and victim protection, counseling, and other support.

In addition to interviews with women who experienced sexual violence, Human Rights Watch interviewed family members, doctors and counselors, activists, government officials, and donors.

Human Rights Watch interviewed only those women who were willing and able to travel to a safe location away from their village to meet with researchers. We took measures to respect the privacy of survivors and conducted interviews in as private a setting as possible. In five cases the women told Human Rights Watch that they preferred to have their husband or another support person of their choice present for a part of or the entire duration of the interview and we respected their wishes.

All interviews were conducted with full and informed consent. We also obtained consent to examine their medical records on file with Advocacy Forum. The interviews were conducted in Nepali, Hindi, or English, depending on the preference of the interviewee, using a female interpreter where required. In all cases Human Rights Watch took steps to minimize re-traumatization of survivors, stopping interviews if they caused distress. We have also not included in this report statements from women who appeared uncomfortable or unable to discuss the abuse that they suffered.

In order to protect victims and witnesses, individual names and all identifying information, such as location or incidents, have been modified or withheld.

Terminology and Limitations

In this report, Human Rights Watch uses the phrase “security forces” to describe police officers, Armed Police Force (APF), or members of the then Royal Nepal Army, or a combination of all of these.

Most of the cases that Human Rights Watch documented occurred after Nepal declared a state of emergency on November 26, 2001. In earlier cases, the perpetrators were only members of the Nepal police because the APF or army was not deployed.

After the emergency was declared, the Royal Nepal Army (now known as the Nepal Army), was deployed to lead the combat against the Maoists under a policy known as the unified command. Since the army conducted joint operations with the police and Armed Police Force, including at night, survivors were often unable to distinguish between the security forces even though they were able to confirm uniformed officers.

In some cases women were able to describe the differences in uniforms worn by police officers and soldiers using characteristics like color and pattern (that is, whether it was camouflage or not), and these have been recorded. None of the women were able to specify the exact battalion or platoon to which the perpetrators belonged.

I. Background: The Armed Conflict

Over 13,000 people were killed during Nepal’s decade-long civil war between government forces and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) (CPN-M). The signing of the Comprehensive Peace Accord (CPA) put a formal end to the conflict in 2006. However, both parties have failed to deliver on their promise to seek justice for victims of human rights violations including sexual violence, and to end impunity.

Government Acknowledgment of Sexual Assault during Conflict

In February 2011, nearly five years after the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed, Nepal’s government introduced the National Action Plan on Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820. In this plan, the government acknowledged that “women also suffered from sexual violence during the conflict as well as the transition period due to the weak law and order situation.”[2]

The National Action Plan also acknowledges the need to hold perpetrators accountable for such violence, stating: “There is a need to take legal action against those involved in different offences during the conflict period, and improve conflict affected women and children’s access to justice.”[3] Describing a justice system that deals with conflict-related sexual violence as the “need of the day,” the Nepal government committed to implementing a “gender-sensitive” justice mechanism and recognized that it is “essential to make necessary amendments in the existing laws.”[4]

The National Action Plan describes as “inevitable” the “formulation of laws, policies, and programs for addressing gender-based violence that took place during the conflict and the transitional period and their effective implementation.”[5]

However, to date, the Nepal government has yet to take action to bring about such legal reforms and introduce programs to benefit survivors of sexual violence from the conflict-era. Programs responding to the needs of survivors of the conflict—especially women who experienced gender-based violence—are critical to assisting victims in coping with the long-term consequences of violence, including chronic pelvic pain, gynecological and pregnancy complications, migraines and other frequent headaches, back pain, pre-menstrual syndrome, and gastrointestinal disorders.[6]

Momentum for Law Reform on Sexual Assault

As the Nepal government has itself recognized, its antiquated laws governing sexual assault urgently need change.

The Nepali criminal code criminalizes rape, sexual assault, and sexual harassment of women, and contains provisions making it a crime for officials to have sexual intercourse with women in certain situations. But hurdles such as the 35-day statute of limitations on reporting sexual violence remain in place. A process of drafting a new penal code, criminal procedure code, and sentencing law has been underway for the past several years, but is fraught with delays.

Public outcry following the December 2012 rape of Sita Rai[7] (see below) by a police constable resulted in some momentum for reform of laws governing sexual assault. The case triggered what is commonly known as the “Occupy Baluwatar” protests, which lasted over three months. In response, the government constituted a committee to look into sexual assault laws and recommend changes, which submitted its report in January 2013.[8]

However, in March 2014, former Home Secretary Navin Kumar Ghimire told Human Rights Watch that the relevant government departments had yet to submit recommendations.[9]

Sita Rai and the Momentum for ReformWhen she was 16, Sita left Nepal to work as a domestic worker in Saudi Arabia. To bypass a Nepali law that prohibits women below age 30 from migrating out of the country for work, Sita traveled on a fake passport. When Sita returned three years later in December 2012, her fake passport was detected at the Kathmandu airport. In exchange for dropping charges, the immigration officer confiscated her savings of 9,500 riyal (2100 US dollars). Offering assistance to the now penniless woman, police constable Parsuram Basnet tricked Sita into a nearby lodge, and raped her.[10] Sita Rai’s story triggered public outrage. On December 28, 2012, a crowd assembled in front of then-Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai’s official Kathmandu residence in Baluwatar, to hand over a letter demanding an investigation into Sita Rai’s case. The gathering turned into a protest against the increasing incidences of violence against women and gained momentum as the Occupy Baluwatar movement. Representatives of the movement made several demands of the Nepal government. These included the arrest of perpetrators of sexual violence with warrants against them, amending rape laws to drop the 35-day reporting limitation period, lifting the ban on women under 30 from traveling to work abroad, and ensuring at least one third representation of women in parliament. In response, Bhattarai set up a commission of inquiry to look into and implement the activists’ demands. Several charges were filed against four officers implicated in her abuse. The Occupy Baluwatar movement went on for 105 days, gaining support from Nepal’s leading civil society activists, the public, and the media. |

National Law

The Nepali criminal code, the Muluki Ain, criminalizes rape, sexual assault, and sexual harassment of women, although rape is limited to penile penetration of the vagina and does not extend to oral, anal, or other forms of sexual penetration. The law does contain provisions making it a crime for officials to have sexual intercourse with women in certain situations, including when in government custody, but does not extend to superior or command authority liability. The Supreme Court of Nepal has ordered revision of the law because the 35-day reporting limitation period is “unreasonable” and “unrealistic,” and is a barrier to justice for rape survivors.[11]

Nepal’s Obligations under International Law

Nepal is a state party to many international human rights treaties which prohibit sexual violence, including rape, and torture. These include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),[12] the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment,[13] the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW),[14] the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC),[15] and the Geneva Conventions.[16]

In addition to the instruments mentioned above, customary international humanitarian law also prohibits sexual violence, making clear that these prohibitions apply to both sides of a conflict.[17]

The definition of sexual violence that international law prohibits is broad and has been interpreted through international jurisprudence to include rape and other forms of sexual violence.[18] In addition, certain forms of sexual violence during an armed conflict may constitute torture, and international law does not allow any derogation from the prohibition against torture.[19]

The UN has, through various security council resolutions, made clear that there must be national accountability for crimes of sexual violence and has pledged to support countries in holding perpetrators to account, particularly through the comprehensive Resolution 2106, adopted in June 2013, which reaffirms prior resolutions and sets out detailed ongoing concerns and recommendations on how to proceed to address sexual violence during armed conflict.

In light of its international and national obligations, Nepal has a duty to reform its criminal laws to recognize all forms of sexual violence and eliminate the 35-day limitation period that is a barrier to reporting and investigating sexual offences. In 2011, the CEDAW Committee (tasked with interpreting and monitoring state party compliance to the treaty) recommended that the Nepal government “take immediate measures to abolish the statute of limitation for registration of cases of sexual violence to ensure women’s effective access to courts for the crime of rape and other sexual offences.”[20]

Nepal should also incorporate command or superior responsibility as part of its criminal law for international crimes including war crimes and torture.[21] It also has an obligation to independently investigate and prosecute through civilian courts allegations of sexual violence committed by both sides to the armed conflict.

The government has an obligation to direct investigative and prosecutorial authorities to pursue accountability, no matter how high ranking the alleged perpetrator, and no matter which political party is in power. Moreover, the government needs to ensure judicial independence and ensure that its investigative and prosecutorial authorities respond in a timely and cooperative manner to Supreme Court and other court directives.

Nepal should also make effective reparation to victims in accordance with the UN Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims.[22] According to these principles, “a person shall be considered a victim regardless of whether the perpetrator of the violation is identified, apprehended, prosecuted, or convicted”[23] and the term “victim” also “includes the immediate family or dependents of the direct victim and persons who have suffered harm in intervening to assist victims in distress or to prevent victimization.”[24]

Reparation for serious violations of human rights, including sexual violence, can take different forms and may include restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, and guarantees of non-repetition.[25] While providing reparations, Nepali authorities must also realize the serious impediments to accessing reparations for particularly disenfranchised groups, which include women and victims of sexual violence, and ensure that systems are in place to reach these victims and provide reparation to them. Any reparation program should be designed in consultation with victims of sexual assault and be in accordance with the UN Secretary General’s Guidance on Note on Reparations for Conflict-Related Sexual Violence.[26]

In January 2014, the Nepal Supreme Court rejected the Truth and Reconciliation Ordinance as unconstitutional, and directed the government to bring it in line with international law to ensure that perpetrators of serious human rights and humanitarian law violations are not subject to an amnesty.[27] Just three months later, the government responded by submitting and passing into law a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) bill, which essentially copies the previous one.[28]

Although rape and serious crimes are specifically mentioned in the new draft as a crime for which no amnesties are allowed, the failure to specify what constitutes serious crimes is problematic. Torture, for example, is not criminalized in Nepali law, and the vagueness of the draft bill means that perpetrators of torture could be amnestied.

In its concluding recommendations to Nepal, the CEDAW Committee specifically reiterated the need to ensure that any Truth and Reconciliation Commission is gender sensitive and “pays attention to the social and security dimension of public testimony for victims of sexual violence.”[29]

II. Sexual Violence by Security Forces

During the conflict, many have described an overall climate of fear where civilians were caught between Maoist combatants demanding support, and security forces reacting angrily to any support for Maoists, coerced or otherwise.

This section provides in-depth accounts of specific episodes of sexual violence perpetrated by security forces against women and girls. The nature of sexual assault itself varies and includes molestation, and penile and other forms of penetrative sexual assault.

Climate of Fear and Sexual Harassment

Almost all women who spoke to Human Rights Watch described widespread fear of sexual harassment and mistreatment, and said that the anti-Maoist security force operations in their villages were generally abusive. In addition to violent raids that included beatings, security force members made derogatory and sexually humiliating comments while addressing women and girls, particularly relatives of combatants or those suspected of providing food or shelter to the Maoists.

Daya recalled that on many occasions, troops would “kick the door open and say ‘Eh randi (whore), get up.’”[30] The raids, which occurred daily and often several times a day, were stressful. “I had become really thin. I didn’t have proper sleep. I used to be worried all the time.” Although it did not eventually work, to protect herself from sexual mistreatment, she said she would pick up her little son in her arms, hoping it would serve as a deterrent.

Every time they [security forces] came, I used to grab my four-year-old son and hold him in my arms. It didn’t matter what he was doing—even if he was sleeping—I’d grab him and wake him up. I used to think maybe if they saw a child in my arms they would take pity and wouldn’t touch me.[31]

Jyotsana, who lived with her family, said security forces would beat villagers, including women—accusing them of supporting the Maoists.

When they came at night—both army and police would come and bang on our doors and kick and wake us up. Other times, they would come walking and surround the village and ambush people who had gone out to go to the toilet. Even if we went to the cornfields sometimes they would come catch us and beat us and use filthy language to address us—randi, beshiya [whore]. They kicked and pulled us by our hair.[32]

Targeting Maoist Combatants, Relatives, and Individuals Alleged to have Aided Maoists

Human Rights Watch documented several cases of sexual assault during interrogations either in police or army custody, or during police or army visits to the homes of relatives of Maoist suspects or families suspected of aiding Maoists. There was a striking similarity in cases from the different districts indicating that sexual assault was used to terrorize and gather “intelligence” on Maoist movements, or as a form of revenge for Maoist affiliation.

Rape, Torture, and Cruel, Inhuman, and Degrading Treatment in Detention

Human Rights Watch documented serious cases of torture including repeated sexual assault of women and girls in police or army custody. None of them were detained by or in the presence of female police officers, nor did they see a female police officer during detention. Only one interviewee told Human Rights Watch that the police framed terrorism charges against her. But she recalled being produced in court and being allowed access to lawyers only after spending many months in army custody in different barracks during her detention period. Family members were not informed of the detention.

In four cases, the women reported that they had been children under the age of 18 who were studying in school when they were detained and raped. In all of these cases, Maoists forcibly recruited or persuaded the children before being captured by security forces.

Gayatri, 2001

Gayatri, a student, had several relatives who were Maoists, and combatants often used to come to her village for food and shelter, and beat those who refused to help. In the winter of 2001, a group of Maoists came to her class and forcibly recruited five students, including Gayatri, who was a minor at the time, promising to send them back home within two or three days. When Gayatri protested saying she needed her parents’ permission, the Maoists warned that they would kill her and her parents if she did not comply, and forcibly recruited and armed the five students with grenades.[33]

After days of walking through the jungle, Gayatri fell sick and the Maoists left her and her friends in a village. One day, as she was bathing under a tap, she was surrounded by security forces. “Suddenly I felt like there was green everywhere. I looked behind me and everywhere I looked there was the army,” she said.[34]

Security forces found the grenades, and refused to believe that Maoists had forcibly recruited Gayatri and the other students. After blindfolding and binding their hands, they took her and her friends into custody.

Gayatri was first threatened with rape when she was detained overnight at a makeshift camp, where her blindfold was temporarily removed. “They [security force members] just talked badly to us. They said, ‘You are bad people. The Maoists must have raped you. We’ll also rape you and leave you.’” The next day, security forces transferred Gayatri and her friends to an army camp where they were separated. Gayatri did not see her friends again.

The rapes began from the first day. She was still blindfolded. The first time the man who came in to take away her dinner plate raped her. Soon it became a pattern. Men entered her room on some pretext or the other—of giving her food, water, clearing the dishes, or taking her to the toilet—and raped her. During the days she was interrogated and beaten and at night she was raped. Gayatri also described how she was forced to provide oral sex or masturbate the men.

The rapes continued for many days. I was blindfolded throughout. My hands were untied after the first few days. There were around five or six officers every night.[35]

If Gayatri protested, they kicked and beat her. On one occasion she screamed and the man who was in the room hit her on the forehead with a rifle butt, leaving a scar, still visible, on her forehead. They threatened to kill her and her parents if she told anyone about the rapes.

Gayatri estimates that she was detained there for about 25 days and that she was raped for 12-15 of those days. She began to have heavy vaginal bleeding because of the rapes and described how she used her petticoat to absorb blood, washing it every day when she was allowed to use the toilet. She also told Human Rights Watch that the room where she was detained was dirty and smelled of dried blood.

After seeing her plight, one of the officers in the army camp organized her release. She gave him her aunt’s number who came to take her home. The first time her aunt came, the army officer told her to return with a set of clothes for Gayatri. Before she left the army camp, Gayatri was told to throw away the clothes she was wearing, put on the fresh set of clothes.

After her release, Gayatri confided in her aunt who took her to a hospital for medical treatment and an HIV test, which was negative. They destroyed the records because they did not want anyone else to find out. Because she was blindfolded for a longtime, Gayatri felt it caused her problems with her eyesight soon after her release, lasting over a month. “My eyes tear a lot. I used to have severe pain when I opened and closed my eyes. I got headaches.” The beatings during her detention weakened her back, making it difficult for her to work, she said. She continues to have nightmares.

Gayatri has since married. She wants justice but she is too scared to report the case because she does not want her in-laws and husband to find out.

Diksha and Basanti, 1999

During the conflict, Diksha lived with her family. Her father was a Maoist and was not living with the family. She said the police with “plain blue dress without patterns” started coming to their house to inquire about his whereabouts but the family had not seen or heard from him. She recalled that groups of 10 or 12 police officers turned up frequently at any time of day or night.

In November 1999, when Diksha was still a minor, a group of what seemed like 24-25 police officers arrived at her house in the morning when she was cooking. There were no women police officers in the group. They started interrogating everyone about Maoist whereabouts and beat her, her brothers, and her mother. “They kept asking us about Maoists and beat us,” she said.[36]

The police blindfolded her and her mother and took them to the police station, kicking, beating, and pulling their hair en route. “They threatened that they would kill us. They kept calling us ‘Randi, raadi, wives of Maoists,’” said Diksha.

They reached the police station after sunset. She was separated from her mother and taken to a room that she later learned was where the police inspector slept. The police officers interrogated and tortured her in the room.

In the room, they handcuffed me and shackled my legs. I was sitting on the floor when a drunk officer entered and started shouting at me using filthy language. He started beating me with a stick, all over. I was leaning against a wall and sitting with my legs outstretched. He stepped on my knees and started beating me on the soles of my feet with a stick.[37]

After beating her, the police officers raped her, she said. She recalled that there were several men in the room and they together overpowered her: “I heard about three or four men in the room. One officer stepped on my legs, another held down my hands, someone closed my mouth.…” She said one of them proceeded to rape her with what she felt was a stick.[38]

Diksha told Human Rights Watch she fell unconscious and could not recollect other details. She woke up to find herself handcuffed to a pillar; her body was swollen, and her clothes torn. She needed to go to the toilet, but could barely walk because of severe pain. In the end, the policemen had to help her walk to the toilet downstairs. She found it difficult to pass urine. She recalled that she was bleeding and there were blood clots in her urine.

For a little more than two weeks, Diksha says she was kept in detention and beaten. She recalled being raped at least on three separate occasions. On the third occasion she said she was not blindfolded when raped and saw that it was the “inspector” who raped her. She could smell the alcohol on his breath and guessed it might have been the same man who was involved in the previous rapes because the alcohol breath seemed familiar. She was not produced in court or allowed contact with any relatives while she was in detention.

Human Rights Watch spoke to Basanti, Diksha’s mother, who was also detained in the police station and released with her daughter. Basanti said she was beaten, including with nettles. She showed scars from the beatings on her left shin and her arm where she was hit with a rifle butt. Basanti said she was also blindfolded and raped with an object that she thought was a stick. She felt a surge of intense pain and passed out. “When I regained consciousness at night I found that my legs and groin area were swollen and I had bruises,” she said.[39] Basanti was beaten so badly that she developed severe back pain and for a while lost all sensation in one of her toes.

She and her daughter were released after more than two weeks in police custody on the condition that they report at the police station every day. After they were released, they feared being killed and joined the Maoists for protection. They went to hospitals for medical treatment, but lost their medical documentation in another village raid by security forces.[40]

Shakti, 2003

Shakti was a minor in secondary school when members of the Maoist party came to her school to recruit students. She became a combatant and was a member of the district squad and platoon for about nine or ten months, and then mostly engaged in spying for about a year before the Nepal Army captured her.[41]

In 2003, she and another combatant had sheltered in a village, in a civilian’s house, when she said soldiers arrived at night and beat the house owners for sheltering Maoists. Shakti had a pipe bomb with her, which gave her away. The soldiers blindfolded and tied her hands, and hit her with the rifle butt. Because of her work as a Maoist combatant, Shakti was able to clearly identify that those who took her into custody were from the army.

She recollected regaining consciousness and discovering that she was almost buried under the soil. “I found that my entire body was under the soil. They had dug up the ground and buried me, and my face was above the ground,” she said.[42]

When they saw her conscious, they pulled her out of the soil, covered her mouth, and poured water into her nose. Soldiers kicked her all over, including on her chest and vagina. They threatened her with forced oral sex. Shakti was blindfolded and did not know how many officers were there but estimated there might have been five or six around her.

The next episode of torture she recalled occurred about six months later, during her detention in the barracks where she said she was routinely interrogated about Maoist leaders and their whereabouts.

Describing the torture she suffered blindfolded, Shakti said: “My legs were lifted and tied and my hands were tied too—it was like a V-shape and I could feel something sharp poking my back.” They passed electric currents through her feet twice a day on many days, once in the morning and at night. They beat her regularly. Shakti estimated that this carried on for two or three months.

During her detention in the barracks, which she estimated lasted about 10 months, Shakti could not recall any specific episode of sexual assault but said she had difficulty passing urine and felt a burning sensation. She could feel that all her clothes were torn. “Everyone could see me naked—everything would show,” she said. They would not even untie her hands when she wanted to use the toilet and she could not clean herself. She recalled how humiliated and dirty she felt, “I felt like I was a pig.”[43]

From the barracks, Shakti was sent to two other detention centres. In the second one, she was housed with other female Maoist combatants. She believed a handful of the female combatants there were raped. Shakti said:

There were about 45 of us—we used to cook and live together so I knew how many of us were there in the center. Of the 45 women I think about 10-15 of them were sexually assaulted. I am sure that at least five of those women were definitely raped by the army. When we used to sit down and chat they wouldn’t say it directly but they would say other things that made it clear that they were raped. One woman, for example, told us that 11-12 men came and took her and that she bled a lot after those days.[44]

Terrorism charges were framed against her, but she was released once the peace agreement was signed.

Shakti narrated how her health suffered because of the months’ long torture. “The soles of my feet hurt like they were pus-filled—I can’t describe the pain—it was because of the electric shocks.”[45] The continued suspension during custody weakened her upper body so much, she said, that she could not even carry and breastfeed her children. She is unable to work and relies on her parents’ support.

Radhika, 1998

Radhika said that the Maoists came regularly to her village and often asked her to join their programs, but she refused. In November 1998, when she was still a minor, Radhika was walking to school in a group of around 15 students when they ran into security forces. She said, “Suddenly we came upon a group of men in black camouflage uniform. They told us that we had to come with them to the police station.”

At the police station, everyone else was released but Radhika and two other girls. All three of them were detained together in a large hall, and were taken out to be questioned individually. Radhika says she was beaten during interrogation.

During the questioning, I was beaten and questioned about Maoist movements, about whether I had attended Maoist programs. There had been a Maoist procession earlier that day, so they thought that we had something to do with that. I was beaten very badly…. They kicked me against the cement wall and forced my head against it. I remember that blood started streaming down from my head and I collapsed on the floor. The first time they questioned me they put pins under my nails.[46]

On the third day, all three girls were first shifted to another police station and then transferred to the District Police Office, where Radhika was dragged into the office of the deputy superintendent of police (DSP). She said:

I resisted going, so the police officer dragged me to the office of the DSP, kicked and pushed me very violently, and threw me at the feet of the DSP. The policeman then left the room. I was alone with the DSP. I know he was the DSP because he told me so.[47]

The DSP spoke to her in a derogatory way, making unwelcome sexual comments. Radhika recalled, the “DSP started by saying things like ‘Oh, this is a pretty one, come close to me,’ and he was using dirty words.” Soon he told her to take off her clothes and when she refused, he hurled verbal insults at her, and slapped, stripped, and raped her.[48]

Radhika said this continued for about a week. She was taken for “questioning” every day where the DSP raped Radhika each time barring one occasion where another official was involved. Describing these episodes of sexual assault, Radhika said:

Each time except once, I was raped by the DSP. The one exception was when an “inspector” raped me. I was beaten and kicked each time. During some of the rapes, the DSP would call some policemen in to hold me down and cut me on my thighs.[49]

She recounted how they tortured her further by applying chili and salt powder on her cuts and in her vagina. She said, “It used to burn very badly. I remember they kept saying this is what happens to Maoists. They put pins in my nails, both on hands and feet. My finger nails fell off afterwards, I suppose because of the pins.”[50]

After about a week her cousin found out where Radhika was being held and met the DSP asking for Radhika’s release. Although the DSP insisted that he had full records on her Maoist activities, Radhika was released on parole on the condition that she should report to the police station every three days. Before her release, DSP warned her: “I remember the DSP telling me before release that I wouldn’t live if I dared talk about what had happened.”

Radhika could barely walk after she was released and her family took her to hospital where they admitted her for two weeks during which period the doctors sent notes every three days to the police station. After she returned from the hospital she continued to report at the police station every three days. Once again she got a veiled threat of torture and rape: “Eventually, the police started telling me that I should get married immediately or else the same thing would happen to me all over again.”[51]

Radhika left the district and married a year later. Until now she has not disclosed the torture or rape to her husband and in-laws. It has been nearly 15 years after the incident but she said she still suffers because of it, complaining that she cannot eat properly, bleeds heavily during her menstrual cycles, and experiences a “tingling burning kind of pain in my head” where she was hit.[52]

Jyotsana, 1996

Jyotsana lived with her family in Udayapur district during the conflict and said there were constant search operations by security forces. When she was 12, Jyotsana decided to join the Maoists because she felt they were more respectful and helpful than the security forces. The Maoists met the villagers, organized programs in schools, and promised that there would be food, dancing, and singing, she explained.[53]

Drawn by their promises, she and a cousin joined the Maoists. However, after four or five months, Jyotsana decided to leave because she could no longer endure the long treks in jungles or the lack of food. The Maoists allowed her to leave with a warning not to disclose names or hideouts. But the villagers refused to let her stay, fearing that her association with the Maoists could cause trouble with security forces.

Jytosana told Human Rights Watch that she suspected that while she was trying to find shelter in one of the villages a police informer gave her away, leading to her capture and detention. She gave a vivid description of her capture—she was hiding under the bed on the first floor of the house and she heard the security forces downstairs “searching and throwing things.” They came upstairs and found her under the bed:

I heard one of the officers loading a rifle and then another one told him not to shoot me. So the officer pointing the gun at me asked me to come out. As soon as I came out, they started hitting me with the butt of the rifle—they hit me on my face, head, back, and kicked me with their boots. They were wearing a uniform similar to what the armed police force now wears.[54]

Jyotsana told Human Rights Watch that she was dragged away and taken to another villager’s house some distance away, possibly an illegal makeshift detention center. She was detained there for two days and beaten. She was also threatened with rape:

‘Randi, you’ve been with Maoists and had sex with them. Now you can have sex with us. If you can give it to them, you can give it to us also.’ They used to say dirty things like this and beat me. Or they would hold my hands and say, ‘These are the hands that have used Maoist rifles.’[55]

Jyotsana was moved from the village-house where she was detained and transferred to various police stations where she was periodically beaten and interrogated. During one such transfer she was molested by a police officer who was accompanying her:

On the way one police officer touched both my breasts and asked me, ‘How do you like this?’ The other officers were watching and laughing. I got angry and said, ‘How would your sisters feel if you did that? That’s how I feel.’ When I said that they got angry with me. But he didn’t do it again.[56]

After spending months in police custody, Jyotsana was eventually released.

Rape and Sexual Assault during Search Operations in Villages

Villagers often suffered harsh questioning, beatings, and other abuses during search operations. However, families of suspected Maoist combatants or those suspected of assisting them were particularly at risk.

This section describes cases of women family members of Maoist suspects who suffered torture. It also includes cases of sexual abuse during search operations, including of women from families suspected of aiding Maoists. The case studies below show the nature and circumstances of sexual assault that women experienced during search operations.

Madhavi, 2004

Madhavi lived with her husband, his brother, and her brother’s wife during the conflict. The Maoists used to come to their home often, demanding food and shelter. In August 2004, some Maoists came to their house and asked them to keep a suitcase for them. “They said they would take it soon. We said, ‘We are scared of the army.’ But Maoists said nothing will happen,” Madhavi said.[57]

A few days later, at around 8 a.m., troops surrounded the house. Madhavi told Human Rights Watch that she was not aware that her husband and his brother were Maoist supporters. She was taken aback when her husband produced a gun that he had hidden away. “The soldiers were beating us. Finally my husband showed them the gun he had hidden inside the cowshed,” she said. They beat them and asked for more weapons but did not find any. She recalled, “One of the soldiers said, ‘She has lied. She is a Maoist as well.’”[58]

They separated Madhavi from her husband and dragged her into a cowshed. Describing what happened, she said:

They kicked me as if I was a football from here to there. When the first person raped me, I was conscious. But there were four or five people inside the shed, and I don’t know how many others raped me. I was unconscious…. I remember one person that raped me. He looked like a demon. I was told that he is a major. [59]

When she recovered some time later she found herself lying in the shed. Her clothes were torn, and she was covered in cow dung. She was swollen and bruised and had difficulty walking, she told Human Rights Watch, describing how she struggled to walk back home from the shed.

The soldiers had left, and had taken away her husband and brother-in-law. The family was anxious and frightened about their disappearance. Within a few days, with the help of villagers, they found the two men’s dead bodies and buried them. [60]

When news of the two deaths spread, some human rights activists visited the family, and they took Madhavi to the police station to file a police complaint regarding the killings. She did not mention her rape. “How could I say anything to them? The police said we were Maoists.” The activists also took Madhavi to a hospital first in a nearby city, and then to Kathmandu. She says she had rib and back injuries from the beating. Her three-year-old son, who was also traumatized by the violence, also received treatment, she said.

Madhavi told Human Rights Watch that she still felt the damage that was done to her body. “I have pain in my body. Heavy lifting is painful.” Madhavi also wanted “punishment for those people” and “compensation.”[61]

Meera, 2003

During the conflict, Meera said that there were heavy security patrols in the district where she lived. Meera told Human Rights Watch that Maoists used to come and ask for food, or for shelter. “We were stuck in between. If the Maoists said to ‘give food’ and we refused they were angry. But if we helped the Maoists, the army was angry.”[62]

In August 2003, security forces arrived in the morning, the day after Maoists had stayed in her house and left. At the time the forces came, her husband had left for work and she was alone with her six-month-old daughter. “The men surrounded the house and started inquiring about the Maoists. “Do you have Maoists in your home? Did you give food to them?” she said, describing how they questioned her.[63] When she denied having assisted the Maoists and went inside the house to feed her six-month-old child, four members of the security forces followed her inside.

One of them snatched the baby from her breast and threw her to one side, hurting and leaving the baby wailing. They continued to question her about the Maoists, and started beating her. Recalling how they forced her on to the bed and threatened to kill her, Meera said:

Then they threw me on the bed. I cried and shouted. When I cried, they kicked me in the face. They threatened to kill my daughter and to kill me.… One after another they raped me.[64]

Meera says she became unconscious. When she regained consciousness, she did not see the men around. She saw that she had “welts on the back from the beatings” and cuts on her lips and cheeks. “I could not even get up,” she said describing the agony she was in. Neighbors came and found her in that state some time later.

The rapes left her traumatized and shocked. “I could not eat. I was just lying there,” she said. When her husband returned from work that evening, he learned from her neighbors what had happened. “He felt helpless and started crying,” Meera said.

The following day, a neighbor took her for a health check but she did not tell the doctor about the rape. Meera could not do anything for three months after she was raped. She was unable get up. The neighbors cooked for the family and took care of the baby. After three months, when she went back to the doctor, she learned that she was pregnant:

I knew that it could not be my husband’s child since I had been sick before the security forces came. So I knew that the child was because of the rape, of those officers who raped me. I couldn’t even abort the child since my health condition was so poor. My husband also said not to abort the child.[65]

Meera has a daughter from the rape, and had two sons after that. While there was no trouble with her pregnancies, she says that her health condition is not good.[66] She wants financial assistance.

Parvati, 2003

Parvati lived with her husband and children during the conflict. Many people from the area had joined the Maoists who used to routinely seek food and shelter from the villagers. During 2001-2002, Parvati says that civilians were routinely targeted during intensive security operations in the area.

One day in February 2003, security forces arrived at her house when Parvati’s husband had gone to the market and she was alone at home with the children. She was inside cooking, while the children were outside. Security forces came inside and started questioning her about Maoist whereabouts and searching her house.[67]

[O]ne of the men grabbed me by the neck and dragged me to the corner of a room. The other two were outside. He ordered me to take off my clothes. I refused. ‘Why should I take off my clothes?’ He had a gun over his shoulder. He said, ‘I will kill you.’ He then pushed me against the wall…. then he raped me.[68]

He then warned her against telling anyone of the rape. Parvati says that she remained inside the house while the man went outside and joined the search operation. When her husband returned, Parvati told him and a neighbor. The neighbor took her to a medical center and told the doctor she was raped but he gave her medication without examining her, she said. Parvati wants justice and compensation for what was done to her.

Daya, 2003

Daya is one of her husband’s two wives. Both wives lived in the same house with the parents-in-law and the husband’s brother and his family. One a night in January 2003, when security forces arrived on a search operation, Daya’s husband was with the other wife in a different room. Daya was asleep and her little son was with her. Security forces woke her up:

It was dark. The men shone a torch at me. I woke because of the light. I could not see anything. For a second I thought it was my husband. But there were two people inside my room, and they were in boots and uniforms. They pulled the blanket off me. It was cold and my baby started crying…. One of the men had gone into the adjoining kitchen. He said, ‘Why do you have so many utensils. Are you cooking for the Maoists?’ I said we were a big family…. Then they started forcing me. I can’t describe what they did. They did so many things. I lost my mind. It is a matter of shame…. After the first one raped me, I tried to snatch the blanket back, but the second one pulled it away. He raped me too.[69]

Daya told Human Rights Watch that when she told her husband what happened he was angry. He asked why the other women in the house had not been raped, considering that the security forces had searched the entire house. He called her a prostitute. But the other relatives pointed out that only she was alone that night. The rest had their husbands in the room when security men started their search.

Daya said she went to the local primary health care center, where she did not say anything about the rape because she was ashamed and got some medication for stomach pain. Daya, at a minimum, wants compensation. She says her husband no longer takes care of her since the rape.

Sita, 2002

According to Sita, in mid-September 2002, there was a big security operation in her village. The area was cordoned off. Villagers reported gunfights between Maoists and security forces.

Security forces came to their village often, interrogating and warning them not to assist Maoists. “They said, ‘You give food to the Maoists and shelter.’ Every day they used to ask us about the Maoists. They would tell us not to help the Maoists,” she said recounting how relentless the questioning was. She also recalled the threats they received from the security forces: “‘If we find out that you have provided support we will kill you.’”[70]

Sita described one such visit by security forces. They arrived when the rest of the household was asleep but she had woken up very early. While the others were outside, two men came into the house to question her. That morning, the interrogation irritated her and she retaliated: “Maoists come in the night. If we don’t give them food and lodging, they shout at us, threaten us. What do you want us to do?”

Angered by her response the security forces started using derogatory language, pushed her on the floor, and started beating her. Then, while one of the men stood guard, the other raped her. She says she thought that her attacker was the senior officer, because he ordered the other man to wait.

He pushed me on the floor. He beat me. And then he raped me. The other officer was outside the door. After he raped me, both of them went away. I was very scared.[71]

After they left, she asked her husband why he had not come out of his room to help her. He expressed his helplessness because he was threatened: “There was a man standing at the door and he threatened to kill me.”[72]

Sita and her husband did not file a police complaint. They were too frightened. She says she cannot forgive her husband for not trying to come to her rescue, and they often fight.

Asha, 2002

The village where Asha lived during the conflict was a Maoist stronghold, which witnessed intensive security force operations. According to Asha, initially the local police used to patrol the area. But because Maoists had bombed the police station, the Nepal army was deployed, conducting joint operations with the police. Asha’s brother-in-law was a Maoist and security forces targeted the family for questioning.

Asha’s husband, who also spoke to Human Rights Watch, said he suspected that the village informer tipped off the security forces, leading to repeated visits to their house for interrogations about his Maoist brother. Asha and her son were alone one night in September 2002 when her husband was away to meet a sick relative.

They came late at night and knocked on my door. I woke up. They ordered me to open the door and said they would otherwise break down the door. I opened the door, and one officer came inside. When he saw I was alone, he took my hand, pulled me to the bed and made me lie down. He threatened that if I shouted, he would kill me. I tried to escape but failed. He was stronger. He raped me. Before he left, he warned me, told me not to tell anyone. I was very scared…. I could not sleep. I went to my neighbor’s house. I did not say anything about the incident.[73]

Asha told her husband the next morning. He told Human Rights Watch that he took his wife to a doctor immediately because he worried that she might get pregnant. They informed the doctor she was raped and got some medication.

Asha and her husband are skeptical about justice because she said it would be difficult for her to single out the rapist; it was a big operation and soldiers had arrived in six or seven vehicles the day she was attacked. But even if she could not get justice, at a minimum she wants compensation.

Bipasha, 2002

Bipasha was visiting her in-laws in a different village for four or five days in September 2002. Her brother-in-law (husband’s brother) had joined the Maoists and the security forces often interrogated the in-laws about his whereabouts.

She recounted how the security forces came to her in-laws’ house many times. On one day in September 2002, they came early in the morning when the family was asleep: “They just barged in. We were frightened. They looked everywhere, and then they went away.”[74]

They returned at around 7 a.m. the same day when the family was awake, asked her parents-in-law questions about their Maoist son, and started questioning and threatening them. Bipasha recalled them saying: “‘Where is your son? You have to bring him here. Why did he join the Maoists? If you don’t bring him, we will kill you.’”

When her parents-in-law explained that their son had joined the Maoists against their wishes and they did not know where he was, security forces beat her family members and left. But they returned again at around 9 a.m. when Bipasha was alone with her baby and parents-in-law. They asked Bipasha to produce a photo of her brother-in-law. When she told them she did not live there and did not have a photo, they dragged her inside.

[T]hey took me inside and asked me to open the box where we store our clothes. Some of them dragged the box outside. The others started beating me inside. They were kicking me, hitting me, pulling my hair…. Then they pushed me down on the floor.

She described how they proceeded to rape her:

They were holding me down and yelling at me. There were many of them. They were raping me. At some point I must have lost consciousness.[75]

When she regained consciousness she found that the security forces were still there:

I was in great pain.... And then I soiled my clothes. One of the men said, ‘Let’s go. She might die.’ ….My mother-in-law was crying, saying, ‘Don’t do this. She has a small child.’ But the men shouted abuses at her.[76]

Bipasha said she was covered in bruises and cuts, had heavy vaginal bleeding, and was unable to walk. One of her brothers-in law took her to a doctor where she was given medicine. Her in-laws sent word to her husband who used to work in another part of the country. He came to fetch her after four or five days and took her back home and cared for her. Her husband, who also spoke to Human Rights Watch, said he took her to a hospital but they were too scared to report the rape.

More than 10 years after the incident, Bipasha felt she was yet to fully recover, underscoring the importance of psycho-social and other support for survivors of rape.[77] Both Bipasha and her husband told Human Rights Watch they want compensation and the perpetrators to be punished.

Manorama, 2002

Manorama said she was alone with her baby son and her nine-year-old sister-in-law, when the security forces arrived on a search operation in October 2002 in the village where she lived. Her baby was only 11 days old, so she was still at home recovering from childbirth while her husband and her other in-laws worked in the field.

She was bathing at a hand pump when seven or eight armed men in military uniform asked about her family. She explained that everyone had gone to the field. Some of the men went inside to check. Her sister-in-law saw them, was frightened, and fled. Manorama explained that the security forces were often rude and aggressive during search operations, and the local people were afraid of them. When the security forces did not find anyone else, they left to continue their search operations.

A little while later two members of the same group who had visited their house earlier returned. Manorama described what happened:

I had finished my bath but was still at the pump. They ordered me to go into the house. They said ‘Show us Maoist hiding inside the house.’ I said, ‘We don’t have any Maoists.’ They beat me on my legs with a stick. Then they dragged me into the house. They pulled my hair and threw me on the ground.[78]

After dragging her inside the house, “One of them stood guard at the door while the other did something that he should not have done,” she said alluding to the first rape. “Then the other one, he raped me as well,” she said.[79]

They threatened her: “‘Don’t tell anyone. Otherwise we will hit you again.’” Manorama was scared and did not want to stay home alone. She was also in pain she says, because she was still tender after the recent childbirth. She went to the fields with her baby and told her husband about the rape.

Manorama and her husband decided not to tell anyone. She decided to speak out only after the peace agreement. Since then the villagers have guessed that she might have been raped because she has attended various meetings conducted by Advocacy Forum and have started gossiping about her. Her husband is displeased, especially because she has spoken about what happened to her to no avail—no one has been punished and she has not received compensation.

Human Rights Watch spoke to Manorama’s husband who believed that the soldiers had come from the nearby barracks, and were accompanied by some police.[80]

Radha, 2002

Radha remembers that it was about 7 p.m. on a night in mid-December 2002 when security forces arrived on a search operation in her village. They were all in camouflage uniforms and were carrying weapons. She was outside her hut in the courtyard. As three men approached her, Radha started running toward her neighbors’ house to escape them. She says she was scared because she knew that security forces beat people during search operations. However, they caught up with her and ordered her inside her house. After Radha responded sharply to them that she hadn’t done anything wrong, the security personnel started pushing her around. She retaliated: “I said, ‘You have no authority to touch me.’” But two of them dragged her inside the house while one stood outside. She said:

Two men came inside. They pushed me down on the ground, and pointed a gun at me. I struggled but there were two of them… They held me down and both raped me. Then they went outside. They were laughing. I ran after them. I saw my husband outside and I shouted to him, ‘These men have raped me.’ [81]

Radha’s husband told Human Rights Watch that he hurried from the fields when he saw the security forces. He saw two men come out of his house, and then his wife came out too. She was crying and she told him that she had been raped.

He said that the security forces had come on a search operation, but one of their jeeps was bogged in mud, so they wanted a tractor to help them retrieve it. After his wife told him of the attack, he chased the men, who had climbed into the tractor. “I ran up to the tractor. The owner, who was driving the tractor knew me so he stopped,” he said. He said he tried to confront the attackers. But the security forces threatened him: “‘Get down, or we will kill you.’” The owner also asked him to leave saying he would be killed. “I was frightened for my life. They had guns,” the husband explained why he had to retreat.[82]

Both of them complained to the Village Development Committee, the administrative authorities, and the Local Peace Committee, set up to identify cases eligible for interim compensation after the conflict, but none of these authorities assisted them. They want justice and compensation.

Anita, 2002

During the conflict, Anita lived with her husband and parents-in-law. On the day of the incident in September 2002, the security forces came early in the morning. Anita was still in her room, while her husband had taken their cattle for grazing and her parents-in-law were in the market. One man entered her room while the others waited outside.

I was getting ready to get up.… I had to start the cooking. I heard noises and then there was a man in the room. He was in uniform. I tried to get up, but he stopped me. He was holding me down. He had a gun, which he then put next to the bed. He said ‘Don’t shout or I will shoot.’ He held me down forcefully and raped me. While he was raping me, there was a whistle from outside. There were other soldiers and they started leaving and saying, ‘Come on. Hurry up.’ So he hurried out.[83]

Human Rights Watch spoke to Anita’s husband who said that as he was returning from the field with the cattle he saw the security forces at his house on a search operation. They refused to let him enter his house, and beat him with the butts of their rifles. The security forces signaled the end of the search by sounding a whistle and he saw some of them exit his house. “When they blew the whistle four or five security force personnel came out of the house. Then they started calling out. Then this other man came out,” he said explaining how one more man followed the others, lagging behind. He believed that they were a joint team from the nearby army camp and local police.[84]

Both Anita and her husband believe that the whistle indicating the end of the search and summoning the security back possibly saved her from gang rape. Anita’s husband is angry, helpless, and scared for their lives, and he said that making a complaint about the rape was inconceivable because they were petrified of security forces at that time.

The husband told Human Rights Watch he felt his wife has not yet recovered physically and mentally from the trauma of rape. Anita had a daughter within a year of the rape. “Sometimes I wonder if she is because of the rape. But my husband loves her, and we believe she is our daughter.”[85]

Shona, 2002

Shona lived with her husband and two sons during the conflict. When the security forces intensified their operations against the Maoists, many of the men from the village ran away. Shona’s husband went to India.

At the beginning of her interview, Shona preferred to have her husband speak about what happened to her and Human Rights Watch spoke to him in Shona’s presence. According to information that her husband gathered from Shona and other villagers after he returned from India, the Maoists used to come often to their house and Shona used to give them food. He believes that a village informer saw a Maoist coming out of their house and alerted the security forces. In February 2002, police came to their home, accused Shona of being a Maoist, and took her into custody. They also took their 11-year-old son and detained him for four days, slapping and interrogating him about Maoist whereabouts.[86]

Shona remembered her detention and volunteered information about it.