Democracy in the Crossfire

Opposition Violence and Government Abuses in the 2014 Pre- and Post-Election Period in Bangladesh

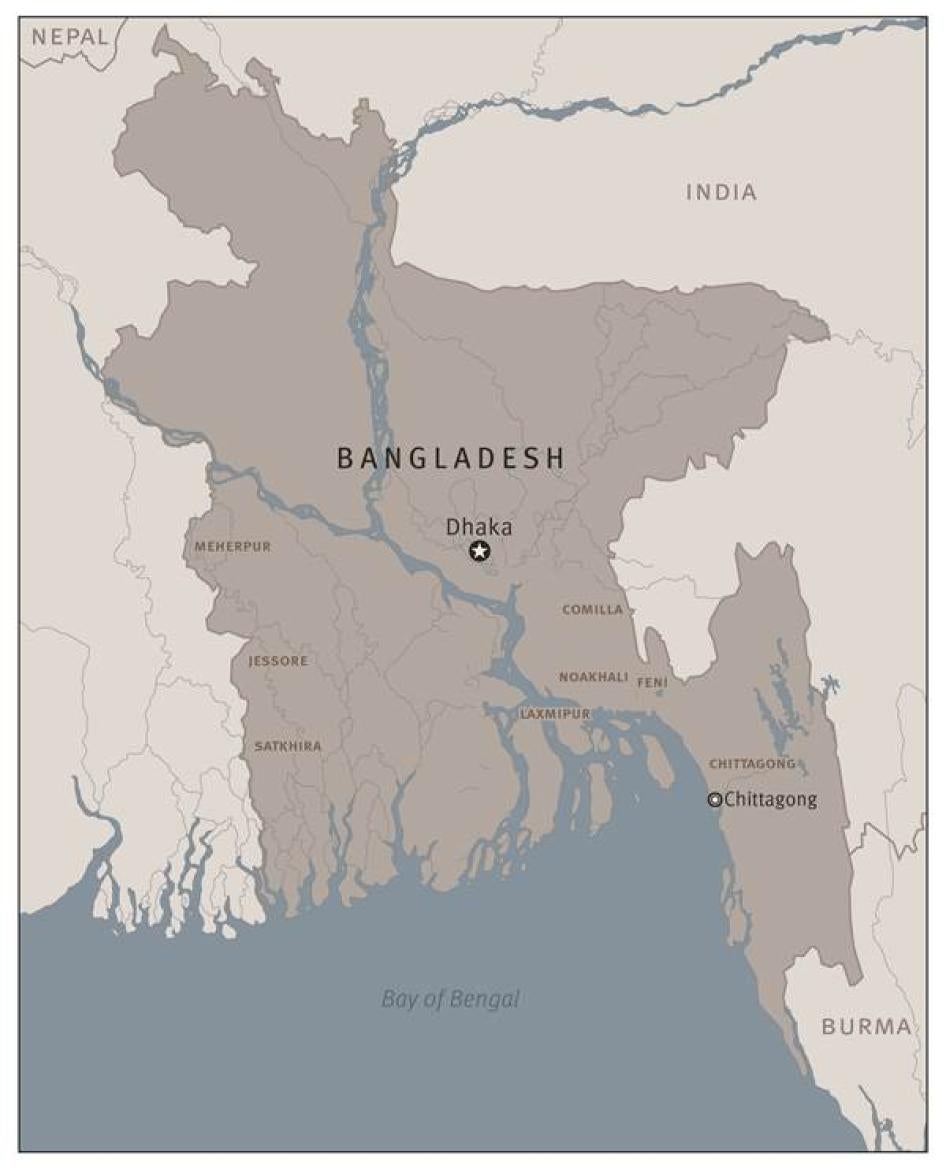

Map

Summary

Parliamentary elections in Bangladesh in January 2014 were the most violent in the country’s history. Months of political violence before and after the elections left hundreds dead and injured across the country.

The Awami League (AL) government and the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) sharply disagreed about the appropriate mechanism to hold free and fair elections in January 2014. As a result, the BNP and other opposition parties staged blockades and demonstrations beginning in October 2013. Their chief demand was the reinstatement of the neutral caretaker government system to oversee elections, which the Awami League had previously supported but then abolished after taking power. Tensions were further heightened after the December 13 execution of a senior leader of the Jamaat-e-Islami party for crimes committed during Bangladesh's independence war in 1971. Jamaat, which opposed independence and is the country's largest religious party, was disqualified from participating in the 2014 polls after the Supreme Court and the Election Commission ruled that its charter violated the constitution.

Calling for an election boycott, some opposition activists attacked and killed people who refused to honor blockades, as well as security forces and members of the Awami League. The minority Hindu community, long the target of attacks by Islamic extremists and others, was also singled out for attacks. During the vote itself on January 5, opposition activists targeted election officials and attacked schools and other buildings serving as polling places.

The government responded by deploying the notorious paramilitary unit, the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), as well as the Border Guards Bangladesh (BGB) and the police, often under the rubric of “joint forces.” Members of these units individually or in joint operations carried out extra-judicial executions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests, and the unlawful destruction of private property. These abuses continued long after election day. As a result of the opposition boycott, more than half of Bangladesh’s parliamentary seats were uncontested. On a low turnout, the Awami League won nearly 80 percent of the seats, leaving the country effectively without a parliamentary opposition. Voter turnout was a record low in Bangladesh’s history because of the boycott and related violence.

Opposition Attacks

In an effort to pressure the Awami League to allow a caretaker government during the elections, the opposition alliance, from the end of October 2013 onwards, organized strikes, demonstrations, and traffic blockades which frequently turned violent. On numerous occasions, opposition party members and activists threw petrol bombs at trucks, buses, and motorized rickshaws that defied the traffic blockades or were simply parked by the side of the road. In some cases, opposition groups recruited children to carry out the attacks. Such petrol bomb attacks killed more than 20 people and injured dozens, according to local human rights organizations. Some of the victims were children.

When Human Rights Watch visited the Dhaka hospital where burn patients were taken, it was so overcrowded that some were forced to sleep in the corridors. Most patients said they had not had any warning they were going to be attacked and had not seen who had thrown the bombs. Others identified their attackers as opposition supporters. Rubel Mia, a motorized rickshaw driver from Comilla, told Human Rights Watch he was burned from the waist down after accidentally driving into a road block.

I was driving down the road when all of sudden I came across a picket. There were lots of men. I had no idea they were there. I tried to escape but they chased me and they hit the vehicle with sticks and I crashed. They then poured petrol into the cab and lit it. I think they wanted to kill me.

Attackers in several locations also vandalized hundreds of homes and shops owned by members of Bangladesh’s Hindu community before and after the election, as well as those of some members of Bangladesh’s tiny Christian community. Victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch blamed BNP and Jamaat activists for some of the attacks. Hindus traditionally vote for the Awami League in elections.

Uday Roy, a Hindu from Dinajpur district, said opposition supporters attacked his village on the morning of January 5, after they had warned Hindus not to vote:

The attackers were our neighbors from the other side of the village. They are all BNP-Jamaat. They asked us not to vote. Between 9 and 11 a.m. they actually blocked the road so no one could go to the polling center. Then at 11 they began the attack. Some of them threw bricks at us. Others had sticks. There was lots of screaming, women and children were screaming. Plenty of houses were damaged. I was hit by a brick on my waist…. About 20 people were injured, including some women and children.

On election day and the days leading up to it, opposition activists attacked polling stations and officials. According to media reports citing the Bangladesh Election Commission, attackers killed three election officials and injured 330 other officials and law enforcement agents. Because of the violence, the commission suspended voting in 597 of 18,000 polling centers.

Killings and Other Abuses by Security Forces

In response, Bangladesh’s security forces launched a brutal crackdown on the opposition. In this report we document the killing or unlawful arrests of 19 opposition leaders and activists in the run-up to and aftermath of the elections. The number of cases we documented was limited by time, resources, and access. Journalists, local human rights organizations, and opposition groups have reported numerous other killings in circumstances that appear similar to the cases documented here.

Election-related killings and enforced disappearances follow past patterns. Bangladesh has a long history of extrajudicial executions, which have taken place under both BNP and AL governments and been allowed to happen with impunity. RAB, Bangladesh’s elite anticrime and anti-terrorism force created in 2004, has been implicated in hundreds of unlawful killings.

In nine of the killings documented in this report, authorities claimed that the victims were killed in “crossfire” during gunfights between the security forces and armed criminals. In all nine cases, there is strong reason to question the official account. In several of the alleged crossfire cases, witnesses said that the killed person had been detained hours or days earlier, contradicting government claims. In the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the detainee was the only person seriously injured or killed in what was claimed to have been a fierce gun battle. Security forces have little credibility when they claim that suspects die in crossfire, as they have regularly invoked the “killed in crossfire” explanation to justify what the evidence later showed to be cold-blooded executions of detainees or suspects.

For instance, local police authorities claim that security forces killed 15-year-old Abu Hanif, also known as Chhoton, when he and other members of the Jamaat youth wing attacked them in the Satkhira district on January 18, 2014. Several witnesses interviewed separately, however, said that security forces had detained Chhoton the previous day, accusing him of participating in protests and setting fire to several motorcycles in his village. Chhoton’s mother told Human Rights Watch:

The police grabbed my son in broad daylight like a vulture catches its prey. Then, one of our relatives informed us that Chhoton’s body had been found near the Bhomra border crossing with India. Why was my son killed? for what reason was he killed? Was there no jail to keep him? Was there no law to try my son if he was found guilty of committing a crime?

In two cases, security forces killed opposition leaders and activists during arrest operations, but where the circumstances indicate that the victims were executed. In 10 other cases, witnesses told Human Rights Watch that opposition party members and activists were arrested by people who either identified themselves as members of security forces or used vehicles marked with the letters RAB. On January 18, 2014, for instance, men in black uniforms using a vehicle with the letters RAB on it picked up Mosharraf Hossain, a local Shibir leader, from his sister’s house in Chittagong district. The following day, local residents discovered Hossain’s bullet-ridden body close to the Dhaka-Chittagong Highway. The authorities deny any involvement.

In addition to executions and enforced disappearances, security forces arrested thousands of opposition party members and activists across the country. The Bangladeshi authorities have the authority and duty to investigate, detain, and prosecute people who have committed offenses. But this must be done in accordance with international human rights standards and Bangladeshi law. Human Rights Watch research shows that security forces in a number of cases appear to have detained people solely because of their affiliation with an opposition party and without any evidence or reasonable suspicion that they had broken the law.

In a common pattern, security forces detained opposition party members and activists without warrant and charged them later in criminal cases in which they had not been originally named. Another striking pattern is that many of the opposition party members and activists were detained shortly after they announced strikes to protest the elections. Inciting violence is an offense, but calling for peaceful protests is not.

For example on January 7, 2014, police arrested eight BNP politicians, including BNP Vice-Chair Selima Rahman, who was detained after addressing a press conference announcing a new set of demonstrations. Khandaker Mahbub Hossain, a senior adviser to the BNP president, was also held shortly after giving a speech denouncing the election. They were later shown arrested for involvement in a grenade attack on the office of the police commissioner. Khandaker Mahbub Hossain told Human Rights Watch that the police did not question him about the attack:

Nothing was asked of me. In the interrogation cell they just asked me about a statement I had made when I said that the police were not acting as the servants of the Bangladeshi people, but of the government. No investigation was done. In every case they have two or three hundred ‘unknown’ people in the FIRs [First Information Reports]. My name was not in the FIR, they had no allegation against me.

Human Rights Watch investigated three sites where the evidence suggests that security forces unlawfully destroyed property by using a bulldozer, which completely or partially destroyed the houses of opposition leaders and activists who were wanted by the authorities, seemingly as punishment when the security forces were not able to locate and detain them. For example, on December 15, 2013, security forces destroyed parts of the house of Abdul Khaleq, the Jamaat leader for Satkhira district. According to the authorities, Khaleq was wanted in several criminal cases related to violence by opposition supporters. Neighbors told Human Rights Watch that security forces came to the area on December 15, 2013 with about 25 police vehicles and a bulldozer. An elderly neighbor told Human Rights Watch:

There was nobody home [at Khaleq’s house]. I was standing in the street. When the police arrived and started shooting in the air I became afraid and moved further away. The bulldozer was in front and started destroying the house. It took them perhaps 30 minutes. They also tried to set fire to the house, but neighbors managed to extinguish the fire after they left.

Impunity as a cause and consequence of abuses

Law enforcement agencies in Bangladesh have a dismal human rights record. Successive governments have an equally dismal record of failing to hold perpetrators to account. In particular, RAB has committed systematic human rights violations with impunity since its founding in 2004, as documented by Human Rights Watch and others.

The BNP created RAB and used it as a death squad during its last term in office. It now loudly calls for its members to be held accountable. While the Awami League called for RAB to be disbanded while in opposition and promised “zero tolerance” for extrajudicial killings after it came to power in 2009, its officials have at times even refused to acknowledge that security forces are responsible for human rights violations. Some have even appeared to encourage them. For instance, on March 9, 2014, Shipping Minister Shajahan Khan, in response to criticism of the frequent deaths in crossfire, responded, “Of course, every human being has the right to live. But, I think a bit of crossfire is needed to uproot terrorism from the country.” Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina praised law enforcement agencies for their actions against those responsible for violence during strikes and blockades, saying that “members of the police force along with people are discharging their duties sincerely in keeping law and order.” She said nothing about reports of extrajudicial killings, ensuring law enforcement officers act within the law, or holding abusers accountable.

The long-standing impunity enjoyed by Bangladesh’s law enforcement agencies fuels rampant violations. Despite hundreds of reported cases in recent years, no member of RAB has been convicted and imprisoned for an unlawful killing.

The government and all political parties in Bangladesh should make clear and unambiguous public statements, at the highest political levels, opposing politically motivated violence for any reason, while emphasizing that both domestic and international law prohibit such attacks. Bangladesh authorities should prosecute to the fullest extent of the law members of law enforcement agencies, of whatever rank, found responsible for unlawful killings, torture, and other human rights abuses, including those who ordered such attacks. It should also act against commanding officers and others in a position of authority who knew of these abuses but failed to take reasonable steps to prevent them.

RAB should be disbanded and replaced with a fully accountable civilian law enforcement agency dedicated to fighting crime and terrorism. In the meantime, because of a lack of political will to end abuses and prosecute perpetrators, all assistance to RAB should end. In recent years the United States has worked with RAB to create a functional internal affairs unit, but this and other training has failed over many years to prevent abuses or create a culture of legal accountability.

Members of the international community have repeatedly urged the Bangladesh political leadership to initiate dialogue to end the political deadlock. In a statement on January 6, 2014, UN Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon, whose representative was unable to mediate a settlement, said he regretted that the parties had not reached an agreement before the elections and called on all sides to ensure a peaceful environment, “where people can maintain their right to assembly and expression.” After the disputed January 5, 2014 elections, many governments, including the United States, Canada, Germany, and others, called for credible elections to resolve the ongoing crisis. While elections are a basic right, no right is more important than the right to life. The UN and governments should use the full weight of the international community to press the authorities to end extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and arbitrary arrests, prosecute those responsible, and allow peaceful protest and full rights to freedom of expression, association, assembly, and movement.

Key Recommendations

Bangladesh’s political parties, particularly Jammat-e-Islami, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, and the Awami League, should make clear and strong public statements, at the highest levels of each party, denouncing all forms of politically motivated violence, and should dismiss party members found to be involved in planning or carrying out violence. They should also support and fully cooperate with any criminal investigation into crimes of violence.

The Bangladeshi Government Should:

Make clear and strong public statements, at the highest political and institutional levels, condemning unlawful killings, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances and other violations by law enforcement agencies.

Commit to ending impunity and ensure that all those responsible for abuses are investigated and prosecuted in an independent, transparent, and credible manner.

Ensure that all arrests are made in strict compliance with Bangladesh’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), including that arrests be made only with necessary court-ordered warrants, that detainees be held only in recognized places of detention with prompt access to lawyers and family, and timely production before relevant court.

Ensure the safety of detainees in government custody, including by prohibiting law enforcement agencies from taking detainees on nighttime operations where they are often executed in “cross-fire killings.”

Require each law enforcement agency to regularly provide parliament and the National Human Rights Commission with detailed information about numbers of arrests, numbers and types of police abuse or misconduct complaints received, status of the complaints investigated, numbers of officers disciplined and for what offenses, and the number of cases referred for prosecution and their status. Require that such information be made public.

Establish an independent, external accountability entity to conduct prompt, impartial, and independent investigations into all allegations of violations by law enforcement agencies including the police, Rapid Action Battalion, and Border Guards Bangladesh. Empower this mechanism to investigate and prosecute commanding officers and others in a position of authority who knew of abuses and failed to take action to prevent or punish abuses. The report of the mechanism should be made public. This entity should be charged with receiving complaints from the public.

Methodology

This report is based on field investigations conducted in Bangladesh from December 2013- February 2014. Human Rights Watch researchers visited the cities of Dhaka and Chittagong as well as the districts of Comilla, Feni, Jessore, Laxmipur, Meherpur, Noakhali, Satkhira, and Chittagong where they interviewed more than 120 victims, witnesses, and lawyers.

Interviews were conducted in person or by phone. Most interviews were conducted through Bangla-English interpretation. Some interviews were conducted in Bangla by a Bangla-speaking researcher. In some cases, we have withheld the names of those we interviewed, using instead pseudonyms to identify the sources of information to reduce the possibility of reprisals.

Before each interview we informed interviewees of its purpose and asked whether they wanted to participate. We informed them that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific questions without consequence. No incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed.

In some cases Human Rights Watch researchers visited the sites where the killings, detentions, or destruction of property had taken place to corroborate witness evidence.

The Bangladeshi authorities did not respond to a letter we submitted on March 28, requesting information about the specific cases documented in this report. For information on the authorities’ versions of the cases, we therefore have relied on news accounts giving details of their responses, where such accounts are available.

I. Background: 2014 General Elections

Two parties dominate political life in Bangladesh: the Awami League (AL), currently in power and headed by prime minister Sheikh Hasina, and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), led by former prime minister Khaleda Zia. The rivalry between the two main parties is longstanding, bitter, personal, and often turns violent. Each party also has active student wings (Jatiyatabadi Chhatra Dal for BNP and Bangladesh Chhatra League for AL), whose members are often implicated in violent attacks and clashes.

A third party, Jamaat-e-Islami, is the largest Islamist political party and an ally of the BNP. In 2013 the High Court of Bangladesh cancelled its registration for the 2014 general elections, ruling that provisions in the party’s charter were incompatible with Bangladesh’s constitution.[1] Its student wing, the Bangladesh Islami Chhatra Shibir, has been implicated in significant amounts of violence over many years.[2]

To guard against fraud and manipulation, a caretaker government oversaw general elections starting in 1996. The system was initially demanded by the Awami League while in opposition as it feared the BNP government would manipulate the electoral process. The caretaker system has been widely credited with limiting fraud and irregularities for the elections over which it presided. In 2011, however, the Awami League-dominated parliament abolished the system, in order, it said, to prevent a de facto coup as occurred in 2007 when a caretaker government was put in place by the military and remained in power for two years.[3] Opposition parties, however, insisted that fair and free elections would only be possible under an independent caretaker government.

In October 2013, BNP leader Khaleda Zia called for strikes in support of her demand that elections be held under a caretaker government. Several strikes, including an economic blockade, followed.[4] The Awami League government rejected the opposition’s demands, offering an all-party government instead with Hasina as prime minister. The opposition alliance rejected this and boycotted the elections.[5] The December 2, 2013 boycott announcement was followed by a sharp increase in political violence across the country.[6]

The 2014 election also took place against a backdrop of violence related to the prosecution and sentencing of Jamaat leaders accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity during Bangladesh’s struggle for independence in 1971. Opposition supporters resorted to violence following the death sentence of Jamaat leader Hossain Sayedee on February 28, 2013. Awami League leaders claim that opposition supporters killed at least 17 of their activists in the Satkhira district alone, which is a Jamaat stronghold, in 2013.[7] Tensions and violence increased further in the days just before and after the execution of another Jamaat leader, Abdul Quader Mollah, on December 13, 2013.[8]

Legal Framework

Bangladesh is a state party to several of the central international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Bangladesh is thus, among other things, obliged to ensure that no one is arbitrarily deprived of her or his life, that no one is subjected to torture, and that in the determination of a criminal charge, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing by a tribunal established by law, and to be presumed innocent until proven guilty.[9] The ICCPR also provides the right to liberty and security, and guarantees against arbitrary arrests and detention. Under international human rights law, Bangladesh is also obliged to thoroughly and promptly investigate serious violations of human rights such as the right to life or freedom from torture, prosecute those implicated by the evidence and, if their guilt is established following a fair trial, impose proportionate penalties.[10] Implied in this is that all victims shall have the opportunity to assert their rights and receive a fair and effective remedy, that those responsible shall stand trial, and that the victims themselves can obtain reparations.

United Nations principles on the prevention and investigation of extrajudicial executions provide detailed guidelines for governments. They include the need for “thorough, prompt and impartial investigations” of all suspected unlawful killings to determine the cause of death and the person responsible. Independent and impartial physicians should perform autopsies in cases of possible unlawful killings, and bodies should be kept until an adequate autopsy is carried out and the family informed of the findings. Where the established investigative procedures are inadequate because of impartiality or lack of expertise, investigations of possible unlawful killings should be pursued through an independent commission of inquiry.[11]

The UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions has repeatedly requested permission for a country visit to Bangladesh, but has yet to receive a positive response.[12]

II. Election-Related Violence by the Opposition

The run-up to Bangladesh’s general elections on January 5, 2014, and election-day itself, were marred by extensive violence, much of it initiated by members of the opposition.[13] On October 25, BNP leader Khaleda Zia announced a series of general strikes (known in Bangladesh as hartals), protests, and traffic blockades (known as abarudh), halting transport links to the capital, Dhaka. The strikes and traffic blockades had a significant impact on the economy. The opposition was successful in preventing almost all travel outside the major cities during this period, harming many people's incomes and the national economy. Schools remained closed. Farmers were forced to dump milk and other fresh produce as they could not transport it to the cities. The estimated cost to the economy runs into the billions.[14]

In many incidents, opposition party workers attacked those not heeding the calls with petrol bombs and homemade grenades, and set off improvised grenades in busy streets without warning.[15] As detailed below, in some cases members of opposition groups recruited street children to carry out the attacks. On election-day, opposition groups attacked hundreds of polling stations.

Opposition leaders denied the involvement of their parties in the violence. Khaleda Zia blamed “government agents,” and said that “manipulation, terrorism, sabotage and disinformation have been used as tools to destroy people’s rights in an effort to prolong the control of the state.”[16]

Many Bangladeshis lost their lives or suffered horrific burns. At least 25 people had died of burns and 97 had been admitted to hospital by the end of December, according to media reports compiled by the human rights organization Ain O Salish Kendra.[17] A report by Odikhar, another human rights organization, put the number at 21 dead and 65 injured between November 25, 2013, and January 10, 2014.[18]

A Human Rights Watch researcher interviewed 25 patients or their relatives in December in the burn unit at Dhaka Medical College Hospital where many of the injured were brought. When Human Rights Watch visited the hospital it was so overcrowded that some of the injured were forced to sleep in the corridors. Most patients said they had not had any warning they were going to be attacked and had not seen who had thrown the bombs. Others identified their attackers as opposition supporters.

For example, one man told us that opposition supporters attacked his family as the truck they were riding in passed through Gazipur, north of Dhaka, on the evening of December 10, 2013. The opposition supporters, who had put timbers and bricks on the road, threw bricks at the vehicle. Adam Ali, a factory security guard, said he pleaded with them not to throw any petrol bombs. He told Human Rights Watch:

I said, ‘Please show us some mercy, my family is inside, please don’t throw the bombs.’ There were about 15 of them, aged 20 to 25. They saw my children were inside the cab. They shouted swear words at us then threw petrol bombs inside. I jumped out of one door with two of my children and told my wife, Sumi, to get out of the other. But she was trapped inside along with my 2-year-old, Sanjida. The door was locked and they could not get out. They died in the van. After that I was lying semi-conscious on the ground when some of those men came up to me. ‘Whatever happened, happened, you have to get over it,’ they told me.[19]

One of the worst single incidents took place in Dhaka on November 28, 2013. In response to the November 25, 2013 announcement of the date of the 2014 election, the 18-party opposition alliance announced a 48-hour rail-roadway-waterway blockade. The blockade was later extended.[20] A wave of violence ensued across Bangladesh.[21] At around 6:30 p.m. that day, attackers threw a petrol bomb at a bus, killing four passengers and injuring 15. The driver, Hassan Mahbub, who suffered burns on 30 percent of his body, said the bus was struck as it was travelling at over 70 kilometers per hour. He told Human Rights Watch:

All of a sudden two men threw a bottle. They were aged 20-30. They threw it through the windscreen. The whole bus caught fire. I was hit first. The bottle hit me. I jumped from the bus which then hit a traffic island. The flames burnt my face and arms. I thought I was dying. It was a blockade but the government ordered the bus owners to keep running their buses.[22]

In another case, Rubel Mia, a motorized rickshaw driver from Comilla, told Human Rights Watch he was burned from the waist down after driving into a road block.

I was driving down the road when all of a sudden I came across a picket. There were lots of men. I had no idea they were there. I tried to escape but they chased me and they hit the vehicle with sticks and I crashed. They then poured petrol into the cab and lit it. I think they wanted to kill me. No one came to help me.[23]

Children

Human Rights Watch research shows that several children were injured or killed in attacks and some were recruited or forced by opposition supporters to carry out violent attacks.

One of the injured was Syamol Sardar, a 13-year-old working as a passenger minibus conductor in Dhaka when the bus was attacked on November 10, 2013. His father, Aminullah, told Human Rights Watch that two men allowed the passengers and driver to escape the vehicle before pouring petrol into it. They did not, however, let his son leave. He said:

All the passengers got out apart from two. They told the driver what they were going to do but not Syamol. Before he could escape they poured petrol onto the vehicle and set fire to it. He pleaded with them, asked them to wait until he had escaped, but they did not listen to him.[24]

Mehedi Hassan, 7, was injured when a grenade exploded in front of him in Dhaka in December 2013, his mother Nasima Begum told Human Rights Watch.

Whoever did this to my baby, I want justice. I appeal to this government for them to be put on trial. He was on his way home from school when someone on a rickshaw threw a bag in front of him. It exploded. He lifted up his arms to protect himself. He was injured in both hands and legs and abdomen. Three fingers on his left hand were blown off.[25]

Shumi Khatun, 8, suffered burns when the bus she was travelling in was set on fire on November 3, 2013 in Gazipur. Her mother Rubena told Human Rights Watch:

She was coming to Dhaka with her grandmother in a bus when it reached Gazipur. She saw the bus was set on fire and they tried to escape but there were so many people she fell down. When her grandmother came out she couldn't see Shumi so she went back inside the burning bus to rescue her. She found her crying under a seat. Nobody warned them that they were going to set it on fire.[26]

Other children were injured picking up unexploded, homemade grenades left in the street. (Although Human Rights Watch has not been able to establish who produced the grenades, news articles have reported their use by opposition supporters).[27] Lima Akhter, 3, had her right hand blown off in Mirpur, Dhaka, on December 3, 2013. Her mother, Sohagi told Human Rights Watch that she had thought it was a ball:

She was in the road in front of our home and saw an object that looked like a ball. It was wrapped in red tape and she picked it up and it exploded. There was no hartal picket there. We have no idea how it got there. Her right hand was blown off above the wrist.[28]

Human Rights Watch interviews, research conducted by others, and media reports indicate that opposition supporters used children to conduct some of the attacks. A 15-year-old boy living on the streets close to one of Dhaka's main bus terminals told Human Rights Watch that opposition supporters often asked street children like him to throw grenades and set fire to buses. He said he had twice been involved in the violence:

The first time two strangers gave me a box of cocktails [grenades] and said they would kill me if I did not throw them. The second time, a leader of the Jubo Dal [the BNP youth wing] gave me and three friends 2000 taka to set fire to two buses using petrol bombs. That night we did this, but we made sure people got out first.[29]

Abu Ahasan, a researcher at BRAC, a Bangladesh development organization, told Human Rights Watch that his research for an upcoming report, “Street Children and the Politics of Violence,” confirmed the allegation that opposition groups had used children to carry out attacks. Ahasan told Human Rights Watch that he spoke to more than 70 children in Dhaka and found that some glue-addicted children were persuaded to throw bombs in exchange for glue. Others were lured by money to participate in violence, while some were forced to do so.[30]

Media reports suggest that homeless children and child laborers were involved in similar activity in Chittagong city. A reporter with The Dhaka Tribune said he spoke to a six-year-old who said he was paid 100 taka a day for throwing grenades.[31]

Attacks on Polling Stations and Officials

On election-day and the days leading up to it, opposition activists attacked polling stations and officials. According to media reports citing the Bangladesh Election Commission, attackers killed three election officials and injured 330 other officials and law enforcement agents on election-day.[32]

In one case reported in the media, 100-150 BNP-Jamaat supporters attacked Molani Cheprikura Government Primary School, a polling station in Thakurgaon, on the evening of January 4. The attackers killed assistant presiding officer Zobaidul Haque, 55, and severely injured three others.[33]

Mohamed Saiful Islam, a girls’ college teacher who was in charge of a polling station in Gaibandha district, told Human Rights Watch that a large group of opposition members attacked his vehicle:

After polling ended 20-25 men attacked the vehicle that was carrying me, the ballot boxes, and a policeman, throwing bricks. Then they threw a fire bomb. I was badly burnt and the boxes were destroyed.[34]

Attackers also torched dozens of schools intended to be used as polling stations in the days preceding election-day.[35] Government ministers said that in total 553 schools and educational institutions were damaged during election-related violence and that the government had allocated more than $US1.7 million for repairs.[36]

Because of the violence, the Bangladesh Election Commission said it suspended voting in 597 of 18,000 polling centers.[37]

Attacks on Minority Communities

Attackers vandalized hundreds of homes and shops owned by members of Bangladesh's Hindu community before and after the elections. Members of Bangladesh's tiny Christian community were also attacked.[38] Most Hindus traditionally vote for the Awami League in elections and have been targeted by supporters of the opposition parties in previous years.[39] Community leaders, NGO staff, and journalists speculated that some attacks might have been primarily motivated by land and property disputes, but were facilitated by the outbreak of political violence.[40]

In many cases, victims and witnesses were not able to identify the perpetrators. In some of the cases Human Rights Watch investigated, however, victims told us that BNP and Jamaat supporters were responsible for the attacks, claiming that the perpetrators were neighbors or other individuals already known to them as opposition supporters.

Both the BNP and Jamaat denied their supporters were involved and blamed Awami League members. Jamaat has called for a UN-supervised inquiry commission.[41]

Uday Roy of Kornai village in Dinajpur district said opposition supporters attacked his village on the morning of January 5, after they had warned Hindus not to vote:

The attackers were our neighbors from the other side of the village. They are all BNP and Jamaat. They asked us not to vote. Between 9 and 11 a.m. they actually blocked the road so no one could go to the polling center. Then at 11 they began the attack. Some of them threw bricks at us. Others had sticks.

There was lots of screaming, women and children were screaming. Plenty of houses were damaged. I was hit by a brick on my waist. We called a local Awami League leader who promised to send help but none came. We called the polling station to send police but they said they could not come. About 20 people were injured including some women and children. Every time there is a national vote we face the same problem.[42]

According to media reporters, the attackers looted and torched at least 100 shops and houses.[43]

Paritush Chandra Sen, of Patgram Upazilla in Lalmonirhat, told Human Rights Watch that an attack on the village temple sparked a wider clash between government supporters and opposition members the day before the polls. He said:

BNP activists tried to burn down our temple. The Awami League then came out to stop them and there was a clash and two people died. One was killed on the spot, the other died in hospital. They were both ex-Jamaat men who then joined the BNP. The situation was then put under control and all of us voted. The police gave us protection. Still, there is a lot of fear in the area. It is very remote and close to the Indian border. All the Hindus are staying at home and are worried about the situation.[44]

Gopal Bomon, a community leader, said an attack on shops in Lalmonirhat on November 27, 2013 was connected to a land dispute, but probably was facilitated by the outbreak of political violence:

In the market there are 40 or 50 shops, about half of which are owned by Hindus. That night 14 were vandalized. Two Hindu shops were spared because they are in the mosque compound. Another was spared because the building’s owner is a Muslim. The problem is that there is a land dispute between the Hindus and a local BNP leader. He lost a court case against them, so we suspect that he was taking advantage of the hartal to target the Hindu community.[45]

One of the most serious incidents took place on election-day in Malopara village in Jessore district. Dozens of people attacked the Hindu fishing village, forcing inhabitants to cross a river to escape. Human Rights Watch interviewed three villagers who witnessed the attack and the leader of a neighboring community who helped them to cross the river. All of them blamed members of the BNP and Jamaat for the attack. But the winning Awami League MP blamed his challenger, also an Awami League member, for orchestrating the violence, which the latter denies.[46]

Shibu Sarker, a fisherman, told Human Rights Watch that the attack began after voting had finished. Many villagers had cast their vote despite being warned by opposition supporters not to vote:

At about 5 p.m., about 150 BNP and Jamaat men came to our village and argued with the people. Some Hindus tried to negotiate with them. But then one of the Jamaat guys, called Arif, made a phone call and told the person on the other end of the line that the Hindus were slaughtering the Jamaat. So then about 300 BNP and Jamaat came and they were carrying local weapons, like big knives and hand bombs and bricks, and they moved towards the village. We started to flee and crossed the river. We found a boat and escaped. No one was injured. The BNP men started throwing bricks. Then they ran amok in our homes.[47]

According to Sarker the police finally arrived at 8 p.m. and villagers started to return at about 1 a.m. The attackers vandalized at least 43 houses, according to Odikhar.[48]

III. Crossfire Killings by Government Security Forces

Before, during, and after the elections, Bangladesh’s security forces launched a brutal crackdown on the opposition, unlawfully killing dozens of leaders and activists, carrying out widespread arbitrary arrests, and in some cases unlawfully destroying property belonging to opposition leaders and activists. Security forces responsible for violations continue to enjoy impunity in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh has a long history of egregious abuses by security forces. Widespread violations have taken place under both the Awami League and BNP, as well as under the military-backed interim government.

RAB has been implicated in hundreds of unlawful killings, including “crossfire” killings that evidence suggests were extra-judicial executions.[49] Cases involving security forces we investigated for this report indicate that perpetrators now often belong to other law enforcement agencies as well. In several cases, witnesses told us that the perpetrators were “joint forces,” a mix of RAB, BGB, and police. In media interviews about the killings, authorities also often referred to “joint forces” being involved. A police report about one “crossfire” killing obtained by Human Rights Watch corroborates this point: it lists members of the RAB, BGB, and police as having taken part in the operation.[50]

Many of the victims in the cases documented in this report were leaders and activists belonging to BNP, Jamaat, or their student wings. They were all male, ranging in age from 15 to 62. In some cases the authorities appeared to target the victims because of suspected involvement in specific crimes. In other cases, however, security forces appeared to seek out influential opposition district and sub-district-level leaders who might have been able to mobilize people to protest against the government and the holding of the elections.

The violations documented by Human Rights Watch took place across Bangladesh. Human Rights Watch documented extrajudicial executions and arrests in the districts of Satkhira, Meherpur, Laximpur, Noakhali, Nilphamari, and Sitakunda.

“Crossfire” Killings and Apparent Executions

In the limited time we had to prepare this report, Human Rights Watch documented the killing of 11 opposition leaders and activists by security forces before, during, and after the January 5, 2014 elections. Journalists, local human rights organizations, and opposition groups have reported numerous other killings in circumstances that appear similar to the cases documented by Human Rights Watch. Most of the killings took place in January, after the elections.

In six cases the authorities admitted that security forces had initially detained the victims and that the victims had been shot dead while in custody. In all six cases, however, the security forces made the implausible claim that the victims had been killed in crossfire when criminals attacked the security forces a day or so after the victim had been detained.

In three other cases the authorities claimed that the victims had died during gunfights between criminals and the security forces. The authorities denied that the victims had ever been in the authorities’ custody, but several witnesses told Human Rights Watch independently that security forces had detained the victims in these cases at least several hours before they were allegedly killed in gunfights.

In two cases security forces killed the victims during operations. In both cases, statements from witnesses and the circumstances of the killings indicate that the security forces executed the victims.

The Killing of Golam Sarwar, Feni District

On January 30, 2014, Golam Sarwar, a leader of the BNP’s youth wing, was killed in Fazilpur village, Feni district, during what the authorities claimed was an attack on the security forces who had just detained him. Four witnesses, however, told Human Rights Watch that Sarwar was killed in a house close to his home and that there had been no attack on the security forces.

Sarwar, 28, was the senior vice-president of the local unit of the BNP's youth wing, Jubo Dal. According to a news report about his killing, Major Muhiuddin, the officer-in-charge of RAB-7 in Feni district, said that his RAB team had arrested Sarwar, who was wanted in connection with several criminal cases, around 6 p.m. on January 30, 2014. According to the news report, Muhiuddin said that Sarwar’s associates attacked the RAB team on the way back to the headquarters and that Sarwar was caught in the line of fire and died on the spot.[51] News reports about the incident reviewed by Human Rights Watch do not report anyone else killed or injured during the gunfight.

Four witnesses told Human Rights Watch that Sarwar died inside a house and that, although they could not see how Sarwar died, they were certain there was no gunfight.[52]

A relative of Sarwar told Human Rights Watch that Sarwar was having lunch at about 3 p.m. on January 30 when she saw three motorized rickshaws approach outside. When about 18 men got out of the rickshaws, Sarwar ran out the back door. The men, who were not in uniform, chased after him, shouting, “stop, thief, thief,” she said. According to the relative, one of the men fired a pistol at Sarwar's legs, but he kept running for about another 500 meters and hid inside somebody else's house.

Three people living in the same compound who witnessed the incident gave similar accounts. One of them said:

I heard a couple of gunshots then all of a sudden I saw him run into the compound. He went and hid behind the door. Then I saw the men running after him. They threatened me and said I was hiding a fugitive. They said they would shoot me.[53]

The second neighbor said:

I had just come back from school when I saw the incident. The men were searching everywhere for him. One put a pistol to my head and said, ‘Where the hell is he?’ I said I had no idea and the man then hit me.[54]

According to the three witnesses, several of the men entered the house where Sarwar had sought refuge, while others stayed on guard outside and told villagers not to come near. Neither of the witnesses knew whether the men were civilian or members of a law-enforcement agency.

After a while, several uniformed policemen arrived, and after about 30 minutes they were joined by some RAB men, the witnesses said. They then heard further gunshots. One of Sarwar’s relatives said: “The police were there for half an hour before they brought his body out. Before that we heard two gunshots.”[55]

Later they saw four men carry Sarwar's body out of the building, wrapped in bed sheets taken from the house where he was killed, and place it in a black minibus that was driven by RAB. A witness said there was a large blood stain in the room where Sarwar died.

The witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they believed that the men in civilian clothes and the police had beaten and stabbed Sarwar before they killed him. A relative showed Human Rights Watch a photograph of Sarwar's corpse with two bullet wounds to the chest, and bruises and cuts to his right arm. A journalist who later examined the body in the morgue said that there were bruises and cuts on Sarwar’s shoulders, left arm, neck, and back.[56]

The Killing of Touhidul Islam Touhid, Noakhali District

On January 30, 2014, Touhidul Islam Touhid, a detained local BNP leader in Noakhali district, was killed in what the police claimed was a gunfight during a nighttime operation to recover weapons from his home.[57]

Mahbub Uddin, also known as Khokon, Touhid’s lawyer and a BNP politician, told Human Rights Watch that because the police in Sonaimuri sub-district had accused him of involvement in pre-election violence, Touhid had come to Dhaka on January 28 to apply for “anticipatory bail,” a provision in Bangladeshi law that allows a suspect to apply for bail before he is arrested. Because of the court backlog, however, Touhid’s case was postponed to the following day.[58]

Shortly after Touhid and his lawyer separated around 5 p.m., three men in civilian clothes apprehended Touhid outside the National Press Club, according to information collected by the lawyer. Shortly thereafter RAB forces arrived and took Touhid away.

Khokon said that he immediately went to the RAB office where he spent 1.5 hours, but they denied having detained Touhid. Later that evening, however, a police contact informed Khokon that Touhid had been transferred to the police. At around 1:30 a.m. Khokon met with Touhid in the police station where Touhid confirmed that he had been held in the RAB-3 office.

According to Bangladeshi law, the police are obliged to present a detainee to a court to apply for police remand within 24 hours. The next morning, however, Khokon found that Touhid was being driven to the police station in Noakhali, his home-district. Khokon told Human Rights Watch:

I immediately called several senior local politicians in Noakhali, telling them to warn the police not to kill him. I even went on a talk-show that evening and warned the police myself. But it didn’t help.

In the early hours of January 30, Touhid’s body was dropped in front of the hospital in Noakhali. According to a lawyer who saw the corpse, it had three gunshot wounds in the legs and a doctor told him that Touhid had most likely bled to death.[59]

According to media reports, the police claimed that they had taken Touhid along to search his house around 3:30 a.m. on January 30, during which they had recovered a weapon and some ammunition. There was no explanation why such an operation would be carried out in the middle of the night. On the way back to the police station, the police claimed, Touhid’s associates opened fire on them, killing Touhid and injuring two police officers.[60]

But this account is contradicted by Touhid's brother Kamal, who said he was in the house at the time. He said that his family was awakened by police trying to enter the property, who left after a brief conversation. Touhid was not present at that time. No guns were seized, he said. As Kamal described it:

There was shouting and banging at our gate. They broke it open and entered our yard. I came out onto the veranda to ask them what they wanted. There were 5 policemen. Touhid was not there. One said they wanted to talk about something with me. I said I have no idea what you mean and was scared of them so went inside. Then we heard 3 or 4 shots. We were all afraid but opened the door to have a look and saw the police running away.[61]

The Killing of Azharul Islam, Satkhira District

On January 27, Azharul Islam, a detained local leader of the BNP’s student wing, was killed in Satkhira district in what the authorities claimed was a gunfight during a nighttime operation to arrest his accomplices and recover weapons and ammunition.

Islam, 27, was the vice-president of the Jatiyatabadi Chhatra Dal, the student wing of the BNP, in the Tala sub-district of Satkhira district.[62] According to statements by the Tala police officer-in-charge, the authorities had wanted Islam for suspected involvement in the 2002 murder of an Awami League activist and for pre-election violence.[63] According to a news report citing the officer-in-charge, the authorities arrested Islam and two others at Chandpur in the early hours on January 26, 2014.[64]

A police report about the death of Islam obtained by Human Rights Watch alleges that, while in detention, Islam told police the location of his accomplices and some weapons. Acting on that lead, the report says, 17 police officers took Islam with them to arrest his accomplices and recover weapons the following night. According to the report, Islam’s accomplices opened fire on the police officers during the operation, injuring three officers, including the one who filed the report. The two other injured officers subsequently returned fire, according to the report, firing five shots each during the 20-25 minute gunfight. At some point, according to the report, Islam tried to escape and was shot by the “unknown criminals.” According to the police report, the police recovered one pipe-gun, two cartridges, and five hand-bombs at the scene of the incident.[65]

Medical personnel at the Satkhira Sadar Hospital declared Islam dead upon arrival around 6 a.m. on January 27, 2014, according to the report and news articles. The report does not specify what injuries the police sustained, but the officer-in-charge at Tala police station described them as minor in an interview later that day.[66]

The Killing of Abul Kalam and Maruf Hossain, Satkhira District

On January 26, 2014, two detained activists from Shibir, the Jamaat youth wing, were killed in what the authorities claimed was a gunfight during a nighttime operation to recover weapons and ammunitions in the Satkhira district. No other people involved in the alleged gunfight were killed or sustained serious injuries.

Around 4:30 a.m. on January 25, offices from RAB-6 and BGB detained Abul Kalam and Maruf Hossain in the village of Kulia in the Debhata sub-district of Satkhira district, according to news reports and a police report about the deaths obtained by Human Rights Watch.[67] Kalam, 22, was the Shibir secretary in the Debhata sub-district, while Maruf Hossain, 24, was a Shibir activist and son of the Jamaat leader in Kulia.[68]

According to the police report, Kalam and Hossain told the authorities the location of a weapons cache during interrogation. A joint group of RAB-6 and BGB officers went to recover the weapons in the early morning of January 26, taking Kalam and Hossain with them. About 100 meters from the house containing the alleged weapons cache, masked “unknown criminals” attacked the group, according to the report, trying to free the detainees. During a 15-20 minute gunfight, four officers fired 13 shots, according to the report. The two detainees and three officers were injured. Medical personnel at the Satkhira Sadar Hospital later declared the detainees dead.[69]

According to the report, the three injured officers were released “after primary treatment,” indicating that they were only lightly injured. The report does not mention whether any of the attackers were injured during the gunfight.[70]

The Killing of Tarique Mohammad Saiful Islam, Meherpur District

On January 20, 2014, a local Jamaat leader was killed in Meherpur district during a nighttime operation one day after he was detained. Authorities claim he was killed during a gunfight with his associates.

Tarique Mohammad Saiful Islam, 36, was the assistant secretary general of Jamaat in Meherpur district. According to his wife, the authorities had filed several criminal cases against him for participating in strikes and blockades, preventing the police from carrying out their responsibilities, and possession of weapons. Around 2:30 p.m. on January 19 security forces detained Tarique from the Islam bank in Meherpur. After his detention, Tarique’s wife and sister went to the police superintendent, but he refused to see them.

Around 2 a.m. the following morning a relative of Tarique called his wife and told her that he had heard gunshots near his house and that he had heard from one police officer that Tarique had been killed. The relative lives about 1.5 kilometers outside the center of Meherpur. The relatives later learned that Tarique had been killed near a construction site.

His relatives told Human Rights Watch that a nearby night guard had told them that he saw the security forces executing Tarique and that there had been no gunfight. Human Rights Watch was not able to speak to the night guard to verify this account.

Tarique’s wife told Human Rights Watch:

We couldn’t do anything after the call. Security forces had cordoned off the entire area and they were patrolling the streets in case of any demonstrations in reaction to the killing. We could do nothing but cry.[71]

Tarique’s wife told Human Rights Watch that she went to the hospital early in the morning, but that she was not allowed to see his body until the afternoon. A hospital employee with access to the morgue told Human Rights Watch that he saw Tarique’s body there around 5:30 a.m. According to him, the body was lying face down on the floor and his hands were tied behind his back with a rope.[72]

According to news reports, Meherpur’s police chief told journalists that Tarique had told the police during interrogation that his associates were planning to hold a secret meeting. According to the police chief, when the police took Tarique to the place of the meeting, Tarique’s associates opened fire on the police, and Tarique was killed during the gunfight.[73] None of the news reports about the incident mention any other people killed or injured during the gunfight.

The Killing of Abu Hanif, Satkhira District

Local police claim that security forces killed 15-year-old Abu Hanif, also known as Chhoton, when he and other members of the Jamaat youth wing attacked them in the Satkhira district on January 18, 2014. Several witnesses we interviewed separately, however, said that Chhoton was in the custody of the security forces when he was killed and had been in their custody since the previous day.

News articles cited Satkhira District Police Station Officer-in-Charge Enamul Haque saying that security forces were forced to open fire on members of the Jamaat youth wing who attacked them with petrol bombs during an operation near East Bhomra around 4:30 a.m. on January 18, 2014 and that Chhoton was killed during the clashes.[74]

According to his family, security forces had been searching for Chhoton, accusing him of participating in protests and setting fire to several motorcycles in his village of Padmashakra on December 16, 2013. On January 1, 2014, security forces destroyed part of the Chhoton’s family house and set fire to property documents and clothes when they did not find him at home, according to relatives interviewed by Human Rights Watch (see chapter VI on unlawful destruction of property).[75]

On January 17, Chhoton and his friend “Monir” (pseudonym) were riding their bicycles on their way home when several men in plainclothes stopped them about 300 meters from Chhoton’s house. According to two witnesses, one of them a relative, the men grabbed the two boys, placed them in a white microbus and drove away.[76]

Monir told Human Rights Watch that the men blindfolded them and started asking them whether they had participated in protests and set fire to vehicles. They eventually discovered that Chhoton had photos of Jamaat leaders giving speeches on his phone. According to Monir, the men said that they were from the Detective Branch. The men released Monir after about three hours, but kept Chhoton.[77]

Chhoton’s family said that they searched for him all evening and night. They also contacted the Detective Branch, which denied having detained the boy.[78]

At around 4 a.m. the next day, a friend of the family called and said they had found Chhoton’s body near the East Bhomra border-crossing with India, about three kilometers from the family’s house and the place where he had been detained. He said that the body had been taken to the Satkhira Medicial College. Chhoton’s cousin, who examined the body at the college, told Human Rights Watch that the body had slash wounds from a knife or a bayonet on his back and what appeared to be four bullet wounds in his right arm, right side of the chest, and in the left side of his torso.[79] Chhoton’s cousin showed Human Rights Watch several photos that appeared consistent with his description.

The Killing of Anwarul Islam, Satkhira District

On January 14, 2014, an alleged Shibir activist was shot dead during what the police claimed was a clash between Shibir activists and joint forces in the Debhata sub-district of Satkhira district. Three witnesses told Human Rights Watch separately, however, that police had detained the victim the previous day, suggesting that Anwar was executed.

Anwarul Islam, aged 29, was a Jamaat leader in the village of Nangla in the Debhata sub-district of Satkhira district, according to his family.[80] According to a news report citing the police superintendent of Satkhira, Anwar was shot dead when police returned fire in response to an attack by Shibir activists around 10:30 a.m. on January 14 in the Debhata sub-district. The superintendent said that Anwar had been wanted in relation to a number of criminal cases, including three murders.

According to the news report, the superintendent also said that nobody else was injured in the gunfight. A district police press-release, cited in the same news report, stated that three police officers sustained minor injuries in the gunfight.[81]

Witnesses interviewed separately by Human Rights Watch, however, said that Anwar had been in custody since the previous day. Anwar’s family told Human Rights Watch that on January 13, he went to work on his shrimp farm, which was located about three kilometers from his house. According to three witnesses who also worked in the shrimp farms and who were interviewed separately, while Anwar was working several motorbikes and a police vehicle with uniformed police officers suddenly appeared on the road by the shrimp farm. Anwar initially tried to run away, the witnesses said, but he stopped and surrendered when the police officers opened fire and he realized he would not be able to out-run them.[82]

The three witnesses told Human Rights Watch that the police escorted Islam to the road. There, they said, it appeared that the police made Anwar turn his back towards them before they shot him in the leg.[83] All the witnesses said that they heard two gunshots. Afterwards, the policemen placed Anwar in the van and drove away.

The witnesses said that they were too far away to hear what the police said, but women who were standing closer to the road had told them that Islam was still alive when the police placed him in the van. A family member who later saw the body told Human Rights Watch that it had two gunshot wounds.

One bullet appeared to have hit the left buttocks and exited through his thigh. A second bullet appeared to have penetrated his chest. The family member believed Anwar had been shot in the chest from the front because the wound on his back was bigger, indicating that it might have been an exit wound.[84]

The Killing of Abdul Jabbar, Meherpur District

On December 30, 2013, a local leader and Jamaat supporter was killed while in police custody in what the authorities claim was a gunfight during a nighttime operation to retrieve a weapons cache.

Abdul Jabbar, 62, was a Jamaat supporter and an elected member of the Amjihupi Union Council in the Meherpur district, according to relatives that Human Rights Watch interviewed.[85]

A police officer from the Meherpur district police station told reporters that members of the police, RAB, and BGB detained Jabbar in the morning of December 30. Around midnight, he said, the joint forces took Jabbar with them on an operation to arrest other Jamaat and Shibir activists and to retrieve a weapons cache. During the operation, according to the police, Jabbar’s associates opened fired on the security forces and Jabbar was shot during the gunfight. Medical personnel at the hospital later declared Jabbar dead.[86]

However, neighbors told Human Rights Watch that police officers in police cars detained Jabbar from his village of Hijuli in the morning on December 30, which the police confirmed. One of Jabbar’s sons went to the Meherpur district police station the same day to give his father some clothes, but the police detained him and have since implicated him in five criminal cases. He was still in detention when Human Rights Watch interviewed his family in early February.

Around midnight the day Jabbar was detained, his relatives and neighbors saw several police cars driving through their village. About 15-20 minutes after they left, the villagers heard about 15 gunshots in the distance. One relative told Human Rights Watch:

Early next morning the village policeman went to the place where we heard the gunshots, but the only thing he saw was a pool of blood. But around 6:30 a.m. a local journalist called us and said that Abdul had been killed. Abdul was a respected member of the community. We really did not think that he would be killed.[87]

Jabbar’s close relatives told Human Rights Watch that after Jabbar’s son was detained they were afraid to contact the authorities. When they learned that Jabbar had been killed, they asked two distant relatives to go to the hospital. They said that there appeared to be three gunshot wounds on his body, two on opposite sides of his stomach and one in his chest.[88]

The Killing of Anwarul Islam, Satkhira District

On December 30, 2013, a local BNP leader was killed by security forces during what the authorities claim was a gunfight between the security forces and Jamaat-Shibir members in the Satkhira district. Relatives of the opposition leader, however, claim that security forces detained him earlier in the day.

Anwarul Islam, 45, was the chairman of the Agardari Union Council (the smallest local administrative unit in Bangladesh) in Satkhira district and a member of BNP.

According to a news website, a police officer from the Satkhira police station said that Islam had been killed when security forces opened fire on a group of Jamaat-Shibir members who attacked them near Shikri, an agricultural area about eight or nine kilometers from Islam’s house.[89] The officer-in-charge of Satkhira district reportedly told journalists that the gunfight lasted for an hour.[90] News reports citing police officers do not mention any other people being injured or killed in the hour-long gunfight.

Islam’s relatives told a different story. They told Human Rights Watch that on the morning of December 30, 2013, five people pretending to be journalists came to Kashimpur village saying they wanted to photograph Islam’s destroyed house. They even had cameras. A large number of security forces had previously cordoned off and destroyed his house in the village on December 17, 2013 (see chapter VI on unlawful destruction of property).

However, when Islam showed up, along with his two brothers, the men pulled out revolvers and grabbed him. They beat him and placed him in a white microbus. The microbus drove away with two police vehicles that pulled up in front of the house, according to relatives. One relative told Human Rights Watch:

We trusted those people, believing them to be journalists. But as soon as he [Anwarul Islam] came out, they grabbed him. They started beating him, and tied his hands behind his back. They were beating him as they dragged him to the vehicle. They broke his arm, and he was screaming. When his brothers tried to save him, the men threatened to shoot them. The brothers were frightened so they ran away... We found out that he had been taken to the Circuit house. But by the time we got there, they had already taken him away. Later, we heard that he was beaten badly there. They took him to the rice field and shot him…. We don’t know who these people are, but If it was not police or administration, who else will kill him?

They picked him up at 11 am. And within two hours, he was dead. He was an ordinary man, a good man. There were no complaints against him. We could have accepted it if he had committed a crime and was hanged. But they just killed him.[91]

In the afternoon the family heard that his body had been found in a rice field in Shikir and had already been taken to the hospital. It had seven gunshot wounds. Relatives who saw Islam’s body in the hospital said they found his mouth stuffed with grass, possibly to gag him. He had been shot in leg, neck and chest. His body also had bruise marks from the beatings, and his arm was broken.

His relatives believe that it was the police that arrested Islam. “As soon as the men saying that they were journalists had caught Islam, two police cars turned up. We can’t trust anyone anymore,” one relative said.[92]

The Killing of Dr. Faiz Ahmed, Laximpur District

On December 14, 2013, members of RAB stormed the house of Dr. Faiz Ahmed, the vice-president of the Laxmipur chapter of Jamaat-e-Islami. Dr. Ahmed died during the security operation, having fallen from the roof with apparent gunshot wounds to his leg and head.

On December 12, 2013, a RAB operation to detain a local BNP leader, during which the leader was shot in the leg, sparked clashes between BNP supporters and the RAB. Five people were killed and 50 injured in the clashes, according to media reports.[93] According to Dr. Ahmed’s family members, Dr. Ahmed was not involved in the December 12 protests but as a doctor, he treated 10-12 of the wounded in his private hospital.[94] Because of this and his high-ranking position in the Jamaat, the family suspected that RAB might try to arrest Dr. Ahmed. “My father didn’t want to hide,” his son told Human Rights Watch. “He told us that if they want to, let them arrest me.”

At around 11:45 p.m. on December 14, 2013, the Ahmed family was woken up by loud knocks on the door and shouts for them to open up, according to Dr. Ahmed’s wife and son. From the window on the second floor they saw a black SUV with the letters RAB written on the side. Six to eight men dressed in black were standing outside the house. Dr Ahmed’s son told Human Rights Watch that, fearing for his life, he hid on a window sill on the second floor.

The RAB members broke down a side-door and searched the ground-floor office before they moved up to the living quarters on the second floor.

Dr. Ahmed’s wife told Human Rights Watch:

While the men were downstairs, my husband got dressed, prepared his insulin and asked us to pray for him. He then opened the door for the men. An officer grabbed him and asked him whether he was Dr. Faiz. When my husband answered that he was, the officer pushed him onto the stairs leading up to the roof. One group dragged him upstairs while another group took our cell-phones and put us in a different room while they started searching the house.[95]

From his hiding place, Dr. Ahmed’s son heard a muffled bang from the roof and then a thump from the ground below, as if something had fallen off the roof. Thinking it was a trick to lure him out of his hiding place, he stayed concealed, he told Human Rights Watch.

After some time Dr. Ahmed’s wife noticed that everything had gone quiet in the house. She told Human Rights Watch that she went to the front room and looked out the window:

From the window I saw that there was a body lying on the ground in front of the house and lots of people standing around. The men in black picked up the body and took it away in the car. The only thing left was two pools of blood, one from his head and one from his leg.[96]

The family later learned from an acquaintance in the government hospital that the body of Dr. Ahmed had been left at the entrance of the hospital. The family told Human Rights Watch that they are too scared to go to the hospital and that they have received no official documents about the cause of death. A doctor at the hospital told them, though, that the RAB had pressured the hospital to classify the death as an accident or suicide.[97]

Human Rights Watch reviewed photos that journalists had taken of the body in the hospital which appear to show that Dr. Ahmed had sustained wounds to the leg and head.[98]

An unnamed RAB officer claimed to a journalist that Dr. Ahmed had tried to escape to the roof to jump to an adjacent building when he slipped and fell to the ground. The officer provided no explanation for the gunshot wounds, however.[99]

Family members told Human Rights Watch that a relative had tried to lodge a complaint about the killing with the local police, but that the police refused the complaint because it was against RAB.[100]

Other Apparent Extrajudicial Executions

Human Rights Watch did not have the time, resources, or access to investigate all alleged extrajudicial executions that were brought to our attention. The following cases of possible extrajudicial executions have been reported by local and international media, Bangladeshi human rights organizations, or political parties. Though Human Rights Watch has not investigated these cases firsthand, they are similar in important respects to the cases documented in this report and warrant independent investigation.

- On February 25, 2014, Rakib Hasan Russell, a leader of the banned organization Jama’atul Mujahideen Bangladesh, was allegedly killed in a gunfight during a nighttime police operation one day after he was arrested, according to news reports citing police authorities.[101]

- On February 16, Rajab Ali was allegedly killed in a gunfight during a nighttime police operation hours after he was detained, according news reports citing police authorities.[102] The National Human Rights Commission, which investigated the incident, concluded that no gunfight had taken place.[103]

On Febuary 15, 2014, the body of Jahangir Alam, a suspect in the murder of an Awami League leader, was discovered in Sirajganj. Ten days earlier, another suspect, Joban Ali, was also found dead. Ali’s wife told journalists that plainclothes members of law enforcement agencies had detained Alam and Ali on January 19, 2014.[104] A third suspect, Bablu Miah, was allegedly killed during a nighttime operation by RAB, according to news reports citing a RAB commander.[105] Human Rights Watch is not aware of any allegation that Miah was previously detained.

- On January 28, 2014, Touhidul Islam Shabuj, a leader of the banned Purba Banglar Communist Party, was killed during a nighttime police operation one day after he was detained, according to police authorities cited in news reports.[106]

- On January 28, 2014, Robiul Islam was allegedly killed in a gunfight during a police operation one day after he was arrested, according to news reports citing police authorities.[107] The family claimed that Islam was a local BNP activist, but the police and a local BNP leader denied the affiliation.[108]

- On January 26, 2014, Enamul Haque, the finance secretary of a local Jamaat unit in Jhenaidah district, was allegedly killed in a gunfight during a nighttime operation in Jhenidah, according to news reports citing police authorities. A local Jamaat leader and Haque’s brother, however, told journalists that police had detained Haque the previous day in front of a large crowd of people.[109]

Most of the alleged crossfire deaths took place at night with no witnesses, making it difficult to find witnesses in many cases. But several factors significantly undermine the credibility of the authorities’ claims. First, the sheer number of detainees allegedly killed in “crossfire” is implausible. While the term “killed in crossfire” normally means an accidental death, Bangladeshi security forces have used the term so often in recent years to justify the death of detainees that the term, when used in Bangladesh, is now understood in everyday speech as a euphemism for a summary execution. As one lawyer told Human Rights Watch, “I begged the police not to kill my client in crossfire when he was arrested, but they didn’t listen.”[110] Even some political leaders, rather than claiming that the killings take place during genuine armed confrontations, seek to justify the killings as a necessary response to “terrorism.”[111]

Second, in most of the 2014 cases we and others documented, the detainee was the only person killed in the “gunfights.” None of the alleged associates of the detainee launching the attack have been reported to have been killed, injured, or even detained. While the authorities claimed in a couple of the cases that security forces were injured in the alleged gunfights, the injuries were all described as minor, requiring only basic treatment. No members of the security forces were killed during these alleged attacks. The lack of injuries to anyone other than the detainee is particularly striking since the authorities in more than one case claimed that the gunfight lasted for up to an hour.

Third, in a number of cases described above, witnesses contradicted the authorities’ assertion that the victim had not been in their custody before the killing. The authorities’ failure to acknowledge the detention casts doubt on other aspects of the official version of the killings.

VI. Illegal Arrests Leading to Deaths and Disappearances

In 10 cases researched by Human Rights Watch, individuals were illegally arrested by people who witnesses claim identified themselves as police or RAB. In some cases, witnesses said that victims were taken away in vehicles marked as RAB vehicles. In 7 of the 10 cases the victims’ bodies have been found, often by the roadside. The authorities denied involvement in all cases.

Disappearance of Omar Faruk, Laximpur District

On February 5, 2014, a group of men identifying themselves as members of the Detective Branch of the Bangladesh police arrested a BNP leader in Laximpur district. When we spoke with his relatives more than a week after he was arrested, they told us they still did not know his whereabouts.

Omar Faruk is the chairman of the Hazirpara union of Laxmipur district and the Organizing Secretary of the BNP Sadar Upazila (east) unit.

According to Faruk’s wife, the couple was staying in the apartment of relatives in Chittagong city when the incident occurred. Two family members told Human Rights Watch that around 4 a.m. on February 5, 2014, a group of about eight men knocked on their door, waking them up. One of them told Human Rights Watch:

The men were not in uniform, but said they were from the Detective Branch and one of them showed his ID card. They said they did not have a warrant but wanted to search the apartment. They said Faruk was wanted in connection with an investigation. The men then took him outside, to where a pick-up truck was waiting. It was black, with RAB-7 written on the side.[112]