The Risk of Returning Home

Violence and Threats against Displaced People Reclaiming Land in Colombia

Glossary

“Aliases”: Members of armed groups and criminal gangs often have an alias—essentially a nickname or nom de guerre. In this report, aliases are italicized.

Attorney General’s Office of Colombia (Fiscalía General de la Nación): a Colombian state entity charged with conducting most criminal investigations and prosecutions. The Attorney General’s Office is formally independent of the executive branch of the government.

Early Warning System of the Ombudsman’s Office of Colombia (Sistema de Alertas Tempranas de la Defensoría del Pueblo): The Ombudsman’s Office (Defensoría) is a Colombian state entity charged with promoting and defending human rights and international humanitarian law. The Early Warning System is a subdivision of the Ombudsman’s Office, charged with monitoring risks to civilians in connection with the armed conflict, and promoting actions to prevent abuses.

Colombian Institute for Rural Development (Instituto Colombiano de Desarrollo Rural, INCODER): a Colombian state entity charged with rural development, which also carries land restitution processes.

“Land Takeovers”: refers here to conduct that falls within the definition of despojo set out in article 74 of the Victims Law: “the action through which, taking advantage of the situation of violence, one arbitrarily deprives a person of his property, possession, or occupation [of land], whether it be de facto, or through a legal transaction, administrative act, judicial decision, or the commission of crimes associated with the situation of violence.” While Colombian law does not codify land takeovers associated with forced displacement (despojo) as a crime, the conduct can be prosecuted under a range of other crimes.

“Land claimant”: refers here to IDPs who have sought to recover lost land through a range of judicial and administrative mechanisms, such as the Victims Law and Justice and Peace Law, or who have simply petitioned for authorities to support them in returning home. It also includes IDPs relocated by the government to new rural areas, because such relocations are stipulated to take place under the Victims Law when inadequate security or environmental conditions, among other reasons, bar returns.

“Leaders” or “Advocates”: used interchangeably here to refer to persons with a leadership role representing fellow community members or IDP groups in restitution efforts. The terms are used broadly to include victims’ lawyers. In many cases, leaders have also pursued restitution claims for their own families.

National Protection Unit (Unidad Nacional de Protección, UNP): a Colombian state entity charged with providing protection measures to at risk populations, including trade unionists, human rights defenders, and land restitution leaders.

“Paramilitary front man”: individuals who hold assets—including land—on behalf of members or leaders of paramilitary groups to hide their ownership of such assets.

“Preliminary stage of investigation”: refers here to the stage of a criminal investigation denominated as “investigación previa” or “indagación” in the Colombian justice system. At this stage, prosecutors have not yet charged a suspect.

Restitution Unit (Unidad Administrativa Especial de Gestión de Restitución de Tierras Despojadas): a Colombian state entity attached to the Agricultural Ministry that is charged with implementing land restitution under the Victims Law.

Victims Unit (Unidad para la Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas): a Colombian state entity charged with managing the government’s registry of victims and providing them with humanitarian assistance and reparations, among other measures. The Victims Unit coordinates the return and relocation process for IDPs, including those who have benefited from land restitution rulings obtained by the Restitution Unit.

Summary

Over the past 30 years, abuses and violence associated with Colombia’s internal armed conflict have driven more than 4.8 million Colombians from their homes, generating the world’s largest population of internally displaced persons (IDPs).

Mostly fleeing from rural to urban areas, Colombian IDPs are estimated to have left behind 6 million hectares of land—roughly the area of Massachusetts and Maryland combined—much of which armed groups, their allies, and others seized in land grabs and continue to hold. Dispossessed of their land and livelihoods, the vast majority of Colombian IDPs live in poverty and lack adequate housing.

In June 2011, the administration of President Juan Manuel Santos took an unprecedented step toward redressing this immense human rights and humanitarian problem by securing passage of the Victims and Land Restitution Law (Victims Law). The law established a hybrid administrative and judicial process intended to return millions of hectares of stolen and abandoned land to IDPs over the course of a decade.

The land restitution program represents the most important human rights initiative of the Santos administration. If implemented effectively, it will help thousands of families who have been devastated by the conflict to return home and rebuild their lives, while also undercutting the power of armed groups and criminal mafias. Already, the government’s Restitution Unit has made notable gains in carrying out the law in some regions.

Despite this progress, major obstacles stand in the way of effective implementation of the law. IDPs who have sought to recover land through the Victims Law and other restitution mechanisms thus far have faced widespread abuses tied to their efforts, including killings, new incidents of forced displacement, and death threats. Since January 2012, more than 500 land restitution claimants and leaders have reported being threatened.

This report—based on research between February 2012 and July 2013, including hundreds of interviews, more than 130 of them with land restitution claimants and leaders—details those abuses, assesses the government’s response to date, and recommends additional steps authorities should take.

The government has consistently denounced attacks against IDPs seeking restitution, and provided hundreds of at-risk claimants with protection measures, including cell phones and bodyguards. However, we found that while important, these measures have not been complemented by sufficient efforts to hold perpetrators accountable, which are absolutely critical to stemming the ongoing source of threats to claimants’ lives and preventing attacks.

The threats and attacks are entirely predictable given Colombia’s chronic failure to deliver justice for both current and past abuses against IDP claimants. Crimes targeting IDPs in retaliation for their restitution efforts almost always go unpunished: prosecutors have not charged a single suspect in any of their investigations into threats against land claimants and leaders.

Justice authorities also rarely have prosecuted the people who originally displaced claimants and stole their land. Of the more than 17,000 open investigations into cases of forced displacement handled by the main prosecutorial unit dedicated to pursuing such crimes, less than 1 percent have led to a conviction. The lack of justice for these crimes is a root cause of the current abuses against IDP claimants: those most interested in retaining control of the wrongfully acquired land often remain at large and are more readily able to violently thwart the return of the original occupants.

Colombia’s failure to significantly curb the power of paramilitary successor groups also poses a direct threat to land claimants’ security, while more broadly undermining the rule of law in areas where IDPs seek to return. These groups inherited the criminal operations of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) paramilitary coalition, which carried out widespread land takeovers prior to the government’s deeply flawed demobilization process. Thus far, successor groups have carried out a large share of the threats and attacks targeting IDP claimants and leaders. In addition, third parties who moved onto or acquired the land after the original occupants were forced out, as well as Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas, have also targeted claimants for their restitution efforts.

Over the next eight years, the government intends to address land restitution claims filed by hundreds of thousands of displaced people. Unless Colombia ensures justice for current and past abuses against IDP claimants and makes substantial progress in dismantling paramilitary successor groups, many of these families will suffer more threats, episodes of displacement, and killings. And the Santos administration’s signature human rights initiative could be fundamentally undermined.

Widespread Abuses

IDP land claimants and leaders have been subject to widespread abuses due to their restitution efforts, including killings, intimidation and threats, and new incidents of forced displacement. This report documents such cases involving victims reclaiming land through the Victims Law—and other restitution mechanisms—from the departments of Antioquia, Bolívar, Cesar, Chocó, Córdoba, La Guajira, Sucre, and Tolima, as well as Bogotá. Official data and other forms of evidence reviewed by Human Rights Watch indicate that the pattern of abuses extends throughout the country.

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch documented 17 cases of killings of IDP land claimants and leaders since 2008—in which 21 people died—where there is compelling evidence that the attacks were motivated by the victims’ land restitution efforts or activism. In four additional cases it was not clear, based on available information, whether the killing was related to the victim’s restitution efforts, though there are signs that it may have been. We also documented two attempted killings and one kidnapping of a restitution leader. The victims of these killings and attacks—committed in five different departments—include grassroots leaders, individual claimants, their family members and lawyers.

Reports by government authorities and international bodies indicate that killings of land restitution claimants and leaders have occurred on an even greater scale. For example, as of August 2013, the Attorney General’s Office reported that it was investigating 49 cases of killings of “leaders, claimants, or participants in land restitution matters” committed in 16 departments since 2000, in which 56 people were murdered. The government’s Ombudsman’s Office reported at least 71 killings of land restitution leaders in 14 departments between 2006 and 2011.

The killings have instilled an enduring fear of attack not only in the victims’ family members and fellow claimants, but also among authorities working on restitution. In a March 2013 letter to President Santos, dozens of specialized land restitution judges from across the country requested protection measures and expressed serious concern for their safety, stating, “The attacks against victim claimants, their leaders, and members of the organizations that have supported them are well known. As justice officials, we are equally or even more exposed [to attacks], because we are the ones who order the legal and material restitution.” As described by the director of the government’s protection program, the strategy of the perpetrators is to “kill a few people in order to send a message to many.”

Pressure on those seeking restitution comes not only from the killings, but—much more widely—from death threats against claimants, their families, and those who advocate for them. In March 2013, the national director of the Restitution Unit identified such threats as the most common way people have attempted to torpedo the land restitution process.

Human Rights Watch documented serious, credible threats against more than 80 IDP land claimants and leaders from Bogotá and eight other departments since 2008, and this is a small portion of the total reported number. According to government data, at least 500 IDP land claimants and their leaders from more than 25 departments have reported such threats to authorities since January 2012. Based on individual evaluations, authorities have found upwards of 360 threatened claimants and leaders to be at “extraordinary risk” due to their land restitution activities—a determination that requires the risk to be, among other criteria, “concrete,” “serious” and “exceptional.”

The threats—which are crimes in Colombia—are conveyed in a variety of ways: in writing, by text message, by phone, or by verbal face-to-face warning. The content varies, but many of the messages include threats to kill the victims or their family members if they do not give up their attempts to reclaim their land or leave the region.

Usually, the threats appear credible and are terrifying. Many are directed at victims traumatized in the past by paramilitaries or guerrillas, including by the very attacks on themselves, their families, or their neighbors that induced them to flee their land in the first place. Guerrillas and successor groups to paramilitaries frequently maintain a presence in the areas where victims are reclaiming land, and the latter in particular have demonstrated a willingness to kill restitution claimants and leaders. Many victims believe, with good reason, that the current threats are from individuals or groups directly linked to the long chain of violence and land theft that they and their families have experienced.

For example, Lina Rivera (pseudonym) reported that paramilitaries displaced her and her family from their farm in Cesar department in 1999, and subsequently killed her husband, brother, and son. Evidence strongly suggests that a paramilitary commander’s brother acquired their farm and repeatedly threatened Rivera and her children for attempting to reclaim it. In a 2011 phone call, the paramilitary’s brother told her, “Remember what happened to your brother, remember what happened to your son.” Continued threats against Rivera’s family led her to flee the region once again in late 2012.

Like Rivera, many IDP land claimants and leaders have fled their places of residence, displaced yet again due to threats or attacks related to their restitution efforts or activism. In researching this report, Human Rights Watch documented more than 30 such cases from seven departments since 2008. For example, in the first restitution cases under the Victims Law in Bolívar, Cesar, and Córdoba departments, repeated threats against IDP leaders caused them to flee their homes once again. Official data indicates that the problem is more common. Since January 2012, the government’s protection program has temporarily relocated more than 90 land claimants and leaders to new areas because of grave threats to their lives due to their activism.

When threats force leaders to abandon their homes, the community or region loses a trusted spokesperson and bridge between community members and authorities, setting back broader restitution efforts. In many cases, such threats violate a provision in Colombian criminal law defining the crime of forced displacement as coercive acts that cause someone to change homes.

Some authorities have downplayed the problem of threats by arguing that even several hundred threats is a relatively low number given the tens of thousands of claims filed under the Victims Law thus far. While the proportion is small, there are several reasons to conclude that the problem is not.

First, threats often instill a lasting sense of insecurity and fear among victims, pressuring them to consider abandoning their efforts to reclaim their land. Second, threats targeting leaders have a multiplier effect because they inhibit them from working on others’ behalf, while also sending an intimidating message to the community members they represent. Third, it is not uncommon for threats to induce IDP claimants and leaders to flee the places where they are living, often with family members, forcing them to confront yet again the economic and social hardships that arise from displacement. These new incidents of displacement directly undermine one of the key principles enshrined by the Victims Law: the right to non-repetition of abuses.

And if it is not addressed the problem is likely to get much worse. The Victims Law is still in its initial stage of implementation. As of June 2013, the Restitution Unit had started to examine less than 20 percent of the more than 43,500 land claims it had received, and obtained rulings ordering restitution in roughly 450 of them. Just one family had returned to live on their land as a result of these rulings under the Victims Law and with the support of the government office coordinating IDPs’ return home (though many other beneficiaries of the rulings were visiting their land to use it for farming). By 2021, the government estimated that it would hand down land restitution rulings concerning hundreds of thousands of claims, implying the return of tens of thousands of families. It is reasonable to expect that the level of threats will significantly increase as the thousands of pending claims progress, families return home, and those intent on retaining wrongfully acquired land see their interests more directly affected.

Perpetrators

In a July 2012 speech, President Santos identified the principal perpetrators of threats against land claimants: “Many of the people making threats … are the owners or supposed owners of the pieces of land that have been reclaimed…. There are other sectors. Sectors that I have called of the extreme left … and of the extreme right, who are linked to the old paramilitaries, who do not want the land they wrongfully appropriated to be taken away from them.” Human Rights Watch similarly found that paramilitary successor groups, third parties who took over the IDPs’ land—sometimes in collusion with paramilitaries—and, in certain areas, FARC guerrillas, are the main perpetrators of abuses targeting land claimants and leaders.

In the majority of the cases of killings, attempted killings, and new incidents of forced displacement that we documented, the evidence strongly suggests that paramilitary successor groups—particularly the Urabeños—are responsible; the same groups are also responsible for a significant portion of threats. Information provided to Human Rights Watch by a range of government offices bolsters these findings. Paramilitary successor groups engage in drug trafficking and other mafia-like criminal activities in many of the areas where paramilitary networks previously carried out land grabs, such as Córdoba and Urabá, where a large share of the killings of IDP claimants and leaders have been committed.

The November 2011 abduction of Héctor Cavadía, a restitution leader from the town of Totumo, Antioquia, is a prime example of a targeted attack by the Urabeños. While abducted, Cavadía said that Urabeños members told him the land he was reclaiming had an owner and interrogated him about other restitution leaders from his IDP association. During a 2011 meeting in the region, an Urabeños commander ordered that “anyone who was going to reclaim land … would be disappeared,” according to the judicial testimony of an ex-Urabeños member.

Third parties who acquired or occupied the land after the original inhabitants were forced out have also been responsible for many of the abuses. These third parties range from cattle ranchers and businesspersons to demobilized paramilitaries. Evidence strongly suggests that successor groups and others have intimidated, threatened, and, in a few cases, even killed claimants on behalf of third parties.

Finally, in some areas FARC guerrillas have threatened and killed IDPs seeking restitution. Germán Bernal, for example, a man active in campaigning for the return of IDPs to Santiago Pérez, a town in southern Tolima department, said that the FARC’s 21st Front has repeatedly threatened him due to his efforts. Bernal and other IDP leaders reported that during obligatory meetings held by the FARC in rural areas of southern Tolima, the guerrillas, apparently motivated by their desire to maintain control there, announced their opposition to IDPs retuning home and declared that IDP leaders were “military targets.” Government statistics indicate that guerrilla threats extend to other parts of the country: since January 2012, more than 50 claimants and leaders from at least 13 departments seeking restitution through the Victims Law have told authorities they were threatened by guerrillas.

The FARC as well as National Liberation Army (ELN) rebels also have a long history of using antipersonnel landmines, and the presence of landmines in areas where such groups are or were active poses a serious obstacle to the safe return of IDPs. Roughly 70 percent of the municipalities where restitution claims have been filed are places where the government has previously reported accidents or incidents related to antipersonnel landmines or unexploded ordnance, according to the Restitution Unit.

The Government’s Response

The Colombian government’s response to abuses against IDP land claimants and leaders has largely consisted of high-level officials condemning the attacks and threats, and protection measures provided by the National Protection Unit (UNP). While the UNP has flaws, it is the most advanced program of its kind in the region, and its protection measures—particularly bodyguards—are potentially lifesaving.

The condemnations of such attacks by officials and UNP protection, however, are essentially palliative measures. They do not help rein in and hold accountable perpetrators, the source of ongoing threats to claimants’ lives. Indeed, the UNP’s inherent limitations are evidenced by the fact that the program often has to relocate threatened claimants because their safety cannot be guaranteed where they live.

Colombia has fallen short in three key areas that are at the root of violence and threats against IDP land claimants and leaders:

- There has been very little accountability for threats and attacks targeting IDP claimants in retaliation for their restitution efforts. This means little effective deterrence for such crimes.

- Justice authorities have consistently failed to prosecute those responsible for the original forced displacement of people and related land takeovers. This exposes claimants to attack, because it often means that the individuals, groups, or criminal mafias with a vested interest in maintaining control of the land are off the radar of law enforcement authorities and more readily able to oppose restitution through violence and intimidation.

- The government’s failure to effectively dismantle paramilitary successor organizations in different regions of the country allows these groups to carry out ongoing abuses against claimants.

Added to this, authorities in different regions, including police, have downplayed the seriousness of threats and prematurely assumed that attacks are unrelated to the victims’ activism. This attitude is reflected in the lack of action on the part of some regional authorities to provide meaningful protection for IDPs who have received credible threats and to vigorously pursue the perpetrators of crimes against them.

Lack of Accountability for Threats and Killings

The Attorney General’s Office has prioritized the investigations of killings allegedly tied to land restitution efforts by assigning many of them to the Human Rights Unit and other specialized prosecutors based in Bogotá and Medellín, who are less vulnerable to intimidation. This has led to substantial progress in some important cases. Overall, however, the results have been modest: as of August 2013, prosecutors had obtained convictions in eight of the 49 cases of killings of land claimants and leaders the Attorney General’s Office reported it was investigating, and in more than two-thirds of the cases, no suspects had been charged. Prosecutions have been impeded by long delays in moving cases to specialized prosecutors in Bogotá and Medellín and, according to some prosecutors we spoke with, the failure to take basic steps to advance investigations.

There has been even less accountability for perpetrators of threats. The Attorney General’s Office reported that all of its investigations into threats against IDP land claimants and leaders are only at a preliminary stage, which means that no one has been charged in a single case. Threats are unquestionably difficult to investigate, but victims say they face an array of unnecessary obstacles when seeking justice, particularly outside of Colombia’s main cities. These include justice authorities downplaying the nature of the threats, failing to contact them after they file a criminal complaint, or even refusing to accept a criminal complaint in the first place. Such responses show that some authorities lack the will to pursue these cases, exacerbating victims’ distrust of authorities, leading to under-reporting of threats, and virtually eliminating any chance for accountability.

Along with sending a message to perpetrators that they will not face consequences, the lack of adequate criminal investigations into threats also makes it difficult to evaluate their relative urgency and seriousness. This impedes the government’s protection program from efficiently assigning protection measures in accordance with the claimants’ level of risk.

Lack of Accountability for the Original Forced Displacement and Land Takeovers

Under the Victims Law, restitution claims are registered in an administrative process and resolved by civil courts that do not establish criminal liability for those responsible for the forced displacement and land takeovers in individual cases. The advantage of this approach is that it allows cases to be expeditiously processed. But it also gives rise to a fundamental gap in the law’s implementation: claims are advanced and land is returned without a parallel process to hold accountable the individuals, groups, and criminal networks responsible for the forced displacement and land theft.

This accountability gap poses a serious threat to the safe return of thousands of IDPs. However, justice authorities, in a position to fill this gap, have made little progress in pursuing the perpetrators of forced displacement and illegal land acquisitions that originally drove the claimants from their homes.

- As of January 2013, Colombia’s main prosecutorial unit dedicated to pursuing forced displacement, the National Unit against the Crimes of Enforced Disappearance and Displacement (UNCDES), had obtained convictions in less than 1 percent of its more than 17,000 open investigations into cases of forced displacement. More than 99 percent of the investigations were at a preliminary stage, meaning that no suspects had been charged.

- As of March 2013, nearly eight years after the Justice and Peace paramilitary demobilization law took effect, defendants participating in the process had confessed to more than 11,000 cases of forced displacement. Yet Justice and Peace unit prosecutors had obtained convictions for just six cases of forced displacement.

- As of January 2013, of the nearly 21,000 open investigations into cases of forced displacement handled by prosecutors outside of the UNCDES or Justice and Peace unit, more than 99 percent were at a preliminary stage. In Córdoba and Chocó departments, all of such prosecutors’ more than 3,400 open investigations into cases of forced displacement were at a preliminary stage.

- The UNCDES also identifies itself as the main office tasked with conducting criminal investigations of the illegal takeovers of land that IDPs left behind. As of January 2013, it had produced even fewer results in this area, having obtained just three convictions for crimes related to land takeovers.

To its credit, the Attorney General’s Office has taken steps to address one overarching investigative flaw that has thus far impeded accountability for past and current abuses against IDP claimants: the failure to seek evidence of connections between crimes related to the same piece of land, community, or region. The existing case-by-case approach has prevented prosecutors from establishing patterns that lead to the identification of all responsible parties. In 2012, Attorney General Eduardo Montealegre started to implement a new “contextualized” investigation strategy throughout the office. If effectively carried out in conjunction with the elimination of other obstacles to justice identified in this report, the new strategy could help significantly improve accountability for crimes related to restitution.

Continued Power of Paramilitary Successor Groups

Despite considerable gains in capturing paramilitary successor group leaders, Colombian authorities have failed to significantly curb the power of such groups.

Data from the National Police show that the size of the groups has essentially remained constant over the past four years, dipping slightly from 4,037 members in July 2009 to 3,866 members in May 2013. The Urabeños, Colombia’s largest and most organized paramilitary successor group, has grown in membership in 2013.

Labeled “emerging criminal gangs” (Bacrim) by the government, successor groups continue to commit widespread abuses against civilians, such as massacres, killings, and forced displacement. According to the 2012 annual report of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which has an extensive field presence throughout Colombia, successor groups cause at least as many deaths, threats, incidents of displacement, and disappearances as does the internal armed conflict between the FARC and government forces. Successor groups drive thousands of people from their homes each year, including, in some cases, IDPs attempting to return to their land.

For example, Ermes Vidal Osorio and Ever Cordero Oviedo,two recognized IDP leaders from Valencia, Córdoba, were murdered within a 20-day span in March and April 2013, evidence suggests by the Urabeños. Both belonged to a committee created in Valencia to ensure victims’ participation in Victims Law implementation. Shortly after Cordero’s murder, threats and intimidation by presumed Urabeños members forcibly displaced 34 of his family members from Valencia, including 22 children.

The enduring power of paramilitary successor groups poses a direct threat to land claimants and leaders, as evidenced by their track record of attacking such individuals. Furthermore, in a broader sense, their power undermines the rule of law in many of the areas where land restitution is being implemented, corrupting members of the security forces and discouraging witnesses from providing information to justice officials. As the Attorney General’s Office acknowledges, a primary obstacle to the prosecution of threats against land claimants is the victims’ fear that paramilitary successor groups will punish them if they cooperate with investigations. Effective efforts to combat successor groups—including by breaking their links with security forces in certain regions—should be seen as an essential precondition for effective implementation of the Victims Law.

Recommendations

Currently, there is a fundamental gap in Colombia’s restitution policy: the process of returning land is not being accompanied by parallel efforts to ensure justice for abuses against IDPs. Restitution claimants and leaders are frequently targeted in large part due to authorities’ chronic failure to prosecute those responsible for displacing them and seizing their land, as well as the threats and attacks aimed at preventing them from returning home. The Attorney General’s Office has not consistently conducted investigations that explore patterns across crimes related to the same pieces of land, communities, or suspected perpetrators, and some local justice officials have shown a lack of will to pursue cases of threats altogether.

Strategic interventions by prosecutors, in coordination with restitution efforts, could go a long way toward ensuring justice—and thus protection—for those seeking to return to their land. Under the Victims Law, land restitution is gradually implemented across successively prioritized land plots, towns, and regions. We believe the Attorney General’s Office should focus its efforts to prosecute crimes targeting IDPs in the same areas where the Restitution Unit is examining claims. Such coordination would take advantage of the concentration of complaints concerning related cases, allowing prosecutors to carry out systematic investigations of forced displacement, land takeovers, threats, killings, and other abuses against IDPs seeking to reclaim land. This more holistic approach would be a powerful and efficient strategy for filling the current accountability gap in the land restitution process.

Such an approach would need to be complemented by improved efforts to dismantle paramilitary successor groups and protect threatened claimants in a timely fashion. To this end, the government should adopt vigorous measures to root out collusion between paramilitary successor organizations and local officials, bolster its capacity to monitor the risks these groups and others pose to restitution claimants, and ensure that such individuals promptly receive adequate protection when their lives are in danger.

To the Santos Administration

Ensure Accountability for Abuses against Restitution Claimants and Leaders

- Provide sufficient resources to the Attorney General’s Office so that it can create teams of prosecutors and judicial investigators tasked with pursuing crimes against IDP land claimants and their advocates, including the incidents of forced displacement and land theft they originally suffered, and all killings, attacks, and threats tied to their current efforts to reclaim land. The teams should be based out of Colombia’s main cities, but routinely conduct field visits to each city or town where the Restitution Unit has an office in order to receive criminal complaints and investigate them. The teams should also investigate crimes linked to land restitution cases being processed through mechanisms other than the Victims Law. (See more details in recommendations to the Attorney General.)

- Issue a directive instructing Restitution Unit officials to immediately inform prosecutors when they come across evidence of forced displacement or illegal land takeovers.

- Ensure that any future implementing legislation for the Legal Framework for Peace, a constitutional amendment enacted in July 2012, does not exempt from criminal investigation cases of forced displacement and other grave violations of human rights and international humanitarian law.

Provide Timely and Effective Protection to at-Risk Claimants and Leaders

- Ensure that the Early Warning System in the Ombudsman’s Office has the staff and resources necessary to monitor potential threats to land claimants and leaders in regions where the restitution process is underway.

- Ensure that that Carabineers division of the National Police, which operates in rural regions, is adequately staffed and funded to maintain security in the communities where IDPs return.

- To minimize delays in providing protection measures to at-risk restitution claimants and leaders, set time limits between the different stages of the National Protection Unit’s (UNP) process for evaluating protection requests and assigning measures. This should include establishing and enforcing limits between the times that the UNP receives a protection request and completes a risk evaluation of the potential beneficiary; as well as time limits between the completion of the risk evaluation, the determination by the Committee for the Evaluation of Risk and Recommendation of Measures (CERREM) as to the appropriate protection measures to be taken, and the UNP’s effective implementation of these measures.

- Address the shortcomings in the UNP’s protection measures for women IDP leaders outlined in Constitutional Court order 098 of 2013, including inadequate coverage of the beneficiary’s close family members.

- Ensure that, in accordance with recent Constitutional Court rulings, the Victims Unit registers and provides attention, assistance, and protection to people—including restitution claimants and leaders—who are displaced by paramilitary successor groups or flee their homes due to other situations described in Law 387 of 1997.

To the Attorney General

- Conduct vigorous, full investigations into all alleged incidents of forced displacement and land takeovers, killings, attempted killings, and threats documented in this report, with a view to prosecuting all parties responsible.

- Create teams of prosecutors and judicial investigators tasked with investigating crimes against IDP land claimants and their advocates (see above). Pursuant to Directive 01 of 2012, prioritize as “situations” crimes related to land restitution (including incidents of forced displacement and land takeovers, as well as threats and attacks against claimants tied to their reclamation efforts) that have occurred in the same areas where land restitution is being implemented. In coordination with the Restitution Unit and other offices working on restitution, the teams should conduct systematic investigations of these “situations,” taking advantage of the concentration of regional complaints to pursue evidence of links between cases in order to identify patterns and all responsible parties. (It is important to note, however, that not all people who moved onto or acquired land being reclaimed by IDPs bear criminal liability for the acquisition of such land.)

- Immediately assign to the specialized team of prosecutors all future cases of threats, killings, and other attacks against land restitution claimants and leaders.

- Request that judges expel from the Justice and Peace process and exclude from sentencing benefits any paramilitary or guerrilla defendant who has not provided complete information to prosecutors regarding 1) incidents of forced displacement or associated land takeovers in which they participated or 2) land that they directly or indirectly acquired due to their membership in an irregular armed group.

- Ensure that the specialized unit of prosecutors dedicated to investigating paramilitary successor groups prioritizes investigations into state agents credibly alleged to have colluded with or tolerated the groups.

Methodology

This report documents abuses against land restitution claimants and leaders from the departments of Antioquia, Bolívar, Cesar, Chocó, Córdoba, La Guajira, Sucre, and Tolima, as well as Bogotá. These eight (out of 32) departments concentrated the majority of the land restitution claims lodged under the Victims Law as of June 2013, and a large share of the threats reported to authorities. Victims of the abuses were reclaiming land through the Victims Law, as well as other restitution mechanisms, such as the Justice and Peace Law, and administrative processes handled by the INCODER rural development agency.

The report is based on in-depth research conducted between February 2012 and July 2013, including multiple fact-finding trips to Antioquia, Bolívar, Cesar, Córdoba, Sucre, Tolima, and Bogotá. In these locations, as well as by telephone, Human Rights Watch also conducted interviews with victims and/or state officials from Atlántico, Chocó, La Guajira, Meta, and Valle del Cauca departments. In 2009 and 2011, Human Rights Watch staff also made several field visits to communities along the Curvaradó River Basin, in Chocó department.

Human Rights Watch representatives interviewed more than 130 land restitution claimants and leaders, more than a third of whom were women. We also interviewed upwards of 120 local and national officials from a wide range of offices and institutions, including the Restitution Unit, Attorney General’s Office, National Police, army, Constitutional Court, National Protection Unit, Defense Ministry, Interior Ministry, Agricultural Ministry, Victims Unit, Ombudsman’s Office, and Inspector-General’s Office, among others. In addition, Human Rights Watch spoke with dozens of members of international organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and security and land experts. No interviewee received financial or other compensation in return for interviewing with us. Nearly all of the interviews were conducted in Spanish, with the sole exception of foreign staff at international organizations.

Many interviewees expressed fear of reprisals, and for that reason, requested to speak anonymously. Details about individuals have been withheld when Human Rights Watch considered that the information could place a person at risk, but are on file with the organization.

Human Rights Watch research drew on official statistics, which we sought through interviews and emails. We also received and reviewed a wide range of other sources and documents, including criminal complaints, court rulings, criminal case files, official and non-governmental reports, news articles, and books, among other forms of evidence.

Not all cases of abuses against land claimants and leaders documented by Human Rights Watch are detailed in this report. We use the term “documented” in reference to cases in which we have received a credible account from the victim—or their family members, friends, or fellow leaders in cases of killings or “disappearances.” Most cases are corroborated by a range of other sources, including interviews with public officials, witnesses, fellow leaders, community members, or international observers, criminal complaints, official reports, and news articles, among other sources.

IDP leaders advocating for land restitution are commonly involved in other overlapping activities that can also put their lives at risk, such as pursuing justice for conflict-related crimes or denouncing actions by armed groups. For this reason, it is often difficult to pinpoint the exact reason for which they were targeted. While this report documents cases in which Human Rights Watch found indicators that the threats or attacks were related to the victims’ land restitution efforts, in some cases it is possible that the abuses were motivated by their other related leadership activities, or a combination of the two.

Translations from the original Spanish to English are by Human Rights Watch.

I. Widespread Abuses against Land Restitution Claimants and Leaders

IDPs and their leaders seeking land restitution have faced widespread abuses, including threats, new incidents of forced displacement, and killings. The main perpetrators are paramilitary successor groups, third parties who took over and seek to keep IDPs’ land, and in some regions, FARC guerrillas. The abuses pose a major obstacle to effective implementation of the Victims Law.

Threats of Violence

Many IDPs and their leaders reclaiming land have been subject to criminal acts of intimidation and threats of violence.[1] Threatening displaced land claimants undermines restitution in many ways, including by making victims fearful, discouraging them from pursuing claims, restricting leaders’ participation in the process, and pushing those who have returned home to flee their land yet again.

Human Rights Watch documented credible threats against more than 80 IDP land claimants and leaders from Bogotá and eight other departments carried out since 2008.[2] These include more than 60 cases from between 2011 and 2013.

Government data shows that serious threats against claimants occur on a greater scale and throughout the country. Between January 2012 and May 2013, at least 510 land restitution claimants and leaders from 25 departments involved in various judicial and administrative processes—including the Victims Law—reported being threatened to the government’s National Protection Unit (UNP).[3] Based on individual evaluations, authorities found 363 of these threatened claimants and leaders to be at “extraordinary risk” due to their reclamation activities. This determination requires that the risk be, among other criteria, “concrete, founded in particular and manifest actions or events …, present, not remote or eventual …, important, meaning that it threatens to hurt legally-protected rights …, serious, of probable materialization because of the circumstances of the case …, [and] exceptional in the measure that it should not be endured by individuals in general.”[4]

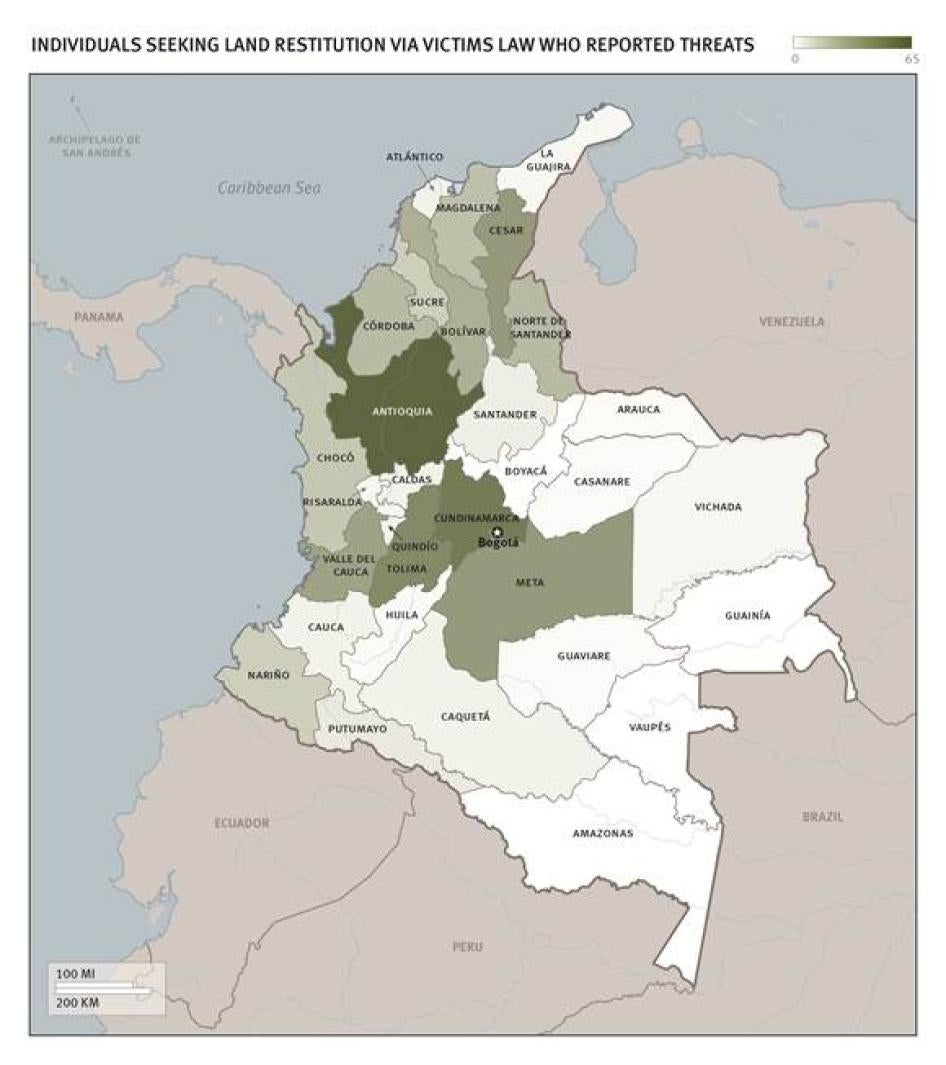

In terms of claimants and leaders reclaiming land through the Victims Law in particular—rather than other restitution mechanisms—447 from 27 departments have reported being threatened, according to the Restitution Unit.[5]

See Table. © 2013 Human Rights Watch

Table: Baseline Counts of Individuals Seeking Land Restitution who Reported Being Threatened by Department

|

Department |

Individuals Seeking Restitution via Victims Law who Reported Threats [6] (See Map) |

Individuals Seeking Restitution via Victims Law and other Restitution Mechanisms who Reported Threats [7] |

|

Antioquia |

65 [8] |

84 |

|

Arauca |

1 |

2 |

|

Atlántico |

3 |

13 |

|

Cundinamarca/Bogotá |

48 |

38 |

|

Bolívar |

22 |

54 |

|

Caldas |

3 |

1 |

|

Caquetá |

3 |

4 |

|

Casanare |

1 |

1 |

|

Cauca |

3 |

0 |

|

Cesar |

31 |

48 |

|

Chocó |

14 |

96 |

|

Córdoba |

18 |

24 |

|

Guaviare |

1 |

0 |

|

La Guajira |

2 |

2 |

|

Huila |

1 |

1 |

|

Magdalena |

16 |

28 |

|

Meta |

31 |

19 |

|

Nariño |

12 |

6 |

|

Norte de Santander |

18 |

18 |

|

Putumayo |

5 |

3 |

|

Quindío |

3 |

3 |

|

Risaralda |

2 |

3 |

|

Santander |

4 |

4 |

|

Sucre |

12 |

16 |

|

Tolima |

39 |

17 |

|

Valle del Cauca |

27 |

24 |

|

Vichada |

2 |

1 |

|

Unknown location |

54 |

0 |

|

Total |

447 |

510 |

Human Rights Watch found a consensus among government officials and victims interviewed for this report that threats pose a serious obstacle to implementing land restitution under the Victims Law. In March 2013, for example, Ricardo Sabogal, the national director of the Restitution Unit, stated that threats against claimants have been the most common way individuals have attempted to torpedo restitution cases.[9] On another occasion, Sabogal publicly identified such threats as one of the “principle challenges” to implementation of the law.[10] According to Alma Viviana Pérez, the director of the human rights program of the office of the president, “As soon as the wheels of land restitution turn, the threats arrive… Each time that you begin to implement the Victims Law, you find threats.”[11]

Often issued repeatedly against the same victim, threats are carried out in many ways, ranging from text messages and phone calls to verbal messages delivered in person. The content of the threats also varies: some threaten the victims or their family members with death, while others tell them to stop reclaiming land, to “keep quiet,” or to abandon the region where they are living. In some cases, the threats accuse the victims of being linked to guerrillas or paramilitaries.

One example of a threat delivered in person is the case of Angelica Zamora (pseudonym), an IDP leader from the Caribbean coast. Zamora reported to Human Rights Watch and prosecutors that a former congressman, who was since convicted for ties to the AUC, pressured her family to abandon their farm in the late 1990s and acquired it.[12] She filed a claim with the Restitution Unit in early 2012 and a few months later, two armed men on a motorbike stopped her on the street near her home and told her that if she continued with her case, she would not be able to finish it. Immediately after the threat, Zamora said she was hospitalized due to a rise in her blood pressure, and that out of fear, she restricts her movements and is afraid to sleep in her own home:

I’m afraid that they’re going to take the sheet roofing off [my home] and break in…. My freedom is over. I have to protect myself…. I don’t keep a schedule, or tell people [where I’m going]…. I feel like my every step is being followed.[13]

Multiple factors contribute to making the threats credible and terrifying. Land disputes are a major source of violence in Colombia and are widely identified as one of the root causes of the country’s armed conflict. Many victims of threats originally fled brutal abuses committed by paramilitaries and guerrillas—including against their family members—and often as part of a campaign to take over their land or control territory. Successors groups to these paramilitaries—or the exact same guerrilla group—frequently maintain a presence in the areas where the victims are reclaiming land. Successor groups in particular are known to have killed land claimants and leaders, including from the same region, community, or IDP association as the victim of the current threats. Victims often attribute the threats to these groups or other people involved in the long history of violence and land theft that has been committed against them.[14]

Many times, the threats are of such a grave nature that IDP land claimants and leaders decide to flee their homes, and confront yet again the myriad hardships of a new incident of forced displacement.

Forced Displacement

Threats, attacks, and other forms of intimidation against IDP land claimants and their leaders have caused many to flee their places of residence yet again. Human Rights Watch documented more than 30 such cases from seven departments since 2008.[15]

Official data indicates that land claimants and leaders must frequently abandon their homes due to imminent threats resulting from their restitution efforts. Between January 2012 and May 2013, the UNP temporarily relocated 94 land claimants and leaders to new areas because of grave risks to their lives.[16] As described by a UNP official, the program relocates individuals as a last resort, when:

[T]he only measure to preserve their lives is to remove them from the area of risk … when even if they are given a bodyguard or car [as protection measures], we cannot guarantee their security.[17]

The problem extends to the families of IDP land claimants and leaders. Human Rights Watch received credible reports of threats and other abuses against land claimants and leaders causing scores of their relatives to flee their homes, either separately or together with the direct victim of the abuse. For example, according to the Constitutional Court, the 2012 killings of land restitution leader Manuel Ruiz and his 15-year-old son Samir Ruiz, from the Curvaradó River Basin in Chocó, forcibly displaced 49 of their family members.[18]

These new incidents of displacement of IDP land claimants, leaders, and their relatives have a major impact on both the victims and broader restitution efforts. They often force the victims to again confront the economic and social hardships that arise from being removed from their homes, sources of income, and support networks. And when the few people who are willing to assume the risks of being leaders have to abandon the area due to threats, the community members they represent are left without a spokesperson, and observe firsthand the dangers of stepping forward to replace them. For example, in relation to the restitution process in Curvaradó, Chocó, the Ombudsman’s Office said the forced displacement of land restitution leaders and their families has “weaken[ed] the organizing processes because they imply the departure of leaders that play an important role in their communities,” and produced “situations of generalized fear and terror that restrict and discourage the community’s participation” in exercising their land rights.[19]

Many of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch—and reported by the UNP—in which IDP claimants and leaders fled their homes due to threats and other abuses tied to their reclamation efforts would constitute the crime of forced displacement under Colombian criminal law. While in some cases, evidence points to the responsibility of paramilitary successor groups or third parties, in others it was not possible to determine the perpetrator based on available information.

Regardless of the identity of the perpetrator, to cause someone to abandon his home through threats, violence, or other coercive acts would meet the definition of forced displacement in Colombia’s Penal Code:

He who in an arbitrary manner, through violence or other coercive acts directed against a sector of the population, causes one or various of its members to change their place of residence.[20]

Forced displacement is a crime whether or not it is committed in relation to Colombia’s armed conflict.

Furthermore, in June 2013, the Constitutional Court ordered the government to register as internally displaced and provide assistance, attention, and protection to people who flee their homes due to violence and abuses by paramilitary successor groups, irrespective of whether their displacement is caused by the armed conflict.[21]

The Constitutional Court also specifically recognized in a May 2013 order how threats against women IDP leaders have led to their forced displacement. Order 098 of 2013 affirmed that:

[T]hrough direct and indirect threats—pamphlets, emails, warnings written on public walls, among other [means]—[female leaders of IDPs] have been subjected to confinement in their own places of residence, villages or communities…. On occasion, given the high probability that the women or their family members will be attacked, they are compelled to abandon their place of residence either temporarily or permanently, which constitutes a new event of forced displacement.[22]

Killings, Attempted Killings, and Other Attacks

Human Rights Watch documented 21 cases of killings of IDP land claimants and their leaders committed since 2008 in the departments of Antioquia, Cesar, Chocó, Córdoba, and Sucre.[23] In 17 cases, evidence strongly suggests that the victims were targeted due to their efforts to reclaim land or similar activism. For example, many had received death threats related to their leadership prior to being killed. In four of the 21 cases of killings—as well as a fifth additional case in which a claimant was “disappeared”—it was not clear based on available information whether the attack was motivated by the victim’s land rights activities, though there is some evidence to infer that it may have been.[24] We also documented two cases of attempted killings and one kidnapping of a restitution leader since 2008 in which there are strong indicators that the victims were targeted due to their activism.

Reports by government authorities indicate that killings of land restitution claimants and leaders have occurred on a greater scale. Colombia’s Ombudsman’s Office reported at least 71 killings of land restitution leaders committed in 14 departments between 2006 and 2011.[25] For its part, the Attorney General’s Office reported in August 2013 that it was investigating 49 cases of killings of IDP land claimants and leaders committed in 16 departments since 2000.[26] Similarly, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court reported receiving information concerning the killings of at least 45 displaced leaders seeking land restitution between 2002 and 2011.[27]

Multiple family members and fellow activists of killed leaders told Human Rights Watch that the murders made them feel insecure in pushing forward with restitution claims. As described by the director of the UNP, the strategy of the perpetrators is to “kill a few people in order to send a message to many.”[28]

Despite the prevalence of threats against IDP land claimants and leaders, there have been relatively few killings of such individuals ultimately carried out since the Victims Law started to be implemented in January 2012.[29] While the cases in themselves are grave abuses with a significant impact on victims’ families, communities, and land restitution efforts, the relatively low number compared to the extensiveness of threats is likely due to a combination of factors. These include top government officials’ public condemnation of killings and protection measures the UNP provides to hundreds of threatened IDP claimants and leaders.

Furthermore, given that the Victims Law is a banner program of the Santos administration and receives a high level of political attention, it is reasonable to suspect that potential perpetrators believe that—unlike threats and more discrete forms of intimidation—violent attacks against claimants would put them in the national spotlight and increase their chances of being held accountable.

Perhaps the greatest reason, however, is that land restitution under the Victims Law remains in the initial stage of implementation.[30] As of June 2013, the Restitution Unit had obtained rulings ordering restitution for 1 percent of the claims it had received. By July 2013, just one family had returned to live on their land as a result of these rulings and with the support of the government office coordinating IDPs’ return home[31] (though many others were habitually visiting their land to farm it).[32] No rulings had been handed down for land in Urabá, one of the most dangerous regions for land restitution leaders and claimants.[33] (Cases of returns described in the report occurred outside of the Victims Law process.)

There are several reasons to expect that, as the restitution process progresses, the problem will get worse. Human Rights Watch found a consensus among a range of officials involved in land restitution that as cases advance, the level of risk for claimants escalates.[34] The UNP, for example, estimated in early 2013 that by the end of the year, it would need to provide protection measures to 1,000 participants in land restitution cases, more than double its coverage at the time.[35] Furthermore, of the cases of killings documented by Human Rights Watch, many of the victims had returned to their land or recently attempted to do so at the time of their death. This precedent—and the constant, grave threats currently being carried out against land claimants and leaders throughout the country—point to a latent risk of more killings as restitution claims advance and communities return home.

Perpetrators

Many of the people making threats … are the owners or supposed owners of the pieces of land that have been reclaimed…. There are other sectors. Sectors that I have called of the extreme left … and of the extreme right, who are linked to the old paramilitaries, who do not want the land they wrongfully appropriated to be taken away from them.

—President Juan Manuel Santos, Montería, Córdoba, July 7, 2012[36]

With a handful of exceptions, no suspects have been prosecuted for violence and threats against IDP land claimants, making it difficult to say with certainty who has been responsible. Nevertheless, compelling evidence reviewed by Human Rights Watch strongly suggests that paramilitary successor groups, third parties who acquired IDPs’ land, and, in certain areas, FARC guerrillas are the main actors responsible for the abuses. Regardless of the perpetrator, a common motive behind the abuses is to preserve control over a property or rural area from which the claimants had been displaced.

Paramilitary Successor Groups

Of the cases of abuses against land claimants and leaders documented by Human Rights Watch, there is compelling evidence that paramilitary successor groups carried out the majority of killings, attempted killings, and new incidents of forced displacement, as well as a significant portion of threats.

Successor groups’ roles in these crimes have ranged from issuing direct threats via flyers or phone calls to ordering or serving as triggermen in homicides. The Urabeños, Colombia’s largest and most powerful paramilitary successor organization, is the successor group most frequently suspected of carrying out the abuses in cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch. It has approximately 2,370 members and “a national command [structure] and cohesion,” according to police intelligence sources.[37]

Information provided to Human Rights Watch by a range of government offices points to a pattern of abuses by paramilitary successor groups against claimants. According to statistics compiled by the Restitution Unit, as of March 2013, 31 claimants and leaders from 10 departments reported threats attributed to the “Bacrim” and another 55 from 15 different departments attributed threats to demobilized members of the AUC—a common way that victims identify members of paramilitary successor groups[38] (though some demobilized paramilitaries may act independently in carrying out threats). Andrés Villamizar, the national director of the UNP, which provides protection measures to hundreds of IDP land claimants and leaders, said that paramilitary successor groups were largely responsible for threats against them on the Atlantic Coast.[39]

Similarly, an Attorney General’s Office official monitoring investigations into criminal complaints of threats against land restitution claimants and leaders throughout the country said that successor groups were the principal perpetrators.[40] The Ombudsman’s Office has also repeatedly reported threats and violence by paramilitary successor groups against IDPs seeking restitution.[41]

Furthermore, the government-created Center for Historical Memory concluded in its final report on the armed conflict that paramilitary successor groups are “one of the principal challenges” to implementation of the Victims Law, finding:

The policy of land restitution became an open challenge by institutions to the rearmed paramilitary powers, which is why they respond with an escalation in violence, in particular against land claimants.[42]

Internationally, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR), UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial executions, and the Organization of the American States’ Mission to Support the Peace Process in Colombia (MAPP-OEA) have all reported that successor groups target land restitution claimants.[43] In 2013, for example, the UNHCHR affirmed:

Attacks and threats continued against human rights defenders and those involved in the land restitution programme. In many areas, the majority of these violations can be attributed to illegal armed groups that emerged after the demobilization of paramilitary organizations (postdemobilization groups).[44]

Continuity between the AUC and Successor Groups

One major reason why paramilitary successor groups would have a vested interest in targeting land restitution claimants and leaders is that in many areas, these groups took over the criminal operations of the demobilized AUC paramilitary coalition responsible for widespread forced displacement and land grabs during the height of the armed conflict.

Though different in important respects from the AUC, paramilitary successor groups have taken on many of the same roles—engaging in drug trafficking and other mafia-like criminal activities, as well as abusing civilians who oppose their interests—often with some of the same personnel and in the same areas.[45] Colombia’s high commissioner for reintegration estimated in 2011 that half of the leaders of paramilitary successor groups were former mid-level AUC commanders.[46] Of the 12 top paramilitary successor group leaders the police reported having captured between January and October 2012, more than half were former paramilitaries.[47]

This proportion may have since diminished due to the police’s capture of dozens of successor groups’ leaders and the fragmentation of some groups, such as the Rastrojos.[48] Still, continuity in personnel between the AUC and paramilitary successor groups persists.[49] One prime example is the current top commander of the Urabeños, former AUC member Dairo Antonio Úsuga, whose alias is Otoniel.[50]Otoniel inherited the Urabeños criminal enterprise from a long line of arrested, demobilized, or killed paramilitary commanders dating back to Freddy Rendón Herrera, alias El Alemán, and AUC founder Carlos Castaño, whose forces perpetrated widespread land theft in alliance with public security forces, politicians, and local economic elites in the 1990s and early 2000s.[51]

Many public officials recognize the close connection between paramilitary successor groups and the AUC.[52] For example, prosecutors investigating successor groups in Urabá and Córdoba told Human Rights Watch that there is “no difference” between them and the AUC and that they “only changed their name.”[53] Similarly, the head of the Personería—a municipal human rights entity—in Montería, Córdoba stated in 2013 that paramilitary successor groups are:

[t]he prolongation of an armed actor that used to be called paramilitarism. These bands operate in the same territories where the [AUC] once had control, where the violations of human rights are systematic and widespread.[54]

Even the US Department of Justice has recognized the continuity between the AUC and paramilitary successor groups: a 2009 indictment against several Urabeños leaders—including Otoniel—on drug trafficking and terrorism-related charges refers to the successor group as a bloc of the AUC.[55]

A textbook example can be found in two courts’ decisions convicting Urabeños members for the March 23, 2011 killing of Urabá land restitution leader David de Jesús Góez Rodríguez.[56] Góez had led restitution efforts in the area of Tulapas, where the AUC had carried out widespread land theft.[57] The Attorney General’s Office found that prior to his death, as part of his land activism, Góez had publicly denounced the Urabeños, who, according to the prosecutor:

[C]ontinued subjugating peasants and refusing to hand over the valuable land in the region of Tulipa (sic), [which] is a corridor for trafficking drugs to the Atlantic Ocean.[58]

Prosecutors also determined that Góez’s killing was ordered by then-top Urabeños commander Juan de Dios Úsuga David (the brother of Otoniel), alias Giovanni, who was a former AUC member.[59]Giovanni ordered the killing because he suspected that Góez had provided information to authorities that led to the 2009 arrest of then-top Urabeños commander Daniel Rendón Herrera, alias Don Mario, also an ex-AUC member who, according to prosecutors, had “inherited the whole structure of narcotrafficking and [p]aramilitarism.”[60]

The Urabeños’s influence in the Tulapas region remains an obstacle to land restitution: Manuel Mercado, a fellow leader of Góez’s from Tulapas, told Human Rights Watch that since being awarded restitution in a November 2011 court ruling, he has not returned to live there because the Urabeños have forbidden him from doing so.[61] In April 2013, Mercado guided the Restitution Unit in placing notifications of restitution claims to parcels of land in Tulapas, but despite being escorted by the police, they were unable to complete the mission due to the Urabeños’s strong presence in the area, and because the group was following Mercado and the Restitution Unit’s movements.[62] Mercado believes the paramilitary successor group is opposed to his return to Tulapas because of his collaboration with authorities. Indeed, evidence suggests that successor groups sometimes target restitution leaders because of their frequent interaction with authorities, which is a key part of their activism.

Third Parties

People who took over IDPs’ land following their displacement are a principal source of abuses, according to cases documented by Human Rights Watch and interviews with an array of officials. These third parties range from paramilitary front men—who have held and hidden the AUC’s assets—to cattle ranchers, politicians, landowners, businesspersons, and demobilized paramilitaries.

Human Rights Watch documented multiple cases in which evidence suggests that third parties who occupied or disputed land subject to restitution claims threatened or intimidated IDP claimants. Top public officials similarly identified third parties occupying the reclaimed land as principal perpetrators of threats. According to Ricardo Sabogal, the national director of the Restitution Unit, “The information provided by the victims is that the ones who threaten them are those who are occupying the piece of land—the one who stole or bought the land.”[63] Similarly, María Paulina Riveros, the director of the Interior Ministry’s human rights program, told Human Rights Watch:

More than anything the authors of the threats are the ones who took over the land—the people who are interested in keeping the land.[64]

Data compiled by the Restitution Unit also indicates that these third parties are often responsible for the threats against claimants. As of March 2013, 148 land claimants or leaders from 21 departments seeking restitution through the Victims Law had reported threats that they attributed to perpetrators categorized by the Restitution Unit as “individual agents.”[65] According to a Restitution Unit official, most of the cases classified this way refer to people who are occupying the reclaimed land, but do not fit the other categories of perpetrators included in the unit’s data (Bacrim, demobilized AUC members, guerrilla, other criminal groups, and “to be established”).[66]

While third parties have sometimes threatened and intimidated claimants directly, a range of evidence—including interviews with victims and officials, as well as government documents—suggests they have also done so through others, such as farm workers or administrators, henchmen, private security workers, or paramilitary successor groups.

Collaboration between Third Parties and Successor Groups

Human Rights Watch interviews with victims, their family members, and a range of officials, as well as our review of Ombudsman Office reports and criminal complaints, strongly suggest that successor groups have at times threatened or killed IDP land claimants and leaders on behalf of third parties seeking to hold on to land.

For example, in threatening and intimidating claimants and leaders from the communities of Curvaradó and Jiguamiandó in Chocó department, paramilitary successor groups have acted on behalf of landowners, ranchers, and businesspersons occupying their land, according to the Ombudsman’s Office,[67] local and national officials, and victims (see more on the Curvaradó and Jiguamiandó case in the section, “Curvaradó and Jiguamiandó Communities, Chocó Department”).[68] One Afro-Colombian leader from the region who has participated in the Curvaradó and Jiguamiandó restitution process told Human Rights Watch that in 2009, he went to a meeting with businesspersons in which a known paramilitary was present. A businessman offered the Afro-Colombian leader money in exchange for helping to evict one of the Curvaradó communities that had returned, and the paramilitary pressured him to accept the offer, he said.[69]

Numerous judicial, government, and academic investigations show that in displacing Colombians, AUC paramilitaries operated as part of a vast network of accomplices that included public security forces, politicians, ranchers, businesspersons, public officials, and drug traffickers.[70] Some of these sectors acquired IDPs’ land, either in direct conspiracy with the AUC or by taking advantage of paramilitary violence and appropriating the land from which IDPs had fled. For example, the Restitution Unit has found with regard to widespread usurpation of land by top paramilitary leaders Fidel, Carlos, and Vicente Castaño that:

[T]he interest in appropriating land was not only a priority of the paramilitary bosses but also its associates (politicians, businessmen, and drug traffickers) who found in these actions a source of wealth.[71]

The AUC demobilization process failed to dismantle these networks,[72] and swaths of land they amassed remained in the hands of paramilitary front men—who hold and hide AUC assets—demobilized paramilitaries, landowners, ranchers, and a range of other third parties. There are strong reasons to believe that some of these people maintain ties with paramilitary successor groups. A national police intelligence official, for example, told Human Rights Watch that in Urabá, Córdoba, Sucre, and the eastern plains regions, some cattle ranchers support successor groups.[73] Similarly, then-National Police Director Oscar Naranjo told El Tiempo newspaper in February 2012 that the Urabeños’s “force is rooted [in the fact that] there are sectors who want to maintain this intimidating figure, to protect their mafia interests.”[74] According to the same news report:

Reports in the hands of authorities signal that, as it happened in the 90s with paramilitary blocs … there are cattle ranchers, merchants, politicians, members of the security forces and businessmen interested in sponsoring the violence of the Urabeños. El Tiempo saw an intelligence report that documents how the sectors that [General] Naranjo talks about look to take advantage of the [Urabeños] to boycott the restitution of land to victims of the violence. They have even financed the printing and distribution of threatening pamphlets.[75]

In the same vein, Eduardo Pizarro, former director of National Commission for Reparations and Reconciliation (CNRR) established by the Justice and Peace paramilitary demobilization law, stated with regard to violence against land claimants:

It’s possible that regionally links subsist between state agents, businessmen, politicians, and the [Bacrim].… [The Bacrim] are instruments of the regional criminal elite for impeding victims from fighting for the restitution of land.[76]

Nevertheless, by no means are there always links between the third parties responsible for threats and paramilitaries or their successor groups.

Anti-Restitution Army

Since the passage of the Victims Law, IDP land claimants and their advocates in different areas of Colombia—as well as journalists reporting on the restitution process—have received threats signed by a self-proclaimed “Anti-Restitution Army.” Human Rights Watch documented multiple threats of this kind in the departments of Bolívar, Cesar, and Sucre.

On July 4, 2012, for example, an email sent from an account identified as the “Anti-Restitution Army” threatened to kill various human rights activists and politicians, including Congressman Iván Cepeda Castro and lawyer Jeison Paba, who have advocated for victims in land restitution cases in Sucre and Bolívar.[77] The threat stated that there were clear instructions to kill those targeted in the message “who want to take away land from good citizens to give it to guerrillas just like them.”[78]

More recently, on May 6 and 7, 2013, unknown people distributed threatening flyers signed by the “Anti-Restitution of Land Group of the Caribbean Coast” at the offices of news outlets in Valledupar, Cesar department. The threat declared eight journalists—some of whom had covered the land restitution process in Cesar department—as “military targets” and said that they “have 24 hours to leave the city[. I]t should be clear that if you keep sticking your nose in cases of land restitution…you will be the next [victims].”[79]

National and department-level authorities said they had not found any evidence of the existence of an “Anti-Restitution Army” group.[80] Human Rights Watch was not able to confirm the existence of an organized armed structure known as the “Anti-Restitution Army.” But, Human Rights Watch did receive credible reports that partially corroborate allegations made by Nuevo Arco Iris, a prominent Colombian think tank, which first denounced the formation of a “private army” opposing land restitution.

Nuevo Arco Iris stated that three meetings took place in Cesar department in early 2011 and 2012, in which ranchers, landowners, and other regional elites agreed to fund a “private army” to defend themselves against FARC attacks and thwart land restitution.[81] The three meetings took place near Becerril, Cesar on December 17, 2011; in Cascará, Cesar on January 13, 2012; and near Valledupar on February 4, 2012, and were also attended by demobilized paramilitaries, according to Nuevo Arco Iris.[82]

While unable to confirm whether any plans were made to create an armed group during these meetings, Human Rights Watch received reports from two other credible sources indicating that three meetings took place in Cesar department in which participants planned opposition to land restitution. Ombudsman’s Office documents, for example, stated that the office received information from land restitution leaders about meetings between landowners, ranchers, and others held in the same locations and time periods as those denounced by Nuevo Arco Iris, in which “the central issue of the meetings has been the discussion of strategies of all kinds to oppose the mobilization of peasants in favor of land restitution.”[83]

Whether or not an armed group called the “Anti-Restitution Army” exists, it is clear that in different regions, the name is being used in threats aimed at instilling fear among those involved in the land restitution process.

Guerrillas

Guerrilla groups have also carried out abuses against IDP land claimants and leaders. Human Rights Watch documented various cases of IDP leaders from Tolima department who reported being subject to repeated threats by the FARC’s 21st Front due to their efforts advocating for the return of IDPs to their farms in southern Tolima. Several IDP leaders told Human Rights Watch and judicial authorities that the FARC have held meetings in rural areas of southern Tolima—a traditional guerrilla stronghold—and declared its intention to kill IDPs and their leaders who attempt to return to their land.