“They Are Killing Us”

Abuses Against Civilians in South Sudan’s Pibor County

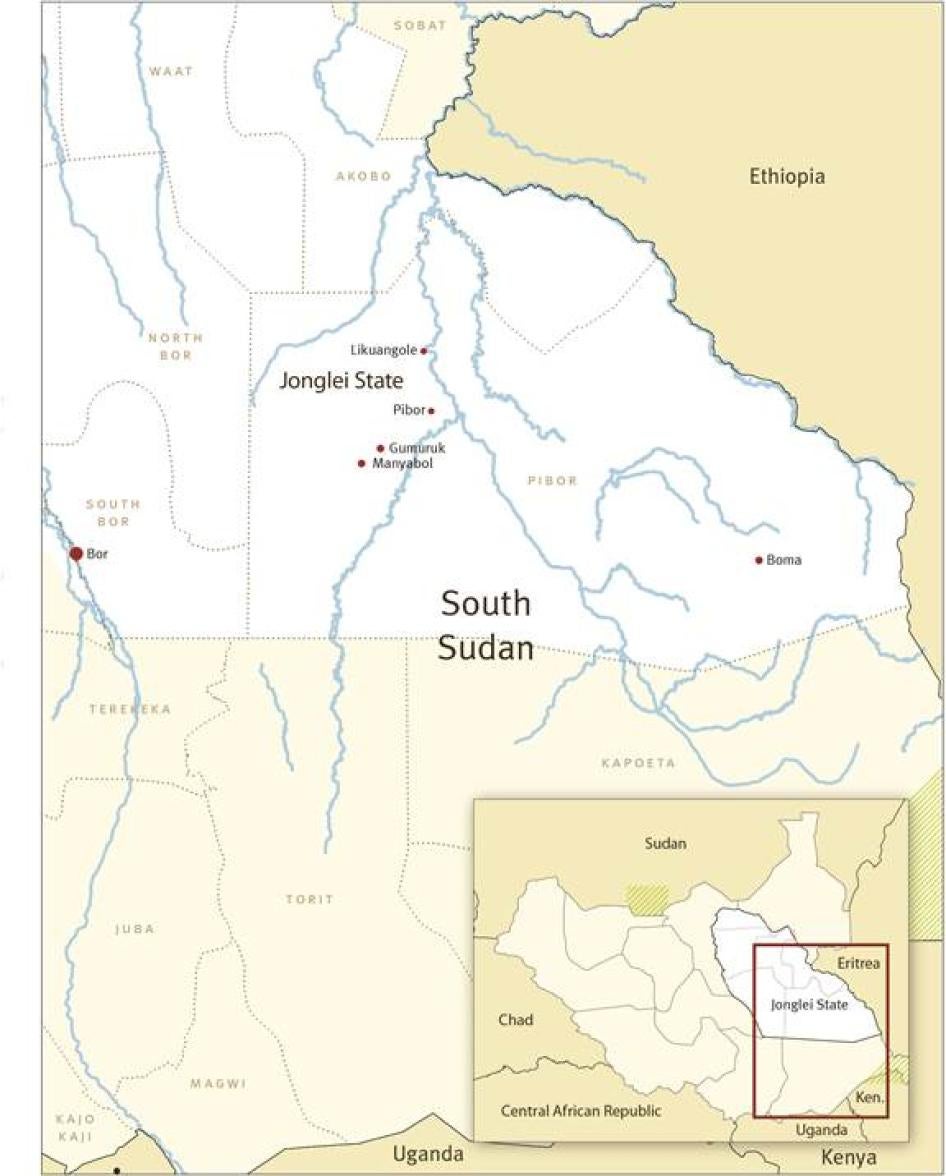

Map of South Sudan

Summary

Since December 2012, the South Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), South Sudan’s army, locked in a conflict with ethnic Murle rebels from the South Sudan Democratic Movement/Army (SSDM/A), has committed serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. SPLA soldiers have unlawfully killed at least 96 people, mostly civilians, from the Murle ethnic group during the conflict, and they have engaged in widespread looting of homes, clinics, schools and churches. The abuses by SPLA solders have had a devastating and potentially long-lasting impact on this marginalized minority ethnic group from Pibor county and have caused widespread fear and displacement, contributing to a strongly held perception of persecution among the Murle civilian population.

The abuses have taken place against a background of ethnic conflict. Dinka Bor, Lou Nuer and Murle ethnic groups, all in Jonglei State, have been locked in a cycle of cattle raiding attacks and increasingly brutal revenge attacks for several years. The rebellion and the SPLA counter-offensive have further aggravated pre-existing ethnic tensions in the area, which in the case of anti-Murle sentiment may have played into the extent of the abuses and the slow government response.

On August 20, SPLA announced that its commander stationed in Pibor town since April 2013 had been arrested and placed in military detention in South Sudan’s capital Juba awaiting trial by court martial. While charges against him have not been publicly confirmed, military officials told Human Rights Watch that he was arrested for being in command during a period in which soldiers committed human rights abuses and crimes including killings of civilians, cattle raiding and looting. The SPLA have conducted investigations into some abuses by soldiers and at least two other soldiers have been court martialed for civilian killings. The investigations and arrests are positive steps, and should be followed by a full investigation and prosecution into all incidents described in this report.

The potential for further grave violations and violence is very high, in part because the SPLA—an army still in transition—faces significant command and control and discipline challenges but also because ethnic tensions are so high in Jonglei, especially anti-Murle sentiment. During Sudan’s long civil war, the Sudanese government armed southern ethnic militias to fight against southern rebels, exacerbating ethnic differences. A Murle militia was one of several absorbed into the SPLA well ahead of the South’s separation in July 2011. However Sudan is still accused by the government of South Sudan of supplying weapons to new rebel groups in Jonglei, including the SSDM/A, inflaming old suspicions and anger.

Authorities from Jonglei and others have expressed their perception, that Murle fighters are especially aggressive and problematic. Human Rights Watch has frequently heard Murle fighters faulted by authorities from other parts of Jonglei for failing to hand over weapons to state security services during disarmament efforts. Critics have said communities from areas surrounding Pibor county feel victimized by the frequency of Murle attacks and because Murle raiders allegedly abduct children more often than other ethnic fighters. The government has tolerated or ignored incendiary hate speech, especially against the Murle, by other ethnic groups.

Inter-ethnic violence between the Lou Nuer, Dinka and Murle communities has killed thousands of people in recent years. The government of South Sudan has failed to prevent this violence, despite frequent warnings of impending attacks, protect civilians, or hold accountable those responsible for these attacks.

In early July, 2013, in response to Murle attacks on their home areas, thousands of Lou Nuer fighters massed and attacked Murle areas. As of the time of writing, the full extent of the attack is still not known. Murle, displaced by the conflict and by SPLA abuses may have been especially vulnerable to the attack. Allegations of government support including the provision of ammunition to the Lou Nuer, reported by credible sources heard by Human Rights Watch, have further deepened Murle perceptions of government persecution, and should be urgently investigated.

The government’s primary response to inter-ethnic fighting has been to launch disarmament campaigns, which were particularly abusive in Pibor county in 2012 when many Murle armed men refused to hand in weapons. The government’s failure to meaningfully redress abuses by SPLA during the disarmament paved the way for further abuses by soldiers in late 2012 and 2013.

Focusing on the nature and extent of the SPLA’s violations against Murle civilians between December 2012 and July 2013, this report documents how the conflict and serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law have played a significant role in causing the majority of the Murle population to flee to remote areas of the bush, many of them believed to be cut off from access to emergency food and medical aid.

Many of the abuses documented by Human Rights Watch are serious violations of international humanitarian law and require those responsible be held accountable. Fundamental to international humanitarian law, which applies to this armed conflict between the SSDM/A and the SPLA in South Sudan, is the principle that parties to a conflict must distinguish between combatants and civilians and may not deliberately target civilians or civilian objects. International humanitarian law also prohibits collective punishment, that is, punitive acts carried out against the civilian population in retaliation for the actions of others, and deems them to be war crimes.

Tens of thousands of Murle are now displaced including most of the civilians from all six main population centers in Pibor county, now little more than barracks, and are too frightened to return. A failure by South Sudan’s government and army to stop these abuses and provide accountability and redress for the abuses could cause long-term displacement.

Like other populations in South Sudan, still recovering from years of war, Murle communities have access to very few essential services such as education and health, and face food insecurity. Murle rebels and the SPLA have raided and destroyed facilities belonging to providers of emergency health care and food aid, in violation of the prohibition on the destruction of objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population. Evidence strongly indicates that SPLA soldiers were responsible for the majority of the looting and destruction in two key towns in May. Soldiers have also occupied and destroyed schools.

The Murle rebel group, the SSDM/A led by David Yau Yau, has also attacked SPLA locations in towns and killed and abducted civilians. Some of these acts may constitute war crimes and should be investigated further. Human Rights Watch has also heard allegations that Murle attacks by fighters armed by Yau Yau on other ethnic groups including outside of Pibor county have caused many deaths. Many Murle told Human Rights Watch that Yau Yau’s rebellion and the ensuing conflict have brought intense suffering on their communities. Yau Yau has refused an amnesty offer by the government.

The SPLA should remove abusive soldiers from Pibor county and hold them to account. Findings from investigations should be made public. The government and army leadership should ensure a fundamental change in the way soldiers interact with civilians. The SPLA should invest more resources into ensuring its soldiers understand their obligations under the SPLA Code of Conduct and ensure that military justice personnel are able to function effectively, especially in conflict areas.

Impunity for those involved in inter-ethnic attacks should end and criminals, especially ringleaders, should be arrested and prosecuted.

To stem further abuses and ethnic bloodshed, South

Sudan’s government should also ensure a full, neutral investigation into ethnic

violence in Jonglei takes place. International experts from the AU or UN should

be included in the investigation team. It should examine why inter-ethnic

conflict has worsened in recent years, and investigate accusations of

government support to fighters, and bias in efforts by security forces to

protect civilians. The government should also plan for more extensive and

even-handed community protection by state security forces.

Recommendations

To the Government of South Sudan:

Regarding SPLA Abuses

- Urgently investigate all abuses by soldiers from South Sudan (SPLA) in Pibor County and hold abusive soldiers to account; deploy judge advocates and military police to all locations where SPLA is stationed in order to deter further abuses and deploy civilian prosecutors and judges to hear cases on abuses against civilians, as required under South Sudanese law. Judge advocates and investigators should be provided with transport and all other necessary support to conduct their work in a timely manner.

- Move soldiers and commanders alleged to have committed abuses out of Pibor county and discipline or prosecute those responsible as appropriate in light of the nature of the abuse and scope of criminal responsibility.

- Commanders should consult with communities and civilian leadership in Pibor County on measures that can be taken to ensure civilian safety, including from further SPLA abuses, and address the distrust that exists within the Murle civilian population against SPLA. Efforts may include not barracking soldiers in town centers, appointing community liaison officers and helping rebuild infrastructure destroyed during fighting.

- The SPLA should urgently ensure that all soldiers, but especially those in conflict areas, understand their obligations under international humanitarian law and have been trained in the SPLA Code of Conduct. Command responsibility for ensuring full understanding of obligations by soldiers and for taking steps to prevent and punish violations, should be enforced and commanders who fail to report abuses by soldiers in a timely manner should face punitive action. All training and other awareness raising efforts should be designed to account for high levels of illiteracy in the army.

Regarding Inter-ethnic Attacks

- Issue a strong condemnation by the president of South Sudan of ethnic attacks perpetrated by any and all groups;

- Ensure the arrest and prosecution of those involved in inter-ethnic conflict, focusing priority on identifying and holding ringleaders to account.

- Commence an independent and comprehensive investigation into violence in Jonglei. The investigation should examine the increase in inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei, allegations of the involvement of government officials and bias in government and SPLA efforts to protect civilians. The investigation should also examine what efforts were taken to protect civilians from violence. International experts, for example from the United Nations or the African Union, should assist in the investigation and in the implementation of recommendations.

- Develop a clear strategy for preventing and protecting communities from inter-ethnic violence.

To the United Nations Mission in South Sudan:

- UNMISS should fulfill its mandate to protect civilians in South Sudan and help curb any future violence against civilians by ensuring that peacekeepers are deployed in larger numbers to Jonglei, especially Pibor County, and are patrolling extensively, including within and beyond towns and on long range patrols. The mission should establish additional operating bases outside of Pibor and Gumuruk towns in order to expand patrols to remote areas.

- UNMISS should ensure troops are appropriately equipped and supported, and, consistent with its mandate, willing to use military force to protect civilians under imminent threat of harm including by SPLA soldiers.

- UNMISS peacekeepers should improve relations with the local communities by patrolling with language assistants and community liaison officers, and should ensure civilians may safely bring complaints or allegations of abuses from either party to the conflict to the mission.

- UNMISS should bolster support to the police and other rule of law institutions, including prosecutors, judges and courts. These efforts should aim to demilitarize law enforcement in Pibor County.

- UNMISS human rights officers should investigate all allegations of abuse, and assist victims of abuse to lodge complaints with relevant officials. UNMISS should also support the SPLA’s military justice division in Pibor County, including by monitoring all cases involving civilians.

- UNMISS should deploy an adequate number of human rights officers to Pibor county to fully monitor the situation to help curb abuses. UNMISS should commit to timely, public reporting on human rights abuses across South Sudan, including any abuses by South Sudanese soldiers or other armed actors.

- UNMISS should ensure strict compliance with the Human rights due diligence policy on United Nations support to non-United Nations security forces (HRDDP) to ensure the UN does not provide any type of support to potentially abusive South Sudanese forces.

To the United Nations Security Council:

- Call on South Sudan to ensure accountability and redress for abuses by the soldiers in Pibor county and end abusive tactics in South Sudan’s counterinsurgency efforts.

- Call on South Sudan to order an investigation into the 2013 inter-ethnic attacks and counter-attacks in Jonglei state and to issue a public report and ensure criminals are prosecuted.

- Support UNMISS and the Department of Peacekeeping Operations to provide the additional military helicopters and surveillance drones as requested. These should be used in strict compliance with the HRDDP.

- Call on troop contributing countries to provide properly functioning equipment to their troops so bases function well and soldiers are ready to respond and protect civilians.

Methodology

This report is based on two research trips to South Sudan’s Central Equatoria and Jonglei states between June and August 2013. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 50 Murle (30 women and 20 men) in Juba who had been displaced either by the conflict or by soldiers’ abuses. Murle victims of abuses by the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) and South Sudan’s auxiliary police were also interviewed in Gumuruk town.

Most Murle interviewed by Human Rights Watch were from Pibor’s towns, as insecurity and poor road conditions during the rainy season limited the areas Human Rights Watch could access. Interviews with a wider range of members of the Murle community outside the towns might have uncovered more abuses by both parties to the conflict.

This research focuses on abuses by members of South Sudan’s army, the SPLA between December 2012 and July 2013, with inter-ethnic violence as a secondary focus, central to understanding the context of the SPLA abuses. Human Rights Watch documented five killings by the rebel group, South Sudan Democratic Movement/Army, and also received allegations of other killings, looting, abductions of three civil servants and seven chiefs and that rebel attacks, including shelling, on towns may not have discriminated between military objectives and civilians.

These allegations are extremely serious and require further research.

Murle community leaders and members of civil society helped identify victims and witnesses. Interviews with victims and eyewitnesses were conducted confidentially, mostly in homes, and in English, Murle and Arabic, with assistance from translators where necessary. Most interviews lasted 15 to 30 minutes and with the exception of one telephone interview all took place in person. All interviewees gave consent. No incentives were provided to interviewees who were informed they could stop the interview at any time or choose not to answer any question.

Researchers also interviewed 15 government officials from Jonglei state in Gumuruk, Bor and Juba, national level government officials in Juba, and officials from South Sudan’s army including the SPLA spokesman and members of the military justice division in the SPLA’s General Headquarters. Ahead of publishing this report, Human Rights Watch shared information about SPLA killings and other abuses with the SPLA’s Chief of General Staff, Gen. James Hoth Mai. A response was requested. Human Rights Watch did not receive a written response but SPLA officials shared information about action already taken in interviews with Human Rights Watch, included in this report.

Researchers also spoke to staff of United Nations agencies, independent international aid groups and staff from the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) in three locations and conducted subsequent interviews by e-mail and telephone.

Members of the Murle community told Human Rights Watch that they feel persecuted by the government and could be at risk of reprisals if their contribution to our research became known. For this reason Human Rights Watch has not used any names of victims and has withheld other identifying information.

I. Background

Failure to Address Recurring Inter-ethnic Violence

Pibor is the largest county in South Sudan’s largest state, Jonglei, and one of the least accessible areas of South Sudan. Pibor County has few roads, and those that exist are mostly impassable during the rainy season. In this wild land, violence and impunity for violent crimes have become the norm.

Jonglei’s Murle, Dinka Bor and Lou Nuer ethnic groups have been locked in a bloody cycle of cattle raiding and revenge attacks for generations, but since 2009 the pattern of cyclical dry season ethnic conflict has worsened. Devastating attacks and counter attacks increasingly target women and children, including in villages, rather than just cattle camps. [1]

The government of South Sudan has repeatedly failed to prevent the outbreak of inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei in which civilians have been harmed or hold criminals, including the ringleaders of mass attacks, to account. Allegations that soldiers, police and government officials have been involved in violent inter-ethnic attacks have not been investigated. [2] Sometimes the government has deployed the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) or other security forces to intervene in fighting and protect communities but often they have not, angering communities. [3]

In late 2011, despite being informed of an impending attack, neither the government nor UN peacekeepers halted a massive attack by some 6,000 armed Lou Nuer on Murle areas. The attack, which was preceded by brutal Murle attacks on Lou areas between July and August 2011, resulted in at least 612 Murle killed. [4] Over 270 Bor Dinka and Lou Nuer were killed in revenge attacks by Murle in late December 2011 and early 2012.

An All-Jonglei Peace Conference held in early May 2012 called for perpetrators of violence to be brought to justice. But the government has not investigated the ethnic violence or taken steps to prosecute those responsible for the massive attacks. Rather than ensuring accountability for the crimes in 2012, the government delayed the swearing in of seven members of an investigation committeeto investigate the violence, and failed to provide it with funding so it could function[5] The committee never began its work.

Inter-ethnic conflict has continued between the three groups. Research by UNMISS found that in February 2013 an attack, widely presumed to have been by Murle fighters, on Lou Nuer in Walgak, Akobo West sub-county, killed at least 85 people. [6] This and other Murle attacks have been cited by Lou Nuer fighters as the reason why, between July 4 and 13, 2013, they conducted a large-scale attack on Pibor County, including on a SSDM /A camp. The full extent of the attack is not known but Murle leaders have said that that 328 people from 16 villages were killed by the Lou Nuer. [7]

The government’s most vigorous response to inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei has been a series of sometimes brutal community disarmament efforts. In March 2012 the SPLA started “Operation Restore Peace” during which soldiers committed serious human rights violations, including beatings, rape and torture in Pibor County. [8]

The SPLA’s abuses generated resentment among Murle, which in turn encouraged support to a Murle rebel leader, David Yau Yau who started his first rebellion against the government in 2010 after he failed to win a parliamentary seat in elections that year.

David Yau Yau’s 2012 Rebellion and South Sudan’s Counterinsurgency

Yau Yau’s first rebellion ended in June 2011 when he agreed to an amnesty offer and the integration of himself and his forces into the SPLA. But in August 2012, Yau Yau defected and again took up arms against the government. Yau Yau’s second rebellion has been far more significant, in terms of the number of fighters he claims to command, the number of clashes, and their impact on the Murle population.

Yau Yau reappeared in Pibor County in August 2012 with a small group of about 50 men. Since then an estimated 4,000-6,000 largely Murle youths, looking for weapons but also revenge against the government for abuses committed during the disarmament, have either joined Yau Yau or have been armed by him. [9] Exactly how many of these fighters are directly under his control remains unclear. South Sudan’s government has said that Yau Yau receives military support from Sudanese sources looking to destabilize South Sudan, widely believed to be true. [10]

On August 21, 2012, when South Sudan’s army was still in the midst of the “Operation Restore Peace,” disarmament campaign, Yau Yau’s forces ambushed SPLA forces, leaving 102 SPLA soldiers dead. Yau Yau’s forces attacked SPLA positions over the following months including in the largely Murle towns of Likuangole, Pibor, Gumuruk and Manyabol causing mass displacement. The SSDM/A issued a statement in early May, 2013, saying they had captured Boma town. [11] The SPLA recaptured the town on May 19, 2013. Not all the fighting has taken place in towns; SPLA have also made offensives into SSDM/A held rural areas.

The fighting displaced tens of thousands of civilians in the latter part of 2012. In August, fighting in Likuangole town forced 10,000 people to flee. [12] Many of the displaced ran to Pibor town, around 30 kilometers away. In September fighting in the town of Gumuruk pushed at least 8,000 residents to Pibor town. [13] In mid-November, fighting in Pibor town displaced 10,000 people from their homes. [14]

Peacemaking efforts are ongoing. The Government of South Sudan has supported Murle leadership and other mediators to persuade Yau Yau to end his insurgency.[15] South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir has, as recently as July, said the amnesty offer for Yau Yau initially made on April 24, 2013, is still open. To date, and to the frustration of many Southern Sudanese, Yau Yau has declined the offer.

An Environment Ripe for Abuse

The counterinsurgency in Pibor county has taken place in an environment ripe for abuse. A former rebel army still struggling with restructuring into a national army, the SPLA has also absorbed thousands of armed militias in the past five years whose soldiers also lack training. Illiteracy is high and conditions for soldiers in Pibor county are poor. [16] Deficient command and control is a pervasive problem and abuses by soldiers have been reported across South Sudan. [17]

These factors likely played a role in the number and severity of abuses committed against Murle civilians. The complex history of violence in Jonglei, including inter-ethnic violence, and anti-Murle sentiment may have also contributed to the frequency of SPLA targeting of civilians.

Ethnic tensions between Murle and other ethnic groups were heightened by years of conflict and suspicion fuelled by shifting allegiances at the time of the Sudanese civil war, during which Khartoum supported a Murle militia that fought the SPLA. The emergence of a new apparently Khartoum-supported Murle armed group has angered many. Murle leaders have admitted that large numbers of young Murle men joined or were armed by Yau Yau including from South Sudan’s army, police and wildlife services. This has made SPLA soldiers “paranoid about all Murle.” [18]

Politicians acknowledge that all actors are partly to blame in inter-ethnic fighting in Jonglei State but Human Rights Watch has often heard the Murle being singled out as especially problematic, ungovernable and aggressive by members of other ethnic groups. Politicians have expressed exasperation at large numbers of Murle attacks, Murle refusal to disarm and say child abduction is frequent.

Human Rights Watch has heard from several sources, including senior government officials, on various occasions since 2008, derogatory comments about the Murle as an ethnic group by government officials. UNMISS human rights officers recorded instances of hate speech, including threats of annihilation, made by Lou Nuer fighters about Murle in 2012 and by Nuer diaspora groups.[19] Although incitement to hatred or violence is illegal in South Sudan, overall no action has been taken in response to such speech. The President only very recently called for an end to derogatory and hate speech. [20]

Human Rights Watch was unable to find an ethnic breakdown of South Sudan’s national army in Pibor County but was informed by various sources, including government, SPLA, and UN sources that high numbers of Nuer, including from former Nuer militias, have been stationed there. Two commanders whose forces are alleged to have committed many of the serious abuses that Human Rights Watch documented, Brigadier Peter Ruach and Brigadier James Otong, are both from the Nuer ethnic group. [21] Murle victims of looting or physical or verbal abuse by soldiers often said in interviews with Human Rights Watch that perpetrators were Nuer or Dinka soldiers, recognizable because of traditional facial scarification markings or because they spoke Nuer or Dinka.

It is unsurprising that many in South Sudan’s army are from the Dinka and Nuer ethnic groups as these are the largest in South Sudan. But given the many years of ethnic conflict and animosity in Jonglei between the Murle and the ethnic groups of the Dinka Bor and Lou Nuer, greater efforts by the SPLA to ensure the forces stationed in Pibor county were more ethnically neutral may have diminished the likelihood of abuses. Humanitarian aid workers as well as Murle civilians said Gumuruk town was relatively stable in 2013 because the SPLA commander was from the Equatoria region.

In both 2012 and 2013 Murle intellectuals and politicians requested politicians and the SPLA to assign Murle commanders in Pibor, but SPLA has not done so. This could reflect the lack of Murle SPLA commanders of the correct rank. The SPLA did however send a group of four Murle SPLA commanders, including one very senior official, to Pibor to mend frayed relations between the SPLA and civilians between August and November 2012. However according to SPLA members who Human Rights Watch interviewed, the commanders were not part of the chain of command and control of the particular units based there and had only an advisory role. [22] The four Murle commanders were recalled to Juba towards the end of 2012 and a group of Murle commandos—elite forces in the SPLA—were removed from Pibor county in June 2013.

The apparently unlawful killings of up to 27 Murle from the SPLA and the wildlife forces by the SPLA in May, and intimidation of Murle security forces by non-Murle forces, have exacerbated the perception that the army is partisan. [23]

II. Abuses Against Civilians by SPLA Forces in Jonglei

Unlawful Killings of Civilians and Massacres by Government Forces

We were hoping that the soldiers had come to protect us, but instead they are killing us.

—Woman from Pibor town, interviewed in Juba, June 28, 2013.

We are not the ones going to raid, we are not the ones rebelling against the government but we are the ones being killed.

—Woman from Pibor town, interviewed in Juba, June 27, 2013.

Human Rights Watch found evidence that 74 civilians were killed by SPLA soldiers between December 2012 and July 2013 in around 20 different incidents. Seventeen of those killed were women and children.

South Sudan’s government and representatives from the army have stated in media reports that civilians killed by SPLA have either been shot in crossfire during conflict or that the killings have been the result of “isolated incidents” or actions by “rogue” soldiers. [24] These explanations do not account for the large number of killings or patterns of abuse in the incidents described below. SPLA soldiers have repeatedly targeted civilians for abuse, or failed to distinguish between civilians and combatants.

Multiple Murle witnesses said SPLA soldiers presume civilians support Yau Yau. “You are for Yau Yau, you are helping him so we are taking this,” looting soldiers told one witness interviewed by Human Rights Watch. “You are Murle, so you are for Yau Yau”.

During the time of the shooting, the SPLA came back from the bush and were asking questions about David Yau Yau and his whereabouts. They said: ‘you civilians in Pibor here you know where the rebels are if you don’t tell us where they are we will finish you.’

—Female witness, interviewed in Juba, July 1, 2013.

The conflict in Pibor county between SPLA and the SSDM/A is a non-international armed conflict[25] and both sides are bound by applicable customary international humanitarian law including rules on treatment of protected persons and on the methods and means of warfare.[26] South Sudan became a party to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the additional protocols on January 25, 2013, and since then both parties are also bound by Common Article 3 of the Conventions, which sets forth minimum standards for the proper treatment of non-combatants, as well as Additional Protocol II relating to the protection of victims of non-International armed conflicts. Individuals who commit serious violations of international humanitarian law with criminal intent are responsible for war crimes. International human rights law also continues to apply during the conflict and may be used together with international humanitarian law, as a lex specialis, to assess the legality of particular acts and clarify obligations.[27] This is particularly relevant in issues relating to detention, due process and policing operations not linked to the conflict.

Failure to distinguish between civilians and rebel combatants violates the key principle of distinction in international humanitarian law, and acts such as making civilians the target of attacks, as well as murder, willful killings, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture of protected personsmay all constitute war crimes, as well as constituting serious violations of human rights law that should be prosecuted.[28]

Many of the killings and other abuses documented by Human Rights Watch appear to be deliberate reprisals by SPLA against civilians belonging to the Murle ethnicity, a form of collective punishment, which would also constitute a war crime. [29] “When rebels and SPLA fight in the bush, SPLA come back they do revenging on us. This is why we have to flee,” one woman told Human Rights Watch.

The abuses by government soldiers violate South Sudan’s laws including the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan and the army’s own legislation, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) Act of 2009 and the SPLA Code of Conduct.

The December 4, 2012, Lotho Incident

On December 4, 2012, 13 civilians were killed by SPLA soldiers in Lotho village, near Gumuruk town, according to a witness, a senior SPLA source, local officials and a relative of one of those killed. [30] Those killed were Oboch Ibon, Amen Korok, Tuwane Joseph, Adony Korok, Monyjor Lomodu, Jowang Kurkur, Kaya Babayo, Kongkong Adit, Baal Chelan, Logocho Ajubong, Arzen Ajubong, Korilem Ibon and Kena Logocho.

SPLA soldiers approached a group of civilian men playing a traditional board game and demanded that the men hand over their guns. The men gave the SPLA two rifles. The SPLA then tied up the men into two groups of seven. The soldiers executed the men in one group at the site and took the men in the other group some distance away and shot them. One man, shot in the shoulder and left for dead, survived the shooting and was later found by other community members.

The January 27, 2013, “Kuburin” Incident

On January 27, 2013, an altercation between a former member of Yau Yau’s forces, James Kuburin, who had integrated into the SPLA at the end of 2012, and a small group of SPLA soldiers led to chaos in Pibor town. According to local government officials and SPLA sources, after a drunken SPLA soldier tried to shoot and kill Kuburin with a grenade, Kuburin and his group of other former rebels ran into the bush. SPLA soldiers fired shots in the market and then went on a rampage, chasing and shooting at civilians and burning civilian’s homes. Eight witnesses described seeing soldiers shooting at people, burning houses or a combination of both to Human Rights Watch. Officials in the town estimate that 150 huts were burned. [31]

“The SPLA were indiscriminately firing, every soldier in the market just started firing. People ran in different directions,” a staff member from an international organization who witnessed the incident said. [32] He told Human Rights Watch that after the shooting he saw a lot of empty shells from AK 47s and shells from 15 or 20 rounds from 50 caliber machine guns, which are usually fired off of the back of mounted trucks.

In panic, residents fled to a church close to the market, the UNMISS compound and the commissioner’s house, for safety. One resident said that after she fled to the Pibor UNMISS compound she saw soldiers in pursuit of fleeing civilians demanding that peacekeepers send the civilians back out of the compound. [33] This was confirmed by a senior staff member at UNMISS. [34]

Local government officials said that seven civilians were killed by SPLA soldiers that day, including three elderly or disabled people burned in their homes. Human Rights Watch was able to corroborate five of the deaths, including the shooting of James Konyi by soldiers while trying to flee the town, and the shooting of a woman known as “Yaiko” and another man, Tho Tho Lanya, close to the market, and the burning alive of an old man and woman. [35] One witness described the death of an old man, Nyathi Ngnnloki:

The soldiers were moving randomly, shooting and went to my home and started burning it. (Nyathi) was inside, he had a stroke so he is paralyzed in his arm and leg, one side of his body is not working … the rest of the family ran because of the soldiers, because of the shooting, and he was left inside.

The May 26, 2013, Manyabol Incident

SPLA soldiers killed 12 people in Manyabol town on May 26, 2013, after a firefight the same day in the nearby bush that killed two SPLA soldiers, according to local authorities, two eye witnesses and relatives of those killed.

The eyewitness told Human Rights Watch that enraged soldiers entered a market area and started beating children and men. The soldiers shot eight civilian males including three chiefs and five other men, four of them at close range. The chiefs were: executive chief Nyelang Ngaruben, Erith village chief Nyikcho Korogi and chief Matthew Logocho. The five men were Lothiko Allan, businessman Jacob Kuju, Thonyan Kireeru, Matthew Logocho and Allan Kima.

All those killed were unarmed, eye-witnesses said. Community members and authorities from the area said that another four men from the community, including two volunteer policemen, Loyen Mabior and Monech Ibon and two other men, Loyen Allan and Matuwoch Oleyo, were executed the same evening in the army barracks. The civilian population of the town fled Manyabol following the killings.

Other Killings in and around Pibor Town, December 2012 to May 2013

On December 24, 2012, SPLA soldiers on patrol and looking for rebels who, according to a staff member from an international agency, had been making forays into the town at the time, shot two off-duty and unarmed Murle prison wardens, David Koliyom and Simon Nyonyo, in the head in Pibor town.

The wardens were visiting Pibor town and had climbed trees because they were afraid of the SPLA patrol group. One other man who lived in a house beside the tree was also injured. [36] There had been a firefight between rebels and SPLA soldiers three nights before on the edges of Pibor town.

Also in December, SPLA soldiers shot dead two male dancers Kaka Laurien and Odoch Ngachibom in Pibor town and injured two others, Logocho Lokode and Thunyan Kemerbong. According to Murle community members and government officials the dancers were detained by soldiers as they passed between the barracks and the market and then shot in retribution for the deaths of two soldiers killed by unknown gunmen, presumed to be Yau Yau rebels, on the edges of Pibor town. [37]

On December 4, 2012, a mentally disturbed man known as “Bal” was shot dead when he ran from soldiers rather than sitting still, as instructed. [38]

On April 1, 2013, SPLA soldiers shot at close range at a family group traveling to Pibor town near to Gumuruk town. Five family members were killed and seven others were wounded before one of the SPLA soldiers stopped the others from shooting the rest of the group. One survivor told Human Rights Watch:

We were reaching the river near Thongach and found SPLA there and decided to spend the night there. We got water and the children were crying [then suddenly] we were surrounded by soldiers, it was a big number. Some of us ran away, [then the soldiers] shot at them; they were killed on the spot.

Those killed were a woman Mathoulocl Maothvack, a young man Meryamoi Lothiko, an old woman Othokino Nyathi, an old man called “Jakor” and a small child. [39] The soldiers were reportedly on their way back from battling rebels. [40]

In another incident, according to a local government official and a relative of one of the casualties, SPLA soldiers shot and killed two Murle wildlife rangers and a civilian on April 28, 2013 in retribution for the death of an SPLA soldier on the Pibor town airstrip the same day, presumed to have been killed by Yau Yau rebels. The rangers’ killings were followed by extensive looting in Pibor town in May, mainly by the SPLA. [41] The combination of the killings and looting caused many of Pibor’s residents to flee.

On May 8, 2013, Ngacheni Manyajuie, her baby Baba Nyandit Gogol and her daughter Thina Manyajuie, were shot and killed by SPLA soldiers while trying to enter into Pibor town. Another child was stabbed by the soldiers, but survived. [42] The case has been widely documented by international organizations and family members have told the story to the AL Jazeera news channel. [43] “I saw the bodies. I went with the people to pick them (for burial). The soldiers said that they had done it; in the ambush … they said we just killed them,” a civil servant from Pibor town told Human Rights Watch.

According to community members, a woman and her child, originally from Marien village, were also killed in May by soldiers near the Presbyterian church in Pibor town. [44] Murle witnesses from Pibor also saw soldiers kill ‘Rhoda,’ a mentally disturbed woman in Hai Matar area of Pibor on May 25, 2013, after she returned to Pibor to look for food. [45]

Killings Outside of Population Centers

According to local officials from Pibor county, soldiers killed three women gathering wild fruits on the roadside close to Manyabol town on December 22. “I don’t know why these women were killed, they were collecting wild fruits and had nothing but empty bags with them,” one of the local officials who reported the incident said. [46]

One official also told Human Rights Watch that SPLA soldiers killed four chiefs close to barracks in Yot village in Vuvet area in December, after a SPLA soldier was killed by Yau Yau rebels. A relative of two of the chiefs corroborated the story. Local authorities also reported that three men had been killed in Thodoch cattle camp, near Manyabol town on November 12, 2012. The men were apparently interrogated about where Yau Yau’s forces were before being executed. Another three old men had been killed in a cattle camp beside the Jurich river, also by SPLA forces, in March 2013.

Human Rights Watch also documented, based on interviews with witnesses who travelled into towns, some incidents that took place outside of the main towns or population centers. One Murle man described to Human Rights Watch how he buried another man, Baba Ajak, who was killed by SPLA soldiers in April while trying to sell firewood near an SPLA camp close to Gumuruk town. One of Baba Ajak’s companions, Baba Nyonyo, was wounded in the same incident. [47] In another incident in mid-May, a survivor of an SPLA attack on a cattle camp in Vivino boma, near Gumuruk town, told Human Rights Watch that he saw soldiers kill one man and injure at least one other man. [48] It is possible that many more abuses took place outside of the main towns.

Killings by Auxiliary Police in Manyabol and Gumuruk

South Sudan’s auxiliary police, who were deployed to Pibor in early 2013, also committed abuses including killings in the Manyabol and Gumuruk areas, according to local authorities. The auxiliary police, a group of specially trained men, were also implicated in abuses against civilians during the disarmament process. [49]

Auxiliary police, angered by heavy losses in an auxiliary police-SPLA joint patrol unit during a fight with Murle rebels, “executed” six people in Manyabol and Gumuruk towns on March 21, 28 and 29, 2013 according to local government reports, relayed in a confidential UNMISS report seen by Human Rights Watch. [50] One of those killed was Murle Brigadier Michael Rio (see below).

Human Rights Watch was able to corroborate five of the reported killings by the auxiliary police. In Gumuruk they killed two civilian men, Mothguzul Karok and Arzen Aria, on March 29. Eyewitnesses said Aria panicked when he saw the armed auxiliary police and ran but was gunned down. In Manyabol, the auxiliary police killed an old man, Meroi Maze Adiker on April 12, 2013 at a water point, together with two other women. According to his relative, the auxiliary police were in Manyabol after a failed offensive to the Lotila area. After shooting Adkiker they took his cattle, which he had earlier refused to give them. Staff members from an international organization corroborated the story.

Unlawful Killings of Murle Soldiers and Members of the Armed Forces

In March and May 2013 SPLA soldiers also killed several Murle members of government security forces, including high-ranking officials, in what appear to be extrajudicial killings. Murle leaders emphasized to Human Rights Watch that the killings provoked widespread anger.

Government officials and community members from Gumuruk said that Murle SPLA Brigadier Michael Rio was killed in the town on March 21, 2013 by members of the auxiliary police force. Human Rights Watch was shown his grave. Human Rights Watch was unable to find an eyewitness to the event.

In early May, shortly after Murle rebels had captured Boma town, SPLA soldiers killed a Murle Brigadier General Kolor Pino, a senior official in South Sudan’s wildlife rangers, together with up to 10 other people who were traveling with him, including bodyguards. According to relatives and officials from the wildlife rangers, Pino was stopped by soldiers in Kesingore village while traveling back to Boma town. SPLA soldiers ordered Pino and his men to get out of their car and to sit down, then shot dead Pino and at least five men, including three other wildlife rangers and two policemen. Five others ran when the shooting started and are believed to have also been shot and killed. A statement issued by South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir on May 17, 2013 confirmed the deaths of Pino “and five others … in cold blood by rogue elements of our security service.”

In another incident in May, SPLA soldiers arrested and killed 12 Murle SPLA soldiers. The Murle soldiers had fled, together with civilians when rebels attacked Boma town on May 8. After recapturing the town, the SPLA passed messages to the soldiers to return to Boma. However when the soldiers—Hassan Maze Guto, Hassan Jakor, Konyi Meryaboyo Kerju, Kororo Meryatigle, Oseinnean Geleny, Becko Ngatibe, Kelang Lokoni and five others returned to Boma—the SPLA arrested them and reportedly executed them without a trial. [51]

Even if these members of South Sudan’s security services were believed to have joined the enemy, under international humanitarian law they were still entitled to humane treatment while in the power of the SPLA or auxiliary police, and no passing of sentence or carrying out of executions can be done in the absence of a judgment from a regularly constituted court, “affording all judicial guarantees which are generally recognized as indispensable.” [52]

If, as described, the killings did not take place in the heat of battle, the killings were also unlawful under South Sudanese law. While treachery is punishable by death (or life imprisonment) under the SPLA Act 2009, anyone facing such charges should be tried before a military court. [53]

Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm allegations from two separate sources that four Murle from the elite SPLA “commandos” were killed by military Intelligence at the beginning of June 2013 near Boma town.

Unlawful Arrests of Murle Civilians by Security Forces

Human Rights Watch documented two incidents of unlawful arrests of Murle civilians by security forces.

Eight civilian men were arrested on March 8, 2013 by soldiers in the Pibor town market who overheard an old man sitting close to them say they were members of Yau Yau’s army. [54] The men were lashed 20 times each and interrogated about their alleged links to Yau Yau. After 36 days in military detention in Pibor and Bor, the men were moved to a civilian prison in Bor. The men are Isaiah Mama Chacha, Philip Anyibi Ngadalan, Juma Thiro Ngamthame, Baba Limirikori Agok, James Ibon, Sebiet Lugju Kong Kong and Jospeh Lodhuk Cholie. They were released after Murle politicians intervened on their behalf. They were never charged with any crime.

A former detainee who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that the men were not allowed family visits, were not given access to a lawyer or taken to any court, or given any clear charges. [55] The arrests were also violated due process protections contained in national legislation. [56]

In another incident, two Murle Presbyterian priests, Reverend Idriss Nalos Kida and David Gayin, were arrested from their homes in Juba on May 19, 2013 by what appeared to be a mixed group of security personnel and at time of writing appear to still be in detention. [57]

A large group of armed men, some in uniform arrested Kida around 8 p.m., beat him, and verbally abused his family members then took him away. Another group of security forces arrested Gayin at around 11p.m. then took him away in a Toyota pickup after beating a neighbor who tried to intervene.

The men’s families were not given a reason for the arrests and told Human Rights Watch they do not know where they are being held. The circumstances surrounding their arrests remain unclear but family and church officials believe they may have been arrested in connection to their participation in a failed government-sponsored attempt in early 2013 to get Yau Yau to surrender.

Displacement of Civilians

The conflict between the rebels and the army as well as inter-ethnic fighting have caused large scale civilian displacement from Jonglei in 2012 and 2013. Displacement within Pibor county, often caused by SPLA abuses, has been dramatic. In mid-July all six population centers in Pibor were almost entirely emptied of civilians. [58] At the beginning of August 100,000 Murle—most of the county’s population—were in need of emergency humanitarian assistance. [59] An estimated 7,000 Murle have been displaced to Juba. Around 1,500 of the 16,500 refugees from Jonglei who have fled to Kenya and Uganda this year are believed to be Murle. Some 3,400 Murle have sought asylum in Ethiopia. [60] Until July, humanitarian officials could not reach the vast majority of the displaced Murle population still in Pibor county. In July, officials of humanitarian agencies successfully negotiated with the SPLA and Yau Yau for access to territories controlled by both parties and by late August more than 65,000 people in Pibor county were registered to receive assistance. However as of this writing, humanitarian agencies have still not succeeded in reaching a significant proportion of the population. [61]

SPLA abuses were a primary reason Murle civilians gave for fleeing their homes. When SPLA soldiers attacked the group of chiefs and others in Manyabol on May 26, 2013, the entire civilian population of the town fled, illustrating the high level of fear that the killings and other abuses provoked.

In Pibor, an entire neighborhood moved to another part of town following the nighttime killing of two Murle prison wardens on December 24, 2012. “As soon as the sun was up people started moving out of the neighborhood into the market area,” a staff member from an international agency working in Pibor at the time said. He said there had already been some small displacement following earlier looting and harassment by SPLA soldiers.

SPLA attacks on civilians on January 27, 2013 caused large scale displacement in Pibor. [62] Many people ran to the bush, rather than remain in the town even under the protection of UNMISS or in the commissioner’s house. According to local authorities and an international source many people did not return.

Incidents of killings of civilians by SPLA in April and May in Pibor town again caused widespread fear and large scale displacement, and widespread looting by soldiers in mid-May also contributed to significant displacement. [63]

In another incident, when SPLA soldiers reportedly burned down a number of homes and government buildings in the Maruwa Hills area, apparently in retribution for the death of a SPLA soldier in a fight, civilians all fled the area. Human Rights Watch was unable to corroborate that soldiers burned the homes but the civil administrator told Human Rights Watch civilians had fled because of the burning. [64] According to humanitarian aid groups, attacks by SPLA on the Labrab area in 2013 also caused large scale civilian displacement. [65]

Ordering the forced displacement of civilians in a conflict is prohibited under international humanitarian law and parties to the conflict have a duty to prevent displacement during conflict. [66]

Fear of Return to Towns and Impediments to Assistance

Residents of Pibor county normally congregate during the rainy season as grazing areas flood and roads leading out of towns become almost entirely impassable.

Although towns were until July the only place to access food aid and health services, and although SPLA have made some efforts to call civilians back to towns after fleeing, those who fled SPLA abuses have mostly not felt safe to return to towns under SPLA control. [67] As a result, tens of thousands of civilians remain in the bush and fear seeking even urgently-needed services in the towns. [68]

Aid workers reported that a girl who appeared to have stood on a land mine in April, close to Pibor town, spent a week in the bush without medical care. A boy with a gunshot wound did not receive treatment for more than a week after being shot because those looking after him were too scared to enter Pibor town. And although the WFP began distributing food in Pibor to hundreds of civilians in late June, women and children preferred to take food back to the bush, rather than stay in the town.

Some Murle civilians who fled Gumuruk town following the Lou Nuer attack in July 2013 returned to the area but stayed away from the town center, where soldiers are stationed. More than a month after the attack, aid workers had only found a handful of injured Murle who had sought treatment in areas under government control. [69] Humanitarian groups and local government officials told Human Rights Watch that this was because civilians were too afraid to return to towns and report injuries.

Human Rights Watch also heard reports of SPLA soldiers preventing civilians from entering towns to access services. In mid-February civilians were being regularly harassed when trying to enter or leave the town, according to an international aid worker living there at the time. A group of women trying to cross the river into Pibor were shot at by SPLA in March. [70] A number of those killed by SPLA soldiers in April and May died on the edges of the town, further frightening Murle from coming and going from the town. According to a senior Murle official, soldiers forbade entry or exit into Pibor for at least a week in June.

A senior SPLA commander in Boma at the beginning of June, a few weeks after the town was recaptured by the government, told humanitarian officials assessing humanitarian needs in the town that Murle could only return when there was peace between Juba and David Yau Yau. [71]

Soldiers occasionally obstructed the delivery of assistance. For example, humanitarian agencies seeking to access populations outside of Pibor in May were told that they could not leave the town, ostensibly for security reasons. Similarly, after Boma was re-taken by the SPLA in mid-May humanitarian workers were forbidden from leaving the town or from speaking to civilians without SPLA escort.

SPLA soldiers shot and killed two unarmed women collecting food aid from Pibor town on July 31, 2013. Anybi Baba was killed on the spot, Atiel Rio died later in a military clinic. A six-month-old baby was also wounded. WFP was forced to cut off food assistance from the town for around a week following the killings, despite the aid being desperately needed. [72] Soldiers were subsequently arrested. [73] Further insecurity and harassment of civilians by soldiers forced WFP to cease food distribution a second time on August 18, 2013. [74]

Under international humanitarian law parties to a conflict must allow rapid and unimpeded access of humanitarian aid to civilian populations in need, subject to their right of control.[75]

Pillage and Destruction of Items Indispensable to Civilian Survival

“The soldiers take things … because they do not want good things for the Murle.”

—Male witness, displaced from Pibor town, Juba, June 25, 2013.

Both parties to the conflict have caused damage to vital civilian property in towns. SPLA soldiers and rebel fighters looted civilian property in Gumuruk in September, 2012, including a clinic run by the international medical and humanitarian aid organization, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).[76] In 2013, the looting and destruction was far more extensive. In all population centers, almost every service provider—whether churches, schools, humanitarian agencies—was destroyed or put out of service, a devastating loss to the Murle civilian population. Only one clinic in the entire county was operating until July when humanitarian agencies began providing emergency assistance in Dorein and Labrab. Aid workers told Human Rights Watch that even if the security situation improved it would take months for some agencies to be able to repair damage and operate again.

Evidence suggests that the SPLA was responsible for some of the worst looting and destruction of property in Pibor and in Boma town, where the UN estimates that over a million dollars of damage has been done to NGO property.[77]

Under international humanitarian law parties may not deliberately target civilian objects.[78] International humanitarian law also prohibits the destruction of objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population. The only hospital, clinics and stores of food aid, all necessary for the survival of a population facing chronic food insecurity were extensively looted and destroyed, including by the SPLA. Pillage—the forcible taking of civilian property by enemy combatants for private or personal use—is also a war crime.[79]

Pibor Town

Looting of Homes, Neighborhoods

Of 25 Murle Human Rights Watch interviewed who had fled Pibor town, 17 said that their homes had been looted by soldiers at least once during 2013. Several people said their homes had been looted more than once; others said that their entire neighborhood had been looted. During the January 27, 2013 “Kuburin incident” soldiers burned down around 150 homes, looting others. Over the following months, soldiers frequently looted Murle civilians often violently and at gunpoint. It is not clear if the lootings were opportunistic or linked to incidents of fighting.

In one example, soldiers took plastic sheeting off the thatch roof of a woman’s home in February. [80] In April soldiers came back again and beat her sister, who tried to stop the soldiers, until she became unconscious. Soldiers severely beat the wife of a youth leader known as “Yang” while looting her home, according to an eyewitness. [81] Two female respondents said that they were slapped by SPLA soldiers while their homes were being looted. [82]

Another woman saw soldiers beat her neighbor, a young woman, for trying to protect her possessions in April. [83] The soldiers took the fence around her house as well as all her clothes, utensils and bed. “They came in. I asked ‘what do you want?’ They said: don’t talk, this place is not yours’. They threatened (to kill) me and took what they wanted,” she said.

Another man, whose home was among those burned by soldiers on January 27, said his new home was looted in May. “They took everything, the bed, food, utensils. The soldiers said to me: ‘If you survive today, then tomorrow you will not,’ and ‘we don’t want to see you here again,’” he said.

On May eight soldiers broke down the door to the house of a member of the church, and said they would kill him if he did not hand over all his money. On May 12, when soldiers extensively looted Pibor market, soldiers chased him out of his shop and looted all the goods he had for sale. On May 14 other soldiers came to his home and took away his mattress, bed and the plastic sheeting on top of his roof.

Looting of INGOs, Service Providers, Schools

Between May 10 and 20, soldiers looted a number of compounds belonging to international organizations, destroying much of the MSF clinic, as well as looting the town’s market, local businesses and large numbers of homes. The reason for the sudden surge in looting is unclear, but is likely partly a result of SPLA anger over the capture of Boma town by Murle rebels on May 8.

According to a local government official, the MSF hospital was first looted by SPLA soldiers on May 11. [84] In a press release issued on May 16, MSF described the hospital as “systematically destroyed.” Drug supplies were strewn on the ground, warehouse tents were slashed, hospital wards were ransacked and even electricity cables were cut and ripped from the walls. Eyewitnesses saw soldiers looting the MSF clinic. [85] According to government officials a small government clinic was also destroyed during the mid-May looting and destruction.

SPLA soldiers also looted the compound of the international humanitarian aid organization, Intersos, and a World Food Program storage tent on May 11 and 12. Attacks on humanitarian infrastructure and objects used in relief operations, including food and medicine, as well as deliberate impediments to relief efforts, are serious violations of international humanitarian law and may constitute war crimes.[86]

Officials from Jonglei state government blamed “a few elements in the organized forces, police and prison services for the looting.” [87] However numerous eyewitnesses who had been resident in Pibor town at the time and eyewitnesses from aid groups told Human Rights Watch and journalists that they saw soldiers looting. [88]

The large quantities of items taken indicate at least some of the goods must have been moved by vehicle. This suggests the commanders knew of the looting, and that the crimes were the actions of more than a few rogue security forces. A senior SPLA officer told Human Rights Watch that looted goods had been stored in the SPLA barracks. Government officials and a local representative of an international organization also said that soldiers set up a shop in the army barracks selling looted items. One UN source said that following the looting, he also saw looted goods in a police office. [89]

Some key service providers were looted or destroyed before May. The Pibor office of one of the few national Murle NGOs, SALT, was looted by soldiers in February. “We were told not to return,” one man associated with the organization said. As well as taking diesel and computers belonging to the organization, soldiers also broke windows, doors, cupboards and destroyed books apparently for no reason but to render them unusable.

Two witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they saw soldiers looting Kandakoro school in Pibor in April. Pibor’s separate girls and boys primary schools were looted in May. Witnesses describe wanton destruction of books and cupboards as well as theft of chairs and tables. A staff member from an international agency said that schools in Gumuruk and Boma were being used as barracks. [90] A school in the Labrab area was reportedly also destroyed by soldiers.

Looting of Market, Churches

Five Murle told Human Rights Watch that Pibor market was looted during the mid-May looting. The local government official’s report said that items were stolen from the main market on May 16 and that seven shops were burned by soldiers in the market on May 21. Two Murle businessmen told Human Rights Watch that they or their workers had witnessed SPLA soldiers taking their grinding machines during the May looting. [91]

A member of the Presbyterian church in Pibor described witnessing soldiers taking all of the property of the church, from priests’ gowns to building materials like iron sheeting, nails and cement to seeds for community distribution. The Africa Inland Church was also looted in mid-May.

Boma Town

During the capture of Boma town by SSDM/A rebels on May 8 and the subsequent recapture by the SPLA on May 18, soldiers destroyed and looted homes and other civilian property. Key education and health facilities were utterly destroyed. The Merlin hospital, at the time the only facility with in-house surgical capacity in Pibor county and served over 95,000, was “totally destroyed.” [92] Other agencies’ compounds were also destroyed including the compound belonging to ACROSS, a Christian aid and development agency. [93] Around 600 metric tons of food was stolen from a large WFP storage tent. This food had been pre-positioned to serve more than 23,000 people, including school children through school feeding programs.

While the extent of looting by rebel forces is not clear, evidence suggests the majority was by SPLA. Human Rights Watch spoke with three international agencies that had staff in Boma town during most of the SSDM/A occupation. They reported that while SSDM/A fighters did steal many items in Boma, including communication equipment, looting was not extensive. It is unlikely that the rebels would have been able to carry all of the many tons of stolen property into the bush.

An old man who managed to get a lift out of the town on an SPLA truck said he traveled together with fridges, beds, and computers taken from Boma town and that he saw parts of Boma burning from hills nearby after the SPLA had retaken the town. A staff member from an international agency, who visited Boma soon after the attack and some 10 days after the SSDM/A forces left the town, said that the ash on the burned houses was still fresh suggesting recent burning by SPLA soldiers. A member of an aid agency told Human Rights Watch that SPLA commanders had told him that the huts had been burned by soldiers traumatized by SPLA casualties during their fight to recapture the town.

III. Government and UN

Responses to Abuses by

SPLA and Inter-ethnic Conflict

Government Response to Abuses by Soldiers

At least four investigations into abuses by soldiers in Pibor county have been instigated by South Sudan’s government. The SPLA has announced three SPLA arrests for human rights abuses but none of the findings of these investigations has been made public, and to Human Rights Watch’s knowledge the government has not taken steps to compensate residents for homes burned by soldiers or the deaths of family members during the violence.

The arrest of SPLA commander stationed in Pibor town since April 2013, Brig. James Otong, was announced to the media on August 20. The Director of Military Justice, Brig. Gen. Henry Oyay, interviewed by Human Rights Watch, did not state the exact charges against Otong but said he is being held responsible for human rights abuses and crimes committed by soldiers under his command in Pibor county, including killings of civilians, cattle raiding and looting of civilian property. Oyay also said that at least 84 soldiers have been court martialed in 2012 and 2013 (exact dates were not provided) but did not specify on what charges although he said some court martials were for human rights violations, including rape.

In a May 17, 2013, statement South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir condemned “reported abuse by ill-disciplined elements in the regular security forces.” [94] He said that “those responsible for the reprehensible crime” of killing Murle wildlife service senior officer Brigadier General Kolor Pino would be held accountable and that the government would “not tolerate any violence against its citizens or looting of property whether belonging to civilians or humanitarian agencies.” At time of writing, investigations by military justice into the incident was still ongoing. [95] Kiir has since condemned SPLA abuses in Pibor in two further speeches. [96]

After the looting and destruction of civilian homes and aid agencies’ compounds in Pibor in mid-May, the SPLA sent a team of judge advocates in a Board of Inquiry (BOI), on request from the WFP, to look into looting of food aid during this period. [97] Officials from UNMISS, providing technical assistance, accompanied BOI members to Pibor town in early June. The BOI found that both soldiers and SSDM/A had looted the WFP compound and other humanitarian agencies’ compounds, but has not made the results public.

In the third inquiry, a senior SPLA official, General Johnson, sent military justice investigators to investigate human rights abuses in Pibor, Gumuruk and Manyabol towns in mid-June. Full findings from the investigation have not been made public, but both the BOI into the looting and Johnson’s efforts contributed to the arrest of Otong [98]

A fourth investigation by military justice investigators into the killing of two women in Pibor town on July 31 by soldiers has been completed. Two soldiers were court martialed and imprisoned for the crime. [99] Military justice officials investigated within days of the killings, a speedy response in contrast to earlier investigations that should be replicated for any further abuses by soldiers.

In an earlier initiative, senior officials from South Sudan’s government also traveled to Pibor town following the January 27 violence that led to mass displacement. Local officials and community members living in Pibor town at the time said that the visit helped bring relative calm back to the town but expressed disappointment that no soldiers were punished. The SPLA had previously deployed judge advocates, lawyers from its military justice directorate, across Jonglei during the disarmament in an effort to increase accountability for abuses; however, when operations against the Yau Yau rebels started they were recalled. Judge advocates have traveled to Pibor county to do investigations but should be permanently located there to advise commanders and help curb any future abuses.

For a brief three-month period SPLA Brigadier Peter Ruach, who had been in command of the troops that rampaged through Pibor on January 27, 2013, was temporarily transferred out of Pibor county. A new SPLA commander, Otong, was appointed in April. According to Murle community members Otong made a speech upon his arrival that seemed to acknowledge that abuses had been taking place. [100] However soon after Otong’s arrival soldiers looted Pibor town and a number of killings took place. To the consternation of many Murle, Ruach was sent back into Pibor in June and as of this writing is stationed with three brigades in Gumuruk town. His return to Pibor suggests that his temporary transfer was administrative, not punitive.

The SPLA should be more transparent and publish findings of its investigations, and keep the public informed ahead of and during the prosecution of Otong. Commanders who have overseen abuses and failed to intervene to prevent or punish their subordinates should be promptly removed and abusive soldiers arrested and prosecuted. SPLA judge advocates should also be deployed to help curb abuses. If South Sudan’s government fails to provide transparent accountability for crimes committed and for the removal of abusive soldiers many Murle will likely choose to remain away from towns, causing long term displacement.

Government Response to Inter-ethnic Conflict

South Sudan’s government has for the most part failed in its responsibility to protect communities in Jonglei from inter-ethnic fighting that has killed thousands of people in the past three years alone. A lack of accountability for crimes committed by members from the different ethnic groups has resulted in revenge attacks.

At the beginning of July 2013, from approximately July 4 to 13, thousands of Lou Nuer fighters from Akobo county carried out an attack on Pibor county, also engaging directly in clashes with Yau Yau’s forces. [101] The attack, revenge for several brutal attacks by Murle on Lou Nuer areas in 2012 and 2013, is the latest in a cycle of violence that has caused enormous anger and fear across the region. But allegations that officials supported the organization of fighters, largely in response to the threat of men heavily armed by Yau Yau on disarmed Lou Nuer communities, makes this attack especially problematic. [102]

On January 16, 2013, Jonglei’s Governor Kuol Manyang issued an order establishing community police units in Jonglei state. [103] A local politician and staff from international and national organizations working in the area told Human Rights Watch that these policing units were formed without sufficient, if any, oversight, which has had the effect of allowing factions within communities in Jonglei to acquire arms. [104] According to government, UN and international NGO sources, in February 2013, Manyang also encouraged Lou Nuer young men to dig up guns buried during the 2012disarmament period. [105]

Humanitarian aid workers and civilians from the area said that there were clear signs of Lou Nuer mass mobilization by mid-June. [106] However there was no attempt to stop the mobilization and UNMISS officials, diplomats and a politician from the area said that government officials from Lou Nuer areas denied that the mobilization was taking place even after the fighters had already begun moving south towards Pibor. [107]

By the time of the attack in July, there were hardly any civilians remaining in Pibor’s towns as they had already fled to the bush fearing harm from abusive soldiers and the impact of the SPLA-SSDM/A conflict. During the attack, the SPLA Spokesman told Human Rights Watch that the SPLA did not know where civilians were and had too few troops and no capacity to leave towns in severe rainy season conditions to protect them. [108]

Two months after the attack, to Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, none of the Lou Nuer who participated in the attack have been investigated or arrested. [109] Human Rights Watch saw group of around 20 Lou Nuer, who had been treated for injuries at a hospital in Bor, in the government-run Jonglei State Women’s Association building where they were being fed and housed. The Lou Nuer fighters openly admitted to being involved in the attacks.

In contrast to the SPLA’s inaction to protect Murle, the SPLA did intervene to protect the Lou Nuer areas from counter-attack by Murle in mid-July. An UNMISS official told Human Rights Watch that “within 24 hours” of warnings that Murle fighters were planning a revenge attack on Lou Nuer areas the SPLA dispatched helicopters to look for them. [110] Staff from international aid agencies on the ground told Human Rights Watch that the government encouraged Lou Nuer men to form defensive positions against a Murle revenge attack.

Human Rights Watch also heard a number of reports from credible sources that SPLA flew ammunition to Lou Nuer areas just before the Lou Nuer attacked Pibor county, and second hand reports from South Sudanese from the area that the SPLA gave ammunition to Lou Nuer youth leaders. These are serious allegations and must be urgently investigated.

Government-supported church-led efforts to bring peace to Jonglei should include the promotion of accountability for participants in these ethnic attacks in the region and should call for the government to act in a non-discriminatory and even-handed manner in attempts to provide protection to different communities. [111] These need to be greatly increased to take the burden of protecting communities away from civilians. The government should commit to a long overdue full investigation into violence in Jonglei. International experts from the AU or UN should be included in the planning and carrying out of the investigation. Communities in Jonglei should be consulted on how the research should be conducted.

UNMISS Response to Abuses by Soldiers

UNMISS has a robust mandate to protect civilians and promote human rights. Under Security Council resolution 1996 (2011), adopted under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, it includes “deterring violence including through proactive deployment and patrols in areas at high risk of conflict, within its capabilities and in its areas of deployment, protecting civilians under imminent threat of physical violence, in particular when the Government of the Republic of South Sudan is not providing such security”.

Human Rights Watch was unable to determine whether when security forces shot at and killed civilians in Pibor at the end of January, in Gumuruk towards the end of March and in Manyabol in end-May, UN peacekeepers on the ground at the time could have done more to actively intervene. [112] However, this pattern of non-intervention reflects a widely-held view, both by Southern Sudanese and international staff working in South Sudan, including UNMISS staff, that peacekeepers do not have a clear strategy in how to engage in protecting civilians through the use of force especially against the SPLA. [113]

Civilians, local officials and aid workers complained that UNMISS patrols were not frequent enough to stop abuses from taking place and that UNMISS officials have failed to build relationships with the Murle community and leadership in Pibor county or patrol far enough outside of the main towns, including areas where Murle now reside. On August 9, 2013, following international outcry over events in Jonglei, UNMISS began patrols into areas outside the main towns of Gumuruk and Pibor and increased patrols within the town. Humanitarians have welcomed these patrols and have reported that civilians say they feel safer because of them.

These patrols should have begun much earlier. UNMISS should now patrol for longer distances outside of Gumuruk and Pibor towns, including on multi-day patrols. Preparations to increase patrolling much further in the upcoming dry season should begin immediately.

Since October 2012, UNMISS compounds in Gumuruk and Pibor towns have provided safe haven for more than 7,000 civilians on at least 10 occasions. [114] In some cases civilians have fled to the compounds because of conflict between Yau Yau’s forces and the SPLA. In other cases frightened civilians fled to UNMISS following abuses by soldiers, for example on January 27. “If it was not for UNMISS we would not have survived,” one woman who had sheltered in the facilities following the January violence told Human Rights Watch. [115]

However, Human Rights Watch heard credible allegations that peacekeepers failed to protect a civilian in Manyabol during the SPLA attack on civilians on May 26, 2013.. According to two men who were present in Manyabol on the day, the man who ran to the temporary UN base on that day was handed back to South Sudanese soldiers by UN peacekeepers and then executed by the SPLA the same night. [116] This is a serious allegation and should be investigated.

UNMISS has been largely silent about the SPLA’s abusive tactics. UNMISS’ Human Rights Division reports in the past on inter-ethnic conflict had provided powerful testimony and clear recommendations to the government. However, recent human rights reports were not made public even though UN human rights officers investigated and reported internally on several incidents of SPLA abuses. [117]

In a June 26, 2013, UNMISS released its strongest statement on the violence in Jonglei state. The mission said it was “deeply concerned” about human rights violations in Jonglei state but without making clear that grave abuses had been committed by SPLA soldiers, and its description of “serious abuses allegedly committed” by “ill-disciplined elements of the security forces” undermines the severity of the extent and clear pattern of abuses by SPLA and the failure of authorities to hold abusive soldiers to account. [118]

Attacks on UNMISS may account for some of its apparent reticence in both providing physical protection to civilians at risk and publicly condemning the government. In December, SPLA soldiers shot down a UNMISS helicopter killing all four crew. [119] On April 9, 2013, unknown gunmen killed five peacekeepers and seven civilians staff in an ambush on an UNMISS convoy in Pibor county. [120]