Raised on the Registry

The Irreparable Harm of Placing Children on Sex Offender Registries in the US

Summary

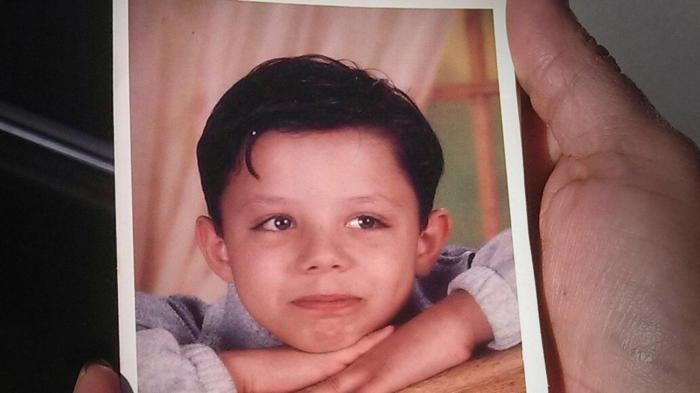

Jacob C. was 11 years old and living in Michigan when he was tried in juvenile court for touching, without penetrating, his sister’s genitals. Found guilty of one count of criminal sexual conduct,[1] Jacob was placed on Michigan’s sex offender registry and prevented by residency restriction laws from living near other children.

This posed a problem for his family— Jacob’s parents were separated, his father lived in Florida, and Jacob could not live in the same house as his little sister. As a result, he was placed in a juvenile home. When Jacob was 14—and still unable to return home—he became the foster child of a pastor and his wife. According to Jacob, the couple helped him to “deal with the trauma” of growing up on the registry.

Since his offense fell under juvenile court jurisdiction, Jacob was placed on a non-public registry. But that changed when he turned 18 during his senior year in high school, and his status as a sex offender became public. Parents of his schoolmates tried to get him expelled and he had to “fight to walk across the stage” at graduation. Jacob attended a local university in Big Rapids, Michigan, but ended up dropping out. “[I was] harassed for being on the registry,” he said. “The campus police followed me everywhere.”

In February 2005, at age 18, Jacob left Michigan to start a new life in Florida and reconnect with his father living there. Jacob worked for his father’s company for a few months. He soon fell in love, married, and had a daughter. A year later, he and his wife divorced, and Jacob was awarded joint custody of his daughter. During this time, Jacob tried to follow Florida’s sex offender laws, but continually ran afoul of residency restrictions that required him to check-in with police on a daily basis and provide them with a home address. At one point, for example, Jacob’s home was too close to a school and he had to move. Another time, he failed to register a new address after a period of homelessness and was arrested and convicted of the felony of failure to register.

While court documents describe Jacob as a doting parent to his daughter, Jacob’s wife came under investigation by Florida’s Department of Children’s Services in 2009 for not having electricity in the house. However, when the court in that case learned of Jacob’s felony conviction for failure to register, the judge denied him custody of his daughter, citing Florida’s Keeping Children Safe Act and the fact that Jacob had a criminal felony conviction for failure to register. Jacob continues to fight for custody and visitation but cannot afford a lawyer because he has been unable to find a job. Now age 26, Jacob was removed from the registry in Michigan in 2011, but remains on the registry in Florida, and his life continues to be defined by an offense he committed at age 11.

***

Jacob’s story is not unique. Throughout the United States, people who commit sex offenses as children (also referred to in this report as “youth sex offenders”) must comply with a complex array of legal requirements that apply to all sex offenders, regardless of age.

Upon release from juvenile detention or prison, youth sex offenders are subject to registration laws that require them to disclose continually updated information including a current photograph, height, weight, age, current address, school attendance, and place of employment. Registrants must periodically update this information so that it remains current in each jurisdiction in which they reside, work, or attend school. Often, the requirement to register lasts for decades and even a lifetime. Although the details about some youth offenders prosecuted in juvenile courts are disclosed only to law enforcement, most states provide these details to the public, often over the Internet, because of community notification laws. Residency restriction laws impose another layer of control, subjecting people convicted of sexual offenses as children to a range of rules about where they may live. Failure to adhere to registration, community notification, or residency restriction laws can lead to a felony conviction for failure to register, with lasting consequences for a young person’s life.

This report challenges the view that registration laws and related restrictions are an appropriate response to sex offenses committed by children. Even acknowledging the considerable harm that youth offenders can cause, these requirements operate as, in effect, continued punishment of the offender. While the law does not formally recognize registration as a punishment, Jacob’s case and those of many other youth sex offenders detailed below illustrate the often devastating impact it has on the youth offenders and their families. And contrary to common public perceptions, the empirical evidence suggests that putting youth offenders on registries does not advance community safety—including because it overburdens law enforcement with large numbers of people to monitor, undifferentiated by their dangerousness.

Human Rights Watch undertook this investigation because we believe the time is right to better understand what it means to be a youth offender raised on the registry. Sex offender laws that trigger registration requirements for children began proliferating in the United States during the late 1980s and early 1990s. They subject youth offenders to registration for crimes ranging from public nudity and touching another child’s genitalia over clothing to very serious violent crimes like rape. Since some of these state laws have been in place for nearly two decades, and the federal law on sex offender registration is coming up on its eighth anniversary, their effects have been reverberating for years.

A Policy Based on a Misconception

Sexual assault is a significant problem in the United States and takes a huge toll on survivors, including children. According to the US Department of Justice (DOJ), there were an estimated 125,910 rapes and sexual assaults in 2009 (the most recent year for which data is available). In an estimated 24,930 of these cases, the victims were between the ages of 12 and 19. The DOJ study did not examine how many of these incidents involved an adult or youth offender. Thus, we do not know how many were similar to the vast majority of the cases investigated for this report—that is, cases of sexual offenses committed by children against another child. Nevertheless, the public and lawmakers have understandable concern, even understandable outrage, about sex crimes. Sex offender registration laws have been put in place to respond to those concerns.

The overlapping systems of sex offender registration, community notification, and residency restrictions were initially designed to help police monitor the “usual suspects”; in other words, to capture the names and addresses of previously convicted adult sex offenders on a list, which could be referred to whenever a new offense was committed. In theory, this was a well-intentioned method to protect children and communities from further instances of sexual assault.

In reality, however, this policy was based on a misconception: that those found guilty of a sex offense are likely to commit new sex offenses. Available research indicates that sex offenders, and particularly people who commit sex offenses as children, are among the least likely to reoffend.

|

Available research indicates that sex offenders, and particularly people who commit sex offenses as children, are among the least likely to reoffend. |

In 2011, the national recidivism rate for all offenses (non-sexual and sexual combined) was 40 percent, whereas the rate was 13 percent for adult sex offenders. Several studies—including one study of a cohort that included 77 percent youth convicted of violent sex offenses—have found a recidivism rate for youth sex offenders of between four and ten percent, and one study in 2010 found the rate to be as low as one percent. These rates are so low that they do not differ significantly from the sex crime rates found among many other (and much larger) groups of children, or even the general public.

A 2006 study of approximately 250 Philadelphia youth sex offenders stated, “[s]ex offending as a juvenile does almost nothing to assist in predicting adult sexual offending.” The study concludes that if the goal of registration is to identify likely future sex offenders, it would be more effective to register youth with five or more contacts with law enforcement for non-sexual offenses than to register youth found guilty or delinquent of a sex offense.

Long-Term Impact on Youth Sex Offenders and Their Families

When first adopted, registration laws neither required nor prohibited inclusion of youth sex offenders. However, by the mid-1990s, many state sex offender registration laws were amended to include children adjudicated delinquent of sex offenses, as well as children tried and convicted of sex offenses in adult court. The resulting policies swept children into a system created to regulate the post-conviction lives of adult sex offenders.

Children accused of sexual offenses were caught at the convergence of two increasingly harsh “tough on crime” policy agendas: one targeting youth accused of violent crimes and the other targeting persons convicted of sexual offenses. In an effort to protect children from sexual assault and hold sex offenders accountable, lawmakers failed to consider that some of the sex offenders they were subjecting to registration were themselves children, in need of policy responses tailored to their specific needs and circumstances.

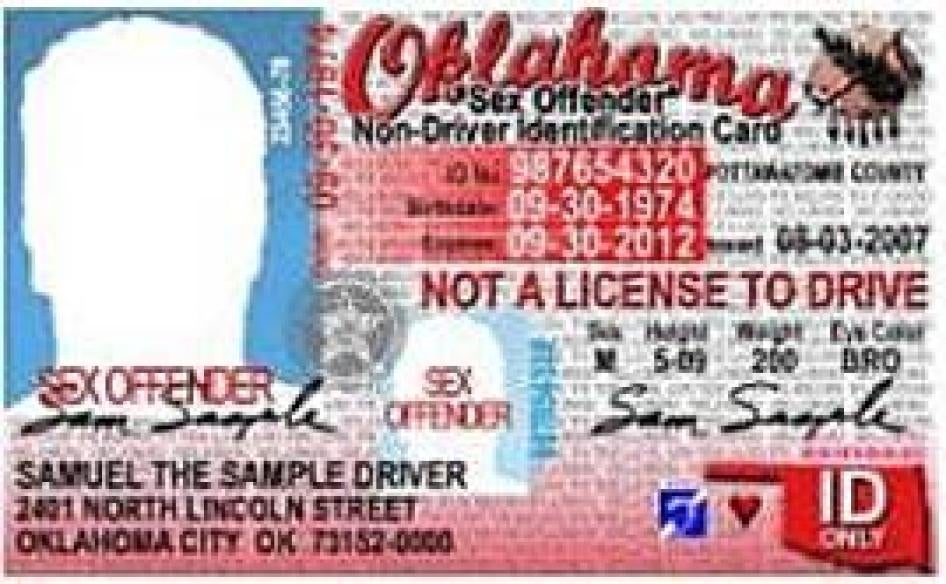

The harm befalling youth sex offenders can be severe. Youth sex offenders on the registry experience severe psychological harm. They are stigmatized, isolated, often depressed. Many consider suicide, and some succeed. They and their families have experienced harassment and physical violence. They are sometimes shot at, beaten, even murdered; many are repeatedly threatened with violence. Some young people have to post signs stating “sex offender lives here” in the windows of their homes; others have to carry drivers’ licenses with “sex offender” printed on them in bright orange capital letters. Youth sex offenders on the registry are sometimes denied access to education because residency restriction laws prevent them from being in or near a school. Youth sex offender registrants despair of ever finding employment, even while they are burdened with mandatory fees that can reach into the hundreds of dollars on an annual basis.

Youth sex offender registrants often cannot find housing that meets residency restriction rules, meaning that they and their families struggle to house themselves and often experience periods of homelessness. Families of youth offenders also confront enormous obstacles in living together as a family—often because registrants are prohibited from living with other children.

Finally, the impacts of being a youth offender subject to registration are multi-generational—affecting the parents, and also the children, of former offenders. The children of youth sex offenders often cannot be dropped off at school by their parent. They may be banned by law from hosting a birthday party involving other children at their home; and they are often harassed and ridiculed by their peers for their parents’ long-past transgressions.

Onerous Restrictions

Some restrictions imposed on the lives of registrants are so onerous and labyrinthine, it is surprising that registrants actually manage to adhere to them. Many do not. The consequences of running afoul of sex offender registration laws can be severe. The crime of “failure to register” is a felony in many states, carrying lengthy prison sentences. The complex rules and regulations that govern the lives of sex offenders on the registry are particularly difficult to navigate when youth offenders, like the majority of those interviewed for this report, first begin registering when they are still children.

Many youth sex offenders never learn that they will have to register until after they accept a plea deal and often after they serve their time in prison or juvenile detention. This is especially likely to be true of children in the juvenile system, where there is no clear legal obligation that they be informed of the consequences of their admissions of guilt. Youth sex offenders are also sometimes subjected to retroactive registration requirements for offenses committed decades in the past—even after years of living safely in the community. Recent laws, like the Adam Walsh Act, reserve the harshest punishments for those who target children. Yet this means that it is often children themselves who experience these harsher penalties, because their crimes almost always involve other kids.

It is unknown how many persons are subject to registration laws in the United States for crimes committed as children. However, in 2011, there were 747,408 sex offender registrants (adult and youth offenders) in the country. What proportion of these people committed sexual offenses as children is impossible to determine from publicly available national data.

Human Rights Watch tried in various ways to obtain this information, but to no avail. We requested data on offenders registered for crimes committed as children from all 50 states. Two states responded with aggregate counts but we were unable to determine the percentage of total registrants these individuals represent. Our attempts to use public registries to obtain counts were stymied by the fact that states and the federal government do not independently track the age of registrants at offense; moreover, state data may undercount the reality. Since the family members of youth sex offenders often must abide by residency restriction laws if they want to live together, the numbers of people in the US affected by these laws is significant.

Faulty Assumptions About Youth Sex Offenders

Faulty assumptions about youth sex offenders’ tendency to recidivate are but one set of flawed assumptions underpinning registration laws. Registering sex offenders and publicizing information about them is predicated on the idea that sex crimes are committed by strangers. However, evidence suggests that about 86 percent of sex offenses are committed by persons known to the victim. According to the Justice Department, 93 percent of sexually abused children are molested by family members, close friends, or acquaintances. Registration will not protect a victim from a family member.

Moreover, early thinking about juvenile sexual offending behavior was based on what was known about adult child molesters, particularly the adult pedophile, under the mistaken belief that a significant portion of them began their offending during childhood. However, more recent clinical models emphasize that this retrospective logic has obscured important motivational, behavioral, and prognostic differences between youth sex offenders and adult sex offenders and has therefore overestimated the role of deviant sexual tendencies in people convicted of sex offenses as children. More current models emphasize the diversity among children who commit sexual offenses, who in the great majority of cases have a favorable prognosis for never reoffending sexually.

Registering youth sex offenders is bad public policy for other reasons, including the fact it overburdens law enforcement with large numbers of people to monitor, undifferentiated by their dangerousness. With thousands of new registrants added each year, law enforcement is stymied in their attempt to focus on the most dangerous offenders. Sex offender registries treat very different types of offenses and offenders in the same way. Instead of using available tools to assess the dangerousness of particular people who commit sex offenses as children, most sex offender laws paint them all with the same brush, irrespective of the variety of offenses they may have committed and in total denial of their profound differences from adults.

Not all states apply sex offender registration law indiscriminately to youth offenders. In Oklahoma, for example, children adjudicated delinquent of sex offenses are treated in a manner more consistent with juvenile sexual offending behavior. There, a child accused of committing a registerable sex offense undergoes a risk evaluation process reviewed by a panel of experts and a juvenile court judge. The preference is for treatment, not registration, and most high-risk youth are placed in treatment programs with registration decisions deferred until they are released, at which point they may no longer be deemed high-risk. The programs and attention provided by the state to high-risk youth means that very few youth are ultimately registered. The few children that are placed on the registry have their information disclosed only to law enforcement, and youth offenders are removed once they reach the age of 21.

Accountability That Fits

The harm that people convicted of sex offenses as children have caused to victims of sexual assault must be acknowledged, and justice often requires punishment. As a human rights organization, Human Rights Watch seeks to prevent sexual violence and to ensure accountability for sexual assaults.

But accountability achieved through punishment should fit both the offense and the offender. Good public policy should deliver measurable protection to the community and measurable benefit to victims. There is little reason to believe that registering people who commit sexual offenses as children delivers either. Under human rights law, youth sex offenders should be treated in a manner that reflects their age and capacity for rehabilitation and respects their rights to family unity, to education, and to be protected from violence. Protecting the community and limiting unnecessary harm to youth sex offenders are not mutually incompatible goals. Instead, they can enhance and reinforce each other.

Human Rights Watch believes that unless and until evidence-based research shows that sex offender registration schemes or other means of monitoring youth sex offenders have real benefits for public safety, persons convicted of sex offenses committed as children should not be subject to registration, community notification, or residency restriction requirements. If some youth offenders are subject to these laws, they should never be automatically placed on registries without undergoing an individualized assessment of their particular needs for treatment and rehabilitation, including a periodic review of the necessity of registration. Society’s goal should be returning them to the community, not ostracizing them to the point that they and their families are banished from any semblance of a normal life.

Methodology

This report is based primarily on an investigation conducted at Human Rights Watch by Soros Senior Justice Advocacy Fellow Nicole Pittman, between September 2011 and early March 2013. Pittman is considered a leading national expert on the application of sex offender registration and notification laws to children. Before joining Human Rights Watch, she worked as an attorney at the Defender Association of Philadelphia, where she specialized in and consulted nationally on child sexual assault cases and registries. Pittman has provided testimony to numerous legislatures, including the US Congress, on the subject.

In this report, in line with international law, the terms “child” and “children” refer to a person or persons below the age of 18. We use the term “youth sex offender” to describe any person who was below the age of 18 at the time they committed the sex offense that led to their placement on a registry, even if they are now an adult. Individuals who were required to register as sex offenders while they were below age 18 are referred to in this report as “youth registrants” or “child registrants.”

In all, we investigated 517 cases of individuals who committed sexual offenses as children across 20 states for this report, including in Delaware, Florida, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Washington. Additional information was collected from Arizona, California, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, South Carolina, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

We conducted in-person interviews with 281 youth sex offenders, as well as immediate family members of another 15, in those 20 states. These 296 in-person interviews form the basis for many of the findings of this report.

Human Rights Watch selected the 20 states because of their geographic diversity and different policy approaches to youth sex offenders. At the time of our research:

- Ten of the 20 research states were deemed to have “substantially implemented” the national Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (Delaware, Florida, Kansas, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina).[2]

- Four of the 20 states did not subject any children found delinquent of sex offenses in juvenile court proceedings (as opposed to criminal court proceedings) to sex offender registration (Georgia, Nevada, New York, and Pennsylvania).

- Ten of the states subjected children found guilty in both juvenile and criminal court proceedings to sex offender registration laws, and had done so since the mid-1990s (Arizona, Delaware, Illinois, Kansas, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, Texas, South Carolina, and Washington). Several of the states had no minimum age of juvenile jurisdiction and had put children as young as eight on their registries.

- The three states with the largest number of registered sex offenders (adults and children) were California (106,216), Texas (68,529), and Florida (57,896).[3]

In addition to our interviews with people placed on sex offender registries for offenses committed as children, we spoke with family members of registrants, defense attorneys, prosecutors, judges, law enforcement officials, academic experts, juvenile justice advocates, mental health professionals, and victims of child-on-child sexual assault. Individuals placed on the registry for offenses committed as adults were not interviewed for this report.

Approximately 95 percent of the youth offenders we interviewed were found delinquent of sex offenses in juvenile court proceedings; less than five percent were convicted in criminal courts. Many of the registrants were subjected to the same sex offender registration, public disclosure, and residency restrictions as adults.

We identified the majority of interviewees through a written request we posted in a bulletin circulated among loved ones of individuals on registries, mental health treatment providers, juvenile advocates, social workers, and defense attorneys. Approximately 100 interviewees were identified by a search of state sex offender registries. In addition to seeking geographic diversity, we sought registrants from an array of locations (including both rural and urban areas) and ethnic and racial backgrounds.

The overwhelming majority of the individuals interviewed for this report started registering when they were children (under age 18). Registrants were between the ages of 14 and 48 at the time we interviewed them. We made a substantial effort to interview registrants of various ages to better assess the impact of being a child or adolescent on the sex offender registry. The majority of the interviews with youth offenders were conducted at their homes. All interviews were conducted in private. A family member or significant other was present for a portion of most of the interviews.

Interviews were semi-structured and covered a range of topics related to how, if at all, being on the sex offender registry affected aspects of a registrant’s life—such as the ability to go to school, obtain and maintain employment, secure housing, and associate with family. Registrants were also asked a series of questions to determine whether the registrant experienced psycho-social harm, felt vulnerable to or experienced violence, or was subject to discrimination because of his or her status as a registrant.

Before each interview, Human Rights Watch informed each interviewee of the purpose of the investigation and the kinds of issues that would be covered, and asked whether they wanted to participate. A parent or guardian gave permission before contact was made with potential interviewees under the age of 18. We informed interviewees that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific questions without consequence. No financial incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed.

Human Rights Watch has disguised with pseudonyms the identities of all interviewees, except in two cases where the degree of publicity surrounding the cases made disguising the identities impossible, and we had the informed consent of the two individuals to use their real names. All documents cited in the report are publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch.

I. Background

Child-on-Child Sexual Violence in the United States

Sexual violence is a serious problem in the United States. According to a US Department of Justice (DOJ) study, an estimated 125,910 rapes and sexual assaults occurred in the United States in 2009 (the most recent year for which data are available).[4] An estimated 24,930 of the victims were between the ages of 12 and 19 at the time of the assaults.[5] The DOJ study did not examine how many of these incidents involved adult or youth offenders.

While 24,930 incidents of sexual violence against children is a disturbing number, it may be an underestimate. Victim fear, shame, or loyalty to the abuser can each contribute to the underreporting of sexual violence.[6] For example, a study by the National Institute of Justice found that only one in five adult women rape victims (19 percent) reported their rapes to police.[7] Failure to disclose sexual abuse is also common among children.

There is evidence, however, that victims today—including child victims—are more likely to disclose abuse, at least to loved ones, than they once were. Dr. Marc Chaffin, an expert and professor of pediatrics at University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, told Human Rights Watch that recent studies suggest that “about half of child victims tell someone.”[8] While this does not necessarily mean more incidents are getting reported to police, it is clear that child victims are more likely to disclose abuse than in decades past.[9]

Historically, the reluctance or inability of survivors of abuse or their family members to report sexual assault crimes has contributed to under-enforcement of the law: the vast majority of sex crimes do not lead to arrests and convictions.[10] A study examining data from 1991 to 1996 found that sexual assaults on child victims were more likely to result in an arrest (29 percent) than were assaults on adults (22 percent), but assaults on children under age six resulted in an arrest in only 19 percent of the cases.[11]

For adults, the emotional and psychological consequences of sexual violence can be profound and enduring and include depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.[12] According to the American Psychological Association, children who have been sexually abused may suffer a range of short- and long-term problems, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, guilt, fear, withdrawal, self-destructive behaviors, and sexual acting out.[13] This study did not differentiate between the experiences of victims who were abused by adults and those abused by other children. According to Dr. Marc Chaffin, who has studied the specific impacts on child victims of child-on-child sexual offenses,

The overarching summary of the research is this—there are a substantial number of victims who recover and are not highly affected beyond a short time. There is a middle group with moderate effects. And there is a group with severe and often lasting effects.[14]

In many cases, the trauma of child sexual abuse is made more complex because the abuse occurs within the family. Denise, a single mother of two boys, Troy (age 15) and Ted (age 12), recalled the day Ted confided in her that he had been sexually abused by Troy: “Ted explained that ‘he had been touched on his private parts’ by his older brother.”[15] Denise continued, “I felt like I had heard the worst thing a mother can hear. I felt confused and shocked. As I listened to Ted, I began feeling everything through him and seeing it through his eyes. I felt so deeply sad for what he had been through, and I battled with feelings of responsibility. What could I have done to prevent this? Why didn’t I see the signs?”[16] Denise immediately began getting help for both her sons and making sure they were both safe from repeating these behaviors. She stated that it,

[B]ecame clear the boys could not be left alone together. At first, it actually felt like things were getting worse not better, especially when Ted confided in me saying, “I lock my bedroom door at night,” as he described how he fears a visit from his brother…. I wish I could explain what it is like to be the parent of both a child who has been abusing and a child who has been victimized. The feelings are so mixed and confusing. I love both my sons, but at times I felt guilty and ashamed that I cared for Troy even though he had hurt Ted.[17]

Child sexual abuse is a complicated form of harm. The effect sexual violence can have on survivors, their family members, and their communities can be harrowing. After a sexual assault, victims may experience a wide range of emotions, such as sadness, anger, fear, shame, guilt, grief, or self-blame; and they may grow up to experience a variety of psychological, social, relationship, and physical difficulties.[18]Not only are victims left to cope with the very personal and intense after-effects of a sexual assault, but they also must deal with the tangible costs associated with the assault, including medical care, counseling, and potential lost wages.[19] In light of all of this, and given the potential consequences for child victims, ending sexual offenses against children is a legitimate priority.

History of Sex Offender Registration and Notification Laws in the US

In part as a result of high-profile cases of sexual abuse in the late 1980s and 1990s, state and federal policymakers passed an array of registration, community notification, and residency restriction laws for individuals convicted of sex offenses.

- Registration refers to a set of procedures that offenders must follow to disclose information to law enforcement authorities and to periodically update or “register” that information so that it remains current.

- Community notification refers to systems by which information about registrants is transmitted to the public or portions of the public.

- Residency restriction laws refer to mostly state and local ordinances that limit registrants’ ability to live in or spend any time in specific locations (such as near a school).

Each state, US territory, and federally-recognized Indian Tribe now has its own set of sex offender registration, notification, and residency restriction laws. Overlaying this diversity is a series of federal laws.

Early Sex Offender Registration and Community Notification Laws

The first federal law addressing sex offender registration, the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act of 1994 (the “Wetterling Act”) established a national database of sex offenders and conditioned states’ receipt of federal anti-crime funds on state compliance with the act.[20] Specifically, it required states to create registries of offenders convicted of sexually violent offenses or crimes against children and to establish heightened registration requirements for highly dangerous sex offenders. States moved quickly to implement federal sex offender legislation, with a majority passing notification and registration statutes for adult sex offenders between 1994 and 1996.[21]

Congress passed its first community notification law in 1996 in response to the abduction and murder of seven-year-old New Jersey resident Megan Kanka.[22] Under Megan’s Law, community notification requirements applied only to individuals identified as “potentially dangerous sex offenders.”[23] Community notification systems proliferated rapidly through a series of amendments to Megan’s Law. Some form of community notification for adult sex offenders has been present in all 50 states and the District of Columbia since 1996.

The Lychner Act, passed in 1996, amended the federal community notification laws, providing for a national database to track sex offenders and subjecting certain offenders to lifetime registration and notification requirements.[24] Both of these laws have been superseded by the 2006 Adam Walsh Act (discussed below).[25]

Incorporation of Youth Sex Offenders in Registration and Notification Laws

When first adopted, federal registration and notification laws neither required nor prohibited inclusion of persons convicted of sex offenses as children (youth sex offenders). But by the mid-1990s, many state sex offender registration laws were drafted to include children adjudicated delinquent of sex offenses as well as children tried and convicted of sex offenses in adult court. The resulting policies swept youth sex offenders into a system created to regulate the post-conviction lives of adult sex offenders.

Youth sex offenders were caught at the convergence of two increasingly harsh “tough on crime” policy agendas: one targeting persons convicted of sexual offenses, and the other targeting youth accused of violent offenses, who were often portrayed at the time as “superpredators”—a notion that has since been discredited.[26] The overheated rhetoric surrounding the issue scared the public, and politicians responded, including with increasingly broad laws affecting youth sex offenders. In an effort to protect children from sexual assault and hold sex offenders accountable, lawmakers failed to fully consider that some of the sex offenders they were targeting were themselves children, in need of policy responses tailored to their specific needs and circumstances.[27]

Today, federal law and the laws of all 50 states require adults to register with law enforcement. Eleven states and the District of Columbia do not register any child offenders adjudicated delinquent in juvenile court. However, these 12 jurisdictions do require registration for children convicted of sex offenses in adult court.[28] Thirty-eight states register both children convicted of sex offenses in adult court and those adjudicated in the juvenile system.[29]

State notification laws establish public access to registry information, primarily by mandating the creation of online registries that provide a former offender’s criminal history, current photograph, current address, and other information such as place of employment. In many states, everyone who is required to register is included on the online registry. In the 50 states and the District of Columbia, adults and children convicted in criminal court are generally subject to public notification, meaning that these individuals are included on the online registry. Children adjudicated delinquent in juvenile court are subject to the same public notification as adults in 27 states, allowing for the disclosure of child offenders’ private information to the public.[30]

A growing number of states and municipalities have also prohibited registered offenders from living within a designated distance (typically 500 to 2,500 feet) of places where children gather, such as schools, playgrounds, and daycare centers.

The Adam Walsh Act’s SORNA

In an effort to standardize the vast and growing number of state sex offender registration systems, Congress passed the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act in 2006.[31] Title I of the Adam Walsh Act, the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA), provides a set of federal guidelines that further expands the breadth of sex offender registration and notification in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the five US territories, and federally-recognized tribal territories. The Adam Walsh Act did not, in its initial draft, specifically address the situation of child offenders. However, an amendment known as the Amie Zyla Provision expanded the scope of the act to include certain juvenile court adjudications in the act’s definition of “conviction” (children convicted in adult court already fell within the definition).[32]

SORNA made several broad changes to existing federal guidelines on sex offender registration that include, but are not limited to:

- Mandating that children register, if prosecuted and convicted as adults or adjudicated delinquent in family court for a sex offense comparable or more serious than “aggravated sexual abuse or sexual abuse.”[33]

- Establishing a new federal and state criminal offense of “failure to register,” punishable by a term of imprisonment.[34]

- Requiring registration for offenses that may not be considered sexual offenses in some jurisdictions, such as indecent exposure, kidnapping, false imprisonment of a child, public urination, rape, incest, indecency with a child by touching, and possession of child pornography.[35]

- Requiring jurisdictions to reclassify the risk level of each sex offender based solely on the crime of conviction or adjudication, with no reference to individualized risk assessment.[36]

To comply with SORNA, jurisdictions must also require registered offenders to keep their information current in each jurisdiction in which they reside, work, or attend school.[37] Jurisdictions that fail to enact the SORNA guidelines risk losing 10 percent of their Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance federal funding.[38]

After the federal government granted several extensions, the deadline to comply with SORNA was July 2011. Five years after the act was signed into law, no jurisdiction has “completely implemented” SORNA, and only 13 have “substantially implemented” the law. On the deadline, several states signaled that they still were unable to implement SORNA.[39] According to a 2013 US Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on the status of SORNA implementation, as of November 2012, 37 of 56 jurisdictions had submitted complete implementation packages for review, and the US Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking (SMART) office had determined that 19 of those jurisdictions (16 states and 3 territories) had substantially implemented SORNA and another 17 had not.[40] The 16 states deemed by the DOJ to have substantially implemented SORNA were Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Wyoming.[41]

An Overbroad Policy of Questionable Effectiveness

Throughout the United States, sex offender registries include offenders convicted for a range of acts, from offensive or vulgar behavior to heinous crimes. Registries create the impression that neighborhoods are thick with recidivist sexual predators, making it impossible for residents, including parents, to discern who actually is dangerous.[42] Sex-offender registries now include not only persons who committed sexually violent offenses or crimes such as kidnapping or false imprisonment of a minor, but also people who have committed offenses like public urination, indecent exposure (such as streaking across a college campus), and other more relatively innocuous offenses. Many people assume that anyone listed on the sex offender registry must be a rapist or a child molester. But most states spread the net much more widely.[43]

Sex offender registration schemes were initially designed to help police monitor the “usual suspects”; that is, to capture the names and addresses of previously convicted adult sex offenders on a list, which could be referred to whenever a new offense was committed. In theory, this was a well-intentioned method to protect children and communities from further instances of sexual assault. In reality, this policy was based on a misconception: that everyone found guilty of a sex offense is a recidivist pedophile. However, according to the National Center on Sexual Behavior of Youth, “most adolescents are not sexual predators nor do they meet the accepted criteria for pedophilia.”[44]

Individuals who commit sexual offenses are not all the same. A one-size-fits-all approach to sex offender registration does not contribute to public safety, especially since, as described further below, the most dangerous offenders are often supervised in the same way as very low-risk offenders who are not likely to commit new sex offenses.

A 2008 report from the Texas Department of Public Safety revealed that the number of registered sex offenders in Texas more than tripled between 1999 and 2008. The 2008 figure was 54,000 offenders, including nearly 7,500 who were placed on the registry for offenses committed as children.[45] Ray Allen, a former chair of the Texas House Corrections Committee who once helped push the tougher sex offender registration bills into law, admitted that he and his colleagues went too far. “We cast the net widely to make sure we got all the sex offenders … it turns out that really only a small percentage of people convicted of sex offenses pose a true danger to the public.”[46]

Does the Registry Prevent Sex Offenses?

Despite the massive growth in the number of registered sex offenders, studies of states that have implemented registration requirements are inconclusive as to whether the registries have any effect on the incidence of reported sex offenses. One study of 10 states with registries concluded that “the results do not offer a clear unidirectional conclusion as to whether sex offender notification laws prevent rapes.”[47] A study in New Jersey found that sex offense rates have been on a consistent downward trend since 1985, with the data showing that the greatest rate of decline in sex offending occurred prior to 1994 (the year registration laws were passed) and the least rate of decline occurred after 1995 (the year registration laws were implemented).[48] There are at least three flaws that help to explain the ineffectiveness of sex offender registries in deterring crime.

First, sex offender registries are focused on preventing recidivism, when instead the focus should be on deterring the first offense from ever happening.[49] The focus on recidivism is misguided because sex offenders are among the least likely to reoffend. Individuals labeled as “sex offenders” have extremely low recidivism rates when compared to persons convicted of robbery, non-sexual assault, burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft, fraud, drug offenses, and public order offenses.[50] The only type of offense with lower recidivism rates is homicide.[51]

As discussed in detail in the following chapter, youth offenders, including youth sex offenders, have even lower rates of recidivism than adults. The emotion provoked by the sexual abuse of a child is powerful—powerful enough to make many overlook the embedded false presumptions and misperceptions about risks of reoffending, especially with regard to children who have committed sexual offenses against other children.[52] But research indicates that these terrible crimes are extremely unlikely to be committed by an individual who was labeled a sex offender as a child.

Second, sex offender registration overburdens law enforcement. Detective Bob Shilling, a 29-year decorated veteran of the Seattle Police Department who spent 20 years as a detective in the Special Victim’s Unit, Sex and Kidnapping Offender Detail, for the Seattle Police, explained how his officers were required to make home visits to registered sex offenders. He stated that focusing attention and resources on an overly broad group of ex-offenders detracts attention from the smaller number of sexually violent offenses that occur, leaving communities vulnerable to sexual abuse, creating a false sense of security, and exhausting valuable resources by tracking the “wrong offenders”—that is, individuals not likely to ever reoffend sexually. The detective said, “the most recent laws dilute the effectiveness of the registry as a public safety tool, by flooding it with thousands of low risk offenders like children, the vast majority of whom will never commit another sex offense.”[53]

Third, registration fails to target resources where they are most needed. Federal guidelines adopted under SORNA risk worsening the problem by mandating that states eliminate the use of risk assessment tools to help identify those offenders who are likely to reoffend. Instead, as noted above, the guidelines require states to use “crime of conviction” as the sole means to classify offenders. Detective Schilling described the focus on crime of conviction “inherently flawed,” because sex offenders differ greatly in their level of impulsiveness, persistence, risk to the community, and desire to change their deviant behavior. Assigning sex offender tiers based on crime of conviction provides very little information about who a sex offender is and what his or her risk for reoffense may be.[54] All of these factors add more nonviolent, lower risk offenders to the registry—including youth offenders. While the sex offender database grows exponentially, funding for monitoring sex offenders is on the decline.[55]

A 2011 review of state sex offender registration legislation applied to child offenders found that only a small number of states were registering child sex offenders based solely upon the type of offense. [56] Most states that included child offenders in pre-SORNA registration schemes also designed safeguards to protect them, such as judicial discretion, consideration of individual circumstances, assessment of risk, or early termination of juvenile registration. The authors of the survey characterized these findings as noteworthy because “the need to comply with SORNA is pushing states in the opposite direction.” [57]

II. Children Are Different

[C]hildren are constitutionally different from adults.… [J]uveniles have diminished culpability and greater prospects for reform … [and] are less deserving of the most severe punishments.… [C]hildren have a lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility … [c]hildren are more vulnerable … to negative influences and outside pressures … [a]nd … a child’s character is not as well formed as an adult’s.

—Miller v. Alabama, United States Supreme Court, 2012 (No. 10‐9646, slip op. at 8 (2012)).

Federal and state laws on sex offender registration and notification fail to take into account relevant—indeed, fundamental—differences between children and adults. These include not only differences in cognitive capacity, which affect their culpability, but also differences in their amenability to rehabilitation, in the nature of their sexual behaviors and offenses and in the likelihood that they will reoffend. Indeed recent laws, like the Adam Walsh Act, reserve the harshest punishments for those who target children without seeming to appreciate that child offenders, whose crimes almost always involve other kids, are particularly likely to be subjected to these harsher penalties. As noted by Berkeley law professor Frank Zimring, “nobody is making policy for 12-year-olds in American legislatures.… What they’re doing is they’re making crime policy and then almost by accident extending those policies to 12-year-olds—with poisonous consequences.”[58]

Cognitive and Developmental Differences

It is axiomatic that children are in the process of growing up, both physically and mentally. Their forming identities make young offenders excellent candidates for rehabilitation—they are far more able than adults to learn new skills, find new values, and re-embark on a better, law-abiding life. Justice is best served when these rehabilitative principles, which are at the core of human rights standards, are at the heart of responses to child sex offending.

Psychological research confirms what every parent knows: children, including teenagers, act more irrationally and immaturely than adults. Adolescent thinking is present-oriented and tends to ignore, discount, or not fully understand future outcomes and implications.[59] Children also have a greater tendency than adults to make decisions based on emotions, such as anger or fear, rather than logic and reason.[60] And stressful situations only heighten the risk that emotion, rather than rational thought, will guide the choices children make.[61] Research has further clarified that the issue is not just the cognitive difference between children and adults, but a difference in “maturity of judgment” stemming from a complex combination of the ability to make good decisions and social and emotional capability.[62]

Neuroscientists are now providing a physiological explanation for the features of childhood that developmental psychologists—as well as parents and teachers—have identified for years.[63] MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) images of the anatomy and function of the brain at different ages and while an individual performs a range of tasks reveal the immaturity of the portions of children’s brains associated with reasoning and emotional equilibrium.[64] It is in large part these developmental and cognitive differences that have caused the US Supreme Court to conclude that juveniles are “categorically less culpable” than adults when they commit offenses.[65]

Moreover, the fact that young people continue to develop into early adulthood suggests that they may be particularly amenable to change.[66] “The reality that juveniles still struggle to define their identity,” noted the US Supreme Court in its 2005 Roper v. Simmons decision, “means it is less supportable to conclude that even a heinous crime committed by a juvenile is evidence of irretrievably depraved character.”[67] Both criminologists and development experts agree that “[f]or most teens, these [risky or illegal] behaviors are fleeting. Only a relatively small proportion of adolescents who experiment in risky or illegal activities develop entrenched patterns of problem behavior that persist into adulthood.”[68]

Child Sexual Misconduct: A Distinct and Varied Set of Behaviors

The image of the adult sexual predator is a poor fit for the vast majority of children who commit sexual offenses. Children are not merely younger versions of adult sexual offenders.[69]

Current science contradicts the theory that children who have committed a sexual offense specialize in sexual crime, nor is there any evidence of the kind of fixed, abnormal sexual preferences that are part of the image of a pedophile.[70] Although those who commit sex offenses against children are often described as “pedophiles” or “predators” and are assumed to be adults, it is important to understand that a substantial portion of these offenses are committed by other youth who do not fit such labels.

Dr. Marc Chaffin, a leading expert on child sexual offending behavior and professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, explains that “early thinking about juvenile sex offenders was based on what was known about adult child molesters, particularly adult pedophiles, given findings that a significant portion of them began their offending during adolescence.” However, current clinical typologies and models suggest that this assessment is flawed.[71] In fact, empirical evidence, as discussed below, shows that if a history of child sexual offending is used to predict a person’s likelihood of future sex offending, that prediction would be wrong more than nine times out of ten.[72]

Compared to adult sexual offending, sexual misconduct by children is generally less aggressive, often more experimental than deviant, and occurs over shorter periods of time.[73] That said, there is considerable diversity in the sexual behaviors that bring children into clinical settings. Child sex offenses range from “sharing pornography with younger children, fondling a child over the clothes, [and] grabbing peers in a sexual way at school, [to] date rape, gang rape, or performing oral, vaginal, or anal sex on a much younger child.”[74] Enormous diversity also exists within the population of children who commit sex offenses.[75] One expert explains that the population includes:

Traumatized young girls reacting to their own sexual victimization; persistently delinquent teens who commit both sexual and nonsexual crimes; otherwise normal early-adolescent boys who are curious about sex and act experimentally but irresponsibly; generally aggressive and violent youth; immature and impulsive youth acting without thinking; so-called Romeo and Juliet cases; those who are indifferent to others and selfishly take what they want; youth misinterpreting what they believed was consent or mutual interest; children imitating actions they have seen in the media; youth ignorant of the law or the potential consequences of their actions; youth attracted to the thrill of rule violation; youth imitating what is normal in their own family or social ecology; depressed or socially isolated teens who turn to younger juveniles as substitutes for age-mates; seriously mentally ill youth; youth responding primarily to peer pressure; youth preoccupied with sex; youth under the influence of drugs and alcohol; youth swept away by the sexual arousal of the moment; or youth with incipient sexual deviancy problems.[76]

Youth sex offenders come from a variety of social and family backgrounds.[77] In some cases, a history of childhood sexual abuse appears to contribute to child sexual offending behavior, but most child sex abuse survivors do not become sex offenders in adolescence or adulthood.[78] Some child offenders have experienced significant adversity, including maltreatment or exposure to physical violence; others have not.

Many of the sexual behaviors of youth are problematic, and need to be addressed in a clinical setting or by the justice system, but placing children who commit sex offenses on a registry—often for life— is going too far.

Recidivism of Youth Sex Offenders

As noted above, there is no scientific foundation for the belief that children who commit sexual offenses pose a danger of future sexual predation.[79] Once detected, most adolescents who have engaged in sexually abusive behavior do not continue to engage in these behaviors.[80] Studies consistently find that adult sex offenses are committed by individuals not known to have been youth sex offenders.[81]

Recidivism rates for youth sex offenders are consistently low. One study that included a cohort composed mostly of youth convicted of violent sex offenses found a recidivism rate of 10 percent.[82] Several studies have found recidivism rates for all youth sex offenders (violent and nonviolent offenses) at between four and seven percent, and one recent study found the rate to be as low as one percent.[83] A meta-analysis that reviewed 63 data sets reporting on the re-offense behavior of 11,219 youth sex offenders found an estimated mean sexual recidivism rate of 7.08 percent across a 5-year follow-up period.[84] These rates should be compared with a 13 percent recidivism rate for adults who commit sexual offenses[85] and a national recidivism rate of 40 percent for all criminal offenses.[86]

A 2007 study by University of California, Berkeley law professor Franklin Zimring found that youth sex offenders have “a low volume of sexual recidivism during their juvenile careers, and an even lower propensity for sexual offenses during young adulthood.”[87] Another study found that when youth sex offenders are re-arrested, it is “far more likely to be for nonsexual crimes such as property or drug offenses than for sex crimes.”[88] One of Zimring’s studies found that youths with five or more arrests for offenses other than sex offenses pose twice the risk of being arrested in adulthood for a sex offense than do youth sex offenders with fewer than five arrests.[89] Given the low rates of recidivism among youth sex offenders, Zimring points out that if the goal of sex offender registration is to compile a list of names of possible future sex offenders, it would be more effective to register youth offenders with five or more contacts with law enforcement for non-sexual offenses as potential future sex offenders than to register youth sex offenders.

III. Who are Youth Sex Offender Registrants?

The enactment across the United States of increasingly comprehensive sex offender registration laws has brought predictable results: the number of individuals (adult and youth offenders) placed on sex offender registries has exploded. In February 2001, approximately 386,000 individuals nationwide were listed on sex offender registries.[90] By 2011, there were 747,408 registered sex offenders in the country.[91]

While it may be safe to assume that the number of registered youth offenders has expanded alongside adult registrants, there are no disaggregated national statistics on youth sex offenders. This chapter therefore contains information Human Rights Watch culled mainly from our interviews with 281 youth sex offenders and the family members of another 15 youth (comprising 296 cases).[92] The interviewees were identified through chain-referral sampling (where attorneys, family members, advocates, and registrants recruit future subjects from among their networks), so the resulting data involves selection bias.[93] Even with that limitation, our interviews provide important insights into the backgrounds of many youth offenders on sex offender registries.

Age

Throughout the United States, children as young as nine years old who are adjudicated delinquent may be subject to sex offender registration laws. For example, in Delaware in 2011, there were approximately 639 children on the sex offender registry, 55 of whom were under the age of 12.[94] In 2010, Michigan counted a total of 3,563 youth offenders adjudicated delinquent on its registry, a figure that does not include Michigan’s youth offenders convicted in adult court.[95] In 2010, Michigan’s youngest registered sex offenders were nine years old.[96] A 2009 Department of Justice study, which focused only on sex crimes committed by children in which other children were the victims, found that one out of eight youth sex offenders committing crimes against other children was younger than 12.[97]

Human Rights Watch recorded several important dates for each of the youth sex offenders interviewed for this report, allowing us to determine their age at conviction and the age they were first placed on the registry. The median age at conviction or adjudication was 15. The median age at first registration was 16. Eight interviewed registrants were age 10 or younger at the time of their conviction and when registration began, with the youngest being 9 years old. A full 84 percent of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch were 17 years old or younger when they began registering.

Offenses

Most jurisdictions mandate registration of children convicted of a wide range of sex offenses in adult court. The federal Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA) expanded the range of sex offenses requiring registration.[98] Notably, it was expanded to include certain sex offenses committed by children adjudicated delinquent in juvenile court.[99] Under the Act, a “sex offense” includes offenses having “an element involving a sexual act or contact with another”;[100] “video voyeurism”; having possession, producing, or distributing child pornography; and “[a]ny conduct that by its nature is a sex offense against a minor.”[101] The “sexual act[s]” or “contact” covered under SORNA include (i) oral-genital or oral-anal contact, (ii) any degree of genital or anal penetration, and (iii) direct genital touching of a child under the age of 16.[102]

Implementation of registration, including the federal SORNA provisions, varies across jurisdictions, resulting in a wide variety of offenses and offenders triggering registration requirements. For example:

- In Kansas, any child convicted of a sex offense in adult court is subject to the same registration requirements as adults. Juveniles adjudicated delinquent for a sex offense in Kansas are also subject to registration for a long list of offenses including rape, indecent liberties with a child, criminal sodomy, indecent solicitation of a child, aggravated incest, electronic solicitation, and unlawful sexual relations. The list also includes attempt or conspiracy to commit the above crimes, criminal solicitation of the crimes, or “any act determined beyond a reasonable doubt to have been sexually motivated.”[103]

- In Arkansas, the courts have discretion to order registration requirements for youth offenders convicted in adult court as well as children adjudicated delinquent for “any offense with an underlying sexually motivated component.”[104]

- Maryland applies registration requirements to youth offenders convicted in adult court, but has different requirements for children adjudicated delinquent.[105]

The following are examples of the wide range of offenses that can trigger registration requirements for youth sex offenders:

- In 2005, in Orange County, California, three boys were convicted of sexually assaulting a 16-year-old girl and videotaping the incident. The crime occurred when one of the boys was 16 and two were 17 years old. All three are subject to sex offender registration requirements.[106]

- In 1997, in Texas, a 12-year-old boy pled guilty to aggravated sexual assault. He inappropriately touched a 7-year-old girl at his babysitter’s house. After completing two years of juvenile probation and therapy, he had to register for ten years. He was finally removed from the registry at age 25.[107]

- In 2004, in Western Pennsylvania, a 15-year-old girl was charged with manufacturing and disseminating child pornography for having taken nude photos of herself and posted them on the internet. She was charged as an adult, and as of 2012 was facing registration for life.[108]

- In March 2010, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, an 18-year-old young man pled guilty to two felony counts of sexual assault and two of indecent assault, which will require him to register. The crimes occurred between October 2003 and December 2008, when the offender was between 11 and 16 years old, and involved multiple rapes of a six- or seven-year old girl and a six-year-old boy.[109]

- In 2006, a 13-year old girl from Ogden, Utah was arrested for rape for having consensual sex with her 12-year-old boyfriend. The young girl, impregnated by her younger boyfriend at the age of 13, was found guilty of violating a state law that prohibits sex with someone under age 14. Her 12-year-old boyfriend was found guilty of violating the same law for engaging in sexual activity with her, as she was also a child under the age of 14 at the time.[110]

- In 2000, in New Jersey, then-12-year-old T.T. inserted a “douche” (feminine product) in his 6-year-old half-brother’s anus on one occasion.[111] When asked why he did it, T.T. responded, “I don’t know.”[112] T.T. subsequently pled guilty to aggravated sexual assault and was sent to a juvenile placement. After incarceration, T.T. was given three years of probation and required to register for life.

- In 1997, Stella A., a 17-year-old high school student, was arrested and pled guilty to sodomy for performing consensual oral sex on a 15-year-old male classmate.[113] Stella was placed on probation and required to register on the state’s sex offender registry. Her photograph, address, and identifying information were publicly available for neighbors and the public to see.

The 296 cases examined for this report had a total of 352 convictions (often due to multiple charges arising from the same incident).[114] For purposes of practicality, we grouped the convictions into 53 offense categories, based on similar offense descriptions. Sexual battery was the most common category of conviction, followed by “lewd lascivious molestation” and “unlawful criminal sexual contact.”

|

Offense Category |

Number of Convictions |

Percentage of Convictions |

|

Sexual Battery |

70 |

7.6% |

|

Lewd Lascivious Molestation |

38 |

4.1% |

|

Unlawful Criminal Sexual Contact |

34 |

3.7% |

|

Sexual Assault |

24 |

2.6% |

|

Aggravated Sexual Assault – Child |

21 |

2.3% |

|

Sexual Abuse |

13 |

1.4% |

|

Rape |

11 |

1.2% |

|

Sodomy |

10 |

1.1% |

|

Sexual Battery (multiple counts) |

10 |

1.1% |

|

Indecency with a child – contact |

10 |

1.1% |

|

There were an additional 111 convictions in 43 other crime categories |

||

|

Total |

352 |

Statutory RapeWhen sexual interactions involve a non-consenting party, the sexual interactions are, by definition, abusive.[115] In these circumstances, the person (adult or child) who forces sex is referred to as the “perpetrator” and the non-consenting person is recognized as a “victim” of sexual abuse.[116] When it comes to child-on-child sexual behavior, the lines between “willingness” and “consent” often become blurred.[117] A child may be “willing” to engage in sexual interactions with a peer, but however willing they may be in one sense, children do not have the psychological capacity to give consent.[118] Therefore, in a state in which the legal age of consent is 14 years old, a 14-year-old female engaging in consensual sexual interactions with her 13-year-old neighbor is a crime. Under many current laws, she could be adjudicated delinquent and required to register as a sex offender. Some children are convicted and required to register after engaging in allegedly consensual sex with other children. These cases, known as statutory rape cases, have received a great deal of press attention and have in some cases led states to reform their laws so that children convicted of statutory rape are not required to register. The intent of sex offender registration and notification laws is to protect children from sexual victimization and exploitation by adults,[119] and it was not the original intent of federal legislators to criminalize sexual interactions between adolescent peers when there is no evidence of coercion.[120] Unfortunately, such criminalization occurs all too frequently. For instance, in Michigan, 17-year-old Alexander D. was convicted of criminal sexual conduct for having sex with his 15-year-old girlfriend.[121] He has been registering as a sex offender since 2003. Alexander and his girlfriend met when they were freshmen in high school and dated for nearly a year before having sex. In Michigan, the legal age of consent is 16.[122] Alexander has been penniless, has lost jobs, and has been called a “pedophile” by passing strangers.[123] His girlfriend’s parents have written letters on his behalf, asking for his removal from the registry. However, Alexander will remain on the sex offender registry until the year 2028. In Florida, an 18-year-old boy, Grayson A., had sex with his 15-year-old girlfriend. The girlfriend, Lily A., became pregnant and the couple got married. Despite their marriage, Grayson was arrested and subsequently convicted of “lewd or lascivious molestation.” Originally charged with rape, Grayson pled no contest to the lewd or lascivious molestation charge.[124] He served two years in prison and was required to register as a sex offender for life.[125] The couple, now ages 31 and 35, have two children together. In a 2009 interview, Grayson stated that he lost at least 17 jobs because of being on the sex offender registry.[126] Because his wife was also his victim, the couple could not live together. Grayson became homeless and ended up living in his car.[127] In 2008, the couple consulted a lawyer to challenge the impact the law was having on their family. In 2009, Attorney General Bill McCollum voted to pardon the conviction and remove Grayson from Florida’s registry.[128] |

Date of Registration, Race, and Gender

States and local jurisdictions have had registration systems in place for more than two decades; however, with the advent of federal efforts to set minimum registration standards in 1994, followed by the passage of Megan’s Law in 1996, more and more youth offenders became subject to registration. With SORNA’s passage in 2006, registrations increased. Among those interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report, the majority were first placed on sex offender registries between 2007 and 2011. Over 60 percent of the interviewees had been registered for five years or less at the time of our interviews with them.

Although there are no national statistics on the race and gender of youth offenders subject to sex offender registration, a 2009 Department of Justice study of youth offenders, examining 2004 data on youth offenders committing sex offenses against other children, found that 93 percent of the offenders were male.[129] The study did not examine the race of the youth offenders or their victims. Among the youth offenders interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report, 96.6 percent were male, 60 percent were white, 31 percent were black, and 5.7 percent were Latino.

IV. Registration of Youth Offenders in Practice

After they have served out their sentences in juvenile detention or prison, youth sex offenders must comply with a complex array of legal requirements applicable to all sex offenders, whether children or adults. Under sex offender registration laws, youth offenders must register with law enforcement, providing their name, home address, place of employment, school address, a current photograph, and other personal information.

Perhaps the most onerous aspects of registration from the perspective of the youth offender are the community notification and residency restriction requirements, which can relegate a youth sex offender who has served their time to the margins of society. Under community notification laws, the police make registration information accessible to the public, typically via the Internet. And under residency restriction laws, youth sex offenders are prohibited from living within a designated distance of places where children gather, such as schools, playgrounds, parks, and even bus stops. These requirements can apply for decades or even a youth offender’s entire life.

Read in isolation, certain sex offender registration requirements may appear reasonable and insignificant to some. It is only once the totality of the requirements, their interrelationship, and their operation in practice are examined that their full impact can be understood.

Community Notification for Youth Offenders

Community notification involves publicizing information about persons on sex offender registries. States and the federal government provide information about sex offenders through publicly accessible websites. Communities are also notified about sex offenders in their area through public meetings, fliers, and newspaper announcements. Some jurisdictions have expanded notification to include highway billboards, postcards, lawn signs, and publicly available and searchable websites produced by private entities. One youth offender told Human Rights Watch, “I have to display a sign in my window that says

‘Sex Offender Lives Here’.”[130]

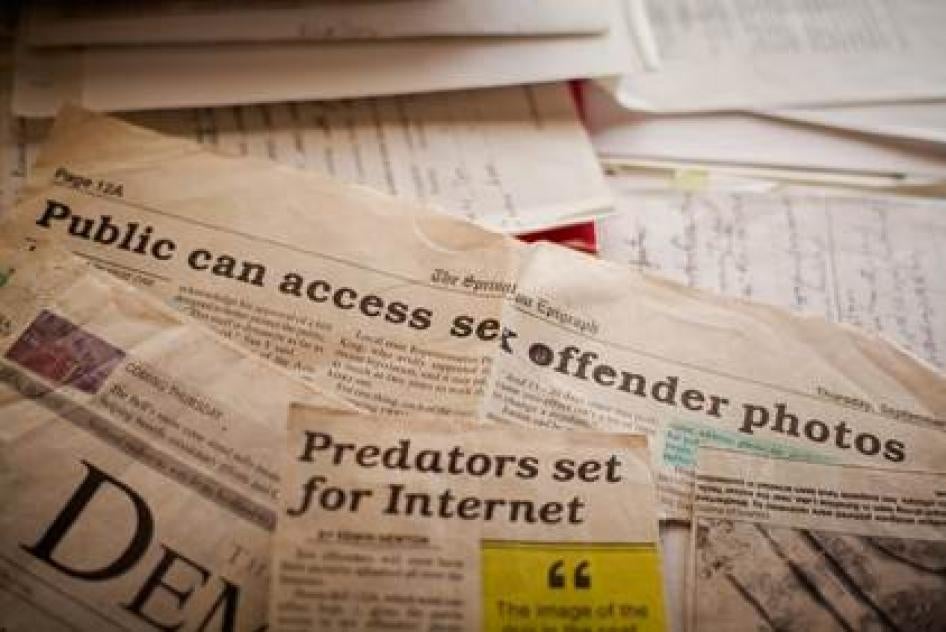

|

A series of newspaper clippings that a father of two sons has collected over the years. The two sons are listed on the public sex offender registry for offenses committed when they were ages 9 and 11, and they were often publicly named in the local newspapers. © 2013 Mariam Dwedar/Human Rights Watch |

Community notification was initially reserved for offenders classified as having a high risk of reoffending. But today, every jurisdiction that registers sex offenders also makes publicly available certain information about them, regardless of individual risk classifications and irrespective of the fact that a registrant was a youth offender.

Community notification, as the term is commonly understood, embraces both the public disclosure of registrants’ information and the disclosure of the information to law enforcement officials only (the latter is often called “non-public” community notification). However, as discussed below, the capacity of states and law enforcement to protect the integrity of “non-public” community notification is eroding.

Public Disclosure of Child Registration Information

With the passage of SORNA in 2006, federal guidelines for community notification became more stringent, requiring that states post on publicly accessible websites the picture, home address, and location of the school and employer of certain categories of sex offenders—whether or not they were juveniles at the time of the offense. The state

websites are linked together via the National Sex Offender Public Website (NSOPW). [131]

Since 2007, the number of states subjecting children to community notification via the internet has grown as jurisdictions passed legislation to come into compliance with SORNA.[132] As noted by one expert, “[t]hat means on many state sex-offender web sites, you can find juveniles’ photos, names and addresses, and in some cases their birth dates and maps to their homes, alongside those of pedophiles and adult rapists.”[133]

The Department of Justice (DOJ) received hundreds of critical public comments about the treatment of children as adults for purposes of public notification.[134] Perhaps as a result, under the Supplemental SORNA Guidelines issued on January 11, 2011, DOJ allowed “jurisdictions to use their discretion to exempt information concerning sex offenders required to register on the basis of a juvenile delinquency adjudication from public Web site posting.”[135] However, as of January 2013, not one state previously deemed in compliance with SORNA went back to amend its laws to exempt children from public disclosure.[136]

As of 2011, most jurisdictions subjected children convicted of sex offenses in adult court to the same community notification regimes as adult sex offenders.[137] Fourteen states apply the same notification standards applied to adults to both children convicted in adult court and children adjudicated delinquent of sex offenses.[138] Other states give judges some discretion over which youth sex offenders are subject to community notification. Some jurisdictions permit youths to petition to be removed after a number of years. In some states, a juvenile adjudicated delinquent has to be 14 to be listed on public sex-offender registries. In others, children may be eligible for public Internet community notification at age 10, 11, or 12.[139] Handling of photographs varies as well by state: some jurisdictions do not post the picture of children unless they reoffend, while others post the image of a child upon their initial registration at ages as young as 9, 10, 12, or 14.

“Non-Public” Notification

Even in jurisdictions requiring disclosure of registry information only to law enforcement agencies (also known as “non-public” disclosure), a child’s information and picture can be, and often is, still disseminated publicly. Members of the public can obtain information on non-public registrants upon request and, with a few clicks of a button, widely disseminate a child’s photograph and personal information.

Youth sex offender registrants interviewed for this report described various ways in which their photographs and personal information were made public even when not posted on official state sex offender registration websites:

- Nicholas T. was placed on the registry at the age of 16 for the attempted rape of a younger neighbor.[140] He stated that “a member of the community made flyers that said ‘Beware – Sex Offender in the Neighborhood.’ The flyers, with my grade school picture, offense, and address, were posted all over the place.”[141]

- “My son, [Max B.], started registering at the age of 10 when he was found guilty of inappropriately touching his 8-year-old sister. The local police assured us that they would allow him to register as a non-public registrant until he turned 12. However, a few months after [Max] went on the registry, the local newspaper ran a Halloween story entitled ‘Know where the Monsters are Hiding,’ warning families to beware of the registered sex offenders in the neighborhood when taking their little ones out to go trick-or-treating. The article listed all the sex offenders in our town. [Max’s] name and address was listed.”[142]

- The police in a small town in Illinois created a “Wall of Shame” containing photographs, names, and addresses of all the registered sex offenders in the area, including child registrants and those deemed low-risk and subject to law-enforcement registration only. People from the town frequently visit the police station to check out the wall of shame.[143]

Official sex offender registration information is also available for purchase or use by private security companies, which sometimes create their own searchable web-based sex offender registries. Companies such as Offendex (also known as The Official Sex Offender Archive©) and HomeFacts (also known as RealtyTrac Holdings, LLC™) transfer all state sex offender registration information, including registrant pictures and addresses, to their websites, iPhone/Droid Android applications, or Facebook, to be searched freely by anyone. These companies appear to take no responsibility for deleting records of persons removed from the registry.[144] The Offendex website indicates that the company distinguishes itself from official government records because it includes “both current and past sex offender records nationwide.”[145] Stating that “[e]ven if the sex offender is not required to register that does not mean the record itself goes away [sic]. The information is still public and available through many court and private databases nationwide.”[146]