“A Long Way from Reconciliation”

Abusive Military Crackdown in Response to Security Threats in Côte d’Ivoire

Maps

Côte d’Ivoire. © 2010 Human Rights Watch

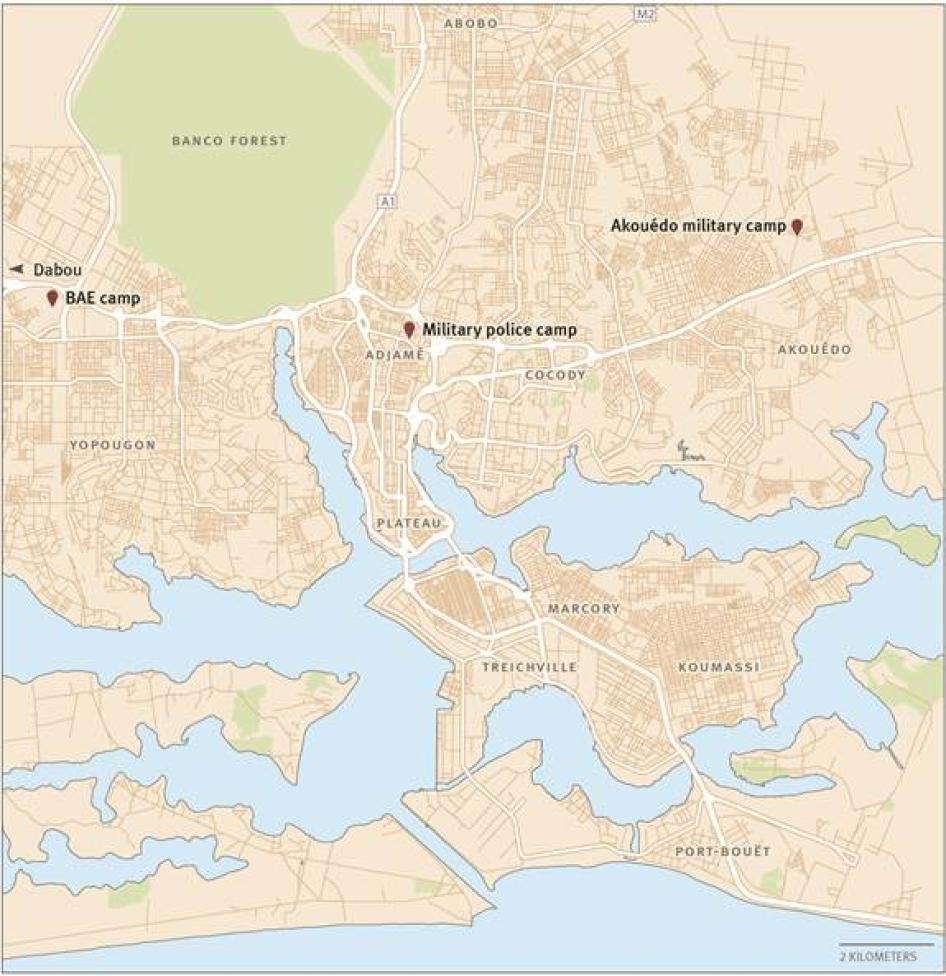

Abidjan. © 2012 Human Rights Watch

Summary

As it emerges from a tumultuous decade of election-related violence and grave human rights abuses, Côte d’Ivoire faces a real threat to its national security. A string of seemingly coordinated and well-organized attacks against the security forces from August through October 2012 followed previous raids along the Liberian-Ivorian border in which civilians were targeted. Since April 2012, at least 50 people, including many civilians, have been killed during these attacks. Thousands more have been driven from their homes. Unfortunately, the state response to the threat, undertaken primarily by the military, has been marked by widespread arbitrary arrests and detentions, detention-related abuses including torture, and criminal behavior against the civilian population.

The month of August saw seven attacks against military installations, highlighted by a deadly raid on one of the most important military bases in the country—in which the attackers made off with a substantial cache of arms. After a brief lull, there were separate attacks in Abidjan and along the Ghanaian-Ivorian border on September 21, leading Ivorian authorities to briefly close the border with Ghana. The border with another of Côte d’Ivoire’s neighbors, Liberia, remains partially closed after a series of cross-border attacks from Liberia into Côte d’Ivoire between July 2011 and June 2012, culminating in a June 8 attack in which seven United Nations peacekeepers and at least ten civilians were killed.

Ivorian authorities have been quick to blame the attacks on militants who remain loyal to former President Laurent Gbagbo, now in The Hague facing charges before the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity. Many of Gbagbo’s military and civilian allies remain in exile in Ghana and Liberia. Previous work by Human Rights Watch showed links between these militants in recruiting and organizing for deadly cross-border raids from Liberia into Côte d’Ivoire. The nature of some of the more recent attacks, combined with additional credible evidence, gives weight to the Ivorian government’s theory that many of the attacks appear to have been waged by pro-Gbagbo militants.

While Côte d’Ivoire faces a legitimate security threat, the Ivorian security forces—and in particular the country’s military, the Republican Forces of Côte d’Ivoire (known as the FRCI, for the French acronym)—have committed a myriad of human rights abuses in responding to these attacks, including mass arbitrary arrests, illegal detention, extortion, cruel and inhuman treatment, and, in some cases, torture. Youth from typically pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups are all too often treated as if, in the words of one person interviewed by Human Rights Watch, they are “all guilty until proven innocent.”

Based on a three week research mission to Côte d’Ivoire in late August and early September 2012, this report focuses primarily on the crackdown by security forces in the Abidjan neighborhood of Yopougon and in the town of Dabou, some 40 kilometers to the west of Abidjan. The majority of the abuses documented occurred at three military camps: the military police base in the Abidjan neighborhood of Adjamé; the former anti-riot brigade (known as the BAE, for its French acronym) base, now controlled by the military, in Yopougon neighborhood; and a military camp in Dabou.

The Republican Forces were created by a decree from President Alassane Ouattara in March 2011, during the height of the post-election crisis, and were then composed primarily of fighters from the Forces Nouvelles rebel group that controlled northern Côte d’Ivoire from 2002 through 2010. After arresting Gbagbo on April 11, the FRCI faced the daunting task of uniting fighters who fought on each side of the post-election conflict, in which at least 3,000 people were killed. The suspicion between the former belligerents remains deep, aggravated by the widespread belief that at least one of the recent attacks had support from individuals within the FRCI still loyal to Gbagbo. The result is minimal progress in fully integrating into the official army the forces that remained under Gbagbo’s command during the crisis. Eighteen months after the conflict’s end, a successful security sector reform appears distant.

Within this context, a measured and professional response to the security threat has been undermined by the concentration of power in the former Forces Nouvelles commanders, including “volunteer” fighters under their command who are not formally part of the Ivorian army. The police and gendarmerie, responsible under Ivorian law for responding to internal security threats, have been largely marginalized; Ivorian officials are quick to point out that Gbagbo stacked these forces with his supporters. The judicial police, who are legally responsible for arresting and interrogating civilian suspects and serving search warrants, played no role in the vast majority of arrests and interrogations documented by Human Rights Watch in the aftermath of the August attacks. Instead, it was the FRCI who almost exclusively undertook neighborhood sweeps, arrests, interrogations, and detentions. They held civilians at sites—namely, military camps—which are not authorized for the detention of any civilian, regardless of the alleged crime.

In the weeks following the August 6 attack on the Akouédo military camp in Abidjan, Ivorian security forces arrested hundreds of people. Some arrests occurred in hot pursuit or based on intelligence, while others occurred in mass sweeps of youth from ethnic groups which had generally supported Gbagbo in the 2010 election.

More than 100 people, including civilians and military men who remained with pro-Gbagbo forces during the crisis, were sent to the military police camp in Adjamé. Many were subjected to severe mistreatment. Human Rights Watch interviewed five victims of torture, who described being beaten brutally as soldiers demanded that they sign confessions or provide “information” about the location of weapons or others allegedly involved in attacks. Several of the torture victims had physical scars from being beaten with belts, clubs, and guns, and displayed severe emotional distress as they articulated their detention experiences. They described seeing tens of other detainees who appeared to have likewise been subject to severe physical mistreatment. Soldiers threatened to rape and kill the wife of one soldier who was detained if he did not confess.

The conditions of confinement at the Adjamé camp also contributed to the inhuman nature of the treatment. A civilian detained at the camp said after interrogators were displeased with his answers, he was thrown into a room that was filled with excrement and forced to spend the night. He said that the punishment was used on a number of occasions. Several former detainees described being held in rooms that were severely overcrowded. One soldier detained after the Akouédo attack described becoming “delirious” between the constant beatings and the almost complete denial of food and water.

Torture as such did not appear to be systematic, as several other former detainees at the Adjamé military police camp described only minimal physical abuse. However, the scale and nature of the abuses indicate that at least some former Forces Nouvelles fighters continue to resort to grave crimes at moments of tension.

Mass arbitrary arrests of perceived pro-Gbagbo supporters occurred almost daily in Yopougon through much of August and in Dabou through at least September 11. Security forces arbitrarily arrested youth in their homes, at maquis (neighborhood restaurants), at bars, in taxis and buses, when walking home from church, and when at traditional community celebrations. Soldiers would often arrive in neighborhoods in military cargo trucks and force 20 or more perceived pro-Gbagbo youth to board. In total, hundreds of young men appear to have been rounded up and detained largely on the basis of their ethnicity and place of residence.

Detainees were frequently subject to beatings during their arrest and when subsequently brought to detention sites—generally unauthorized detention sites, particularly military camps, where civilians were held in violation of Ivorian and international law. Conditions of confinement at these military camps were often inhuman, with detainees packed so tightly in a room that they could not lie down. Former detainees described how they were generally provided no food or water and had to survive by sharing what a few detainees’ family members were able to pass to them via a soldier-guard. Overcrowding was so severe at some sites that, with cells packed full, other detainees routinely spent the night outside in the open air; detainees described soldiers on some nights walking around and kicking or striking with a gun anyone who tried to sleep.

Nearly all of those interviewed said members of the security forces, particularly the FRCI, committed criminal acts. During neighborhood sweeps and mass arrests, soldiers stole cash and valuables such as cell phones, computers, and jewelry from people’s homes. Then, at the various military camps serving as detention sites in and around Abidjan, detainees described how soldiers demanded money—as much as 150,000 CFA (US$300) in some cases—in order to guarantee a person’s release. The victims described a security operation which appeared to degenerate into a lucrative extortion scheme. Several former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they were not even asked for their names, much less questioned; they described simply being held for days in miserable conditions and then forced to pay the soldiers in exchange for their freedom. They complained bitterly about the impact this had on their livelihoods.

Many of the worst abuses associated with the mass arrests occurred under the command of Ousmane Coulibaly, known by his nom de guerre “Bin Laden.” Coulibaly was the commanding officer at the former Yopougon BAE camp from May 2011 through late September 2012, and was also placed in charge of operations in Dabou after the August 15 attack there. In both locations, Human Rights Watch documented widespread arbitrary arrests, frequent inhuman treatment of detainees, and the extortion of money from detainees by soldiers under Coulibaly’s command. In an October 2011 report on the post-election violence, Human Rights Watch named Coulibaly as one of the FRCI leaders under whose command soldiers committed dozens of summary executions and frequent acts of torture during the final battle for Abidjan in April and May 2011. The continued abuses by his forces lay bare the cost of impunity for forces linked to the government.

While high-level government officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch admitted there had been some excesses in the security forces’ response to the August attacks, they stressed that the abuses needed to be seen alongside the gravity of the threat and the determination of the attackers to return the country to conflict. These officials stressed the need to be in solidarity with the military in the face of deadly attacks. The minister of interior and minister of human rights both promised to inspect the military camps identified by Human Rights Watch as marked by abuses and to urge military commanders to respect due process guarantees and to treat detainees humanely. These commitments need to be followed up with investigations by the public prosecutor’s office into cases of torture. Moreover, the Ivorian government should ensure that monitors from Ivorian and international organizations have full access to detention facilities on an ad hoc and unannounced basis.

The Ivorian criminal justice authorities have the responsibility to question, arrest, and detain individuals suspected of involvement in planning, financing, and carrying out attacks on its military. But in resorting to tactics that violate the rights of detainees and appear to target people largely on the basis of their ethnicity and perceived political preference, Ivorian security forces may be fueling the ethnic and political divisions that are at the root of these attacks. These abuses build on the already existing frustration on the part of Ivorian civil society and former Gbagbo supporters that military forces linked to the party in power remain largely above the law. Although armed forces on both sides of the post-election crisis were implicated in grave crimes—including war crimes and likely crimes against humanity—arrests and prosecutions have so far only targeted the Gbagbo camp.

For a decade the former Forces Nouvelles fighters have operated with complete impunity, despite being repeatedly implicated in grave crimes since the 2002-2003 armed conflict. President Ouattara and his government must follow through on their oft-repeated promises of ending impunity and ensure that soldiers engaged in or overseeing torture or inhuman treatment are removed from the military and subject to prosecution.

Victor’s justice and widespread abuses against perceived Gbagbo supporters is not the path to a return to rule of law. It is the path to renewed conflict, with all the grave human rights abuses that have marked the last decade. Ivorian authorities need to recognize the cost of continued impunity and sanction soldiers, regardless of their rank, who are implicated in human rights abuses. As a leader of an Ivorian civil society organization told Human Rights Watch, “Today’s impunity is tomorrow’s crime…. So long as there is impunity for [those linked to the government], there will not be a durable peace.”

Recommendations

To the President, Acting Defense Minister, and Interior Minister

- Ensure a prompt, fair, and transparent investigation into allegations of torture and cruel or inhuman treatment. Put on administrative leave any soldier or law enforcement official against whom there is credible evidence showing that he ordered, carried out, or acquiesced to acts of torture or ill-treatment.

- Direct the Office of the Public Prosecutor to investigate in a thorough, impartial, and prompt manner all torture allegations against law enforcement officials, regardless of rank and whether the victim or family has formally filed a complaint.

- Urgently take steps to permit independent visiting of places of detention by representatives of human rights and humanitarian organizations, lawyers, medical professionals, and members of local bar associations. Ensure complete access to international and Ivorian detention monitors, including the ability to speak confidentially with detainees.

- Cease immediately the holding of civilians at military camps. Ensure that any civilian arrested is promptly brought to a police or gendarme station, even in cases where the military was inappropriately involved in the arrest.

- Ensure that, in accordance with Ivorian and international law, any person arrested appears before a judge within 48 hours to consider the legality of detention and the charges against him or her. Release the person if a specific charge is not presented promptly.

- Ensure that arrests and house searches are done in accordance with Ivorian law and international standards. In particular, ensure that arrests occur in hot pursuit or on the basis of an arrest warrant, rather than in mass sweeps based on a collective suspicion of perceived supporters of the former president.

- Ensure that interrogations only occur at places that the law recognizes as being official locations. Ensure that civilians are only interrogated by the branches of the Interior or Justice Ministries legally authorized to do so, rather than by members of the military.

- Reinstate previously successful measures aimed at ending checkpoint extortion by security forces. Sanction any member of the security forces found to be operating an illegal checkpoint or engaging in extortion.

- Progressively return primary authority in internal security to the police and gendarmerie, including through providing sufficient material support so that these forces can undertake basic security functions. In situations where the military is involved in neighborhood sweeps or patrols, ensure that it is done jointly with the police or gendarmerie, to check potential abuses and to build confidence between the different security forces.

- Routinely provide family members of those in detention with information on where the person is currently being held. If a person is transferred to another detention site, inform the family as quickly as possible.

To the National Assembly

- Ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and implement the Protocol through establishing an independent national body to carry out regular and ad hoc unannounced visits to all places of detention.

To the Ghanaian and Liberian Governments

- Arrest and prosecute or extradite individuals against whom there is an international arrest warrant based on evidence linking the person to grave crimes committed during the post-election crisis or to the recent attacks within Côte d’Ivoire, taking into account the Ivorian authorities’ compliance with the UN Convention against Torture.

To European Union Member States

- In line with the Guidelines to EU Policy towards Third Countries on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, EU member states should, through private démarches and public statements, urge Ivorian authorities to take effective measures against torture and ill-treatment, bring all those responsible for torture and ill-treatment to justice, and provide redress to victims.

- Condition parts of the development aid targeted for security sector reform to the government taking rapid steps to address gaps in compliance with international human rights law regarding detention conditions, particularly torture and inhuman treatment.

To the United States and the UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI)

- Speak out publicly on the Ivorian government’s need to respond to security threats through measures that correspond to international standards on arrests and the treatment of detainees. Stress that continued abuses by security forces against certain populations will only further the divisions that threaten Côte d’Ivoire’s ability to move out of its decade of grave human rights abuses.

- Discuss with the Ivorian government the importance of ensuring complete access at all sites to detention monitors, including for unannounced, ad hoc visits and to speak individually with detainees in a confidential location. In particular, press for the involvement in detention monitoring of Ivorian organizations, several of whom have historically worked extensively on prison conditions.

- Assist the Ivorian government in making it standard practice at all detention sites to keep a full list of those who are or have been detained, and the date on which the lawful authority to detain them expires.

- Condition parts of assistance to the Ivorian government on its taking rapid steps to address gaps in compliance with international human rights law regarding detention conditions, particularly torture and inhuman treatment. For the United States in particular, ensure that no security assistance is provided unless a thorough vetting guarantees that all units meet the requirements of the Leahy Law, including that Ivorian authorities demonstrate the will and capacity to take effective measures to hold accountable soldiers implicated in serious crimes.

- Work closely with the Ivorian, Liberian, and Ghanaian governments to ensure better information sharing, monitoring, and coordination regarding the arrest and prosecution of people implicated in serious crimes during the Ivorian post-election crisis and in the more recent attacks within Côte d’Ivoire.

Methodology

This report is based on a three week research mission to Côte d’Ivoire in late August and early September 2012. The work focused primarily on the crackdown by security forces in the Abidjan neighborhood of Yopougon and in the town of Dabou, some 40 kilometers to the west of Abidjan.

During its field work, Human Rights Watch interviewed 39 people who had been arrested and detained in August or September 2012, as well as another 14 witnesses to mass arrests, beatings, and other abuses. In addition, Human Rights Watch spoke with drivers of commercial and passenger transport vehicles, family members of people still in detention, leaders from Ivorian civil society, representatives of humanitarian organizations, representatives of the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Côte d’Ivoire, and diplomats in Abidjan. In total, Human Rights Watch interviewed 84 people related to the security forces’ response to the August attacks.

Human Rights Watch interviewed victims and witnesses in locations chosen by the interviewees, including their homes, churches, and other sites where they felt secure in speaking openly. Victims were identified through community leaders, neighbors, and other victims. Interviewees were not offered any incentive for speaking with Human Rights Watch, and they were able to end the interview at any time. Human Rights Watch did not request access to the detention sites; the information in this report is based on interviews with individuals who were released from detention. Human Rights Watch has withheld names and identifying information of victims and witnesses in order to protect their privacy and security. Most spoke on the condition of not being identified, as they feared reprisals from the military should it become known that they had spoken with a Human Rights Watch researcher.

The description of events is based on information corroborated through multiple direct sources, particularly victims and eyewitnesses. Before an individual or security force unit was named as responsible for certain crimes, Human Rights Watch ensured that the information was corroborated by multiple independent sources, including victims, witnesses, and other perpetrators involved.

At the end of field research in September, Human Rights Watch shared its principal findings with the Ivorian government, including in meetings with Interior Minister Hamed Bakayoko; and Human Rights Minister Gnénéma Coulibaly. Human Rights Watch appreciates the government’s consistent openness to meetings on human rights issues and welcomes the commitments made by both ministers to investigate and respond to the concerns raised in this report.

Human Rights Watch also wrote to Marcel Amon-Tanoh, chief of staff in the Ivorian presidency, on October 8, detailing the report’s main findings and asking for an official government response (see Annex I). Mr. Amon-Tanoh forwarded the request to the minister of human rights and public liberties (see Annex II), who responded to Human Rights Watch on November 1. Human Rights Watch has incorporated the government’s answers into the report body and has also included the entire response in Annex III.

Background

Eighteen months after the heinous crimes that marked the post-election crisis, Côte d’Ivoire continues to be awash with small arms and to suffer from periodic internal and cross-border attacks on both civilian and military targets. These security threats crystallized in a series of attacks on Ivorian military installations in August 2012, following attacks in western Côte d’Ivoire that originated across the border in Liberia. Côte d’Ivoire’s neighbors to the east and west—Ghana and Liberia, respectively—have often responded inadequately to the presence in their country of people involved in planning and undertaking these attacks. Cooperation has improved in recent months, however, particularly from Liberia.

Post-Election Crisis

After five years of postponing presidential elections, Ivorians went to the polls on November 28, 2010 to vote in a run-off between incumbent President Laurent Gbagbo and former Prime Minister Alassane Ouattara. After the Independent Electoral Commission announced Ouattara the winner with 54.1 percent of the vote—a result certified by the UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI) and endorsed by regional bodies and countries around the world—Gbagbo refused to step down. [1] Six months of violence followed, in which at least 3,000 civilians were killed and more than 150 women raped, often in attacks perpetrated along political, ethnic, and religious lines.

During the first three months of the post-election crisis, the vast majority of abuses were carried out by security forces and militia groups under Gbagbo’s command. [2] Pro-Ouattara forces [3] launched a military offensive in March 2011 to take control of the country and, as the crisis shifted to full-scale armed conflict, they were likewise implicated in atrocities. By conflict’s end in May 2011, both sides had committed war crimes and likely crimes against humanity, as documented by a UN-mandated international commission of inquiry and human rights organizations. [4] In August 2012, a national commission of inquiry created by President Ouattara published a report likewise documenting hundreds of summary executions and other crimes by both sides’ armed forces. [5] Yet, in spite of both forces’ involvement in atrocities against civilians, Ivorian authorities have so far only charged individuals from the Gbagbo camp with crimes related to the post-election crisis—leading to concerns of victor’s justice that will only further the country’s politico-ethnic divisions. [6]

By the end of the conflict, several hundred thousand people had fled to Liberia or Ghana, a majority of whom either supported or were from ethnic groups which largely supported Gbagbo during the 2010 election. As of September 2012, more than 60,000 remained in Liberia and thousands more were in Ghana.[7] Many were refugees who had witnessed or been victim to serious crimes, or had lost their home during the fighting; they fear further abuses by government forces if they return. Others in exile, however, are linked to grave crimes committed by pro-Gbagbo forces during the crisis. The UN Group of Experts on Liberia reported that at least hundreds of pro-Gbagbo militiamen who played an active role in the 2010-2011 violence are among those living in Liberia.[8] A number of people who occupied civilian and military leadership positions under Gbagbo are in Ghana.[9] Some of these pro-Gbagbo militants in Ghana and Liberia now appear determined to use a neighboring country as a base to plot and organize attacks into Côte d’Ivoire.[10]

Ongoing Security Threats

Sporadic attacks along the Liberian-Ivorian border were initially met with tepid response from authorities on both sides of the border. However, a high-profile cross-border attack in which UN peacekeepers were killed, followed by a string of attacks on military installations in and around Abidjan, demonstrated a sophistication and organization among the attackers and prompted swift, but often draconian, measures from Ivorian authorities.

Between July 2011 and April 2012, more than 40 civilians from typically pro-Ouattara ethnic groups were killed during four cross-border attacks from Liberia into Côte d’Ivoire. Based on interviews on both sides of the border, Human Rights Watch documented how the attackers generally crossed in the night, raided a village in targeting perceived Ouattara supporters, and then moved back into Liberia.[11] In April and May 2012, Human Rights Watch interviewed pro-Gbagbo militants in Liberia who admitted to having taken part in these attacks; they also made clear that they were recruiting and mobilizing for additional attacks.[12] On June 8, seven UN peacekeepers from Niger and at least 10 civilians were killed in another cross-border attack, prompting international condemnation and pressure to resolve security threats in the border region.[13] The Ivorian and Liberian militaries, as well as the UN missions in both countries, reinforced their presence and patrols in the area.[14]

Blood remains on the floor of the Akouédo military base, where six Ivorian soldiers were killed during an August 6 raid. Pro-Gbagbo militants were alleged to be responsible, with support from soldiers inside the camp. © SIA KAMBOU/AFP/GettyImages

Soldiers from the Republican Forces patrol Dabou on August 16, 2012, following an attack on an army base, a prison, and a police station the previous night. Progress in security sector reform remains minimal, and many soldiers continue to conduct policing functions. © SIA KAMBOU/AFP/GettyImages

After more than a year of raids confined mostly to Côte d’Ivoire’s western border, a string of attacks on military installations throughout the country in early August indicated a broader and more complicated security threat. Early on August 5, a small military post and a police station were attacked in the Abidjan neighborhood of Yopougon. At least five soldiers were killed. Around the same time, a military base in the town of Abengourou, near the Ghanaian border, likewise came under gunfire.[15] One day later, attackers launched their most ambitious assault yet—against one of the largest military camps in Abidjan, known as Akouédo. At least six soldiers were killed, and the attackers made off with a substantial cache of weapons from the camp’s armory.[16] The ease with which the attackers entered the camp and had access to the armory made it very likely that there was assistance from soldiers within the camp, a fact widely recognized by government officials, diplomats, UN representatives, journalists, and others in Côte d’Ivoire.[17]

Several more attacks against military posts followed in subsequent days, including on August 7 near the town of Agboville, 80 kilometers to the north of Abidjan; on August 13 near Toulepleu, near the Liberian border; and on the night of August 15 in Dabou, some 40 kilometers to the west of Abidjan. A prison was also broken into during the Dabou attack, leading to the evasion of all those detained.[18] Around 20 people, including at least a dozen Ivorian soldiers, were killed during the course of seven August attacks.[19]

The wave of attacks led to the re-militarization of Abidjan, with ubiquitous roadblocks and military patrols, particularly in the longtime pro-Gbagbo neighborhood of Yopougon. Concern about further attacks was still palpable when Human Rights Watch arrived on August 25. The tension was further fueled by the hyper-partisan and rumor-filled stories common in the Ivorian press. The military presence and fear among the population gradually declined, though continued to exist, during the three weeks Human Rights Watch was in Abidjan.

Immediately after the Akouédo attack, the Ouattara government said that pro-Gbagbo militants were responsible. Interior Minister Hamed Bakayoko indicated that the attacks in Abidjan and the attacks in western Côte d’Ivoire, such as the one during which the UN peacekeepers were killed, were linked—with oversight and organization by hard-line Gbagbo supporters currently in Ghana.[20] The leadership in Côte d’Ivoire of Gbagbo’s Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) denied the accusations and denounced the August attacks.[21] Several analysts suggested that the August attacks could be linked to discontent among the tens of thousands of youth who fought with pro-Ouattara forces during the crisis, retain their guns, and now feel forgotten as disarmament, demobilization, and reinsertion (DDR) creeps forward at a snail’s pace.[22] Analysts positing this theory, however, generally saw pro-Gbagbo militants as the more likely attackers, or saw the two potentially destabilizing issues occurring simultaneously.[23]

Although the precise details of the August attacks remain unclear, Human Rights Watch has documented clear connections between pro-Gbagbo militants in Liberia and Ghana—and coordinated efforts to plan and carry out attacks in Côte d’Ivoire.[24] The UN Group of Experts on Côte d’Ivoire reported similarly in an October 15, 2012 report, stating that “military actions that have been conducted since early 2012 in Côte d’Ivoire were planned in Ghanaian territory, funds were transferred from Ghana to Liberia (physically or via bank transfers) and recruitment took place in Liberia.”[25] Among those against whom there is credible evidence of involvement in financing or planning attacks are a number of military and civilian leaders from the Gbagbo regime who are subject to Ivorian and international arrest warrants, as well as European Union sanctions.[26] Yet, until the August attacks, most appeared to live in neighboring countries, particularly Ghana, without fear of arrest and extradition to Côte d’Ivoire.

Liberian, Ghanaian Response

For more than a year after the end of the post-election crisis, Liberian authorities were slow and ineffective in responding to the flood of pro-Gbagbo militiamen and Liberian mercenaries—many implicated in grave crimes—who crossed into Liberia. Several high-profile Liberian mercenaries responsible for serious international crimes during Côte d’Ivoire’s post-election crisis were quietly released after an initial arrest, and the militants steadily recruited and mobilized along the border without effective response from Liberian authorities.[27] After the June 8 attack, however, Liberian authorities took steps toward monitoring their territory and finding those suspected of involvement in cross-border attacks against civilians. On June 14, Liberia’s information minister announced that the country’s National Security Council had ordered the arrest of 10 Liberians and Ivorians potentially connected to attacks along the Liberian-Ivorian border. Liberian authorities also announced the closure of its border with Côte d’Ivoire, the deployment of additional military forces to the area, and the suspension of artisanal gold mining near the border due to its possible role in funding armed groups.[28] A hearing was held that led to the June 23 extradition of 41 Ivorians detained in Liberia in connection with post-election crimes in Côte d’Ivoire.[29]

In July, Liberian authorities made additional arrests related to the UN peacekeeper attack. On August 30, seven of those arrested appeared before a Monrovia court to hear charges against them related to cross-border attacks.[30] Then on October 18, Liberian authorities announced the arrest of Bobby Sarpee, whose name was referenced as involved in recruitment and attacks by people interviewed by Human Rights Watch along the border in April and May.[31] Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf met with President Ouattara in Abidjan the same day, and the two signed an agreement that pledged, among other things, joint military action along the border before the end of 2012.[32] In Human Rights Watch’s meetings with Ivorian government officials in Abidjan, there was generally praise for the current cooperation between Liberian and Ivorian authorities in responding to the border threats.[33]

Human Rights Watch remains concerned about Liberian authorities’ inability or unwillingness to prosecute several Liberian mercenaries who have been implicated in serious international crimes in Côte d’Ivoire.[34] Key among this group is Isaac Chegbo, better known as “Bob Marley,” who was released on bail in February 2012 without the knowledge of the prosecutor in charge of the case.[35] No progress in prosecuting the case is apparent, despite, as reported by a UN Panel of Experts, that Chegbo admitted to Liberian authorities that he had been involved in mercenary activities in Côte d’Ivoire—a serious crime under Liberian law.[36] During the post-election crisis, forces under Chegbo’s command were involved in at least two massacres in western Côte d’Ivoire in which more than 100 people were killed on the basis of the ethnicity or nationality.[37] After Chegbo was granted bail, the UN Panel of Experts on Liberia reported receiving information “that Chegbo attended meetings among Liberian mercenaries in Grand Gedeh County … to discuss and plan cross-border attacks into Côte d’Ivoire.”[38]

The praise for Liberian authorities was in marked contrast to the frustration Ivorian officials expressed for the lack of cooperation from the Ghanian government. Many key civilian and military leaders close to Gbagbo—along with at least hundreds of pro-Gbagbo militiamen and soldiers—crossed into Ghana at the end of the post-election crisis. By mid-2011, Ivorian authorities had issued around two dozen international arrest warrants, most of them against individuals believed to be in Ghana.[39] Many of those subject to an extradition request were credibly implicated in grave crimes during the post-election crisis; seven remain on the European Union’s financial sanctions list, in part for their alleged continued threat to Côte d’Ivoire’s stability.[40] Yet prior to the August 2012 attacks in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghanaian authorities had not acted on any of the warrants. Togo extradited one of Gbagbo’s former defense ministers, Moise Lida Kouassi, in June 2012.[41]

After the attacks in Côte d’Ivoire in early August, there were signs of better cooperation from Ghana. The attacks closely followed the July 24 death of Ghanaian President John Atta Mills, who was widely seen as close to Gbagbo and protective of Gbagbo’s allies who crossed into Ghana. On August 24, Ghanaian authorities arrested Justin Koné Katinan, Gbagbo’s budget minister during the crisis, after he returned from South Africa.[42] Katinan’s arrest warrant originally related to economic crimes committed during the post-election crisis.[43] Ivorian officials also believe he is involved in financing efforts to attack and destabilize in Côte d’Ivoire.[44] Katinan’s extradition hearing in Ghana has been repeatedly delayed.[45]

During a visit to Côte d’Ivoire in early September, interim President John Mahama, who took power after President Atta Mills’ death, promised that Ghana would not serve as a “rear base” for threats to Côte d’Ivoire’s security.[46] On September 14, Ghanaian authorities arrested three men attempting to buy weapons who, according to a deputy police commissioner cited by Reuters, “admitted they were mobilizing arms to overthrow” the Ouattara government.[47]

Only one week later, early on September 21, armed men appear to have crossed from Ghana into Côte d’Ivoire to carry out an attack on an Ivorian military post in Noé, near the Ghanaian border.[48] The night before, two new attacks had been launched in the Abidjan neighborhoods of Port-Bouët and Vridi, with three people killed.[49] The Ivorian government responded to the Noé attack by closing its land, air, and sea borders with Ghana,[50] though quickly reopened air traffic.[51] Land and sea borders reopened on October 8.[52]

A new round of seemingly coordinated attacks occurred early in the morning of October 15, when armed men near simultaneously attacked an electrical power station in Yopougon and a police station and gendarmerie in Bonoua, a town around 60 kilometers to the east of Abidjan.[53]

Better regional cooperation on arrests, prosecution, and extradition is crucial both to provide justice for the grave post-election crimes and to address threats to regional security. It is likewise essential that Ivorian authorities ensure that accountability occurs through fair trials and within the confines of international and Ivorian law. The military’s response to the August attacks instead shows that they are resorting to practices akin to those that marred the post-election crisis—namely, human rights abuses that stem from assigning collective guilt to certain ethnic groups, and particularly young males from those ethnic groups, that tend to support Gbagbo.

I. Torture, Mistreatment, Inhuman Conditions at the Adjamé Military Police Camp

Even now, I haven’t found myself. I wake up at night and think that I’m still in the cell, that I’m still being questioned and beaten.

—Soldier detained at Adjamé military police camp, August 2012[54]

In the aftermath of the early August attacks, in particular the August 6 attack on the Akouédo military camp, Ivorian security forces arrested hundreds of young men alleged to have been involved in or have knowledge about the attacks. More than 100 of those arrested were detained at the Adjamé military police base, under the command of the former Forces Nouvelles commander Koné Zakaria.[55] The military police was reactivated by President Ouattara in December 2011 and tasked primarily with tracking down “fake” members of the Republican Forces—in effect, fighters who were not to be incorporated into the army but yet remained armed and active in security functions.[56] While the military police base may have been an appropriate place to question and detain soldiers believed to have been involved in the attacks,[57] many of those held there were civilians—in contravention of Ivorian and international law.

Human Rights Watch interviewed eight former detainees at the military police camp, five of whom provided detailed evidence suggesting that they had been victims of torture. They described how military personnel subjected them to beatings, flogging, and other extreme forms of physical mistreatment generally with the purpose of demanding answers to questions about the location of guns or alleged suspects, or in order to pressure the detainee to sign a confession of involvement in an attack against state security. Many former detainees described experiencing severe physical injuries, including one who, a week after his release, continued to have blood in his urine from the beatings. They also described seeing other detainees come back to the cell with bruised faces, severe swelling, and open wounds.

Detainees at the military police camp also described suffering grossly inadequate detention conditions, including severe overcrowding, near complete denial of food and water, and humiliating practices like being placed in a room filled with excrement. Many were forced to pay the soldiers guarding them to secure their release.

The former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch were all young men from ethnic groups perceived to support Laurent Gbagbo. They described their detention rooms as being full with people from the same ethnic groups, including the Bété, Guéré, Ebrié, Oubi, and Adioukrou—though, if the government is correct in stating that pro-Gbagbo militants carried out the attacks, the ethnic breakdown of detainees is perhaps unsurprising. According to former detainees as well as representatives from international organizations who have monitored the government’s response to the August attacks, some of those arrested were picked up in the immediate aftermath of the specific attacks, as security forces pursued the attackers. Others were arrested based on some measure of evidence, for example a neighbor saying that the person had housed militiamen. Finally, many young men were picked up during mass arrests in areas with a concentration of perceived Gbagbo supporters (the mass arrests will be discussed in Chapter II).

Once in detention at the military police base in Adjamé, many individuals were held for extended periods without being charged or appearing before a judge. Ivorian law stipulates that a civilian should be charged or released within 48 hours of being arrested or detained.[58] Military personnel are likewise to be brought before the competent judicial authority within 48 hours.[59] Yet one former detainee at the Adjamé camp was held and routinely beaten for two weeks before being released without charges; another was held and beaten for more than 20 days before being released without charges. Detentions of at least a week without being charged or appearing before a judge were common.

Human Rights Watch wrote the Ivorian government on October 8 requesting an official response to the main findings from our field work (see Annex I). In responding to a question on prolonged detention without appearing before a judge, Ivorian Minister of Human Rights and Public Liberties Gnénéma Coulibaly wrote:

The slowness documented in the judicial procedures predates the current government. For several decades there has been an obstruction of the courts, too much rigidity in the Penal Code in the face of evolutions in Ivorian society, and, above all, a lack of resources given to judges—all of which has made it difficult, at present, to strictly respect the period for appearing before a judge for all detainees.

Moreover, the gravity of the crimes that those arrested have been implicated in demands that the investigations are done thoroughly, which requires some time.[60]

Human Rights Watch agrees that previous governments in Côte d’Ivoire likewise failed to respect Ivorian and international human rights law regarding detainees’ right to a prompt appearance before a judge in order to hear the charges against them. However, abuses that occurred under the Gbagbo government should be avoided, not replicated, in restoring the rule of law. The minister’s response also seems to overstate the difficulty of meeting this requirement. It does not demand a trial within 48 hours, but merely that there should be sufficient evidence to keep a person in detention and that the person be informed of the charges against him or her. People are innocent until proven guilty under Ivorian and human rights law, and should not be held in confinement when authorities are unable to gather sufficient evidence linking the person to a crime grave enough to warrant pre-trial detention. The apparent lack of individualized evidence that authorities relied on during the mass roundups makes this all the more urgent.

Mr. Coulibaly also responded to a question on the legal basis for detaining civilians in military camps, including the Adjamé military police camp and two other military camps discussed in Chapter II of this report. The minister justified the practice in part on account of prison escapes that had occurred at two of the main prison facilities in and around Abidjan prior to and during the period of the August attacks. He continued:

In the face of these events, although the law states that preventative detentions are to occur in prisons, it was inconceivable to detain individuals suspected of involvement in attacks against state security without taking a minimum of precautions. The military sites were at that point the most secure places to avoid likely escapes.

In addition, it is important to note that we are not speaking of ordinary citizens, but combatants and militiamen who do not hesitate to kill Ivorian soldiers in cold blood. Whatever the cause, the Ivorian government is working to find solutions to these problems by renovating the prisons.[61]

Human Rights Watch welcomes the government’s commitment to renovate the prisons and use them as the sole detention sites going forward, as stipulated under Ivorian law. However, Human Rights Watch is concerned with the rest of the government’s response to the question on detaining civilians in military camps. Although a serious security threat may exist, this is not a situation of armed conflict and international humanitarian law does not apply—meaning that normal rules on the use of force in policing situations apply, and the attackers cannot be considered “combatants” under humanitarian law.

Moreover, as described above and detailed more fully in the next chapter, the vast majority of individuals detained were arrested in mass sweeps—neither in hot pursuit after attacks nor on the basis of individualized suspicion connecting a person to specific attacks. Human Rights Watch is concerned by the government’s apparent characterization of all the dozens of young men rounded up en masse in August as combatants or militiamen. This characterization supports the contention of pro-Gbagbo youth that they are treated as guilty, or as militiamen, until proven otherwise, rather than the other way around.

Regarding the minister’s assertion that prison escapes made military camps necessary as detention sites, it is disingenuous at best to pretend that all of those detained in August were high-profile suspects. The vast majority of former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch merely belonged to ethnic groups perceived as pro-Gbagbo and found themselves in the wrong place—namely Yopougon neighborhood—at the wrong time. The fact that hundreds of these young men were released further calls into question the minister’s statement that it was “inconceivable” to hold them in legally authorized detention sites. For those detained less than 48 hours, police or gendarme stations would have worked adequately; for those detained longer, the main Abidjan prison continued to house detainees during this period. More fundamentally, the military has no role under Ivorian law in arresting, questioning, or detaining civilians.

Torture and Inhuman Treatment

Of particular concern at the Adjamé military police base was the physical mistreatment of detainees that, in some cases, appeared to reach the level of torture. Torture is defined under the Convention against Torture as:

any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed … when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.[62]

In the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, severe physical pain appeared to be inflicted by state agents, namely military personnel, in order to pressure people into a confession or to divulge information about the location of weapons. Torture did not appear to be systematic, as other detainees described only minimal physical abuse. However, the cases documented by Human Rights Watch raise concerns about the total number of potential victims.

Three of the five torture victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch were civilians who, according to Ivorian and international law, should not be detained at the military camp. A 36-year-old civilian described his arrest and detention at the Adjamé military camp, which included the infliction of severe physical pain in an attempt to extract information:

Several weeks ago [around August 20], I was leaving Adzopé around 7:30 p.m. It was too late to take a minibus, so I got aboard a big [commercial transport] truck. When passing through the corridor of Anyama to enter N’Dotré, the FRCI had a checkpoint there and stopped the truck. They said that I was a militiaman, that’s why I was in a transport truck and not a minibus or Gbaka. They immediately started hitting me, saying that I was hiding a gun…. They put me in a 4x4 and took me to the Adjamé military base, [Koné] Zakaria’s [the head of the military police] base. They put me in a cell there. There were four rooms that I saw where they were holding people, but it’s a big camp, there could have been other cells. We were about 20 in each of those cells….

I was there for a week, and they questioned me every day but the last one. Each day they pulled me out and took me to another room for questioning. They would say, “We know you’re a militiaman, and that you’re hiding guns in the bush. You’re trying to destroy the country. Where are your guns?” They’d demand this over and over, “Where are your guns hidden?” And when I’d say that I didn’t know, that I didn’t have any guns, they’d strike me. They’d strike me over and over, hard. “Where are the guns?” “I don’t own a gun, I’ve never held a gun.” Whack! They’d wrap their belt around their hand and hit me in the head, the face, the side. The metal [ring] of the belt was on the end they hit you with, [I think] to inflict the most pain. It wore me out…. I had a lot of wounds, from when they’d strike you just right with the metal ring. Other people in my cell also had wounds—people would come back with swollen faces, bleeding from open wounds. The interrogations would last about 30 minutes, and after enough times of saying you didn’t know anything, and getting hit, they’d take you back to the cell.

After a week of beating me, they said that I had to pay 100,000 CFA ($200) or I would be sent elsewhere and killed. I used one of their phones to call my parents, who brought the money to get me out.[63]

Another civilian detainee informed Human Rights Watch that he suffered similar physical mistreatment as his military interrogators demanded he provide information about the whereabouts of specific individuals the interrogators alleged to have been involved in carrying out or supporting the attacks. He also described hearing fellow detainees scream out in pain from nearby interrogation rooms, wondering if others suffered even worse cruelty.[64]

Two of the torture victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch were soldiers still formally in the Ivorian military, but who were from typically pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups and had remained in Gbagbo’s security forces (often called ex-FANCI, for the former army name, Forces Armées Nationales de Côte d’Ivoire) during the post-election crisis. Both were arrested within two days of the Akouédo attack. Although specific details have been omitted to protect his identity, one such soldier, who appeared severely distressed when interviewed by Human Rights Watch several days after his release, described:

I was beaten repeatedly. They were trying to get me to sign a confession, saying that I [had played a role in the attacks]. They would put the paper in front of me, telling me to sign it. And when I refused, they’d beat me. They beat me with clubs, with their belts, with fists…. A couple days they were particularly rough. During one questioning, one guy took the back of his Kalash[nikov] and kept slamming it into my [leg bone]. It hurt so bad that I thought it was broken…. A couple of them would say things like, “You the old military men, we’re going to be finished with all of you.”

We were held in a little building inside the camp without any light. There was just a small hole we could see out. People were sleeping on top of each other, or sitting up because there wasn’t room…. We got a small thing of bread every two days. And they would toss in a couple one-and-a-half liter bottles of water, and all of us in the room—at least 50 people—would have to share it. We got so hungry and thirsty…. One day we saw the Red Cross come. We could see their people, but they weren’t allowed to speak to us.

Later it was the gendarmes who questioned me. They didn’t rough you up like [the FRCI], they just asked questions. [I think] they decided I wasn’t involved, because the questioning stopped after a couple days with them. But I did more than three weeks in detention before being released.

I became delirious from the beatings, the lack of food and water…. Even now, I haven’t found myself. I wake up at night and think that I’m still in the cell, that I’m still being questioned and beaten. I bleed sometimes when I [go to the bathroom]. And the worst wounds are inside, in my head…. I don’t know what to do, I’m free now, but I feel like I could be picked up again at any moment. All of us who aren’t ex-FN [Forces Nouvelles], who are from certain [perceived pro-Gbagbo] ethnic groups, that’s who they’re going after. They don’t trust us.[65]

Of those detained in the same ad hoc cell as the soldier, he said there were both civilians and military men—but that the civilians were more numerous than the military. He indicated that some people were taken out for questioning more than others and that he was one of the most frequently questioned. He described other detainees coming back after questioning with bruised faces, swelling throughout their body, and in extreme pain.[66]

Another soldier who had been in Gbagbo’s military during the war described similar physical mistreatment following his arrest in the days after the Akouédo attack. Moreover, he said that during several interrogations the military police in charge of his questioning threatened to rape and kill his wife if he did not confess to supporting those trying to attack Côte d’Ivoire. He was ultimately released after more than 10 days in detention.[67]

In addition to the severe physical abuse, several detainees described inhuman and degrading conditions of confinement. A civilian described how soldiers used a specific cell to further punish certain detainees:

One of the cells was used for people to piss and shit. It was the only room with a hole for a toilet, but there were so many of us that soon the whole room was just covered with urine and shit. One day, I guess [the soldiers who interrogated me] decided they didn’t like my answers. I think it was the second day. At the end of questioning, they put me in the toilet room; there were a couple other people in there already. The smell was horrible, and I had open wounds from being beaten. You couldn’t sit anywhere without being in [excrement]…. They did this to people every day, it only happened to me once. If they weren’t happy with your answers, or thought you were acting up, they threw you in the shit room for hours, sometimes all night…. By the time I was released, I’d developed these skin infections [seen by Human Rights Watch, though the cause could not be confirmed] on my arm and leg.[68]

Human Rights Watch also interviewed several family members of people who had been held at the Adjamé military camp prior to a transfer to another detention facility. The family members had been able to speak with the detainee at a new facility (either the Plateau police station or the main Abidjan prison, known as MACA), and reported descriptions of severe physical abuse prior to the transfer.[69] A sister who had recently visited her brother at the MACA reported that he remained bruised and swollen in the face, saying he described being struck repeatedly above the ear with the back of soldiers’ guns. She told Human Rights Watch that her brother had spent several days at the MACA infirmary to recover from his mistreatment.[70] Human Rights Watch was not able to interview the victim directly to confirm the story of abuse and where it took place, as he remained in detention.

Other detainees at the military police camp did not report torture. Human Rights Watch interviewed three former detainees at the military camp who described experiencing only minimal physical abuse. They were forced to pay money for their release, similar to what is described in the following chapter on mass arrests.

The commander of the military police and the military camp in Adjamé is Koné Zakaria—a longtime Forces Nouvelles commander and one of the most powerful military leaders in Côte d’Ivoire. None of the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that Zakaria himself was involved in his mistreatment. Only one of the detainees said that they ever saw Zakaria personally at the camp, and it was through an eyehole in the detainee’s cell.[71] However, even if not directly overseeing torture and other inhuman treatment at the Adjamé military camp, Zakaria is the commander in charge of the camp and of the soldiers in his military police unit who are based at the camp. Moreover, given the large number of detainees held at his camp, the length of some people’s detention there, and the pervasive nature of the abuses, it is likely that Zakaria knew or should have known about the mistreatment. Military commanders have a responsibility to take reasonable and necessary steps to prevent abuses by those under their command and to punish those responsible for abuses.[72]

In addition, Human Rights Watch received credible information about recent cases of torture against detainees held in a Republican Forces military base in San Pedro, a town in southwestern Côte d’Ivoire about 350 kilometers from Abidjan.[73] On October 4, the Associated Press reported that soldiers at the San Pedro military camp had subjected at least four civilian detainees to electric shock, finding that “long wires were attached to their feet, midsections and necks before electrical shocks were administered.”[74] The Associated Press described the beating of detainees and inhuman conditions more generally in the camp.[75]

As a State Party to the Convention against Torture, Côte d’Ivoire has a responsibility to take all necessary measures to prevent torture within its territory.[76] The Convention makes clear that “[n]o exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture.”[77]

Minister Coulibaly’s response to Human Rights Watch addressed the findings of torture:

In regards to the allegations of torture, be assured that the authors of these crimes, if they are identified, will be brought to justice…. President Ouattara has never wavered in affirming his strong will to fight against impunity, and this has been seen in recent days with the investigation into soldiers in the Republican Forces suspected of having participated in the killings that happened at Nahibly [an internally displaced camp outside Duékoué] in July.[78]

Human Rights Watch appreciates the government’s commitment to ensure justice for victims of torture and welcomes recent progress toward prosecutions for murders committed during the Nahibly camp attack in July.[79] The reality remains, however, that there has been minimal progress in addressing impunity among the Republican Forces, particularly at the command level. No member of the Republican Forces has been arrested for crimes committed during the post-election violence, and soldiers and commanders implicated in serious crimes in response to the August attacks appear to have been similarly protected from accountability. For the Ivorian government to fulfill its promise to fight against impunity, credible investigations and prosecutions for human rights abuses must become the norm—rather than for isolated incidents.

II. Mass Arbitrary Arrests, Illegal Detention, and Extortion

How does the government expect reconciliation when the FRCI steal from us, treat us all with suspicion, [and] do daily mass arrests?

—Pro-Gbagbo youth arbitrarily arrested in Yopougon and detained at the BAE camp, August 2012[80]

Although arbitrary arrests occurred in June 2012 after the Ivorian government said it had thwarted a coup d’état attempt, the August 6 attack on Akouédo precipitated a crackdown unlike any since the end of the post-election crisis. A diplomat from a key partner to Côte d’Ivoire told Human Rights Watch that there were deep concerns about how Ivorian authorities had framed the issue: “The language they use is very concerning: ‘eradication,’ ‘terrorism,’ ‘clean the country up’. They’re so convinced they’re right [about the nature of the threat and the extent of grassroots involvement] … that they’ve decided to put reconciliation aside.”[81]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 31 people picked up in mass arrests between August 7 and September 11 in Yopougon and around Dabou, and their statements indicated that hundreds more had been similarly arrested and detained. In the vast majority of cases, the security forces did not present any specific reason as to why the person was being arrested, much less an arrest warrant. Rather, the security forces—primarily the military—arrived in typically pro-Gbagbo areas and forced young men en masse to board military trucks in which they were shuttled to detention sites.

The overwhelming majority of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch were civilians detained at military bases—particularly the Yopougon BAE base, the Dabou military camp, and the Adjamé base of the military police, discussed in the previous section. In some cases, the arrests, though done without any individual statement of reasons for the arrest, let alone the filing of charges, appeared to be tangentially related to security: once in detention, members of the Republican Forces (FRCI) demanded the location of guns or militia leaders and took detainees’ fingerprints or picture. In other cases, the arrests appeared to be little more than an extortion scheme: many interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were never asked questions, even their name. Whether questioned or not, the way to be released was consistent: meet the FRCI’s demand and pay an often substantial sum of money.

None of those interviewed who were detained after mass arrests ever appeared before a judge, despite the requirement under Ivorian law that an individual appear within 48 hours. Many were in illegal detention at military camps for between three and six days.

The majority of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch suffered physical abuse at the hands of the Republican Forces at the moment of the arrest, while in detention, or both. While in these cases of mass arrest such treatment generally did not reach the level of torture, it often met the definition of cruel and inhuman treatment.

The worst and most recurrent abuses documented by Human Rights Watch linked to mass arrests occurred under the command of Ousmane Coulibaly, known as “Bin Laden,” the officer then in charge of the BAE camp in Yopougon Gesco. There, Yopougon residents and former detainees described near-daily illegal detentions, abusive treatment, and extortion during the month of August. In addition, Coulibaly was in charge of overseeing the response to the August 15 attack in Dabou—a response likewise plagued by mass arbitrary arrests and extortion of detainees to obtain their release. Human Rights Watch continued to document new rounds of arbitrary arrests in Dabou through September 11, two days before the researcher left Côte d’Ivoire.

Article 9 of the ICCPR forbids arbitrary arrests and detentions, requiring that “[a]nyone who is arrested shall be informed, at the time of arrest, of the reasons for his arrest and shall be promptly informed of any charges against him.”[82] Article 7 of the ICCPR, along with the Convention against Torture, protects individuals from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment by state agents like the Republican Forces.[83] Here, the definition of cruel or inhuman treatment is met in a number of cases either by the severity of physical suffering inflicted or by the poor detention conditions, including lack of access to food and water.

Human Rights Watch did document several cases in which the traditional security forces responsible for internal security—the police and gendarmerie—tried to intervene to stop abuses by the military. At times they were successful, while in other cases they were told by soldiers that it was not their affair. Abuses by the Republican Forces appeared to be less acute during searches or patrols when police officers or gendarmes were present.

Yopougon BAE Camp

In the aftermath of the August 5 attacks on a military post and police station in Yopougon, a neighborhood known as a bastion of Gbagbo supporters, members of the Republican Forces responded with mass arbitrary arrests often done apparently on the basis of little more than the person’s ethnicity. Although the August 6 attack on Akouédo occurred on the other side of Abidjan, the allegation of involvement of pro-Gbagbo elements was likewise followed by the mass detention of young men in certain areas of Yopougon, without any individual charges brought.

The frontline of the military’s response in Yopougon was directed by the Republican Forces based at the BAE (for Brigade anti-émeute, or anti-riot unit) police camp. The BAE camp is one of several police camps and stations still controlled by the military.[84] For much of August, the BAE camp served as a revolving door of detainees—with dozens of people arriving after new arrests each day, and dozens of others released upon the payment of an extorted sum of money. Inhuman treatment was pervasive.

A 27-year-old from Yopougon described his arrest on August 24 and subsequent detention at the BAE camp, a testimony similar to several dozen others taken by Human Rights Watch:

I was in a maquis (neighborhood restaurant) with a group of friends. Around 9 p.m., the FRCI arrived in a cargo truck and took all of us from the maquis, even the owner and manager. We were taken to the 37th police precinct, still controlled by the FRCI. There we had to show our ID cards, and they said, “Oh, you’re Bété [a western, typically pro-Gbagbo ethnic group], go here. Oh, you’re Dioula[85] [encompassing several northern, typically pro-Ouattara ethnic groups], go there.” The Dioulas stayed at the 37th [precinct], those of us from [pro-Gbagbo] ethnic groups were taken to the BAE camp in [Yopougon] Gesco…. In the cargo truck, the forced us down and beat us, saying “It’s you the militiamen who we’re looking for.” They stepped on us, kicked us with their boots. They’d even walk on your head, making jokes about squashing militiamen. One guy next to me tried to talk, and one of the FRCI quickly smacked him on the head with the back of his gun. He started bleeding.

When we arrived at the camp, we were put in a cell, about 30 of us. It was really hot in there, and we were packed together, there wasn’t enough room to lie down. They took us out in groups to question us, asking us where guns were hidden. They didn’t question me for long, I guess they believed me. They separated a couple people; I didn’t see them again….

The next morning, the FRCI brought in a guy that works at a phone stand nearby. They told us that we would have to pay 300,000 CFA ($600) to be released. We pleaded and bargained them down to 150,000. I used the guy’s phone to call my cousin. He and my mother came and paid the money, and I was released. I was lucky I only did one day there, but now we have nothing left; my family gave everything for my release.[86]

A Ouattara supporter who lives near the BAE camp told Human Rights Watch, “You wouldn’t believe the things we see there each day. [There are] always youth being trucked in, being beaten. They don’t even hide [the abuses]; it’s often in plain view. [The FRCI there] aren’t afraid of any consequences.”[87] An Ivorian civil society leader agreed: “[The soldiers implicated in abuses] are at ease. They don’t fear anything, and that’s the most dangerous thing: the complete impunity.”[88]

Arbitrary Arrest

Human Rights Watch interviewed Yopougon residents who were arrested in their homes, while eating at a maquis, with friends at a bar, when walking home from church, when in a taxi or a bus, and when attending a funeral. These arrests primarily occurred in perceived pro-Gbagbo areas of Yopougon, including the Koweit, Sicogi, and Niangon neighborhoods. Detainees and other witnesses said often 20 or more people would be arrested at the same time, none of them informed of any specific allegations, much less an arrest warrant, against them.

In almost all of the arrests documented by Human Rights Watch in Yopougon, soldiers from the Republican Forces acted alone or in the lead role in performing the arrests—a role inconsistent with Ivorian and international law. Under Ivorian law, the responsibility for arresting civilians rests primarily with the judicial police, which includes specific categories of the administrative police and the gendarmerie—but not the military.[89] In delegating the responsibility for neighborhood searches and arrests to soldiers not trained to perform such activities—and in particular in delegating to specific former Forces Nouvelles commanders, who often rely on “volunteers” not formally part of the military—Ivorian authorities opened the door to the human rights abuses that followed.

A 28-year-old who was arrested on August 25 told Human Rights Watch that soldiers were clear that there was no individualized basis for the arrest:

I was sitting down in my house when [soldiers] arrived at around 10 or 11 a.m. They announced that they were doing a house-by-house search for guns and a mass roundup. They told me to follow them, and we walked to Carrefour Koweit, where there was a cargo truck waiting with lots of youth already inside. They took 20 to 30 of us to the BAE camp, then went back to the neighborhood to pick up more. They did this all day…. I stayed three days at the BAE, you wouldn’t believe how many people were detained there…. They threatened to send me to the military headquarters if my family didn’t pay for my release…. It was 60,000 CFA ($120) that my family ultimately paid.[90]

A 24-year-old similarly described the FRCI arriving in Yopougon Niangon in a 4x4 covered pickup truck on August 15 and announcing a “systematic mass arrest” as he was walking home around 8:30 p.m. He was told to get into the back of the truck, where there were already eight other youth males, and was taken to the 16th police precinct in Yopougon before being transferred to and detained at the BAE camp for two days. His family ultimately paid 10,000 CFA ($20) for his release.[91]

In most cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the security forces appeared to target youth from typically pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups. As one former BAE detainee said, “You look around [at the detainees] and you see Bété, Guéré, Goro, but no Dioulas.”[92] But at times the mass arrests also swept up people from perceived pro-Ouattara groups. Human Rights Watch interviewed a Malinké who was among a group arbitrarily arrested en masse on August 11. He said that he tried to present his ID card to show that he was from a northern ethnic group, but the soldiers said they were not interested in seeing papers. As he was being forced into a cargo truck, he recalled saying, incredulously, “I voted ADO [Ouattara’s initials], I voted ADO!” But the soldiers said, “We’re taking everyone here in today.” After arriving at the BAE camp, however, the man was able to call a contact in the local RDR youth wing and was quickly released without having to pay anything.[93]

Yopougon residents, particularly in pro-Gbagbo areas, told Human Rights Watch that they lived with a de facto curfew because of the routine arbitrary arrests. Many related that any group of young men from pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups outside after 8 p.m.—whether at a restaurant, a bar, or walking along the street—was likely to be arrested. In a sentiment expressed almost unanimously, a 27-year-old from Yopougon Koweit said: “You have to be in your house after 8 p.m., or you’ll have problems. If you’re outside after then, especially with a group of friends, you’ll be arrested…. Yopougon becomes a ghost town.”[94]

In response to a Human Rights Watch question about the juridical basis for mass arrests, the minister of human rights and public liberties said that after attacking the military, the assailants “would rid themselves of their arms and hide among the population. It was on the basis of a body of evidence and often after denunciation that these people were arrested as part of an investigation. It was targeted arrests and not mass arrests.”[95]

As noted above, particularly in regards to the Adjamé camp, Human Rights Watch did document a few cases in which people were arrested on the basis of “denunciations” or some other form of intelligence. But in the vast majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, arrests were clearly not targeted on the basis of individualized suspicion. Rounding up 20-50 young men seated at a maquis, on board a bus, or in house-to-house arrests in certain neighborhoods is not targeted and is in conflict with Ivorian and human rights law. As detailed below, the arbitrary nature of the arrest was further confirmed by the fact that many of those detained for days at the BAE and Dabou military camps were never questioned. They were merely held, often subjected to inhuman treatment, and then forced to pay a sum of money to gain their release. The government’s answer also does not respond to the fact that the Republican Forces—in contrast to police, gendarmes, and judicial police—do not appear to have any basis under Ivorian law to perform such arrests, whether targeted or mass in nature.

Arbitrary Detention, Inhuman Treatment

The former detainees at the BAE camp interviewed by Human Rights Watch were all civilians and therefore should not have been brought to or detained at a military camp. The length of detention at the BAE camp ranged from one to six days among those who Human Rights Watch interviewed. No one interviewed had charges presented against him, nor did anyone interviewed appear before a judge. As noted above, Ivorian law stipulates that any civilian under arrest is to be charged or released within 48 hours,[96] making anything beyond that time an arbitrary detention under the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Ivorian constitution.[97]

Because Human Rights Watch interviewed people who had been released, the information is likely skewed toward those that spent the least amount of time in detention. Interviewees universally said that many people remained in detention when they were released, since release was dependant on paying a sum of money. And many former detainees described specific individuals being separated out, handcuffed, and moved from the BAE to another facility—likely more permanent detention sites, including the military police base in Adjamé, the Direction de la surveillance du territoire (Department of Territorial Surveillance, commonly known as the DST) in Plateau, and the main Abidjan prison, known as MACA.

Physical abuse against detainees at the BAE camp was common, although did not always occur; several former detainees reported not being physically mistreated after the initial arrest. For those who were beaten, it was generally during questioning or while outside in the courtyard due to overcrowding in detention rooms. One former detainee described being slapped repeatedly as soldiers referred to him as a “militiaman” during an interrogation.[98] Another detainee described soldiers striking him with their belts while being asked about the location of hidden guns. He related, “If they weren’t satisfied with my response, they hit me—in the head, on the back. And they were never satisfied, as I didn’t know anything about guns and kept telling them so.”[99] The detainee showed Human Rights Watch several scars on his back and head that he said were from wounds suffered during detention.

Another detainee, arrested on August 17, described how soldiers tormented him and other detainees as they tried to sleep outside at the camp: