Glossary of Abbreviations

AAAS American Association for the Advancement of Science

ACHPR African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

CAT United Nations Committee Against Torture

DAG Development Assistance Group

DFID United Kingdom Department for International Development

DRS Developing Regional States

EDF Ethiopian Defense Force

EIA Environmental Impact Assessment

EPRDF Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front

EU European Union

GPLM Gambella People’s Liberation Movement

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

ILO International Labour Organization

NGO Nongovernmental Organization

OLF Oromo Liberation Front

PBS Protection of Basic Services

PSNP Productive Safety Net Program

SNNPR Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region

SPLA Sudanese People’s Liberation Army

TPLF Tigray People’s Liberation Front

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

USAID United States Agency for International Development

WFP United Nations World Food Program

ZPEB Zhoungyuan Petroleum Exploration Bureau

Summary

The Ethiopian government is forcibly moving tens of thousands of indigenous people in the western Gambella region from their homes to new villages under its “villagization” program. These population transfers are being carried out with no meaningful consultation and no compensation. Despite government promises to provide basic resources and infrastructure, the new villages have inadequate food, agricultural support, and health and education facilities. Relocations have been marked by threats and assaults, and arbitrary arrest for those who resist the move. The state security forces enforcing the population transfers have been implicated in at least 20 rapes in the past year. Fear and intimidation are widespread among affected populations.

By 2013 the Ethiopian government is planning to resettle 1.5 million people in four regions: Gambella, Afar, Somali, and Benishangul-Gumuz. The process is most advanced in Gambella; relocations started in 2010 and approximately 70,000 people were slated to be moved by the end of 2011. According to the plan of the Gambella regional government, some 45,000 households are to be moved over the three-year life of the plan. Its goals, as stated in the plan, are to provide relocated populations “access to basic socioeconomic infrastructures … and to bring socioeconomic & cultural transformation of the people.” The plan pledges to provide infrastructure to the new villages and assistance to those being relocated to ensure an appropriate transition to secure livelihoods. The plan also states that the movements are voluntary.

Human Rights Watch interviewed over 100 residents affected in the first round of the villagization program in Gambella and found widespread human rights violations at all stages of the program. For example, immediately after the move to a new village, soldiers would force villagers to build their own tukuls (traditional huts) and villagers would be threatened or assaulted for resting or talking during the building process.

Instead of enjoying improved access to government services as promised in the plan, new villagers often go without them altogether. The first round of forced relocations occurred at the worst possible time of year in October and November, just as villagers were preparing to harvest their maize crops. The land in the new villages is also often dry and of poor quality. Despite government pledges, the land near the new villages still needs to be cleared while food and agricultural assistance—seeds, fertilizers, tools, and training—are not provided. As such, some of the relocated populations have faced hunger and even starvation. Residents may walk back to their old villages where there is still access to water and food, though returning to their old fields they have found crops destroyed by baboons and rats.

Human Rights Watch’s research shows that the program is not meeting the government’s aims of improving infrastructure for Gambella’s residents. On the contrary, it threatens their access, and right, to basic services. Due to this lack of service provision in the new villages, children have not been able to attend school, women are walking farther to access water thereby facing harassment or beatings from soldiers, and few residents are receiving basic healthcare services.

The impact of these forcible transfers has been far greater than the normal challenges associated with adjusting to a new location. Shifting cultivators—farmers who move from one location to another over the years—are being required to plant crops in a single location. Pastoralists are being forced to abandon their cattle-based livelihoods in favor of settled cultivation. In the absence of meaningful infrastructural support, the changes for both populations may have life-threatening consequences. Livelihoods and food security in Gambella are precarious, and the policy is disrupting a delicate balance of survival for many.

The villagization program is taking place in areas where significant land investment is planned and/or occurring. The Ethiopian federal government has consistently denied that the villagization process in Gambella is connected to the leasing of large areas of land for commercial agriculture, but villagers have been told by local government officials that this is an underlying reason for their displacement. Former local government officials told Human Rights Watch the same thing.

Since 2008 Ethiopia has leased out at least 3.6 million hectares of land nationally (as of January 2011) to foreign and domestic investors, an area the size of the Netherlands. An additional 2.1 million hectares of land is available through the federal government’s land bank for agricultural investment (as of January 2011). In Gambella, 42 percent of the total land area of the region is either being marketed for lease to investors or has already been awarded to investors, and many of the areas where people have been forcibly removed under the villagization program are located within these parcels.

Areas essential to livelihoods such as grazing areas, forests, and fields for shifting cultivation have been taken from the local populations with no meaningful consultation or compensation. The indigenous peoples of these areas, ethnic Anuak and Nuer among others, have never had formal title to the land they have lived on and used. The government simply claims that these areas are “uninhabited” or “underutilized” and thus skirts the Ethiopian constitutional provisions and laws that would protect these populations from being relocated.

Such population transfers are not new. Ethiopia has a long and brutal history of failed attempts at resettling millions of people in collectivized villages, particularly under the Derg regime, in power until 1991, but also under the current government of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). The villagization concept has now been reborn in Gambella under the guise of “socioeconomic and cultural transformation.”

Foreign donors to Ethiopia assert that they have no direct involvement in the villagization programs, although several donors concede that they may indirectly support the program through general budget support to local governments and by underwriting basic services in the new villages. As a result of their potential responsibilities and liabilities, donors have undertaken assessments into the villagization program in Gambella and in Benishangul-Gumuz and determined that the relocations were voluntary.

Human Rights Watch’s research on the ground in Gambella contradicts this finding. We believe that donors to the Protection of Basic Services (PBS) Program that underwrites the creation of infrastructure in the new villages, such as the World Bank, European Union (EU), and United Kingdom, are involved in a program that is doing more to undermine the rights and livelihoods of the population than to improve them.

Human Rights Watch calls on the government of Ethiopia to halt ongoing human rights violations being committed in the name of villagization. Relocations should be voluntary and populations should be properly consulted and compensated. Mass displacement to make way for commercial agriculture in the absence of a proper legal process contravenes Ethiopia’s constitution and violates the rights of indigenous peoples under international law.

International donors should ensure that they are not providing support for forced displacement or facilitating rights violations in the name of development. They should press Ethiopia to live up to its responsibilities under Ethiopian and international law, namely to provide communities with genuine consultation on the villagization process, ensure that the relocation of indigenous people is voluntary, compensate them appropriately, prevent human rights violations during and after any relocation, and prosecute those implicated in abuses. Donors should also seek to ensure that the government meets its obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill the economic and social rights of the people in new villages.

Recommendations

To the Government of Ethiopia

- Uphold the rights under the Ethiopian constitution and

international human rights law of Gambella’s indigenous populations prior

to any further villagization including, at a minimum:

- Implementing a land tenure registration system that increases land tenure security (including for shifting cultivators and for communal or grazing areas);

- Protections from expropriation;

- Implementation of compensation procedures.

- Engage Gambella’s indigenous groups on alternative livelihood provisions prior to the implementation of any further villagization, resettlement, or significant land investment activities. This process should respect indigenous values and rights while allowing development activities to be undertaken for the benefit of Ethiopia.

- Permit residents relocated by villagization to return to their old farms in the interim and take other necessary steps to ensure that affected populations have adequate access to water, food, and other necessities.

- Ensure that forcibly relocated indigenous communities have adequate redress, preferably by restitution or if not possible, just, fair, and equitable compensation for the lands, territories, and resources that they have traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used.

- Ensure that future villagization efforts meet international

standards prohibiting forced eviction and protecting indigenous peoples, in

particular:

- Involve communities in all aspects of program planning;

- Are genuinely voluntary and allow the right of return to old farms and residences at any time without intimidation, violence, or other rights violations;

- Occur only after required and promised infrastructure is in place and operational in new villages. This also includes the clearing of land, appropriate training, agricultural input provision, and appropriate interim food aid to ensure transitions to secure livelihoods;

- Recognize the unique needs of agro-pastoral populations such as the Nuer, including provision of dry season water sources, ongoing access to grazing lands, among others;

- Involve communities in site selection: sites should be fertile, adjacent to adequate year round water supplies, and old vacated areas should not be transferred to investors for a period of time in order to allow for the voluntary right of return;

- Occur only after land tenure provisions have been fully implemented in the villagized area;

- Are timed so as not to disrupt critical agricultural production times, namely harvesting and planting periods.

- Take all necessary measures, including issuing clear guidelines to regional and woreda (district) government officials, to ensure that the military and police abide by international human rights standards; minimize the role of the military in the villagization process.

- Discipline or prosecute as appropriate all government and military officials, regardless of position, implicated in human rights violations associated with villagization.

- Repeal or amend all laws that infringe upon the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly, including the Charities and Societies Proclamation, the Mass Media and Freedom of Information Proclamation, and the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation, to bring them into line with international standards.

- Allow independent human rights organizations and the media unimpeded access throughout the Gambella region.

- Treat all individuals taken into custody in accordance with international due process standards.

To Ethiopia’s Foreign Donors in the Development Assistance Group (DAG)

- Ensure that no form of support, whether financial (direct or general budget support), diplomatic, or technical, is used to assist in the villagization process in Gambella until the government investigates human rights abuses linked to the process, abides by donors’ Good Practice Guidelines and Principles on Resettlement and takes appropriate measures to prevent future abuses.

- Support the prompt implementation of land tenure security provisions for the area’s indigenous populations; press the Ethiopian government to ensure this happens prior to further villagization efforts.

- Press the government of Ethiopia to engage with Gambella’s indigenous populations about alternative livelihood provisions prior to the implementation of any further villagization, resettlement, or significant land investment activities.

- Publicly call on the Ethiopian government to amend or repeal the Charities and Societies Proclamation, the Mass Media and Freedom of Information Proclamation, and the Anti-Terrorism Proclamationto bring them into line with international standards.

- Increase independent on-the-ground humanitarian monitoring in Gambella to identify humanitarian needs in anticipation of emergencies.

To Agricultural Investors

- Conduct due diligence to ensure that no people were forcibly displaced to make way for any concession, and ensure that the government is abiding by donors’ Good Practice Guidelines and Principles on Resettlement in respect of any people moved in relation to a concession.

- Potential investors should not enter into leases with the

Ethiopian government until:

- A land tenure registration system has been implemented for customary users of the proposed lease area;

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) have been carried out that identify potential impacts and strategies to mitigate these impacts. These EIAs should be available publically and to impacted communities;

- The investor has consulted with local indigenous communities. These communities must give their free and informed prior consent prior to the lease and compensation should be provided by the government, as per Ethiopian law, to any customary users of the land, including shifting cultivators and agro-pastoral populations.

Methodology

This report is based on over 100 interviews undertaken over a four-week period in Ethiopia from May to June 2011, and one week interviewing refugees at the Ifo refugee camp in Dadaab and Nairobi, Kenya, where many Gambellans are presently located. Another 10 donors and federal government officials were interviewed in Addis Ababa during August 2011. Interviewees from across the Gambella region included community leaders, farmers with direct experience of the villagization process in their communities, students, nongovernmental organization (NGO) workers, and former government officials.

Human Rights Watch visited 5 of the 12 woredas where the villagization process is presently being implemented, and obtained testimony from 16 of the villages affected during the first year of the program. The woredas visited were within the Anuak and Nuer zones. No Majangere areas were visited due to difficulty of access.

In addition, Human Rights Watch conducted 10 telephone interviews with members of the United States and Europe-based diaspora community, academics, and members of NGOs involved in Gambella. Human Rights Watch wrote to the government of Ethiopia and to the Development Assistance Group on November 16, 2011, summarizing our findings and requesting an official response. We received a response from the government of Ethiopia on December 19, 2011, and a response from the DAG on December 12, 2011. Both responses are included as appendices to this report.

Human Rights Watch identified interviewees through various contacts (including government officials, journalists, and Ethiopian diaspora). Efforts were made to interview a wide range of people across gender, age, ethnicity, urban and rural, and geographic lines. Interviews with villagers were conducted in safe and secluded locations, often in interviewees’ villages, and were conducted in English, Amharic, Anuak, or Nuer, using local interpreters where necessary. Villages were chosen based largely on road access, researcher knowledge of those villages, and security considerations. In Kenya efforts were made to interview former residents who left Gambella from areas where villagization was being carried out and when the program was being implemented.

Human rights research and monitoring is very challenging in Ethiopia for both foreign researchers and Ethiopian individuals and organizations. This is the result of various factors: laws that severely infringe on the functioning of NGOs including the Charities and Societies Proclamation and the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation; restrictions on media freedoms; the government’s intolerance of political dissent; and the intimidation and fear generated by government officials that permeates life in Ethiopia. Given this environment, it was very difficult to locate, identify, and interview individuals in a manner that respected the safety and security of interviewer and interviewee. The vast majority of interviewees in Gambella expressed concern over possible retribution from the government. Human Rights Watch has omitted names and identifying characteristics of individuals and certain locales to minimize the likelihood of government action against them and their communities.

Background to Villagization in Ethiopia

Ethiopia has a long history of brutally displacing rural populations through resettlement and so-called villagization programs during the former Derg regime and under the current government of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front.[1] Often publicized as intended to provide remote populations with better services and socio-economic infrastructure, or to improve food and water distribution, in most cases the programs failed the populations that they were supposed to help.[2]

Displacement in the past has occurred primarily in two ways: resettlement from the highlands to the lowlands, and through villagization, defined as the clustering of agro-pastoral and/or shifting cultivator populations into more permanent, sedentary settlements. Past villagization programs were rife with problems: forced displacements of populations accompanied by serious human rights violations in which dissenting opinions were silenced by fear of retribution. A leading scholar on villagization wrote in 1991 about the Derg-era programs:

The verdict on villagization was not favorable. Thousands of people fled to avoid villagization; others died or lived in deplorable conditions after being forcibly resettled.… There were indications that in the short term, villagization may have further impoverished an already poor peasantry. The services that were supposed to be delivered in new villages, such as water, electricity, health care clinics, schools, transportation, and agricultural extension services, were not being provided because the Government lacked the necessary resources.… Denied immediate access to their fields, the peasants were also prevented from guarding their crops from birds and other wild animals.[3]

The History of Villagization

Villagization has the objective of grouping scattered farming communities into small villages of several hundred households each. Villagization in Ethiopia has a lengthy history, with dramatic impacts on rural populations, and was a key component of the Derg’s socialist agricultural collectivization policies. The Derg’s villagization program was ambitious: more than 30 million rural peasants—two-thirds of the total population—were planned to be moved into villages over a nine-year period. [4] By 1989 the government had villagized 13 million people, when international condemnation, deteriorating security conditions, and lack of resources caused the program to dramatically slow down. [5] Unlike the current program, villagization was not widespread for pastoralist and shifting cultivator communities.

The official rationale for villagization was to promote rational land use; conserve resources; strengthen security; and provide access to clean water, health and education infrastructure.[6] However, these new villages were often the source of forced labor for government projects—whether for road construction, agricultural production, or other infrastructure development. For the most part villagization was implemented with the threat of force, rather than outright force, with some exceptions. For example, in Harerghe (in eastern Ethiopia) and Illubabor (modern day Gambella), government security forces implementing the process committed theft, arbitrary detention, extrajudicial executions, torture, rape, and burning of property.[7]

Many villagers fled the newly created villages. One estimate suggests that 50,000 people from the Oromo ethnic group fled their villages in Harerghe in 1986 and became refugees in Somalia.[8] Between 1984 and 1986 as many as 33,000 settlers across the country (5.5 percent of the total number of people moved) may have died from starvation and tropical diseases, while at least 84,000, or 14 percent more, are believed to have fled these new settlements.[9]

Past Villagization and Rights Violations in Gambella

Many of the residents of Gambella[10] who spoke to Human Rights Watch view the current villagization program as merely the latest in a long line of the government’s discriminatory campaigns.[11] Gambella’s first large-scale displacements for commercial agriculture began in 1979. Many of Gambella’s indigenous Anuak were evicted en masse when the government set up irrigation schemes on the Baro River, the main navigable waterway in the region, with Amhara settlers brought from the highlands to farm the schemes.[12] In 1984, 150,000 settlers from the food insecure highland areas of Tigray, Amhara, and Oromia arrived in Gambella,[13] a significant number for a region that today has a population of just over twice that, approximately 307,000.[14]

Some Anuak who lived along the riverbanks refused to be relocated. Government tractors cleared their crops and lands to “encourage” the river dwellers to move to the resettlement schemes. Conflict increased between settlers and indigenous populations over the loss of land and forested areas, while an increased military presence restricted indigenous people’s movement around their traditional lands.[15]

Villagization of the rural Anuak began in 1986 with the new villages being described as “more akin to forced labor camps.”[16] Villagized and resettled Anuak, along with many highlander settlers, were forced to work on the new state farms, clearing forests, or building infrastructure. Government security forces beat, detained, and intimidated those who resisted, and many fled into southern Sudan. The Anuak were prevented from moving freely outside of the villages, and one source suggests that Anuak were denied access to the Baro River for fishing activities—a crucial part of Anuak livelihoods and identity. The authorities often beat those who were caught.[17]

Opposition to the Derg’s resettlement and villagization policies resulted in the formation of the Gambella People’s Liberation Movement (GPLM),[18] allied with the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF).[19] The Derg and the GPLM committed human rights abuses as the Ethiopian government targeted the GPLM and rural populations accused of supporting the GPLM, while the GPLM attacked individuals perceived to be linked to the government.[20]

Tensions remained high culminating on December 13, 2003, when, in response to an attack on a government vehicle that killed seven Ethiopian highlanders and one Anuak, the Ethiopian military and highlander militia groups massacred hundreds of people over several days in Gambella town, Abobo town, and surrounding areas.[21] Throughout 2004 the military then carried out a campaign of violence against Anuak communities amounting to crimes against humanity.[22]

Sporadic, isolated, and disorganized attempts at forced displacement have occurred since that time, with one effort in November 2008 involving the forced displacement of Gambellans from Laare and Puldeng villages to a new area. The villagers resisted and the police responded, reportedly killing livestock, burning homes, and killing nine people and wounding 23.[23]

Background to the Current Villagization Program

Livelihoods and food security in Gambella are precarious. Policy changes are going to affect the survival of hundreds of thousands of people. According to the government, renewed villagization in Gambella is intended to improve socio-economic infrastructure. The local populations, however, fear that it is a tool to expropriate their land for commercial agriculture and natural resource extraction.

Livelihoods in Gambella

In comparison with the drier, relatively cool, and heavily populated highlands, the Gambella region is oppressively hot, richly endowed with high quality soils, abundant water supplies (part of the White Nile watershed), widespread forest cover, low relative population densities, and other natural resources.[24] According to the most recent census of 2007, the population of Gambella is about 307,000. Of those, 229,000 people— some 46,000 households comprising various ethnic backgrounds—live in rural areas. Approximately 46 percent of the total population is Nuer, 21 percent Anuak, 20 percent Highlander Ethiopian, 7 percent Majangere, 3 percent Opo, and 3 percent Komo.[25] In addition, there are approximately 19,000 (mainly Anuak) refugees from the Sudan civil war (in Pugnido),[26] along with thousands of Lou Nuer who arrived in 2009 following conflict with the Murle in South Sudan. Nuer and Anuak are by far the largest ethnic groups in terms of population and relative political power.

The livelihoods of the Anuak and Nuer are dramatically different from each other. As a result, displacements of any kind have radically different impacts on each ethnic group.

Anuak tradition suggests the Anuak moved into the Gambella region approximately 400 years ago. [27] Their language, from the Nilo-Saharan language group, is unique to the Gambella region, and is not understood by neighboring ethnicities. Their culture is also unique to the region, as is their reliance on shifting cultivation as a livelihood strategy. Their identity is intimately tied to the land and the rivers along which they live, and until recently, have had a traditional land base in Gambella that is used solely by their ethnic group. Tension between Nuer and Anuak over access to land has been an issue in Gambella.

The Anuak largely fall into two livelihood groups: the Openo clan who live along the region’s main rivers and are thus more sedentary, and the upland or forest dwellers called the Lul clan. As a result, the Anuak are spread out geographically throughout the forest and along the major riverbanks, with more dense agglomerations in the towns.

The upland Anuak practice a pattern of shifting cultivation, whereby one parcel of land is worked for several years before moving on to another area. Two or three cycles of cultivation are carried out before returning to the first plot in seven to ten years. The Anuak typically live in small settlements of several families each, and utilize low levels of agricultural technology, resulting in low productivity. Maize and sorghum are the most common crops, and their livelihoods are enhanced through access to fish and forest products, such as roots, leaves, nuts, and fruits. Their agricultural knowledge and livelihood strategies are based on this continual shifting—a striking contrast to the more sedentary living envisioned under the villagization program. The riverside Anuak lead a more sedentary existence and their livelihood and identity is tied intricately to the rivers. In addition to agriculture that keeps them in one place, their livelihood also depends on fish and fruit trees.

The Nuer have a more recent history in the region. It has been suggested that the Nuer, along with other Nilotic groups, settled along the rivers of eastern South Sudan around the 14th century.[28] The Nuer first moved into the Gambella region during the late 19th century.[29] The seasonal movement throughout “Nuerland” is based largely on finding appropriate grazing lands for the Nuer’s cattle—a practice directly threatened by the villagization process. The population also increased dramatically due to influxes related to the war in Sudan during the 1980s. As agro-pastoralists, the majority of Nuer have little experience living in sedentary settlements. These cattle are uniquely tied to their livelihood strategy, ethnic identity, and cultural patterns. They are a source of food, wealth, and prestige for the Nuer. Nuer language is unique within the Gambella region, and cannot be understood by any of the region’s other ethnicities. The Nuer are also well-known for their unique cultural practices, including their ritual scarification.[30]

Agricultural Land Investment in Gambella

One of the more dramatic recent trends in Ethiopia, and Gambella in particular, is the leasing out of large land areas to agricultural investors. Since 2008 Ethiopia has leased out at least 3.6 million hectares of land nationally as of January 2011—an area the size of the Netherlands. An additional 2.1 million hectares of land is available through the federal government’s land bank for agricultural investment. In Gambella 42 percent of the total land area is either being marketed for lease to investors or has already been awarded to investors.[31] This land is being awarded to large-scale foreign investors[32] and small-scale Ethiopian or diaspora investors with no meaningful consultation and no compensation to farmers for lost farmland.[33]

The environmental and social impacts of land investment in Gambella are significant, and are contributing to rapidly decreasing levels of food security for the poor and marginalized, particularly the indigenous population. There are no limits on water use, little in the way of accountability, and nothing in place to protect the rights and livelihoods of local communities in the vicinity of these investments.[34] While direct displacement from populated areas has thus far been minimized, farmland has been taken and many areas that contribute to livelihood provision have been taken by investors with no advance notice such as areas of shifting cultivation, and forest.

As has historically been the case, the government considers these areas to be “unused” or “underutilized,” and therefore available for transfer to industrial agriculture.[35] Metasebia Tadesse, minister counselor at the Ethiopian embassy in New Delhi, sums up this perspective: “Most Ethiopians live on highlands; what we are giving on lease is low, barren land. Foreign farmers have to dig meters into the ground to get water. Local farmers don’t have the technology to do that. This is completely uninhabited land. There is no evacuation or dislocation of people.”[36]

Gambella’s Villagization Process

The Government Villagization Plan

The Ethiopian federal government’s current villagization program is occurring in four regions—Gambella, Benishangul-Gumuz, Somali, and Afar. According to published reports, this involves the resettlement of approximately 1.5 million people throughout the lowland areas of the country—500,000 in Somali region, 500,000 in Afar region, 225,000 in Benishangul-Gumuz, and 225,000 in Gambella.[37] The movements in Afar and Somali are all one-year programs, while Gambella and Benishangul-Gumuz are three-year programs that started in the latter half of 2010. As of November 2010, 150,000 Somalis had been moved, with the remainder to be moved throughout the rest of the year.[38] Recent reports from Ethiopian state media indicate that involuntary displacements in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) associated with irrigated sugar plantations are now being classified as part of a villagization program, with 10,995 pastoralist household villagized in 2010/2011 and over 20,000 more to be villagized imminently.[39]

According to Minister of Federal Affairs Shiferaw Teklemariam, the programs in Somali and Afar are “primarily to resettle people in less arid areas near the Wabe Shebelle and Awash rivers,” while the Gambella and Benishangul-Gumuz movements are for “improved service provision.” [40] In a December 2011 letter to Human Rights Watch the minister said that “the villagization programs in Gambella … are efforts to tackle poverty and ignorance” and that in addition “the targets are to provide efficient and effective economic and social services (safe drinking water, optimum Health care, Education, improved agronomy practices, market access etc.), create an access to infrastructure (road, power, telecommunication etc.) and ensure the citizens’ full engagement in good governance and democratic exercise.” [41]

According to the Gambella Regional Government’s “Villagization Program Plan 2003 EFY” for 2010, the goal of Gambella’s program is to “provide basic socioeconomic infrastructures” and “ultimately to enable them food secured [their food security] and to bring socioeconomic & cultural transformation of the people.”[42] The original concept was to resettle 45,000 households across Gambella region over the three years of the life of the project, with approximately 15,000 households the first year. However, according to media reports and a subsequent implementation plan,[43] 26,000 households will be moved in the first year because, according to Gambella Governor Omod Obang, “the resettlers are showing keen interest for the program.”[44] In his letter to Human Rights Watch, Shiferaw Teklemariam stated that 20,243 households were moved the first year (2010/2011).[45]

While implementation responsibilities lie with the regional and lower levels of government, it is widely understood that the federal government is the originator of the policy throughout the four regions. Former regional and woreda civil servants in Gambella informed Human Rights Watch that a “coordinator” from the federal government has been posted with the regional government and there are two federal representatives in each of the woredas to oversee the villagization process.[46]

Many communities were told by the authorities they would be required to move for “improved infrastructure provision,” while others were told they were to be moved either to mitigate the problems associated with the annual flooding of the Baro River or for security reasons (mostly for Nuer communities that fear cattle-raiding).[47]

Villagization is to occur in all woredas in Gambella, and is intended, according to government plans, to move people from smaller, more scattered settlements—whether practicing riverside agriculture, shifting cultivation, or agro-pastoralism—into larger settlements of 500 to 600 households each. People are to be moved within their woreda only—there is no intention of resettlement from one woreda to another.[48]

Some of the 49 villages that people were being moved to in the first year of the plan already exist and have some infrastructure, while in other cases the new village is being developed from the ground up. According to the plan, newly developed infrastructure includes 19 primary schools, 25 health clinics, 51 water schemes, 41 grinding mills, 18 veterinary clinics, 195 kilometers of rural roads, and 49 warehouses/storage facilities. At the end of the program, the intention is that all Anuak, Nuer, and other indigenous peoples (not including South Sudanese refugees) will be gathered in towns of 500 to 600 households each farming on three to four hectares of land.[49] There is no mention in the plan of what will happen to the Nuer cattle under the villagization program. The widespread fears are that shifting cultivation, riverside cultivation, and agro-pastoralism will disappear.

The budget for the first year of the plan was 61.9 million Birr (approximately US$3.7 million), [50] which does not include the 58.2 million Birr (US$3.4 million) of food aid required. [51] According to the plan, the “implementer” of the food aid requirements is supposed to be Non Governmental Organizations. [52] The rest of the budget items are to be implemented by various levels of government. The plan is silent on human rights protections.

Affected Communities

Over the three years of this program all households of the indigenous inhabitants of rural Gambella are to be moved. In the first year, 2010/2011, villagization has occurred in woredas in Gambella region: Gambella, Godere, Gog, Abobo, Dimma, and to some extent in Itang and Jor. These woredas are for the most part Anuak, and these are the areas that are closest to the major infrastructure of the region, such as the main roads and the largest towns. These are also the areas of most intensive agricultural land investment.

Eight villages out of the total of sixteen that Human Rights Watch obtained testimony from already existed prior to the villagization process—villagers were being moved from scattered settlements to an existing village. The other eight villages were mostly located in dry, arid areas away from any dry season water sources such as a major river. Usually the areas were known to the Anuak as they often had used that land in the past as part of a shifting cultivation land use pattern, but had abandoned it due to decreased soil fertility.[53]

Indigenous communities were moved within their own woreda, and movements thus far have respected ethnic or clan lines. Anuak fall into two main livelihood groups: those living along the rivers (more sedentary) and those in the upland forest (who usually practice shifting cultivation). All the new villages are located in the upland forest, and so Anuak relocated from the riverbank are facing an additional adjustment and interruption to their livelihoods by being relocated from the water sources on which they depend for water and to grow food.

Human Rights Watch visits to the Anuak and Nuer areas showed a very different government approach to villagization between each of those ethnic groups.

While the villagization process in the Anuak areas has severely affected the livelihoods of those affected, the loss of livelihoods in the Nuer areas is even more dramatic. The Nuer are agro-pastoralists and the needs of their cattle are of critical importance. The Nuer were told they would be villagized for security purposes—to reduce the likelihood of cattle raids from neighboring tribes, such as the Murle from South Sudan. [54] The Nuer interviewed by Human Rights Watch stated that the new locations and larger community size made the villages easier to defend. However, given the complete lack of a dry season water source, Nuer could not keep their cattle anywhere near the village. As a result, two new Nuer villages that had been created by the villagization process had already been completely abandoned. [55]

A newly constructed but virtually abandoned Nuer village. In this village, villagers were often forced to build tukuls (traditional huts) that they will likely never live in. Additionally, the village lacked dry season water access and was vulnerable to Murle cattle raids.

Villagization is also happening to Anuak town residents who are not civil servants in certain areas of Gambella town, Pugnido town (Gog woreda), Dimma town (Dimma woreda), and Abobo town (Abobo woreda). Residents said that they were told that if they did not have a job with the government in these urban areas, then they must go to the villages.[56]

Human Rights Abuses in the Villagization Process

We want you to be clear that the government brought us here... to die... right here.... We want the world to hear that government brought the Anuak people here to die. They brought us no food, they gave away our land to the foreigners so we can’t even move back. On all sides the land is given away, so we will die here in one place.

—An Anuak elder in Abobo woreda, May 2011.

The government’s plan asserts that the villagization process is voluntary, as does the letter from the minister of federal affairs which states that “[villagization] was fully conducted on voluntary basis and with the full consent and participation of the beneficiaries.”[57] But Human Rights Watch’s research found the process to be far from voluntary and has been accompanied by widespread human rights violations, including forced displacement, arbitrary arrest and detention, beatings, rape, and other sexual violence. Residents have been denied their rights to food, education, and adequate housing. These problems were similar for all areas in Gambella that Human Rights Watch visited.

The villagization process began in mid to late 2010, depending on the area. The first meetings between government officials and the community would be held several months before the move was to occur. In most cases these meetings were held in mid-2010. Government officials were usually from the woreda level, although for larger communities or those close to major towns regional or federal officials would be present. Usually there would be some regional police present, but participants said that security forces were usually at a minimum for the first meeting.

It was at these initial meetings that communities were first notified that they would be moved in the coming months. If communities were not cooperative, or indicated their refusal to move, the next meeting, usually several weeks later, involved visits from the Ethiopian army, regional police, local militias, and government officials.[58]

Residents described to Human Rights Watch that any refusal or inquiries was met with beatings, arrests, or intimidation from the army. A woman from Abobo woreda said:

The first meeting was just with the kebele government officials, but we refused their [villagization] plan. They then arrested the village chief at night; the soldiers took him to the police station and he was there for one month. Then the next time the district officials, police, army, and militias showed up. They called a meeting, and nobody said anything because of the soldiers’ presence.[59]

In some cases the authorities told the villagers ahead of time when they should move. But for the most part, when it was time to go, government officials, accompanied by police and military, arrived and told them they should move.

Soldiers accompanied the villagers to the new sites and supervised the multi-week tukul (traditional hut) construction period. The distance from the old to the new villages typically involved a walk of two to five hours, though in Dimma woreda some people were relocated up to 12 hours away by foot. Once the villagers built the tukuls, the army typically left.

The moves began in October or November 2010, just prior to harvest time. Stated government promises were similar for all villages: the authorities would provide schools, health clinics, access to water, grinding mills, cleared land for crops, and food aid for seven to eight months. However, despite the promises of schools and clinics, the regional government’s plan shows that these were not planned for the majority of villages. In short, the authorities did not tell the villagers the truth.[60] Some communities were also promised tools, agricultural inputs, clothes, and mosquito nets.

Human Rights Watch found that the actual assistance to the villagers invariably fell far short of the promises. Of the villages visited by Human Rights Watch, a grinding mill building had been completed in two, and a school and clinic had been built in one, but none of these was operational.[61] The authorities provided a very limited amount of food aid to only five of these villages, and just two villages had any land cleared by the government for agricultural production. When it became apparent that little or none of the promised infrastructure or food was to be provided, some villagers simply abandoned the new villages. Some returned to their old farms, while many of the able-bodied men fled into the bush, to South Sudan, or to the UNHCR refugee camps in Kenya, leaving women, children, the sick, and the elderly behind.[62]

The claims by Human Rights Watch that Gambellans are leaving Gambella to the refugee camps of Kenya were refuted by Minister of Federal Affairs Shiferaw Teklemariam who claims that this assertion is “further evidence of baseless allegation and total fabrication” and that “if this was even remotely true, there must certainly have been an official report from UNHCR....There is no such report, simply because there are no such refugees.” According to UNHCR, Kenya’s refugee camps have 1,474 refugees and asylum seekers of Gambellan origin as of May 2011[63] and 2,155 Gambellans as of December 2011,[64] an increase of 681 in the last seven months. Fifty recent arrivals were interviewed by Human Rights Watch at the UNHCR refugee camp in Dadaab in June 2011. Community leaders within Dadaab’s Anuak community report that 613 Anuak have arrived at UNHCR’s Ifo refugee camp in Dadaab during the last four months of 2011 (October to December 2011).[65] The photo below taken in June 2011 shows an Anuak refugee cultural celebration at the UNHCR camp in Kenya.

Anuak community members conducting an Anuak cultural celebration dance, at the UNHCR refugee camp in Dadaab, Kenya on June 19, 2011. Ethiopia's Minister of Federal Affairs claims there is no evidence of refugees in Kenya an South Sudan fleeing the villagization program, but according to Anuak community leaders, 623 Anuak arrived in Dadaab between October 2011 and December 2011 alone.

Forced Displacement

We were told, “If somebody refuses, the government will take action”—so the people went to the new village—by force.

—Villager in Abobo woreda, May 2011.

Gambella’s first year of the three-year villagization program has mirrored the forced displacements of Ethiopia’s past villagization efforts.[66]

Virtually all of the villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their move was an involuntary, forced process. While all villages reported being engaged in some form of “consultation,” it took the form of government officials “informing” people that they would be moved to a new location. Villagers said that in many of these meetings, they did not utter a word for fear of reprisal by the authorities. And their fears were justified: those who expressed concern or question the government’s motives were frequently threatened, beaten, and arrested by police or soldiers. A villager told Human Rights Watch:

The government came and talked to the village elders and those that are influential. Then the government together with the soldiers and elders called us for a meeting where we were told we were to be moved. There was no consultation or opportunity for dialogue, they were just informing us. Those that spoke up are considered “inciters,” and five of them were arrested from the two villages. They were in prison for between 20 days and one month, and were released on the condition they do not speak against villagization. So either they are silent or they flee.

Despite the intimidation, arrests, and beatings, some communities refused to move to the new villages. The government tried different techniques to persuade them, including dialogue, intimidation, and violence, but several of these communities continued to refuse and have been allowed, thus far, to stay put, but for some of them at a very high cost. A person from Dimma woreda said: “People left their crops behind then tried to return. Those who refused to go had their houses burned down by soldiers. Crops were destroyed. In [the village], where there were many mangoes and some sugar cane, government soldiers burned 100 houses.”[67]

In Abobo and Gog woredas people who left the new villages tried to return to their old farming areas. Some communities have been allowed to go back to their old farms, given the absence of food available at the new villages. In the majority of these cases women, children, and the sick have remained in the new villages. The minister of federal affairs stated that “They have also all the right to return to their original locations whenever and if they want.”[68] It is evident that this has not occurred in all cases. A former Okula resident said: “If you go back [to the farm] to get materials or for washing, you get harassed and beaten. They [the army] say we are shiftas [bandits]. They say that ‘You black men are our slaves.’”[69] A former Dimma woreda resident said: “The [army] told us ‘If you go back, we will destroy the old hand pump.’ There is no hand pump in our new village.”[70]

Forced Displacement from Urban Centers

Without providing a credible reason, the government is also moving Anuak from urban areas into new rural villages. In at least four urban areas (Gambella town, Dimma town, Pugnido, and Abobo town), Anuak—and only Anuak—who were not civil servants or among the few Anuak business owners, were told by the authorities that they needed to leave town and settle in nearby villages. This process began in November 2010.

An Anuak from Dimma town recounted:

People from Dimma town were moved too. “We have a project here and you must go. Civil servants and businesses can stay—all other Anuak must go,” government told us. There are more and more Highlanders in Dimma town now. As Anuak move out of Dimma, Highlanders move in immediately—from Tigray, Amhara, Wollo. There is very good business in Dimma for gold. Even students had to leave Dimma—“There is a school where you are going” [there was not]. All Anuak have left Dimma, if you do not go, you get arrested. [71]

None of the reasons stated by the government, or the rationale expressed in the plan, readily explain urban displacement. The Gambella Regional Government’s Villagization Plan makes no mention of moving indigenous people such as the Anuak from urban areas to the new villages.

In Gambella town two main types of displacement are occurring: people who live along the Baro River on prime agricultural land on the periphery of town and those who live in the more dense areas of Gambella, where tukuls are more common. Many of the most egregious abuses were reported from those displaced from Gambella town. According to an attendee at a public meeting in December 2010, the Gambella regional governor told people: “Lands you are using are not utilized. We have investors coming who will use more efficiently. Those who resist we will take all possible action.” [72] Several other interviewees who attended the same public meeting provided similar accounts of the governor’s statement. [73]

Displaced Anuak from Gambella town were told to go to the village of Wan Carmie. By May 2011 virtually no one remained in Wan Carmie, fleeing elsewhere. At the time, many Anuak were still present in Gambella town. Human Rights Watch is concerned that an underlying reason for the urban-based displacement is government support for private investment. Instead, individuals were being told that the reason for the forced relocation was the poor standard of their houses. A former resident explained:

We were told this place should have this type of buildings, and so on and [the authorities would say] “You have not done that so we will relocate you to Carmie. You should have certain building standards, so we will allocate this land to the Highlanders who will build to the standards contained in the Master Plan. You are not in the right area for that type of construction.” [74]

A woman moved to Carmie was told by government officials when they visited her farm: “We have some projects to implement here. [Saudi investor name withheld] needs to use this area for a market so you must go.”[75] Similar testimonies were received from three different villagers who were displaced from along the Baro River.[76]

A former resident of Pugnido town said he was told by woreda officials: “You have no land here. You take your tools and go build a house in the village. We don’t want people here doing nothing. We will make this area for business and farming.”[77]

A former Dimma resident told us: “They held a town meeting in Dimma where we were told ‘if you have no job, all Anuaks should go away.’ A few days later, soldiers and district officers were in town to tell people it was time to go … some people resisted, so soldiers were ‘active.’”[78] In three of the four woredas where urban Anuak are being relocated (Gambella, Abobo, and Gog woredas) significant agricultural land investment is happening. In the fourth woreda (Dimma) there is increasing investment in the gold mining industry.[79]

Suppressing Dissent

The Ethiopian government’s longtime tactic of stifling opposition to programs and policies through fear and intimidation is evident in the implementation of the villagization program. Citizens cannot voice their concerns without fear of reprisal, including possible arrest or mistreatment. The government has effectively silenced any public opposition to the program; there is no mechanism for communities to express their views or have a constructive dialogue; and many indigenous people inside Ethiopia were nervous about speaking to Human Rights Watch for fear of reprisal by the government.

The army or police were present at many, perhaps most, public meetings—an intimidating presence given the longstanding history of military abuses against the local population.[80] The security forces carried out many beatings and arbitrary arrests in a public fashion, perhaps to show what would happen to those that oppose the policy.[81] One resident opposed to the villagization process said: “If we say any of this to them, they twist it and we go to jail.”[82]

One man described what happened to his friend following a public meeting on villagization in Gambella town:

“If people are not being told why, do we have to go?” my friend [name withheld] said at the public meeting. This meeting took place in the day, then in the night, people were beaten by the EDF [Ethiopian Defense Force, army] and accused of mobilizing farmers against villagization. Two of my friends were beaten, arrested, and taken to hospital [he showed photos of two beaten friends]. The next day there was another meeting. And my friend [who had spoken up the day before] got emotional at the meeting. When the meeting was over the EDF followed him into town at night and shot him from behind through the neck [showed photograph]. The two army officers were at the earlier meeting.[83]

The Ethiopian government has permitted very little media coverage of the program within Ethiopia. As a result, outside of affected areas there appears to be very little if any awareness of the program among ordinary Ethiopians. International media attention has also been stifled, with journalists subjected to questioning when staying in villages in areas where villagization is taking place. A Human Rights Watch researcher was questioned by woreda officials who told him, “We hear that foreigners are poking around trying to find out about villagization, and taking what villagers say, twisting it, and making our government look bad.”[84]

Fear of speaking out about the villagization program and the suppression of information and dissent also extends to government employees. According to former civil servants who spoke to Human Rights Watch, many government employees are afraid to say anything for fear of losing their job or other forms of reprisal. For those who expressed concern about the program or seek clarification, the outcome was threats, demotion, or, in at least three cases known to Human Rights Watch, arrest.[85]

A regional government worker, who was demoted twice and eventually imprisoned for three months for questioning villagization, explained:

I asked “Why do people need to go?” If you ask this then they will target you. I said “We should consult with them to see what they want, then it could be successful. They told me I was anti-government: “We have told you to go and tell the villages. You have refused. From this day on we will study you and your background.” Once you raise a question you are always targeted from regional to village level and your name will be recorded.[86]

If villages resisted in any way or the program was not being carried out as quickly as desired, woreda or other junior government officials were targeted and blamed for the problems. Often this targeting took the form of demotion, firing, or occasionally arrest.[87] This happened at both the regional level and the woreda level. A former woreda development agent told Human Rights Watch:

Farmers in our woreda did not want to go. The woreda reported to the region that farmers are refusing to accept. The governor asked the woreda chairman to investigate. He did—“Yes, they are resisting. What shall we do?” he asked the governor. The governor told him that five development agents should be suspended from their job, and that he will bring in the soldiers. So that is what happened. [88]

Arbitrary Arrest and Detentio n

The Ethiopian government has arrested individuals who expressed concern about the villagization process during meetings, traditional leaders of “anti-villagization” communities, and elders or young men accused of “inciting people to refuse.” In several woredas where communities were not cooperative, government officials were also detained or arrested. Human Rights Watch received credible accounts of arbitrary arrests in 9 of the 16 villages we obtained testimony from; the overwhelming majority were men who had spoken up during the initial meetings.

Those arrested have typically been detained for under two weeks, though some have been held much longer. Human Rights Watch is unaware of any of these individuals being charged with any offense, or appearing before a judge.[89] Many of the arrests appear to have been carried out publicly, and appear to have been used as a tool to intimidate and instill fear among the rest of the population.

Human Rights Watch interviewed three community leaders who were detained for openly questioning the government’s policy during the meetings. They were not charged, were never brought before a judge, and were released after several weeks on the condition that they would support the moves, would no longer speak out against the policy, and would mobilize their community to move.[90] Another community leader said:

In our village, old men were arrested because they expressed concern—five of them. They were told they were “anti-villagization.” They are still in Gambella prison since [their arrest] around November [2010]. These village heads had a private meeting and they decided against villagization, and they would tell government when they came. They told them two weeks later, and they were arrested for “not being cooperative.” [91]

Beatings and Assaults

There have been many reports of government soldiers assaulting and beating people during the villagization process. Available information suggests that the overwhelming majority of these beatings happened when people expressed concern about villagization during meetings, or when they actually resisted when it was time to move. This happened mainly between October 2010 and January 2011 in many villages, including almost all of the villagized areas in Dimma and Gog woredas; Ukuna and Chobokir in Abobo woreda; Opagna and Wan Carmie in Gambella woreda; and around Gambella town.

Many beatings also took place during construction of the tukuls in the new villages, where displaced people were forced to build their own new homes. Soldiers supervised the building of these tukuls; in some cases soldiers were camped out near the villages, in other cases they would arrive in the morning and leave in the evening. In these cases, soldiers were there to intimidate and ensure that the villagers built their tukuls swiftly. If villagers were too slow or were seen talking in a group, they became potential targets for beatings and assaults by government troops. Often this would involve a kick, slap, punch, or hitting with the butt of a rifle, but other times the beatings would be more severe. According to one villager:

During construction, there were three situations in which you were beaten: one, if you are found outside the construction area; two, are sitting in a group; or three, if two people are seen talking. ‘You are mobilizing,’ they would say. More than 10 were beaten in our village and most of them ran off and haven’t returned. It was mostly men beaten.[92]

Human Rights Watch documented at least seven credible accounts of people dying as a result of the beatings inflicted by the military and heard of many more that could not be corroborated. One resident said:

My father was beaten for refusing to go along [to the new village] with some other elders. He said, “I was born here—my children were born here—I am too old to move so I will stay.” He was beaten by the army with sticks and the butt of a gun. He had to be taken to hospital. He died because of the beating—he just became more and more weak. Two other villagers were taken to Dimma prison.[93]

The military appears more likely to use violence against relocated villagers in less populated areas. For example, more arbitrary arrests, beatings, and deaths were reported in remote Dimma than in relatively more populous Gambella town. Most of those reported beaten in the new villages were village leaders or young men, although women and children were also occasional victims of beatings. One eyewitness said:

One day I went to visit relatives at a [neighboring village]. I immediately saw the mobilization of people to cut trees. It was almost 5 p.m. One of the community leaders expressed concern at the late start.… This person was then beaten in front of everyone and taken away. His hands were tied behind his back, he was beaten as people watched. They were unable to do anything, afraid to intervene. Police and woreda officials were also involved in this beating; they said he was “anti-villagization.” He was held in jail for one month. There are eight of them that are in danger in that village and are being intimidated by the army because they were accused of forming an anti-villagization group.[94]

News of the military’s targeting of young men—considered to be the biggest threat to the authorities—has spread throughout the region. In some communities elders have told young men not to come to the government meetings to avoid interacting with the soldiers, while in many villages young men have just fled into the bush and to South Sudan.[95] A young villager said:

When I went back to my old village to gather belongings I was told [by a soldier] “Why are you here? You are thieves.” I was then beaten with sticks, and I still have chest pain. The day before this a friend was killed by soldiers. He was beaten with guns and sticks, was vomiting blood and died before we could treat him. He was 19 [years old]. Anuak were crying during the beating but no one could intervene—there were many soldiers there—and we are scared of them. [96]

A woman, formerly of Gog Depache, said:

There was one day we were sitting under the trees, eating green cabbage. Soldiers called five boys and just beat them badly—three were taken to hospital, two of them died. The other three are still in serious condition. There were eight arrests. If you cry for someone who has been arrested or beaten they say, “He is a shifta [bandit].” They are still in prison. After witnessing all of this I fled. People are showing up dead along the roadside or in villages. Two old men were found dead along the road-they were the ones who had expressed concern at the meeting. Their throats had been cut. Those that were arrested were those that expressed concern and those that tried to go back to their farms. [97]

Rape and Sexual Violence

Human Rights Watch learned of many instances of rape and other sexual violence by soldiers connected to villagization, and at least one instance of girls being abducted by soldiers to become their “wives.”

Few young men inhabit the new villages created under the villagization process. Many have gone back to their original areas to farm. Others have fled military abuses that are frequently directed at them. The net effect is that in many of the new villages, women, children, the sick, and the elderly are left largely to themselves. Without the presence of male villagers the women have been at greater risk of rape and other sexual violence from soldiers. Rapes appear to occur particularly in areas where women are isolated and alone, and after dark.

The lack of available water at the new villages has increased the risk of sexual assault as women are walking longer distances to access water sources. Human Rights Watch is aware of about 20 rapes in three areas, most of which were alleged to have occurred when women were alone or travelling long distances to access water. Most of the rapes were alleged to have involved more than one soldier. Victims of sexual assault with whom Human Rights Watch spoke displayed various visible injuries. There were also multiple interviewees from one village that told us that when the army left after tukul construction, they took with them seven girls to become “their wives.” One eyewitness said:

When the soldiers finally left after the construction period they took seven young girls with them “for forced marriage.” They took them back to the Highland areas. I know the girls personally. They were taken right in front of their parents. They did not resist because the soldiers have guns. They were all taken in the same day, just at the end of construction.[98]

At the time of the interviews there was no information of the girls having been returned to their village.

Violations of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

Infrastructure Commitments

The government of Ethiopia contends that villagization is being undertaken to ensure more efficient delivery of services to rural populations. But failure to provide promised infrastructure was a major failing of Ethiopia’s past resettlement and villagization efforts and remains so today.[99] In at least 7 of the 16 villages visited by Human Rights Watch, residents were being moved from villages where infrastructure—schools, clinics, access to water—existed and was operational, to villages where infrastructure was non-existent.

In the new villages, villagers either were doing without this critical infrastructure or were walking to their old villages to access necessities. The government’s claim that it is improving infrastructure is belied by the return of so many villagers to their old homes to access food, water, and health care. Some government officials have conceded that they did not have a budget to put the infrastructure in the new villages in place. [100] But there are indications that the 56 million Birr (US$3.3 million) needed for the first year of infrastructure provision was provided by foreign donors, so it is not clear how these funds were spent. [101]

Of the 12 communities Human Rights Watch visited that were part of the government’s implementation plan,[102] infrastructure provision was planned to involve thirteen water schemes, seven flour mills, eight warehouses, two new health clinics, and two primary schools, along with roads and other public goods.[103] Visits to these villages revealed that just two water schemes were operational. One new school and one clinic in Tegne, Abobo woreda, had been built but were not operational. The buildings for the grinding mills were built in Atangi, Itang woreda, and Perbongo, Abobo woreda, but were not operational.

It is conceivable that the promised infrastructure and service delivery were provided to these villages since the time of the Human Rights Watch May 2011 visit, however the government plan identified the importance of having this infrastructure in place prior to villagers moving “when possible.”[104] For many of these communities the lack of infrastructure means that children are now not going to school, food is not available locally, illnesses are going untreated, and livelihoods have been decimated.

Right to Food and Food Security

In this village, we used to hear the pounding of maize all the time. Now listen, … you hear nothing.… The silence is deafening.

—Elder in Gambella woreda, May 2011

One of the most common concerns voiced when government officials and soldiers showed up saying it was “time to go” was that communities were often just getting ready to harvest their maize crops, the staple of Anuak diets. Several villagers told Human Rights Watch that soldiers told people to come back for their crops at a later time. For example, a man in Dimma woreda said soldiers told them: “You must go now. Do not worry about your crops. You can come back for them after you have built your houses.”[105]

Residents were usually not able to leave their new villages until the army departed. In almost every situation investigated by Human Rights Watch in which people were allowed to return to their original homes, they found that the maize crop had been destroyed by baboons, termites, or rats. In short, the timing of villagization could not have been any worse for those being moved. While individual experiences of villagization in Gambella vary largely among the woredas, the overwhelming majority of forced movements occurred precisely at or just before harvest time—a critical time for the communities. The livelihood disruption from the resettlement of villagers during harvest time was one of the major international criticisms of Derg-era resettlement programs, but the lesson appears to have been lost on the current Ethiopian government.[106]

A new village with land for maize cleared by hand by villagers, despite government promises to have such land cleared.

One of the government’s commitments to the residents of new villages was the provision and clearing of adjacent land on which food could be grown. [107] Officials also pledged to provide food assistance for between six to eight months until the transition had been made to a more sedentary form of agriculture in place of shifting cultivation or agro-pastoralism. [108] In addition, communities were promised training in the necessary farming techniques as well as input provision (seeds, etc). The government villagization plan suggests that three extension workers would be posted in each village to assist with implementation. [109]

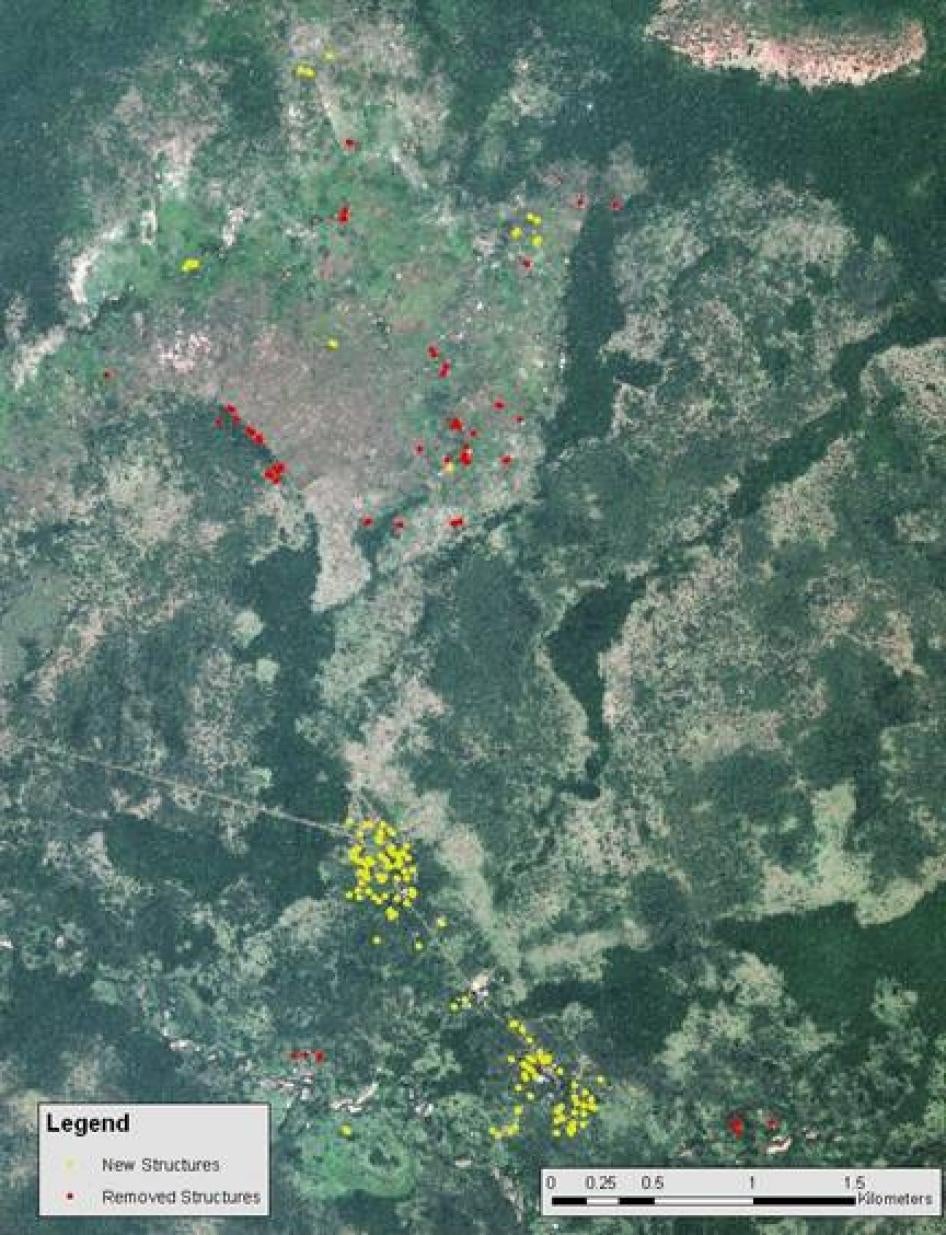

Evidence of Rural Displacement and Villagization in the Akuna Area

©2011 GeoEye, Inc. Location: 7°53’06”N, 34°39’27”E. In October 2011 villagers were told they were to be relocated from their existing homes to the village of Akuna: “In this location we have had more than enough food for the last 10 years, and enough now. [In the new location] there will be no food. They say there will be lots of water, small place for tukuls, and backyard for vegetables. They said they will provide relief food for the rest, but they never keep their promise, and here we can grow our own food.” There was a verbal commitment from government to the villagers of four hectares of cleared land per household. The Regional Government Plan states that land would be provided for each household “up to 3-4 hectares.” The image shows that 68 scattered structures in the area surrounding Akuna that were present in June 2009 no longer existed in December 2011. During that period an additional 124 structures were constructed in the central village of Akuna. Major infrastructure already existed in Akuna prior to villagization. No evidence exists in the images of any new infrastructure. |

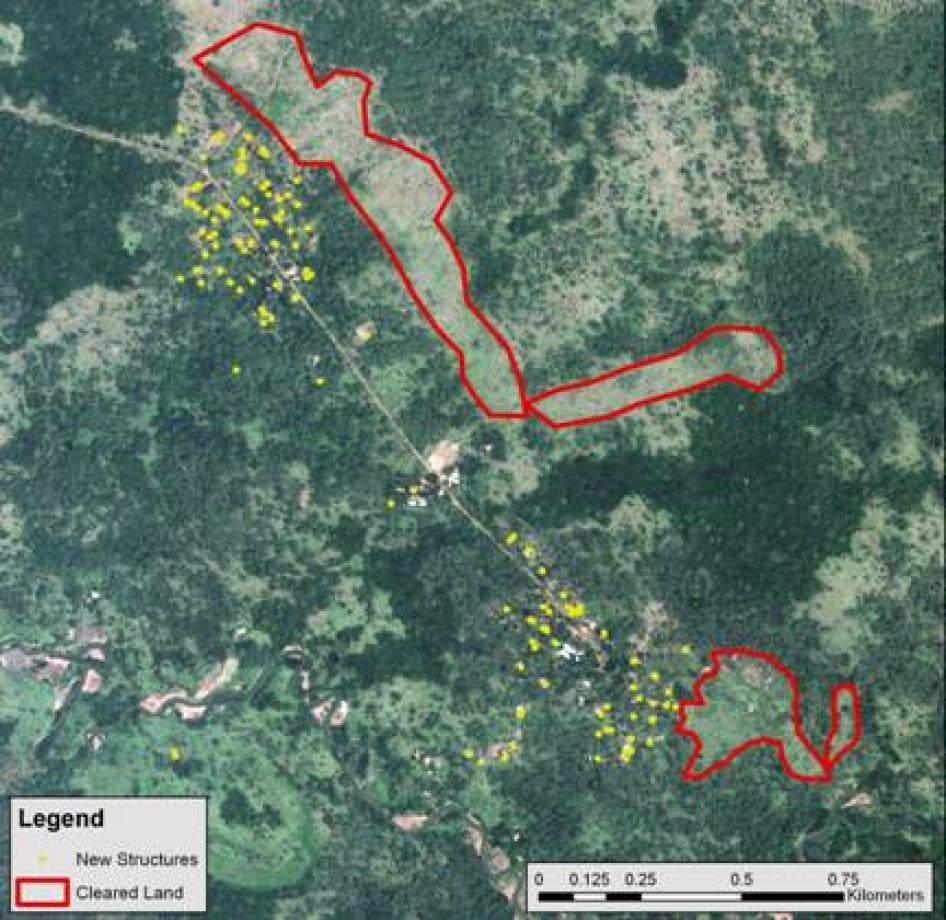

Cleared Land in Akuna Area

Image ©2011 GeoEye, Inc. Location: 7°53’12”N, 34°39’23”E. There was a verbal commitment from government to the villagers of four hectares of cleared land per household. The Regional Government Plan states that land would be provided for each household “up to 3-4 hectares.” In contrast to this pledge, villagers were told in April 2011 that 0.5 hectares would now be given for every two households. The lower red figure shows the area that was cleared adjacent to the new structures for agriculture: 32 hectares for 124 structures, which approximates to 0.25 hectares per household. A woman at a new village said: “We expect a major starvation next year because they did not clear in time. If they cleared we would have food next year but now we have no means for food. We are starving. They promised food-enough and excess for the first eight months, then no more [after 8 months] we would be on our own. But they have brought virtually nothing. Half a hectare is not nearly enough for a family. So after we came to [Akuna to] build tukuls, both men and women, we went back [to our old farms] to get our maize and it was gone—the termites had taken care of it all.” |

Removed Structures in Akuna

June 2009. Image ©2011 GeoEye, Inc. Location: 7°54’36.2”N, 34°38’53”E.

December 2011. Image ©2011 GeoEye, Inc. Location: 7°54’36.2”N, 34°38’53”E. In 2009, the Akuna farming community is visible, with multiple small structures visible near small agricultural fields. By late 2011, however, all these structures are missing (indicated by circles), and the adjacent fields have been abandoned. |

The regional plan states that households will have access to “up to 3-4 hectare[s]” and the letter from Minister of Federal Affairs Shiferaw Teklemariam to Human Rights Watch states that “through villagization program, a household is given an average of four hectares of land.”[110]Of the 16 communities where we obtained testimony none had received inputs and only two had any land cleared. In one of these communities, clearing was being done when Human Rights Watch visited, and the other village had cleared just 0.5 hectares (1.2 acres) per household for one-half of the households.[111] One woman complained about the lack of clearing: “The officials need to come with a grader. We are not forest people, we do not know how to cut trees. They need to clear.”[112]

Approximately one-third of these villages had received one small delivery of food (which seemed to last about two weeks), while the remaining two-thirds had no food deliveries at all. One villager expressed his sense of desperation:

The government is killing our people through starvation and hunger. It is better to attack us in one place than just waiting here together to die. If you attack us, some of us could run, and some could survive. But this, we are dying here with our children. Government workers get this salary, but we are just waiting here for death.[113]

The United Nations World Food Program (WFP) runs a program for “targeted beneficiaries” in some of the more food-insecure areas of Gog woreda. As part of their food deliveries under this program in chronically food-insecure areas, there were several food deliveries to the new villages. There were several accounts of woreda officials intercepting this food aid and eventually delivering it themselves to the affected populations. It is not clear how much of the intended assistance actually made it to the intended recipients. Human Rights Watch documented the politicization of food aid and food-for-work programs in various regions of Ethiopia in 2010.[114] A resident of Gog told Human Rights Watch:

The government would not provide food if people did not come [to the new villages]. There was a tiny distribution of wheat at first. When they saw people starting to come to the village they stopped distribution [of food]. Then the World Food Program came with 50 kilograms [of wheat] for every three families, as well as some beans. We had to collect from [nearby village], but then the woreda interfered and handed out [the WFP food deliveries] themselves.[115]

Many of the new villages are in areas known to the residents. They had left these lands in the past because the soil was no longer fertile. In many other areas, vegetation is dense and large trees are present, making the area difficult to clear, particularly for a malnourished and often elderly population. This lack of clearing and the late arrival of the rains for the third straight year meant that, as of mid-2011, most farmers had not planted their crops; they usually would have been planted one to two months prior to this time.

“We expect major starvation next year because they did not clear in time,” said a resident of Abobo. “If they cleared we would have food next year but now we have no means for food.” [116]

The disruption at harvest time, the lack of any food reserves, the lack of food aid, and the lack of planting for the upcoming season (maize would be ready for harvest in approximately four months) is making an always precarious food security situation much worse. Almost every villager Human Rights Watch spoke to in Gambella said that the biggest problem they are facing with the villagization process is the lack of food. Seemingly out of touch with the reality in the villages, the minister of federal affairs told Human Rights Watch in December 2011 that “The villagers for the first time in their history started to produce excess product—maize, sorghum, rice, potatoes, beans, vegetables, fruits, etc.—beyond and above their family consumption.”[117]

Perbongo Settlement Increase