Prosecuting Political Aspiration

Indonesia’s Political Prisoners

Maps of Prisons with Political Prisoners in Indonesia

Summary

The judges should have deemed his action more as a political aspiration than a life-threatening act.... He only waved an RMS flag, and did not carry a weapon.

—Asmara Nababan, former secretary-general of the National Commission on Human Rights in Jakarta, speaking about the prosecution of Johan Teterisa.

Indonesia has made important progress in strengthening democracy and respect for human rights since the end of authoritarian rule under President Suharto in 1998. Advances have included permitting increased freedom of association and assembly, holding three generally free and fair national elections, and providing greater overall protection for civil and political rights.

Improved freedom of expression has been hailed as emblematic of this progress. While there have been notable accomplishments—700 new magazines and newspapers sprung up in the first three years after Suharto’s ouster alone—the right to free speech in Indonesia continues to be limited in three significant ways:

- Laws criminalizing defamation and insult remain in the criminal code and are used to silence anti-corruption activists, human rights defenders, journalists, consumers, and others.[1]

- The government continues to criminally prosecute people who express religious beliefs that deviate from the central tenets of six officially recognized religions; heterodoxy and public adherence to unrecognized religions are officially illegal.[2]

- The government continues to criminally prosecute peaceful expression of pro-independence sentiment by ethnic minority activists in Papua and the southern Moluccan islands.

This report focuses on this last area. It profiles the cases of 10 prominent Papuan and Moluccan activists currently behind bars for expressing their political views, detailing ill-treatment they have suffered and violations of their due process rights. In total there are currently at least 100 Papuans and Moluccans in prison in Indonesia for peaceful political expression.

Human Rights Watch takes no position on claims to self-determination in Indonesia or in any other country, and nothing in this report should be construed as supporting or denigrating the independence aspirations of Papuan or Moluccan activists. Consistent with international law, however, we support the right of all individuals, including independence supporters, to express their political views peacefully without fear of arrest or other forms of reprisal.

President Suharto was notorious for arresting and imprisoning those who opposed him, from Communist party members and sympathizers in the early years to critics of all stripes, including ethnic minority pro-independence advocates, in his later years. Under Suharto, Indonesian authorities failed to distinguish between acts of criminal violence and peaceful expression of separatist views, contributing to political polarization and fueling radicalization in East Timor and Aceh. While those latter conflicts have been resolved through political agreements and thousands of political prisoners have been released since Suharto’s resignation, the practice of lumping together peaceful advocates and armed militants and treating both as criminals continues in Papua and the southern Moluccas.

Most of the cases detailed in this report are of activists imprisoned for organizing rallies or participating in ceremonies in which flags were raised symbolizing aspirations for an independent state in Papua or in the southern Moluccan islands. In December 2007, the Indonesian government issued Government Regulation 77/2007, which regulates regional symbols. Article 6 of the regulation bans display of flags or logos that have the same features as “organizations, groups, institutions or separatist movements.” Both the Papuan Morning Star flag and the “Benang Raja” (rainbow) flag of the Republic of the South Moluccas (Republik Maluku Selatan, RMS) are considered to fall under this ban.[3]

Most of the political prisoners in Indonesia were convicted of makar (rebellion or treason) under articles 106 and 110 of the Indonesian Criminal Code. Many were sentenced to 10 years or more in prison. In several cases the activists were tortured by police while in pre-trial detention. Some have faced mistreatment and denial of medical treatment while in prison.

Moluccan activist Reimond Tuapattinaya, first detained in June 2007, described being tortured immediately following his arrest:

If they held an iron bar, we got the iron bar. If they held a wooden bat, we got the wooden bat. If they held a wire cable, we got cabled. Shoes. Bare hands. They used everything. The torture was conducted inside Tantui and the Moluccan police headquarters. I was tortured for 14 days in Tantui, day and night. They picked me up in the morning, and returned me, bleeding, to my cell in the evening.

The cases profiled here also illuminate a larger problem: according to activists, media reports, and statements by some officials, more than 100 pro-independence activists from these two regions are currently imprisoned for peaceful expression. We are not able to confirm the exact number of prisoners held solely for peaceful expression of their views because in many cases, court documents detailing the basis for imprisonment are not publicly available. But the cases here demonstrate that authorities continue to arrest and prosecute pro-independence activists for non-violent actions such as raising flags and organizing rallies and that these actions reflect current government practice.

* * *

Freedom of expression is protected in Indonesia’s constitution and international human rights law. The constitution in article 28(e) states, “Every person shall have the right to the freedom of association and expression of opinion.” Article 28(f) provides, “Every person shall have the right to communicate and obtain information for the development of his/her personal life and his/her social environment, and shall have the right to seek, acquire, possess, keep, process, and convey information by using all available channels.”

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Indonesia ratified in 2006, also protects the right to free expression. Under article 19, “[e]veryone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.”[4]

Secession movements can pose legitimate national security concerns, and in limited circumstances, justify restrictions on the free speech rights enumerated immediately above. Article 19 of the ICCPR states that these rights are “subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary: … For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.”[5]

Whether any particular expression of ethnic nationalism or support for secession poses a national security risk will depend on the circumstances prevailing at the time.

The 1995 Johannesburg Principles on National Security, Freedom of Expression, and Access to Information elaborates widely accepted standards on national security restrictions:

Principle 5: No one may be subjected to any sort of restraint, disadvantage or sanction because of his or her opinions or beliefs.

Principle 6: [Apart from legitimate state secrets,] expression may be punished as a threat to national security only if a government can demonstrate that: (a) the expression is intended to incite imminent violence; (b) it is likely to incite such violence; and (c) there is a direct and immediate connection between the expression and the likelihood or occurrence of such violence.[6]

In the cases detailed in this report, the government did not demonstrate the threat of imminent violence or the presence of a nexus between speech and violence.

Recommendations

Human Rights Watch urges the Indonesian government to immediately and unconditionally release all persons whose cases are detailed in this report, and all other prisoners held for peaceful expression of their political views. To the extent that any such individuals are also alleged to have engaged in acts of violence or illegal trespass, they should be given a new trial in accordance with international standards and credited with time served.

We also urge that the government amend or repeal all articles of the Indonesian Criminal Code that have been used to imprison individuals for their legitimate peaceful activities, including articles 106 and 110 of the Criminal Code on “rebellion,” to bring Indonesian criminal law into conformity with international standards. As currently written, the law allows for prosecution of those engaged in peaceful advocacy of independence.

The reformed legal framework Indonesia adopts for pro-independence expression should be consistent with the Johannesburg Principles and be accompanied by an explicit public commitment not to prosecute individuals merely for raising the Morning Star or RMS flags. The law should make a clear distinction between display of pro-independence symbols in private homes and property, which should not be subject to government interference, and display in government offices and property, which the authorities have the discretion to regulate.

The Indonesian government should revoke article 6 of Government Regulation No. 77/2007, which prohibits the display of separatist logos or flags, or bring it into compliance with international human rights standards and the Indonesian constitution.

Authorities should promptly respond to credible reports of torture in custody by conducting thorough and impartial investigations and hold legally accountable all those responsible, and revise rules and practices at jails and prisons to ensure compliance by all security forces with the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.

Finally, we urge that the Indonesian government remove arbitrary restrictions on access to all regions of Papua by journalists and humanitarian and human rights workers.

Concerned governments and inter-governmental bodies also have an important role to play. We urge other governments to push for amendment or repeal of Indonesian laws that allow for imprisonment of individuals for peaceful political expression. Foreign embassy personnel should visit and monitor the situation of political prisoners held at facilities in Semarang, Malang, Porong, Kediri, Nusa Kambangan (Pasir Putih and Kembang Kuning), Ambon, and various locales in Papua such as Abepura, Sentani, Biak, Nabire, Fakfak, Wamena, and Merauke.

The United States and Australian governments should also cease any training for the Detachment 88/Anti-Terror unit implicated in the torture of RMS prisoners after the June 29, 2007 protest in Ambon and press the Indonesian government to investigate and to bring to justice officers responsible for torture.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch collected data about the political prisoners profiled in this report from December 2008 to May 2010, visiting prisons in Papua, the Moluccan islands, and Java. All the interviews except one were conducted by various means by a Human Rights Watch researcher, and in a significant number of cases, the researcher interviewed the prisoner multiple times. Altogether Human Rights Watch directly and indirectly interviewed more than 50 political prisoners in the Moluccas, Papua, and Java. In order to protect against possible retaliation against persons who facilitated the interviews, the actual dates of the interviews have been withheld.

In selecting the cases for this report, we focused on individuals imprisoned for peaceful acts of political expression who do not advocate the use of violence to achieve political or other objectives.

The only case included in this report of someone accused of committing violence is that of Ferdinand Pakage, a political prisoner in Abepura, Papua, who was sentenced to 15 years in prison for the stabbing death of a policeman during riots. Circumstances in his case—he was allegedly tortured to give a confession during the police investigation and there were serious irregularities in his trial—raise concerns about the fairness of his conviction.

Political Prisoners from the Moluccas

Background

A pro-independence movement has existed in the southern Moluccas, centered on the island of Ambon, since 1950, the year after Indonesia gained its independence. Many of the indigenous people of this region call themselves Alifurus. On April 25, 1950, Alifuru nationalists in the All Southern Moluccas Council, led by Chr. R.S. Soumokil, held a national conference on Ambon Island and proclaimed the creation of the independent Republic of the South Moluccas (Republik Maluku Selatan, RMS). President Sukarno’s decision later that year to disband the federal Republic of the United States of Indonesia in favor of a more centralized Republic of Indonesia gave further impetus to Moluccan separatism.

In response to the RMS proclamation, the Indonesian government sent troops to Ambon, conducting military operations that largely dispersed the rebellion by November 1950 but which continued until the final defeat of the RMS in 1966. Many of the surviving RMS leaders fled into exile in the Netherlands where they formed a government-in-exile that continues to this day.

While the RMS does not today enjoy broad support in the Moluccas, nationalist sentiments have continued in pockets in the region. Issues of independence and sovereignty were inflamed by religion-based communal conflicts between the predominantly Christian Alifurus and Muslim migrants from Java and Sulawesi (migration that for many years was encouraged by the Indonesian government). Sectarian violence erupted in January 1999 in Ambon and later spread throughout the archipelago, continuing through 2005. Thousands of people were killed and tens of thousands displaced by the violence.[7]

An Ambonese man named Alex Manuputty established the Moluccan Sovereignty Front (Front Kedaulatan Maluku, FKM) in December 2000, claiming the conflict could only be resolved if the Moluccas achieved independence and endorsing the establishment of an independent Republic of the South Moluccas.[8] Moluccas Governor Saleh Latuconsina officially banned the FKM in 2001.

Raising the RMS flag, especially on the April 25 anniversary of the founding of the RMS in 1950, has become a major method of expressing public disapproval of Indonesian rule and many Moluccan political prisoners have been arrested following flag-raising ceremonies. But some of the harshest penalties were meted out to a large group who unfurled RMS flags during the June 29, 2007 celebration of National Family Day in Ambon attended by President Yudhoyono and foreign dignitaries. Three of the political prisoners whose cases are profiled below were among those involved in this incident.

Tim Advokasi Masyarakat Sipil Maluku (Tamasu), an organization working to assist Moluccan prisoners, reports that there are currently 70-75 individuals in prison for their involvement in the RMS cause.[9] Human Rights Watch did not have access to all the charge sheets, verdicts, or other legal papers and so cannot state definitively that all 70-75 are in prison for exercising their right to peaceful expression of their views, but it is clear from our interviews and press accounts that the vast majority fall into that category. The prisoners include 21 of the 28 persons arrested for involvement in the June 29, 2007 event as well as other activists involved in RMS flag-raising and other forms of political expression.

The 2007 Flag Unfurling and Its Violent Aftermath

On June 29, 2007, during the National Family Day festivities at Merdeka Stadium in Ambon, 28 Alifuru dancers entered the tightly controlled stadium, danced the cakalele traditional war dance, and unfurled the banned RMS flag. A school teacher, Johan Teterisa, led the dancers, who mostly came from Aboru village, Haruku Island, east of Ambon. The incident publicly embarrassed President Yudhoyono in front of his foreign guests, and when he spoke after the dance he told the audience that there is “no tolerance” in Indonesia for separatism.

Local officials reacted by immediately arresting a number of the dancers[10] and taking them to the counter-terrorism police Detachment 88/Anti-Terror headquarters in Tantui, Ambon.[11]

Ambon police then launched a major crackdown against the RMS and arrested about 100 alleged activists. Teterisa and Ferdinand Waas, the raja (hereditary chief) of Hutumuri village in Ambon who aided and advised the dancers, were prosecuted for treason and received long prison terms.

According to Teterisa, Detachment 88/Anti-Terror police officers demanded that he sign a statement calling on the Moluccas Sovereignty Front (Front Kedaulatan Maluku, FKM) to disband. The FKM is a banned organization that promotes the creation of an independent RMS, and Teterisa is an FKM board member in Aboru, Haruku Island.

He says that when he refused to sign the document, police beat him almost continuously for at least 12 hours every day for 11 days. Several beat him with iron rods and stones, and slashed him with a bayonet. On June 30, 2007, four Detachment 88 officials beat him repeatedly with sticks and outside the unit’s office, kicked and pushed him down to the nearby Ambon sea, and continued beating him in the water. In another instance, officials kicked Teterisa out of a second floor room and down a set of stairs. Teterista told Human Rights Watch that his chest was crushed, a number of his ribs were broken, and he was covered with black bruises.[12]

When the interrogators realized that torture was not working to compel Teterisa to sign the letter, other officials came in and tried a softer approach, saying if he signed the letter, the Ambon government would provide some funding to increase fisheries in Teterisa’s home area of Aboru. He refused. The officials then offered to guarantee that if Teterisa cooperated, they would provide support for Teterisa’s three young sons to finish their education up to the college level, but he again refused.

At 11 p.m. one night in July 2007, some officers brought him to Merdeka Stadium to see the dancing site. He was handcuffed and walked there at gun point. He told Human Rights Watch: “I kept on praying. I expected to be slaughtered that night.” He said this was because “I have refused their request. The Indonesian media in Ambon also put so much pressure on me. I think they had only one option left: killing me.” The officers never removed his handcuffs but Teterisa said that he was shown to a higher ranking official who was not identified, and then taken back to detention.

Police arrested Moluccas activist Reimond Tuapattinaya on July 2, 2007. The police had previously raided a house that they suspected was being used by the National Family Day dancers, and found a DVD showing Tuapattinaya involved in a flag-raising ceremony in the Siwang area, outside of Ambon. Members of the Detachment 88/Anti-Terror squad tortured him extensively for 14 days in their headquarters in Tantui, Ambon.

Tuapattinaya told Human Rights Watch, “We were tortured worse than Jemaah Islamiyah [militant Islamist] activists. We were stripped naked, only in our underwear, forced to sleep directly on the tile floor. Early in the morning, we were ordered to crawl. We were kicked, beaten, trampled. If they held an iron bar, we got the iron bar. If they held a wooden bat, we got the wooden bat. If they held a wire cable, we got cabled. Shoes. Bare hands. They used everything. The torture was conducted inside Tantui and the Moluccan police headquarters. I was tortured for 14 days in Tantui, day and night. They picked me up in the morning, and returned me, bleeding, to my cell in the evening.”[13]

“One of them [involved in the torture] was the detachment commander…. He’s not an Ambonese,” Tuapattinaya told Human Rights Watch. “But most of the detachment interrogators were Ambonese. They all wore civilian clothes.”[14]

Three brothers—Arens, Ruben, and Yohanis Saiya—also took part in raising the RMS flags during the event on June 29, 2007. They were arrested and taken to Detachment 88 headquarters, where the police beat all three of them with pieces of wood and iron bars, kicked them with their boots, and banged their heads against walls. The Saiya brothers told Human Rights Watch that intelligence officers in plain clothes served as their interrogators.

Arens Saiya, the eldest of the three, suffered internal bleeding in his intestine and urinary system, according to his medical records. He said many of the interrogators were non-Ambonese officers, including the commander. “I was tortured severely, more than a terrorist, when all I did was dancing cakalele.” He said he received minimal medical treatment when he was hospitalized in a Semarang hospital in March and May 2010. He continues to have difficulties urinating.[15]

Police at Detachment 88 beat Ruben Saiya so severely that they broke his ribs and caused profuse bleeding from his head. He was denied medical treatment for his injuries. Today, years after those beatings, Ruben said he still suffers the effects: “I have headaches now. It is difficult to sleep.” They also dragged him to the nearby coast of the Ambon sea and repeatedly dunked him in the water—a form of torture similar to “water-boarding.” Ruben told Human Rights Watch that as a result of his questioning, he was basically “shattered, shattered.” He said, “There are no more parts of my body that they had not beaten. We were beaten and made to crawl on the asphalt with our chests.” He said he continues to suffer the effects of his past torture, and often spits up blood in his current imprisonment at Kembang Kuning prison on Nusa Kambangan Island. He is serving a 20-year prison sentence. Their youngest brother, Yohanis, was a teenager when police arrested and tortured him. He is now held with Ruben at Kembang Kuning prison.[16]

The authorities have also tortured other RMS pro-independence activists involved in peaceful actions less high profile than the actions at Merdeka Stadium on June 29, 2007. Often these actions involve raising the RMS flag in public, especially on or around April 25th, the anniversary of the proclamation of the RMS.

Leonard Hendriks, another RMS activist, said that he suffers from constant headaches on the right side of his head and face. Hendriks said the Indonesian police in Tantui beat him with their bare hands on the right side of his head and burned him with cigarettes. He is currently in prison in Malang.[17]

Another RMS prisoner, Johny Sinay, says he sometimes requires a wheelchair because of injuries suffered when police tortured him in Tantui. In late 2009, he collapsed in his Malang prison cell as a result of weakness in his legs which he attributes to the beatings he suffered to his legs, thighs, and back. Sinai asked officials at Malang prison to allow a medical specialist to evaluate his nervous system, but the request was denied.[18]

Police arrested Frejohn Saiya, now in Malang prison, after he took part in a RMS flag-raising. He said police tortured him for six days at the Detachment 88 headquarters in Tantui. At that time, he had long hair and he told Human Rights Watch that interrogators grabbed his hair, repeatedly banged his head against walls, and hit him with an iron rod. Police forced him to sleep on bare prison floors in his underwear.[19]

Lowokwaru prison in Malang, East Java, where six RMS political prisoners are currently imprisoned. Prisoners are not provided with safe drinking water and instead must drink unhealthy prison tap water. Some still suffer from health problems caused by police beatings during interrogations in Ambon in 2007. ©2009 Human Rights Watch

Individual Case Profiles

Johan Teterisa

Johan Teterisa, born 1961, was an elementary school teacher in Aboru village, near Ambon, before he was imprisoned. He is a member of the RMS and on April 3, 2008, was sentenced to life in prison for treason. His purported crime was leading 27 other dancers holding RMS flags to protest Indonesian rule on June 29, 2007, in front of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono at Merdeka Stadium in Ambon. All of the dancers were immediately arrested and taken to the police Detachment 88/Anti-Terror headquarters in Tantui, Ambon, where they were subjected to torture.

State prosecutors charged Teterisa and more than 50 of his colleagues with treason under articles 106 and 110 of the Indonesian Criminal Code. An Ambon district court found him guilty and sentenced him to life imprisonment. Teterisa says he was shocked when he heard the judges pronounce the verdict of life imprisonment. Asmara Nababan, a former secretary-general of the National Commission on Human Rights in Jakarta, said the Ambon judges had failed to consider that Teterisa’s actions were non-violent. “The judges should have deemed his action more as a political aspiration than a life-threatening act,” Nababan told the media. “He only waved an RMS flag, and did not carry a weapon.” The Ambon court also convicted 19 of the dancers of treason, sentencing them to between 10 and 20 years in prison.[20] On appeal, Teterisa’s sentence was reduced to 15 years.

The authorities also targeted his family. His wife, Martha Leonora Sinay, was made a suspect by police who alleged that she knew about an RMS meeting held in the Teterisas’ house in Aboru village. Sinay fled to avoid arrest and hid in the jungle for seven months. Their three sons were forced to go live with relatives.[21] She has now returned and is able to live openly in the village.

On March 10, 2009, the Ambon government unexpectedly transferred Teterisa and 36 other political prisoners, including those imprisoned for the June 29, 2007 action as well as other pro-independent activities, from Ambon to Central Java. From there they were transferred to Porong (seven prisoners), Kediri (six prisoners), Semarang (six prisoners), and Malang (six prisoners including Teterisa himself). Twelve prisoners were sent to Nusa Kambangan Island, located south of Java, with half sent to Permisan prison and the other half to Kembang Kuning prison.

Teterisa told Human Rights Watch that imprisonment in Java makes their lives much more miserable because it is now very difficult for the prisoners to meet their families. Their families cannot afford traveling by air to Java from Ambon, and transport by ferry and land transport is not practical or feasible.[22]

“It’s almost impossible for my wife and my sons to see their father in Malang. It’s too far. And my jail term is 15 years,” said Teterisa.

Reimond Tuapattinaya

Reimond Tuapattinaya, age 41, is an Ambonese who worked as a construction supervisor in Dili, East Timor, from 1991 to 1999. Indonesian police arrested Tuapattinaya on June 2, 2007, after they identified him as participant at the April 25, 2006 RMS flag-raising ceremony in Ambon. Police discovered a DVD film containing images of him at the event and submitted this as evidence at his trial for treason under articles 106 and 110 of the Criminal Code. The Ambon district court sentenced Tuapattinaya to seven years’ imprisonment. He was initially jailed in Ambon but then was transferred to Kediri prison, East Java, on March 11, 2009.

Tuapattinaya was born in Itawaka village on Saparua Island, off the southern Ambon coast, on January 1, 1969. His parents were farmers. After graduating from a technical school in 1990, he got a job as a supervisor at a construction company in East Timor, then under Indonesian rule.

He was not involved in politics until the fall of President Suharto. In January 1999, President B.J. Habibie, Suharto’s successor, allowed the East Timorese to hold a referendum on independence or remaining an autonomous part of Indonesia. Some East Timorese asked Tuapattinaya for advice on how they should vote in August 1999. “Look at me,” he said he told them. “The Moluccas, my home islands, are very rich but I have to work here. We’re poor under the Indonesians. It’s better if you vote for independence.”

When he returned to Ambon in July 2000, the area was experiencing brutal sectarian violence between Muslims and Christians that would claim thousands of lives between 1999 and 2005.[23] Tuapattinaya believes authorities acted unfairly in handling the riots: “Many soldiers were deployed to Ambon but why was Ambon still burned down? Why did the Indonesian government permit Javanese militias to operate in Ambon? As a Moluccan, I began to think: who is doing right, who is doing wrong?”[24]

He began joining in prayers at Alex Manuputty’s residence in the Kudamati area, a predominantly Christian neighborhood in Ambon. When Manuputty, himself a Christian and a popular doctor, declared the founding of the Moluccas Sovereignty Front (Front Kedaulatan Maluku, FKM) on December 18, 2000, Tuapattinaya volunteered to help.

Indonesian police first arrested Tuapattinaya on April 25, 2 004, after a flag-raising ceremony in Ambon commemorating the 54th anniversary of the RMS. The Ambon district court sentenced him to two years in prison for treason. He was released a year early, on December 25, 2005, for good conduct.[25]

Tuapattinaya continued his political activism after being released from prison until his re-arrest in June 2007. “For as long as the Indonesian government cannot prove to me that the RMS is illegal, under international law, I will not retreat. Injustice against the people of Moluccas continues. I have never backed away from my commitment. I never hurt anyone.”

Now in Kediri prison, he shares a cell with five other RMS activists.

Ruben Saiya

Ruben Saiya is a 27-year-old farmer who was born in Aboru village, Haruku Island, near Ambon. He is now imprisoned in Kembang Kuning prison on Nusa Kambangan Island, off Java’s southern shore. On June 29, 2007, he was one of the 28 dancers who unfurled RMS flags in front of President Yudhoyono. He was arrested and an Ambon district court found him guilty of treason under Criminal Code articles 106 and 110. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison. His two brothers, Arens and Yohanis, also joined the dance protest and they were sentenced for 8 and 17 years respectively and are serving their sentences in Semarang and Kembang Kuning prisons.

Saiyo told Human Rights Watch that the Aboru villagers had decided to dance in a bid to protest their suffering in their own islands. “In the Moluccas, we cannot live a good life. We don’t get a good education. We cannot find work. The Indonesian people have taken over our islands,” he said.

When the Ambon court announced his sentence, his wife, Johanna Teterisa, collapsed in the court room. “I don’t know what to tell her anymore,” said Saiya. Because of the expense and logistical obstacles his wife cannot travel to Java to visit her husband.[26]

Ferdinand Waas

Ferdinand Waas, born in 1948, was an Indonesian Army officer, stationed in East Timor in the 1980s and 1990s. After his retirement at the rank of captain, he joined the RMS. He allowed RMS activists to use his house to plan the pro-independence dance at Merdeka Stadium in June 2007. He was arrested and in October 2007, an Ambon district court found him guilty of treason and sentenced him to ten years in prison.[27]

The Waas are the ruling raja family in Hutumuri village, Ambon. His father, Dominggus Waas, replaced his grandfather as the village raja. Ferdinand joined the Indonesian Army and served at the Ambon-based 731st Infantry Battalion and later with the 733rd Para Battalion.

In 1985, Ferdinand Waas served in East Timor in an Army territorial command post in Manufahi regency. In 1992-1997, the army appointed him to the Same town council in the Manufahi regency.

In 1999, he retired from the army and returned to his village Hutumuri. The villagers asked him to be their raja and in 2005, the Indonesian government officially inducted him as the Hutumuri village head.

At the planning meeting in Hutumuri on June 27, 2007, he advised the Aboru dancers not to bring any metal equipment because such equipment might create the impression that the dancers were planning violence. “Their spears, their swords, were all made from wood,” he said. He also advised the dancers on how to get identification cards to permit entrance to the stadium.

He was arrested along with the dancers at the stadium and detained at the Detachment 88/Anti-Terror in Tantui, Ambon. He said police officers beat him with billiard sticks, pieces of wood, and iron bars. “They knew I was an army captain, so I think they beat me harder, as if I was younger,” he said.

Papuan Political Prisoners

Background

The Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua (referred to collectively here as “Papua”) occupy the western half of the island of New Guinea. Unlike the rest of Indonesia which gained independence in 1945, Papua was under Dutch control until the 1960s.

On December 1, 1961, the Papuan Council, a representative body sponsored by the Dutch colonial administration, declared that Papuan people were ready to establish a sovereign state, and issued a new national flag called the Morning Star.

Indonesia’s then president, Sukarno, had long maintained that Papua should be part of Indonesia and accused the Dutch of trying to create a “puppet state” on Indonesia’s doorstep. In 1962 he ordered Indonesian troops to invade Papua. The US government intervened diplomatically, and after negotiations, Indonesia and the Netherlands agreed to have the United Nations organize a referendum in Papua. The UN-sponsored “Act of Free Choice” took place in 1969, in which only 1,054 Papuans, hand-picked by the Indonesian government, voted unanimously to join Indonesia. Many Papuans consider the “Act of Free Choice” a fraudulent justification for Indonesia’s annexation of Papua.[28]

Over the last five decades, support for independence, fueled by resentment of Indonesian rule, loss of ancestral land to development projects, and the influx of migrants from elsewhere in the country, has taken the form of both an armed guerrilla movement, the Free Papua Movement (Organisasi Papua Merdeka or OPM), and a diverse series of non-violent organizations and initiatives. A common tactic of peaceful pro-independence advocates has been to raise the Papuan Morning Star flag in public ceremonies, particularly on the December 1 anniversary.

After Suharto’s resignation in 1998 the Indonesian government for a time permitted the Morning Star flag to be flown on the condition that it was raised alongside and placed in a lower position than the Indonesian flag. President Wahid deemed the Morning Star flag to be a cultural symbol. Efforts by Jakarta to address Papuan grievances also included granting the region Special Autonomy status in 2001 which involves the devolution of many political and fiscal powers to the province. The law also explicitly allows for public display of symbols of Papuan identity such as flags and songs. However, raising the Morning Star flag is prohibited by government regulation 77/2007 and the Indonesian courts continue to treat the raising of flags associated with pro-independence sentiment as treasonous and, as such, a banned form of expression.[29]

Nazarudin Bunas, the head of the Ministry of Law and Human Rights in Jayapura, Papua, reported that as of February 2010 there were 48 Papuan prisoners convicted of treason.[30]

Individual Case Profiles

Filep Karma

Filep Jacob Semuel Karma, age 51, has been in the Abepura prison for five years. In May 2005, the Abepura district court found him guilty of treason for organizing a pro-independence rally on December 1, 2004, and sentenced him to 15 years of imprisonment.[31] He is married with two teenage daughters.

Karma was born in 1959 into an elite family in Papua. His father, Andreas Karma, was a Dutch-educated civil servant who managed to retain his position under Indonesian rule, and was appointed regent of Wamena in the 1970s and Serui in the 1980s. Filep’s cousin, Constant Karma, is a former Papua deputy governor and now the head of Papua’s AIDS Eradication Commission.

In the early 1970s, Karma often heard his father and uncle talk quietly about the mistreatment of native Papuans under Indonesian rule, which they told him were much worse than the abuses suffered by Papuans under Dutch rule. While in junior high school, Karma wanted to get involved in the Papuans’ struggle using political means rather than violence. In 1979, he studied political science at the March 11 University in Solo, Central Java. He graduated in 1987 and began work as a civil servant in Jayapura.

In 1997, he received a scholarship to take an 11-month course at the Asian Institute of Management in Manila. When he returned to Indonesia in 1998, he travelled in Java and learned about widespread student protests against President Suharto.

On his return to Papua, Karma began to openly advocate for Papua’s independence from Indonesia. On July 2, 1998, he helped organize a large pro-independence rally and raised the pro-independence Morning Star flag on the water tower near the seaport in his hometown of Biak, Papua. A violent clash ensued in which approximately a dozen police were wounded. On July 6, the Indonesian military took control of Biak Island and opened fire on the protesters. The full death toll remains unknown as many bodies reportedly were loaded onto trucks and allegedly dumped in the sea from two Indonesian navy ships.[32] Biak residents claim they recovered numerous dead bodies on the seashore near Biak.

Karma alleges that many bodies were buried locally on small islands near Biak, and he personally estimates that more than 100 protesters were killed. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, the government has continuously failed to carry out a serious investigation of these incidents, or hold accountable the perpetrators of abuses against the people in Biak. Without an independent and impartial investigation to ensure accountability, the memories of those killings will continue to inflame tensions and varied death-toll estimates will continue to circulate.[33]

Karma was wounded on his legs by rubber bullets fired by the military on July 6. The police arrested him and held him in detention from July 6 to October 3, 1998. On January 25, 1999, the Biak district court found him guilty of treason for his leading role and the speeches he gave during the Biak protests and sentenced him to six-and-a-half years in jail. Karma appealed this sentence, won his appeal, and was freed on November 20, 1999.

After his release, he joined the TPN-OPM Forum of Former Political Detainees and Prisoners (Forum Mantan Tahanan dan Narapidana Politik TPN-OPM) whose objectives include helping Papuan prisoners and their families. Their chairman, John Mambor, joined the Presidium Papua Council and headed the pillar group within the council representing former political prisoners.

On November 10, 2001, members of the Indonesian special forces (Kopassus) killed Papuan leader Theys Eluay, the chairman of the Presidium Papua Council. This killing dramatically raised political tensions in Papua. Three years later, Karma helped organize a ceremony on December 1, 2004, to mark the anniversary of Papua’s independence from the Dutch. The event was attended by hundreds of Papuan students, who shouted the word “freedom!” and displayed the Morning Star flag. The chanting at the rally also included calls to reject the Special Autonomy law as insufficient.[34]

When the protesters tried to raise the Morning Star flag, Indonesian police attempted to forcibly disband the rally. Clashes broke out and the crowd attacked the police with blocks of wood, rocks, and bottles. The police responded by firing into the crowd. Karma was arrested immediately and charged with treason, and has remained incarcerated ever since. On October 27, 2005, the Abepura district court sentenced him to 15 years’ imprisonment. His colleague, graduate student Yusak Pakage, was sentenced to ten years in prison.

Today Filep Karma is probably one of Papua’s most popular pro-independence leaders. He has never advocated violence as a means of obtaining that goal. He said, “We want to engage in a dignified dialogue with the Indonesian government, a dialogue between two peoples with dignity, and dignity means we have no use of violence.”[35]

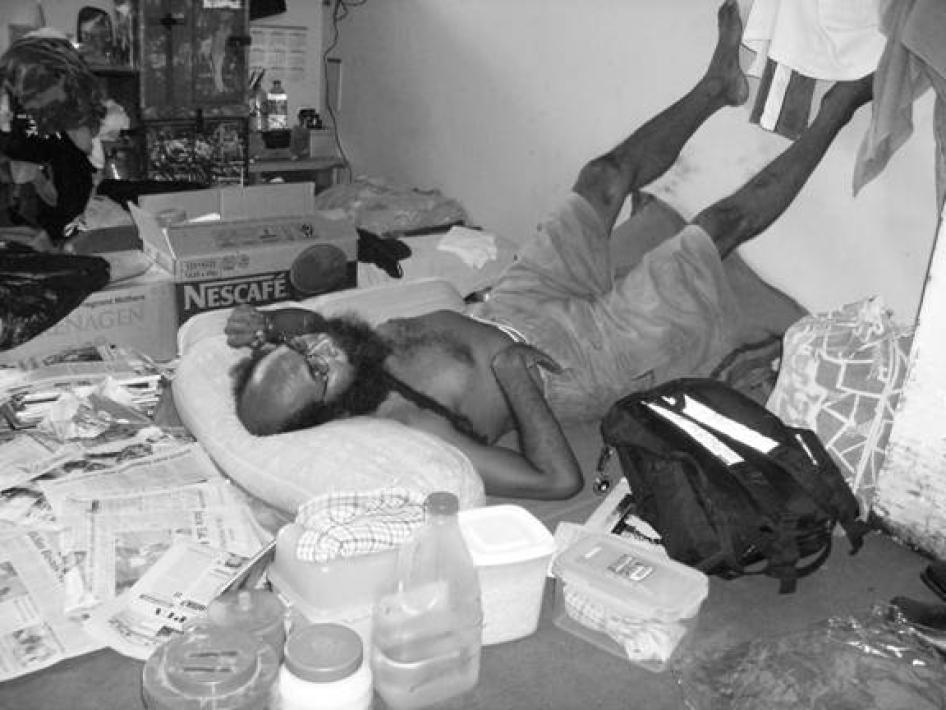

Karma says that authorities have denied him urgently needed medical attention.[36] In August 2009, he told friends that he had difficulties urinating. He requested medical assistance from the staff of Abepura prison in Jayapura, and prison director Anthonius Ayorbaba ordered that Karma be sent to the prison clinic. Clinic staff examined him, and instructed Karma to just drink more water and to take a rest. Finally, through the intervention of media and NGOs, prison personnel were persuaded to send Karma to Dok Dua hospital on August 18, 2009.

Prisoner Filep Karma in prison in Abepura on August 17, 2009, while enduring difficulties urinating. After denying his request to be treated at a hospital, prison officials told him instead to drink water and to rest with his legs elevated. Only after Bintang Papua newspaper published this photo, taken by a reporter, did prison officials agree to allow Karma to go to Dok Dua hospital. ©2009 Bintang Papua/Hendrik Yance Udam

The doctors at Dok Dua hospital examined Karma several times between August and October 2009, and finally recommended Karma immediately be sent for urology surgery, which they said could only be done in Jakarta.[37] Karma made an official request to be sent for surgery in Jakarta. But prison chief Ayorbaba told Karma’s family members that he is not authorized to order such a transfer and added the Indonesian government lacked funds to send Karma for treatment. Aryorbaba told family members to seek permission for the transfer from Nazarudin Bunas, the head of the Ministry of Law and Human Rights in Jayapura. But when they approached Bunas, he told Karma’s family to ask Ayorbaba to write the letter and argued the government had no budget to send Karma to Jakarta.[38]

A group of activists began a campaign on March 8, 2010, asking for public donations to cover medical treatment for Filep Karma and Ferdinand Pakage. The banner reads: “The illness of Filep Karma and other political prisoners is also the illness of the Papuan people … Let’s help and start humanitarian solidarity.”They collected 25 million rupiah (US$25,000) in the first two days of fundraising. ©2010 Garda Papua

Between December 2009 and February 2010, Karma, his family members, and supporters negotiated with Indonesian officials for the medical transfer. In March 2010, an NGO coalition called the Association (“Solidarity”) of Papuan Human Rights Abuse Victims (Solidaritas Korban Pelanggaran Ham Papua, SKPHP) ran a campaign to raise funds for Karma and Pakage that raised enough money to send Karma to Jakarta. But then both the Ministry of Law and Human Rights and Ayorbaba continued to refuse to proceed with the permit.[39] Karma told Human Rights Watch, “I used to be a bureaucrat myself. But I have never experienced such [use of] a red tape on a sick man.”[40]

A student activist holds a donation box to help political prisoners at an intersection in Abepura, March 2010. The Indonesian Ministry of Law and Human Rights refused to send political prisoners for necessary medical treatment on the grounds that it could not cover the costs. ©2010 Garda Papua

In early May 2010, following numerous complaints of human rights abuses at Abepura prison, the government sent a new prison chief, Liberty Sitinjak, to replace Ayorbaba as head of Abepura prison.[41] On May 27, the Ministry of Health sent two Jakarta-based doctors to Abepura to check Karma’s health situation and determined he could have urology surgery in Makassar hospital. At this writing, the surgery has not yet been performed.[42]

Buchtar Tabuni

Buchtar Tabuni, age 31, is a leader of the West Papua National Committee, a pro-independence organization that has grown more radical since his imprisonment.[43]

He was arrested on December 3, 2008, in his house in Sentani, near the Sentani airport, Jayapura, for organizing protests against the shooting of his relative, Opinus Tabuni. He was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment under article 160 of the Criminal Code for inciting hatred against the Indonesian government. Prosecutors also charged Tabuni with treason (articles 106 and 110), but the judges acquitted him on those two charges while sentencing him on the third.

Tabuni was born in 1979 in Papani, a small village 20 kilometers west of Wamena in the Central Highlands region of Papua. Indonesian soldiers killed his uncle in 1977. In 1998, he went to college in Makassar, South Sulawesi, to study engineering.

He became more politically active when a distant relative, Opinus Tabuni, was killed by a stray bullet while taking part in a peaceful rally celebrating United Nations Indigenous People’s Day on August 9, 2008, in Wamena. Many Indonesian police, intelligence, and military officers were monitoring the rally when Opinus was struck and killed.

Buchtar Tabuni helped establish the West Papua National Committee (Komite Nasional Papua Barat, KNPB) in Sentani. On October 16, 2008, KNPB organized rallies in Papua and Java to welcome the establishment of the International Parliamentarians for West Papua in London. On December 1, 2008, KNPB organized a peaceful celebration of Papua’s independence in the cemetery in Sentani where Theys Eluay’s is buried. Knowing about the Indonesian government ban on raising the Morning Star flag, Buchtar Tabuni worked with fellow activists to create many small Morning Star flags, too small to be classified as a “flag” but large enough to wave visibly. Still, two days later, the Indonesian police arrested him and an Indonesian court subsequently sentenced him to three years’ imprisonment.

On February 26, 2009, Abepura prison officials discovered that Tabuni had a mobile phone in his pocket. A prison guard hit Tabuni in his eye, causing it to bleed. Prison guards then temporarily moved Tabuni to the Jayapura police detention center, apparently so that Indonesia’s law and human rights minister, Andi Mattalatta, would not see the wound when making a planned inspection of the prison the next day. After Mattalatta left Papua, guards returned Tabuni to Abepura prison.

On November 26, 2009, three soldiers, one policeman, and one prison guard entered Tabuni’s cell in the Abepura prison. Tabuni told Human Rights Watch that they attacked him without provocation, hitting his head repeatedly, causing him to bleed profusely until other prisoners intervened and stopped the attack. Prison chief Ayorbaba allegedly would not permit him to be treated at a hospital. As news of the attack spread, Tabuni’s supporters in Jayapura believed that the attack was part of a plan to murder Tabuni. So that evening, his supporters surrounded the Abepura prison. They smashed windows, while demanding that the police and military investigate the case and calling for the Ministry of Law and Human Rights to punish prison chief Ayorbaba for permitting the attack to occur.[44] Three TNI soldiers and a policeman were publicly implicated and detained by authorities for involvement in the attack, but the Indonesian government has yet to produce a report on the attack or bring these persons to trial.[45]

On April 6, 2010, the Papuan office of the Indonesian National Commission on Human Rights conducted an unannounced visit to the Abepura prison and recommended the government transfer Ayorbaba without delay. Juolens Ongge of Komnas HAM told the media that there had been more than 20 incidents of human rights violations at the prison since Ayorbaba took over the prison management in August 2008. Ongge confirmed guards beat prisoners frequently and found security in the prisons was poor and that many prisoners had been able to escape.[46] As noted above, Ayorbaba was replaced as prison head in early May 2010.

Ferdinand Pakage

Ferdinand Pakage, worked as a parking attendant in Abepura, near the Cenderawasih University campus prior to his arrest. In 2006, police accused him of stoning and stabbing a police officer to death during an anti-Freeport protest near the Cenderawasih campus. An Abepura court sentenced him to 15 years’ imprisonment under article 214 of the Criminal Code, covering the killing of government officials.

On March 15, 2006, more than 1,000 students had staged a protest demanding the closure of Freeport McMoran’s mining operation in Papua. The students, organized under a group called the Street Parliament (Parlemen Jalanan), blockaded the main street in front of the campus.[47] Approximately 200 anti-riot police tried to end the blockade by firing teargas, beating the protesters, and arresting a protest leader. The students reacted by rioting and throwing stones at the police. Three police officers were brutally killed, beaten to death by protesters. The dead included First Brig. Rahman Arizona, whom Pakage was accused of killing, and an Air Force intelligence officer.

Pakage, his parents, and his sister contend that he did not participate in the riot and thus could not be responsible for the killing. Pakage argues that the testimony of the prosecutors’ two main witnesses against him—Pakage’s close friend Luis Gedi, a shop keeper, and Alia Mustafa Samori, a police officer—was coerced or unreliable.

Police arrested both Gedi and Pakage on the day after the riots, March 16, while walking near the site of the protests.[48] The police allegedly beat Gedi and forced him to declare he was involved in killing Brigadier Rahman. The police also allegedly pressed him to name another suspect, and he ultimately named Pakage.[49]

At trial, the prosecutors brought seven witnesses but only Gedi and Officer Samori testified in person that they had actually seen Pakage stoning the victim. Five other witnesses, all police officers, provided written testimony but claimed they did not see the stoning. Prosecutors also presented as evidence the results of a blood test on a knife taken from Pakage’s house days later and alleged to have been used to kill Rahman. Police claimed the knife had traces of the blood of the victim.[50]

According to Pakage’s defense statement, he was also tortured by more than two dozen police officers at the Jayapura police station. He alleges that officers threw boiling water at him, and beat him until he bled from his head, lips, legs, hands, and body. Pakage wrote that a Jayapura deputy police chief shot him in the right leg on the night of his arrest, March 16, around 11 p.m., after police under the deputy’s supervision could not find a knife in the sewer outside the campus as Pakage had stated under torture. He also alleges that a detective police chief threatened to kill him with a pistol.[51]

On March 21, 2006, the police went to Pakage’s house and seized his mother’s Kiwi 30-centimeter stainless steel kitchen knife as well as his shirt printed with the number “15” and alleged the knife was the murder weapon.[52] The police also said he was seen wearing that shirt during the violence on March 15. Ferdinand’s father, Petrus Pakage, told Human Rights Watch, “It’s all fabricated. I signed the document and handed over the shirt, the kitchen knife. But it was a knife to cut vegetables. His mother always keeps it at home.”

Petrus Pakage added: “If you are shot in your leg, and all the officers are all against you, beating you, like an animal, it is difficult not to bow under pressure.”[53]

Both Gedi and Pakage are currently incarcerated at the Abepura prison, where they both told Human Rights Watch they have again been tortured. Pakage reported that on September 22, 2008, Abepura prison guards took him to the prison security office, where a prison security chief allegedly struck him with a rubber club six times in the head. A guard then hit Pakage with his bare hands, while the security chief repeatedly kicked Pakage with his boot. Another guard allegedly punched Pakage’s head while clenching a lock and key in his hand, and the protruding key penetrated Pakage’s right eye.[54]

Guards allegedly threw the unconscious Pakage into an isolation cell at around 8: 20 a.m. Another political prisoner, Selphius Bobii, heard the noise of the beating and later saw Pakage inside the isolation cell. Bobii demanded prison guards immediately take Pakage to hospital, but guards did not send Pakage to the Abepura hospital until 2 p.m.[55] Pakage says that the hospital was closed and he was not seen by doctors until the next day, September 23, at Dok Dua hospital in Jayapura. By that time, it was too late to save his right eye because the bleeding was too severe.

“My son suffered two times. First, he got a 15-year imprisonment when there’re no witnesses, no evidence. Second, he lost his eye,” said Petrus Pakage.

Abepura prison chief Anthonius Ayorbaba wrote a report on the incident, calling it “an accident” that the guard, Herbert Toam, hit Pakage without realizing that the key was still in the lock. The report also claimed that Pakage had previously threatened a prison guard with a dagger. The report does not mention the role of the other prison guards in the attack.[56]

In December 2008, Ayorbaba told Human Rights Watch that the report on the incident had been submitted to the Ministry of Law and Human Rights as well as the National Commission on Human Rights (Komisi Nasional Hak Asasi Manusia, or Komnas HAM), and added that the guard named in the report would very likely be fired. Ayorbaba said he had advised the guard, Herbert Toam, to take a leave of absence from work and settle the case through traditional means, involving negotiations with Pakage’s clan.[57] Toam did not go to work from October 2008 to March 2009 but continued to draw his monthly salary. The Pakage clan and Toam did not reach any settlement of the case. Toam returned to work at the prison in April 2009 and reportedly continues to work there.[58]

Neither the Ministry of Law and Human Rights nor Komnas HAM appears to have conducted any serious investigation into this matter. In October 2007, Pakage’s family tried to report the case to the Jayapura police, but the police refused to register and file the case. The family orally lodged a complaint with the Ministry which received no response. In October 2007, the Office of Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation, a church-based NGO, wrote to the Ministry of Law and Human Rights office, complaining about various cases of abuse, including Pakage’s case, but received no response to their letter.[59]

Simon Tuturop and Tadeus Weripang

Tadeus Weripang and Simon Tuturop are friends, both born in Fakfak, Papua, in the 1950s. On July 3, 1982, they joined dozens of other Papuans in raising the Morning Star flag in Jayapura, and were both arrested. Weripang was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment and Tuturop to ten years.

Both served two years at Abepura prison and the remainder of their terms at Kalisosok prison in Surabaya. When Weripang was freed in 1987, he went back to Fakfak to work as a farmer. Tuturop, released in 1989, went to Jakarta to help other political prisoners.

After President Suharto was forced to step down in May 1998, Tuturop and Weripang rejoined the Papuan pro-independence movement. Tuturop helped 100 Papuan leaders, representing Papua’s seven traditional areas, to visit Jakarta and to have an audience with President B.J. Habibie in February 2000, where they made a request for Papuan sovereignty. Habibie turned them down.[60]

Today the two are both back in prison, imprisoned for raising the Morning Star flag at the Pepera Building in Fakfak, West Papua province, on July 19, 2008. Pepera stands for “Penentuan Pendapat Rakyat” or the Act of Free Choice, and it was in this building that many Papuans believe Indonesian authorities manipulated the 1969 UN referendum.

Indonesian police arrested 69 people involved in the flag-raising ceremony. Sixty were released and the remaining nine, including Tuturop and Weripang, were tried. Tuturop says he personally was not tortured, but that the police severely beat eight other detainees. “Maybe because I am already 60 years old they have no feeling to torture an old man,” said Tuturop.[61]

A criminal court found Tuturop and Weripang guilty of treason under Criminal Code articles 106 and 110 and sentenced both to two years in prison. After the prosecutor appealed the leniency of the sentence, the Papua High Court increased their sentence to four years.

Roni Ruben Iba

Roni Ruben Iba is a hotel security guard in Manokwari, West Papua province. Police arrested him and about 35 others for raising a pro-independence flag on January 1, 2009, outside the Bintuni Bay district government office. They raised a flag that resembled, but was not the same as, the Morning Star flag.[62]

At their trial, the defendants said they were mistreated during the arrest and at the Bintuni Bay police station. They alleged that the station police kicked them, beat them, and used a rifle butt to strike their heads and bodies.

On November 12, 2009, a Manokwari district court convicted Roni Ruben Iba and two of his clan members, Isak Iba and Piter Iba, for treason under articles 106 and 110 of the Criminal Code. Roni Ruben Iba was sentenced to three years in prison while the other two received two years each. They now are imprisoned in Manokwari prison.

Appendix: Legal Provisions Frequently Used To Prosecute Pro-Independence Activists[63]

Indonesian Criminal Code

Book II.

Crimes.

Chapter I

Crimes against the security of the State.

Article 104.

The attempt undertaken with intent to deprive the President or Vice President of his life or his liberty or to render him unfit to govern, shall be punished by capital punishment or life imprisonment or a maximum imprisonment of twenty years.

(…)

Article 110.

(1) The conspiracy to [commit one] of the crimes described in articles 104-108 shall be punished by a maximum imprisonment of six years. [64]

(2) The same punishment shall apply to the person who with the intent to prepare or facilitate one of the crimes described in articles 104 - 108:

First, tries to induce others to commit the crime, to cause others to

commit or participate in the commission of the crime, to facilitate the crime or to provide opportunity, means or information relating thereto;

Second, tries to provide himself or others with the opportunity, means or information for committing the crime;

Third, has in store objects of which he know that they are designed for committing the crime;

Fourth, makes plans ready or is in possession of plans for the execution of the crime intended to be made known to other person;

Fifth, tries to hinder, to obstruct or to defeat a measure taken by the Government to prevent or to suppress the execution of the crime.

(3) The objects referred to in the foregoing paragraph under 3rd-ly may be forfeited.

(4) Not punishable shall be the person from whom it is evident that his intent is merely aimed at the preparation or facilitation of political changes in the general sense.

(5) If in cases mentioned under section (1) and (2) of this article, the crime really takes place, the punishment may be doubled.

(…)

Chapter V

Crimes against the public order.

(…)

Article 160.

Any person who incites in public [through speech or writing] to commit a punishable act, a violent action against the public authority or any other disobedience, either to a statutory provision or to an official order issued under a statutory provision, shall be punished by a maximum imprisonment of six years or a maximum fine of three hundred Rupiahs.

Government Regulation 77/2007 on Provincial Flag and Logo, Article 6A

The design of a provincial logo and a flag may not be similar in essence with that of a banned organization, association, institution, or separatist movement in the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia. Punishments for violations shall be determined by ministerial decision.[65]

Acknowledgements

This report is based on Human Rights Watch research conducted in Indonesia from December 2008 to May 2010. For security reasons, the researcher cannot be named. Phil Robertson, deputy director of the Asia division; Elaine Pearson, deputy director of the Asia division; and Joseph Saunders, deputy director of the program office at Human Rights Watch, edited the report. James Ross, legal and policy director at Human Rights Watch, provided legal review.

Production assistance was provided by Diana Parker, associate in the Asia division; Grace Choi, publications director; Fitzroy Hepkins, production manager, and Anna Lopriore, photo editor, who assisted with the photo feature.

Human Rights Watch would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of a number of human rights organizations and defense lawyers based in Papua, Ambon, and Java. We wish to thank the Jayapura-based organizations Solidaritas Korban Pelanggaran HAM Papua and Garda Papua, the Merauke-based Sekretariat Keadilan dan Perdamaian, and the Manokwari-based Institute of Research, Analysis and Development for Legal Aid. In Ambon, we extend our appreciation to Tim Advokasi Masyarakat Sipil Maluku (Tamasu). Human Rights Watch also extends our great appreciation to a number of volunteers who assisted our efforts to obtain data and photos from political prisoners inside the prisons. We cannot name them because doing so could endanger them, but we are deeply indebted for their help and acknowledge the personal risks they took in assisting our research.

[1] Human Rights Watch, Turning Critics into Criminals: The Human Rights Consequences of Criminal Defamation Law in Indonesia, May 2010, http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2010/05/04/turning-critics-criminals-0.

[2] “Indonesia: Court Ruling a Setback for Religious Freedom,” Human Rights Watch news release, April 19, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2010/04/19/indonesia-court-ruling-setback-religious-freedom; “Indonesia: Reverse Ban on Ahmadiyah Sect,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 10, 2008, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2008/06/09/indonesia-reverse-ban-ahmadiyah-sect; The Wahid Institute, 2009 Annual Report on Religious Freedom and Religious Life in Indonesia, January 21, 2010, http://www.wahidinstitute.org/files/_docs/EXECUTIVE%20SUMMARY-%20ANNUAL%20REPORT%20RELIGIOUS%20FREEDOM%202009%20WI.pdf (accessed May 28, 2010).

[3] For another recent analysis of the Moluccan cases, see Amnesty International, “Jailed for Waving a Flag: Prisoners of Conscience in Maluku,” AI Index: ASA 21/008/2009, March 26, 2009, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/ASA21/008/2009/en (accessed May 31, 2010).

[4] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), G.A. res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, art. 19.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Johannesburg Principles on National Security, Freedom of Expression, and Access to Information, (Johannesburg Principles), adopted in 1996, E/CN.4/1996/39 (1996)http://www.article19.org/pdfs/standards/joburgprinciples.pdf (accessed May 27, 2010). The Principles were drafted by international law and global rights experts in 1995 and endorsed by the UN special rapporteurs on freedom of expression and on the independence of judges and lawyers.

[7] Human Rights Watch, Breakdown: Four Years of Communal Violence in Central Sulawesi, vol. 14, no. 9, December 2002, http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2002/12/04/breakdown; Human Rights Watch, “Moluccan Islands: Communal Violence in Indonesia,” May 31, 2000, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2000/05/31/moluccan-islands-communal-violence-indonesia.

[8] Reporters and commentators in some Indonesian media outlets called the Christian protagonists in the sectarian conflict “RMS separatists” without noting that some Muslim figures also helped establish the FKM. Republika daily in Jakarta, Ambon Ekspres in Ambon, and Media Dakwah magazine in Jakarta, for example, often used the term “Republik Serani Maluku” which literally means “Moluccas Christian Republic.” In Jakarta, two Moluccan Muslim leaders, Maur Karepessina and Jeki Zakaria, participated in the FKM declaration on Dec. 20, 2000. In Europe, the FKM has a Muslim representative, Umar Santi. In the United States, another Muslim, Hamin Sialana, represents the FKM.

[9] Tamasu’s list of political prisoners is on file with Human Rights Watch.

[10] According to Human Rights Watch interviews with three prisoners who were imprisoned for participation in the June 29, 2007 event, a total of seven dancers managed to escape capture by Indonesian security forces. The remaining dancers were arrested and tried. Twenty-one of 28 cakalele dancers, who are sentenced for the June 29, 2007 incident, are currently placed in seven prisons in Java, Nusa Kambangan, and Ambon islands. Malang prison (4 of 6 RMS prisoners): Johan Teterisa, Leonard Hendriks, Johny Sinay, and Frejohn Saiya. Permisan prison on Nusa Kambangan Island (3 of 6 RMS prisoners): Melkianus Sinay, Piter Saiya, Mersy Riry. Kembang Kuning prison on Nusa Kambangan Island (3 of 6): Ruben Saiya, Yohanis Saiya, Jordan Saiya. Semarang prison (1 of 6): Ferdinand Radjawane. Porong (5 of 7): Freddy Akihary, Pieter Yohanes, Abraham Saiya, Josias Sinay, Marthen Saiya. Ambon prison: Johan Saiya, Buce Nahumury, Charles Riry, Semual Hendriks. Of the seven dancers who escaped arrest, one person is missing and presumed to have drowned in a boat accident while making his escape. Additional information is also contained in Amnesty International, Jailed for Waving a Flag.

[11] President Yudhoyono reportedly told the audience: “If there is an event that disturbs our unity as a nation and as a state, the unity of the Unitarian State of the Republic of Indonesia, in the name of the Constitution, of course, we have to take firm and correct reaction. It’s not negotiable.” His original speech in Indonesian Malay: “Kalau ada acara yang mengganggu keutuhan kita sebagai bangsa dan negara, keutuhan Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia, atas nama Konstitusi tentu kita harus memberikan tindakan yang tegas dan tepat. Ini tidak bisa ditawar-tawar lagi.” Agung Setyahadi, “Tidak Ada Toleransi Bagi Gerakan Separatis: Kelompok RMS Beraksi di Depan Presiden,” Kompas, June 30, 2007; see also Daniel Leonard and Dien Kelilauw, “Melacak Jejak Oknum Intelektual RMS dalam ‘Kekacuan’ Harganas Ambon,” Antara, July 5, 2007, http://www.antara.co.id/print/1183632711 (accessed on March 28, 2010).

[12] Human Rights Watch interview with Johan Teterisa, Malang.

[13] Human Rights Watch interview with Reimond Tuapattinaya, Kediri.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Human Rights Watch interview with Arens Saiya, Semarang.

[16] Human Rights Watch interview with Ruben Saiya, Nusa Kambangan.

[17] Human Rights Watch interview with Leonard Hendriks, Malang.

[18] Human Rights Watch interview with Johny Sinay, Malang.

[19] Human Rights Watch interview with Frejohn Saiya, Malang.

[20] Lilian Budianto, “‘Nonsense’ life sentence for separatist,” The Jakarta Post, April 5, 2008.

[21] Human Rights Watch interview with Johan Teterisa, Malang. Verdict on Johan Teterisa case (Perkara Pidana Putusan No. 318/Pid.B/2007/PN.AB) by the Ambon district court on April 3, 2008, signed by Anton Widyopriyono, Sugiyo Mulyoto, and Kadarisman al Riskandar.

[22] For example, if the family of Teterisa wants to visit him in Malang prison they must do the following. First, they need to take a boat from Haruku Island to Ambon Island. From Ambon, they then need to fly to Makassar and then Surabaya. From Surabaya, it is 90 minutes to Malang by car.

[23] For background on the sectarian conflict, see Gerry van Klinken, “The Maluku Wars: Bringing Society Back In,” Indonesia, vol. 71 (2001); Christopher R. Duncan, “The Other Maluku: Chronologies of Conflict in North Maluku,” Indonesia, vol. 80 (2005); Chris Wilson, “The Ethnic Origins of Religious Conflict in North Maluku Province, Indonesia, 1999-2000,” Indonesia, vol. 79 (2005).

[24] Human Rights Watch interview with Reimond Tuapattinaya, Kediri.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Human Rights Watch interview with Ruben Saiya, Nusa Kambangan.

[27] Human Rights Watch interview with Ferdinand Waas, Ambon.

[28] US President Barack Obama’s stepfather, Lolo Soetoro, was among the Indonesian soldiers sent to invade Papua prior to the 1969 UN-supervised Act of Free Choice. In his book Dreams From My Father, Obama describes how Soetoro was changed—and traumatized—by what he had seen in Papua, including the killing of Papuans. See Andreas Harsono, “Obama Has the Power to Help Papua, the ‘Weak Man’ Under Indonesian Rule,” The Jakarta Globe, February 22, 2010.

[29] “MRP Calling for the Release of Those Classified as Rebels,” http://www.manukoreri.net/west-papua-upheaval-media-briefings-and-background/mrp-calling-for-the-release-of-those-classified-as-rebels/ (accessed May 29, 2010).

[30] Cyntia Warwe, “SKPHP Prihatin Filep Karma dan Tahanan Politik Di Papua,” April 4, 2010, (describing her meeting with Bunas on February 16, 2010), http://www.facebook.com/home.php?ref=home#!/notes/cyntia-warwe/skphp-prihatin-filep-karma-dan-tahanan-politik-di-papua/407736255971 (accessed on April 9, 2010); Human Rights Watch interview with Cyntia Warwe, May 27, 2010. However, as the report was going to press, another official in Papua confidentially told Human Rights Watch that the actual figure of Papuan political prisoners was 39. Human Rights Watch communication with government official (identity withheld), May 31, 2010.

[31] Human Rights Watch interviews with Filep Karma, Jayapura.

[32] See International Crisis Group, “Radicalization and Dialogue in Papua,” Asia Report no. 188, Brussels/Jakarta, March 11, 2010, http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/asia/south-east-asia/indonesia/188-radicalisation-and-dialogue-in-papua.aspx (accessed May 28, 2010).

[33] For a longer account of the incidents in Biak, see Lindsay Murdoch, “Morning Star Massacre,” The Age, November 14, 1998, http://www.blythe.org/nytransfer-subs/98pac/West_Papua_Massacre (accessed May 31, 2010).

[34] Human Rights Watch, Indonesia - Protest and Punishment: Political Prisoners in Papua, February 2007, http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2007/02/20/protest-and-punishment.

[35] Human Rights Watch interview with Filep Karma, Jayapura.

[36] There is a history of Indonesian officials denying medical care to Papuan political prisoners. Tom Wanggai received a 20-year prison term for treason for taking part in a pro-independence flag-raising ceremony on December 14, 1988. In 1995, while in the Cipinang high-security prison in Jakarta, Wanggai began to complain about his health, but was not given timely medical assistance. He died on March 12, 1996 in Kramat Jati police hospital in Jakarta. George J. Aditjondro, “Mengenang Perjuangan Tom Wanggai: Dengan Bendera, atau Apa?” Tabloid Jubi, Jayapura, March 20, 2000. A similar case is that of Hardi Tsugumol, who was charged with providing logistical support to Papuan fighters, was in the Indonesian national police headquarters’ detention center when in June 2006 he developed serious heart problems. His medical treatment was delayed until late August 2006, when he finally was permitted to have heart surgery. His lawyer said he repeatedly asked the Central Jakarta court to attend to Tsugumol’s health problems but only infrequent follow-up visits by a doctor were permitted. Tsugumol died in December 2006. Eben Kirksey and Andreas Harsono, “Criminal Collaborations? Antonius Wamang and the Indonesian Military in Timika,” South East Asia Research, vol. 16, no. 2 (July 2008), pp. 165–197.

[37] In a letter dated October 5, 2009, Dr. Mauritz Okosera and Jhon Sambara, respectively the head of patient transfers and the administration head of Dok Dua Hospital, wrote to PT Asuransi Kesehatan Indonesia, an insurance company, saying that patient Filep Karma should be sent to PGI Cikini Hospital in Jakarta for urology surgery. On November 11, 2009, Dr. Donald Arronggear of Dok Dua hospital detailed the results of Karma’s medical examinations, conducted at the hospital from August to October 2009. Copies of the two letters are on file with Human Rights Watch.

[38] Radio 68H, “Siksa Tahanan Politik di Balik Jeruji Besi,” May 4, 2010, http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=385953959914 (accessed on May 17, 2010).

[39] Human Rights Watch interview with Peneas Lokbere, Jayapura, March 12, 2010. SKPHP asked for public donations to cover Karma’s medical treatment. Their posters read: “The illness of Filep Karma and other political prisoners is also the illness of Papuan people … Let’s help and start humanitarian solidarity.”In Indonesian, the posters read: “Sakit Filep Karma Dan Tahanan Politik Adalah Sakit Rakyat Papua-Rakyat Papua ... Mari Bersolidaritas Untuk Kemanusiaan’’ and “Pemerintah Tidak Peduli Membiayai Pengobatan Tahanan Politik Filep Karma Dan Ferdinand Pakage.’’ SKPHP collected 25 million rupiah (US$25,000) in the first two days of fundraising. Karma raised an additional 75 million rupiah from friends.

[40] Human Rights Watch interview with Filep Karma, Jayapura.

[41] Elaine Pearson (Human Rights Watch), “The Thinker: Papua Behind Bars,” commentary, The Jakarta Globe, May 18, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2010/05/18/thinker-papua-behind-bars.

[42] Human Rights Watch communications with Cyntia Warwe, May 26 and 27, 2010.

[43] With the imprisonment of Tabuni, there have been leadership changes in the West Papua National Committee, and some of the leaders have started to advocate the use of violence. See International Crisis Group, “Radicalization and Dialogue in Papua,” Asia Report no. 188, March 11, 2010, http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/asia/south-east-asia/indonesia/188-radicalisation-and-dialogue-in-papua.aspx (accessed May 28, 2010).

[44] “Lapas Abepura Rusuh Aksi Buchtar Tabuni,” Metro TV, November 27, 2009, http://metrotvnews.com/index.php/metromain/news/2009/11/27/6346/Lapas-Abepura-Rusuh-Aksi-Buchtar-Tabuni (accessed June 2, 2010); “Lemahnya Pengamanan Lapas Abepura,” Tabloid Jubi, November 27, 2009, http://tabloidjubi.com/index.php/index-berita/87-lembar-olah-raga/4434-lemahnya-pengamanan-penjara-abepura (accessed June 2, 2010); “Puluhan Massa Menggeruduk Lapas Abepura,” Vivanews, November 27, 2009, http://nasional.vivanews.com/news/read/109474-puluhan_massa_menggeruduk_lapas_abepura (accessed June 2, 2010).

[45] “Indonesia: Stop Prison Brutality in Papua,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 4, 2009, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2009/06/04/indonesia-stop-prison-brutality-papua; and US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2009: Indonesia,” March 11, 2010, http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2009/eap/135992.htm (accessed May 30, 2010).

[46] Jerry Omona and Angga Haksoro, “Kekerasan di Penjara Komnas HAM Papua: Copot Kepala LP Abepura,” Voice of Human Rights, April 10, 2010.

[47] Human Rights Watch interview with Chosmol Yual, the protest coordinator of the Street Parliament, Doyo Baru prison, Jayapura.

[48] Human Rights Watch interview with Ferdinand Pakage, Jayapura. Detention letter signed by Jayapura Police Adjunct Commissionaire Taufik Pribadi, March 17, 2006, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[49] Human Rights Watch interview with Luis Gedi, Jayapura.

[50] Criminal accusation filed by prosecutors against Ferdinand Pakage (“Tuntutan Pidana Terdakwa Ferdinand Pakage alias Feri”), Kejaksaan Negeri Jayapura, July 12, 2006, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[51] Defense statement of Ferdinand Pakage (“Pembalaan [sic] Terdakwa Ferdinand Pakage alias Feri”), Jayapura, July 26, 2006. His defense lawyers asked the judges to release Pakage on the grounds that the prosecutors had doubted the only witness, police officer Alia Mustafa Samori, who testified that he had seen a Papuan youth with a shirt numbered “15” stoning Arizona Rahman on March 16, 2006. “Nota Pembelaan Penasehat Hukum Terdakwa Ferdinand Pakage,” Jayapura, July 26, 2006.

[52] The items are referred to in a seizure document signed by Jayapura Police Adjunct Commissionaire Syafri Sinaga, dated March 21, 2006.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview with Petrus Pakage, Jayapura, December 4, 2008.

[54] Human Rights Watch interview with Ferdinand Pakage, Jayapura; Human Rights Watch with Luis Gedi, Jayapura.

[55] Human Rights Watch interview with Selphius Bobii, Jayapura.

[56] Antonius Ayorbaba provided a copy of his undated chronology to Human Rights Watch in Jayapura on December 6, 2008, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[57] Human Rights Watch interview with Antonius Ayorbaba, Jayapura, December 6, 2008.

[58] Ayorbaba contended that Pakage had run away from the prison and later tried to rob a meat seller in Abepura. He said that Petrus Pakage, Ferdinand’s father, admitted that Ferdinand had a dagger with him. Petrus also admitted that his son had stayed at home for one month, a practice quite common in the Abepura prison if one bribes a prison official. Human Rights Watch interview with Petrus Pakage, Abepura, December 4, 2008. Rujinem Basuki, the butcher on Gerilyawan Street, Abepura, told Human Rights Watch that she remembered that a young Papuan man matching Pakage’s description tried to sell a goat to her, but it was a normal transaction, and he did not try to rob her or use any dagger, as Ayorbaba had alleged. She questioned why Ayorbaba used her name in his report. Human Rights Watch interview with Rujinem Basuki, Jayapura, December 7, 2008. No charges were ever filed against Pakage for the armed robbery attempt Ayurbaba alleged.