Appeasing China

Restricting the Rights of Tibetans in Nepal

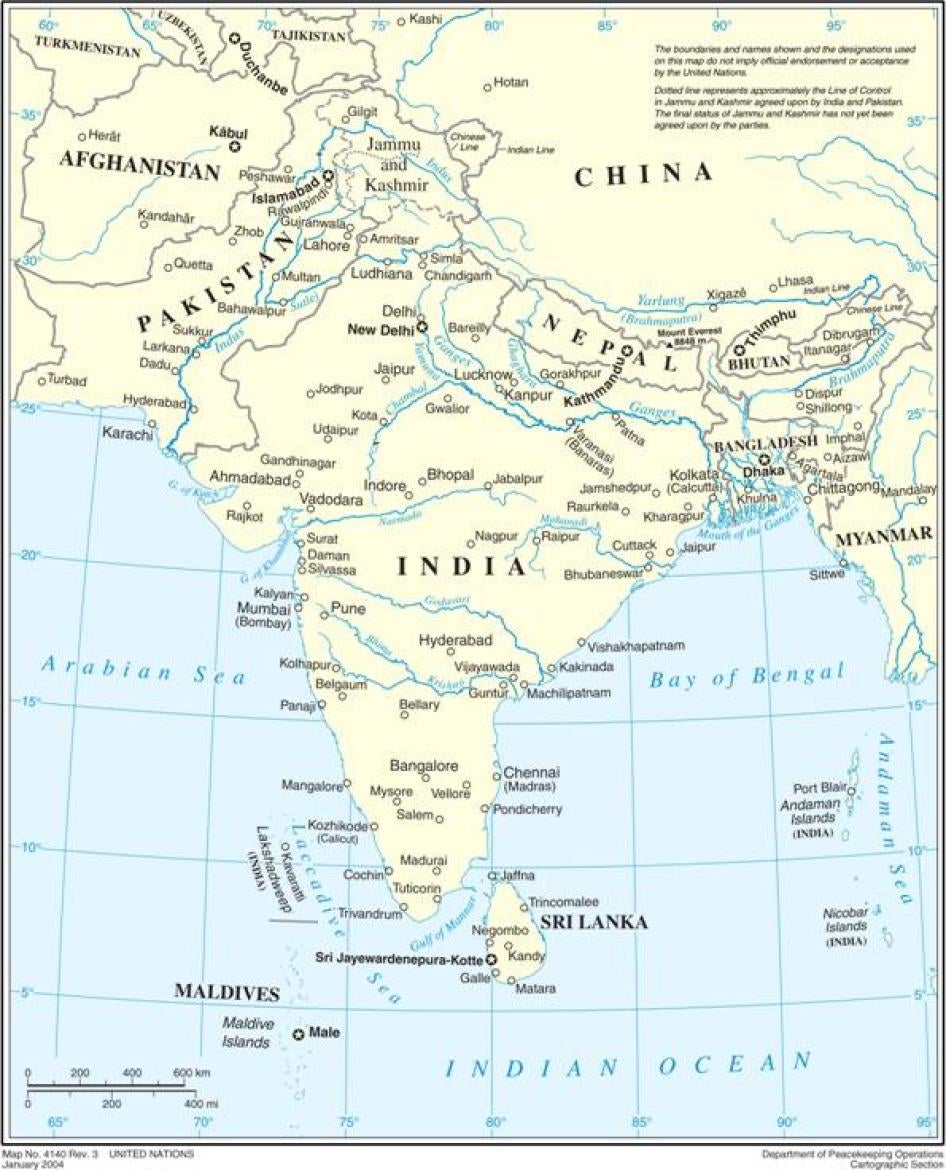

Map of South Asia

Map of the KathmanduValley

©2008 Asian Disaster Preparedness Center, Bangkok, Thailand& National Society for Earthquake Technology,Nepal

I. Summary

We are protesting because we want to tell the truth about our country and we want justice from the UN and human rights. We want to show other countries the real situation in Tibet. This is our aim.

– Nun from Swyambu, Kathmandu, March 29, 2008

I was peacefully protesting when I was hit on the head by police and fell to the ground. I was then hit with lathis [canes] on the feet and legs by three policemen before they ran off and I was helped home by a passerby. Both of my feet are fractured. The doctor told me my left foot will never be the same again.

– 25-year-old Tibetan, Kathmandu, March 19, 2008

We want the Nepali establishment to take severe penal actions against those involved in anti-China activities in Nepal.

– Zheng Xianglin, Chinese ambassador to Nepal, May 12, 2008

On March 10, 2008, some 700 to 1,000 Tibetans living in Kathmandu gathered at Boudha Stupa to mark "Tibetan National Uprising Day," the anniversary of the 1959 Tibetan rebellion against China's rule in Tibet. As the protesters proceeded out of the stupa gate, some young Nepalis pretending to join the protest reportedly started throwing rocks in the direction of the police. Nepali police then moved in and brutally dispersed the demonstrators with lathis, arresting more than 150 people. All those detained were released later the same evening without charge.

As news of continuing protests in Tibet and the Chinese government's harsh crackdown reached Nepal and the world in March, many Tibetans in Nepal felt compelled to speak out. Since March 10, members of Nepal's Tibetan community have frequently carried out peaceful protests (from April 3-15 protests were temporarily suspended to respect the period of Nepal's Constituent Assembly elections). Under slogans of "Free Tibet" and "Save Tibet," Tibetans in Nepal have been calling on the Chinese government to allow Tibetans their rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly; cease excessive use of force against Tibetan protesters; release all Tibetans who have been arrested or detained after participating in protests or for the peaceful exercise of their political views; and allow international media unobstructed access to Tibet. More recently they have called for a United Nations investigation inside Tibet and medical care for those injured in the demonstrations in Tibet.

This report documents violations of human rights by the Nepali authorities, particularly the police, against Tibetans involved in demonstrations in Kathmandu, Nepal. These include unnecessary and excessive use of force, arbitrary arrest, sexual assault of women during arrest, arbitrary and preventive detention, beatings in detention, unlawful threats to deport Tibetans to China, and unnecessary restrictions on freedom of movement in the KathmanduValley. Nepali authorities have also harassed Tibetan and foreign journalists and Nepali, Tibetan, and foreign human rights defenders.

At least 8,350 arrests of Tibetans were made between March 10 and July 18 (many people were arrested more than once). While the frequency of protests has diminished since May, protests have continued to take place on an almost weekly basis, with continuing abuses by Nepali authorities in response. Few of those arrested have been provided with a reason for their detention and virtually all have been released without charge.

Tibetan protesters being arrested by Nepali police near the Chinese Embassy Visa Section on March 31, 2008. © 2008 Private

Human Rights Watch has directly observed many of the Tibetan demonstrations in Kathmandu and the police response to them. From March 10 to 28, Nepali police consistently responded to the demonstrations with unnecessary or excessive force, using lathis to beat protesters in the head and body, and by kicking and punching them. Police officers have sexually assaulted Tibetan women during arrest. Many women and girls have reported male police officers groping them and kicking or hitting them with a lathi in the groin.

Beginning around March 28, perhaps because of media coverage of the authorities' abusive tactics, police officers began using force in less visible ways, such as by having a group of police surround protesters before kicking and punching them in the lower body.

The police have also used unnecessary force to carry out arrests, at times with the apparent intent to disperse crowds of protesters. Threats of violence and sexual intimidation also appear to have been used to deter future demonstrations.

A Tibetan nun cornered and beaten by a Nepali police officer near the UN complex on April 21, 2008. © 2008 Private

The authorities typically detained those arrested for several hours before releasing them in the evening without charge. On two occasions Tibetans were detained overnight: 99 people were held in four locations on April 16, and 68 were held at Ghan II Police Barracks on April 2.

Since March 20, Nepali authorities have also been arresting Tibetans to prevent them from reaching protests and as an apparent means of intimidating and harassing the Tibetan community in Nepal. Tibetans and Nepalis resembling Tibetans, such as monks and nuns, have been arrested in Kathmandu's streets, from taxis and public buses and from tea shops.

Human Rights Watch has documented ill treatment of Tibetan detainees. Police, especially at Boudha Police Station, have severely beaten detainees. Detainees, many of whom suffered injuries while being arrested, have been provided limited-or no-medical care. Dozens of people have been held overnight in places with wholly inadequate facilities.

Nearly all Tibetan protesters interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported being threatened with deportation to China. This threat is being used during arrest and against those in detention with the apparent aim of instilling fear within the Tibetan community or to discourage future protests. The authorities' widespread use of this threat suggests it is Nepali government policy. Returning Tibetan demonstrators to China would violate Nepal's obligations under international law not to send individuals to a place where they are likely to be tortured or, in the case of refugees, face persecution.

The Nepali government has placed severe restrictions on the movement of groups of Tibetans within Kathmandu and in the KathmanduValley, including nuns, monks, and elderly religious practitioners, who regularly move between the three main Tibetans areas (Swyambu, Boudha, and Jawalakel). Police reportedly have put under surveillance individuals perceived to be leaders of the protests and have closely monitored locations of importance to Tibetans in Nepal, such as Jawalakel Tibetan Camp, the TibetanReceptionCenter, Kopan monastery, and a nunnery in Swyambu.

Nepali police have also engaged in physical attacks on and harassment of Tibetan and foreign journalists and intimidation of human rights defenders. On March 24, the authorities arrested members of the nongovernmental organization Amnesty International-Nepal and Nepali human rights defenders prior to a planned demonstration. Human rights monitors and journalists have been photographed and questioned by individuals identifying themselves as Nepali Intelligence.

China has played an important, if at times hidden, role in the Nepali government's crackdown on Tibetan demonstrations. The unusual number of statements from Nepali leaders reiterating the ban on "anti-China" activities suggests increasing pressure from Beijing (see below). Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala on several occasions vowed to prevent demonstrations by Tibetans in Nepal, stating that "no anti-China activity will be allowed on Nepali territory." Nepal's Home Ministry spokesperson was quoted saying, "We have given the Tibetan refugees status and allow them to carry out culture events. However, they do not have the right for political activities.… We will not allow any anti-China activities in Nepal and we will stop it." Soon after the protests began, on March 19, 2008, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) (CPN-M), the largest party in the recently elected constituent assembly, issued a statement expressing solidarity with China and saying, "We want to draw the attention of the concerned [Nepali government] authority to the activities against China at the Nepal-China border."

China has long claimed that the bedrock of its foreign policy is "non-interference" in the internal affairs of other countries. Yet it has directly involved itself in Nepali affairs. China's ambassador has publicly exerted China's influence on the Nepali government through strong and frequent statements, calling for the arrest of protesters and urging the government to take strong action. Senior Nepali government officials, and officials involved in the detention of Tibetans, have cited the relationship between China and Nepal, and Nepal's "one China" policy as the reason for the arrest of Tibetan protesters. With the exception of three Tibetans arrested at their homes under the Public Security Act on June 19, 2008, Nepali law has not been used to justify arrests and those detained have not been charged.

International human rights law guarantees refugees and other non-citizens freedom of assembly and expression, and freedom from mistreatment. While this report focuses on events in Kathmandu from March through April 2008, protests and government crackdowns continue. The rights of Tibetans in Nepal continue to be under assault as peaceful Tibetan protesters are arrested for purely political reasons.

Key recommendations

Human Rights Watch urges the government of Nepal to respect the fundamental rights of Tibetans to engage in peaceful assembly and expression, and to end the arbitrary arrest, harassment, and mistreatment of those who do so. We also call on the Chinese government to stop its public and private pressure on the Nepali government to violate Tibetans' rights.

In particular, we urge the Nepali government to:

·Publicly express support for freedom of expression and assembly for all persons in Nepal, regardless of legal status, and cease dispersing peaceful protests by Tibetans.

·Take all necessary action to end arbitrary arrests, including unlawful and preventive arrests, of Tibetans and others engaged in peaceful political activity or otherwise going about their daily lives.

·Publicly oppose the deportation of any Tibetan to China who faces a risk of persecution or torture there, and take all necessary action, including the issuance of warnings and the imposition of disciplinary action, against Nepali police who threaten Tibetans with deportation.

·Ensure respect for freedom of movement, including by issuing orders to cease restrictions on the freedom of movement of Tibetans in the KathmanduValley.

·Issue orders to all police officers to cease sexual assaults on female protesters. Investigations should be conducted into sexual assaults on protesters that have taken place since March 10, 2008, and the individuals responsible should be prosecuted. Superior officers should also be held responsible for creating an environment in which officers under their command have sexually assaulted female protesters.

·Adopt measures to end interference and harassment of the media and human rights defenders, including by issuing public statements in support of the right of individuals to engage in freedom of expression, association, and assembly. Issue orders to the police to cease harassment of journalists and human rights defenders.

We urge the government of the People's Republic of China to:

·End all forms of pressure, public and private, on the government of Nepal to arrest, prosecute, or otherwise interfere with Tibetans who are exercising their rights under international human rights law. Such pressure is ironic from a state that consistently asserts that "non-interference" in the internal affairs of other states is the bedrock of its foreign policy.

·Cease all police operations in Nepal that are not under the direct control of the Nepali authorities. Ensure that any authorized police activity inside Nepal is in full accordance with Nepali and international law. Remove from Nepal and discipline as appropriate all Chinese security forces acting outside of Nepali authority or law.

·Permit Tibetans in China to exercise their right of freedom of movement to leave and to return to China.

·Cease public statements attempting to intimidate Tibetans as well as Nepali and foreign journalists and human rights defenders in Nepal from exercising their basic human rights.

A full list of recommendations can be found at the end of this report.

Methodology

This report is based on human rights monitoring and interviews conducted between March 10 and April 9, 2008, in Kathmandu, Nepal. This included direct observation of protests and arrests, conditions in detention, and treatment in hospitals; regular observation visits to Tibetan areas of Kathmandu (Jawalakel, Boudha and Swyambu); interviews with more than 90 Tibetan protesters; and interviews with several non-Tibetan protest eyewitnesses, Tibetan community and religious leaders, Nepali medical personnel and police officers, and United Nations personnel in Nepal.

Interviews were conducted in English or in Tibetan through an interpreter. A small number of interviews were conducted on the telephone. All names of Tibetan interviewees have been changed, usually at the request of the interviewee, for security reasons.

II. Background

In recent decades, a steady stream of Tibetan asylum seekers has crossed the Himalayan mountain range to escape political, religious, and cultural persecution and seek refuge in Nepal. Kathmandu has also been used as a transit point for asylum seekers on their way to Dharamsala, India, which has a large Tibetan presence. In the last 10 years, the Tibetan community in Nepal has been stable at around 20,000 people.[1]

Many Tibetans who arrived in Nepal before January 1, 1990–about 14,000 individuals–are regarded as refugees by the government of Nepal, which normalizes their residence in Nepal with so-called Refugee Cards (RC). Those who arrived after January 1, 1990, are officially regarded as persons "in transit" because the Nepali government stopped issuing Refugee Cards to those arriving after that date. Many new arrivals from Tibet go through Nepal to reach India, though not all Tibetans are "in transit." Nepal has not ratified the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, which regulates the treatment of refugees under international law.[2]

Tibetans in Nepal face discrimination and uncertainty due to their tenuous legal status, and face restrictions on state-provided education, health care, and employment. Their freedom of movement is restricted by requirements that they register with the chief district officer (CDO)[3] when they change residence and when traveling outside the district in which they are registered. Tibetans with a Refugee Card cannot travel outside of Nepal unless they obtain an exit permit from the government of Nepal, which is valid for one trip per year to only one destination.[4]

Tibetans in Nepal also fear being deported without being afforded basic due process rights. These include the right to seek political asylum when they have a well-founded fear of persecution and the right not to be sent to a country where they are likely to be tortured. For instance, in May 2003 Nepal deported 18 Tibetans to China without regard for due process on charges of travelling without valid documents.[5] The arbitrary nature of the deportation created fear within the Tibetan community. In late February 2008, China issued an Interpol request for a Tibetan man who had recently arrived in Nepal. The Nepali authorities arrested him at the TibetanReceptionCenter and returned him to China without permitting him to contest his deportation before a competent authority. His arrest at the TibetanReceptionCenter, the center responsible for processing Tibetans in transit from Tibet to India, long regarded as a safe haven, caused deep fear within the Tibetan community.[6]

Successive Nepali governments have consistently stated that "anti-China" activities would not be allowed on Nepali soil. China is an important economic and political neighbor for Nepal. At times this strategic relationship has deepened, such as during former King Gyanendra's rule from February 2005 to April 2006. Immediately preceding King Gyanendra's assumption of direct control of Nepal on February 1, 2005, the Nepali government closed the Office of the Representative of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The following day the Chinese government was reported in China's People's Daily as welcoming the closure.[7] While there was global condemnation of then King Gyanendra's seizure of power on February 1, 2005, China stated that it was an internal matter for Nepal.[8]

In 2007, Nepal's then-ruling all-party government, known as the Seven Party Alliance, which was broadly accepted as a democratic government, took the unprecedented step of deregistering the Bhota Welfare Office, a local organization assisting Tibetans living in Nepal. The organization had been registered by the Kathmandu CDO in 2007 after agreeing to delete the word "Tibetan" from the name of the organization. The organization challenged its deregistration in the Supreme Court of Nepal. During the final hearing on the case in February 2008, the government attorney handed a confidential file to the judicial panel, which denied the organization's lawyers access to the documents. The Supreme Court then issued an oral judgment that the organization could not be re-registered.[9] This deregistration means the organization is effectively no longer allowed to operate in Nepal, which has serious consequences for the welfare of Tibetans in Nepal. It also raises broader concerns for freedom of association in the country.

Tibetans face considerable hurdles when they seek redress for abuses by the Nepali security forces. Human Rights Watch has continually raised concerns about the impunity enjoyed by security forces for even serious human rights violations, especially during the decade-long civil war, which ended in 2006.[10] The army in particular has a well documented history of torture, extrajudicial killings, and enforced disappearances. The failure by various governments of Nepal to address past human rights violations has helped to create an environment in which violations by the security forces of Nepal continue to occur. The current abuses of Tibetan protesters should be viewed as part of this broader failure to address the culture of impunity in Nepal.

III. Violations of the Right to Peaceful Assembly

Unnecessary and excessive use of force

In the weeks following the start of Tibetan protests in Kathmandu on March 10, 2008, Human Rights Watch observed 18 demonstrations. In all 18 demonstrations, Nepali police used unnecessary or excessive force against protesters. Police used unlawful force during arrests and in attempting to disperse demonstrations. In nearly all of the protests, Tibetans demonstrated peacefully; we are aware of only one case in which protesters reportedly used violence, a March 10 protest in which Nepali youth, who appear to have been fake protestors, threw rocks at police.

The Nepali authorities have not provided a legal basis for breaking up the demonstrations and arresting participants. Nepali law does provide regulations on public gatherings. Under the Local Administration Act, 1971, the chief district officer (CDO) has primary authority for the maintenance of peace and security at the district level.[11] While Nepali law does not require a permit from the government to engage in peaceful assembly, the Local Administration Act allows the chief district officer to prohibit gatherings in specified areas. These are areas declared to be riot affected areas[12] and specified public roads where "obstruction" is prohibited.[13] However the chief district officer has not declared any areas to be riot affected, and no Tibetan protests have taken place in the three existing specified public roads.[14]

The Local Administration Act also allows the chief district officer to "issue an order for not allowing the gathering of more than five persons at the same place with the purpose of hooliganism or turmoil in such area and time."[15] Such an order appears applicable only to specified individuals gathering at that time and area,[16] and no such order is known to have been issued to any Tibetan protester.

International law protects the right of peaceful assembly.[17] Restrictions for reasons of national security or public order may be imposed, but only when in conformity with the law, where they serve a permissible purpose, and are necessary and proportionately applied.[18] Non-nationals lawfully in a country are entitled to the same rights of assembly as nationals.[19]

Even if the police actions against the demonstrators were a warranted infringement on the right to peaceful assembly, the authorities have used unnecessary and excessive force against protesters. International human rights law places restraints on the use of force by police and other security forces. According to the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, police should use force only when unavoidable and, even then, should exercise restraint and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offense and the legitimate objective to be achieved. The force used must minimize damage and injury.[20] The unlawful use of force by police can amount to violations of the prohibition against cruel or inhuman treatment.[21]

In our observations of police use of force in response to demonstrations by Tibetans after March 10, we found that Nepali police used unnecessary force against peaceful demonstrators and excessive force against demonstrators resisting arrest. Every one of the more than 90 Tibetan demonstrators interviewed by Human Rights Watch had either been beaten during a protest or had observed friends being beaten.

The manner in which police used force appeared to change over time. Initially law enforcement authorities aimed to focus on dispersing the crowds and openly used brutal force, such as beatings to the head and body with lathis (wooden canes of approximately 1.5 meters used by police throughout South Asia for crowd control), and kicking and punching. As reports of this ill-treatment began to surface in the media the authorities appeared to change tactics. Beginning in late March, protesters reported that police had begun to hit them on lower parts of the body with lathis; to encircle and kick individual protesters; to target punches to the kidneys; to hold protesters by the neck, cutting off air; and to pinch, scratch, and pull the protesters' hair.

Dispersing crowds

In the first week or so of protests, crowd dispersal was more common than mass arrests.[22] Small numbers of people were arrested, but large numbers were dispersed using unnecessary and sometimes excessive force. During this period, the police would first ask the crowd to disperse before using force; this practice seemed to stop as the demonstrations continued.

Following are some specific incidents from the first week of demonstrations.

March 10

Between 700 and 1,000 Tibetans gathered at Boudha Stupa on the morning of March 10 to carry out their annual peaceful protest to commemorate March 10, 1959. As the procession left the gate of Boudha Stupa and began to move west along Boudha Road towards Kathmandu, Nepal Police moved in and within a few minutes prevented the procession from proceeding further. Tibetan protesters report that they then witnessed Nepali youth pretending to join the protest throwing stones in the direction of police, which swiftly led to a police lathi charge. Nima Tsering, age 61, reported being beaten on March 10:

On March 10, when I was going along the road, my aim was human rights, not to disturb Nepal or China. When I reached Pasang Lama Chowk I was beaten with a stick on my legs and back and was unconscious for 15 minutes.[23]

A nun from Swyambu told Human Rights Watch about what happened to nuns on March 10:

Some [policemen] hit the nuns, not only nuns but many Tibetan people. They were hit very bad and they got wounded. Around 15 nuns were hit on the back and now they are black and still they hurt. We asked them to check with the doctor but they said, 'It's ok, we did the protest for our country.'[24]

Tashi Tsomo, age 49, reported that police pushed her with such force that she fainted.[25] Others have reported seeing Tibetans beaten with sticks and kicked. One man was beaten so hard on his head that he was taken to hospital by his friends.

The force used on March 10 appears to have been focused on dispersing the protesters, and both those arrested and those who fled the location of the protest reported the use of force against them.

March 14

On the evening of March 14, police used unnecessary force against 70 to 80 peaceful protesters, three of whom were arrested. The group was standing just outside Boudha Stupa Gate between 6:30 and 7:00 p.m. when approximately 50 Nepal Police and Armed Police charged them with lathis. As the protesters attempted to run away, police chased them and hit them with lathis, shouting, "We have to hit them!"[26]

Nima Phuntsok, age 25, was seriously injured on this occasion:

I was hit on the head by police and fell to the ground. I was then hit with lathis on the feet and legs by three policemen before they ran off and I was helped home by a passerby.[27]

Nima Phuntsok had fractures in both feet and learned that his left foot is so badly injured that it will never fully recover.[28] He has not reported his torture to the police or filed a claim under the Torture Compensation Act, as he fears retaliation by the police.

March 15

On March 15, police broke up a peaceful gathering of more than 100 protesters in front of UN House in Pulchowk and arrested 12. The protesters had asked the Nepal Police to allow them to protest for 10 or 15 minutes, but the police stated that they had received orders from senior authorities and immediately charged the group. The police focused their attention on a small group of hunger strikers sitting quietly off to one side. After this group was arrested, Human Rights Watch observed the police disperse the remaining protesters by charging them and beating them with their lathis.

March 17

On March 17, a large group of Tibetans began a peaceful protest around 10:30 a.m. After approximately one hour, the police began beating and arresting the protesters. The police then allowed the remaining protesters to demonstrate in front of the UN House sign on Pulchowk Road for about an hour. The police then surrounded the protesters and fired tear gas into the crowd, particularly targeting a group of 11 hunger strikers. The crowd immediately dispersed, and those who fled in a northerly direction were chased by the Lalitpur district police until they crossed BagmatiBridge (approximately two kilometers), where Kathmandu district police took over the chase.[29]

Police assaults against protesters

Individual participants in the demonstrations gave detailed accounts of their treatment by police.

Tenzin Wangpo, age 23, told Human Rights Watch that he has joined most of the protests since March 10, and on every occasion has been assaulted by the police. He said that police hit him with lathis; kicked, pinched, and scratched him; pulled his hair; and hit him on the back of the knees with a lathi, forcing him to the ground. He alleges that police on two occasions kicked him in the kidneys. He said he was hit twice on the head with a lathi and once in the mouth. He said that on more than one occasion he was pushed onto the ground near a police van while as many as five police officers stepped on his stomach and chest and another six or seven surrounded him to block the view of the media. He said he was also verbally abused by the police.[30]

Dukar Gyal, age 30, reported that the police kicked and hit him with sticks on the back and shoulder before they arrested him on March 10.[31] Dawa Tsering, age 25, said he was severely beaten, including on the head, before being arrested and taken to Kamal Pokhari Police Station on March 10.[32] Tenzin Gyaltsen, age 27, alleged being hit with a lathi by the police on March 10.[33] Tsering Pinchok, age 36, has reported being kicked in the stomach on March 15.[34] Nima Tsering, age 61, said police hit him on the head on several occasions.[35] All said they had been peacefully protesting when the police assaulted them.

Sherab Dolma, age 22, reported seeing police beat protesters on the legs, back, and buttocks on March 24. Disturbed by seeing a police officer beat and push a woman to the ground, she got out of the microvan in which she was traveling and joined the protest, only to be arrested herself.[36]

After March 28, the police appeared to change their tactics against individual demonstrators. In place of lathi attacks to the head and upper body, there were significant increases in reports of police beatings on lower body parts with lathis, punches and kicks to the kidneys, and pinching, scratching, and hair pulling. Namcho Rimpoche, age 29, told Human Rights Watch that on March 30,

I was lying on the ground and many police officers made a circle around me, and the police started hitting me and kicking me down low. They punched and kicked me in the kidneys and upper ribs. They also pinched me.[37]

On March 29, following arrests of peaceful protesters outside the Chinese Embassy Visa Section, Human Rights Watch observed bruises and bleeding scratch marks on men and women detained at Ghan II Police Barracks. These included major bruising on a nun's leg resulting from being beaten with a lathi, and a monk with bleeding and loose teeth after a police officer punched him in the face.

Tashi Dolma, a 25-year-old woman, told Human Rights Watch,

On March 31, I was protesting at the Chinese Consulate and I was kicked in the back of my ribs while they arrested me. Then in the police jeep I was held strongly by the neck.

Tashi Dolma, who has epilepsy, reported that this treatment resulted in her having an epileptic fit while in detention. She also reports that on a separate occasion three female police officers held her while a male police officer hit her with a lathi. She also said that police officers had kicked her in the groin, the back, and the buttocks.[38]

On March 31, Samphel, age 24, a Nepali monk, was beaten on his kidneys by three police officers while a fourth police officer held him tightly by the neck.[39] Penpa Dolma, age 15, reported seeing police beat a group of young men using punches to the kidney area on April 2.[40]

Police have beaten a number of protesters so badly that they required medical attention while in detention. On March 17, Tenzin Dolkar, age 39, and Nwang Tenzin, age 25, were both taken to the police hospital for treatment. Tenzin Dolkar's arms were X-rayed, as they had been beaten with lathis when she tried to protect her head.[41] Nwang Tenzin had similar injuries on his arms, and had also fallen to the ground and been beaten on the back of his ribs with a lathi. He told Human Rights Watch,

The police took my friend, so I tried to hold onto him. Then the police tried to hit me with a lathi, so I put my arms up and now I have a damaged arm. Then I fell to the ground and the police beat me while I was on the ground, and now I have this large bruise on my back. My friend picked me up because I couldn't walk and then the police put me into the van.[42]

On March 24, a Tibetan welfare officer reported being called to Jawalakel Police Station because two monks had been badly beaten on the head and required medical attention.[43] On March 25, Thupten Tashi, age 26, and Nawang Chogyang, age 25, were X-rayed for injuries to the head and ribs, respectively, and Nawang Rabjor, age 38, was treated for soft tissue damage. All three were unable to walk unaided. Dichen Dolkar, age 18, had her shoulder X-rayed and was given injections in both hips to reduce pain on March 30.[44]

Protesters attempting to protect others being beaten have also been beaten and arrested by the police. Lobsang Jinpa, age 26, was arrested after he asked the police to stop beating a monk on March 20.[45] Tenzin Jinpa, age 37, saw a group of women being beaten with lathis on March 15, so he put his arms around the women, and was subjected to a harsh beating to his exposed back. On March 24 he saw five police officers beating his friend on the back and legs with a lathi, so he tried to intervene and three police officers kicked him two or three times on his back, slapped his face, and then beat his hip.[46] Police also beat two foreign journalists who questioned police officers during protests about the use of force against peaceful Tibetan protesters.

Nepal Police and the Armed Police have also caused physical harm to Tibetan protesters following their arrest during transfer in vans, trucks, and jeeps to places of detention. This physical abuse appears to be intentional. The observed shift from visible assaults to less visible abuses was accompanied by increased reports of beatings inside police vehicles, more frequent use of vehicles without windows (such as large Armed Police Force trucks), and police vans with closed tinted windows.

On one occasion Human Rights Watch observed Nepal police holding a protester by the neck while another police officer hit him inside a police van. Namcho Rimpoche, age 29, reported seeing two women hit in the back of a truck after protesting at the Chinese Embassy Visa Section on March 27.[47] Tashi Tsomo, age 49, reported that while being transferred from the protest on March 31 police officers held her on the floor of a police truck while four or five male police officers walked on her body. She said,

A friend tried to help me get up but the police just kept doing it. I still have pain in here [pointing at her chest]. There were no women police in the truck with us, even though most of us in the truck were women.[48]

On numerous occasions, particularly after March 28, Human Rights Watch received reports of police trucks being driven recklessly with the apparent intention of throwing about passengers in the back of the truck and causing them injury. On one occasion a protester had to be taken to the hospital after reaching Ghan II police barracks.[49]

Attacks on journalists

Nepali police have physically attacked and harassed journalists and sought to intimidate human rights defenders monitoring abuses against the Tibetan community in Nepal.

Nepali police physically assaulted journalists on at least two occasions. On March 17, a foreign journalist who was attempting to photograph arrests of protesters was punched in the face by a Nepali police officer outside the UN complex.[50] On April 17, Human Rights Watch observed a police officer manhandle, kick, and punch a foreign journalist.

On April 18, two Tibetan journalists covering a protest were arrested. Police specifically targeted Tenzin Choephel and Thupten Shastri[51] out of a group of five Tibetan journalists a few minutes after the protest had finished. When Choephel and Shastri asked the reason for their arrest, a senior officer replied, "I don't know the reason, but it might be because if there are many Tibetan journalists, then there are more Tibetan protesters coming."

Foreign and Tibetan journalists and human rights workers observing protests have been photographed at close range (one meter) by what appear to be Nepal intelligence officials and also questioned.

Sexual assault of women during arrest

Nepali police have repeatedly sexually assaulted Tibetan women during arrest. Women, including girls under 18 years of age, reported male police officers groping their breasts and buttocks inside and outside their clothing. Some said they had been struck in the groin with a lathi. Sexual assault is never a legitimate law enforcement method. The numerous, strikingly similar cases reported, and the failure of the authorities to denounce such actions, let alone investigate those responsible, strongly suggest that sexual abuse of Tibetans by the Nepali police is systemic and tolerated.

Tashi Topgyal, age 17, said she was arrested at both UN House and at the Chinese Embassy. She told Human Rights Watch that policemen touched her breasts and buttocks outside her clothes and also tried to touch her breasts inside her clothes. She said she could not identify the police officers who assaulted her because two or three men were all restraining her and touching her while they arrested her and put her into the police van. When she asked the police why they were touching her, they laughed at her.[52] Tashi Dolma, age 25, reported that on several occasions the police touched her on the breasts and buttocks while they put her into a police van.[53] Dawa Tsering, age 25, said that a police officer groped her while she was not fully conscious after she had fainted at a protest.[54] She also reports being groped during arrest on several other occasions.

Nima Tsering, age 38, said that she had her breast squeezed so forcefully by the police that she could not breathe properly. She said it was difficult to know which policeman did it, as there were so many policemen touching her through her clothes.[55] Pelkyi, age 35, reported having her breasts groped.[56] Tenzin Jinpa, age 37, said that a group of girls who protested with him on March 15 at the UN House told him that the police touched their breasts.[57] Tsering Tsomo, age 30, reported that on March 24 a policeman tried to hold her breast, so she screamed; the following day another police officer tried to hold her breasts. Tashi Tsomo, age 48, said that policemen tried to grab her breasts on March 24 when she was protesting at the Maitighar Mandala. At a protest on March 24 at UN House, an 18-year-old woman reported that the police touched her breasts and groped her groin area and tried to tear her clothes. She also reported that on March 28, seven or eight policemen attempted to sexually assault her while arresting her, and when she resisted they verbally abused her and her friends with sexually harassing language.[58]

On March 29, following a demonstration at the Chinese Embassy Visa Section, Tibetan women told Human Rights Watch that policemen had been trying to put their hands inside women's trousers and touch them. Similar behavior was also reported following a protest at UN House on March 21.

Several women also reported being kicked or hit in the groin with a lathi, in some cases resulting in urinary tract injuries. Tashi Dolma, age 25, was kicked in the groin on March 24 while protesting at UN House.[59] Nima Sangmo reported being kicked in the groin on March 25.[60] Tsering Tsomo's friend was kicked in the groin on March 24.[61]

IV. Arbitrary Arrest and Detention

At least 8,350 arrests of Tibetans were made between March 10 and July 18 (many people were arrested more than once).[62] Arrests have continued since. While the frequency of protests has diminished since May, protests have continued to take place on an almost weekly basis, with continuing abuses by Nepali authorities in response. Few of those arrested have been provided with a reason for their detention and virtually all have been released without charge.

Typically, those arrested were detained for several hours and then released without charge in the evening between 7 and 10 p.m. On two occasions in April the authorities held large groups of Tibetans overnight: 68 were held at Ghan II Police Barracks on April 2, and 99 people were held in four locations on April 16.

International human rights law prohibits arrests and detentions that are arbitrary. An arrest or detention is arbitrary when not carried out in accordance with the law, or if the law allows for the arrest and detention of people for peacefully exercising their basic rights such as freedom of expression, association, and assembly.[63] Nepali police arrests of Tibetan demonstrators have either been without regard to Nepali law or violated fundamental freedoms, or both.

Senior government officials and officials questioned by Human Rights Watch at places of detention and in interviews with the media often cited the relationship between China and Nepal as the reason for the arrest of Tibetan protesters. On March 17, the district superintendent of police (DSP) informed Human Rights Watch that the Tibetans detained at Jawalakel Police Station at the time were detained because of the Nepali government's policy regarding China. On March 20, the International Herald Tribune quoted Nepal's Home Ministry spokesperson saying, "We have given the Tibetan refugees status and allow them to carry out culture events. However, they do not have the right for political activities.… We will not allow any anti-China activities in Nepal and we will stop it."

Lower-level police officers have regularly stated they are "just following orders" or have given other reasons for arrest when questioned by Human Rights Watch. An assistant subinspector (ASI) on duty at Ghan II police barracks told Human Rights Watch that his barracks was being used to detain Tibetan protesters because he had been told that "they are dangerous and trying to create trouble for the UN, and these type of people must be kept here." Another ASI at Ghan II, on a separate occasion, said that protesters had violated Nepali law by protesting in a restricted area.

Tibetans told Human Rights Watch that when they asked police why they were being arrested, officers frequently said that they were simply following orders or did not know the reason. Sherab Dolma was once told she was being arrested "because she was Tibetan."[64]

Under Nepali law, persons arrested must be produced before the adjudicating authority (usually the court or the CDO) within 24 hours of the detention. They must either be charged with a crime or released.[65]On only one occasion during the first round of protests between March 10 and April 3 were any detained Tibetan protesters given charge sheets.[66] The charges were dropped before being brought before a judge.

During two peaceful protests that took place on the afternoon of April 2 outside the Chinese Embassy Visa Section, the police arrested 56 individuals during the first protest at , and then an additional 17 individuals, including four children, during the second protest at around 4:30 p.m. Five of those arrested in the second protest were taken to Kamal Pokhari Police Station, while the other 12 were taken to the Ghan II Police Barracks, where the first group of protesters was being detained. The detainees at Kamal Pokhari Police Station were released around the same evening.

The authorities made no real effort to charge any of those arrested with criminal offenses. At 9:30 p.m. they informed the 12 protesters from the second protest detained at Ghan II Police Barracks that they were responsible for breaking a small plastic window in the police van in which they had been transported. They were told that they would be kept overnight for further investigation, but they were not formally charged. The other 56 Tibetan protesters detained at Ghan II Police Barracks refused to leave without them, and as a result, all 68 Tibetans spent the night at Ghan II Police Barracks. The detainees sought legal counsel after being informed they would be held overnight. A lawyer who came to the gate of Ghan II Police Barracks was denied entry.

The following morning, April 3, six of the 12 protesters detained in the second protest were given charge sheets stating they were detained "for investigation," but not accused of a crime. They were then moved to Kamal Pokhari Police Station. The remaining 62 detainees, including six from the second protest, were given blank arrest warrants and later released. The six given charge sheets were also released that day, but only after negotiations during which Tibetan community leaders agreed to suspend protests until after Nepal's Constituent Assembly election, scheduled to take place on April 10. In effect, the Tibetans' release was won by giving up for a time their right to freely assemble.

The arrests appear to have been in part a response to pressure from the Chinese authorities to end the demonstrations outside the Chinese embassy. Human Rights Watch was informed by an ASI at Ghan II Police Barracks that on April 1, the day before the arrests, the police had been called out to investigate alleged damage to the Chinese Embassy gate by the Tibetan protesters. No damage was found. And on April 2, the Chinese ambassador to Nepal convened a press conference in Kathmandu during which he urged the government of Nepal to "take severer measures to prevent these political organizations from organizing and implementing illegal political activities."[67] As noted below, there is also evidence that a senior Chinese embassy official was pressuring the government to use the Offences against the State Act to charge some Tibetan protesters.

Preventive arrest and detention

Starting shortly after the initial protests on March 10, Nepali police began arresting Tibetans and Nepalis who appear Tibetan, such as monks, in the streets, in taxis and public buses, and in tea shops, apparently to prevent them from reaching protests and as a means of intimidating and harassing the community.

On March 20, the Nepal police began to arrest Tibetans as they moved in and around areas in which protests had taken place. Lobsang Jinpa, age 26, told Human Rights Watch that as he was walking towards UN House in Pulchowk, two police vans suddenly appeared, and he saw police arrest two monks who had been walking down the street. He said that when the monks refused to get into the vans, the police officers beat them on the back with lathis. When he asked the police to stop beating the monks, he himself was arrested. He was released without charge that evening.

Following this incident, police searched for Tibetans for about an hour in and around UN House. Human Rights Watch observed two nuns being arrested as they walked away from the area. Human Rights Watch also observed police arrest a Tibetan at a tea shop near UN House and saw around 10 Tibetans surrender themselves for arrest outside the same tea shop. By the end of the day, at least 99 Tibetans were in detention. They were all released without charge.

On March 24, the Nepal police carried out many preventive arrests. Lobsang Jinpa reported seeing monks and women in Tibetan dress being arrested in Boudha. He also saw taxis and microvans being stopped in front of Boudha Police Station, and saw at least one monk being taken out of a microvan and into the police station.[68] Throughout the day, 70 Tibetans had been apparently preventively detained at Boudha Police Station. They were all released the same day.

The same day, March 24, arrangements had been made for two buses to transport Tibetans to an Amnesty International-Nepal protest at Maitighar Mandala, in Kathmandu. The buses took different routes to avoid being stopped by the police, but arrived at the Mandala around the same time. The individuals from one bus were able to join the peaceful protest, but only half of the individuals on the second bus were able to get off before four police officers entered the bus and drove it directly to a place of detention. Those detained were held for the remainder of the day and released without charge.[69] Dhondup Gyasto said, "They let me down early because I am an old man but all the others on the bus were taken to the Mahendra Police Club."[70]

On other occasions, the authorities picked up individuals at protest sites even before they began any kind of protest, and seemingly arrested individuals at random from Tibetan areas.[71]

Tenzin Jamphel, age 38, a Tibetan monk from Swyambu who has been arrested on 21 occasions for protesting, was active in organizing candle vigils at Swyambu on March 15-17 and the protest at Boudha on March 10. On March 18 at 9:00 a.m., plainclothes police officers from Swyambu Police Ward 15 came to his monastery, handcuffed him, and took him to Ward 15 Police Station. He was kept there for around four hours and asked by the inspector, "Who sent you? Why are you doing that [demonstrating]?" He was also told that the inspector had the power to release or continue to detain him, and that the inspector had been threatened with loss of his job if he didn't arrest him. The inspector then said that Tenzin Jamphel would be taken to Naxal Police Headquarters to sign a document. The inspector said he would ensure he was not detained.

At Naxal Police Headquarters, Tenzin Jamphel was questioned by a Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) for around 15 to 20 minutes. The SSP asked him, "Who is telling you to do this? What organization are you affiliated with? Is the Tibetan exile government telling you to do this?" He was then transferred in a police jeep with a gun pointed at him to the Kathmandu chief district officer's Office. Tenzin Jamphel recalls the chief district officer saying to him:

Do you know why you have been given RC [Refugee Card]? When you are living in Nepal you should follow the laws of Nepal. As a refugee you cannot demonstrate in Nepal. If you want to protest we can send you back to Tibet. This is the last warning we are giving you. You are on the list of the wanted people. If you take part in any demonstrations in the future and you are brought here we will take back your RC and send you back to Tibet. You have a long record of demonstrations in Nepal – your name has been registered at different police stations in the past.

Tenzin Jamphel was accompanied by a Nepali monk who was his friend. This Nepali monk was asked: "You are Nepali. Why are you getting involved in a Tibetan political movement? Do you know what problems we are facing in Nepal? We have so many problems. Why are you a monk?"

Tenzin Jamphel and his Nepali friend were then told they must sign a document. When they refused they were informed, "If you do not sign then you cannot leave here." They then signed the document, which read, "We willingly agree to sign this paper and agree to abide by following conditions: From this date in the whole of Nepal we will not do anything to disrupt peaceful security, and it is our responsibility to not do any illegal activities." The chief district officer then told his secretary to add the document to Tenzin Jamphel's file and to add his name to the "list." After the Nepali friend left the room, the chief district officer said that there would be four copies of the signed document: one for the Naxal Police Headquarters, one for the Chinese Embassy, one for the District Office, and one for the Home Ministry, and that if Tenzin Jamphel told anyone this he would be arrested.

Over the next two months, Ward 15 police officers continued to visit Tenzin Jamphel and ask about his activities and the activities of the Tibetan community in Swyambu.

The Interim Constitution of Nepal only allows preventive detention if there is evidence of "an immediate threat to the sovereignty and integrity or law and order situation of Nepal."[72]Nepal's Public Security Act (PSA) allows for the use of preventive detention for 90 days by order of the chief district officer. This can be extended for six months on the approval of the Home Ministry "to maintain sovereignty, integrity or public tranquility and order." Only on one occasion, when three Tibetans were arrested on June 19, has the government of Nepal invoked the PSA to justify arrests of Tibetans (see below).

International human rights law makes provisions for circumstances in which the right to liberty can be temporarily abrogated. Such derogation, however, must be of exceptional character where the life of a nation is threatened, strictly limited in time, subject to regular review, and consistent with other obligations under international law.[73]Nepal has not asserted that the Tibetan protests pose such a threat to Nepal, nor has the Nepali authorities' response met the standards required for derogation from fundamental rights.

Preventive detention under the Public Security Act

On June 19, 2008, two Nepali citizens of Tibetan origin, Nawang Sangmo and Tashi Dolma, President and Vice President of the Tibet Women's Association, and one Tibetan refugee, Kelsang Chung, director of the Tibet Reception Centre, were arrested from their homes without an arrest warrant. The detention order accused them of carrying out "acts that affect national security and public order by chanting anti-China slogans in different public places in the capital."

The three were taken to the Boudha Police Station before being transferred to Hanumandhoka Police Station, where they were given a preventive detention order issued by the Kathmandu CDO. The order stated that the arrests were necessary to bring an end to demonstrations organized by Tibetan refugees in Nepal as continued demonstrations could have an impact on public peace and security, as well as Nepal's friendly relations and diplomatic ties with China. The order was issued under section 3.1 of the Public Security Act 2046, which states:

The Local Official, if there are reasonable and sufficient grounds to prevent a person immediately from committing specific activities likely to jeopardize the sovereignty, integrity, or public tranquility and order of the Kingdom of Nepal, may issue an order to hold him/her under preventive detention for specified term and at specified place.

This is the first occasion known to Human Rights Watch that the Public Security Act has been invoked to allow preventive detention since the reestablishment of democracy in Nepal in April 2006.

After receiving the written order the three were transferred to Dilli Bazar Jail. Later that day, Nawang Sangmo and Tashi Dolma were transferred to Badrabandi Central Jail. Habeas corpus writs were filed with the Supreme Court for the three detainees on June 22. During the hearing in the Supreme Court on June 23 and 24 the Court ordered the government of Nepal to "show cause" for the arrests. The Supreme Court usually expects the government to "show cause" within three days but in this case the government took advantage of the legal option to request an extension of seven days to "show cause."

The next hearing took place on July 8, during which the Supreme Court stated that the order issued by the Kathmandu CDO and the written submission of the Home Ministry failed to satisfy the grounds maintained in the PSA and ordered the individuals released. Normal practice is for the jail authority to then release the individuals immediately. But this did not happen, as the lawyer representing the three was told by the authorities that that the jail authorities were waiting for an order from the Home Ministry. The three were released later that day, July 8, 2008.[74]

V. Treatment in Detention

Beatings

Since March 10 there have been four reported incidents of multiple beatings of Tibetans in detention. Three incidents took place at Boudha Police Station on March 10, 14, and 25, with a fourth at Singh Durbar Police Station on March 31.

On March 10, police beat 14 Tibetans at Boudha Police Station following their arrest during protests in the area. The 14 arrived in police vans in two or three groups. The vans drove inside the gate and then the police dragged them into the station past a line of eight or nine policemen who kicked and punched them. A female assistant subinspector of police ordered the officers to hit and kick them, and one woman was dragged inside by her hair. Once all the protesters were inside the police station, the beatings stopped. They heard a second group of Tibetans shouting and crying in pain as they were dragged into the police station in a similar manner. The DSP told the group: "You are criminals and you are forcing us to hit you."[75]

On March 14, police badly beat three Tibetan male protesters arrested individually inside Boudha Police Station between 6:30 and 7:30 p.m. Tsering Singe, age 32, was protesting just outside the Boudha Stupa gate when police approached him and took his headscarf and threw his candle away. They then hit him with a lathi and told him to run away. When he didn't run away, five or six policemen started pulling his hair, kicking and punching him, and then began to hit him with their lathis, including in the head, for around two minutes. He saw the same being done to others. They then dragged him inside the courtyard of the station, where for about six minutes he was kicked in the stomach, hit with lathis on his legs, and punched in the head. The police took him inside the station, where they hit him while he was standing and then pushed him onto a chair, where they continued to beat him.

A second Tibetan was then dragged into the courtyard shouting in pain. The police stopped beating Tsering Signe and ran outside to the courtyard to beat the new arrival. Tsering Signe saw the second man on the ground surrounded by around seven policemen who were hitting him with lathis, and kicking and punching him on the legs and shoulders. After about two minutes, Tsering Signe went outside to help the man come inside and asked the police to stop beating him. The policemen continued to beat Tsering Signe and the other man for another two minutes. The police then hit the second man on the thighs, ankles, and head (and on the hands when he tried to protect his head) for about three minutes until one of the lathis broke. After another lathi was fetched, the beating recommenced for a further two minutes and only stopped when a third man was brought inside. The third man told Tsering Signe that he had been beaten in the courtyard. Five or six policemen were involved in these beatings inside the police station building, during which the men were also verbally abused. The men were then told to sit on a bench for a further 30 minutes. All three men sought medical care following their release.[76]

On March 25, around 71 individuals were released from detention at 9.45 p.m.. Some made their own way home while the remaining 66 boarded two buses arranged to take them back to Boudha. Eight additional Tibetans also bordered these buses to return home to Boudha. All 74 people on the buses were arrested about 10.15 p.m.. Around five or six police officers forced the two buses to stop around 500 meters from the Boudha Police Station and entered the buses. The buses then continued forward along the road and reached a roadblock, where the Tibetans were forced out and dragged into the police station past a line of police officers. Some reported being beaten as they were dragged inside. They were then separated into two groups, with some taken upstairs to meet the DSP and others kept downstairs. Those kept downstairs were asked to put out their hands and were threatened with lathis, and one man was hit. They were told that if they protested the following day the police would "cut off their hands and legs." One man who asked why they had been arrested was slapped in the face by a plainclothes police officer. Individuals in the group taken upstairs were verbally threatened and questioned (see section on threats of deportation and violence below). All of those detained were released around 11 p.m. after having their photographs and names taken.[77]

On March 31, Dawa, age 37, Nawang Tenzin, age 28, Lobtang Tuboho, age 18, and Nawang Tenzin, age 33, were beaten at Singh Durbar Police Station. These four men were the last of a group of detained Tibetans to arrive, and instead of being kept in the courtyard of the police station with the others, they were forced into a cell. In the doorway of the cell the police hit one on the back with a rifle butt and hit and kicked the others on the shoulders. Once inside the cell they begged the police to stop beating them. The Tibetans in the courtyard started yelling for two to three minutes that they wanted to be with the ones inside the cell, and a subinspector of Police responded by ordering the release of the men in the cell.[78]

Sexual harassment of women

The DSP at Boudha Police Station sexually harassed two female Tibetan protesters on March 25, ordering the women to be brought separately into his office between 10 and 11 p.m.. The first, Tenzin Palzom, age 28, was brought in and had the door locked behind her after she said in a group setting that she would continue to protest. The DSP said, "Why are you protesting? We could hand you over to the Chinese authorities." He then proceeded to close the curtains in the room and said something like "The Chinese love her and he loves her too." Tenzin Palzom panicked and tried to open the door. The DSP then pressed a button, and the door was opened from the outside and she was allowed to leave.[79] Tenzin Palzom said, "I felt like I was going to be sexually assaulted by him." The second woman, Nima Sangmo, age 33, was then brought into the room. The DSP asked her for her name, address, the name of her husband, what work she and her husband did, how many children she had, the name of her housekeeper, and her phone number. Nima Sangmo was sitting on the sofa in the DSP's office with the DSP sitting in front of her. The DSP asked if he could sit next to her and if he could have a kiss. Nima Sangmo replied no and was allowed to leave the office. As she left the room the DSP said "Can I have you?"[80]

We did not receive other reports of this type of sexual intimidation of detainees and these appear to have been isolated incidents. Regardless, action should be taken to discipline the police officer involved.

Denied or restricted medical care

The authorities have often provided Tibetan detainees inadequate medical care, and at times have denied medical care altogether. There appears to have been some minor improvement in provision of medical care starting in mid-April, but authorities have not been consistent. On some days medical care is more readily provided than on others without any clear across-the-board improvement.

The Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Rule 22), the Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners (Principle 9), and the Body of Principles for the Protection of All persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment (Principle 24) all protect the right of detainees to access medical care. The Standard Minimum Rules ensure access to specialist medical care where necessary. By denying detained Tibetans access to medical care, the Nepal Police are failing to meet these international standards. Purposefully withholding assistance can constitute cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, and even torture, under international law.

Denial of medical care appears to have been worst at Ghan II Police Barracks. Individuals detained at other locations have also reported denial of or delayed access to medical care, although not as consistently as those detained at Ghan II Police Barracks. This may be due to fewer and less regular detentions at other locations, rather than a difference in police behavior.

A man whose teeth were broken as a result of being struck with a rifle butt was not provided with medical care during his detention. A young man with blood in his feces, who was vomiting and experiencing dizziness possibly because of being hit on the head with a lathi, was not provided with medical care despite being told that a doctor would come.[81] On April 2, a monk was denied medical care by police from Kamal Pokhari Police Station for over one hour, despite excessive vomiting and periods of unconsciousness and friends repeatedly seeking medical care for him.[82]

In another case, a young woman was denied medicine to prevent an epileptic fit, despite a human rights worker being inside the gate of Ghan II Police Barracks with the medicine. Her condition deteriorated so badly over the 90 minutes that she was denied medical care that police eventually gave permission to a group of male Tibetan detainees to carry her to a nearby hospital. The same woman fainted at Jawalakel Police Station on another occasion, and when her friends requested medical care they were told, "Wait, wait" by the police. After her condition deteriorated over the next 30 minutes, the police eventually took her to PatanHospital in a police jeep.[83]

On March 10, Nima Tsering, age 61, asked to see a doctor when he was detained at Gausala Police Station, as he had fainted on the street due to a police beating. The police officers said they could not do anything for him and did not even provide him with water.[84] On March 29, a monk fell unconscious at Ghan II Police Barracks; his friends and a human rights worker sought medical care for him over a period of one hour. The inspector responded that the monk had no visible wounds, but he would bring a doctor. No doctor came in the next 45 minutes, despite the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights seeking treatment for him.

The few individuals who have received medical care have always been returned to detention at Ghan II Police Barracks, an open yard, following the provision of care. This included three monks who were unable to walk unassisted, the young woman who suffered from an epileptic fit, a minor who had fainted, the unconscious monk, and many others. In one case a woman in visible pain and unable to walk unaided was forced to return from the hospital to the open yard. She had recently had surgery on her stomach and had been hit in the stomach during the protest. It was only after extensive negotiations by a human rights worker that the woman was allowed to seek further medical care.

Human Rights Watch has also received several reports of individuals who have fainted or lost consciousness during arrest, and who have woken up in the back of a police truck or van or at the place of detention, instead of being given medical attention.

Substandard conditions in detention

None of the detention facilities in Kathmandu is equipped to deal with the large numbers of people that have been arrested since the start of the demonstrations, particularly for overnight detention. Ghan II Police Barracks, where many Tibetans have been detained, is not a regular detention facility; it is not equipped to detain large numbers of people and has none of the necessary basic facilities to accommodate overnight detentions. Nevertheless, individuals have been held at Ghan II overnight on two occasions (April 2 and 16).

At Ghan II Police Barracks, the detainees are kept in a large outdoor yard area resembling a playing field, with limited shade from nearby trees. There is a basic toilet block that may be adequate for small numbers of detainees. If it rains, the detainees are moved into a nearby shed that is regularly used by the police for sleeping, but the mattresses, blankets, and sometimes wooden bed bases are removed, forcing the Tibetans to sleep on the concrete floor. This indoor space is not large enough to house large numbers of detainees.

At other locations, detainees have usually been kept in the courtyard of the police station for the period of their detention. On some occasions, however, Tibetans report that they have been held in large numbers in small cells for a couple of hours before being allowed to stay in the courtyard. They describe being unable to sit down in the cell due to limited space.

The Nepali authorities have not provided Tibetan detainees with food or water, which instead has been provided by friends and family of the detainees. It has generally been difficult and time-consuming to negotiate with the police to allow these items to be taken inside the Ghan II Police Barracks, and on some occasions the police have refused to allow food, clothing, and blankets to be provided to detainees.[85]

VI. Threats, Harassment, and Intimidation of Tibetans

Threats of deportation

Police have routinely threatened Tibetans with deportation to China during arrests and while holding them in detention. The authorities' widespread use of this threat suggests it is Nepali government policy and could be considered a form of state-sponsored intimidation. Security force commanders know or should know their officers are threatening Tibetans with deportation and thus should be held accountable for the continuing threats.

Under the Convention against Torture, Nepal may not deport anyone to a country where they may face torture.[86] Customary international law also prohibits refoulement (return) of refugees to places where a person would face a threat of persecution. The UN special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment has cited China for its abuse of political dissidents.[87] Those of Tibetan origin who have been protesting Chinese rule in Tibet would almost certainly be treated as dissidents or even separatists.

Nearly all Tibetans involved in protests interviewed by Human Rights Watch say they have been threatened with deportation, many on several occasions. Most people interviewed reported junior police officers telling them, "If you protest tomorrow we will send you back to China," or "I will confiscate your Refugee Card and send you back to China." These threats were usually made in detention and sometimes during arrest.[88]

Officers as senior as a DSP have similarly threatened large groups in detention. For example, on March 15, a police officer at Jawalakel Police Station said to a group, "We will deport you to China, and you know how they will kill you."[89]

Around on March 24, the authorities ordered the 241 Tibetans detained at Jawalakel Police Station to line up with men on one side and women on the other. A senior police officer in civilian clothes then entered the compound and said, "If you make disturbances like this, then we will take you to the border and hold you there for two to three months. I have the authority to send you back to China or hold you at the border for two or three months."[90] On April 3, a police officer told detainees held overnight: "We will check everything. Give your name and details. We have a law to surrender you back there [China]."[91] Also on April 3, after being held overnight, detainees were told, "Since you are protesting continuously we are going to check who has a Refugee Card or citizenship, and people who have no identity we will hand you to the Chinese."[92] On April 15, a senior police officer from Kamal Pokhari Police Station required those held at Ghan II Police Barracks to show their ID cards, and later a Ghan II police officer threatened the same group with deportation to China if they could not produce proof of refugee status in Nepal.[93]

Some Tibetans have received individualized threats of deportation. For example, around 10:30 p.m. on March 25, following the arrest of 74 individuals[94] at Boudha Police Station, a 26-year-old woman who said she would continue to demonstrate was put into a room alone with the DSP. The DSP said, "Why are you demonstrating? We could hand you over to the Chinese authorities."[95] Another woman perceived as a protest leader was pointed at and told at Jawalakel Police Station, "If you demonstrate tomorrow we will lathi charge you and hand you over to the Chinese." On a separate occasion, also at Jawalakel Police Station, a police officer told her, "If you come tomorrow we will put you in a truck and send you back to Tibet. We don't care about the media and the UN. We are going to hand all Tibetans back to Chinese, and we will raise a stick to all Tibetans."[96]

Given the history of deportation of Tibetans from Nepal, the widespread and consistent nature of the threats, and the danger presented, Tibetans who spoke with Human Rights Watch take the threats very seriously.

Threats of violence

Police have used the threat of serious violence both in detention and on the streets of Kathmandu. The most commonly reported threat of violence has been beatings if protesters continue to protest. When police rearrested the group of Tibetans outside Boudha Police Station on March 25, an officer said, "As soon as there is a protest you are the ones at the front. If you are there tomorrow we will cut off your hands and legs." Tashi Dolma reported police saying to her, "If you are not following orders then I will kill you."[97]

Several Tibetans have also reported threats of violence associated with fulfilling requests by the police, such as, "If you don't give your mobile phone we will hit you with the lathi," or, "If you are not silent we will beat you."[98]

Police surveillance and visits

A small group of Tibetans have reported that the police have placed them under regular surveillance. Perceived leaders of the protests report sighting individuals in civilian dress that they assume to be police posted outside their homes, and uniformed police making regular visits to their neighborhoods. They have also reported being followed by such people on the street. Those carrying out the surveillance change regularly, but the families of the individuals who report the surveillance say they are beginning to recognize the faces.

Several locations have also been under police surveillance. For example, Jawalakel Tibetan Camp has had several visits by plainclothes police officers. Such a visit was particularly obvious on March 20, when four police officers from Jawalakel Police Station visited the camp and were recognized by local residents. The police tried to speak with a group of Tibetans in a tea shop and made one round of the camp on foot. One police officer returned later on a motorbike to make a second round of the camp. On the same day a uniformed police officer asked at the school gate what the program inside the camp was that day. On a separate occasion, Lhundup Gyatso reported seeing individuals in civilian clothes moving about inside the camp with walkie-talkies. Tibetan children ages 11 to 13 who live in the camp have reported being asked by police where their elders are.[99]

Uniformed police officers have visited the TibetReceptionCenter on three occasions since March 10-once on March 31 and twice on April 1. Such visits are considered unusual. The police officers asked the gatekeeper, "Any functions at TRC today? Any people went out from TRC today?" On one occasion TRC staff went to speak to the police officers and were asked, "You people are protesting in front of the Chinese Embassy. Is there any program around Swyambu?"[100]

Kunsang Chodrak reported that the Kopan Monastery received a visit by the police. This was particularly unusual in that the police offers actually entered the monastery.[101]

The nunnery at Swyambu, which is located directly next door to a police station, has received several visits by local police. Human Rights Watch observed one such visit by three police officers on March 3 at 7:40 a.m.. The visits have been associated with the short-term de facto house arrest of the nuns on some days and on other days the nuns feeling less free to leave the Swyambu area.[102]

Other Tibetans who joined protests have reported being followed by the police. Tenzin Lhanzom, age 15, reported being followed to a shopping mall near the Chinese Embassy by a plainclothes policeman on April 2.[103]

Taking of photographs

On some occasions Tibetan protesters have been photographed in detention, police officers telling them, "If I see you tomorrow protesting we will see you because we have your picture," or, "Now we have your photo we will recognize you. Now if you go to protest you will have a difficult life."[104] While detainees were standing in line to be photographed during the re-arrest on March 25, a Nepali man came with a video camera and filmed everyone in the line, and those who attempted to turn their heads were forced to look at the camera. While this filming was being conducted, a police officer said, "Why did you come here? You motherfucker, why are you protesting here? If you protest tomorrow we will deport you back to China."[105] Tibetans have reported being scared that their photographs will be given to the Chinese or used to identify them for arrest or deportation.

Tibetan refugees in Nepal are well informed of how "separatists" are treated in China, and they have told Human Rights Watch that their fear of deportation is even greater with the risk of being labeled as such by the Chinese government.

Making lists of those to be detained

On March 17, members of the Tibetan community learned from a reliable source that a list had been drawn up of 11 Tibetans who were current or former leaders of local Tibetan organizations. Human Rights Watch was provided with the names of the 11 people on the list. When a senior Nepali lawyer asked a senior member of the Nepal Police about this list, he was told that arrest warrants had not been issued for the people on the list, but that the possibility of preventive detention could not be ruled out. Human Rights Watch was told by leading figures in the Tibetan community that another five people were later added to the list. It is believed the list was created to instill fear within the Tibetan community. This is of particular concern to Human Rights Watch, given the previous use of "blacklists" of human rights activists and political activists by the Nepali authorities in December 2004 and February 2005.[106]

VII. Restrictions on Freedom of Movement, Expression, and Assembly

The Nepali government has restricted the movement of Tibetans within the KathmanduValley, individually and in groups, since March 10. Nuns, monks, and elderly religious practitioners who regularly move between the three main Tibetans areas (Swyambu, Boudha, and Jawalakel) for religious purposes, particularly for performing puja (prayers), have been impeded from moving and sometimes arrested.

International human rights law prohibits restrictions on the freedom of movement, including that of non-nationals, except when the restrictions are prescribed by law, are "necessary to protect national security, public order, public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others," and are consistent with the other fundamental rights.[107] The restrictions placed by the Nepali government on Tibetans have not met these requirements.