"When I Die, They'll Send Me Home"

Youth Sentenced to Life without Parole in California

This report is dedicated to Roland Algrant, a compassionate and wise human rights activist who died on December 19, 2007. One of the founders of Human Rights Watch, he served for many years as the vice-chair of the Advisory Committee of the Human Rights Watch Children's Rights Division. In 2005 Mr. Algrant's friends created the Roland Algrant Summer Internship program in his honor. The first Roland Algrant Summer Intern, Christine Back, took part in the research and writing of this report.

This report would not have been possible without the compassion, insight, and generous support of Wendy and Barry Meyer.

Summary

"When I die, that's when they'll send me home."

Approximately 227 youth have been sentenced to die in California's prisons.[1] They have not been sentenced to death: the death penalty was found unconstitutional for juveniles by the United States Supreme Court in 2005. Instead, these young people have been sentenced to prison for the rest of their lives, with no opportunity for parole and no chance for release. Their crimes were committed when they were teenagers, yet they will die in prison. Remarkably, many of the adults who were codefendants and took part in their crimes received lower sentences and will one day be released from prison.

In the United States at least 2,380 people are serving life without parole for crimes they committed when they were under the age of 18. In the rest of the world, just seven people are known to be serving this sentence for crimes committed when they were juveniles. Although ten other countries have laws permitting life without parole, in practice most do not use the sentence for those under age 18. International law prohibits the use of life without parole for those who are not yet 18 years old. The United States is in violation of those laws and out of step with the rest of the world.

Human Rights Watch conducted research in California on the sentencing of youth offenders to life without parole. Our data includes records obtained from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and independent research using court and media sources. We conducted a survey that garnered 130 responses, more than half of all youth offenders serving life without parole in California. Finally, we conducted in-person interviews of about 10 percent of those serving life without parole for crimes committed as youth. We have basic information on every person serving the sentence in the state, and we have a range of additional information in over 170 of all known cases. This research paints a detailed picture of Californians serving life without parole for crimes committed as youth.

In California, the vast majority of those 17 years old and younger sentenced to life without the possibility of parole were convicted of murder. This general category for individuals' crimes, however, does not tell the whole story. It is likely that the average Californian believes this harsh sentence is reserved for the worst of the worst: the worst crimes committed by the most unredeemable criminals. This, however, is not always the case. Human Rights Watch's research in California and across the country has found that youth are sentenced to life without parole for a wide range of crimes and culpability. In 2005 Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch published a report showing that nationally 59 percent of youth sentenced to life without parole are first-time offenders, without a single juvenile court adjudication on their records.

In 2007, Human Rights Watch surveyed youth offenders serving life without parole in California. In 45 percent of cases surveyed, youth who had been sentenced to life without parole had not actually committed the murder. Cases include that of a youth who stood by the garage door as a look-out during a car theft, a youth who sat in the get-away car during a burglary, and a youth who participated in a robbery in which murder was not part of the plan. Forty-five percent of youth reported that they were held legally responsible for a murder committed by someone else. He or she may have participated in a felony, such as robbery, but had no idea a murder would happen. She or he may have aided and abetted a crime, but not been the trigger person. While they are criminally culpable, their actions certainly do not fall into the category of the worst crimes.

Murder is a horrible crime, causing a ripple-effect of pain and suffering well beyond that of the victim. Families, friends, and communities all suffer. The fact that the perpetrator is legally a child does nothing to alleviate the loss. But societies make decisions about what to weigh when determining culpability. California's law as it stands now fails to take into consideration a person's legal status as a child at the time of the crime. Those who cannot buy cigarettes or alcohol, sign a rental agreement, or vote are nevertheless considered culpable to the same degree as an adult when they commit certain crimes and face adult penalties. Many feel life without parole is the equivalent of a death sentence. "They said a kid can't get the death penalty, but life without, it's the same thing. I'm condemned…I don't understand the difference," said Robert D., now 32 years of age, serving a life without parole sentence for a crime he committed in high school. He participated in a robbery in which his codefendant unexpectedly shot the victim.

The California law permitting juveniles to be sentenced to life without parole for murder was enacted in 1990. Since that time, advances in neuroscience have found that adolescents and young adults continue to develop in ways particularly relevant to assessing criminal behavior and an individual's ability to be rehabilitated. Much of the focus on this relatively new discovery has been on teenagers' limited comprehension of risk and consequences, and the inability to act with adult-like volition. Just as important, however, is the conclusion that teens are still developing. These findings show that young offenders are particularly amenable to change and rehabilitation. For most teens, risk-taking and criminal behavior is fleeting; they cease with maturity. California's sentencing of youth to life without parole allows no chance for a young person to change and to prove that change has occurred.

In California, it is not just the law itself that is out of step with international norms and scientific knowledge. The state's application of the law is also unjust. Eighty-five percent of youth sentenced to life without parole are people of color, with 75 percent of all cases in California being African American or Hispanic youth. African American youth are sentenced to life without parole at a rate that is 18.3 times the rate for whites. Hispanic youth in California are sentenced to life without parole at a rate that is five times the rate of white youth in the state.

California has the worst record in the country for racially disproportionate sentencing. In California, African American youth are sentenced to life without parole at rates that suggest unequal treatment before sentencing courts. This unequal treatment by sentencing courts cannot be explained only by white and African American youths' differential involvement in crime.

Significantly, many of these crimes are committed by youth under an adult's influence. Based on survey responses and other case information, we estimate that in nearly 70 percent of California cases, when juveniles committed their crime with codefendants, at least one of these codefendants was an adult. Acting under the influence and, in some cases, the direction of an adult, however, cannot be considered a mitigating factor by the sentencing judge in California. In fact, the opposite appears to be true. Juveniles with an adult codefendant are typically more harshly treated than the adult. In over half of the cases in which there was an adult codefendant, the adult received a lower sentence than the juvenile.

Poor legal representation often compromises a just outcome in juvenile life without parole cases. Many interviewees told us that they participated in their legal proceedings with little understanding of what was happening. "I didn't even know I got [life without parole] until I talked to my lawyer after the hearing," one young man said. Furthermore, in nearly half the California cases surveyed, respondents to Human Rights Watch reported that their own attorney did not ask the court for a lower sentence. In addition, attorneys failed to prepare youth for sentencing and did not tell them that a family member or other person could speak on their behalf at the sentencing hearing. In 68 percent of cases, the sentencing hearings proceeded with no witness speaking for the youth.

While some family members of victims support the sentence of life without parole for juveniles, the perspective of victims is not monolithic. Interviews with the families of victims who were murdered by teens show the complex and multi-faceted beliefs of those most deeply affected. Some families of victims believe that sentencing a young person to a sentence to life without parole is immoral.

California's policy to lock up youth offenders for the rest of their lives comes with a significant financial cost: the current juvenile life without parole population will cost the state approximately half a billion dollars by the end of their lives. This population and the resulting costs will only grow as more youth are sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in prison.

California is not the only state that sentences youth to life without parole. Thirty-eight others apply the sentence as well. However, movement to change these laws is occurring across the country. Legislative efforts are pending in Florida, Illinois, and Michigan and there are grassroots movements in Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nebraska, and Washington. Most recently, Colorado outlawed life without parole for children in 2006.

If life without parole for youth under age 18 were eliminated in California, other existing state law provides ample protection for public safety. California's next harshest penalty for murder secures a minimum of 25 years in prison. There are no reductions in the minimum time served for a murder conviction. Even then, parole is merely an option and won only through the prisoner's demonstrating rehabilitation. If they do earn release after 25 years or more, they are statistically unlikely to commit a new crime of any type. Prisoners released after serving a sentence for a murder have the lowest recidivism rate of all prisoners.

Public awareness about this issue has increased recently through newspaper and magazine articles and television coverage. With a significant number of the country's juvenile life without parole cases in its prisons, California has the opportunity to help lead the nation by taking immediate steps to change this unnecessarily harsh sentencing law.

Methodology

This report is based on data from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation obtained in April 2007, as well as Human Rights Watch's media and court records searches, in-person interviews, and a survey of people in California serving life without parole for crimes committed under the age of 18.

Human Rights Watch made a Public Records Act request in June 2006 to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) for public records regarding juveniles sentenced to life without parole. The data was provided to us in April 2007. The data from the CDCR includes name, prisoner number, race, gender, birth date, date of offense, age at time of offense, controlling county, and the facility where the individual was held at the time. According to this data, 227 individuals who were under 18 at the time of their crimes were sentenced to life without parole in California as of April 2007. All but four had been sentenced since 1990. Independent Human Rights Watch research determined that three of the names provided by the CDCR were not people serving life without parole, and four additional people who are not on the CDCR list were also sentenced to life without parole for crimes they committed as juveniles. These additional cases were found through interviews and general internet searches. Given the inaccuracies in the data provided to us by the CDCR we believe that there are likely additional youth offenders serving life without parole who are not on the list.

In 2006 and 2007, Human Rights Watch researchers, pro bono attorneys, and numerous volunteers used online legal and press resources to research individual California cases. Based on media sources and online court records, we found information pertaining to 173 of the 227 known cases.

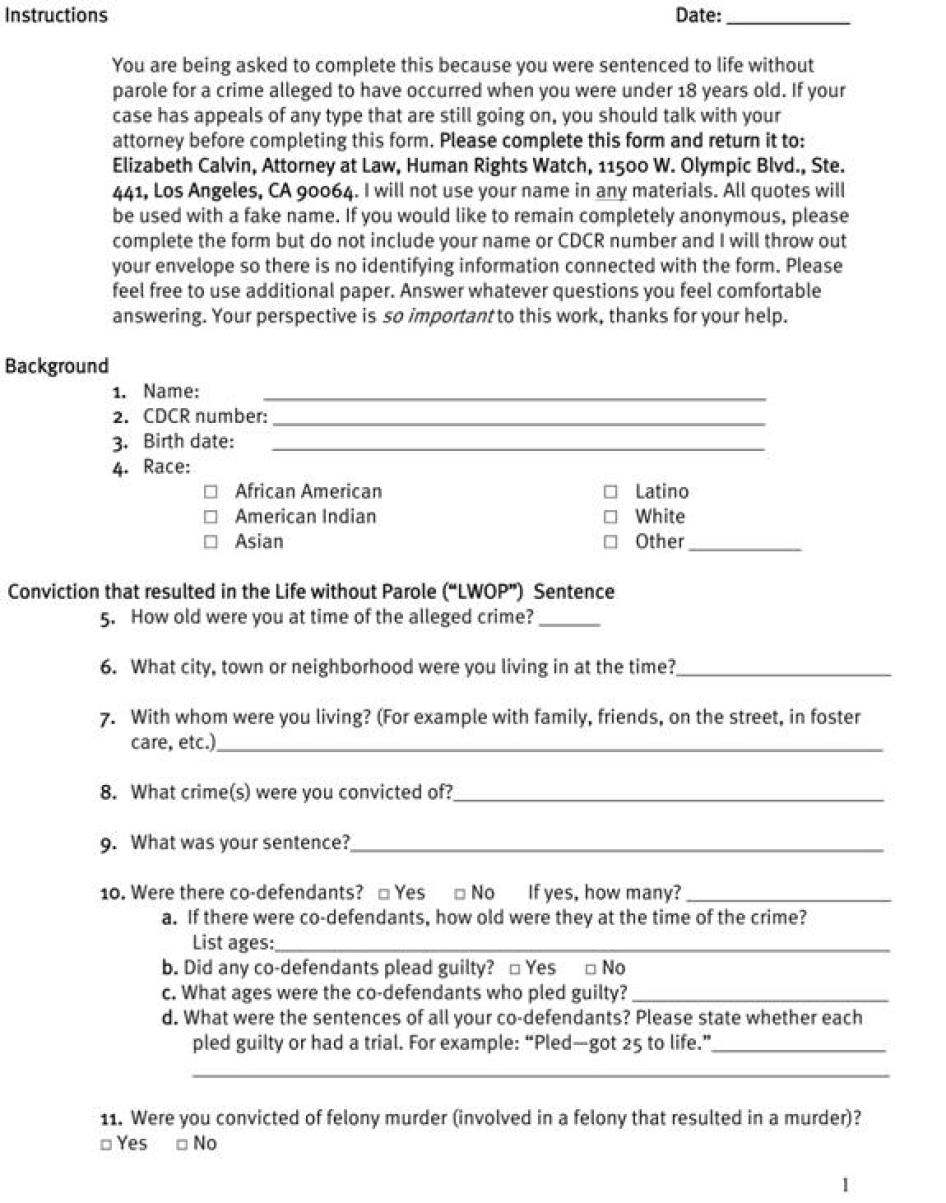

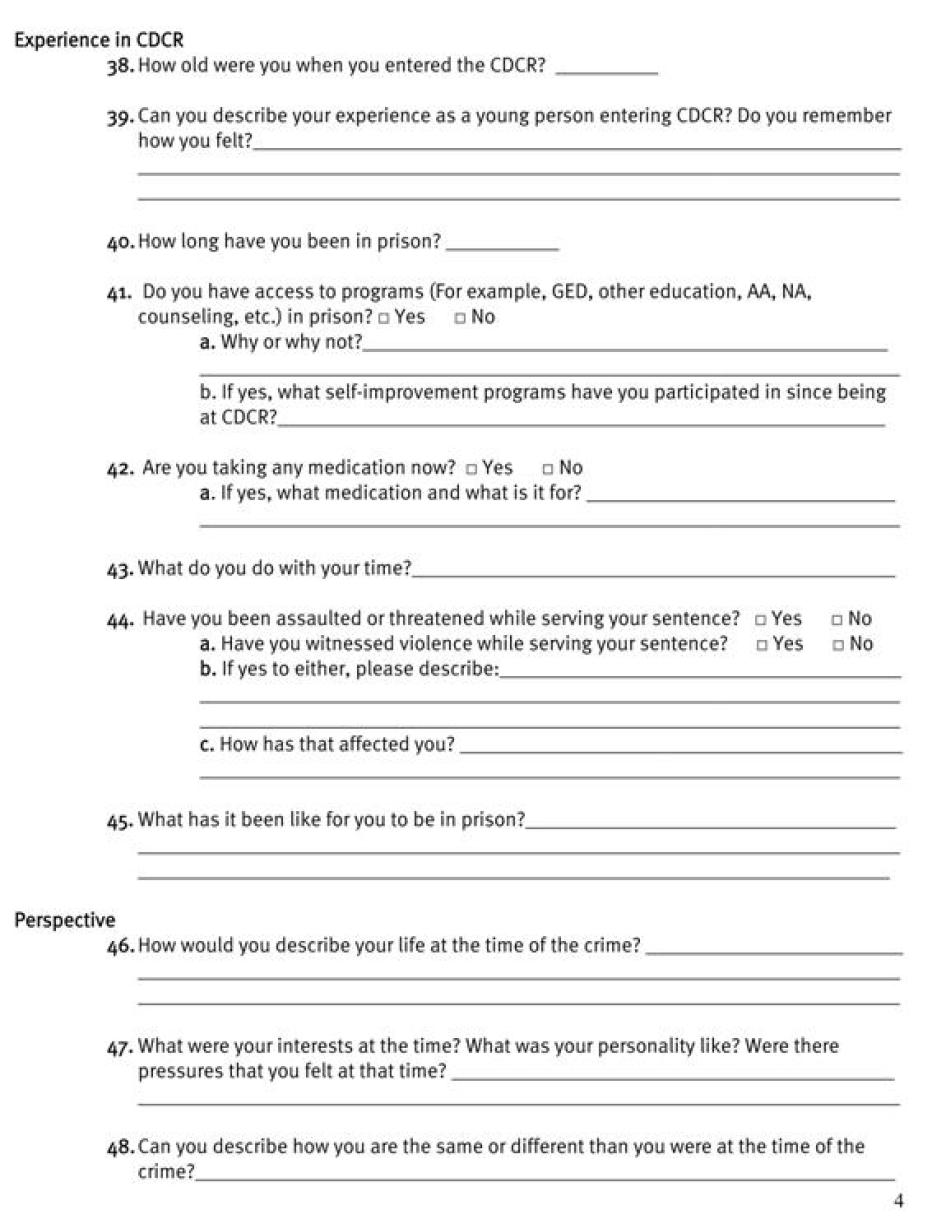

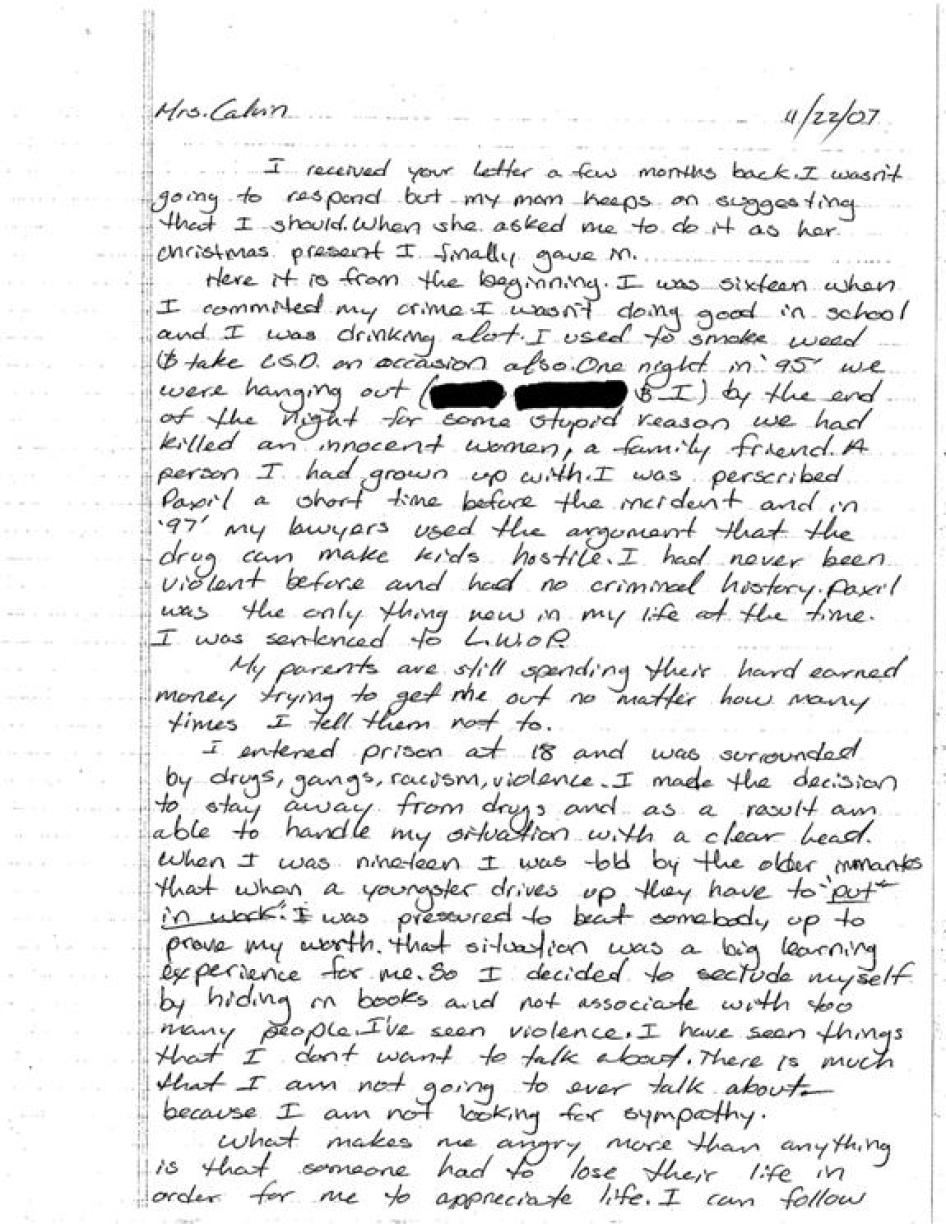

In July 2007, Human Rights Watch sent a five-page survey to all people on the CDCR's list. A copy of the survey is included here in Appendix A. The survey permitted short narrative answers, and some respondents included addendums with lengthy answers. The cover letter explained the survey's purpose and informed recipients that their real name would not be used in published materials and that there would be no personal gain from the information provided.One hundred twenty-seven people responded to the survey, representing more than 50 percent of the known population. The survey is five pages long and asks questions in five sectors, including personal background, information about the case, their experience of trial and sentencing, conditions in prison, and their feelings. Several sample responses are included in Appendix B.

Twenty-seven in-person interviews were conducted in California prisons, representing more than 10 percent of the California juvenile life without parole population. All but one of the interviews were carried out by Human Rights Watch researchers and volunteers; one was conducted by Patricia Arthur, a Senior Attorney at the National Center for Youth Law. No incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed. Interviewees were assured of confidentiality and gave a signed consent for their information to be used by Human Rights Watch.

We conducted interviews in eight prisons, five in southern California and three in central or northern California. We selected interviewees based on several factors. First, we chose people whose cases were at least four years old to increase the likelihood that their appeals had concluded in order to avoid potential interference with their cases. Second, we sought locations in which there were several potential interviewees. We chose to conduct the interviews at a number of locations in order to obtain a variety of experiences and account for differences in inmate classification or specific prison policies. We looked for a racial or ethnic mix of interviewees that would provide a sample reflecting a racial makeup more or less similar to that of California's general population. Finally, where we had additional information about the nature of the case, we sought to select individuals representing a variety of cases.

Interviews were conducted at prisons, typically in a small room located in the visiting area. Although the room had a window, the door was closed for privacy. Some interviews took place in a large visiting room, and the interviewer and subject sat in a corner, as much as possible out of earshot of guards and other prisoners. In three cases, interviews were conducted through glass, with the interviewee and interviewer talking over a telephone. In those and one other case, interviewees had feet shackled and hands cuffed and locked to a chain around their waists.

Interviews lasted from 30 minutes to three and a half hours. In most cases there was one interviewer; in a few, two interviewers were present. Just one prisoner was interviewed at a time.

Much of the data used in this report is self-reported. Human Rights Watch did not have the resources necessary to obtain court records and transcripts of trials, which would have provided substantial additional data to that provided by survey respondents. California's criminal justice system is county-based, and has 58 counties. Each case would require a request, in some cases, in-person, for court records at the county courthouse where the case was heard. Many court records are already in storage due to the age of the case. Once records are obtained, a transcript of proceedings would have to be commissioned.

However, Human Rights Watch's survey and interviews were set up in ways to reduce the risk of informants providing misleading responses. For example, the anonymity of the information decreased the chance that respondents fabricated information for personal gain. Some questions were cross-checked for accuracy. In addition, while varying in scope and depth, information collected from other sources on over 170 of the 227 known cases of youth offenders serving life without parole, such as court opinions and newspaper accounts of cases, also allowed us to corroborate information reported in the survey, giving confidence in the general accuracy of survey responses and interview testimony.

Pseudonyms are used for all inmates and the facility where people are located, and other identifying facts are not revealed in the report. The level of violence in California's prisons and the likelihood that information people provided Human Rights Watch would be used by prisoners or others to cause harm makes the protection of subjects a priority. The topics addressed in the survey are deeply personal and concern difficult situations in the respondents' lives. People responding had varying degrees of trust that Human Rights Watch could protect them from retaliation. Some respondents expressed fear about whether the information might be used against them by other prisoners or guards. References to violence they have seen in prison, a description of the crime, or even an answer to the question about what they wish they could convey to the victims is information that could result in retaliation.

Inmates were not the only people who were willing to share personal details of their lives for this report. Human Rights Watch also interviewed five family members of victims who had been murdered by juveniles and who shared with us deeply personal pain and loss. It was our intention to provide insight to the spectrum of victim perspectives on the issue of life without parole for juveniles. These individuals were found by searching online and by word of mouth. We contacted victims' rights groups, and asked for suggestions. One interviewee was referred by a chaplain, another was suggested by an interviewee who knew another victim with a very different perspective than her own. In another case we were able to identify the family member of a victim through the survey response. We then asked for permission to contact her. While this small group is in no way a representative sample of all victims, we hope their perspectives will provide some insight into the complexity and richness of victim responses. All of the victims interviewed were activists on different issues, including victims' rights, anti-violence work, mentoring at-risk youth, and abolition of the death penalty. The fact that they are activists made it possible for us to find them. In all cases, these victim family members agreed to the publication of their real names.

Recommendations

To the Governor of California

- Support the abolition of the sentence of life without parole for youth under the age of 18.

- Where youth are sentenced to prison terms, ensure meaningful opportunities for rehabilitation, education, and vocational training.

- Periodically assess the eligibility of youth offenders to parole.

To the California State Legislature

- Enact legislation abolishing the sentence of life without parole for youth who were under the age of 18 when they committed their crime.

- Enact legislation that creates meaningful opportunities for rehabilitation, education, and vocational training for people who are sentenced to life terms.

To State and County Officials

- Ensure indigent juvenile defendants facing life without parole receive adequate legal representation that meets their specific needs.

To State Judges

- Refuse to impose the sentence of life without parole on youth who committed their crime under the age of 18 on the grounds that California's law violates international law.

To California District Attorneys

- Support abolishment of the sentence of life without parole for juveniles in California law.

- Exercise the discretion provided under California law to recommend sentences other than life without parole for juveniles.

To Defense Attorneys

- Ensure that defendants and their families understand the procedures, defense strategies, and seriousness of the charges, including the possible sentence of life without parole, so that they can fully exercise their rights.

- Vigorously defend the rights of juvenile clients in adult court at all stages of the case, including trial plea bargaining and the sentencing phases.

Teenagers Sentenced to Die in California Prisons

[There's] no doubt in my mind that he should be where he is, just not forever.

-Mother of a 17-year-old who was sentenced to life without parole.[2]

The 227 people who have thus far been sentenced to life without the possibility of parole in California have one thing in common: when they were considered children under every other law, they faced adult criminal penalties for their actions and were sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in prison. In California "life without parole" means just that: absolutely no opportunity for release. It is, most accurately, a sentence until death. "When I die, that's when they'll send me home," said Charles T.[3]

In the United States at least 2,380 people are serving life without parole for crimes they committed when they were under the age of 18.[4] This practice violates international human rights law, which strictly prohibits the use of life without parole for those who are not yet 18 years old.[5]

Actual practice of states shows that the United States is out of step with most of the world. Research has found only seven individuals serving the sentence for a childhood crime outside the United States.[6] Although other countries have laws permitting life without parole, only ten retain the sentence for those under age 18, but nine of these countries have no persons serving life without parole who committed the crime under the age of 18.[7] Only one other country in the world continues to actually use the sentence for those ages 17 and younger.[8]

All but a handful of the youth sentenced to life without parole in California are boys; of the at least 227 sentenced between 1990 and mid-2007, only five were girls.[9]

California's law permits youth as young as 14 to be sentenced to life without parole for certain crimes. Most of the 227 were 16 or 17 years old at the time of the crime: 41 percent were 16 years old, and 55 percent were 17. The remaining four percent were 14 or 15 years old when the crime took place.[10]Billy G. was 17 years old at the time of his crime and had never lived away from home. The only job he had held was at a concession stand at the local county fairgrounds. "I didn't have any facial hair-I learned how to shave and become a man in prison," he told us.[11]

There are several striking common characteristics among much of those sentenced as youth to life without parole. These characteristics do not fit what might be the typical image of an irredeemable individual, separated from community and family.

Perhaps most remarkably, the crime for which these youth receive sentences of life without parole is often their first one. In a national study of juveniles serving life without parole, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch found that in 59 percent of juvenile life without parole cases surveyed, the juvenile was a first-time offender, with no juvenile or adult record.[12] While there is no question that crimes incurring a life without parole sentence are serious, many individuals committing these crimes had no track record of incorrigibility before being sentenced to life with no chance of parole.

In nearly three out of four cases Human Rights Watch surveyed in California, youth had strong ties to family and community, a factor that generally weighs heavily in the success of rehabilitation.[13] At the time of the crime, 71 percent of the juveniles were living with one or both parents. Another 11 percent reported that they were living with other relatives. Only a few were living without the family connection or adult direction that one might assume would lead to criminal involvement: 6 percent were homeless at the time of the crime, 4 percent were living with friends, and 1.6 percent were in foster care. For many, family ties remain after incarceration. Nearly 80 percent of those surveyed said they had family visits in prison, and 52 percent of those reported having visits ranging from several times a year to as often as every week. As Raymond M. observed of his fellow youth offenders serving life without parole: "With the support system they have on the outside, they're the ones who can succeed."[14]

Another factor that does not fit with the stereotype of a young person in prison is that nearly 60 percent had completed grades 10, 11, or 12 before their arrests.[15]

Why Youth are Serving Life without Parole in California

A conviction in criminal court means punishment: retribution is the primary objective. In contrast, the juvenile justice system is built on the recognition that young people should be given second chances and the tools to turn their lives around. While punishment is one goal, juvenile court also aims for rehabilitative treatment and remedial support. A teen tried in adult court, however, faces an adult sentence, including the most serious penalties available under the law, with the exception only of the death penalty. When the sentence is life without parole, a decision has been made to throw that young person's life away.[16]

In California there are several mechanisms by which someone under the age of 18 can end up in adult criminal court, facing adult penalties. A judge can preside over a "fitness hearing" to assess the youth's amenability to rehabilitation in the juvenile system and the seriousness of the crime.[17] In addition, California is just one of 15 states that allows prosecutors to file a case directly in adult court, without a hearing or any judicial oversight determining whether the decision to send a juvenile to the adult system is appropriate.[18] Finally, California is one of 29 states that mandates a juvenile's transfer to adult court if he or she is accused of committing certain crimes.[19]

Crimes that Result in a Life without Parole Sentence

Under California law, certain criminal convictions are presumed by law to result in a life without parole sentence.[20] For example, a judge must sentence a 16-year-old to life without parole if he or she was convicted of murder with special circumstances (discussed in detail below).[21] Life without parole is generally mandatory in such cases, with only one limited exception: if a judge finds good reason to instead impose a sentence of 25 years to life.[22] The California appellate court, however, has made clear that judicial discretion to impose the lesser sentence of 25 years to life operates as the exception, not the rule: "Life without parole is the presumptive punishment for 16- or 17-year-old[s]…and the court's discretion is concomitantly circumscribed to that extent," stated the California Court of Appeals in its 1994 decision People v. Guinn.[23]

Of the 227 youths who have been sentenced to life without parole in California, 217 were convicted of the crime of first degree murder with special circumstances.[24] Some serving life without parole, however, were convicted for crimes other than murder.[25] For example, one person serving life without parole in California was 14 years old when he committed a kidnapping that resulted in his sentence. No one was injured in that incident.[26]

The vast majority youth offender life without parole cases, however, are cases charged as murder with special circumstances. The California Penal Code delineates the circumstances that increase the seriousness of a murder conviction, including a murder committed during the course of a felony, a murder related to gang activity, murder for financial gain, and murder by means of lying in wait, among 22 total special circumstances.[27]

Although the term "murder with special circumstances" may conjure images of the most heinous and calculated homicides, the facts of California's juvenile life without parole cases vary widely in the violence and seriousness and the teenager's degree of participation. There is no question that murder causes far-reaching devastation for families and communities. Not every murder, however, is especially brutal or heinous. Based on interviews and case-specific research, Human Rights Watch found that in cases involving juveniles, the special circumstances are not reliable indicators of the level of violence, premeditation, or responsibility involved in the murder.

Unjust Results

Many Youth Sentenced to Life without Parole did not Actually Kill

Under state law there are several ways in which a person can become criminally responsible for another person's actions. In California a significant number of juveniles sentenced to life without parole were convicted of a murder that they did not physically commit. Forty-five percent of those who responded to Human Rights Watch's survey said they were not convicted of physically committing the murder for which they are serving life without parole.[28]

This "murder once removed" exists in several legal forms.[29] One is "felony murder." Felony murder results when a participant in a felony is held responsible for a codefendant's act of murder that occurred during the course of the felony. A person convicted under the felony murder rule is not the one who physically committed the murder. The law does not require the person to know that a murder will take place or even that another participant is armed.[30] As long as an individual was a major participant in the commission of a felony, he or she becomes responsible for a homicide committed by a codefendant.

In addition to felony murder, juveniles can be sentenced to life without parole for other involvement that falls short of being the trigger person, such as aiding and abetting, or being an accomplice.[31] "I sold the gun to the shooter prior [to] the day of the shooting, plus I gave him a ride from the crime scene," Ruslan D. said, describing his role in a murder committed by his 18-year-old codefendant.[32] Ruslan was convicted for aiding and abetting and was sentenced to life without parole. As one prosecutor said after the sentencing of a juvenile to life without parole, "A lot of kids don't understand aiding and abetting."[33]

A significant number of these cases involve situations of an attempted crime gone awry-a tragically botched robbery attempt, for example-rather than premeditated murder. Under the law, a teen who commits murder in the course of a felony-even when lacking premeditation-will presumptively receive life without parole because of the special circumstance of being engaged in or attempting to commit a felony.[34] Based on available data, this special circumstance is the most frequently imposed out of all the 22 special circumstances, with a significant number based on the felony of robbery.[35]

|

The Worst Racial Disparity in the Nation

In California, as well as at least 10 other states, African American youth are sentenced to life without parole at rates that suggest unequal treatment before sentencing courts. This unequal treatment of youth cannot be explained by white and African American youths' differential involvement in crime alone.

Eighty-five percent of youth sentenced to life without parole in California are people of color, with 75 percent of all cases in California being African American or Hispanic youth (Figure 1). Data from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation shows that 95 are Hispanic and 74 African American. Whites are 44 percent of the state's population but just 15 percent of those sentenced to life without parole as youth offenders.[36]

Figure 1

Source: California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation data, April 2004

We have data on white and African American youth serving life without parole in the United States for 25 out of the 39 states that apply the sentence in law and practice. As illustrated by figure 2 below, in these states, relative to the state population in the age group 14-17, African American youth are serving life without parole at rates that are, on average, 10 times higher than their white counterparts.[37]

In California, however, African American youth are serving the sentence at a rate that is 18.3 times higher than the rate for white youth. The rate at which Hispanic youth in California serve life without parole is five times that of white youth in the state.[38]

Figure 2

Youth offenders serving life without parole data originally published in Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, The Rest of Their Lives: Life without Parole for Child Offenders in the United States (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2005), http://hrw.org/reports/2005/us1005/; and supplemented by data on under-18 offenders serving life without parole in California provided to Human Rights Watch from California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation in April 2007. Data on under-18 offenders serving life without parole in Mississippi provided to Human Rights Watch from NAACP LDF in October 2007 (report forthcoming). Population data extracted by Human Rights Watch from C. Puzzanchera, T. Finnegan, and W. Kang, Easy Access to Juvenile Populations Online: US Census Population Data, State Population Data with Bridged Race Categories 2004, for ages 14-17, http://www.ojjdp.ncjrs.gov/ojstatbb/ezapop/ (accessed January 2, 2008). Certain states are not included in the above figure because of insufficient data. Ratio calculated using rates per 10,000 population of youth age 14-17 disaggregated by race and state.[39]

Some argue that these differences in sentencing rates are due to differences in involvement in crime.[40] Human Rights Watch sought data on the involvement in crime of youth in the United States disaggregated by race and state for a time period roughly comparable to the sentencing and population data sets we had already compiled. Specifically, we sought data on youths convicted of murder, since murder is the crime that most commonly results in the life without parole sentence for youth offenders.[41] We were unable to find any such data source available in the country. The Federal Bureau of Investigations agreed to produce a special data set for us reporting on these variables for the years 1990-2005. These data on youths arrested for murder form the basis for Human Rights Watch's analysis in this report.[42] An important limitation of the data is that there was no information available for the rate of conviction for those arrested. Calculating the rates of JLWOP based upon rate of arrest rather than conviction may bias the results if there are differential rates of conviction by race.[43]

For the 25 states for which we have data, African American youth are arrested per capita for murder at rates that are six times higher than white youth.[44] We have calculated murder arrest rates per capita for African American and white youth and found that in California for every 10,000 African American youth in the state, 82.69 are arrested for murder. For every 10,000 white youth in the state, 26.36 are arrested for murder. For the 25 states for which we have data, the rate of murder arrests for African American youth is 42.42 per 10,000 youth while the national average for white youth is 6.4 per 10,000. These rates show that twice as manyAfrican Americanyouth andfour timesas many white youth are arrested for murder in California than are arrested on a per capita basis in the 25 states for which we have data.[45]

Figure 3

State |

Black Murder Arrest Rate / Black JLWOP Rate |

White Murder Arrest Rate / White JLWOP Rate |

White Rate of JLWOP per Arrests / Black rate of JLWOP per Arrests |

California |

21.14 |

123.31 |

5.83 |

Delaware |

3.00 |

12.00 |

4.00 |

Colorado |

4.58 |

15.29 |

3.34 |

Arizona |

16.33 |

52.71 |

3.23 |

Georgia |

87.50 |

262.50 |

3.00 |

Connecticut |

22.83 |

47.50 |

2.08 |

N. Carolina |

22.44 |

37.83 |

1.69 |

Illinois |

12.74 |

18.90 |

1.48 |

Pennsylvania |

2.86 |

3.60 |

1.26 |

Nebraska |

4.40 |

5.40 |

1.23 |

Murder arrest data extracted by Human Rights Watch from data provided by the Federal Bureau of Investigations, Uniform Crime Reporting Program: 1990-2005 Arrest by State, (extracted by code for murder crimes, juvenile status, and race) (on file with Human Rights Watch). Population data extracted by Human Rights Watch from C. Puzzanchera, T. Finnegan, and W. Kang, Easy Access to Juvenile Populations Online: US Census Population Data, State Population Data with Bridged Race Categories 2004, for ages 14-17, http://www.ojjdp.ncjrs.gov/ojstatbb/ezapop/ (accessed January 2, 2008). Certain states are not included in the above figure because of insufficient data (see footnote 39, above). Youth offenders serving life without parole data originally published in Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, The Rest of Their Lives: Life without Parole for Child Offenders in the United States (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2005), http://hrw.org/reports/2005/us1005/; and supplemented by data on under-18 offenders serving life without parole in California provided to Human Rights Watch from California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation in April 2007. Data on under-18 offenders serving life without parole in Mississippi provided to Human Rights Watch from NAACP LDF in October 2007 (report forthcoming). Iowa data could not be used for this comparison.

These racial disparities in arrest rates per capita for murder may reflect racial discrimination in the administration of juvenile justice in the United States, or they may reflect differences between African American and white youth criminality.Regardless, once arrested, one would expect that the ratio of the number of African American youths arrested to the number of African American youth sentenced to LWOP would be similar to the ratio of the number of white youth arrested versus the number of white youth sentenced to LWOP. However, we found that in 10 states, with California the most strikingly disproportionate example, that this was not the case (Figure 3).

In California, for every 21.14 African American youth arrested for murder in the state, one is serving a life without parole sentence; whereas for every 123.31 white youth arrested for murder, one is serving life without parole.[46] In other words, African American youth arrested for murder are sentenced to life without parole in California at a rate that is 5.83 times that of white youth arrested for murder. Overall, in the 25 states where data is available, African American youth arrested for murder are sentenced to life without parole at a rate that is 1.56 times that of white youth arrested for murder.

These disparities support the hypothesis that there is something other than the criminality of these two racial groups-something that happens after their arrests for murder, such as unequal treatment by prosecutors, before courts, and by sentencing judges-that causes the disparities between sentencing of African American and white youth to life without parole.

County Sentencing Practices Differ

There is geographic inequity as well: the application of life without parole sentences varies widely among California counties. For example, as Figure 5 shows, although Alameda and Riverside counties have similar juvenile homicide rates, Riverside County has a juvenile life without parole rate nearly three times that of Alameda County. Similarly, while Monterey and Solano counties have comparable juvenile homicide rates, Solano County has four times as many teens serving life without parole sentence as Monterey.[47] In some counties these numbers are so small as to not be statistically significant.

Figure 5

Source: http://stats.doj.ca.gov/cjsc_stats/prof05/index.htm and US Census Bureau 2000 data. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06000.html (accessed October 28, 2007).

Los Angeles is the state's most populous county; in fact, it has more children and youth than any other county in the country.[48] However, population alone does not explain the high number of Los Angeles teens sent to prison with no chance of release. While its population accounts for 28 percent of the state's youth, over 41 percent of all California youth sentenced life without parole are from Los Angeles.[49] African American youth are about 11 percent of the Los Angeles youth population, but represent 37 percent of those sentenced to life without parole. White youth, on the other hand, make up 22 percent of general youth population but represent only eight percent of those from Los Angeles serving life without parole.[50]

Influence of Peers

Common experience and developmental science teach that teens tend to act in concert with and be influenced by others. Youth do things in the presence of peers they would never do alone. The power of peer influence decreases with age, and what an individual at age 16 or 17 will do in a group may be quite different than the choices he or she will make when older. This is significant in the context of sentencing youth to life without parole, where a final decision as to an individual's amenability to rehabilitation is based on the person's actions as a teenager. When those actions were in a group, they may not reflect the individual's potential as he or she matures.

Not surprisingly, youth who commit crimes making them eligible for life without parole are likely to have codefendants. Over 75 percent of those surveyed by Human Rights Watch committed their crimes in groups ranging in size from two to eight individuals. Research shows that peer groups are particularly influential during teen years, as opposed to the more autonomous independent decision-making

characteristic of adults. The susceptibility to peer influence peaks during the early to mid teens-precisely the period during which many of the individuals serving life without parole committed the acts that lead to the life without parole sentence-a phenomenon exacerbated by the fact that adolescents spend less time with parents, more time in groups than adults, and that people in groups generally make riskier decisions than they do alone.[51] "When you're young, you're trying to impress people…your friends," said Eduardo E.[52]

Teens are not only more susceptible to peer influence, they are also much more likely to engage in risky behavior with peers. One study showed that the presence of peers more than doubled the number of risks that teenagers took in a simulated video driving game but had no effect at all on adults.[53] Michael A. reflected on the events leading up to his crime. "A friend was saying he had a problem with some guy. A lot came down to [my] wanting to simply look like a cool guy-like a guy of action who could help him out.It was just a bunch of kids trying to be macho," he concludes now, looking back with the perspective of a 30-year-old.[54]

The likelihood of engaging in risky behavior is further heightened when teens lack structured, supportive institutional and family contexts.[55] While some people we interviewed and surveyed grew up in supportive homes and had strong school and social connections, others described growing up in environments that were troubled. Billy G.'s father died when he was seven years old, leaving his mother alone with seven kids, he told us. She held down two jobs through most of his childhood. Billy describes her as "mainly a monetary figure" while his older brothers played the role of parent. "That obviously didn't work out too well," he noted, dryly commenting on the fact that an older brother became a codefendant in the case that sent Billy to prison for life.[56]

Gangs and gang membership also can be, in part, a peer-driven force. A gang-related murder can result in a special circumstances finding and a presumptive sentence of life without parole under California law.[57] However, when the issue is whether the harshest punishment available under law should be imposed on a teenager on the basis of gang affiliation, there should be an analysis of whether the gang involvement is actually a reliable measurement of a teen's culpability and the

likelihood of future criminal behavior. Some of those interviewed for this report described their gang involvement as an adolescent failing. "I was affiliated with a street gang-I used to do things to impress people, to fit in," said Chris D. of his criminal behavior. As he matured, however, his perspective changed. "Now, you need to fit in to be in my life rather than the other way around…I look back and think-why did I do that?" he told us.[58]Additionally, some of those interviewed said they were drawn to gangs as a substitute for family support. J.R. J. described his attraction to gangs at a very young age, coinciding directly with a period of time in his life when things were falling apart at home and he was placed in foster care. "I was eight or nine, hanging out with a lot of older dudes in a gang. They were my friends, I could count on them to be there for me. Hanging out with them, it was like, I'm cool." He also has a different perspective as someone now in his thirties: "The way I see things now is different-I'm done with that, done with gangs. After all these years, I carry myself differently now…I don't want to live like that any more. I just want to live my life."[59]

Given the reasons why some youth become involved in gangs and the power dynamic between its older and younger members, the penal code'sblanketgang member special circumstance does not account for individual differences and does not necessarily identify the most violent teens.

Adult Codefendants

Respondents to the survey report a high level of adult involvement in their crimes. In nearly 70 percent of cases in which the youth was acting with codefendants, at least one of the codefendants was an adult. According to Human Rights Watch's survey, many juveniles sentenced to life without parole committed their crimes under the influence of, and in some cases, under the direction of, an adult.[60] This high percentage of adult codefendants is an important factor in understanding how juveniles get involved in crimes that result in life without parole. Additionally, adult codefendants tend to get lower sentences than the youth. Age should be a factor in determining culpability, and the influence of adults over young people should be taken into account when assessing a youth's criminal responsibility.

Specific examples abound: juveniles who were the youngest in a group of significantly older adults committing a crime; younger brothers participating in a crime facilitated or encouraged by an older brother or family member; a young gang member trying to impress older ones. For example, Franklin H. told us that while he was 15 at the time of his crime, his three codefendants were 19, 20, and 27 years old. Of his attempt to fit in with that group he said, "I was trying to be cool."[61] Both of Bill K.'s codefendants were adults; he was 16. One codefendant was 12 years older and had sexually abused and beaten Bill. "I was in a forced relationship. Where my codefendant was, I was. [I was] never to leave his side or he would beat the crap out of me." When he told Bill he had to be the lookout for a robbery, Bill said, he did it. "I was afraid of him." The robbery ended with his codefendants killing the robbery victim, and Bill was sentenced to life without parole for his role in the robbery.[62]

A true examination of a teenager's culpability would not be accurate without assessing whether he or she acted under an adult's direction. While no one would suggest that teens are inclined to obey all adults, there can be no question that young people in the settings that give rise to criminal behaviors are vulnerable to adult influence. Yet once a juvenile is sent to be tried in adult court, this factor is not taken into account unless there is a defense that gives rise to the legal standard of duress, a very high bar to reach. Cases proceed, in essence, ignoring the reality of a child or young person under an adult's influence.

Respondents reported that in 56 percent of cases in which there was an adult codefendant, the adult received a lower sentence than the juvenile.[63] For example, Jesus N. was 16 when he and a 20-year-old codefendant committed a murder. Jesus told us that the adult pled to a lesser charge and was sentenced to 11 years. Jesus went to trial and was sentenced to life without parole.[64] J.R. J. was 16 when he participated in a robbery that ended with the victim being killed. J.R. was not the shooter and had several codefendants, including two adults. All were charged under the felony murder rule. Neither adult was sentenced to life without parole, but J.R. and another minor codefendant were sentenced to life without parole.[65]

One very likely explanation for why adults end up with lower sentences than juveniles is that youth may not appreciate the value of plea deals offered. Some told Human Rights Watch they did not grasp the significance of plea deals because they could not fathom the length of the prison term. Others described not understanding concepts like felony murder. Robert D. was offered a plea deal before trial. "When they offered [my codefendant and me] 30 years, a flat 30 years, not 30 to life-we were 17 [years old.] We didn't understand. Thirty years? I was 17 and in 30 years I'd be 47. That seemed like forever to me. We were in juvie hall. We said no."[66] More than a third of youthful offenders responding to Human Rights Watch's survey said they had been offered plea deals but turned them down.[67]

Another possible reason that adults tend to get shorter sentences than juveniles is that adults may be more sophisticated in maneuvering through the criminal justice system. In addition to having a keener idea of when to take a deal, they may be more savvy and able to blame their younger codefendants. One interviewee said he had several adult codefendants, one of whom was more than 10 years older than he. "I thought these older dudes would be my friends, but in the end, they said that I did it all."[68] Another interviewee said, "[In] Asian gang culture-it's always the youngest who takes the blame."[69]

Legal Representation that Compromises Justice

Poor legal assistance afforded to many teen defendants appears to further compromise just outcomes. Some of those Human Rights Watch interviewed or surveyed described a level of legal representation that falls well below professional norms. One of the most salient errors reported to Human Rights Watch is attorneys' failures to adequately represent youthful offenders at the sentencing hearing. In 46 percent of cases respondents reported that their attorney failed to argue for a lower sentence.[70] In addition, in over 65 percent of cases, attorneys failed to inform their young clients that family, community members, and others could testify on their behalf at their sentencing hearing. Nearly 70 percent had no one speak on their behalf at the hearing: not a parent, a teacher who saw some good in a student, a coach who knew another side to a young person's personality, or a friend.[71] "He just threw me to the wolves," said Chris D., of his defense attorney. "I didn't realize [that you could have witnesses at sentencing] until I was talking to other guys [in jail] that were going through the sentencing process."[72]

This is significant because the sentencing hearing is an opportunity for the judge to hear information about the defendant that would not have surfaced at trial. Character, amenability to change, and other mitigating circumstances are relevant at sentencing and help a judge assess whether "good reason" exists to apply a 25-to-life sentence rather than life without parole. Such omissions have particularly egregious consequences for a juvenile defendant facing life without parole, given both the severity of the sentence and the factors in many of these young people's lives that could be the basis for a lower sentence. "On the day of my sentence I was in such a stupor, I don't even know what was said. But what I do remember was an empty courtroom. It had an atmosphere of a funeral. Then again, maybe it was just me," Taylor C. wrote of his sentencing hearing.[73]

The mother of a 17 year old was stunned as she watched her son's case move straight from the verdict to sentencing. "He was found guilty and then right after the jury left, just right that next minute, the judge and attorneys started talking about sentencing," Ms. Murray told us. She had expected her son's attorney to prepare for sentencing and she thought the judge would review information from the case before making the decision. "[The attorney] didn't even ask the judge for more time to get ready for sentencing." Instead, the case proceeded to sentencing and the attorney for her son made no argument for a lesser sentence. "Not even a single argument. He could have said, 'this is a minor, he's never been arrested before…'but [he did not say] a single thing in favor of a different sentence."[74]

The picture is a stark one: many youth tried in an adult court, facing the most severe penalty allowed by law, go through their sentencing hearings alone. Many can not even rely on their attorneys to stand up for them.

It is hard to identify justifiable reasons why an attorney would fail to prepare a strong case at sentencing. An attorney might not argue for a sentence of 25 years to life instead of life with no chance of parole because of poor professional conduct, or ignorance that a lesser sentence is an option under law. Or, an attorney may fail to argue for a lesser sentence because, with life without parole being the presumed sentence, he or she believes there is no chance of winning a lower sentence.

Representing a juvenile facing serious charges is no simple matter for an attorney. Juveniles can be difficult clients who are less able to assist their attorneys by virtue of their lack of experience, developmental stage, and educational level. In addition, studies have shown that many youth involved in the juvenile justice system suffer from learning disabilities and mental health problems.[75] Cyn Yamashiro is the Director of the Center for Juvenile Law and Policy and a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. He says that representing youth is "in many ways, far more complicated than representing adults."[76] Noting that there are the natural developmental and cognitive issues that all youth present, Professor Yamashiro explains that for many youth involved in the criminal system, there are problems that make the role of the attorney more complex. "The majority of these children suffer from learning disabilities, have been physically and psychologically abused, and have at least one diagnosable mental illness."[77]These impairments can make clear communication about complex concepts difficult. Attorneys representing youth must take special care to ensure their clients understand what is happening in the case. "Especially as a kid, you just say 'yes' to everything. I could follow what was going on somewhat, but the law is an alien language. As a kid, you're told what has to happen, and you just do it," said Michael A.[78]

Many interviewees told us that their own participation in their court case was nominal at best. Robert D. remembers, "The law [didn't] make sense to me. I was like, 'It's up to the lawyer, do what you do.'"[79] Almost all of those interviewed said they did not fully understand the proceedings, their role in the process, and the consequences at stake. "I didn't even know I got LWOP until I talked to my lawyer after the hearing," Jeff S. told us.[80] This, too, indicates inadequate legal representation. As Chris D. explained, "Part of it was I was young and didn't know how to express myself. I wasn't able to tell him how I felt. But him being the adult-he should have found a way to communicate with me. He treated me like another statistic."[81]

Finally, in addition to inadequate preparation and communication on the part of attorneys, at least 11 respondents to Human Rights Watch's survey reported that judges explicitly reasoned that they were bound by law to impose the life without parole sentence, when in fact the law would have allowed them to impose a shorter sentence. Robert C. remembers what the judge said at his sentencing: "He said he had no choice but to give me LWOP because the jury found me guilty of first degree murder and by law he has to give me what first degree murder hold[s] (LWOP)."[82] If a judge is confused as to the application of the law, the attorney should provide the court with the correct statement of the law.[83] Other information suggests that attorneys and judges alike are operating under the presumption that life without parole should almost always be imposed on youth convicted of murder with special circumstances in California. These cases further indicate the lack of attention in some courtrooms to the sentencing phase and a dearth of engaged discussion between the attorneys and judges about the law and appropriate sentencing. Judges and lawyers may be confused about the law and, at least in some cases, are not taking the time to figure it out.[84]

|

The Late Teens and Early Twenties: A Dramatic Period for Personal Growth

Human beings change, in dramatic ways, over time. It is a singular theme that resonates through the personal experiences of the individuals Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report and an empirical fact supported by scientific data on human development. It has particularly emphatic implications for young people, as experience and science both confirm change naturally occurs during the years leading up to adulthood. "As a transitional period," reports a study by Temple Professor of Psychology Laurence Steinberg and others, "adolescence is marked by rapid and dramatic [individual] change in the realms of biology, cognition, emotion, and intrapersonal relationships and by equally impressive transformations in the major contexts in which children spend time."[85]

Teens are not adults. Their limited life experience, immaturity, and under-developed psychological and biological constitutions led the US Supreme Court to recognize that youth are not as culpable for their crimes as adults, when it held the death penalty unconstitutional for offenders under age 18: "The case for retribution is not as strong with a minor as with an adult. Retribution is not proportional if the law's most severe penalty is imposed on one whose culpability or blameworthiness is diminished, to a substantial degree, by reason of youth and immaturity."[86]

This is not to say that youth's actions should go unpunished. In fact, not a single one of the individuals serving life without parole for crimes committed as teens suggested that he or she should not be held responsible for his own actions. "We are humans. We make mistakes. We sometimes do really bad things," said Eduardo E. "I'm not trying to say that we shouldn't be punished for what we did."[87]

Additionally, no one interviewed denied the tragedy that their actions have caused. Some interviewees explained that they believe punishment is deserved and expressed evident remorse for actions they can now view through the sobriety of adult eyes. Many who communicated with us pinpointed when they really began to understand the significance of having taken a life. "The human factor, of being involved in taking someone's life. It's hard to put into words, something of that magnitude," said Billy G., now 32, who wept when discussing his involvement in the crime with a Human Rights Watch researcher. He described an awareness growing over a number of years about what he had done. "As a kid, you don't realize how fragile life is or how fragile it becomes."[88] Thirty-three year old Roland T. described the process of beginning to understand what he had done, and his feelings of remorse. "My thoughts about what I had done to them-I've been thinking about the crime, my case, and the victims a lot," he told us. "I didn't realize my situation until I was about 24 or 25 years old. I started thinking about my whole life, what my whole family went through-their pain and suffering. I started waking up. I started regretting… Just me really accepting what I had done to them," said Roland. [89]

Teens' Unique Potential for Change

Recent scientific findings reveal dramatic structural growth in the brain during teen years. These findings, advanced with the use of increasingly sophisticated MRI image analysis, overturns assumptions regarding the completion of brain development at early adolescence.[90] Much of the focus on this relatively new discovery has been on teenagers' limited comprehension and inability to act with adult-like volition. Just as important, however, is the conclusion that teens are still developing. These findings suggest that young offenders may be particularly amenable to change and rehabilitation.

Research has shown that the most dramatic difference between the brains of teens and young adults is the development of the frontal lobe.[91] The frontal lobe is responsible for cognitive processing, such as planning, strategizing, and organizing thoughts and actions. Researchers have determined that one area of the frontal lobe-the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex-is among the latest brain regions to mature, not reaching adult dimensions until a person is in his or her twenties.[92] This part of the brain is linked to "the ability to inhibit impulses, weigh consequences of decisions, prioritize, and strategize."[93] The decision-making process leading up to teen criminal acts is shaped by impulsivity, immaturity, and an under-developed ability to appreciate consequences and resist environmental pressures-attributes characteristic of children and adolescents. Some researchers have further clarified that it is not just a cognitive difference between adolescents and adults, but a complex combination of ability to make good decisions and social and emotional capability that result in a difference of maturity of judgment.[94]

While the precise relationship between brain growth and behavioral change is not yet clear, the malleability of a youth's brain development implies that teens through their twenties may be particularly amenable to change as they grow older and attain adult levels of development.[95] "The reality that juveniles still struggle to define their identity," noted the US Supreme Court in its 2005 Roper v. Simmons decision, "means it is less supportable to conclude that even a heinous crime committed by a juvenile is evidence of irretrievably depraved character. From a moral standpoint, it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult, for a greater possibility exists that a minor's character deficiencies will be reformed."[96]

Furthermore, changes that occur during the teen and early adult years tend to be significantly more dramatic than change during later adult years because of the marked mental, physical, psychological, and emotional growth associated with this period.[97]

In the context of criminal behavior, changes that occur in the late teens and early twenties are significant. For example, compared with adults, risk-taking behaviors for teens can be short-lived.[98] According to Professors Steinberg and Scott, "For most teens, these [risky or illegal] behaviors are fleeting; they cease with maturity as individual identity becomes settled. Only a relatively small proportion of adolescents who experiment in risky or illegal activities develop entrenched patterns of problem behavior that persist into adulthood."[99] These behaviors are for most people part of a temporary, experimental period during which teens generally engage in risky activities such as drug use, unsafe sex, alcohol use, and antisocial behaviors.[100]

No parent of a teenager needs a brain scientist to tell them that teens are likely at times to, for example, fail to consider the consequences of their actions or resist impulses. However, neuroscientific advances help define the significance of these factors. A deeper understanding of adolescent brain development has become increasingly a part of public awareness, with discussions occurring in popular magazines such as Time and Newsweek, newspapers, and on television shows.[101] The far-reaching significance of this information is beginning to permeate different sectors. "Why do most 16 year olds drive like they are missing a part of their brain? Because they are," concludes a full-page ad for Allstate car insurance. "Even bright, mature teenagers do things that are 'stupid'," it continues, with a discussion of the underdeveloped part of a 16-year-old's brain that deals with decision-making, problem-solving, and understanding future consequences.[102]

Personal Experience of Change

In the vast majority of over 130 written and in-person communications with Human Rights Watch, people serving life without parole for crimes committed as youth described themselves as fundamentally different from what they were at the time of their crime-when they were 14, 15, 16, or 17 years old. Many described a major shift in how they viewed themselves, their actions, and their ability to control and manage their emotions. Reflection rather than impulse and an increasing awareness of the consequences of their actions versus present-oriented thinking were typical ways that individuals said they matured during their latter teen years stretching into their early twenties. It could be argued that anyone serving time is likely to claim that he or she has changed. However, these individuals are reflecting on a period in life that is a time of tremendous individual change and growth for most people.[103]

When asked about whether he still remained involved with gangs in prison, Jay C. said, "No, I left everything when I turned 24 or 25. My mind started working for some reason. I started thinking about life."[104] Others marked a changing point in their early to mid-twenties as well. Looking back, they describe how they are different than they were at the time of the crime. For example:

I was a dumb, ignorant kid who was pretty self absorbed. I've become a caring man that understands where I went wrong. Now I find pleasure in helping people. I love my family and would do anything for them.

–Billy G.[105]

As a teenager, you seem at the whim of social pressures and peers and what MTV tells you to do or whoever else. But maturing is learning that you have to listen to yourself.

–Michael A.[106]

I know who I am now. My life is not ruled by my insecurities and childhood fears. I know I can tell someone "no," and it doesn't make me a bad person.

–Reggie Y.[107]

I had no sense of responsibilities or conscience of my actions because I was gangbanging on the streets. Now I am a man who knows right from wrong, who will take responsibility for my actions.

–Cliff D.[108]

I feel I am much different now because I now rationalize and think before I act, as well as consider the pros and cons of everything I do.

-Willis E.[109]

The reality that criminal behaviors are likely to be transient for youth is evidenced by the concrete changes in identity displayed and described by interviewees. Despite the hardship of maturing in prison, individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report have developed into young adults with a settled identity that prioritizes family, education, and self-improvement.

Two people serving life without parole for crimes committed under age 18 interviewed by Human Rights Watch earned placements in an elite prison unit called the Honor Yard-the only one of its kind in the state-reserved for exemplary inmates who have remained completely clear of any disciplinary issues, and have committed to drug-free and violence-free living.[110] Many others we interviewed said they had actively pursued education or self-help programming, had assumed leadership positions in extracurricular activities, or had maintained outstanding disciplinary records. Despite various institutional barriers to participating in prison programs, 70 percent of respondents to our survey said that they have availed themselves of programs such as General Education Development exam (GED) classes and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.[111] Others listed their top interests as reading, writing, and studying.[112] Jay C. described how he spends his time: "I seldom watch T.V. I'm almost always reading something, newspapers, books, magazines."[113] Joseph R. said he had passed his GED exam and had not had an incident on his disciplinary record in years. "My outlook on life has matured. I've educated myself, and I continue to educate myself. My focus is to achieve and achieve."[114]

Ray J., aside from becoming a librarian while in prison, has also been a participant in a program in which inmates counsel and advise troubled teens.[115] Brian C. was engaged in the same program until he was moved to a prison that did not have it.[116] Richard P. told us that prison staff invited him to speak to kids from the outside about how to change their lives in a program called "Changing from Within." Only seven or eight inmates are allowed to participate, he said. He speaks to as many as 20 kids at each session, and he can see that some of them come from the same violent background that he did. "Some listen to me. But if they go through what I did, it's hard to go back to their lives. One kid said he didn't even have school clothes. He ran out of a store [stealing] clothes. I heard that and broke down [crying]." Richard explained that he had renounced gang ties, "dropping out" of the violence and chaos of prison life. "I just want to help somebody," he says. Speaking of the youngsters, his voice caught. "I owe these dudes this."[117]

Chris D., who wrote and performed music before entering prison, said he continues to compose songs.[118] Saul Paul G. said he reads history, draws, and prays.[119] Nick V. has become an ordained Buddhist minister and prison staff trusts him to officiate over Buddhist services.[120]

Several noted that their prison experience, however bad, had helped them change. Brock I. said he had just turned 31 and had been locked up since age 17. "To be honest, I gained perspective on life that would not have happened on the streets. I've become an adult in here. It's crazy how different you think at 31 compared to when I was 21 let alone 17."[121] Several, such as Thomas J., reflected on the pain they had caused in their crimes: "It's been hard. But I also think a lot of the victim's family. I think about how hard it was or is for them, and that makes me stop thinking and crying for myself."[122]

Others we have communicated with have not been as successful in evading the pressures and politics of prison life. "[W]hen I first came to the CDCR, I came with the knowledge that I would be here, literally, forever and chose to make a name for violence, with a belief that many people are abused and mistreated inside prison walls every day but people make a wide path for the convict with a knife in his pocket who isn't afraid to use it," wrote Thomas H.[123] Several interviewees described continued involvement with gangs while in prison and the sense that there was no other choice but to choose violence in such a violent setting. "In some ways I'm better, in other ways I'm worse than I was at 17. We segregate ourselves here. Violence is a way of life in prison," Robert D. told us.[124]

Overall, prisoners who serve a sentence for murder and are released prove to be the least likely of any type of offender to commit new crimes. Following their release, convicted homicide offenders are less than half as likely be convicted of any new crime than released assault, burglary, or drug offenders.[125]

Some suggest that people sentenced as juveniles are different from other prisoners. Chris D. opined, "The majority of kids who come in here are people who got caught up in the streets. They're not bad people. It's a mixture of things that the street throws at you-peer pressure, circumstances, lots of things that a young mind can't conceive."[126]

|

|

Life Inside Prison

Fear and Violence

In California, teens sentenced to life without parole are not placed in adult prisons until they turn 18 years old. When they are transferred to state prison, they serve their time in maximum security prisons among the most violent adult criminals in the state. The majority of individuals serving life without parole for crimes committed as teens told Human Rights Watch that the fear of entering adult prison-especially given the striking physical differences between themselves and the older prisoners-was overwhelming. "I felt like, 'What am I doing in prison with all these grown men?'" Robert C. recalls of entering prison as an 18-year-old.[127] Anthony C. remembers riding in the prison transport van as it pulled up to the prison where he would spend the rest of his life. "I was scared. I was really young. When I first saw the outside of the prison, my stomach was hurting. My stomach started cramping. I had heard all the stories about the violence."[128] David C., now 29, was sent at age 18 to one of California's highest security prisons: "[I was] scared to death. I was all of 5'6", 130 pounds and they sent me to PBSP [Pelican Bay State Prison]. I tried to kill myself because I couldn't stand what the voices in my head was saying…'You're gonna get raped.' 'You won't ever see your family again.'"[129]

David C. was not the only one who said he had tried to kill himself. A number of others told us they had considered or attempted suicide when they entered prison. Yekonya H. wrote, "I felt scared not knowing what would become of me, nor what to expect. I was alone, in desperate need of guidance. I thought about killing myself to escape the pain and frustration I felt, for not being a better child."[130] Several of those interviewed described watching other inmates commit suicide. "Prison life is a lot harder than it's made out to be. Especially when a juvenile is placed in a grown man's prison. There are no friends in prison. It's every man for himself in prison. Many don't make it," Jason E. said.[131]

Small physique and the status of being newly incarcerated heighten the risk of being sexually victimized. At 17, when Billy G. was convicted, he was tiny: "At trial, I was 5'5" and 119, 120 pounds." Upon first entering adult prison, he said, "I was scared, confused, and intimidated."[132]

For many, violence becomes a daily reality. Fifty-nine percent of survey respondents who answered questions about victimization in prison reported that they have been physically or sexually assaulted.[133] "Someone tried to cut my throat with a razor knife," Gary J. told us.[134] Nearly every survey respondent reported witnessing violent acts.[135] Their descriptions make clear that the violence they encounter is not simple fist fights: nearly half reported witnessing stabbings; some described witnessing murders, rapes, strangulations, and severe beatings.[136] "I've seen more death in here than I did when I was living in the inner city," Rudy L. said.[137] Bilal R. wrote, "I have seen stabbings, rapes, robberies, and many other things. I've been stabbed more than once."[138]

Barriers to Rehabilitative Opportunities

For youth in California, a sentence to life without parole has consequences beyond experiencing daily violence. Educational, rehabilitative, vocational, and other self-improvement programs ordinarily available to most inmates are often denied to those serving life without parole, including those sentenced as juveniles. Thirty percent of survey respondents said no programming was available to them at the prison where they were housed. Among those who said programs were available, 47 percent said prison-imposed barriers prevented them from attending. There are several reasons why inmates serving life without parole are denied access to existing programs and work opportunities: inmates with shorter sentences have priority, security classifications not necessarily related to individual behavior make them ineligible, or they must contend with frequent system "lock-downs" that are not the result of their individual behavior.

First, prison practice and regulations give persons sentenced to life without parole the lowest priority for accessing programs. Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that their sentence puts them on the lowest rung of waiting lists for GED classes and substance abuse rehabilitation groups like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), with priority being given to inmates with a set number of years on their sentence. "Those programs are mainly for people that are going home," one individual told us, echoing the conclusion of many.[139] For example, Bill C. was 22 years old when we interviewed him. He said he had been in prison five years and during that time had just one month in a GED class. "I wanted to get my diploma," he told us. "I did everything I could to get into the GED program and I was working hard in the class." But after a month, he said, he was removed from the class and told there was no room for lifers.[140] Ross Meier, the CDCR Facility Captain in the Classification Service Unit, told us that the programs offered vary from prison to prison and availability is limited. "We have 173,000 inmates. There are limited spots in programs."[141] He confirmed that those who will be released from prison are likely to be given priority for certain types of programs.[142]