Crackdown

Repression of the 2007 Popular Protests in Burma

Map of Burma

Map of Rangoon

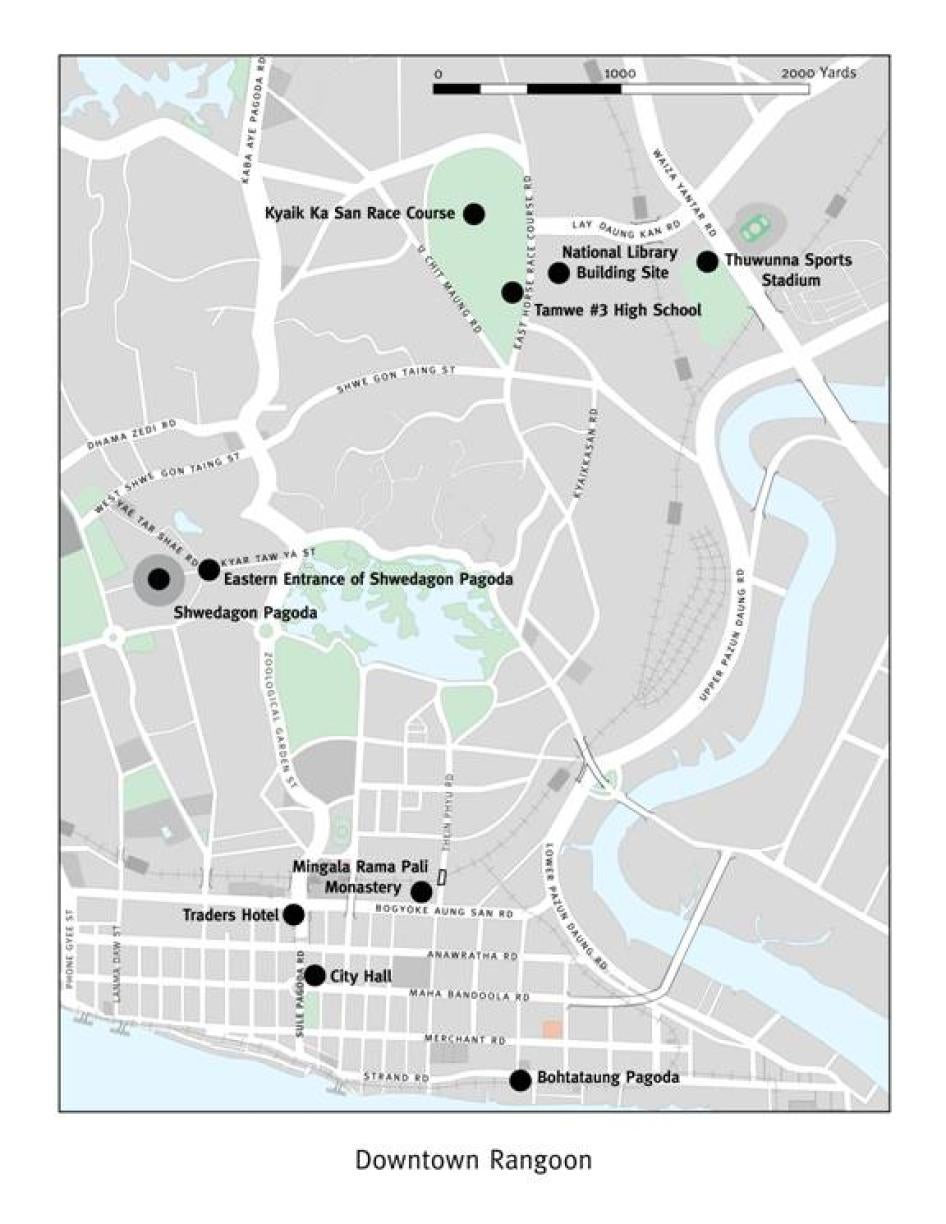

Map of Downtown Rangoon

I. Summary

In August and September 2007, Burmese democracy activists, monks and ordinary people took to the streets of Rangoon and elsewhere to peacefully challenge nearly two decades of dictatorial rule and economic mismanagement by Burma's ruling generals. While opposition to the military government is widespread in Burma, and small acts of resistance are an everyday occurrence, military repression is so systematic that such sentiment rarely is able to burst into public view; the last comparable public uprising was in August 1988. As in 1988, the generals responded this time with a brutal and bloody crackdown, leaving Burma's population once again struggling for a voice.

The government crackdown included baton-charges and beatings of unarmed demonstrators, mass arbitrary arrests, and repeated instances where weapons were fired shoot-to-kill. To remove the monks and nuns from the protests, the security forces raided dozens of Buddhist monasteries during the night, and sought to enforce the defrocking of thousands of monks. Current protest leaders, opposition party members, and activists from the '88 Generation students were tracked down and arrested and continue to be arrested and detained.

The Burmese generals have taken draconian measures to ensure that the world does not learn the true story of the horror of their crackdown. They have kept foreign journalists out of Burma and maintained their complete control over domestic news. Many local journalists were arrested after the crackdown, and the internet and mobile phone networks, used extensively to send information, photos, and videos out of Burma, were temporarily shut down, and have remained tightly controlled since.

Of course, those efforts at censorship were only partially successful, as some enterprising and brave individuals found ways to get mobile phone video footage of the demonstrations and crackdown out of the country and onto the world's television screens. This provided a small window into the violence and repression that the Burmese military government continues to use to hold onto power.

This report, based on more than 100 in-depth interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers with eyewitnesses to the events in Rangoon, offers a detailed account of the protests and the brutal crackdown and mass arrest campaign that followed. It is based on interviews with monks and ordinary citizens who participated in the protests, as well as leading monks, protest organizers and international officials. Our report focuses on the events in Rangoon. It leaves out many deadly incidents and abuses that were reported, but for which - because of government restrictions and the risks involved - we were unable to find eyewitnesses. It is thus not the last word-more investigation is needed to uncover the stories, identify all incidents and victims, and trace the broader consequences of the crackdown.

Despite these limitations, this report provides the most detailed account of the crackdown and its aftermath available to date. The first-hand accounts in this report demonstrate that many more people were killed than the Burmese authorities are willing to admit, and sheds new light on the authorities' systematic, often violent pursuit of monks, students, and other peaceful advocates of reform in the weeks and months after the protests.

***

The protests began in mid-August 2007, triggered in part by an unexpected decision by the ruling State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) to remove subsidies on fuel and natural gas prices, which increased some commodity prices overnight by 500 percent. On August 19, the '88 Generation student movement (which had played a leading role in the 1988 uprising) organized a peaceful march of some 400 protesters in Rangoon. While the immediate issue was the price hikes, the protest and those that were to follow were also a reflection of people's built up anger and behind-the-scenes mobilization by individuals seeking fundamental political reform and an end to the predatory rule of the military-led SPDC.

The reaction of the SPDC was immediate: on August 21 the authorities began arresting most of the leadership of the '88 Generation students and other activist groups, and had more than 100 activists in detention by August 25. In addition, the SPDC mobilized members of its "mass-based" civilian wing, the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA), and its abusive militia, Swan Arr Shin, to monitor the streets of Rangoon to beat and arrest any protesters who dared to continue the demonstrations. Despite the immediate crackdown, protesters continued to gather in Rangoon, and the protests soon spread to other cities throughout Burma.

On September 5, the protests reached a turning point when a group of Buddhist monks holding signs denouncing the price hikes marched in Pakokku, a religious center located close to the city of Mandalay. The monks were cheered on by thousands of protesters. The army intervened brutally, firing gunshots over the heads of the monks and beating monks and bystanders. Unconfirmed reports that one monk died from the beatings, and that others had been tied to a lamppost and publicly beaten, caused revulsion and anger in a deeply religious society. The next day, an angry mob surrounded government and religious affairs officials during a visit to a leading monastery, burning the cars of the government delegation and causing a tense six-hour standoff.

In response to the violence against monks in Pakokku, the newly formed All Burma Monks Alliance (ABMA) demanded an immediate apology from the SPDC, a reduction in prices, the release of all political prisoners including opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, and a dialogue between the SPDC and the political opposition. The ABMA threatened to excommunicate the SPDC leadership from the Buddhist community if it did not meet these demands by September 17. When the SPDC ignored the demands of the ABMA, the ABMA excommunicated the SPDC leaders on September 17 and called for a resumption of the protests. ABMA members began refusing to accept alms from SPDC officials and their families, a symbolically potent act known as "overturning the bowls" (Patta Nikkujjana Kamma).

Monks throughout Burma responded to the ABMA's call and on September 17 began daily marches. Remarkably, the security forces did not directly interfere in the protests for some days, although intelligence officials did photograph and videotape the marchers. It is unclear why the protests were allowed to proceed. The participants grew from the hundreds into the thousands, as an increasing number of monks participated and civilians began to join them.

On September 22, another decisive moment occurred: amidst torrential rain, a group of some 500 monks was allowed to pass through the barricades surrounding Aung San Suu Kyi's home, where she has been held under house arrest for 12 of the past 17 years, and briefly pray with her. This unexpected and unprecedented meeting invigorated the protests.

The next day, an estimated 20,000 protesters, including some 3,000 monks, marched in Rangoon, shouting slogans for the release of political prisoners and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, and for the SPDC to relinquish its hold on power. A day later, September 24, the Rangoon protests exploded in size, to an estimated 150,000 people, including 30,000 to 50,000 monks. Many political groups, including elected parliamentarians of the opposition National League for Democracy who were never allowed to take up their seats after the 1990 elections, as well as the banned All Burma Buddhist Monks Union, joined the marches. Well-known public figures such as the comedian Zargana and the movie star Kyaw Thu publicly offered alms to the marching monks to demonstrate support for their cause. Similar marches took place in 25 cities across Burma.

***

On the evening of September 24, the SPDC signaled it was about to crack down on the protests. The minister of religious affairs appeared on state television to denounce the protests as the work of "internal and external destructionists." The state-controlled Sangha Maha Nayaka committee (a state-controlled committee of senior monks that deals with religious issues) prohibited monks from participating in "secular affairs" or joining "illegal" organizations such as the ABMA. USDA and ward Peace and Development Council (PDC) trucks began circulating the next morning, warning people over loudspeakers not to participate in the protests. Despite the warnings, a similarly large crowd of protesters again appeared on the streets of Rangoon on September 25, the last day of protests before the crackdown.

On the night of September 25, the SPDC announced a nighttime curfew and began arresting some prominent figures who had supported the protesters, like the comedian Zargana. A large number of army troops were moved into Rangoon.

The next morning, September 26, the first serious attacks against the protesters took place when riot police and army troops surrounded and attacked monks at the main Shwedagon Pagoda, severely beating many monks. According to several eyewitnesses, the riot police beat one monk to death. When the protesters moved to the Sule Pagoda, three kilometers away, they were again beaten and dispersed by the riot police and Swan Arr Shin militia, who beat and detained many of the protesters. A separate group of protesters marching downtown were stopped by army troops and Swan Arr Shin militia near the ThakinMyaPark in the western downtown area. Soldiers opened fire directly into the crowd, hitting at least four protesters. As the crowd fled, they were blocked by army troops on Strand Road, where another protester was shot. Other marches continued in downtown Rangoon, creating a chaotic scene. At the end of the day, a one-kilometer-long procession of monks and protesters left the downtown area, showing the public's determination to continue their protests.

During the night of September 26-27, the security forces raided monasteries throughout Rangoon. The most violent raid took place at the Ngwe Kyar Yan Monastery, where the security forces clashed violently with the monks, and detained some 100 monks. Unconfirmed reports claim one monk was killed during the raid.

On the morning of September 27, army troops returned to the Ngwe Kyar Yan Monastery to arrest the remaining monks. They were surrounded by an angry crowd of residents. In the ensuing clashes, at least seven people were killed by the security forces, including a local high school student. Around mid-day, a second clash took place around the Sule Pagoda, as soldiers, riot police, and the Swan Arr Shin dispersed a large crowd of protesters, with the troops shooting first in the air and then directly into the protesters. In scenes beamed around the world, Kenji Nagai, a Japanese video-journalist, was deliberately shot and killed, and eyewitnesses saw another man and a woman also shot and likely killed. The riot police and Swan Arr Shin proceeded to beat and detain large numbers of protesters. At around , another deadly shooting took place, when soldiers shot dead a student holding the "Fighting Peacock" flag of the '88 Generation student movement at the Pansodan overpass.

On September 27, a separate deadly incident took place when army soldiers surrounded marchers in front of Tamwe High School 3, and then drove a military vehicle directly into the crowd, knocking down and killing three protesters. When the soldiers got out of the truck, they opened fire on the fleeing crowd. Several others were killed in the ensuing shooting: soldiers shot in the back and killed a student climbing over the wall of his school and shot down three young men who fled into a neighboring construction site by the National Library. As they tracked down protesters, they fired into a ditch filled with fleeing people, and deliberately shot dead a protester hiding inside an empty water barrel. The security forces then detained hundreds of protesters, beating them before taking them to nearby detention facilities. Human Rights Watch confirmed at least eight civilian deaths at this clash.

Although thousands of people continued to try and organize protests on September 28 and 29, the SPDC managed to retake control of the streets by flooding Rangoon with thousands of troops, riot police, and militia members. The role of the Swan Arr Shin and USDA militias was particularly important, as they allowed the SPDC to patrol every street with abusive militia personnel willing to beat up and detain anyone even attempting to assemble. Security forces continued to fire live ammunition and rubber bullets at protesters who attempted to gather.

***

As the crackdown on the streets proceeded, the security forces also began raiding monasteries in Rangoon and other cities involved in the protests, detaining thousands of monks and frequently physically occupying the monasteries. Detained monks were taken to detention centers, de-robed, and ordered to leave their monasteries for their native villages-monks who escaped detention also were often forced to flee back to their native villages, as their monasteries were occupied. Because the massive arrests of monks, their de-robing, and the occupation of their monasteries, monks virtually vanished from the streets of Rangoon. The raiding and occupation of monasteries continues at the time this report was issued in early December: on November 27, the authorities ordered the closure of the well-known Maggin Monastery, which cared for HIV/AIDS patients. Many monks continue to be held in detention.

Monks were not the only target of the arrest raids. The security forces, relying on the photos and videotapes collected by intelligence agents during the protests immediately began arresting anyone suspected of being involved in the protests. The arrest campaign highlights the SPDCs fear-inducing, totalitarian ability to penetrate the lives of its citizens: using multiple, overlapping networks such as the ward PDC, the USDA, Swan Arr Shin, and the security forces, the SPDC has the capacity to closely monitor and intimidate its citizens, arresting anyone it deems suspect. It has done so systematically since the September protest.

The state-controlled press claims that only 2,836 persons were detained, and only 91 remain in detention, but the actual number of detained persons was much greater, as is the number of those who remain in detention. Most worryingly, the SPDC has failed to account for hundreds of persons who have "disappeared" without trace since the protests, with families unable to confirm if their missing relatives are being detained or have been killed.

The detainees were kept at a variety of ad-hoc detention centers, including the City Hall, Kyaik Ka San Race Course, and the Government Technical Institute, where they faced life-threatening and unsanitary detention conditions. Human Rights Watch documented at least seven deaths in these detention facilities, although the total number is likely to be significantly higher. Detainees underwent basic interrogation, and anyone suspected of being an opposition activist or having been involved in the protests was sent for further interrogation at Insein prison and other facilities. Human Rights Watch documented significant abuse and torture at both the ad-hoc detention facilities and Insein prison: one detainee was hung upside down for long periods of time while being punched; several others were beaten unconscious during interrogations, and were forced to endure "stress positions" and sleep deprivation.

Like the raids on the monasteries, the arrest campaign continues at the time this report was issued in early December, with Human Rights Watch receiving almost daily reports of new arrests. In early November, the authorities arrested U Gambira, the head of the All-Burma Monks Alliance, and charged him with treason. On November 13, the labor rights activist Su Su Nway and her colleague Bo Bo Win Hlaing were arrested in Rangoon, during the visit of UN Human Rights Envoy Paulo Pinheiro. On November 20, a number of ethnic leaders and NLD officials were detained in Rangoon.

***

In the hundreds of thousands, the people of Burma once again showed tremendous courage in standing up to the generals. Their demands have been simple, amounting to basic rights that much of the rest of the world takes for granted: an end to military rule, democratic reform, and the release of political prisoners including opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi. Perhaps most important, they want to live free from the pervasive fear and violence engendered by the repression in Burma. They wish to freely express themselves, assemble and protest without fear of arrest, detention and torture. The generals, clearly shaken by the open defiance of their rule, responded with bloodshed and repression, desperate to return to "business as usual"-which in Burma means dictatorial rule, widespread human rights abuses, and the silencing of any critical voices.

The Burmese government has taken no steps to address the human rights crisis caused by its brutal crackdown on peaceful protest. Unfortunately, this is nothing new. The government has ignored recommendations for reform from friends and critics alike since it annulled elections in 1990.

The international community has responded unevenly. Immediately after the crackdown, the United Nations Security Council dispatched Special Envoy Ibrahim Gambari, held a public hearing, andissued a presidential statement expressing its concern. It could have done more by adopting a resolution with an arms embargo, financial and other sanctions, and demanding specific, concrete steps towards the restoration of civilian rule and the holding of free and fair elections. The United States responded strongly, announcing new sanctions and pressing China, India, Japan, and the Association of Southeast Asia Nations (ASEAN) to also adopt sanctions and put pressure on the SPDC. The European Union also responded with sanctions and strong statements of condemnation, though it is not clear that it will be willing to adopt the kind of financial sanctions that would really matter to Burma's leaders.

While China reportedly pressured Burma to allow Special Envoy Gambari and Special Rapporteur Paulo Pinheiro to visit Burma and for the SPDC to meet with Aung San Suu Kyi, Beijing has recently said that it was opposed to further Security Council activity on Burma. China is widely seen as the protector of the SPDC and therefore part of the problem. ASEAN surprised many with its strong statement of "revulsion" at the time of the crackdown, but it has since closed ranks at its summit in Singapore, even un-inviting Gambari to brief the assembled leaders. India has hardly responded to the crackdown, instead putting its financial interests and its desire to compete with China for influence with the SPDC over its past support peaceful and democratic reform. Another key country, Japan, responded in its traditionally tepid mode. It announced a modest cut in aid, and only then because of public outrage following the killing of a Japanese journalist.

***

It is almost a truism that "change must come from within." Change is what the protesters peacefully sought. Violence and repression is what they received in return. Now is the time for the international community to do its part. In a country increasingly reliant on the outside world for arms, trade, investment, and foreign currency, the international community can play a decisive role in pushing for reform in Burma.

Concerned states and international institutions must stand united in condemning the crackdown, imposing financial sanctions on the government and its leaders, adopting and implementing an arms embargo, demanding an international commission of inquiry to establish exactly what happened during the crackdown, and supporting the call for endingrepression and promoting respect for basic rights in Burma. Fundamental change is needed in Burma, and international unity is required to bring about such change, particularly the support of China, India, Thailand, Japan, Singapore, and other regional actors. Thus far, the signs are not encouraging.

As the most powerful supporter of the regime, China is the key. In January 2007 it protected the generals by vetoing a United Nations Security Council resolution on Burma. It has made it clear that it will block any future resolutions. China should understand the risks associated with such close support for a ruthless dictatorship, particularly in the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

This is a defining moment for the future of Burma, caught in the midst of a wave of repression and arrests, but with the outcome of the struggle for its future still undecided. History will be a harsh judge of countries such as China, India, and Thailand powerful neighbors of Burma who have thus far done little or nothing to stand up for Burma's long-suffering people. So long as China, India, Thailand and others protect the generals, they are likely to be able to ride out the storm at least until the Burmese people rise up again, as they almost certainly will.

(A set of detailed recommendations is set forth at the end of this report.)

II. Crackdown After Crackdown: 45 Years of Military Rule

On March 2, 1962, the Burmese army under General Ne Win staged a coup against the democratically elected government in Rangoon and took control of the country. Within weeks, basic freedoms were severely restricted, with political parties outlawed, public gatherings limited or banned, press freedoms sharply restricted, and internal and international freedom of movement regulated by the Burmese army. Those freedoms have never been regained.

The newly formed Revolutionary Council of military officers opposed all forms of perceived political dissent. Following protests by the Rangoon University Students Union on July 8, 1962 the army shot scores of students and blew up the student union headquarters. Many political activists and journalists were jailed for expressing dissent. As part of its plan to gain legitimacy for continued military rule and economic reform, which even General Ne Win admitted the military was ill-equipped to manage, the Revolutionary Council in 1973 staged a national referendum to adopt a new constitution. The vote was rigged, with official results stating that more than 90 percent had voted in favor. The new constitution reformed Burmese federalism, establishing seven predominantly ethnic Burman "divisions" and seven ethnically distinct "states" that formed the Socialist Union of Burma. This system remains in place today.

Soon after the new constitution was promulgated, major demonstrations erupted in Rangoon in late 1974 as the body of former United Nations Secretary-General U Thant was returned for burial. Students and monks seized his casket, which they argued was being sent to a discreet burial, insulting his stature as a Burmese national and world figure. The army and riot police (lon htein) cracked down on the protesters, taking scores of lives.[1]

The social tensions produced by 26 years of repressive military rule and socialist economic mismanagement came to the surface in March 1988. Following an incident between students and local workers at a tea shop in Rangoon, a group of students demonstrated over perceived abuse of power and corruption by local officials. The reaction by local officials and police was to violently disperse the protesters using the lon htein riot police, who bundled students into a small police van that drove around in the afternoon heat until some 42 died of asphyxiation and heat.[2] The deaths of the students sparked more demonstrations by university students. The authorities closed all universities in Rangoon and ordered the students to return home, but this only emboldened the students. Small demonstrations against the government began to spread throughout towns and cities in government controlled areas.

Ne Win resigned from his position and admitted government failings. But he argued that events since March 1988 had gotten out of hand due to the protesters, and sent them a sinister warning:

Although I said I would retire from politics, we will have to maintain control to prevent the country from falling apart, from disarray, till the future organizations can take full control. In continuing to maintain control, I want the entire nation, the people, to know that if in future there are mob disturbances, if the army shoots, it hits-there is no firing into the air to scare. So, if in future there are such disturbances and if the army is used, let it be known that those creating disturbances will not get off lightly.[3]

Despite these threats, people continued to march in the streets in large numbers. As the government rapidly lost control of the streets, newspapers and political posters were produced and openly distributed. Service personnel from the air force joined the demonstrators.

On August 8, 1988 (commemorated in Burma as 8-8-88), a major nationwide protest took place, with hundreds of thousands of people (some estimate up to one million) marching in Rangoon calling for democracy, elections, and economic reforms. Two days later, as tens of thousands of protesters remained on the streets, army units trucked into Rangoon began shooting at unarmed protesters. At Rangoon GeneralHospital, five doctors and nurses who were helping the wounded were shot and killed by soldiers.[4] The government's authority then effectively collapsed. Much of the daily order of towns and cities was now in the hands of ordinary civilians, with the Buddhist monkhood, the Sangha, playing an important role as marshals of demonstrations to keep them peaceful and avert rioting, looting, and reprisals. At a rally at the Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on August 26, nearly half a million people came to hear speeches by student leaders, former political figures, and Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of independence hero General Aung San. She told the gathering:

At this juncture when the people's strength is almost at its peak we should take extreme care not to oppress the weaker side. That is the kind of evil practice which would cause the people to lose their dignity and honor. The people should demonstrate clearly and distinctly their capacity to forgive. The entire nation's desires and aspirations are very clear. There can be no doubt that everybody wants a multi-party democratic system of government. It is the duty of the present government to bring about such a system as soon as possible.[5]

On September 18, 1988, the army forcibly retook control of the cities and towns. Army chief General Saw Maung declared martial law and the creation of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC, or Na Wa Ta), a collective of senior military officers who would form a "transitional" military government. Through military brutality and a shoot-to-kill policy against the protesters, the SLORC managed to deter further street protests. Estimates of the number killed range from 1,000 to 10,000 deaths nationwide, with 3,000 civilian deaths a commonly accepted figure. Although the army was responsible for the vast majority of the deaths, mobs murdered some suspected military intelligence agents, soldiers, and government bureaucrats.[6]

To gain internal legitimacy and foreign support for its rule, the SLORC rapidly instituted a series of reforms, including changing the English name of the country to "Myanmar" and promulgating an electoral law that permitted political parties to form and organize.[7] The National League for Democracy (NLD), led by Aung San Suu Kyi and retired generals such as U Tin Oo and U Aung Shwe, became the most popular and well-organized throughout the country.

The SLORC announced parliamentary elections for May 1990, but placed severe restrictions on political parties and activists. Suu Kyi's widespread popularity proved to be a major threat to the SLORC, which had embarked on a strategy to discredit the 1988 uprising as instigated by old guard communists, foreign "colonialist" powers, and the Western media.[8] As Suu Kyi's speeches drew large rallies throughout the country, the SLORC sentenced her to house arrest in July 1989 on charges of instigating divisions in the armed forces.

The May 1990 elections were surprisingly free and fair. A total of 13 million valid votes were cast out of nearly 21 million eligible voters. The results of the election were overwhelming for the NLD, which won almost 80 percent of the seats and nearly 60 percent of the vote. The SLORC-created National Unity Party won only 10 seats.

The SLORC was taken by surprise by the magnitude of its defeat and the repudiation of military rule. It scrambled to nullify the NLDs victory, announcing months later that the new members of parliament (MPs) were elected only to form a constituent assembly to draft a new constitution, rather than sit as the elected parliament. This generated more protests and arrests. Dozens of elected MPs went into exile in Thailand and the West.

In 1990, the military brutally crushed a protest by Buddhist monks and nuns in Mandalay, called the patam nikkujjana kamma ("overturning the bowl"), whereby Buddhist monks refused to accept alms from or confer religious rights on SLORC officials and their families. Scores of monks were beaten and killed, hundreds deprived of their monkhood by being "de-robed," and an estimated 3,000 thrown into prison.[9]

Following the reported nervous breakdown and retirement of SLORC head General Saw Maung in 1992, General Than Shwe took control of the SLORC. During the 1990s, the SLORC gravitated between continued repression and limited, often quickly aborted, attempts at economic and political reforms. Basic rights all but disappeared.[10] High schools and universities were often closed for fear of protests. Many teachers and lecturers were forced to attend "refresher courses," which were basically reeducation courses to deter them from deviating from government regulated curriculums.[11] The fear of "MI," the undercover spies and informants of Military Intelligence, controlled by the Secretary Number 1 of the SLORC, Major General Khin Nyunt, was widespread and curtailed the everyday conversation of many Burmese.[12]

Because the "SLORC" had become a synonym for repression and brutality, in 1997 the name of the regime was changed to the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC). The SPDC further consolidated its control through the establishment of so-called mass-based organizations, most notably the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA).

In December 1996, demonstrations by university students in Rangoon were broken up by security forces after a week, and hundreds of students were imprisoned.

International pressure for a political settlement led the government, in 1995, to release Suu Kyi, who in 1991 had won the Nobel Peace Prize. Her unabated popularity led to renewed house arrest in 1997, following violent attacks by USDA thugs on her motorcade in Rangoon. Suu Kyi was again released in 2002, whereupon she and the NLD embarked on a series of rallies around the country that drew crowds of tens of thousands of supporters.

The SPDC organized USDA members to stage anti-NLD demonstrations wherever she made an appearance. On May 30, 2003, an SPDC-organized mob attacked her convoy at Depayin, injuring Suu Kyi and other NLD members. At least four NLD bodyguards were killed. Credible reports suggested that dozens of onlookers were killed in the attack.[13] The government permitted no independent investigation of the attack.

Suu Kyi was then detained at the notorious Insein prison in Rangoon. She was later moved back to house arrest, according to the SPDC, "for her own security." She has remained under house arrest and almost completely cut off from the outside world, only occasionally allowed to meet with anyone other than her jailers.

Long-simmering internal divisions within the SPDC, apparently over power succession, financial interests, and economic and political reform, boiled over when, on October 19, 2004 Than Shwe ordered the arrest of his closest rival, Khin Nyunt, the closing down of his powerful military intelligence apparatus, and the arrest of many of his associates. Khin Nyunt was replaced as prime minister by Lt.-General Soe Win, the man allegedly responsible for orchestrating the attack on Aung San Suu Kyi's motorcade at Depayin in 2003.[14] These events signaled the consolidation of power by the hard-line faction of the SPDC led by Than Shwe and its vice-chairman, General Maung Aye.

The SPDC signaled an even further distancing from the population when it suddenly moved the capital from Rangoon to a jungle redoubt near the central Burma town of Pyinmana in late 2005. The newly constructed capital, called Naypyidaw ("Abode of Kings"), is a vast sprawling complex of new buildings housing all government ministries. Tens of thousands of public servants were forced to relocate to a city with which the International Monetary Fund estimates cost over 2 percent of Burma's gross domestic product (many observers place the cost much higher).[15]

Burma's Economy: Poverty and Price Rises Spark Protests

The August 2007 protests were sparked by massive fuel prices that a desperately poor population simply could not afford. On August 15, the SPDC announced a sudden and dramatic rise in fuel prices by as much as 500 percent. This change led to immediate rises in prices for basic goods, including rice, and made bus travel unaffordable for many poor residents. Although Burma is rich in fossil fuels, precious stones, and hardwood timber, decades of economic mismanagement, vast spending on the military, and corruption have left the majority of the population deeply impoverished. A large portion of Burma's population lives in poverty, and many of those live in extreme poverty, subsisting on less than a dollar a day. A recent household survey conducted by the United Nations found that more than 30 percent of the population lives "well below the poverty line." In 2006 the UNDP Human Development index ranked Burma 132 out of 177 countries in the world. A 2007 UN survey concluded that living standards had declined markedly in the past ten years.

Corruption[16] and the dominant role of the military in Burma's economy have produced a widening gap between a privileged urban elite connected to the military, and the majority of the population, which lives in the countryside, where government health and education services are virtually non-existent and there are few alternative employment opportunities beyond agriculture. Conditions have also worsened for ordinary urban residents, as they confront rising inflation, high unemployment, frequent power outages, a collapsing sanitation infrastructure, and deteriorating roads and other public infrastructure.

The SPDC spends a significant proportion of Burma's resources to maintain its enormous army and engages in profligate spending on unproductive projects such as the relocation of the capital, yet has some of the lowest social spending of any country in the world. Inadequate nutrition is the fifth leading cause of infant deaths in Burma. Burma is the only country in the world where beri beri, a vitamin deficiency affliction, is a major cause of infant mortality. A recent UN statement summed up the plight of the population, finding that "in this potentially prosperous country, basic needs are not being met":

Today, [Burma]'s estimated per capita GDP is less than half that of Cambodia or Bangladesh. The average household is forced to spend almost three quarters of its budget on food. One in three children under five are suffering from malnutrition, and less than 50 percent of children are able to complete their primary education. It is estimated that close to seven hundred thousand people suffer from malaria and one hundred and thirty thousand from tuberculosis. Among those infected with HIV, an estimated sixty thousand people needing anti-retrovirals do not yet have access to this life-saving treatment.[17]

Healthcare in Burma has suffered as a direct result of military rule. Epidemics of HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis have exacerbated serious health challenges in the country. Restrictions on grassroots health activists and even private health clinics and services by the authorities are commonplace, as the SPDC tries to control even small-scale health initiatives. Healthcare in ethnic conflict areas is even more dire, where death and injury by war, disease, poverty, and poor nutrition is an everyday reality. A 2006 study by mobile health clinics in eastern Burma found that one in four children die before they are five-years old.

The Burmese economy is stifled by an unwieldy dual exchange rate for the national currency, the kyat. The official rate is 6 kyat per US dollar, while the market rate fluctuates between 1,000- 1,400. Widespread poverty has been exacerbated by disastrous economic policies, such as the 1987 demonetization in which currency notes of 25, 35, and 75 were summarily withdrawn and replaced with notes of 15, 45, and 90 (the last two of which were apparently chosen by Ne Win because of his affinity for the astrological auspiciousness of the number nine).

III. Price Hikes, Peaceful Protests, and the Initial Reaction of the Authorities

On August 15, 2007 the Burmese government unexpectedly removed most subsidies on fuel and natural gas prices, causing rapid and dramatic increases in the prices of fuel, diesel, and natural gas, as well as basic commodities. Natural gas prices increased overnight by as much as 500 percent, and fuel and diesel costs doubled. The rise in fuel prices had a knock-on effect throughout the population, as already impoverished persons struggled to meet the increased costs of transport and basic goods.

"Su Su Hlaing," a tea shop owner from Rangoon, explained to Human Rights Watch how her business was affected:

The tea shop business went bad because of the price increases. The milk and charcoal prices rose. People couldn't afford to buy at the tea shop because the prices were higher. So, there was not much profit for my familybefore the fuel prices, the cost of [food delivery] was 200 kyat. After the price increase, it was 400 kyat for the serviceas for our daily earnings, before we used to sell 70,000 kyat a day, which gave us a profit of 5,000 kyat. After, we would sell 50,000 kyat a day, which gave us a profit of 1500-2000 kyat a day. And this is [the income] for the whole family.[18]

On August 19, an estimated 400 to 500 people, including prominent leaders of the '88 Generation student movement, gathered for a march in Tamwe Township of Rangoon to protest the fuel price increases. "Htet Zin Moe," a shopkeeper who had joined that protest told Human Rights Watch:

On August 19, I went to Tamwe to [buy shop supplies]. While I was there, I saw the demonstration led by ['88 Generation leader] Min Ko Naing asking the government to reduce the fuel price. At that time, I supported the demonstration. I was shouting as I was walking with them, explaining why I was marching. I joined at , for about 20 minutes. There were no USDA or Swan Arr Shin [militia] giving the people any trouble.[19]

Earlier in the year there had been a number of small protests, including a February 22 protest in Rangoon against poor economic conditions that led to the arrests of nine people who were released a week later,[20] a follow-up protest by the same group of activists in Rangoon on April 22, 2007, that led to the arrest of eight people,[21] and a one-person protest on June 19, 2007 (the birthday of Aung San Suu Kyi) in Taungkok township, Arakan state, against inflation. But the August 19 protest was the largest public demonstration in Burma in years.

The government responded on August 21 by arresting prominent activists, targeting most of the leadership of the '88 Generation student movement, including Min Ko Naing,[22] Ko Ko Gyi,[23] Min Zeya, Ko Jimmy, Ko Pyone Cho, Arnt Bwe Kyaw, and Ko Mya Aye.[24]The government arrested people on a daily basis in its efforts to halt the protests: by August 25, more than 100 people had been detained, including many officials of the NLD, the former chair of the Labor Solidarity Organization, the chair of the Human Rights Defenders and Promoters group, other political activists (most of them former political prisoners), members of the Myanmar Development Committee, and ordinary protesters.[25] The detentions of the '88 Generation student leaders were publicly announced in the state-controlled New Light of Myanmar newspaper, which claimed that "their agitation to cause civil unrest was aimed at undermining peace and security of the State and disrupting the ongoing National Convention," and listed criminal charges that could result in long prison sentences.[26]

As soon as the demonstrations began, the protesters in the street faced harassment from pro-government elements that threatened and at times physically attacked them. These included the SPDC-organized Union Solidarity Development Association(USDA) and the Swan Arr Shin ("Masters of Force") militia.[27](The USDA and Swan Arr Shinn militia are discussed in detail in chapter VIII).

According to press and eyewitness accounts, when a second protest of some 100 people was organized on August 22, "armed police took up positions across [Rangoon] alongside truckloads of men from the army's Union Solidarity and Development Association [who] were carrying brooms and shovels, pretending to be road sweepers."[28]Some of the protesters were physically assaulted by the USDA members. The police present did not intervene to stop the assaults, although they did arrest some of the protesters afterwards.[29]

On August 23, security forces and militia members detained a group of 30 protesters who were walking "quietly without placards" to the offices of the National League for Democracy, manhandling them into waiting civilian trucks. The same day, U Ohn Than, 61, a former political prisoner, held a solitary protest in front of the US embassy, holding up placards and shouting slogans for about ten minutes before being detained by the security forces.[30]

On August 24, militia members broke up a protest near the City Hall in Rangoon, beating and detaining some 20 protesters.[31]

On August 28, 2007, some 50 persons led by the veteran labor organizer Su Su Nway[32]shouted "Lower fuel prices! Lower commodity prices!" at the Hledan traffic circle in Rangoon. Militia and uniformed security members assaulted the protesters and detained at least twenty protesters, mostly members of the NLD.[33] Su Su Nway herself escaped arrest by jumping into a taxi, but was detained on November 13, 2007, as she and colleagues were putting up protest leaflets near the hotel where UN Human Rights Envoy Paulo Pinheiro was staying at the time.[34]

By September 1, 2007, continuing arrests and attacks on protesters by the militias posed a significant challenge to protest organizers in Rangoon. Most of the activists responsible for organizing protests in Rangoon had either been arrested or were now in hiding to avoid arrest, as security forces had distributed the names and photographs of wanted activists to hotels and neighborhood officials.[35]However, small protests were now also being staged in other cities including Sittwe, Meiiktila, Taunggok, and Mandalay.[36]

On September 3, the Burmese authorities announced the completion of the 14-year-long National Convention to draft a new constitution. The Burmese authorities used the convention's completion as a weapon against the protesters, suggesting that the protesters sought to disrupt Burma's "roadmap to democracy."

The same day, authorities immediately detained protesters who planned to march 260 kilometers from Laputta to Rangoon, and a brief 15-person protest was held in Kyaukse, the hometown of Burma's military leader, Senior General Than Shwe.[37]

IV. The Monks Join the Protests

Although sweeping arrests and the attacks by USDA and Swan Arr Shin thugs had effectively contained protests in Rangoon by early September, the movement gained momentum in other parts of Burma, seemingly taking the government by surprise. On September 4, a group of 15 NLD members marched in Taunggok to demand the release of Se Thu and Than Lwin, two NLD members detained at a two-person protest on August 31, and were soon joined by a crowd of up to a thousand local residents.[38]The same day, the Burmese authorities arrested Mya Mya San, an NLD member who had led a regular prayer vigil for the release of detained NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi at Rangoon's Shwedagon Pagoda, dispersing the 15 NLD activists who had joined the prayer vigil.[39]

On September 5, NLD officials organized a protest rally in the Irrawaddy Delta town of Bogale, giving speeches to a crowd reportedly numbering in the hundreds for several hours before the authorities broke up the crowd and arrested Aung Khin Bo, the NLD's township chairman, who had organized the rally.[40]

Although the protests prior to September 5 were a significant event in Burma's history-they were the first sustained protests against military rule since the bloody crackdown on the August 1988 protests that left more than 3,000 people dead-a turning point occurred on September 5, when several hundred Buddhist monks marched down the streets of Pakokku, a religious center located close to the city of Mandalay.[41] The monks reportedly held placards denouncing the price hikes, and were cheered on by thousands of residents lining the streets.[42]The decision of the monks to join the protests was of deep significance, as monks have a unique moral standing in Burma and have since colonial times been at the core of political uprisings.[43]

The army intervened in the protests for the first time. After firing at least a dozen warning shots over the heads of the marching monks, the army reacted brutally, beating the monks and the bystanders with bamboo sticks.[44]USDA and Swan Arr Shin militias joined in the crackdown, beating and apprehending monks and civilians. Rumors circulated, still unconfirmed, that one monk died from a beating received at the protest, and that several monks had been tied to a lamp post and publicly beaten.[45] The army's abuse of revered monks in their initial appearance at protests caused revulsion and anger throughout the country.

The following day, September 6, a government delegation including the chairman of the Pakokku Peace and Development Council and a representative of Magwe's religious affairs division visited the main Maha Visutarama Monastery, reportedly to apologize to the abbot for the violence of the previous day and to request that he order his monks to stop taking part in protests.[46] The monastery was quickly surrounded by a crowd of angry monks and civilians numbering around a thousand, who proceeded to burn four cars of the government delegation, prevented the officials inside the monastery from leaving, and demanded the release of detained monks.[47]After a tense six-hour standoff, the officials managed to leave the monastery through a backdoor exit.[48]

The monk protests in Pakokku were denounced on state-controlled television. Monks were blamed for inciting violence as state television said that attempts to incite violence would not be tolerated and that the people of Burma "would not resort to violent means and will never accept attempts to incite unrest like the '88 uprising."[49]

In response to the violence against monks in Pakokku, a new organization calling itself the All Burma Monks Alliance[50] issued a statement on September 9, 2007, giving the SPDC until September 17 to comply with four demands or face a religious boycott: 1) an apology by the SPDC to the monks for the Pakokku violence; 2) an immediate reduction in commodity prices including fuel, rice, and cooking oil prices; 3) the release of all political prisoners including Aung San Suu Kyi and those detained during the current protests; and 4) an immediate dialogue with the "democratic forces" in order "to resolve the crises and difficulties facing and suffering by the people."[51] The deadline of September 17 was symbolic, as September 18 is the anniversary of the date the 1988 pro-democracy movement was decisively crushed and current military rule was established under the State Law and Order Restoration Committee, SLORC (later renamed SPDC).

The SPDC did not meet the demands of the monks. Instead, it tried to buy the loyalty of individual monasteries with financial gifts that the monks largely refused.[52]The SPDC continued with its crackdown on the protests and vilification of the opposition. On September 9, the state New Light of Myanmar newspaper charged that "internal and external pessimists and opposition groups are striving to create riots and internal disturbances" with the aim "to gain power by a short cut," and accused the protest organizers of planning terrorist attacks and undergoing training, sponsored by an unnamed US organization, in bomb-making.[53]The SPDC also deactivated the landlines and mobile phone service of key activists, journalists, and at the NLD headquarters.[54]

On September 10, a military tribunal at Insein prison sentenced six labor activists to sentences of 20 to 28 years in prison for attempting to attend a May Day talk on labor rights at the AmericanCenter in Rangoon.[55] In an apparent attempt to counteract the protest movement, the SPDC began organizing nationwide "mass rallies" to welcome the completion of the National Convention, with mandatory attendance required from the local population.

"Overturning of the Bowls": The Monks' Decision to Boycott the SPDC

After the SPDC refused to meet the four demands of the All Burma Monks Alliance (ABMA), the ABMA released a second statement on September 14 announcing that all monks would refuse to accept alms from SPDC officials and their supporters through a religious excommunication known as Patta Nikkujjana Kamma,[56] or the overturning of the alms bowls. The statement claimed that senior abbots supported the ABMA's boycott, and called for the resumption of peaceful protests by the monks on September 18.[57]

The decision to formally invoke a Patta Nikkujjana Kamma religious boycott against the SPDC and its supporters and family members was a powerful gesture against the predominantly Buddhist SPDC leadership. In Buddhism, the giving and receiving of alms is a fundamental expression of religious piety, and considered among the most meritorious of acts. Buddhist religious life in Burma centers around gaining "merit" through ones' actions, so the boycott effectively denied the SPDC and its supporters the ability to gain merit from the elements of the Buddhist community that supported the boycott (although the SPDC leadership could continue to count on the support of government-allied Buddhist abbots and their monasteries).

The boycott also affected the political legitimacy claimed by the SPDC and its supporters as devout Buddhists, a blow to the leadership. Since coming to power, the SPDC generals had sought to cultivate an image of themselves as protectors of the Sangha, conducting frequent public "merit-making" ceremonies at which they handed over gifts to monasteries, launching well-publicized pagoda restoration projects (including the Shwedagon in 1999), touring the country with a Buddha tooth relic borrowed from China, and holding a World Buddhist Congress in Burma.[58]The ABMA's boycott call was a blatant challenge to the SPDC's carefully cultivated image as protectors of the Sangha and their right to rule a Buddhist nation, an open act of defiance rarely seen in Burma.

A September 21 statement by the ABMA went even further, denouncing "the evil military dictatorship" as the "common enemy of all our citizens" and vowing to "banish the common enemy evil regime from Burmese soil forever."[59]

The monks knew the risks involved in boycotting the SPDC through Patta Nikkujjana Kamma. In 1990, the Sangha in Mandalay similarly decided to boycott the ruling SLORC under Senior General Saw Maung, refusing to accept alms from the government or attend state functions. The SLORC responded by issuing two orders on October 20, 1990: the first (Order 6/90) dissolved "illegal" monk organizations and unions, while the second (Order 7/90) declared that any monk who took part in non-religious activities would be expelled from the Sangha and prosecuted. The following day, the security forces raided at least 130 monasteries in Mandalay alone, and hundreds of monks were de-robed and arrested. Senior monks were sentenced to long prison terms for their actions, including Thu Mingala, one of Burma's greatest authorities on Buddhist literature, who was sentenced to eight years in prison. In the aftermath of the 1990 crackdown, the SLORC tried to reorganize the Sangha community into a pro-SLORC organization, with limited success.[60]

The Monks March in Rangoon

On September 14, the ABMA announced that "the SPDC leaders failed to reply" to their demands and said they would go ahead with their threatened action to excommunicate the SPDC leaders and refuse alms from them beginning on September 17. Monks and novices throughout Burma responded in large numbers to the ABMA's call to relaunch the protests.

September 17

Monasteries throughout Burma responded to the call by the ABMA to restart the protests on the expiry of the September 17 ultimatum issued to the SPDC. On September 17, a group of several hundred monks demonstrated peacefully in Chauk township, Magwe division, for about two hours, reciting traditional paritta sutta prayers for protection against evil. Similarly, in Kyaukpandaung, Mandalay division, several hundred monks recited metta sutta (loving kindness) prayers while walking in procession. The government apparently allowed both protests to occur without direct interference.[61]

September 18

At about , a group of 300 monks gathered at the southern stairway of the Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon. The entrance of the pagoda was blocked by a cordon of men in civilian clothes who refused to let the monks enter, thus preventing them from carrying out religious ceremonies inside the pagoda.

According to an eyewitness account provided to Human Rights Watch, the monks then walked down to Sule Pagoda. At this stage, security forces did not intervene with the protesters, and traffic police even stopped traffic as they crossed the main roads. Hundreds of civilians followed the monk parade along the sidewalks. After reaching Sule pagoda, the monks continued to Bohtataung Pagoda, where they sat down in front of the pagoda and prayed for 10 minutes. The monks then stood and applauded, and the estimated thousand onlookers who had gathered applauded back. The monks then walked away from the pagoda and dispersed at about , going back to their respective monasteries in buses. No uniformed security forces attempted to interfere with the march, although plainclothes militia members and military intelligence officials openly photographed and videotaped the protest.[62]

According to several sources, the excommunicative boycott decree, presumably composed by the ABMA, was recited at a number of monasteries and religious sites on September 18, bringing the religious decree into effect. A translation of the excommunication decree states:

Reverend Fathers, may you lend your ears to me! The evil, sadistic, and pitiless military rulers who are robbing the nation's finances and indeed are large-scale thieves have murdered a monk in the City of Pakokku. They also apprehended the reverend monks by lassoing. They beat up and tortured, swore at, and terrorized the monks. Provided that monks be bestowed with four deserving attributes, they ought to boycott the evil, sadistic, pitiless, and immensely thieving military rulers. The monks ought not to associate with the tyrants, not to accept four material things donated by them, and not to preach to them. This much is informing, recommending, or proposing.

Reverend Fathers, may you lend your ears to me! The evil, sadistic, and pitiless military rulers who are robbing the nation's finances and indeed are large-scale thieves have murdered a monk in the City of Pakokku. They also apprehended the revered monks by lassoing. They beat up and tortured, swore at, and terrorized the monks. Provided that monks be bestowed with four deserving attributes, they ought to boycott the evil, sadistic, pitiless, and immensely thieving military rulers. The monks ought not to associate with the tyrants, not to accept four material things donated by them and not to preach to them. If the reverend consent to boycotting the military despots, disassociating from them, rejecting their donations of four material things, and abstaining from preaching to them, please keep the silence, and [if] not, please voice objections [now], Fathers

[Silence follows, signifying consent]

The clergy boycotts the evil, sadistic, pitiless, and immensely thieving military rulers! Excommunication together with rejection of their donations of four material things[63]and abstaining of preaching to them has come into effect![64]

According to press reports, about a thousand monks also held a peaceful march in the city of Pegu, located 80 kilometers north of Rangoon.[65]

In the coastal city of Sittwe, about 400 monks protested with signs asking for the prices of commodities to be reduced and wishing for loving kindness (a traditional Buddhist prayer). The monks were allowed to march freely throughout Sittwe and were followed and greeted by lay people who applauded and paid respect to the monks. The district PDC chairman asked the monk who heads the township Sangha Nayaka to warn the protesting monks not to use violence and to protest peacefully.By evening, the number of the monks had increased and over 10,000 people had gathered to join the protests. When the monks reached the area where the Rakhine State General Administration Office, City Hall, and USDA offices are located, they demanded that the authorities release the two men who had been arrested on August 28. Some within the crowd threw stones at the police. Although the monks and police urged the lay people to go home peacefully, police shot tear gas canisters into the crowd. Clashes ensued and protesters and government officials were injured, including two officials from the Rakhine State Peace and Development Council, who were hospitalized. Several monks were detained.[66]One of the detained monks, U Warathami, later told the Democratic Voice of Burma that was army troops kicked him with their boots at the protest, that police then took him to the Sittwe police station where he was beaten unconscious, and that, long after the protest had ended, he was dropped off at his Dhammathukha Monastery.[67]

September 19

Amid heavy monsoon rains, about 150 monks gathered again at Shwedagon Pagoda, and were again prevented from entering the pagoda by a cordon of plainclothes men.The monks first walked through TamweTownship, and then turned towards the Sule Pagoda at about 2:30 p.m., by which time they had grown in strength to about 250 monks and a growing number of civilians walking closely alongside them, unlike the previous day when most civilians had kept their distance by staying on the sidewalk. "Maung Maung Htun," a 43-year-old shopkeeper who walked with the monks that day, recalled his decision to join the monks on their march:

On September 19, I went to see the demonstrations. I offered water to the monks. Then, I marched, protecting the monks who were walking to Sule Pagoda. When we arrived at the Traders hotel, I went back to my shop. It was about when I began to join the march, and marched with them for an hour and a half...I went to join because I wanted to know the real situation for myself. I didn't want to just hear about it from other people. I wanted to see it with my own eyes.[68]

Uniformed security forces were absent from the area, but plainclothes officers videotaped the march, as on the previous day.[69]According to press accounts, the monks briefly moved aside the security gates at the Sule Pagoda, and entered the pagoda to pray inside, before peacefully dispersing around 4 p.m.[70]Separate smaller protests also happened in Ahlone, a western suburb of Rangoon, where about 100 monks marched, and South Okkalapa, a northern suburb of Rangoon, where a similar march occurred, both without reported violence.[71]

More than a thousand monks staged a peaceful protest in the religious center of Mandalay, again without incident. In Prome, some five hundred monks reportedly held a peaceful march.[72] In Sittwe, the site of violent clashes the previous day, thousands of monks marched again, and again demanded the release of the two men arrested on August 28. Government officials promised to release the two detainees from Thandwe prison and return them to Sittwe within three days.[73]

September 20

Unlike the previous two days, when monks gathered at Shwedagon Pagoda at about 1 p.m. on September 20, no one prevented them from entering the pagoda, so the monks began their daily march by entering and praying there. The group of monks, now grown to about 400 to 500, then marched again to Sule Pagoda, where they were joined by a similar number of civilians who marched alongside them and joined hands to form a cordon around the marching monks. Others lined the streets and clapped in support of the marching monks. Uniformed traffic police facilitated the march by stopping traffic at major crossings, and plainclothes intelligence officers again videotaped the march, but did not interfere.[74]

It remains unclear why the authorities allowed the monk protests to proceed virtually without interference for the first few days following the announcement of the religious boycott of the SPDC. It is possible that the SPDC was taken by surprise, and was reluctant to use violence against Burma's revered monks, following the massive reaction to the earlier use of violence against monks in Pakokku on September 5 (see above). Perhaps the SPDC wanted to see if the monk protests would naturally disappear after a few days, although the opposite happened: as ordinary people saw the monks march in the streets without interference, they soon joined them in massive numbers.

At Sule Pagoda, the monks marching from Shwedagon Pagoda were met by a separate group of marching monks and civilian supporters, bringing the total number of monks marching in Rangoon that day to an estimated 1,300, supported by a larger number of civilians. A monk walking at the head of the protesters held up an overturned alms bowl, signaling the announced religious boycott of the SPDC.[75] A neighborhood official confirmed to an international journalist that instructions had been issued by the authorities not to interfere with the protesting monks, saying "We have been instructed to be patient and to even protect the monks."[76]

According to opposition news reports, hundreds of monks also staged a march in Monywa, Sagaing Division (north of Mandalay), and in Pakokku without interference from the authorities.[77]

September 21

As on previous days, some 800 monks gathered at about at Shwedagon Pagoda and marched a different route through Rangoon, ending up again at Sule Pagoda at around They were joined by hundreds of civilian supporters, despite torrential rains that caused substantial flooding in Rangoon that day. There was no interference by the authorities with the march.[78] "U Theika," a monk who participated, told Human Rights Watch of the determination of the monks to continue despite the bad weather:

On those days [September 20 and 21], the weather was bad, it was constantly raining. In some places, we were walking up to our knees in water. Our robes were wet, and we didn't have slippers or umbrellas. Every day, more students came to walk with us monks, linking their arms and walking alongside us. Even though it was raining, more people came to watch us day by day.[79] The monks [told the people], "If you want to join us, you can follow the monks, but no shouting and you can't just do what you want. If you walk peacefully, you are welcome to join us."[80]

The NLD and Student Groups Rejoin the Protests

September 22 saw one of the most important and decisive events of the protests. A group of 500 monks marching down the streets of Rangoon was allowed to pass through the barriers around the house where NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi has been held under house arrest for 12 of the last 17 years. As the monks approached the house, Suu Kyi was allowed to open the steel gate of her courtyard, and greet the monks from behind a cordon of police guards with riot shields. The monks shouted Buddhist prayers for Suu Kyi, who was in tears, according to eyewitnesses. The picture of Suu Kyi was beamed around the world.

Burma's opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, pays obeisance to monks chanting prayers in front of her residence in Rangoon on September 22, 2007. 2007 Reuters

The sight of Suu Kyi invigorated the protesters: this was the first time in four years that she had been seen in public, and suddenly a stronger political dimension had been added to the protests. Some thought that change was finally within the realm of the possible.[81]"U Pauk," a 30-year-old monk who was present at the meeting described to Human Rights Watch what happened that day, and the significance of the meeting:

We arrived at her house at about There were only a few riot police there on that day. The riot police asked the monks not to go down, but the monks who were at the front holding the [Buddhist] flags spoke to them, and they allowed us to go.

We began to pray the metta sutta (loving kidness) and after a few minutes Daw Aung San Suu Kyi came out. She opened the gate, or someone opened the gate for her, but she didn't speak. There was a large distance between her and the monks with riot police in between.

We got strength from her, and she got strength from us. My feeling when I saw Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is that my tiredness from walking disappeared. We thought our efforts would be blessed, because we saw this person who sacrificed her life for all of us. After [being placed again under house arrest in] 2003, she was not allowed to see anyone, she has been lonely for so long and that was the first time for her to meet the people.[82]

The next day, September 23, the protests in Rangoon swelled to an estimated 20,000 protesters, including at least 3,000 monks, the largest anti-government demonstration seen in Burma since the bloody crackdown of 1988.[83] The protesters included many ordinary citizens, such as mothers with their children, with monks in the center surrounded by a cordon of civilian supporters. The monks and their supporters walked from Shwedagon Pagoda to Sule Pagoda, and then passed the old US embassy in downtown Rangoon. The protests took on an even more political tone, with monks and their civilian supporters shouting slogans calling for the release of Suu Kyi, in addition to their previous excommunication of the SPDC and their demands that the SPDC relinquish power.[84] Security forces armed with shotguns appeared along the route of the protest for the first time since the monks started marching. Together with militia forces, they prevented the monks and protesters from returning to Suu Kyi's home.[85]

By September 24, an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 monks joined by an equal number of civilians marched in Rangoon, cheered on by large crowds clapping and shouting encouragement from the sidewalks.[86]The protesters walked almost the entire day, gaining supporters as the day went on. By , the procession, moving at a brisk pace, took some thirty minutes to pass. Members of banned political groups now marched on their own in the protests. A group of about 150 NLD members walked between two groups of monks holding NLD flags. One group of monks walked under the banner of the All Burma Buddhist Monks Union, an organization banned after the 1990 crackdown on the monks. Another group walked under the Elected Parliamentarians Group banner, representing the NLD members of parliament elected in the annulled 1990 elections. Large groups of Buddhist nuns also joined the protests for the first time.[87] The civilian protesters again shouted openly political slogans such as "Free Aung San Suu Kyi!" and "Free all political prisoners!" That morning, before the monks set out on their protests from Shwedagon Pagoda, well-known public figures including the comedian Zagarna and the movie star Kyaw Thu publicly offered alms to the monks in open support for the protests.[88] Similar large-scale protests reportedly took place in at least 25 cities and towns across Burma on September 24, with particularly large protests in Mandalay and Sittwe.[89]

V. The Crackdown

The Government Acts to End the Protests

On the evening of September 24, the government responded for the first time to the rising tide of protests. Appearing on the state-controlled MRTV television channel, the minister for religious affairs, Brigadier-General Thura Myint Maung, denounced the protests as being the work of "internal and external destructionists, who are jealous of national development and stability."[90] The government-controlled State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, promoted by the government as the supreme authority on Buddhist affairs, issued Directive 93, ordering all Sangha Nayaka committees at the state, divisional, township, and ward level to "supervise the Buddhist monks and novices so that they practice only Pariyatti [study of Buddhist teachings] and Patipatti [engagement in Buddhist practices, including meditation]," and prohibiting monks from participation in "secular affairs"-in other words, a direct religious ban on the participation of the monks and novices in the protests. Monks and novices were also banned from joining "illegal" organizations of monks, such as the non-sanctioned All Burma Monks Association.[91]

Although the religious affairs minister's statement did not refer to any specific legal regulations, Burma has various laws and regulations that have long been used to prosecute protesters, however peaceful, and impose long prison sentences. A foreign observer noted large groups of riot police deploying around University Avenue in Rangoon in the evening, after the protesters had already dispersed for the day.[92]

The Last Day of Peaceful Protests: September 25

On the morning of September 25, the televised warnings not to participate in further protests were re-broadcast. At , trucks with loudspeakers began circling the streets of Rangoon, warning the population not to engage in further protests, noting Burma's laws against unlawful assembly, and warning that demonstrators would be dealt with.[93]

Despite the public warnings, crowds of monks and protesters similar in size to those seen on September 24 marched again down the streets of Rangoon, chanting slogans about non-violence. The protest march began at Shwedagon Pagoda without any government interference, then went to Sule Pagoda, and then throughout Rangoon before returning to their starting point at Shwedagon Pagoda and peacefully dispersing.

Reportedly for the first time in the protests, the banned "fighting peacock" flag of the student movement was carried by some marchers, a symbol of great significance following the role of the students in the 1988 uprising.[94]

On September 25, the All Burma Monks Alliance and the '88 Generation students issued a joint statement, praising the growing protests as "the biggest unity seen [in Burma] in the last twenty years." The joint statement urged the protesters to unite around the issues of economic reform, the release of political prisoners, and national reconciliation. The two groups warned that everyone should be aware of the dangers of a violent response from the authorities, citing the experience of 1988, but stressed that they were determined to continue the protests: "The monks and studentswill join hands with all the people and continue our struggle bravely and resolutely, step by step, for our beloved country."[95] The Bar Association of Burma, representing the nation's lawyers, also issued a statement, calling on the authorities to seek "a peaceful political solution" to the "legitimate demands" of the people, and offering a strong rebuke to the SPDCs governance, stating that "genuine politics should withstand the judgment of the people. We reject any 'forced politics' that does not withstand the judgment of the people."[96]

September 25-26: The Crackdown Begins

In the evening of September 25, trucks with loudspeakers announced a nighttime curfew from 9 p.m. to , and told people again not to participate in the protests. "U Maung Naing," an eyewitness from the ShwepyithaTownship in Rangoon told Human Rights Watch about the announcements:

On the night of the 25th, at , the ward Peace and Development Council and USDA went around and announced the curfew. They said not to go out from to , not to gather in groups of more than five people, and not to demonstrate by marching around town. They said not to join the monks, stating "The monks' marches are not the concern of the people." The announcement was made by loudspeaker. They mentioned it was law [article] 144 [prohibiting unlawful assemblies], but I am not sure what that means.[97]

That night, the authorities began to arrest some of the prominent public figures who had come out in support of the protests, including the comedian Zargana, who offered alms to the monks at Shwedagon Pagoda on September 24, and the opposition politician U Win Naing; both were detained at their homes. Other prominent figures who expressed support for the protests went into hiding.[98]

Overnight, the Burmese military moved large numbers of military forces into Rangoon and fully deployed large numbers of riot police in the city. "Su Su Hlaing" recalled how she saw a large military convoy move into downtown Rangoon at :

I was on Anawratha Road where my relative's house is. I heard some engine noise, and everyone went to look at the road. We saw military trucks going from Sule to Shwedagon. I think they were preparing for security [the crackdown]. I saw nine trucks, they were full of soldiers.[99]

Militia forces, including USDA members and Swan Arr Shin, were also on the streets in large numbers, working closely with the authorities.

Crackdown at Shwedagon Pagoda

Some of the most serious violence on September 26 took place at the eastern entrance of the Shwedagon Pagoda. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than a dozen eyewitnesses present during this clash, including a senior monk, bystanders, political activists who had helped organize the protests, and shopkeepers present in the area.

When monks and civilians started gathering as usual at the Shwedagon Pagoda on the morning of September 26, they found a heavy deployment of riot police and soldiers from the 66th and the 77th Light Infantry Divisions (LID) around the pagoda.[100]On the night of September 25-26, the security forces had raided the Kyae Thoon (Bronze Buddha Image) Pagoda where the monks had gathered every morning before proceeding on their marches.

Security forces had erected and were stationed behind barbwire barricades at several points along Kyaw Taw Ya Street (the main road around the eastern edge of the Shwedagon Pagoda). Plainclothes Swan Arr Shin members were also present around the pagoda, working closely with the security forces.[101]

Several eyewitnesses saw the director-general of the Burmese Police Force, Brigadier-General Khin Ye, who was dressed in a green army uniform, in the area of the crackdown. He appeared to be overseeing the crackdown and could be seen giving orders. Brigadier-General Khin Ye also was among the group of officials who spoke with the monks, and was seen pushing a monk away with his hands, a grave insult.[102]

At the eastern entrance of the pagoda, the army and riot police blocked a group of several hundred monks and civilians on the long staircase ascending to the pagoda by placing barbed wire barricades at both the bottom entrance of the stairway and the middle entrances of the stairway (at Ar Zar Ni Road). The security forces refused to allow the monks and civilians to ascend to the pagoda itself, and also refused to allow them to leave the area via Yae Dar Shae Road, instead demanding that the monks get into waiting Army trucks so they could be returned to their monasteries.[103] The monks refused, afraid they would be detained, and tried to enter into negotiations with Brigadier-General Khin Ye.

At about 11:30 a.m., more soldiers from the 77th LID came to reinforce the riot police. A large crowd of students and civilians gathered around the cordoned-off monks, angry at their treatment. The security forces had earlier enraged the crowd gathered around them by entering the pagoda with their shoes on.[104] They further enflamed the situation by pushing down an old monk who went up to them to request that the monks be allowed to leave. "U Maung Naing," an eyewitness, told Human Rights Watch:

There was an old monk, over 80-years-old, who requested that the [riot police] make way for the group. At that time, an officer with one star on his rank pushed the monk down. Many people were angry and ready to fight. The monks told the people to calm down. They told the people not to be violent and destroy our aim. The people and others tried to help up the old monk who had fallen.[105]

Violence and the use of teargas soon followed. "U Theika," a monk, who was part of the group trapped by the riot police, told Human Rights Watch what happened next, at about :

Every way was blocked by barbed-wire barricades, behind which were the riot police. About seven monks and I talked with the riot police about opening a way for us to march peacefully. We asked them to let the people march, but the commander did not allow it. He said that not more than five people could gather. The monks, students, and other people sat down and recited metta prayers. We talked with the authorities for nearly one hour. After that discussion, we were still not allowed to march