Scared Silent

Impunity for Extrajudicial Killings in the Philippines

I. Summary

Our hopes and prayers [are] for light and justice for our son Behind the pains that hurt the deep wound in our hearts we truly love him and we miss a great and unique man.

-Mother of shooting victim, LegazpiCity, September, 2006

Right now, there is this culture of impunity covering executive officials, that they can do whatever they want and they will not be held accountable.

-Senator Rodolfo Biazon, Chair of Committee on National Defense and Security, Manila, September, 2006

It's a complete breakdown of the rule of law. Civilian rule has been replaced by military rule. The courts don't function. The prosecutors don't function. The investigative agencies don't function. Lawyers are threatened.

-Romy Capulong, human rights lawyer, Manila, September, 2006

Rei-Mon Guran, known by his parents as "Ambo," but by his friends more colorfully as "Rambo," celebrated his 21st birthday with friends and family in his hometown of Bulan, in Sorsogon province, on July 30, 2006. Early the next morning Guran began to return to nearby LegazpiCity, where he was completing his second year as a political science student at AquinasUniversity. Guran's mother and father accompanied him to the bus stop to help him load his belongings, and to wave him farewell. As Guran sat in his seat, waiting for the bus to begin its journey, a man in plainclothes walked up the center aisle of the bus and paused in front of Guran. The man pulled out a .45 caliber pistol and shot Guran four times at point-blank range, then fled.

Rei-Mon Guran was a leader on his campus and in his community. He was an elected member of his student council, the spokesperson and provincial coordinator for the left-wing League of Filipino Students at AquinasUniversity, and an active member of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines' Christian Youth Fellowship.

Although the assailant was unidentified, Guran's political activities raise concerns that he was the target of Philippine security forces who deemed him to be linked to the long-running communist New People's Army (NPA) insurgency. An off-duty policeman was sitting on the bus when Guran was shot, but did not pursue the assailant. Other passengers were there, but not a single witness outside of the family will give evidence to the police. The witnesses say they are too scared, and fear reprisals from the assailants or their backers if they come forward. The police say that they cannot complete their investigation for lack of evidence and have asked Guran's family to plead with witnesses to speak with them. However, Guran's family have no means-nor the responsibility-to offer anyone protection from harassment or persecution that witnesses fear they may face in retaliation for giving evidence.

Rei-Mon Guran is just one case among hundreds of extrajudicial executions and failed prosecutions in the Philippines in recent years. This report, based on over 100 interviews and research that Human Rights Watch carried out in the Philippines between September and November 2006, documents the involvement of the armed forces in the killings of individuals because of their political activities. Witnesses and family members describe how members of left-wing political parties and non-governmental organizations, political journalists, outspoken clergy, anti-mining activists, and agricultural reform activists are being gunned down or "disappeared," with their murders going unprosecuted.

The pattern of these unlawful killings suggests they are intended to eliminate suspected supporters of the NPA and its political wing, the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), and to intimidate those who work for progressive causes certain critics in the government and armed forces consider linked to the insurgency. Human rights groups, local church leaders, and politicians have repeatedly raised concerns about the impact on civilians of a government policy of "all-out war" declared against the NPA in June 2006. Most of the victims of these political killings are members of legal political parties or organizations that the military claims are allied with the communist movement.

None of the incidents investigated by Human Rights Watch involved anyone who was participating in an armed encounter with the military or was otherwise involved in NPA military operations. Each victim appears to have been individually targeted for killing.

An investigating commission established by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo in August 2006 under the guidance of former Supreme Court Justice Jose Melo, completed its report in January 2007, finally giving voice to what has become an open secret in the Philippines. The report determined that the "killings of activists and media personnel is pursuant to an orchestrated plan by a group or sector with an interest in eliminating the victims, invariably activists and media personnel."Moreover, the Melo Commission concluded that "there is certainly evidence pointing the finger of suspicion at some elements and personalities in the armed forces, in particular General Palparan, as responsible for an undetermined number of killings, by allowing, tolerating, and even encouraging the killings." Nonetheless, Human Rights Watch was unable to uncover a single case of apparent extrajudicial killing in recent years for which a member of the armed forces was successfully prosecuted.

President Arroyo announced a wealth of new measures in the wake of the Melo Commission's conclusions and recommendations, but the president's initial efforts to keep the Commission report secret raises serious concerns about the political will to enforce these measures. In the end, it is actions that will speak louder than words, and the only real indication of the government's commitment to end these killings will be when the perpetrators are finally held to account in a court of law.

The Melo Commission report lamented that not a single witness came forward to provide eyewitness testimony of military participation in any extrajudicial killing. Human Rights Watch, however, was able to interview eyewitnesses to killings that identify the perpetrators as members of the military. In addition, Human Rights Watch's investigations uncovered other sources of information that support the allegations of the involvement of military personnel in many of the killings.

Yet the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) have to date wholly failed to hold any of its members accountable for these unlawful killings, including superior officers who ordered, encouraged, or permitted them. Nor has the military's high command-including Armed Forces Chief of Staff General Hermogenes Esperon, Jr.-shown any willingness to investigate senior officers for command responsibility, the doctrine by which a superior is held responsible when he or she knew or should have known about serious abuses but failed to take steps to prevent or punish the offenses.

Local police told Human Rights Watch that in some cases where they suspect military involvement in unlawful killings, they are unable to receive cooperation from military authorities in their investigations. In other cases, the police have clearly shied away from pursuing credible leads when they indicated the involvement of military personnel.

Indeed, an inquiry by the Philippines National Police (PNF), called Task Force Usig, begun in November 2006, laid the blame for most of the unlawful killings with the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People's Army, despite clear evidence of military involvement. The government should independently investigate whether the police and army have obstructed justice by blocking efforts to uncover abuse by the security forces.

In the areas where killings have occurred, there is distrust in the investigative efforts of the police. Victims' families and witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they receive scant details about police investigations, while in some instances, police provide misleading information to victims' families. Victims' families told Human Rights Watch that the only outcome they expect from police and military investigations is impunity for the perpetrators of the killings. In many of the cases that the police consider "solved," Human Rights Watch has found that police merely filed cases in court against suspects whose identities and whereabouts are unknown, often just known NPA members. This generates widespread fear, particularly in affected rural communities, of further military abuses, and witnesses and families are afraid to cooperate with police for fear of becoming targets of reprisal.

The government and the military need to put action behind their public endorsement of protecting human rights and their denial of involvement in killings. Victims' families are unlikely to believe the government's words until credible prosecutions have been a success. President Arroyo should therefore:

- Immediately issue an executive order to the Armed Forces of the Philippines and Philippines National Police reiterating the prohibition on the extrajudicial killing of any person. This prohibition does not include lawful attacks on combatants during hostilities with NPA forces.

- Vigorously investigate and prosecute members of the security forces implicated in killings, particularly those identified by the Melo Commission report.

- Immediately direct the Armed Forces of the Philippines, the Philippines National Police, and all other executive agencies to desist from statements that are incitement to violence, such as by implying that members of non-governmental organizations are valid targets of attack because of alleged association or sympathy with the Communist Party of the Philippines or the New People's Army.

Order the Inspector General of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, the Deputy Ombudsman, and the Provost Marshal of the Armed Forces to investigate and report publicly within 90 days on the involvement of military personnel in extrajudicial killing, and to identify failures within the Armed Forces of the Philippines investigative agencies to prosecute such criminal offenses, including, where appropriate, senior officers under the principles of command responsibility.

- Order the director of the National Bureau of Investigation to investigate and report publicly within 90 days on the failures of the Philippines National Police and Task Force Usig to adequately investigate and recommend for prosecution those military personnel implicated in extrajudicial executions. The report should also explain why Task Force Usig and the Melo Commission came to different conclusions with regards to the complicity of superior military officers.

- Order the Department of Justice to conduct a review within 60 days and publicly report on the failures of the current witness protection program and propose reforms. The Department of Justice should also circulate an explicit set of operational guidelines for the police stipulating individual police officer's duties to provide protection to witnesses and individuals who report threats on their lives. The guidelines should stipulate clear sanctions for officers who fail to provide necessary protection in conformity with these guidelines.

II. Methods

Research for this report was conducted in the Philippines between September and November 2006. Human Rights Watch conducted more than 50 interviews with witnesses, family members, and close friends of victims. These interviews-conducted in English, Tagalog, Cebuano, Bicalano, and Ilonggo, either directly with the report's authors or with the assistance of an interpreter-provided first-hand testimony of 19 incidents of extrajudicial executions or enforced disappearances that occurred between October 2005 and November 2006. We also spoke with four survivors of attempted killings carried out during 2006. Human Rights Watch visited the site of eight killings.

Cases were identified through consultations with journalists, church members, and non-governmental organizations in the Philippines and a survey of Philippine press accounts. Mindful of the broad spectrum of political organizations and "cause-oriented" organizations in the Philippines, Human Rights Watch made attempts to solicit cases from a variety of interest groups, as well as some cases where no political affiliation was apparent.

Interviews and field investigations were carried out in the following provinces: Albay, Bulacan, CompostelaValley, Davao, Davao del Norte, Davao del Sur, Metropolitan Manila, Negros Oriental, North Cotabato, Nueva Ecija, Sorsogon, and Tarlac.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed more than 50 government officials, lawmakers, academics, lawyers, diplomats, representatives of non-governmental agencies and civil society organizations, police, and members of the Philippines military. Human Rights Watch has also been in communications with the Embassy of the Republic of the Philippines in Washington, D.C., the Philippines Mission to the United Nations and International Organizations in Geneva.

Where names have been changed to protect the identity of interviewees because of security considerations, such changes are referenced in the footnotes.

III. Recent Military Relations with Government and Civil Society

People don't just get killed without any particular reason. There's always a motive. Some of them, I'm sure have personal reasons. For some of them, there are reasons for concern.

-Fernando Gonzalez, Governor of Albay province, Albay, 2006

Military involvement in politics

For more than 30 years, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) have been deeply involved in politics. Successive presidents, hoping to keep their hold on power, have fostered expectations of impunity by members of the military by implementing measures intended to placate restive officers-including amnesties or lenient punishments to coup plotters and human rights violators.

The disputed results of the snap election of 1986 between then-President Ferdinand Marcos and challenger Corazon Aquino, in which Marcos was officially declared the winner despite massive evidence of fraud, led directly to an aborted military takeover by young colonels allied with the then defense minister. When the plan to topple the government and put in place a junta was discovered by Marcos and its leaders threatened with arrest, the mutineers quickly made common cause with Aquino and the Roman Catholic Church and appealed for popular support-"people power"-that quickly propelled Aquino to the presidency.

Having come so close to power, the rebellious colonels quickly grew dissatisfied with Aquino's government and within months were plotting to topple her administration, very nearly succeeding on several occasions. But punishments for the plotters during the Aquino years were generally light, thus reinforcing impunity.

Aquino was succeeded in 1992 by Fidel Ramos, a career military officer, whose standing with the military and involvement in overthrowing Marcos to some extent helped check that impunity. He declared an amnesty for rebel soldiers, opened peace talks with communist insurgents, and presided over a period of relative economic strength and political calm.

When Vice-President Joseph Estrada, a former movie actor who had been close to Marcos, was elected president in 1998, political upheaval was again in the wind. Wildly popular with the poor majority of Filipinos for his cinematic exploits, Estrada was soon accused of corruption and immorality in office. A coalition of church leaders, the business elite, and the military again emerged to challenge him after he was implicated in a financial scandal. With Estrada still in office and impeachment proceedings against him not yet concluded, the coalition shifted, and the military moved its support to then-Vice-President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo and helped install her in office. Although the changeover was validated by a decision from the Philippines Supreme Court, critics questioned the constitutional legality of Arroyo's assumption of the office, and her administration has been under a cloud ever since.

While Arroyo has insisted that she is doing everything possible to investigate extrajudicial killings, the campaign of killings seemed to shift into a higher gear in February 2006 after leftist political parties were accused by members of the government of allying themselves with military rebels planning to overthrow her government. In the aftermath of that coup attempt, which failed when the military hierarchy rejected overtures from rebel colonels, Arroyo declared a state of emergency and castigated a handful of leftists from legal political parties who have gained seats in Congress. Cases have been filed against a number of politicians for allegedly backing the attempt to overthrow her.

Human rights activists remain concerned that Arroyo remains beholden to the military officers who put her in power, and that they are preventing her from disciplining those in the military who may be implicated in rights violations. As one commentator told Human Rights Watch, this puts the president in a position where her ongoing survival depends on weakening the political opposition-particularly from the vocal left-while feeding "the loyalty of the key state players crucial to her political survival, notably, the military,"[1] whom she is increasingly unable or unwilling to control.

Military campaign against the New People's Army

The New People's Army (NPA) is the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), which since 1969 has been engaged in an armed rebellion with the goal of establishing a Marxist state.[2] Military estimates put the armed strength of the NPA at around 7,500 guerrillas,[3] and the rebels are supported by a broad network of non-combatant supporters. The NPA and the CPP continue to exact what they call "revolutionary justice" against individuals in areas under their control, including the kidnapping and unlawful killing of those government officials, police, landlords, business owners, and local thugs whom they consider to be criminals against the people.

Such attacks on civilians constitute grave abuses of individuals' fundamental human rights and are violations of the laws of war. As such, they deserve the strongest condemnation, and the Philippine government is obliged to prosecute such violations to the fullest extent of the law. However, such abuses by insurgents do not justify the military or the government committing further human rights violations through extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances of any person, including members of political groups and civil society organizations that are sympathetic to the insurgents' cause.

Peace talks between the government and the NPA collapsed in September 2005, following the government's refusal to seek the removal of the NPA, the CPP, and their uniting organization, the National Democratic Front (NDF), from the terrorist watch-lists of the European Union and the United States. Reports about the NPA's strength vary considerably, though in certain areas its presence can affect local security considerably.[4]

In June 2006 President Arroyo declared a new strategy of "all-out war" against the communist insurgency designed to eliminate the NPA once and for all. "The CPP-NPA has done enough in setting back peace and development for more than 30 years," said Ignacio Bunye, Arroyo's spokesman, at the time of the announcement. "The time has come to finally defeat this threat through a combination of military operations, law enforcement and pro-poor programs."[5]

President Arroyo also budgeted 1 billion pesos (US$20.5 million) towards this goal, and is committing thousands more troops to the anti-insurgency campaigns in central and southern Luzon and the Bicol region. There is reason to fear that this new pressure on the military to produce results may be leading to an increase in serious violations of human rights. As one commentator told Human Rights Watch, the President giving this order "to root out an insurgency that's been going on for the last 30 years creates an atmosphere within the military, where the President says we have to get this done, and we can't get it done on the battlefield, so let's get at them by other means [and] take shortcuts."[6]

Congressman Teodoro Casio, a member of the left-wing Bayan Muna party, says the foiled February coup plot was also being used as an excuse to go after leftist opponents of the government out of revenge. He saw a direct relationship between the February coup plot, the June declaration of an "all-out war," and the rise in political killings. "[The military] have removed the distinction between combatants and those who are in civilian groups," he says.[7]

The military and leftist political and civil society groups

The Philippines has one of the largest, best organized, and most active communities of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in the developing world, representing a broad spectrum of political perspectives.[8]

Many left-wing NGOs are especially vocal in their opposition to the Arroyo administration. It is the members of such organizations-particularly civil society groups viewed by the military as being associated with the CPP and NPA-who appear to have been targeted in the spate of political killings. For many decades, the CPP-NPA-NDF coalition have had considerable influence on many left-wing NGOs, including the establishment of new NGOs to support their revolutionary cause, and by extracting funding from supportive NGOs to further the armed rebellion.[9]

The relationship between such sympathetic NGOs and the CPP-NPA-NDF alliance has sometimes been contentious. Most damaging was the rift that developed within the CPP in the early 1990s between those who "reaffirmed" and those who "rejected" the Party's continued following of Marxist-Leninist-Mao Zedong ideology and the chairmanship of the Party by Jose Maria Sison. Many of the legal organizations who were previously sympathetic to the underground left also fragmented along similar lines, with different sides seizing different organizational assets.

The scars of this split still permeate the progressive NGO community today. For example, a comparison of the public lists of unsolved political killings during the first six months of 2006 claimed by the "reaffirm" NGO Karapatan and the "reject" NGO Philippines Alliance for Human Rights Advocates, contained only one name in common. Members of some NGOs complained to Human Rights Watch that other NGOs tended to be highly proprietary with their research and data on extrajudicial killings and harassment of their members, harming the ability of NGOs to build a stronger coalition to oppose such developments. As one leading journalist told Human Rights Watch, the consequence is that "NGOs are suffering from a lack of sympathy problem, [only] crying when their own people are hurt."[10]

The progressive and activist NGOs are also often affiliated with political parties, in particular the so-called "party-list" organizations. In the 250-member House of Representatives, certain interest groups, such as the rural poor or the elderly, are represented through "sectoral representatives," selected by the popular vote. Any organization that wins more than 2 percent of the vote is awarded one seat for every 2 percent that they received, up to a maximum of three representatives.

The three party-list organizations most closely aligned with the "reaffirm" leftist activist groups are Bayan Muna, Anakpawis, and Gabriella. All three are legal political parties. Bayan Muna was formed in 1999 by representatives from various grassroots organizations, and played a prominent role in the "people power" uprising of 2001 that displaced President Estrada and launched Arroyo into power. Bayan Muna won the most electoral support for a party-list organization in the 2001 elections, and therefore claimed the maximum three seats in the House of Representatives. By the 2004 elections two of Bayan Muna's representatives established ties with two new sectoral groups-Anakpawis and Gabriella-in an effort to increase the overall representation of progressive leftist interests in the Congress. In the 2004 elections Bayan Muna again won the most votes for party-list representatives and captured the maximum three seats, and Anakpawis and Gabriela each received one seat.

Despite their original supportive role in the public demonstrations that brought Arroyo to the presidency, these three party-list organizations now count as some of her most vocal opposition, and have proved highly efficient in mobilizing public protests against her rule. As a prominent journalist explained to Human Rights Watch: "The left has been supplying the bodies for the anti-Gloria rallies."[11]

Some political analysts view the increased electoral success of these sectoral groups, and the role they play in fomenting popular opposition to the Arroyo administration, as key reasons behind increased harassment and pressure on such groups. One commentator explained: "People like [National Security Advisor Norberto] Gonzalez are really obsessed with dealing with Bayan Muna and other CPP fronts."[12]

Legal NGOs and political parties in the Philippines have long had uneasy relations with the security forces because of their perceived or real ties to the CPP-NPA-NDF. In the late 1980s NGO workers and human rights activists and lawyers were frequent targets for arbitrary arrest, torture, and killing as a result of their perceived sympathies with the underground left and their high profile in local elections.[13] These violations were variously carried out by members of the AFP or members of anti-communist "vigilante" groups established and armed by the army.[14] The AFP also established local militias to assist in its counter-insurgency operations.[15]

In 1992 President Ramos de-criminalized membership in the CPP through the repeal of an old Anti-Subversion Law as part of attempts to end the conflict. The establishment of the party-list system in 1995 also provided an opportunity for organizations linked with the CPP to seek election and participation in the legal, democratic political process as an alternative to armed struggle.

Although antagonism between the military and the NGOs waned during the mid-1990s, suspicions continued on both sides. The ongoing ideological splits within the NGO community has made it relatively easy for military officials to dismiss the claims of the NGO Karapatan and other left-wing groups as ideologically biased and has contributed to putting activists at risk when military authorities accuse them of being allied with the insurgency. It has also meant that Karapatan and many military officers simply refuse to talk to one another to resolve disputes. Major General Juanito Gomez, the commander of the army's 7th Infantry Division in Central Luzon, refuses to meet members of Karapatan on the subject of extrajudicial killings. "Personally I would say they are biased," General Gomez told Human Rights Watch. "We will not be discussing [anything] with them."[16]

Human Rights Watch is concerned that the pressure of Arroyo's declaration of a two-year deadline for the military to eradicate the communist insurgents has had a dangerous effect on civilians in areas targeted for counter-insurgency actions. Josie dela Cruz, the Governor of Bulacan Province, met with the then-AFP commander in her region, General Jovito Palparan, on numerous occasions to discuss his military operations. As she put it: "In his terminology there are no sympathizers, you are either with the NPA or not, either with the military or not. As far as Palparan is concerned, once you deal with the NPA you are the NPA."[17]

Although General Palparan-retired since September 2006-denies allegations from local human rights organizations that political killings escalated wherever he was in charge of counter-insurgency efforts, he has noted on more than one occasion that the extrajudicial killings were "helping" the armed forces by eliminating individuals who oppose the government and commit "illegal activities" in support of the NPA.[18] While still in command, General Palparan noted that the killings were "being attributed to me, but I did not kill them. I just inspired [the triggermen]We are not admitting responsibility here, what I'm saying is that these are necessary incidents."[19]

Palparan has been vocal in explaining his view that legal left-wing groups are in partnership with the CPP: "It is my belief that these members of party lists in Congress are providing the day-to-day policies of the [rebel] movement."[20] He has also singled out party-list leaders, saying "even though they're in government, no matter what appearance they take, they are still enemies of the state."[21] Palparan also alleges that the rebel network also includes hundreds or thousands of outwardly legal NGOs infiltrated or directed by the CPP that "provides the materials, the shelter" for the NPA, and he describes such organizations are "legal but they're doing illegal activities."[22] In response, as reported by Agence France Presse, Palparan proposed that:

"We need to strengthen our legal offensive" against this network, while warning that an effective counter-insurgency campaign will necessarily be messy and that, "There will be some... collateral damage but it will be short and tolerable, (and in the end) acceptableThe enemy would blow it up as a massive violation of human rights, but to me it would just be necessary incidents compared to what will happen really if we do not decisively confront the problem."[23]

Human Rights Watch collected first-hand accounts of military personnel implicated in the harassment, arbitrary detention, and other human rights violations in areas targeted for counter-insurgency activities. Such measures appear intended to intimidate the civilian population from supporting the insurgents. According to Miriam Coronel Ferrer, a professor at the University of the Philippines' Center for Integrative and Development Studies:

The unprecedented high number of killings of political activists associated with national democratic organizations in [a] compressed time is part of this "collective punishment" frame. The extrajudicial killings we have seen share the same features of rural community-based counter-guerilla warfare: indiscriminate or dismissive of the distinction between combatants and non-combatants, and clouded by "hate language" and demonization of the enemy. The killings' desired impact is the same: fear, paralysis, scuttling of the organizational network, albeit not just in the local but the national sense. The goal is to break the political infrastructure of the movement whose good showing in the past election (under the party list system) and corresponding access to pork barrel funds and a public platform, were, from the point of view of the anti-communist state, alarming.[24]

Senator Rodolgo Biazon, a former AFP chief of staff, attributed the rights violations to military personnel who feel constrained in fighting the insurgency:

It may be because of frustration by people operating on the ground [That these are legal groups that] are allowed to participate in the political process and the perception continues that this Communist Party-although they don't call themselves the Communist Party-are providing support to the rebels, and the [military] can do nothing about it."[25]

Many close observers of the military's counter-insurgency campaign expressed to Human Rights Watch their concern that the military's heavy-handed tactics against noncombatants would prove counter-productive. Drawing on his own experiences fighting the NPA, Senator Biazon told us:

My concern here is my belief that when you are fighting an insurgency, it is not just a military problem, it is also an economic and social problem You need to isolate the insurgents from the people Somehow I think it's a wrong tack for the government to take, because it could drive our people into the arms of the insurgents We could be pushing more and more people to consider extra-constitutional means to effect these reforms and changes [because of this] perceived adoption of a government policy that encourages political killings, "disappearances," and simple violations of the human rights by our security forces Because that's what I saw under Martial Law.[26]

Recent Developments

Since Human Rights Watch conducted its initial field investigation into the issue of extrajudicial executions in the Philippines in September 2007, three major investigations have released their own findings, or preliminary findings. Two of these investigations were carried out by government-appointed bodies: Task Force Usig and the Melo Commission. A third investigation was conducted by the UN's Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions.

Task Force Usig

In August 2006 President Arroyo created a special police body, Task Force Usig, which she charged with solving 10 cases of killings of political activists or journalists within 10 weeks. During its 10-week mandate the Task Force claims that 21 cases were solved by filing cases in court against identified suspects, all of them members of the CPP and NPA. Only 12 suspects involved in these incidents were actually in police custody.

Following its initial 10-week mandate, Task Force Usig has continued its investigations and is the lead investigatory body within the PNP on cases of killings of political activists and members of the media.

Melo Commission

Later in August 2006 President Arroyo also created a commission to further probe the killings of media workers and left-wing activists since 2001. The President appointed former Supreme Court Associate Justice Jose Melo to lead the commission, which was comprised of National Bureau of Investigation Director Nestor Mantaring, Chief State Prosecutor Jovencito Zuo, Bishop Juan de dios Pueblos, and Nelia Torres Gonzales, a member of the Board of Regents of the University of the Philippines.

Opposition and human rights groups criticized the Melo Commission for having little power to carry out investigations and for its membership of only government-selected commissioners.

Perceiving that the composition of the Commission indicated a bias in favor of the Arroyo administration, many activist and human rights groups refused to provide testimony to the Commission, and may have advised some victims not to appear before the Commission. Nonetheless, the Commission proceeded with its investigations, calling representatives of the military, the police, and speaking with the family members of certain victims.

The Commission concluded its report in January 2007, but the President initially fought to keep the report secret. Under pressure from United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions, Philip Alston-who conducted a 10-day visit to the Philippines in February 2007-the government released the report on February 22, 2007. In the report the Commission concedes that it was not created to solve any of the killings by pinpointing the actual gunman involved. That task, the report notes, will "take years and an army of investigators and prosecutors to finish, [and] would be best left to the regularly constituted law enforcement authorities and the Department of Justice."[27]

However, the report found that "there is no shirking the fact that people, almost all of them activists or militants, have been killed. [T]he victims, of which this Commission is concerned, were all non-combatants. They were not killed in armed clashed or engagements with the military."[28] The report also concludes that the "killings of activists and media personnel is pursuant to an orchestrated plan by a group or sector with an interest in eliminating the victims, invariably activists and media personnel."[29]

The ultimate finding of the Commission was:

There is no official or sanctioned policy on the part of the military or its civilian superiors to resort to what other countries euphemistically call "alternative procedures"-meaning illegal liquidations. However, there is certainly evidence pointing the finger of suspicion at some elements and personalities in the armed forces, in particular General Palparan, as responsible for an undetermined number of killings, by allowing, tolerating, and even encouraging the killings.[30]

President Arroyo announced a number of new measures in the wake of comments by members of the Melo Commission about the substance of their report, but before she allowed the report to be made public. These measures included:

- The Department of National Defense (DND) and the Armed Forces of the Philippines are to come up with an updated document on command responsibility;

- The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the DND shall coordinate with the Commission on Human Rights to constitute a Joint Fact-Finding body to delve deeper into the alleged involvement of military personnel in unexplained killings, file charges against those responsible and prosecute the culpable parties;

- The DOJ to broaden and enhance the Witness Protection Program;

- The Chief Presidential Legal Counsel to request the Supreme Court to create Special Courts for the trial of cases involving killings of a political/ideological nature.

- Request technical assistance and investigators from the European Union and the governments of Spain, Sweden, Finland, United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Germany and the Netherlands in order to assist Philippine Government efforts to resolve this issue.[31]

In early March 2007 the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Reynato Puno, issued Administrative Order 25-2007 designating nearly all of the 99 trial courts across the country as special tribunals to try cases of political killings, a designation which is apparently intended to give priority to such cases in the courts' trial calendars. The order also mandates continuous trials for such cases, and limits the duration of such trials to 60 days after their commencement, with judgment to be rendered within 30 days of the close of trial. These "special courts" will be required to submit a report on the status of their cases, and failure to do so constitutes grounds for withholding the salaries and allowances of the judges, clerks of court, and branch clerks of court concerned.[32]

Although only time will tell the effectiveness of these new proposed measures, they do not all necessarily address problems identified by either the Melo Commission report, nor by this report by Human Rights Watch. In particular:

- The President has ordered the DND to produce a new summary of the existing laws on command responsibility. However, it is the current failure of the Philippines National Police and the Armed Forces of the Philippines to actually enforce existing laws and regulations-found in both international treaties to which the Philippines is a party, customary principles of the laws of war, and the Philippines own Articles of War-that has led to the failure to prosecute superior officers. Therefore, the most important indication of commitment by the AFP and PNP to ending extrajudicial killings will not be when they produce new documents summarizing existing laws, but instead, when they choose to start using the existing laws to prosecute culpable superior officers.

- By proposing that the DND, the DOJ, and the Commission on Human Rights develop a joint-fact finding body to investigate military involvement in extrajudicial killings, the president seems to ignore that the real problem, which is that the police already have the power and responsibility to investigate and bring charges against responsible individuals, yet chose not to do so. The president should not charge the responsibility for investigating and prosecuting military involvement to agencies that lack the necessary legal or technical capacity to do so credibly. If the president believes it is imperative to assign this responsibility to additional agencies rather than just ensuring that the police carry out their existing duties, whichever government agencies are encouraged to investigate military involvement in political killings must be given the necessary legal and technical powers to carry out such an investigation, including the power to subpoena individuals, compel testimony, lay criminal charges, and provide protection to witnesses.

- Although a broadening and enhancement of the Witness Protection Program is to be welcomed, it should be noted that even the current program is not being implemented to provide protection to witnesses, and the DOJ should be required to report on why the existing witness protection program is being underutilized.

- The new "special courts" proposed by the president and established by the Supreme Court chief justice must be established and used to facilitate the prosecutions of persons accused of political killings in accordance with international fair trial standards-and not to deny justice for the victims and their families. Moreover, if the president and the Supreme Court chief justice have identified failings within the existing prosecutorial and judicial system which hinder the prosecution of individuals involved in extrajudicial executions, then it is imperative that such failings in the existing system are also corrected.

- Human Rights Watch welcomes the invitation of international observers and fact-finders, but notes that, as shown in this report, international investigators who have previously investigated killings in the Philippines have been blacklisted from entering the Philippines because of their work, and at times have been harassed and threatened by the military.

Visit by the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions

From February 12 to 21, 2007, the United Nations' Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary, or Arbitrary Executions, Philip Alston, visited the Philippines at the invitation of the government, where he met with government officials, civil society representatives, witnesses of extrajudicial killings, and the family members of victims.[33]

Despite his official invitation from the government, the Special Rapporteur was vehemently criticized by certain individual members of the government and military. Justice Secretary Raul Gonzalez called the Special Rapporteur a "muchacho" (lowly servant) at the UN, and also accused him of having been "brainwashed" by leftists.[34] According to the Special Rapporteur, the Defense Secretary Hermogenes Ebdane called him "blind, mute and deaf," while the chief of staff of the Armed Forces was apparently "less eloquent but equally dismissive."[35] In a statement before the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, the Special Rapporteur said:

Part of me appreciates the substitution of frank insults for the usual diplomatic platitudes, but anyone reading between the lines will receive a far more disturbing message: Those government officials who must act decisively if the killings are to end, still refuse to accept that there is even a problem.[36]

In a statement released at the end of his mission, the Special Rapporteur stated his opinion that "the AFP remains in a state of almost total denial of its need to respond effectively and authentically to the significant number of killings which have been convincingly attributed to them." He went on to note that it was the responsibility of the president to persuade the military that "its reputation and effectiveness will be considerably enhanced, rather than undermined, by acknowledging the facts and taking genuine steps to investigate."[37]

Regarding the government's response to the crisis of extrajudicial executions, the Special Rapporteur noted that:

There has been a welcome acknowledgment of the seriousness of the problem at the very top. At the executive level the messages have been very mixed and often unsatisfactory. And at the operational level, the allegations have too often been met with a response of incredulity, mixed with offence.[38]

The Special Rapporteur's statement highlighted the need "to restore accountability mechanisms that the Philippines Constitution and Congress have put in place over the years, too many of which have been systematically drained of their force in recent years."[39]

The press statement stressed that the failure to provide adequate protection to witnesses and their vulnerability was a "rampant problem."[40]

The Special Rapporteur emphasized the need to provide "legitimate political space for leftist groups." Noting how former President Ramos had pursued a strategy of reconciliation to provide an incentive for such groups to enter mainstream politics, the current executive branch, "openly and enthusiastically aided by the military, has worked resolutely to impede the work of the party-list groups and to put in question their right to operate freely." Such actions were intended not to destroy the NPA, but "to eliminate organizations that support many of its goals and do not actively disown its means."[41]

IV. Extrajudicial Executions

Since President Arroyo came to power in 2001, extrajudicial executions have been on the rise.

A number of local and international actors have attempted to qualify the number of victims of politically motivated killings in the Philippines since the beginning of the Arroyo administration in 2001. The conclusions of these different efforts vary, as does the methodology of data collection for each effort, and the ideology of the groups doing the collecting.

In a December 2006 update, the Philippines National Police's investigation into political killings, Task Force Usig, concluded that there were 115 cases of "slain party list /militant members" since 2001, and 26 cases of "mediamen."[42] The human rights group Karapatan, which is closely aligned with the far-left political parties and groups, asserts that 206 people were victims of extrajudicial executions just in 2006, of whom 99 were political activists, and the remainder civilians suspected of sympathizing with leftist groups.Karapatan's list of extrajudicial executions since Arroyo came to power in 2001 tops 800 people. Other human rights groups, such as the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA) and Amnesty International have also come up with different statistics for different time periods. Amnesty has estimated 50 killings between January and June in its report of August 15, 2006,[43] and PAHRA gave the same number for the same period.[44] The Philippine Daily Inquirer reports 299 killings between October 2001 and April 2007.[45]

Human Rights Watch does not have the capacity to verify any one particular set of numbers or list of victims. However, our research, based on accounts from eyewitnesses and victims' families, found that members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) were responsible for many of the recent unlawful killings. The motive for the killings often appears to be the political activities, or the perceived political activities, of the victim.

The unlawful killing of individuals because of their political affiliation, or the perceived political nature of their activities, is not a new phenomenon in the Philippines. However, opposition politicians claim that killings are increasingly frequent. Congressman Teodoro Casio, a member of the leftist Bayan Muna political party, which claims to have lost more than 100 members to illegal killings since President Arroyo came to power in 2001, explained:

We've had them since [President Ferdinand] Marcos' era, and it hasn't stopped. But we've noticed that since 2001 the numbers have escalated at an alarming pace. Previously, a significant number of victims were with armed underground groups. But we have noticed that since 2001 nearly all of these victims are not members of armed groups, but are members of legal groups who are very critical of the Government.[46]

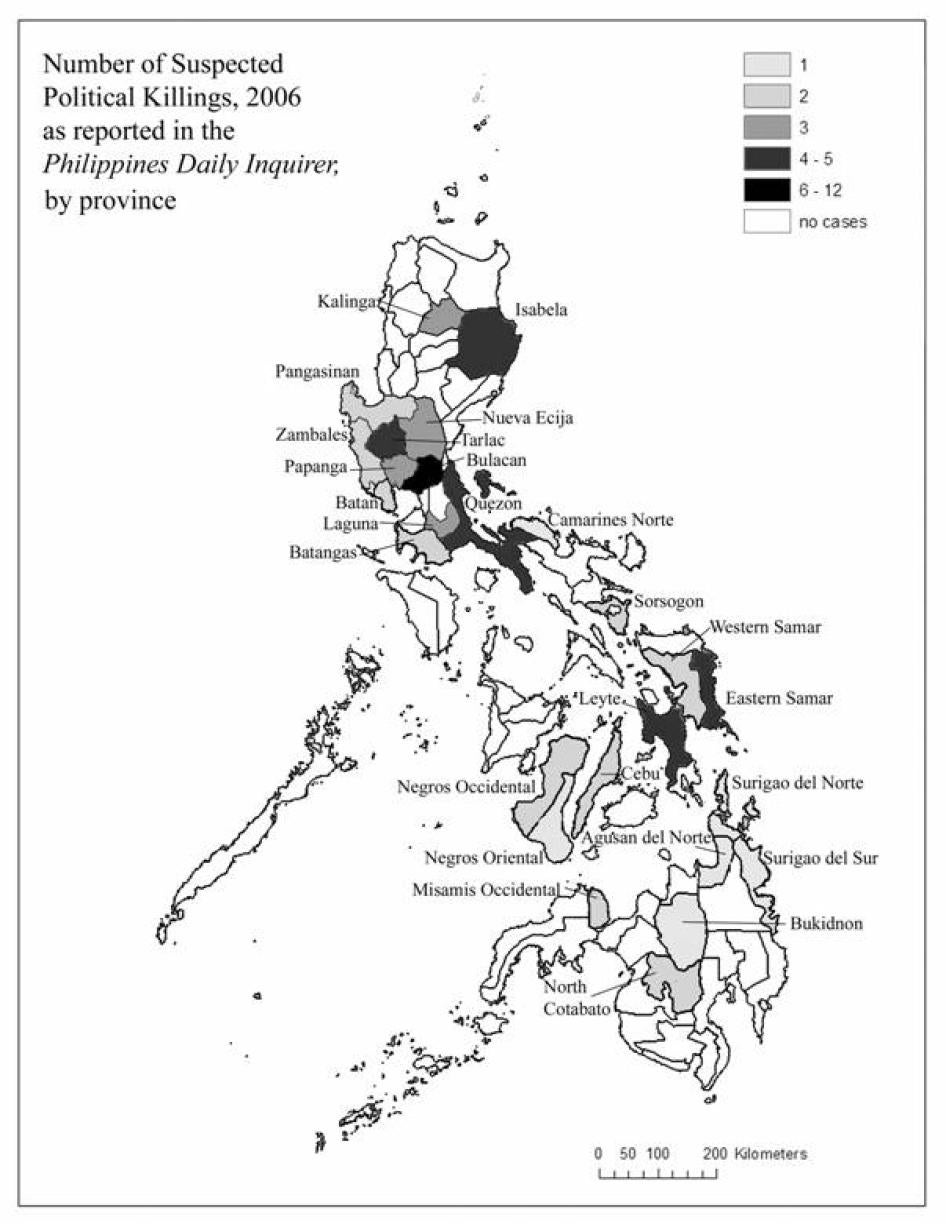

In the Philippines such killings by the security forces or by the NPA are colloquially referred to as "political killings," and they are occurring throughout the archipelago (see Figure 1). These include instances, including "disappearances,"[47] in which individuals are abducted and never heard from again, never released, and a body is never located, leading to people being considered "disappeared."

Figure 1: Suspected Political Killings as Reported in the Philippines Daily Inquirer during 2006, by location.

2006Elena Semenova

Victims of political killings or "disappearances" come from a number of professions and backgrounds, including members of the left-wing "party list" political parties Bayan Muna, Anakpawis, and Gabriela. Others includestudent activists, anti-mining activists, political journalists, clergy, and agricultural reformers.

The large number of killings does not tell the whole story. Some of the victims of this spate of extrajudicial executions had national political reputations. For example, Sotero Llamas, who was shot in his car on the morning of May 29, 2006, as he and his driver passed through his home town of Tabaco City, in Albay province, had been the former Bicol region NPA commander (see case below). The death of an individual who severed ties with the CPP-NPA many years earlier suggests that the targeted killings may not be time-bound to current activities, which can create even more fear and uncertainty in a community, particularly for those who put down their weapons years ago. The majority of victims of the political killings, however, were involved in political activism at a low-level, with at most local notoriety. The cases of two student members of the left-wing League of Filipino Students who were gunned down in the Bicol region in 2006 exemplifies this (see below).

In a few other cases involving military personnel, non-political reasons may be behind the crime. Murder has long been a common method to settle scores in the Philippines, including local political rivalries, disputes over land, corruption, and personal disputes.

Extrajudicial executions

This is how it always happens since time immemorial with these insurgency campaigns. They get out of hand.

- Governor Josie dela Cruz, Manila, September, 2006

In a number of cases of unlawful killings Human Rights Watch investigated, there was strong evidence implicating military personnel. These cases come from around the country, including five incidents in Central Luzon, two in Bicol, and two in Mindanao.

Pastor Isias de Leon Santa Rosa

The killing of Pastor Isias de Leon Santa Rosa in Bicol on August 3, 2006, provides clear physical evidence of involvement by military personnel. Just before 8 in the evening that day, there was a knock on the door. The victim's wife Sonia Santa Rosa recounted what happened:

Immediately when I opened the door, about 10 armed men entered the house. [One of them] was shouting, commanding the others "Enter!" and to us "Lie down!" All of us lay down and they pointed guns at our heads A short firearm. After 5 minutes they brought my husband to the room of my younger daughter They asked him if he is Elmer. My husband did not answer. Then he answered, "I am not Elmer. You can even verify, look at my ID." We don't know who Elmer is. We've never heard the name before All the time I was just comforting our [four] children, because the children were really crying. One of the men said "Just follow our orders and you will not be harmed." They searched the living room and the other rooms. They took with them the laptop, the printer, and a bag of personal belongings of my husband, including some cash and cell phones, and a samurai knife that was being displayed [on the wall] My husband was dragged out and all the men left. Knowing that the group had fled, I went outside to get the help of neighbors. I shouted "Help! Help!" Many neighbors came here, gathered here, and then we heard nine gunshots. [That was] 5 minutes after my husband was dragged out of the house [We heard the] gunshots at about 8 p.m.[48]

The shots appeared to be coming from a nearby stream. Local police arriving at the ditch leading down to the stream found not one, but two, bodies. Santa Rosa's body lay face down, and about five meters away lay another body, face up.[49]

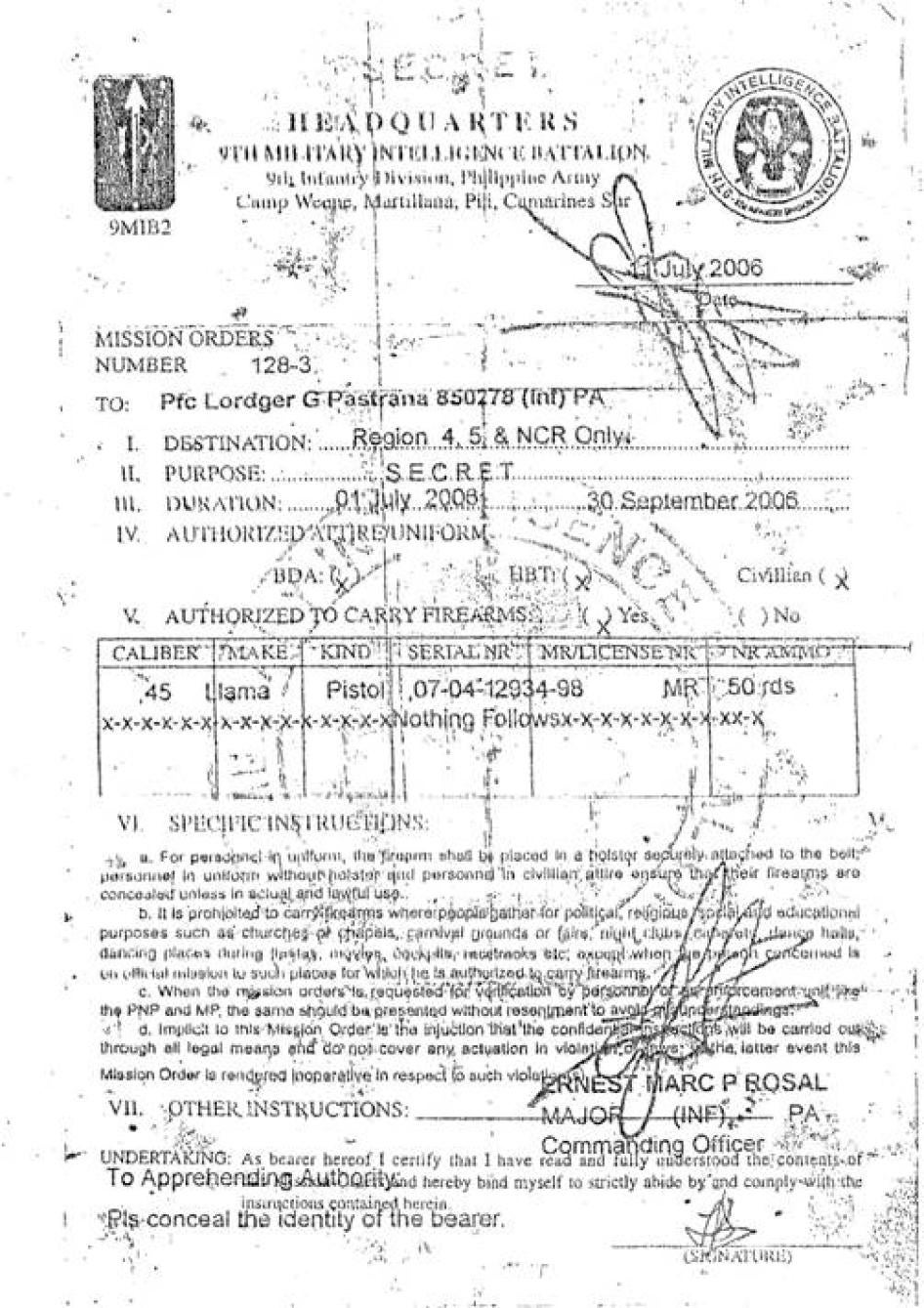

According to the police report, the second body was of a male, wearing a balaclava over his face. A .45 caliber Llama pistol and one magazine loaded with six bullets were found by the body.[50] Local police also discovered a brown wallet on the body containing an AFP identification card in the name of Corporal Lordger Pastrana, serial number 850278 (see Figure 2). Also found on Pastrana's body was a mission order marked "SECRET" from the 9th Military Intelligence Battalion for Pfc. Lordger Pastrana, serial number 850278, authorizing him to carry a .45 caliber Llama pistol from July 1, 2006, until September 30, 2006 (see Figure 3).[51] Pastor Santa Rosa's brother confirmed to Human Rights Watch that the body belonged to one of the men who entered their house, identifying him by his clothing, and said that the dead man was the one that the rest of the men called "Sir."[52]

Figure 2: A military identification card in the name of Lordger Pastrana, found on the body of one of the assailants who dragged Father Isias de Leon Santa Rosa from his home. From the police file of investigation of the killing of Isias de Leon Santa Rosa, DaragaMunicipal Police. 2006 Bede Sheppard

Figure 3: A mission order marked "SECRET" from the 9th Military Intelligence Battalion 2006 Bede Sheppard

Forensic testing by the police of the firearm confirmed that one of the cartridge cases found at the scene of the shooting matched the pistol authorized by the AFP to Pastrana and found in his possession. However, another two slugs submitted for examination, including one found in Santa Rosa's body, did not match the firearm.[53] The official autopsy indicates that Pastrana was shot from the side, with the bullet passing from his left armpit and out through his right shoulder.[54] Together, this evidence suggests-but is not conclusive-that Pastrana may have been shot by accident by another member of his team while either he or another team member attempted to execute Pastor Santa Rosa.

Sonia was uncertain why her husband was killed. According to Sonia, "My husband was a writer. He wasn't outspoken. He wrote anti-mining brochures, against the Lafayette mining at Rapu-Rapu [and] on [agrarian reform] issues."[55]

Ricardo Ramos

Ricardo "Ric" Ramos was the president of the Central Azucarrera de Tarlac Labor Union and also a local village official. In September 2005 he received a funeral wreath that said: "RIP Ricardo Ramos." According to Ramos' brother, there had been a list of communist sympathizers circulated with Ramos' name on it, along with a local village official and labor leader named Abel Ladera, who was shot and killed in March 2005.[56]

On the morning of October 25, 2005, the Department of Labor and Employment visited the hacienda where Ramos worked. They came to oversee the distribution of wages to the 700 or so union workers covered by an agreement that had just been struck during a strike in which Ramos had been involved. One eyewitness told us: "I noticed during the distribution of the money that the army was around. Ric [Ramos] told the soldiers to go away."[57]

Two soldiers, whom the witnesses saw among these military personnel, went to see Ramos later in the afternoon. He was resting in a traditional thatch hut used as a meeting hall by the union and village leaders. Told that Ramos was sleeping, the two soldiers returned between 7 and when Ramos was talking to other people, and they were again turned away and told to come back later. Around that evening, a group of around 20 men were seated at a table in the hut, drinking and talking. Ramos was seated facing a wall and looking down sending a text message on his cell phone. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they heard two shots and saw Ramos shot in the head: "His brains splattered against the roof with a wet sound."[58]

Two eyewitnesses took Human Rights Watch to the site of the killing, then walked us away from the hut to a spot just inside a small fence by a neighboring house, from where there is a clear line of fire about 10 meters to where Ramos had been sitting. It is possible to see through the slats of the hut to the inside. The victim's brother told us that it was here that police found two shells from an M14 rifle. The M14 is a Philippine army issued weapon, often used as a sniper rifle.

At the time of the killing, the army had a small detachment about 50 meters from where the shooting occurred. Yet it was security guards from the hacienda who were the first to respond. According to witnesses, the detachment was then removed: "That night after the killing, an [armored personnel carrier] arrived, with a large truck and a helicopter to take the soldiers away."[59]

The eyewitnesses told Human Rights Watch that an arrest order had apparently been issued for the two soldiers accused of killing Ramos. However, charges against one of the accused, a private, were later dropped, and according to the victim's brother, the remaining suspect, a sergeant with the 7th Infantry Battalion, remains free and apparently still on active service.[60] "I appeal to General Esperon to execute the warrant of arrest," Ricardo Ramos' brother told us.[61]

Attempted Killing of "Nestor Gonzalez"

When Human Rights Watch met "Nestor Gonzalez,"he had been hiding in a church sanctuary with members of his family since being released from the hospital having survived being shot four times. He took one bullet to his neck, damaging the bundle of nerves running from his neck to his right arm, leaving his arm in constant pain. Nestor Gonzalez'sfamily was reliant on charity from prominent individuals in town to cover the cost of necessary painkillers and medication, and to fund an upcoming operation to improve the condition of his arm. Fighting the pain in his body, Nestor Gonzalezrecounted what he remembers of the evening in late 2006 he was shot:

That night, I was in my house taking care of my wife who just gave birth to my youngest son. Then suddenly I hear someone calling me from outside: "Big Brother! Big Brother!" When I tried to see [through the window] who was calling for me I saw a gun pointed at me, so I tried to duck, and I was shot in the neck. The police told me that the shells are from a .45 caliber pistol. I saw a small gun. I only saw one man. That was the one who shot me. He was wearing a uniform. Because it was dark, I could not know what kind of uniform, but I saw a jacket, pants, hat. Also I was not able to see his face because when I was shot the blood ran into my eyes. He said nothing My house is made of bamboo, so I was shot at the window. It was dark outside and we had lights inside so the men could see me. This was between 7 and I was shot first in the neck. After I was hit in the neck I tried to roll away to avoid the three following shots.[62]

Gonzalez suspected that he was shot as a result of his unwillingness to publicly support local military efforts to stamp out the NPA:

I do not know who would have wanted to kill me, because I have no enemies around the village. I have no idea. There's no reason for me to be targeted by the military. No reason for me to be targeted by the NPA The military conducted a village meeting, and presented a paper saying that anyone who wants to kill an NPA should sign up the paper. When it was my time to sign, I told them "I will not accept the offer because I want a peaceful life for my two children."[63]

Although Nestor Gonzalezclaims that he never had any political affiliations with the left, his brother was a former member of the NPA, who had given up his arms in 1992, and local soldiers had been accusing the family of being NPA sympathizers.

Gonzalez's brother explained that Nestor and his family had been harassed by members of the military prior to the shooting. The brother explained:

Since May, when the military came to our village, the military were inviting and interrogating [members of the community]. Some of them were beaten by the military. These people invited for interrogation and beaten by the military, they reported to our family that we should take care because we were one of the targets of the military as suspected NPA. When I learned about this from my neighbors I fled from my [home] for Manila According to the neighbor interrogated by the military, [the military say that] our family are members of the NPA and that they would kill all of us. During the 1980s, I was a member of the NPA and I surrendered in 1992. The military knows that I was a "returnee". [But my brother] was never in the NPA, because he is a church person, involved in church work.[64]

Gonzalez'shome was about 100 meters from the nearest AFP outpost. It therefore seems unlikely that any other armed, uniformed individuals would have been able to be present in the area, discharge their weapon four times, and escape without being apprehended.

According to Gonzalez's brother, the local police unofficially conceded that the involvement of the military in the attempted murder was likely: "Based on police investigation, the suspects are the military based near [town names omitted]. Yes, the police told [our family] this based on their investigation. So the police advised us to file complaints against the military."[65]

Pastor Jemias Tinambacan

Pastor Malou Tinambacan described the attack that left her husband, Pastor Jemias Tinambacan, dead. Both were members of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP), a church involved in human rights and social justice projects that has led critics to charge that it is associated with left-wing causes and the NPA. Just past 5 o'clock on the afternoon of May 9, 2006, Malou and Jemias were driving out of the town of Lopez Jaena, Misamis Occidental, in Mindanao in a van, en route to Oroquieta to buy some printer ink. They were driving along an uphill road near the village of Mobod when they heard a bang. Jemias asked Malou: "Is that a blown tire?"[66]

As Malou was trying to look out a window to see what happened, two motorcycles approached the car. Two men were riding a red motorcycle, one man rode a blue motorcycle. At that moment, the van started weaving, went off the road, and struck a tree. She heard a series of shots and saw that Jemias was hit. Malou tried to duck from other shots and Jemias was leaning against her, wounded. As she lay in the well of the passenger side she heard one of the men say, "The woman is still alive."

"It all happened very fast. I touched my hair and found an empty shell there," Malou told Human Rights Watch.[67] Her scalp was lacerated by the shell and bleeding. Terrified, she tried to lay still. "I played as if I was dead. I laid down close to the door." She heard more shooting but then heard the sound of a bus approaching, slowing, and then the men speeding away on their motorcycles. People from the bus tried to help but, "I could see that Jemias was already dead."He died from four .45 caliber bullet wounds.

Malou recognized the three assailants. Two are brothers who lived on land owned and rented out by Jemias's family. One is a corporal in the Philippines army, according to Malou. She identified the third assailant as a former NPA rebel who now is known as a "military asset" a government informant.[68] She told Human Rights Watch she recognized him from "his voice."[69]Malou says that this man always called her "woman" at the church and called Jemias "man" as it was his way of telling the two apart instead of calling them each pastor.[70]

Malou believes the attack was motivated at least in part for political reasons. Reverend Jemias was active in local leftist politics as the provincial chairman of Bayan Muna and the executive director of an NGO called the Mission for Indigenous and Self Reliance People's Assistance (MIPSA), which organizes local people and conducts livelihood programs.[71] Several MIPSA members previously had been threatened by the military. In December 2005 a former MIPSA employee, a driver named Junico Halem, who also worked as a coordinator for Bayan Muna, was killed by two men riding on a motorcycle. That case has gone nowhere and his wife and daughters fled into hiding. The Tinambacan case is complicated by the couple's relationship to the suspects. According to Malou, one of the brothers had come recently to Jemias and asked for 30 thousand pesos (US$620) to pay debts related to the land. Jemias refused. One possible scenario is that given the ties of the assailants to the military, they perhaps were paid to do the killing.[72]

Pastor Andy Pawikan

Three eyewitnesses currently in hiding told Human Rights Watch of the involvement of soldiers in the death of Pastor Andy Pawikan, a member of the UCCP. After Pastor Pawikan led church services in Pantabangan, Nueva Ecija, on May 21, 2006, at about noon, Pawikan, his wife and 7-month-old daughter, along with three women from the church headed to the Pawikan home. They were stopped by a group of about 20 soldiers. The women, including Pawikan's wife, were allowed to proceed but the soldiers detained Pawikan, who was carrying the baby.[73]

After about 30 minutes, those who had just been with Pawikan heard "many" shots. They were too afraid to investigate. After some time a group of soldiers came and returned the child to Pawikan's mother-in-law. The baby was covered in blood but otherwise uninjured.

The next day people from the village went to the area where Pawikan had been detained and found his body. They had been afraid to go there earlier because of the military presence. When they arrived there were about 10 soldiers still in the area. These soldiers, who were from the locally based 48th Infantry Battalion, told the villagers Pawikan had fought the soldiers and they had no choice but to shoot him. The soldiers insisted they had no choice. Even if one accepts that the pastor could have posed any risk to the soldiers, the villagers question how the pastor could have fought the soldiers while holding his baby daughter.[74]

"Gloria Fabicon"

In 2006 "Gloria Fabicon" was found dead with multiple bullet wounds. Her sister said she had been under surveillance from the AFP at least three months prior to her killing:

Before the incident, my sister told me there was an invitation coming from the military men, and that she's included in a list of seven names written on a piece of white paper that these soldiers told the village captain that they are looking for They called a special meeting to confront the seven people on the [list]. My sister was number six Soldiers conducted a personal interview with each of them, in a home located in our town Allegedly [according to the military], the seven persons gave support to the NPA or are a member of the NPA. My sister denied this. [The military] were from outside. Outside combat control My sister asked my advice, and I advised my sister to consult the village captain in order to clear her name. But the village captain gave no response until now My sister was nervous when investigated by the military men.[75]

A local police officer working on this case confirmed that the victim's name had appeared on some sort of list by the military. According to this police officer, the police asked the local military to confirm whether the victim's name appeared on any list, and the military confirmed that it had, but claimed opaquely that it was a list used "only to verify her identity."[76]However, the victim had worked for a local rights organization that critics viewed as being affiliated with the insurgency, and her family and the organization were confident that her death was a result of the victim's work.

"Disappearance" of two women

Human Rights Watch met with a teenage boy in Central Luzon who witnessed the abduction of two women, Karen Empeno and Sherlyn Cadapan, who were conducting research sympathetic to farmers, and who are now considered to be victims of a forced disappearance. The boy described their abductors as "military men" because they were wearing camouflage fatigues, and because "They called each other 'Sir!' [and] it is only the military that have guns."[77] He told us:

Around 2 a.m I was asleep and I was awakened with [one of the women] screaming "Mother help me!" The military told us to go outside and I was tied up Six of the military men were wearing camouflage [fatigues], the rest [of the 15 men were wearing] civilian clothes, just like anyone else. T-shirts, shorts All of them had guns. The guns were carried in front, holding them. They were long guns. Black Everyone was quiet. Someone said "Sir, we already have the two [women]." The military tied me up like this [with hands behind my back], and picked me up by my collar [and carried me] outside of the house. The military carried me by the back of the neck. They used plastic straw to tie my hands They pushed me to lie down Outside were [the two women], carried outside of the house. The six men who were wearing uniforms came out. My father was also outside. My father was also tied up The military men asked us about our names. They asked [one of the women] and then [the other]. [The first woman] gave her name, and then [the second woman] gave her name After that they boarded the jeep. It was a stainless [steel colored] jeep. The jeep is very long no paint The jeep looks like a passenger jeepney A guy in civilian clothes was driving.[78]

Members of the women's families succeeded in getting the courts to issue a writ of habeas corpus against the military for the pair, but the military has denied having them in custody.

"Manuel Balani"

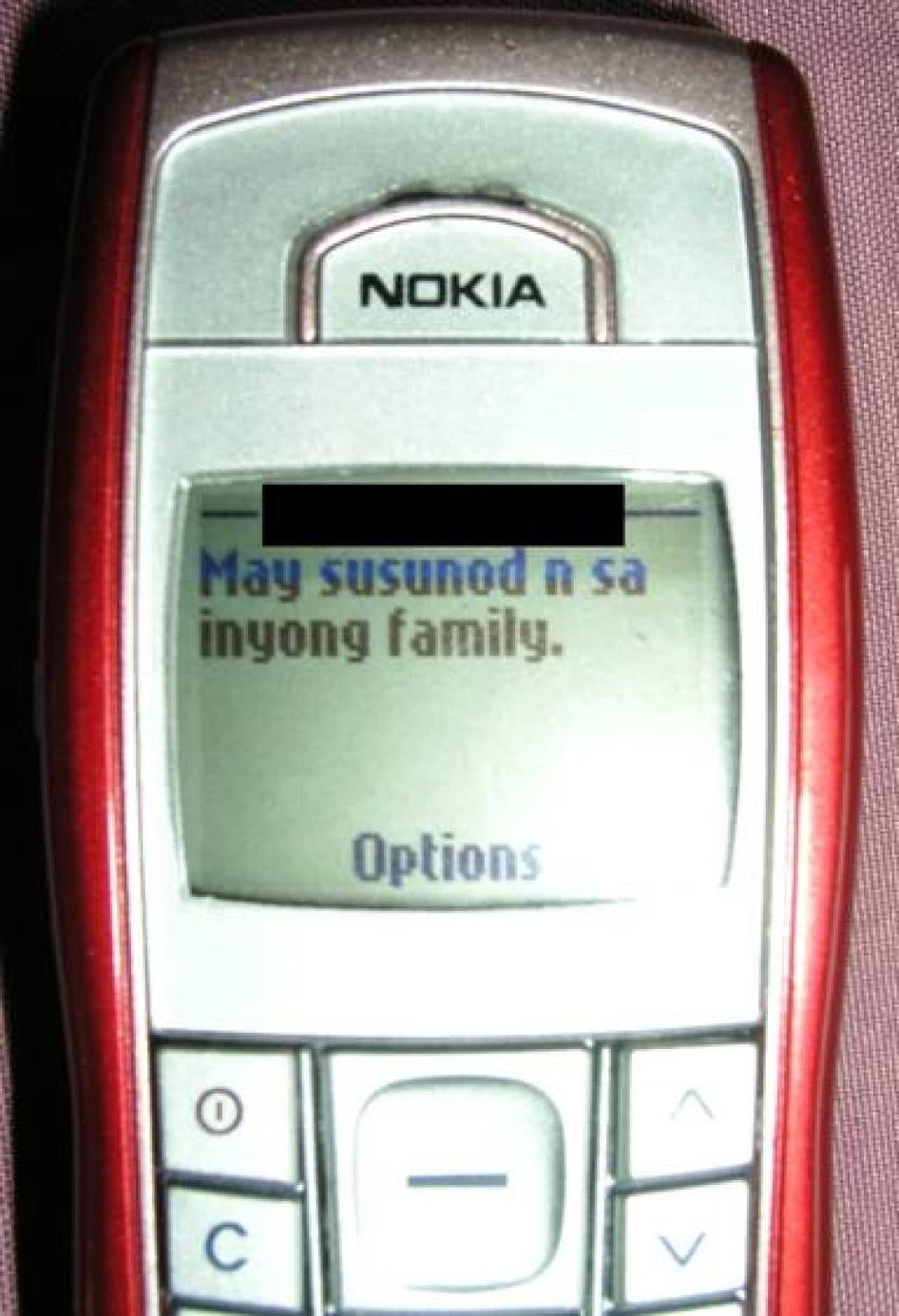

Military personnel may have been involved in the killing of "Manuel Balani," a local agrarian and anti-mining activist in late 2006. Remembering the morning before her husband was killed, Balani's widow told us:

Before [Manuel] went to his work, at 5 or 5:30 a.m., he received a text message [on his cell phone] that he has to watch out because there is a roaming military foot patrol [nearby]-armed people in uniforms I don't know who sent [the text], a friend of [Manuel's]. So I tried to convince [Manuel] not to report to work, but he received another text that the foot patrol was in an area higher up, further away from here, two kilometers from here. So [my husband] decided to report to work.[79]

The wife said that witnesses told her that her husband was stopped later that morning on his way to work by seven armed men in fatigues. They reportedly told her husband "You are the one who doesn't want the [mine] to open" and then shot him dead.[80] Human Rights Watch visited the location of the execution where an impromptu shrine for the victim had been built on the side of the road. Meters away, we found a tree containing a hole consistent with having been shot.

Danilo Hagosojos

Sixty-one-year old Danilo Hagosojos was riding home on his motorbike with his 7-year-old daughter who he had just picked up from school, when he was shot multiple times in the chest and head by two unidentified assailants, on July 19, 2006, in Sorsogon, in the Bicol region. Hagosojos had been a leftist activist during the rule of President Marcos and was a retired public school teacher who worked principally as a farmer during his retirement, but had also recently worked as a coordinator for a small NGO teaching literacy to rural adults.[81] Hagosojos was also an uncle to then-House Minority leader Francis Escudero and a cousin of then-Vice Governor Kruni Escudero, vocal critics of the Arroyo administration.[82]

According to the son of Danilo Hagosojos, the local police told him that they suspected the involvement of the military in the shooting of his father: "The police told me that the suspects are military, but that it is hard for them to go there because it is dangerous to investigate about the case."[83] Although Human Rights Watch was unable to get a comment from the local police on this case, the police investigation report notes that the shooting was perpetrated "by two men of skilled, clever, disciplined, patient and determined person and very careful in exposing their identity [sic]The commission of the crime shows that it is a well planned operation and the suspects are well versed in the [use] of firearms and very careful in exposing their identity [sic]."[84] The report also recommends that the case be "temporarily closed and be reopened upon the acquisition of material evidence."[85] As described in detail in the next chapter, police appear highly reluctant to follow leads that require investigation of the military.

Armando Javier

Armando Javier was a peasant rights activist and local coordinator for the party list group Anakpawis in near Cuyapo, Nueva Ecija, Central Luzon. On the evening of October 2, 2005, Armando and his wife Jocelyn were at home watching television. They lived in a simple home with a thatch roof and split bamboo walls. Around a hail of bullets filled the room. The police report says the assailant used an M16 assault rifle. Nine bullets hit Armando, and one grazed Jocelyn's shoulder.[86] When Human Rights Watch visited the Javier home a year after the shooting, the bullet holes were still visible in the wall.

Armando was a "rebel returnee"-having left the NPA in 1994 in order to marry Jocelyn. His name was on a list of supposed NPA sympathizers that was read off by soldiers who called villagers to meetings to inform them that their area was to be cleansed of communist influence. According to Armando's family, a detachment of soldiers camped nearby frequently called Armando for questioning, asking him to identify members of the NPA. Because of this attention, the family is certain that the military are responsible. Javier's mother told us: "He had no information and so he was killed."[87]

Attempted Killing of Roderick Abalde

Roderick Abalde, a coordinator for the Anakpawis political party in KidapawanCity, Mindanao, survived an apparently politically motivated murder attempt on May 7, 2006. He told Human Rights Watch:

I was inside the [Anakpawis] office with the Secretary General of Bayan We finished our talks around 9 p.m., and we were about to go to the office of Bayan to drop-off the Secretary-General of Bayan We were still in the compound of the Anakpawis office on our motorbikes, ready to start the engines, when we discovered that there was a white DT motorcycle going from the highway to the school, 100 to 200 meters from the office. Just a few meters in front of the school, they U-turned very quickly. We were about to start the engines and suddenly in front of my motorcycle, the persons on the white DT threw a grenade at us as he was going back to the highway Two people were on the motorbike. There was a driver wearing a helmet, but the rider behind had no helmet The motorcycle was about seven to 10 meters away, so I could not clearly see the [rider on the back of the bike's] face because he was moving very fast. The back rider threw the grenade. Both men wore a white shirt and jeans. The back driver wore a sleeveless shirt. The grenade landed behind my motorcycle. Three meters behind. I never saw the grenade when it was thrown. I only found out when it exploded. I thought it was just a stone. At first I didn't feel I was wounded. I tried to help my companion because I saw he had blood on his body. My companion was wounded in his stomach and his thigh. I didn't discover that I was wounded until I lost my energy when I saw someone coming to try and help me Shrapnel had entered my back and gone into my lungs. Our neighbor helped take us to the hospital I was awake, but had blurry sight. I was in a critical condition because of the shrapnel that penetrated my lung. The shrapnel had exactly struck [my right] lung, and the lung was starting to collapse Very painful. I was in the hospital for two weeks.[88]

Sotero Llamas

Three motorcycle-riding gunmen shot and killed Sotero Llamas, the former Bicol region commander of the NPA, while he was was riding in his car on the morning of May 29, 2006, through his home town of Tabaco City, in Albay province. His bodyguard was wounded in the attack.

As detailed later in this report, responsibility for the killing is unclear, but Llamas' history raises concerns of political motivations. Llamas joined the NPA in 1971, briefly surfaced from his underground life during the ceasefire of the Aquino administration, and then was captured and imprisoned in 1995 by government forces in Sorsogon province. Released in 1996 as part of resumed peace talks, Llamas spent six months as a political consultant for the peace process, before becoming a founding member and the director of internal affairs for the political party Bayan Muna.

In 2003 Llamas left Bayan Muna for health reasons and to spend more time with his family. Llamas made a run for governor in 2004 without the backing of the leftist parties. After the election in 2004, he was in the scrap metal business. His widow says that he was completely out of the NPA and retained no more connections with the underground movement, and had not since 2003. Even the local governor, who had run against Llamas in 2004, confirmed that Llamas was no longer associated with the underground movement.[89] In February 2006 Llamas was one of the 51 people whom the police accused of rebellion and insurrection and being involved in the conspiracy to overthrow the Arroyo administration.[90] A judge dismissed the charges, but state prosecutors subsequently re-filed the case, which was still pending at the time of his death.

League of Filipino Students (LFS) in Bicol

Two members of the left-wing League of Filipino Students (LFS) were gunned down in Bicol in March and July 2006 respectively, and a third was shot in February 2007. The LFS is a national student organization with international affiliated chapters. Although the motives behind the killings are uncertain, LFS members have long been targeted by the security forces for alleged links to the NPA.[91]