Paying the Price

Violations of the Rights of Children in Detention in Burundi

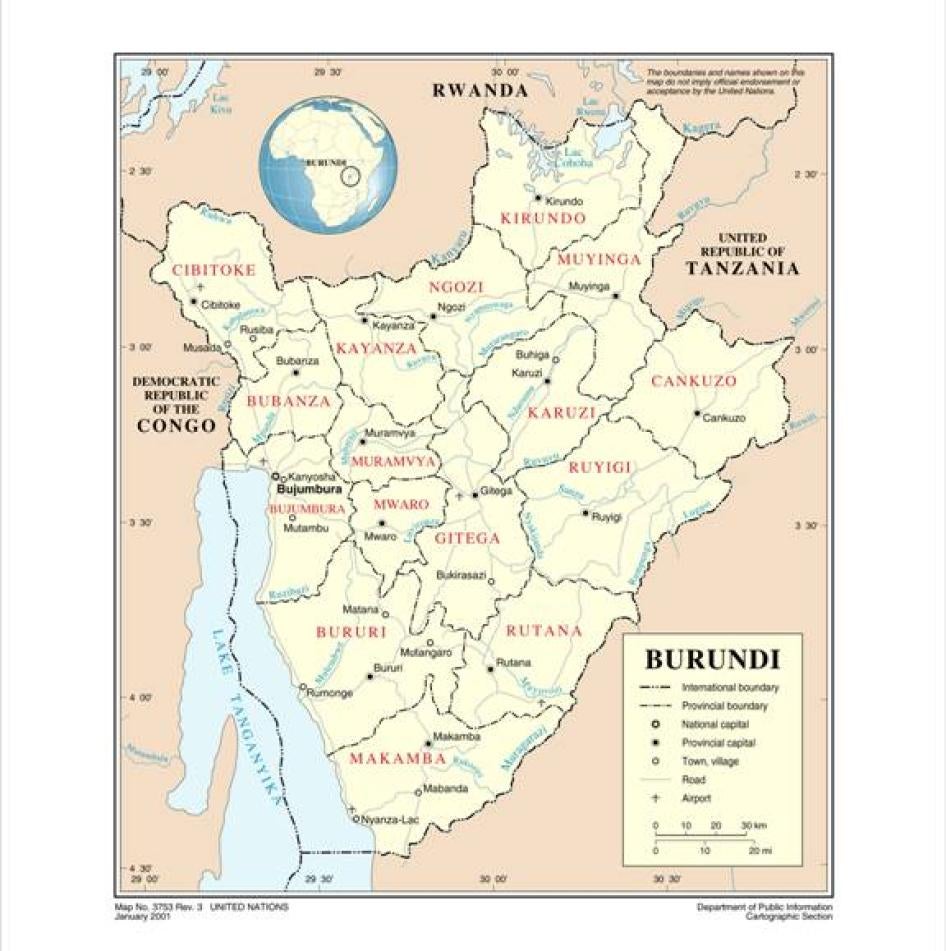

Map of Burundi

My problem here is that I feel very alone. I am lonely all the time. I come from far away, no one visits me. It has been a year since I have seen someone I know.

- Donatien C., 14 years-old, serving a ten-year sentence for rape, Gitega prison, May 23, 2006.

Sleeping is very hard, as there are about 27 of us in the one room. Some of us have to sit up all night. There are no separate showers and toilets for us, the children. It's bad for the kids when the adults are in the bathrooms. I check to see who is in there before going to shower.

- Jean-Bosco S., 14 years-old, accused of theft, Ruyigi prison, May 25, 2006.

It's like any other business in the prison. Some people traffic in cigarettes and some traffic in sex

- Alphonse N., 15 years-old, accused of rape, Muramvya prison, August 17, 2006.

I. Summary

At the end of 2006, just over 400 children between the ages of 13 and 18 were incarcerated in Burundian prisons, the majority of them awaiting trial. Countless more children were held in communal holding cells and police lock-ups, pending possible transfer to the prisons. In most regards children are treated as adults in both courtrooms and prisons and children's rights as guaranteed under international law are rarely respected.

There is no juvenile justice system in Burundi. The age of criminal responsibility is 13 and minors between 13 and 18 years old found guilty of a crime should benefit from a reduction in the sentence normally given to adults convicted of the same crime. There are no alternatives to incarceration for children and no services to help children once they are released from prison. In the end of 2006, more than 75 percent of detained children in Burundi were awaiting trial, many after months or even years of pre-trial detention. Some have been tortured to obtain confession. Most have no access to legal counsel.

Serious deficiencies in the judicial system affect all detainees in Burundi but fall particularly heavily on children who are entitled to special protection under international treaties ratified by Burundi. Children must be incarcerated only as a last resort and then, only for the shortest possible amount of time.

Prison conditions are deplorable for all prisoners in Burundi who lack space, adequate food, water, bedding and sanitary facilities. Insufficient food and lack of education particularly affect children, not just during their time of imprisonment but in years after. Contrary to standards in international law, children and adults are together for most of the day, leaving children vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse by adult prisoners.

The Burundian National Parliament is currently considering amendments to the criminal law, which if passed, fully implemented, and funded, would improve the treatment of children in conflict with the law. They would raise the age of criminal responsibility to 15 years old and would provide alternatives to incarceration for all children.

The Burundian government should adopt and promptly implement these amendments as they represent a necessary first step towards improving the protection of children in conflict with the law. However, other practical measures must also be taken to ensure full realization of the rights of the child as protected under international law. While some of these measures are not costly, donors should provide material and other support to assist the Burundian government in this effort.

II. Recommendations

To the Government of Burundi

- Adopt and implement fully and promptly the proposed new penal code, raising the age of criminal responsibility and establishing community-based alternatives for rehabilitating children in conflict with the law. Ensure that incarceration is a last resort and is imposed for the minimum possible time.

- Establish a child-focused juvenile justice system that will fully and promptly implement international law and standards regarding children in conflict with the law. Ensure that appropriate alternatives to remand in custody and custodial sentences are in place nationwide.

- Investigate and if appropriate prosecute or otherwise sanction persons accused of physically or sexually abusing detained children.

- Immediately release all children held on charges of rebel collaboration andwork with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) to provide them with appropriate services and follow-up care to reintegrate them into their communities.

- Ensure that children accused of crimes are brought promptly to trial.

- Ensure all children brought to trial are given free legal assistance.

- Provide access to primary school education for all children in prison.

- Establish a systemic social welfare mechanism for identifying and responding to children vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, including those who are at risk of coming into conflict with the law.

To United Nations (UN) Agencies working in Burundi, including the Integrated Office of the United Nations in Burundi (BINUB)

- Collaborate with the government in reforming the justice and prison systems as proposed by the Secretary General in his August 2006 report on the United Nations Operation in Burundi, including improving operation of the courts and reducing the time spent by detainees in pre-trial detention.

- Provide long-term assistance to the Burundian government in establishing a juvenile justice system, ensuring that UNICEF and/or other technically appropriate United Nations field agencies continue support after the end of the BINUB mandate.

- Ensure that members of the Human Rights Section of BINUB and the BINUB child protection officer continue to actively monitor the treatment of children within the justice system and report their findings publicly.

- UNICEF should support the government and work with civil society to ensure that all children have adequate legal help in all phases of judicial investigations.

- UNICEF should support the government and work with civil society to ensure that children released from prison have necessary support to reintegrate into their communities.

- UNICEF should use its considerable global experience in developing child soldier reintegration programs to support the release from prison of children arrested for being associated with the National Liberation Forces (Forces Nationales pour la Libration, FNL), the immediate removal from demobilization camps of other children associated with the FNL, and their inclusion in age and gender appropriate schemes supporting their reintegration to the community.

To International Donors

Donors should designate specific funds for juvenile justice reform, including:

- to help implement the proposed amendments to the penal code, if adopted.

- to ensure the nationwide availability of adequate alternative measures to remand in custody and custodial sentences for children.

- to ensure legal and other counsel to children in conflict with the law.

- train police and law enforcement personnel on the rights of the child and on the handling of juvenile justice cases.

- improve basic living conditions in all detention facilities where children are held, ensuring separation of minors from adults as required by international standards.

III. Methods

This report is based on interviews carried out by Human Rights Watch researchers between May 2006 and February 2007 with 112 children imprisoned in ten of the eleven prisons in Burundi. We also interviewed another 30 children, including children recently released from detention, others held at a demobilization center for former participants of the rebel group, the National Liberation Forces (Forces Nationales pour la Libration, FNL), children detained in police lock-ups and communal holding cells. Some parents of imprisoned children were also interviewed. Interviews were conducted in Kirundi and Kiswahili, with translation into French.

In addition, in conjunction with the Burundian Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detained People (APRODH), Human Rights Watch researchers questioned all the 136 children incarcerated in Mpimba central prison in Bujumbura between January 31 and February 2, 2007 about family background, level of education, work experience and access to legal assistance. Quantitative results presented in this study and in the annex are based on those 136 interviews.Children jailed at the central prison may not be representative of all children in prison, but little or no differences are expected in the profile of children jailed at Mpimba prison compared to other prisons in Burundi. The majority of children accused of involvement with the rebel group are held there so other prisons have a smaller percentage accused of that crime. The alleged crimes and physical conditions of those at Mpimba were generally similar to those found in the other prisons throughout the country. It is possible that children in Mpimba benefit from better access to legal assistance than those in other prisons because of the proximity to Bujumbura, where most lawyers are based.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed prosecutors, judges, and current and former members of the prison administration. We also spoke with child protection officers of United Nations Operations in Burundi (ONUB), Integrated Office of the United Nations in Burundi (BINUB), and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) as well as with representatives of local non-governmental organizations that currently provide legal and medical assistance in the prisons and jails.

In this report, we use "prison" to refer to the 11 government facilities so designated by the Burundian government and we use the word "child" to refer to anyone under the age of 18.[1] For their protection and in respect of their right to privacy, we use pseudonyms for children interviewed and for some interviews we omit the place or time of the interview.

IV. Background

Political context

In 2005 after more than a decade of civil war and a period of transition, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (Conseil national pour la dfense de la dmocratie-Forces pour la dfense de la dmocratie, CNDD-FDD) won parliamentary and local administrative elections. Pierre Nkurunziza of the CNDD-FDD, which had been the largest rebel group fighting the government, ran unopposed in the indirect election for the presidency.Nkurunziza took power promising that his government would be committed to human rights.[2]

A small rebel group, the National Liberation Forces (Forces Nationales pour la Libration, FNL) continued to wage armed conflict against government forces until September 7, 2006 when the government and the FNL signed a ceasefire agreement ending active hostilities in Burundi for the first time since 1993.[3] The implementation of that agreement was delayed and, at the time of writing, FNL fighters awaited demobilization.

With a per capita income of U.S. $90 per year, Burundi is one of the poorest countries in the world, its chronic poverty worsened by the years of war.[4] Floods and poor growing conditions caused food shortages in 2006, which were projected to continue into 2007, further stretching the resources of local communities.[5]

Children in conflict with the law

In Burundi, long-term pre-trial detention is a routine practice which the government has recognized as a structural problem in the justice system.[6] While provision for bail exists in law, during its research Human Rights Watch found no cases to indicate that children in practice benefited from this provision and in general, it appears that it is rarely used.[7] This leads to large numbers of prisoners awaiting trial mixed with those who have been convicted and causes overcrowding.According to government statistics, in the end of 2006, 318 of the 401 children in prison were facing trial but not yet convicted.[8]

According to government statistics, the number of children in prison increased by 180 percent in just over three years, from 143 in October 2003 to 401 in December 2006.[9]

Comparison of child prison population between October 2003 and December 2006 for each prison in Burundi[10]

Of the children incarcerated in Mpimba central prison in early February 2007 nearly 40 percent were charged with or had been convicted of theft, just over a quarter were charged with or had been convicted of rape and just under a quarterwere charged with or had been convictedof participation in armed groups. The remaining 11 percent were charged with or had been convicted of various crimes, including murder, attempted murder, drug possession and assault.[11]

No study has established why the number of children in detention appears to have increased, and whether it reflects a genuine underlying increase in juvenile crime or a more aggressive policing policy leading to more arrests.

A factor which one study on the related issue of street children captured was that the war had a "devastating impact" on children, leaving many "abandoned, orphaned, disabled and traumatized."[12]Many children in conflict with the law, like those on the street, have equally been negatively impacted by the war and some were in fact street children prior to incarceration.

The charges for which they were incarcerated according to the 136 children in Mpimba Central Prison in Bujumbura in January 2007 were as follows:

Table 1 Grounds for Arrest

Grounds for Arrest |

% |

(n) |

Rape |

25.7% |

(35) |

Theft |

39.7% |

(54) |

Participation in armed groups (FNL) |

23.5% |

(32) |

Other (murder, attempted murder, assault, drug possession, etc.) |

11.0% |

(15) |

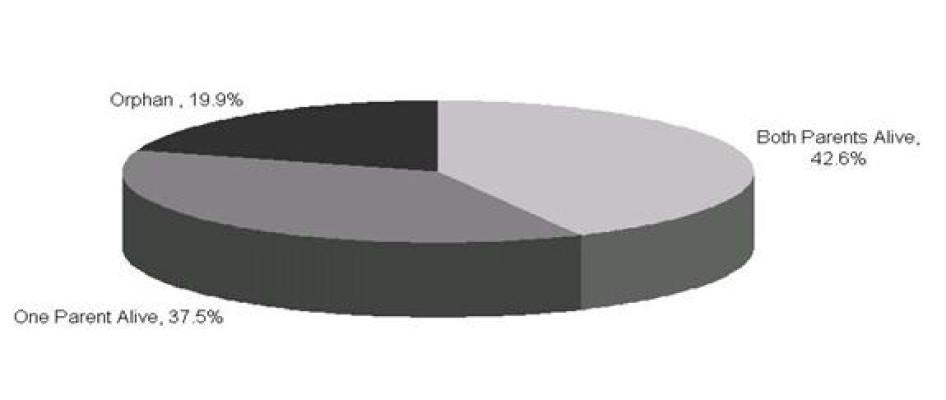

Orphans and child labor

UNICEF information indicates that an estimated 15 percent of the children in Burundi have lost one or both parents, the majority due to disease and war.[13] Within the research conducted by Human Rights Watch, the statistics indicate that the proportion of orphans is higher in prison than in the overall population, suggesting a potential correlation between the risk of a child coming in conflict with the law and facing prison and their status as an orphan as opposed to a child with both parents alive. Among the 136 children interviewed at Mpimba central prison, 78 of them or 57 percent had lost one or both parents. Almost 20 percent had lost both parents to either war or disease.[14] Many children in prison told stories of witnessing the deaths of their parents and struggling to survive afterwards. Other children said when a parent remarried they had been forced to leave home and moved onto the streets.

Table 2 Parental Status

Parental Status |

% |

(n) |

Both Parents Alive |

42.6% |

(58) |

One Parent Alive |

37.5% |

(51) |

Orphan |

19.9% |

(27) |

Some children themselves had been injured in attacks that had killed their parents. Several showed Human Rights Watch researchers scars of injuries they had received during such attacks. "My father was killed when I was ten years old," said Frederique N., who is now 16 years old. "It was 2000 and we were running to get to the border with Congo. I was holding my father's hand when he stepped on a mine. My father died, but I was just hit by the shrapnel."[15] He has not had surgery to remove the pieces of metal from his arms.

Many children forced to fend for themselves end by becoming domestic workers[16] or cattle or goat herders for the comparatively wealthy. Among the children surveyed at Mpimba central prison 30 percent (41 of 136) had been employed as domestics before being incarcerated, more than those who had been students, those doing other kinds of work, and the unemployed. Several said they had been falsely accused by employers who did not wish to pay their wages, an assessment borne out by an experienced Burundian human rights activist who said, "a lot of child domestics are falsely accused for rape and theft when their employers don't want to pay them. There are many irregularities in the cases of child domestics."[17] The vulnerability of child domestic workers has been well-documented in countries around the world.[18] These children work in relative invisibility for long hours, with little access to education.

Data from the 136 children interviewed in Mpimba Prison suggest that orphans work more frequently as domestics than other children: 41 percent of the orphans worked as domestics prior to incarceration compared to 29 percent among children with both parents alive and 26 percent among children with a single parent. In addition, 46 percent of those accused of rape worked as domestics prior to their incarceration, more than among any other type of occupation. The data further suggest that orphans were more frequently in jail as a result of having been accused of rape compared to the other groups.

Grounds for Arrest and Parental Status

According to several children, they were forced to drop out of school and leave their homes to find work after their parents died. Vital N., aged sixteen, said that he had left Muyinga province when his mother and father died from illness. "One day, I came back from the fields and [my mother] was there, dead on the floor," Vital said. He lived on the streets before finding work as a domestic. He worked for several months without receiving his salary, and when he asked to be paid, he was accused of rape by his employer.[19]

Gaspar, a 15 year-old, said that he dropped out of school when his family fled to Tanzania in 2001 because of the war. When he returned, he found work tending cattle. "I wanted to run away," said Gaspar. "My boss would beat me all the time, until I sometimes thought I would die and then he would refuse to pay my salary." One day when his employer was out, Gaspar stole 250,000 FBU (US$250) and tried to escape. He was quickly caught and beaten again. He gave back all the money and pled guilty and is now serving two years in prison for theft.[20]

Crimes related to the war

During the civil war all sides recruited children as combatants and support workers, giving thousands of children access to weapons and training in their use.[21]

Since the current government took office in September 2005, police and military have arrested hundreds of children on charges of participating in the FNL. Nearly a quarter of the children held at Mpimba central prison (31 of 136) and a score of others elsewhere in the country are accused of having participated in an armed group, the usual charge made for those said to have assisted the FNL.[22]

In addition to the dozens of children held in prisons, 26 others said to have participated in FNL ranks were held by the government in demobilization camps, first at Randa in Bubanza province and later in Gitega province.[23] According to the terms of the September 2006 ceasefire, a joint verification commission was to oversee cantonment and demobilization.[24] On February 19, 2007, this commission was put in place and began work on implementing the conditions of the ceasefire.[25]

On February 8, 2007 the press reported that the minister of national solidarity declared that all children accused of FNL participation would be released, but at the time of this writing, it had not occurred.[26]

With the war ending, some children were lured into the ranks of the FNL with the promise of getting easy money through the demobilization program.Bonaventure N., currently held on charges of participating in armed groups said:

I thought about the FNL for a long time because of the extreme poverty of my family. I didn't want to fight. A guy came here and said that since [FNL leader] Rwasa is near signing [a peace accord], we should all go join because our lives would change if we got the money. But, we were arrested before we could join.[27]

In another case, disappointed members of the government-sponsored militia, the "guardians of the peace", said resentment over not receiving anticipated demobilization payments led them to commit a crime.Louis H. and several others had expected to receive a payment of US$100 promised to the "guardians of peace." When the person drawing up the list of beneficiaries failed to include them, they stole clothes from him. "Everyone was being paid, but us," Louis told Human Rights Watch, "so we decided to steal clothes from his house. But we got caught."[28] He has been sentenced to three years for theft.

Former combatants, including children, still in possession of firearms have committed theft and other crimes, which has generated a general suspicion that all persons with firearms may have committed crimes. For example, one 14-year-old awaiting trial told Human Rights Watch researchers that he was wrongly accused of armed robbery simply because he had tried to hand in his Kalashnikov to a military post shortly after four former combatants had been arrested for theft in the area. A rebel combatant since the age of nine, the child had been recruited by force after his mother died of illness and his father had been killed in an attack.[29]

V. Failings in the Criminal and Penitential Systems

Children in Burundi are dealt with in exactly the same system as adults.The age of criminal responsibility in Burundi is 13 years old, and there are no separate courts or criminal laws specifically for children.[30] The sole provisions currently made for offenders under the age of 18 years old relate to sentencing, where a child is to be sentenced to no more than half the sentence of an adult convicted of the same crime. In addition, children cannot be sentenced to death or to life without parole, but instead are to be imprisoned for a maximum of ten years.[31] Aside from these provisions, children accused of crimes in Burundi are treated in the same manner as adults under the law.

Burundi's criminal justice system as a whole faces serious problems with its basic capacity to effectively prosecute cases.One prosecutor explained to HumanRights Watch researchers that prosecutors must handle too many cases with too few resources and no transportation to cover the large geographic areas for which they are responsible.He added that prosecutors are required by regulation to close[32] investigations of 15 cases per month.[33]Another prosecutor commented, "Sometimes we have to close cases without all the elements of the crime established. It's become more important to close 15 cases than to complete cases with quality investigations. We are overworked."[34] He added that thejudicial police officers (OPJ) often have done poor work in investigating cases and need training on investigation techniques.[35]

Cases that therefore get to trial are often poorly prepared:evidence is lacking, witnesses are missing, or the charges are poorly drawn.Lack of preparation in a case can lead to postponement of hearings meaning that defendants find themselves subject to further periods of pre-trial detention. [36] For those cases that do proceed, poor presentation of the prosecution's case, and particularly the absence of legal representation, makes it difficult for child defendants, as with adult defendants, to effectively participate in the trials, to understand and challenge the evidence, or even to contest a forced confession.

In addition to problems of competence and resources, the judicial and police systems are hampered by corruption. In June 2006 the Minister of Justice admitted that corruption existed in the judicial system and called for reforms to restore its credibility.[37]Burundians who express little faith in the magistrates and the police accuse them particularly of taking bribes to arrest persons against whom there is little or no evidence.

In the case of children, allegations frequently surface that children are falsely accused of crimes as a consequence of other personal disputes that they may be involved in. In the case of Leon T, for example, a 14-year-old orphan accused of rape, he said that since the death of his parents, neighbors had been making false accusations against him in an effort to remove him and his younger siblings from their land.[38]Human Rights Watch was able to examine his file, and indeed the case against the boy was based solely on a statement from the father of the alleged victim, although he made clear that he was not in the vicinity when the rape was alleged to have happened. There was no other evidence to suggest that any sexual interaction between Leon and the alleged victim had taken place at all.[39] Similarly Celestin K. (see further below) was accused of raping the daughter of a neighbor who had been in conflict with his family over land.[40]

Ill treatment and forced confessions

Several children in prison told Human Rights Watch researchers of having been beaten and forced to confess while being held in lock-ups and jails before arriving at the prison. There are police lock-ups and holding cells on some hills or in local zones, in most communes, and in all provincial capitals.[41]In most cases, detained persons are held locally until the investigation files relating to the charges against them are completed and are then transferred to the nearest prison.

Burundian Criminal Procedure Code specifies that when confessions of guilt have been obtained under duress, they are null and void.[42]The Supreme Court of Burundi has also confirmed the principle that a conviction cannot be secured solely on the basis of a confession alone, especially if obtained before trial and retracted before the court, but must be corroborated by other evidence.[43]

Children, especially those originally from Cankuzo and Karuzi provinces, told Human Rights Watch researchers that they had been intimidated, threatened, beaten with batons and metal bars while in police lock-ups before being transferred to the prison. Some had been told that if they admitted their crimes they would be released, but of course that was not the case. Children interviewed by Human Rights Watch researchers who had not had access to legal assistance did not know that it was possible to retract a confession nor how to do so.

Celestin K. told Human Rights Watch researchers that he was arrested and accused of raping the daughter of his neighbor in 2003, when he was 13 years old. He spent a week in the communal police lock-up, insisting on his innocence. The parents of the alleged victim had been in conflict with his family over land and he felt this explained why they had accused him. The administrateur, the local official in charge of his commune, came and threatened to beat him with a metal bar if he did not admit the rape. When the boy refused, the official beat him with the bar on the upper arms and shoulders. "I was in so much pain, I finally admitted it so they would stop hitting me," Celestin said. "It hurt so much I couldn't eat for a few days afterwards."[44] He was not brought to trial until February 2006 and when Human Rights Watch researchers met with him in May 2006 he still did not know the verdict in his case.

Fourteen-year-old Pacifique N., who had been accused of raping his cousin, told Human Rights Watch researchers that he had been tied up by members of the community and taken to see the mushingantahe, the respected person customarily called onto settle local disputes.When the mushingantahe tried to release the boy for lack of evidence, the father of the alleged victim took him to the police. The officer of the judicial police (OPJ) then told the boy to remove his clothes and lie down on the floor of the jail. The OPJ hit Pacifique on the back and legs periodically over a three-day period while telling him that he should admit his crime. Pacifique said that he found it difficult to respond to the questions while being hit and that he never got a chance to explain his side of the story. He eventually admitted to the rape and has been trying to retract that confession, but does not know how.[45] When he informed the prosecutor of his wish to retract, he was told to await his day in court.

According to Pierre-Claver Mbonimpa, founder and president of the Burundian Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detained Persons (APRODH), mistreatment of detainees in police lock-ups and holding cells by police and administrative officials is an ongoing problem:

At the provincial capitals, where human rights organizations and the United Nations conduct monitoring visits regularly, there are fewer cases, but in the lock-ups in the interior of the country, further from these areas, there are many more cases.[46]

Delays in the justice system

The Ministry of Justice has noted that in many cases the period of detention is excessive and that the slowness of the judicial system is one of the gravest obstacles to effective justice in Burundi.[47]Under Burundian criminal procedure, a person may be detained by judicial police for one week, extendable to two weeks in cases of "unavoidable delay" (sauf prorogation indispensable), and then must be charged or released.[48] However Human Rights Watch research strongly suggests that this is not the experience of many children in detention. Most children we spoke to had been held in police custody for months before being charged. Pierre R. from Cankuzo province was accused of theft and spent two months in a holding cell before being brought to the prison in Ruyigi.[49] Gilbert N., a sixteen year old accused of being a member of the FNL was held in two holding cells, one in Kayanza province and one in Ngozi province for a total of over four months, before being transferred to the Ngozi prison.[50]

Once in the prison system, the child is very likely to remain in detention until his trial commences. Burundian law does provide for bail, but in practice, the provision is rarely used and children without lawyers are often not aware that bail is a legal option.[51] Most defendants are kept in remand long-term until the court can organize a trial date.

The government noted the problem of long-term remand while analyzing information from 2003, reporting that "it takes an unreasonably long time before cases actually come to trial and the number of remand prisoners (60 percent of the total) is far greater than that of convicted prisoners (40 percent)."[52] This situation appears to have become even worse since 2003. According to government statistics, in the end of 2006, 318 of the 401 children in prison were on remandalmost 80 percentsome after months of pre-trial detention. [53]

One prison director told Human Rights Watch researchers that because many children are accused of minor infractions, such as stealing food or small sums of money, their cases are not given priority. As a result, many spend months in prison even though they may be found innocent, have their cases ultimately dismissed or if convicted given a short sentence. The prison director knew of instances in which the sentence received was shorter than the time the child had spent awaiting trial and a verdict.[54]

Athanase N., a 15-year-old boy, was charged with theft and assault. After the death of his father, he had fought with his older brother about what to plant in their fields.When the older brother planted potatoes, Athanase pulled up the potatoes and planted sorghum.[55] He was arrested in February 2005 for the alleged theft of the potatoes and assault on his brother but not brought to trial until August 2006, and was also awaiting a verdict.

Pasteur H., 15 years old, told Human Rights Watch researchers that he admitted to killing his grandfather accidentally when they were drunk on umunanasi, an illegal alcoholic drink. Despite admitting his crime to the police, he spent six weeks in the jail at his commune and then six more weeks at the jail in Cankuzo before being taken to prison in Ruyigi.[56] Two years after his arrest, he was finally given a hearing and sentenced to five years in prison.

One factor in the long delays in bringing cases involving serious offences to trial is the infrequency of sessions held by the 17 courts of first instance with the jurisdiction to try serious criminal cases.[57] Such court sessions are especially rare in the seven provinces where there is no prison and where organizing the transport of prisoners, witnesses, judges and prosecutors demands logistical planning, vehicles and money for fuel. Local non-government organizations assist as many courts as they can, by providing transport and other services, including lawyers for some victims and defendants but their funds are not sufficient to assure prompt trials throughout the entire country. In Mwaro province, for example, there were no criminal hearings from January 2005 to October 2006 so that a person arrested in January 2005 would have to wait 22 months for disposition of his case.[58]

The lack of adequate preparation by police and prosecutors, mentioned above, also contributes to delays in bringing the accused to trial.

The delays in the judicial system affect children after trial as well, with some children reporting that they waited months without news of the verdict. Other child prisoners suffer unnecessarily long incarceration because the government fails to release prisoners when they become eligible for parole. Under Burundian criminal law, prisoners including children are eligible for parole once they have served a quarter of their sentence.[59]In March 2006, the government acknowledged that of 2,573 prisoners proposed for parole, only 758, or approximately one-third, were actually granted it, in spite of the overcrowding in the prisons."[60] Some children in prison did not understand parole procedures. Those who did never failed to ask Human Rights Watch researchers why they had not been released even though they had served a quarter of their sentences and been recommended for release by the directors of the prisons where they were held.[61]Questioned about these cases by Human Rights Watch researchers, most prison directors responded that they had complied with the procedures and recommended the children for release but that the officials at the Ministry of Justice with the power to act had failed to respond.[62]

Violations of the right to counsel and ability to prepare a defense

Most children in conflict with the law in Burundi have no access to a lawyer or are not provided with legal assistance. According to information collected in Mpimba central prison in Bujumbura in early February 2007, over 86 percent of the children said that they had never received legal assistance of any kind since being detained. The remaining 14 percent had a lawyer provided by a non-governmental organization present during court hearings.[63]

Children, who usually have little schooling and do not understand legal procedures, are particularly affected by lack of legal assistance in trying to deal with the police and the judicial system. Donatien C., a cattle herder when he was accused of raping a two-year-old girl, told Human Rights Watch researchers:

I am not smart. I have never been to school in my whole life. When we got to court, I didn't know what was happening. A lawyer was there, and he told me to plead guilty. I was afraid I could get the death sentence, so I pleaded guilty and then I was sentenced to ten years in prison. I have never seen the lawyer again. I don't know if I can appeal. I don't know what to do now.[64]

Some NGOs provide limited legal assistance to indigent defendants but often the assistance is available only for the day of the hearing. The lawyer has no time to build a relationship of trust with the child, nor does he ordinarily have the time or the funds to investigate the case, prepare and meet with witnesses or challenge evidence.Because of insufficient resources to help all the accused, one large NGO project gives assistance as a priority to cases involving torture and sexual violence.[65] Children who are accused of petty theft or being a member of the rebel FNL rarely receive any legal assistance at all.[66]

This lack of legal assistance makes it virtually impossible for children to file appeals and to press for redress or suppression of evidence in cases of torture or mistreatment by police.With no reliable professional advice, children are left to rely on the prison gossip as the only source of information.

Eric K., accused of rape, might have grounds for appealing his conviction but decided not to do so. He told Human Rights Watch researchers:

I was just sentenced to two years in prison, even though I am innocent. I had a lawyer but I only saw her once. I pleaded not guilty and there were no witnesses against me. I didn't appeal the decision. People here say that I can make my life worse if I appeal the decision. And if the appeal takes a long time, I would have to stay here and wait and maybe that will take longer than my sentence. I only have 14 months left, so I will just wait.[67]

Data from Mpimba Prison indeed suggest that among the children, those accused of rape were 6.5 times more likely to see a lawyer, compared to those accused of theft. Those accused of rape were also 16.1 times more likely to see a lawyer than those accused of being rebels, most likely because there haven't been trials for alleged FNL members, and no organization has been providing them with legal counseling.

Grounds for Arrest and Legal Assistance

VI. Conditions of Incarceration

There are 11 prisons in ten of the 17 provinces in Burundi and over one-hundred police lock-ups and communal holding cells throughout the country. [68]According to the Director of Penitentiary Affairs, as of December 31, 2006, the prison system in Burundi was operating at more than double capacity,with the largest prison, Mpimba central prison in Bujumbura, holding over three times its intended capacity. Four-hundred-one of the total 8336 prisoners in the country were minors between the ages of 13 and 18 years old.[69] Over 300 children are currently awaiting trial while only 83 have been convicted.[70]

There are no separate prisons for children and during the day children mingle with adult prisoners. Detainees who have not been tried are housed with those who have been convicted.

Seven provinces have no prison facilities, imposing an added burden on persons imprisoned from those provinces.[71] Held far from their families, they rarely receive visits and do not receive the occasional gifts of food and clothing relied on by other prisoners to supplement the meager rations provided by the prisons.This lack of moral and material support weighs particularly heavily on children imprisoned far from home.

All detention facilities in Burundi are extremely overcrowded. According to one child imprisoned in 2005, he was at that time housed in a room for minors with one other boy and one adult. In mid-2006, he shared the same room with 17 other boys.[72]

|

Prisons provide food, but little else. Most prisoners arrange for themselves other material necessities such as mattresses, bed covers, and cooking utensils. They often have only one set of clothes. There are no formal educational opportunities and, in most prisons, there are no organized activities other than chapel services.[73]

Most prisons in Burundi are organized around a large rectangular courtyard with rooms of varying size around three sides of the yard.[74] Most have a small common room area used for religious services and informal classes taught by educated adult prisoners. All prisons have at least one watertap, but in some cases itoperates during limited hours. There is a communal kitchen in each prison, but most prisoners cook and re-heat their own food, filling the courtyards withthick black smoke that makes breathing difficult for all in the vicinity. Prison directors told Human Rights Watch researchers that they recognize that smoke inhalation may be detrimental to health of the prisoners.[75]

Within prison walls, an adult male prisoner is chosen by each prison director to manage most aspects of life. Known as the "General," this prisoner is the de-facto overall leader of the prison population and the representative of the prisoners.There are also chiefs of each room, usually chosen by the room members but occasionally chosen by the General.[76]Such persons exercise great control over the conditions of life of other prisoners with the General designating room assignments and occasionally doling out punishments for misconduct to prisoners, while the chief is often charged with distributing food rations and collecting money to buy light bulbs or candles or other supplies. Chiefs may control access to privileges, such as desirable sleeping space, which they may sell to others.

In some prisons visited in 2006, older children were chiefs of rooms where children slept but in other cases adults had this role.[77] Jean-Claude K. was selected by other boys to be the chief of their room when he was 16 years old. He is now 20. He continued to serve as chief of the minors' rooms despite having become an adult. Jean-Claude K. said:

I am responsible for closing the minors' area at 10 p.m. and opening the area at 6 a.m. When a new minor arrives, we ask him for money to pay for things like light bulbs. If he doesn't have money, we let him in, but we wait until he receives a visit from someone and then ask for the money.[78]

Violation of the right to dignity and hygiene

As a result of severe overcrowding, some children lacked adequate or appropriate space for sleeping. At Ruyigi prison, Jean-Bosco S. told Human Rights Watch researchers, "Sleeping is very hard, as there are about 27 of us in one room. Some of us have to sit up all night."[79]In at least six prisons visited by Human Rights Watch researchers in 2006, they lacked money to "buy" the rights to better sleeping arrangements.[80] Some had been forced to sleep outside the minors' room in the courtyard. [81]

In Muyinga prison, Ferdinand S. who is an orphan said that he has been forced to sleep outside in the courtyard, with about 13 other minors, because he does not have the 2000 FBU (US$2) to pay for a place inside the room for minors. "I don't have any blankets or a mattress but I have a military jacket that I use as a cover," said Ferdinand S.[82] Pascal N., in the same prison, said that he had managed to negotiate the price of 500 FBU (US$.50) to sleep on the cement floor in the minors' room, where there were about nine other children. He has made a mattress out of plastic bags stuffed with grass. He had only been able to pay the money because his father had brought it to him on a visit.[83]

In Bubanza prison, children said they are required to pay 1000 FBU (US$1) to sleep on a natural mattress made of grass in the juveniles' room, but that for 5000 FBU (US$5) they could sleep on the beds made of suspended planks of wood. "There are 13 children in my room," said Gabriel M., who is accused of stealing a goat from a neighbor. "There are five who can afford to sleep on the planks and the rest of us are on the floor."[84] In Ngozi prison, the children said that there were empty beds in the minors' room, but according to Benoit N., "unless you pay money, you cannot touch them."[85]

Some children purchased mattresses from prisoners about to be released. Prices varied from one prison to the next among those visited by Human Rights Watch researchers but in all cases the amount was much more than most children could afford. Several children said that they sold part or all of their daily food ration to secure a sleeping space in the rooms for children.[86]

Human Rights Watch researchers found at least one water point available in all prisons visited, but found no water available in many of the rooms where children slept.Once the doors are closed for the curfew, children in these rooms cannot get water to drink. Several children asked Human Rights Watch researchers for bottles or a bucket so that they could collect and store water to drink during the night.[87]

In all the prisons visited by Human Rights Watch researchers, children showed the researchers bug bites and skin rashes, presumably the result of unhygienic conditions.[88] Children who slept outside as well as many who slept inside buildings were exposed to mosquito bites, a circumstance that increased the likelihood of contracting malaria.The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has provided prisons with mosquito nets, but some children said they had sold them to purchase food.

The ICRC conducts regular visits to the prisons and holding cells throughout Burundi, though they do not provide first aid or direct medical care to prisoners. ICRC officers liaise with nurses in the prisons to encourage and maintain acceptable standards in the prisons and draw particular cases they find to the attention of the prison authorities. In 2006, ICRC paid the bills for medications purchased by the pharmacies located inside the prisons, hence ensuring access to medicines for prisoners. This program ended in December 2006 and it is now the responsibility of the prison administration.[89] The prison administration is also required to pay for medical care of seriously ill or wounded prisoners, which involves sending the prisoner to a local hospital. Human Rights Watch found one case in 2006 where a sixteen-year-old former FNL combatant had been shot in the hip during a skirmish with government forces the year before. He had never been treated for his injury and showed signs of infection extending from his hip to his knee and lower leg.[90] His surgery was eventually paid for by a local non-government organization (NGO).

Lack of separation from adults

Under pressure from NGOs to comply with international law and the Burundian constitution regarding separate quarters for children, Burundian prison authorities began a few years ago to establish separate sleeping facilities for minors at most prisons.[91] In each of the ten prisons visited by Human Rights Watch researchers in 2006, there was at least one room designated as a sleeping area for children, but segregation at night was not consistently enforced.

During daytime hours, from roughly 6 a.m. to 5 p.m., children are in contact with adult prisoners in most prisons, leaving them vulnerable to abuse. Children frequently told Human Rights Watch researchers that they feared adult prisoners. Daniel N., who has been awaiting trial for theft of his neighbor's green beans for two years, said that he had recently been hit by an adult prisoner with a large piece of wood. "He was drunk and angry when he hit me and he got really aggressive. I tried to just get away but he hit me and part of the wood went into my eye," he said.[92] Human Rights Watch researchers observed that his eye was bloodied and infected and a visiting nurse confirmed the nature of his injuries.

Some children said that they had become adept at avoiding confrontation and keeping to themselves. Innocent N., a 16-year-old, said "Adults look to do things to us sometimes. When we are eating, adults will come by and hit us or steal our food. I think that hitting us makes them feel better."[93] Gaspar N., a 15-year-old accused of theft who had served as a child soldier [in the FNL], told Human Rights Watch:

Some adults are really mean to us here. The big criminals, you just have to stay away from them, if you can. Those who are on death row, they threaten us sometimes. They don't hurt us everyday, but they will hit you.[94]

Even after separate sleeping quarters were established, prison authorities continued on some occasions and for different reasons to permit adults to share sleeping space with children.

In Bubanza prison in 2006, lack of space made it impossible to assign all children to separate sleeping quarters. There was one room exclusively for children but another room where adults and children slept together. Lambert N., once a child soldier for the FNL, said that when he arrived at the prison, he asked to sleep in the minors' room, but "the General" told him there was no space and he would have to wait.[95] He has since turned 18 years old.

In Ruyigi prison, the director told Human Rights Watch researchers that he placed some of the oldest adults in the children's room in order to provide guidance and oversight. "I put five older men in the room with the minors. This way they have a father figure in the prison with them," he said.[96]

In another prison, Raphael N., a 15-year-old boy, told Human Rights Watch researchers that he had admitted participating in a plot led by three adults to kill his father. Because of the gravity of the crime, he was assigned to adult sleeping quarters, in the same room as others accused in the same case. After he testified against the adults in court, they threatened to kill him during the night. When Raphael N. told prison authorities about the threats, he was reassigned to the minors' room.[97]

In Muramvya prison Patrick H., who was accused of trying to escape, was assigned by "the General" to the adults' sleeping area. Patrick told Human Rights Watch researchers that he was often harassed by the adult prisoners and that was forced to wash their clothes to avoid having problems with them.[98]

In distinction to the above cases where prison authorities knew of and permitted the shared sleeping arrangements, there were other cases where authorities were unaware that adults were entering the children's quarters without permission. At Rutana prison, children told Human Rights Watch researchers that an adult sometimes sneaked into the children's room just before curfew and spent the night soliciting sex from the boys. When the researchers raised the issue with a prison administrator, he said he was unaware of the problem but would investigate it.[99]

Even in prisons where children sleep separately, they must sometimes share toilets and showers with the adults. In Ruyigi, the prison director told Human Rights Watch researchers that male prisoners were locked in their quarters from 11:30 am to 2pm to allow female prisoners to use the one shower in the prison but according to the children, there were no such arrangements to allow children exclusive use of the facilities.[100] "There are no separate showers and toilets for us, the children," said Jean-Bosco S. "It's bad for the kids when the adults are in the bathrooms. I check to see who is in there before going to shower."[101]

Sexual violence and prostitution

Although even consensual sexual relations between males are socially regarded as unacceptable in Burundi, dozens of child prisoners nonetheless described forced or coerced sexual activity, including between men and boys, in the prison.[102] At least a few children in every prison visited by Human Rights Watch said they had either been offered money, food, alcohol or drugs by a male adult prisoner in exchange for sexual services or that they knew someone who had accepted money or other benefits for such services.Emmanuel H. said that two adult prisoners at Bururi prison were known to give boys marijuana in exchange for sexual services. He claimed that prison authorities knew this but did not punish the offenders.[103]

A 15-year-old boy accused of stealing manioc from a field, told Human Rights Watch researchers that he had been approached by two male prisoners seeking sexual services. "I really need to buy a plate and a pot so I can eat, but I don't want to have sex for those things, because it's wrong."[104]

Abdoul N., a 16-year-old boy who had been sentenced to ten years of imprisonment for rape, said:

When the adult prisoners get some money, they come to us looking for sex. They try to get us to go with them to the showers or to the areas around the chapel. I know it is not right, so I don't accept, but there are others who do. When they are caught, the minor is sent to sleep with the adults for a few days.[105]

Some boys told Human Rights Watch researchers that they knew of instances in which boys had been raped, but very few admitted to being victims themselves.Adolph M., currently serving a five-year prison sentence for stealing US$150, told Human Rights Watch researchers that he had been raped three times as a 17-year-old in Rutana prison. He said:

The first time, I was in the shower, which was very small. An adult came in. He just forced himself on me. He was much bigger than me, so I couldn't do anything and I was in pain. I was too afraid and too ashamed to tell anyone and he kept coming back to me. I never told anyone in the prison administration. I still have pain in my kidneys and in my stomach. I have diarrhea a lot.[106]

When asked about the problem of sexual violence and prostitution in the prisons, both the former and current Directors of Penitentiary Affairs admitted awareness of these problems and said that they had never heard of a case in which someone was prosecuted for rape or for soliciting sex with minors while incarcerated.[107]

Lack of proper food and nutrition

Like too many Burundians, imprisoned children told Human Rights Watch researchers that they were hungry. Food supplied to children in Burundian prisons is insufficient both in total calories and in nutritional value, a particularly serious concern given the crucial growth that occurs during adolescence.[108] Children inadequately nourished during these years of development can never undo the effects of long periods of poor nutrition.

The problem of food is most severe at the holding cells and police lock-ups where authorities do not feed detainees. Family and friends are supposed to provide food to those detained in such places but many detainees are severely malnourished, particularly if they spend a long period in the lock-up.[109]Orphans and street children, who cannot rely on support from home, generally survive on food shared with them by other detainees or food occasionally provided by religious groups or NGOs. Adrien N., 16 years old, accused of rape, spent two weeks in a holding cell without food. When summoned by a police officer for interrogation, he was too exhausted to respond. "I told him that it would be better to kill me," said Adrien, "than to send me back [to the cell] without food."[110]

Once transferred to prison, children receive the same food rations as adults, 350 grams of beans and 350 grams of manioc flour per day.[111] They are also supposed to receive small rations of salt and palm oil, but according to the children interviewed, such foods were not frequently distributed. Some children said they had occasionally not received any food at all because the prisoners responsible for distribution had not apportioned the food correctly or had taken more than their fair share.[112] Prisoners can receive extra food or other supplies from family or friends who visit, but among the children interviewed, few were so fortunate as to be able to count on such supplements.

According to the prisoners, the beans are ordinarily insufficiently cooked and require further cooking to be digestible and the manioc flour also must be cooked to be eaten. Cooking food requires having or borrowing a pot and finding charcoal or bits of wood for fuel. Several children told Human Rights Watch researchers that they worked for adult prisoners, cooking their food and washing their clothes, in exchange for having the use of their pots and part of their fuel.[113]

Juvenal C., 14 years old, had recently been released from the central prison when he spoke to us. His story was typical of the many children Human Rights Watch interviewed. He told us, "I had problems of dizziness and being tired all the time from the lack of food in prison. I would just sit on the floor and feel awful. I wouldn't always get the same ration as the others. I had to sell some food to cook the rest of the food."[114]

Lack of access to education

While campaigning for the presidency in 2005, candidate Pierre Nkurunziza promised free primary school education for all Burundian children.[115] Once elected, he kept that promise for the general population, even though it entailed serious logistical problems for a system strained by the arrival of massive numbers of new students.[116]Praised for this important reform,[117] President Nkurunziza has unfortunately not delivered the same opportunities to children in prison. All children have a right to education, including free primary education.[118]

According to information provided by the 136 children incarcerated at Mpimba central prison in early February 2007, only nine had stayed in school beyond sixth grade before their arrest. Twenty percent had never been to school at all.[119] Many of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch researchers voiced a strong desire to learn something during their time in prison. Unable to help themselves or their families by earning money, the children see this time in prison as the time to learn, but prisons offer no formal opportunities for education. In some prisons, adult prisoners have organized informal classes in reading, math, and French.

One 13-year-old in Gitega prison said that he asked adults to teach him what they had learned in school. He had never been to school because since he was very young, he had worked as a herder earning a salary of 4000 FBU (US $4) per month. He found a prisoner willing to teach him to read the Bible which did not satisfy the child. He said, "I want to learn to write, but he will only teach me the words of God."[120]

VII. Recent Government Action

The draft penal law

At the time of writing, proposed amendments to the criminal law, already approved by the council of ministers, were before the Burundian parliament. Prepared by Burundian legal experts in conjunction with staff of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the proposed amendments are meant to address inequalities and gaps in the current penal law which dates from 1981.[121]

The proposed amendments make some substantial changes to the treatment of children in conflict with the law. They would raise the age of criminal responsibility from 13 to 15 years old and would reduce the prison sentences for those between the ages of 15 and 18 to a quarter of the sentence of an adult convicted of the same crime.[122] Most importantly, the proposed amendments create alternatives to incarceration in prisons, such as the possibility of placing children in conflict with the law in foster families or in specialized institutions. They require that a child sentenced to a year or less in prison must instead perform community service, the nature of which would be determined by a judge considering the age and social context of the child.[123]

Should it be passed, the amendments could represent a significant step forward in addressing the problem of children in conflict with the law in Burundi. Changes to the law, however, are only the first step. Effective implementation of provisions like those for alternatives to prison is required. Specialized institutions would have to be established as would services to locate and supervise foster families and to monitor conditions of the community service. These would require considerable donor support.

Presidential initiatives to release prisoners

The president recently announced two measures to reduce overcrowding in prisons and to deal with excessive time spent in pre-trial detention. On December 22, 2006 President Nkurunziza ordered the release of several categories of prisoners, including those who had been convicted and sentenced for crimes committed when they were younger than 15 years old.[124]

This measure will affect a relatively small number of children since only 83 of the 401 children in prison in December 2006 had been brought to trial and not all of them for crimes committed when they were younger than 15 years old.[125] The Ministry of Justice established a commission to compile a list of qualifying prisoners but it is not known how or when the children will be released.[126]

In a second measure announced on December 31, 2006 the president directed judicial authorities to identify prisoners held in pre-trial detention for long periods of time in violation of the law. In a New Year's speech to the nation, he said that these prisoners would be granted provisional liberty while awaiting trial.[127] The minister of justice subsequently indicated that persons accused of violent crimes, such as murder, rape and armed robbery, would be excluded from this measure.[128]At the time of writing, judicial officials were identifying eligible prisoners and releases were expected to begin imminently.[129]

The second measure will end the illegal detention of some persons, children as well as adults, held long beyond the limits prescribed by law. It should also reduce overcrowding in the prisons and thus at least marginally improve conditions of incarceration. The extent of any improvement will depend at least in part on the number of persons newly arrested and detained. According to the data gathered by one local organization, in 2005, authorities released 2796 prisoners but by the end of the year they had detained another 2568, significantly eroding the improvements resulting from the earlier release.[130]

Important measures in themselves, these two initiatives do not address the violations of children's rights which regularly occur in the justice system nor do they provide the systematic reform of the justice system needed to meet international standards for juvenile justice.

VIII. International Support for Prisons and Justice

Given the importance of international assistance in funding change in Burundi, it is clear that international support for improvements in the justice and prison systems will be a necessary-though not sufficient-condition for reform. Donors have promised assistance in improving conditions in Burundian prisons, with some US$1.47 million earmarked in December 2006 for electrical systems, water and sanitation systems, and structural improvements.[131] Donors will also pay to equip prisons with plates, drinking glasses, mattresses, uniforms and bed covers for 8000 prisoners and to provide increased food rations for children, women and sick prisoners for twelve months.[132]

Improvements to the physical condition of prisons are necessary but will not in themselves resolve the problem of providing safe and separate quarters for children where they are allowed supervised interactions with adults for education or religious purposes.The provision of new equipment and increased food rations should improve the conditions of life for children in prison but only if appropriate measures are taken to ensure that other prisoners do not deprive them of the intended benefits. It should also be noted that food supplements are provided only for one year and that rations will return to prior levels unless a new source of support is found.

The United Nations' role

In an addendum to the seventh report on the United Nations Operations in Burundi (ONUB),[133] the Secretary General outlined plans and goals for the new Integrated Office of the United Nations in Burundi (BINUB) that was scheduled to begin work on January 1, 2007. The Secretary General recommended that a human rights and justice section of up to 20 international personnel monitor, investigate and report on the human rights situation in Burundi, facilitate the development of a national human rights action plan and address legal and justice sector reform, including corrections and juvenile justice."[134]

It will be crucial for the UN to support the government of Burundi in the important areas of justice and prison reform. Providing experts to assist the government in developing a comprehensive juvenile justice system would be one immediate and practical way to offer such support.

IX. National and International Legal Standards on Children in Conflict with the Law

Burundian and international standards recognize that children in conflict with the law are a particularly vulnerable group, entitled to specialized protections within the justice system. The Burundian constitution recognizes that all children have the right to special protections, because of their vulnerability.[135] According to Article 46 of the constitution, children must be detained for the shortest amount of time possible and if detained must be separated from anyone over 16 years of age.[136]

In February 2007, the Committee on the Rights of the Child issued a General Comment reaffirming and making more specific previously stated guidelines and requirements on the treatment of children in conflict with the law.[137] These new guidelines reinforce many of the points which Burundi must address, such as standards for defendants' rights and timing of pre-trial detention, to establish a juvenile justice system in the best interests of children. Burundi is already in compliance with the recommendations of the Committee regarding establishing a minimal age of criminal responsibility which is older than twelve years and in outlawing the death penalty for minors.

Burundi has ratified the principal international treaties that protect the basic and fundamental human rights of children in conflict with the law: the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC),[138] the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),[139] the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR),[140] and the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, (Convention Against Torture).[141]Burundi is also party to the regional African [Banjul] Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights (African Charter) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC).[142]

Safeguards in detention

Torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment

The prohibition under international law on torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment is absolute. [143] As well as being a matter of customary international law, and prohibited by the ICCPR, the Convention against Torture (CAT) explicitly prohibits torture at all times and under all circumstances.[144]The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights also prohibits torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment[145]and the Burundian constitution provides for similar prohibitions.[146]

State parties to CAT undertake to adopt "effective legislative, administrative, judicial or other measures to prevent" torture.[147]Under Article 15 of CAT, Burundi is required to "ensure that any statement which is established to have been made as a result of torture shall not be invoked as evidence in any proceedings, except against a person accused of torture as evidence that the statement was made."[148]

Specifically in relation to children, both CRC and ACRWC place explicit duty on the state to ensure children are protected from torture, or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.[149]

The beatings and sexual violence to which children in detention are exposed and subjected present serious violations of Burundi's obligations to protect children from torture and other prohibited treatment.

Conditions of incarceration

International standards require that children deprived of their liberty "have the right to facilities and services that meet all the requirements of health and human dignity."[150] The UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (UN Rules), as well as the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, set forth detailed specifications of the conditions under which children may be confined.[151] They entitle children to basic standards of health, sanitationincluding clean and sufficient beddingand nutrition.[152] Both the ICCPR and the CRC mandate the separation of children from adults in detention.[153] The CRC and the ACRWC also specifically require states to take extra measures to protect children from sexual abuse, exploitation, and coercion.[154] Conditions in Burundian prisons and lock-ups are far below these recognized international standards themselves meant to represent the minimum conditions of detention.

Length of detention

Although the HRC has stated in a case involving adults that detention for prolonged periods of time does not in and of itself constitute cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, it has qualified this statement by saying that this conclusion is valid only "in the absence of some further compelling circumstances."[155] The CRC was enacted "[b]earing in mind the need to extend particular care to the child . . . by reason of his physical and mental immaturity . . . [and to provide] special safeguards and care, including appropriate legal protection . . . ."[156]The detainees' status as children-a group that has been identified as particularly vulnerable-may qualify as compelling circumstances that would render prolonged pretrial detention, particularly in conditions which deny them adequate access to food, health care and education, a form of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

Due process

The CRC requires states parties to establish specialized "laws, procedures, authorities, and institutions" for children in conflict with the law.[157]Burundi has not yet done so, although, if adopted, the proposed law now before parliament would partially meet this requirement.Whether or not states have a juvenile justice system, they have a clear duty to ensure that the due process guarantees required under international human rights law are implemented for all children accused of crimes. Children accused of crimes have a right not to be detained arbitrarily or subject to other forms of unlawful detention.[158] Children also have the right to the basic guarantees of a fair trial, including the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty, to be informed promptly and directly of the charges against them, to have prompt access to legal and other appropriate assistance, and to have their cases heard without delay.[159] Imprisonment of children should be a last resort and should be kept to the minimum period possible.[160] The primary objective in placing children in an institution should be to provide them "care, protection, education, and vocational skills," that will enable them to return to their communities and play a productive role."[161] Burundian authorities have so far failed to ensure that these rights are consistently implemented for children in conflict with the law.

Prolonged pretrial detention

Pre-trial detention typically involves two stages. The initial period of detention when a person is arrested on suspicion of having committed an offence, and then if the person is charged with an offence following arrest, the accused may have to spend time in detention on remand awaiting trial.

In relation to the first pre-charge detention period, the ICCPR requires that anyone arrested be "be brought promptly before a judge or other officer authorized by law to exercise judicial power".[162]The Human Rights Committee has interpreted the term "promptly" to mean that delays in bringing detainees before an impartial judge must not exceed a few days.[163]

After an accused has been brought before an appropriate judicial officer, human rights law requires that trial be held within a reasonable time, so that pre-trial detention is kept as short as possible.[164] This is particularly true where the accused is a child and Burundi has specific obligations to ensure that any pretrial detention of children is of the shortest possible period of time.[165] The ACRWC requires that for children facing criminal charges that all matters be "determined as speedily as possible."[166]The prolonged pre-trial detention of children in Burundi violates the obligations set out not only in the ICCPR, but also in the CRC and the ACRWC.[167]

The CRC, the ICCPR, and the African Charter all prohibit arbitrary detention.[168] According to the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, detention can be considered arbitrary "[w]hen the total or partial non-observance of the international norms relating to the right to a fair trial, spelled out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the relevant international instruments accepted by the States concerned, is of such gravity as to give the deprivation of liberty an arbitrary character." Burundi has accepted international norms related to the right to a fair trial as specified in the ICCPR and the African Charter, requiring access to trial within a reasonable time. The CRC and ACRWC set an even higher standard-the former requiring that pretrial detention be limited to the "shortest appropriate period of time."[169]Burundi's pretrial detention of children may so far exceed the "reasonable time" and "shortest appropriate period" standards as to violate the prohibition on arbitrary detention.

Right to counsel

There are no provisions for court appointed lawyers in Burundian law, despite Burundi having ratified the ICCPR that requires access to free legal counsel for those without means.[170] International treaties obligate Burundi to provide legal assistance to children facing criminal charges.The CRC establishes that "every child deprived of his or her liberty shall have the right to prompt access to legal and other appropriate assistance."[171]Burundi is obligated to ensure that this right is respected for every child, not only for those who can afford to pay for it.[172] Regional treaties to which Burundi is a party also create the duty to provide legal representation for juveniles.Article 17 of the ACRWC states that every child accused of a crime "shall be afforded legal and other appropriate assistance in the preparation and presentation of his defense" without discrimination based on "fortune . . . or other status."[173]

A central goal of the criminal justice system in relation to children in conflict with the law should be to provide them the chance for rehabilitation. The ICCPR is explicit that in the case of minors facing a criminal prosecution, the process has to take into account "the desirability of promoting [the minor's] rehabilitation."[174]The Human Rights Committee has explained that "convicted juvenile offenders shall be subject to a penitentiary system that . . . is appropriate to their age and legal status, the aim being to foster reformation and social rehabilitation."[175]Children must have access to courts and legal counsel for Burundi to ensure the rights guaranteed by the ICCPR and CRC.[176]

Although Burundi is a poor nation, the protection of the right to counsel is not contingent on the economic circumstances of a state.The ICCPR is clear in requiring states "to take the necessary steps . . . to adopt such legislative or other measures as may be necessary to give effect to the rights recognized in the . . . Covenant."[177]As the Human Rights Committee has said, "A failure to comply with this obligation cannot be justified by reference to political, social, cultural or economic considerations within the State."[178]

Access to fundamental rights in detention

Right to food

Children, including those in prison, have special nutritional needs and international law recognizes as a fundamental right, an entitlement of children to have access to food to satisfy those needs.International legal instruments require Burundi to ensure the right to food and to meet the nutritional needs of children. The ICESCR provides that the right to food involves first and foremost the right to be "free from hunger."[179] The Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights has defined adequate food as food available "in a quantity and quality sufficient to satisfy the dietary needs of individuals, free from adverse substances, and acceptable within a given culture."[180] When individuals are unable to enjoy the right to adequate food by the means at their disposal, states must fulfill that right directly.[181]Prisoners cannot earn a living nor provide for their own nutritional needs and thus fall into this category.The ICESCR requires Burundi to meet a prisoner's dietary needs, which the Committee has defined as "a mix of nutrients for physical and mental growth, development and maintenance."[182]

The CRC and the ACRWC require states to ensure that children reach the best attainable level of health, including physical and mental growth, through the provision of food and clean drinking-water.[183]

Right to education

The right to education is set forth in the CRC, the ICESCR, and ACRWC. Each of these treaties specifies that primary education must be compulsory and available free to all.[184] Secondary education, including vocational education, must be "available and accessible to every child," with the progressive introduction of free secondary education.[185]In addition, the ICCPR requires that juvenile offenders, "be accorded treatment appropriate to their age and legal status."[186]Detainees of school age, like all children, should have access to education.ICCPR guarantees each child the right to "such measures of protection as are required by his status as a minor," a provision that the Human Rights Committee has interpreted to include education sufficient to enable each child to develop his or her capacities and enjoy civil and political rights.[187]

Under article 26 of the ICCPR, Burundi is obligated to respect the entitlement of every person "without discrimination to the equal protection of the law." In addition, the Convention against Discrimination in Education prohibits any discrimination, exclusion, limitation or preference which, being based on race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, economic condition or birth, has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing equality of treatment in education and in particular . . . [o]f depriving any person or group of persons of access to education of any type.[188]