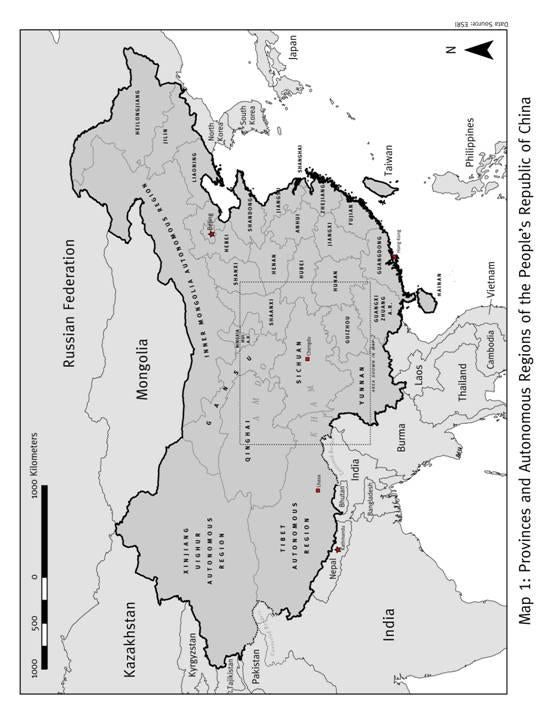

Map 1: Provinces and Autonomous Regions of the People's Republic of China

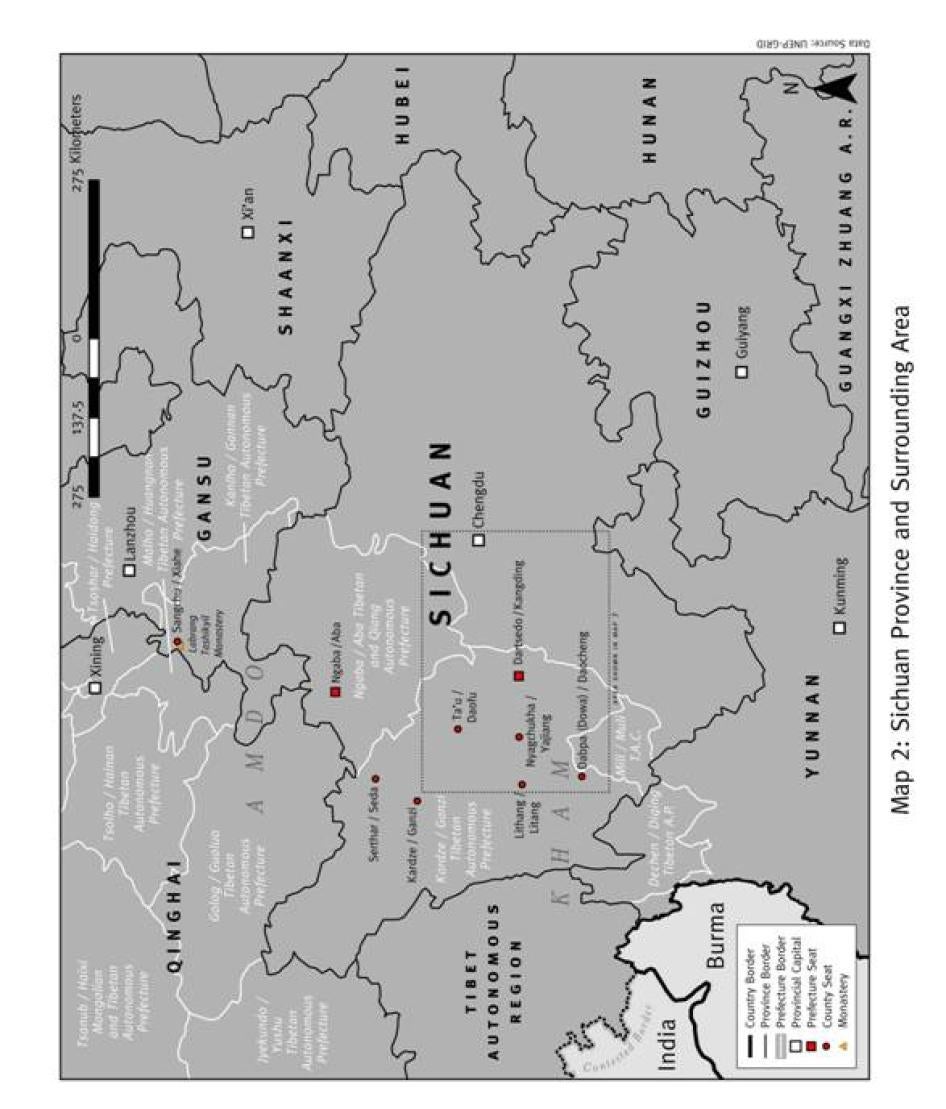

Map2: Sichuan Province and Surrounding Areas

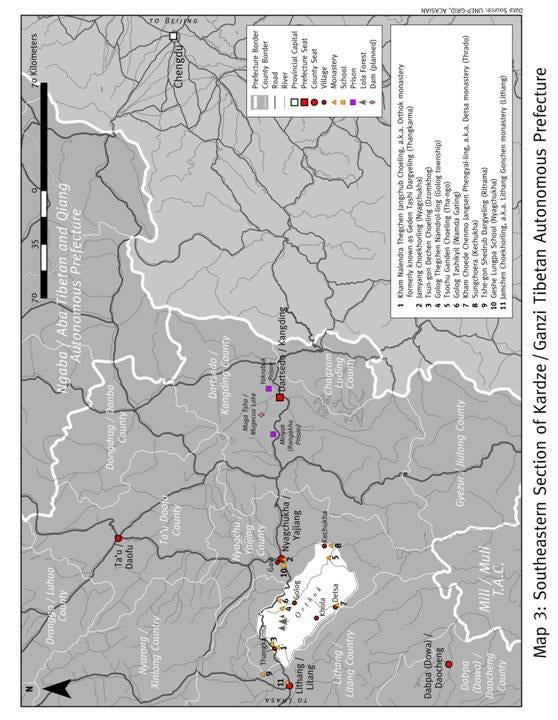

Map 3: Southeastern Section of Kardze/Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture

I. Summary

On December 2, 2002, the Kardze (Ganzi in Chinese) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture Intermediate People's Court in Sichuan province sentenced Tenzin Delek Rinpoche, a locally well-known and respected lama, to death. Tenzin Delek, charged with "causing explosions [and] inciting the separation of the state" was granted a two-year suspension of his death sentence, and remains in prison at this writing. His alleged co-conspirator, Lobsang Dondrup, was also found guilty, and was summarily executed on January 26, 2003.

The prosecutions came after a series of bombings in western Sichuan province between 1998 and 2002. A report issued the same day by Xinhua, China's official news agency, alleged that the two had "engaged in crimes of terror."[1] At the sentencing hearing, Tenzin Delek declared his innocence. In a tape smuggled from detention in mid-January 2003 and obtained by Human Rights Watch, he repeated this claim, saying, "I have been wrongly accused. I have always said we should not so much as raise a hand against another."[2]

Based on interviews with numerous eyewitnesses, the report provides a detailed account of the circumstances surrounding Tenzin Delek's arrest and conviction. It concludes that the case was the culmination of a decade-long effort by Chinese authorities to curb his efforts to foster Tibetan Buddhism, his support for the Dalai Lama as a religious leader, and his work to develop Tibetan social and cultural institutions. His efforts had become a focal point for Tibetans struggling to retain their cultural identity in the face of China's restrictive policies and its continuing persecution of individuals attempting to push the accepted boundaries of cultural and social expression.

The report also includes a detailed account of Tenzin Delek's life and work, and of his interactions with local officials on a range of religious and social matters, illuminating rarely seen aspects of life for Tibetans in areas outside the TAR. It shows that though Tenzin Delek adopted a moderate approach, regularly interacting with Chinese officials on behalf of local Tibetan populations, he also criticized local officials when he felt they were unresponsive or misguided and was steadfast in his loyalty to the Dalai Lama as a religious leader. Appendices to the report include several original source materials, including a translation of a lengthy statement made by Tenzin Delek in 2000, as well as the transcript of a Radio Free Asia interview with one of the sentencing judges.

More than a year after the court made known its verdicts against Tenzin Delek and Lobsang Dondrup, many reasons remain for questioning its findings and those of the review court or courts that upheld the original sentences. The trial was procedurally flawed, the court was neither independent nor impartial, and the defendants were denied access to independent legal counsel. Lawyers chosen by members of Tenzin Delek's family were not permitted to defend him at his appeal hearing. Claiming that state secrets were involved, Chinese authorities still refuse to release any of the evidence presented at trial.

Informed local sources maintain that local officials would not have been able to arrest and convict Tenzin Delek without first forcing a "confession" from his alleged co-conspirator Lobsang Dondrup, who allegedly named Tenzin Delek as his partner in the planning and financing of the bombings. Spectators present in court report that Lobsang Dondrup recanted his confession during the sentencing hearing.

Many of Tenzin Delek's associates, under surveillance for years, were rounded up in the wake of his arrest. At least two men are still in custody: Tashi Phuntsog, a monk, reportedly received a seven-year sentence, while a local resident named Taphel is serving a five-year term. Tserang Dondrup, a local resident, also received a five-year term but was released after serving only thirteen months.There are credible reports that all three were seriously mistreated when being apprehended and in detention. There have been no official statements about their alleged crimes. Nothing is known about their trials or the evidence presented.

Many other Tibetans have been detained, questioned, and subjected to threats or surveillance as part of the Chinese government's response to the bombings. Human Rights Watch has learned that approximately sixty Tibetans were detained for periods ranging from a few days to several months. Many were close associates of Tenzin Delek. Three have already served out administrative sentences and remain under strict surveillance. At least four Tibetans have disappeared and over one hundred others, fearful of arrest, have fled the community. One monk was so frightened by persistent questioning that he left the monkhood. Local inhabitants report having been warned that they or their families risked officially-sanctioned reprisals if they spoke publicly about the trials, their admiration for Tenzin Delek, or, for those who had been jailed or imprisoned, their treatment while incarcerated.

Throughout his monastic career, Tenzin Delek championed the economic, social, cultural, and spiritual aspirations of Tibetans in four counties of the Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (TAP), a predominantly Tibetan area in Sichuan province. He believed Chinese government officials in the area had little inclination to address Tibetan needs, preferring instead to use their positions for personal gain. Tenzin Delek tried to address the needs of Tibetans in a variety of ways: he established schools, clinics, an orphanage, and old-age homes. He mediated economic conflicts between Tibetan communities and was active in efforts to preserve the area's fragile ecological balance from deforestation, excessive mining, and other potentially damaging projects. He built a permanent structure at a major monastic center which previously had depended on tents for shelter, and he expanded its geographic reach through the establishment of seven branch monasteries. Perhaps most threatening to the authorities, Tenzin Delek's efforts attracted a coterie of several hundred devoted disciples and widespread support among local people at a time the Chinese government was consolidating its control of Tibetan areas and struggling to diminish monastic influence and reinforce secular authority.

Many Tibetans once resident in the predominately Tibetan populated counties of Nyagchu (Yajiang in Chinese) and Lithang (Litang in Chinese), in Tenzin Delek's home base in Kardze, and in several other nearby areas, spoke to Human Rights Watch at great risk to themselves. Their accounts yield insights into the breadth of the projects Tenzin Delek undertook to improve the lives of nomads and subsistence agriculturalists and to revive Tibetan Buddhism in an area where it had been silenced for more than a decade.

Over a twenty-five-year period, as Tenzin Delek's local status rose and he successfully challenged official policies on a number of issues, local authorities in the Kardze TAP came to perceive him as a threat and sanctioned progressively harsher measures to contain his social and cultural activities. By 1997, as a renewed campaign (labeled the "patriotic education" drive) to bring Tibetan monasteries under full government control extended eastward from the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) to Tibetan areas in Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, and Yunnan provinces, Kardze officials moved decisively. A first step was to label many of his activities political and, therefore, forbidden. His religious activities were curtailed. He could no longer move about freely. He could not speak publicly about the Dalai Lama as he could earlier. By 2000, Kardze prefecture authorities stripped him of all his religious prerogatives. Two years later, in 2002, he was formally arrested on what appear to be trumped-up bombing charges.

Though reliable information is scarce, Human Rights Watch is concerned that the Chinese government's treatment of Tenzin Delek is not an isolated phenomenon. As detailed below, there have been other major attempts in the Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture to control religious expression, monastic influence, local community leadership, and what officials view as political dissent.

Recommendations

Human Rights Watch urges the Chinese government to:

·immediately release Tenzin Delek Rinpoche pending a new trial conducted in accordance with international due process standards, including rights of access to counsel, adequate time and facilities to prepare a defense, and an open trial permitting international observers;

·immediately release all others arbitrarily arrested and detained in connection with the Tenzin Delek affair, including Tashi Phuntsog and Lobsang Taphel;

·publish all the Tenzin Delek/Lobsang Dondrup court (trial and appeal) documents and all relevant evidence, including materials submitted to the Supreme Court for review;

·publish the charges and evidence against all those still imprisoned or detained and those who served out their sentences or were released early;

·immediately suspend all restrictions on the civil liberties of those released;

·authorize a credible, independent investigation into the arrest and trial of Tenzin Delek and Lobsang Dondrup and publicize the results. If China cannot conduct such an investigation, it should invite the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions or an independent panel of jurists to do so.

·discipline or prosecute as appropriate officials responsible for violations of the rights of Tenzin Delek, Lobsang Dondrup, and others connected to the Tenzin Delek affair;

·offer protection and support for any individuals wrongly detained, imprisoned, tortured, mistreated, accused, or otherwise abused as part of the Tenzin Delek affair and allow such individuals to file administrative or judicial complaints against responsible government agencies and officials;

·allow access to the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture in order that he may visit China on terms consistent with his mandate;

·revise the Criminal Procedure Law to ensure that information obtained through torture or under duress is excluded as evidence in a court of law;

·end the practice of holding secret or closed trials or appeals. Allow family members, journalists, and independent observers to attend all court proceedings;

·end the prosecution of individuals for communicating with journalists, including international journalists, and human rights organizations;

·ensure that "ethnic…minorities…shall not be denied the right, in community withother members of their group, to enjoy their own culture [and] to profess and practice their own religion," as stipulated in Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); and

·abolish reeducation through labor, an inherently arbitrary system which denies due process and a court hearing to those deprived of their liberty.

In addition, Human Rights Watch urges the international community to raise the cases of Tenzin Delek Rinpoche and all others detained, arrested, or sentenced in relation to the crackdown in the Kardze (Ganzi) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture at all bilateral human rights dialogues and high-level diplomatic meetings.

A Note on Methodology

In preparing this report, Human Rights Watch spoke with nearly 150 Tibetans in many different countries, many of whom fled their homes after Tenzin Delek was seized. Forty-seven of the 150 were interviewed in depth. Some interviews were conducted in person, while others were done by telephone. Some interviewees recorded answers to follow-up questions and submitted tapes. In order to protect their identities and so as not to further endanger them or members of their families, some of whom already are under surveillance, the location of the person at the time of the interview is not noted in the report. Interviews were conducted in English or Tibetan and recorded when possible. The entire transcript was then translated into English. Interviews began in December 2002and continued into December2003. Secondary source materials supplemented the interviews.

According to those willing to speak on the record, the flow of information has been inhibited by a general climate of fear in the affected areas, an increase in the number of security officers present in the affected communities, an initial upsurge in detentions, and warnings from authorities to the public to avoid speaking about the cases. Interviewees told us that at least some monks did not dare to go to Nyagchukha, the Nyagchu county seat, in their robes. Villagers knew they were not to congregate in groups. Former prisoners knew that speaking out about their prison experiences meant they "would be brought back to prison again."[3] There were reports that local Tibetan officials knew their phones were tapped, apparently because they were suspected of sympathy for imprisoned political prisoners and to the monastic community. Associates of Tenzin Delek knew their movements were tracked. Relatives of those involved kept quiet. They reported officials banned their use of fax machines, on making long distance telephone calls, and on traveling.[4]

A note on names as used in this report: Chinese authorities convert Tibetan names to Chinese characters. Pronunciation of the characters differs from that of the Tibetan. To complicate matters, the Chinese characters are then romanized. Tenzin Delek, whose lay name was A-ngag Tashi becomes A'an Zhaxi. Lobsang Dondrup becomes Lorang Dengzhu.

II. Introduction

If questioned, a Chinese government official would not say that Tenzin Delek Rinpoche[5] lived in Tibet. For Chinese authorities and most ethnicChinese speakers in China, the term Tibet is reserved for the Tibet Autonomous Region, the part of the Tibetan plateau over which the Dalai Lama ruled at the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. Tibetans, on the other hand, often use the term to refer to a larger, Tibetan area which includes the TAR and Tibetan areas in four neighboring provinces, the northeastern part of which they refer to as Amdo and the eastern and southeastern part as Kham. China recognizes most of the Tibetan-inhabited areas as Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures or Tibetan Autonomous Counties, but by no means regards them as part of Tibet.Most of the Tibetan areas in Sichuan are parts of what Tibetans call Kham. Inhabitants of the area, such as Tenzin Delek, are known as Khampas.

More than 50 percent of ethnic Tibetans live outside the TAR in so-called autonomous prefectures and counties created by the Chinese government after 1949 and assigned to the jurisdiction of one of four provinces: Qinghai, Yunnan, Gansu, and Sichuan. This dispersal of Tibetan population clusters over four provinces is related less to geography and more to history and to a deliberate government attempt to make it administratively harder for Tibetans to organize or act as a single community.

Prior to 1949, warlords and officials loosely associated with the Republic of China (familiarly referred to as the Guomindang or the nationalists) ruled the eastern areas, parts of which had been severed up to 300 years earlier from the Dalai Lama's jurisdiction.[6] Almost immediately after securing control of China in 1949, PRC leaders sent troops into eastern Tibet. A year later, People's Liberation Army (PLA) forces entered central Tibet, the area the Chinese government renamed the Tibetan Autonomous Region in 1965. Tibetans call the incursion an "invasion"; the Chinese refer to it as the "peaceful liberation" of Tibet.

After PLA forces entered Tibetan areas in the eastern part of the Tibetan plateau in 1949, the new PRC government implemented a series of policy changes that led to massive Tibetan resistance and a ten-year period of instability and intermittent warfare in all Tibetan areas. Lithang, Tenzin Delek's home base,was the early epicenter. Open revolt against Chinese policies began there in the mid-1950s and, by all accounts, was brutally suppressed by Chinese forces intent on radically changing Tibetan social and economic structures and on enlisting local leaders' cooperation in furthering so-called reforms.[7] In 1959, in Lhasa, the seat of the Dalai Lama's government, Chinese forces quashed the most serious in a string of uprisings. The Dalai Lama and some 100,000 Tibetans fled to India. Tibet and Tibetan areas were then sealed off to outsiders and radical social reforms, including vigorous restrictions on religion, were implemented throughout the area.[8]

In Kardze as in other Tibetan areas, stories about psychological humiliation, loss of livelihood, decimation of religious institutions, inhumane prison conditions, wholesale slaughter, starvation, and execution of family members in the 1950s, and then again during the Great Leap Forward (1958-60)[9] and the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), fueled resentment directed at Chinese officials and China's Tibet policies.

By 1979, it had become clear that the new policies were not working, and that the harsh retaliatory measures meted out to those who refused to comply had backfired. Rather than creating divisions among Tibetan social classes, as had been expected, government tactics amplified Tibetan identification.

During a visit by then premier Hu Yaobang to the TAR in May 1980 with a Working Group of the (Chinese Communist) Party Central Committee, the government partially reversed course. It agreed to consult and cooperate with regional authorities, apologized for earlier errors, and ordered a large number of Chinese cadres to be removed so that local Tibetans could take over their positions. In a speech at the end of the stay, Hu recommended permitting Tibetans the same "system of private economy" already in place in many other areas.[10] In addition, he implied eventual exercise of full autonomy for Tibetans and the development of Tibetan education, culture, and science.

In theory, a 1984 national law, the "Law of the People's Republic of China on the Autonomy of Minority Nationality Regions," furthered the new policy.[11] It promised so-called autonomous minority regions, such as the TAR, prefectures such as Kardze, and certain counties, a degree of control over their economic, social, and cultural development. However, in the almost twenty years since the law took effect, the Chinese leadership has ensured that autonomy in these areas has remained extremely limited. At the same time, China has taken steps to diminish the influence of traditional religion and culture among Tibetans. In addition, it has moved aggressively to "sinicize" Tibetan areas. Tenzin Delek's prestige and the growth of the monastic community he led, as detailed below, appear to have been viewed as obstacles to this process and as unacceptable displays of distinctive cultural identity.

A series of large-scale political protests in Lhasa, the capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region, in 1987-89,[12] followed in 1993 by populist economic protests there and the spread of political protest to the countryside,[13] played a role in another reversal of course. In 1994, at a meeting called the Third National Forum on Work in Tibet (Third Forum), central Chinese leaders agreed on a program of accelerated economic development and approved a policy that curtailed civil and political rights. There were to be new restrictions on religious activities and monastic independence, efforts to curtail the Dalai Lama's political and religious influence took on a new intensity, and a patriotic (Chinese) education campaign in schools and monasteries began. Taken together, the new policies aimed to eradicate the burgeoning Tibetan independence movement and to encourage migration of ethnic Han Chinese to Tibetan areas.[14]

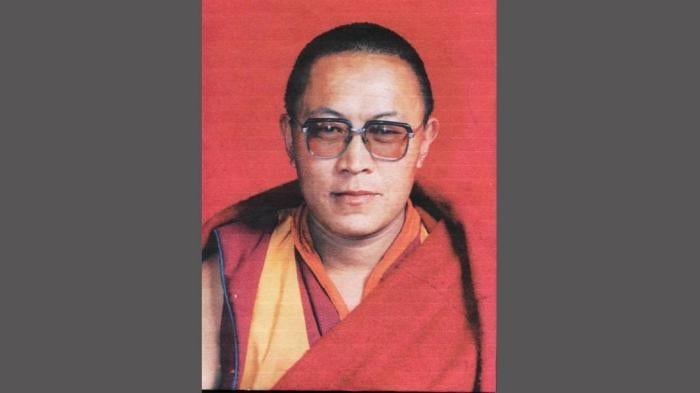

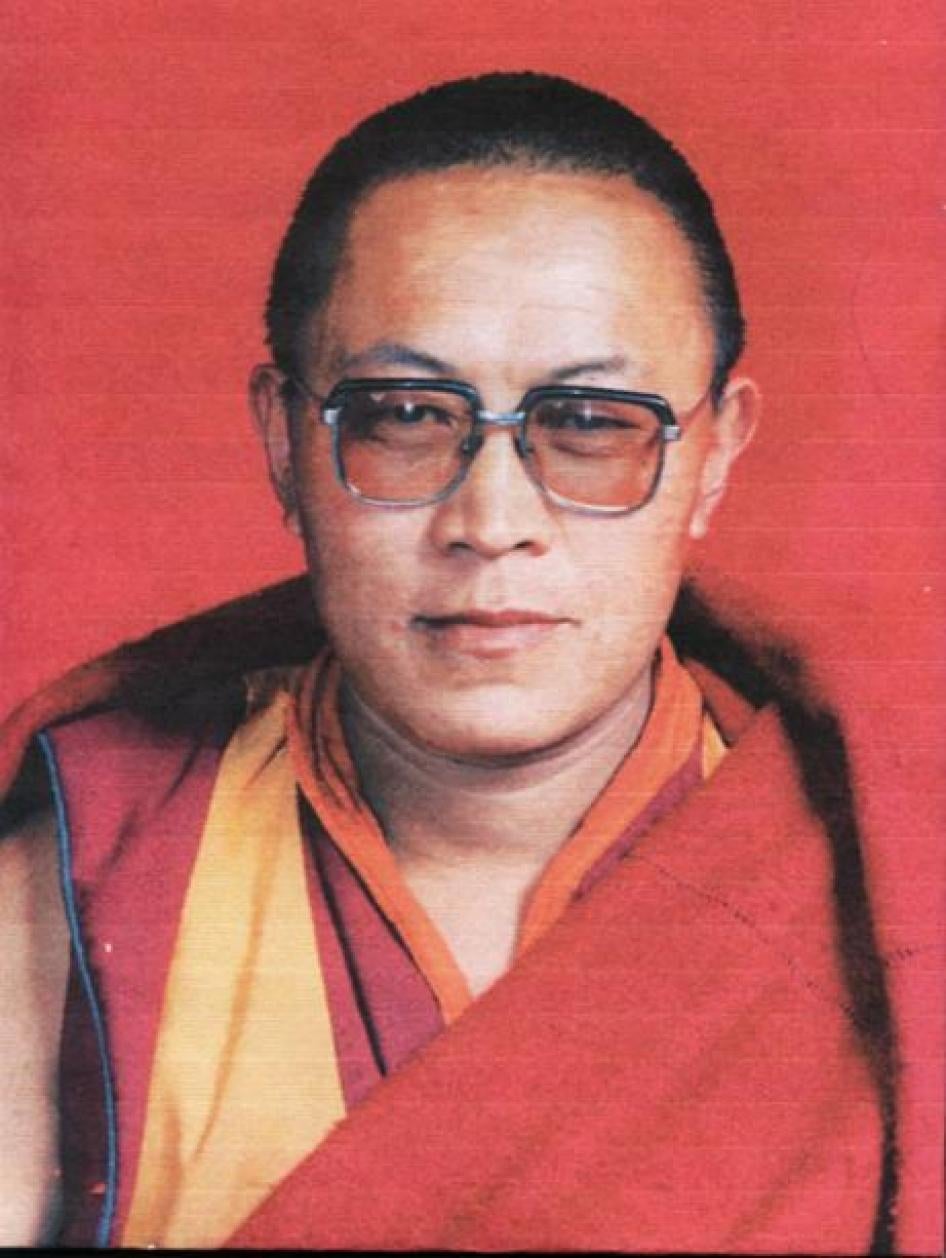

Tenzin Delek

Tenzin Delek was born in 1950 in Kham, the eastern portion of the Tibetan plateau. His name at birth was A-ngag Tashi. In spite of the chaos surrounding the Chinese incursion into Tibetan areas in the 1950s and the ban on all religious expression during the Cultural Revolution, he managed to study Buddhism. During the 1970s, as conditions permitted, he worked to protect and reestablish Tibetan Buddhism in his home region.

From 1982 to 1987 Tenzin Delek was in India, where the Dalai Lama recognized him as a tulku (reincarnated lama). His time in India may have alarmed Chinese officials, partly because the title greatly enhanced his prestige and even his power within the local community. According to supporters, he left home without official permission or travel documents in 1982, in part to further his own education and, in part, because he feared arrest even then.[15]

Tenzin Delek's return in 1987 marked the beginning of a period during which he reportedly was able to bring to fruition many of his proposals for new monasteries, small schools, medical clinics, an orphanage, and old-age homes. It is unclear whether Tenzin Delek received official permission to establish or run these facilities,[16] another possible cause for alarm among local officials.

One of his major projects, begun within two years of his return, was the construction of a permanent monastic structure at the summer site of Geden Tashi Dargyeling monastery, an important religious site in Orthok [see Map 3, "Southeastern Section of Kardze/Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture"].[17] Named Kham Nalendra Thegchen Jangchub Choeling, but usually referred to simply as Orthok monastery, it was the largest single institution that Tenzin Delek founded and served as the core of his growing network of monks, activists, and branch monasteries.

In 1998, Tenzin Delek established a school in a place known as Geshe Lungpa in Nyagchu county [see map] for some 350 orphans and children from poor families.[18] Another school, established in the early 1990s on the site of Orthok monastery, served some 160 students, including orphans and impoverished youngsters. By providing food and shelter as well as an education, Tenzin Delek was able to obtain the agreement of parents, who might otherwise have been reluctant or too poor to send their children to school. Schools such as these, connected to monasteries, often emphasized religious and traditional learning at the expense of a state-mandated curriculum. It is not clear if either school had been licensed to operate.

Tenzin Delek also helped to bring medical facilities to underserved areas. A clinic in Orthok monastery specializing in Tibetan medicine served the local community. Another in Nyagchukha, provided a similar service. A Chinese official has acknowledged Tenzin Delek's beneficial medical work in his local area.[19] However, a planned settlement to shelter nomads during winter, for which Tenzin Delek had allocated funds and purchased materials, was never built after local officials objected. The investment could not be recouped.

Over the years, as Tenzin Delek's activities in the Nyagchukha area led to his rise to prominence, local government officials took increased notice of his activities and views. Many were not in line with local government policies and thus could have been seen as challenges to the authority and influence of local officials. Tenzin Delek was an advocate for the social, cultural, economic, and religious rights of local residents. For example, he challenged officials who indiscriminately backed deforestation projects at the expense of local communities. He was willing to confront officials who put what he considered their own interests before those of their constituents. He took a public position on harmful environmental practices in the area and expressed views that had been outlawed by the central government and that local officials had been ordered to eliminate, such as loyalty to the Dalai Lama and other forbidden religious ideas.

Furthermore, it appears that a significant portion of local residents trusted Tenzin Delek, rather than district cadres, to solve communal problems fairly and efficaciously, in part because of his willingness to approach provincial and central government officials when local efforts failed. The use of locally respected lamas as mediators in conflicts is a traditional practice in Tibetan communities and in many places continues to be encouraged by Chinese officials, with the implicit or explicit understanding that such lamas not oppose local or national policies.

At some point, however, Tenzin Delek must have crossed the line. According to local sources, the major turning point in Tenzin Delek's relationships with local officials came in 1993, when he worked-successfully––to help roll back an attempt to extend clear-cutting to forest land that residents saw as "belonging" to them. According to community members, those officials never forgave Tenzin Delek for their loss of face over the issue.

Residents argued it was this insult that inspired plans to detain Tenzin Delek in 1997-98 and in 2000. Pressure from Beijing on local authorities to curb what Beijing saw as his politically unacceptable activities most likely also played a role. He was finally arrested in 2002. Knowledgeable informants maintain that local authorities were irritated at Tenzin Delek's personal influence and at monastic rather than lay influence in general.[20] They apparently resented his contention that some officials and some lamas neglected the social and economic needs of the populace to seek out higher salaries and increased privileges for themselves.[21]

Lobsang Dondrup

Lobsang Dondrup and Tenzin Delek were distantly related and their family connection may be responsible for the claim of conspiracy against the two. In 1998 or 1999, when Lobsang Dondrup was twenty-four years old and newly separated from his wife, he expressed a desire to become a monk. Tenzin Delek agreed to a trial period. However, one source told Human Rights Watch that after little more than a year, during which Lobsang Dondrup helped with minor chores at one of Tenzin Delek's monasteries, it became obvious that other pressures prevented him from committing himself fully or devoting the time necessary to advance his studies. His mother and son needed his financial help. And he was handicapped by a combination of illiteracy, the absence of any previous formal education, and the relatively advanced age at which he was attempting to begin monastic study.

According to one account, in 2000, Tenzin Delek, aware that the plan was not working out, advised Lobsang Dondrup to pursue his interest in small business ventures. Another account suggests that Tenzin Delek insisted Lobsang Dondrup leave the monastery for flouting its rules.[22]

Local informants have said that Lobsang Dondrup presented a suitable target for officials looking for a relatively unknown and thus unprotected person connected to Tenzin Delek whom they could scare into pointing an accusatory finger at Delek." As one informant explained after Lobsang Dondrup was detained:

What kind of support would he have? He came from a very poor family. They were uneducated. He lived in a very remote place. There was no road. Electricity––there was none. It was like people lived before 1959. And he was a distant relative of the Rinpoche.[23]

Bombs

On April 3, 2002, a bomb, described as a "simple fuse device,"[24] exploded in Tianfu Square in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province in China's southwest. It was this bomb that led to the arrests of Tenzin Delek and Lobsang Dondrup. There was a Xinhua report on January 26, 2003, the day of Lobsang Dondrup's execution, that one person was seriously injured and many others hurt at the time of the blast.[25] Property damage was reported to have exceeded 800,000 renminbi (U.S.$96,400).[26]

Other accounts vary as to the identity of the Tianfu Square bomber, how and when he was apprehended, and the nature of his alleged confession. They also include contradictory information regarding the presence or absence of pro-independence leaflets at the blast sites. Without access to official court documents, particularly the procuratorate indictments and the court verdicts, the discrepancies cannot be resolved.

According to conflicting Chinese government accounts, the detonation was the culminating event in either a series of six bombings beginning in 1998 or a series of four beginning in 2001.[27] Quasi-official reports thatLobsang Dondrup and Tenzin Delek "confessed" to direct responsibility for five attacks[28] cannot be reconciled with the lower figure.[29] Other reports put the number of bombings at seven and are inconsistent in reporting where and when they occurred.

Details about the other explosions are sketchy and vary as to the sites where the bombings took place and the extent of injuries and property damage. What appears probable is that two explosions occurred in 1998 at Lithang Gonchen monastery, some 300 kilometers west of Chengdu.[30] They took place near the living quarters of one or possibly two high-ranking lamas, one of whom was a prominent Sichuan provincial official. One of the two made offerings to Dorje Shugden, a deity whose worship the Dalai Lama strongly advised be stopped. Tenzin Delek had actively campaigned in the area to promote the Dalai Lama's view. (See "Opposition to Worship of Dorje Shugden," page 44 for details about the Dorje Shugden controversy). After official accounts alleged that handwritten leaflets were found at that site, security officers detained a number of Tibetans, including local monks, in order to check their handwriting.[31]

Some accounts report a third explosion in 1999 near the Lithang County government office. At least two people suspected of involvement were detained but never tried.[32] Another two or three bombs went off in Dartsedo (Kangding in Chinese), the Kardze prefectural capital, in 2001. According to an official account, the most serious occurred on October 3, 2001 at an office building of the traffic police. One person, a "watchman" died and monetary damages amounted to 290,000 renminbi (U.S.$35,000). Tenzin Delek reportedly was not charged with responsibility for that incident. Lobsang Dondrup was.[33] If this last account is accurate, it suggests that Lobsang Dondrup might have been charged in connection with six incidents. Another account implies that Tenzin Delek was charged in connection with only four bombings and Lobsang Dondrup with five.[34]

Accounts are consistent in reporting that a bomb went off at a bridge in Dartsedo in January 2001. The third 2001 bomb is variously reported as having occurred at Party headquarters, government offices, or an official guesthouse. According to an account that located the incident at the prefectural offices in Dartsedo, it resulted in two injuries, one of which was "serious," and extensive damage to the building and to vehicles parked in the compound.[35] The probable date is August 2001. An account that located the explosion at the main gate of Party headquarters said that for several weeks the area immediately surrounding the gate was covered with tarpaulins, that traffic had to be diverted, and that the explosion blew out the windows of buildings opposite the site. Both Tenzin Delek and Lobsang Dondrup were charged in connection with that incident.

After the Chengdu bombing, the count stood minimally at seven and possibly as many as ten bombings. There is no known evidence other than Lobsang Dondrup's alleged confession to connect the incidents.

III. Arrests

The Arrest of Lobsang Dondrup

Chinese authorities have produced inconsistent versions of events. Official reports at the time of the verdict identifiedLobsang Dondrup as having been apprehended "fleeing the scene" of the April 3, 2002 blast.[36] However, one person told Human Rights Watch that a local Sichuan television news program initially broadcast a picture of an ethnic Chinese man who was being sought in connection with the bombing.[37] According to the source, it took another two days before Lobsang Dondrup was publicly identified as a suspect, allegedly after a woman who saw him fleeing called the authorities.

TheSichuan broadcaster announced that the unidentified caller should come to the TV station for a reward. However, on April 24, 2002, when the identity of the reward recipient was announced, Xinhua (the official Chinese news service) identified a male college student as the one who had collected 20,000 renminbi (approximately U.S.$2,500). The student was praised for "providing crucial clues that led to the arrest of the suspects behind a downtown explosion."[38] He reportedly was near the site when the explosion occurred.

The Xinhua story went on to say that thanks to the student, it took only ten hours after the noontime detonation to capture Lobsang Dondrup. The time lapse suggests he was detained at 10:00 p.m. on the night of April 3 and conflicts with implications in official reports that he was caught at the site or fleeing the site, or at the time of the explosion. However, a number of Tibetans told Human Rights Watch that neither official version was accurate. They said Lobsang Dondrup was detained well after 10 p.m. on April 3.

Although many informants reported that Chinese officials with whom they worked and local television sources all said that Lobsang Dondrup "confessed immediately,"[39] another official told Human Rights Watch that he initially refused to speak to the police on the grounds that he could not speak Chinese and that it was not until he was moved from a Chengdu facility to one in Dartsedo that he "confessed" and allegedly implicated Tenzin Delek.[40]

At least two other Tibetans were held, each for two months in mid-2002, on suspicion of direct involvement in the explosions. Reports indicated both men were roughly treated and had been warned of severe punishment should they speak out about their detentions.[41] One of the two has fled the country.

No record of Lobsang Dondrup's alleged confession has been made available by Chinese authorities. Furthermore, there is no available evidence buttressing government claims that Lobsang Dondrup linked Tenzin Delek to any of the bombings. One official report simply asserted that Lobsang Dondrup worked "in concert" with Tenzin Delek but gave no other details.[42] In a semi-official telephone interview, the head of the Ganzi (Kardze) judiciary claimed that although Lobsang Dondrup set off the explosions, Tenzin Delek financed the operation.[43] He also alleged that Tenzin Delek composed the message inscribed on the pro-independence leaflets said to have been found at the Chengdu bomb site, but made Lobsang Dondrup copy it in his own hand and then burn the original[44] (security officials regularly check the handwriting on leaflets against a wide range of suspects––sometimes all the monks in a small monastery will have to submit handwriting samples––in an effort to identify a perpetrator). However, Human Rights Watch has learned that Lobsang Dondrup was illiterate and could not write his name or form many of the component parts of Tibetan script. A deformed hand might have further compromised his ability to write.[45]

According to official statements, Lobsang Dondrup was convicted on the basis of his confession. He reportedly repudiated it during the sentencing hearing. Chinese authorities routinely use torture on Tibetan political activists in order to extract confessions.[46] This has raised concerns that such methods were used against Lobsang Dondrup, concerns heightened by his incommunicado detention prior to trial.[47]

The Arrest of Tenzin Delek

Public Security Bureau officials from Sichuan province and Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture waited four days after the Chengdu blast to move against Tenzin Delek. On April 7, he and three of his closest associates, Tamdrin Tsering, Aka Dargye, and Tsultrim Dargye, were seized during a nighttime raid on Jamyang Choekhorling monastery, located in Nyagchukha. Nyagchu county police officers and military personnel arrived several hours after the raid and helped secure the area.

It has been reportedthat the arresting officers abused some of those they took away and did considerable damage to the facility. Tamdrin Tsering, one of those detained, was reported to have been badly beaten. One source told Human Rights Watch: "In the place where he usually slept, the furniture was all broken up and you could see that there had been a struggle, and there was blood on the floor."[48]

A person inside the detention center who witnessed the men's arrival reported that Tamdrin Tsering and Aka Dargye appeared to have been beaten.[49]

It is unclear how many monks remained at Jamyang Choekhorling after the raid––probably between fifteen and thirty. They were held in the monastery for several days for questioning, then ordered to leave both the monastery and the area. Some went to other monasteries, including Orthok; some went home. The doors to the monastery's temple were then locked.

Area residents interviewed said they should have been anticipating Tenzin Delek's seizure for some time before the Chengdu explosion. Several weeks before the raid at Jamyang Choekhorling, security officials in Lithang, Nyagchu, and several other counties executed an orderly plan to collect residents' rifles. The weapons, many costing as much as ten yaks, were not illegal and had been registered with the authorities. In hindsight, some residents, while acknowledging that the timing could have been coincidental, attributed the collection to preparations for Tenzin Delek's arrest.[50]

IV. Trial and Appeal

After almost eight months in incommunicado detention, Tenzin Delek and Lobsang Dondrup were finally put on trial on November 29, 2002. The court met in secret. Three days later, Lobsang Dondrup was sentenced to death; Tenzin Delek was sentenced to death, suspended for two years.[51]

Both men had declared their innocence. According to reports from two spectators, Lobsang Dondrup shouted out his innocence during his sentencing hearing[52] and denied that he had ever said anything about Tenzin Delek or others being involved in a bombing plot. Tenzin Delek also denied the charges, reiterating his innocence in a tape smuggled from a detention center in Dartsedo,the prefectural capital, in mid-January 2003.[53]

Lobsang Dondrup refused to appeal. However, Xinhua reported that the court appointed two lawyers from the firm representing Tenzin Delek to represent Lobsang Dondrup.[54] Human Rights Watch has been unable to obtain any information about the veracity of this report and if the lawyers reportedly appointed to the case ever met with Lobsang Dondrup or made any other efforts to represent their client.

On January 26, 2003, the Sichuan Higher People's Court rejected Tenzin Delek's appeal[55] and the appeal that apparently had been entered for Lobsang Dondrup without his consent. Within hours Lobsang Dondrup was executed.[56] Some reports suggest he was executed very early in the morning on that day, even before the appeal was formally rejected.

The decision to carry out the execution almost immediately after the Sichuan court hearing attracted legal controversy and international condemnation, in part because China's own laws may have been violated,[57] in part because the entire process had been so rushed, and in part because China had broken a promise to U.S. officials that the Supreme People's Court, the highest court in China, would carry out a "lengthy" review of the cases.[58] According to a statement by Wang Min, then Director-General designate of the Department of International Organization and Conferences of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (in response to an E.U. expression of regret over the execution), the Supreme People's Court did review the cases.[59] However, he claimed that only a legal proceeding was held. Chinese law does not require oral arguments or for the parties to be present for Supreme Court review of decisions. Any meaningful reviewwould have been impossible in the time between the decision of the appeals court and the execution of Lobsang Dondrup.[60]

Tenzin Delek's appeal appears to have been seriously hampered by his inability to use counsel of his own choosing.[61] Zhang Sizhi, a well-known Chinese lawyer who had defended dissidents of the Democracy Wall (1979-81) and June 4, 1989 pro-democracy movements, and Li Huigeng, who had previously worked with Zhang, were willing to represent Tenzin Delek at his appeal. On December 18, 2002, the two made the necessary arrangements via telephone with Tenzin Delek's uncle. A signed agreement from him went to the lawyers and then to the court. Telephone conversations between the lawyers and a judge at the Sichuan Higher People's Court followed. By December 26, agreement had been reached that Li Huigeng would visit the court to review the case file. On December 27, Li Huigeng called again to confirm that he and Tenzin Delek would be able to meet on January 6, 2003.

However, on December 30, 2002, the judge called Li Huigeng to say that Tenzin Delek had engaged a Kardze lawyer on December 17 and that the latter had already filed the necessary court papers.[62] A later report by the official Chinese news agency stated that the Kardze lawyers, allegedly chosen by the defendant, represented him at both trial and appeal.[63] As Tenzin Delek was in incommunicado detention throughout the trial and appeal processes, it is impossible to know the contents of any conversations about legal representation, if indeed there were any. The lawyers and Tenzin Delek's uncle sent a letter requesting that the judge tell Tenzin Delek about his uncle's initiative so he could make an informed decision as to representation (see AppendixVI, "Attempt to Hire Independent Counsel for Tenzin Delek Fails"). There was no reply. According to the account, on December 27, the same day Li Huigeng and the Sichuan high court judge conferred by telephone, police officers interrogated Tenzin Delek's uncle and two other relatives and warned them against interference. There is no way of knowing how thorough or impartial the review was in the cases of Tenzin Delek and Lobsang Dondrup, but Chinese courts are routinely given instructions in political cases.

Two meetings, part of an "expose and criticize" campaign[64] organized to denounce Tenzin Delek, demonstrate the extent of political interference in the legal process. The first, called by the Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture branch of the Chinese Communist Party, was reported in a local newspaper on August 12, 2002, almost four months before the men were tried and sentenced.[65] The other, on December 27, 2002, was organized one month before the appeal and execution by the Sichuan provincial level United Front Work Department (UFWD), a Chinese Communist Party organ responsible for organizing support among non-Party members in support of Party policies. (See Appendix III, "Account of a Meeting of the United Front Work Department of Kardze Tibetan Authonomous Prefecture" and Appendix IV, "Account of a Meeting of the Communist Praty of Kardze Tibetan Authonomous Prefecture.")

Lobsang Dondrup was hardly mentioned at either meeting. Those present directed all their criticism at Tenzin Delek. At the first meeting, officials denounced Tenzin Delek, both as a "splittist" (the Chinese term for pro-independence activists) whose activities were destructive to national harmony, and as a monk who engaged in "terrorist" activities under the guise of religion. They repeatedly voiced concern over what was described as a secret "splittist" clique that he headed in southern Kham.[66] One speaker suggested that the Dalai Lama should be held accountable as he was the one who chose Tenzin Delek and was responsible for "misleading his followers…When you put a spear in a bird's nest, you disrupt the nest… But we should point the spear toward the Dalai Lama and his people."[67]

The meeting's leaders recommended that those "ignorant" people who had strayed be brought back to the right path, but warned that the many other "splittists" in the Kardze area would have to be rooted out. Those assembled were warned that they could not afford to treat friends and acquaintances any differently from other suspects.

Invitees to the UFWD meeting, included members of ethnic minorities, "religious personages," and "non-Party persons." The basic charges against Tenzin Delek were the same as those at the first meeting, focusing particularly on how his behavior "blackens religion" and how just his punishment was. But the action agenda differed. According to the record of the meeting, it focused first on strengthening administration of temples and on overseeing monks in accordance with "religious laws, regulations, and policies on religion in such a way that the temples are satisfied, the masses are satisfied, and the Party and government are satisfied" and that religion and the socialist system are brought into "conformity."[68] Meeting leaders also urged that those assembled "propagandize" the illegality of Tenzin Delek's behavior.

Given the involvement and leading role of the Party in Chinese political affairs, the meetings created an atmosphere that was not conducive to a fair hearing for Tenzin Delek or any of his associates or supporters. At both meetings, the organizers elicited apparently pre-arranged statements from leading local figures in support of the official accusations against Tenzin Delek and his "clique" in order to gather support from leading local figures for a guilty verdict. The presumption of guilt is apparent in their statements, prejudicing the right to a fair trial and the presumption of innocence. These meetings also call into question China's contentions that the era of verdicts before trial has ended.[69] The heavy involvement of Chinese Communist Party organs in these meetings suggests that local party leaders were trying to influence the outcome of the trial, a power that party officials still have in China.

V. Detention of Tenzin Delek's Associates and Supporters

Tenzin Delek's arrest set off a crackdown on his associates and supporters. At least sixty others, both monks and laypeople, were detained and interrogated. (See Table 1, "Associates of Tenzin Delek Who Have Been Imprisoned, Detained, Missing.") Unconfirmed reports suggest that the number of those detained, including some held very briefly, may have run as high as eighty.[70] Those sentenced, except for "co-conspirator" Lobsang Dondrup, who worked and studied intermittently in one of Tenzin Delek's monasteries for only a year or so, had worked closely with Tenzin Delek for many years.

Tsultrim Dargye, Aka Dargye, and Tamdrin Tsering, the three monks who were taken into custody with Tenzin Delek on April 7, 2002, served one-year reeducation through labor sentences administratively imposed by the Ganzi Prefecture Reeducation Through Labor Bureau on May 10, 2002.[71] According to an official report, they were charged with engaging in activities inciting "splittism." For three weeks after their April 6, 2003 releases, they were confined to Jamyang Choekhorling, even though it was still officially closed. On April 27, 2003, local authorities permitted them to return to their families but forbade their return to Jamyang Choekhorling. They were allowed to visit Orthok monastery but were not allowed to take part in ceremonies there. Officials warned them they would continue to be watched and had to report weekly to local security officials. Those who saw the three men said they had trouble walking and could not see clearly.[72]

At least two other local residents, Tsultrim Dargye (he is also called Tsuldi; not to be confused with the monk of the same name) and Drime Gyatso,were detained in August 2002 after attempting to raise money for Tenzin Delek's appeal. Drime Gyatso was released quickly, but Tsuldi was held for two months.[73]Both reportedly sustained severe beatings while incarcerated. According to one source, Tsuldi was bedridden for months with kidney problems after his release.[74]

Tserang Dondrup (also called Jortse), an elderly village head detained in June 2002, was reportedly sentenced to a five-year term. Local residents said that the official papers given to Tserang Dondrup's family did not refer to any crime, stating only that his sentence was related to his connection to Tenzin Delek.[75] Tserang Dondrup was released on July 11, 2003. The reason for his early release is not known. Local sources reported at the time that he could not walk, his hands could not function, he could manage only a little food, and his speech was garbled. Persistent reports suggested that he developed trouble seeing after he was imprisoned. By early August, it had become easier to understand him and, according to local residents, by late September his overall condition had "improved."However, he had not regained his pre-prison physical condition. Although he could carry on a short conversation, he quickly ran out of breath. There are reports that during much of the time he was in prison, he was held in complete darkness in an unheated cell. As one visitor reported: "I was so upset. He was so different from what he was before."[76]

At the time he was seized, Tserang Dondrup was a member of the Chinese Communist Party. A few days later, officials held a public meeting to denounce him, strip him of his Party membership, and warn villagers against following in his footsteps. It has been reported that at the trial, to which six local people had been summoned as witnesses,[77] accusations included "cheating the people" and "misguiding them" into supporting Tenzin Delek.

As of December 16, 2003, Tashi Phuntsog, a senior monk in his early forties, was still in custody, reportedly serving a seven-year sentence in a prison in Dartsedo. Although he was at Jamyang Choekhorling at the time of the April 7, 2002 raid, having just returned from a tuberculosis-related two-month hospital stay, he was not arrested until April 17. In the interim, he was intensely questioned. According to one unconfirmed report, in an effort to make it appear as if he had been detained with the others, security officers brought him back to the monastery on April 23 to tape footage of his "arrest."[78] Tashi Phuntsog has been characterized as Tenzin Delek's right-hand man.

Taphel (formal name Lobsang Taphel; also known as Tabo), a local businessman, was sentenced on July 15, 2003 to a five-year term and is in prison in the Aba (Ngaba in Chinese) Tibetan-Qiang Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan province. Local sources report that family members received no documents pertaining to his trial or sentence.[79] As in all the other Tenzin Delek-related cases, no official acknowledgement of his arrest or details of the charges against him have been made available. However, unofficial sources reported that Chinese authorities were alarmed by Taphel's ability to provide information to Western journalists about how Tenzin Delek, Lobsang Dondrup, and the

others in custody were being treated and about warnings made by Chinese authorities to the public of the consequences of speaking out. Taphel also was involved in the effort to secure independent counsel to represent Tenzin Delek at his January 26 appeal hearing.[80] There is credible information that he was severely mistreated for months after his detention in February 2003.[81]

Dzeri Di-Diand Markham Tselo were detained in mid-February but never charged. They reappeared in the Lithang area on April 5, 2002. Officials had told Dzeri Di-Di's family to send two representatives to Tenzin Delek's and Lobsang Dondrup's sentencing hearing on December 2, 2002. He and another of Tenzin Delek's relatives attended.[82]

So far as Human Rights Watch was able to determine, Chinese authorities have made no disclosures about these detentions to Western governments nor have reports about the cases appeared in the Chinese media. An electronic search of the Chinese language press uncovered no reference to the trials of Tserang Dondrup, Tashi Phuntsog, or Taphel.[83]

According to unofficial reports, those released have had their movements curtailed, are required to report to security forces at regular intervals, and must not talk to "outsiders." Other than private prayer, the monks among them arebanned from engaging in any religious activity.

Local sources have also expressed concern about the prison guard who facilitated the taping from his cell during which Tenzin Delek declared his innocence. The contents of his statement were subsequently passed to a Radio Free Asia reporter, who made the information public in January 2003.[84]

At least four monks remain missing. Tenpa Rabgyal and Thupten Sherab (also called Kyido), senior monks from Orthok monastery who were not in residence at the time of the April 2002 events, were so certain they would be arrested that they immediately went into hiding. Choetsom and Pasang, young novice monks who were beaten and questioned extensively after the April 7 raid, but not detained, disappeared soon after they were permitted to leave Jamyang Choekhorling monastery. Other local Tibetans are known to have fled the community. Some have escaped the country, and Human Rights Watch was able to interview several of them for this report.

Some of those imprisoned, as well as some who escaped, worked closely with Tenzin Delek on a number of his social and cultural projects. Some were also involved in efforts to protect him when he was in trouble with government authorities. Tserang Dondrup, for example, hand-delivered petitions to Sichuan authorities during the height of a 1994 drive to prevent local authorities from extending logging into an area reserved for the public's use. In 1998, he was part of a delegation that worked to bring Tenzin Delek home after he fled to escape arrest. In 2001, he organized a successful petition drive, directed at government authorities, requesting that Tenzin Delek be allowed to return home without fear of imminent arrest. Tashi Phuntsog assisted in the deforestation effort and worked on the petition campaigns. Aka Dargye and Tsultrim Dargye were active participants in the forestry campaign. They accompanied Tenzin Delek when, fearing arrest in 1997, he fled to the mountains. Tamdrin Tsering helped with the 2001 petition drive, and he ran a small shop that helped support Tenzin Delek's projects.

VI. Decline of Religious Activities and Social Institutions after Tenzin Delek's Arrest

With Tenzin Delek imprisoned and his followers silenced, the independent religious community he had revitalized in the Lithang/Nyagchu area declined significantly, and the remaining monks and nuns came under additional pressure to conform to Chinese policies regulating religious institutions and activities.[85]Those policies are not in compliance with the right to freedom of religion and belief encoded in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which China signed in 1998 but has yet to ratify.[86] Tenzin Delek's followers cannot freely practice their beliefs, they cannot freely choose their leaders or those with whom they wish to worship, and they cannot, without courting severe imprisonment, impart their beliefs to others.

It is instructive to examine how the monasteries and social institutions established by Tenzin Delek declined after his arrest. (See Table 2, "Tenzin Delek Monasteries" and Table 3, "Tenzin Delek Projects.") Two years before his arrest officials made clear their intentions. In 2000, they took over Geshe Lungpa, the school with the most progressive curriculum, on the grounds that Tenzin Delek had visited a "foreign country" and had established the school without the requisite permission.[87] In the absence of leadership and funds for its upkeep,[88] the school quickly failed. By December 2003, its windows and doors were broken and everyone had left.[89]It is unclear why authorities took over this school but not others run by Tenzin Delek.

For similar reasons, other institutions began to decline almost immediately after Tenzin Delek's arrest. One school's enrollment declined from 160 pupils to thirty. Two homes for the elderly closed due to lack of funds. A health clinic and its satellite also shut down, leaving the area with minimal medical facilities.

Monasteries were also severely affected. At this writing, more than twenty-one months since Tenzin Delek was arrested, two of Orthok monastery's branches remain closed. There are far fewer monks and nuns in residence at almost all of those that are open (there has also been a decrease at another monastery that had been left in Tenzin Delek's care prior to his arrest). Festivals and ceremonies do not attract the usual numbers of participants. It is unclear whether the reduction in the number of monks and nuns resulted from official directives or whether they left of their own volition.

The present situation at the monasteries varies considerably. Orthok monastery, technically under Lithang Gonchen monastery, is in a state of flux with no definitive word available on its status or on plans for its future. There have been unconfirmed reports that officials have ordered Orthok demolished because the structure is not sound.[90] Local residents dispute the official version. They say the main building is strong and secure, but with so many monks away and Tenzin Delek not there to oversee the property or contribute the funds necessary for upkeep,[91] the surrounding housing has been neglected.

The monastic population at Orthok is considerably smaller than in 1987-2000, when Tenzin Delek was in residence. Only 290 monks remained at Orthok in 2003. At its peak, its population exceeded 700. Of those, Tenzin Delek sent some 170 to monasteries in Lhasa for general study. Another 10 were sent out from Orthok to study Tibetan medicine.[92] The reduction is in line with official plans, put in place for Tibetan areas after the 1994 Third Forum, to reduce the total number of Tibetan monks and to limit the number at each monastery.[93]

One monk explained the current departures: "Everyone feels that staying at the monastery is like being in jail, so many of the monks have left. Some have gone back to their families, some have joined another monastery, and some have gone on pilgrimage."[94] According to an eyewitness who had last visited the monastery earlier, roughly a year after Tenzin Delek's arrest, "Orthok is not shut down but it is not open either."[95] At that time, religious officials were closely monitoring the facility and the lay community, in part through random surprise visits. Surveillance methods included checking to see if people were saying prayers for Tenzin Delek or for the Dalai Lama. As the situation slowly stabilized, the spot-check monitoring lessened.

Another surveillance method involved checking for Tenzin Delek photos. If one was found, either in the monastery or in a home or shop, the owner was questioned as to why he or she was not heeding public announcements about the prohibition, and then warned to stop. As this report was being finalized, word came of renewed enforcement in Lithang county of the long-standing ban on possession of Dalai Lama portraits, books, video tapes, and similar materials. According to one report, officials making the rounds of villages and townships told residents they had one month to hand over Dalai Lama pictures or face confiscation of their land.[96]According to another report, government officials found in possession of any such materials would be subject to a fine of 4,000 renminbi (U.S.$500).[97] In addition, officials were charged with putting an end to an upsurge in pro-independence activities, such as wall postering, leaflet distribution, and hoisting of the banned Tibetan flag.[98]

Before Tenzin Delek's arrest, festivals at Orthok were well attended. As one source told Human Rights Watch, a year later no substantial activity was taking place: "All the public is in a mourning period."[99]

At meetings called at Orthok, Chinese officials "advised" that if the monks did not resume coordinating the local public ceremonies and festivals, the monastery would be fined.[100] However, the monks refused to accept responsibility for imposing the discipline necessary to maintain order at large gatherings, fearing that participants would not grant them the same authority Tenzin Delek enjoyed.[101] Orthok monks say that closing the monastery is not an option. One monk told Human Rights Watch, "That would be a big loss––we've already lost so many monks."[102]

Jamyang Choekhorling, where Tenzin Delek was seized, is also in a state of flux. At the time of the raid, religious authorities had limited the number of monks to twenty-five. More often than not, however, at least forty were in residence.

By April 2003, three monks, including a tea-maker and a caretaker, took up residency in Jamyang Choekhorling, with the monks meeting in the kitchen to perform their religious rituals. During that entire period, however, it was impossible to do so properly and "ordinary people" could not enter the monastery.[103] Several other monks, including the three released from reeducation through labor sentences, also stayed at the monastery––some for only a few weeks––some for more than a year.[104] All this time, until mid-June 2003 at the latest, the main hall of the monastery was locked.[105] By that time, members of the local community had opened it without official permission.[106] Even after this reopening, more symbolic than real, the monastery was still off limits to most of the population.[107]

Soon after the opening, some monks from Orthok joined the three already in residence at Jamyang Choekhorling in order to hold a traditional annual ceremony. However, Nyagchukha authorities showed up and questioned those in attendance about the monastery's being open. They also questioned members of a local community who "belonged" to the monastery, that is, who helped out with offerings of food and with services such as cleaning, repairs, and snow shoveling.[108] By early August, despite pleas from the populace to keep Jamyang Choekhorling open, security had closed it down again.[109]

By early September, negotiations were underway for a genuine reopening of Jamyang Choekhorling, but under the control of a monastery other than Orthok. Some local villagers, as well as monks from Orthok, have made it clear that they strongly prefer that if Orthok monks are not permitted to take up residence at Jamyang Choekhorling, it should remain closed. The plan as of October2003 seemed to have been for five additional elderly Orthok monks to move there. Those chosen would be known for their adherence to government religious policy.[110]

Sungchoera monastery, also known as Kechukha monastery, was closed almost immediately after Tenzin Delek's arrest. The public was permitted to enter to pray, but no rituals were performed in the monastery and no monks or nuns of the original forty were in residence.[111]

Losses at Tsochu Ganden Choeling and Golog Thegchen Namdrol-ling are notable. The former once housed thirty monks; only three are left. Despite its reputation for outstanding education, the latter was reduced in size from forty to eight monks. Another monastery, Golog Tashikyil, once housed forty people, including orphaned or destitute children, teachers, and monks in retreat; only three monks are left: one is the caretaker and the other two are in retreat. Kham Choede Chenmo Jangsen Phengyal-ling (also called Detsa monastery) now houses some sixty monks, a loss of one hundred.

The losses at Tsun-gon Dechen Choeling, a nunnery, have been smaller. Of the sixty nuns in residence during Tenzin Delek's time, fifty remain. Tshe-gon Shedrub Dargyeling, the monastery that had been left in Tenzin Delek's care by its former head, lost forty of its original 330.[112]

VII. Tenzin Delek's Life and Work Prior to His April 2002 Arrest

The Early Years

Monastic education was one of the few avenues––if not the only avenue––open to Tibetan families for educating sons. Tenzin Delek, the oldest child and only son of a Lithang nomad family, entered "into the livelihood"[113] of Lithang Gonchen monastery, the major center of learning in the area, in 1957.[114] He was seven years old. Several years earlier, Chinese authorities, alarmed by the extent of spontaneous, but isolated resistance that had begun in and around Lithang,had moved to disarm local Tibetans and had instituted "struggle sessions" to denounce villagers opposed to economic and political reform.[115] Only a year before Tenzin Delek became a monk, in 1956, Chinese troops bombarded Lithang monastery during a brutal battle in which tens of thousands of combatants lost their lives.[116] In 1959, as the military campaign against Tibetan resisters peaked, the area descended into chaos. That year, after Tenzin Delek's teacher died during another battle,he went to live with an elderly relative where he could informally and clandestinely continue his studies.

Ten of the sixteen years Tenzin Delek was to live with this relative, working on the family farm, coincided with the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), a decade of tremendous and violent social upheaval. Among other proscriptions, China's leaders banned any form of religious expression any place in China. By the time the decade was over, few of the Tibetan temples and monasteries that had survived the 1950s were left intact and the numbers of monks and nuns had declined precipitously. Obviously, Tenzin Delek had no opportunity for formal study but he continued to risk studying covertly.

As one informant explained:

During that time you couldn't talk about anything, god, ghosts, karma. If you did you were made to stand up in those meetings…Around that time the Chinese found a scripture in my grandmother's house. They tied my uncle with his hands behind his back and made him kneel down in public and made my grandmother burn the scripture pages one by one. My grandmother and my uncle felt they had committed a great sin. Even in the 1980s when things were getting better, they would cry about it.[117]

In the mid-1970's, after Tenzin Delek's relative died, he returned to his mother's home. When he returned, even before it was really safe to do so, Tenzin Delek often brought home religious artifacts––statues, pictures, scriptures––that others had hidden in attempts to prevent their total destruction and that he had found unclaimed and still partially hidden. He showed them to interested villagers and explained their significance.[118] His activism led to brief periods in local lockups––sometimes for ten days, sometimes for a month––and to repeated beatings. By the late 1970s, an opportunity to resume formal, if still clandestine, monastic studies with a prominent teacher became available in his home village.

By the late 1970s when it was no longer so dangerous, Tenzin Delek was using every available opportunity to press for the revival and enhancement of religious activity in the Lithang area. He was interested in re-opening and rebuilding monasteries and augmenting the ranks of monks.

Tenzin Delek's first major opening came in 1979 during a short-lived period of relative liberalization, when a Tibet government-in-exile delegation, including Lobsang Samten, the Dalai Lama's brother, came to investigate the situation in Tibetan areas. Although local authorities had insisted Tenzin Delek come for a short "reeducation" course because of his general opposition to Chinese policies[119] and had restricted his right to travel, he managed to meet Lobsang Samten and to tell him about the destruction of Lithang monastery and the still standing restrictions on religious practice in the area.

A second initiative came in 1980 when the 10th Panchen Lama, regarded by Tibetans as the second most important figure in Tibetan Buddhism, traveled to Labrang monastery[120] in the course of his first visit to Tibetan areas in some eighteen years. He had been released three years earlier after having been held in a Chinese prison or in house arrest for fourteen years. Skeptics say the Chinese government permitted him to travel to Tibetan areas in order to assure the population that the Cultural Revolution had been wrong, and more importantly, with the Dalai Lama in exile in India, to bolster his own profile among Tibetans. At the time, with the full story of his relationship to the Chinese leadership authority still largely unknown, many thought of the Panchen Lama as a traitor to the Tibetan cause for having allegedly cooperated with Chinese authorities.[121]

Again, Tenzin Delek could not travel without permission, but again he managed a meeting. After describing how few monasteries were actually functioning, Tenzin Delek received assurances from the Panchen Lama that new regulations provided for the rebuilding of those destroyed during the Cultural Revolution and for rehabilitation of those Tibetans who had been mistreated. Armed with knowledge of the policy change, Tenzin Delek was able to pressure local officials for compliance, possibly at the price of their increased resentment. He repeatedly visited county officials in an attempt to have Lithang monastery re-opened. The first ceremonies there were held in the early 1980s; the monastery's assembly hall was not completed until 1984.[122]

Almost a decade later, the Panchen Lama's backing made it possible for Tenzin Delek to overcome local officials' opposition to his plans to build a permanent structure at a site in Orthok. Kham Nalendra Thegchen Jangchub Choeling, as it was named by the Panchen Lama, or Orthok monastery as it was commonly called, was to become Tenzin Delek's main monastery. The Panchen Lama's intervention helped further monastic studies in the area and enhanced Tenzin Delek's own growing reputation at home and in other Tibetan areas, leading in turn to his ability to speak out with some impunity. He became a role model for those interested in preserving Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan culture. Tenzin Delek's ability to win the Panchen Lama to his cause was a humiliating defeat for area officials.

In 1982, the Chinese leadership made explicit a new policy which recognized that the inevitable dissolution of religion in China would take a very long time.[123] Until then, limited religious beliefs and what came to be known as "normal" religious activities would be tolerated, but only as expressions of faith divorced from political and social realities and concerns. As Chinese authorities later argued, Tenzin Delek crossed the line. He might have categorized his activities as areas of legitimate monastic interest, but officials determined to bring religion under the aegis of the state categorized those same activities as political.

Tenzin Delek probably recognized the political nature of his activities. If not, it is probable that he would not have begun his monk recruitment initiative in secret.[124] Working through a clandestine network of trusted acquaintances, he attracted some 175 prospective monks, who, once they were ordained, returned to their home areas to help revive Tibetan Buddhism. But by 1982, the secret operation was so widely known and the numbers it attracted so large, that it was no longer safe to continue either recruitment or ordinations.

In 1982, Tenzin Delek left Lithang without permission from government authorities for study at Drepung monastery in India, in part because he wanted a broader education, in part because he had clashed repeatedly with those in control at Lithang Gonchen monastery, and in part because he feared arrest. He did not return home until 1987. By then, the Dalai Lama had recognized him as a reincarnation of a lama (Geshe Adon Phuntsog) affiliated to the monastery at Orthok and had given him the name Tenzin Delek. As already noted, before the change he was known as A-ngag Tashi. Tenzin Delek risked arrest at his return by carrying over the border, and later distributing, copies of the Dalai Lama's writings and audio tapes of his speeches. According to a disciple, Tenzin Delek told his own supporters that "to follow His Holiness' wish is more precious than your [own] life."[125]

Building a Base at Orthok Monastery

Shortly after his return from India in 1987, as noted above, a major project for Tenzin Delek was the construction of a permanent monastic structure in Orthok. For centuries, monks and lay people had come together there for religious ceremonies, festivals, and seasonal celebrations, apart from occasional periods when the site was inactive. There had been no permanent structure; those who attended the events, mostly nomads, stayed in tents. In 1988, Tenzin Delek attempted to construct a permanent facility. When local officials refused to issue the requisite permits, he traveled to Beijing to secure the Panchen Lama's approval.

Orthok monastery was only the beginning. An ambitious building and renovation program begun in 1991 included a school and orphanage, an old-age facility, medical clinics, and seven branch monasteries. The social programs Tenzin Delek established were badly needed. His efforts made it possible for Tibetan children to receive some education which the minimal facilities in the area and the expense entailed had denied them. The medical facilities he established served the local community and nomads who were brought in by horseback. For the elderly who lacked proximity to medical facilities and for members of a monastic community who, without family, were badly in need of basic care, he provided a place to stay, blankets in winter, and a monthly allotment of meat, butter, and tsampa (roasted barley).

In addition, Tenzin Delek strove to turn Orthok monastery into a center of great learning and to make it into a facility that would expand the horizons of the local populace.[126]At his urging and sometimes with his financialsupport, young monks furthered the goal by traveling to Dharamsala, the seat of the Dalai Lama's government-in-exile, and to the great monasteries in Lhasa and other Tibetan communities to study Tibetan Buddhism, culture, medicine, arts, and music, to hone their skills, and to gain new experiences. Within the monastery, he established a Dialectics School and a special section to study Tibetan medicine. For both political and personal reasons, local officials may have resented Tenzin Delek's increased activity and burgeoning prestige, but action to curtail his plans and what was viewed as his interference in local affairs was still several years away.

Standing Up to Local Officials and Promoting Environmental Conservation

Tenzin Delek's awareness of how quickly an ecologically balanced environment could deteriorate and how ruinous that would be for local inhabitants prompted him to promote sound conservation habits. He preached against mining practices that would pollute the areas' rivers and ruin the soil, logging practices that would cause flooding and soil erosion, and indiscriminate hunting that might lead to species loss. Tenzin Delek's views alarmed local authorities who favored unhindered economic growth and who are reported to have personally profited from mining, clear cutting, and poaching.[127] As they learned, he was able to garner sufficient support to partially block the spread of deforestation in the Lithang/Nyagchu area.

Clear-cutting of old growth forests for profit was one of the most contentious environmental issues within a five-county region, which included Nyagchu and Lithang. According to former local activists, Chinese officialsfirst became involved in "cutting trees like hairs on a head"[128]in Nyagchu county in the early 1980s.[129]Although it was necessary to build some roads and bridges to transport logs, thick stands of trees and a network of rivers made it relatively easy to cut and ship timber to central China. Tenzin Delek's campaign against the practice began in 1987-88, but it wasn't until 1993, after a sharp increase in deforestation practices provoked an escalating local response, that officials moved to directly counter his opposition.

According to those who formerly lived in the area, forest land was divided informally into three categories: one reserved for government use; one available to township[130]officials for their personal use, such as building a house; and the third, the so-called public land, for use by local residents. By 1993, the local residents had come to find two official practices almost intolerable. One was the need to obtain permission to "build a house or get poles for a nomad tent." Former residents reported they had to "bribe officials, giving them butter and meat."[131] The second complaint related to the concern of residents that local security and forestry department officials were working in concert to divert public land to the government sector. According to one Chinese environmental activist with whom Human Rights Watch spoke, county budgets in some areas in China were heavily dependent on revenues from lumber.[132] Forestry departments, he explained, were not created to protect resources; the expectation was that they would open up new areas for logging.[133]

The issue came to a head in the Nyagchu area on November 9, 1993. It centered on a township called Lola. The government section was "pretty well logged out" and township and county officials had imminent plans to seize public lands. About a month earlier, they had moved a marker designating the border between "government" and "public" land.[134] As one source explained:

At a place called Lola, a densely forested place with huge trees about 500 years old, the Chinese took the bark of one tree and wrote on it in capital letters with red paint, "forest above this tree belongs to public – below to government." The sign moved the boundary almost two kilometers inside the public forest. The township, county, and local officials had given bribes to prefecture officials [in order to be able to continue logging]and told the local population that they had to be quiet.[135]

In the week before November 9th, Tenzin Delek convened a meeting for community leaders and family representatives. He explained that as local leaders, they had an obligation not to ignore the problem. But, he continued, no matter their collective decision, he was prepared to take on the issue even if it meant going to prison. According to one report, he said:

We all know this forest is public forest, but a few officials from the county and township are trying to move into it. If they do they will definitely destroy it. We all have to work on this. If we ignore it, it will be environmentally damaging, and it will bring storms and floods.[136]