China's Forbidden Zones

Shutting the Media out of Tibet and Other "Sensitive" Stories

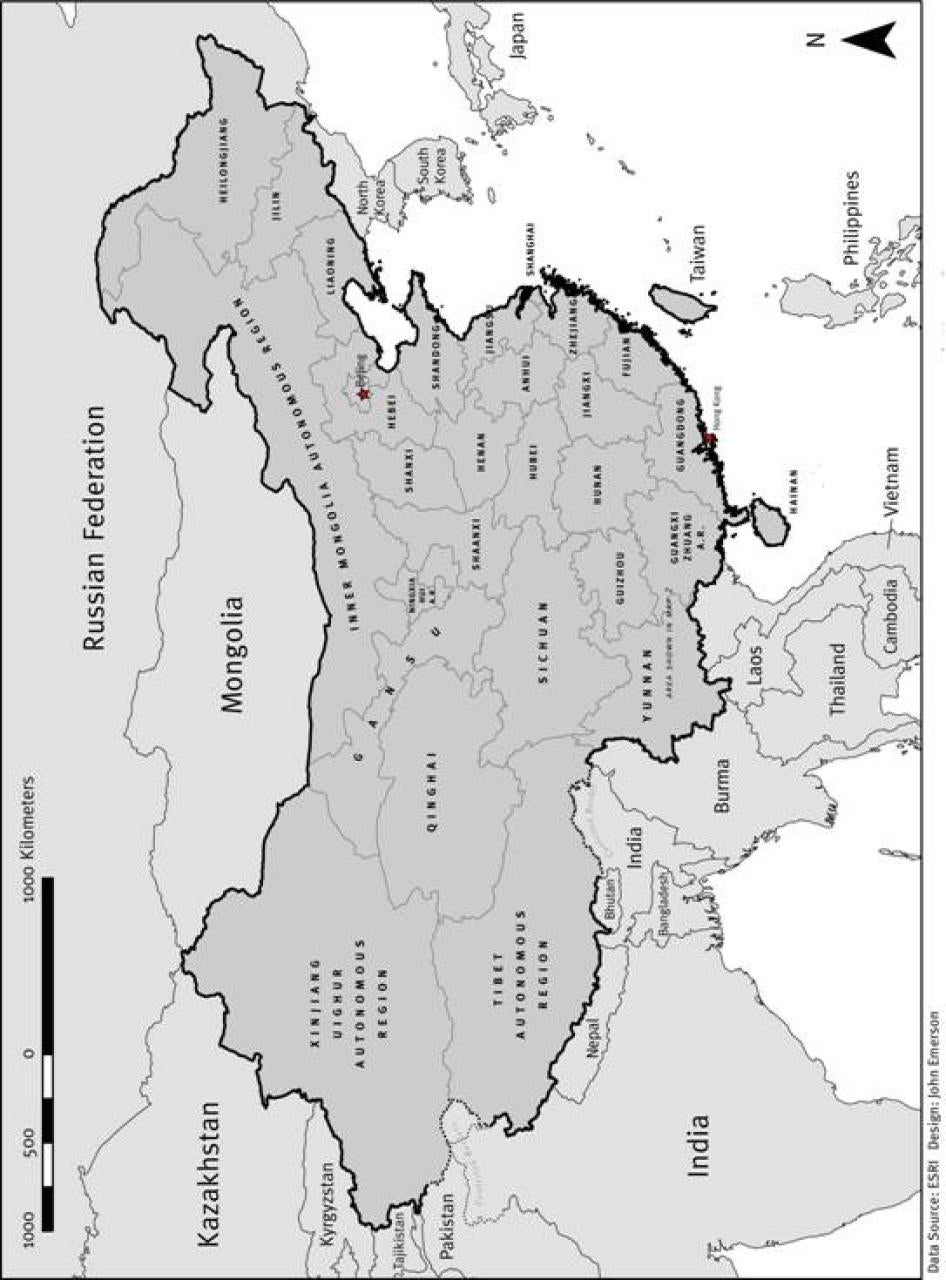

Map of China and Tibet

Provinces and Autonomous Regions of the People's Republic of China

I.Summary

The run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games was supposed to be the start of a new era of media freedom in China.

Both the Chinese government and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) touted these Games as an historic catalyst for wider openness for the one-party state. The Chinese government's 2001 bid to host the 2008 Olympics was successful in part because China pledged to improve media freedom and the IOC believed that international attention to China would help improve the human rights situation. Indeed, in January 2007, the Chinese government adopted new temporary regulations designed to allow foreign journalists to travel freely across China and speak with any consenting interviewee.

As this report shows, the gap between government rhetoric and reality for foreign journalists remains considerable. Their working conditions today, while improved in some respects, have deteriorated in other areas, dramatically in the case of Tibet. The result is that during a period when reporting freedoms for foreign journalists in China should be at an all-time high, correspondents face severe difficulties in accessing "forbidden zones"-geographical areas and topics which the Chinese government considers "sensitive" and thus off-limits to foreign media. An important consequence of the continuing barriers is that there are key events and trends in China that cannot be covered in detail or at all, to the detriment of Chinese citizens and all who are concerned in the often-dislocating social and economic changes underway in the country.

While this report focuses on foreign journalists, it must be noted that Chinese journalists, who already operate under far greater constraints, are being subject to further controls in the countdown to the 2008 Olympic Games. In late 2007, the Central Publicity Department issued a notice which instructed Chinese journalists ahead of the Olympics to avoid topics which generate "unfavorable" publicity in the foreign media, and to be extremely careful in reporting about subjects including air quality, food safety, the Olympic torch relay, and the Paralympics; which occur in Beijing in September 2008.[1] In June, President Hu Jintao urged China's domestic media to "maintain strict propaganda discipline...and properly guard the gate and manage the extent [of reporting] on major, sensitive and hot topics."[2]

Several foreign correspondents told Human Rights Watch that the temporary regulations guaranteeing media freedom have in some ways improved their ability to report. Specifically, some say that in the first year the regulations were in effect, access to high-profile dissidents, human rights activists and sources in general improved, and they enjoyed greater mobility. Some correspondents have also praised China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) for actively intervening in and resolving a number of cases in which journalists were harassed, detained, and intimidated by government officials or security forces. Some correspondents told Human Rights Watch that prior to the crackdown on Tibet in March 2008, the temporary regulations had helped put an end to once-routine practices such as late night hotel visits by officials to journalists on reporting trips outside of Beijing and Shanghai, which were designed to pressure reporters to leave the area as soon as possible.

Yet many foreign correspondents we spoke with say that conditions have worsened in some areas over the past year. Nearly all say that journalists today continue to face significant obstacles whenever the issues on which they wish to report are deemed "sensitive" by central or local authorities. The ongoing closure of Tibet to foreign journalists offers the starkest illustration of this point.

This report details troubling developments on a number of fronts over the past year. It shows that, in some cases, officials have attempted to extort positive coverage from journalists by threatening to withhold their accreditation to cover the Olympics. It also documents cases of intimidation of foreign journalists' sources-less visible and considerably more vulnerable targets than the journalists themselves-and presents evidence suggesting that such intimidation is on the increase.

The report also offers the most detailed account to date of how, following unprecedented protests in Tibet in March, security forces moved swiftly to remove journalists from Tibetan areas and keep other foreign journalists from entering. On June 26, the government announced that Tibet was officially reopened to foreign media "in line with previous procedure"[3]-an onerous, time-consuming application process which rarely results in permission to visit Tibet. That means foreign journalists will likely remain unable to determine what prompted the unrest or to verify the numbers of those killed, injured, or arrested in the biggest government crackdown since the June 1989 Tiananmen Massacre. It also examines the government's failure to respond to anonymous death threats against several foreign correspondents and their families, part of a nationalist backlash against perceived bias in western media coverage of Tibet that was fed by state-run media.[4]

Finally, the report examines three specific topics that are largely no-go zones for foreign journalists today: the plight of petitioners (citizens from the countryside who come to Beijing seeking legal redress for abuses by local officials), protests and demonstrations not sanctioned by the government, and interviews with high profile dissidents and human rights activists.

The result of the continuing and in some areas intensifying restrictions on media freedom is that crucially important issues, such as protest and dissent, go largely unreported, leaving Chinese citizens and people all over the world without reliable information about what is actually happening inside China. In part because the IOC has been unwilling to voice concerns publicly over these developments, hopes for improvements in 2008 appear increasingly faint.

The government has sought to deflect criticism of its failure to deliver on its media freedom commitments by telling foreign journalists to "stop complaining" about violations of the temporary regulations[5] and alleging correspondents attract justifiable interference from government officials and security officials because they "violated professional morality, distorted facts or even fabricated news."[6] There is no evidence for these claims. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs' (MOFA) justification for closing Tibetan areas to correspondents since mid-March has ranged from a claim that unspecified laws or regulations allow the government to supersede the temporary regulations to vague warnings of threats to journalists "safety" and "security."

The Chinese government has been internationally praised for its relative openness to the domestic and foreign press in the wake of the massive earthquake in Sichuan province on May 12, 2008. Foreign correspondents have reported mixed experiences trying to cover the quake-on June 3, police "forcibly dragged" an Associated Press reporter and two photographers away from the scene of a public protest by parents of student victims of the quake in the Sichuan town of Dujiangyan,[7] while other foreign correspondents had no trouble accessing and reporting from the same town. Since June 2, 2008, the Foreign Correspondents Club of China (FCCC) has documented at least nine incidents in which correspondents in the Sichuan quake zone have been "manhandled," "detained," or "forced to write self-criticisms" while attempting to report.[8]

In addition, the Central Publicity Department (formerly named the Central Propaganda Department in English) reportedly issued an edict within hours of the earthquake in an effort to ban domestic media from sending reporters to the disaster zone. When reporters already en route to the disaster zone began filing reports immediately upon arrival,[9] the Chinese Communist Party's politburo standing committee instead stipulated that domestic media coverage of the disaster "uphold unity and encourage stability" and emphasize "positive propaganda."[10] In late May, the Central Publicity Department instructed Chinese media to reduce coverage of the collapse of schools in the earthquake zone which killed thousands of students.[11] While the government should be praised for the instances in which it allowed correspondents free access, it is too soon to declare a major victory for media freedom in China.

Human Rights Watch remains concerned that violations of the temporary regulations and state-sanctioned vilification of foreign journalists in China could "poison the pre-Games atmosphere for"[12] the estimated 30,000 foreign journalists[13] who will cover the Beijing Olympics. Unless Chinese government practices change, the ongoing official obstruction of independent reporting by foreign journalists and public hostility toward foreign media may prompt correspondents to opt for the relative safety and predictability of state-organized media tours which provide sterile, government-approved depictions of China.

Such an outcome would represent a betrayal of both the Chinese government's commitments to the IOC of expanded media freedom during the 2008 Games as well its assurances to the international community that hosting the 2008 Olympics in Beijing would help promote the development of human rights across China. Perhaps worst of all, it would mean that most international coverage of China did not address many of the country's most compelling, difficult issues.

Key Recommendations

Human Rights Watch urges the Chinese government to:

·Ensure that the temporary regulations on media freedom for foreign journalists are fully respected in the period before they officially expire on October 17, 2008.

·Implement the June 26 MOFA commitment to reopen to foreign journalists the Tibet Autonomous Region and grant unrestricted access to Tibetan communities in the neighboring provinces of Gansu, Sichuan, Qinghai, and Yunnan.

·Investigate death threats made against more than 10 accredited correspondents in China since March 14, and ensure their safety at a time when state-media reports on alleged foreign media "bias" towards China has inflamed public anger toward foreign journalists in China.

·Commit to permanently extending the temporary regulations freedoms after October 17, 2008.

Human Rights Watch urges the IOC to:

·Establish a 24-hour hotline in Beijing for foreign journalists to report violations of media freedom during the August 2008 Olympics, directly inform the foreign ministry of these incidents and demand their speedy investigation.

·Publicly press the Chinese government to uphold the temporary regulations.

·Amend the criteria for Olympic host city selection in order to ensure that, consistent with Olympic Charter promises to uphold "universal fundamental ethical principles" and "human dignity," potential hosts' human rights records be made an explicit factor in decisions.

·Create an IOC standing committee on human rights as a long-term mechanism to incorporate human rights standards into the Olympics.

These measures are essential to ensure freedom of expression and the safety of the tens of thousands of journalists expected to cover the 2008 Beijing Games. They are also essential to preserve the reputation of the Olympics and prevent repetition at future games of the IOC's failure to effectively monitor and ensure implementation of host country human rights pledges.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou between December 2007 and January 2008, and in follow-up interviews through June 2008. We spoke with a wide variety of sources in China's foreign media community, including photographers, television journalists, and text reporters. These correspondents detailed their experiences of being harassed, detained, and intimidated in direct violation of the temporary regulations on reporting rights for foreign journalists. As noted below, the report also draws on Chinese government documents and news stories in domestic and international media.

The scope of this study is necessarily limited by constraints imposed by the Chinese government, which does not welcome research by international human rights organizations. In most cases, interviews were conducted under the condition of strict anonymity due to correspondents' concerns about their employers' internal regulations on public statements regarding their work, as well as fears of possible retribution from the Chinese government. A handful of correspondents whose employers do allow them to speak on the record about their work bravely ignored the risk of possible reprisals from Chinese government agencies and went on the record with their comments.

The direct interviews that Human Rights Watch was able to conduct for this report, while limited, are fully consistent with other research findings by other nongovernmental organizations, including the Foreign Correspondents Club of China, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and Reporters Without Borders; indicating that the problems described here are systemic, likely affecting hundreds of foreign correspondents each year.

II.Background: Longstanding Media Freedom Constraints in China

[Self-censorship] is a lofty leadership art, and a key to success.[14]

-Yang Weiguang (杨伟光), former head of state broadcaster China Central Television, November 10, 2007.

Constraints on Media Freedom

Although Article 35 of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China explicitly guarantees "freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and demonstration," China's domestic media has for decades been subject to strict government controls which ensure that reporting falls within the boundaries of the official propaganda line.

Official Chinese statistics indicate that as of February 2006, the domestic media landscape included 2,000 newspapers, over 8,000 magazines, 282 radio stations, and 374 TV stations.[15] But despite the volume and variety of China's media outlets, they remain part of a state-owned-and-controlled system designed to ensure positive news coverage of the government and the ruling Chinese Communist Party.

The Chinese government's guidelines on taboo topics, which are officially deemed as "sensitive" or min-gan (敏感), strictly determine editorial content. The official Publicity Department sends weekly faxes to domestic media outlets stipulating the latest coverage restrictions. Those restrictions typically are framed in terms of avoiding issues potentially disruptive of the "social stability" goals of the Chinese government.[16] Notable past examples include the massive death toll of Hebei province's Tangshan earthquake in July 1976, which journalists were forbidden from disclosing for more than three years,[17] and the early stages of China's outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, in 2002-2003, coverage of which government officials blocked.[18] These constraints-imposed to avoid politically embarrassing controversy rather than for reasons of public safety, public order or national security; violate Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and Article 19.2 of the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights,[19]which China has signed, but not ratified. The Central Publicity Bureau's censorship practices also violate sections of the United Nation's Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Declaration on Fundamental Principles concerning the Contribution of the Mass Media to Strengthening Peace and International Understanding, to the Promotion of Human Rights and to Countering Racialism, Apartheid and Incitement to War.[20]

The government deploys various techniques to control the media. In addition to the faxes discussed above, journalists' computer terminals at China's national television broadcaster, China Central Television (CCTV), are linked to an electronic notification system which automatically notifies journalists of the most recently updated list of issues which are deemed inappropriate for news coverage.[21]In 2007 and early 2008, China Central Television (CCTV) alone restricted coverage of stories ranging from the death of a pregnant migrant worker in December after she was denied medical treatment due to a lack of money to pay doctors, to reports that same month that the Chinese government had imposed a ban on the showing of American movies in Chinese theaters, to the death of Pakistan's former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto in January 2008.[22]

Articles are thoroughly vetted, especially if they focus on events important to the ruling Chinese Communist Party, such as the annual meeting of China's parliament, the National People's Congress (NPC). A handbook obtained by Reuters for Chinese journalists covering the NPC session in March 2008 laid bare the pressure on journalists to carefully script news coverage of the event in line with Central Publicity Department dictates:[23] "Uphold the system of submitting articles for approval. The responsible propaganda official must sign off on articles planned for submission."[24]

Those who try to move beyond those confines face a variety of sanctions, ranging from physical abuse to job loss. In August 2007, a group of five Chinese journalists, including a reporter from the Chinese Communist Party mouthpiece, The People's Daily, were attacked by unidentified thugs while interviewing relatives of the victims of central Henan province's Fenghuang bridge collapse, in which 34 people died. When police finally arrived on the scene, they ignored the assailants and instead detained the journalists.[25] Investigative reporter Pang Jiaoming of the China Economic Times (中國經濟時報) was dismissed in October 2007 at the demand of the Central Publicity Department for publishing embarrassing reports about the conditions of China's railway infrastructure ahead of the "sensitive" Chinese Communist Party's 17th National Congress.[26] Freelance reporter Lu Gengsong was sentenced to four years in prison in February 2008 on charges of "inciting subversion" for stories he had written for overseas websites on corruption and the trial of a Chinese human rights activist.[27] At least 26 Chinese journalists are in prison due to their work, many on ambiguous charges including "revealing state secrets" and "inciting subversion," Committee for the Protection of Journalists statistics indicate.[28]

As a result, the majority of Chinese journalists produce news stories which reflect the safe reporting limits permitted by the system within which they operate. A Canadian journalist employed from April 2007-April 2008 at the English-language China Daily, the Chinese government's flagship publication for foreign readers, described self-censorship as the norm among his Chinese colleagues. "Reporters here simply know what they can and cannot write-and they don't challenge those limitations. Change isn't coming from the bottom and certainly isn't coming from the top."[29]

Chang Ping, a former editor and columnist of the Southern Metropolis Weekly, wrote in an April 2008 entry on his personal blog, titled "My cowardice and impotence," of the realities of China's institutionalized media self-censorship.

I am afraid of other people praising me as a brave newspaperman, because I know I am full of fears in my heart. I did write some commentaries on current affairs, and edited some articles that exposed truth….however, to be honest, these were exceptional cases. They were my miscalculations. In my various media positions in the past decade, what I've practiced most is avoiding risk. Self-censorship has become part of my life. It makes me disgusted with myself.[30]

Within weeks of writing this, Chang Ping was dismissed from his job.[31]

The Chinese government's new "Regulations on Government Information Openness," approved in January 2007, do little to boost transparency and reduce the risks Chinese journalists face in doing their jobs. The "Regulations on Government Information Openness" allow officials to block the release of any information judged to be secret, or that might "threaten national, public or economic security or social stability."[32]

The circumstances for foreign journalists in China have not been significantly better. For decades their ability to report was hindered by official rules which severely restricted their freedom and mobility. Those rules included the need for official permission to travel outside of Beijing or Shanghai, where the majority of the more than 700 foreign journalists from 374 news organizations[33] are based, and a requirement of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) approval for any interviews with Chinese citizens.[34]Those rules effectively forced foreign journalists to operate in a legal "gray zone" and subjected them to detention and interrogation by Chinese police if discovered reporting in violation of official restrictions.[35]Foreign journalists who ventured into the countryside without MOFA approval risked being stonewalled by the local governments whom they tried to interview, or being detained and required to write a "self-criticism" of their "illegal" actions as a condition of their release.

Government Promises of Media Freedom for the Olympics

China's bids to host an Olympic Games through the 1990s were unsuccessful in part because of the government's poor human rights record. In a 2001 effort to ameliorate concerns of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Wang Wei, secretary-general of the Beijing Olympic Games Bid Committee, insisted that international media would have "complete freedom to report when they come to China" for the Olympics.[36]The IOC clearly found such pledges compelling.

Part of [Beijing's] representation to the IOC members was an acknowledgement of the concerns expressed in many parts of the world regarding its record on human rights, coupled with a pre-emptive suggestion that the IOC could help increase progress on such matters by awarding the Games to China, since this decision would result in even more media attention to the issue and likely faster evolution. It was an all-but-irresistible prospect for the IOC.[37]

Beijing was awarded the 2008 Games shortly thereafter.

In August 2006, Jiang Xiaoyu, executive vice-president of the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (BOCOG), told a press conference that the Chinese government would, if necessary, change rules governing media in China "if our existing regulations and practice conflict with Olympic norms."[38] That December, the Chinese government announced that the most onerous restrictions on foreign correspondents' reporting freedom-the need for official permission to conduct interviews-would be temporarily lifted in the run-up to and during the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing. The temporary regulations for media freedom for foreign correspondents-which do not extend to their local staff or Chinese journalists-are set out in the "Service Guide for Foreign Media," published on the BOCOG website. [39]

The temporary regulations, in effect from January 1, 2007 to October 17, 2008, permit foreign journalists to freely conduct interviews with any consenting Chinese organization or citizen and "shall apply to the coverage of the Beijing Olympic Games and the preparation as well as political, economic, social and cultural matters of China by foreign correspondents in conformity with Chinese laws and organizations."[40]

When you travel, you enjoy the same rights as all foreign nationals in China. When you interview a person or a company, you do not have to apply to the local foreign affairs office for permission, and they don't have the responsibility of asking, "What are you doing here?"[41]

The regulations drew initial praise from some correspondents for lifting longstanding obstacles to access to certain political dissidents, including Bao Tong, a former top aide to disgraced former Chinese Communist Party Chairman Zhao Ziyang, and to human rights activists, including the husband-and-wife team of Hu Jia and Zeng Jinyan. Some correspondents also say the rules have served at times as a valuable tool in fending off government officials and security forces who reflexively still seek to restrict the operations of journalists outside the major cities. "The temporary regulations make a lot of difference… you worry less [because] you can say to people 'I have a right to be here,'"[42] one correspondent told us.

Despite the initial improvements, however, there were dozens of incidents of interference with journalists in the first six months of 2007 by government officials, security forces and plainclothes thugs, as well as some cases of direct intimidation by MOFA officials. Overall, the Foreign Correspondents Club of China (FCCC) recorded more than 200 incidents of official interference with the activities of foreign correspondents between January 1, 2007, and the end of April 2008.[43]

Assessment of Media Freedom since August 2007

Since mid-2007 the situation appears to have worsened. Many foreign correspondents we spoke with say they continue to face serious obstacles whenever the issues on which they wish to report are deemed "sensitive" by central or local authorities. The ongoing closure of Tibet to foreign journalists offers the starkest illustration of this point. In some cases, officials have attempted to extort positive coverage from journalists by threatening to withhold their accreditation to cover the Olympics. Evidence suggests that the frequency of incidents in which government officials and security forces have sought to intimidate correspondents' local sources have risen over the past year. The Foreign Correspondents Club of China has complained that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has declined to investigate anonymous death threats against at least 10 foreign journalists in March and April 2008.

The picture is not uniformly negative. Human Rights Watch interviewed several correspondents who praised MOFA for interceding on their behalf in recent months when they encountered official obstructions to their reporting. A television journalist detained by local officials in Anhui on November 9, 2007, credited the assistance of MOFA officials in both Beijing and Anhui in brokering her release from three hours of detention by local government officials. "I called MOFA and they asked where we were and said they would [get us released]. …[MOFA] kept checking in over the next 2-3 hours with the message that 'help is on the way.'"[44]

Unfortunately, the Chinese government's response in the majority of cases documented in this report, and in reports of the Foreign Correspondents Club and other organizations, has not been positive. Instead, correspondents have faced evasiveness, denial, and recrimination. Sun Weija, BOCOG's media chief, responded to queries in October 2007 about the lack of effective implementation of the temporary regulations by attributing such incidents to lack of knowledge of the new rules at "lower levels" of the Chinese bureaucracy.[45] Moreover, in March 2008, China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs alleged, without substantiation, that foreign journalists had attracted justifiable official interference in their activities due to their "reporting style," violations of Chinese law and fabrication of news stories.[46]The Chinese government has not publicly disclosed whether it has conducted any investigations, disciplinary actions, or prosecution of officials or security forces who have abused the reporting freedoms of correspondents.

Government officials have implied that the temporary rules may be made permanent rather than expiring on October 17, 2008. "If practice shows that the regulation will help the international community to know China better, then it is a good policy in accordance with the country's reforms and opening up," State Information Office Minister Cai Wu told reporters in December 2007.[47] This is an important commitment, and one that the international community should encourage. However, simply making the temporary regulations permanent will not improve media freedom in China, if present practice is any indicator. The regulations must be respected and enforced, and must be extended to cover Chinese journalists as well.

Also disappointing has been the IOC's inability or unwillingness to effectively press the Chinese government on its failure to enforce the temporary regulations. Not only was foreign media access a key issue in the decision to award China the Games, but Article 49 of the Olympic Charter explicitly commits the IOC to take "… all necessary steps in order to ensure the fullest coverage by the different media and the widest possible audience in the world for the Olympic Games."[48]

Although the IOC is aware of the more than two hundred documented cases in which foreign journalists have been harassed, intimidated, or otherwise abused, it has declined in its public remarks to raise these cases, and instead has tended to be congratulatory of the Chinese government. In September 2007, Anthony Edgar, the IOC's Olympic Games Media Operations chief, said, "The Chinese government committed itself a long time ago to media working in China as freely as in other countries, in accordance with IOC and international practices and I think they are working well at the moment."[49] In February 2008, IOC president Jacques Rogge praised the Chinese government for the temporary regulations on media freedom and summarized their implementation by stating "the glass is half full" without addressing multiple and ongoing abuses of media freedom in China.[50]

Two months later, when foreign journalists were barred from the TAR and neighboring provinces and correspondents were the target of death threats amid ongoing state-media-driven vilification of foreign media "bias," the head of the IOC press commission, Kevan Gosper, praised the "open-mindedness" of the Chinese government in "supporting the interests of Chinese journalists as well as international journalists."[51]On April 3, Hein Verbruggen, chairman of the IOC coordination commission, told reporters that the IOC could "easily prove" that awarding Beijing the right to host the 2008 Olympic Games had improved China's human rights situation, but did not provide any evidence in support of that claim.[52]

International criticism of the Chinese government's blatant violations of its Olympics-related commitments to media freedom in Tibet and neighboring provinces since mid-March 2008 prompted Rogge on April 10, 2008, to concede that implementation of the temporary regulations was inadequate, and he urged Chinese officials to improve their practices "as soon as possible."[53] Weeks later, Rogge indicated that protests related to China's violations of its Olympics-related human rights commitments would prompt the IOC to "think about its role in society differently…[and] think of our activities in terms of human rights," without providing any details about possible future changes in IOC policies and pledges with regard to Olympics host city human rights conditions.

The failure of the Chinese government and the IOC to address ongoing violations of the temporary regulations prompted Human Rights Watch, in collaboration with the Committee to Protect Journalists, to produce a guide book for the estimated 30,000 foreign journalists who will cover the Beijing Olympics. This guide book explains the risks those journalists and their local staff and sources will face, and how to minimize the risks. The FCCC has produced a similar electronic document available on the club's website.[54]

III.Threats to Deny Olympics Accreditation and Ongoing Violations of the Temporary Regulations

The last year or so has been like a laboratory on what the government should do [with foreign journalists]…detain, interrogate? It's been like the marketing of a product called "freedom for journalists" and if it doesn't work for [officials], they just tinker with it so that it does work for them.[55]

In some cases, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has responded to reporting which displeases it by threatening reporters' visa status or the accreditation of their overseas-based colleagues hoping to cover the Beijing Olympics in August 2008.

Accredited foreign correspondents based in China are generally issued a renewable, multiple-entry one-year work visa, and the annual renewal process, which includes a short interview with foreign ministry visa issuance officers, is usually short and perfunctory. However, foreign journalists told Human Rights Watch that MOFA officials have delayed processing visa extensions and have threatened to deny Beijing Olympics accreditation to their foreign-based colleagues after the journalists produced what officials viewed as "unflattering" reports about China.

A foreign television news correspondent told Human Rights Watch that in November 2007 she and her bureau came under intense MOFA pressure, including threats to deny accreditation for the Olympics to the broadcaster's foreign-based staff, after the reporter had publicly complained about being harassed and detained by government officials in Anhui province. Her remarks had been carried on the website of the Foreign Correspondents Club of China. Ironically, the journalist had explicitly expressed appreciation in her remarks to MOFA officials who had helped to broker her release after three hours of detention by Anhui government officials. A "furious" MOFA official contacted the correspondent and said, "'we have a special relationship with [your bureau], but now this special relationship won't exist.' The implicit message was that the next time we're in trouble in the countryside, [MOFA] won't help us."[56]

The same correspondent later discovered that MOFA officials also informed one of her bureau's local producers that MOFA approvals of Olympics-coverage accreditations for the broadcaster's foreign-based staff were in jeopardy unless the correspondent issued a public apology or correction. The correspondent refused to do so and remains concerned about possible delays or rejections of Olympics-coverage accreditations for the broadcaster's foreign-based staff.[57]

In November 2007, a Beijing-based foreign correspondent wrote an item in her newspaper's online gossip blog about rumors involving the alleged marital infidelities of a former Chinese leader. Days after writing the piece, MOFA officials informed the correspondent that the processing of her annual visa renewal had been delayed due to heavy application volume.[58] When the correspondent called a MOFA contact a few days later to inquire about the progress of her visa renewal, she was informed that approval of her visa remained delayed due to government anger over her recent blog entry. MOFA officials refused to renew the visa until late December, a process which took weeks instead of the usual 5-7 working days. MOFA also denied applications by the correspondent's colleagues to interview MOFA personnel on matters unrelated to her delays in her visa renewal.[59]

In addition, MOFA personnel also told the correspondent that failure to resolve the foreign ministry's concerns with her blog entry might "threaten the status" of accreditation for foreign-based staff of her newspaper who had applied for Olympics-coverage press passes. The intimidation climaxed when MOFA demanded that the correspondent come to the foreign ministry on December 25. During that meeting, MOFA officials showed her copies of her blog entry with sections they claimed "had intentionally insulted China" highlighted. The officials initially made the blog entry's deletion from the newspaper's website a condition of the correspondent's visa renewal, a condition which the correspondent rejected. To the correspondent's surprise, shortly after that meeting, a MOFA official told her that her visa renewal would be processed later that same day.[60]

The correspondent's visa was renewed that day, but the delay and subsequent MOFA harassment has made her highly conscious of the foreign ministry's power to influence foreign media coverage through threats to delay or deny visas and media accreditation.

This was harassment. This visa issue was pressure to report the 'right' news. They don't say it explicitly, but they make you understand that.[61]

Another foreign correspondent who renewed his visa at the end of 2007 said a visa issuance official indicated during the requisite renewal interview that the government was displeased by the reporter's recent coverage of the plight of petitioners-rural residents who come to Beijing to seek legal redress for local grievances, including police brutality and illegal land seizure. "The [visa officer] said 'What are you doing with these troublemakers all the time? Why do you talk to these petitioners?' He spoke in a jocular fashion, but I could sense there was an underlying edge."[62] The correspondent's visa was renewed, but he interpreted the interviewer's questions as a veiled threat as to how the reporter's news coverage could affect his visa status. The journalist continues to pursue such stories despite that veiled threat.

Correspondents George Blume and Kristin Kupfer of the German newspaper Die Tageszeitung were the last foreign journalists expelled from Lhasa following increasingly violent protests which began on March 14, 2008. On March 18, 2008, Blume and Kupfer were told that their visa accreditation for China would be withdrawn if they didn't comply with official demands to return to Beijing.[63] Blume and Kupfer subsequently discovered that local security government officials and police had instructed their hotel and other local hotels in the city to refuse them accommodation in order to ensure that they left Lhasa on March 18.[64]

Ongoing Violations of the Temporary Regulations

Foreign correspondents say that between January and June 2007, the first six months in which the temporary regulations were in effect, officials typically claimed they were unaware of the existence or relevance of the regulations when violating the temporary restrictions on media freedom.[65] Over the past year, many journalists say, officials' tactics have changed. Rather than denying the existence of the regulations, government officials and security officials now come up with pretexts to justify their interference or they simply refuse to uphold the regulations consistently. "No matter how much you complain and wave around the rule book, they just say they're enforcing Chinese law, but it's a very nebulous interpretation of law as far as journalists are concerned."[66]

A foreign television journalist in Beijing said that the police's use of constantly expanding perimeters of yellow police tape around the site of a housing demolition protest in October 2007 successfully frustrated her efforts to get usable footage for a story she was doing on the topic. The police declined to provide justification for their actions.

My whole purpose was to interview protesters, but [police] kept putting up police lines and separating us from the protesters and pushed us farther and farther back with multiple police lines. When I got back to the office my producer looked at the footage and said "Is this all you got? It's so far away [from the action]!"[67]

A European television journalist, who was detained and beaten by plainclothes thugs while doing a story on civil unrest in Shengyou village in Hebei province in October 2007, said a local MOFA official insisted that she was legally at fault for the incident. The official attributed the incident-which ended with the erasure of interview footage shot in the village-to the journalist's "misinterpretation" of the temporary regulations, which the official falsely claimed required "an invitation" to even access the village.[68]

A Beijing-based television correspondent told Human Rights Watch that security officials and plainclothes thugs who appear to be operating at official behest increasingly try to incite local villagers to obstruct his work by physically blocking his access to areas of news interest or interviewing local sources. "This is happening more and more with [plainclothes thugs] shouting that we are 'harming China [or] doing a bad story about China and must be stopped' [in order to] get other villagers involved."[69]

An American television crew detained on March 16, 2008, by police near AbaCounty in southwestern Sichuan province, where there had reportedly been protests by Tibetans, said police attempted to twist the temporary regulations requirement of "interviewee consent" in an effort to force the crew to surrender tapes of their footage, including that of their detention by police. "We refused to let them see our tapes and trotted out the [temporary regulations], but the police responded by saying that they weren't 'consensual' subjects in the footage we had shot of them."[70]The police gave up on their demand to view the crew's footage only after four hours of negotiations.[71]

The temporary regulations do not alter the legal requirement that foreign journalists carry their passports and their Ministry of Foreign Affairs official press cards with them at all times. But foreign journalists told Human Rights Watch that in late 2007, government and security officials began making demands for correspondents' personal identification, not stipulated by Chinese law in an apparent bid to delay and impede coverage of breaking news stories.

A European journalist said that her efforts to cover protests related to housing demolitions in central Beijing in September 2007 were hampered by a pair of uniformed policemen who detained her because she was not carrying her household registration certificate. Foreign correspondents are not required by law to carry such certificates, which are official documents verifying the residential status of foreign residents in Chinese cities. The foreign journalist said the police who detained her dismissed her assertions that her passport and press card were adequate identification documents, and refused to take a phone call from an official at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who agreed to speak on the journalist's behalf. When the journalist protested that she had done nothing illegal under Chinese law, one of the two policemen responded, "I'm the law."

Another foreign journalist at the site of a separate housing demolition protest in central Beijing in October was likewise detained and impeded from reporting when police on the scene demanded to see her household registration permit, which she did not have. "This is a new and interesting tactic, especially in big cities like Beijing. The tactic is to delay [journalists], to ask for ever-increasing amounts of identification in order to pull the reporter away from the scene of [news] events."[72]

IV.Silencing the Sources: Intimidation of Chinese Interviewees

The temporary regulations haven't stopped [government officials and security forces] from limiting what we do, but they now do it differently and instead they harass the [sources] we deal with. They see the people we talk to and they go and warn them [not to do it again].[73]

Citizens have the rights to express their ideas under the legal system, which includes suggestions to and criticisms on the government. The rights are protected by law and Constitution.[74]

-Supreme People's Court vice-president, Zhang Jun, March 2008.

Journalists rely on sources-people who can provide first-hand experience or eyewitness accounts of a particular event or phenomenon-in order to accurately and reliably report the news. Government officials and security forces have traditionally used intimidation and harassment of local sources, which are more easily controlled than foreign journalists, as a means of preventing the dissemination of "sensitive" news through foreign media.

Foreign journalists say that the freedom of movement granted to them by the temporary regulations has increased the number of local sources to which they have access to, but has correspondingly increased the vulnerability of those sources to reprisals from officials, security forces or plainclothes thugs.

In the past 12 months, correspondents say, their sources have been increasingly subject to official repercussions ranging from possible deportation to physical abuse and threats of criminal prosecution. In several cases, correspondents say that officials interrogating them focused on obtaining the names, mobile phone numbers and locations of their local sources. That intensified pressure on sources appears to be an intentional tactic by government officials and security forces to maintain a veneer of freedom for foreign journalists while seriously undermining their capacity to report effectively.

A foreign television journalist who was doing a story on North Korean refugees seeking sanctuary in China learned the price that sources for "sensitive" stories can pay when detected by the authorities. The correspondent was detained in the city of Shenyang in northeastern Liaoning province on March 5, 2008, by plainclothes police who confiscated the correspondent's tapes which held interview film footage of North Korean refugees he'd interviewed in the city.[75] Police apparently located and detained at least three of those refugees that same day by viewing the tapes. The correspondent said the refugees were last seen "on a police bus at on March 6, 2008."[76] Given the Chinese government's practice of forcibly repatriating many undocumented North Koreans, despite the severe penalties including imprisonment and torture on return, the fact that these refugees' fate is unknown is of grave concern.[77]

Journalists' sources can run serious risks even in relation to fairly innocuous business-related stories. In March, a foreign television news crew did an on-camera interview with an aggrieved former investor in a collapsed pyramid scheme in the northeastern city of Shenyang. The crew learned later that their source was picked out of a meeting of fellow former-investors by uniformed police who beat him so severely he required hospitalization. The source was then briefly put under house arrest following his release from hospital.[78]

A foreign correspondent who, in November 2007, traveled on a government-organized media tour focused on the relocation of local residents adjacent to the Three Gorges Dam project in Hubei province discovered that independent interviews she had conducted brought swift repercussions to one of her local sources. "The next day the interviewee contacted me and said local officials came looking for him and asked why he'd said 'negative things' about the relocation."[79] The source said the officials had detailed knowledge of the substance of the previous day's interview, prompting the correspondent to conclude that government officials or security forces had surreptitiously eavesdropped on the conversation. "It's a constant worry to go to talk to [local sources] because some of these local officials can be very vengeful."[80]

On September 29, 2007, Sami Silanpaa, the China correspondent for the Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat, began to interview the head of a local nongovernmental organization which provides legal assistance to migrant workers in Shenzhen. Within ten minutes of his arrival at the NGO's office, "Two policemen, one in uniform, one in plainclothes, entered the office and said they needed to take the [source] to the police station." Silanpaa continued, "Later he told me he'd been asked about me…and warned that he shouldn't tell foreigners anything."[81] Police awareness that the interview was taking place suggested electronic surveillance of the correspondent, the source, or both. "The police could only have known I was doing the interview if they were tapping my phone or [the source's] phone."[82]

Foreign journalists' sources also face risks to their livelihood from vengeful local officials who are displeased with the resulting coverage. A foreign correspondent told Human Rights Watch that a local source working for an international nongovernmental organization focused on poverty relief projects in western China, was subsequently fired from her job as a result of her cooperation with the journalist.[83] The fact that the correspondent had received official permission from the local government to do interviews with staff at the organization and report on their work did not protect the source from reprisal from local government officials who were angered by the source's cooperation with the journalist.[84]

When I returned to Beijing, I was told by my source that she had been fired because of [local] government pressure [because] it had gotten angry with the [international poverty relief group] and it was [a choice] of either firing her or closing down their [operations]. The problem for me now is that in this case we did ask for [official] permission [for interviews] and it was granted…and they told me clearly that regulations allow foreign journalists to interview whomever they want, if the other side consents. But for this woman, [that interview means] she has lost her job.[85]

A local source of another foreign television crew was subjected to severe intimidation by local police in connection with a February 2008 story on environmental pollution. In an effort to protect the source, the television crew went to extreme lengths to remove any links he had to their source by cutting the footage of his on-camera interview and not using any information that could be linked directly to him.[86] Despite those precautions, shortly after the journalists left the area, members of the local Public Security Bureau visited the source and warned him that they would charge him with state subversion[87]if they had evidence that he had provided the journalists with any "sensitive" information.[88] Those threats prompted the source to flee his village twice for weeks at a time. The source has since returned to his home village without any official reprisals, but the incident has caused the correspondent to seriously question the feasibility of "safe" reporting in China.

Sources aren't secure at all… [the authorities] can take out [their revenge] on the people who work for you, who show you the way. Those potential reprisals set the bar for [television] reporting uncomfortably high because it's very hard to assess before you go in whether or not a story is 'worth it' [in terms of risk to sources]. In order for me to do a story, I need to individualize it, to focus on one person who tells a story which can resonate with people, but under the current circumstances I can no longer do that.[89]

Police threats of "subversion" charges against journalists' sources are particularly potent in the wake of the conviction of high-profile human rights activist Hu Jia for "subverting state power" on April 3, 2008. The prosecution's case against Hu included evidence related to interviews he had given to foreign journalists.[90] One veteran foreign correspondent said that the circumstances of Hu's conviction would likely worsen de facto self-censorship among foreign correspondents who don't want to risk putting their sources in danger of criminal prosecution and imprisonment.

For me, this means that if a [journalist] interviews someone, the interview can become evidence in court to charge [the source]. Simply expressing views can be "subversion," so it makes a journalist question, "Do I publish what this person is saying? Or not publish what he says and [therefore] not reflect what's going on in China?"[91]

Some of those meting out intimidation and abuse have been explicit about the relationship between potentially negative press coverage and the government's desire to project a positive image for the Olympics. A local source of a foreign television journalist who was filming a story on environmental pollution in Hebei province in March 2008 was subjected to intimidation from "well-spoken, but thuggish" people who declined to identify themselves. The correspondent suspected they were local government officials[92] by their style of dress and demeanor. The group became "problematic" during filming at a reservoir by closely following the television crew and walking into camera shots. The correspondent's local source offered to speak with the group in their car to try to defuse any tensions. "He got out of the car quite shaken and said [the thugs] had said 'This [year] is the Olympics, so you shouldn't be taking foreigners around.'"[93]

V.The Closure of Tibet

When the Tibet unrest happened, [the Chinese government] lost its nerve and went back to its traditional default position with regards to the foreign media, which is: "Don't let anyone see anything."[94]

-Beijing-based foreign correspondent, Beijing, March 29, 2008.

Media freedom also continues to be restricted geographically. The situation in Tibet today illustrates the range of controls officials can apply when they perceive a threat. The picture is one of deliberate, orchestrated closure of Tibetan areas, with journalists scrambling to avoid obstacles at every turn. Their efforts are ultimately frustrated by official persistence in keeping them away from the "sensitive" areas.

Access for foreigners, and particularly foreign journalists, to Tibet has been closely circumscribed since the Chinese People's Liberation Army entered central Tibet[95]in 1950.[96] Tibetans refer to the events of 1950 as an "invasion," while the Chinese government refers to it as the "peaceful liberation" of Tibet.[97]

China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs has long required foreign correspondents who want to do reporting trips to Tibet to apply for permission, a process which journalists describe as lengthy and frustrating.[98]The temporary regulations contain no geographical restrictions,[99] but were superseded in February 2007 when MOFA stated that correspondents' access to Tibet still requires specific MOFA permission due to "restraints in natural conditions and reception capabilities" across Tibet.[100]

Several foreign journalists who tried to visit Tibet in 2007 were denied access at entry points by government officials and security forces and have been intimidated by MOFA officials. McClatchy Newspapers' China correspondent Tim Johnson, who made an unsanctioned trip to Tibet in May 2007, said that a MOFA official delivered a verbal reprimand, accusing him of false reporting "unacceptable" to the Chinese government.[101]Even foreign journalists with official permission to report in Tibet were blocked at times by local officials and correspondents on MOFA-organized trips, faced micro-managed schedules which interfered with independent reporting, and the constant presence of official guides or minders who intimidated potential local sources.

In March 2008, access to Tibet and Tibetan communities in neighboring provinces for foreign correspondents was shut off altogether, with the exception of five government-organized and controlled tours.

The March 2008 Protests in Tibetan Areas

On March 10, 2008, hundreds of monks from Drepung monastery, five miles west of the Tibetan capital Lhasa, began peaceful protests calling for an end to religious restrictions and the release of imprisoned monks as part of commemorations for "Tibetan Uprising Day," the anniversary of the Tibetan rebellion against Chinese rule of Tibet in 1959.[102] While marching toward the Drepung, protesters were stopped by large numbers of Chinese police, and media reports estimate that around 50 monks were detained.[103] The monks held a sit-down protest for some 12 hours before returning to their monastery. On March 11 at around , the sound of gunfire was heard emanating from the area of the monastery.[104]

Over the course of that week, similar protests erupted at Sera and Ganden monasteries, and Lhasa was rocked by unprecedented protests, including attacks by Tibetans on ethnic Han and their property. Chinese security forces, notably absent as the rioting got underway, eventually responded by beating protesters, firing live ammunition, and cutting phone lines into monasteries.[105] There have been reports that some protesters were shot.[106] The Chinese government claims that 23 people were killed in the riots, while the Tibetan government-in-exile claims 203 Tibetans have been killed in subsequent government crackdown.[107] The Chinese government quickly sealed Tibet and Tibetan communities in neighboring provinces with thousands of troops and police,[108] resulting in the surrender or arrest of more than 3,000 people in the first month following the unrest.[109]Protests by Tibetans swiftly spread in the following days to areas of the neighboring southwestern provinces of Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai, and Yunnan,[110] which are home to more than half of all ethnic Tibetans. According to one observer, "Chinese internal reports are said to have estimated that some 30,000 Tibetans took part."[111]

Expulsion of Journalists from Lhasa

The Chinese government's response to foreign media in the aftermath of the riots in Lhasa and in neighboring provinces was swift and uncompromising: journalists in Lhasa came under strong official pressure to leave or were forcibly ejected. Chinese government officials and security forces forced the few other foreign journalists who had managed to arrive in the aftermath of the violence out of the region by March 18. The temporary regulations were of no help to journalists here.

A group of Hong Kong text and television journalists were confined to their Lhasa hotel by police on the evening of March 15. A government official told the journalists that their reporting on the protests was "out of line" and ordered them to leave Lhasa the next day.[112]The journalists were dispatched to the airport in a special minibus and accompanied by two Tibetan government officials "to ensure we all got on the flight."[113]

German correspondents George Blum and Kristin Kupfer left by train from Lhasa to Xining in Qinghai province on March 18. Their departure was prompted by threats from immigration officials that the two journalists' official press accreditation to China would be withdrawn if they didn't leave the city.[114]

James Miles, a China correspondent for The Economist, happened to be on an officially-sanctioned visit to Lhasa during the protests, and provided eyewitness accounts to western media of the ransacking and burning of Chinese owned shops and brutality by Tibetan rioters against Han Chinese migrants in the city.[115] He was permitted to stay in Lhasa until the scheduled conclusion of his official tour on March 19, 2008.[116] Miles believes he was allowed to complete his Tibet trip because MOFA personnel liked his reporting on Tibetan violence against Han Chinese and they did not want the negative publicity of forcing out a correspondent with official permission to be in Lhasa.[117]

Foreign journalists who flew into Lhasa on March 15 were put back on flights to Chengdu in Sichuan province, the regional air hub for flights to Tibet.[118]

Obstacles for Journalists Trying to Reach Tibetan Areas

The temporary regulations were equally useless to correspondents trying to reach Tibetan communities in the neighboring provinces of Gansu, Sichuan, Qinghai and Yunnan provinces, where no additional geographical constraints should apply. Although there were no official announcements of extraordinary legal circumstances which might warrant an obstruction, such as a declaration of martial law, the Chinese government also moved quickly to block foreign correspondents from accessing Tibetan communities in these provinces.

The Chinese government offered vague justifications for sealing off Tibetan areas from foreign journalists. On March 20, MOFA defended its prohibition as legally-justified "special measures in line with the law" and asked that journalists understand and cooperate with the new restrictions on their freedom to report.[119]

The Regulations allow free reporting by foreign journalists in China, however, there is no absolute freedom anywhere in the world. Besides, Article One of the Regulations stipulates that these regulations are formulated to facilitated reporting activities by foreign journalists in China in accordance with the laws of the People's Republic of China. We hope foreign journalists abide by Chinese laws and relevant regulations.[120]

The foreign ministry has consistently declined, however, to specify the precise legal basis for the prohibition on correspondents' access to Tibet and neighboring provinces, and the laws which allow the government to supersede the authority of the temporary regulations. The Chinese government has subsequently altered its justification for the ban on foreign media access to those areas by citing unspecified concerns about journalists' "safety,"[121] noting "security issues and other issues."[122]Many foreign journalists remain puzzled by such statements, given that most of the threats they have encountered have come from government officials themselves.

Foreign correspondents who attempted to get from their Beijing or Shanghai bases to cover one of China's most serious outbreaks of civil strife since the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989 were barred from flights, stopped at roadblocks (where their drivers were intimidated by local security authorities), and even detained. Within days, a significant portion of western China was sealed off from the eyes of foreign journalists.

The FCCC, which in 2007 recorded 180 separate incidents of reporting interference including detention, intimidation, and harassment across China, documented more than 50 such cases in western China in the two-week period following March 14.[123] The challenges facing foreign journalists in trying to report the story were aptly summarized by veteran China correspondent Jonathan Watts of the U.K. newspaper The Guardian.

Trouble has been breaking out hundreds of miles apart in an area roughly the size of Western Europe. Chasing the incidents is like racing from London to Zurich to Lisbon, while trying to dodge the police and avoid putting sources in danger at the same time. In the past seven days, we have taken seven flights, been driven for 30 hours and covered a distance roughly equivalent to 10 times the length of Britain. Security restrictions haven't helped. I have twice woken-up before dawn to avoid checkpoints on six-to-eight hour journeys that ultimately ended in failure, when the police stopped me, found I was a journalist and sent me back.[124]

With direct travel to Lhasa and the rest of Tibet prohibited, foreign correspondents quickly booked flights to transportation hubs in southwestern China, including Chengdu, Gansu province's Lanzhou and Yunnan province's Kunming, in the hope of arranging land transportation to areas of Tibetan protests. But some foreign journalists found that the authorities were unwilling even to permit them to board the flights.

Public Security Bureau officers refused to allow a Beijing-based foreign correspondent to board a flight on March 19 from Kunming to Lhasa for "security reasons." He was blocked by security officials again the same day when he tried to get on a flight from Kunming to Zhongdian, which was of interest for its large ethnic Tibetan population and its proximity to parts of Sichuan province where there had been protests. "When I tried to go to Zhongdian, police with submachine guns and flak jackets [at the boarding gate] said I couldn't go for 'safety reasons' and they were also turning back [foreign] tourists from boarding."[125]

A Shanghai-based foreign correspondent who likewise attempted to fly to Zhongdian from Yunnan on March 18 was blocked by police who demonstrated a surprising level of knowledge of his movements toward Zhongdian. The correspondent said that they had tracked him through analysis of airline data.[126]

At the airport the police were waiting for me at the [airline] check-in counter, 10 uniformed police, some with machine guns. They greeted me with "You must be [the correspondent's name]" and when they looked at my ticket I overheard one of them say "Oh yes, he's just recently been to Hong Kong,"…so they obviously got my name from the airline passenger manifest. We had a routine argument…but I had no luck boarding the flight.[127]

Several correspondents also said that their drivers-essential for reaching more remote areas of these provinces-were often the first target for police intimidation or subterfuge.

A three-person foreign television news crew which had successfully traveled from Xining, Qinghai province, in the early hours of March 16 to the Tibetan community of Gonghe were detained that same afternoon by two car-loads of uniformed local Public Security Bureau (PSB) officers. The PSB insisted that the journalists needed to accompany the police to the local station "to check our credentials."[128] The police checked the journalists' press cards and passports, but directed most of their attention toward the journalists' driver. "[The request to check our credentials] was a ploy. They gave our driver a good talking-to, and he said that [the police] made him aware of the fact that they didn't want him to go anywhere [potentially sensitive]."[129] This intimidation, along with being tailed by an unmarked police car all day, sabotaged the journalists' efforts to report.[130]

A Shanghai-based correspondent who flew to Lanzhou on March 15 en route to report on Tibetan unrest in other parts of Gansu province believed that some of the city's taxi drivers had been replaced by plainclothes police, or had been temporarily paid to double as police informers. The taxi driver who picked up the correspondent from the Lanzhou airport appeared to intentionally surrender the journalist to police who were recording the entry of foreign correspondents into the city.

The cab driver who picked me up [at the airport] said right away "Oh, many journalists are coming to Lanzhou today," but I hadn't even told him that I was a journalist. Then the cab driver said "I think we're being followed, I should call the police!" Actually behind us was another taxi with two other foreign journalists. Within a few minutes, plainclothes police showed up and looked at our passports.[131]

The plainclothes police did not detain the journalists, but merely documented their passport details as part of what appeared to be an official surveillance program of correspondents in Lanzhou.[132]

Police in these provinces also openly pressured some taxi drivers to limit the destinations to which they would take foreign correspondents. A Beijing-based foreign correspondent who successfully traveled overland from Lijang to Zhongdian in Yunnan province discovered that police who had waved him through a checkpoint into Zhongdian had instructed the driver to ignore the correspondent's destination requests, and instead drop him off at the local headquarters of the Public Security Bureau.[133] When the driver revealed the plan to the foreign journalist, after he had complained that the driver wasn't stopping at a local hotel as requested, the correspondent "threw him the fare and took off" in the middle of an intersection.[134]

Beijing-based correspondent Richard Spencer of The Telegraph was also subjected to police efforts to control his movements in Gansu province on March 17. Spencer had ended up in Gansu's Hezuo city that day after three days of repeated incidents of harassment, detention, and intimidation, including being turned back at a police roadblock on March 15 en route to Xiahe from Lanzhou. Spencer was also detained and interrogated by "very aggressive" submachine-gun toting police outside the town of Luqu in Gansu on March 16, and forcibly transferred from his rented vehicle to a police minivan that same day and transported to Hezuo, Gansu province, against his will. That interference occurred while Spencer was attempting to cover reported Tibetan unrest in the province and in neighboring Sichuan.[135] On March 17, an individual who Spencer identified as a plainclothes policeman repeatedly interfered with Spencer's efforts to hail a taxi outside his hotel to take him to Lanzhou to board a flight back to Beijing. The plainclothes policeman insisted Spencer take a public bus to Lanzhou on the basis that the bus's fixed route would prevent Spencer from attempting to independently slip back into neighboring Tibetan communities.[136] Spencer was eventually allowed to get in a taxi, but the policeman ordered the taxi driver to personally contact the policeman by phone when Spencer had been dropped off at the Lanzhou airport.[137]

Foreign correspondents reported that, beginning on March 15, government and security officials converted toll points on main roads running north out of Chengdu, Lanzhou, and Xining into roadblocks designed to block access by foreign travelers, particularly journalists. These were controlled by government officials, uniformed, and plainclothes police who scrutinized the passengers of incoming vehicles for foreign passengers. Local travelers were permitted to continue their journeys unimpeded.

A Beijing-based foreign television journalist trying to get to the town of Xiahe in Gansu, where there had reportedly been Tibetan protests, was forced to abandon the main roads leading to the town due to those roadblocks. "70 kilometers outside Lanzhou, all the toll points became roadblocks. We were told [by police at a roadblock] that Xiahe was 'closed' and our driver was told to take us back [to Lanzhou]."[138] The journalist was eventually able to reach Xiahe "after many hours and many [road-related] acrobatics" and on his way back noted that the roadblocks were focused strictly on incoming vehicles and ignored cars leaving the area.[139]

Police at a roadblock from Lanzhou to Xiahe on March 15 told another Beijing-based foreign journalist that although they were familiar with the temporary regulations, they insisted that those rules "didn't apply here."[140] The journalist then attempted to get assistance from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing. "We called MOFA and they said there was nothing they could do because under emergency circumstances, local authorities can prohibit foreigners from entry. This event really showed how powerless MOFA can be [in implementing the temporary regulations on media freedom]."[141]

A two-man foreign television crew was stopped on March 16 at a roadblock about an hour drive outside of Tongren, Qinghai province, where they had interviewed Tibetan monks at the local monastery. The uniformed police who stopped them politely but firmly dismissed the journalist's insistence that the temporary regulations gave them the right to freely report in the area.[142] The police required the journalists to get out of their own rented car and instead ride in a police car to a nearby police station. At the station, the journalists were denied the right to phone their bureau in Beijing.[143] They were allowed to phone MOFA for assistance, but the police who had detained them refused to speak to the MOFA official.[144]The journalists were questioned for hours and then released by the police who tried repeatedly, though unsuccessfully, to convince the journalists to show the police their Tongren interview footage.

Police and hotel staff in Litang, Sichuan province, assured a foreign journalist by phone that the town was open for foreigners to visit.[145] Despite those advance assurances, the journalist was detained three times in a single day by uniformed police who said Litang was closed to foreigners due to unspecified "dangerous" conditions.[146] Later that day, approximately ten minutes after the journalist reconfirmed with both a contact in Litang and the town's government authorities that the town was indeed open to visitors, two uniformed police showed up at his hotel instructing him that no foreigners could travel west toward Litang. "That message was either really good timing, or they'd listened in on my [phone] conversation a few minutes earlier," the journalist said.[147]

A foreign television journalist who had managed to evade roadblocks and discreetly enter the Gansu town of Xiahe on March 16 and 19 said that the security conditions imposed on the city made reporting impossible. "From Sunday to Wednesday they'd basically put a ring of steel around the city. Police and People's Liberation Army troops with staves blocked roads into Xiahe proper…and they were letting monks and civilians into the city one-by-one only."[148]

On the evening of March 15, Finnish Broadcasting Corporation (YLE) journalist Katri Makkonen went into a restaurant to evade the scrutiny of a group of people who had been following and videotaping her. Shortly after entering the restaurant, its owners closed its metal shutter door. Five minutes later, the shutter was opened from the outside and five plainclothes policemen entered, demanding to see her passport. One of the policemen carried in his hand the photocopied passport pictures of several journalists which he then attempted to use to identify Makkonen, suggesting that the police had used surveillance of mobile phone communications to discover what correspondents were in the area.[149] The police briefly detained her to record her press card and passport details and then released her. The next day, police detained Makkonen en route to the Gansu town of Hezuo and demanded to view her film footage, threatening to "confiscate" anything they deemed "sensitive."[150] When Makkonen asked about the possible consequences of defying this order, one of the policemen replied, "You don't want to know."[151]

Seven correspondents interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they faced demands by government officials and security forces to view and delete such footage after the crackdown on foreign journalists began on March 15, 2008. Four of those journalists lost valuable film footage as a result. A Shanghai-based foreign correspondent who took photographs of riot police outside of the Qinghai province town of Tongren on March 16 lost those shots within minutes when police detained the correspondent and deleted all the photos on the journalist's camera.[152] "They said photography there wasn't allowed," the correspondent said.[153]

By about March 20, many of the foreign correspondents attempting to cover the unrest in Tibetan areas had returned either to regional transportation hubs such as Chengdu or Lanzhou or to their bureaus in Beijing or Shanghai in the hope that reporting restrictions would soon be lifted. To date, however, those controls remain in place.

Government-Orchestrated Tours for Journalists to Tibetan Areas

In response to growing international concern about the crackdown in Tibet and threats of a resulting boycott of the Olympics opening ceremonies,[154] the Chinese government has granted select groups of foreign journalist's temporary access on four highly-circumscribed trips to Lhasa and a fifth to Gansu province since the March 14-15, 2008 protests. A group of foreign diplomats were permitted to take a similar trip on March 29-30, though in early April, the Chinese government refused a request by United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Louise Arbour, to visit Tibet to investigate the violence there.[155]

On the two-day Lhasa trip, which began on March 27, 2008, foreign correspondents said that foreign ministry officials who accompanied them kept a close watch on their activities and repeatedly attempted to discourage, but not prevent, their efforts at independent reporting. However, the constant surveillance which those correspondents endured during the visit made it difficult to freely conduct interviews without fear of possible repercussions to local sources.

To be fair to our minders, when we really pushed them, they let us go do our thing, but they didn't need to [directly obstruct us] because to go into Tibetan areas [of Lhasa] there were police everywhere and we had to continually show our passports. [Foreign ministry officials] didn't have to follow us because people watched us wherever we went.[156]

Another correspondent on that Lhasa visit said that government officials blocked journalists' access to key sites, including monasteries and the city's main mosque.[157]On March 28, 2008, foreign ministry officials tried to cut short foreign journalists' access to a group of monks who courageously approached the correspondents during their guided official tour of Lhasa's Jokang monastery and, in the brief moments available to them, told the journalists of serious ongoing persecution and repression. "When the monks approached us, the [MOFA] minders kept trying to pull us away, gently but insistently, citing a 'time schedule problem.'"[158]

The Chinese government's second media tour, from April 9-13, went to several towns in Gansu province. Potential local sources on the streets of the Gansu town of Machu were apparently very hesitant to speak openly to reporters within earshot of the correspondents' official minders. "Although the Chinese and foreign journalists were invited to interview people on the street in Machu most conversations quickly ceased as government officials accompanying the tour approached."[159] Tibetan monks at Xiahe's Labrang monastery who did approach foreign correspondents during that tour on April 9 and openly spoke of government repression were reportedly later "imprisoned, beaten and in some cases subjected to electric shock torture," as a punishment for speaking out.[160]

A Japanese news agency reporter and photographer who were given special Chinese government permission to visit Lhasa in April 2008 were also subjected to "very disruptive" constraints on their reporting freedom while in the city. The two journalists were "followed the entire time" by police while they were in Lhasa and denied access to monasteries to interview monks.[161] The government hosted a third "carefully scripted" four-day government-organized trip of foreign journalists to Tibetan areas which began in Lhasa on June 2. Correspondents on the trip noted a heavy police presence on the streets, similar to that seen during the late March visit.[162] The most recent government-organized foreign media trip to Lhasa was on the occasion of the June 21 Olympics torch relay. Correspondents "were confined to fixed points along the route" and not permitted to freely report.[163]