Summary

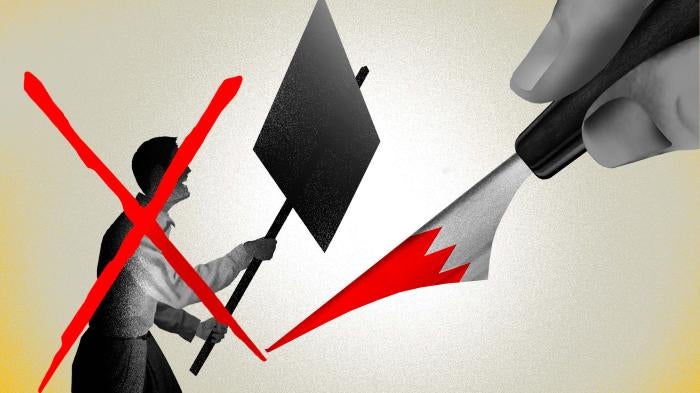

The façade that Bahrain’s autocratic rulers allow free and fair democratic processes has long worn away with years of repression. But in recent years Bahraini authorities’ marginalization of any political opposition has expanded into new spheres, utilizing a sophisticated, legal regime aiming to strangle what remains of Bahrain’s vibrant, independent civil society.

At the heart of the Bahraini state’s lawfare against its own citizens’ peaceful activism are its political and civil isolation laws passed in 2018. The laws bar former political opposition party members not only from running for parliament, but also sitting as members on the boards of governors of civil organizations. The government has also expanded practices that limit economic opportunities for former opposition members and prisoners through the routine delay or denial of “Good Conduct Certificates,” a document required for Bahraini citizens and residents to obtain employment, apply for university, or even join a sports or social club.

Opposition figures have borne the brunt of the government’s new tactics. The 2018 political isolation laws explicitly target members of previously dissolved political groups, as well as former convicts – even if pardoned or convicted on abusive speech or assembly related charges – and even those previously deemed to have “disrupted” constitutional life in Bahrain.

In 2016 and 2017, Bahrain’s judiciary dissolved the country’s two major opposition parties, al-Wifaq and Wa’ad. The 2018 political isolation laws introduced new punitive consequences in the aftermath of the dissolution of these parties by punishing individual members in perpetuity and excluding them even from non-political spheres of life in Bahrain. Former prisoners are also targeted by the law, which overwhelmingly targets activists and human rights defenders who were arrested in the government’s large-scale crackdown during and in the aftermath of the peaceful 2011 pro-democracy and anti-government uprising. The final clause of the political isolation law, concerning individuals who have “disrupted” constitutional life in Bahrain, has been interpreted by Bahraini lawyers and civil society to target former lawmakers and other individuals who resigned or boycotted their elected posts to protest repressive government policies.

There is no official data on the number of Bahraini citizens harmed by these laws. Bahrain’s Ministry of Justice has ignored requests from civil society to release accurate information on how many citizens have been punished under these laws. Civil society groups have made their own estimates using old party membership lists. Based on their estimates, between 6,000 to 11,000 Bahraini citizens have been banned, retroactively, from running for parliament and sitting on the boards of associations. The laws do not provide any means for targeted individuals to challenge the ban or seek remedies.

In 2010, Bahrain’s last parliamentary elections before the 2011 crackdown, al-Wifaq won 18 out of 40 seats. Under these laws, none of al-Wifaq’s candidates are allowed to fully participate in political and civil life today in Bahrain. There are also no time limits on these bans; all those who fall under them are effectively banned for life. The law also retroactively criminalizes participation in these opposition groups and any other dissolved political society. Even if an individual was only briefly a member of Wa’ad or al-Wifaq — just for a few months, many years ago, for example — they would be still subject to the ban today.

In addition to the political and civil isolation that these abusive laws impose on large numbers of Bahrainis, the government is using a form of economic sanction against these groups through the denial of “Good Conduct Certificates.” The certificate is not governed by law but rather administered by and issued at the discretion of the General Directorate of Crime Detection and Forensic Evidence within the Ministry of Interior. Former prisoners wait months or years for the certificate. Some opposition figures are denied the certificate outright, harming their ability to support themselves and their families.

One member of Bahrain’s civil society told Human Rights Watch that before 2011, “[the certificate] was easy to obtain, you [would] apply through the ministry and in a few days, it would arrive. But after 2011, everything changed.” A former political opposition member illustrated the consequences of this change, sharing, “a friend wanted me to be the head of the school, but the ministry refused the certificate so I could not work. The owner of the school was told by the ministry that they couldn’t accept me because I was a member of a political society.”

The political isolation law was first applied during the 2018 parliamentary elections, during which at least 12 former opposition figures were prohibited from running by Bahrain’s Ministry of Justice. Others, believing they would be a victim of the law, boycotted the elections altogether, resulting in even further scrutiny by Bahraini security agencies. One human rights defender was arrested for tweeting about boycotting the elections.

Bahrain’s upcoming parliamentary and municipal elections, scheduled for November 2022, offer little hope for any freer and fairer outcomes than in 2018. Since 2018, rights violations, including arrests and interrogations of Bahrainis for exercising their rights to freedom of expression and association have continued and the government has expanded its application of the political isolation laws.

This report analyzes the human rights abuses linked to this deliberate marginalization of opposition figures from social, political, civil, and economic life in Bahrain by documenting the application and effects of the political isolation laws, the denial of good behavior certificates, and detentions based on free expression violations. The report also assesses the long-term impacts of these exclusionary practices on the health and vitality of Bahrain’s political and civil spheres.

One leading member of Bahrain’s civil society told Human Rights Watch that the political isolation law is a “very obvious and clear declaration of the non-democratic country that Bahrain has turned into. It is impossible for Bahrain to be called a democracy.”

The political isolation laws have also expanded to include elections to the boards of directors of civil associations governed by the country’s associations law. This report documents three cases of civil society organizations that struggled to form a board and carry on with their activities due to the impact of these laws. When the political isolation laws came into effect, Bahrain’s Ministry of Labour and Social Development required that associations submit for approval a list of those members who were planning on running for election to the association’s board of directors. The ministry would respond, sometimes months later, with a letter confirming the names of those who had been approved to run for the board. In some cases, the letters simply omitted the names of individuals who were banned under the law; in other cases, the letter more explicitly referenced the political isolation laws.

Prominent civil society associations, including the Bahrain Human Rights Society, the Bahrain Women’s Union (a union of 13 women’s societies that advocates for women’s rights in Bahrain), and the Bahraini Society for Resisting Normalization, have struggled to continue their operations due to the political isolation laws. The delays in board formation, as a result of the political isolation laws, have devastating consequences on associations: if a new board is not elected and confirmed before the two-year term limit of the previous board expired, the labor ministry suspends access to the organization’s bank accounts and funding sources, forcing the association to stop work. Seat vacancies also allow the Ministry of Labour and Social Development to appoint new members, leading to fears that the boards may eventually be stacked with government loyalists and “become pro-government more and more,” according to an activist.

A member of a civil society organization told Human Rights Watch that “it was very hard to convince 11 [people] to be on the board. Most of the people in the society are members of the political parties that were banned.” A member of another civil society group echoed these concerns: “when we speak about the society, we are speaking about more than 80 percent of the members cannot be a candidate because they were either in Wa’ad, al-Wifaq, or another organization dissolved by the court.”

Bahraini activists fear that the law will ultimately result in civil society organizations failing to genuinely represent the popular will of its association members and to achieve critical impact on human rights because they cannot be seen to be too critical of the authorities. One Bahraini civil society organization representative said that the appointed board members have altered the tenor of their organization, and new members “have made the statements [released from the society] less strong. They want to keep us as just a voice, but only to a certain amount.”

Meanwhile, detentions and summons of Bahraini citizens for speech-related offenses continue. One Bahraini freedom of speech expert told Human Rights Watch that “there were so many cases of harsh sentences, which indicated that there was an intention to shut up the people, a need to make them afraid.”

A former Bahraini journalist told Human Rights Watch that because of the “continuous arrests since 2011 until 2017, fear became part of what people experience on a daily basis. It became normal for people to censor themselves and silence themselves before they react.”

The Bahraini government should repeal the 2018 political isolation laws, end the deplorable Ministry of Interior practice of denying certificates of good behavior to punish perceived opponents, and restore full legal political and civil rights to all Bahraini citizens. It should restore the previously dissolved political societies, lift all restrictions imposed on opposition figures regarding candidacy in the parliamentary and municipal elections, end the restrictive measures that are harming the basic functioning of civil associations, and release all people jailed solely for their peaceful political activities. Bahrain’s allies, including the US, the UK and other European states, should also pressure authorities to cease its repression of peaceful opposition and civil society and reject the results of what will be unfree and unfair parliamentary elections in November if they do not. Bahrain’s regional allies, Saudi Arabia in particular, should also end their support of the country’s repressive practices.

Recommendations

To the Government of Bahrain

- Repeal Law 25/2018, known as the political isolation law, and restore full political rights to all opposition members.

- Repeal Law 36/2018, known as the civil isolation law, and restore full civil rights to all opposition members.

- Repeal or reform Bahrain Law 58/2006, Protecting Society from Terrorism Acts, to ensure it excludes peaceful protest and other activities.

- Restore previously dissolved political societies: al-Wifaq, the National Democratic Action Society (Wa’ad), and Amal.

- Lift all restrictions imposed on the political opposition regarding candidacy in the parliamentary and municipal elections.

- Withdraw the letter from of the Ministry of Labour and Social Development to civil society organizations issued on January 15, 2020, stating that all candidates for their boards of directors will be subject to security checks.

- Erase all convictions based on the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression and association, and all convictions based on confessions where there is any suggestion of abuse.

- Release all opposition activists, journalists, and other individuals, including Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, a founder of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, Hassan Mushaima, and Abduljalil al-Singace, convicted solely for exercising their right to free speech, peaceful assembly, or association.

- Revoke Bahrain penal code articles that continue to be used to prosecute individuals for the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression, association, or peaceful assembly, or amend such articles so that they comply with international law.

- Accept the requested visits of the special rapporteurs on freedom of expression and freedom of assembly.

To the Ministry of Labour and Social Development

- Allow all Bahrainis to serve on the boards of directors of associations, regardless of their political opinions.

- Reinstate previously-nominated board members who were rejected because of the political isolation law.

To the Ministry of Justice

- Remove any discriminatory restrictions on candidates to run in the 2022 parliamentary elections, including those based on prior political affiliation.

- Release accurate data on the number of Bahrainis impacted by the political isolation laws.

To the Ministry of Interior

- End the harassment of opposition figures and human rights defenders by repeated summons and interrogations.

- End the practice of denying certificates of good behavior on the basis of political opinion and ensure that all individuals are informed of the legal basis for being denied such certificates and provided a transparent process for individuals to appeal any such denial.

To The Government of the United States

- Publicly and privately raise concerns over the issues identified in this report and urge the Bahraini authorities to implement the recommendations listed above, including in local statements and demarches, statements at the UN Human Rights Council, statements at the headquarters level, as well as during summits and other interactions with Bahraini authorities.

- Restrict arms sales and security cooperation until Bahrain enacts and complies with the recommendations in this report.

To the Government of the United Kingdom

- Publicly and privately raise concerns over the issues identified in this report and urge the Bahraini authorities to implement the recommendations listed above, including in local statements and demarches, statements at the UN Human Rights Council, statements at the headquarters level, as well as during summits and other interactions with Bahraini authorities.

- Immediately suspend funding, support, technical assistance and training to Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior, security services, criminal justice system, and the judiciary until Bahrain fully complies with its international human rights obligations.

To the European Union (EU) and its Member States

- Publicly and privately raise concerns over the issues identified in this report and urge the Bahraini authorities to implement the recommendations listed above, including in local statements and demarches, statements at the UN Human Rights Council, statements at the headquarters level, as well as during summits and other interactions with Bahraini authorities.

- Link enhanced bilateral cooperation and closer trade and political relations to clear human rights benchmarks, including promoting freedom of expression and association, and releasing human rights defenders and perceived critics detained solely on politically-motivated grounds.

- Ensure thorough implementation of all relevant EU human rights guidelines, notably those on human rights defenders, on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and on freedom of expression online and offline, as well as of the EU action plan on human rights and democracy 2020-2024.

- Identify key, concrete deliverables for the yearly EU-Bahrain human rights dialogue, including ending the abusive practices described in this report and releasing all political prisoners, and consider the suspension of the dialogue should the Bahraini authorities refuse to commit to concrete, positive improvements in that regard.

Methodology

Bahraini authorities have not granted Human Rights Watch access to freely conduct in-country research since 2013. The Bahraini government since then has rejected or ignored requests for visas to visit the country for purposes of monitoring trials, investigating human rights violations, or meeting with government officials.

The report is based on 30 remote interviews with Bahraini activists and opposition members conducted by Human Rights Watch between May and June 2022, review of government statements and documents, laws, and court records, and review of Bahraini local media outlets and social media. To protect those interviewed from retaliation, Human Rights Watch has withheld names unless they indicated a willingness to be named. Researchers informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview and the ways in which the data would be used, and none of the interviewees received financial or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch also wrote to Bahraini authorities on September 8, 2022, with questions regarding its political isolation laws and other related laws regulating freedom of expression and assembly. At time of publishing, Bahraini authorities had not responded to our inquiries.

I. Background

Bahrain’s 2018 political isolation laws banning all members of previously dissolved political societies from running in the country’s elections and participating fully in civil, social, and cultural organizations are the latest salvo in the country’s decade-long crackdown on human rights.

The 2018 parliamentary and municipal elections were marred by a repressive political environment that included violations of freedom of expression and arbitrary arrests.[1] Authorities arrested Ali Rashed Al Asheeri, a former member of parliament, on November 13 ,2018, after he tweeted about boycotting the elections due to the political isolation law.

Bahraini authorities have steadily outlawed and dissolved prominent opposition groups throughout the past decade. On May 31, 2017, at the request of the Ministry of Justice, a Bahraini court dissolved the National Democratic Action Society (Wa’ad), one of Bahrain’s last remaining political societies, and seized its funds.[2] The High Court of Appeals confirmed the decision on October 26, 2017.[3]

Prior to Wa’ad’s dissolution, the Ministry of Justice launched a campaign in March 2017 against the group, accusing it of “incitement of acts of terrorism and promoting violent and forceful overthrow of the political regime,” after Wa’ad issued a statement describing a “constitutional political crisis” in Bahrain.[4]

Authorities’ closure of Wa’ad came on the heels of the dissolution of al-Wifaq, the country’s main political opposition party, in June 2016.[5] Bahrain’s Ministry of Justice submitted a request to the judiciary on June 14, 2016, to dissolve al-Wifaq, and the court issued an “expedited” ruling to dissolve the party and liquidate its funds. Bahraini authorities accused the group, without evidence, of providing “a nourishing environment for terrorism, extremism and violence.” In July 2012, a Bahraini court dissolved the Islamic Action party, Amal.[6]

Bahraini authorities used lethal force to suppress the country’s 2011 peaceful anti-government and pro-democracy uprising and protests. Since this time, authorities consistently arrest, prosecute, and harass human rights defenders, journalists, opposition leaders, and defense lawyers for speech related concerns, including for their social media activity.[7] Bahrani citizens are arbitrarily detained for participating in protests and activists and human rights defenders are denied fair trials. [8]

All independent Bahraini media have been banned since June 2017, when the Information Affairs Ministry suspended Al Wasat, the country’s only independent newspaper.[9]

In addition to the crackdown on independent media, amendments made to the press law in April 2021 significantly expanded government restrictions in the digital space.[10] The amendments ban electronic media from publishing content that is “inconsistent” with the “national interest” or the constitution, and news and broadcasting sites are required to register with the Ministry of Information Affairs.[11]

Thirteen prominent dissidents have been serving lengthy prison terms since their arrest in 2011 for their roles in pro-democracy demonstrations.[12] They include Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, a founder of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, as well as Hassan Mushaima and Abduljalil al-Singace, leaders of the opposition group al-Haq. All three are serving life terms.[13]

II. Bahrain’s Repressive Legal Framework

Hollow Constitutional Protections

Bahrain’s 2002 Constitution provides protections for fundamental rights and freedoms, including basic political rights, as well as freedoms of association and expression.[14]

Article 1 states that the system of government in Bahrain is democratic and that “sovereignty is in the hands of the people.”[15] This first article also grants citizens of Bahrain the right to participate in public affairs, and guarantees basic political rights, including “the right to vote and to stand for elections.”[16]

Article 4 states that “freedom, equality, security, trust, knowledge, social solidarity and equality of opportunity for citizens are pillars of society guaranteed by the state.”[17]

Article 27 guarantees the freedom to form associations “for lawful objections and by peaceful means,” but requires that “the fundamentals of religion and public order are not infringed.”[18]

Freedom of expression is also guaranteed by the constitution in article 23, “provided that the fundamental beliefs of Islamic doctrine are not infringed, the unity of the people is not prejudiced, and discord or sectarianism is not aroused.”[19]

Bahrain is a party to a number of international human rights treaties.[20] In 1998, Bahrain ratified the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; in 2006, Bahrain ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; and finally, in 2007, Bahrain ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Bahrain is also a signatory to the Arab Charter on Human Rights which, in article 24, guarantees that every citizen has the right “to freely pursue a political activity,” “to stand for election or choose his representatives in free and impartial elections, in conditions of equality among all citizens that guarantee the free expression of his will,” and “to freely form and join associations with others.”[21]

Despite these broad guarantees, rights are loosely worded and weakened by qualifying statements, resulting in arbitrary interpretation and a broad failure to uphold them by Bahrain’s judiciary. The judiciary is not fully independent from Bahrain’s monarchy, as judges are appointed by the king, and many are members of the ruling Al Khalifa family.[22] The king also heads the Supreme Judicial Council.

Bahrain’s courts fail to consistently and meaningfully uphold freedom of expression, association, and political rights. In practice, there is a lack of implementation of constitutional guarantees regarding these rights, in addition to a comprehensive legal regime that actively undermines them.

Political Isolation Laws

Bahrain’s political isolation laws, passed in June and August 2018, are the continuation of a years-long effort by the Bahraini government to disenfranchise, ban, and criminalize political opposition. The legislation explicitly bars opposition members from fully participating in political and civil life in Bahrain, and these blanket bans impact individuals with any prior ties – real or perceived – to dissolved political parties, including al-Wifaq, Wa’ad, and Amal. [23]

In June 2018, authorities issued Law 25/2018 (referred to as the political isolation law) amending article 3 of Law 14/2002, Bahrain’s political rights law, explicitly barring individuals from running for election in Bahrain’s House of Representatives if they have been: [24]

- Convicted of a serious crime, even if a special pardon is issued for the penalty or he has been rehabilitated.

- Sentenced to imprisonment for premeditated crimes for a period of more than six months, even if a special amnesty is issued for them.

- Leaders and members of political societies dissolved by a final judgment for violating provisions of the kingdom’s constitution or any of its laws.

- Someone who willfully harms or disrupts the functioning of constitutional or parliamentary life by leaving parliamentary work, or whose membership has been revoked for the same reasons.[25]

Law 25/2018 severely restricts the political rights of any individual who falls under these categories and excludes thousands of Bahrainis from full participation in the political life of the country. In addition to the blatant exclusion of all members of previously dissolved political parties from Bahrain’s political process, the law also includes former prisoners, including those individuals convicted of speech, assembly, and association-related crimes.

In February 2011, eighteen elected members of Bahrain’s parliament and members of the al-Wifaq party submitted their resignation to protest the authorities’ violent crackdown on protestors. [26] Some Bahraini lawyers and civil society members have interpreted the last clause of Law 25/2018 to further target these former lawmakers and other individuals who resigned or boycotted their posts on principle.[27]

The Bahraini government quickly expanded the political isolation law by amending Law 21/1989 which governs associations, including human rights organizations, charity funds, sports clubs, and other social clubs to establish new requirements for candidates to the board of directors of associations and clubs.[28] In August 2018, authorities issued Law 36/2018 (referred to as the civil isolation law) amending article 43 of Law 21/1989 to require that “a member of the board of directors must enjoy full civil and political rights,” thus extending the conditions outlined in Law 25/2018 to anyone wishing to become a member of the board of directors of an association.[29] This means that anyone who is deprived of their civil and political rights, which would be the case for those who are punished under Law 25/2018, will also be barred from becoming a member of the board of directors of an association.

On January 15, 2020, the Ministry of Labour and Social Development issued a letter directly to civil society organizations stating that all candidates for their boards of directors will be subject to security checks.[30]

Bahraini civil society groups have requested the full list of names of those who fall under the political isolation law from the Ministry of Justice but have been unable to obtain any information.[31] The Ministry of Justice has not released any data on the number of Bahrainis covered by the ban.

In lieu of official data, Bahraini groups have compiled previous membership lists from dissolved political parties to estimate the number of Bahrainis impacted by the law. Estimates range from between 6,000 to 11,000 individuals who have been stripped of their full political and civil rights.

There is no expiration date on the political or civil bans outlined in the political isolation laws. Bahraini human rights groups believe the ban establishes a life sentence of disenfranchisement and political marginalization and there are no avenues set out by the laws to contest or remedy the abuse.

The political isolation laws are also retroactive. Bahrainis who became members of these opposition groups before the government severely tightened restrictions on political rights are being penalized for prior acts that were legal at that time.

Prior to the 2018 political isolation laws, civil society organizations already faced wide ranging restrictions on their activities. Law 21/1989, the law governing associations, prohibits civil society organizations from “engaging in politics” without providing a clear definition of “politics” and requires all civil society organizations to register with the Ministry of Labour and Social Development.[32]

Article 50 grants the Ministry of Labour and Social Development the power to dissolve a civil society organization if it deems that the organization is “unable to achieve the objectives it was established to undertake or if it violates the Law of Associations, public order or norms.”

Laws Violating Freedom of Expression

An oppressive legal regime in Bahrain criminalizing freedom of expression is used to silence government critics and punish opponents, including the penal code, the counterterrorism law, the press and publication law, and the cybercrime law.

The penal code includes several speech-related offenses.[33] Article 290 criminalizes the “deliberate misuse of telecommunication mediums” and outlines a punishment period not exceeding 6 months imprisonment or a 50 dinar (US $132) fine.[34] Article 134 criminalizes publishing “false or malicious news, statements or rumors about domestic conditions in the State” that are “harmful to the national interests.”[35]

Article 215 criminalizes “offending a foreign country” and includes a punishment of imprisonment no more than two years or a fine of no more than 200 dinars.[36] Article 216 criminalizes offending Bahrain’s “National Assembly, or other constitutional institutions, the army, law courts, authorities or government agencies” with a punishment “liable for imprisonment or payment of a fine.”[37]

In addition to the penal code, Bahrain’s Protecting Society from Terrorism Acts, enacted in 2006 and expanded in 2013, criminalizes freedom of speech and assembly using vague and overbroad definitions of terrorism and sets steep penalties for violations.[38]

Law 47/2002 (the Law on Press, Publication, and Broadcasting) criminalizes criticism of Bahrain’s allies. In April 2021, the law was amended to expand restrictions on digital expression.[39] Article 13 prohibits newspapers and electronic media sites from publishing content that contradicts the provisions of the constitution or conflicts with the national interest. Article 44 requires news websites to apply to register with the Ministry of Information Affairs in order to operate.

In May 2019, Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior warned in a tweet that “those who follow inciting accounts that promote sedition and circulate their posts will be held legally accountable.”[40]

III. Violations and Bias in Enforcement

The 2018 political isolation laws are part of the Bahraini government’s broader effort to isolate, disenfranchise, and punish political opposition and critical voices. Laws violating freedom of speech and association bolster other exclusionary state practices penalizing government critics.

The Bahraini government has added a punitive socioeconomic dimension to its repression.[41] In addition to arresting and summoning for interrogation individuals exercising their right to freedom of expression and using political isolation laws to limit political and civil rights, the authorities also punish political opposition members and dissidents economically and socially through the denial and delay of documents necessary to obtain employment, apply for universities, and gain entry into social and sports clubs.

Political Disenfranchisement and Bans on Running for Office

The 2018 political Isolation law enacts serious legal barriers to the full and complete participation of all Bahrainis in the political process by banning members of dissolved political groups from running for election to Bahrain’s Council of Representatives. The law bans individuals who have been convicted of a serious crime, even if issued a pardon, those who have been imprisoned for more than six months, and those who disrupted the functioning of parliament by leaving or terminating.

The latter conditions greatly impact opposition figures, human rights defenders, and any participants in protest marches or assemblies, as these groups were brutally targeted by Bahraini security agencies during and in the aftermath of the 2011 uprising.[42] Protestors, human rights advocates, and opposition figures were imprisoned in large numbers by the Bahraini government on abusive charges related to freedom of expression, assembly, and association and sentenced to lengthy imprisonment sentences.[43]

Bahrain’s government first implemented the political isolation law during the country’s 2018 parliamentary elections.[44] At least twelve candidates who applied to the Ministry of Justice to run in the 2018 parliamentary elections were rejected by the ministry due to their prior affiliation with dissolved political parties, including Nader Abdel-Imam, Muhammad Hassan al-Aradi, Youssef al-Buri, Hussein al-Eskafi, Majed al-Majed, Ali Shamtout, Majed Taher, Jaafar Dheif, Hussein al-Uwainati, Ibrahim Bahr, Majid Saleh, and Hussein Muhammad Habib.[45]

Opposition figures and members of dissolved political societies publicly called for a boycott of the elections because of the political isolation laws, including former Members of Parliament Ali Rashed Al Asheeri and Ali al-Aswad, who were both members of al-Wifaq. Bahrain’s public prosecutor arrested Al Asheeri after he tweeted on November 8, 2018, that he would be boycotting the elections.[46] He wrote: “I am a Bahraini citizen deprived of my political and civil rights, so my family and I will boycott the parliamentary and municipal elections. No to the political isolation law.”

Muhanna Al Shayji, the head of Bahrain's Election Crimes Investigation Committee at that time, said in a statement released shortly after by the public prosecutor’s office that an individual had used Twitter and had been charged with “incitement not to participate in the upcoming parliamentary and municipal elections in a way that would prejudice the freedom of voting and affect and disrupt the integrity of the electoral process.”[48]

The implementation of the political isolation laws, as well as the previously forced dissolution of Bahrain’s two major opposition parties, al-Wifaq and Wa’ad, ensured that the 2018 parliamentary elections would be stacked with pro-government candidates even before the vote began.

With zero opposition participation, alongside an atmosphere of repression created by the arrests of opposition figures and a ban on international election observers, the 2018 elections were problematic.[49]

The political isolation law remains in place for the upcoming parliamentary elections, set to take place in November 2022.

Authoritarian Hardening

Prior to the passage of the political isolation laws in 2018, Human Rights Watch consistently documented human rights violations during the country’s previous parliamentary and municipal elections and found a repressive political environment that was not conducive to free and fair elections.[50]

In addition to these prior violations, the political isolation laws lift any remaining democratic veneer to the country’s municipal and parliamentary elections through a blatant ban on all opposition members codified into law.

The political isolation law is a “very obvious and clear declaration of the non-democratic country that Bahrain has turned into,” said one opposition figure. “It is impossible for Bahrain to be called a democracy” with this law in effect.

A Bahraini activist told Human Rights Watch that the November 2022 elections are “a pseudo election of an authoritarian regime trying to put legitimacy on their crackdown.” The waves of prior crackdowns have collapsed genuine political society, leaving “no real political society on the ground.”

Political Isolation Laws Harming Civil Society Organizations

In August 2018, the Bahraini government extended the sanctions of the political isolation law to include associations, societies, cultural groups, sports clubs, and any organization governed by Law 21/1989.[51] Any individuals who cannot exercise their political and civil rights – i.e. where they fall under the conditions set out by the 2018 political isolation law — also become ineligible to serve as board members of these associations.

Prior to the 2018 political isolation laws, the Ministry of Labour and Social Development required civil associations to follow a set of regulations to maintain their legal status. This included uploading basic documents to the ministry’s website, including the agenda of the association’s Annual General Meeting (AGM), the group’s financial report, a report on its activities, and sharing a proposed date for the AGM. The ministry would approve the date and the association would send a notification to its members.[52]

When the new political isolation laws began to be implemented after 2018, associations were required to submit a list of names of the members intending to run for the board of directors’ election, along with their social security numbers, to the Ministry of Labour and Social Development.[53] The Ministry of Labour and Social Development purportedly sends this list of names to the Ministry of Justice for review.[54]

Following this, the Ministry of Labour and Development sends a letter to the association, confirming the names which were approved to run for the board elections. In some cases, the letter did not state explicitly the names that were rejected, and some names were simply absent from the list; nor did the letter offer an explanation in writing as to why certain names were not approved.[55] In other cases, the letter specified the names that were rejected because of the political isolation law.[56]

Before the political isolation laws, the process of approving an association’s AGM took a matter of days; now it can take months for the ministry to approve the list of names and set the date for the AGM.

A board of directors for an association in Bahrain serves a two-year term. If a new board of directors is not elected before the previous board expires, work at the association is effectively suspended.[57] The Ministry of Labour and Social Development automatically suspends the association’s access to its own bank accounts, and new programming and fundraising drives are difficult to execute.[58]

Continued vacancies in seats on the board of directors lead to the Ministry of Labour and Social Development appointing members, creating fears that the boards may eventually be stacked with government loyalists and fail to represent the general assembly of the association.[59]

Scores of individuals previously affiliated with dissolved political groups have been barred from standing on the boards of any association governed by Law 21/1989 because of the political isolation laws. Many of those who actively participated in these associations were affiliated with the dissolved political parties and have been stripped of the right to lead associations they built for decades.

Bahrain Human Rights Society

On January 31, 2022, the Bahrain Human Rights Society (BHRS), one of Bahrain’s oldest human rights organizations, received a letter from the Ministry of Labour and Social Development confirming the list of candidates that the ministry approved to run in the society’s board of directors’ election.[60] The names of three candidates were conspicuously absent: Abdul-Jalil Yousef, the organization’s secretary-general, Issa Ebrahim, and Mohsin Matar. All three are former members of Bahrain’s now-dissolved National Democratic Action Society (Wa’ad).

While the letter did not explicitly state that those individuals had been banned under the political isolation laws, one individual with knowledge of the events told Human Rights Watch that the BHRS “understood that the ministry rejected the other nominated names.”[61] Instead of stating outright that Abdul-Jalil Yousef, Issa Ebrahim, and Mohsin Matar has been rejected on the basis of the political isolation law, the letter simply omitted their names from the list of approved candidates. Later, the Ministry of Labour and Social Development confirmed the rejection of these names informally but did not offer an official explanation for the rejection.[62]

The ministry “never gave a reason when they rejected the name. [BHRS] went to the ministry and asked for a letter with a reason, but they didn’t give this to [BHRS]. At least, the ministry should give a reason,” said the individual.[63]

After the names were rejected, the society “went into panic mode,” according to another individual.[64] “The work of our society stopped because we could not form a board for a long time,” he said.[65] The formation of the board took nearly three months, during which work inside the organization came to a standstill.

Members of the society complained that they “were searching for other members to run for a long time. Who else can we propose? Are they going to reject these names as well? We were searching for a long time to find members who were not part of al-Wifaq or Wa’ad,” said one individual with knowledge of the events.[66]

One individual told Human Rights Watch, “Bahrain is very small, if we are going to restrict former opposition members from participating, it means that NGOs are denied the experience of those members who have been working in the NGOs for a long time.”[67]

“More than 50 percent of our members are former members of [dissolved] political groups. This law limits what we can do,” the individual added.[68]

Bahrain Women’s Union

On September 2019, the Bahrain Women’s Union, a union of 13 women’s societies founded in 2001 that advocates for women’s rights in Bahrain, held its AGM, elected its board of directors and sent the names of the elected members to the Ministry of Labour and Social Development.[69] The union assumed the names were accepted but they did not receive a response from the ministry until January 2020.[70] In a letter sent to the union in January 2020, the ministry rejected Zainab al-Dorazi and Safia al-Hasn for candidacy to the board because they were members of dissolved political organizations.[71]

A female activist told Human Rights Watch that “it was a shock” and the Union “rejected the decision.”[72]

The Union attempted to reach the ministry in January 2020 but did not receive a response until March 2020. The ministry responded by saying, “this is the law and we have to implement it.”[73]

The Union continued to push back against the decision, but the ministry responded by threatening that they “will have to take further steps,” if the Union did not remove the individuals from the board.[74]

The Union conducted further outreach to get candidates for board elections, but the number of rejected candidates by the authorities increased. In October 2021, the Union sent the ministry the list of names of potential candidates for the election. The ministry took a month to respond and rejected some names on the list due to “security reasons.” The Union sent a second list of names to the ministry, but they too were also rejected. The date of the AGM needed to be rescheduled twice.[75]

It took seven months, between October 2021 and April 2022, to form the board of the Union due to a lack of viability of members. “It was very hard to convince 11 women to be on the board,” one activist told Human Rights Watch. “Most of the people in the society are members of the political parties that were banned,” she said.[76]

The activist told Human Rights Watch, “it is a headache; we are very worried. If you don’t have members to be on the board, they tie your hand, they refuse to give you money to do activities, and they also will not allow you to take money from anyone else.”[77]

With the political isolation laws, the associations will “become pro-government more and more” and it will “shift the ideas of the Bahrain Women’s Union to what the government wants and repeat its point of view, that everything is fine and there are no problems with women in the country,” one women’s rights activist told Human Rights Watch.[78]

“We are afraid that they will continue to expand the law informally so that the same people won’t be able to head projects and committees inside the society, and it will affect our work more and more,” she said.[79]

This comes on top of government funding cuts in 2016 that have left some women’s organizations unable to continue their work impacting women survivors of violence. The Middle East Eye reported a source that believed the funding cuts were linked to the Bahrain Women’s Union’s critical report on women’s rights submitted to the UN in 2014 and the fact that many of the organization's members took part in the 2011 protests.[80]

Bahraini Society for Resisting Normalization

In February 2021, the Bahraini Society for Resisting Normalization, a Bahraini society opposing the normalization of relations with Israel, sent the letter with the list of board nominees to the Ministry of Labour and Social Development before the society’s AGM.[81] In March 2021, the organization received a response from the ministry confirming the names of those accepted to the board. Four names – Rasul Ashor, Amar Seadi, Ghassan Sarhan, and Khalid Hayder – were missing from the list and all were former members of dissolved political societies. [82]

The ministry did not specify the reason for the non-inclusion of those four names, but informal conversations with the ministry confirmed that it was due to the political isolation laws.[83]

According to a member of the society, “the impact was immediate on the activities of the society, and we couldn’t do forward working or organizing activities.”[84]

“When we speak about the anti-normalization society, we are speaking about more than 80 percent of the members who cannot be a candidate because they were either in Wa’ad, al-Wifaq, or another organization dissolved by the court,” the member told Human Rights Watch.[85]

Because of this issue, the board of the society could not be formed, and the ministry appointed some independent members.[86]

The new independent board members “have made the statements [released from the society] less strong. They want to keep us as just a voice, but only to a certain amount,” according to a member.[87]

Civil Society Decline

Bahrain’s political isolation laws pose an existential threat to the health and viability of Bahrain’s civil society, pressures that will only increase going forward. This impacts the progress that Bahrain can make on human rights as the government has little oversight, monitoring, or accountability for its actions.

Many individuals currently active in associations are now facing sanction by the political isolation laws for being former members of dissolved political parties. Since the implementation of the law, societies have found it difficult to convince the minority of members who are eligible for board seats to fill them because they fear potential repercussions on their work and family life.

The 2018 law has politicized board elections. Members without prior political affiliation see greater risk to their participation. New board members also have limited experience, and it will take time for them to develop their skills.

Open seats take months to fill, and the Ministry of Labour and Social Development eventually appoints individuals to vacant seats. Members of Bahrain’s civil society fear that over the long term, the ministry’s appointment of members will lead to a fundamental reorientation of civil society, with associations failing to represent the general assembly and instead representing government interests.

Economic Exclusion and the Denial of Certificates of “Good Behavior”

Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior often denies members of former political opposition parties, political activists, opposition figures, human rights defenders, and former political prisoners the issuance of “Good Conduct Certificates,” which are necessary to fully exercise one’s economic, social, cultural rights.[88]

The ministry-issued “Good Conduct Certificate” is an essential and necessary prerequisite for obtaining employment in the public or private sector, starting a business, applying to university, and obtaining memberships in social and cultural clubs. It is needed to apply for many government and private sector positions; many large corporations and listed companies require the certificate, and an employer can ask for it at any time.

One former political opposition member told Human Rights Watch, “a friend wanted me to be the head of the school, but the ministry refused the certificate so I could not work. The owner of the school was told by the ministry that they couldn’t accept me because I was a member of a political society.”[89]

There are no laws governing the issuing of a “Good Conduct Certificate.” An individual must apply through the General Directorate of Crime Detection and Forensic Evidence within the Ministry of Interior and go through a review process by security authorities.[90]

Before 2011, there were very few issues with obtaining this certificate. A civil society member told Human Rights Watch that before 2011 “it was easy to obtain, you apply through the ministry and in a few days, it would arrive. But after 2011, everything changed.”[91] The denial of the certificate became another tool used by government agencies to punish and silence former opposition members, government critics, and former political prisoners.

The Ministry of Interior does not provide an explanation if a certificate is rejected. “If it is rejected, you just have to apply again and again, and you have no idea,” said one member of a Bahraini NGO.[92]

A formerly imprisoned political prisoner requested the certificate in May 2020, but he did not receive it until November 2020, and only after an officer from the ministry mediated his case. There was no explanation for the months-long delay. “I could not benefit from the certificate by the time they issued it to me,” he told Human Rights Watch.[93]

According to the former prisoner, “I believe they act in revenge. They do this to punish political opponents.”[94]

“It has affected my life, I am unemployed. I cannot apply for work in the government or private sector.” The government “suspends the certificate in order to keep opponents’ lives suspended, even after they have been released from prison,” he said.[95]

According to the civil society member, “now, if a student was called for interrogation, even for a short time, his name will be in the system, and he will face many obstacles when he goes to get this certificate. For some, it will take months, and some will not be given.”[96]

“It’s an open tool that can be used by whoever to repress people,” said the member. “It is part of broader political isolation and exclusion and it’s not a must that you be an opposition [member], it’s enough that they think you are an opposition [member].”[97]

Social and Economic Marginalization

These repressive elements socially, politically, and economically marginalize members of previously dissolved political societies, opposition figures, government critics, and former political prisoners.

One Bahraini leading human rights defender described the political isolation laws and denial of good conduct certificates as a “dedicated disenfranchisement effort” targeting political opposition.[98]

Arbitrary Arrests, Frequent Summons, and Abusive Interrogation Practices

Bahrain’s security agencies arbitrarily detain government critics, opposition figures, and human rights defenders for speech-related offenses to punish and silence them. Harsh sentences for speech-related offenses developed as an important technique of government repression, particularly after the 2011 uprising.

The use of long sentences to punish critics for speech-related offenses reached its height in 2015. Between 2011 and 2015, security authorities created severe conditions for those even mildly critical of the authorities. Bahrainis who wrote only a few sentences on social media could face up to five years in prison. “There were so many cases of harsh sentences, which indicated that there was an intention to shut up the people, a need to make them afraid,” one Bahraini freedom of speech expert told Human Rights Watch.[99]

During this period, it was mostly abusive speech-related articles in the penal code that were used to sentence Bahrainis to years-long stints in prison. According to the freedom of speech expert, the Bahraini government leaned on the penal code because “it has so many clauses and they pick and choose what is suitable. They can choose to go for the minimum sentences or the harshest, whatever suits them.”[100]

After a string of harsh sentences for speech-related offenses, criticism of the king, ministers, and the government became muted. Long sentences created a tense environment of self-censorship and led to a shift in the repressive tactics used by the state.[101] Bahraini security authorities developed a new technique of government repression: by repeatedly summoning individuals on the basis of speech acts as a means of judicial harassment.

After 2015, courts continued to hand down a few long sentences for violations related to freedom of expression, but these decreased in number “because people learned that certain topics were risky and should be avoided,” a Bahraini expert on freedom of speech told Human Rights Watch.[102]

Instead of relying on courts handing down tough sentences, security agencies became more likely to summon individuals for interrogation and hold them for a few days to a week in prison to intimidate and thwart future criticism.

A Bahraini expert on freedom of speech told Human Rights Watch that security agencies started to “use online posts as a tool, when it became difficult to arrest someone for their human rights activity” because there were less protests and marches happening on the ground.[103] It became “much easier to take their online posts and make a case using this information.”[104]

“Self-censorship is growing and growing,” the expert said. “Fewer people are arrested, but they are trained now not to talk, to avoid everything that is critical. The reduction in the number of cases doesn’t indicate improvement but instead indicates growing self-censorship.”[105]

Nabeel Rajab

Bahraini authorities arrested prominent human rights activist and former head of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR) Nabeel Rajab on April 2, 2015, over tweets he posted about alleged torture in Jau prison.[106] The Interior Ministry announced on Twitter on April 2, 2015, that Rajab had been arrested for “publishing information that would harm the civil peace and insulting a statutory body” and released him three months later on July 13, 2015, on humanitarian grounds.[107]

Security authorities rearrested him nearly a year later on June 13, 2015, due to comments he made in television interviews where he criticized the government’s refusal to allow independent journalists and rights groups into the country.[108] A Bahraini court sentenced Rajab to two years in prison for these comments, on charges of “spreading false news and rumors about the internal situation in the Kingdom, which undermines the state prestige and status.”[109]

On February 21, 2018, the Bahrain High Criminal Court sentenced Rajab in another case to five years in prison based on tweets about alleged torture in Jau Prison and Saudi-led military operations in Yemen.[110] The court convicted Rajab based on article 133 of the penal code for “disseminating false rumors in time of war;” article 215 on “offending a foreign country” – in this case, Saudi Arabia; and article 216 for “insulting a statutory body.”[111]

Rajab appears to have been subjected to treatment that may amount to arbitrary punishment and ill-treatment. He was held in solitary confinement for more than two weeks following his arrest in June 2016.[112] His family said that for a period during his detention, prison authorities confined Rajab to a dirty and insect-infested cell at Jau Prison for 23 hours a day.[113]

Authorities released Rajab on June 9, 2020, on the basis of a 2017 law that allows courts to impose “alternative” sentences after a detainee serves half of their sentence, which Rajab completed on November 1, 2019.[114]

Najah Yusuf

A Bahraini court sentenced activist Najah Yusuf to three years in prison in June 2018 for “toppling and reformation of the political and social system” and “propagating terror crimes” by means of “propaganda recordings.”[115] The charges related to her social media posts criticizing Formula One and its role in the Bahraini government’s efforts to use the race to “sports-wash” its repressive legacy.[116] During her trial, the prosecution presented Yusuf’s Twitter and Facebook posts that encourage people to participate in a “Stop Formula of Dictatorship” rally and a “Freedom for the Formula 1 Detainees” rally.[117]

Bahraini authorities arrested Yusuf in late April 2017. She reported that during five days of interrogation officers sexually assaulted and beat her and forced her to sign a confession that they would not allow her to read.[118]

Bahraini authorities pardoned Yusuf on the occasion of Eid al-Adha and released her from Isa Town Prison on August 10, 2019.[119]

Ali Muhanna

Bahraini authorities have repeatedly summoned Ali Muhanna, an activist and the father of imprisoned activist Hussein Ali Muhanna, due to his posts and writings on social media and elsewhere demanding the release of his son and other political prisoners in Bahrain.[120]

On March 28, 2021, security authorities summoned him for questioning again where he was accused of “calling for prayers” at the al-Alawiyat Mosque.[121]

On May 14, 2021, the Cybercrime Unit of the Criminal Investigation Department summoned Muhanna for interrogation in relation to tweets that demanded the release of his son and other political prisoners and relayed Muhanna’s intention to go to Jau prison to demand their release.[122] Authorities questions him about the tweets and forced him to delete the posts.[123]

Authorities summoned Muhanna yet again on June 12, 2021, for questioning in relation to charges of participating in a protest march that took place after the burial of the deceased political prisoner Hussein Barakat who passed away on June 8, 2021, in Jau Central Prison due to complications related to Covid-19.[124] Muhanna denied that he took part in the protest and said he was completing the burial rites for his father during the time of the alleged march.[125]

Members of the Bahraini Society for Resisting Normalization

The Ministry of Interior summoned a member of the Bahraini Society for Resisting Normalization to the Hora police station three separate times between January and February 2022.[126] The society was planning a public event advocating against the normalization of relations with Israel. During the interrogations, the member was repeatedly questioned about the event and pressured to cancel it. The event was ultimately canceled.[127]

Bahraini authorities have forced at least three planned events by the society to be canceled since 2018.[128] In each case the society advertised the event on Facebook, but the police called members in for interrogation and pressured them to cancel the event.[129]

Mohammed al-Ghasra

On February 13, 2022, Mohammed al-Ghasra, a veteran journalist working for over 30 years, published a story online via the Delmon Post news website detailing a meeting between Bahraini civil society actors, an unnamed US official, and the US ambassador at the ambassador’s residence.[130] Acting Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs Yael Lempert was visiting Bahrain at that time and is presumed to have been the unnamed US official.[131]

On February 14, 2022, Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior released a statement criticizing the meeting that took place between civil society actors and an “external party” but did not explicitly name the US ambassador or Lempert.[132]

On February 16, Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior summoned al-Ghasra for questioning and interrogated him about the report on the meeting between US officials and Bahraini civil society.[133]

Al-Ghasra told Human Rights Watch that “they questioned me with many questions that I couldn’t answer” and they held him for eight hours, during which he was interrogated at the Ministry of Interior and then transferred to the prosecutor’s office.[134]

On February 16, 2022, the Minister of Interior tweeted that the manager of the Delmon Post news website was “summoned and referred to the Public Prosecution for posting false news on the meeting between representatives of some societies and a foreign body.”[135]

“I am a professional journalist; I am not for or against anybody. It depends on the truth of what happened; I am not with or against anyone,” al-Ghasra told Human Rights Watch. Al-Ghasra also said he believed the summons and interrogation were a threat.[136]

Self-Censorship and Fear

Isolation from political, civil, and economic life, as well as the campaign of arrests and freedom of expression violations, have led to deep fear and self-censorship.

Because of the “continuous arrests since 2011 until 2017, fear became part of what people experience every day. It became normal for people to censor themselves and silence themselves before they react,” one former Bahraini journalist told Human Rights Watch.

A freedom of expression expert told Human Rights Watch, “in the past five years, the situation is getting worse and worse because people are afraid to talk, unlike before. People are sitting back so they don’t get caught, arrested, or jailed for nothing for doing nothing other than speaking.”

“The issue is now the self-censoring of activists. They are their own enemy for expression because they have seen severe violations, like not renewing business licenses, not allowing them to be part of their societies,” the head of a Bahraini human rights organization told Human Rights Watch.

Acknowledgements

Many Bahraini researchers, lawyers, activists and civil society members assisted with this report by granting interviews and providing Human Rights Watch with information. Without them, it could not have been written. They cannot be named to protect their safety, but their work and support has been invaluable.

Joey Shea, a Human Rights Watch Middle East and North Africa researcher, wrote this report. Lama Fakih, director the Middle East and North Africa division, provided valuable feedback and support throughout the research process, as well as Joe Stork, deputy director the Middle East and North Africa division.

Michael Page, deputy director of the Middle East and North Africa division, edited this report. Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor, provided legal vetting. Rothna Begum, senior researcher in the Women's Rights Division, reviewed the report for women’s rights related content. Letta Tayler, associate director in the Crisis and Conflict Division, reviewed the report for terrorism and counterterrorism-related content. Tom Porteous, deputy program director, provided final program review.

A senior coordinator in the Middle East and North Africa division and Travis Carr, Publications officer, prepared the report for publication.