Summary

“We regard Mr. Mansoor’s arrest and detention as a direct attack on the legitimate work of human rights defenders in the UAE.”

–UN Human Rights Experts on March 28, 2017 regarding Ahmed Mansoor’s arrest

“According to reports at our disposal, throughout his deprivation of liberty, Mr. Mansoor has been kept in solitary confinement, and in conditions of detention that violate basic international human rights standards and which risk taking an irrevocable toll on Mr. Mansoor’s health.”

–UN Human Rights Experts on May 07, 2019 regarding Mansoor’s detention conditions

He sleeps on the floor, denied a mattress or pillow, between the four walls of a tiny solitary cell in a desert prison in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a country which zealously strives to portray itself as tolerant and rights-respecting.

He is Ahmed Mansoor, a 51-year-old Emirati engineer, poet, and father of four. He is also the UAE’s most celebrated human rights activist. Prior to his arrest almost three years ago, Mansoor had dedicated over a decade of his life to advocating for human rights in his country and the wider Middle East and North Africa region, undeterred by multiple earlier government attempts to silence him. UAE authorities detained Mansoor and four others for six months in 2011, placed him on a travel ban since, and orchestrated several attempts over the years to hack into his devices using sophisticated spyware.

In a late-night raid minutes before midnight on March 20, 2017, UAE security forces stormed Mansoor’s home and arrested him again. For more than a year following his arrest, Mansoor’s family, friends, and colleagues did not know where authorities were detaining him. He had no access to a lawyer and was granted only two half-hour family visits, six months apart, in a location different to his place of detention. In the early days following his arrest, local UAE news sources claimed authorities had detained Mansoor on suspicion of using social media sites to publish “flawed information” and “false news” to “incite sectarian strife and hatred” and “harm the reputation of the state.”

In May 2018, the Abu Dhabi Court of Appeals sentenced Mansoor to 10 years in prison on charges stemming solely from his peaceful criticism of government policies and his modest calls for human rights reform. On December 31, 2018, the UAE’s Federal Supreme Court, the court of last resort, upheld his sentence, quashing his final chance at early release. Both trials were closed and the authorities have refused all requests to make public the charge sheet and court rulings. Since his arrest, and for almost four years now, Mansoor has been confined to an isolation cell, deprived of basic necessities and denied his rights as prisoner under international human rights law, to which the UAE purports to adhere.

The information presented in this report is the first public account of Mansoor’s trial proceedings. It is based on statements from a source with direct knowledge of Mansoor’s case and it demonstrates the gross unfairness of both Mansoor’s trial and his appeal hearing– and how little the rule of law matters in the UAE when the country’s powerful state security agency is involved.

Mansoor’s trial at the Abu Dhabi Court of Appeals, where all state security-related cases are heard, began in March 2018, just about a year after his arrest. At each of the five hearings, Mansoor stated to the court that he was being held in solitary confinement and denied other basic prisoner rights, including access to phone calls and visits with his family. At three of those hearings, the judge ruled that authorities should grant Mansoor the rights afforded to prisoners on remand, but the judge’s orders, addressed to the Federal State Security Prosecution, went unmet.

At his third hearing, the judge read out six charges against Mansoor, all entirely based on his human rights activism and advocacy. The court later convicted him of five of those charges, all based on simple acts of human rights advocacy, including tweeting about injustices, participating in international human rights conferences online, and (since deleted) email exchanges and WhatsApp conversations with representatives of human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR). The court acquitted him of the sixth charge, “cooperating with a terrorist organization.”

The court based its verdict, announced during the fifth and final hearing, on the penal code and the 2012 cybercrimes law, both of which make the peaceful expression of critical views of the authorities, senior officials, the judiciary, and even public policy a criminal offense and provide a legal basis to prosecute and jail people who argue for political reform or organize unlicensed demonstrations.

In October 2018, five months after his sentencing, Mansoor appealed his conviction at the Federal Supreme Court. There, too, he explained to the judge that despite the previous court’s orders, he was still held in solitary confinement and deprived of basic prisoner rights. This judge’s demands that the previous court’s decisions be respected also went unheeded. So did his request that the court launch an investigation into why those orders were not respected to begin with.

After his trial and appeal, Mansoor continued to suffer alone in a tiny cell, without basic necessities or adequate protection during the harsh desert winter nights. Authorities continued to deprive him of meaningful contact with others and deny him access to reading materials, a radio, and television.

In 2019, after he had exhausted all the means available to him to claim his rights as a prisoner, Mansoor embarked on two hunger strikes, six months apart. Among his demands were an end to solitary confinement and access to necessities, including blankets and personal hygiene products. During his second hunger strike, which he began in early September 2019 and lasted for 49 days, Mansoor lost 11 kilograms, raising fears for his health and prompting global calls for his immediate and unconditional release. While the hunger strikes did prompt the authorities to allow him to call his wife and mother briefly twice a month and access to sunlight and exercise three times a week, the authorities did not grant him reprieve from the indefinite and brutal solitary confinement they have subjected him to since his arrest in March 2017.

From the moment he was arrested and until the present day, one state agency has been directly and entirely responsible for everything related to Mansoor’s imprisonment: the UAE’s notorious State Security Agency.

Since 2011, when UAE authorities began a sustained assault on freedom of expression and association, Human Rights Watch and GCHR have regularly documented serious allegations of abuse at the hands of state security forces against dissidents and activists who have spoken up about human rights issues.[1] The most egregious abuses are arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances, and torture. The UAE has arrested and prosecuted hundreds of lawyers, judges, teachers, and activists since then, and shut down key civil society associations and the offices of foreign organizations, effectively crushing any space for dissent.

Despite appeals by United Nations experts, United States members of Congress and European parliamentarians, as well as numerous regional and international rights groups and well-known figures, governments and world leaders have failed to raise publicly with UAE rulers the inexcusable treatment of Mansoor and others imprisoned in the UAE in violation of their right to freedom of expression. Instead, they continue to cultivate their profitable trade relationships unencumbered by the UAE’s human rights violations both at home and abroad. The US, Britain, France and Germany, for example, continue to sell arms to the UAE despite its failure to curtail unlawful airstrikes in Yemen and Libya, halt support and weapons transfers to abusive local forces, and credibly investigate previous alleged violations in both countries.

Recommendations

To the UAE authorities

- Immediately and unconditionally release Ahmed Mansoor as well as all human rights defenders, political activists, and other dissidents imprisoned solely for exercising their basic human rights, including the rights to free speech, association, and peaceful assembly.

- Pending release, ensure Ahmed Mansoor and other human rights defenders, activists and political prisoners are treated in line with the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners; including by removing him from solitary confinement, allowing him regular family visits, and providing adequate medical care.

- Allow UN experts and international NGOs to visit Ahmed Mansoor in prison to monitor his condition, as well as others unjustly detained on speech-related charges or following unfair trials.

- Given the UAE’s inability or unwillingness to conduct a credible investigation into the prison authorities’ and state security agency’s treatment of Ahmed Mansoor, allow an independent, international body access to the country to conduct a thorough independent and impartial investigation into Ahmed Mansoor’s arrest, trial, and prison conditions.

- Prosecute and hold accountable any officials found responsible for human rights violations against Ahmed Mansoor or other violations of UAE law or regulations.

- After releasing Ahmed Mansoor, return his passport and remove any barriers to travel abroad and provide compensation for ill-treatment and other abuses committed against him.

To the Governments of the United States, Britain, France, and Germany

- Publicly and privately call on UAE authorities to immediately and unconditionally release Ahmed Mansoor and anyone else detained in the UAE for exercising basic rights.

- Contest the UAE’s attempts to whitewash its abuses by presenting itself as a tolerant, progressive, and rights-respecting country by calling on authorities to allow UN experts and independent, international monitors unfettered access to the country and its prisons and detention centers.[2]

- Given the UAE’s record of unlawful attacks in Yemen and Libya, halt proposed weapons sales to the UAE and suspend all future sales until the UAE curtails unlawful airstrikes in Yemen and Libya, halts support for and weapons transfer to abusive local forces, credibly investigates previous alleged violations in both countries; and takes concrete and measurable steps to address systematic human rights abuses in the UAE.

Methodology

This report is based on statements obtained from a source with direct knowledge of Ahmed Mansoor’s court proceedings as well as interviews with two former prisoners who, at different times during his detention in al-Sadr prison, were detained alongside Mansoor in the designated isolation ward. Human Rights Watch and the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR) are withholding the names and identities of some sources for their security.

The report is also based on past research conducted by Human Rights Watch and the Gulf Centre for Human Rights, as well as a review of past statements on Ahmed Mansoor’s case by UAE officials, UN experts, US members of Congress, and European parliamentarians.

I. Background

Ahmed Mansoor, perhaps best known as the “million-dollar dissident” and the “last human rights defender left standing in the UAE” (until his arrest), is an engineer, poet, and father of four. He graduated from the University of Colorado Boulder in the United States in 1999, then worked in Maryland until 2001 before returning to the UAE. He began his human rights activism in the UAE in 2006, and soon after, caught the attention of the country’s rulers and its people when he successfully campaigned for the release of two Emiratis jailed for comments they made online.

In 2009, Mansoor led an effort opposing a draft media law that threatened freedom of expression and launched a petition urging the UAE president (the ruler of Abu Dhabi) not to approve it. His efforts were successful, and the president suspended the draft law.[3]

Alongside other Emiratis, mostly academics, Mansoor also ran an online discussion forum, UAEHewar.net, which focused on issues of politics, society, and development in the UAE and which was frequently censored by the authorities. It provoked heated debates around topics previously viewed as red lines, including the growing personal wealth of the country’s various sheikhs, and the sustainability of the country’s investments in overseas prestige projects.[4]

Starting in 2011, the government’s responses to Mansoor’s activism grew harsher. Inspired by the Arab uprisings in neighboring countries, in March 2011 Mansoor launched a petition calling for modest democratic reforms, along with Nasser bin Ghaith, an economist and university lecturer at Sorbonne Abu Dhabi, and online activists Fahad Salim Dalk, Ahmed Abdul-Khaleq, and Hassan Ali al-Khamis. UAE authorities arrested all five men three months later. In November 2011, after six months in detention and following an unfair trial, a UAE court sentenced Mansoor to three years imprisonment and the others to two years each for “publicly insulting” UAE authorities.[5] The next day, following an international outcry by rights groups, the UAE president, Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, commuted the sentences of Mansoor and the other four men.[6] However, the authorities never returned his passport, thereby subjecting him to a de facto travel ban.

The UAE’s assault on freedom of expression intensified in the months following their release. By then, Mansoor had already won international renown as a human rights activist. A member of the advisory boards of both Human Rights Watch’s Middle East division and the Gulf Centre for Human Rights, he worked extensively with international rights organizations to raise awareness of violations in the UAE, particularly arbitrary detention, torture and ill-treatment, and unfair trials.

Over the next few years, UAE authorities launched an all-out assault on independent activists, judges, lawyers, academics, journalists, and students for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression and association.[7] They harassed, arbitrarily detained, forcibly disappeared, ill-treated, and convicted government critics following unfair trials. The UAE then introduced new laws and amended already repressive ones to further suppress freedom of expression and more easily silence dissidents.[8]

As his peers were unjustly locked away one by one, sometimes following mass sham trials, Mansoor referred to himself as the last human rights defender left standing, the only independent source of credible information on UAE rights violations.[9] In 2015, a jury of 10 global human rights organizations selected him to receive that year’s esteemed Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders, which “honors individuals and organizations who have shown exceptional commitment defending and promoting human rights, despite the risks involved.”[10]

The ever-shrinking space for public engagement and free speech in the UAE did not intimidate Mansoor, nor did the physical assaults, death threats, or government surveillance he was subjected to.[11] Despite repeated attacks, threats, and the mysterious disappearance of money from his bank account, no one was ever held accountable.[12] Even as he repeatedly found himself the hacking target of a spyware-obsessed government, he refused to be cowed, and continued to advocate on behalf of Emiratis who could no longer advocate for themselves.

In August 2016, in the most publicized government attempt to hack his iPhone cell phone and online accounts, Mansoor received a text containing a link that the sender promised would divulge information on detainee torture in UAE prisons.[13] Instead of clicking on the link, Mansoor forwarded the message to Citizen Lab researchers who determined that this was a sophisticated phishing attempt using technology from an Israeli company, the NSO Group.[14] The attack exposed vulnerabilities in Apple’s mobile operating system, spurring the company to release an update fixing that security flaw. Security experts said at the time that the tool used to target Mansoor could be worth as much as $US 1 million, leading some to refer to Mansoor with his newly-acquired notoriety as “the million-dollar dissident.”[15]

II. An Honorable Man Versus an Unjust State

Tweets by Ahmed_MansoorAt 11:55 p.m. on March 19, 2017, 10 uniformed police officers raided Mansoor’s home in Ajman emirate and took him away; they also took all the family’s mobile phones and laptops, even those belonging to Mansoor’s children, a source told Human Rights Watch and GCHR at the time.[16]

The next day, WAM, the UAE’s official news agency, stated that authorities detained Mansoor on suspicion of using social media sites to publish “flawed information” and “false news” to “incite sectarian strife and hatred” and “harm the reputation of the state.”[17]

In the weeks leading up to his arrest, Mansoor had criticized the UAE’s prosecutions of activists for speech-related offenses and called for the release of Osama al-Najjar and Dr. Nasser Bin Ghaith, whom authorities had arrested again. Mansoor had also used his Twitter account to draw attention to human rights violations across the region, including in Egypt and Yemen, and signed a joint letter with other activists in the region calling on leaders at the Arab League summit in Jordan in March 2017 to release political prisoners in their countries.

For more than a year following his arrest, Mansoor’s place of detention was unknown to his family, friends and colleagues. He had no access to a lawyer and was granted only two half-hour family visits six months apart in a location different to his place of detention.[18]

Trial

Unbeknownst to the public or his colleagues and family, his trial at the State Security Chamber of the Abu Dhabi Court of Appeals began on March 14, 2018, almost exactly a year after his arrest. His trial was closed and UAE authorities have refused requests to make public the charge sheet and court ruling. The information presented here is the first public account of his trial proceedings, based on statements from a source with direct knowledge of Mansoor’s case. It demonstrates how unfair both his trial and his appeal hearing were – and how little the rule of law matters in the UAE when the country’s powerful state security agency, which reports directly to the president, is involved.

The source stated that Mansoor’s first hearing, only five minutes long, was postponed because no lawyer was there to represent him. Mansoor nevertheless managed to divulge to the court that he was being held in solitary confinement and denied communication with the outside world, two grave violations of a detainee’s rights under international standards, to which the UAE purports to adhere.[19] According to UAE law, solitary confinement can only be imposed for up to seven days and only as a disciplinary sanction after a proper investigation is conducted.[20] The law also grants prisoners the right to receiving up to four visitors a day, three days a week, for no less than 15 minutes a visit.[21]

The source described that Mansoor’s second hearing also lasted five minutes.[22] It was only after the second hearing that GCHR learned that Mansoor had been brought to trial. While a court-appointed lawyer was present this time, the judge, an Egyptian, was not. Again, Mansoor stated to the court that he was being held in solitary confinement and not allowed to make phone calls or receive visits from family members. The court decided to grant him the rights of a prisoner on remand, the source said, which according to UAE law, includes one additional visit a week, and the right to correspond with whomever they wished to correspond with under supervision of prison officials, and to meet with their lawyers in private in the prison. However, the deprivation of Mansoor’s rights continued despite the court order.

Prosecutors announced the charges against Mansoor during his third hearing, on April 25, 2018. The six charges against him, as well as the basis for them, are as follows:

- Cooperated with a terrorist organization that aims to disrupt the state's security and interests, while being aware of its objectives.

Basis: Mansoor’s participation in an online campaign led by a Geneva-based international organization around arbitrary arrests in Saudi Arabia, as well as an email thread between Mansoor and the same organization around the cases of certain UAE political detainees. Mansoor was later acquitted of this charge.

- Established and managed his accounts on social media and his e-mail and published incorrect information on them by claiming - contrary to the truth - that the UAE was oppressive and abusive against its people, and violated their rights, which could have incited sedition, hatred and disturbance of public order.

Basis: Tweeting or retweeting information about human rights issues, including arbitrary arrests, secret prisons, ill-treatment and torture and other violations in prisons, as well as travel bans, citizenship revocations, the shrinking space for free expression in the UAE, and the overbroad, repressive laws used to silence activists.

- Provided incorrect information to organizations mentioned in the investigations that harm the reputation, prestige, and status of the state.

Basis: Mansoor’s participation via Skype in multiple public conferences in Switzerland and the United Kingdom related to laws and freedoms in the UAE, the situation for human rights defenders and activists in the country and nationality laws, as well as his speech when he received the Martin Ennals Award in 2015. The charge was also based on deleted email exchanges going back to 2011 as well as WhatsApp messages between Mansoor and representatives of international human rights organizations including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the Gulf Centre for Human Rights.

- Deliberately spread false and malicious statements and rumors that disturb public security and harm the public interest.

Basis: Same as second charge.

- Violated, by public means and through use of his aforementioned accounts and using information technology, the status of the judges of the Federal Supreme Court by claiming that their judgments are unfair on the occasion of one of the cases heard before the court.

Basis: No clear basis given, but Mansoor did update international human rights organizations by email about the judicial proceedings of certain political detainees, including when Dr. Nasser bin Ghaith first appeared in court after eight months in incommunicado detention. The email mentioned that state security officials had interfered with the judgement of the Federal Supreme Court, basing the allegation on the 2015 report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges on the UAE.

- Published, dishonestly and in bad faith, through public means and using his aforementioned accounts, what took place during open court sessions.

Basis: Same as fifth charge.

The source said that following the announcement of charges, Mansoor for a third time demanded that security authorities remove him from solitary confinement and allow him phone calls and visitation rights. He also asked that that the court provide copies of his court file and the laws relevant to his case. The judge said that Mansoor’s lawyer could follow up with the prosecution and that Mansoor would be allowed to make a phone call, but his demands remained unmet.

By the fourth hearing, on May 9, 2018, authorities had still declined to provide Mansoor a copy of the court documents, and Mansoor told the judge as much, the source said. Mansoor also yet again told the court that his jailers had not implemented its decision to grant him his legal rights as a prisoner. At the end of the session, without Mansoor present, the judge ruled that he should be given a copy of or access to the court file and that he had 10 days to submit a memorandum of defense to be considered in determining a verdict. In violation of the judge’s decision, prosecutors only allowed Mansoor to view the reportedly large court file once, while in their office, and gave him just three days to submit his defense memo.

At his final hearing on May 29, 2018 the court found him guilty of five of the six speech-related charges and acquitted him of the first charge of cooperating with a terrorist organization. The court sentenced him to ten years in prison and a fine of 1 million Emirati dirhams (approximately US $270,000). It also ruled that he be placed under surveillance for three years following completion of his prison sentence, that all his devices be confiscated, and that his social media accounts be shut down. The court based its verdict on articles of the UAE’s penal code and the 2012 cybercrimes law.[23] The UAE penal code makes the peaceful expression of critical views of the authorities, the judiciary, and even public policy a criminal offense, subject to a prison sentence, in contravention of international human rights guarantees for free speech. The cybercrimes law’s vaguely worded provisions provide a legal basis to prosecute and jail people who use information technology to, among other things, criticize senior officials, argue for political reform, or organize unlicensed demonstrations.

Appeal

On October 29, 2018, five months after his unjust conviction on speech-related charges based entirely on his human rights activism, Mansoor found himself again in front of a judge, this time at the Federal Supreme Court’s State Security Circuit, the country’s court of last resort in state security cases. Again, the court proceedings were closed to the public.

The source stated that at his earliest opportunity during the first appeal hearing, Mansoor told the judge of the horrible conditions of his solitary detention, that authorities continued to deprive him of his basic rights as a prisoner, and that security authorities simply ignored the previous court’s decisions that he be granted those rights. The judge, this time an Emirati, ordered the prosecution to implement the previous court decisions and to inform the court why authorities had not complied with those decisions. But, according to the source, this judge’s orders, too, were ignored, demonstrating just how little authority the highest federal court in the UAE has over the country’s state security agency.

At his second appeal hearing, on November 12, 2018, when Mansoor pointed out to the judge that security authorities simply ignored his direct orders, the judge avoided a clear response, saying merely that the prosecution is responsible for investigating Mansoor’s conditions of detention.

Mansoor’s case is consistent with previous international investigations into the independence of the UAE judiciary. In a May 2015 report following an official visit to the UAE, the UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers expressed particular concern around “allegations of pressure exerted by members of the executive, prosecutors and other State agents, in particular members of the State security apparatus [on the work of judges].”[24] The Special Rapporteur also clearly stated that “the judicial system remains under the de facto control of the executive branch of government.” This was the last time a UN special rapporteur was permitted to conduct an official visit to the UAE.

Mansoor’s third and fourth appeal hearings were postponed without informing him. The third hearing was held on December 10, 2018 and the fourth on New Year’s Eve 2018. At a moment when it would attract minimal media scrutiny, the court upheld Mansoor’s unjust sentence, crushing his final chance at early release.

Artur Ligeska, a former prisoner from Poland, spent eight months spanning 2018 and 2019 in al-Sadr prison, including five months in cell 32, two cells down from Mansoor. “I remember the day when he lost the appeal,” Ligeska told Human Rights Watch in September 2019. “He came [back] to the isolation ward and he start[ed] to shout.”

III. Singled Out for Persecution

The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (also known as the Nelson Mandela Rules) are often regarded by states as the primary – if not the only – source of standards relating to treatment in detention, and are the key framework used by monitoring and inspection mechanisms in assessing the treatment of prisoners.[25] They are comprised of 122 rules covering all aspects of prison management and treatment of prisoners, including accommodation, personal hygiene, clothing and bedding, exercise and sport, healthcare, the prohibition of torture and limits on solitary confinement, and contact with the outside world. In each of the aforementioned aspects of his detention, Mansoor’s treatment remarkably fails to meet the minimum acceptable standards.

Solitary Confinement

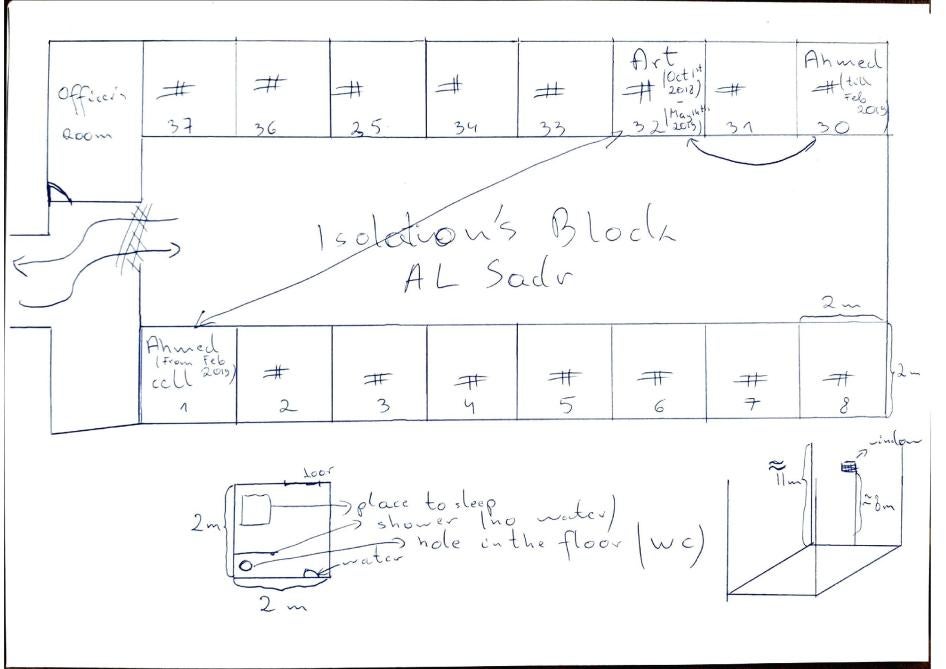

Ever since his arrest, and approaching four years now, Mansoor has been held in a solitary confinement cell at al-Sadr prison barely the size of a 2 x 2 meter parking spot, the source stated. To ensure Mansoor is deprived of any meaningful engagement with other prisoners, the prison administration empties out the prison clinic, canteen, and outdoor exercise space on the very infrequent occasions security officials allow him to access them.

Mansoor’s first two years in detention were especially harsh. In al-Sadr, the isolation cells are in a sectioned-off part of the prison in two long rows, with the cells farthest from the entrance – about 50 meters away – being the most remote. One of the two most remote cells – cell 30 – was where Mansoor was confined during those first years, with other solitary prisoners occupying cells closest to the entrance. Artur Ligeska, a former prisoner who provided information to the Gulf Centre for Human Rights and Human Rights Watch, said he was able to converse with Mansoor when he was two cells away. However, he said the cells had previously been left empty for a long time, so that, even if Mansoor cried out loudly, it was unlikely he would be heard, let alone be able to converse. Every isolation cell has a tiny 20 x 50 centimeter window facing the corridor and the cell across from it in the isolation ward. Later, after he was moved to an isolation cell closer to the entrance, Mansoor could glimpse the faces of other prisoners as they walked past him and they, in turn, could peer into his cell. During those first years he could only stare out that window into the empty cell across from his.

The severity of solitary confinement and its potentially devastating effects on the health and wellbeing of those subjected to it are recognized under international law. The Mandela Rules define solitary confinement as confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact. Prolonged solitary confinement refers to solitary confinement for a time period in excess of 15 consecutive days.

The Mandela Rules state that, “Solitary confinement shall be used only in exceptional cases as a last resort, for as short a time as possible and subject to independent review, and only pursuant to the authorization by a competent authority.”[26]

The UAE’s law on the regulation of penal institutions allows for seven days in solitary confinement as a form of disciplinary sanction when a prisoner violates the prison’s rules and regulations and only after an investigation is conducted and the prisoner allowed to provide a statement.[27] Yet UAE authorities have subjected Mansoor, without explanation, to indefinite solitary confinement – almost four years in isolation without an end in sight.

The indefinite solitary confinement of a human rights defender convicted on unjust charges following an unfair trial cannot conceivably be considered proportionate and necessary, let alone lawful. International treaty bodies and human rights experts—including the Human Rights Committee, the Committee against Torture, and both the current and former UN special rapporteurs ontTorture —have concluded that, depending on the specific conditions, the duration, and the prisoners on whom it is imposed, solitary confinement may amount to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment that violates their human rights. In an October 2011 statement, the UN special rapporteur on torture said that indefinite and prolonged solitary confinement in excess of 15 days should be subject to an absolute prohibition, citing scientific studies that have established that even a few days of social isolation cause irreparable harm, including lasting psychological damage.[28]

Ill-treatment

State security forces interrogated Mansoor several times in custody before his trial began. During his last interrogation, in December 2017, Mansoor rejected interrogators’ demands to hand over his Twitter account password. He returned to his cell late that evening to find that prison guards had entered in his absence and snatched away his clothes, his mattress, all his personal hygiene products, all his towels but one, and his papers and pens.

They left behind a prayer rug, a wristwatch, one sports shirt (with its long sleeves torn off), and two blankets, leaving him without adequate protection from the cold desert nights. To make matters worse, the prison administration also cut off his supply of hot water during the harshest winter months and denied him hot tea and access to the canteen. He has been forced to sleep on the floor since then, with no bed or mattress.[29]

Mansoor endured these brutal conditions for three long months, until just one day ahead of his first trial date on March 14, 2018. As a result, he suffered several severe colds accompanied by high fever. He also developed high blood pressure, for which he now requires medication.

According to former prisoners, a couple of days after the court announced Mansoor’s verdict, in May 2018, prison guards posted a note on the door of his cell saying the following: “It is strictly forbidden to leave the cell except in case of emergency or as per security orders and by consulting with the Security Information Branch. It is prohibited to contact or visit except with the approval of the director of the branch or the deputy director of the branch." The “Security Information Branch” likely refers to the state security office within al-Sadr prison. The note was posted on every cell Mansoor was moved to from that point onwards until July 2019, when he was briefly moved to a solitary cell outside of the isolation ward.

The UAE State Security Agency

From the moment he was arrested and until the present day, one state agency has been directly and entirely responsible for everything related to Mansoor’s imprisonment: the powerful State Security Agency. According to the source, the agency alone has been responsible for determining his conditions of detention and deciding whether to grant any of Mansoor’s demands for better treatment.

The mandate, objectives, and powers of the state security agency are outlined in Federal Law No. 2 of 2003, later amended by federal decree in 2011. Despite the UAE’s claims to the contrary, in its response to the May 2015 report by the UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, neither the law nor the amendment can be found in the UAE official gazette or elsewhere online.[30] In 2019, Human Rights Watch managed to acquire an unpublished copy of the 2003 law, but not the 2011 decree amending it.

Under the 2003 law, the State Security Agency reports directly to the president of the UAE, who since 2004 has been Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed al-Nahyan. The law authorizes the agency to “take any action inside or outside the state to protect state security within the limits of the law and other legislation.”[31] It also authorizes the agency to curb any political or organized activity by an individual or association that “may compromise the state’s safety and security, the system of governance, or national unity; harm the economy; or weaken the status of the state and provoke hostility against it or undermine confidence in it.” State security officials “may use force to the extent necessary” to carry out their duties.

The state security agency also has the authority to embed state security offices in federal ministries, public institutions, and semi-governmental corporations and organizations, as well as embassies and consulates. It has the authority to deny, halt, or approve access to key rights and government services, including access to jobs, higher education, and travel outside the country. Neither citizens nor UAE residents can appeal such decisions made on state security grounds without a clear legal basis.

Hunger Strikes

After Mansoor had exhausted all the means available to him to claim his rights as a prisoner – first, through the state security’s public prosecution, then the prison administration, then the courts – he finally resorted to the most extreme form of peaceful protest –a hunger strike.

He began his first hunger strike on March 17, 2019, nearly two years after his arrest and three months after the Federal Supreme Court upheld his conviction and 10-year sentence. He ended it 25 days later, on April 10.[32]

His demands were:

1. An end to his solitary confinement.

2. The right to make regular phone calls like prisoners in other wards. (In al-Sadr prison, most prisoners, excluding those held in the isolation ward and what is known as the state security ward, are granted a 20-minute phone call every two hours for four to six days of the week)

3. The right to family visits on a par with other prisoners. (In the first year and a half, he was granted one half-hour visit every six months with his wife and children, and since November 2018, once a month, but still excluding his mother and siblings)

4. The right to access the prison library.

5. The right to exercise in the prison yard and access to sunlight.

6. The right to access television.

7. Permission to buy a radio, plastic cups for tea and coffee, sports shoes, and adequate clothes.

8. Basic, necessary items such as a mattress, bed, chair, new blankets, nail clippers, personal hygiene products, products to clean his cell, and a razor once a month.

9. A copy of the Federal Supreme Court ruling denying his appeal.

During a meeting, three senior officers promised Mansoor that his demands - except for ending solitary confinement - would be met if he ended his hunger strike, which he did on April 10. The authorities only met two demands. He was allowed outside once to see the sun and most importantly, he was allowed to make a phone call on April 29, 2019, for the first time since his arrest two years prior. The call to his mother and wife lasted barely 10 minutes. It was the first time he had been able to speak with his mother, who was ill, since his detention started. Prison officials informed him that from that point onwards he would be allowed two 10-minute calls a month, but only to his wife and mother. This is a violation of international standards on the treatment of prisoners, which Mansoor protested.

Mansoor began a second hunger strike six months later, in early September 2019, and held out for 49 days, losing more than 11 kgs of weight.[33] His demands remained the same. With no access to the outside world, international rights groups including Human Rights Watch and the Gulf Centre for Human Rights did not learn that he had ended his hunger strike until several months later.

According to a former prisoner who contacted GCHR on December 10, 2020, “after Mansoor began his hunger strike in September 2019, he was forced to eat every few days by the guards, but they stopped force-feeding him and he was on continuous hunger strike” afterwards.[34]

Mansoor agreed to end his second hunger strike only after a senior officer twice visited his cell and again promised that he would be granted his right to regular phone calls equal to most prisoners in al-Sadr, access to the library, exercise, sunlight, and visits from his mother and siblings. As a result of his second strike, which lasted a debilitating 49 days, prison officials granted Mansoor the right to exercise and access to sunlight three times a week for an hour each time, and his mother’s name was added to the list of those allowed to visit with him. He was finally allowed to use a nail clipper, but only upon request (a former prisoner who contacted GCHR in December 2019 reported that Mansoor’s nails were extremely long when he had last seen him in October 2019). When Mansoor is scheduled to use the exercise yard, all other prisoners are removed. His other demands remain unmet.

Monitored Communications

All of Mansoor’s phone calls are actively monitored by the prison administration and promptly cut off if someone other than his wife or mother attempts to join a call. Visits with his wife and children take place in a designated room, in the presence of two or three officers. According to GCHR, he has had no in-person visits since January 2020, nearly two months before UAE authorities imposed pandemic-related regulations on prisons that banned in-person visits. From April 2020 until at least June 2020, authorities also denied him access to phone his family.[35]

IV. A Complacent International Community

Mansoor’s convictions and sentence, resulting from his exercise of his right to free speech, his political opinions and his status as a human rights defender, as well as his dehumanizing detention conditions, represent acts of brutal state repression.

Every UAE state institution involved in Mansoor’s conviction, persecution, and extrajudicial punishment shares responsibility for the grave abuses that violate his rights under both UAE laws and international human rights law. Both the Abu Dhabi Court of Appeals and the Supreme Federal Court failed to properly investigate Mansoor’s indefinite solitary confinement and the deprivation of his basic rights as prisoner, even though his treatment constitutes a clear and explicit violation of UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. By holding Mansoor in isolation for nearly four years, a crime that very likely amounts to torture, UAE authorities are in violation of their obligations under the UN Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment, which the UAE ratified and acceded to in 2012.[36] The targeting of Mansoor by the state security agency because of his legitimate and peaceful human rights work demonstrates just how dangerous and vicious this agency has become.

The UAE has largely remained insulated from meaningful criticism by its closest allies, including countries that purport to support human rights. Over the past few years, its rulers have invested considerably in promoting the UAE as an open, tolerant, and rights-respecting country, a strategy that has helped undermine efforts to hold the government accountable for grave human rights violations both at home and in conflicts in Yemen and Libya. Instead, the UAE’s bilateral relations with key countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and France have grown closer and more extensive.

Apart from the exceedingly brief mentions in the US State Department’s annual human rights reports, there has been no public criticism of the UAE’s terrible human rights record from the White House or the executive branch. Their collaboration on issues of defense, trade, and cultural exchange has only increased over the past decade; in the final days of the Trump administration, the US designated the UAE a “Major Security Partner.”[37] Washington sells billions of dollars’ worth of weapons to the UAE despite extensive documentation of the UAE’s repeated and ongoing unlawful attacks in Yemen and Libya, and its direct support for abusive local forces in both countries, risking complicity in war crimes.

The United States is not the only country that sells weapons to the UAE, but it is its number one arms supplier, accounting for 50 percent of all sales between 2000 and 2019.[38] France comes in second place, accounting for 25 percent of all sales for that same time period.[39] An April 2019 report by French investigative website Disclose said that French-made weaponry sold to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, including Leclerc-type tanks and Mirage 2000-9 fighter planes, “may have been used to commit war crimes” in Yemen.[40]

While historically not one of the top five exporters of weaponry to the UAE, between 2017 and 2020, the UK approved exports licenses for military goods totaling £206 million.[41] The UK Foreign Office, in its most recent annual Human Rights and Democracy Report, does not mention the UAE among countries of concern.[42] And in the last year alone, Germany approved over 1 billion euros in arms sales to the Middle East, over 50 million euros of which were for the UAE.[43]

EU foreign affairs officials too have noticeably failed to call for Mansoor’s release. The European Union External Action Service noted blandly in its statement on Mansoor’s case that “no one shall be detained merely on the grounds of peacefully expressing his or her opinions.”[44] Human Rights Watch has been unable to find a single public official statement from Washington or any European capital criticizing Mansoor’s persecution.

UN rights experts, the European Parliament, US Congress members, Nobel prize winners, well-known authors, prominent intellectuals and international political figures have decried his imprisonment.[45] And international human rights organizations, including the Gulf Centre for Human Rights, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch, continue to advocate on his behalf.

While UAE authorities have on occasion felt compelled to respond to criticism by denying allegations of ill-treatment and claiming Mansoor is being afforded all his rights under domestic laws, they ignore repeated calls to open the country’s prisons and detention centres for inspection by international, independent monitors and to allow such monitors access to Mansoor and other political detainees.[46]

UAE officials have also, at times, responded to criticism of Mansoor’s detention by intentionally misrepresenting the reasons behind it. In June 2019, five US senators wrote to the UAE ambassador in Washington, Yousef Al Otaiba, requesting “an update on [Ahmed Mansoor’s] well-being and plans for a timely release.” Al Otaiba responded by asserting that Mansoor had engaged in “impermissible sectarian hate speech” and “incite[d] violence.” Neither Ambassador Al Otaiba nor any other UAE official has ever produced a single statement of Mansoor’s that would fit such a characterization, and neither accusation was included in the charges on which the UAE court eventually convicted him.[47]

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Hiba Zayadin, Gulf researcher for Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa Division, with research support from Khalid Ibrahim, executive director at the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR). Adam Coogle and Joe Stork, Middle East deputy directors, and Kristina Stockwood and Michael Khambatta, GCHR representatives, edited and reviewed the report. Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor, and Tom Porteous, deputy program director, provided legal and program reviews. An associate in the Middle East and North Africa division provided editorial assistance.

Human Rights Watch and the Gulf Centre for Human Rights would like to express gratitude to former prisoners in the UAE’s al-Sadr prison who shared with us their experiences of life in detention.