Summary

Before our lives were simple, not rich, but enough. Since oil palm came there is more suffering. I can’t feed my family. I have a baby. I must put food on the table every day. How do I do that when both of us [my husband and I] are not working. Every day I must figure out how to do this.

—Leni, Semunying Bongkang, May 2018

A decade and a half ago, lush forests with evergreen fruit-bearing rambutan trees surrounded the home of Leni, a 43-year-old Iban Dayak woman and mother of two, in Jagoi Babang district of West Kalimantan province—an area her Indigenous community has inhabited for centuries. Today, they have little land to farm and no forest in which to forage after the land was cleared to make way for an oil palm plantation run by an Indonesian company.

Thousands of kilometers away to the west, in Sarolangun regency of Jambi province on the island of Sumatra, an elderly Orang Rimba mother of nine children, Maliau, struggles to survive off land that once sustained her people, but which has since been decimated by an oil palm plantation that began operating in the area nearly three decades ago. “Life was better before,” Maliau said. “Women could find many types of food. Some wove mats from leaves and baskets. We made lamps from gum resin. Now we cannot find materials to make these.”

Leni and Maliau are among the thousands of Indigenous people and other rural communities whose lives have been devastated by oil palm plantations in Indonesia—the world’s largest palm oil exporter. Indonesia is home to about 50 to 70 million Indigenous people and over 2,330 Indigenous communities, about a quarter of the country’s population.

The struggles of those like Leni and Maliau are invisibly integrated into a range of consumer products. Palm oil derivatives make their way into many grocery store products including frozen pizzas, chocolate and hazelnut spreads, cookies, and margarine. They are also used in manufacturing numerous lotions and creams, soaps, makeup, candles, and detergent. Crude palm oil is also processed into biodiesel blend used in vehicles and industrial machinery.

A complex web of domestic and international companies is involved in growing palm fruit, converting palm fruit into oil, manufacturing ingredients, and finally using these ingredients to produce consumer products sold around the globe.

Based on interviews with over 100 people, including several dozen members of Indigenous communities and representatives from nongovernmental organizations (NGO), this report documents how the establishment and expansion of oil palm plantations in Indonesia has adversely affected Indigenous people’s rights to their forests, livelihood, food, water, and culture.

Human Rights Watch focused on the plantation operations of two companies—PT Ledo Lestari in Bengkayang regency of West Kalimantan province, and PT Sari Aditya Loka 1 in Sarolangun regency of Jambi province. Both of these oil palm plantations have had a devastating impact on the rights of two groups of Indigenous peoples: the Ibans—a subgroup of the Dayak peoples indigenous to Borneo (Kalimantan), and the Orang Rimbas—a semi-nomadic, forest-dependent Indigenous people in central Sumatra.

A patchwork of weak laws, exacerbated by poor government oversight, and the failure of oil palm plantation companies to fulfill their human rights due diligence responsibilities, have resulted in loss of land and livelihood opportunities for Indigenous people in West Kalimantan and Jambi in the projects we researched. These findings were consistent with previous Human Rights Watch research in 2003 and 2009, which highlighted the adverse impact of the pulp and paper industry in Sumatra, and corruption, poor oversight, and lack of corporate accountability in the Indonesian forestry sector in West Kalimantan, on Indigenous people and peasant communities.

Conflicts related to land have frequently been linked to oil palm plantations. Indonesia has about 14 million hectares of land planted with oil palm. There is no clear estimate of the number of land disputes that exist nor the number of households that have been displaced or lost access to their customary forests and lands, including farmland, due to oil palm plantation expansion into their villages. Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria (Consortium for Agrarian Reform, KPA), an Indonesian NGO, documented more than 650 land-related conflicts affecting over 650,000 households in 2017—the last year in which publicly available data is available. It estimated that, on average, there were nearly two land-related conflicts every day that year.

Deforestation on such massive scale has not only threatened the wellbeing and culture of the Indigenous population, but also has global significance, contributing to carbon emissions and heightened concerns around climate change.

Without needed government reforms—both legislative and oversight—Indigenous communities will continue to bear the brunt of the oil palm plantations’ impact, and risk losing their distinct identity. Indigenous peoples have an intrinsic relationship with their environments. Their traditions, knowledge, and cultural identity are deeply connected to the natural environments in which they live. Any disruption to their natural environments, as in the case of the Ibans and the Orang Rimbas, affects their culture, languages, knowledge, and unique traditions.

Successive governments in Indonesia have turned a blind eye to widespread forest clearance, facilitating the proliferation of oil palm plantations. Between 2001 to 2017, Indonesia lost 24 million hectares of forest cover, an area almost the size of the United Kingdom.

In 2018, President Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, announced a moratorium on new permits to oil palm plantations. This was a good start. But additional reforms are long overdue. With a renewed mandate to continue his presidency following his reelection in April 2019, President Jokowi has a renewed mandate to enact and implement reforms that protect right of Indigenous peoples to be recognized and to enjoy their community rights to land and forests.

Failure to Consult

A host of Indonesian laws, starting from 1999, made companies seeking to develop oil palm plantations responsible for consulting local communities at every stage of the project involving a series of government permits.

Semuning Bongkang and Pareh hamlets in West Kalimantan province, where PT Ledo Lestari started its operations in 2004, were home to about 93 Iban Dayak households. Human Rights Watch found no evidence of any consultations with affected households until after forests were significantly destroyed. Villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were surprised by the company’s operations, only realizing their lands and forests were going to be razed when bulldozers and other equipment rolled into the area. The companies had not organized systematic and meaningful consultations with Indigenous people at different stages of the project to understand the nature and extent of the human rights risks. Mormonus, 49, now the village leader of Semunying Jaya village (includes Pareh and Semunying Bongkang hamlets), said:

I was surprised to see big equipment near the river. I asked what the equipment was for and the operators told me it was to make the state road to Samarahan, Sarawak [in Malaysia]. I visited their base camp in 2005, a month after I was made village leader. I was told the company was called PT Ledo Lestari.

Similarly, in Sarolangun regency, where PT Sari Aditya Loka 1 started its operations in 1989, the company had ample opportunity to consult with the Orang Rimba to mitigate any ongoing harm after legal reforms introduced clear obligations to do so. International law provides for companies to have ongoing consultation. To date, it has failed to organize any meaningful consultations and reach agreement to provide remedies to the Orang Rimba who were forcibly evicted from their forests. The company responded that they obtained a right to cultivate the land from the state.

Lack of Just, Fair, and Equitable Compensation

The oil palm plantations not only destroyed Indigenous people’s forests, lands and the resources in them that they were using for generations but also failed to create any mechanism to explore restitution or provide just and fair compensation for losses suffered, in consultation with the Indigenous people impacted.

In West Kalimantan, after the Iban Dayak carried out a series of protests between 2004 and 2010, PT Ledo Lestari appears to have engaged in consultations to placate individuals to sell family land, but women from the community said they were not included in those discussions. The company made some monetary payouts ranging between 1 and 2 million Indonesian rupiah (IDR) (US$70 to 140) per hectare to some of the 93 households affected. But the monetary compensation did not account for loss of the community’s adat forest (literally, customary forests), wild rubber, and other forest products that women in particular used for food or as a source of revenue.

The distinct losses women experienced of passing on intergenerational knowledge and skills, such as weaving products they sold to supplement their incomes, as well as the loss of their unique culture, were not taken into account. Damage to the community’s cultural identity is palpable in the everyday experience of Indigenous peoples who have lost access to their ancestral forests. The damage is aggravated by the lack of plans to preserve what little remains, and to compensate for irreversible losses.

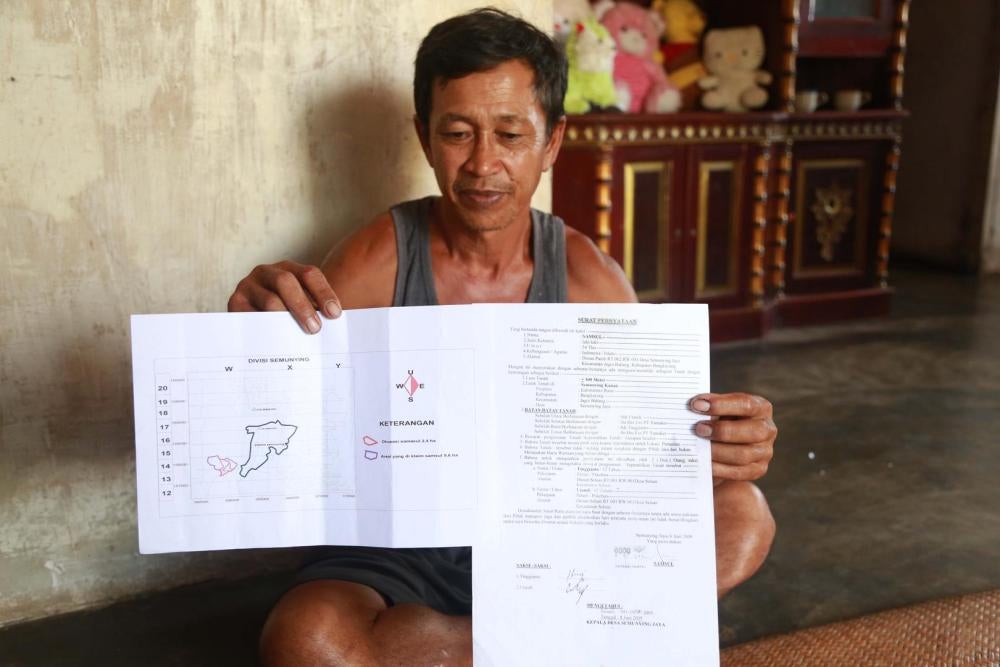

PT Ledo Lestari gave some of the 93 families “agreements” to sign. One that Human Rights Watch reviewed promised exchanging a house and yard for a new one a few kilometers away from their village. But community members said company representatives promised them a host of other measures, such as the ability to continue to harvest within their yards, land titles, shares from a plasma, or community plantation, that the company would set up, and other amenities including health clinics and schools, to lure them to leave the area. None of these have materialized. Their community is now enclaved within PT Ledo Lestari’s oil palm plantation. They said that in a few instances when community members dared to harvest oil palm fresh fruit bunches from their backyards to use as cooking fuel, the company security guards have branded them as “thieves.” Human Rights Watch wrote to PT Ledo Lestari on two occasions requesting their response and feedback but did not receive a response. Bengkayang police on several occasions have expressed willingness to mediate between the affected communities and PT Ledo Lestari.

Residents have noticed that, over time, the nearby Kumba and Semunying Rivers, which they rely on for drinking, fishing, and household chores, have become more polluted. Human Rights Watch could not independently verify their claims, but residents attribute pollution to increased soil erosion, the use of fertilizers, herb and pesticides, and effluents from the oil palm plantation that seep into the ground and rivers. Households living here have intergenerational knowledge of the water resources and fisheries that have been passed down through methods of sharing traditional knowledge. Based on this knowledge and lived experience, residents believe that the company’s operations and the pollutants in the river are related to a reduction of fish population in the nearby rivers. To catch fish to feed their families, they say they must ride out for an hour in boats. Women feel the impact of not being able to fish in nearby waters more deeply because they do not own boats. Residents said they can go a full day without catching fish in rivers close to their homes, forcing them to spend the little money they have, to buy fish. Francesca, a 28-year-old Iban Dayak woman from Semunying Bongkang, said:

Sometimes you see dead fish afloat on Sungai [River] Semunying…. It means something killed them—poison from the number of hectares of land covered by oil palm. When it rains, a lot of fish end up dead. We can’t eat that.

Today, in Jambi province in central Sumatra, the Orang Rimba community lives in abject poverty. Many have been left homeless, live in plastic tents, and without livelihood support. Orang Rimba Human Rights Watch interviewed said that they had once been self-sufficient but are now reduced to begging on the highway or “stealing” oil palm fruits from the plantation area to sell and make money. The plantation employs only a handful of the several hundred Orang Rimba adults estimated to live in the area. In September 2018, Human Rights Watch saw numerous Orang Rimba women and children begging for cash or food along a highway in Sarolangun.

PT Agro Astra Lestari, the parent company of Sari Aditya Loka 1, which operates the oil palm plantation in Jambi province, has a host of policies on sustainability, traceability, and grievance redress, that apply to all its subsidiaries and oil palm plantations. The company responded to Human Rights Watch communications about its impacts on the Orang Rimba community with a detailed summary of the education, health and economic services and programs it provided, including livelihood support for the Orang Rimba groups they were in contact with. Orang Rimba and local NGOs have approached the company to return some land to them but they say their efforts have proved futile.

PT Ledo Lestari, which operates the plantation in Bengkayang, West Kalimantan, does not have any published policies on sustainability or the protection of Indigenous people’s rights. It has also not engaged with Human Rights Watch or local NGOs.

Needed Government Reforms

President Jokowi should give priority to creating a high-level commission that includes representatives from Indigenous peoples’ groups to resolve land disputes involving Indigenous communities. This commission should ensure full women’s participation in its operations. Harmonizing complex legal frameworks regarding Indigenous land tenure should be a focus of the commission. Local Indigenous rights groups have long advocated for these reforms.

Customary rights of Indigenous people are lost in a maze of laws that were designed to protect them but do the opposite. As a result, Indonesia’s Indigenous people struggle to have their rights to customary land recognized. A vast number of Indigenous territories have been mapped, but local NGOs say very few Indigenous communities have been issued legal certificates.

To address this longstanding problem, President Jokowi should prioritize consultations with representatives of Indigenous groups to finalize a bill that would protect Indigenous peoples’ rights and ensure that simple recognition procedures are put in place. This would go a long way in implementing a 2013 Constitutional Court decision that granted Indigenous people rights to their customary forests.

Adopting new laws and a high-level commission are critical to ensuring the success of Jokowi’s 2018 “Complete Systematic Land Registration until 2025” program. The World Bank-funded initiative aims to register all land in Indonesia by 2025.

The Indonesian government’s 2011 certification mechanism, the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) system, accredits oil palm plantations that comply with Indonesian local laws and principles of social responsibility. The certification mechanism, which supplements the plethora of laws that govern land acquisition and oil palm cultivation, needs a rehaul. NGOs have criticized the ISPO for its narrow focus on national law, inadequate environmental protections, neglect of human rights, weak monitoring and oversight, lack of a grievance mechanism, and poor enforcement.

Finally, donors should support the Indonesian government in carrying out the host of reforms needed to protect Indigenous peoples’ rights. These should include creating a database to improve data collection and transparency on plantation concessions; related required permits; and numbers of land conflicts, their status, and their resolution. Currently, lack of data is exacerbated by putting some of the available information regarding plantation concessions behind paywalls. For example, the Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning has refused access to plantation permit data, citing a paywall, even after the Supreme Court upheld a freedom of information request in 2017.

Corporate Responsibilities

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights sets out company responsibilities independent of government obligations. The practical implication is that even where government oversight is poor, companies should have independent human rights due diligence mechanisms.

Human Rights Watch research in West Kalimantan and central Sumatra indicates that the companies were falling short of their human rights responsibilities.

Oil palm plantations and leading corporations within palm oil supply chains need to create and implement strong human rights due diligence procedures to ensure that palm oil production does not cause or contribute to human rights abuses of affected communities.

Companies, investors, and governments importing palm oil from Indonesia—including China, India, Pakistan, and the Netherlands—should closely monitor the reforms needed to ensure that oil palm plantations are not developed with such devastating human and environmental cost.

Introducing these reforms will allow Indonesia to support investments to improve its economy, while also protecting its forests and all those impacted by such investments, especially indigenous people.

Key Recommendations

To the Indonesian Government

- Urgently recognize and protect Indigenous peoples and their community rights to land and forests.

- Revise the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification system to align with international human rights standards.

- Establish a Land Dispute Resolution Mechanism.

To Oil Palm Plantation Companies in Indonesia

- PT Ledo Lestari and PT Sari Aditya Loka 1 should initiate mediation with affected communities and Indigenous peoples to resolve longstanding grievances, and offer compensation or remediation to those affected.

- All companies operating plantations should carry out robust human rights due diligence and provide just, fair, and equitable compensation in accordance with international human rights standards.

To Oil Palm Importing Countries

- Require companies to be transparent about their palm oil supply chains.

To Donors

- The World Bank and other donors should support the Indonesian government in carrying out the reforms needed to protect community and Indigenous people’s rights to land.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between February and September 2018, with field missions to Indonesia spanning 11 weeks. The research focused on oil palm plantation disputes involving Indigenous peoples’ claims to customary land and forests in Pareh and Semunying Bongkang hamlets of Semunying Jaya village in the Jagoi Babang district of Bengkayang regency in West Kalimantan province, and Orang Rimba groups in the Sarolangun regency of Jambi province in central Sumatra.

We based our research in Kalimantan and Sumatra because these islands have the most area in oil palm plantations with decade-long conflicts between companies and communities, including indigenous peoples.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with over 100 people from indigenous communities, and lawyers and NGO representatives working on land conflicts and related reform. Of these interviews, 57 were with ethnic Iban Dayak and Orang Rimba people, of which 42 were with women. Human Rights Watch conducted four interviews in groups of 3 to 10 people; all others were individual interviews.

The vast majority of the interviews were conducted in Indonesian, using female interpreters. The rest were in English.

Interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the data would be used. They were told they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time. They did not receive any compensation for participating in the research. They orally consented to the interview.

In August 2018, Human Rights Watch sent letters explaining our research and a list of questions requesting information to both PT Ledo Lestari and PT Sari Aditya Loka 1. The companies did not respond to our letters. In June 2019, Human Rights Watch hand-delivered another set of letters to both companies explaining our findings and including a list of questions. Letters were also emailed to PT Sari Aditya Loka 1 in August 2018 and June 2019. PT Ledo Lestari has not responded. In August 2019, Human Rights Watch received a letter via email from Bandung Sahari, vice-president of sustainability at PT Astra Agro Lestari Tbk.

In June 2019, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to the Office of the President of Indonesia explaining our general findings related to land conflicts, including a list of questions. In July 2019, Human Rights Watch sent text messages and called local government officials in West Kalimantan and Jambi provinces to explain our findings and get their responses. We had a telephone conversation with a Ministry of Social Services official in Sarolangun regency, Jambi province, which has been incorporated into the report. We await responses from other officials we contacted.

Researchers reviewed primary data sources, including laws, ministerial regulations, three court decisions, and other legal documents related to the plantation operations we investigated in West Kalimantan and central Sumatra. We also reviewed secondary data sources such as reports from NGOs and research institutes, and media publications to corroborate our findings.

We have used pseudonyms for individuals we interviewed to protect them. In some cases, further identifying details have been withheld to prevent reprisals.

The exchange rate at the time of publication was approximately US$1 = 14,287 Indonesian rupiah (IDR); this rate has been used for conversions in the text, which have generally been rounded to the nearest dollar.

I. Indonesian Palm Oil and Land Conflicts

Consumers may use palm every day without realizing it. Palm oil is the edible vegetable oil of oil palm fruit. It is found in a wide variety of products, including some cosmetics, pizza dough, instant noodles, ice cream, confectionery, soaps, shampoos, detergent, and biodiesel.[1]

A complex web of local and international companies is involved in the different stages of growing oil palm fruit and manufacturing these everyday products. These include companies cultivating and operating large oil palm plantations, extracting and refining palm oil, manufacturing ingredients, and using the ingredients to make and sell products globally. Foreign and domestic companies—both private and state-owned—buy and develop large swathes of lands for oil palm plantations.[2]

Top Palm Oil Producer

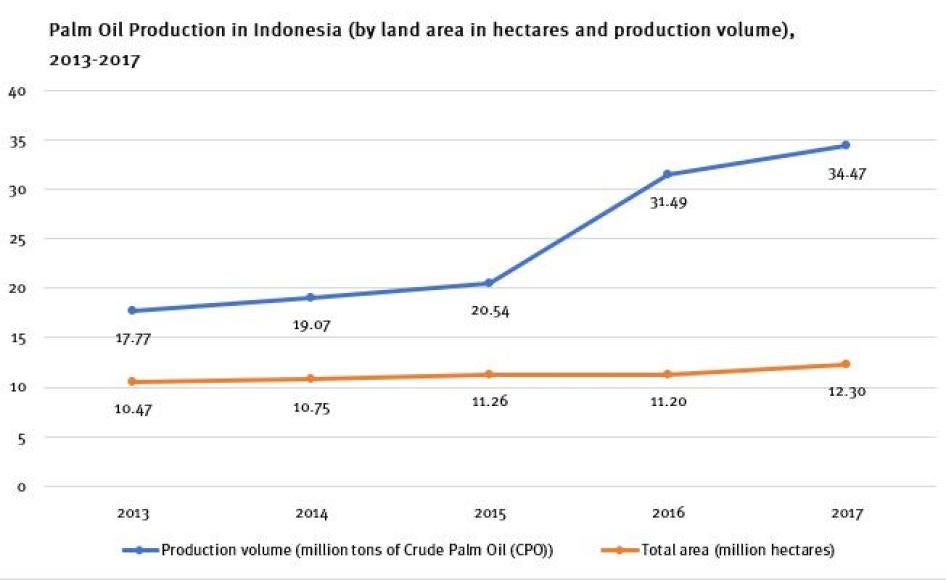

Indonesia is the world’s largest palm oil producer and exporter. In 2018, the country produced more than 40 billion tons of palm oil, more than half of the world’s total production and more than double the production of Malaysia, the second largest producer.[3] In 2017, Indonesia exported an estimated 75 percent of its palm oil, primarily to Asia—China, Vietnam, India, and Pakistan are its largest markets—followed by Africa and the European Union.[4]

Palm oil production is projected to grow in the coming years, propelled by the global demand for biodiesel.[5] But the demand is expected to decline in the EU, which has responded to environmental concerns around palm oil production by limiting its use in the transport sector. The EU has announced a cap on all palm oil imports for biofuel at 2019 levels until 2023, and a total phase-out by 2030.[6]

Rapidly Declining Forest Cover

Palm oil production has resulted in massive forest loss. Between 2001 and 2017, commercial ventures in Indonesia destroyed more than 24 million hectares of its tree cover, an area nearly as large as the United Kingdom.[7] Government sources estimate that oil palm plantations account for over half of all forest depletion in Indonesia during this period, with more than 12.3 million hectares of land under oil palm production.[8]

Companies have cleared and burned forests for oil palm and paper pulp plantations,[9] undermining natural carbon sinks and contributing to serious air pollution, risks to respiratory health across the region,[10] and a spike in carbon emissions.[11] Experts project that loss of forest cover at the continued rate will have serious climate change ramifications associated with frequent droughts, heat waves, and sea level rise effects in coastal areas.[12]

Pervasiveness of Land Conflicts

Oil palm plantations are contributing to the rapid disappearance of Indonesia’s forests, and to numerous resulting conflicts over land ownership and use. Many of these disputes involve Indigenous people that live in and around the forests. Indonesia is home to about 50 to 70 million Indigenous peoples, accounting for about a quarter of the country’s population.[13]

Over the years, these conflicts have continued, exacerbated by a combination of poor protection for Indigenous peoples’ land rights and complex land governance systems that fail to prevent or resolve disputes.

Number of Oil Palm-Related Land Disputes

While comprehensive and up-to-date official data on land conflicts is hard to obtain, piecemeal data from different authorities gives an insight into the problem.

For example, between 2012 and 2014 (the latest years for which public information is available), Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) received over 4,800 complaints—20 percent of all complaints—related to land.[14] In 2016, the commission projected that land disputes between communities and companies, including those over Indigenous peoples’ customary forests, would increase.[15]

According to the Ombudsman Republik Indonesia (Ombudsman RI), an independent government body that investigates complaints against maladministration, oil palm plantations contributed to the highest number of conflicts across all sectors in 2016 and 2017.[16] In 2017, the Ombudsman received 450 reports of land-related conflicts, with 163 conflicts implicating oil palm plantations.[17] In 2018, it recorded more than 1,000 land complaints by communities, including Indigenous people against companies.[18]

In 2017, Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria (Consortium for Agrarian Reform, KPA), a coalition of 153 peoples’ (peasants, Indigenous, women, fisherfolk, and urban poor) organizations, documented about 659 “agrarian conflicts” (disputes related to land) across the country, affecting more than 650,000 households.[19]

Indigenous Peoples’ Struggle to be Legally Recognized

At the heart of land conflicts involving Indigenous peoples and corporations lies the struggle of various Indigenous groups for legal recognition of their identity and collective rights. Local nongovernmental organizations (NGO) have repeatedly called for effective, streamlined, and time-bound procedures to recognize and protect Indigenous peoples’ land rights.

According to local experts on Indigenous peoples’ rights, over 2,330 distinct Indigenous communities are spread across the archipelago.[20] But there is no official data about the number of these that are legally recognized. One NGO noted that authorities recognized 18 Indigenous communities between 2015 and 2017.[21] In April 2019, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry issued a map of customary forests covering an area of 472,981 hectares, with a plan to identify, verify, and validate other customary areas.[22]

Indonesia’s constitution and laws recognize that adat (literally, custom or tradition) communities exist and affirm their communal rights to land.[23] In practice, realizing these rights entail cumbersome processes in which Indigenous groups have to prove their existence and register their land rights. Without legal recognition, groups that self-identify as Indigenous cannot register collective rights to land.

Maze of Procedures for Legal Recognition of Indigenous Peoples

The customary rights of Indigenous people are lost in a maze of Indonesian laws that were designed to protect them, but which in practice do the opposite. Several national laws and regulations outline procedures for Indigenous peoples’ legal recognition of their identity and community land rights,[24] the earliest of which dates to 1999 and the most recent to 2016.[25]

First, a group that self-identifies as Indigenous needs to apply to be legally recognized. But most districts have not established recognition procedures.[26] Where districts and provinces have set up procedures, the regulations establish between four and seven criteria that need to be satisfied for recognition.[27] Authorities take years to process applications: local NGOs such as Badan Registrasi Wilayah Adat (BRWA), said Indigenous peoples that filed applications as far back as 2011 are still waiting to be officially recognized.[28]

After it acquires legal recognition, an Indigenous community then needs to apply to different authorities at different levels—district, provincial, and national—seeking recognition of their rights to adat areas, forests, institutions, and knowledge. These processes are burdensome and difficult to track.[29]

Despite the vast number of Indigenous territories that have been mapped, local NGOs say very few have been legally recognized. As of December 2018, a leading local nongovernmental initiative has mapped out over 1,100 Indigenous territories spread over more than 14 million hectares.[30] According to Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago Indonesia, AMAN-West Kalimantan), an Indigenous people’s organization in West Kalimantan, only two Indigenous groups were able to register their communal rights in West Kalimantan.[31]

Landmark Judgment Remains Unimplemented

In May 2013, the Indonesian Constitutional Court handed down a landmark judgment that granted Indigenous peoples rights to their customary forests. Before this decision, all forests (including customary) were legally considered a part of state-owned forests; authorities granted Indigenous communities living in and around these forests limited use rights.[32]

The court decision prevents government authorities from issuing permits for land-based investments on adat forests without taking into account the rights of Indigenous people who live in and around it.[33] However, six years after the decision was rendered, United Nations and other experts have found little implementation of the verdict.[34]

More Policy Commitments and Legislative Demands Unmet

The next big legal and policy milestones that sought to recognize the Indigenous peoples’ rights came in 2015. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry required local governments to demarcate and protect customary forests.[35] The same year, the government’s National Medium-Term Development Plan 2015-2019 set a target to map out and establish community forests on more than five million hectares of customary forest.[36]

Despite this ambitious plan, government authorities have so far done little to identify and protect Indigenous people’s customary forests. In 2016 and 2017, President Jokowi handed over 29,500 hectares of customary forest to 18 Indigenous communities, which was far short of what was pledged in the country’s 2015 development plan.[37] According to official data, as of April 1, 2019, Indonesia had established 49 customary forests with a total area of about 32,791 hectares within its agrarian reform plan.[38] In 2018, Jokowi announced a moratorium on new oil palm plantation permits, an attempt to stop further deforestation and protect the environment.[39]

Key Legal Processes and Responsibilities of Plantation Companies

Several Indonesian laws and regulations lay out the permits required to acquire land and establish a plantation. Companies should make these applications to relevant local authorities and conduct environment and social impact assessments, which involve consultations with local communities expected to be impacted.

Acquiring Permits

In order to set up an oil palm plantation, Indonesian law requires that a company obtain a series of government permits from different departments. These include a location permit (Izin Lokasi),[40] which the governor, or bupati, is supposed to issue after reviewing the ownership and any competing rights over the land.

Before starting its plantation operations, the company should also conduct an environmental and social impact assessment (Analisis Mengenai Dampak Lingkungan or AMDAL) and receive an environment permit (Izin Lingkungan) from the district or provincial authorities[41]; a plantation permit (Izin Usaha Perkebunan or IUP) at the district or provincial level[42]; a forest conversion permit from Ministry of Forestry where the land assigned to the company overlaps with forests[43]; and finally, a right to “exploit” (Hak Guna Usaha or HGU) or cultivate permit, from the provincial land office.[44]

Duties to Consult Communities Prior to Acquiring Permits

Various laws and regulations require companies to consult with affected communities as part of their application and prior to acquiring permits[45]:

a) Before a location permit is issued[46]: The different stages of consultations include disseminating information about the project, collecting information on social and environmental baseline, and participation of affected communities in finding solutions to issues such as displacement.[47]

b) Before a company obtains an environment permit and plantation permit: The environment and social impact assessment incorporates a community consultation.[48] If the community landowners and the company do not reach an agreement on solutions for social and environmental adverse impacts, the community may raise an objection with the AMDAL appraisal commission established by the relevant government official (minister, governor or regent).[49] Similarly, the company should conduct consultations as part of its plantation permit process.[50]

c) Before a company obtains a “right to cultivate” permit: The company should consult the rights holders of land within Indigenous lands or other lands with identified owners, to reach an agreement on the transfer of the land and compensation.[51]

In theory these steps seem clear and linear; in practice there are gaps and minimal government oversight over how a company conducts consultations.[52]

Local nongovernmental experts and lawyers who have assisted hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people affected by oil palm plantations in almost all provinces of Indonesia told Human Rights Watch there was barely any oversight over the manner companies complied with the consultation requirements under various laws.[53]

Community members have argued that in the past some government officials had bypassed important processes such as consultation during a land suitability survey (before a location permit is issued) or an AMDAL process (before a plantation permit or right-to-cultivate permit are issued) in issuing authorizations.[54] Currently, some of these authorization processes are done concurrently on a new online single submission process. Local experts say that social impact assessments, when undertaken at all, are largely a box-ticking exercise with little community participation.[55] In the two oil palm plantations that Human Rights Watch investigated, the community members said they found out about the investment plans after the company had obtained its location permit and other authorizations from local authorities.[56]

Other Key Duties: Compensation and “Plasma” Plantations

The 1999 Forestry Law and 2014 Plantation Law require that permit-holders pay compensation for a community’s loss of access to land to new forestry and agricultural projects.[57]

The law governing the process of acquiring a plantation permit also states that the authorizing official should verify that the company has planned to establish a “community plantation” or “plasma,” or provides other productive business opportunities for local communities.[58] The “community plantation” is a partnership scheme in which the company establishes a plantation for the community of at least 20 percent of the total land size the company cultivates. This partnership aims to benefit residents, including those displaced through credits, profit sharing, and other agreed forms of funding.[59]

“Sustainable Palm Oil” Certifications

There is a global palm oil certification standard–the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Many palm oil-producing countries, including Indonesia, also have a national standard.

Indonesian’s 2011 certification mechanism, the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO), supplements the plethora of laws that govern land acquisition and palm oil cultivation. The certification mechanism aims to improve the competitiveness of Indonesian palm oil in the global market, support commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and improve sustainability. It accredits oil palm plantations that comply with Indonesian local laws and principles of social responsibility.[60]

The ISPO system has no transparency goals as part of its certification mechanism. The ISPO certification is mandatory for all large oil palm plantation business actors in Indonesia with compliance dates and requirements varying on size of operations.[61] Government authorities can downgrade and revoke the business license of plantation companies that are not ISPO certified.[62]

In 2011, the year the ISPO was set up, the Indonesian Palm Oil Association, which represents more than 700 palm oil entrepreneurs, withdrew from the RSPO.[63] The RSPO is a multi-stakeholder initiative comprising more than 4,000 members, including oil palm growers, processors, traders, manufacturers, NGOs, and financial institutions, The RSPO implements a global standard for sustainable palm oil so that RSPO members comply with a set of environmental and social criteria to produce Certified Sustainable Palm Oil.[64]

In 2015, ISPO and RSPO published a joint study delineating their similarities and differences, with one main distinction being ISPO’s narrow focus on national law.[65] NGOs have criticized the ISPO for its inadequate environmental protections, neglecting human rights, weak monitoring and oversight (nonexistent grievance mechanisms), and poor enforcement.[66] The RSPO, while having its own problems and also widely criticized, is perceived by human rights advocates and civil society organizations as being better than the ISPO because it has a grievance mechanism, its certification system incorporates international law, and it requires supply chain transparency.[67]

II. The Human Cost of Oil Palm Plantations

Human Rights Watch researched the development and operation of two oil palm plantations in West Kalimantan and Jambi in central Sumatra that involved two large Indonesian companies. These oil palm plantations first started operations over a decade ago, subsequently expanded, and continue operating today.

Under the 2006 United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, companies have a responsibility to respect human rights. As part of their human rights due diligence, they need to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for their impacts on human rights, and have processes to remediate any adverse human rights impacts they cause or to which their operations contribute.

Human Rights Watch research found that the companies’ operations have not followed domestic laws and international human rights standards that safeguard the rights of Indigenous people and their customary rights, especially as they relate to forests. The Indigenous communities are still grappling with serious impacts on their human rights to a livelihood, access to food and water, and culture. To date, they have not been adequately compensated for their loss. The loss especially to Indigenous women has been ignored.

Case Study: PT Ledo Lestari, West Kalimantan Province

The forest used to supply all our needs. Now if the rains come, everything floods. The forest is gone. There is no way to hold back water. We can’t plant anything. We lost everything to palm oil.

—Lindan, 58-year-old mother of three with five grandchildren, Semunying Bongkang, May 2018

Forest means everything. Forest provides water. Water is blood … land is body, wood is breath. When we lost the forest, we lost everything. We can’t pray to the god of oil palm.

—Mormonus, village leader, Semunying Jaya, May 2018

Overview of Plantation Operations and Expansions

PT Ledo Lestari, an Indonesian oil palm plantation company, is a subsidiary of Darmex Agro Holding.[68] Darmex Agro is an oil palm grower, and processor and exporter of palm oil. PT Ledo Lestari’s operations in Semunying Bongkang and Pareh hamlets in Semunying Jaya village, located in Jagoi Babang district in Bengkayang regency of West Kalimantan province, first began in 2004.

The development of the oil palm plantation has destroyed the customary forests of the Iban Dayak, an Indigenous community living there, leaving them no option but to relocate. The local NGO AMAN-Kalimantan Barat (AMAN West Kalimantan), which has assisted the Indigenous people there for more than a decade, estimates that at least 93 households of Iban Dayak inhabited the area at the time the oil palm plantation began its operations.[69] Currently, most still live in the area but have family members working in Jagoi, or across the border in Sarawak, Malaysia to support their families.

As of August 2019, PT Ledo Lestari’s plantation does not appear on the ISPO webpage of certified companies.[70] Human Rights Watch has attempted to verify this with the company but have not received a response. In 2013, RSPO terminated the membership of its parent company, PT Darmex Agro, and another subsidiary, PT Dutapalma Nusantara, following complaints regarding their plantation operations.[71]

Iban Dayak: An Indigenous CommunityThe Ibans are a subgroup of the Dayak peoples indigenous to Borneo (Kalimantan). Most Ibans live in Malaysia’s Sarawak state, Brunei, and in Indonesia’s West Kalimantan region. An estimated 2.2 million Dayak peoples lived in these parts at the turn of the 21st century.[72] The Dayak, including the Ibans, have complex religious practices centered around numerous spirits.[73] Most of their village economies are based on shifting cultivation of rice, fishing, and hunting.[74] Iban life and religion are intricately intertwined. Their culture is inextricably linked to the forests, rivers, fields, and the land. They use the adat forest for foraging and rituals. Their religious rituals are integrated with planting and harvesting, and include those pertaining to healing, birthing, and funerals. Ibans have a rich folklore filled with mythology and epics. Even though most Iban have converted to Christianity, they still practice some customs. The Temenggung (literally, “the highest Indigenous leader” in Indonesian) is the head of their traditional legal system, which has its own hierarchy.[75] They resolve disputes via a community forum, the Begulu (or Berkumpul, literally, gather together, in Indonesian).[76] |

Timeline of PT Ledo Lestari’s Operations in Semunying Jaya Village

Human Rights Watch pieced together information about the company’s operations in Semunying Bongkang and Pareh hamlets in Semunying Jaya village based on interviews with over two dozen Ibans living in the area, local NGOs assisting them, and government documents.[77]

Timeline of PT Ledo Lestari’s Operations in Semunying Jaya VillageDecember 2004: PT Ledo Lestari obtains a government location and cultivation permit for 20,000 hectares.[78] This included permission to acquire 1,420 hectares of adat forest that the Iban Dayak had used for generations.[79] 2005: Company begins clearing forests in and around the two hamlets, resulting in widespread protests by community members. 2006: Police detain two village officials on criminal charges related to the protest,[80] detaining them for nine days at Bengkayang Police station. 2006-2009: Villagers approach local authorities in the Bengkayang regency and West Kalimantan province to raise concerns about company’s ongoing expansion and operations. Late 2009: Bengkayang regency officials “inaugurate” a piece of forest within the area assigned to the company where the forest was still intact, which led communities to believe this recognized their claims over the forest and land. 2010: Company holds discussions with “heads of households” and resettles 32 households from Semunying Bongkang. The company negotiates with and compensates some families in Pareh and Semunying Bongkang. 2014: Villagers sue the company and the Bengkayang regency in district court, objecting to the oil palm plantation and seeks cancellation of permits, return of their customary land, and compensation for losses suffered. 2018: The lawsuit is unsuccessful because the community does not have a government certificate showing they are a recognized Indigenous group with customary rights to the land and forests. At time of writing, the community planned to appeal the decision. |

In 2018 and in 2019, Human Rights Watch wrote to PT Ledo Lestari seeking information about its operations, human rights risk assessments, and risk-prevention, mitigation, and remediation measures. The company has yet to respond.[81]

Failure to Consult Communities and Barriers to Effective Remedy

Iban Dayak residents said that PT Ledo Lestari did not consult with them before it began its operations, which would have been in violation of several Indonesian laws.[82]

More than two dozen community members told Human Rights Watch that neither the company nor the government gave them prior information about developing an oil palm plantation on their land and forests.[83] The residents of these hamlets only realized operations were about to begin in the area when they saw bulldozers in 2004.[84] Mormonus, 49, now the village leader, said:

I was surprised to see big equipment near the river. I asked what the equipment was for and the operators told me it was to make the state road to Samarahan, Sarawak [Malaysia]. I visited their base camp in 2005, a month after I was made village leader. I was told the company was called PT Ledo Lestari.[85]

Villagers suspected they were given false information when they saw the company’s workers arrive with more equipment, expand their construction camp, and cut through large swathes of their forests, rice fields, and rubber tree farms.[86]

Jamaluddin, the 57-year-old village council vice-chair, recalled painfully watching the company’s workers destroy the forests, and in anger and desperation even attempted to prevent their work: “The day they destroyed the adat forest we protested. We went there, intercepted, and threatened to burn their equipment.” He explained that the government brought in “the military,” and bulldozed their forest, ignoring their protests. “People were crying; I was also crying. I told everyone to not attack. We had just arrows and small knives. They had guns. We would not win,” he said. [87]

In January 2006, soon after the protests, police detained two village leaders, Mormonus and Jamaluddin from Semunying Jaya village, for organizing the protests. The two leaders told Human Rights Watch that while in the police lockup, someone who introduced himself by name as the director of the PT Duta Palm Nusantara group visited them, promised money, and offered to aid their release if they supported the oil palm plantation. Human Rights Watch wrote to PT Ledo Lestari on two occasions about this but received no response. Village leader Mormonus said, “He [the director] offered Jamal and me IDR 1 billion [US$71,000] each. He said, ‘It’s only adat forest, take money and buy any [other] forest.’”[88] They said they rejected the offer. They were released 10 days later but much of the forest was already decimated. The detention curbed further resistance to the plantation’s expansion as residents feared arrest.

Between 2006 and 2012, the Iban Dayak community approached various authorities at the district level and the provisional police, sometimes with the help of local NGOs such as Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia (Indonesia Forum for Environment, WALHI), AMAN, and Persatuan Dayak (Dayak Association), to file complaints against the company’s operations.[89] They also brought complaints to the Bengkayang Regency Plantation Development and Development Team, the National Human Rights Commission of West Kalimantan, and to Komnas HAM.[90] They said these complaints appear to have triggered government investigations but with no lasting solutions.[91] Bengkayang police on several occasions expressed a willingness to mediate between the affected communities and PT Ledo Lestari.[92]

Residents said that in late 2009 the Bengkayang regent (elected local government official) organized some ceremonies that the Iban Dayak community told Human Rights Watch that they interpreted was done to recognize their customary rights to parts of the forests that were still intact and within the area allocated to PT Ledo Lestari.[93] Community members said the “inauguration” was attended by local government officials, adat leaders and Iban Dayak community members, but not any representatives of the company.[94] Subsequently, the regent issued an order stipulating that the Semunying Jaya forest area was protected for seed sources.[95] But authorities did not issue a decree recognizing their customary forest and seemed to back away from any recognition of customary rights at all.[96]

In 2009 and 2010, after most of the surrounding forests were destroyed, company representatives held meetings with some community members—all men—in Pareh and Semunying Bongkang hamlets. The company sought to negotiate a compensation and rehabilitation package. None of the Iban Dayak women with whom Human Rights Watch spoke participated in the discussions. Even though these women were deeply impacted by the loss of the forests, the specific impacts on women (see below) went unaddressed.

In 2011, the head of the West Kalimantan Plantation Service, Hiarsolih Buchori, was quoted acknowledging that in the area map, part of the PT Ledo Lestari's plantation area overlapped with the community’s production forest but the relevant inspection report results were at the Directorate General of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation at the Ministry of Forestry and his office had not been given a copy.[97]

Inadequate Compensation and Unfulfilled Rehabilitation Promises

According to the Iban Dayak families whom Human Rights Watch interviewed in both villages, in 2010 PT Ledo Lestari negotiated compensation with some heads of families but this was done hastily without meaningful consultations.[98] Company promises made to convince villagers to sell their land have yet to be met.[99] These include oral promises of land titles, benefits from a “plasma” plantation, and other amenities, including health clinics and schools. The company did not account for the negative impacts on women, such as lost community networks they relied on, their livelihood from weaving, extreme hardships accessing land to grow food, and managing available resources to provide food for their families.[100]

In Semunying Bongkang, villagers said that the company asked families to sign relocation “agreements,” but these written documents fell far short of the oral promises made before relocating the families.[101]

Monetary Compensation

PT Ledo Lestari failed to compensate all affected families. It only compensated some residents for their loss of land cultivated with rubber trees and other crops such as rice paddies. Those who received compensation reported receiving between IDR 1 million and 2 million (US$70 to $140) per hectare per family.[102]

Families said that they did not know how this loss was quantified. They said the company did not systematically document each affected family’s losses, including the loss experienced by women, to arrive at a negotiated settlement. The company also failed to compensate the community for the loss of their Indigenous culture, which was inextricably linked with the forest and farming.

Relocation from Semunying Bongkang

In 2010, PT Ledo Lestari relocated all residents from Semunying Bongkang. The company resettled 21 families into permanent housing (constructed concrete buildings with metal sheet roofing) in another location in the plantation.[103] It placed 11 other families in “company camps” scattered around the plantation and who still await permanent homes.

Semunying Bongkang residents told Human Rights Watch that the resettlement followed written “agreements” families were expected to sign. Residents said that some weeks later people they identified as company representatives burned houses at the original site even before residents had removed all their belongings. Francesca, a 28-year-old mother of two, said she and her husband refused relocation and declined the “agreement.” She said that company representatives torched her home, rendering them homeless:

An assistant manager came to my home. On that day my oldest son had fever. He said to my husband, “Your five hectares of land here is gone and two hectares here is gone. Go to the company and get your money.” My husband told them he doesn’t want to sell. Months later, while I was at my mother’s new house [in the plantation] and my husband was away in Malaysia, we heard a loud noise and could see smoke. I went to see, and it was crazy. My house was already burned. Everything was in there, my son’s bicycle, clothes, and all the wood we planned to build a house, all was gone.[104]

Many of those who signed the “agreement” said they felt compelled to do so because their forests were already cleared.[105] Susanti, a 37-year-old single mother of four, said:

The [company] cleared the land and said I must move to another place. I had to sell my land or let them take it with no pay. I did this to survive. They [company] did not provide transportation for me to move my things [to new location]. They burned my wood and belongings I left behind.[106]

Families said the company did not consult them while choosing the relocation site. Two of the twenty-one new houses were on lowland that gets flooded after heavy rains.[107] Susanti described their living situation after they were relocated: “Before when the rains came it went into the river. Living here during the rainy season, it floods. My house and another were built too low. Water gets into the house.”[108]

Human Rights Watch reviewed a copy of a written “agreement.” PT Ledo Lestari had agreed to exchange one old village house and a backyard for new housing and a backyard.[109] But the document did not reflect the other oral promises that residents said company representatives made. Residents told Human Rights Watch that company representatives orally promised a host of other amenities to secure their relocation, including roads, church, clinic, school, pipe-borne water, ability to harvest palm within the yard of their homes, title to the land and house in the new area, and a plasma, or community plantation.[110]

To date, the company had yet to give the 21 families titles to the land on which they have been living.

The families were resettled in the middle of the palm plantation with restricted access to land for gardening.[111] Even though they said the company made oral promises to families that they could continue to harvest in the yard of their new house, they subsequently found themselves branded as “thieves” when they attempted to harvest anything within the small area. Leni, a 43-year-old resident in Semunying Bongkang, said:

The [oral] agreement with the company was that we can harvest within 50 meters in my yard. I was accused of stealing from the company because I harvested from a tree that was in my 50-meter yard. They said we could harvest from here to help pay school fees but they lied.[112]

Another resident said he was arrested in 2018 and that plantation security guards questioned him for harvesting palm nuts from a tree in his yard. His wife had dried out the palm chaff to use for lighting a cooking fire. The guards reported him to the plantation manager and detained him for “theft.” Samsul said, “I was detained for harvesting palm nuts in my own yard…. They had a picture of my wife drying palm chaff.”[113] He was later released but other residents saw the action as a warning that the land on which they live is not their own.

The “Plasma” Plantation Promise Unmet

Villagers said that PT Ledo Lestari reneged on its oral promises to residents that they would benefit from a plasma plantation,[114] which had influenced their decision to sell. Samsul, a 48-year-old man said, “The company promised electricity, water, health clinic, houses built with concrete, school and plasma. For plasma, we gave our land in 2010, I have not received any payment for plasma.”[115] Even after more than eight years, none of the residents had received any payments or other benefits from a plasma plantation; no one had any information concerning its planting, growth, or harvest estimations.

Key Adverse Human Rights Impacts

The oil palm plantations continue to have a devastating impact on the livelihoods of communities, especially women, and on their access to food, potable water, and their culture.

Livelihood

Before, our lives were simple, not rich but enough. Since oil palm came there is more suffering. I can’t feed my family. I have a baby; I must put food on the table every day. How do I do that when both of us are not working? Every day I must figure out how to do this.

—Leni, 43-year-old woman, Semunying Bongkang, May 2018

Prior to the oil palm plantation, the Iban Dayak depended for their livelihood on fishing in the nearby rivers of Kumba and Semunying, farming rice, and tapping rubber trees. Their daily diet consisted of rice and fish they farmed or caught themselves, and they generated household revenue for purchasing additional needs by selling natural rubber latex, rice, wood, tree bark, fish, and woven mats and baskets in nearby markets.[116]

PT Ledo Lestari’s failure to adequately compensate for the loss of livelihood—including households’ access to ready food sources—resulting from forest destruction continues to have an impact on these communities.

A 2011 blog posted on the West Kalimantan provincial government page reported:

PT Ledo Lestari's representative, Saut Hutapea, said, his party was ready to pay compensation in accordance with the agreed price and in accordance with the price list set by the government. ‘We also just found out that some of our plantations entered the production forest area when we got an explanation from the Forest Area Consolidation Center,’ Saut said, and that ‘we have asked the Regent of Bengkayang, why did our location permit enter the production forest area?’[117]

The oil palm plantation provided some paid employment for families from Semunying Bongkang and Pareh hamlets. But not all families are gainfully employed. According to the local NGO AMAN, only about 10 people in the 93 impacted households are employed by the oil palm plantation out of a total of about 2,920 employees.[118] AMAN West Kalimantan reported that villagers employed by the company earn between IDR 60,000 and IDR 80,000 per day (about US$4.25 to $5.65) for eight hours of work.[119] Prior to the introduction of the plantation to the area, the majority of household needs were met through resources within the forests. The available paid employment does not fully compensate for that loss. Many families said they were worse off than before the oil palm plantation.

Farming, a source of livelihood and food, has been deeply impacted. With the loss of their forest and farmland, residents in Semunying Bongkang and Pareh are forced to rent others’ lands in villages several kilometers away, outside the plantation area, adding to expenses.

Margareta, a resident in Pareh, described the difficulties women face in Semunying Bongkang and Pareh to access land for farming. Male migration and the feminization of agriculture means women need to access land for food production. Margareta said that women in Pareh could look for small pieces of land farther away from their village to rent and farm. But this was harder for women in Semunying Bongkang who live surrounded by oil palm. She said, “They can’t find land to rent. They must work in the company to be able to feed their families and it is hard work.” She described how her entire family in Semunying Jaya village had to sell their land after the forests were destroyed, and were struggling to pay their children’s school fees with the income they earned carrying heavy loads of palm fruit, cutting down dead palm fronds, and spreading chemicals (fertilizers, pest and herbicides) in the plantation.[120]

Rinni, a 38-year-old woman with three children, said:

When I had land, I could provide for me and my children. I could grow the crops I need. Now I walk a long distance to go to work [in the plantation]. They promised us health, education, housing, and land…. They [the company] don’t care about our health, they just want us as labor.[121]

A few parents said that their children were forced to drop out of school because they were no longer able to afford school expenses.[122] The children from both hamlets attend a primary school in Pareh, about a 30 minute walk from what was Semunying Bongkang. Older children attend high school in Jagoi, 20 kilometers away, which involves more school-related expenses.

Leni, a 43-year-old mother of four young children in Semunying Bongkang, said:

My daughter attends high school in Jagoi and had to drop out … because I have no money. Riding a motorbike to school requires two liters of gasoline daily. Placing her in a boarding house costs IDR 140,000 [$10] monthly plus uniforms. I don’t have money for that. I had a kiosk [food and goods stand] and my husband would go to the forest, cut wood and sell when there was a big expense like school needs. Now there is no forest.[123]

Women’s Incomes from Traditional Weaving VanishesWeaving, a source of livelihood for Iban women in Semunying Jaya village, has almost been wiped out. Traditionally, Iban women are renowned for their weaving skills and used a variety of forest products to make household items, including baskets, ropes, and mats, which they also sold in markets nearby to supplement their incomes.[124] The loss of the forest has not just eliminated another financial source, it has all but ruined an intergenerational craft form that had cultural significance for Iban women. For example, women told us that they used leaves from different trees to weave and make rutan or ropes; and pandan leaves for mats. But these are now scarce. Margareta, a woman who previously enjoyed weaving and selling her wares, said: Before the company, women would weave five or six meters while drying rice. Now it’s difficult to find pandan leaves. It’s become very scarce. Aka kuya [leaf of another tree] is the best because it’s most durable. Now we don’t have the materials.[125] Women sold extra baskets and mats in markets in Jagoi or in Malaysia. Some of their baskets with motifs sold for IDR 250,000 (US$17) each.[126] With the loss of their forests and materials needed to weave, not only have the women lost a source of income, but they are compelled to buy plastic baskets and mats for their household use, spending money they previously did not have to.[127] |

Food and Water

Sometimes you see dead fish afloat on Sungai [River] Semunying. We can’t eat fish that is caught dead. It means something killed them—poison from the number of hectares of land covered by oil palm. When it rains a lot of fish end up dead. We can’t eat that.[128]

—Francesca, 28-year-old Iban Dayak woman, Semunying Bongkang, May 2018

PT Ledo Lestari’s operations have severely impacted the Iban Dayak’s ability to farm, including for subsistence, and the population struggles for food. Paulina, a 37-year-old woman from Semunying Bongkang, said:

I can’t provide food every day like before. Before the company, I used to plant rice, and vegetables on a small piece of land. I would use the harvest to feed my family. Now, I plant a little behind my house, not much, and it doesn’t do well like in my farm before.[129]

Miun, a 70-year-old woman, said: “Long ago, when we had forest, men went into the forest to get meat. They would hunt and bring back wild pigs. Now with no forest our meals have no meat.”[130]

Families said that because fewer of them can farm, those who do face a greater risk of having crops destroyed by birds, who are drawn to the crops planted. Before the oil palm plantation, all families in the community planted and harvested at the same time, reducing the likelihood that any one family’s fields would be ravaged by birds.[131]

In Pareh, two women who had farmed for decades told us that their families had planted rice in 2017 in separate rented plots but harvested almost nothing because birds ate all their crop.[132] Kinda, a 48-year-old woman in Pareh, said: “I lost all of my harvest last year, Ibu Margareta too. Even though I watched with my husband, the birds came at night and ate the crop. I don’t even have seed rice to plant this year.”[133]

They said previously when they had their customary land, everyone in the two hamlets grew rice. This allowed families to coordinate rotational watch to keep birds from destroying the crop. Moreover, since there were at least 90 more rice farms back then in 2000, the women felt the loss from birds was not as great since it was shared by all.[134] “Families used to sit together to decide when and where to plant. We used to work together to plant and watch [for birds] the rice. Last year I rented land and planted in August. I lost everything,” Margareta said.[135]

Human Rights Watch is unaware of any public studies of the environmental impact of PT Ledo Lestari’s operations in Semunying Jaya village. Our repeated efforts to obtain such information from the company received no reply. Residents, based on their many years living in the area, expressed their concerns about what appeared to them to be the effect of oil palm cultivation and processing on the environment and their livelihoods.

Residents believed that the fish populations in the nearby Semunying and Kumba rivers had reduced since the company’s operations began. They have not had access to any environmental assessments by the company or government, if there are any. Instead, households living here have intergenerational knowledge of the water resources and fisheries that have been passed down through methods of sharing traditional knowledge. Based on this knowledge and lived experience, residents told Human Rights Watch that they have observed over the years since the company started its operations that the rivers had become more polluted. Human Rights Watch could not independently verify their claims, but they attribute this to increased soil erosion, use of fertilizers and pesticides, and depositing effluents from the oil palm plantation into the rivers.[136]

For example, one family was nostalgic about how easily they caught fish for more than three decades, catching about eight kilograms of fish a day: “I put the pukat [fishing net] in at night and used to get the fish in the morning.”[137] This allowed the family to eat and sell the extra fish. They said the average catch progressively declined after the plantation’s operations—though there could be various reasons for a decline in fish caught. The same family said they now sit out the whole day waiting to catch any fish even in the best fishing conditions.

Jampang, the 67-year-old community leader, said:

Now it’s hard to get fish because soil and mud gets into the pukat. Today, I rode an hour by my boat where there are rice fields and the river is not polluted by the palm plantation, to be able to catch three kilograms of fish.[138]

Women felt the impact of not being able to fish in nearby waters more deeply. Women do not own boats, and said they could go a full day without catching any fish in the rivers close to their homes, forcing them to spend money to buy fish. Leni, a 43-year-old woman, who had been fishing in the Semunying River since she was a teenager, said:

I lived next to Sungai [River] Semunying. When I had bait and threw in my line I immediately got fish. Now [after being resettled in plantation], I go out in the morning and till dark sometimes I have no fish. Most people here [resettlement] eat just once a day because we don’t have enough rice. Sometimes, I make porridge, so we can survive.[139]

A number of residents raised concerns about polluted river water, leaving them to seek other water sources. Some residents in Pareh believe the Kumba River they previously relied on for water to drink, cook, and perform household chores has been contaminated based on their observations of the visible water quality and their perceived skin sensitivities to it. For example, Kinda said, “The water [in the river] is contaminated.” She explained the basis for her assertion:

The company uses pesticides and when you bathe in it your body itches. When they put the pesticides [on the plantation] the river change to red and then black. People who use the river have rashes and ask the clinic [mobile health center] for medication. We can see it when the river is clean and when it’s not.[140]

Kinda says that community members waited for the rains to collect water for their bathe.

In 2018, the village council used its funds to pipe water into Pareh, reducing the community’s reliance on the Kumba River for consumption and household use.

The community also lost access to water when the company razed the forest and covered smaller water sources. Several villagers said water sources downstream have dried up, and they believe it is because the company rerouted some streams into irrigation canals for the plantation.[141] Most of the residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch believed the plantation disrupted their watershed—that is, all of the area that drains into their traditional water sources—but they had no official information about this. The village council cannot pipe water to residents from Semunying Bongkang because their relocated hamlet is in the plantation, forcing them to use what they believe is polluted water.[142]

Culture

The oil palm plantation has eroded the culture of the Iban Dayak. In interviews with Human Rights Watch, Iban Dayak said that their culture is inextricably linked to the forests, rivers, fields, and the land. They use the adat forest for foraging and rituals. Margareta, a 40-year-old mother of two children and a community leader in Pareh, said, “I know the forest because my grandparents used the adat forest for spiritual rituals. It was a sacred place.”[143]

Margareta said: “Our identity as Iban Dayak is almost lost now, we have no forest. Our grandfathers showed us where to cultivate in the forest, harvest fruits, and how to live together.”[144]

Jamaluddin, a 52-year-old man, said: “The loss of our forests has changed our customs, habit, and daily life. The forest used to supply all our needs. My life wasn’t so hard when I could sell tree bark or wooden planks in Malaysia. And it’s not just me but with everyone. Now we slave every day.”[145]

The company razed plants and trees integral to their customary life. Women showed baskets that had been made by their grandmothers, which they inherited at the time of marriage. Lindan, a 57-year-old woman said, “We can’t teach the next generation because there are no materials [leaves]. Learning the technique takes time. The motifs and flowers on the baskets tell a story, the story of the Iban.”[146]

Francesca mourned their incalculable loss: “We lost our community. When we weave, we talk, laugh, and are together. This place [new location inside the plantation] is not a village. You can’t call it home. These are shelters, not a community. It is owned by the company.”[147]

Human Rights Watch wrote to PT Ledo Lestari on two occasions requesting their response and feedback and did not receive a response. In 2012 a media outlet reported that a “legal staff of PT Ledo Lestari, Jufendiwan, explained that the 1,420 hectare land that was questioned by a number of residents had only been confirmed as a forest in 2010, ‘while we have obtained permission first.’”[148]

Case Study: PT Sari Aditya Loka 1, Jambi Province in Central Sumatra

Overview of Plantations and Expansion

PT Sari Aditya Loka 1, an Indonesia oil palm plantation, began operating three decades ago in Jambi province in central Sumatra. Since then, its operations have had harmful impacts on the Orang Rimba people, an Indigenous community living there. Human Rights Watch interviewed 31 Orang Rimba men and women who live in PT Sari Aditya Loka 1 plantation areas in Sarolangun regency.

PT Sari Aditya Loka 1 belongs to PT Astra Agro Lestari TBK, a publicly owned Indonesian company. Astra Agro Lestari’s ownership can be traced to Jardine Matheson Holding Ltd., a British conglomerate listed on the London Stock Exchange.[149] Agro Astra Lestari, one of Indonesia’s largest palm oil producers, takes pride in its sustainability and has a host of policies. These include sustainability, traceability, and grievance redress among others.[150] ISPO certified PT Sari Aditya Loka 1’s operations, both plantation and oil mill, in 2013[151] and audited them in January 2017.[152] This ISPO certification is valid until 2018.[153]

PT Sari Aditya Loka 1’s oil palm plantation is adjacent to the Bukit Duabelas National Park, whose park and surrounding forests are home to the Orang Rimba.

The company first started clearing forests to develop the plantation in 1989.[154] It obtained a government environment permit in 1995, which was renewed in 2006.[155] It has expanded its plantation since July 2006, covering a total of about 19,700 hectares of which about 13,155 hectares are for a “plasma” or community plantation.[156]

Local NGO Komunitas Konservasi Indonesia (WARSI), which has assisted the Orang Rimba for over two decades, estimated in 2017 that more than 750 Orang Rimba lived in 11 groups (rombongon) or camps in PT Sari Aditya Loka 1’s plantation’s area.[157]

Academics and researchers say that thousands of other Orang Rimba were driven to live inside the national park over the years for numerous reasons, including the operations of the oil palm plantation.[158] Those living in the national park have little contact with the outside world and Human Rights Watch was not able to interview them.

Ongoing Adverse Human Rights Impacts

As discussed below, PT Sari Aditya Loka 1’s operations have not adequately corrected the harms its operations have caused to the Orang Rimba.

Many Orang Rimba told Human Rights Watch that there were no discussions with government officials or company representatives prior to their land and forests being cleared and planted.[159] While the law in effect in 1989 cast no clear responsibilities on companies to consult with communities, companies carrying out operations since the adoption of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights should undertake ongoing human rights due diligence to identify risks and take steps to mitigate or remedy harm associated with their operations.

Meriau, the leader of a rombongon of about six families living in the middle of an oil palm plantation, said: “This used to be my rice field. That is why I don’t leave this place. I had asked the person who cleared my rice field, he said, ‘Ask the government.’ How do I ask the government?”[160]

Since the oil palm plantation operations began, the Orang Rimba have lived in the area without proper rehabilitation. Many Orang Rimba have been compelled to live in small groups of 5 to 10 families, pitching sudungs (a sheet of plastic tied to posts) in oil palm plantations, hurriedly moving frequently when discovered and chased by company employees. Human Rights Watch researchers witnessed several Orang Rimba women and children begging along the highway.[161]

Orang Rimba: An Indigenous PeopleThe Orang Rimba are a semi-nomadic Indigenous people with their own customs, forest-dependent livelihoods, religious beliefs, and community decision-making structures. According to anthropologists who have studied Orang Rimba custom, the community lives in small encampments (rombongon), each led by a headman (Temanggung). Each encampment comprises huts clustered together. Orang Rimba custom is to move every time someone in their encampment dies. They follow a matrilineal system but the community heads are men.[162] Before the oil palm plantation changed their lives, encampments varied in nomadic and sedentary practices.[163] Some were nomadic and depended exclusively on hunting and gathering; others practiced padi ladang (literally, “field rice”), a system of cultivating tubers or rice during one planting cycle and moving to another area after harvest.[164] |

Orang Rimba, with the assistance of local NGO WARSI, met with numerous government officials and plantation representatives between 1999 and 2018 to save their habitat and develop recommendations to improve their lives.[165] The government created a national park, Bukit Duabelas National Park, as a measure to mitigate forest and biodiversity loss; but Orang Rimba and WARSI said the company did not meet their human rights responsibilities by not compensating or returning land to Orang Rimba.[166]

In response to the question of inadequate consultation and compensation, the company said that it obtained the relevant permits from the government, which has authority over the land:

The presence of PT SAL in the Sarolangun region is due to Government’s request to help the Trans-Nucleaus Estate Plantation program, which began in 1987. …

The land cultivated by PT SAL is in the form of HGU. Therefore, the authority over the HGU land is in the hands of the State.[167]

Livelihood