“You Don’t Have Rights Here”

US Border Screening and Returns of Central Americans to Risk of Serious Harm

Summary

I told them, I cried, that I couldn’t go back to my country… but they deported us.

—Alicia R., deported from the United States following Border Patrol screening in August 2014 with her two children, ages 3 and 10, feared retribution from gang members in Honduras after witnessing the murder of her mother.[1]

Migrants from Central America and Mexico seek to enter the United States without authorization for many reasons. Some seek economic opportunity. Others are fleeing violent gangs in countries such as Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, where local officials may be complicit with gangs or otherwise unable or unwilling to provide meaningful protection. Many have mixed motives for leaving, including poverty, gang violence, and reuniting with separated family members.

At the US-Mexico border, US immigration officers issue deportation orders to unauthorized migrants in accelerated processes known as “expedited removal” or “reinstatement of removal.” These processes include rapid-fire screening for a migrant’s fear of persecution or torture upon return to their home country or an intention to apply for asylum. As detailed in this report, this cursory screening is failing to effectively identify people fleeing serious risks to their lives and safety.

In the past two decades, US laws and policies have become less responsive to the risks faced by arriving migrants seeking asylum from persecution. In 1996, and subsequently in 2006, the US government severely undermined the system for identifying asylum seekers through the establishment and expansion of expedited removal. The flaws of that approach are readily apparent today at the US-Mexico border.

This report is based on 35 interviews with Central American migrants in detention in the US or recently deported to Honduras. While focusing on the situation facing Hondurans, our findings and recommendations apply to others coming to the US from Central America and Mexico.

All migrants we interviewed expressed a fear of returning to Honduras. Some of those who had been returned to Honduras had fear so acute that they were living in hiding, afraid to go out in public. Several who were recently deported provided accounts that, if true, should qualify them for asylum in the US. They said that, prior to attempting to enter the US, they had been subject to serious threats from gangs in Honduras. These included small business owners who refused to make demanded payments to gangs; victims of or witnesses to gang crimes, including murder and rape; and fear of a gang forcibly recruiting a family’s young son. Others fled abusive domestic partners or violence related to sexual orientation, both grounds for asylum under US law.

Virtually all of those we interviewed who had been apprehended at or near the border were deported summarily, via expedited removal or reinstatement of removal. Many said they had expressed their fears to US Border Patrol officials charged with screening for fear of return before being deported, but fewer than half of these were referred by US Border Patrol for a further assessment of whether they had a “credible” or “reasonable” fear of returning to Honduras. US law requires that when a migrant in expedited or reinstatement of removal expresses a fear of return to their country of origin, they be referred to a US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) asylum officer for an interview to determine whether their fear might qualify them for asylum or other protection.

Human Rights Watch was unable to corroborate claims about the specific dangers interviewees said they faced in Honduras. However, the experiences they described and the fears they expressed should have led US immigration authorities to give their cases sufficient scrutiny before they were returned to their home country. The principle of nonrefoulement, the right not to be returned to a place where one would likely face threats to life or freedom or other serious harm, recognized under both US and international law, demands as much.

* * *

The vast majority of migrants crossing the US-Mexico border without authorization are placed in detention and undergo a hasty two-part assessment by US officials under either “expedited removal,” for first-time border crossers, or “reinstatement of removal,” for migrants who have previously been deported from the United States.

In either case, to pass the first stage an agent from Customs and Border Protection (CBP) or another US immigration agency must flag the person for a “credible fear” or “reasonable fear” assessment. To pass the second stage, migrants meet with an asylum officer from USCIS who determines whether their fear of return is “credible,” or in reinstatement cases, “reasonable” – that is, whether there is a significant possibility they will prevail in immigration court on their claim for asylum or protection from deportation to a country where they are likely to face torture.

While there is evidence that fewer people are passing through this second stage,[2] Human Rights Watch’s investigations in Honduras suggests that many asylum seekers are being turned away in the first stage. The failure of CBP and other US immigration agencies to identify asylum seekers raises concerns that the US government is violating its international human rights obligations to examine asylum claims before returning them to places where their lives or freedom would be threatened.

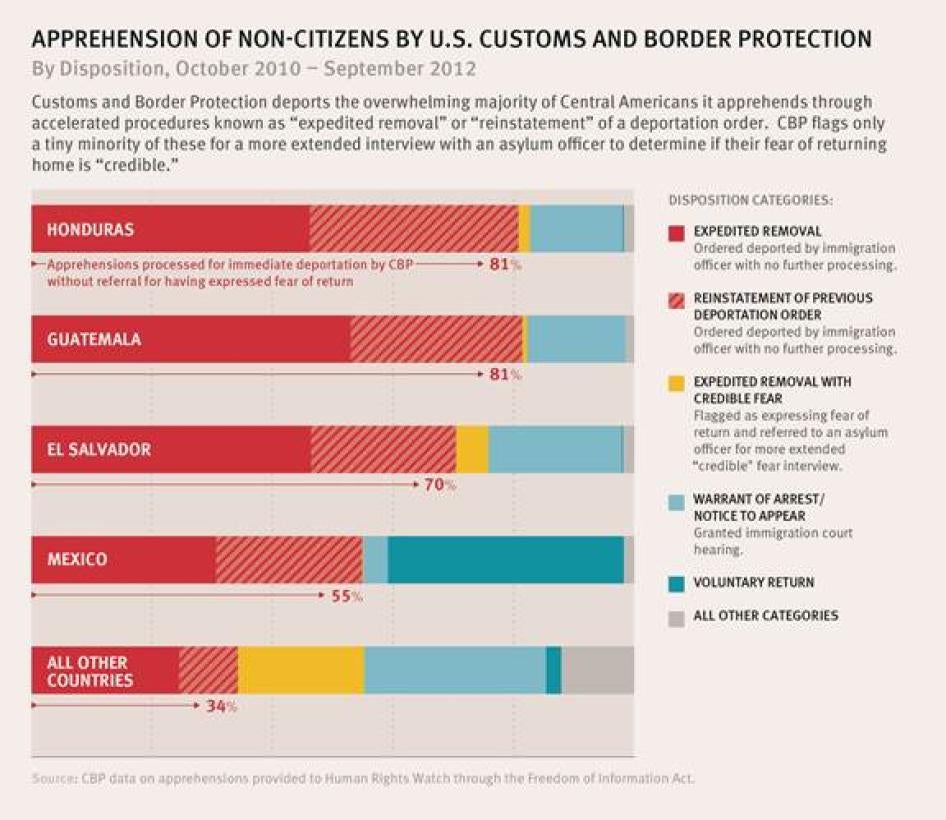

Data for 2011 and 2012 that Human Rights Watch obtained from Customs and Border Protection under the Freedom of Information Act indicate that few Central American migrants are identified by CBP as people who fear return to their country in the first stage of the expedited removal process. The data show that the vast majority of Hondurans, at least 80 percent, are placed in fast-track expedited removal and reinstatement of removal proceedings but only a minuscule minority, 1.9 percent, got flagged for credible fear assessments by CBP. The percentages for Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala are similar, ranging from 0.1 to 5.5 percent. By comparison, 21 percent of migrants from other countries who underwent the same proceedings in the same years were flagged for credible fear interviews by CBP.

CBP has a proactive duty to initially screen migrants for fear of return to their country of origin when it apprehends them crossing the border and places them in expedited or reinstatement of removal. However, a migrant may be identified as fearing return to their country by an immigration official after they have left CBP custody and entered the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the agency responsible for more prolonged detention of migrants. ICE, however, does not have a duty to proactively screen all migrants in its custody for their fear of return. It is telling, then, that the majority of credible and reasonable fear referrals that USCIS received in 2011 and 2012 did not come from CBP, but from ICE and other immigration agencies that learn of migrants’ fear of return on an ad-hoc basis. In 2012, for example, CBP referred only 615 of the 2,405 Hondurans who eventually were flagged for credible fear interviews by USCIS.[3] Approximately three-quarters of the credible fear referrals USCIS conducted in 2012 came from agencies other than the CBP, even though that year CBP was responsible for approximately 57 percent of all noncitizen apprehensions.

Migrants who feared returning to Honduras told Human Rights Watch about problems they encountered at all stages of the summary removal process: some said that US border officials ignored their expressions of fear and removed them with no opportunity to have their claims examined; others said border officials acknowledged hearing their expressions of fear but pressured them to abandon their claims. For those who were referred for “credible fear” interviews, some said they were intimidated and confused by the interview process and complex immigration court asylum proceedings that they had to navigate on their own while detained and without legal assistance.

When immigration officials place potential asylum seekers from Honduras and other Central American countries in summary removal without putting them into the “credible fear” process, the migrants have no opportunity to have an asylum officer or immigration judge consider their case. US immigration courts are badly backlogged, but many migrants apprehended in the interior of the country – and thus not subject to Customs and Border Protection custody – are able to present their defenses against removal from the United States, including any claims to asylum, before a decision-maker who can make a more thorough examination of their claims.

Things are different at the border. Research by Human Rights Watch and others show that the CBP’s methods for interviewing migrants in expedited removal procedures are seriously flawed. Unlike “credible or reasonable fear” assessments, which usually last over 45 minutes and take place at least 48 hours after a migrant is in ICE custody, Border Patrol screening interviews occur in Border Patrol stations and are much shorter. Uniformed CBP officers are usually armed while apprehending migrants; when they interview the migrants a few hours or days later their holsters are empty but visible; they often conduct interviews in crowded settings, without confidentiality from family members or others. All of these factors appear to hamper the ability of officers to identify those in need of more in-depth screening. The migrants we interviewed said that the CBP officers whom they encountered seemed singularly focused on removing them from the United States, which impeded their ability to make their fears known.

One man who was deported in September 2014 told Human Rights Watch that when he informed a Border Patrol officer of the threats to his life in Honduras, “He told me there was nothing I could do and I didn’t have a case so there was no reason to dispute the deportation…. I told him he was violating my right to life and he said, ‘You don’t have rights here.’”

Arriving migrants in expedited removal or reinstatement of removal are subject to mandatory detention under US law. In recent years, this has meant US immigration officials have exercised their discretion not to use these accelerated procedures for most arriving families with children, which would mean they would be mandatorily detained, opting instead to place families in removal proceedings before immigration judges. In 2009, facing lawsuits and under pressure from rights organizations, the Obama administration ended family detention at the T. Don Hutto Detention Center, which had 490 beds for the detention of migrant families with children. Since it was one of two migrant facilities in the country equipped to detain families with children (the other, in Berks, Pennsylvania, has 85 beds), this decision indicated an intention to drastically reduce the practice of detaining families.

Since that time, however, the US government has reversed its plans. In June 2014, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) established two detention facilities in Artesia, New Mexico, and Karnes, Texas, with between 500 and 700 beds each to hold arriving families. In September 2014, DHS announced plans to contract with a private prison company, the Corrections Corporation of America, to build a 2,400-bed family detention facility in Dilley, Texas. The facilities now in operation have been used to detain families primarily from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador who are in the process of expedited removal.

International law prohibits the detention of migrant children and discourages the detention of asylum seekers. Detention interferes with individuals’ ability to assert claims to asylum, access counsel, and harms the physical and mental health of children as they struggle with life behind bars and the uncertainties of indefinite detention. These policies also contravene international standards against the use of immigration detention to deter asylum seekers.

Human Rights Watch urges the Obama administration and the Congress to immediately address US border policies that are risking the lives of Central American migrants. They should cease fast-tracking Central American migrants for deportation to ensure migrants have an adequate opportunity to make a claim for asylum. If fast-tracking continues, the US should take immediate measures to ensure all migrants who express fear are being flagged for further screening. The administration should also reverse its decision to expand the detention of migrant families, evidenced by the creation of two new family detention facilities in June and July and plans announced in September to build a 2,400-bed facility in Dilley, Texas. Finally, the government should increase migrants’ access to legal counsel, which would improve handling of asylum claims and better ensure the US does not return people to countries where they face persecution or torture.

Methodology

This report is based largely on interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch from September 4 to 12, 2014 in three cities in Honduras—San Pedro Sula, Comayagua, and Tegucigalpa—as well as interviews in July and September 2014 in family detention facilities in Artesia, New Mexico, and Karnes, Texas. We also interviewed officials at Border Patrol facilities in McAllen, Texas in July 2014. Human Rights Watch interviewed 25 Hondurans who were recently deported from the United States, 10 Central American detainees in family detention centers, and one in an adult detention center in the United States. We also interviewed migrant services providers, lawyers, academics, and government officials in Honduras and in the United States.

Human Rights Watch carried out interviews in English or in Spanish, depending on the preference of the interviewee, without interpreters. We informed the interviewees of the purpose of our research and did not pay them or offer them other incentives to speak with us. In some cases in the report, we have used pseudonyms and withheld other identifying information to protect interviewees and their families from possible retaliation.

The report also contains quantitative analysis of data acquired from CBP via US Freedom of Information Act requests. The data contains information on all CBP apprehensions through fiscal years 2011 and 2012 (more than 683,000 apprehensions). Analysis is focused on descriptive statistics of the nationality and disposition variables.

I. Background on Threats in Honduras

Honduras suffers from rampant crime and impunity for human rights abuses. The murder rate, which has risen consistently over the last decade, was the highest in the world in 2013.[4]For young adult males between the ages of 20 and 34, the murder rate in Honduras exceeds 300 per 100,000.[5]

Violence in Honduras is largely the result of conflict over control of drug trafficking routes and turf wars between criminal groups,[6] although, as in many other countries, these groups target other people in their communities as well. Local street gangs, the key drivers of violence, are primarily affiliated with transnational gangs such as the Mara Salvatrucha (or MS-13) or Barrio 18 (also known as Calle 18, La 18 or Mara-18).[7] Both groups exert influence over entire neighborhoods, profiting economically by levying an impuesto de guerra or “war tax” on residents and local business people.[8] Failure to pay this “tax” can result in violent retaliation by gangs.[9]

Witnesses to gang-related crimes in Honduras fear retaliatory violence, whether or not they speak out about what they have seen.[10] “Here in Honduras, you can’t make a complaint, because then the gang comes and finishes your family,” said one man who survived a near-fatal attack by a gang member.[11]

Gang death threats may follow a person wherever they go within the country. As Central American gang expert Thomas Boerman puts it, “if you go to a new community everyone recognizes you as a stranger including the police officers and the gang members. It takes only a little bit of time for anyone looking for you to find you.”[12]

Young people are often targeted by gangs for recruitment and to carry out crime.[13] Gangs typically recruit poor, homeless, or marginalized youth, sometimes putting them through initiation rituals involving violent acts. Membership is seen as a life-long commitment and desertion is severely punished. One father, speaking of his 10-year-old son, told Human Rights Watch, “I’m scared for him. They already start making them do things at 10.”[14]

Girls may also be targeted by gangs for forced recruitment or sexual harassment and abuse.[15] Cecilia N., a 14-year-old girl who was deported from the US with her mother, said, “I’m terrified because they have taken girls from my school and raped them.”[16] After her visit to Honduras in July 2014, the United Nations special rapporteur on violence against women noted that violent deaths among women had increased by 263 percent between 2005 and 2013 and that reports indicated a 95 percent rate of impunity for femicide and sexual violence crimes.[17]

Bias-motivated attacks on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people are also a serious problem. The alleged involvement of Honduran police in some of these violent crimes is of particular concern. In 2011 and 2012, the government established special prosecutors’ units to investigate these crimes, yet there is no evidence that these efforts have resulted in a significant increase in prosecutions.[18]

Perpetrators of killings and other violent crimes in Honduras are rarely brought to justice. The institutions responsible for providing public security continue to be largely effectual and are marred by corruption and abuse, while efforts to reform them have made little progress.[19] Criminal groups have reportedly deeply penetrated the Honduran national police, demanding bribes and passing information to criminal groups.[20]

II. First-Hand Accounts: Threats Facing Returned Hondurans

Hondurans interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had been recently deported from the United States said they were subject to specific threats that, if true, would make them eligible for asylum in the United States. Many described threats from gangs in Honduras. Some of these threats arose from the common practice of gangs demanding extortion payments from small business owners. Others were victims or witnesses to crimes such as murder and rape and targeted on that basis. One said that he feared the forced recruitment of his young son into a gang. Others faced dangers from other sources, including abusive domestic partners. Nearly all said they had no meaningful protection from such violence in Honduras.

Some said their fear was so acute that they were afraid to go out in public after they were deported to Honduras.[21] One 27-year-old man told Human Rights Watch he could not leave his sister’s house nor tell his four young children that he was back in the country for fear of being found by gangs. He described leaving the house only rarely and, even then, only when wearing a motorcycle helmet with a darkened visor.[22] A deported woman described moving from house to house among her relatives every few days for fear of retaliation by the gang that she had witnessed murder her mother.[23]Almost everyone suffering these kinds of threats told Human Rights Watch that they planned to try to flee the country again as soon as possible.

Mateo S., who was deported from the United States to Honduras on September 9, 2014, told Human Rights Watch:

It’s run by a gang where I live. I can’t say the name, because it wouldn’t be safe, but they are in charge…. I had my own business here in my city. I sold bleach and other cleaning supplies from house to house. At some point, the gang started to ask me for money. Here, they call it a “war tax.” Eventually, they were asking me for about US$300 dollars a month, which is the same thing here as the minimum wage. It was impossible for me. They saw that I couldn’t pay this money so they started to mess with my family, with my son, who is seven years old, and with my wife. Eventually, they were threatening me all the time. I was paying them money for six to eight months, every month. And then I couldn’t pay it anymore and my business went bankrupt and then I was using our savings to pay the gang members. I had to pay because I was afraid they would do something to my family.

Then they tried to kidnap my son in June 2014. I usually come early to school to pick up my son at lunchtime. They got there maybe 10 or 20 minutes before the kids come out. I recognized them. They had already told me that something was going to happen to my son and to my wife. I didn’t hesitate. I jumped the school fence with my son. I pushed him over and then I jumped. Later in the day, the teachers told me that [the gang members] were looking for a kid of my son’s age. I didn’t send him back to school.… We had some savings from three or four years so I sent my son and my wife to the United States. Once I knew they were safe, I fled too.[24]

Mercedes R. also felt threatened because of her inability to pay “taxes” to the gangs in Honduras. She said, “I was facing threats from the gangs because I had a store that sold food. Starting in 2013, I spent a year paying them dollars and then I couldn’t anymore. I felt like I wasn’t living anymore. I mistrusted everyone. I didn’t feel safe.”[25]

People who witness murders or other crimes committed by gangs often fear for their lives. Roberto L., who was deported from the United States to Honduras in September 2014, said:

They killed my mother right in front of me. She had a small clothing shop. I was shot at the same time. This was in September 2013. I have been fleeing since, because I know they are looking for me. I have two kids here but I can’t see them because that would put them in danger. They can’t know I’m here. The assassins who are looking for me are at a national level, they will find me anywhere. I’m just going to be here for three weeks, then I’ll try again.[26]

Alicia R. explained that her witnessing her mother’s murder put her at risk from gang members:

They took my mother’s life.… The day that she died I was going to pick her up because she had some money to give me. I got there and then the criminals who killed her arrived. I witnessed everything that happened.… They were coming to kill somebody who was there and she was there too. She didn’t have any problems. The issue is that I saw it and they saw me. They were supposedly from a gang called “18” here. The people from the gangs don’t have any heart, whether with adults, children. They don’t have hearts.

We buried my mother … and then I had to leave the house we lived in because they came to look for us. I left everything. I went to my mother in law’s house and then an aunt’s house. I keep moving between these places for protection because when you get to one place or another, they find out quickly. They check. So as not to be in danger I always move, so that I’m never in the same place …I can’t rest. I can’t even work here. I’ve always lived here but now I have to stay on the move from place to place to protect myself from them and to protect the lives of my children. I don’t have any peace. I don’t want to be in this country because my life is in danger.[27]

Jacobo E., who was deported from the United States to Honduras in August 2014, said he was living in fear for his life. He told Human Rights Watch,

I’ve always worked. I’ve never been in a gang. I was baptized as a Mormon in 1994 and I have four kids with my wife. I had to flee though because my wife started an affair with a guy from “18.” … I saw the guy leaving my house one day and we had a fight. Then they told my sister that the gang was going to kill me, so I fled. Now that I’m back here again I don’t go out. I can’t. My parents are supporting me and I live with my sister…. I put on a motorcycle helmet inside the house to come here.

I can’t work. If I look for work they’ll see me. They are in charge in many places, the “18” is nearly everywhere. Being locked up like this is ugly. I think about my children all the time. I can’t contact them or tell them that I’m back in the country though. That would be dangerous.

The pervasive nature of gang violence in Honduras places random individuals under threat. Marlon J., who was deported from the United States to Honduras in August 2014, said,

I was a door-to-door salesman in a neighborhood called La Canada. One day I was passing by a corner with three guys just standing there. I wasn’t afraid because I usually walked around there. But then one of them ran at me and shot me seven times in the back. They left me for dead … I spent two months in the hospital and it took seven months to be able to walk.

When I came back to work one of my clients told me the gang was after me because that guy was going through a test. He had to kill the first person who walked by, to show he was brave. He would have to kill me now since I was supposed to be dead. I went to another part of the city, but then my brother-in-law was killed for not paying the “war tax.” That made me even more afraid.

I’m a father of two kids, two and five years old. I have a lot to live for. When they deported me from the United States they said they would put me in prison for six months if I come back. It doesn’t matter to me if I get six months, at least in Port Isabel [detention center in Texas], it’s safe. What I want is to be out of here.[28]

Returned migrants to Honduras did not feel the Honduran authorities were able or willing to protect them. As Marlon J., put it, after receiving seven gunshot wounds at the hands of a gang initiate, “Here in Honduras, you can’t file a police complaint because after that the gang comes and finishes your family. Delinquency is what governs.”[29]

Alicia R., who witnessed her mother’s murder, also felt she could not seek protection from Honduran police:

I never filed a complaint because sometimes in this country there is a lot of corruption.… Sometimes the police work together with the criminals.… If you go do something like that [lodge a complaint] sometimes that means they are going to be waiting for you outside of the police station.[30]

III. Expedited Removal, Reinstatement of Removal, and Screening for Credible Fear

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that “[e]veryone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.”[31] In the past two decades, US laws and practices have increasingly narrowed that right.

In 1996, as part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), the US Congress enacted a new provision called “expedited removal.” It allows the summary expulsion of noncitizens who have not been admitted or paroled into the US, who have been in the US for less than two years, and who present fraudulent documents or have no documents. Unless they express a fear of persecution or torture upon return to their home countries or indicate an intention to apply for asylum, they may be deported immediately and will be barred from returning to the US for at least five years, and often much longer.[32]

Initially, the US government applied expedited removal provisions only to noncitizens arriving at official entry points along the border or at airports known as “ports of entry.” Over the last decade, however, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which was established in 2002 after the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States, has applied expedited removal procedures to people apprehended along the entire US border. Under DHS regulations this includes people apprehended within 100 miles of the border.[33]

For asylum seekers—those in need of protection from forced return—the IIRIRA created another hurdle, called reinstatement of removal. If an individual is removed or voluntarily leaves under an order of removal, and subsequently reenters the United States illegally, they face the reinstatement of the previous order.[34] A border crosser whose order has been reinstated is barred from applying for asylum but may access other remedies such as withholding of removal or protection from return to torture under the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (“Convention against Torture”), to which the US is a party.[35]

Many individuals crossing the border first discuss their cases with a Customs and Border Protection agent who, under US law, is supposed to inform them that they may ask for protection if they have a fear of returning home. If a fear of return is expressed, the agent should flag them for a more thorough assessment known as a “credible fear” interview.[36] Research by Human Rights Watch and others show that the CBP’s methods for interviewing migrants in expedited removal procedures are seriously flawed.[37]

A primary finding of Human Rights Watch’s investigation in Honduras is that individuals seeking asylum are not being flagged for credible fear interviews by CBP officers. This is supported by US government data. Between October 2010 and September 2012, the vast majority of Hondurans, 81 percent, were placed in the fast-track expedited removal and reinstatement of removal proceedings; only a miniscule minority, 1.9 percent, were flagged for credible fear assessments by CBP.[38]

The data also show low rates of credible fear referrals by CBP for nationals of Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Only 0.1 percent of Mexicans, 0.8 percent of Guatemalans, and 5.5 percent of Salvadorans in expedited or reinstatement of removal were referred to a credible or reasonable fear interview by CBP. However, 21 percent of migrants from countries other than these, who underwent the same proceedings in the same years, were flagged for credible fear interviews by CBP. On October 9, 2014, Human Rights Watch requested updated apprehension data from CBP, which could shed light on the trends in CBP credible fear referral rates during the 2013 and 2014 influx of migrant adults, families and children from Central America.

As discussed above, those unauthorized migrants who are flagged for having a fear of return, proceed to a pre-asylum screening to determine whether there is a significant possibility that they can establish persecution or fear of persecution before an immigration judge.[39]

In recent years, migrants from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador have formed an increasing proportion of the credible fear referrals received by USCIS.[40] Absolute numbers of Central Americans identified for credible or reasonable fear screening have also been increasing. Referrals of Hondurans, for instance, have increased from 1,108 individuals in 2006 to 8,539 in 2013.[41]

Most of these referrals, however, do not come from CBP, despite CBP’s proactive duty to screen migrants it places in expedited or reinstatement of removal for fear of return to their country of origin. In 2012, for example, CBP referred only 615 of the 2,405 Hondurans who eventually received credible fear interviews.[42] Approximately three-quarters of the credible fear referrals USCIS conducted in 2012 came from agencies other than the CBP, even though that year CBP was responsible for approximately 57 percent of all noncitizen apprehensions.[43]

A migrant may be referred by an immigration official after they have left CBP custody and entered the custody of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the agency responsible for more prolonged detention of migrants. ICE, however, does not have a duty to proactively screen all migrants in its custody for their fear of return. The majority of credible and reasonable fear referrals that USCIS received in 2011 and 2012 did not come from CBP but other immigration agencies, which learn of migrants’ fear of return on an ad-hoc basis.

For those who are referred to credible fear interviews, the likelihood of being permitted to apply for asylum appears to have fallen significantly in recent months. This comes in the wake of problematic new guidance for asylum officers conducting interviews (referred to as the “lesson plan”) issued in February 2014.[44] Before the lesson plan was enacted, in January 2014, 83 percent of those who received credible fear interviews were permitted to apply for asylum. In July 2014, six months later, that figure was 63 percent.[45] While this could be an artifact of a larger number of credible fear referrals or a smaller sample size of the months since the plan, this evidence suggests that the lesson plan has reduced the proportion of interviews in which credible fear is found. The precipitous apparent decline occurred in the period after the release of the new lesson plan, and not in tandem with the rise in referrals. Asylum law experts have criticized the lesson plan for inappropriately raising the burden of proof required at the credible or reasonable fear stage.[46]

If a noncitizen is found to have a credible fear, they may then apply for asylum as a defense against deportation in immigration court. Though the asylum seeker will be able to go before a judge to make their claim for protection, they have no right to a government-appointed lawyer to assist them. ICE may detain noncitizens going through these immigration court procedures for the duration of the deportation process on a discretionary basis, though some become eligible for release on bond or on their own recognizance once they are transferred to immigration court.

IV. First-Hand Accounts: Asylum Seekers’ Experiences in Expedited Removal

US Customs and Border Protection officers are required to screen people in expedited removal for fear of return to their country and, if the noncitizen expresses fear, refer them for a credible fear interview.[47] Despite this requirement, Human Rights Watch spoke with deportees who reported that they were not informed of the availability of protection or that they were not referred to an asylum officer for a credible fear interview after they told a Border Patrol agent they were afraid to return to their country.[48] Some would-be asylum seekers also reported that Border Patrol officers harassed, threatened, and attempted to dissuade them from applying for asylum.

Additionally, CBP officers conduct interviews about fear of return in a sometimes crowded and public enforcement setting and without confidentiality from family members or others, factors that appear to hamper the ability of the officers to identify those in need of more in-depth screening. Human Rights Watch observed the interview location for detainees at the McAllen Border Patrol station in Texas in July 2014. CBP officers showed Human Rights Watch a large public space in which they process migrants at a horseshoe-shaped table designed to accommodate multiple officer-migrant pairs in close proximity. Holding cells ring the room, with concrete floors and walls and toilets behind half-high barriers. CBP officers told and demonstrated to Human Rights Watch how they check their weapons before entering, but wear their uniform with holsters – which can be particularly intimidating to persons fearful of the security forces in their home countries.[49] CBP officers told Human Rights Watch that the McAllen Border Patrol station was physically similar to many other such stations along the Mexican border.

Migrants who were not referred for a credible fear interview told Human Rights Watch that interviews by CBP are brief and focused on explaining additional consequences of deportation, such as bars to return for set periods of time, rather than exploring their fear of return. “The officers don’t pay attention to you. If you say you are afraid they say they ‘can’t do anything,” Marlon J. told Human Rights Watch. “All they said to me was that if I came back they would give me six months in prison.”[50]

Some Border Patrol officers apparently tried to convince border crossers not to apply for asylum. “I asked for asylum,” said Jacobo E., who fled after being shot and seeing his mother killed for her failure to pay fees to gang members to run her small clothing business. “The officer told me don’t apply, 90 percent of the people who do don’t get it.”[51] Some deportees and detainees with whom we spoke reported that they resisted signing forms offered by Border Patrol, or were coerced into signing something they did not understand. “‘Fingerprint, fingerprint,’ they just kept saying, I didn’t know what I was signing,” said Jacobo E. who was in hiding in Honduras after being deported.[52] Maribel V., who was deported from the Artesia, New Mexico family detention center with her children, said:

They made me sign the deportation in the “icebox” [slang for the cold Border Patrol detention cells]. No judge or lawyer spoke with me. They called me and they said that I had to sign this paper. They told me that it was for a judge to see my case. But I never saw a judge and they told me I had a deportation order. They told me I was already deported.[53]

Mateo S., who had fled death threats from a gang, said he tried to not sign papers agreeing to his deportation:

I was detained for six days in the cold rooms. They just asked me my name, where I came from, and they told me I was punished for five years and I had to sign the deportation. I didn’t want to sign. When the moment of the interview came I said I wouldn’t sign. The officer insulted me. They started waking me up every couple of hours and moving me from cell to cell. It was hard…. The officer filled out all the paperwork and told me to sign, I told him I wouldn’t sign and I hoped the US government would admit me. He ripped up all the paper and threw it almost at my face. He told me I was deported anyway. He said he “had the law in his hand and he was going to sign for me.” I told him he was violating my right to life and he said, “You don’t have rights here.”[54]

Alicia R., an asylum seeker who crossed the border with her two children, 3 and 10 years old, told officers of her fear of returning to Honduras. In an attempt at self-preservation, thinking it would keep her from being deported to Honduras, she also told them she was from Mexico:

The truth is because I didn’t want to come back here [to Honduras], I told them that I was from Mexico. I told them, I cried, I said I couldn’t return to my country. Sometimes you are so afraid … to be sent back so you just say something.[55]

After two days, US officials turned Alicia and her children over to the Mexican government, which deported them two weeks later back to Honduras.[56]

Some migrants told Human Rights Watch that when they tried to tell US officials about their fear of returning, they were denied further exploration of that claim, and were put in touch with consular officers from their country of origin. This practice runs counter to international protection standards, which recognize the problematic relationship asylum seekers may have with officials from their home countries. “The [US] officers don’t speak with you. They just set it up so you can speak with a consular officer and then so you sign the papers,” said Marlon J.[57]

In some cases, migrants reported that consular officers dissuaded them from making international protection claims. Mateo S. explained,

They put me in touch with someone who they said was the consul of Honduras on a video screen. I explained to him in total confidence that I was fleeing my country and the threats I was facing. He told me I didn’t have a case, so why try?[58]

V. Detention and Access to Counsel

None of the asylum seekers Human Rights Watch met with who had been deported to Honduras had had lawyers while in the United States, though several had tried to obtain them. While many asylum seekers without financial resources have difficulty obtaining legal counsel in the US, it is particularly difficult for those who are placed in detention facilities near the border and put in expedited proceedings.

Detention of noncitizens in expedited removal proceedings and reinstatement of removal is mandatory under US law.[59] Because nearly all arriving Central Americans without authorization are placed in expedited removal proceedings, the vast majority are also detained prior to deportation.

Detention adds to the burdens and fears asylum seekers face. The fact that it is administrative rather than criminal detention may be of little practical consequence. Several told Human Rights Watch how being detained weighed on them. “I didn’t have any idea what a prison was,” said Jacobo E. “They just treated me like a criminal.”[60]

Detention also makes it more difficult for asylum seekers to gather evidence that might be useful in their cases. Roberto L. was detained for six months while he attempted to apply for asylum on the basis of threats and past harm. “They said I needed proof,” he said. “But they said you have to be detained for [an additional] six months [to keep applying for asylum], so I signed the deportation.”[61]

Detainees also face considerable obstacles in obtaining legal counsel, a challenge made more difficult when they are held in detention facilities. “I need to find a lawyer but it seems impossible,” one woman from Honduras then detained in Artesia, New Mexico told Human Rights Watch. “I will die if I am sent back to my country.”[62] Maria F. was deported in September after being detained at Karnes family detention center with her 8-year-old daughter. “They give you a paper with [the names of] free lawyers. But nobody answers when you call.”[63]

One legal service provider in San Francisco agreed that detained migrants had difficulty locating legal counsel:

We get many calls from people whose family members are in detention, including in Texas. Usually we get the call after they’ve called multiple other organizations or lawyers. The few legal service providers who have called them back charge very high fees. There’s just a very high demand and not enough supply. We never get initial calls from detainees themselves. They need to have someone on the outside who can help them find a lawyer and even then it’s very difficult.[64]

In 2005, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), a government agency, found that the expedited removal process lacks adequate safeguards to prevent improper removal and extended detention of bona fide refugees in the United States.[65] USCIRF’s analysis also found that asylum seekers in expedited removal who are represented by an attorney were granted relief 25 percent of the time, while asylum seekers who were representing themselves were granted relief 2 percent of the time.[66] Robert A. Katzmann, a judge of the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, summed up the results of a two-year study on immigrant representation in New York: “The two most important variables affecting the ability to secure a successful outcome in a case (defined as relief or termination) are having representation and being free from detention.”[67]

Human Rights Watch has previously documented how detaining noncitizens, sometimes far from family members and friends, affects their access to counsel.[68] The Executive Office for Immigration Review recently reported that the percentage of represented cases in immigration court has increased in the past five years from 35 percent in 2009 to 59 percent in 2014.[69] Yet there is a large gap between representation rates for detained versus non-detained immigrants in immigration court proceedings. The New York Immigrant Representation Study found in 2011 that 40 percent of detained immigrants and 73 percent of non-detained immigrants in the New York City area had lawyers.[70]

Things are even worse for migrants detained in south Texas, like most of those interviewed for this report. Texas Appleseed, a non-profit legal services organization, found 86 percent of immigration detainees in Texas were unrepresented in 2009.[71] Several more recent reports indicate that systematic problems with detainees’ access to counsel have not been resolved.[72] The American Immigration Council and Penn State Law found in 2012 that,

ICE fails to provide or facilitate access to counsel when questioning represented individuals, restricts attorney-client communications in detention facilities, and has also discouraged noncitizens from seeking legal counsel.[73]

Dani A., one of the few individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had passed the credible fear interview stage, ended up deported to Honduras apparently due to her inability to secure counsel while in detention. At 21, Dani had been in an abusive relationship for four years in which her husband regularly beat her and kicked her. Two years ago, her husband’s cousin ambushed her in a deserted part of town and raped her. She went to the police to report the rape, but “nothing was resolved.”[74] Not knowing she had made a complaint, the cousin told her that if she told anyone about the attack he would kill her. She feared the cousin would harm her again and that her husband would seek her out and harm her.

After entering the United States and being identified by CBP for further screening, Dani spoke with an asylum officer who found that there was “a significant possibility” she could establish in a full hearing that she would qualify for refugee status.[75] A recent decision by the Board of Immigration Appeals recognizes domestic violence as a basis for asylum, establishing a formally binding precedent upholding earlier immigration court rulings.[76]

Detained in Houston, Texas, with only three years of formal schooling and no money to pay a lawyer, Dani tried to move forward with her asylum claim. Gender-based asylum claims, including those related to domestic violence like Dani experienced, are particularly legally complex. Officials gave her a list of free legal services providers in the area but she said, “They never answered my calls.” With the help of other detainees who spoke more English, she filled out the application for asylum or withholding of removal. To the question “Are you afraid of being subjected to torture in your home country or any other country to which you may be removed?,” Dani’s asylum application read, “Am afraid to go back to abusers. Nature of turture: sexual assault and beat to death.” [sic] Where the form asked if she feared harm or mistreatment if she returned to her home country the form stated: “1) Kill by gang husband gang members 2) Husband and husband gang members 3) because I am running away from my husband, he can kill me and sexsually asult.” [sic]

These two responses formed the substance of Dani’s asylum application. She told Human Rights Watch that the judge in charge of her case ordered her deported at the first hearing after she filed the application. “I wanted to get a lawyer,” she said. “I didn’t have one.”

Family detention presents particular due process problems. In its guidelines on international protection for child asylum claims, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the UN refugee agency, recommends separate and confidential interviews for all family members to give each an opportunity to discuss any independent claims for protection.[77] UNHCR has also found that a lack of confidentiality could hinder the ability of women to fully access asylum procedures and recommended that “a confidential personal interview, that is gender and culturally sensitive, should be guaranteed in the asylum process, to help ensure access.”[78]

Officials at the Artesia, New Mexico, family detention center told Human Rights Watch in July 2014 that credible fear interviews were being conducted with female detainees in the presence of their children. The children’s presence may have inhibited women from speaking frankly, interfering with their ability to make their claim, and may further traumatize both the mother and her children.

Noemi M., who was detained while awaiting an asylum interview, told Human Rights Watch that she would only speak about the death threats she received from gangs in Honduras when her 8- and 11-year-old children were out of earshot.[79] DHS officials have since told Human Rights Watch that women in Artesia are being interviewed by asylum officers separately from their children.[80]

Once a noncitizen in expedited removal has passed a credible fear interview, detention is no longer legally mandated but at the discretion of immigration officials. US officials in Artesia told Human Rights Watch that women and children who file for asylum in immigration court could be detained throughout the entire process, which can last months or even years. Immigration attorneys report that ICE is opposing bond requests from women and children in family detention, arguing that the families pose national security threats.[81] Such prolonged detention, with no defined end date, can cause serious psychological harm, especially for children, including anxiety, depression, and long-term cognitive damage.[82] Marleen V. from El Salvador, who had been detained with her 2-year-old daughter for two weeks at the time she spoke with Human Rights Watch, said of her daughter, “I notice her losing weight. She just won’t eat.”[83]

VI. US Law and International Refugee Law

The United States committed to the central guarantees of the 1951 Refugee Convention by its accession to the Refugee Convention’s 1967 Protocol.[84] The US government passed the Refugee Act of 1980 in order to bring the country’s laws into compliance with the Refugee Convention and Protocol, by incorporating into US law the convention’s definition of a “refugee” and the principle of nonrefoulement, which prohibits the return of refugees to countries where they would face persecution.[85]

The US, as a party to the Convention against Torture, is also obligated not to return someone to a country “where there are substantial grounds for believing that [they] would be in danger of being subjected to torture.”[86]

As described above, Human Rights Watch is concerned that the US system of expedited removal and reinstatement of removal fails to ensure that the US complies with these international legal obligations, and defeats other mechanisms already in place in US law (specifically the asylum process in US immigration courts) to ensure that asylum seekers are identified and have a fair process through which to present their claims.

In particular, the Hondurans interviewed for this report described rushed interviews and unsympathetic reactions from CBP officials that run contrary to international standards on appropriate procedures for the determination of refugee status. The UNHCR’s authoritative Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status (“UNHCR Handbook”), states,

It should be recalled that an applicant for refugee status is normally in a particularly vulnerable situation. He finds himself in an alien environment and may experience serious difficulties, technical and psychological, in submitting his case to the authorities of a foreign country.[87]

CBP’s role in the process—involving the same uniformed and armed agents responsible for apprehending migrants that screen them for fear of return—conflicts with additional guidance from the UNHCR Handbook:

A person who, because of his experiences, was in fear of the authorities in his own country may still feel apprehensive vis-à-vis any authority. He may therefore be afraid to speak freely and give a full and accurate account of his case.[88]

The rapid-fire nature of the expedited removal process, in particular the role played by CBP at the outset, is at odds with the recognition by UNHCR’s Executive Committee (“Excom”) that expedited procedures may be fair only when applied to cases that are “clearly fraudulent or not related to the criteria for the granting of refugee status laid down in the [1951 Refugee Convention].”[89]

Human Rights Watch is also concerned that interviews of Honduran asylum seekers by Honduran consular officials do not meet international standards. The UNHCR Handbook states that, by definition, a refugee’s relationship with their country of origin may be severely strained. The Handbook also states that, “it is, of course, of the utmost importance that the applicant’s statements will be treated as confidential.” In all cases in which a migrant has expressed a fear of returning home to US border or immigration officials, it is a serious breach of confidentiality to encourage and facilitate meetings between an asylum seeker and an official of the asylum seeker’s home government. US immigration officials, first, should take all reasonable measures to determine whether a migrant is an asylum seeker, and, second, should preserve confidentiality, which includes insulating them from home government officials while their claims are pending.

Detention of asylum seekers should always be a measure of last resort and should only be for reasons clearly recognized in international law, such as concerns about danger to the public, or an inability to confirm an individual’s identity.

Expanding family detention is inconsistent with international standards, particularly the fundamental principle—reflected in both international and US law—that “best interest of the child” should govern the state’s actions toward children.[90] If detention of children is used at all, it should only be in rare and exceptional cases, and for the shortest amount of time and in an appropriate setting where the children’s needs can be addressed without causing further trauma or harm.[91] Deprivation of liberty has a negative effect on children’s capacity to realize various fundamental rights, including the rights to education, health, and family unity.79

Previously, the US government made greater use of alternatives to detention for families, such as proven “appearance support” programs that ensure migrants in immigration proceedings understand how and when to appear.[92]

Finally, using detention explicitly as a deterrent to entry into the United States for people seeking international protection is unlawful under international law[93] and US law.[94] However, the Obama administration has openly stated that one purpose for the increase in family detention beds is to deter all unauthorized migrants from entering the country. DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson has referred to detention as part of an “aggressive deterrence strategy” in Senate testimony and has told the media that he believed detention “would deter future illegal crossings.”[95] The ICE Assistant Director of Investigative Programs for Homeland Security Investigations has stated that “[i]mplementing a ‘no bond’ or ‘high bond’ policy would help alleviate these disruptions by deterring further mass migration.”[96] The ICE press release announcing the Dilley, Texas family detention facility stated: “These facilities will help ensure more timely and effective removals that comply with our legal and international obligations, while deterring others from taking the dangerous journey and illegally crossing into the United States.”[97]

As we were finalizing this report, the Obama administration on September 30, 2014 announced a targeted program to process from inside their home countries children with lawfully present parents in the United States for admission to the United States as refugees.[98] The program, according to administration officials, would provide a safe alternative to the dangerous journey to the United States through Mexico for those children who would qualify to be reunited with a lawfully present parent.

While this program could potentially assist the relatively small group of children who would qualify, it would do nothing to address the protection needs of the vast majority of children and adults who do not have a lawfully present parent in the United States or who did have such a parent but who would be too afraid to wait for months or years to be processed after being threatened by a gang. The existence of this program should not be used as an excuse for continuing or even expanding the harsh measures already in place at the border—and in Mexico—to block Central Americans from seeking asylum and to summarily return them to places where they face a serious risk of harm.

Whatever policies the Obama administration seeks to put in place to deter unauthorized migration, it needs to preserve the right to seek asylum from persecution. The US government should ensure that it does not deport people crossing the US-Mexico border without proper consideration of their need for international protection.

Recommendations

The recommendations below apply to US treatment of unauthorized migrants not only from Honduras, the research focus of this report, but from similarly situated countries where large numbers of migrants and asylum seekers are fleeing violence by non-state actors and conditions that prevent that country’s nationals from returning to a situation of basic security, notably Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

To ensure that migrants arriving at the US-Mexico border who express fear of return to their countries are flagged for screening that would permit them to access refugee protection or protection under the Convention Against Torture:

The Department of Homeland Security should:

- Cease the use of expedited removal for individuals and families arriving at the US border with Mexico from countries experiencing conditions that prevent the country’s nationals from returning to a situation of basic security;

- Ensure via training; modification of oversight mechanisms; accountability measures, including better quality assurance supervision; and any and all other appropriate measures that initial interviews of arriving noncitizens conducted by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) properly identify individuals who express fear of return so that they are afforded “credible” or “reasonable” fear assessments;

- Until that time, instruct CBP to apply a presumption of fear of return for migrants in expedited removal or reinstatement of removal who are nationals of countries experiencing conditions that prevent the country's nationals from returning to a situation of basic security; and

- Unless and until Department of Homeland Security (DHS) can implement appropriate protection interviews as a part of expedited removal or it instructs CBP to adopt a presumption for asylum screening for Central Americans, instruct Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to conduct a proactive screening for fear of return for every non-citizen arriving in its custody from CBP custody.

To ensure that credible and reasonable fear interviews are fair and efficient:

The Department of Homeland Security should:

- Ensure that United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) has adequate staffing levels, training, and supervision; and

- Review guidance for USCIS staff to ensure that the procedures used in “credible fear” interviews do not unduly bar asylum seekers from access to immigration courts.

Congress should:

- Adopt legislation that would allow the USCIS to conduct timely in-person “credible fear” and “reasonable fear” screening interviews and address backlogs, without creating delays for affirmative asylum interviews;

- Adopt legislation to address removal-hearing delays, eliminate backlogs and conduct prompt hearings, including by increasing the number of immigration court judges, law clerks, government immigration lawyers and related resources, as well as increasing incentives for legal aid and private lawyers to represent migrants in underserved areas.

To protect children and adults from the harmful effects of detention and ensure the due process rights of asylum seekers:

The Department of Homeland Security should:

- Revert to previous US government policy that limited the detention of arriving migrant families with children. This would entail closing the new family detention center in Artesia, New Mexico, reverting the family detention center in Karnes, Texas back to a civil detention facility for adults, and converting plans to build a 2,400-bed facility in Dilley, Texas from family detention to adult civil detention. DHS should augment alternative custody and monitoring programs that ensure court appearances instead of detention for families and other border arrivals who present no danger or need assistance to appear in court; and

- Apply a presumption in favor of release on bond or parole for asylum seekers who have passed credible or reasonable fear screenings.

To respect asylum seekers’ right to access counsel, improve disposition of asylum claims, and better ensure that the US does not return people to countries where they face repression or torture:

The administration and Congress should:

- Approve reallocation of already appropriated funds to increase access to counsel for indigent asylum seekers and those requesting protection under the Convention Against Torture;

- Consider passing a law concerning asylum seekers akin to the provision in the Senate Border Security, Economic Opportunity and Immigration Modernization Act (S.744) of 2013 that mandates the US attorney general to appoint counsel, at government expense if necessary, for unaccompanied minors, people with mental disabilities, and other non-citizens “considered particularly vulnerable;” and

- Consider passing legislation to allow immigration judges the discretion to appoint counsel for indigent non-citizens in all standard immigration removal proceedings.

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Clara Long, US Program researcher on immigration and border policy at Human Rights Watch. Antonio Ginatta, advocacy director for the US program, conducted interviews in the Karnes family detention facility. Brian Root, quantitative analyst at Human Rights Watch, conducted data analysis.

Alison Parker, US program director, edited and contributed to research and writing of the report. The report was also edited by Bill Frelick, refugee rights director; José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director; Meghan Rhoad, women’s rights researcher; and Alice Farmer, child rights researcher. Samantha Reiser and W. Paul Smith, associates in the US Program, also contributed to editing. James Ross, legal and policy director, provided legal review. Joe Saunders, deputy program director, provided program review. Grace Choi, publications director, provided photo editing and layout design.

Human Rights Watch thanks the government officials, lawyers, social service providers and others who spoke with us during the research for this report. We are especially grateful to the Central American migrants and asylum seekers whose participation in this research made this report possible.

[1] Human Rights Watch interview with Alicia R. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 8, 2014. The names of migrants quoted in this report have been changed in the interest of the security of those concerned.

[2] Ana Campoy, “Illegal Immigrants Seeking Asylum Face a Higher Bar,” Wall Street Journal, September 28, 2014, http://online.wsj.com/articles/illegal-immigrants-seeking-asylum-face-a-higher-bar-1411945370 (accessed October 9, 2014).

[3] Some noncitizens, apprehended in the interior of the country and placed in reinstatement of removal by ICE, may not pass through CBP custody and should be screened by ICE for fear of return.

[4] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), “Global Study on Homicide 2013: Trends, Contexts, Data,” April 2014, http://www.unodc.org/gsh/ (accessed October 9, 2014).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7]Ibid.

[8]“Miles de reclutas de las maras cobran el ‘impuesto de guerra’,” La Tribuna, March 12, 2013, http://www.latribuna.hn/2013/03/12/miles-de-reclutas-de-las-maras-cobran-el-impuesto-de-guerra/ (accessed October 9, 2014).

[9] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Guidance Note on Refugee Claims Relating to Victims of Organized Gangs,” March 31, 2010, http://www.refworld.org/docid/4bb21fa02.html (accessed October 13, 2014); Human Rights Watch interview with Marlon J. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 6, 2014.

[10] Nicholas Phillips, “In Honduras, Going From Door to Door to Prosecutors,” New York Times, March 4, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/04/world/americas/in-honduras-going-from-door-to-door-to-prosecutors.html (accessed October 9, 2014).

[11] Human Rights Watch interview with Marlon J. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 6, 2014.

[12] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Thomas Boerman, Central American Security Specialist, Eugene, Oregon, August 28, 2014.

[13] UNHCR, “Guidance Note On Refugee Claims Relating To Victims Of Organized Gangs,” March 2010, http://www.uscrirefugees.org/2010Website/5_Resources/5_4_For_Lawyers/5_4_1%20Asylum%20Research/5_4_1_2_Gang_Related_Asylum_Resources/5_4_1_2_4_Reports/UNHCR_Guidance_Note_on_Refugee_Claims.pdf (accessed October 10, 2014).

[14] Human Rights Watch interview with Jacobo E. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 7, 2014.

[15]

CIDEHUM, UNHCR, “Forced Displacement and Protection Needs Produced by New

Forms of Violence and Criminality in Central America,” May 2012, http://www.nanseninitiative.org/sites/default/files/UNHCR%20Research%20Paper%20May

%202012.pdf (accessed October 10, 2014).

[16] Human Rights Watch interview with Cecilia N. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 8, 2014. Cecilia N. and her mother, Josefa N. (pseudonym) were detained from July 28, 2014 until they were deported on September 6, 2014 at the Immigrations and Customs Enforcement family detention center in Artesia, New Mexico.

[17] Rashida Manjoo, “Special Rapporteur on violence against women finalizes country mission to Honduras and calls for urgent action to address the culture of impunity for crimes against women and girls,” July 7, 2014, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=14833&LangID=E#sthash.aEX2teov.dpuf (accessed October 13, 2014).

[18] Human Rights Watch, World Report 2014: Honduras (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2014), http://www.hrw.org/world-report/2014/country-chapters/honduras/.

[19] Ibid.

[20] InSight Crime, “Honduras,” undated, http://www.insightcrime.org/organized-crime-profile/honduras (accessed October 9, 2014).

[21] See Jorge Ramos and Daniel Lieberman, “Deported mom lives in fear after returning to Honduras,” Fusion, August 20, 2014, http://fusion.net/story/6335/deported-mom-lives-in-fear-after-returning-to-honduras/ (accessed October 13, 2014).

[22] Human Rights Watch interview with Jacobo E. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 7, 2014 (Jacobo was deported from the US in August 2014).

[23] Human Rights Watch interview with Alicia R. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 8, 2014. (Alicia told US border officials that she and her children were Mexican. She and her children were deported from the United States to Mexico and then from Mexico to Honduras in August 2014.)

[24] Human Rights Watch interview with Mateo S. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 9, 2014. (Mateo was deported to Honduras from the United States in September 2014.)

[25] Human Rights Watch interview with Mercedes R. (pseudonym), Karnes Detention Center, Texas, September 16, 2014. (Mercedes was detained at Karnes with her seven-year-old son.)

[26] Human Rights Watch interview with Roberto L. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 9, 2014. (Roberto was deported from the United States in September 2014, after being detained for six months while seeking asylum.)

[27] Human Rights Watch interview with Alicia R. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 8, 2014. (Alicia was deported from the United States to Mexico in August 2014 before being returned to her native Honduras.)

[28] Human Rights Watch interview with Marlon J. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 6, 2014. (Marlon was deported from the United States in August 2014.)

[29] Ibid.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with Alicia R. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 8, 2014.

[31] Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted December 10, 1948, G.A. res. 217A (III), U.N. Doc A/810 at 71 (1948).

[32] Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) 235(b), codified as 8 U.S.C. 1225(b) and enacted as regulation at 8 C.F.R. 235.3(b)(c); INA 241(c), codified as 8 U.S.C. §1231(c) and enacted as regulation at 8 C.F.R. 241; INA 212(a)(9)(a) and (a)(9)c)(i), codified as 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(9)a) and (a)(9)(c)(i).

[33] Designating Aliens for Expedited Removal, 69 Fed. Reg. 48877 (August 11, 2004); “DHS Streamlines Removal Process Along Entire US Border,” DHS press release, January 31, 2006, http://www.govtech.com/policy-management/Department-of-Homeland-Security-Streamlines-Removal.html (accessed October 10, 2014).

[34] INA 241(a)(5), codified as 8 U.S.C. 1231(a)(5).

[35] Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (“Convention against Torture”), G.A. Res. 39/46, annex, 39 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 51) at 197, U.N. Doc. A/39/51 (1984), entered into force June 26, 1987. The US ratified the Convention against Torture in1994 and passed enabling legislation with Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act of 1998, P.L. 105-277. The US currently implements its duties under the Convention against Torture through a process called “withholding of removal.” 8 C.F.R. 208.16. The protections granted by the United States under the Convention against Torture are narrower than the protections afforded to refugees. A higher burden of proof must be shown to establish eligibility; it provides a narrower scope of relief, such as restrictions on international travel; and there is limited opportunity for conversion to legal permanent resident status.

[36] 8 C.F.R. 235.3(b)(4) (stating that if an applicant requests asylum or expresses a fear of return, the “examining immigration officer shall record sufficient information in the sworn statement to establish and record that the alien has indicated such intention, fear, or concern,” and should then refer the alien for a credible fear interview).

[37] Human Rights First, “How to Protect Refugees and Prevent Abuse at the Border: Blueprint for U.S. Government Policy,” June 2014, http://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/Asylum-on-the-Border-final.pdf (accessed October 10, 2014); Sara Campos and Joan Friedland, “Mexican and Central American Asylum and Credible Fear Claims: Background and Context,” American Immigration Council Special Report, May 2014, http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/docs/asylum_and_credible_fear_claims_final.pdf (accessed October 10, 2014); Michele R. Pistone and John J. Hoeffner, “Rules are Made to be Broken: How the Process of Expedited Removal Fails Asylum Seekers,” Villanova University School of Law, 2006, http://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=/context/wps/article/1049/&path_info= (accessed October 14, 2014); US Commission on International Religious Freedom, “Study on Asylum Seekers in Expedited Removal,” February 2005, http://www.uscirf.gov/reports-briefs/special-reports/report-asylum-seekers-in-expedited-removal (accessed October 10, 2014).

[38] Calculated from CBP data on apprehensions provided to Human Rights Watch via a Freedom of Information Act request.

[39] INA 235.3(b)(4).

[40] In FY 2013, 65 percent of credible fear referrals and 58 percent of reasonable fear referrals were for nationals of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, combined. In 2004, nationals from these three countries represented less than 2.5 percent of referrals. Calculated from USCIS, “Credible Fear Nationality Report, 2014,” http://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Outreach/Notes%20from%20Previous%20Engagements/AdditionalStatisticRequestedApril2014AsylumStakeholderEngagement.pdf (accessed October 10, 2014).

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Calculated from Department of Homeland Security, “Immigration Actions: 2012,” Table 1, http://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ois_enforcement_ar_2012_1.pdf (accessed October 13, 2014).

[44] “Credible Fear,” Lesson Plan, Refugee, Asylum, and International Operations Directorate Officer Training; Asylum Division Officer Training Course, February 28, 2014, http://cmsny.org/wp-content/uploads/credible-fear-of-persecution-and-torture.pdf (accessed October 10, 2014).

[45] Ana Campoy, “Illegal Immigrants Seeking Asylum Face a Higher Bar,” Wall Street Journal, September 28, 2014, http://online.wsj.com/articles/illegal-immigrants-seeking-asylum-face-a-higher-bar-1411945370 (accessed October 10, 2014).

[46] Bill Ong Hing, Memorandum to John Lafferty, Chief, USCIS Asylum Division Concerning Lesson Plan, Credible Fear of Persecution and Torture Determinations, April 21, 2014, http://static.squarespace.com/static/50b1609de4b054abacd5ab6c/t/53558353e4b02071f74ee3c4/1398113107754/Re sponse%20to%20USCIS%20Credible%20Fear%20Memo,%20Bill%20Hing,%2004.21.2014.pdf (accessed October 13, 2014).

[47] 8 C.F.R. 235.3(b)(2) (“In every case in which the expedited removal provisions will be applied and before removing an alien from the United States pursuant to this section, the examining immigration officer shall create a record of the facts of the case and statements made by the alien. This shall be accomplished by means of a sworn statement using Form I-867AB, Record of Sworn Statement in Proceedings under Section 235(b)(1) of the Act. The examining immigration officer shall read (or have read) to the alien all information contained on Form I-867A. Following questioning and recording of the alien's statement regarding identity, alienage, and inadmissibility, the examining immigration officer shall record the alien's response to the questions contained on Form I-867B, and have the alien read (or have read to him or her) the statement, and the alien shall sign and initial each page of the statement and each correction.”). Form I-867A includes the provision that the immigration officer read the following statement:

U.S. law provides protection to certain persons who face persecution, harm or torture upon return to their home country. If you fear or have a concern about being removed from the United States or about being sent home, you should tell me so during this interview because you may not have another chance. You will have the opportunity to speak privately and confidentially to another officer about your fear or concern. That officer will determine if you should remain in the United States and not be removed because of that fear.

Form I-867B requires that the immigration officer ask and record the answer to the question, “Do you have any fear or concern about being returned to your home country or being removed from the United States?” Forms I-867A&B available in Appendix A of Charles Kuck, “Legal Assistance for Asylum Seekers in Expedited Removal: A Survey of Alternative Practices” Expert Report in US Commission on International Religious Freedom, “Report on Asylum Seekers in Expedited Removal,” February 8, 2005, http://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/resources/stories/pdf/asylum_seekers/legalAssist.pdf (accessed October 13, 2014).

[48] Human Rights Watch interviews, San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 6, 7, 8, and 9, 2014.

[49] Human Rights Watch visit to McAllen Border Patrol Station, McAllen, Texas, July 25, 2014.

[50] Human Rights Watch interview with Marlon J. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 6, 2014. (“Los oficiales ya a uno no le prestan atención. Si uno dice que tiene miedo dicen que no pueden hacer nada, ‘I’m sorry,’ lo siento.”)

[51] Human Rights Watch interview with Roberto L. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 9, 2014.

[52] Human Rights Watch interview with Jacobo E. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 7, 2014.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview with Maribel V. (pseudonym), Comayagua, Honduras, September 6, 2014. (Maribel was deported with her children in September 2104. “Ice box” or hielera is how migrants commonly refer to Border Patrol detention, in reference to the cold temperatures in the cells.)

[54] Human Rights Watch interview with Mateo S. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 9, 2014. (Mateo was deported to Honduras from the United States in September 2014.) Immigration attorneys have reported hearing from other migrants of similar treatment in the McAllen Border Patrol station. Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Carlos Garcia, Immigration Attorney in McAllen, Texas and Rex Chen, Immigration attorney at Catholic Charities of Newark, September 9, 2014.

[55] Human Rights Watch interview with Alicia R. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 8, 2014.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Human Rights Watch interview with Marlon J. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 6, 2014.

[58] Human Rights Watch interview with Mateo S. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 9, 2014.

[59] INA 235(b)(1)(b)(iii)(iv) (“Any alien subject to the procedures under this clause shall be detained pending a final determination of credible fear of persecution and, if found not to have such a fear, until removed.”); 8 U.S.C. 1225(b)(1)(b)(iii)(iv). 8 U.S.C. 1231(a)(2) (“During the removal period, the Attorney General shall detain the alien.”).

[60] Human Rights Watch interview with Jacobo E. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 7, 2014.

[61] Human Rights Watch interview with Roberto L. (pseudonym), San Pedro Sula, Honduras, September 9, 2014.

[62]Human Rights Watch Interview with Noemi M. (pseudonym), Artesia, New Mexico, July 22, 2014.

[63] Human Rights Watch interview with Maria F. (pseudonym), Comayagua, Honduras, September 6, 2014.

[64] Human Rights Watch phone interview with Niloufar Khonsari, Immigration Attorney and Executive Director at Pangea Legal Services in San Francisco, California, October 11, 2014.

[65] US Commission on International Religious Freedom, “Study on Asylum Seekers in Expedited Removal,” February 2005, http://www.uscirf.gov/reports-briefs/special-reports/report-asylum-seekers-in-expedited-removal (accessed October 10, 2014).

[66] Ibid.