No Place for Children

Child Recruitment, Forced Marriage, and Attacks on Schools in Somalia

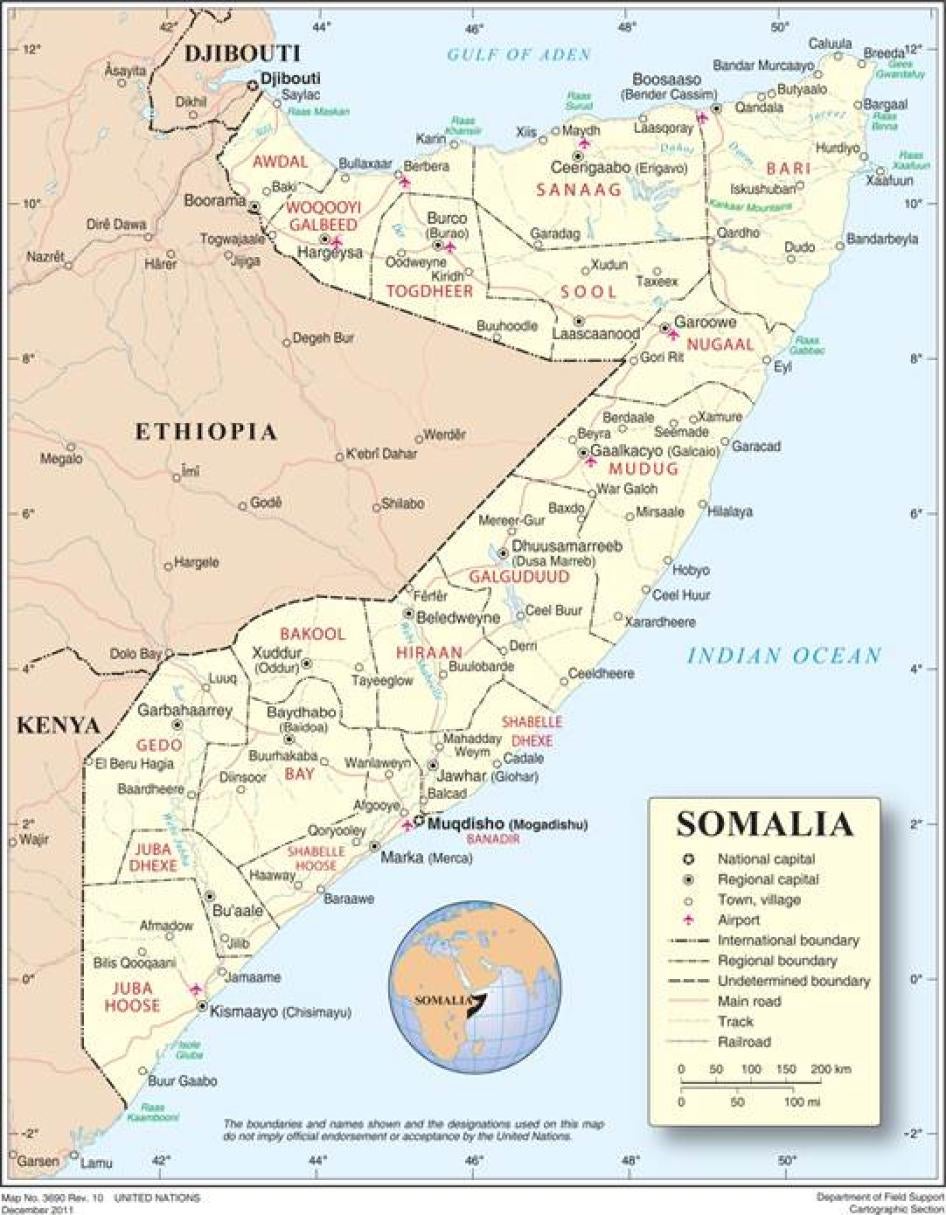

Map of Somalia

Summary

I was with al-Shabaab for three months in 2010…. They wanted to train us to fight and I was afraid. I didn’t want to kill people. I wanted to go back to school and learn.

—Amare A. (not his real name), 10-year-old boy from Mogadishu, living in Kenya, June 2, 2011

Children in war-torn Somalia face horrific abuses, including forced recruitment as soldiers, forced marriage and rape, and attacks on their schools by the parties to the conflict. Those responsible are never held to account.

Children, defined as anyone under age 18, have suffered disproportionately from the ongoing conflict. Fighting between the Transitional Federal Government (TFG), the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), and TFG-aligned militias on one hand and al-Shabaab, the Islamist armed group that now controls much of the country, on the other, intensified in the capital, Mogadishu, and other parts of south-central Somalia in mid-2010 and early 2011. In October 2011 the conflict in the southern regions escalated further with the incursion of Kenyan armed forces against al-Shabaab, followed shortly after by the arrival of Ethiopian forces.

Children are often the main victims of the indiscriminate artillery and small arms fire that has long characterized the fighting in Mogadishu. They are also the most affected by the ongoing humanitarian crisis, which is underpinned by a UN-declared famine through the south-central region of Somalia as well as the ongoing conflict between al Shabaab and the TFG.

This report documents al-Shabaab’s targeting of children for recruitment as soldiers, forced marriage, and rape, with a focus on abuses in 2010 and 2011. In addition, it documents how the group has targeted students, teachers, and school buildings for attack. Al-Shabaab fighters have also used schools as firing positions, and the students inside as “human shields,” placing children at risk of injury or death from indiscriminate or disproportionate return fire from TFG or AMISOM forces.

Children have served within TFG forces and TFG-aligned militias, although Human Rights Watch has not been able to independently confirm how widespread children’s participation is.

For this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed 164 newly arrived Somali refugees in the Dadaab refugee camps and in Nairobi in May and June 2011. Interviewees included more than 81 girls and boys who were under age 18 at the time. Human Rights Watch also interviewed TFG officials, officials of United Nations (UN) agencies and the African Union, members of nongovernmental organizations, and members of the diplomatic community.

While the presence of children in fighting forces in the 21-year-long Somali conflict is not a new phenomenon, there has been an unprecedented upsurge of al-Shabaab forced recruitment of children since mid-2010; attacks on students, teachers, and schools have also been prevalent in the last two years.

Although al-Shaabab has long relied on spreading extremist propaganda and material rewards to coerce children to join, since mid-2010 it has increasingly recruited children forcibly to replenish its dwindling ranks.

Children have nowhere to hide. Al-Shabaab has abducted them wherever they congregate: schools, playgrounds, football fields, and homes. Schools in particular have been attractive targets—14 of the 21 child escapees from al-Shabaab whom Human Rights Watch interviewed were taken from schools or on their way to school.

Life for children in al-Shabaab training camps is harsh: boys undergo grueling physical combat training, weapons training, and religious and political teaching during which some describe being forced to watch videos of suicide bombings. Boys also described witnessing brutal physical punishments and executions of those accused of spying for the TFG, and those attempting to escape or merely failing to obey orders.

Al-Shabaab militants send children to the front lines, often with little training. Several witnesses spoke of children serving effectively as “human shields” for more experienced fighters during some of the most intense fighting in Mogadishu. Others, including children too young to carry military weapons, were aggressively coerced and threatened into serving as suicide bombers. Besides participating in active combat, al-Shabaab uses children in a multitude of support roles, including carrying ammunition, water, milk, and food to the front lines; removing the wounded and killed; and working as spies, guards, and porters.

Abducted girls are assigned cooking, cleaning, and other domestic duties in the camps. Al-Shabaab uses girls and young women not only for support for combat operations, but also for rape and forced marriage to fighters.

Children, their families, and their teachers who try to prevent recruitment and abduction or who attempt to escape face severe consequences. Al-Shabaab has killed or injured parents who intervened to protect their children although, on occasion, parents and community leaders have successfully negotiated the release of abducted children with local al-Shabaab leaders.

When children “defect” or escape from al-Shabaab into the hands of the TFG or AMISOM, or are captured on the battlefield, they face interrogation by the TFG security services, detention, and an uncertain future instead of being protected as children.

While the available information suggests that the TFG itself does not forcibly recruit children, children have found their way into its ranks, often by volunteering for TFG forces or those of aligned militias, manning checkpoints, and taking part in combat.

The TFG has to date failed to ensure that stringent and systematic age screening procedures and standards are in place to screen all its recruits and forces. Recruits who have not attended a training funded by the European Union (EU) in Uganda and have been directly recruited from militias are particularly likely to escape screening. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any member of the TFG forces being held to account for the recruitment and use of children.

Schools have featured heavily in al-Shabaab’s combat operations as well as its efforts to control Somalis’ everyday lives. Many Somali children are no longer in or have never been to school. Somalia has one of the lowest rates of enrollment in the world; however, children and young people who have persisted in attending school have found themselves, their teachers, and their school buildings intentionally targeted for attack by al-Shabaab.

Al-Shabaab forces have turned schools into battlegrounds, firing at TFG and AMISOM forces from functioning school buildings and compounds, deliberately placing students and teachers in harm’s way from often indiscriminate return fire by TFG and AMISOM forces. Al-Shabaab has in some cases bombed school buildings, killing students, teachers, and bystanders. The group has used schools to recruit students as fighters and to abduct girls and young women for rape and forced marriage.

Al-Shabaab has imposed their harsh interpretation of Islam on schools in areas that they control, prohibiting English, the sciences, and other subjects deemed improper, and enforcing severe restrictions on girls’ dress and interactions with male students. They have threatened and even killed teachers who resist their methods, lectured students on jihad and war as a recruitment tool, and placed their own teachers in schools. Lessons have been left devoid of substance, teachers have fled, and, where schools have not shut down entirely, children, deprived of any meaningful education and afraid for their safety, have dropped out in large numbers. Girls have dropped out disproportionately.

There remains no accountability in Somalia for violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. The TFG and AMISOM have not taken action against commanders responsible for laws-of-war violations or the conscription of children. Al-Shabaab has to date been impervious to all calls to end human rights abuses. Governments supporting the TFG and AMISOM have largely failed to recognize that al-Shabaab atrocities are counterproductive and no excuse for abuses by the Somali government.

The TFG initially denied the presence of children within its forces but has more recently publicly acknowledged the need for action to be taken to end their presence and use. In November 2011 the TFG reiterated a commitment to enter into a formal UN action plan to end its use of child soldiers. To date this commitment has not translated into necessary changes and concrete measures on the ground, notably ensuring stringent and systematic screening of all TFG recruits to prevent child recruitment and holding accountable those responsible for the recruitment and use of children in its forces. For the planned integration of militia groups into the TFG forces, effective vetting measures are essential.

The TFG has come under too little pressure to improve its record on children’s rights, or human rights more generally, by key international actors who, by offering political and financial support to Somalia, are in a position to demandprogress. These include the UN, the United States (US), and the EU. The “Roadmap” signed in September 2011 under the auspices of the UN Political Office for Somalia (UNPOS), which is seen by international partners of the TFG as the main instrument through which to hold the TFG to account, vaguely refers to ending recruitment of children but fails to include clear benchmarks that would enable monitoring compliance. While the UN and US have recently called on the TFG to end the use and recruitment of children, to date they have not sought to condition support to TFG forces on this basis.

There is no easy solution to the dire reality facing Somali children, many of whom have known nothing but war. But parties to the conflict and other key actors involved in Somalia should begin to prioritize the issue of children’s rights, child protection, and education on the political and security agenda. The risks of continuing to fail to protect and provide safe and accessible education to Somalia’s children will result in yet another generation lost to conflict, with few options for the future.

Human Rights Watch urges all warring parties in Somalia to immediately end violations of the laws of war, in particular indiscriminate attacks against civilians. On children specifically, we call upon al-Shabaab, the TFG, and TFG-aligned militias to end the recruitment and use of children within their ranks. Al-Shabaab should publicly order its commanders to end the recruitment and use of children, and immediately hand over children within its forces to a civilian protection body, cooperating with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and child protection actors to ensure their safe release. It should also immediately end targeted attacks on students, teachers, and schools.

The TFG with international assistance should immediately ensure that stringent and systematic age screening procedures and standards are put in place for all its recruits. It should also hold to account those responsible for violations of child’s rights, including the recruitment and use of children and unlawful attacks on schools. It should also ensure that captured children alleged to have been formerly associated with al-Shabaab are promptly transferred to civilian rehabilitation and reintegration programs. Children should not be detained solely for their association with armed opposition groups.

International partners of the TFG should press the TFG to fulfill its commitments to develop and implement a national action plan to end the recruitment and use of children during the remaining transitional period. And they should impose concrete consequences on the TFG for failing to do so. The TFG’s partners, notably the US, should also ensure that the TFG meets international standards regarding the treatment of children formerly associated with al-Shabaab.

Monitoring and reporting on human rights violations, notably violations of children’s rights, should be reinforced. To this end, donors should politically support and fund the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to reinforce its capacity to carry out its human rights monitoring and reporting mandate on Somalia and appoint a child rights expert within the OHCHR Somalia structure. The UN Security Council should enhance the capacity of the UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea to enable it to fulfill its extended human rights mandate.

AMISOM and the TFG should, where feasible, map key civilian infrastructure, including schools, and use this map to identify and protect schools in areas of AMISOM and TFG military operations.

International support for child protection activities, including the provision of medical and psycho-social support for survivors of sexual violence, education, and vocational training activities should be significantly increased both inside Somalia and in refugee receiving countries, namely Kenya and Ethiopia.

Finally, addressing the human rights crisis that underpins the conflict in Somalia also means tackling longstanding impunity. The TFG and its international partners should call for the establishment of a UN Commission of Inquiry—or a comparable, appropriate mechanism—by the UN to document serious international crimes committed in Somalia and recommend measures to improve accountability.

Key Recommendations

To the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia, and Transitional Federal Institutions

- End all recruitment and use of children under age 18 by TFG forces and aligned militias by developing and adopting a national action plan that establishes rigorous and systematic screening procedures, and by holding to account anyone found to be conscripting or using children, consistent with widely accepted international standards.

- Develop procedures to transfer captured children promptly to civilian rehabilitation and reintegration programs. Children should not be detained solely for their association with armed forces and groups.

- Map key civilian infrastructure, including schools, with the assistance of relevant agencies including the Education Cluster. Use this map to identify and protect schools in areas of TFG military operations.

- Ensure that all credible allegations of violations of international human rights and humanitarian law by TFG forces and aligned armed groups are promptly, impartially, and transparently investigated, and that those responsible for serious abuses, regardless of rank, are held to account.

To al-Shabaab

- Immediately cease recruitment of children under 18 years old and release all children currently in al-Shabaab forces who are under 18.

- Immediately end the abduction of girls and women, and release all girls and women abducted for forced marriage or other purposes.

- Ensure that schools are identified and protected and that students, teachers, and school administrators are able to safely leave school buildings during military operations where they may be at risk.

To Foreign Parties to the Conflict: AMISOM and the African Union, Kenya, and Ethiopia

- Map out key civilian infrastructure, including schools, with the assistance of relevant agencies, including the Education Cluster, in order to ensure that schools in areas of military operations are identified and protected.

To All States and the Donor Community in Somalia

- Provide the TFG with the necessary support and capacity to systematically and effectively screen all its recruits by age in order to prevent the recruitment and use of children within its forces.

- Ensure that trainings provided to the TFG forces and personnel include appropriate training in international humanitarian law, including the protection of civilians and civilian objects and protection of children’s rights.

- Support and fund an increase in the capacity of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to monitor rights violations.

To the UN Security Council and the UN Human Rights Council

- Intensify pressure on the TFG to immediately adopt and promptly implement a time-bound UN action plan to end the recruitment and use of children, one that includes screening procedures to ensure that children are not recruited into the TFG or included in aligned militias that are integrated into the TFG armed forces.

To the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and Other Child Protection Agencies in Somalia and Kenya

- Greatly expand demobilization, rehabilitation, and reintegration programs for children formerly associated with fighting forces and children recruited for forced marriage.

Methodology

This report documents violations of international human rights and humanitarian law affecting children by all parties to the conflict in south-central Somalia in 2010 and 2011. Violations include the recruitment and use of children by the parties to the conflict, rape and forced marriage of children, and attacks on education, namely the targeting of students, teachers, and schools. While children are among the most vulnerable groups of conflict-affected populations, for both protection and health reasons, throughout 2010 and 2011 increasing anecdotal reports that children were being specifically targeted began to emerge from those fleeing the fighting in Somalia.

This report is based in large part on interviews with Somali refugees in Kenya. In May and June 2011, three Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed more than 164 Somali refugees in the Dadaab refugee camps and in Nairobi. Interviewees included more than 81 boys and girls and who were under age 18 at the time. We also interviewed young adults who had experienced abuses in 2010 and 2011 while under age 18 or who had recently studied in primary and secondary classes as over-age students and had information about abuses against children in schools during this period, as well as parents of child victims, and teachers. Many of those interviewed arrived in Kenya from Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu, in mid-2010 or later when fighting became particularly intense. Two Human Rights Watch researchers previously interviewed 82 Somali refugees—men, women, and children—in November 2010 following al-Shabaab’s “Ramadan offensive” of 2010.

Relying primarily on the accounts of individuals who were able to flee Somalia made it easier for them to speak more freely but also skewed the reporting towards people of certain backgrounds and from certain geographic areas. For example, despite secondary reports of significant recruitment of children by al-Shabaab in the Bay and Bakool areas, many of the children interviewed were from Mogadishu and had more often than not been able to draw on some sort of family or clan support in Mogadishu to assist their flight.

Human Rights Watch also carried out interviews between August 2011 and January 2012 documenting abuses against IDPs in Mogadishu.

For security reasons, Human Rights Watch was not able to visit any of the camps and detention facilities in Mogadishu where the TFG has been holding children formerly associated with its own forces or with al-Shabaab.

Refugees and asylum seekers identified as recent arrivals to Kenya participated in voluntary, open-ended interviews. Interviewees were asked to relate events that they personally experienced or witnessed. Interviews with refugees were conducted in Somali with the assistance of interpreters. All of the interviews were conducted on a one-on-one basis, unless otherwise indicated in the footnotes. The names of interviewees and all victims of abuses have been changed and the exact location of interviews omitted for security reasons. Many requested anonymity, indicating their deep and persistent fear of al-Shabaab and others, even within Kenya. Other identifying details of the interviewees have, in some cases, also been withheld to preserve anonymity. Given the lack of birth registration in Somalia and the fact children and young adults are not always aware of their age, Human Rights Watch researchers asked a range of questions to seek to confirm the age of the interviewees and asked parents when they were available.

Human Rights Watch also spoke in person and by phone with TFG officials; officials of UN agencies and the African Union; members of Somali and international nongovernmental organizations working on human rights, child protection, and education; and members of the diplomatic community. These interviews were conducted through December 2011, in order to ensure the most up-to-date information prior to publication.

In this report “child” and “children” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law.

I. Background

Civilians, including children, have borne the brunt of the ongoing civil armed conflict in Somalia. Children have suffered both from the conflict generally and because they have been specifically targeted for recruitment, rape, forced marriage, and other grave violations of international law by the parties to the conflict. In addition, Somalia currently faces one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises as a result of ongoing fighting, drought, and the blocking of humanitarian assistance by al-Shabaab forces. From July 2011 to February 2012, famine was declared by the UN in six regions of south-central Somalia, a number later reduced to three. As statistics demonstrate, children are most affected by famine.

Brief Summary of Somalia’s Conflict

The current armed conflict in Somalia began with the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991 and intensified following the overthrow of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), which was an alliance of sharia courts that aligned itself to rival the administration of Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in December 2006. The ICU gained control of Mogadishu and other parts of south-central Somalia in mid-2006 and brought a temporary semblance of stability to Mogadishu but was seen as a security threat by Ethiopia, which subsequently intervened militarily, driving out the ICU in late 2008.[1]

For two years following the Ethiopian intervention in December 2006, Ethiopia and the weak TFG of Somalia (set up in 2004)[2] were involved in intense fighting against Islamist armed groups, including al-Shabaab.[3] The fighting focused on Mogadishu, where Ethiopian forces with TFG support were responsible for frequent indiscriminate artillery attacks causing high civilian casualties in violation of the laws of war. These forces and Islamist armed groups were also responsible for unnecessarily placing civilians at risk, unlawful killings, rape, torture, and looting.[4] None of the warring parties made any effort to hold those responsible for war crimes to account. Nor did the international backers of the TFG and Ethiopian forces, namely the US, the UN, and the EU, acknowledge the level of abuses or take action to end them.

In January 2009 the Ethiopian armed forces withdrew following the UN-led Djibouti peace agreement.[5] This agreement also yielded a new and expanded Somali administration and led to the election of Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, the former head of the ICU, as the new TFG president.

Many ordinary Somalis were optimistic that the conflict and massive rights abuses that had become part of their daily lives would end with the Ethiopian withdrawal. However, within months they once again faced open warfare, this time between the TFG, now backed by the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), and Islamist armed groups, including the increasingly powerful al-Shabaab. This fighting was once again characterized by indiscriminate attacks and abuses committed with complete impunity. While mandated by the UN Security Council to protect TFG institutions, AMISOM increasingly became seen as a party to the conflict, as they began to actively engage in running battles with al-Shabaab fighters.

Fighting intensified in May 2010 with laws-of-war violations being committed by all warring parties.[6] During the Islamic holy month of Ramadan in August and September 2010, al-Shabaab called for a final offensive to topple the TFG, and fighting escalated. In response, in September the TFG launched an offensive, with AMISOM’s support, to reclaim areas of Mogadishu under al-Shabaab control. Serious violations of the laws of war were committed by both sides during these offensives, including the indiscriminate shelling of civilian areas and infrastructure with rocket and mortar fire that resulted in high civilian casualties and the displacement of tens of thousands of people.[7]

Between February and April 2011 the TFG, again supported by AMISOM, launched a series of offensives in Mogadishu and further afield against al-Shabaab forces,[8] capturing several parts of the capital. The TFG and pro-TFG militias, including Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a (ASWJ) and Raskamboni, primarily supported by Ethiopia and Kenya respectively, also gained control of small areas in the Gedo and Lower Juba region, along Somalia’s Kenyan and Ethiopian borders.

In August 2011 the TFG and AMISOM launched a new offensive against al-Shabaab in Mogadishu, reportedly to preempt another possible Ramadan offensive. On August 6, al-Shaabab declared that it was pulling out its forces from Mogadishu. On October 16, Kenyan military forces entered border areas in Somalia and indiscriminately bombed several towns in which al-Shabaab forces were allegedly deployed. Despite its withdrawal from Mogadishu, at the time of writing, al-Shabaab continues to control more of southern Somalia’s territory than any other faction and retains the ability to carry out attacks in Mogadishu.

The ability of the TFG to stabilize zones that have come under the government’s control has been hampered by the longstanding political crisis between President Sheikh Sharif and the speaker of the parliament, Sharif Hassan Sheikh Aden, who has presidential ambitions.

In June 2011 the TFG extended its mandate and the transitional period, scheduled to end in August 2011, for another year. The “Kampala Accord,” signed on June 9, 2011, by President Sheikh Sharif and Speaker Sharif Hassan, called for the resignation of the popular prime minister, Mohammed Abdullahi Mohammed, and postponed elections to 2012. It also called for the development of a “roadmap” with clear benchmarks to guide the implementation of priority transitional tasks: the constitution, a security and stabilization plan, and reconciliation and anti-corruption efforts.

Major Parties to the Conflict

The following is an overview of the major parties to the armed conflict in Somalia as of late 2011.[9]

Transitional Federal Government (TFG)

Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government (TFG), set-up in 2004, is recognized by the UN and almost all key foreign governments (with the notable exception of Eritrea) as the legitimate government of Somalia. Until 2011, it controlled only a small section of southern Mogadishu, but extended its control over several areas of the city in the course of 2011. The embattled TFG depends on the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) for its survival and security, and on donor funds. It has proved unable to assert political control, build key government sectors, or provide the essential services that would build its credibility. Infighting between different factions and components of the Transitional Federal Institutions (TFIs), of which the TFG is a component, has significantly hampered political developments.

Al-Shabaab

Al-Shabaab is a militant Islamist group that began as part of the armed wing of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) when the courts rose to power in Mogadishu in 2006. Al-Shabaab is not a monolithic entity but rather an alliance of factions that initially rallied under its banner with the aim of forcing the Ethiopian troops to leave Somalia. These groups retain a limited common agenda of defeating AMISOM and the TFG and extending its extreme interpretation of Sharia (Islamic law) across Somalia. Al-Shabaab currently controls more territory in southern Somalia than any other faction and became the largest armed insurgent group in December 2010 following its merger with Hizbul Islam, another Islamist armed group led by former ICU member Hassan Dahir Aweys. Al-Shabaab withdrew from Mogadishu in August 2011 but continues to carry out attacks in the war-torn capital.

Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a

Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a (ASWJ) is a moderate Sufi Islamist group that has on paper been officially affiliated with the TFG since March 2010. The group exists primarily in central Somalia, where it has managed to maintain control over large swathes of territory, predominantly in Galgadud and Hiraan regions of central Somalia. It has more recently captured small areas of territory in the Gedo region along the Ethiopian border from al-Shabaab. It receives financial and military support from Ethiopia.

African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM)

Initially deployed to Mogadishu in 2007, AMISOM is mandated by the African Union Peace and Security Council and the UN Security Council to provide protection to the Somali transitional institutions, including the TFG and Parliament. However, since 2009, and especially since coming under attack from al-Shabaab, it has increasingly taken part in the conflict.[10] AMISOM has as yet not approached its authorized troop strength of 12,000; its current contingent at least 10,000 Burundian, Ugandan, and more recently Djiboutian forces.[11]

Drought, Famine, and al-Shabaab’s Restrictions on Humanitarian Access

Compounding the dire effect of ongoing fighting on civilians is unrelenting drought, famine, al-Shabaab’s severe restrictions on humanitarian aid and ongoing diversion of aid in TFG-controlled areas.

Severe drought in south-central Somalia worsened from October 2010 onwards. By August 2011, the UN had declared six regions—primarily in southern Somalia—to be in a state of famine. An estimated four million people, more than half of the Somali population, were in crisis as of that month, around three million of whom were in the south in predominantly al-Shabaab-controlled areas.[12] As of January 2012, according to the UN, four million Somalis remain in need of humanitarian assistance.[13] The Somali population of internally displaced persons and refugees—already one of the largest in the world—has further escalated: one-quarter of Somalia’s estimated population of 7.5 million was either internally displaced or lived outside the country as refugees as of December 2011.[14]

Aid agencies have been limited not only by conflict and insecurity but also by al-Shabaab, which has restricted some agencies’ work. The group has imposed a ban on over a dozen individual agencies since 2009, placed significant financial and logistical burdens on organizations that are working in areas under their control, and threatened and attacked humanitarian workers. In early July 2011 al-Shabaab declared that it was lifting the ban it had imposed on certain foreign aid agencies in areas under its control as long as the distribution of aid was their only objective.[15] But the ban has yet to be lifted and by November al-Shabaab had proclaimed a fresh ban on 16 aid organizations, including UN agencies.[16] Al-Shabaab also continues to severely restrict the freedom of movement of those seeking access to humanitarian assistance in areas under its control.

Access to humanitarian assistance in areas under TFG control has also been hampered by diversion and looting of humanitarian aid.[17] Media reports in August 2011 suggested that food aid diversion in Mogadishu was occurring on a large scale.[18]

Counterterrorism legislation, and most notably the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions that seek to prevent support reaching designated terrorist organizations, have also negatively impacted humanitarian operations in Somalia, resulting both in a significant decrease in US funding of humanitarian organizations since 2008 and the imposition of burdensome measures on those receiving US support. [19]

Children in the Somali Conflict

Children continue to be killed or maimed as a result of indiscriminate shelling, gunfire, widespread insecurity, and the targeting of schools. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported that in 2010, 43 percent of patients admitted to the two main referral hospitals in Mogadishu with war-related injuries were women and children.[20]

The difficulties that humanitarian agencies face trying to access south-central Somalia further aggravates the situation of children, who are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity and disease. Severe acute malnutrition rates among children doubled between March and July 2011.[21] By August the number of children suffering from acute malnutrition was estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands.[22] Half of the tens of thousands of individuals who have died as a result of the famine are reported to be children.[23]

The destruction of livelihoods, traditional protection structures, and separation or destruction of families as a result of the length of the conflict, the humanitarian crisis, the number of civilian casualties, and repeated displacement of a significant proportion of the population has left children particularly vulnerable. The numbers of abandoned, orphaned, or separated children and children living and working in the streets has skyrocketed over the course of the last four years. While child labor has long been a part of Somali culture, children are now often the sole source of income to their families or siblings.

Children are also among the most vulnerable groups of internally displaced persons and refugees for both protection and health reasons. The number of unaccompanied minors and child-headed households among the displaced person and refugee population has increased over the course of the conflict, particularly since 2007. [24]

Children’s Access to Education in Somalia

Children’s right to education in Somalia is severely restricted.[25] According to UNICEF, Somalia has one of the lowest rates of school enrollment in the world, with a net primary school enrollment rate of around 23 percent in 2010.[26] Disparity between levels of enrollment between girls and boys even at the lower levels of primary school is alarming: according to the latest available data, the gross primary enrollment ratio was only 23 percent of girls, compared with 42 percent of boys.[27] Enrollment in secondary schools is minimal: gross secondary enrollment was only 11 percent for boys and 5 percent for girls in the late 2000s.[28] School dropout rates reportedly reached 50 percent following the Ramadan offensive in 2010 and 38 percent in the first four months of 2011.[29]

There are only five government-run schools in all of south-central Somalia, all located in Mogadishu. Other schools are financed primarily by parents, communities, or private individuals either in Somalia or in the diaspora, or by national or international donor and development organizations. While the total number of schools in south-central Somalia is unknown, agencies involved in the Education Cluster—the UNICEF- and Save the Children-led entity that coordinates organizations and agencies working in the education sector—funds 4,822 schools in these regions.[30] Secondary schools are scarce and found mainly in Mogadishu.

While not clearly standardized, there are generally four categories of schools in Somalia: primary and secondary schools employing Arabic, Somali, or Kenyan curriculum, as well as non-formal duqsi (Quranic schools). There is no unified national curriculum.

Despite the dire situation of the education system in south-central Somalia, the sector remains inadequately funded. As of November 2011, of the US$29 million requested under the Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP) for the education sector, only $18 million—62 percent—had been funded, in large part via UNICEF funding.[31] It is within this already terribly restricted environment that children are struggling to go to school.

II. Recruitment and Use of Children as Soldiers

The recruitment and use of children in the Somali civil war is not a new phenomenon: children have been used throughout the conflict by clan and warlord militias for the defense of the home and the clan. However, the level of recruitment and involvement of children in the conflict has substantially increased since early 2007 when recruitment became more widespread and targeted.[32] All the current Somali parties to the conflict in Somalia—including the TFG forces, al-Shabaab, Hizbul Islam, and Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a—have recruited or used children for military service.

Human Rights Watch interviews with Somalis who have fled Somalia since early 2010 indicate that forced recruitment and abductions have intensified in line with an upsurge in fighting. A significant proportion of children interviewed said they were forcibly taken from their schools, though many others recounted being abducted from playgrounds, football (soccer) fields, markets, and homes, primarily by al-Shabaab militants. Girls and boys have both been targeted, with girls taken primarily for domestic duties and boys taken to be trained for combat or other work on the front lines. The ever-present reality of forced recruitment and abduction has caused children to leave school, often fleeing the country with their families.

Children are afforded multiple special protections under the international human rights and humanitarian law framework.[33] All parties to the conflict in Somalia have an obligation to afford special protection to children and to ensure that children do not take part in hostilities.[34]

Human Rights Watch spoke with 19 boys and 4 girls who had been recruited by armed groups, and almost 50 parents, relatives, and others who were witnesses to child recruitment. With one or two exceptions, all of the recruited boys and girls with whom Human Rights Watch spoke said they had been recruited by al-Shabaab. Our research also found that children continue to be associated with the TFG and TFG-aligned militias, largely as a result of a lack of stringent age screening procedures.

Al-Shabaab

I tried to refuse but I couldn’t. I just had to go with them [al-Shabaab]. If you refuse, maybe sometimes they come and kill you or harm you, so I just went with them. One of my friends who was older than me, they came and started with him the same as they did to me and he refused, and they left him but another day they found him on the street and shot him.

—14-year-old boy, Kenya, May 29, 2011

Former child recruits and child and adult witnesses described to Human Rights Watch how al-Shabaab forces took children to their training camps throughout 2010 and 2011. Most of the children were reportedly between ages 15 and 18 but some were as young as 10 years old. From the camps they were sent to the front lines or forced to act as porters, spies, and suicide bombers. Children have been injured, maimed, and killed.

Al-Shabaab’s recruitment of children has been widely reported.[35] Forced recruitment of children became common practice in 2009, but by April 2010 anecdotal reports indicated that child recruitment increased significantly and has shown no signs of reducing. While exact numbers of children recruited by al-Shabaab is unknown, in April 2011 a report from the UN secretary-general cited military sources stating that al-Shabaab abducted an estimated 2,000 children for military training in 2010.[36]

Fourteen of the twenty-three children whom Human Rights Watch interviewed who were recruited said that al-Shabaab recruited them from school or while they were traveling to and from school. The other children recruited by al-Shabaab said that al-Shabaab took them from parks and playing fields, or even in their own homes. For example, Galaal Y., a 14-year-old boy from Hamar Weyne district in Mogadishu, described how in December 2010 two of his primary school classmates lured him to a field to play football where he was ultimately taken by al-Shabaab and forced to become a fighter:

Two of my classmates, who I later realized were working with al-Shabaab, ages 16 and 18, had written our names down on a list to form a football team. The next day we went along to a field to play, thinking that another team would come along, but when we arrived at the field, al-Shabaab arrived instead. They came in a vehicle and were wearing khamis and headscarves.[37] They were armed with AK-47’s [military assault rifles] and told us that playing football was not helpful and they would turn us into jihadis [Islamic fighters]. They took 16 of us between the ages of 10 and 16.[38]

Children said that al-Shabaab regularly uses children as intelligence gatherers or intermediaries to identify other children of fighting age, and then uses these children to pressure or force their peers to join al-Shabaab. A 16-year-old boy from Mogadishu told Human Rights Watch how he was approached and forced to join al-Shabaab in the mosque while attending evening prayers:

I was a student and al-Shabaab forced me to fight against the TFG…. They came to the mosque when we went for prayers. They pretend they are an imam [preacher] and use Islamic teaching to try and make you join. If you refuse to join they will kill you.

The guy who spoke to me had staff all around him. They were merged into the crowd of the mosque. He spoke to me directly. They were approaching everyone, even teenagers…. He used the words of the Quran and said the government was not concerned with religion.

They tell you to join, and if not, the boys around him (the ones in the crowd) who were 13 and 14 years old will come and kill you. They had guns with them and a grenade attached to the side of their pants.[39]

Despite some territorial gains by TFG and AMSIOM forces in late 2010 and early 2011 in Mogadishu, as of July 2011 al-Shabaab still controlled eight of the sixteen districts of the capital.[40] In al-Shabaab-controlled areas, there was virtually nowhere that children could be assured of their safety. While families sought shelter in their homes during periods of intense fighting between al-Shabaab and AMISOM forces, homes offered no protection from the ongoing forced recruitments by al-Shabaab.[41] Children told Human Rights Watch how al-Shabaab approached homes where families were known to have boys considered old enough to fight and demanded that families hand them over to join their forces.

Several children told Human Rights Watch that they were recruited by their own family members—fathers, brothers, and cousins—who had joined al-Shabaab. A mother described how her husband took their 10-year-old son to battle:

My husband was in al-Shabaab. He came and said to my eldest son [who was 10 years old], “You must also join.” He overpowered me and took my son. Later I heard my son died in the war. I went to where my husband was, Horera mosque, and I said, “I heard my son died.” He said, “I am pleased to inform you that our son died a martyr. He went straight to paradise.” He showed me footage he took of my son being killed in the war. His blood. His body. I cried.[42]

While almost all of the 23 children interviewed by Human Rights Watch were forcibly recruited, there were also reports of some children who joined al-Shabaab “voluntarily,” particularly after intensive campaigns of recruitment. The very notion of voluntariness of any child’s decision, particularly in a context of extreme poverty, hunger, and al-Shabaab’s well-known violence against those who refuse, to join an armed group is questionable.[43]

Al-Shabaab has put various forms of pressure on children to join their forces. Children spoke of multiple tactics to entice them to join, including offering cash and mobile phones and forcing children to study religious propaganda as part of their schooling. Baashi M. described how his 12-year-old brother joined al-Shabaab:

They gave him $100 and convinced him at school that if he became a martyr he would go to paradise. They also bought him clothes. He never told my parents he was going, he just disappeared. He wanted to be a driver and al-Shabaab said they would send him to driving school.[44]

Other children were offered cash incentives to recruit other children, as one 15-year-old witness recounted:

Many of my friends were given incentives—money to enroll others. Depending on how many you enroll you would be given more or less money. Many boys enrolled. If you refused to enroll you were forced to.[45]

A teacher explained how effective these incentives are: “80 percent [of my students] are so poor. They have no money so when they give them money they will join…. A whole generation—95 percent—they join the armed groups because of hunger. There is nowhere to go, just to get a gun and fight. Daily they get money. If they don’t join, they don’t get food.”[46]

Several children told Human Rights Watch that al-Shabaab brought their members into schools to teach subjects such as “jihad,” where children were lectured on their duty to join the jihad and promises of “entry into paradise” if a child died as a martyr. The classes, which ranged from daily to weekly classes, were also used as a way for al-Shabaab to gain entry into the school and recruit children. Children described being lectured on the virtues of jihad, shown Islamist propaganda videos, and given weapons demonstrations. Sometimes these methods convinced girls and boys to join. One young woman said that about 15 of her 40 to 45 classmates—5 girls and 10 boys—decided to join after a jihad class.[47] Other children also described a mix of propaganda and force that led them and their classmates to join. For example, Iskinder P., age 15, said he decided to join both because he was “being forced” and “because the majority of my teachers were al-Shabaab and they used to lecture us and tell us ‘Al-Shabaab is good, let’s defend our country. These are foreigners who are fighting our country.’”[48]

Baashi M., a 27-year-old student who was attending the Juba Primary School in the southern port city of Kismayo, described how al-Shabaab would come into the school and use the classes as a precursor to forcibly taking students to fight:

Al-Shabaab used to come to my school often, sometimes they would come two to three times a day. They came and picked up kids between 12 and 20 years old and would take them to a building in the school and play DVDs of jihadis on the battlefield on a laptop. They would also preach about religion. They took me there in February 2010.[49]

Similarly, an over-age student in primary school from Suuqa Xoola, Mogadishu, said: “Initially they preached ideology, but when they realized that they were not recruiting they decided to recruit forcefully. This is what made me flee.”[50]

Retaliation against Children and Families Who Refuse

Al-Shabaab said to my elder brother, “Come with us.” He refused and they beheaded him. He was 16. They took him and put his head in front of our house.

—Deka R. (not her real name), 13-year-old girl whose brother was killed in El Ashabiya, Somalia, around Ramadan 2010, June 5, 2011

Children repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that they felt powerless to resist recruitment by al-Shabaab. Witnesses spoke of “children who had refused recruitment having their hands cut off” or in some instances beheaded.[51] Knowing that refusal would mean being taken by force or possibly killed, children recounted the fear they felt as al-Shabaab fighters entered their schools and homes and the desperate measures they would take to escape detection. One witness said that at his school, children would “stampede” and “scramble out of windows,” jumping from second and third floor windows and landing on top of each other in desperate bids to escape.[52]

Parents other family members regularly attempt to protect both girls and boys from being recruited by al-Shabaab, according to witnesses. Al-Shabaab has killed and injured relatives, and in some cases school teachers, who get in their way. Human Rights Watch documented half a dozen such cases. In two cases mothers said they personally intervened to prevent their children from being recruited.[53]

One mother told Human Rights Watch how she tried to defend her four youngest children from recruitment. After she pled and physically tried to prevent the children from being taken, her husband, an al-Shabaab member, shot her in the ankle.[54] In another incident, in December 2009, al-Shabaab entered the Shabelle Primary School in Mogadishu and forced parents to sign an agreement allowing their children to join al-Shabaab. An eyewitness told Human Rights Watch:

Two fathers who refused to sign were threatened in the meeting and told they would not survive this. They were shot a day later in the Bakara market with letters pinned on their bodies saying this is what would happen to any parent who refused to allow their children to join al-Shabaab.[55]

Abuses in Training Camps

Once recruited, children are typically taken to an al-Shabaab training camp.[56] Almost all of the children Human Rights Watch interviewed whom al-Shabaab had recruited said that they had spent time in a training camp for durations ranging from several weeks to three years before they escaped.[57] In many instances they were unable to give the exact locations, often because they were blindfolded on the way, but most said they were held somewhere around the outskirts of Mogadishu. Others said they were held in and around former government installations in al-Shabaab-controlled areas in the city, surrounding Kismayo, and in and around the southern Shabelle regions.

Camps varied in their descriptions, ranging from physical structures, including former government buildings, where children were detained in cells with minimal food and poor sanitary conditions, to open, camp-like settings with children sleeping on open ground. Omar A., 17, described the training camp on the outskirts of Mogadishu where he was held for two months:

The place looked like the bush, and there were tents and vehicles. There were many people there, maybe 300. There were adults and children but we didn’t speak much to them. Al-Shabaab said, “You will work with us, you will fight, and we will train you.” You can’t say you don’t want to because they force you and they have weapons and if you refuse they will kill you.[58]

A 17-year-old boy who was kept in one such facility told Human Rights Watch:

There was no good food. Sometimes they beat me. I couldn’t see anyone. Sometimes they threatened to slaughter me. They tied my hands and legs. They threatened that if I identified their place and they released me they will get me again and cut me to pieces. Sometimes they took me outside the room and put cold water on my body….. I was in the dark the whole time. I couldn’t see anyone, seated there, no sleep, they come and tell you they’ll slaughter you.[59]

Girls were reportedly brought to some of the camps to clean, cook, and serve food. They were also forced to marry fighters and raped (see below).

The training camps prepared boys to fight. There were consistent reports from inside the camps of children being trained for combat as well as being given a variety of other domestic and logistical tasks. Training, they said, lasted from one week to several months.[60] At minimum, children told us that training included basic physical and light weapons training with AK-47 assault rifles and pistols. The training followed a regular routine. A 13-year-old boy from Mogadishu explained:

In the morning they told us we were going for training. They told us to jump in holes, climb over piles of trees. It was a hectic training and difficult for my age. At times they told us to crawl or roll on the ground or crawl between metal poles without touching them. It was difficult. We had to do push-ups, walk in a funny style. It was so difficult. After two weeks training, they gave us pistols and a card, made us mark it, put it at a distance, and told us to shoot that mark.[61]

Children described harsh physical conditions, including being forced to sleep in the open, given little food to eat, and forced to undertake grueling physical training schedules to prepare them for combat. If children refused, they said they received harsh physical punishments. As one 14-year-old boy told us: “We trained until 1 p.m. They made us to do sit-ups and walk on our knees. I was saying, ‘I am exhausted, I can’t do anymore,’ and they cut me with a big knife. A big knife that you use to slaughter animals.”[62] Another boy showed a four- to five-inch scar on his upper arm he said he had gotten from being whipped, recounting: “On the first day I shot [an AK-47] three or four times but they found me shaking. When they saw me trembling they encouraged me and said, “You are doing this for religion and you must carry it.”[63]

A majority of children interviewed by Human Rights Watch also reported being given religious education that stressed the importance of participating in the jihad. This sometimes included watching video footage of jihadist groups fighting in other countries.[64] The children also said they conducted regular prayer and religious practice.

Punishment and Executions

Anyone found escaping will be killed. Even at night when we were sleeping and in the morning they would cane us. They wouldn’t tell us why, they would just beat us.

—Amare A. (not his real name), 10-year-old boy previously held in an al-Shabaab training camp, Kenya, June 2, 2011

Several children said they witnessed brutal physical punishments and executions at the

camps, sometimes involving other children. The reasons for execution varied from not obeying orders and attempting to escape to accusations of being a TFG spy.

A 16-year-old boy described how he and other children were forced to watch executions of “enemies of al-Shabaab”:

I was made to watch an execution of a group of people who were considered to be al-Shabaab enemies, as they were accused of supporting the TFG or rejecting al-Shabaab. About 20 people were killed that day. I did not see any children being killed. It was the older recruits who were around 25 and up who were made to execute the people.[65]

In another example, an eyewitness said that he and his classmates were taken to a camp from their Mogadishu primary school, and those who refused to participate in training were executed in front of their peers:

Out of the fifteen abducted, five died in training school. The five never agreed to join al-Shabaab and hid. They [al-Shabaab] brought them and paraded them in front of us and shot them. They were 10, 14, 15, 16, and 17 years old.[66]

Children also said they were forced to hand out violent punishments to people found to be breaching al-Shabaab’s rules. Human Rights Watch interviewed seven children who had been forced to take whips and patrol the town looking for businesses that remained open during prayer time, women wearing clothes al-Shabaab deemed inappropriate, or young people listening to music on their telephones. A 15-year-old boy from Middle Juba explained:

I was given two jobs, to whip women and to punish boys who had music on their mobile phones. I would make them swallow the memory card. I made 20 youth swallow the cards and I must have whipped 50 women. I would go with older men backing me up. They were about 30 years old and there were five of them. They would stand with me and force me. I felt bad to whip someone my mother’s age. Other children were given similar jobs.[67]

Some children said they were sent to patrol towns under al-Shabaab control and identify to catch adults and children who had escaped from training camps. Iskinder, age 15, told us:

Some people escaped with vehicles and I had to catch them. We would shoot the vehicles’ tires so they couldn’t move and take them back. We used to identify the people who escaped. I didn’t want to do it but we were forced many times. We were told to go and stand on the street and identify escapees. We used to beat them and take them to jail. I had a cane and a weapon.[68]

Fighting on the Battlefield

Children, mostly boys, said they were sent to the front lines from the training camps, often with minimal training. There, witnesses said, al-Shabaab uses children for a range of activities, from supplying fighters to serving as “human shields” to protect more experienced fighters.

Fighting between al-Shabaab and the TFG and AMISOM intensified in August 2010, during what was referred to as the “Ramadan Offensive 2010.”[69] During this period and the months to follow, al-Shabaab was engaged in sustained clashes with government forces and African Union (AU) troops in Mogadishu.

A witness told Human Rights Watch that children of all ages could be seen on the front lines during these intense periods of fighting.[70] Children too small to carry large firearms, such as AK-47s, were given pistols and smaller weapons, as well as grenades to throw.[71] A 21-year-old fighter described such a scene: “We would fight early in the morning. I saw small kids, maybe 10 or 11 years old, with pistols, and those who could carry got AK-47s, and a lot of kids between 10 and 18 years old were given whips.”[72]

Before going into battle children were often lectured and encouraged to fight to the death. Al-Shabaab continued to use the promise of martyrdom, as was described to Human Rights Watch by 14-year-old Ali F.:

I participated in a fight. They told me that if I died there, I was going to become a martyr. We were lectured for four to five hours on religion and told not be cowards. There were about a hundred of us in the camp and 20 of us were under 18. The youngest was between eight and ten years old. The smaller ones were taught how to use a pistol and how to throw grenades. They also used them as suicide bombers. They said, “If you participate in suicide bombings you will become a martyr.” They said, “A martyr is rewarded by going to paradise.”[73]

Omar A., 18, described what happened when he was sent to the front lines at age 17:

In the camp there were some previous trainees and they took them to fight in battle and only half came back…. They told us, “You will go and fight for two days and then come back to the camp”…. The place was just before [outside of] Mogadishu, just on the outskirts. They gave us automatic weapons [AK-47s]. As we were driving in, the fighting started. They dropped us and started to fight. We could not see them. There were 15 of us and immediately 10 of us were shot. I dropped my gun and I ran. The ones who were shot were 15, 18, and 19 years old. They were all injured. Al-Shabaab leaves the wounded and they leave and they continue fighting.[74]

Media reports also describe children’s bodies being seen on the battlefields.[75]

A number of children explained to Human Rights Watch that they were sent to the front lines with experienced al-Shabaab fighters behind them using the children as a kind of “human shield.”[76]

Abdikarim K., 15, told Human Rights Watch:

Then they took us to fight. It was between al-Shabaab and the TFG. The fighting started at about 5 a.m. All the young children were taken to the first row of the fighting. I was there. We were defeated. Several of the young children there were killed, including several of my classmates. Out of all my classmates—about 100 boys—only two of us escaped, the rest were killed. Other children were also there on the front lines, about 300. The children were cleaned off. The children all died and the bigger soldiers ran away.[77]

Another 15-year-old boy, Iskinder P., said:

When the two months of training were over, there was a fight between al-Shabaab and the Marehan Clan. Al-Shabaab said it needed 300 fighters and I was among them. We were on the front lines. The heads always stayed behind us. Sometimes when I was firing the gun I would avoid shooting people and the person behind me would hit me.

I have seen someone shot in the head. His brain went all over. I was really shocked, mentally upset. They saw me turning my gun off and on, very upset. Someone said, “This boy is not normal,” and helped me into a vehicle. They took the gun from me. I was shocked and crying.[78]

Besides actually fighting, children, including girls, are also used to serve in a multitude of support roles during combat, including carrying bullets, water, milk, and food to the front lines, and bodies and wounded fighters from the battlefield.[79] Some of these activities, such as carrying ammunition during battle, would be considered direct participation in hostilities under international humanitarian law, making them liable to attack.[80]

A 14-year-old boy described his experience:

You go in a “technical” [a civilian vehicle mounted with anti-aircraft gun] when they take you to war. We were just helping to carry bullets. They show you your partner who carries the weapon and you go with him. We were trained how to carry bullets, how to be on the front lines. You stay with them; you sleep with them … up to five days, but usually two days. I used to see wounds and even I had seen someone shot. Sometimes boys were wounded and killed.

Sometimes when they pulled back we would run and give them water. When the fighting would start we would run back and we would pull the wounded and dead bodies to the vehicle. We used to carry and wash the bodies and help bury them.[81]

Ridwan R., 10, also said he supported fighters on the battlefield:

Strong children were asked to carry injured fighters. I went with them.… Sometimes I was collecting the wounded, sometimes serving food…. I saw some 7-year-olds. When I talked to them they told me they were used as a shield. They had bullet wounds and metal in their body.[82]

Suicide Bombers

The youngest [in the camp] was between eight and ten years old. The smaller ones were taught how to use pistols and how to throw grenades. Al-Shabaab also used them as suicide bombers. I saw these kids hurling grenades. I heard them talking about suicide bombings. They said, “If you participate in suicide bombings you will become a martyr.” We were told not to discuss this issue with adults as they would discourage us. The ones who talked to us about it had their faces covered. They said, “A martyr is rewarded by going to paradise.”

—Yusuuf J. (not his real name), 16-year-old boy forcibly recruited in Mogadishu in 2010, June 3, 2011

In addition to using children in its more conventional combat operations, al-Shabaab has also used children as suicide bombers. Al-Shabaab’s use of suicide bombers to target TFG ministers and installations as well as AU peacekeepers has been documented in various media reports.[83] Human Rights Watch interviewed one young man who was used in an attempted suicide bombing near an AMISOM base in February 2011 when he was 17 years old, and a teacher who witnessed the killing of eight students when an eleven-year-old suicide bomber disguised as a food vendor detonated explosives on the school grounds in October 2009.[84]

Al-Shabaab seeks out children for use in suicide missions in training camps, and in primary schools. Four children told Human Rights Watch that they saw other children, being prepared and sometimes taken from the training camps to become suicide bombers.[85] This fear of being forced to carry out suicide bombings drove some to make dangerous and often life-threatening attempts to escape. The consequences for failing to carry out a suicide bombing or trying to escape, however, were grave.

Feysal M., who was 12 when al-Shabaab took him with his classmates from school in early 2011, said that al-Shabaab executed some of the boys because they refused to become suicide bombers: “Some of the boys had parents in the TFG so al-Shabaab wanted to use them as suicide bombers. So they gave them a choice to be killed or explode themselves. So they said, ‘Either way we die so just kill us so we don’t kill others.’” Feysal said he was with the boys when al-Shabaab gave them the choice: “I saw them with their hands bound, taken to the bush.” He said he was ordered to watch the execution but he refused: “One was my close cousin…. I didn’t want to see my cousin and my friends butchered. So they started whipping me with a shamut [whip]. Later I was forced to see the bodies. I ran out of words I was so shocked and terrified…. When I remember it, it’s hell.”[86]

The Story of an Escaped Child Suicide BomberA 17-year-old boy, fleeing from a suicide bombing mission in Mogadishu, told Human Rights Watch: In February 2011, I was in Dhobley [near the Kenyan Border]. I was recruited by al-Shabaab and taken back to Medina. The job I was given was a suicide bomber or to place bombs. There were eight of us selected for suicide bombings. I was so scared. I knew I was going to take my life. The eight of us were divided into four groups of two. Each day two would go and bomb. The others were between 18 and 20 years old. They trained us how to drive and gave other training for 10 days. The trainer was Pakistani, but his face was covered. The first group of two was taken to the livestock market, to a TFG office, and six remained. Next were me and Ali [not his real name], who was 19 years old. We were sent to a place called Kilometer 4 near the AMISOM base. We were given a Toyota Prado [automobile]. There were other vehicles sent to follow us to see that we did the job. We parked and decided to disappear and flee. We didn’t know al-Shabaab were following us. We were meant to take a specific route but we turned off on a side road. Then there were four vehicles which barricaded us in. They asked why we turned off and then started to beat us with the butt of their guns. There were six al-Shabaab beating us. We were arrested by al-Shabaab and taken to a cell in Medina, Bulaqaraa. It was where the top officials were who would decide our fate. It is the place that in 2008 AMISOM was hosted. They had discussions for four or five days. On the sixth day an official said that we had betrayed al-Shabaab and that we were TFG spies and that we should be killed. We were told that tomorrow at 8 a.m. we would be taken from our cell and would face the knife. We were given cell phones to call our parents and say that we will be killed the following day. My partner’s father was with the TFG, but he was not from Medina, but I knew everyone in Medina. My colleague was given a phone and called his father and explained. It was a short conversation. He handed the phone to me and I didn’t know who to call … my mother, father, or brother. My mother was in Medina at the time, so I phoned my brother. Al-Shabaab arrested him twice. My brother went to the clan elders. The elders came and pleaded with al-Shabaab to release us but they refused. It was on the second day of talks that a guy said we had four hours left and then we would be taken to the killing area. We pleaded and explained we had not done anything. This man showed us the way out. I listened to his instructions and the other boy didn’t believe it was true—he thought it was a trap. For me it was do or die, so I tried to escape. My friend stayed behind. I thought the worst case was we will both be dead … but best case, I escape. I followed the escape route. I was lucky. —Tahlil D. (not his real name), Kenya, June 2, 2011 |

Role of Girls

Al-Shabaab has frequently taken girls for cooking, cleaning, and other support roles, as well as for rape and forced marriage. Girls and other eyewitnesses told Human Rights Watch that al-Shabaab has targeted girls on the street, at schools, and en route to school, and taken them directly from their homes. This section addresses al-Shabaab’s use of girls to provide support for the fighters. Rape and forced marriage are discussed in a later section.

As described in interviews, the girls and young women targeted ranged in age from around 11 to the early 20s.[87] Girls were often abducted in the same sweeps as boys. A 10-year-old boy from Mogadishu taken by al-Shabaab in late 2010 described how he was abducted along with a group of schoolmates that included girls, en route from school:

We were coming from school with our friends. Al-Shabaab pulled up and dragged us to their vehicle. They had covered heads and faces but they weren’t in uniform. Many children were taken, even girls. They said, “The girls will cook for us, the small boys we’ll send to the markets and the bigger boys will fight.” They took us to a place that looked like the bush. They took the girls to a different place and we didn’t see them after that.”[88]

Similarly, girls are taken from school. A 15-year-old boy from Al Abadir primary school in Mogadishu recounted one incident during Ramadan 2010: “They [al-Shabaab] moved from class to class and took students aged 14, 16, 18, both boys and girls. They took eight girls and fifteen boys. The girls were to cook and carry water to fighters.”[89]

Human Rights Watch interviewed five girls between the ages of 11 and 22 who described the differing roles girls were forced to play in the training camps. These included “being made to clean, cook, and wash their [al-Shabaab’s] clothes.”[90]

Boys and men who had been in training camps said that they regularly saw girls brought to the camps. A 10-year-old boy held at a training camp on the outskirts of Mogadishu described girls in the camp cooking and serving food to fighters.[91] Similarly, a 20-year-old student recalled an incident in which he witnessed the arrival of a group of girls into the training camp where he was being he held. He said, “There were six girls. They had been taken from houses. They were locked in different rooms and we could hear them crying.”[92]

The girls we interviewed also described being kept locked in rooms or houses and only allowed out to work. While the girls we interviewed who were taken for domestic duties said they were not sexually assaulted at the camps, Human Rights Watch received several reports of violence against girls during their detention. As Farax K., 17, told Human Rights Watch:

We would wash their clothes and cook for them. They were not harassing us sexually, but they were beating us. They gave us only one set of clothes and it was very heavy. We used to cook and sometimes the girls would shed tears remembering their freedom. That’s when they would beat us with guns. One day they hit me so hard I fell on the ground.[93]

Girls who were taken to perform domestic duties often said they were kept for shorter periods of time than children recruited for combat training. The girls we interviewed told Human Rights Watch that they were taken for periods ranging from two days to two weeks, and then were released or escaped.[94]

Aamina M., 13, told Human Rights Watch how she and her friends escaped in 2010 after being held for three days by al-Shabaab:

Al-Shabaab went to eat and the girls forced the lock [on the door]. We pushed and pushed and then when it opened we ran away. When we ran, they saw us and opened fire. Four girls were caught by al-Shabaab and another 10 who had been fired upon, we think they got shot. One girl out of the four of us who [successfully] escaped knew the route well and she got us to Medina.[95]

Fear of Re-Recruitment

If children manage to escape from al-Shabaab forces, they remain at risk. Children told us they feared re-recruitment and would hide in remote areas or other towns waiting to flee to Kenya.[96] Other children who escaped from al-Shabaab and managed to return home said they were too fearful to go outside. As 16-year-old Maahir D. explained after his escape from a training camp: “I was scared to be recaptured as the trainers in the camp told us we would be killed if we tried to escape…. I stayed home for 15 days, never leaving the house, and then I travelled to Dhobley.”[97] Another 14-year-old boy described a similar experience of confining himself to his home for three months in order to protect himself from re-recruitment.[98]

The risk of reprisal for escaping was genuine and not only limited to the children themselves. In several cases children’s family members who had remained behind in Somalia were threatened and some killed as al-Shabaab forced the family to inform them of the whereabouts of the child who escaped.

Ibrahim K. of Baidoa, northwest of Mogadishu, told Human Rights Watch that after hiding from al-Shabaab, he returned home to see his family to find that al-Shabaab had gone there to look for him:

They went to my house to my parents and said, “We want your child.” My parents refused. They killed my parents, my four brothers, and three of my four sisters. The girls were crying and then the other boys tried to defend my parents. Only my 10-year-old sister and I survived. I wasn’t there. I came and found my sister crying and the bodies only. My sister was crying and saying, “Go away. They will kill you and I can’t live alone if they kill you.” I just got my sister and fled…. We left the bodies and my sister and I ran away.[99]

Similarly, a 13-year-old boy who was recruited by al-Shabaab in 2011 described how, following his escape from the training camp, al-Shabaab came looking for him: “Al-Shabaab came looking for us at home. My father was asked to bring me. He said he didn’t know where I was. There was a scuffle and they shot my father dead.… With that I decided to go to Kenya. It’s painful that my father died.”[100]

Al-Shabaab’s relentless campaign against children has contributed to many families and children on their own seeking refuge in neighboring Kenya or in other towns across Somalia. Many children and their relatives told Human Rights Watch that fears of recruitment or re-recruitment were one of the primary reasons they fled. Children described being “afraid” and “haunted” by what al-Shabaab had done and found leaving Somalia their only remaining option.[101]

However, even escape to Kenya does not end the children’s fear of re-recruitment or abduction.[102] In Kenya both parents and children described daily fear of the children being seen and taken by al-Shabaab. Parents and children told Human Rights Watch that they felt al-Shabaab had the ability to continue to look for them.[103] A number of interviewees said that al-Shabaab continued to have a presence in Kenya and in the camps in Dadaab.[104] Iskinder P., 15, said: “I am relieved [to be in Kenya] but I am afraid they might come for me here and return me there.”[105] Other children described bumping into al-Shabaab members they had met in their trainings in Kenya and feared direct recruitment upon being recognized, only compounding the constant sense of fear which sometimes stopped them from moving freely.

Children in TFG Forces and in TFG Custody

The TFG officially does not recruit children under the age of 18 into its security forces. However, boys have continued to be found in TFG forces and those of TFG-affiliated militias. While the TFG is not known to forcibly recruit children, it lacks systematic and stringent screening procedures and standards to determine the age of all its recruits and thus ensure children are excluded. The TFG security forces continue to lack formal command and control mechanisms and are, instead, made up of an array of groups, including allied militia and militia linked to TFG officials that are recruited and integrated in different ways. While recruits for TFG forces who undergo EU-funded training in Uganda are formally screened for age by several actors, recruits who are not trained in Uganda or who have been directly recruited from militias typically have not been. Somalia’s Transitional Federal Charter 128 of February 2004 contains an explicit prohibition on the use of children under 18 years of age for military service.[106] In meeting its obligations under international law, the TFG has a positive duty to ensure that all its military units or militias under its control prohibit the recruitment and use of children in fighting forces under the age of 15. To avoid complicity in violations, the TFG cannot allow allied militias to use children under 15.

Use of Children by the TFG and TFG-aligned Militias

The presence of children within the TFG forces, TFG militias, and its allied militias continues to be reported. The UN secretary-general in his April 2011 annual report to the Security Council on children and armed conflict listed the TFG as responsible for the recruitment and use of child soldiers.[107] While Human Rights Watch interviewed only one child who had himself been recruited and served under the TFG, we spoke to several people with firsthand knowledge of children joining TFG forces in 2010. For example, one former Hizbul Islam fighter whose militia group later joined the TFG said he saw children as young as 13 in TFG forces in 2010: “There are children in the TFG, aged 13 to 15 years. There were 80 to 90 in my group of 300 who were between 13 and 16 years old.”[108]

Similarly, Yusri A., a 21-year-old man from Mogadishu, said two of his friends, aged 16, joined the TFG: “I have many friends who have joined the TFG and many of them were under 18. Some are soldiers guarding the presidential palace and some participate in the fighting.”[109]

Neither children nor their families interviewed expressed concerns about forced recruitment of children by the TFG. “I have never heard of the TFG [forcibly] recruiting children,” said an 18-year-old young man from Suuqa Xoola in Mogadishu who knew several boys who had voluntarily joined the TFG forces.[110]

Instead, enlisting by children into the TFG forces appears to be a means of survival. Interviewees spoke to Human Rights Watch of children—classmates, friends, or relatives—joining the TFG in order to earn money and provide for their families. The desire to seek revenge against al-Shabaab for abuses committed against their families also influenced children’s decision to enlist. More vulnerable groups of children who are without care and protection, such as orphans, appear particularly likely to join the TFG. For example, the 21-year-old above said of his underage friends: “They were hungry and were orphans so they joined the TFG. Others who joined were just angry against al-Shabaab. I spoke to them and they told me they have nowhere else to go. The TFG supported them.”[111]

A 15-year-old from El Ashabiya described how boys also joined the TFG in order to escape recruitment from al-Shabaab: