On January 23, 2024, Human Rights Watch, Social Media Exchange (SMEX), INSM Foundation for Digital Rights, Helem, and Damj Association, launched the “Secure Our Socials” campaign engaging Meta (Facebook, Instagram) to be more transparent and accountable in protecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region from online targeting by state actors and private individuals on its platforms.

In February 2023, Human Rights Watch published a report on the digital targeting of LGBT people in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia, and its offline consequences. The report details how government officials across the MENA region are targeting LGBT people based on their online activity on social media, including on Meta platforms. Security forces have entrapped LGBT people on social media and dating applications, subjected them to online extortion, online harassment, doxxing, and outing; and relied on illegitimately obtained digital photos, chats, and similar information in prosecutions. In cases of online harassment, which took place predominantly in public posts on Facebook and Instagram, affected individuals faced offline consequences, which often contributed to ruining their lives.

As a follow up to the report and based on its recommendations, including to Meta, the “Secure Our Socials” campaign identifies ongoing issues of concern, and aims to engage Meta platforms, particularly Facebook and Instagram, to publish meaningful data on investment in user safety, including regarding content moderation in the MENA region, and around the world.

On January 8, 2024, Human Rights Watch sent an official letter to Meta to inform relevant staff of the campaign and its objectives, and to solicit Meta’s perspective. Meta responded to the letter on January 24.

2. What is the “Secure Our Socials” campaign by HRW and partners calling on Meta to change?

3. What are Meta’s human rights responsibilities in reducing abuses on its platforms?

5. How does Meta generally decide what content to remove from its platforms?

6. How is Meta’s content moderation falling short for LGBT people in the MENA region?

7. How does Meta address entrapment and “fake” accounts targeting LGBT people on its platforms?

8. What is happening on other platforms and why is this campaign focusing on Meta?

9. How should governments better protect LGBT people online and offline?

10. What can you do to support?

Social media platforms can provide a vital medium for communication and empowerment. At the same time, LGBT people around the world face disproportionately high levels of online abuse. Particularly in the MENA region, LGBT people and groups advocating for LGBT rights have relied on digital platforms for empowerment, access to information, movement building, and networking. In contexts in which governments prohibit LGBT groups from operating, organizing by activists to expose anti-LGBT violence and discrimination has mainly happened online. While digital platforms have offered an efficient and accessible way to appeal to public opinion and expose rights violations, enabling LGBT people to express themselves and amplify their voices, they have also become tools for state-sponsored repression.

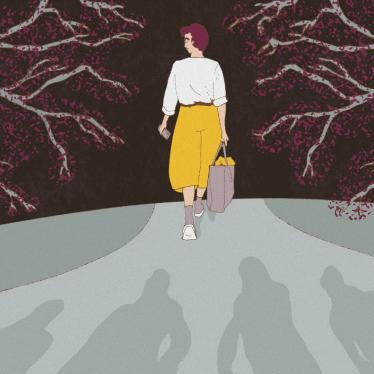

Building on research by Article 19, Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), Association for Progressive Communication (APC), and others, Human Rights Watch has documented how state actors and private individuals have been targeting LGBT people in the MENA region based on their online activity, in blatant violation of their right to privacy and other human rights. Across the region, authorities manually monitor social media, create fake profiles to impersonate LGBT people, unlawfully search LGBT people’s personal devices, and rely on illegitimately obtained digital photos, chats, and similar information taken from LGBT people’s mobile devices and social media accounts as “evidence” to arrest and prosecute them.

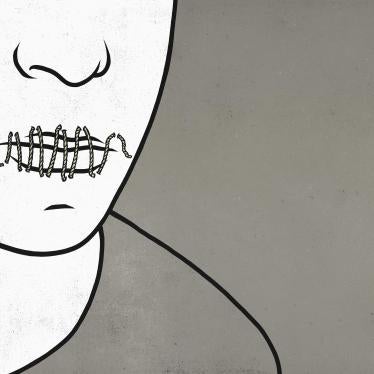

LGBT people and activists in the MENA region have experienced online entrapment, extortion, doxxing, outing, and online harassment, including threats of murder, rape, and other physical violence. Law enforcement officials play a central role in these abuses, at times initiating online harassment campaigns by posting photos and contact information of LGBT people on social media and inciting violence against them.

Digital targeting of LGBT people in the MENA region has had far-reaching offline consequences that did not end in the instance of online abuse, but reverberated throughout affected individuals’ lives, in some cases for years. The immediate offline consequences of digital targeting range from arbitrary arrest to torture and other ill-treatment in detention, including sexual assault.

Digital targeting has also had a significant chilling effect on LGBT expression. After they were targeted, LGBT people began practicing self-censorship online, including in their choice of digital platforms and how they use those platforms. Those who cannot or do not wish to hide their identities, or whose identities are revealed without their consent, reported suffering immediate consequences ranging from online harassment to arbitrary arrest and prosecution.

As a result of online harassment, LGBT people in the MENA region have reported losing their jobs, being subjected to family violence including conversion practices, being extorted based on online interactions, being forced to change their residence and phone numbers, delete their social media accounts, or flee their country of residence, and suffering severe mental health consequences.

Meta is the largest social media company in the world. It has a responsibility to safeguard its users against the misuse of its platforms. Facebook and Instagram, in particular, are significant vehicles for state actors’ and private individuals’ targeting of LGBT people in the MENA region. More consistent enforcement and improvement of its policies and practices can make digital targeting more difficult and, by extension, make all users, including LGBT people in the MENA region, safer.

With the “Secure Our Socials” campaign, Human Rights Watch and partners are calling on Meta to be more transparent and consistent in its content moderation practices and to embed the human rights of LGBT people at the core of its platform design. In doing so, the campaign reinforces other efforts to make social media platforms and tech companies more accountable and respect the human rights of their users, such as the Santa Clara Principles on Transparency and Accountability in Content Moderation, Digital Action’s “Year of Democracy” campaign, and Afsaneh Rigot’s “Design from the Margins” framework. The campaign has also received invaluable input from a range of civil society groups.

As an initial step toward transparency, the “Secure Our Socials” campaign asks Meta to disclose its annual investment in user safety and security including reasoned justifications explaining how trust and safety investments are proportionate to the risk of harm, for each MENA region language and dialect. We specifically inquire about the number, diversity, regional expertise, political independence, training qualifications, and relevant language (including dialect) proficiency of staff or contractors tasked with moderating content originating from the MENA region, and request that this information be made public.

Meta frequently relies on contractors and subcontractors to moderate content, and it is equally important for Meta to be transparent about these arrangements.

Outsourcing content moderation should not come at the expense of working conditions. Meta should publish data on its investment in safe and fair working conditions for content moderators (regardless of whether they are staff, contractors, or sub-contractors), including psychosocial support; as well as data on content moderators’ adherence to nondiscrimination policies, including around sexual orientation and gender identity. Publicly ensuring adequate resourcing of content moderators is an important step toward improving Meta’s ability to accurately identify content targeting LGBT people on its platforms.

We also urge Meta to detail what automated tools are being used in its content moderation for each non-English language and dialect (prioritizing Arabic), including what training data and models are used and how each model is reviewed and updated over time. Meta should also publish information regarding precisely when and how automated tools are used to assess content, including details regarding the frequency and impact of human oversight. In addition, we urge Meta to conduct and publish an independent audit of any language models and automated content analysis tools being applied to each dialect of the Arabic language, and other languages in the MENA region for their relative accuracy and adequacy in addressing the human rights impacts on LGBT people where they are at heightened risk. To do so, Meta should engage in deep and regular consultation with independent human rights groups to identify gaps in its practices that leave LGBT people at risk.

Meta’s over-reliance on automation when assessing content and complaints also undermines its ability to moderate content in a manner that is transparent and lacking bias. Meta should develop a rapid response mechanism to ensure LGBT-specific complaints [in high-risk regions] are reviewed by a human with regional, subject matter, and linguistic expertise, in a timely manner. Meta’s safety practices can do more to make its platforms less prone to abuse of LGBT people in the MENA region. Public disclosures have shown that Meta has frequently failed to invest enough resources into its safety practices, sometimes rejecting internal calls for greater investment in regional content moderation even at times of clear and unequivocal risk to its users.

In the medium term, Human Rights Watch and its partners call on Meta to audit the adequacy of existing safety measures and continue to engage with civil society groups to carry out gap analyses on existing content moderation and safety practices. Finally, regarding safety features and based on uniform requests by affected individuals, we recommend that Meta implement a one-step account lockdown tool of user accounts, allow users to hide their contact lists, and introduce a mechanism to remotely wipe all Meta content and accounts (including from WhatsApp and Threads) on a given device.

Some of the threats faced by LGBT people in the MENA region require thoughtful and creative solutions, particularly where law enforcement agents are actively using Meta’s platforms as a targeting tool. Meta should dedicate resources towards research and engagement with LGBT and digital rights groups in the MENA region, for example, by implementing the “Design from the Margins” (DFM) framework developed by Afsaneh Rigot, a digital rights researcher and advocate. Only with a sustained commitment to actively centering the experiences of those most impacted in all its design processes, can Meta truly reduce the risks and harms faced by LGBT people on its platforms.

Under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, social media companies, including Meta, have a responsibility to respect human rights – including the rights to nondiscrimination, privacy, and freedom of expression – on their platforms. They are required to avoid infringing on human rights, and to identify and address human rights impacts arising from their services including by providing meaningful access to remedies and to communicate how they are addressing these impacts.

When moderating content on its platforms, Meta’s responsibilities include taking steps to ensure its policies and practices are transparent, accountable, and applied in a consistent and nondiscriminatory manner. Meta is also responsible for mitigating the human rights violations perpetrated against LGBT people on its platforms while respecting the right to freedom of expression.

The Santa Clara Principles on Transparency and Accountability in Content Moderation provide useful guidance for companies to achieve their responsibilities. These include the need for integrating human rights and due process considerations at all levels of content moderation, comprehensible and precise rules regarding content-related decisions, and the need for cultural competence. The Santa Clara Principles also specifically require transparency regarding the use of automated tools in decisions that impact the availability of content and call for human oversight of automated decisions.

Human rights also protect against unauthorized access to personal data, and platforms should therefore also take steps to secure people’s accounts and data against unauthorized access and compromise.

The Secure Our Socials campaign recommendations are aimed at improving Meta’s ability to meet its human rights responsibilities. In developing and applying content moderation policies, Meta should also reflect and take into account the specific ways people experience discrimination and marginalization, including the experiences of LGBT people in the MENA region. These experiences should drive product design, including through the prioritization of safety features.

Regarding human rights due diligence, Human Rights Watch and its partners also recommend that Meta conduct periodic human rights impact assessments in particular countries or regional contexts, dedicating adequate time and resources into engaging rights holders.

Many forms of online harassment faced by LGBT people on Facebook and Instagram are prohibited by Meta’s Community Standards, which place limits on bullying and harassment, and indicate that the platform will “remove content that is meant to degrade or shame” private individuals including “claims about someone’s sexual activity,” and protect private individuals against claims about their sexual orientation and gender identity, including outing of LGBT people. Meta’s community standards also prohibit some forms of doxxing, such as posting people’s private phone numbers and home addresses, particularly when weaponized for malicious purposes.

Due to shortcomings in its content moderation practices, including over-enforcement in certain contexts and under-enforcement in others, Meta often struggles to apply these prohibitions in a manner that is transparent, accountable, and consistent. As a result, harmful content sometimes remains on Meta platforms even when it contributes to detrimental offline consequences for LGBT people and violates Meta’s policies. On the other hand, Meta disproportionately censors, removes, or restricts non-violative content, silencing political dissent or voices documenting and raising awareness about human rights abuses on Facebook and Instagram. For example, Human Rights Watch published a report in December 2023 documenting Meta’s censorship of pro-Palestine content on Instagram and Facebook.

Meta’s approach to content moderation on its platforms involves a combination of proactive and complaint-driven measures. Automation plays a central role in both sets of measures and is often relied upon heavily to justify under-investment in content moderators. The result is that content moderation outcomes frequently fail to align with Meta’s policies, often leaving the same groups of people both harassed and censored.

Procedurally, individuals and organizations can report content on Facebook and Instagram that they believe violates Community Standards or Guidelines, and request that the content be removed or restricted. Following Meta’s decision, the complainant, or the person whose content was removed, can usually request that Meta review the decision. If Meta upholds its decision for a second time, the user can sometimes appeal the platform’s decision to Meta’s Oversight Board, but the Board only accepts a limited amount of cases.

Meta relies on automation to detect and remove content deemed violative by the relevant platform and recurring violative content, regardless of complaints, as well as in processing existing complaints and appeals where applicable.

Meta does not publish data on automation error rates or statistics on the degree to which automation plays a role in processing complaints and appeals. Meta’s lack of transparency hinders independent human rights and other researchers’ ability to hold its platforms accountable, allowing wrongful content takedowns as well as inefficient moderation processes for violative content, especially in non-English languages, to remain unchecked.

In its 2023 digital targeting report, Human Rights Watch interviewed LGBT people in the MENA region who reported complaining about online harassment and abusive content to Facebook and Instagram. In all these cases, platforms did not remove the content, claiming it did not violate Community Standards or Guidelines. Such content, reviewed by Human Rights Watch, included outing, doxxing, and death threats, which resulted in severe offline consequences for LGBT people. Not only did automation fail to detect this content, but even when it was reported, the automation was ineffective in removing harmful content. As a result, it barred LGBT people who complained and their requests were denied from access to an effective remedy, the timeliness of which could have limited offline harm.

Human Rights Watch has also documented, in another 2023 report, the disproportionate removal of non-violative content in support of Palestine on Instagram and Facebook, often restricted through automation processes before it appears on the platform, a process that has contributed to the censorship of peaceful expression at a critical time.

Meta also moderates content in compliance with government requests it receives for content removal on Facebook and Instagram. While some government requests flag content contrary to national laws, other requests for content removal lack a legal basis and rely instead on alleged violations of Meta’s policies. Informal government requests can exert significant pressure on companies, and can result in silencing political dissent.

Meta’s insufficient investment in human content moderators and its over-reliance on automation undermine its ability to address content on its platform. Content targeting LGBT people is not always removed in an expeditious manner even where it violates Meta’s policies, whereas content intended by LGBT people to be empowering can be improperly censored, compounding the serious restrictions LGBT people in the MENA region already face.

As the “Secure Our Socials” campaign details, effective content moderation requires an understanding of regional, linguistic, and subject matter context.

Human content moderators at Meta can also misunderstand important context when moderating content. For example, Instagram removed a post of an array of Arabic terms labelled as “hate speech” targeting LGBT people by multiple moderators who failed to recognize the post was being used in a self-referential and empowering way to raise awareness. One major contributing factor to these errors was Meta’s inadequate training and a failure to translate its English-language training manuals into Arabic dialects.

In 2021, LGBT activists in the MENA region developed the Arabic Queer Hate Speech Lexicon, which identifies and contextualizes hate speech terms through a collaborative project between activists in seventeen countries in the MENA region. The lexicon includes hate speech terms in multiple Arabic dialects, is in both Arabic and English, and is a living document that activists aim to update periodically. To better detect anti-LGBT hate speech in Arabic, as well as remedy adverse human rights impacts, Meta could benefit from the lexicon as a guide for its internal list of hate speech terms and should actively engage LGBT and digital rights activists in the MENA region to ensure that terms are contextualized.

Meta relies heavily on automation to proactively identify content that violates its policies and to assess content complaints from users. Automated content assessment tools frequently fail to grasp critical contextual factors necessary to comprehend content, significantly undermining Meta’s ability to assess content. For example, Meta’s automated systems rejected, without any human involvement, ten out of twelve complaints and two out of three appeals against a recent post calling for death by suicide of transgender people, even though Meta’s Bullying and Harassment policy prohibits “calls for self-injury or suicide of a specific person or groups of individuals.”

Automated systems also face unique challenges when attempting to moderate non-English content and have been shown to struggle with moderating content in Arabic dialects. One underlying problem is that the same Arabic word or phrase can mean something entirely different depending on the region, context, or dialect being used. But language models used to automate content moderation will often rely on more common or formal variants to “learn” Arabic, greatly undermining their ability to understand content in Arabic dialects. Meta recently committed to examining dialect-specific automation tools, but it continues to rely heavily on automation while these tools are being developed and has not committed to any criteria to ensure the adequacy of these new tools prior to their adoption.

Meta’s policies prohibit the use of its Facebook and Instagram platforms for surveillance, including for law enforcement and national security purposes. This prohibition includes fake accounts created by law enforcement to investigate users, and applies to government officials in the MENA region that would entrap LGBT people. Accounts reported for entrapment could be deactivated or deleted, and Meta has initiated legal action against systemic misuses of its platform, including for police surveillance purposes.

However, Meta’s prohibition against the use of fake accounts has not been applied in a manner that pays adequate attention to the human rights impacts of people who face heightened marginalization in society. In fact, the fake account prohibition has been used against LGBT people. False reporting of accounts on Facebook for using fake names has been used in online harassment campaigns; unlike Facebook, Instagram does not prohibit the use of pseudonyms. Facebook’s aggressive enforcement of its real name policy has also historically led to the removal of LGBT Facebook accounts using pseudonyms to shield themselves from discrimination, harassment, or worse. Investigations into the authenticity of pseudonymous accounts can also disproportionately undermine the privacy of LGBT people.

The problems that Human Rights Watch and its partners hope to address in this campaign do not only occur on Meta’s platforms. Law enforcement agents and private individuals use fake accounts to entrap LGBT people on dating apps such as Grindr and WhosHere.

Before publishing its February report, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to Grindr, to which Grindr responded extensively in writing, acknowledging our concerns and addressing gaps. While we also sent a letter to Meta in February, we did not receive a written response.

Online harassment, doxxing, and outing are also prevalent on other social media platforms such as X (formerly known as Twitter). X’s approach to safety on its platform has come under criticism in recent years, as its safety and integrity teams faced significant staffing cuts on several occasions.

Meta continues to operate the largest social media company in the world, and its platforms have substantial reach. Additionally, Meta’s platforms cover a range of services, ranging from public posts to private messaging. Improving Meta’s practices would have significant impact and serve as a useful point of departure for a broader engagement with other platforms around digital targeting of LGBT people in the MENA region.

The targeting of LGBT people online is enabled by their legal precarity offline. Many countries, including in the MENA region, outlaw same-sex relations or criminalize forms of gender expression. The criminalization of same-sex conduct or, where same-sex conduct is not criminalized, the application of vague “morality” and “debauchery” provisions against LGBT people emboldens digital targeting, quells LGBT expression online and offline, and serves as the basis for prosecutions of LGBT people.

In recent years, many MENA region governments, including Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia, have introduced cybercrime laws that target dissent and undermine the rights to freedom of expression and privacy. Governments have used cybercrime laws to target and arrest LGBT people, and to block access to same-sex dating apps. In the absence of legislation protecting LGBT people from discrimination online and offline, both security forces and private individuals have been able to target them online with impunity.

Governments in the MENA region are also failing to hold private actors to account for their digital targeting of LGBT people. LGBT people often do not report crimes against them to the authorities, either because of previous attempts in which the complaint was dismissed or no action was taken, or because they reasonably believed they would be blamed for the crime due to their non-conforming sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression. Human Rights Watch documented cases where LGBT people who reported being extorted to the authorities ended up getting arrested themselves.

Governments should respect and protect the rights of LGBT people instead of criminalizing their expression and targeting them online. The five governments covered in Human Rights Watch’s digital targeting report should introduce and implement legislation protecting against discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity, including online.

Security forces, in particular, should stop harassing and arresting LGBT people on the basis of their sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression and instead ensure protection from violence. They should also cease the improper and abusive gathering or fabrication of private digital information to support the prosecution of LGBT people. Finally, the governments should ensure that all perpetrators of digital targeting – and not the LGBT victims themselves – are held responsible for their crimes.

Spread the word about potential harms for LGBT users on social media platforms and the need for action.

The #SecureOurSocials campaign is calling on Meta platforms, Facebook, and Instagram, to be more accountable and transparent on content moderation and user safety by publishing meaningful data on its investment in user safety, including content moderation, and to adopt some additional safety features.

You can take action now. Email Facebook President of Global Affairs Nick Clegg and Vice President of Content Policy Monika Bickert to act on user safety.