Map

Summary

The hardest of all the crops we’ve worked in is tobacco. You get tired. It takes the energy out of you. You get sick, but then you have to go right back to the tobacco the next day.

—Dario A., 16-year-old tobacco worker in Kentucky, September 2013

I would barely eat anything because I wouldn’t get hungry. …Sometimes I felt like I needed to throw up. …I felt like I was going to faint. I would stop and just hold myself up with the tobacco plant.

—Elena G., 13-year-old tobacco worker in North Carolina, May 2013

Children working on tobacco farms in the United States are exposed to nicotine, toxic pesticides, and other dangers. Child tobacco workers often labor 50 or 60 hours a week in extreme heat, use dangerous tools and machinery, lift heavy loads, and climb into the rafters of barns several stories tall, risking serious injuries and falls. The tobacco grown on US farms is purchased by the largest tobacco companies in the world.

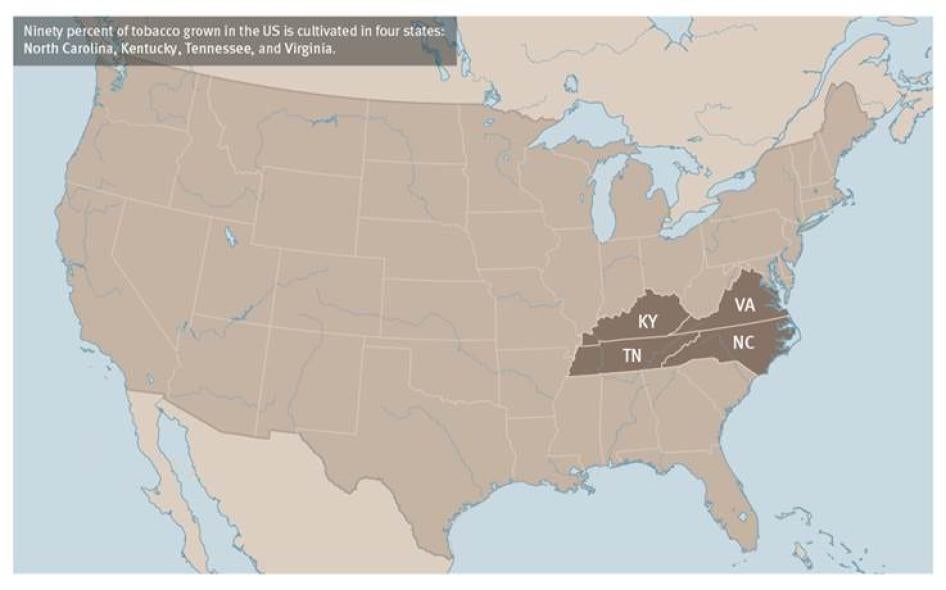

Ninety percent of tobacco grown in the US is cultivated in four states: North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. Between May and October 2013, Human Rights Watch interviewed 141 child tobacco workers, ages 7 to 17, who worked in these states in 2012 or 2013. Nearly three-quarters of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported the sudden onset of serious symptoms—including nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, headaches, dizziness, skin rashes, difficulty breathing, and irritation to their eyes and mouths—while working in fields of tobacco plants and in barns with dried tobacco leaves and tobacco dust. Many of these symptoms are consistent with acute nicotine poisoning.

Based on our findings set out in this report, Human Rights Watch believes that no child under age 18 should be permitted to perform work in which they come into direct contact with tobacco in any form, including plants of any size or dried tobacco leaves, due to the inherent health risks posed by nicotine and the pesticides applied to the crop. The US government, US Congress, and tobacco manufacturing and tobacco leaf supply companies should all take urgent steps to progressively remove children from such tasks in tobacco farming.

In the US, it is illegal for children under 18 to buy cigarettes or other tobacco products. However, US law fails to recognize the risks to children of working in tobacco farming. It also does not provide the same protections to children working in agriculture as it does to children working in all other sectors. In agriculture, children as young as 12 can legally work for hire for unlimited hours outside of school on a tobacco farm of any size with parental permission, and employers may hire children younger than 12 to work on small farms with written parental consent. Outside of agriculture, the employment of children under 14 is prohibited, and even 14 and 15-year-olds can only work in certain jobs for a limited number of hours each day.

Tobacco farmed in the US enters the supply chains of at least eight major manufacturers of tobacco products who either purchase tobacco through direct contracts with tobacco growers or through tobacco leaf supply companies. These include Altria Group, British American Tobacco, China National Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco Group, Japan Tobacco Group, Lorillard, Philip Morris International, and Reynolds American. Some of these companies manufacture the most popular brands of cigarettes sold in the US, including Marlboro, Newport, Camel, and Pall Mall. All companies that purchase tobacco in the US directly or indirectly have responsibilities to ensure protection of children from hazardous labor, including on tobacco farms, in their supply chains in the US and globally.

Child tobacco workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report typically described beginning to work on tobacco farms at age 13, often together with their parents and older siblings. Only very few worked on family farms. The children we interviewed were mostly the sons and daughters of Hispanic immigrants, though they themselves were frequently US citizens. Regardless of employment or immigration status, the children described working in tobacco to help support their families’ basic needs or to buy essential items such as clothing, shoes, and school supplies. For example, 15-year-old Grace S. told Human Rights Watch why she decided to start working in tobacco farming in North Carolina: “I just wanted to help out my mom, help her with the money.”

Most children interviewed by Human Rights Watch were seasonal workers who resided in states where tobacco was grown and worked on farms near their homes or in neighboring areas, primarily or exclusively during the summer months when tobacco is cultivated. We also spoke to several children who migrated to and within the United States by themselves or with their families to work in tobacco and other crops. There is no comprehensive estimate of the number of child farmworkers in the US.

Tobacco is a labor-intensive crop, and the children interviewed described participating in a range of tasks, including: planting seedlings, weeding, “topping” tobacco to remove flowers, removing nuisance leaves (called “suckers”), applying pesticides, harvesting tobacco leaves by hand or with machines, cutting tobacco plants with “tobacco knives” and loading them onto wooden sticks with sharp metal points, lifting sticks with several tobacco plants, hanging up and taking down sticks with tobacco plants in curing barns, and stripping and sorting dried tobacco leaves.

Health and Safety Risks in Tobacco Farming

Children interviewed by Human Rights Watch in North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia frequently described feeling seriously, acutely sick, while working in tobacco farming. For example, Carla P., 16, works for hire on tobacco farms in Kentucky with her parents and her younger sister. She told Human Rights Watch she got sick while pulling the tops off tobacco plants: “I didn’t feel well, but I still kept working. I started throwing up. I was throwing up for like 10 minutes, just what I ate. I took a break for a few hours, and then I went back to work.” Emilio R., a 16-year-old seasonal worker in eastern North Carolina, who plans to study to be an engineer, said he had headaches that sometimes lasted up to two days while working in tobacco: “With the headaches, it was hard to do anything at all. I didn’t want to move my head.”

Many of the symptoms reported by child tobacco workers are consistent with acute nicotine poisoning, known as Green Tobacco Sickness, an occupational health risk specific to tobacco farming that occurs when workers absorb nicotine through their skin while having prolonged contact with tobacco plants. Public health research has found dizziness, headaches, nausea, and vomiting are the most common symptoms of acute nicotine poisoning. Though the long-term effects of nicotine absorption through the skin are unknown, public health research on smoking indicates that nicotine exposure during adolescence may have long-term adverse consequences for brain development. Public health research indicates that non-smoking adult tobacco workers have similar levels of nicotine in their bodies as smokers in the general population.

In addition, many children told Human Rights Watch that they saw tractors spraying pesticides in the fields in which they were working or in adjacent fields. They often described being able to smell or feel the chemical spray as it drifted over them, and reported burning eyes, burning noses, itchy skin, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, shortness of breath, redness and swelling of their mouths, and headache after coming into contact with pesticides. Yanamaria W., 14, who worked on tobacco farms in central Kentucky in 2013 with her parents and 13-year-old brother, told Human Rights Watch, “I was in the field when they started spraying…. I can stand the heat for a long time, but when they spray, then I start to feel woozy and tired. Sometimes it looks like everything is spinning.”

While pesticide exposure is harmful for farmworkers of all ages, children are uniquely vulnerable to the adverse effects of toxic exposures as their bodies are still developing, and they consume more water and food, and breathe more air, pound for pound, than adults. Tobacco production involves application of a range of chemicals at different stages in the growth process, and several pesticides commonly used during tobacco farming are known neurotoxins. According to public health experts and research, long-term and chronic health effects of pesticide exposure include respiratory problems, cancer, neurologic deficits, and reproductive health problems.

Children also said that they used sharp tools, operated heavy machinery, and climbed to significant heights in barns while working on tobacco farms. Several children reported sustaining injuries, including cuts and puncture wounds, from working with tools. For example, Andrew N., 16, described an accident he had while harvesting tobacco in Tennessee two years earlier: “My first day, I cut myself [on the leg] with the hatchet. … I probably hit a vein or something because it wouldn’t stop bleeding and I had to go to the hospital. They stitched it. … My foot was all covered in blood.”

Many children described straining their backs and taxing their muscles while lifting heavy loads and performing repetitive motions, including working bent over at the waist, twisting their wrists to top tobacco plants, crawling on hands and knees, or reaching above their heads for extended periods of time. Bridget F., 15, injured her back in 2013 while lifting sticks of harvested tobacco up to other workers in a barn in northeastern Kentucky: “I’m short, so I had to reach up, and I was reaching up and the tobacco plant bent over, and I went to catch it, and I twisted my back the wrong way.” According to public health research, the impacts of repetitive strain injuries may be long-lasting and result in chronic pain and arthritis.

Federal data on fatal occupational injuries indicate that agriculture is the most dangerous industry open to young workers. In 2012, two-thirds of children under the age of 18 who died from occupational injuries were agricultural workers, and there were more than 1,800 nonfatal injuries to children under 18 working on US farms.

Nearly all children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their employers did not provide health education, safety training, or personal protective equipment to help them minimize their exposure to nicotine from tobacco leaves or pesticides sprayed in the fields and on the plants. Children typically used gloves, which they or their parents bought, and large black plastic garbage bags, which they brought from home, to wear as protection from wet tobacco leaves and rain. The experience of Fabiana H., a 14-year-old tobacco worker in North Carolina, was typical among the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch:

I wore plastic bags because our clothes got wet in the morning. … They put holes in the bags so our hands could go through them. It kept some of my clothes dry, but I still got wet. …Then the sun comes out and you feel suffocated in the bags. You want to take them off.

Several children reported working in bare feet or socks when the mud in the fields was deep and they lacked appropriate footwear.

Some children reported that, despite long days working outside in the heat, employers did not provide them with drinking water, and most said that they had limited or no access to toilets, hand-washing facilities, and shade. Working long hours in high temperatures can place children at risk of heat stroke and dehydration, particularly if they do not drink enough water, do not have access to shade, and are wearing extra clothes to protect themselves from sunburn and exposure to nicotine and pesticides.

Excessively Long Hours, Wage Problems

Most children interviewed by Human Rights Watch described working long hours, typically between 10 and 12 hours per day, and sometimes up to 16 hours. Most employers allowed children two or three breaks per day, while some children told Human Rights Watch that employers did not allow workers to take regular breaks, even when children felt sick or were working in high heat. Martin S., 18, told Human Rights Watch that his employer on a Kentucky farm where he worked in 2012 did not give them regular breaks during the work day: “We start at 6 a.m. and we leave at 6 p.m. …We only get one five-minute break each day. And a half hour for lunch. Sometimes less.” Many children told Human Rights Watch that some employers pressured them to work as quickly as possible. Some said that they chose to work long hours or up to six or seven days a week in order to maximize their earnings. In other cases employers demanded excessive working hours, particularly during the peak growing and harvest periods of the season.

Children described utter exhaustion after working long hours on tobacco farms. Elan T., 15, and Madeline T., 16, worked together on a tobacco farm after migrating to North Carolina from Mexico with their mother and younger brother. They explained the fatigue they felt after working for 12 or 13 hours in tobacco fields: “Just exhaustion. You feel like you have no strength, like you can’t eat. I felt that way when we worked so much. Sometimes our arms and legs would ache.” Patrick W., 9, described similar feelings after working long hours with his father, a hired tobacco worker, in Tennessee in 2013. “I feel really exhausted,” he said. “I come in [to the house], I get my [clean] clothes, I take a shower, and then it’s usually dark, so I go to sleep.”

Most children reported earning the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour for their work on tobacco farms, though some children were paid a fixed rate during certain parts of the season based on the quantity of tobacco they harvested or hung in barns. Some children reported problems with wages including earning less than minimum wage for hourly work, deductions by the contractor or grower for drinking water or for reasons that were not explained to them, or because of what they believed was inaccurate recording of hours by labor contractors.

Impacts on Education

Most children interviewed by Human Rights Watch attended school full time and worked in tobacco farming only during the summer months, after school, and on weekends. However, a few children who had migrated to the United States for work and had not settled in a specific community told Human Rights Watch that they did not enroll in school at all or enrolled in school but missed several months in order to perform agricultural work, including in tobacco farming. Some children stated that they occasionally missed school to work in times of financial hardship for their families.

International Standards on Child Labor

In recognition of the potential benefits of some forms of work, international law does not prohibit children from working. The International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention, which the US has ratified, obligates countries to prohibit certain types of work for children under age 18 as a matter of urgency, including work that is likely to jeopardize children’s physical or mental health, safety or morals (also known as hazardous labor). The ILO leaves it up to governments to determine which occupations are hazardous to children’s health. Several countries, including major tobacco producing countries such as Brazil and India, prohibit children under 18 from performing work in tobacco farming. Based on our field research, interviews with health professionals, and analysis of the public health literature, Human Rights Watch has concluded that no child under age 18 should be permitted to perform any tasks in which they will come into direct contact with tobacco plants of any size or dried tobacco leaves, due to the health risks posed by nicotine, the pesticides applied to the crop, and the particular health risks to children whose bodies and brains are still developing.

The ILO Worst Forms of Child Labor Recommendation states that certain types of work in an unhealthy environment may be appropriate for children ages 16 and older “on the condition that the health, safety and morals of the children concerned are fully protected, and that the children have received adequate specific instruction or vocational training in the relevant branch of activity.” Because exposure to tobacco in any form is unsafe, Human Rights Watch has determined, based on our field investigations and other research, that as a practical matter there is no way for children under 18 to work safely on US tobacco farms when they have direct contact with tobacco plants of any size or dried tobacco leaves, even if wearing protective equipment. Though protective equipment may help mitigate exposure to nicotine and pesticide residues, rain suits and watertight gloves would not completely eliminate absorption of toxins through the skin and would greatly increase children’s risk of suffering heat-related illnesses. Such problems documented by Human Rights Watch in the US seem likely to extend to tobacco farms outside the United States.

Child Labor and US Law

US laws and policies fail to account for the unique hazards to children’s health and safety posed by coming into direct contact with tobacco plants of any size and dried tobacco leaves. The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) prohibits children under the age of 16 from engaging in agricultural work that the US Secretary of Labor has identified as hazardous. However, the US Department of Labor’s (DOL) regulations on hazardous occupations do not include any restrictions for any children over age 12 to perform work that exposes them to contact with tobacco plants and tobacco leaves.

In addition, US law regulating all child work in agriculture fails to adequately protect children in a sector determined by the ILO to be one of the most dangerous sectors open to children for work. US law permits children to work in agriculture at younger ages, for longer hours, and in more hazardous conditions than children working in all other sectors.

Under US law, there is no minimum age for a child to begin working on a small farm with parental permission. At age 12, a child can work for any number of hours outside of school on a farm of any size with parental permission, and at age 14, a child can work on any farm without parental permission. In other sectors, in contrast, employment of children under age 14 is prohibited, and children ages 14 and 15 may work only in certain jobs and for limited hours outside of school. For example, a child working in a fast food restaurant may only work 18 hours a week when school is in session, while children working in agriculture may work 50 or more hours per week with no restrictions on how early or late they work, as long as it is not during school hours.

At age 16, children working in agriculture can work in jobs deemed to be particularly hazardous, including operating certain heavy machinery or working at heights. However, all other working children must be 18 to perform hazardous work. For example, in agriculture, children under 16 can work at heights of up to 20 feet (over one story) without any fall protection, and 16 and 17-year-olds can work at any height without protection. By contrast, in construction, employers must ensure fall protections for any work taking place over six feet (two meters).

Tobacco Product Manufacturers and Tobacco Leaf Companies

Although the US government has the primary responsibility to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights under international law, private entities, including businesses, also have internationally recognized responsibilities regarding human rights, including workers’ rights and children’s rights. All businesses should have policies and procedures in place to ensure human rights are respected and not abused, to undertake adequate due diligence to identify and effectively mitigate human rights problems, and to adequately respond in cases where problems arise.

In preparation of this report, Human Rights Watch sought to engage 10 companies that source tobacco from the states we visited. Eight of those companies manufacture tobacco products (Altria Group, British American Tobacco, China National Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco Group, Japan Tobacco Group, Lorillard, Philip Morris International, and Reynolds American), and two are leaf merchant companies (Alliance One International and Universal Corporation). Human Rights Watch sought to understand these companies’ policies concerning child labor and other labor rights in their supply chains, as well as mechanisms for implementing and monitoring these policies. Over the course of several months before the release of this report, Human Rights Watch sent letters to each of these companies detailing the preliminary findings of our research and recommendations and requesting meetings with company officials.

Nine companies responded to Human Rights Watch and stated that they took steps to prohibit child labor in their supply chains. Only China National Tobacco did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s letter or repeated attempts to secure a meeting with company executives.

All of the tobacco manufacturing companies and leaf supply merchants that replied to Human Rights Watch expressed concerns about child labor in their supply chain. Only a few of the companies have explicit child labor policies in place. The approaches to child labor in the supply chain varied from company to company, as detailed below. Human Rights Watch correspondence with these companies is included in an appendix to this report, available on the Human Rights Watch website.

Of the companies approached by Human Rights Watch, Philip Morris International (PMI) has developed the most detailed and protective set of policies and procedures, including training and policy guidance on child labor and other labor issues which it is implementing in its global supply chain. PMI has also developed specific lists of hazardous tasks that children under 18 are prohibited from doing on tobacco farms, which include most tasks in which children come into prolonged contact with mature tobacco leaves, among other hazardous work.

Several companies stated that in their US operations they required tobacco growers with whom they contract to comply with US law, including laws on child labor, which, as noted above, do not afford sufficient protections for children. These companies stated that their policies for tobacco purchasing in countries outside of the US were consistent with international law, including with regard to a minimum age of 15 for entry into work under the ILO Minimum Age Convention, with the exception of certain light work, and a prohibition on hazardous work for children under 18, unless national laws afford greater protections. However, most companies did not specify the tasks that they consider to constitute hazardous work. Under these standards, children working in tobacco farming can remain vulnerable to serious health hazards and risks associated with contact with tobacco plants and tobacco leaves. A number of companies stated that they had undertaken internal and third party monitoring of their supply chains to examine labor conditions, including the use of child labor, as defined within the scope of their existing policies.

Recognition of Children’s Vulnerability and the Need for Decisive Action

For the last decade, several members of the US Congress have repeatedly introduced draft legislation that would apply the same protections to children working in agriculture that already protect children working in all other industries. However, Congress has yet to enact legislation amending the Fair Labor Standards Act to better protect child farmworkers, and federal agencies have not made necessary regulatory changes to address the specific risks tobacco farming poses to children. In 2012, DOL withdrew proposed regulations that would have updated the decades-old list of hazardous occupations prohibited for children under age 16 working in agriculture. These regulations, had they been implemented, would have prohibited children under age 16 from working in tobacco. At this writing, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is accepting comments on long-awaited changes to the Worker Protection Standard, a set of safety regulations related to occupational pesticide exposure. It remains to be seen whether the revised regulations will include better protections for child workers.

US laws and policies governing child labor in tobacco are inconsistent with or in violation of international conventions on the rights of children. The US government should acknowledge the particular health and safety risks posed to children exposed to tobacco plants and tobacco leaves, and take immediate action to end all hazardous child labor among children under age 18 on tobacco farms. It should also ensure that laws regulating child labor guarantee that the protections afforded to children working in other sectors, including those concerning working hours, work with sharp objects, machinery, heavy loads, and the like, apply to children working in agriculture as well.

Companies should create child labor policies or amend existing policies to state explicitly that all work in which children come into contact with all tobacco plants and tobacco leaves is hazardous and prohibited for children under 18. Each company should establish effective internal and third-party monitoring of this policy and other relevant labor policies. Given that the international tobacco leaf purchasing markets, including that of the US, often involve third-party suppliers or multiple company contracts with individual growers, members of the industry should seek to formulate industry-wide policies prohibiting hazardous child labor on tobacco farms as well as effective monitoring mechanisms. Companies should also support efforts to provide viable alternatives to working in tobacco farming, including programs to provide children in tobacco communities with education and vocational training.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews with 141 children ages 7 to 17 who said they had worked in tobacco farming in the United States in 2012 or 2013. During multiple field research trips between May and October 2013, Human Rights Watch interviewed 80 children in North Carolina, 46 in Kentucky, 12 in Tennessee, and 3 in Virginia. Eight children worked for less than a full week on tobacco farms. A few of the very youngest children—4 out of 141—worked with their parents sporadically and without pay. The median age of the children we interviewed was 15; the median age at which they began working in tobacco was 13. All personal accounts reported here, unless otherwise noted, reflect experiences children had while they were working on tobacco farms in 2012 or 2013.

Children interviewed were identified with the assistance of individuals and organizations providing legal, health, educational, and social services to farmworkers, farm labor contractors, and through outreach by Human Rights Watch researchers in farmworker communities.

In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed three young people ages 18 to 21 who had worked in tobacco as children, and seven parents of child tobacco workers. Human Rights Watch researchers also conducted interviews with 36 experts, including representatives of farmworker organizations, lawyers, social services providers, healthcare providers, and academic researchers in tobacco-growing regions in the US. In total, 187 people were interviewed for this report.

To supplement formal interviews, researchers spoke with more than 50 outreach workers, educators, doctors, lawyers, tobacco growers, farm labor contractors, and representatives of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) across the US in person and on the telephone. We also spoke with more than 60 adult tobacco workers in the course of our research.

Two Human Rights Watch researchers, one of whom is fluent in Spanish, conducted the interviews. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish, at the interviewee’s preference. Most interviews were conducted individually, though some children were interviewed in small groups of two to five participants. No interviews were conducted in the presence of workers’ employers, such as farm labor contractors or tobacco growers.

Interviews took place in a variety of settings including homes, worksites, schools, restaurants and other public spaces, outdoors as part of outreach in farmworker communities, and at religious institutions. Whenever possible, researchers held interviews in private. In a few cases, interviewees preferred to have a family member or another person present. Interviews were semi-structured and addressed conditions for children working in US tobacco farming, including health, safety, wages, hours, training, and education.

All children and parents interviewed were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be collected and used. For interviews taking place during mealtimes, Human Rights Watch provided food to interviewees. Human Rights Watch did not provide anyone with compensation in exchange for an interview. Individuals were informed that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions without any negative consequences. Participants provided oral informed consent to participate and were assured anonymity. All names of children and parents interviewed have been changed to protect their privacy, confidentiality, and safety. Some individuals approached declined to be interviewed.

Human Rights Watch also analyzed relevant laws and policies and conducted a review of secondary sources. Detailed state-by-state analysis of applicable labor laws, the enforcement of such laws, litigation, and recent and pending legislative projects in North Carolina, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee was undertaken with pro bono assistance from a law firm based in New York City.

Human Rights Watch researchers obtained relevant US federal statistics and other information through public record requests to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) within the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Department of Labor (DOL), the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Between December 2013 and March 2014, Human Rights Watch sent letters to eight companies that manufacture tobacco products (Altria Group, British American Tobacco, China National Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco Group, Japan Tobacco Group, Lorillard, Philip Morris International, and Reynolds American) and two leaf merchant companies (Alliance One and Universal Corporation) detailing the preliminary findings of our research and requesting meetings with company officials. Nine companies responded in writing. The results of this correspondence are detailed in the relevant sections of this report, and copies of the correspondence can be found in the appendix, available on the Human Rights Watch website. In addition, company officials from several companies met or spoke by phone with Human Rights Watch in 2014.

In this report, “child” and “children” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law.

The term “child labor”, consistent with International Labor Organization standards, is used to refer to work performed by children below the minimum age of employment or children under age 18 engaged in hazardous work.

The term “migrant worker” can have various meanings and many farmworkers in the US were, at least at some point in their lives, international migrants. In this report the term “migrant” is used for workers who travel within the US for agricultural work, as distinguished from “seasonal” workers, defined in this report as settled workers based in one place.

I. Tobacco Farming in the United States

Tobacco Production

Tobacco has been cultivated in the United States for centuries, and commercial tobacco production has been a central part of the North American agricultural economy since the 1600s.[1] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, in 2012, the US was the fourth largest producer of unmanufactured tobacco, behind China, Brazil, and India.[2] The total value of tobacco leaf production in the US in 2012 was approximately US$1.5 billion.[3]

Tobacco is grown in at least 10 US states, but North Carolina, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee account for almost 90 percent of domestic tobacco production. Roughly 50 percent of all US-produced tobacco is grown in North Carolina, 25 percent in Kentucky, and 7 percent in each of Virginia and Tennessee.[4] In 2007, the last year for which there is relevant data, there were 8,113 tobacco farms in Kentucky, 2,622 farms in North Carolina, 1,610 farms in Tennessee, and 895 farms in Virginia.[5]

Structure of the Tobacco Economy

Tobacco growers contract with different types of buyers through agreements to produce specific amounts of tobacco at set prices. Contracts often include specific provisions about the type and quality of tobacco produced, and standards for production.[6] Many growers contract directly with manufacturers of cigarettes and other tobacco products.[7] Growers also enter into contracts with leaf tobacco merchant companies, which do not manufacture tobacco products, but buy, process, pack, and ship unmanufactured tobacco to commercial product manufacturers.[8] Some growers also have contracts with cooperative organizations in states that were previously involved in administering now-obsolete federal price support programs, such as the US Tobacco Cooperative. These organizations process and sell tobacco to cigarette manufacturers, and some also produce consumer tobacco products for US markets.[9]

Changes in US Policy and Impacts on Farms and Labor

In 2004, the Fair and Equitable Tobacco Reform Act ended longstanding federal tobacco quota and price support programs designed to control supply and guarantee a minimum price for US tobacco.[10] The law also established the Tobacco Transition Payment Program (TTPP), known as the “tobacco buy-out,” to help tobacco quota holders and producers transition to the free market by providing annual payments for 10 years (2005-2014).[11] The TTPP contributed to contractions in US tobacco farming and production previously underway. By the late 1990s, demand for US tobacco had declined sharply in domestic and foreign markets due to strong competition from international tobacco producers and declines in US consumption of tobacco products.[12] From 1997 to 2007, the number of US farms producing tobacco decreased by 83 percent,[13] with volume down by 57 percent from 1997 to 2012.[14]

Following the tobacco buyout, many small farmers left tobacco and transitioned to alternative crops, while larger farms expanded and consolidated operations.[15] According to a 2010 study by the Center for Tobacco Grower Research, a Tennessee-based organization researching tobacco production, economics, and markets, following the tobacco buyout, average acreage per tobacco farm in the US tripled.[16] The study found that as farm size increased, so did the reliance on hired farm labor relative to unpaid family labor.[17]

Tobacco Types, Farming, and Curing

There are several varieties of tobacco grown in the United States, distinguished and defined by both the characteristics of the leaves and the manner in which they are harvested and cured.[18] The most common types of tobacco produced in the US are flue-cured and burley tobacco. Tobacco is a labor-intensive crop, and even with the use of labor-saving technologies for some production, flue-cured tobacco requires approximately 100 hours of labor per acre, and burley tobacco requires 150 to 200 hours of labor per acre.[19]

The tobacco season generally begins in February or March with cultivation of tobacco seedlings in greenhouses or plant beds. Farmers and workers plant seeds in trays and tend to them for nearly two months—watering, fertilizing, and “clipping” the plants several times, often with mowers suspended over the plants, to keep them uniform in size. In April or May, the seedlings are transplanted into fields. During planting, workers sit facing backwards on a tractor-pulled “transplanter” or “setter.” As the tractor moves through the field, workers load seedlings into slots in a rotating wheel, and the wheel inserts each seedling into a small hole in the ground. Other workers walk behind the setter to straighten and adjust the plants by hand to ensure proper planting.

As the tobacco plants grow, workers dig up weeds with sharp hoes and uproot and reposition plants where two tobacco stalks have taken root. By June or July, workers begin “topping” (breaking off large flowers that sprout at the tops of tobacco plants) and removing “suckers” (nuisance leaves that reduce the yield and quality of tobacco). This process is done entirely by hand and helps to produce larger and more robust tobacco plants. Farmers and workers apply pesticides and growth regulators to tobacco plants at various points in the season (see below for detailed information on pesticides used in tobacco farming). After workers have finished topping, tobacco plants are left to mature in fields until they are ready to be harvested and dried in a process called “curing.”

Flue-Cured Tobacco

Flue-cured tobacco is a broad leaf type of tobacco grown in North Carolina and other parts of the southeastern US. In 2012, nearly 80 percent of US flue-cured tobacco was grown in North Carolina.[20] Flue-cured tobacco is harvested by removing the leaves in a process called “priming,” which involves a series of separate harvests beginning with the lowest leaves and moving up the stalk. The harvest is done primarily by machine, though some workers harvest leaves by hand by pulling tobacco leaves off of the stalks and gathering them under their arms before loading them into trucks to be transported to barns for curing.

Workers then place harvested leaves into racks or cages and load them into heated curing barns. Leaves are left in curing barns for one to two weeks, with heat and ventilation carefully controlled, until leaves are dried and ready to be sorted and packed into bales. Workers help to sort leaves and place them in cages where they are compressed into bales with heavy machines called “balers.” The flue-cured tobacco crop is typically harvested and cured from mid-July to early October.

Burley Tobacco

Burley tobacco is a variety of tobacco grown in Kentucky, Tennessee, and other states in the Appalachian US. In 2012, Kentucky produced 74 percent of the US burley tobacco crop.[21] Burley tobacco is harvested by the stalk, and the harvest is done primarily by hand in a difficult, labor-intensive process. Workers cut each tobacco plant at the base of the stalk with a small axe or hatchet (often called a “tobacco knife”) and then slide them onto wooden sticks equipped with sharp spikes at the end. Workers place six tobacco plants on each stick and leave the sticks in the field to dry for one or two days. Workers then load the sticks of harvested tobacco plants onto flatbed wagons to be transported to barns for curing.

Burley tobacco is dried in open-air barns, without any added heat, in a process called air-curing. To arrange the tobacco for curing, workers climb into the rafters of barns, forming several tiers or levels, and pass sticks of harvested burley tobacco upward to hang it in the barns to dry. Harvested burley tobacco plants dry in curing barns (or sometimes in makeshift field curing structures) for four to eight weeks, when workers take the sticks of tobacco down from the barns and “strip” the leaves off of the stalks by hand. Workers sort and grade tobacco manually, based on the physical qualities of the leaves (e.g. stalk position, color). The tobacco is then packaged into bales for market. The burley tobacco crop is harvested and cured later typically from mid-August to early December.

II. Child Tobacco Workers in the United States

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) estimates that hundreds of thousands of children under age 18 work in US agriculture each year, but there is no comprehensive estimate of the number of child farmworkers in the US. In 2012, farm operators reported directly hiring 130,232 children under age 18 to work on crop and livestock farms, and an additional 388,084 children worked on the farms on which they resided.[22] However, these figures significantly underrepresent the total number of children working in agriculture as they exclude children hired by farm labor contractors or employed informally.[23] The total number of children who work on tobacco farms each year is also unknown.[24]

Child Tobacco Workers

The children interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report were overwhelmingly of Hispanic ethnicity. Many children we interviewed were US citizens, consistent with the findings of a 2013 pilot study of North Carolina child farmworkers in which 78 percent were US citizens.[25] Other children we interviewed were born outside of the United States and had migrated from other countries with their families, or in some instances, by themselves. Regardless of the immigration status of children, the parents of most children interviewed for this report were living in the US without authorization. Child tobacco workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch described working in a diversity of circumstances. The vast majority worked for hire, employed by official or unofficial farm labor contractors, labor subcontractors, or tobacco growers. A small number of children that we interviewed worked on farms owned by family members. Most of the children who stated that they worked on family farms also worked for hire on farms owned by other tobacco growers.

Most children interviewed by Human Rights Watch resided in states where tobacco was grown and worked on farms near their homes. These children overwhelmingly attend public school full time in their communities, often working primarily, or exclusively, during the summer months. The median age at which children we interviewed began working in tobacco was 13. Some of these children worked together with their parents and siblings; others worked without their parents, sometimes with crews composed almost entirely of children. Many seasonal child farmworkers in North Carolina told Human Rights Watch that they worked in tobacco as well as other crops including, variously, sweet potatoes, blueberries, cucumbers, and watermelons.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 16 child migrant workers who move within the United States to work in different agricultural crops, including tobacco. Some of these children said that they travel with their families and attend schools in different states, working only during the summers, after school, and on weekends. Other migrant children stated that they work year round and do not attend school, as described below.

Several children interviewed who had migrated without authorization to the US with their families reported that they had applied for or received deferred action through a federal program designed to provide temporary reprieve from deportation and employment authorization to individuals under age 30 who migrated to the US as children, attended school, have continuously resided in the US for a minimum of five years, and met several other eligibility criteria.[26] Human Rights Watch has argued that “deferred action for childhood arrivals,” by considering a person’s positive attachments to the country of residence in deportation decisions, represents a rational, if incremental, shift in US immigration policy.[27] Human Rights Watch has called on the US government to enact more permanent and comprehensive immigration reforms.[28]

Why Children Work

Nearly all of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch, whether seasonal or migrant, citizens or unauthorized, reported that they worked in tobacco to provide for themselves and their families. The National Agricultural Workers Survey, a random survey of crop workers in the US, indicates that farmworkers are overwhelmingly poor: in 2008-2009, the median annual income among US crop workers was $18,750.[29] A 2008 report from the US Department of Agriculture found poverty among farmworkers is more than double that of all wage and salary employees in the United States.[30] Most children interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report started working in tobacco farming, and in some cases in other crops as well, to earn money for their basic needs: clothes, shoes, school supplies. Parents of child workers said that their children’s minimum wage earnings helped to supplement meager family incomes.

Economic Need

Gabriella G., 42, is a mother of six, and five of her children have worked in tobacco fields in North Carolina. She moved to North Carolina after leaving an abusive partner and is now a single mother. When asked why her children started working in tobacco, she said, “What I earn is not sufficient for my family. My children have to work to buy school supplies, clothes, the things you have to pay for at school.”[31] Her daughter Natalie G., 18, started working in tobacco at age 12. She told Human Rights Watch why she started working: “I saw what my mom was going through, how tired she was, and we wanted to help. … There was motivation to work because my mom was working and we were alone without her. And seeing my mom come beaten down, sunburned, tired. We were raised not to leave someone behind.”[32] Natalie’s younger sister, Elena G., also started working in tobacco at age 12. She told Human Rights Watch how she used her earnings: “I would give my mom more than half of my check for the bills. And then I would help her buy food. And whatever I had left, I’d buy my little brother something. I wanted to buy clothes, but I didn’t really have the chance to.”[33]

Other children described similar reasons for working in tobacco. Raul D., a 13-year-old worker in eastern North Carolina, told Human Rights Watch, “I work so that I have money to buy clothes for school and school supplies, you know, like crayons and stuff. I’ve already bought my backpack for next year.”[34] Adriana F., 14, works for hire on tobacco farms in Kentucky with her parents and her four brothers. When asked how she used her earnings, she told Human Rights Watch, “I use the money for school supplies and to go on field trips.” Jerardo S., 11, told Human Rights Watch he started working on tobacco farms in Kentucky to save for his college education, saying, “I told my mom I would save it for the college or university where I want to go.”[35]

Lack of Other Opportunities

In addition to economic need, children, particularly those living in the US without authorization, reported working in tobacco because they lacked other employment and summer educational opportunities in their rural communities. Blanca A., like many farmworker children, was born in Mexico and works without authorization, even though she has lived in the United States for many years. “Most of my friends have jobs in the new sports shop, at McDonald’s or Bojangles, in the mall selling stuff,” she told Human Rights Watch. “But usually for those jobs they ask for [your] social security [number].”[36] Claudio G., a 16-year-old unauthorized worker in North Carolina, told Human Rights Watch, “Tobacco is the only job we [unauthorized children] have during the summer.”[37]

Other children said that they were too young to be hired to work other jobs. Alan F., a 15-year-old worker in eastern North Carolina who hopes to attend college after graduating from high school, told Human Rights Watch that he would continue working in tobacco until he was older. “There’s plenty of jobs, but I mean, I ain’t got the age,” he said. “If I was older, I’d want to be a mechanic or work in construction or something like that.”[38]

Of the nine children interviewed by Human Rights Watch who worked on tobacco farms owned by family members, most had other career aspirations. For example, 15-year-old Bradley S., who started working on tobacco farms owned by his father and grandfather in eastern Kentucky at 8, told Human Rights Watch, “When I grow up, I want to be an engineer.”[39]

III. Health and Safety

Nearly three-quarters of children interviewed by Human Rights Watch in North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, 97 out of 133, reported feeling sick—with nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, headaches, dizziness, skin rashes, difficulty breathing, and irritation to their eyes and mouths—while working in fields with tobacco plants and in barns with dried tobacco leaves and tobacco dust.[40] Many reported being exposed to pesticides and to extreme temperatures and unrelenting heat while working in tobacco fields. Some stated that they used sharp tools and cut themselves, or operated heavy machinery and climbed to significant heights, risking serious injury. Many children described straining their backs and taxing their muscles while lifting heavy loads and performing repetitive motions, including working bent over at the waist, twisting their wrists to top tobacco plants, crawling on hands and knees, or reaching above their heads for extended periods of time.

Nearly all children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their employers did not provide health education, safety training, or personal protective equipment to help them minimize their exposure to nicotine from tobacco leaves or pesticides sprayed in the fields and on the plants. Some children reported that, despite long days working outside in the heat, employers did not provide them with drinking water, and most said that they had limited or no access to toilets, hand-washing facilities, and shade.

Based on our field research, interviews with health professionals, and analysis of public health literature, Human Rights Watch has concluded that no child under age 18 should be permitted to perform any tasks in which they will come into direct contact with tobacco plants of any size or dried tobacco leaves, due to the health risks posed by nicotine, the pesticides applied to the crop, and the particular health risks to children whose bodies and brains are still developing. Though protective equipment may help mitigate exposure to nicotine and pesticide residues, rain suits and watertight gloves would not completely eliminate absorption of toxins through the skin and would greatly increase children’s risk of suffering heat-related illnesses. As a result, Human Rights Watch has determined that there is no practical way for children to work safely in the US when handling or coming into contact with tobacco in any form.

Sickness while Working

More than two out of three children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had felt suddenly, acutely ill while working in fields of tobacco plants and performing such jobs as topping, pulling off suckers, weeding, straightening plants, harvesting tobacco, and while working in curing barns. Children interviewed by Human Rights Watch described working, especially in wet conditions—during or after rainfall or in the morning with a heavy dew on the tobacco leaves—and becoming severely nauseous, dizzy or lightheaded. Some children said that they also vomited while working. Other children said they suffered severe headaches, and after a day’s work with tobacco, felt a sustained loss of appetite and energy, or had difficulty sleeping.

Nausea, Vomiting, and Loss of Appetite

Children in all four states described nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite while working on tobacco farms. For example, Elena G., a 13-year-old seasonal worker living in eastern North Carolina, spent both the 2012 and 2013 summers working in tobacco with her mother. She told Human Rights Watch how she felt while topping tobacco:

I felt very tired. … I would barely eat anything because I wouldn’t get hungry…We would get our lunch break and I would barely eat, I would just drink. …Sometimes I felt like I needed to throw up. I never did. It had come up my throat, but it went back down. …I felt like I was going to faint. I would stop and just hold myself up with the tobacco plant.[41]

Elena’s mother, Gabriella G. described her daughter’s condition: “Sometimes I saw that she couldn’t bear it. She was going to faint. She had headaches, nausea. Watching her was so hard. She’s skinny now, but imagine: she was even skinnier then [when she was working]. She was losing weight.”[42]

Yolanda F., a 16-year-old seasonal worker in eastern North Carolina, started working on tobacco farms in 2013 with two of her friends during their summer break from school. She described how she felt during her first days on the job: “My first day I felt dizzy. I felt like I was going to throw up, but I didn’t. I just started seeing different colors….I didn’t last through lunch that day.”[43]

Child tobacco workers in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia often experienced nausea and vomiting while cutting stalks of burley tobacco during the harvest. For example, Danielle S., 16, told Human Rights Watch that she has been working for hire with her parents and brother on tobacco farms outside of Lexington, Kentucky for several years during the summers, after school, and on weekends. Danielle said that she got sick while harvesting tobacco in 2013: “It happens when you’re out in the sun. You want to throw up. And you drink water because you’re so thirsty, but the water makes you feel worse. You throw up right there when you’re cutting, but you just keep cutting.”[44] Her brother, age 15, described feeling sick while working in tobacco at a younger age: “A couple of years ago, I was throwing up in the field. I took medicine, and then I went back to work.”[45]

Ten-year-old Marta W. and her brother Patrick W., 9, worked together with their father in 2013 on tobacco farms in Tennessee, about 60 miles northeast of Nashville. Several different tobacco growers hire their father to harvest tobacco plants and hang them on sticks to dry in barns. Because he is paid a fixed rate for each stick of tobacco plants he harvests and hangs in a barn, Marta and Patrick work with him to increase his earnings. Patrick told Human Rights Watch about his experience harvesting burley tobacco in 2013: “I’ve gotten sick. We started cutting [tobacco plants], and I had to go home. I kept on coughing [heaving], and I had to eat crackers and drink some Gatorade…. I threw up a little bit. It took two or three hours before I felt better.” Marta, also describing working in 2013, added, “I felt sick when I went, but I didn’t actually throw up because I stayed out of the barn. I felt kind of nauseous. My head felt bad.”[46] Jaime V., 18, said that he felt nauseated while working in the curing barns. He told Human Rights Watch, “I worked all the way at the top of the barn, too. It’s just hot up there. The air is humid and the smell [of tobacco] fills your nose and mouth, and you get sick.”[47]

Headaches, Dizziness, and Lightheadedness

Children told Human Rights Watch that they suffered from headaches, dizziness, and lightheadedness while working on tobacco farms. Emilio R., a 16-year-old seasonal worker who hopes to study to be an engineer, said that in addition to topping and pulling suckers off tobacco plants, he harvested flue-cured tobacco leaves by hand on farms in eastern North Carolina in 2012. He described that process: “We grab the [tobacco] leaves, put them under our arm until we have a bundle, then throw them in the truck.”[48] Emilio also said he had headaches that sometimes lasted up to two days during the 2012 season: “With the headaches, it was hard to do anything at all. I didn’t want to move my head.”[49] His 17-year-old sister, Jocelyn, also harvested tobacco leaves by hand, and she also said she had headaches while working: “I would get headaches sometimes all day. I think it was from the smell of the tobacco. I really didn’t like it.”[50]

Miguel T., 12, a seasonal worker in eastern North Carolina, said that in July 2013 during his first month working in tobacco fields, he got a headache while topping tobacco: “I got a headache before. It was horrible. It felt like there was something in my head trying to eat it.”[51]

Cameron M., 18, and his brother Leonardo M., 15, migrated to central Kentucky from Guatemala with their father in the winter of 2013. They worked together for several months on tobacco farms, stripping dried tobacco leaves off of sticks after they had cured in barns. Both boys reported headaches and dizziness while stripping dried tobacco leaves off of sticks. Leonardo M. told Human Rights Watch, “I felt like I was spinning in circles, and my head ached. I felt awful.”[52] Pablo E., a 17-year-old worker in Kentucky described dizziness as “a symptom of the work.”[53] Jacob S., a 14-year-old tobacco worker in Virginia, described similar symptoms: “I get a little bit queasy, and I get lightheaded and dizzy. Sometimes I feel like I might pass out. It just feels like I want to fall over.”[54]

Sleeplessness

Some children described recurrent sleeplessness. Jaime V., 18, started working in tobacco in Tennessee when he was 14 after migrating to the United States with his cousin. At first, he did not enroll in school, instead working full-time for a contractor doing agricultural work. Describing his first summer working in tobacco four years ago, he told Human Rights Watch, “I got sick. I couldn’t sleep at night. I felt dizzy.”[55] Luciano P., 18, worked on tobacco farms in Kentucky: “When I got sick, when I tried to go to sleep, I couldn’t go to sleep. I was feeling tired, but I couldn’t sleep. Sometimes you throw up. I had headaches.”[56]

Acute Nicotine Poisoning and Exposure to Nicotine among Children

Taken together, the symptoms reported to Human Rights Watch by child tobacco workers in North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia are consistent with acute nicotine poisoning, known as Green Tobacco Sickness, an occupational health risk specific to tobacco farming. Green Tobacco Sickness occurs when workers absorb nicotine through their skin while having prolonged contact with tobacco plants.[57] Researchers have documented dizziness, headaches, nausea, and vomiting as the most common symptoms of acute nicotine poisoning.[58] In some cases, these symptoms may be linked to or exacerbated by pesticide exposure or working in conditions of high heat and high humidity without sufficient rest, shade, and hydration.[59]

Acute nicotine poisoning generally lasts between a few hours and a few days,[60] and although it is rarely life-threatening, severe cases may result in dehydration which requires emergency treatment.[61] Children are particularly vulnerable to nicotine poisoning because of their size, and because they are less likely than adults to have developed a tolerance to nicotine.[62] The long-term effects of nicotine absorption through the skin have not been studied,[63] although the long-term effects of consuming tobacco products containing nicotine has been well documented.

Working in wet, humid conditions increases the risk of poisoning as nicotine dissolves in the moisture on the leaf and is more readily absorbed through the skin. A public health study conducted in North Carolina collected dew samples from tobacco plants on four farms and found nicotine in all samples, ranging from 33 to 84 micrograms per milliliter of dew.[64] The researchers estimated that on humid days, farmworkers could be exposed to 600 milliliters or more of dew, containing between 20 and 50 milligrams of nicotine.[65] However, the percentage of nicotine in dew that is absorbed through the skin is not known. A 2007 review of public health studies found that non-smoking adult tobacco workers have similar levels of nicotine in their bodies as smokers in the general population, althoughindividual variation would be expected based upon the use of personal protective equipment, season and contact with tobacco, and abrasions on the skin, as well as other factors.[66] Working in excessive heat and engaging in heavy physical activity, which are typical for workers, including child workers, engaged in tobacco farming in the United States, also increase the risk of nicotine poisoning as the increase in surface blood flow to help reduce body temperature facilitates nicotine absorption.[67]

Though public health research has most often looked at nicotine poisoning among adult workers handling mature tobacco leaves, nicotine is present in tobacco plants and leaves in any form. According to Dr. Thomas Arcury, director of the Center for Worker Health at Wake Forest School of Medicine, “Nicotine is part of the plant. The tobacco plant, by its nature, contains nicotine from the time it’s a seedling to the end.”[68] As a result, added Arcury, any task that requires the handling of tobacco in any form may expose workers to nicotine.[69]

Nicotine may affect human health in distinct ways depending on how it enters the body—whether absorbed through the skin, inhaled, or ingested.[70] Though the long-term effects of nicotine absorption through the skin are unknown, public health research on smoking indicates that nicotine exposure during childhood may have long-lasting consequences. According to the US Surgeon General’s most recent report, “The evidence is suggestive that nicotine exposure during adolescence, a critical window for brain development, may have lasting adverse consequences for brain development.”[71]

Skin Conditions, Respiratory Illness, and Eye and Mouth Irritation

Children interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported skin conditions, difficulty breathing, sneezing, and eye, nose, mouth, and throat irritation while working on tobacco farms.

Skin Conditions

Some children reported itchy or burning skin or skin rashes while working in tobacco farming, particularly while topping and suckering. Children often noted that their skin irritations were worse when they were working in wet clothing or without gloves, particularly if working in those conditions for extended periods of time.

Diego T. and Rafa B., both 16, who worked together on tobacco farms in eastern North Carolina in the summer of 2013, told Human Rights Watch that they suffered from skin problems while working in tobacco. Diego said, “Your skin gets irritated. It burns, sometimes when you get wet, you get rashes. Like when you cut the flower, and touch your skin, it stings and burns.”[72] Rafa had a similar observation: “When … you wipe your face, it burns. Or if you scratch yourself.”[73] Joshua D., 13, also worked in eastern North Carolina in 2013: “You can’t wipe your face when you’re working because it burns. It feels like fire ants on your forehead.”[74]

Some children also reported skin rashes. “I’ve had red bumps all over my arm,” said Sally G., 16, who worked in North Carolina for the first time in the summer of 2013. “They are very itchy…. I used to roll up my sleeves when it got hot but then I started to get bumps on my arms.”[75] Jocelyn R., a 17-year-old worker who worked in tobacco in North Carolina in 2012, said: “I’d get a rash on my hands [while topping tobacco], it would last until the next day. It was itchy.”[76] Estevan O., 15, worked in tobacco in the 2012 season said, “I’d have itching hands and feet. It’s wet. Your socks and gloves get wet. Your skin starts itching and cracking. The cracking would really hurt.”[77]

Public health research has shown a high prevalence of skin conditions among farmworkers.[78] A 2007 study of tobacco workers found that they may be particularly susceptible to skin conditions as both the tobacco leaf itself and pesticides used in tobacco cultivation have been identified as possible causes of contact dermatitis, an inflammatory skin disease.[79] Human Rights Watch could not determine the exact cause of the skin irritations or rashes reported by child tobacco workers.

Respiratory Symptoms and Allergic Reactions

Some children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they experienced respiratory and allergic symptoms while topping and harvesting tobacco in fields, or hanging tobacco to dry in curing barns.

For example, Erica P., age 16, described topping tobacco in Eastern North Carolina in July 2013: “There is no air in the rows. It’s really hard to breathe.”[80] Alberto H., 16, who plays on his high school’s soccer team in southeastern Kentucky, told Human Rights Watch that he has trouble breathing while hanging tobacco in barns: “When you’re at the top of the barn, you can’t breathe up there.… It’s probably because [there is] a bunch of dust and it’s hard to breathe, and I have asthma. I always bring my inhaler.”[81] Dario A., also a 16-year-old worker in Kentucky, said, “The hardest part of the job is climbing up high in the barn. It’s hard to breathe up there.”[82]

Some child tobacco workers also reported respiratory and allergic symptoms while working with dried tobacco. Sixteen-year-old Timothy Y. works for his parents, grandparents, and neighbors on tobacco farms in Kentucky. He told Human Rights Watch, “I don’t like to do the stripping because it messes with my allergies and makes it hard to breathe.”[83] Joaquin F., 16, started stripping tobacco in barns at age 12 in Kentucky and continued to work for hire after school and on weekends until he got a job at local restaurant at age 16. Describing the work he did in curing barns in 2012, he told Human Rights Watch, “When I was stripping, all the dust from the tobacco would get to my lungs and get stuck in my nose. You just feel sick.”[84]

A 2011 study on the prevalence of respiratory and allergic symptoms among non-smoking farmworkers in eastern North Carolina found nearly one-quarter reported wheezing at times, with elevated odds of wheezing for individuals working in tobacco production.[85] Public health research among adult workers has also shown that workers exposed to tobacco dust during curing and baling showed significantly lower lung function than unexposed workers.[86]

Eye and Mouth Irritation

Some child tobacco workers told Human Rights Watch that liquid from wet tobacco plants would splash into their eyes or mouths while they were working in the fields, causing pain, itching, or other irritation. Children often described working in fields where tobacco plants reached above their heads, and they may have been particularly vulnerable to these effects due to their small size relative to the plants. Sally G., a 16-year-old seasonal tobacco worker described topping tobacco plants taller than her in wet fields in eastern North Carolina during the summer of 2013: “I’ve felt the spray on my face. It splashes from the plants. … It really hurts when it gets in your eyes. They tell us to try to keep our faces covered up. … Water from the flowers gets on your face, and when it’s mixed with the pesticide, it burns.”[87]

Estevan O., 15, told Human Rights Watch that he started working on tobacco farms in North Carolina at age 11 because, “My family needed me to.” He described working in wet tobacco fields during the 2012 season: “The water on the leaves would splash in my eyes [when I was topping]. My eyes would get irritated. I’d have to take my contacts out and wear glasses.”[88] While describing his work harvesting tobacco in Tennessee in 2013, Patrick W., 9, said, “Sometimes if it gets to your eyes, it will sting a little bit, like burn.”[89]

Several children interviewed in Kentucky said pieces of tobacco leaves would fall into their eyes or mouth while lifting sticks with tobacco plants to be hung in barns causing irritation, pain, and a sour taste in their mouths. Andrea D., 16, works for hire for a tobacco grower in central Kentucky together with her mother. She lifts sticks of harvested tobacco to other workers who hang the sticks in the rafters of curing barns. While describing her work in the barns in 2012, she said, “It gets all over you. It gets all in your mouth and in your nose. It’s just sour. The leaves and the dust get in your nose, and it itches. And it gets in your ears. You have a bitter taste in your mouth. It goes away the next day, but then you do it again, and it comes back.”[90] Henry F., a 17-year-old tobacco worker in Kentucky, told Human Rights Watch that lifting sticks of tobacco irritated his eyes while he was working in 2012: “If you’re at the bottom you have to lift it up. And when you lift it up the tobacco goes in your mouth and eyes. And when it goes in your eyes, it makes your eyes reddish and pinkish.”[91]

Exposure to Pesticides

Just over half of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch—63 out of 120—reported that they saw tractors spraying pesticides in the fields in which they were working or in fields adjacent to the ones in which they were working.[92] These children often reported being able to smell or feel the chemical spray as it drifted towards them. A few children stated that they applied pesticides to tobacco plants with a handheld sprayer and backpack, or operated tractors that were spraying pesticides on tobacco fields.[93] Children also reported experiencing a range of symptoms after coming into contact with pesticides while working in tobacco farming, including burning eyes, burning nose, itchy skin, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, shortness of breath, redness and swelling of the mouth, and headaches. Exposure to pesticides can have serious short-term and long-term health effects.

Exposure to Pesticides Sprayed by Tractors

Many children interviewed by Human Rights Watch described being exposed to pesticides, most often through drift, when a pesticide applied in one area spreads to adjoining areas through wind.[94] Many stated that they felt drift from tractors spraying in adjacent fields; in a few cases they said that tractors sprayed pesticides in the fields in which they were working.

For example, Jocelyn R., 17, started working on tobacco farms in eastern North Carolina at 14, along with her younger brother. Describing an incident that occurred during the summer of 2012, she told Human Rights Watch:

Once they sprayed where we were working. We were cutting the flower and the spray was right next to us in the part of the fields we had just finished working in. I couldn’t breathe. I started sneezing a lot. The chemicals would come over to us. The farmer when he was spraying would get ahead of us and it would come back over us. No one ever told us about the chemicals.[95]

Cameron M., an 18-year-old worker in Kentucky, described seeing a tractor spraying in the tobacco field in which he was working: “One time I saw a tractor spraying chemicals on the field. It made the workers upset. There was a strong smell. We all covered our mouths and noses.”[96]

Children also reported being taken to work in fields that had been sprayed very recently with pesticides. “I went back into a field after they sprayed it, like right after they sprayed it,” said 16-year-old Andrew N., a 10th grade student in Tennessee who works with a crew of tobacco workers led by his stepfather. He described the incident to Human Rights Watch,

I didn’t know…I did notice it because the spray was all over the plant, the yellow stuff was all over it, and my shirt was getting all the yellow liquid on it. We didn’t want to work anymore. And finally the boss guy came, and he told us he had sprayed down, so we left. The smell was pretty strong. I really wouldn’t know how to explain it, but it was a strong smell.[97]

Similarly, Emilio R., 16, told Human Rights Watch that he reentered a tobacco field in North Carolina minutes after the grower had applied pesticides. “We were working in one field and finished half of the field and then the farmer decided to spray [pesticides using a tractor],” he said. “It [the drift] was about to catch up to us and so we stepped out of the field. We waited a few minutes and went back in.”[98]

Immediate Health Effects of Pesticide Exposure

Children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they experienced a range of symptoms after coming into contact with pesticide spray including burning eyes, burning noses, itchy skin, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, shortness of breath, redness and swelling of their mouths, and headaches. For example, 17-year-old Lucia A., interviewed by Human Rights Watch on the day of her junior prom in a small North Carolina town, said:

One time I got a lot of splotches on my leg. … I was around 15. It was bad. It got red. … It was like a rash. It started itching. I kept telling my mom. She kept telling [the contractor] maybe we shouldn’t work in this field. And he said, “No, it’s ok, it isn’t supposed to harm us.” And then I saw other workers start walking out, saying “I can’t work like this.” … I showed [the contractor the rash on] my legs, and then he said, “Let’s move to a different field.”[99]

Jimena C., 15, spends her summers living with her godmother so that she can work on tobacco farms in a county about 30 miles from her hometown in North Carolina. She told Human Rights Watch that she got very ill at age 14 after working in a field sprayed with pesticides only a few hours earlier: “I got so sick one time after they sprayed. It was just a few hours after they sprayed and we went in. I got really dizzy. And I saw black. I sat down and threw up several times.”[100] Marta W., 10, felt ill after a tractor sprayed pesticides while she and her younger brother were helping their father, a hired farmworker, on a tobacco farm in northern Tennessee in the summer of 2013. “They were like spraying it to make it grow bigger the time we went,” she said. “It was in the same field as us. It was on the other side of the field. The smell was very nasty. I felt nauseous after that.”[101]

Yanamaria W., 14, who started working on tobacco farms in 2012, spent two summers working for a farm labor contractor in central Kentucky together with her parents and 13-year-old brother. Yanamaria told Human Rights Watch about being exposed to pesticides sprayed from a tractor in the summer of 2013. “I was in the field when they started spraying,” she said. “I can stand the heat for a long time, but when they spray, then I start to feel woozy and tired. Sometimes it looks like everything is spinning. You can’t focus on your task.”[102]

Nicholas V., an 8th grader, told Human Rights Watch that he works for hire in tobacco fields in North Carolina with his mother during his summer break. He described a pesticide drift from spraying in an adjacent field while he was working in 2012:

We were working in one field and the field next to us got sprayed with a tractor. The liquid is in the air and it fell on us, too. That stuff really bothered us. I got some in my eyes. They got itchy. I got really annoyed and asked to get out. I had to sit out for two hours. My eyes were really itchy. Really bad. … It was really windy that day.[103]

Yael A., a 17-year-old seasonal worker in North Carolina, said, “When they spray, the smell is very strong. And it causes a terrible smell, a really bad smell, and sometimes you feel itchy, tingly, in your mouth and your nose. It itches. Your mouth gets red and puffy.”[104]

Marissa G., 14, first worked on tobacco farms in North Carolina in the 2013 season, together with her older sister. She said that working in tobacco triggered her asthma symptoms, particularly when she was exposed to pesticides: “The spray affects my asthma. When I smell it, it makes me nauseous, short of breath, even if I’m not really doing anything.”[105]

Children Applying Pesticides

Five children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they applied pesticides to tobacco plants with a handheld sprayer and backpack, or operated tractors that were spraying pesticides on tobacco fields. Christian V., age 13, explained that he uses a backpack sprayer to apply pesticides to his family’s tobacco fields in Tennessee: “We spray it with chemicals for worms and so it can help it grow. I use a backpack. There’s like a cap on the top, and you twist it open and put water in it and all the chemicals, then you throw it on your back and you walk and you get this thing and you squirt it on top of the plants.”[106] Theo D., 16, described how he felt one day in the summer of 2013 after using a backpack sprayer to apply an insecticide to tobacco fields on a Virginia farm where he worked: “I got home and felt dizzy and started puking, but I took a cold shower and got over it.[107]

Hazards of Pesticides

Pesticides enter the human body when they are inhaled, ingested, or absorbed through the skin. According to a review of public health studies of farmworkers, pesticide exposure is associated with acute health problems including nausea, dizziness, vomiting, headaches, abdominal pain, and skin and eye problems.[108] Exposure to large doses of pesticides can have severe health effects including spontaneous abortion and birth deformities, loss of consciousness, coma, and death.[109] Long-term and chronic health effects of pesticide exposure include respiratory problems, cancer, depression, neurologic deficits, and reproductive health problems.[110] Children are uniquely vulnerable to the adverse effects of toxic exposures as their brains and bodies are still developing, and they consume more water and food, and breathe more air, pound for pound, than adults.[111]

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that 10,000 to 20,000 physician-diagnosed pesticide poisonings occur each year among US agricultural workers.[112] One public health study found that 64 percent of acute occupational pesticide-related illnesses reported by children occurred among children working in agriculture, and this number represents only a small fraction of actual pesticide poisonings as many cases are never reported.[113]