Summary

Laila R. fled Afghanistan with her parents and her two brothers in 2016, when she was 11 or 12 years old. They sought international protection in Iran, then Turkey, and then Greece. Increasingly desperate for stability, they travelled through North Macedonia and arrived in Bosnia and Herzegovina in early 2021. When Laila first spoke to Human Rights Watch in November 2021, she and her family had tried to enter Croatia dozens of times. Croatian police apprehended her and her family each time, ignored their repeated requests for asylum, drove them to the border, and forced them to return to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

When Croatian police carry out such pushbacks—broadly meaning official operations intended to physically prevent people from reaching, entering, or remaining in a territory and which either lack any screening for protection needs or employ summary screening—they do not contact authorities of Bosnia and Herzegovina to arrange for people’s formal return. Instead, Croatian police simply order people to wade across one of the rivers that mark the international border.

Laila and many others interviewed by Human Rights Watch said Croatian authorities frequently pushed them back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in the middle of the night. She and others told Human Rights Watch Croatian police sometimes pushed them back near Velika Kladuša or other towns in Bosnia and Herzegovina. But on many occasions, the Croatian police took them somewhere far from populated areas.

Describing the first pushback she experienced, Laila said, “We had no idea where we were. It was the middle of the night, and the police ordered us to go straight ahead until we crossed the river to Bosnia. We spent that night in the forest.”

Croatian police had destroyed the family’s phones, so they had no easy way of navigating to safety. The next morning, she and her family eventually came across a road. They walked some 30 kilometers to reach Velika Kladuša.

As with Laila and her family, many of the people who spoke to Human Rights Watch told us they had first sought asylum in Greece as well as in countries outside the European Union before they attempted to enter Croatia. Laila and her family spent one month in Iran, six months in Turkey, and more than three years in Greece, leaving each country after concluding that authorities in each did not intend to respond to their requests for international protection. They did not seek international protection in Bosnia and Herzegovina because they had heard that the country’s authorities rarely granted asylum.

Croatia became an increasingly important point of entry to the European Union in 2016, after Hungary effectively closed its borders to people seeking asylum. Croatian police have responded to the increase in the number of people entering Croatia irregularly—without visas and at points other than official border crossings—by pushing them back without considering international protection needs or other individual circumstances. In April 2023, for instance, Farooz D. and Hadi A., both 15 years old, told Human Rights Watch Croatian police had apprehended them the night before, driven them to the border, and ordered them to walk into Bosnia and Herzegovina, disregarding their request for protection and their statements that they were under the age of 18.

Pushbacks from Croatia to the non-European Union countries it borders are now common. Between January 2020 and December 2022, the Danish Refugee Council recorded nearly 30,000 pushbacks from Croatia to Bosnia and Herzegovina, almost certainly an underestimate. Approximately 13 percent of pushbacks recorded in 2022 were of children, alone or with families. Human rights groups have also recorded pushbacks from Croatia to Serbia and to Montenegro.

Croatian pushbacks have often included violent police responses, including physical harm and deliberate humiliation. Video images captured by Lighthouse Reports, an investigative journalism group, for a 2021 investigation it conducted in collaboration with Der Spiegel, the Guardian, Libération, and other news outlets showed a group of men in balaclavas forcing a group of people into Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although the men did not wear name tags or police badges, the investigation identified them as Croatian police based on characteristic clothing items, the gear they carried, and the corroboration of other police officers. Der Spiegel recounted, “One of the masked men repeatedly lashes out with his baton, letting it fly at the people’s legs so that they stumble into the border river, where the water is chest-high. Finally, he raises his arm threateningly and shouts, ‘Go! Go to Bosnia!’”[1]

In most of the accounts Human Rights Watch heard, Croatian police wore uniforms, drove marked police vans, and identified themselves as police, leaving no doubt that they were operating in an official capacity.

Men and teenage boys have told Human Rights Watch and other groups that Croatian police made them walk back to Bosnia and Herzegovina barefoot and shirtless. In some cases, Croatian police forced them to strip down to their underwear or, in a few cases, to remove their clothing completely. In one particularly egregious case documented by the Danish Refugee Council, a group of men arrived at a refugee camp in Bosnia and Herzegovina with orange crosses spray-painted on their heads by Croatian police, an instance of humiliating and degrading treatment the Croatian ombudswoman concluded was an act of religious hatred.

Younger children have seen their fathers, older brothers, and other relatives punched, struck with batons, kicked, and shoved. Croatian border police have also discharged firearms close to children or pointed firearms at children. In some cases, Croatian police have also shoved or struck children as young as six.

Croatian police commonly take or destroy mobile phones. Human Rights Watch also heard frequent reports that Croatian police had burned, scattered, or otherwise disposed of people’s backpacks and their contents. In some cases, people reported that police had taken money from them. “The last time we went to Croatia, the police took everyone’s money and all our telephones. Why are they like this?” asked Amira H., a 29-year-old Kurdish woman from Iraq travelling with her husband and 9-year-old son.[2]

Pushbacks inflict abuse on everyone. In particular, many people said pushbacks took a toll on their mental well-being. Hakim F., a 35-year-old Algerian man who said Croatian police had pushed him back four times between December 2022 and January 2023, commented, “These pushbacks are so stressful, so very, very stressful.”[3] Stephanie M., a 35-year-old Cameroonian woman, told Human Rights Watch in May 2022, “These pushbacks have been so traumatizing. I find I cannot sleep. I am always thinking of the things that have happened, replaying them in my head. There are days I cry, when I ask myself why I am even living. I find myself thinking, ‘Let everything just end. Let the world just end.’”[4]

For children and their families, who frequently cannot travel as fast on foot as single adults can, pushbacks may add considerably to the time spent in difficult, often squalid, and potentially unsafe conditions before they are able to make a claim for asylum in an EU country. They increase the time children spend without access to formal schooling. For unaccompanied children in particular, pushbacks can increase the risk that they will be subject to trafficking. Family separation may also result from pushbacks: the nongovernmental organization Are You Syrious has reported cases of women allowed to seek asylum in Croatia with their children while their husbands are pushed back to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Croatian police continued to carry out pushbacks throughout 2022, although in the second half of the year police increasingly employed an alternative tactic of issuing summary expulsion orders directing people to leave the European Economic Area within seven days. These summary expulsion orders did not consider protection needs and did not afford due process protections. By late March 2023, Croatian police appeared to have abandoned this practice and resumed their reliance on pushbacks.

Croatian authorities regularly deny the overwhelming evidence that Croatian police have regularly carried out pushbacks, sometimes inflicting serious injuries, frequently destroying or seizing phones, and nearly always subjecting people to humiliating treatment in the process. The Croatian government did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s request for comment on this report.

On the initiative of and with funding from the European Union, Croatia has established a border monitoring mechanism, with the ostensible purpose of preventing and addressing pushbacks and other abuses at the border. The mechanism’s parameters and track record have so far not been promising. Its members cannot make unannounced visits and cannot go to unofficial border crossing points. It is not clear how the members are appointed and how the mechanism’s priorities are defined. It has had its reports revised to remove criticism of Croatian police and the Croatian Ministry of the Interior.

Croatia’s consistent and persistent use of pushbacks violates several international legal norms, including the prohibitions of torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, collective expulsion, and refoulement—the sending of people to places where they would face ill-treatment or other irreparable harm or would be at risk of return to harm. Pushbacks of children violate the international norm that states take children’s best interests into account, including by taking particular care to ensure that returns of children are in their best interests. Excessive force, other ill-treatment, family separation, and other rights violations may also accompany pushback operations.

Slovenia and other European Union member states are also implicated in the human rights violations committed by Croatian authorities against people transferred to Croatia under “readmission agreements”—arrangements under which states return people to the neighbouring countries through which they have transited, with few, if any, procedural safeguards. For instance, under Slovenia’s readmission agreement with Croatia, Slovenian police summarily transferred irregular migrants to Croatia if they have entered Slovenia from Croatia, regardless of whether they requested asylum in Slovenia. In turn, Croatian authorities generally immediately pushed them on to Bosnia and Herzegovina or to Serbia.

EU institutions have effectively disregarded the human rights violations committed by Croatian border authorities. The European Union has contributed substantial funds to Croatian border management without securing meaningful guarantees that Croatia’s border management practices will adhere to international human rights norms and comply with EU law.

Moreover, the European Union’s decision in December 2022 to permit Croatia to join the Schengen area, the 27-country zone where internal border controls have generally been removed, sends a strong signal that it tolerates pushbacks and other abusive practices.

Croatia should immediately end pushbacks to Bosnia and Herzegovina and to Serbia and instead afford everybody who expresses an intention to seek international protection the opportunity to do so. Croatia should also reform its border monitoring mechanism to ensure that it is a robust and independent safeguard against pushbacks and other official abuse.

Until such time as Croatia definitively ends pushbacks and other collective expulsions, ensures that people in need of international protection are given access to asylum, and protects the rights of children, Slovenia should not seek to carry out returns under its readmission agreement with Croatia. Austria, Italy, and Switzerland, in turn, should not send people to Slovenia under their readmission agreements as long as Slovenia continues to apply its readmission agreement with Croatia.

Through enforcement of EU law and as a condition of funding, the European Commission should require Croatian authorities to end pushbacks and other human rights violations at the border and provide concrete, verifiable information on steps taken to investigate reports of pushbacks and other human rights violations against migrants and asylum seekers.

The European Union and its member states should also fundamentally reorient their migration policy to create pathways for safe, orderly, and regular migration.

Recommendations

To the Croatian Ministry of the Interior

· End pushbacks and other collective expulsions of people who indicate that they wish to seek asylum in Croatia.

· Allow people to claim international protection at the border or upon arrival in the country.

· Safeguard the right of every person to challenge any decision relating to their detention or deportation before a competent, impartial, and independent tribunal in an individualized, prompt, and transparent proceeding that affords essential procedural safeguards, in line with the recommendation of the United Nations special rapporteur on torture.

· Ensure that people who experience torture or other ill-treatment—whether in their home countries or en route—are identified as early as possible, have access to health care, including rights-respecting mental health care and psychosocial support, and receive redress.

· Require video recording of all border enforcement operations and the preservation of video footage to assist in investigating allegations of ill-treatment.

· Issue clear and unequivocal directives to police that ill-treatment, including any excessive use of force, contravenes Croatian and EU law and will not be tolerated, and require police to undergo training on relevant human rights norms.

· Refer any reports of excessive use of force, other ill-treatment, or other improper conduct by police to an independent authority for prompt, effective, and impartial investigation.

To the Croatian Police Directorate

· Direct police to wear identifying numbers during border enforcement operations.

· Forbid police from the routine wearing of balaclavas during border enforcement operations, and forbid the use of wooden sticks and other objects other than those issued by the police directorate.

· Require police to record every “interception” and “diversion” operation involving migrants, which at a minimum should include the time, precise location and a brief description of actions taken, the officers involved, the means used to “intercept” or “divert” people, the number of people “intercepted” or “diverted,” whether any means of restraint or use of force was applied and to how many people, and the outcome of the operation.

To the State Attorney’s Office

· Promptly and thoroughly investigate reports of pushbacks made by nongovernmental organizations or referred by the Croatian ombudsperson or the border monitoring mechanism.

To the Government of Croatia

· Reform the border monitoring mechanism so that it is independent in law and in practice, has sufficient resources and a robust mandate to monitor border-related operations anywhere on the territory of Croatia, is empowered to investigate cross-border violations even when victims are no longer on Croatian territory, and takes into account information provided or made publicly available by non-governmental organizations, media, and EU or UN agencies.

· Explicitly ensure that the border monitoring mechanism can refer reports of pushbacks and other human rights violations to the State Attorney’s Office for prompt and thorough investigation.

· Encourage the border monitoring mechanism to focus on conducting unannounced visits, which should pay particular attention to verifying respect for fundamental rights in the application of the Schengen acquis, and take into account evidence from the Croatian ombudsperson and nongovernmental and international organizations in the programming and design of evaluations.

· Cooperate with human rights oversight bodies of the United Nations and the Council of Europe, including UN special rapporteurs and the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT).

To the Government of Slovenia

· In recognition of the risk of pushbacks of asylum seekers by Croatian authorities to Bosnia and Herzegovina and to Serbia, limit Slovenia’s readmission agreement with Croatia to returns of Croatian nationals.

· Ensure that Slovenian police afford access to asylum to people who express an intention to apply or are in need for international protection.

· Ensure that Slovenian police accept a person’s declaration that they are under the age of 18 if there is a reasonable possibility that the person is a child. If they are unaccompanied, border police should transfer those individuals to the care of child protection authorities, assign them a guardian, give them access to an appropriate age determination process, and conduct a best interests determination. In no case should an individual be returned to Croatia if there is a reasonable possibility that the person is a child.

To the Governments of Austria, Italy, and Switzerland

· In recognition of the risk of chain pushbacks of asylum seekers from Slovenia to Croatia and on to Bosnia and Herzegovina and to Serbia, refrain from applying bilateral readmission agreements with Slovenia other than to people who are EU nationals.

To All European Union Member States

· All countries in the European Union should suspend the return of asylum seekers to Croatia under the Dublin III Regulation, which generally requires that the first EU country of arrival is responsible for a person’s asylum claim, until each of those countries definitely ends pushbacks and other collective expulsions.

· All countries in the European Union should create pathways for safe, orderly, and regular migration.

To the Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina

· Provide adequate staffing and other resources and the necessary political support to enable the Ministry of Security’s Sector for Asylum to register asylum claims and make refugee status determinations within the six-month period provided in the Law on Asylum.

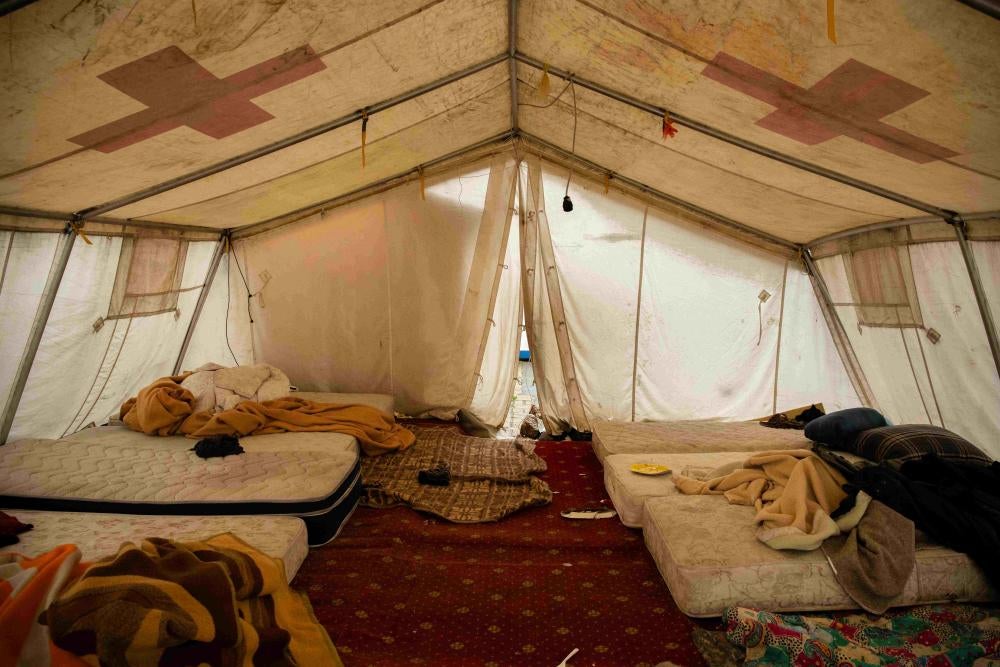

· Ensure that conditions in temporary reception centers for asylum seekers meet essential standards of habitability and provide food and other services that are appropriate for the age, health and disability needs, and culture of the people housed there. Temporary reception centers should be accessible by public transit and should not be unreasonably far from shops, schools, hospitals, and other essential services.

To the European Commission

· In line with the recommendation of the European ombudsperson, require Croatian authorities to provide concrete and verifiable information on steps taken to investigate reports of collective expulsions and mistreatment of migrants and asylum seekers.

· Press Croatia to end its violations of fundamental rights at its borders and provide solid evidence of thorough investigations of allegations of collective returns and violence against migrants and asylum seekers at its borders. In the absence of such evidence, the European Commission should consider opening legal proceedings against Croatia for violating EU laws prohibiting collective expulsions.

· Actively review and assess the border monitoring mechanism to ensure that Croatian authorities have in place a system that can credibly monitor compliance with EU law in border operations, and provide political and financial support only to a system that meets these conditions.

· Withhold migration management funding until Croatia demonstrates meaningful and sustained progress in ending pushbacks and abuses at its borders and make any future funding contingent on full and unhindered access of EU staff and other independent observers who monitor border operations.

To the EU Council and the European Parliament

· Ensure that the proposal by the European Commission to require EU member states to establish independent border monitoring mechanisms is adopted and that such mechanisms apply to all alleged fundamental rights violations by national border management authorities or during border control activities, are independent from border control or law enforcement institutions, proactively take into account information from other relevant sources, are designed to end abuses and ensure accountability at the domestic level, and publicly report on their findings and conclusions.

To Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency

· The executive director should ensure that Frontex operations in Croatia are consistent with its human rights obligations under the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and all applicable international human rights law, including the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (the European Convention on Human Rights), and that Frontex complies with its duty to avoid complicity in abuse.

· Frontex’s Fundamental Rights Officer (FRO) should monitor and publicly report on Croatian security forces’ compliance with European and international human rights and refugee law, as well as compliance by Frontex’s officers and those contributed by member states.

· The executive director should inform the Management Board and the Croatian authorities of Frontex's intention to trigger article 46 of its regulation, under which the agency has a duty to suspend or terminate operations in case of serious abuses, if no concrete improvements are made by Croatia to end these abuses within three months from the publication of this report.

· In considering whether to trigger article 46 of Frontex’s regulation on Croatia, or when examining concerns brought by the FRO, the executive director should consider allegations of abuse and reports from international and regional organizations, nongovernmental groups, civil society, and the media.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 105 people—all refugees, asylum seekers, and other migrants, staying in squats, encampments, or shelters, in transit, or sleeping on the streets. Interviews took place in and around Bihać and Velika Kladuša, Bosnia and Herzegovina; Rijeka, Croatia; Ljubljana, Slovenia; Oulx and Trieste, Italy; and Briançon, France. Most of these interviews were carried out in Bosnia and Herzegovina near the Croatian border during visits in November 2021, May and July 2022, and February, March, and April 2023. Twenty-one people identified themselves as unaccompanied children under the age of 18. Five were parents travelling with children under age 18, and twelve were children travelling with their parents or other family members. Most of those interviewed were from Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan. Other countries of origin included Algeria, Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Cuba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Guinea, Morocco, India, Nepal, and Turkey.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed aid workers, volunteers, and activists who distribute food, provide medical or legal services, or offer information and other support to asylum seekers and migrants.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews in English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese, in some cases with the aid of interpreters for people who did not speak those languages. We explained to all interviewees the purpose and public nature of our reporting, that the interviews were voluntary and confidential, and that they would receive no personal service or benefit for speaking to us. We also obtained oral consent from each adult interviewee and oral assent from each child interviewee.

This report uses pseudonyms for all migrant or asylum-seeking children and adults. In some cases, additional identifying information such as the precise location of the interview has also been withheld. Moreover, Human Rights Watch has withheld the names and other identifying information of some humanitarian workers who requested that we not publish this information.

In line with international standards, the term child refers to a person under the age of 18.[5] As the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child and other international authorities do, we use the term unaccompanied children in this report to refer to children “who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.”[6] Separated children are those who are “separated from both parents, or from their previous legal or customary primary caregiver, but not necessarily from other relatives,”[7] meaning that they may be accompanied by other adult family members.

This report uses refugee to mean a person who meets the criteria in the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. Under the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, a refugee is a person with a “well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion,” who is outside of the country of nationality and is unable or unwilling, because of that fear, to return.[8] People are refugees as soon as they fulfill the criteria in the Refugee Convention and Protocol. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) explains:

A person is a refugee within the meaning of the 1951 Convention as soon as he fulfils the criteria contained in the definition. This would necessarily occur prior to the time at which his refugee status is formally determined. Recognition of his refugee status does not therefore make him a refugee but declares him to be one. He does not become a refugee because of recognition, but is recognized because he is a refugee.[9]

The term migrant is not defined in international law; our use of this term is in its “common lay understanding of a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons.”[10] It includes asylum seekers and refugees, and the term migrant children includes asylum-seeking and refugee children.[11]

The report uses the term pushback to mean operations aimed at physically preventing people from reaching, entering, or remaining in a territory and which employ no or merely summary screening for protection needs. These operations may be conducted by state authorities or by individuals or groups acting at the behest of state authorities or under colour of law. This use follows the practice of the UN special rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, the UN special rapporteur on torture, the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, and other international and regional experts.[12] The Committee on the Rights of the Child uses pushback interchangeably with forced return,[13] and this report does the same.

I. Forcible Returns to Bosnia and Herzegovina

Pushbacks from Croatia to Bosnia and Herzegovina are both a longstanding phenomenon and an ongoing practice. The Danish Refugee Council recorded nearly 30,000 pushbacks from Croatia to northwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina between 2020 and the end of 2022—a number that it cautions is likely a significant underestimate.[14] Its teams in Bosnia and Herzegovina continued to record pushbacks as this report was being finalized in mid-April 2023.

Every humanitarian group operating in northwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina observed that the number of people transiting through the country had fallen throughout 2022 and early 2023, and that correspondingly fewer people were pushed back from Croatia. Even so, they observed that the number of pushbacks in 2022—nearly 4,100, according to the Danish Refugee Council—was still high in absolute terms, and almost certainly severely undercounted the total number of pushbacks from Croatia.[15]

The lower numbers of observed pushbacks in 2022 may in part be the result of variations in people’s routes through Bosnia and Herzegovina, for example to Banja Luka and then north to the Croatian border rather than through Bihać and Velika Kladuša. The lower numbers may also have resulted in part from Croatian authorities’ apparent reliance in the latter half of 2022 on summary but unenforced expulsion orders that effectively allowed people seven days to transit through Croatia to other EU countries.

But by March 2023, groups reported that Croatian police were again carrying out pushbacks and other mass summary expulsions to Bosnia and Herzegovina.[16] Some of these expulsions had a veneer of legality—Croatian police issued written decisions and expelled people at regular border crossings, using a “readmission” agreement with Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nevertheless, as with informal pushbacks and the unenforced “seven-day” orders, expulsions under the readmission agreement did not consider people’s individual protection needs, in violation of international norms. And in many instances, Croatian police made no effort to follow readmission procedures; instead, following their usual pushback practice, they simply ordered people to cross rivers or wooded or mountainous areas to enter Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Route to Bosnia and Herzegovina

Many of the people Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report had spent time in Turkey and Greece (as well as Iran, in the case of most Afghans and Pakistanis we spoke with) before travelling on through some combination of Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Serbia. Some described protracted efforts to find safety and stability at earlier points in their journeys. For instance, some people spent months or years in Iran, Turkey, or both in fear of deportation because they had been unable to register as refugees.[17] Many had sought asylum in Greece, the first EU country they reached, but said that they left after facing obstacles in access to protection, including summary rejection of their asylum claims or protracted periods waiting for resolution of their claims, as well as inhumane conditions in state reception facilities.[18] Many also said they had experienced pushbacks before arriving in Bosnia and Herzegovina, for example from Bulgaria or Greece to Turkey.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a country of transit for the overwhelming majority of asylum seekers and migrants who spend time in the country. Some of the people interviewed by Human Rights Watch had relatives or friends elsewhere in Europe and had a definite destination in mind when they began their journeys. Others told us they hoped to go to other countries based on language, perceived opportunities, or simply because they had heard something about those places before they left. A 9-year-old girl told us she had persuaded her family to try to go to Germany because she had read about it online. Several unaccompanied teenage boys, interviewed separately several months apart, said they had chosen their intended destination based on their favourite sports teams.

More frequently, people said they had a general desire to go to a country that they believed would provide safety and security for themselves or their children. Many said they appreciated the assistance they had received from ordinary Bosnians during their time in the country. But they did not believe that Bosnia and Herzegovina offered them a realistic prospect of a stable life.

Such assessments are well-founded. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s asylum system is ineffective, meaning that it is not an option for most people fleeing persecution. Only five people received refugee recognition in 2021, up from one in 2020 and three in 2019. On average, applicants waited 72 days just to register an asylum claim in 2022, a further 280 days to receive an interview, and 307 days for a decision on their claims, according to UNHCR.[19]

Until the end of 2021, camps for asylum seekers were overcrowded and did not afford adequate access to food, water, or electricity.[20] These camps held fewer people in 2022 and early 2023, and a new facility for adult men in northwest Bosnia and Herzegovina that opened in November 2021 offered better living conditions than the camp it replaced. Even so, people who stayed in the camps frequently noted that these facilities were not suitable for stays longer than a few days and did not always offer food or services that were culturally appropriate. Adult men who stayed in Lipa Camp, in northwest Bosnia and Herzegovina, also said that its distance from the closest urban center meant that they could not easily buy food or clothing, look for informal employment, or carry out other day-to-day tasks.

Moreover, some 100,000 people continue to be internally displaced as a result of the 1992-1995 war,[21] and, as the International Crisis Group observed in September 2022, the country has faced “three decades of post-conflict dysfunction and gridlock.”[22]

A Longstanding Phenomenon

Human rights groups have documented pushbacks from Croatia in significant numbers at least since early 2016,[23] as Croatia became an increasingly important country of transit for people seeking to travel irregularly to Western Europe.[24]

In particular, Hungary’s construction of a fence on its border with Serbia and imposition of other restrictions on the entry of refugees and migrants in late 2015 effectively rerouted people through Croatia, from where they could then seek access to Hungary.[25] In this context, the Croatian ombudswoman observed that she received an increasing number of complaints of summary returns to Serbia in 2016 and early 2017, including “allegations that Croatian police officers beat them with bats, made them take their shoes off and kneel or stand in the snow, made them pass through a cordon where they would be beaten and insulted.”[26] In January 2017, Save the Children estimated that an average of 30 people each day were facing pushbacks from Croatia to Serbia, including large numbers of children travelling alone and with families.[27] UNHCR recorded some 3,200 pushbacks from Croatia to Serbia in 2017 and more than 10,000 such pushbacks in 2018.[28] As in earlier years, pushbacks to Serbia in 2018 included significant numbers of children, Save the Children and Praxis, a Serbian organization, found.[29]

In likely the most widely publicized case of such a pushback to Serbia, Croatian police disregarded the asylum request made by an Afghan family, including a 6-year-old girl, Madina Hussiny, and ordered them to follow a set of train tracks into Serbia in November 2017. When the family complied, a train struck and killed Madina. The European Court of Human Rights relied on the extensive reporting on pushback practices by Croatia to conclude, despite the state’s forceful denials, that its authorities had pushed Madina and her family back to Serbia.[30] As two lawyers with the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights observed, the court’s reasoning “is an acknowledgement of the truthfulness—and credibility—of this body of reports but also of the Croatian state’s cover-up for such practices.”[31]

By 2018, Bosnia and Herzegovina had become a significant country of transit,[32] and pushbacks from Croatia to Bosnia and Herzegovina increased accordingly. The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights noted an “intensified” number of reports in 2018 of summary expulsions by Croatia to Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as to Serbia.[33] And over the course of 2019, the Border Violence Monitoring Network identified a trend of increasing violence by Croatian authorities during pushbacks to Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as to Serbia.[34]

An Ongoing Practice

The Danish Refugee Council recorded some 16,400 pushbacks from Croatia to Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2020 and 9,100 such pushbacks in 2021. In 2022, the Danish Refugee Council recorded nearly 4,100 pushbacks from Croatia to Bosnia and Herzegovina.[35] Croatian authorities also continue to carry out pushbacks to Serbia, including of unaccompanied children, other groups have reported.[36]

In 2022, one in four pushbacks recorded by the Danish Refugee Council was of a person from Afghanistan, and nearly one in four was of a person from Pakistan.[37] These countries of origin were also the most commonly reported in earlier years.[38] Bangladesh, Iran, Iraq, and Eritrea were the next most commonly reported countries of origin in 2020 and 2021.[39] In 2022, the third most commonly reported country of origin was Burundi (491 pushbacks, 12 percent of the total), followed by Iran (145, 3.6 percent), Bangladesh (139, 3.4 percent), India (131, 3.2 percent), Cuba (128, 3.1 percent), Cameroon (115, 2.8 percent), the Democratic Republic of Congo (101, 2.5 percent), and Iraq (96, 2.4 percent).[40] People from Burkina Faso, Cuba, Eritrea, Gambia, Guinea, Jordan, Morocco, Nepal, Senegal, Somalia, and Turkey also reported pushbacks during 2022 in smaller though notable numbers.[41]

Approximately 7 percent of recorded pushbacks in 2020 were of children, alone or with families. Children accounted for 12 percent of recorded pushbacks in 2021 and 13 percent in 2022.[42] Similarly, an analysis of Afghans who reported pushbacks from Croatia to Bosnia and Herzegovina between August and November 2021 found that just over 13 percent were children.[43]

Figure 2: Pushbacks from Croatia to Bosnia and Herzegovina, by Age and Gender

|

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

Men |

14,681 |

7,527 |

3,101 |

|

Women |

514 |

526 |

437 |

|

Boys in families |

490 |

500 |

212 |

|

Girls in families |

307 |

366 |

168 |

|

Unaccompanied children* |

431 |

205 |

156 |

|

Total |

16,423 |

9,124 |

4,074 |

* Nearly all unaccompanied children are boys, but the Danish Refugee Council has occasionally recorded some pushbacks of unaccompanied girls. For instance, the Danish Refugee Council reports 2 pushbacks of unaccompanied girls and 35 pushbacks of unaccompanied boys in September 2020. Source: Danish Refugee Council (DRC), Border Monitoring Factsheets, March 2021-December 2022; DRC, Bosnia and Herzegovina Border Monitoring Bimonthly Snapshot, January/February 2021; DRC, Border Monitoring Monthly Snapshots, January-December 2020

Because Danish Refugee Council staff do not meet every person who has experienced a pushback, these numbers likely understate the true number of pushbacks carried out by Croatian authorities to Bosnia and Herzegovina; they also do not include pushbacks to other countries.[44] Based on accounts it has collected of pushbacks to Serbia and Montenegro as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Border Violence Monitoring Network estimates that Croatian authorities push back more than 20,000 people each year.[45]

Nevertheless, the data collected by the Danish Refugee Council match the general observations Human Rights Watch heard from staff of nongovernmental organizations and volunteers with humanitarian groups, including in the following respects:

· People attempt to enter Croatia irregularly from Bosnia and Herzegovina and are pushed back throughout the year; however, irregular crossings are less frequent, and the number of pushbacks is lower from November to February.

· The vast majority of people pushed back are adult men, most of whom are between the ages of 18 and 30.

· Families with children and unaccompanied children also regularly face pushbacks.

· Many of those pushed back, regardless of age or gender, reported that they have faced multiple pushbacks, sometimes dozens.

Other Forms of Summary Expulsion

Humanitarian and human rights groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy received fewer accounts of pushbacks by Croatian authorities in the months before Croatia’s admission to the Schengen area in January 2023.[46] Their observations matched the accounts Human Rights Watch heard between May 2022 and early 2023.

Instead, Croatian authorities increasingly employed other measures that amounted to summary and often collective expulsion, without consideration of individual protection needs.

In the second half of 2022, in one such tactic, Croatian police frequently issued people summary expulsion orders giving them a seven-day deadline to leave the European Economic Area.[47] People who received these orders told Human Rights Watch that Croatian police did not allow them to explain their circumstances or to request asylum, did not explain the process or the nature of the order, did not say if they had an opportunity to be represented or to seek review of the order, and did not provide translations of the order in the languages they understood best. In fact, nearly everybody Human Rights Watch spoke with understood the papers they received to be a seven-day permit to transit Croatia.[48] “It was clear that the intention of Croatian authorities was to prompt people to exit the country in any direction, regardless of whether they left the European Economic Area or simply travelled onward to other EU countries,” said Urša Regvar, a legal adviser with the Legal Center for the Protection of Human Rights and the Environment (PIC) in Ljubljana.[49]

In late March 2023, Croatian police also made increasing use of the EU readmission agreement with Bosnia and Herzegovina. Between March 23 and April 6, Croatian authorities transferred 559 people to Una-Sana Canton, in northwest Bosnia and Herzegovina.[50] Croatian authorities have also made transfers under the readmission agreement to Gradiška and Orašje, municipalities on Bosnia and Herzegovina’s northern border near the Croatian town of Slavonski Brod.[51]

In addition, Croatian authorities have begun to tell some people that they owed significant fines for their time in detention prior to their expulsion. For instance, Urša Regvar has reviewed documents in which Croatian authorities assessed charges of nearly €800, purportedly to cover the cost of their detention.[52]

II. Violence, Humiliation, and Other Abuses During Pushbacks

The police came. They had us remove our clothes. They took our phones. They searched us. We said we want to seek asylum in Croatia. We said we needed medical attention. They said, “Go.” They deported us with no consideration of our situation. This was the fifth time this has happened to us.

—Stephanie M., a 35-year-old woman from Cameroon, interviewed in Velika Kladuša, Bosnia and Herzegovina, May 25, 2022

When the police caught us the first time we tried to cross into Croatia, in October 2020, they attacked me and my father, beating us. I told them my mother was very sick and needed to go to a hospital. The police spoke really harshly to us: “Go to Bosnia. Go back. We are the police, not doctors. Go to Bosnia, you motherfucker. Why have you come to Croatia?”

—Farhad K., a 21-year-old Iranian man travelling with his parents and 14-year-old sister, interviewed in Šturlić, Bosnia and Herzegovina, November 27, 2021

Describing a pushback in November 2021, Laila R., the 16-year-old girl from Afghanistan whose account opens this report, said, “Some people were beaten really badly. The Croatian police took everybody’s phones and broke them. They burned our stuff in front of us. They were shouting at us, saying, ‘We don’t want you in this country, go back to Bosnia!’”[53]

Laila and her family experienced many such pushbacks over the course of 10 months, she told Human Rights Watch. Her account was typical of those we heard. Many of the people interviewed by Human Rights Watch described five or more pushbacks by Croatian authorities—in some cases, dozens.

Pushbacks harm everyone, whether they are men travelling alone, women with or without partners, children travelling with their families, or unaccompanied children. But families with young children often told Human Rights Watch they had spent extended periods in transit, likely reflecting the limits they faced because of when and how fast they could travel, the routes they could take, and other conditions of their journey. “It’s very difficult to move with a large family,” Rozad N., a 17-year-old Kurdish boy from Iraq, told us. “It’s difficult in every possible way.”[54]

People who had health conditions or were living with disabilities said Croatian police pushed them back without regard to their circumstances. Mahdi F., from Iran, told us he and his wife had been pushed back several times, including the night before we spoke, even though his wife used crutches and walked very slowly.[55] Others described having to carry relatives—in one case, on a stretcher[56]—as they followed the orders of Croatian border police to re-enter Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The likelihood of being pushed back while trying to enter Croatia and travel onward to other EU countries is so high that many people ironically refer to the attempt as the “game.” “We call it the ‘game’ because only a few of us are able to reach [our destinations],” a 33-year-old Pakistani man, Mustafa Q., told Human Rights Watch.[57]

Croatian border police have often beaten men and teenage boys during pushbacks. For example, Dawar F., a 20-year-old Afghan man interviewed by Human Rights Watch the morning he entered Italy after crossing Croatia and Slovenia, said that on each of the 10 times Croatian police pushed him back to Bosnia and Herzegovina, they punched and kicked him and other men and boys.[58] Sarim H., a 26-year-old from Pakistan, said Croatian police hit him with their batons on each of the four times they pushed him back in March and April 2023.[59] Hasan F., a 15-year-old boy from Afghanistan, told us that during a pushback in April 2023, “One of the police kicked me hard on my right side. Why did they do this? I wasn’t running from them. I was sitting on the ground following their orders.”[60] Human Rights Watch also heard of some instances in which Croatian police subjected women and younger children to physical violence.

Croatian police commonly take or destroy mobile phones and power banks (battery packs to recharge phones) and in some cases have also taken or destroyed money, backpacks, and other property. “The last time we were pushed back, the Croatian police burned all our stuff. I told them they were thieves,” Laila said.[61]

Some men and boys also reported that Croatian police ordered them to remove their shirts and shoes—and in a few cases to strip down to their underwear—before ordering them to walk through the forest and cross the international border, which frequently runs along a river or stream. Some of these cases took place in the early spring or late autumn, when night-time temperatures were in the range of 4 degrees Celsius or lower.

There is no reason to doubt that Croatian police are responsible for pushbacks to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Describing the men who pushed him back to Bosnia and Herzegovina on the ten unsuccessful attempts he made to enter Croatia in late 2021 and early 2022, Dawar F. said, “The men who did this were police in uniforms. The uniforms had the word policija [‘police’] on them, and the men said they were Croatian police.”[62] Osman L., 26, gave a similar description of the men who pushed him back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in November 2020, saying, “They wore black uniforms and badges. Their shirts said ‘police.’ They had a patch with the Croatian flag on the shoulder. I recognized the Croatian badge.”[63] Farhad K. said, “They wear blue or sometimes black uniforms with a shield on the arm. Sometimes they have a name tag. Sometimes their faces are covered.”[64] Firooz D., a 15-year-old Afghan boy, said the police who pushed him and another 15-year-old back in April 2023 wore dark blue uniforms and had shoulder patches that he recognized as Croatian.[65] And Laila R. told us, “They wear police uniforms that have marks on the chest and back. They say policija. There is a patch on the arm.”[66] Their accounts are typical of those we heard.

In addition to physical injuries, pushbacks inflict considerable mental trauma. Children and adults alike described harm to their mental well-being that they attributed to repeated pushbacks. “It is so stressful. I don’t understand why the Croatian police have to do these things to us,” Stephanie M., 35, from Cameroon, said.[67]

Human Rights Watch’s findings are consistent with reporting by journalists, human rights and humanitarian groups, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT), and other official entities. These reports document strikingly similar tactics, including beatings and other violence, often administered as people are forced to run between a row of police wielding batons and other objects; the destruction or theft of personal property, particularly mobile phones; frequent theft of money; forcing people to remove shoes and other clothing before crossing rivers to re-enter Bosnia and Herzegovina; and rejection of all efforts to seek asylum.

In combination, these consistent reports leave little room to doubt that Croatian authorities regularly engage in pushbacks to Bosnia and Herzegovina, in violation of international and EU law.

Beatings and Other Ill-Treatment

Human Rights Watch heard frequent accounts of physical violence and other degrading treatment by Croatian border police during pushbacks.

Many of the adult men we interviewed for this report described being beaten by Croatian police during a pushback to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nearly everybody we spoke with—children as well as adults, without exception—who said they had experienced a pushback also said they had witnessed somebody being beaten by Croatian police at least once. “They look at you like you’re not human,” said Zafran R., a 28-year-old man, going on to describe the beatings he faced from Croatian police.[68] “The beating is part of the process,” Darius M., an 18-year-old from Iran, said matter-of-factly.[69]

For example, in May 2022, Imran S., a 28-year-old man from Pakistan, pointed out bruises on his chest, telling Human Rights Watch that Croatian police had apprehended him the night before. “They told me to get down, and then one of them kicked me hard, twice,” he said.[70] Two other men who told Human Rights Watch they were apprehended at the same time said they saw a Croatian border agent kick the man hard in the chest.[71]

Osman L., a 26-year-old man from Pakistan, also said Croatian police beat him and other men in 2021 after ordering them to lie on the ground: “We were travelling in a group of 10 people when the Croatian police caught us. They made us lie flat with our palms up. Then they started to beat us one by one. One police officer also kicked us in the face.”[72]

Similarly, Rashid L., a 31-year-old man from Pakistan, said that when Croatian police pushed him and others back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in May 2022, “They punched and kicked me. They beat me on my legs, back, shoulders, chest.”[73] Zalmay T., a 24-year-old man from Afghanistan, told Human Rights Watch, “The Croatian police punched me and kicked me in the back” when they pushed him back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2021.[74] Joseph C., a 40-year-old man from Cameroon, told us Croatian police had kicked and punched him during a pushback in 2022.[75] Farhad K., 21, said Croatian police had kicked him during many of the two dozen pushbacks he and his family had faced.[76]

Teenage boys receive much the same treatment as adult men, we heard. For instance, Laila R. told Human Rights Watch:

The Croatian police will just start beating the men and boys, even young boys, without any reason. One time they stopped the van and told us to get out, all but one boy. They didn’t let that boy out. They shouted at us, “Go over there or we’ll burn your stuff.” We waited where they told us for maybe 20 minutes. Then we saw they had beaten that boy and taken his shoes and jacket. It was raining hard that day, and the boy had to walk back into Bosnia with no shoes and just a t-shirt.[77]

Describing his treatment by Croatian police during a July 2022 pushback, Antonin G., a 17-year-old Burundian boy, said, “They made me put my hands up, and then they swung their batons and hit me.”[78] Mamadou B., 15, and Aboubacar L., 14, both from Guinea, told us Croatian police kicked them and hit them with batons before telling them to go back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in July 2022.[79] Firooz D. and Hadi A., both 15 and from Afghanistan, said police kicked them several times before pushing them back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in the early hours of the morning we spoke to them in April 2023.[80] Saqib I., 18 at the time of our interview, said Croatian police beat him when they pushed him back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2021, when he was 17.[81] And Ali S., 22, said that during one 2021 pushback, Croatian police were particularly brutal toward a 14-year-old Afghan boy in the group. “They beat him really badly,” Ali said.[82]

Some people told us that police singled out men and boys who tried to conceal phones or other property. In one such case, Laila said that police had beaten a teenage boy for trying to conceal his phone. “He said he didn’t have a phone, but the police found it when they searched him. They started beating him badly,” she said.[83]

A medical student volunteering with Strada SiCura, an Italian humanitarian group, said that during a visit to Bosnia and Herzegovina in April 2022, he saw many injuries that corresponded with the accounts he heard of people being beaten by police:

I saw broken ribs, lots of injuries on the legs consistent with kicks, bruising on the face or elsewhere on the head that matched accounts of being punched. One person had a burn, a square burn mark in a line down the chest, that looked like it may have been caused by an electrical device.[84]

We also heard accounts of people who required hospitalization and took protracted periods to recover after beatings during pushbacks. In one such case, 19-year-old Ibrahim F., from Cameroon, said Croatian police beat him so badly during a December 2021 pushback that he could not walk for two months.[85]

Some people said Croatian police threatened them with serious injury if they attempted to reenter Croatia. For instance, Ciran H., an Iraqi man travelling with his wife and 9-year-old son, related, “The police told me, ‘If you come back, we will break your hands and your legs.’”[86] In another such account, Firooz D., a 15-year-old boy from Afghanistan, told Human Rights Watch that when Croatian police pushed him and another 15-year-old boy back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in April 2023, “They said if they caught us again, they would really beat us.”[87]

Many who described pushbacks they experienced said that Croatian police did not usually subject women, girls, and younger boys to physical violence. For example, Farhad K. told us, “Sometimes they kick or hit me and my father, but they never hit my mother or my sister.”[88]

But children see their parents, older siblings, and other adults being beaten, exposing them to violence in ways that have been associated with increases in depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.[89] Seywan A., a 34-year-old Kurdish man from Turkey, travelled with his extended family, 11 in all, through Croatia on their way to Western Europe. He said, “We were beaten in Croatia and returned illegally to Bosnia. The Croatian border guards beat me in front of my children.” Most of the adult men and older boys were beaten during pushbacks, he told us. Reflecting on his own experience, he added, “It was like being in a fight club.”[90]

In another of the many similar accounts we heard, Edward C., a Cameroonian man, told us that on one attempt to enter Croatia, “there were children with us when the Croatian police caught us. They started beating us. It was unfair. There were children watching. I objected, and the police just beat me more. They beat us in front of the children. That is not right. That was not good for these children.”[91]

We also heard some accounts that Croatian police had subjected women and girls to sexual harassment or abuse. For instance, Emmanuel J., from Ghana, said that when Croatian police apprehended the large group he was travelling with in May 2022, including eight women, several police “were harassing the ladies. They were touching the ladies’ private parts.”[92]

Laila R.’s earlier account of Croatian police forcing a boy to walk into Bosnia and Herzegovina barefoot and without a jacket was not unusual. We heard many other accounts from people who said Croatian police took their shoes and other clothing, regardless of the weather or the season, before pushing them back to Bosnia and Herzegovina. For instance, 17-year-old Amir G. said Croatian police usually took his shoes in addition to beating him during the nearly two dozen pushbacks to Bosnia and Herzegovina he faced.[93] Osman L., a 26-year-old man from Pakistan, said Croatian police made him and the other men he was travelling with remove their shirts and shoes before telling them to return to Bosnia and Herzegovina.[94] Edward C. said, “The Croatians took everything before they forced us back to Bosnia. I was just in my underwear. They made us cross a river. The water was up to my belly. It was very cold, and I was wearing nothing but my underwear.”[95]

Some people said they had seen a change in the behaviour of Croatian police in 2022, describing less violence by police, instances in which their possessions were returned instead of destroyed, and in some cases courteous interactions.[96] Imran S., a 28-year-old Pakistani man, said, “Some police are good. They return everything when they send us back to Bosnia.”[97] If these experiences reflect a more general development, that change is positive as far as it goes but also reveals the diminished expectations many people have of Croatian border police: as discussed in the following chapter, Croatian authorities do not assess individual protection needs before forcibly returning people to Bosnia and Herzegovina, in violation of human rights norms and EU law.

Moreover, these few positive accounts stand in contrast to those who described violence during pushbacks throughout 2022, suggesting little overall change in Croatian border policing practices. During a pushback in May 2022, for example, Stephanie M., a 35-year-old Cameroonian woman, said that Croatian police beat many of the men in the group. “After they took our mobiles and our things, they started kicking the men,” she told us.[98] And in July 2022, Éric J., a 24-year-old man from Cameroon, said that Croatian police hit him and the other members of his group—including several 15- and 16-year-old boys—on the legs during a pushback the previous week. In addition, he said, “One of the police pointed a gun at my head and said, ‘I will shoot you if I catch you again.’”[99]

Destruction or Theft of Phones and Other Property

Human Rights Watch consistently heard that Croatian border police destroyed or confiscated and failed to return personal property during pushbacks.

Phones and power banks (battery packs to recharge phones) are a particular target for Croatian border police. In many cases, we heard, Croatian police destroy phones and power banks in front of people before pushing them back to Bosnia and Herzegovina. For instance, the first time 16-year-old Laila R. and her family entered Croatia and were apprehended by border police, “the police asked for our phones, and right in front of us they smashed all our phones.”[100]

In many other cases, people told us Croatian police seized and did not return phones before pushing people back. For example, 17-year-old Mansoor K., from Afghanistan, said that Croatian police took his phone and did not return it before pushing him back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in April 2023.[101] Rozad N., 17, said that the first time he and his family entered Croatia:

A policeman took my phone from me and put it in his pocket. It was my first game, so I was surprised. I said, ‘What are you doing? That’s my phone.’ He said, ‘Oh, it was yours. Now it belongs to me.’ I didn’t understand what was going on. I started yelling, and he beat me.[102]

Since that time, he has regularly seen police take phones:

They make you open the phone, and they go to the maps to see what you’ve marked. They check the photos. They look to see if there are any group chats. They want to see if you have had any contact with smugglers. Then, if they like the phone, they make you enter the code so they can restore all the factory settings, and they keep it.[103]

Similarly, Arsal G., a 20-year-old Afghan man we spoke with in Italy and then a few days later in France, explained, “Before the Croatian police deport you, they take things. They look at your phone. If it’s new, they make you reset it, and they put it in their pocket. If it’s not new, they break it.”[104]

It is also common for Croatian border police to steal money from the people they push back. During a pushback in April 2023, for instance, Croatian police took €300 from Nasim H. and €170 from Amin B. before ordering them to return to Bosnia and Herzegovina.[105] Firooz D., a 15-year-old Afghan boy, told us police took €500 from him during a separate pushback in April 2023.[106] Similarly, Omar T., a 66-year-old Tunisian man, told us Croatian police took money from him and others before pushing them back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in early February 2023: “I had €30, so the police took that. I saw them take €50 from others, €100 from some, €20 or €40 from some other people, whatever people had. The police did not return this money when they pushed us back.”[107] In fact, theft of money during pushbacks is so common that Ahmad H., from Pakistan, commented, “Every time I try to cross into Croatia, I know the Croatian police will take at least €100 if they catch me.”[108]

In some cases, Croatian police set money on fire after taking it from people. Nadeem S., a 26-year-old Pakistani man, said that the last time Croatian police pushed him back to Bosnia and Herzegovina, in May 2022, they took €300 from him and burned the money in front of him. They also seized his group’s phones, placed them in a row on the ground, and shot them to destroy them.[109] Yasser D., also age 26 and from Pakistan, said Croatian police burned the €400 he was carrying when they apprehended him on a different day that same month.[110]

It is also common for Croatian police to burn backpacks and everything they contain, we heard. “They take your documents and everything you have and put it in the fire. They burn all your stuff,” Kamran S., an Iranian man, said.[111] “The last time, they burned all of our stuff,” Laila R. told Human Rights Watch in November 2021.[112]

Among the many other accounts we heard of Croatian police destroying or taking and not returning property during pushbacks:

· Farhad K. said Croatian border police smashed his phone before forcing him and his family to wade across the river into Bosnia and Herzegovina in October 2021. Croatian police had taken their phones during earlier pushbacks between October 2020 and October 2021, he told Human Rights Watch.[113]

· Mahdi F., a 38-year-old man from Iran, said that when Croatian police apprehended him near the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, “they took my phone charger from me, and they took my documents and burned them in front of me before beating me.”[114]

· Ciran H., an Iraqi man travelling with his wife and 9-year-old son, said that Croatian police destroyed his SIM card when they entered Croatia in May 2022.[115]

· Ahmad H., a 20-year-old man from Pakistan, said that before Croatian police pushed back his group—eight people in all—in May 2022, they confiscated phones and battery chargers.[116]

· Imran S., 28, also from Pakistan, told us that Croatian police pushed him and 14 others, including children, back in May 2022, saying, “The police took everything we had first: mobiles, money, backpacks, clothes, even shoes.”[117]

· “They took my phone and power bank,” said Rashid L., a 31-year-old man from Pakistan, describing a pushback he faced in May 2022.[118]

· “They took our phones when they took us back to the border. I don’t know what they did with our phones,” said Dawar F., a 20-year-old Afghan man.[119]

· Seventeen-year-old Amir G. said that Croatian police confiscated phones and other property from him and others during each of 23 pushbacks he faced, most recently the week before he spoke to Human Rights Watch in November 2021.[120]

· Describing a pushback in late May 2022, Emmanuel J., a 25-year-old Ghanaian man, said, “The Croatian police took €200 and my phone from me. In our whole group [of more than twenty], only one person was able to keep his phone.”[121]

· Pierre M., a 30-year-old from Burundi travelling with his 16- and 17-year-old brothers, said Croatian police took his phone and €500 when they pushed the family back to Bosnia and Herzegovina in June 2022.[122]

· Omar T., a 66-year-old man from Tunisia, and Hossam D., a 33-year-old from Morocco, each said that Croatian police had taken their phones, power banks, and chargers during separate pushbacks in February 2023.[123] Hakim F., a 35-year-old from Algeria, said Croatian police did the same when they pushed him back in January 2023.[124]

· Rozad N., 17, told us, “They always take my phone and power bank. Now I leave my phone in the middle of the jungle somewhere close to the place where we cross.”[125]

It is particularly pernicious for Croatian police to confiscate or destroy physical documents and digital information. As Urša Regvar, a legal adviser with the Legal Center for the Protection of Human Rights and the Environment (PIC) in Ljubljana, observed, “People can change their phones and find new clothes. But the most disturbing part is that Croatian police will destroy documents on the phone that people could use to prove their country of origin. They also destroy originals of documents.”[126]

Dumped at the Border

We heard many accounts of Croatian authorities carrying out pushbacks far from urban centers, often in the middle of the night and in locations unfamiliar to the people who are pushed back. Describing what happened the first time she and her family tried to enter Croatia, in March 2021, Laila R. said:

After 30 minutes, a vehicle came. They called it a deportation car. It was a van, and when they opened the door it was like a jail inside, with bars on the glass. They drove us somewhere. It was at night, so we didn’t know where we were. They stopped and said, “Go straight ahead, that’s Bosnia.” We spent the night in the forest and found our way to a town the next day.[127]

In a similar account, Stephanie M., from Cameroon, told us, “When they deport us, they take us somewhere far, far away. When we cross into Bosnia, we are confused. We don’t know where we are or what we can do. We are stranded in the middle of nowhere.” She said she and her family had been pushed back from Croatia five times in this manner in 2022.[128]

Croatian police do not transfer people to the custody of authorities of Bosnia and Herzegovina during pushbacks. “When the Croatian police deport us, they don’t hand us over to Bosnian police. They just tell us to walk into Bosnia. Sometimes they make us cross rivers,” Farhad K. said.[129]

Urša Regvar, the PIC legal adviser, explained:

Pushbacks are completely unofficial procedures. They do not go through Bosnian authorities. They just physically take people to the border; there is no procedure. They order people to cross. There are no Bosnian police on the other side to meet people. These procedures are not based on any legal ground.[130]

Consequently, people may find themselves stranded in an unpopulated area with no idea of where they are, and in some instances without water or adequate clothing, when they arrive in Bosnia and Herzegovina after being pushed back from Croatia. Seventeen-year-old Rozad N. described what he and his family faced:

The police took us in a van and drove for two-and-a-half hours. Then they stopped and made us get out. They said we had to go back from here. We were in a very bad situation. We had no food or water. No phones, no power bank, no money. We were completely empty-handed.[131]

Not only do Croatian police frequently make people cross at unfamiliar points along the border, but they often also do so at places that are far from towns or main roads. Laila R. told us, “They put everyone in a car and drive so fast. When the car stops, they make you walk into Bosnia. They take us someplace really far away. You have to walk back to Velika Kladuša. It takes a really long time.”[132] Farhad K., a 21-year-old Iranian man, said Croatian police pushed him and his family back to Bosnia and Herzegovina about 30 kilometers from Velika Kladuša, the town in Bosnia and Herzegovina from which they had entered Croatia.[133] Sorush B., a 38-year-old man from Iran, gave a similar account.[134]

Croatian authorities also carry out pushbacks at any time of the day or night. “The last time the police pushed us back, it was at midnight. We pleaded with them to let us at least cross the border in the daylight. They just said, ‘Go,’” said Marie D., a 30-year-old woman from Cameroon, in one of many such accounts we heard.[135]

Multiple Pushbacks

Most of the people interviewed for this report said they had experienced multiple pushbacks, sometimes dozens. For instance, Rozad N. told us he and his family, including his 7-year-old brother and 9-year-old sister, had been pushed back between 45 and 50 times over the previous two years.[136] Darius M., an 18-year-old Iranian man, said he was pushed back 33 times in 2020 and 2021, including when he was 17.[137] Farhad K., 21, from Iran, told us Croatian police had pushed him, his parents, and his 14-year-old sister back more than two dozen times.[138] Amir G., a 17-year-old from Pakistan, said he had been pushed back from Croatia 23 times.[139] Kamran S. said he had been pushed back 15 times.[140]

Some people had been pushed back so many times they had lost count. “I have tried to cross into Croatia so many times I can’t remember how many,” Marjan B., a 24-year-old man from Afghanistan, told Human Rights Watch.[141] We heard the same from Tariq A., a 22-year-old Pakistani man.[142]

Harm to Mental Well-Being

Many of the people we spoke with, particularly those who experienced repeated pushbacks, said that the ill-treatment they faced from Croatian police took a significant toll. “These pushbacks have been so traumatizing. I find I cannot sleep. I am always thinking of the things that have happened, replaying them in my head. There are days I cry, when I ask myself why I am even living. I find myself thinking, ‘Let everything just end. Let the world just end,’” Stephanie M., the 35-year-old Cameroonian woman, told Human Rights Watch.[143]

“Why do they treat us this way? It is not right. Don’t send us back. Don’t frustrate us like this. Now I have no money. I have no food. How do I survive?” Emmanuel J. asked. He added, “Yesterday night one man wanted to kill himself” after Croatian police pushed the group back to Bosnia and Herzegovina.[144]

Edward C. said he was dealing with trauma months after he reached Slovenia. He explained:

I do not sleep at night. I have nightmares. When I see a police officer, I need to stop and get a hold of myself. Every day I go through this. My way of looking at life is totally different now. Now I don’t have anyone I trust. I don’t see people as friends, I see them as people who might be enemies. I feel like I always have to be careful, I always have to be on guard. Unexpected sounds affect me. I’m always alert. I’ll be sleeping but not really sleeping. I startle quickly. I know I’m not the only one going through this. I’m depressed more than I was before the pushbacks. I feel unsafe.[145]

Lorena Fornasir, a retired doctor who is one of the founders of Linea d’Ombra, a humanitarian group in Trieste, observed that being turned back from the European Union and the often-brutal manner in which pushbacks are carried out has left many people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “The young people have a lot of resilience, but they have gone through a lot of stress and a long journey,” she said.[146] Her observations match the findings of a 2023 study of refugees in Serbia, which concluded that those who had faced pushbacks from Croatia “showed overall higher levels of depression, anxiety, and PTSD.”[147]

A Pattern of Abuse

The accounts Human Rights Watch heard in 2021, 2022, and 2023 are strikingly similar to the practices we identified in earlier years and are consistent with reporting by journalists, nongovernmental organizations, and EU and UN experts.

For example, in a particularly well-publicized case, Lighthouse Reports, an investigative journalism group, published videos in October 2021 of masked men forcing a group of men from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina.[148] Interviewed in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the men said police had taken their shoes, jackets, money, and mobile phones before beating them, and they pulled up their shirts to show reporters their backs, covered in bruises.[149] Immediately after other pushback operations, the Lighthouse Reports investigative team observed photos, SIM cards, backpacks, medication, and other items set on fire and left to burn in metal barrels.[150]

The Lighthouse Reports investigation concluded that this violent pushback was carried out by Croatia’s Intervention Police (Interventna Policija) as part of an initiative known as “Operation Corridor.” A detailed analysis of the video included the following observations:

The masked men wear dark blue uniforms during the pushbacks. Their quilted underjacket is clearly visible in the video. It’s the same as the Intervention Police model: diamond-shaped quilting, sealed vertical zippers on the sides. The men’s batons, called tonfa, have a distinctive cross-handle. It is part of the official equipment of the Intervention Police.[151]

Later in the video, “[t]he pictures show a police officer in action, this time without a mask. On his back is clearly written ‘Interventna Policija,’ Intervention Police.”[152]

In addition, six Croatian police officers concluded that the videos showed members of the intervention police, and Lighthouse Reports interviewed a member of the Intervention Police who said that he took part in Operation Corridor and described substantially similar treatment toward other people who had entered Croatia irregularly.[153]

Faced with this evidence, Croatia’s Ministry of the Interior confirmed that those responsible for the pushbacks were members of the police force.[154] Three police officers received suspended sentences—not for physical violence or denial of access to asylum, but for wearing their uniforms inside-out.[155]

The methods used during the pushback analyzed by Lighthouse Reports are strikingly similar—and in many respects identical—to reports of pushbacks documented by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT), other official entities, numerous human rights and humanitarian groups, and journalists over the past half-decade.

When the Committee for the Prevention of Torture visited Croatia in 2020, for example, it heard numerous accounts that Croatian police had inflicted “slaps, kicks, blows with truncheons and other hard objects” on people who had entered Croatia irregularly from Bosnia and Herzegovina.[156] The committee reported that it continued to receive reports of abuses that matched the accounts it heard in its August 2020 visit:

[I]n the period since the visit, the CPT has continued to receive credible allegations of severe ill-treatment of exactly the same nature as that established by its delegation during the visit. By way of example, on 16 October 2020, the Committee received very detailed allegations, supported by new photographic material, concerning the recent ill-treatment by Croatian police officers of a number of migrants who credibly claim to have been subjected, inter alia, to multiple baton blows. They also stated that they had been subject to verbal abuse and degrading treatment such as being forced to walk across the border into BiH [Bosnia and Herzegovina] in only their underwear.[157]

The children’s ombudsperson of Croatia has received similar reports from unaccompanied children.[158] The Zagreb-based Centre for Peace Studies (Centar za Mirovne Studije, CMS) has documented pushbacks against pregnant women and other people with reduced mobility.[159]

The reports of these and other groups include “consistent and substantiated”[160] details of the following abusive practices by Croatian authorities:

· Slapping, punching, kicking, or striking people with batons, guns, branches, and other objects,[161] including while being forced to run a gauntlet,[162] surrounded,[163] or forced to lie face down on the ground.[164] Some of the men and boys interviewed by these groups showed investigators injuries consistent with their accounts of being struck by fists,[165] truncheons,[166] branches,[167] whips,[168] the butts of guns,[169] or other objects.[170] Some people reported that asking for directions or for the return of possessions prompted beatings[171] and that attempting to protect themselves during beatings,[172] stating that they are under the age of 18,[173] or being the person who communicated requests for their group[174] provoked increased violence. In some instances, people reported that one or more Croatian police officer beat them while another officer restrained them.[175]

· Beating parents in front of their children.[176] “The most common patterns of abuse witnessed by children were beatings with police batons,” the Border Violence Monitoring Network observed in a comprehensive report of pushback practices issued in December 2022.[177]

· Using electroshock devices on people.[178]

· Setting dogs on people[179] or threatening to do so.[180]

· Discharging firearms close to people while they lay on the ground[181] or while tied to trees,[182] or firing in the air.[183]

· Threatening or appearing to threaten to shoot people,[184] including unaccompanied children,[185] or otherwise pointing weapons at people.[186]

· Tying people to trees.[187]

· Throwing or pushing people into the river with their hands ziplocked.[188]

· Making boys and adults remove shoes and other clothing—in some cases, all clothing—and then ordering them to walk through the forest and cross the river into Bosnia and Herzegovina.[189]