Summary

On April 3, 2022, Hungary’s ruling Fidesz party won a fourth term in national elections, cementing its dominance with a two-thirds majority that will allow it to continue traveling what critics of the party and many others would describe as the path of centralizing power and rolling back democratic safeguards. International observers characterized the elections as free but raised serious concerns about their fairness. These included blurring the lines between the government and the ruling party in campaigning, which amplified the advantage of the ruling coalition, the absence of a level playing field, and lack of balance in campaign coverage in the press, on television, and on billboards.

Fidesz’s effective control over large sections of the media, undermining the independence of the judiciary and public institutions, and curbing of civil society has received considerable attention from international media and international observers. However, its misuse of people’s personal data, which helped the party reach voters in new, opaque ways, has received relatively little scrutiny. This report examines how data-driven campaigning in Hungary’s 2022 elections exacerbated an already uneven playing field and undermined the right to privacy. It also documents new forms of misuse of personal data collected by the government and used for political campaigning by Fidesz in the 2022 elections.

In recent elections, parties across the political spectrum in Hungary, as in other countries, have invested in data-driven campaigning, including building detailed voter databases, running online petitions and consultations to collect data, purchasing online political ads, deploying chatbots on social media, and conducting direct outreach to voters and supporters through robocalls, bulk SMS messaging, and emails.

Such use and exploitation of data helped to undermine privacy, and the right of Hungarians to participate in democratic elections, which relies on political parties having equality of opportunity to compete for voters’ support. State capture of institutions responsible for administering the elections, ensuring a level electoral playing field, and protecting people’s data has led to selective enforcement of laws that further benefit the ruling party. However, the parties and international observers have paid insufficient attention to how emerging campaigning tactics impact human rights, including the right to privacy.

Privacy is a human right recognized under international and regional human rights treaties. Comprehensive data protection laws are essential for protecting the right to privacy as well as the related freedoms that depend on our ability to make choices about how and with whom we share information about ourselves. International and regional standards also recognize the human right to participate in democratic elections. A level electoral playing field is a necessary condition for the enjoyment of this right. In line with this principle, public resources should not be used to tilt the electoral playing field in one party’s favor.

The report finds that data collected by the state for administering public services, such as registering for the Covid vaccine, administering tax benefits, and mandatory membership in professional associations, was repurposed to spread Fidesz’s campaign messages. Evidence indicates that the government of Hungary has collaborated with the ruling party in the way it has used personal data in political campaigns. This, combined with the severe weakening of the political institutions responsible for safeguarding people’s right to privacy and guaranteeing an even political playing field, raises serious human rights concerns.

This report also investigates how Hungary’s opposition parties used data in their campaigns. Unlike the ruling party, the opposition parties did not have access to broad swaths of voters’ data. Rather they relied on traditional data collection methods (such as in-person and online petitions and signature gathering) as well as the services of private digital campaigning companies and tools provided by social media platforms, in particular Facebook. The opposition parties processing of personal data lacked sufficient transparency and risked undermining privacy but unlike the ruling party there is no evidence that its handling of data created unfairness in the election process.

Data-driven technologies are increasingly becoming the norm in modern political campaigning across many countries and will likely grow as the availability of digital technologies and personal data on voters becomes more prevalent. International election observers, international and Hungarian nongovernmental organizations, and independent journalists have published reports which have raised concerns about Fidesz’s significant influence on local media, lack of independence of judicial institutions, and blurring of resources between state and party resources.

This report seeks to contribute to a growing body of research that situates the use—and misuse—of data in specific political contexts and to surface key human rights concerns around data-driven technologies and political campaigns. It does not assess the efficacy or desirability of the use of data-driven technologies in political campaigns. Nor does it imply that the use—or misuse—of data-driven campaigning was a decisive factor in the outcome of Hungary’s 2022 elections.

Social media platforms also played an important, albeit complex role, in the 2022 elections. On the one hand, online political ads created new opportunities for opposition campaigns to reach voters in an environment from which they are largely shut out of traditional advertising spaces. On the other hand, since domestic laws regulating campaign spending limits are not being applied to online ads, the availability of Facebook advertising in particular has tremendously benefitted Fidesz, which with its outsized resources outspent the opposition.

Platforms, including Facebook—the most widely used platform for online political ads in Hungary—provided a degree of transparency into campaign spending, by offering limited insight into spending on political ads with their ad libraries. However, many of the ways in which platforms allow political parties, including those in Hungary, to target political advertising are inherently opaque. As a result, it is impossible for independent watchdog organizations or regulators to reach a clear conclusion when investigating whether or not the targeting of online political ads was discriminatory in targeting or excluded someone by relying directly or indirectly on sensitive data. The data sharing and profiling involved in advertising targeting generally introduces heightened privacy concerns in an electoral context, and can be used to unduly influence individuals when it comes to political discourse and democratic electoral processes.

Under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, private companies have a responsibility to respect the right to privacy and to mitigate and remedy rights abuses, including those that contribute to the undermining of privacy and the right to participate in democratic elections.

The Hungarian government should end the use for electoral campaigns of personal data collected by the government while performing public functions and providing public services, and should guarantee a level playing field around elections. It should rectify the current shortcomings in laws, policies, and practices, including by ensuring the independence of institutions responsible for administering elections and protecting people’s data.

For too long, the European Union (EU) has responded in a muted manner to Hungary’s backtracking on the rule of law, refusing to acknowledge or speak out against the systematic erosion of democratic institutions and human rights. The EU should urgently assess whether the exploitation of personal data collected by the Hungarian government for political campaigning is consistent with EU laws. In particular, it should ensure that EU funds granted to support the digitization of public services in Hungary do not result in or contribute to violations of the EU General Data Protection Regulation and other EU law. The European Commission should bring infringement proceedings against Hungary for any violations of EU law.

Political parties in Hungary should be more transparent concerning how they collect and process voters’ data and demonstrate that they are taking their responsibility to respect people’s privacy seriously.

Social media platforms, which have become the de facto infrastructure of the global public square, should urgently take steps to release adequate information to voters in Hungary and elsewhere on why they are seeing an online political advertisement and which individual, or institution is responsible for placing it, both in advertising libraries and in real time. They should also ensure that ad targeting and delivery are not, indirectly or directly, based on observed or inferred special categories of data, including political opinions.

Failure to take adequate steps to ensure that personal data is not misused by political campaigns risks further eroding human rights, the rule of law, and democracy in Hungary.

While this report focuses on Hungary's unique political landscape around the 2022 election campaigns, the heightened dependence on data in electoral campaigns, and the increased digitization of public services raise serious human rights concerns, such as those documented in this report, in many countries.

Recommendations

To the Government of Hungary

- To guarantee a level playing field around elections, end the use for electoral campaigns of personal data collected by the government while performing public functions or providing public services. This requires respecting purpose limitation, the legal principle that personal data should be collected for a determined, specific, and legitimate purpose.

- Ensure that the legal and institutional frameworks, including Act XXXVI of 2013 on Election Procedure and the administrative and judicial bodies that oversee it, unambiguously prohibit the misuse of administrative resources, including personal data collected from citizens, in order to guarantee a level playing field in election campaigns.

- Ensure that any personal data collected by government agencies and institutions complies with data protection regulations, including purpose limitation, and delete any personal data collected without sufficient purpose limitation, including data that risks being repurposed for political campaigning.

- Broaden the competence of the National Election Commission to empower it to establish whether breaches of the Act CXII of 2011 on the Right to Informational Self-Determination and Freedom of Information lead to violations of fundamental election principles.

- Adequately resource and ensure full independence of the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (NAIH) to enable it to enforce applicable law, including the EU General Data Protection Regulation and Act CXII of 2011 on the Right to Informational Self-Determination and Freedom of Information, as they apply to political parties and candidates without prejudice.

- Adopt legislation that guarantees that the inclusion of personal data in party supporter databases is based on explicit, specific, fully informed, and freely given consent. In the case of online data collection, the data controller should ensure that a confirmation e-mail is sent to the data subject including information on the legal remedies available in relation to data processing and on further steps that the data subject can take to exercise their data rights (such as data erasure).

- Require the NAIH to have stricter and mandatory oversight over the collection, management, and use of voter data by political parties and candidates for political offices—regardless of their political ideology.

- Ensure that all domestic legislation that applies to political marketing is GDPR-compliant, in particular that people must opt in to have their data used for political marketing, not opt-out.

- Ratify the protocol amending and updating Council of Europe Convention 108 for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data and implement the Council of Europe’s Guidelines on the Protection of Individuals with regard to the Processing of Personal Data by and for Political Campaigns.

- Ensure that an enabling framework is provided for political parties and candidates for political offices—regardless of their political ideology—to enjoy an even playing field, particularly in relation to their ability to access funding and other resources, and to exercise the rights to freedom of expression, including through equitable access to the media. Greater transparency into campaign income and spending, as well as increased independence of the National Election Commission and State Audit Office, are key in this regard.

- Ensure that campaign spending on online political advertisements is factored into campaign finance spending limits. Act XXXVI of 2013 on Election Procedure should be amended to ensure that all advertising activities that aim to influence voter behavior or public policy opinion formation around the elections are included as political advertising, including online political ads. Political parties should be required to report on their spending on online political ads. Furthermore, the SAO should be required to take into account publicly available information from ad libraries published by platforms when auditing campaign expenditures.

- Ensure that public resources are not used to campaign for the ruling party by amending the Act XXXVI of 2013 on Election Procedure to prohibit campaigning activities arising from functions of state entities.

- State institutions, such as the judiciary, election administration bodies, and the data protection authority should be genuinely independent, impartial, and should not be used to further the electoral cause of the ruling party.

- Reform the State Audit Office to ensure its independence and strengthen its ability to audit political parties and candidate spending on campaigns, including online political ads.

- There should be a prohibition on the appointment of a president or vice president of the SAO who is a representative or leader of a political party.

- The SAO should be empowered to uncover and sanction questionable spending by political parties, who tend to underreport expenditure.

- The SAO should keep a public record of the results of the investigation of the reports received.

- During the campaign period, SAO should record an online database campaign spending by parties, including online political ads, containing the sender of the ad, the price of an ad, the amount paid for the ad, its period, link to the ad, and any identifying number. The owner of each platform displaying advertisements should also provide the SAO with similar data for the advertisements published on their platforms.

To European Union Institutions and Member States

- The EU Commission should initiate infringement proceedings against Hungary for the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (NAIH) failing to meet the qualifications of an independent supervisory authority as required by Chapter VI of the General Data Protection Regulation.

- The EU Commission should assess whether EU funds used to support the digitization of public services in Hungary resulted in the violation of EU law, including Articles 5, 6, 7, and 9 of the General Data Protection Regulation.

- EU member states should immediately move Article 7 proceedings on Hungary forward, including by adopting specific rule-of-law recommendations and vote to determine that there is a clear risk of a serious breach of the values protected by the EU treaty.

- Adopt a regulation on the transparency and targeting of political advertising that:

- Applies to both ad targeting (how an advertiser determines who they would like to reach) and ad delivery (how the publisher of an ad determines who within the potential audience will actually see the ad).

- Mandates meaningful transparency through ad archives, as well as for live ads that enables audiences, regulators, individuals, and public interest groups to understand the ad targeting and delivery techniques used.

- Bans the targeting and delivery of political ads based on the processing of observed data and inferred data, and places restrictions around special categories of data and non-relevant provided personal data.

- The Commission should elaborate guidance addressed to national data protection authorities and governments to clarify how the GDPR should be applied to political advertising in consultations with experts and affected stakeholders, such as voting rights organizations.

To Hungarian Political Parties

- Ensure that the processing of any personal data of voters is compliant with the data protection principles of proportionality, lawfulness, fairness, transparency, purpose limitation, data minimization, accuracy, and security including under EU GDPR standards. Processing should be proportionate in relation to the legitimate purposes of political campaigns, reflecting the rights and freedoms at stake. The collection of personal data on the opinions and preferences of voters should be proportionate to those defined purposes and should not lead to a disproportionate interference with the voter’s interests, rights and freedoms.

- Only process data for clearly stated, legitimate purposes of political campaigning, such as: canvassing political opinions; communicating about policies, events and opportunities for engagement; fundraising; conducting surveys and petitions; communication on political goals and policies via social; media, email and text; engaging in “get-out-the-vote” operations on election day.

- Enable voters to exercise their data rights, including by obtaining on request and without excessive delay or expense, confirmation of the processing of personal data relating to him or her, and access to those data in an intelligible form, including any “score” assigned to them regarding their ideological orientation, as well as the ability to object to the processing of data, to request rectification or erasure, including for political advertising purposes, and to remedy violations of their rights.

- Carry out data protection audits and impact assessments concerning its processing of data for campaigning purposes and communicate findings. Data protection and privacy impact assessments should not only assess the specific impact on an individual voter’s rights but should also consider whether the processing is in the best interests of broader democratic values and the integrity of democratic elections.

- When acting as a coalition, ensure that voters’ data protection rights are respected and that voters are notified and informed about how a coalition group will be using their collected data.

To the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (NAIH)

- Periodically and on the basis of a publicly accessible audit plan published in advance, investigate the data management practices of all political parties, without prejudice, regarding the personal data of their supporters. The findings of the investigation should be concluded and made public before the next elections.

To Local and International Election Observers, including from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

- Integrate privacy and data protection into election observation methodology and operationalize this monitoring in the election observation process.

To Meta

- Provide users with meaningful transparency on why they are seeing ads on Facebook and Instagram, and which individual or institution is responsible for placing it, so that they can sufficiently understand the ad targeting and delivery techniques used.

- Provide users with adequate information on how they can avoid being targeted with political ads on Facebook and Instagram.

- Provide users with information on any targeting or delivery criteria used in the dissemination of the political ads shown to them.

- Ensure that ad targeting and delivering are not, indirectly or directly, based on observed or inferred special categories of data, including political opinions.

To Digital Campaigning Companies

- Ensure that any services provided to political parties or campaigns are compliant with the data protection principles of proportionality, lawfulness, fairness, transparency, purpose limitation, data minimization, accuracy, and security, recognizing the heightened privacy concerns in an electoral context.

Methodology

Based on research conducted between November 2021 and August 2022, this report documents how data-driven political campaigning in Hungary’s April 3, 2022, elections contributed to an already uneven playing field, with the ruling party enjoying undue advantage, and undermining the right to privacy and other rights. This report relies on a combination of desk research, interviews with experts and with people whose data was misused, and technical analysis.

In researching the report, Human Rights Watch analyzed court decisions and decisions from the data protection authority, reports by human rights organizations and legal aid service providers, election observation missions, academic articles, and media reports. Desk research informed the report’s understanding of the use of data in previous Hungarian elections, Hungary’s legal, political, and electoral framework, and the broader state of human rights and the rule of law in Hungary.

Between September 2021 and June 2022, Human Rights Watch interviewed 35 people, both inside and outside of Hungary, including experts on the rule of law, privacy and data protection, election integrity, and media freedom, as well as journalists, political consultants, and representatives of political parties and companies involved in data-driven campaigning in the April 2022 elections. Human Rights Watch interviewed 9 people whose data was misused in by political campaigns: 5 in person, and 4 over the phone.

All interviewees freely consented to the interviews, and Human Rights Watch explained to them the purpose of the interview and did not offer any remuneration. Human Rights Watch also explained to them that they could stop the interview at any time and decline to answer any question. All interviews were conducted in English or Hungarian with interpretation into English and covered a range of topics related to unsolicited and/or unwanted communications from political campaigns. The interpreter was identified by a Hungarian speaking staff member and interviewees were identified the others with the help of a Hungarian civil rights organization. The average length of each interview was approximately one hour.

The names of most people reporting misuse of their data interviewed for this report have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect their privacy and to protect against reprisal. These pseudonyms are indicated clearly as such with quotation marks on the first use. When real names of interviewees are used, Human Rights Watch obtained informed consent after discussing the potential risks.

The interviews with affected voters are presented as case studies, giving insight into the experiences of Hungarian voters and contributing evidence of the abuses documented. Interviews with experts informed the report’s understanding of the use of data in previous Hungarian elections, Hungary’s legal, political, and electoral framework, and the broader state of human rights and the rule of law in Hungary.

In April 2022 Human Rights Watch wrote to all major political parties and campaigns to request interviews. Human Rights Watch interviewed 5 political parties in May 2022 in person. All interviews were conducted in English or Hungarian with interpretation into English and covered a range of topics related to the party or campaign’s approach to data-driven campaigning, the importance of data-driven campaigning and online political ads in Hungarian elections, efforts taken to protect personal data collected and processed on voters. The average length of each interview was approximately one hour.

Right of Reply

Human Rights Watch sent follow-up letters to all major political parties in August and September 2022 to request additional information and to provide them with the right to reply. Three parties and campaigns responded, and 6 have not at time of writing. Human Rights Watch also wrote to companies implicated in the report between August and October 2022, and to relevant government institutions, including the National Election Commission (NEC), the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (NAIH), and the State Audit Office (SAO) in October 2022. Their responses are incorporated into the report.

In November 2022, Human Rights Watch shared the main findings of this report with the Office of the Prime Minister of Hungary. We sought answers to specific questions, including concerning the government’s use of personal data in political campaigning and measures it has taken to ensure an equal electoral playing field and the full independence of relevant institutions. The officials have not responded to our letters at time of writing.

Technical Analysis of Websites

To understand how political parties and campaigns’ websites handle their users’ data, including potentially for campaign purposes, Human Rights Watch used Blacklight, a real-time website privacy inspector built by Surya Mattu, former senior data engineer and investigative data journalist at The Markup, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates how powerful institutions are using technology to change society.[1] The methodology Human Rights Watch used to conduct technical analysis of political parties and campaigns’ websites is described in detail in Section IV, “Website tracking by political parties.”Selection of Political Parties and Campaigns

The report focuses on the use of data-driven political campaigning by the main political forces contending in the 2022 elections. It includes the ruling coalition (made up of Fidesz and the Christian Democratic People's Party) and the six parties and political movement that comprised the joint opposition (United for Hungary)[2], and excludes smaller parties.

Selection of Data-Driven Campaigning Techniques

This report focuses on the data-driven campaign techniques that were most prevalent in political campaigns in Hungary’s 2022 elections. These include:

- Building and management of databases on voters, including the collection of personal data on voters and their political preferences

- Direct outreach to voters through email, SMS, and robocalls

- Online political advertising through social media platforms, in particular, Facebook

Human Rights Watch is aware of data protection abuses associated with so-called “business” or “fake” parties. In Hungary, candidates need to collect at least 500 supportive signatures in order to run a candidate for election,[3] and therefore, benefit from state subsidy for their campaigns.[4] These “business” or “fake” parties are alleged to have stolen personal data from various sources and copied them to the supportive sheets. Since these are not directly related to the main political blocs, they fall outside of the scope of this report.

Limitations

This report covers the use of databases and technical systems to which Human Rights Watch did not have direct access. As a result, the research relied on the following: examining and verifying campaign messages (primarily through interviews and reviewing screenshots); interviewing and writing to political parties and campaigns; relying on reports from whistleblowers and investigative journalists; reviewing analysis of publicly available data on online political ads placed on Facebook, conducting technical analysis of the websites of political parties and campaigns; and reviewing privacy policies of political parties and campaigns.

This methodology comes with certain limitations. Since Human Rights Watch did not have access to the underlying voter databases on which parties relied for their campaigns, the report is not able to independently verify what personal data on voters they contain. Because the research’s findings in part rely on responses from political parties and campaigns, it contains more information and insight into those that were more forthcoming. Since members of the United for Hungary coalition were more responsive to Human Rights Watch’s inquiries than Fidesz-KDNP, the report contains more detailed findings on some aspects of their campaigns.

Additionally, affected voters who came forward hesitated in sharing their personal experiences because they felt that what happened to them was happening at a widespread level and experienced a sense of resignation. Therefore, the interviews function as case studies or testimonies and do not aim to be representative or scale of abuses experienced.

Finally, Blacklight’s analysis is limited by the fact that the simulation may trigger different responses from the website under examination because it is a simulation of user behavior, not actual user behavior. Additionally, Blacklight’s analysis may include false negatives, it does not determine intent of collection, or how the data were used, and its results are only indicative of the test that was run at that point in time, under your simulated conditions. So, the results can vary for different people, or even for the same user across time. A detailed discussion of these technical limitations can be found in Blacklight’s methodology available online.[5]

I. Background

Hungary held national elections on April 3, 2022, which resulted in a decisive victory by the ruling party Fidesz (the Hungarian Civic Alliance), and a fourth term for prime minister Viktor Orbán, but there were serious concerns about the fairness of the elections.[6] An election monitoring mission from the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE),[7] on April 4, 2022 noted a number of concerns in the lead-up to elections. They included blurring the lines between the government and the ruling party in campaigning, amplifying the advantage of the ruling coalition; the absence of a level playing field, and lack of balance in campaign coverage in the press, on television, and on billboards.[8]

The country’s main opposition parties put aside their differences to run as a united front against Fidesz and its coalition partner, the Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP). Changes to the electoral law in 2020 in effect forced opposition parties to join in running a single national list against Fidesz in order to meet the new minimum requirements.[9]

For the first time, Hungarian opposition parties decided to organize a “pre-election” to select a prime ministerial candidate and to select common candidates for single-member districts around which they could form a unified coalition in the parliamentary elections. The first round of the pre-election was held from September 12 to 27, 2021, and the second round from October 10 to 16, 2021.

The opposition coalition made up of the Democratic Coalition (Demokratikus Koalíció or DK), Jobbik (Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom), Momentum (Mozgalom Momentum), Hungarian Socialist Party (Magyar Szocialista Párt or MSZP), the Green Party (Magyarország Zöld Pártja or LMP), and Dialogue for Hungary (Párbeszéd Magyarországért), collectively became known as Egységben Magyarországért, or United for Hungary. The opposition candidate for prime minister, Péter Márki-Zay, came from a seventh entity, Mindenki Magyarországa Mozgalom (Everybody for Hungary Movement, or MMM), which joined efforts with United for Hungary.

Data as a Political Asset

Digital technologies have transformed key components of electoral and democratic processes, including campaigning by political parties. Personal data can be understood as a political asset. Political parties are creating their own datasets for two primary reasons: as political intelligence – to help inform campaign strategies and test and adapt campaign messaging – and as political influence.[10]

Data-driven campaigning consists of not just online political ads, but different ways in which personal data is used in efforts to understand, engage, and influence citizens in political campaigns.[11] For example, political campaigns build and maintain voter databases of personal data to help them gain insight into their base and potential new supporters, to learn what motivates voters, and to tailor messages to what they want to hear. They collect personal data on potential voters through canvassing, in-person and online petitions, polls, and events in order to expand their databases to stay in touch with supporters and mobilize them to vote on election day. Data-driven campaigning can facilitate new ways to reach potential supporters, such as through bulk SMS, email, phone calls, and social media. Political parties also make use of private platforms, like Facebook and Instagram, and data brokers to help them profile and target new supporters with political advertising.

Data Protection and Political Campaigning in Hungary

Privacy is a human right, as recognized by international and regional human rights treaties to which Hungary is party.[12] Privacy is also protected by Hungarian law.[13]

Comprehensive data protection laws are essential for protecting human rights – most obviously, the right to privacy, but also many related freedoms, such as freedom of opinion, expression, association, and assembly, that depend on people’s ability to make choices about how and with whom they share information about themselves.[14] Hungary is bound by the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),[15] one of the strongest and most comprehensive attempts globally to regulate the collection and use of personal data by both governments and the private sector.[16] The processing of personal data in Hungary is regulated by Act CXII of 2011 on the Right to Informational Self-Determination and Freedom of Information, as amended by Act XXXVIII of 2018 to implement the GDPR. [17]

Hungary is also party to the Council of Europe’s Convention 108, for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data[18] and a signatory to the 2018 protocol updating the Convention,[19] which is commonly referred to as Convention 108+. The Consultative Committee of Convention 108+ developed Guidelines on the Protection of Individuals with regard to the Processing of Personal Data by and for Political Campaigns to provide practical advice to supervisory authorities, regulators and political organizations about how the processing of personal data for political campaigning should comply with Convention 108+.[20] They offer a framework through which individual data protection authorities, and other regulators, may provide more precise guidance tailored to the unique political, institutional and cultural conditions of their own democratic states.

Hungary does not have specific legislation regulating the use of personal data in electoral campaigns or by political parties. However, data protection law applies and has always applied, to the personal data processed by the organizations involved in political campaigning – including the political parties, their candidates, and the various data brokers, voter analytical companies, platforms, advertising and other companies that might process personal data on their behalf.[21] The GDPR and Hungary’s Act on the Right to Informational Self-Determination and Freedom of Information govern the protection of personal data, including tighter regulation of special categories of sensitive data, including information revealing someone’s racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, or trade union membership.[22]

Additional non-data protection-specific laws are relevant to the use of data by political campaigns. For example, Section 149 of the Act XXXVI of 2013 on Election Procedure provides that the use of voter data, such as phone number and email address, to deliver election campaign materials directly to the voter requires explicit consent.[23] Under Section 89 of the same act, voters can request that their personal information in the voter registry (name and address) not be disclosed to political parties for campaign purposes.[24]

The E-Commerce Act[25] and the act on Electronic Communications (E-Comms) Act[26] are relevant to political marketing. The E-Commerce Act regulates the use of email addresses and SMSs, and the E-Comms act regulates phone calls (whether automated or not, using either randomly generated numbers or not). Receiving SMSs, emails and automated phone calls requires prior consent (opt-in), including by political campaigns, according to the E-Commerce and E-Comms acts, respectively. Receiving "live" phone calls, however, works under an opt-out regime, where users are by default listed in a "phone book" (either physical or digital), unless they request not to be listed or labeled as a person who would not like to receive advertisement despite their number being public.

Misuse of Data in Previous Hungarian Elections

In previous elections, the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU), one of the country’s leading human rights NGOs, documented data protection violations, abuses, and irregularities with respect to the use of personal data by Fidesz in its electoral campaigns.[27] For example, in the 2019 European Parliament and municipal elections, the HCLU observed data protection violations it attributed to the construction and mobilization activities of the parties' databases, as well as to a specific public opinion

research company.

In 2020, a client of the HCLU won a lawsuit against Fidesz for the illegal handling of his data during the 2019 municipal elections.[28] The client claimed that he never gave his contact details to the party, yet Fidesz sent him campaign materials via email. Fidesz could not prove that it had obtained the data legally.

According to the HCLU, the Regional Court of Appeal’s verdict proved that Fidesz processed personal data illegally for the purpose of political marketing. Assuming this was not an individual case, the HCLU initiated a request for a comprehensive investigation of Fidesz's data management for political marketing purposes at the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (NAIH). According to the information provided by the NAIH, the investigation of Fidesz's data management was already underway based on the request of other notifiers, who objected to the lawfulness of the data processing of the Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Alliance.[29]

Case Study: Fidesz’s Voter DatabaseFidesz, according to experts Human Rights Watch interviewed, has been known to maintain a database on voters for several years, with some independent media dating its existence back to 2004.[30] The database is commonly known as the “Kubatov list,” named after Fidesz’s party director Gábor Kubatov. Fidesz does not deny the existence of the database, but refers to it as a register of sympathizers and claims it is legal.[31] Efforts by the NAIH to investigate it have sidestepped the crucial question of whether the collection of storing data on voters’ preferences over time is illegal. In December 2012, a whistleblower named Gergely Tomanovics (who went by the pseudonym Gery Greyhound) made public[32] a 2009 video[33] produced by Fidesz, which explained how the Kubatov list system works at the campaign level. Tomanovics reportedly worked for Fidesz for years, making campaign videos. A 2018 Facebook video uploaded by Csaba Bartók,[34] the president of Fidesz in Szeged, a major Hungarian city in the south of the country, captures an online version of the Kubatov list, which includes the names, phone numbers and other information on Fidesz supporters. Journalists from 444.hu were able to capture the URL[35] and access the login screen (accessible through the WebArchive in August 2018[36] and November 2018[37]). But the site was either migrated to another domain or taken offline following the news report. The database reportedly includes detailed information on voters that goes beyond what is included in the country’s national voter registry, which includes basic voter information, like the name, date, address, and personal identifier of the voter.[38] According to experts interviewed by Human Rights Watch, while the content of the database has not been made public, its purpose is to collect information about the political views of the population in general and to determine whether each citizen supports Fidesz or not.[39] Party activists reportedly visit people’s homes, going door-to-door, and assign voters loyalty scores to Fidesz to help the party predict their behavior on election day, including whether they are likely to vote for the ruling party. [40] Below is a translation of the scores assigned to voters as reported by multiple Hungarian news outlets.[41] · T (support), · E (rejects), · B (uncertain), · N (not at home), · R (wrong address), · G (other), · M (disabled), · H (deceased), · K (moved). According to experts interviewed by Human Rights Watch and independent media, the database enables Fidesz to have detailed insights into the electorate[42] and when elections come, Fidesz sends each constituency the part of the database they can work with specific target numbers of voters to mobilize.[43] A key question concerning the Kubatov list is whether it contains data collected by Fidesz on their sympathizers with consent, or on the electorate more broadly, including those who did not consent.[44] According to the HCLU, the existence of a database that collects information on voter preferences without their knowledge or consent may undermine principles of fairness of the election and equal opportunities for candidates and nominating organizations required by the Act on the Election Procedure.[45] In addition to collecting information on voters’ political views through door-to-door canvassing, Fidesz also reportedly collects information on voters through “national consultations” and petitions. According to the Hungarian Helsinki Commission, a “national consultation” is a method introduced by Fidesz, by which the government sends out questionnaires with multiple-choice answers to citizens.[46] It is not equal to a referendum or a popular initiative, there is no participation requirement attached to it, and its result is not binding for the government. These are often conducted ahead of elections[47] and are viewed by experts as a way to collect information on voters to refresh and update the Kubatov list ahead of the polls.[48] Officially, the national consultations are conducted by the prime minister’s office, but as in many other areas, the line between state and party resources and activity is blurry. Tamas Bodoky, editor-in-chief of the investigative journalism outlet Átlátszó, told Human Rights Watch, “Fidesz is mixing state resources and state functions with party resources and party functions, so I would not be very surprised if they used the national consultation or other state databases to amend the party database.”[49] Previous national consultations have raised data protection concerns. In June 2011, the former Data Protection Commissioner issued a statement concluding that the protection of personal data was not ensured in the course of the data management related to the national consultation launched in May 2011 and, therefore, the questionnaires shall be destroyed after the responses have been recorded.[50] In this national consultation questionnaires were sent out with individual bar codes, which were unique and could be linked back to the recipient, both for those who did and did not respond.[51] Once the NAIH took over the position of the Data Protection Commissioner in 2012, the NAIH announced that it did not agree with the original decision of the Data Protection Commissioner and would issue a new decision. Finally, in July 2012, the questionnaires were destroyed. However, the former Data Protection Commissioner claimed that, according to his decision, the electronic database containing the personal data of those citizens who provided a response should have also been destroyed, but this did not happen.[52] Human Rights Watch could not independently verify whether national consultations fed into the database, but the allegation was stated consistently in multiple interviews with experts. In 2020, following a complaint by an independent member of parliament Ákos Hadházy, the NAIH launched an investigation into the Kubatov list.[53] The NAIH finished its investigation in December 2020. The NAIH found that Fidesz did not provide the data subjects with information that fully complies with the requirements of the GDPR during data management in connection with the periodic register related to the assessment of the intention to participate in the elections and directed Fidesz to make some adjustments in its data handling.[54] For example, the NAIH recommended that Fidesz increase the font size of the privacy notice on its signature collection forms to improve legibility, establish a procedure to objectively verify the deletion of all personal data contained in the periodic register of electoral intentions, and establish appropriate internal procedures and internal rules to ensure and facilitate the exercise of data subjects' rights.[55] However, according to Adam Remport, Legal Officer for the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union’s Privacy Project, “the [data protection authority] circumvented the main issue of collecting data on data subjects' political allegiances (at least on whether they are supportive of the governing party or not); the DPA only instructed Fidesz to give proper notification before collecting such data, but did not investigate the systematic mapping of voters’ political affiliation.”[56] Miklos Ligeti, Head of Legal Affairs for Transparency International- Hungary told Human Rights Watch that profiling voters based on their political preferences without obtaining valid consent is unlawful. Basic information on voters in order to get out the vote should be deleted after the elections, not retained for years.[57] |

Media reported that the opposition also engaged in data-driven campaigning around the 2019 elections. In particular its use of the digital campaigning company Datadat came under scrutiny. Datadat was founded by former government members ex-Prime Minister Gordon Bajnai, former Minister for Intelligence Ádám Ficsor, campaign strategist Viktor Szigetvári, and sociologist Tibor Dessewffy. Szigetvari, managing director of Datadat, told Human Rights Watch that the company “imagines itself as a progressive value aligned digital software as a service and consultancy company…[that does] data management [and] database building. We are experts of e-mail programs in a sense of how to design your e-mail plan until the day of election or in peacetime between actions. How to design your messenger game. How to [carry out] a fundraising program. How to enhance your database and reach your datasets and variables.”[58] Szigetvári stressed that they work in a GDPR-compliant way. The company has worked with multiple parties in Hungary on the opposition side, as well as municipal candidates. It has also worked in Romania, Italy, and other countries, according to Szigetvári.

According to the independent news outlet Átlátszó, which published an investigative piece on Datadat in 2020, the company ran a Facebook ad campaign that contributed to the electoral successes for the united opposition in the 2019 municipal elections.[59] The elections, in which the opposition had limited resources in the face of overwhelming political, financial, and media superiority by Fidesz, resulted in surprise wins for opposition groups in Budapest and several other large cities. Átlátszó reported that Datadat was responsible for targeting the Facebook ads of EzaLényeg, a newly established news site, whose reporting included carefully crafted and targeted messages aiming to resonate with various electoral groups. Átlátszó also reported that several DK candidates listed Datadat as their data processor.

The online news portal 24.hu reported that Datadat’s chatbot[60] allows campaigns that use it to record responses from users, enabling them to see what voters think about certain issues, how important these issues are to them, using more subtle methods than traditional political fault lines. In this way, political messages can be targeted very precisely and parties can also build a community with it.[61] Datadat declined to comment on 24.hu's report when Human Rights Watch reached out to them.

Rule of Law and Human Rights in Hungary

Fidesz’s victory can in part be attributed to an uneven playing field enabled by the hollowing out of democratic institutions since Orbán returned to power in 2010.[62] Successive Orbán governments undermined the independence of the judiciary, hijacked public institutions, concentrated the media landscape and subjected it to government control,[63] criminalized activities by civil society organizations,[64] harassed independent journalists,[65] and demonized vulnerable groups and minorities, in particular migrants, refugees, and LGBT people.[66] The Fidesz-KDNP majority has also tinkered with the electoral laws to serve its own interests, which allows them to rule with a majority in parliament, and thereby continue gutting Hungary’s democracy.[67] Government influence over key institutions has contributed to an uneven playing field, which gives the ruling party overwhelming superiority in its ability to campaign and impunity for its violations and abuses of national law and international human rights standards.

In 2018, the European Parliament voted to trigger the article 7 process to hold Hungary accountable for actions that threaten the rule of law, human rights, and democratic principles. Since the procedure was opened, EU member states have regularly scrutinized and debated the rule of law situation in the country but have fallen short of taking additional steps under the procedure. In September 2022, the European Parliament adopted a follow-up text to update its areas of concerns and press the EU Council to act, stating that there is growing consensus that “Hungary is no longer a democracy.”[68] On September 18, 2022, the European Commission recommended suspending around 7.5 billion euros in funding to Hungary under its Rule of Law Conditionality mechanism, citing corruption and breaches of EU rule of law standards.[69] EU member states are expected to vote on this proposal by December 2022.

Since 2020, Orbán’s government has declared two “states of danger” a special legal order granting overwhelming power to the executive to rule by decree. The first was in March 2020 in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic and extended in December 2020 and June 2021.[70] Under the special legal order, government may suspend application of acts of parliament, derogate from provisions of acts, and take other extraordinary measures. Since March 2020, the government issued over 250 decrees, most, but not all of them, related to the pandemic. On May 25, Hungary’s ruling party pushed through parliament a constitutional amendment allowing the government to declare a “state of danger” in the event of armed conflict or humanitarian disaster in a neighboring country.[71] Immediately, Prime Minister Orbán declared a second state of danger, citing the war in Ukraine. The state of danger gives Orbán sweeping powers to rule by decree, sidestep parliamentary debate, and suspend laws at short notice with very limited to no judicial oversight.

National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (NAIH)

The National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (NAIH) is the public authority responsible for monitoring and enforcing the rights to the protection of personal data and freedom of information. The NAIH’s head is chosen by the prime minister and appointed by the president. The president has a purely ceremonial role and can only deny nominees under very narrow conditions.[72]

When faced with complaints that implicate government abuse of personal data, the NAIH has demonstrated that it is not always willing or able to act as an independent authority. For example, its credibility was marred by its investigation into the use of Pegasus spyware by the Hungarian authorities targeting journalists, lawyers, politicians and other public figures.[73] The NAIH concluded on January 31, 2022, that there was no “information indicating that the persons requesting and conducting the surveillance had violated any laws or regulations, ... as the spy software can be used on the grounds of national security risk”.[74] The NAIH then went on to investigate one of the investigative journalists, Szabolcs Panyi, who broke the story and was himself confirmed to be targeted with Pegasus because of his reporting on Pegasus following a complaint by an intelligence officer who was likely the spyware's operator.[75] After four months, the NAIH determined that the investigation against Panyi was unfounded, and the proceedings against him were terminated.

“The data protection authority [NAIH] is normally strict on data protection, but in politically sensitive cases the NAIH President does not challenge the interests of the government parties. However, it has spoken up in smaller cases against opposition parties. At the same time, in his capacity as the institution responsible for the enforcement of the right to freedom of information, he has made statements that are critical of the government,” Sandor Lederer, co-founder and director of K-Monitor, a non-profit public funds watchdog based in Budapest, told Human Rights Watch.[76]

With regard to election-related data protection abuses, the NAIH has conducted itself in a selective manner, subjecting opposition parties to close scrutiny. For example, in a positive step, in February 2021 the NAIH issued extensive guidance on data protection requirements concerning the processing of personal data by political parties and organizations. [77] However, its enforcement has mainly focused on opposition parties and when it came to credible allegations of Fidesz’s maintaining a database of voters’ personal data containing their political views, the NAIH failed to adequately investigate. (See Case Study: Fidesz’s voter database)

On May 4, 2020, the government published a decree limiting the exercise of certain rights and measures under the GDPR “in order to prevent, identify and detect coronavirus cases, as well as prevent its spread, including the organization of the coordinated performance of tasks by the public bodies in relation to this”.[78] The Data Protection Decree (179/2020 V.4) suspended some articles of the GDPR on the processing of personal data “in order to prevent, identify and detect coronavirus cases, as well as prevent its spread, including the organization of the coordinated performance of tasks by the public bodies in relation to this.” [79] This replaced the strict notification requirements, by which public bodies are obliged to notify individuals when collecting their personal data, with general information simply published electronically on purpose and scope of processing.

The suspension of aspects of GDPR drew criticism from the Chair of the European Data Protection Board,[80] and was characterized by civil society as disproportionate, unjustified, and potentially harmful to the public’s response to fight the virus.[81] An independent legal opinion found that the Data Protection Decree is inconsistent with the GDPR, and thus contrary to EU law, and likely to give rise to breaches of the Charter.[82] The Data Protection Decree was no longer in force as of June 18, 2020, when the first “state of danger” was terminated, and the GDPR-related suspensions contained in 179/2020 V.4 were not reintroduced when the subsequent “state of danger” was declared in November 2020.[83] The International Commission of Jurists described these measures as “contrary to the [GDPR] and arguably fall short of the legitimate purpose and necessity requirements for emergency measures to comply with international law”.[84]

In response to Human Rights Watch’s questions about the NAIH’s independence, the NAIH President expressed his confidence that the NAIH’s activities fully comply with the independence requirements of international and EU law, as well as the Hungarian Constitution, and noted that there has been no finding from a forum relevant in this regard refuting this. It also cited a 2012 Venice Commission report without addressing that report’s conclusion that the mode of designation of the President of the NAIH “which entirely excludes the Parliament, does not offer sufficient guarantees of independence.”[85]

Media Environment

Hungary’s media landscape is now largely controlled directly or indirectly by Orbán and his government.[86] Since coming into power in 2010, Orbán’s government has amended media laws to ensure that it controlled appointments to the main media regulatory body and introduced vague content restrictions with the possibility of high fines, all of which has had a chilling effect on press freedom.[87] Between 2011 and 2016, in five waves of dismissals, the state broadcaster, closely linked to the government, fired over 1,600 employees, including journalists who were not willing to toe the government line.[88]

The editors-in-chief of Origo and Index, two major independent media outlets at the time, were fired, in 2014 and 2020, respectively. The two publications have since adopted a pro-government editorial line.[89] In 2016, Hungary’s biggest opposition daily, Nepszabadsag, was shut down.[90] The closure followed publication of a series of articles that exposed incriminating details of alleged public sector corruption involving some of Orbán’s closest colleagues.

The 2018 merger of more than 400 media outlets into one nonprofit conglomerate loyal to the government, sidestepping competition laws, ended media pluralism in the country.[91] According to data from the Mérték Institute, an independent Hungarian media monitoring project, from 2019, 79 percent of the media was concentrated in pro-Fidesz hands.[92]

In the context of elections, the government’s domination of the media means that Fidesz overwhelmingly enjoys superiority in favorable coverage. The opposition has little opportunity to get its message out. The OSCE election observation mission found:

“The pervasive bias in the news and current-affairs programs of the majority of broadcasters […] combined with extensive government advertising campaigns provided the ruling party with an undue advantage. This deprived voter of the possibility to receive accurate and impartial information about the main contestants, thus limiting their opportunity to make an informed choice”. [93]

The OSCE election observation mission’s final report added that coverage on some public and government-affiliated private media displayed a clear bias in favor of the government and Fidesz, and “[a]s a rule…lacked any clear distinction between coverage of the government and the ruling party”.[94]

Judiciary

Over its 12 years in power, the Orbán government introduced a series of legal and constitutional changes that have limited the independence of the judiciary and interfered with the administration of the courts.[95] For example, it has packed the Constitutional Court with its preferred justices, forced 400 judges into retirement, and imposed limitations on the Constitutional Court’s ability to review laws and complaints.[96] According to Amnesty International Hungary, between 2010 and 2020, the government took several steps that amount to a systemic attack against the independence of Hungary’s judicial institutions.[97] The National Judicial Office (NJO) responsible for the administration of the courts and overseeing judicial appointments, continues to undermine the independence of the judiciary. The European Commission and the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe have said the head of the NJO, a political appointee, holds too much power and is subject to too few checks and balances.[98] There is also concern about nepotism, as relatively unqualified friends and family of well-connected politicians are appointed to senior posts in the court system. A recent investigation by the Hungarian Helsinki Committee found that the President of the Kúria, Hungary’s supreme court, accelerated the executive’s take-over of the judiciary.[99]

According to Áron Demeter, program director at Amnesty International Hungary, “If you go against the government or your case interferes with political goals, there is definitely a chance that [the government] can put either formal or informal pressure on the court.”[100]

National Election Commission

Authorities charged with overseeing the administration and integrity of the elections, such as the National Election Commission (NEC), are dominated by appointees of the ruling majority.[101] According to the OSCE’s election report, half of the filed complaints and appeals were denied consideration by the NEC on technical grounds, and some dismissals on merit lacked necessary examination or sound reasoning. While some election disputes were adequately resolved, the handling of most cases by the adjudicating bodies fell short of providing effective legal remedy, contrary to OSCE commitments. The NEC also issued fines against CSOs that had encouraged voters through social media and online websites to invalidate their ballots on the anti-LGBT rights referendum.[102] All of the complaints against government-linked bodies or the ruling party were among those the NEC rejected.[103] Almost all of the cases in which the NEC found violations had unknown violators but were linked to the opposition.

In a letter to Human Rights Watch, the President of the NEC said that the OSCE’s report lacked specifics concerning questions about its independence and clarified the process for electing and delegating its members. The NEC President also defended the NEC’s dismissal of the requests for legal remedies in all cases as being in compliance with the legal requirements and pointed out that it was also possible to appeal to the Court of Appeals with a review request against the decisions of the NEC, which the parties involved made use of in many cases.[104]

State Audit Office

The State Audit Office (SAO) is mandated to oversee the accountability of the use of public funds and audit political parties.[105] It has the power to verify the information submitted to it but has been unwilling to fully exercise its investigative capacity to ascertain actual campaign spending.[106] Campaign finance regulations are vague and do not require parties to report in enough detail to provide meaningful insight into their finances.[107] The regulations do not define what content the reports parties and campaigns are required to submit must include, so they sometimes only include a few lines saying how much money was spent.[108]

The OSCE characterizes the SAO as falling short of international standards related to the oversight of campaign finance. Its report also notes that the SAO has a track record of identifying irregularities primarily in the finances of opposition parties and that between 2010 and July 2022, the SAO was headed by a former MP and deputy leader of the Fidesz parliamentary faction, who resigned from his political positions after his appointment to the SAO. [109] These concerns were compounded by the absence of legal processes to contest the SAO’s findings and conclusions.[110] In a letter to Human Rights Watch, the President of the SAO wrote that the SAO "has fully complied and will continue to comply with its statutory audit obligations regarding the audit of election campaign expenditures” and that in carrying out its audits it “acts in accordance with the law, the audit programme, the professional rules and methods of auditing and ethical standards”.[111]

Hungarian civil society organizations have documented how the SAO has for decades been underusing its powers and has proven incapable to uncover and sanction questionable spending by political parties, who tend to underreport expenditure.[112] They have also documented a pattern of the SAO imposing excessive fines on opposition parties, which is seen by many as the misuse of powers.[113]

In a letter to Human Rights Watch, the SAO clarified that while “political advertising on social media is a campaign tool not specified in the Act on Election Procedure … its use during the campaign period is considered campaign activity” because it is capable of influencing or attempting to influence the will of voters. As such, “candidates and nominating parties participating in parliamentary elections have an even higher responsibility to account for political advertising on social media, therefore the provisions relevant to campaign spending activity of the Act on Election Procedure also apply to content published on social media during the campaign period”, according to the SAO.[114] However, effectively, campaign spending on online political ads does not factor into official accounting for campaign expenditures unless parties proactively report it to the SAO.

II. Fidesz and Government Misuse/Abuse of Personal Data in the 2022 Elections

As in previous years, the Kubatov list was reportedly used in the 2022 elections. The investigative journalism non-profit Direkt36 reported in March 2022 that possessing an up-to-date database with their own voters remained a central element of Fidesz’s election strategy for the 2022 national elections. A government official told Direkt36, “There is a huge belief in the management of Fidesz that in the end, that is all that matters. On the day of the elections, you have to stand there in the door until you convince citizens to go to vote.” The source added that Fidesz put a lot of energy into updating the list and this year Fidesz activists will follow on tablets which doors there are still to knock on and just like food couriers they would “always just receive the next name and address.”[115]

In 2018, the independent news outlet 444.hu also reported that some Fidesz party supporters canvassed with iPads distributed by the party, which served the dual purpose of providing an up-to-the-minute update of the Kubatov list and making it possible to check whether the canvasser actually visited the address assigned to them on the list.[116] Human Rights Watch was not able to independently confirm what software or application Fidesz may be supporting the Kubatov list, but the fact that iPads and tablets may have been given some form of access to the list, or parts of the list, raises question about data security.

In its December 1, 2022, response to Human Rights Watch, the Hungarian government denied it has misused personal data for political purposes leading up to the 2022 elections, in particular claiming people agreed to be contacted by the government when they signed up for a newsletter on the vaccine registration website and that the government did not violate regulations on sending unsolicited SMS/Automated calls.

Unwanted Calls and Messaging

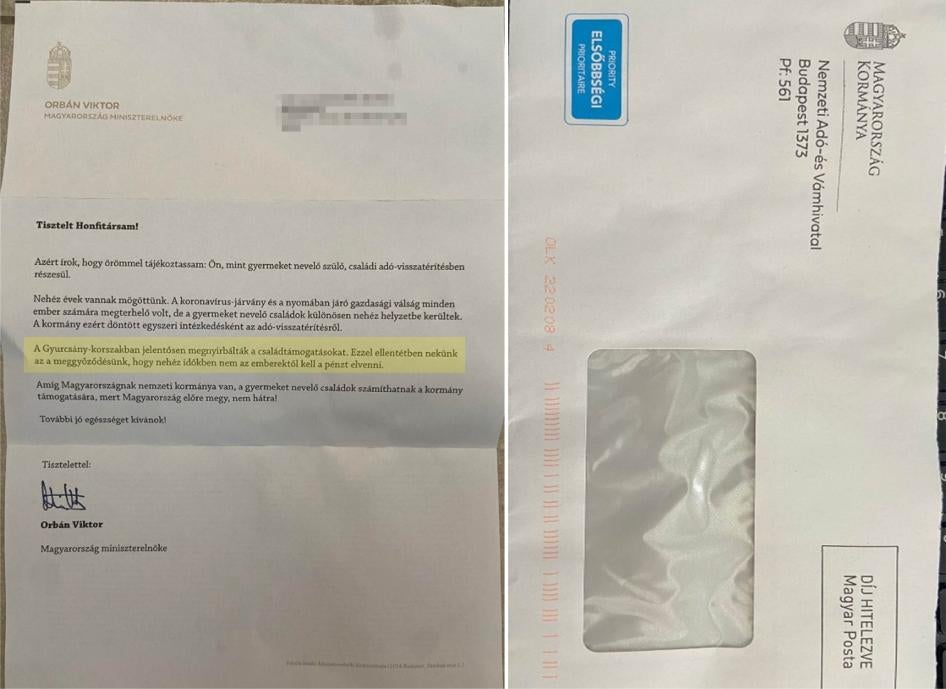

Voters told Human Rights Watch they were bombarded with political campaign messages through email, SMS, robocalls, and online political ads, in addition to traditional forms of campaigning. Some were outraged by the unsolicited campaign messages and propaganda from the ruling party that they received as a result of signing up for public services, like registering for a Covid vaccination, applying for tax benefits, or joining a professional association.

The HCLU reported that several people turned to them for legal help during the 2022 election period.[117] The HCLU said as of August 2022, the organization received between 40 and 50 election-related data protection complaints for the 2022 election cycle. As in previous years, complaints included unsolicited phone calls from political campaigns encouraging them to vote. The NEC received at least 18 complaints alleging campaign calls and SMSs to citizens by political parties.[118] The NAIH told Human Rights Watch that it received several notifications (without specifying the number) from people who complained about receiving unwanted SMS messages in support of Fidesz, and that it launched an official investigation, which is ongoing at time of writing. The NAIH also said it received two complaints objecting to unwanted campaign calls from the ruling party, one of which is under investigation at time of writing.[119]

Human Rights Watch was not able to determine how widespread this phenomenon was. Of the nine people who shared their experiences with Human Rights Watch concerning misuse of their data, four said they received unwanted phone calls and text messages from Fidesz encouraging them to vote for the party on election day, without recalling that they have provided their phone numbers for campaigning purposes. The fact that it was documented in previous years suggests these are not isolated incidents.

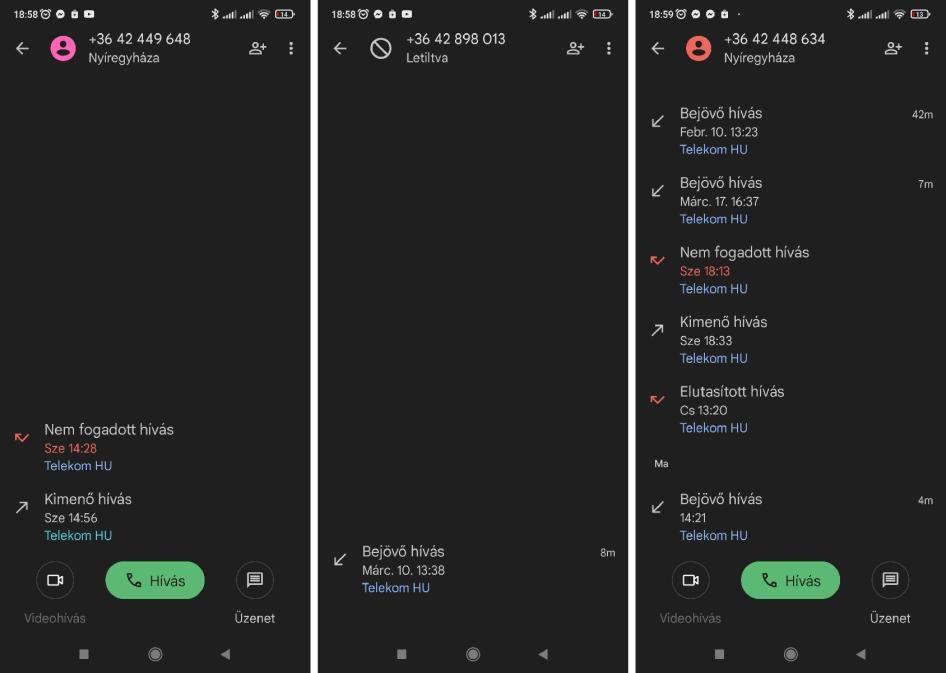

Case Study: Unwanted Calls from FideszAlex B., a 27-year-old male voter from Szeged, told Human Rights Watch that he received multiple phone calls on his mobile phone from three different phone numbers with a recorded message from a Fidesz candidate encouraging him to support the candidate by going out and voting on election day and also to remember the achievements of Fidesz.[120] He checked the numbers displayed on his mobile phone when he received the calls, and put them through the telecom registry, which showed that all three were registered to Fidesz. Alex B. also received three text messages on election day from Fidesz urging him to vote for Fidesz, asserting that the opposition candidate would drive the country to war, and that only Fidesz can preserve the peace and security of the country. Alex B. told Human Rights Watch that he did not consent to his number being used by Fidesz for campaigning purposes. He filed two complaints about the misuse of his data, one to the address for the Fidesz office in Nyíregyháza, a city in northeast Hungary and the county capital of Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg, with which the phone numbers were associated, according to the telecom registry,[121] and the other to the central office of Fidesz in Budapest. The complaint sent to the Nyíregyháza office was returned through the postal service due to an incorrect address and the second received a response from Fidesz that the party is not processing his data in any way.[122] “Being contacted by a party, that I’m not member of or follower, when I didn’t give my phone number to them…It kind of pissed me off,” said Alex B. ‘Csaba’, a 48-year-old male voter from Pest county, a county in central Hungary that surrounds Budapest, received an automated phone call from Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in the week before the elections encouraging him to support Fidesz.[123] “There was so much communication in the last five to six days before the elections,” said ‘Csaba’, ‘Csaba’ told Human Rights Watch that he had given his number to the Chamber of Agriculture to register his business and speculated that this may be the reason why he was the Prime Minister’s campaign was able to call him. ‘Ágnes Kovács’, 35, a Hungarian voter who lives abroad, told Human Rights Watch that she received a phone call on her Hungarian phone number on April 1, two days before the election, urging her to vote for Fidesz.[124] “I picked up the phone, and heard a deep, deep voice on the other end say ‘Hello, good afternoon.’ I responded, ‘Who are you looking for?’ In the meantime, the voice responded, ‘I'm Viktor Orbán.” ‘Ágnes Kovács’ told Human Rights Watch that she " definitely didn't provide [her] phone number to the party or campaign in any way." She noted that she has limited interactions with the Hungarian government because she lives abroad. The only instance in which she recalls providing her phone number was when registering for the Covid-19 vaccine. |

Covid Vaccination Registration System Turned Campaign Machine

Human Rights Watch documented new forms of misuse of personal data collected by the government and used for political campaigning by Fidesz in the 2022 elections. Numerous Hungarians and foreigners living in Hungary received campaign propaganda as a result of their signing up to register for the Covid-19 vaccine (with their email and phone number, as well as other personal data). The NEC reportedly received three cases alleging that government campaign emails to citizens breached data protection rules.[125] That the government sent out the messages was not in question. Rather, the debate focused on whether these messages violated electoral or privacy laws.[126]

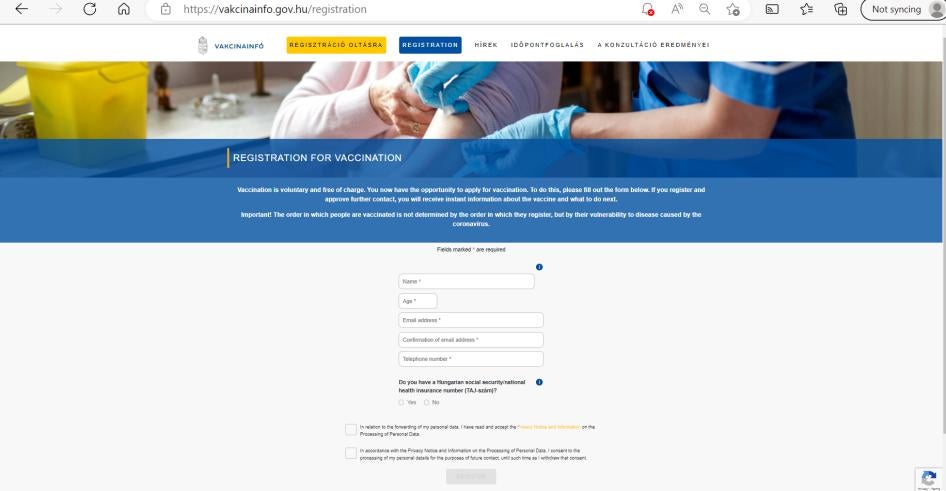

On December 7, 2020, the Hungarian government launched a website for Hungarian citizens and residents to register for the Covid-19 vaccine.[127] When signing up on the site, people were directed to accept the privacy policy[128] and were given the option to opt-in and consent to the processing of contact details for future contact purposes, until they withdrew their consent. In the first year, the vast majority of the emails that the Coronavirus Information Centre, which is managed by the Government Information Center managed by the Office of the Prime Minister, sent out to its distribution list were related to the vaccination registration effort. Human Rights Watch reviewed 16 emails sent to the distribution list in 2021. Fourteen emails provided information on Covid vaccination, one email provided information about an upcoming national consultation on life after the pandemic, which covered a range of topics, and one email contained political messaging on matters unrelated to Covid.

Starting January 2022, the emails began shifting from vaccine related information toward political messaging, including relating to the upcoming elections. For example, on January 8, 2022, the Government Information Center sent out an email informing recipients “In 2022, several changes will come into effect. Below we summarize the most important ones,” which listed the government’s programs that will benefit citizens, completely unrelated to the Covid response.[129] For example, the email communicated that from January 1, the minimum wage will rise to 200,000 forints (approximately 455 USD) and the minimum wage for skilled workers to 260,000 forints (approximately 590 USD). It also announced new tax cuts, reducing the tax paid by employers from 17 to 13 percent. Additionally, extra financial support for elderly and young citizens was announced, in the form of changes to pensions and income taxes, and for families with children, through income tax returns and subsidies.

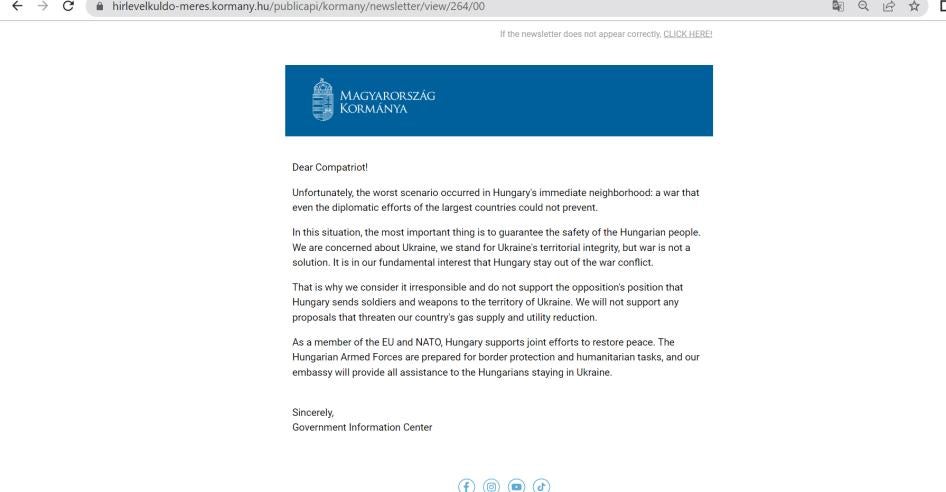

Following the January 8 email through June 2022, only one further email that Human Rights Watch reviewed was related to Covid vaccinations. The list of people who signed up for communications related to Covid vaccinations were now being fed with government information, with some messages intended to influence the upcoming elections by espousing positions aligned with Fidesz’s campaign. For example, a March 28 email solicited support for the anti-LGBT referendum, which was held the same day as the parliamentary elections on April 3. The email concluded, “We can stop sexual propaganda aimed at children now! So we ask you to take part in the referendum and vote 4 nays! Protect our children!”[130] Another email, dated February 24, sought to discredit the opposition by misrepresenting its position on the war in Ukraine, specifically stating “we consider it irresponsible and do not support the opposition position that Hungary should send soldiers and weapons into Ukraine. We will also not support proposals that jeopardize our country's gas supply and the reduction of gas prices.”[131]

By using personal data submitted to the government for the purpose of being informed about Covid vaccines to disseminate political and electoral messaging, the government misused citizens’ personal data.

Several people Human Rights Watch interviewed reported feeling like they were taken advantage of by the government in a particularly vulnerable and fearful moment. Some reported that they were typically hesitant to share their personal information with the government but did so in order to register for the Covid vaccine because they felt they had no choice.

Borbála F., a 44-year-old voter from Budapest, told Human Rights Watch, “If you don't register for this form, it was unclear if you could get the vaccine. At this time, people were afraid of COVID, and wanted the vaccine as soon as possible.” She added, “I don't want to give my personal info in any case when it's not absolutely important. We were put in a position where we felt our lives were in danger [from the pandemic/Covid], and had to give our information [in order to get the vaccine]. I don't want that to happen again. If I give my personal info it should only be used for that purpose.”[132]

Maria G., a 67-year-old voter from Budapest, signed up in early 2021 when the registration site was first opened: “I definitely wanted to be vaccinated and I remember that at first.”[133] She explained, in the first wave of promoting the vaccine, they said that “only those who register will be vaccinated.” Later on, it became more relaxed, “but at the beginning they made registration a condition of receiving vaccination.” Maria G., also said she is generally suspicious of signing up for things with the government, but “fear [of the virus] overcame my suspicion,” she said.

‘Zsofia’, a 36-year-old Hungarian woman from the Budapest metropolitan area, told Human Rights Watch that in the context of the fear and uncertainty caused by Covid-19, when she saw the question about further contact with the government, she had “this feeling that you cannot do otherwise, I have to be vaccinated… This was not a free choice and that’s why I was so angry.”[134]

‘Dave,’ a 48-year-old American living in Budapest, told Human Rights Watch, “I’m a private person, but I’m not reluctant to hand over my data when it’s for something important. It’s not a deal breaker for me and getting the vaccine was important to me… I think people were eager to get vaccinated. I wanted to know how and when to get the vaccine, and I was happy to give my contact information to get that information.”[135]

Other State and Civic Institutions Co-opted by Fidesz