Summary

If you haven’t had children, employers regard you as an “extra-large time bomb” that will explode twice [take maternity leave twice]. If you’ve had one child, you’re a “time bomb” likely to have a second child at any time. If you already have two children, you must be too busy taking care of the children so [you] can’t focus on work.

— A popular saying on the Chinese internet describing the impossible position working women face under China’s two-child policy

In May 2017, doctors told Liu Yiran, a 34-year-old woman working for an internet company in Beijing, that she was pregnant. Liu immediately informed her employer of the pregnancy. Soon thereafter, the company posted a job ad for a new position that had the same responsibilities as hers, never informing Liu. In July, a new employee assumed Liu’s position and the company stopped paying Liu’s salary.

Liu then took the company to a labor arbitration board in Beijing, seeking past unpaid wages and overtime pay from the company. In March 2018, the labor arbitration board mostly denied Liu’s request, saying she had not proven her case and citing such things as her failure to properly document salary and regular work attendance prior to her termination, information that the company refused to provide her.

Because Liu had spoken out about her experience on Chinese social media platforms, her former employer then sued her for defamation. In a July 2017 article on the Chinese news website The Paper, Liu said, “[I] just wanted an explanation, an apology, and just, fair treatment,” but found “the difficulty in defending [my] rights has been beyond my imagination.”

Liu Yiran’s story is just one of many stories of women in China who face egregious pregnancy-related discrimination in the workplace. This report—based on a review of Chinese websites and social media, Chinese and international media reports, and a review of court verdicts—details the nature of workplace discrimination that took place immediately after the two-child policy went into effect in 2016, and the discrimination that Chinese women continue to face today.

China’s Population and Family Planning Law states that, “citizens have the right to reproduction, as well as the duty to carry out family planning according to the law.” For 35 years, from 1979 until 2015, for most couples in China, “the duty” was to only have one child. The one-child policy, however, brought about a rapidly aging population and a dwindling labor force. In December 2015, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress revised the law to allow couples to have two children, effective January 1, 2016.

After the two-child policy went into effect, a majority of women surveyed by various Chinese companies and women’s groups reported they had been subjected to gender and pregnancy-based discrimination in pursuit of employment. Countless job ads specify a preference or requirement for men, or for women who have already had children. Numerous women have described, on social media, to the Chinese media, or in court documents, their experiences being asked about their childbearing status during job interviews, being forced to sign contracts pledging not to get pregnant, and being demoted or fired for being pregnant.

|

“She didn’t inform us in advance at all. Got pregnant ahead of the schedule. This is not being trustworthy,” a representative of a company said to the newspaper Beijing Youth in April 2017, explaining why the company fined an employee for being pregnant. |

|

“The company’s illegal behavior incurred serious mental harm to me, resulting in me having a miscarriage on September 20, 2018,” Sun Shihan said in a court filing. Sun sued her former employer after the company suspended her upon learning she was pregnant. |

|

“After you get married, you don’t have the final say about whether you have a child or not… If you get pregnant, you will take maternity leave, then I will certainly hire others, and you will be replaced,” a human resources staff member at a company told an interviewee during a job interview in September 2020, explaining to her why the company required applicants to pledge not to get pregnant if hired. |

On the surface, the government appears committed to women’s rights and equal employment: “women’s emancipation” is a key objective of official Chinese Communist ideology and officials continue to develop policies to counter workplace discrimination. In February 2019, nine Chinese central government agencies jointly issued a notice outlining specific measures for implementing laws that prohibit gender discrimination in employment. In January 2021, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the government’s main labor administration agency, committed to amending and improving anti-gender discrimination laws and strengthening enforcement. However, authorities have so far failed to consistently enforce existing anti-gender discrimination laws and regulations.

While authorities claim they are combatting gender discrimination in employment, they have disseminated extensive propaganda across China encouraging women—but not men—to reject work outside the home and instead raise children.

China’s constitution guarantees equal rights between men and women. While laws ban gender and pregnancy-based discrimination in employment, they provide few specific enforcement mechanisms, leaving victims with inadequate avenues for redress. Some women, after suffering discriminatory treatment, have filed complaints with local labor arbitration boards or courts, but, like Liu Yiran, have too often ended up empty handed. Sometimes their claims do not succeed because legal standards are unclear, or they face bureaucratic or evidentiary requirements that prove insurmountable. Even when women win their cases, compensation awarded to victims is too often too small to justify going through the legal system and penalties imposed on companies too insignificant to serve as a deterrent for future violators.

The Chinese government has now doubled the number of children it allows most people to have, but it has failed to address the still disproportionate and discriminatory impact of its child policies on women in the workplace.

More than 25 years after hosting the landmark 1995 United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, the Chinese government should abolish the two-child policy, end all restrictions of reproductive choices, enforce and strengthen anti-discrimination laws, and promote equitable caregiver leave polices. Chinese authorities should also lead on gender equality by speaking out promptly and decisively on public controversies that reveal attitudes in broader society that perpetuate China’s deep gender inequality.

Methodology

The Chinese government is hostile to research by international human rights organizations, closely monitors and strictly limits the activities of domestic civil society groups, and censors the internet and the media. In recent years, the authorities have significantly increased surveillance and suppression of discussions and activism on many issues, including women’s rights, a topic that had been relatively tolerated before. These limitations affected the design and conduct of this research.

In assessing conditions facing women in the workplace in China today, we focused on the period between January 2016, when China’s two-child policy went into effect, and January 2021. We have drawn on studies by Chinese companies and nongovernmental organizations, Chinese social media posts, reports by domestic and international media, and other publicly available information. We interviewed Chinese women’s rights activists who have done extensive work to combat gender discrimination in the workplace in China. We also examined court documents from the government-run court verdicts database “China Judgments Online,” searching the terms “pregnancy” and “labor contract,” and filtering for cases involving employment.

We have not been able to access the original methodology sections of many studies cited in the report and are therefore unable to analyze their disparate research methods and the quality, reliability, or limitations of each study. However, given the minimal amount of open quantitative data and the inability to conduct primary surveys in China, we are cautiously citing these statistics as material that helps corroborate the qualitative research that Human Rights Watch has conducted.

I. Background

Human Rights Abuses Related to the One-Child Policy

In 1979, to curb population growth and ease environmental and natural resource challenges, the Chinese government introduced the “one-child policy,” limiting most couples who were Han—China’s predominant ethnic majority—to just one child. Exceptions were later given to families in the countryside whose first child was a girl, households in which both parents were themselves only children, and other limited situations.[1] In 1982, the National People’s Congress adopted a new constitution that, for the first-time, enshrined birth control as every citizen’s duty. Starting in 2014, couples could have two children if either of the parents were themselves only children. For China’s ethnic minorities, most couples have been allowed to have two children. Some were allowed more.[2]

To enforce the one-child policy, the authorities subjected countless women to forced contraception, forced sterilization, and forced abortion, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. A vivid illustration is the “Childless Hundred Days” campaign launched by authorities in Guan and Shen counties in Shandong province in 1991. In 100 days from May to August that year, all pregnancies in the two counties were forcibly aborted, regardless of whether the birth would have been in compliance with the one-child policy.[3]

Parents across the country who resisted complying with the one-child policy were harassed, detained, and had their properties confiscated or houses demolished.[4] Authorities often levied enormous fines on families who violated the policy, forcing them into destitution. Children who were born outside of the one-child policy were denied legal documentation. As a result, until the hefty fine was paid, these children were unable to access education, health care, or other forms of public services.[5] Couples who were employed by the government or government-affiliated institutions were often fired from their jobs if they had unauthorized children.[6] Women who suffered from complications relating to forced contraception, sterilization, or abortions were never properly treated or compensated.

The one-child policy decreased China’s birth rate, and by the early 2010s, after it had been in effect for more than 30 years, it had contributed to a rapidly aging population and a dwindling labor force. Coupled with China’s traditional preference for boys, the one-child policy also created a huge gender imbalance. Researchers estimate that China now has 30 to 40 million “missing women.” This gender imbalance has made it difficult for many Chinese men to find wives and has fueled a demand for trafficked women and girls from abroad, as Human Rights Watch has documented.[7]

The Two-Child Policy and the Gender Gap

To bring relief to an aging population, the Chinese government, starting in 2016, allowed all couples to have two children, putting an end to the one-child policy. In some situations, couples are now allowed to have more than two children, such as if the first or second child has a disability. Each province makes its own rules on eligibility to have additional children and on specific punishments, including the size of fines, for violating the law.[8]

It is not clear that the policy is achieving its objectives. Five years after the universal “two-child policy” was promulgated, statistics show that it is failing to reverse the falling birth rate, despite an initial spike. The number of newborns in 2016 was 18 million, a jump of over 1 million from the previous year. Births dropped each year afterwards, to 12 million in 2019 and 10 million in 2020, the lowest since 1961. Projections show the two-child policy will help alleviate population aging, but not enough to reverse the trend. By 2050, 366 million, or about 26 percent of the country’s population, will be 65 or older.[9]

Around the time the two-child policy was announced, studies by the government and private companies showed that many women did not want to have a second child. In a 2016 survey by the All-China Women’s Federation, the government-controlled women’s organization, 53 percent of families who already had a child said they did not want a second child, and 26 percent said they were not sure whether they wanted a second child. Only 21 percent said they would like to have a second child. Families from more economically developed areas showed less desire for a second child. The study also showed that access to education, health care, and childcare, as well as economic status, are the main factors in families’ decisions whether to have a second child.[10]

Similarly, in a 2016 survey of professional women by one of China’s largest recruitment sites, Zhilian Zhaopin, 59 percent of those who already had one child said they did not intend to have a second child. Among those who had not had a child, 21 percent said they did not want any children. Nearly 42 percent of those who did not want any children or a second child cited “hindering work, professional development” as a reason.[11] Local surveys reflected similar views: a survey by the women’s federation in Jinyinshan, a town in Hunan province, showed that 76 percent of local women said they did not want a second child. Among them, 85 percent cited the negative impact on career as a reason.[12]

Despite the strong interest among women in work, shown by such surveys, China’s gender gap has increased since the universal two-child policy took effect, continuing a trend that started years earlier. While China’s labor force still has a relatively high number compared to that of many other countries, the percentage of woman has decreased from 45 percent in 1990 to under 44 percent in 2019. [13]

China’s ranking in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap index in 2020 fell for the 12th consecutive year, leaving China in 107th place out of the 156 countries surveyed. It has been a dramatic fall: in 2008, China had ranked 57th. Large gender gaps exist also in terms of senior roles, where only 11 percent of board members and 17 percent of senior managers in China are women.[14]

Comparable data is not available on whether gender discrimination in employment has also worsened in recent years and contributed to the gender parity gap. A 2019 study by the Women’s Federation in Yunnan province showed that 40 percent of women faced discrimination when looking for employment.[15]

Human Rights Watch’s analysis of the Chinese government’s national civil service job lists showed continuing employment discrimination. In the 2020 job list, 11 percent of the postings specify a preference or requirement for men. In both the 2018 and 2019 job lists, 19 percent of the postings specified a preference or requirement for men. In 2017, the rate was 13 percent.[16]

Propaganda Encouraging Women to Stay at Home and Have Children

Extensive state propaganda across China has encouraged woman—but not men—to stay at home and raise children. A February 2016 article by the state news agency Xinhua said women being at home was “not only beneficial to the growth of children, the stability of the family,” but also had a “positive effect on the society.” The government-controlled China Youth Daily said, in 2017, that women were “more suitable to stay at home and look after children.” In August 2020, as part of President Xi Jinping’s campaign against food waste, the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF) called for women—but not men—to “exercise the important role in family life” and “be diligent and frugal in managing the household.”

Family planning propaganda slogans have also turned to promoting having a second child. A billboard in Liaoning province read, “what abortion takes away is not just a child… what is aborted is the bloodline of the male partner’s ancestors.”[17] The slogan “one child poor, two children rich, the Party leads the way to comprehensive moderate prosperity” appeared in various places in China.[18] A board displayed in Shangjiaping village in Shanxi province encouraged different generations to have a second child: “Mother and daughter being pregnant at the same time is not shameful. Mother-in-law and daughter-in-law having second children at the same time is something to be proud of.” During the Covid-19 lockdown in Luoyang, Henan province, health authorities put up a banner saying, “Stay at home during the outbreak, two-child policy has started, creating a second child can also contribute to the country.”[19] In Yichang, Hubei province, a 2016 document called for Communist Party members to take the lead in having a second child.[20]

Policies Incentivizing Having a Second Child

Authorities still think that women alone are responsible for childcare, and government policies and laws on caregiver leave reflect that view. This has encouraged discriminatory behavior by employers.

Nationwide, female employees are entitled to at least 98 days of paid maternity leave; there is no national legislation on paternity leave. After the two-child policy went into effect, 30 of China’s 31 provincial-level governments lengthened mandated maternity leave. In provinces such as Hunan and Hainan, women are now entitled to 188 days of maternity leave with pay.[21] Provincial and municipal paternity leave can vary from 7 to 30 days.[22]

Other incentives for additional children do not distinguish between mothers and fathers. Besides expanding maternity leave benefits, local authorities have also rolled out subsidies for baby food, housing, and education, as well as tax cuts and cash rewards.[23]

Human Rights Watch research has not found evidence of overtly abusive policies to punish couples for not having a second child, but there have been controversial proposals. A 2018 article in the government-controlled Xinhua Daily, for example, suggested a national “childbirth fund,” into which all citizens younger than 40, regardless of gender, would be required to deposit a certain percentage of their earnings every year. Families could withdraw from the fund when they had a second or third child.[24] An expert in a government-affiliated reproductive center in Shanxi province proposed to provincial legislators, in 2021, that the government create a “good matchmaking environment and encourage women aged between 21 and 29 to give birth during this optimal reproductive period.”[25] These proposals, coming after 30 years of coercive state birth policies, raise concerns that that authorities are considering requiring women to have more children.

Censorship and Repression of Women’s Rights Activism

Efforts by women’s rights activists and ordinary citizens to combat gender discrimination are seriously hampered by the Chinese government’s tight restrictions on freedom of expression and the internet, and its stepped-up harassment, censorship, and punishment of those who speak out for rights.

In recent years, prominent women’s rights activists have faced police harassment, intimidation, and forced eviction for their peaceful advocacy.[26] In March 2015, around International Women’s Day, the Chinese government detained five women’s rights activists for a month after they planned to distribute stickers with anti-sexual harassment messages on public buses.[27]

At the same time, authorities have intensified media and internet censorship of women’s rights activism.[28] In March 2018, social media platforms Weibo and WeChat permanently suspended the accounts of Feminist Voices, a social media publication run by outspoken feminists. During the #MeToo movement in 2018 and 2019, censors removed numerous social media posts supporting victims of sexual harassment. Not surprisingly, the activists’ public campaigns are much less influential than they were several years ago, when the media was freer to report on their activities and online discussions of them and their work were not overtly controlled.

II. Pregnancy-Based Discrimination in Employment

“[When the interviewers realized I already had two children], they appeared delighted that ‘I had completed the task’ and wouldn’t take prolonged time off. But they also said that there were two blank years on my resume, so they regarded me as an entry-level employee.”

— Woman job-hunting after taking two years off to care for her children, Hubei province, September 2020[29]

Many women in China have posted messages on social media or told Chinese journalists they have experienced pregnancy-based employment discrimination since the two-child policy took effect. A 2019 study by the recruitment site Zhilian Zhaopin showed that 57 percent of the professional women it surveyed believed “being at the life stage of marriage and childbearing” is a reason for being bypassed for promotion. The study also showed that 41 percent of the women surveyed said they “want to have a second child but do not dare.” Among them, 59 percent listed a second child “could hinder career development” as a reason.[30] A 2020 study by Zhilian Zhaopin reported that 64 percent of women listed childbearing/childrearing as a reason for gender inequality in the workplace, while only 39 percent of men cited it.[31]

The 2017 annual report by the Zhicheng Legal Aid Center for Migrant Workers in Beijing showed that the number of cases the organization handled involving pregnancy-related dismissals of migrant women significantly increased after the two-child policy took effect.[32]

A major driver of pregnancy-based discrimination appears to be that companies do not want the inconvenience created by the months-long absence of an employee and costs associated with hiring a replacement. The cost of maternity leave is also a major driver. If an employer has paid parental insurance for an employee, the social security fund will cover their parental leave. But if the employer has not paid parental insurance for the employee, it must pay the employee as if she or he were working during parental leave. Because mothers have much longer mandatory parental leave than fathers (and in some regions, fathers have none at all), it is much more costly to pay for parental leave for women than for men.[33]

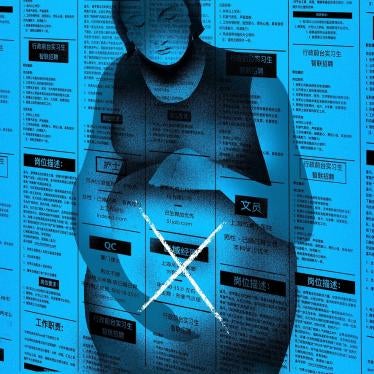

Discriminatory Job Ads

There are numerous job advertisements that specifically exclude women who appear more likely to take maternity leave. Human Rights Watch found many ads on major job search websites in China that require female applicants to “have [already] given birth” (已育, 已生育).

An ad posted in August 2020 on Indeed.com for a nurse in a hospital in Jiangsu province stated, “women, married with children, at least two years of experience.” Another ad posted in September 2020 for quality control managers at an auto parts manufacturer in Fujian province stated, “no restriction on male or female (females must be unmarried, or married with children, [schedule] won’t interfere with night shifts), age between 18-35.” An ad posted in September 2020 on 51job.com for an editor position at an online education company in Beijing said applicants who “already have children are preferred.” Another September ad on the site for a manager position in a clothing company in Beijing said, “age between around 30 and 35, already have children, good looking and good disposition.” Human Rights Watch wrote to Indeed.com and 51job.com to confirm and comment on the accounts mentioned above (see Appendix). At time of writing, Human Rights Watch received no response.

Similarly, company websites, social media platforms, and chat groups publish discriminatory ads. In a September 2020 ad for a clerk on the website of Shanghai Pudong Hospital, the hospital required applicants to be “men” or “married women with child(ren).” In a June 2020 ad for an accountant, Ma’anshan Daily, a government-owned newspaper in Anhui province, required applicants to be between 30 and 45 years old, and, if the applicant was a woman, “be married with child(ren).” A 2019 ad for a finance position at a subsidiary of the insurance conglomerate Ping An Insurance stated, “no restriction on men or women, [but applicants] married without child(ren) will be rejected.” While the exclusion did not say it applied only to women, it almost certainly would be interpreted that way given the cultural context. Human Rights Watch wrote to Shanghai Pudong Hospital, Ma’anshan Daily, and Ping An Insurance to confirm and comment on the accounts mentioned above (see Appendix). At time of writing, Human Rights Watch received no response.

To be more competitive in the job market, some female job seekers voluntarily provide information about their family status. In a looking-for-work ad on the social media website Weibo, a female user stated, “24-year-old, six years of working experience… married with child(ren).” Attached to the ad is a photo of a baby, presumably her child.

Discrimination During Job Interviews

According to a 2014 study by the All-China Women’s Federation of college graduates in three provinces, 59 percent of surveyed women reported that during job interviews they were asked whether they were the only child of their parents or whether they planned to have two children (a woman who is an only child typically faces particular pressure to have more than one child).[34] A 2020 Zhilian Zhaopin study reported that 58 percent of surveyed women—compared with nearly 20 percent of surveyed men—said they had been asked about whether they had, or intended to have, children during the recruitment process.[35]

Numerous women have gone public with their experience of being asked pregnancy-related questions during job interviews. In July 2019, China Youth Daily reported that Zhang Chun, a woman who had just graduated with a master’s degree in journalism, was told not to get pregnant for a five-year period as a condition of her employment at the publicity department in a public hospital. “We could hire you, but this job requires you to carry equipment, taking photos. You can’t go and have a child [for the next] five years,” the interviewer at the hospital told her. Zhang also said the job ad had required applicants to be male, but no men had applied.[36]

“In 2018, when I changed jobs. I was interviewed by five organizations. Every time, I was asked these questions [referring to marriage and childbearing status]. Three of them said they would not offer me the job if I wanted to have a child,” Yu Yu, 30, told China Youth Daily. Yu had not married or had a child at the time.[37]

A woman who graduated from college in 2019 said, in a September 2020 post on the social media website Douban, that a company interviewer told her the position required her not to get married for at least two to three years. A human resources staff member at the company said to her, “After you get married, you don’t have the final say about whether you have a child or not… If you get pregnant, you will take maternity leave, then I will certainly hire others, and you will be replaced.”[38]

In a January 2020 post on Douban, a woman shared a photo of a form a Guangdong-based apparel company told applicants to fill out during job interviews. The form asked applicants about their family status, including whether they were married, pregnant, or had children—and if they had children, the birth date of the children. A human resources officer told the job seeker that the company was worried that if the children were too young, the applicant would not have the time to devote herself to work.[39]

A recruiter at a mechanical company in Guangxi province said if the company hired women “unmarried with no children,” “in less than two years, they would want to get married and have a child. [They will want to] take some time off to get married, and then more time off to have children. It’s hard to actually do work.”[40]

In order not to have their answers negatively affect their chance of getting a job, some women chose not to answer them honestly. The People’s Daily reported, in May 2018, that Deng Ping, a woman in Beijing who had just graduated from a PhD program, was repeatedly asked during job interviews whether she would have a second child. “I didn’t dare to actually say what I thought. I only kept emphasizing that I would not have a second child,” Deng said.[41] But even those who don’t intend to have a second child feel employers do not believe them. “Actually, I didn’t have plans to have a second child, but companies still worried,” said a mother-of-one working in finance.[42]

Forced to Sign Contracts Promising No Pregnancy

To deter employees from taking maternity leave, some employers require current or newly hired female employees to sign agreements promising not to have a child or not to have one during a certain period. This was particularly common in the first two years following the promulgation of the two-child policy. In some companies and organizations with a large percentage of female workers, female employees of childbearing age were required to queue to take maternity leaves. Those who became pregnant not following the “schedule” incurred penalties and some were fired.

In April 2017, the newspaper Beijing Youth reported that a woman in Shandong province was fined 2,000 yuan (US$300) for having a second child earlier than the time stipulated in the contract between her and her employer. She was “scheduled” to have a second child in 2020, but had one in 2016. “She didn’t inform us in advance at all. Got pregnant ahead of the schedule. This is not being trustworthy,” a representative of her employer told the newspaper.[43]

According to a December 2017 Beijing Evening News report, Chen Xue, a 32-year-old mother of one, was asked during a job interview with a financial firm whether she was planning to have a second child. After Chen said she would not, the firm’s human resources representative asked her to sign a contract promising that she would not have a second child in three years, and said that if she violated the terms, she would be demoted, and her salary decreased.[44]

Guangming Daily reported, in April 2018, that various schools across the country compelled female teachers to sign pregnancy-related agreements. In a vocational school in Hainan, newly hired female teachers had to sign contracts promising that they would not have a child in the first two years of employment. Those who violated the terms would only be given a “pass” during the annual performance review and would not be promoted. Their benefits would also be negatively affected.[45]

In an August 2020 post on Douban, a woman described a job interview in which a company asked her to sign an agreement promising not to get pregnant for the next six years. “This made me—a person who has been urged to have a child for many years but will never want one—want to have a child to show to him on the spot,” the 30-year-old job seeker said.[46]

Fired, Demoted, Sidelined

Numerous women have reported that they have been demoted, sidelined, or fired from their jobs for becoming pregnant. In some cases, they say they believe stress related to these events led them to have miscarriages. Other women have been fired while they were on maternity leave or shortly after they returned.

A joint survey by China Youth Daily and the survey service website Wenjuan, in 2020, found that 51 percent of the respondents said sidelining or pay reduction due to pregnancy is a common problem facing professional women over 30 years of age.[47] In a 2020 book on the impact of family planning policy changes on urban women, Yang Hui, a researcher at the Women’s Studies Institute of China, said that among the 45 percent of respondents who reported their employment was negatively affected by pregnancy or childrearing, over one-third reported income loss, and over 20 percent reported losing opportunities for training or promotions. Another 13 percent said they were fired or forced to resign, and eight percent said they experienced demotion.[48]

Between 2017 and 2019, 47 percent of the cases handled by 074 Professional Women Legal Hotline (074), a legal aid group, concerned pregnancy-based discrimination. Among the women who sought help with such discrimination from 074, 69 percent said they had been fired or forced to resign. Thirteen percent said their positions were shifted, and 11 percent said their wages were withheld.[49]

Human Rights Watch searched the government-run court verdicts database “China Judgments Online” for cases of pregnancy-related lawsuits between January 1, 2016 and January 1, 2021.[50] We found 67 lawsuits concerning pregnancy-related disputes in 26 provinces across the country, involving women from the age of 24 to 47; the actual number of pregnancy-related lawsuits is almost certainly much larger: the government database does not include all lawsuits filed, let alone all lawsuits that conclude in a verdict. Most of the disputes were brought after the women were fired or their contracts were not renewed. A few women also mentioned being demoted or reshuffled to a less desirable position before their contracts were terminated, presumably because their employers wanted them to resign voluntarily.

In December 2016, China Railway Logistics cut three female employees’ pay in half after two of them became pregnant and the third had just returned to work after maternity leave. After the three refused to agree to the new salaries, the company removed their office equipment, revoked their company credentials, and later fired them.[51]Human Rights Watch wrote to China Railway Logistics to confirm and comment on the accounts mentioned above (see Appendix). At time of writing, Human Rights Watch received no response.

In February 2018, a woman surnamed Liu in Shandong province was fired from a trading company on her second day back to work after having a second child, the news website The Paper reported. According to Liu’s husband, Liu had worked for the company for eight years. She had been continually promoted and became the vice president of the company, but was later demoted after having a first child in 2014.[52]

In February 2019, Fan Huiling, 41, a school security guard and mother of one in Guangdong province, was fired days after she informed her employer that she was pregnant. Fan sought advice online and visited government offices for help. She eventually filed for labor arbitration. The next day, she was informed by her doctor that she had had a miscarriage.[53]

In a similar case from September 2018, according to court documents, after learning that Sun Sihan was pregnant, her employer, a technology company in Beijing, made it difficult for her to get approval for time off to focus on her health. The company then suspended Sun’s work email, insurance, and other company privileges when Sun was on leave. “The company’s illegal behavior incurred serious mental harm to me, resulting in me having a miscarriage on September 20, 2018,” Sun said in the court filing[54].

In some cases, employers have forced pregnant employees to resign after making the work environment difficult for them. A pregnant kindergarten teacher in Guangdong province resigned in 2018, after her manager frequently verbally abused her and “made her do activities that were unsuitable for a pregnant woman,” according to a report by Guangming Daily.[55]

After Li Ronghua returned to work after giving birth, the executives at her company criticized her for leaving her desk to pump milk without permission. She was eventually told to quit. Li left the company and later found a new job, but during the interviews for the new positions, she was regularly asked whether she planned to have a second child.[56]

According to a January 2016 report by Wuhan Evening News, a woman surnamed Li in the city of Wuhan was told to resign after she became pregnant. Li refused to resign and told her employer that it was illegal for the company to force her to do so. Although the company backed down, Li felt that her colleagues treated her very differently afterwards and she was not assigned any new work to do. Her supervisors also repeatedly tried to persuade her to quit, saying, “You are soon going to be a mother of two children. You won’t have the energy for work… please don’t make it difficult for me.”[57] Li told the newspaper that the circumstances made her not want to work for the company anymore.

In July 2018, after notifying her employer she was pregnant, an engineer in Changchun, Jilin province, was forced to resign. She took the company to the labor arbitration board and won the case. Yet, when she resumed working for the company in December, seven-and-a-half months pregnant, she found that her position had been changed and she had to work at a construction site in the cold winter.[58]

In some cases, companies have fired employees citing “economic difficulties.” In July 2019, when Lin Jianrong was on maternity leave, her employer, a food company in Fujian province, informed Lin that her labor contract was terminated due to the company’s “extreme operational difficulties,” even though the company was not experiencing business loss, according to court documents.[59] An e-commerce company in Jiangsu province, in April 2020, terminated the labor contract of an employee after learning that she was pregnant, citing the company’s poor business performance due to the pandemic. “Please understand. The company is losing a lot of money, under huge pressure,” a manager told the employee, according to court documents.[60] Human Rights Watch wrote to the food company and e-commerce company to confirm and comment on the accounts mentioned above (see Appendix). At time of writing, Human Rights Watch received no response.

III. Enforcement of Domestic Laws

The Chinese government has failed to uphold domestic law or its international legal obligations to prevent widespread gender and pregnancy-based discrimination and provide remedies for victims of discrimination.

While Chinese laws and regulations contain provisions banning gender and pregnancy-based discrimination in employment, they provide few specific enforcement mechanisms, leaving victims with inadequate avenues for redress. Fines imposed on companies that have violated anti-discrimination laws are too small to serve as a deterrent for future violators. Compensation amounts awarded to victims who are willing to go through the taxing litigation process and win are often too low to make companies change their conduct.

The Chinese government’s history—and escalating practice—of internet censorship and harassing and detaining women’s rights activists has also created chilling effect on women’s rights activism, including campaigns against discrimination in employment.

Chinese Laws on Gender and Pregnancy-Based Discrimination

Chinese government documents concerning pregnancy-based discrimination routinely reference gender discrimination, acknowledging that domestic anti-gender discrimination laws should be applied to cases of pregnancy-based discrimination.

The Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests (妇女权益保障法) states, “women shall enjoy equal rights with men in all aspects of political, economic, cultural, social and family life”; “discriminating against … women is prohibited.”[61] The Labor Law (劳动法), the Employment Promotion Law (就业促进法), and the Provisions on Employment Services and Employment Management (就业服务与就业管理规定) all state that “workers should not be discriminated against because of ethnic group, race, gender, or religious belief.”[62]

China’s Advertising Law (1994, revised 2015) (广告法) bans “gender discriminatory content” in advertising, a provision that on its face should apply to job recruitment ads as well as other forms of advertising. For a published advertisement that violates the law, the advertised entity, the advertising agency, and the entity that publishes the advertisement can each be fined from 200,000 yuan to one million yuan ($30,000 to $150,000) and have their licenses suspended.[63] The Interim Regulations on Human Resources Markets (人力资源市场暂行条例) stipulate that employers can be fined from 10,000 yuan to 50,000 yuan ($1,500 to $7,700) if they refuse to rectify publishing gender discriminatory recruitment ads.[64]

Though the above laws and regulations prohibit gender discrimination, none of them contains a definition of “gender discrimination.”

The Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests states, “No employer shall reduce the pay of female employees, dismiss them, or unilaterally terminate employment contracts or service agreements with them due to circumstances such as marriage, pregnancy (孕期), childbirth (产期) or nursing (哺乳期).”[65] Both the Labor Law (劳动法) and Labor Contract Law (劳动合同法) prohibit the termination of labor contracts during female employees’ “pregnancy, childbirth and nursing.”[66]

Yet, provisions in the Labor Contract Law allow companies to legally terminate employment of any employees, including women who are pregnant or on maternity leave, in a number of situations, such as if those individuals are “proven not to meet hiring requirements during probation period” or “seriously violating employers’ rules and regulations.”[67] This law has been invoked by some companies to justify firing employees who become pregnant.

The Employment Promotion Law bans labor contracts that contain information related to restricting female employees from getting married or having children.[68] The Special Rules on the Labor Protection of Female Employees (女职工劳动保护特别规定) have more specific stipulations on the protections afforded to female employees in relation to childbirth, including that companies cannot require employees who are seven months or more pregnant to work overtime or work at night.[69]

In February 2019, nine Chinese central government agencies, including the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and the All-China Women’s Federation, jointly issued a notice outlining specific measures for implementing existing laws that prohibit gender discrimination in employment. The regulation stipulates that employers are prohibited from inquiring about women’s marriage and childrearing status during job interviews, requiring women to take pregnancy tests in the recruitment process, or conditioning employment on their not being pregnant. Employers and recruiters who publish gender discriminatory job ads can face fines of up to 50,000 yuan ($7,700).[70]

In January 2021, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the government’s main labor administration agency, stated that the ministry will amend and improve anti-gender discrimination laws and strengthen enforcement, so to “protect women’s legal employment rights and interests and reduce the cost of childbearing/childrearing for women.”[71] Human Rights Watch wrote to the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security to inquire about investigative measures and complaint mechanisms available to ensure companies’ adherence to non-discrimination laws (see Appendix). At time of writing, Human Rights Watch received no response.

Weak Enforcement of Provisions Banning Pregnancy-Based Discrimination in Hiring

The Labor Law and the Employment Promotion Law stipulate that labor administration agencies—mainly local human resources and social security bureaus —are the primary government agencies responsible for the enforcement and administration of labor and employment laws and regulations. Any organization or individual can report violations of labor laws and regulations to a local social security bureau and request an investigation.

As detailed in Human Rights Watch’s 2018 report on gender discrimination in job advertisements, authorities, contrary to what they have claimed in public announcements, rarely investigate gender discriminatory job ads without first receiving complaints. In addition, they usually only ordered companies to make corrections and warned them not to repeat their mistakes, rather than imposing fines.[72] In an August 2018 case, after many netizens tagged the Weibo account of the human resources bureau in Changsha city and a person made an official complaint to the mayor’s complaint mailbox, an online media company rescinded all 400 job ad posters across the city that stated “recent graduates and those married and have children preferred.”[73]

Although media stories and social media posts on gender discrimination are relatively common in China, it is rare to find any mention in the media and on social media about authorities investigating companies for discrimination during job interviews. Unlike discrimination in job ads, discrimination during job interviews can be hard to prove: the process is not in writing and employers can deny allegations afterwards. Facing potential liability, some companies have also learned to solicit information through indirect questions. Labor law expert Yan Tian told Beijing News: “For example, they would not ask your marital/childrearing status, but ask you whether the tuition for your local kindergarten is expensive. If they know you have only one child, they would ask whether you think the only child is lonely.”[74]

Some victims of discrimination also worry about the negative consequences of reporting. Under an article on the news website Sina advocating for women report to their local human resources bureau if they encounter gender and pregnancy-related discrimination when looking for jobs, one person commented: “Bamboozle women to report like this, and in the future, it will be even more difficult for women to get job interviews.”[75]

Weak Legal Recourse for Pregnancy-Based Dismissal

Under the Law on Mediation and Arbitration of Labor Disputes, parties to a labor law dispute must go through labor arbitration before cases can be heard by a court. A decision by the labor arbitration board is binding, but if either party is dissatisfied with the arbitration result, they can then take the issue to court. The labor arbitration board is set up by the human resources and social security bureau at various levels of the government. It is staffed mostly by officials from the bureau, but personnel from government-controlled labor unions and companies can also be on the board.[76]

Data is not available on how often arbitration or courts rule in favor of dismissed workers in pregnancy-related cases, but press and social media accounts suggest that even successful claimants often have concluded the process was too onerous and the compensation awarded too low to be worth the effort, or to deter companies from continuing to engage in discrimination.

Employees dismissed for pregnancy-related reasons generally have two ways to seek compensation. One is to request that companies rehire them and pay back wages or maternity leave compensation. There are no additional penalties imposed on companies for unlawful dismissals. The other way is to request compensation for the unlawful termination. The amount depends on the length of employment. The Labor Contract Law stipulates that in general the compensation rate for unlawful termination of labor contract—within which pregnancy-based dismissal falls—is two months of salary for every year of employment. Some victims, especially those who had not worked for the company for a long time or were newly employed, said the compensation felt too low to be worth the effort of going through the legal process.

One main difficulty victims encounter is proving that their termination was in fact due to their being pregnant, rather other reasons employers might give. In some cases, even establishing an employment relationship or actual wages can be hard due to the lack of a paper trail. When Liu Yiran, the Beijing-based woman who was fired from an internet company for being pregnant (the case summarized at the start of this report), took her employer to the arbitration board, the board refused to admit copies of electronic transfer receipts as evidence of her past salary because they were not original documents or notarized. Liu was also unable to produce evidence to prove her work attendance because the company refused to provide that information to her after her departure.[77]

When victims, especially those hired not long before they become pregnant, speak about their cases publicly, they are sometimes accused by their former employer or the public of exploiting the law for their own benefit. In 2019, after two months at her new job as a web designer, a woman surnamed Wang in Liaoning province was fired after informing her employer that she was pregnant. Wang went online to seek help for her situation, and while many netizens offered their advice and support, some questioned Wang’s motives and accused her of using her pregnancy to “take advantage of the company.”[78]

Companies sometimes retaliate, which can further deter victims from seeking redress. Li Xiaoping, a woman in Shandong province, took her former employer, an electronics company, to arbitration after the company fired her for being pregnant. Later, the company sued Li, her husband, a reporter, and a newspaper that wrote about her case for defamation, seeking about $1 million in damages.[79] After Liu Yiran, the Beijing woman mentioned above, posted on WeChat about her experience and that of a colleague of hers, the company sued her for “leaking commercial secrets.” Later the company initiated another lawsuit for “reputational damage” after Liu spoke to an online media platform.[80]

IV. China’s International Legal Obligations

Discrimination on the Basis of Gender

Discrimination on the grounds of gender is prohibited under core international human rights instruments and treaties to which China is a party. As a United Nations member state, China has affirmed acceptance of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, whose provisions are broadly accepted to reflect customary international law.[81] The declaration upholds the fundamental rights and freedoms that are due to every individual on the basis of their being human: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” and are protected from discrimination, arbitrary interference in privacy, family and home.[82]

Under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), China is obligated to “ensure the equal right of men and women” to enjoy all covenant rights, including the right to work.[83] Governments also are obligated to take “measures to combat discrimination and to promote equal access and opportunities.”[84]

Bodily Autonomy and Reproductive Rights

The two-child policy is a fundamental and deeply intrusive violation by the Chinese government of women’s right to reproductive choice and bodily autonomy. The right to bodily integrity and the right of a woman to make her own reproductive choices are enshrined in a number of international human rights treaties and instruments.

The right to sexual and reproductive health is an integral part of the right to health, enshrined in article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[85] As the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights noted in its General Comment No. 14 on the right to the highest attainable standard of health, “The realization of women’s right to health requires the removal of all barriers interfering with access to health services, education and information, including in the area of sexual and reproductive health.”

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), in article 16, guarantees women equal rights in deciding “freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children and to have access to the information, education and means to enable them to exercise these rights.”[86]

The Beijing Platform for Action from the UN Fourth World Conference on Women states that “the human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.”[87]

Pregnancy-Based Employment Discrimination

Pregnancy as a condition is inextricably linked to being female. Consequently, when women are treated in an adverse manner by their employers or potential employers because they are pregnant or because they may become pregnant, they are being subjected to a form of sex discrimination by targeting a condition childbearing women experience.

Pregnancy discrimination is not limited to the refusal to hire pregnant job applicants and the firing of pregnant workers, but also includes any behavior or practice that aims to determine pregnancy status or plans.

The preamble to CEDAW states that “the role of women in procreation should not be a basis for discrimination.” Under CEDAW, China is obligated to take “appropriate measures” to “eliminate discrimination against women in the field of employment,” and to “prohibit, subject to the imposition of sanctions, dismissal on the grounds of pregnancy or of maternity leave.”[88]

The International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Convention on Discrimination in Employment and Occupation, which China has ratified, obligates governments to enact and implement legislation that prohibits all forms of gender-based discrimination.[89] The Maternity Protection Convention (No. 183), which China has not ratified, requires states to provide protection for pregnant women or nursing mothers from discrimination based on maternity.[90]

Recommendations

The Chinese government should demonstrate its long-professed commitment to gender equality in employment through targeted legal reforms and vastly improved enforcement of existing laws and regulations banning gender and pregnancy-based discrimination.

To the Chinese Government and the National People’s Congress

- End the two-child policy and all restrictions on women’s reproductive rights.

- Stop harmful and discriminatory propaganda pressuring women to have children and encouraging them to leave the workforce.

- Enact and enforce a comprehensive employment anti-discrimination law that:

- Contains a definition of gender discrimination that encompasses the full range of ways in which employers discriminate against women, protecting against both direct discrimination and discriminatory impact;

- Explicitly prohibits childbearing status-specifications in job advertisements and imposes penalties sufficient to deter future violations;

- Ensures effective remedies for women who have been dismissed while pregnant, and while on or soon after returning from parental leave, including compensation to victims for the harm they suffered; and

- Establishes penalties for companies that discriminate against women based on their real or perceived childbearing status, including fines sufficient to deter employers from future violations.

- Amend relevant laws and regulations to create equal access to caregiving leave for women and men and incentives for men to use this leave.

- Adopt ILO Maternity Protection Convention (No. 183).

- Cease all forms of harassment, intimidation, and arbitrary detention of women’s rights activists.

To the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security

- Strengthen the investigation of complaints of pregnancy-based discrimination submitted to the ministry and its local affiliates.

- Proactively supervise and regularly inspect employers to ensure they comply with anti-discrimination provisions in relevant employment laws and regulations.

- Increase the penalties imposed on employers that discriminate to better deter future offenses.

- Address, in cooperation with nongovernmental women’s rights activists and groups, prevailing gender stereotypes in employment, including through awareness-raising campaigns.

To the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and the International Labour Organization

- Call on the Chinese government to ensure that domestic laws fully comply with China’s international legal obligations with regard to non-discrimination and equal treatment in employment.

- Call on the Chinese government to comply with and enforce domestic laws and policies against employment discrimination to comply with China’s obligations under international law.

- Provide training to relevant Chinese government bodies, including inspectors at the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and its local affiliates, on equal-right-to-employment issues and investigative techniques.

To UN Population Fund (UNFPA)

- Call on the Chinese government to end the two-child policy and allow all couples and individuals to decide freely the number, spacing, and timing of their children.

- Work with women’s rights activists and independent nongovernmental organizations in China to advance the reproductive rights of women in China.

To UN Women

- Call on the Chinese government to enforce and amend anti-gender and pregnancy discrimination laws and regulations.

- Work with, and provide assistance to, women’s rights activists and independent nongovernmental organizations in China to raise awareness of legal protections afforded to victims of gender and pregnancy-based discrimination.

- Provide technical and financial assistance to victims of gender and pregnancy-based discrimination in seeking redress.

To National and Foreign Companies Operating in China

- Adopt and enforce company policies prohibiting all forms of gender and pregnancy-based discrimination in the workplace.

- Adopt and enforce job-hiring policies that are nondiscriminatory, including on the basis of gender and childbearing status.

- Provide adequate leave for women who need pre-natal and post-natal care and provide facilities and flexibility to support employees who are breastfeeding.

- Provide adequate caregiving leave equitably to female and male employees and encourage male employees to use this leave.

- Consider providing or subsidizing childcare for female and male employees who are parents.

- Adopt gender equality due diligence policies in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and conduct proper due diligence.

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Yaqiu Wang, China researcher in the Asia Division at Human Rights Watch. This report was edited by Sophie Richardson, China director; Heather Barr, interim co-director of the Women’s Rights Division; Arvind Ganesan, director of the Business and Human Rights program; Brian Root, quantitative analyst; and a consultant with the health team. James Ross, legal and policy director, and Joseph Saunders, deputy program director, provided legal and programmatic reviews. Production assistance was provided by Racqueal Legerwood, Asia coordinator; Travis Carr, digital publication coordinator; and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

This report was also reviewed by an expert on women’s rights in China who did not wish to be named.

Human Rights Watch is grateful to the Chinese women’s rights activists who agreed to be interviewed, despite the risks, and who provided invaluable input to this report.