Summary

The armed conflict in Yemen, which escalated in March 2015, continues to kill, injure, and displace thousands of Yemeni civilians. As of August 2018, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) had documented the killing of 6,592 civilians and the wounding of 10,470 in Yemen, with airstrikes by the Saudi Arabia-led coalition causing the majority of the verified civilian casualties. Many millions more suffer from shortages of food and medical care. Despite mounting evidence of violations of international law by the parties to the conflict, efforts toward accountability have been woefully inadequate.

In August 2016, the coalition, then consisting of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Sudan, and Qatar, announced the first results of the coalition’s recently created investigative mechanism, the Joint Incidents Assessment Team (JIAT). JIAT originally consisted of 14 individuals from the main coalition members. It has a mandate to investigate the facts, collect evidence, and produce reports and recommendations on “claims and accidents” during coalition operations in Yemen.

In this report, Human Rights Watch examines the way JIAT has investigated coalition compliance with the laws of war and civilian harm through a post-strike analysis. The report finds that more than two years after JIAT began investigating coalition airstrikes, its public findings continued to display many of the same fundamental problems of the body’s first findings. The limited information available to the public shows a general failing by JIAT – for unclear reasons – to provide credible, impartial, and transparent investigations into alleged coalition laws-of-war violations.

To illustrate some of Human Rights Watch’s concerns regarding JIAT’s work, this report describes factual and legal discrepancies between JIAT and Human Rights Watch reporting and analysis in 17 strikes. JIAT’s public conclusions raised serious questions regarding the ways in which JIAT is conducting investigations and applying international humanitarian law. Others, including the UN Panel of Experts, Amnesty International, and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, or Doctors Without Borders), have reached similar conclusions about JIAT’s failings following their own inquiries into other strikes investigated.

Over the past two years, JIAT has failed to meet international standards regarding transparency, impartiality, and independence. Established in the wake of mounting evidence of coalition violations, the body has failed even in its limited mandate to assess “claims and accidents” that occurred during coalition military operations. JIAT has not only conducted its investigations without a transparent methodology, but appears to have regularly failed to conduct a thorough laws-of-war analysis in its investigations and produced flawed and dubious conclusions. JIAT appears only to have investigated coalition airstrikes, but not other alleged violations of international law by coalition members, such as UAE abuses against people in detention.

On July 31, 2018, JIAT reported it had investigated its 79th incident. Most JIAT statements are released on the official Saudi state news website, but not all investigations are numbered. Human Rights Watch reviewed statements JIAT released publicly in English and Arabic and news conferences conducted by the JIAT spokesman since August 2016, interviewed members of other organizations following JIAT’s work, and identified 75 of JIAT’s reports. It is unclear whether JIAT did not release the remaining four findings publicly, or if there is another cause for the discrepancy. In those 75 reports, JIAT:

- Absolved coalition members of legal responsibility in the vast majority of attacks;

- In most cases finding that the coalition acted lawfully, did not carry out the reported attack, or that a mistake was “unintentional,” often due to technical errors.

- Recommended the coalition provide assistance in about 12 attacks, without necessarily finding fault:

- Five of the 12 attacks resulting from technical errors;

- Four of the 12 attacks involving other “unintentional” errors, including faulty intelligence, bad weather, a building not recognized as a hospital, and a mistaken missile launcher;

- One attack recommending assistance for resulting civilian loss.

- Recommended “appropriate action” – further investigation or disciplinary action – in two attacks;

- Finding coalition officers had violated the rules of engagement in one attack and recommending investigating possible violation of the rules of engagement in another.

JIAT provides no information regarding its decisions whether or when to release its investigation results. Three large batches of investigation results appear to have been released to respond to international events. JIAT released incident results on September 12, 2017 during discussions at the UN Human Rights Council regarding the possible creation of an international investigation into violations in Yemen; Saudi diplomats and their allies then used the released JIAT results to argue against the need for an international mechanism. On March 5, 2018, JIAT released results immediately before Saudi Crown Prince and Coalition Commander Mohammed bin Salman travelled to the United Kingdom to meet with senior British officials. And, on June 7, 2018, JIAT released results shortly before a planned major coalition offensive to capture Hodeida city, which had generated broad concerns that an attack on Yemen’s most important port would have dire humanitarian consequences for the population.

JIAT has not addressed certain coalition violations of international law. Since March 2015, coalition officials have repeatedly made false statements about coalition compliance with the laws of the war. After repeated denials that the coalition used widely banned cluster munitions in Yemen, the coalition in late 2016 claimed to be using lawfully at least one type of cluster munition. Before the admission, Human Rights Watch had documented 17 cluster munition attacks using types of cluster munitions different from the one type the coalition eventually acknowledged using. JIAT has not seriously investigated any of these cluster munition attacks.

The United States, which is a party to the conflict because of its operational, logistical, and intelligence support to the coalition, and the UK, which supports the coalition, often claim the coalition has “improved” its targeting practices during the conflict. As Saudi Arabia’s largest weapons suppliers, the US and UK have continued to sell billions of dollars’ worth of weapons to Saudi Arabia and other coalition states throughout the conflict. In six of the attacks investigated by JIAT discussed in this report, Human Rights Watch identified US-origin munitions used in the attack. Officials have asserted that the coalition’s efforts to investigate through JIAT indicate that Saudi Arabia and other coalition members are engaged in a good faith effort to comply with international humanitarian law.

Those countries that continue to sell weapons to Saudi Arabia—including the US, UK and France—risk complicity in future unlawful attacks, particularly given that coalition assurances to take action have proven hollow.

The coalition has repeatedly promised to minimize civilian harm in future military operations, but the coalition’s lack of transparency makes it nearly impossible for independent observers to analyze whether the coalition has in fact made changes, let alone enforced them. Human Rights Watch has continued to document coalition attacks in 2017 and 2018 that appear to violate the laws of war.

Impartial investigations into alleged laws-of-war violations are only the first step toward meeting international legal obligations regarding accountability for abuses and justice for victims. Human Rights Watch calls on coalition member states to meet their own obligations under international law to investigate alleged serious violations by their armed forces and persons within their jurisdiction, to appropriately prosecute military personnel responsible for war crimes, and to provide reparation to victims of unlawful attacks and support a unified, comprehensive mechanism for providing ex gratia (“condolence”) payments to civilians who suffer losses due to military operations, regardless of an attack’s lawfulness.

The coalition’s failure to comply with the laws of war goes far beyond the failings of any particular JIAT investigation. JIAT has only investigated a fraction of the coalition attacks that Yemeni and international rights groups and the UN have reported as raising laws-of-war concerns. Human Rights Watch has documented 88 apparently unlawful coalition attacks since March 2015—JIAT has investigated about a quarter of them. The UN and rights groups have documented dozens of other apparently unlawful coalition airstrikes. In many of these attacks, the coalition, coalition officials, or JIAT have failed to acknowledge the coalition’s role. A UN Panel of Experts found that, except for two of 10 attacks the panel investigated in 2017, the coalition had not “acknowledged its involvement in any of the attacks, nor clarified, in the public domain, the military objective it sought to achieve.”

Many of the apparent laws-of-war violations committed by coalition forces show evidence of war crimes – serious violations committed by individuals with criminal intent. JIAT investigations show no apparent effort to investigate personal criminal responsibility for unlawful airstrikes. This apparent attempt to shield parties to the conflict and individual military personnel from criminal liability is itself a violation of the laws of war. And Saudi and Emirati commanders, whose countries play key roles in coalition military operations, face possible legal liability as a matter of command responsibility – when a commander knows or should have known that subordinates were committing abuses yet took insufficient action to stop them or punish those responsible. Many senior officials in the Saudi and Emirati militaries, who have played a leading role in coalition operations throughout the conflict, remain in positions of power and authority.

While JIAT has recommended in a handful of strikes that the coalition provide “assistance” or take “appropriate action,” Human Rights Watch is unaware of any concrete steps the coalition has taken to implement a compensation process or to hold individuals accountable for possible war crimes. Exceptionally, the Yemeni National Commission to Investigate Alleged Human Rights Violations reported the government of Yemen had referred several Yemeni officers to a Yemeni military court for prosecution.

On July 10, 2018, Saudi Arabia’s King Salman issued a royal decree "pardoning all military personnel who have taken part in the Operation Restoring Hope [begun in April 2015] of their respective military and disciplinary penalties.” The sweeping and vaguely worded statement did not clarify what limitations, if any, applied to the pardon.

Houthi forces opposed to the coalition have also carried out frequent violations of the laws of war, including likely war crimes. Human Rights Watch has documented the Houthis using antipersonnel landmines, deploying child soldiers, indiscriminately shelling Yemeni cities, and torturing detainees, among other abuses. Human Rights Watch has not identified any concrete steps the Houthis have taken to investigate potentially unlawful attacks or hold anyone responsible to account.

The UN Security Council has already imposed travel bans and asset freezes on Houthi leaders and their former allies through an existing sanctions mechanism that allows the designation of individuals responsible for violations of international humanitarian law. The council has not done so with respect to the Yemeni government or coalition members despite evidence of the coalition’s responsibility for sanctionable actions. Any country can suggest names to the UN Yemen Sanctions committee, triggering immediate consideration of Security Council action. Unless the coalition ends its unlawful attacks, credibly investigates past allegedly unlawful attacks, and appropriately prosecutes those responsible, and provides civilian victims redress, the council should immediately consider imposing targeted sanctions on individuals who share the greatest responsibility for repeated coalition laws-of-war violations, notably Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and other senior coalition commanders.

The failure of warring states to carry out prompt, credible, and impartial war crimes investigations means that other avenues to preserve a path to justice should be considered. The UN Human Rights Council should renew and strengthen the mandate and reporting structure of the Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen, which currently reports to the Human Rights Council indirectly. The government of Yemen, which has a duty to protect all Yemenis from harm, should, as a matter of urgency, join the International Criminal Court (ICC). Judicial authorities in other countries should also investigate those suspected of committing war crimes under the principle of universal jurisdiction and in accordance with national laws. States should pursue processes for gathering criminal evidence to advance future prosecutions.

Recommendations

To Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Other Coalition Members, and Yemen

- Abide by the laws of war, including the prohibitions on attacks that target civilians and civilian objects, that do not discriminate between civilians and military objectives, and that cause civilian loss disproportionate to the expected military benefit.

- Conduct credible, impartial, and transparent investigations into alleged violations of the laws of war involving national armed forces in Yemen.

- Appropriately prosecute military personnel, including as a matter of command responsibility, who are responsible for war crimes in Yemen.

- Promote credible, impartial, and transparent investigations by the Joint Incidents Assessment Team (JIAT).

- Provide prompt and adequate redress for civilian victims and their families for deaths, injuries, and property damage resulting from wrongful strikes. Adopt a unified, comprehensive mechanism for providing ex gratia (“condolence”) payments to civilians who suffer losses due to military operations, regardless of the attack’s lawfulness.

- Create a mechanism to communicate investigation results to civilian victims and their relatives, even if payments are currently not possible. Consider non-monetary forms of redress, such as apologies, as a temporary measure.

- Regularly publish civilian casualty figures from airstrikes, including participating armed forces. Publish, and continually review to improve accuracy, the methodology for distinguishing between civilians and combatants. Where feasible, interview witnesses and conduct site inspections.

- Ensure rules of engagement are fully consistent with the laws of war, and continually review them to minimize civilian loss.

- Take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians, including making advance effective warnings of attacks when possible.

- Do not use explosive weapons with wide area effects in populated areas. Cease the use of inherently indiscriminate weapons, such as cluster munitions, in all circumstances.

To the Joint Incidents Assessment Team

- Publicly clarify the procedures used to decide which incidents to investigate and provide a list of incidents currently being investigated.

- Promptly release the findings of investigations, including conclusions, with as few redactions as possible. Create a mechanism to communicate the results of investigations to civilian victims and their families.

- Include in the published findings of investigations the national armed forces that participated in specific attacks, including command and control, tactical intelligence, support operations such as in-air refueling, and tactical engagement.

- Include in the published findings of investigations information on accountability measures taken by relevant coalition members, including disciplinary action and criminal prosecutions, and compensation or ex gratia payments, if any, provided to civilian victims or their families.

- Provide information to victims and their families on submitting claims for loss. Set out general standards applied for payments.

- Investigate laws-of-war violations beyond targeting, including use of cluster munitions and detention-related abuses.

- Cooperate with Yemeni, United Nations, and nongovernmental organizations, including seeking and sharing information to the extent practicable. Provide guidelines for organizations and individuals to alert JIAT to incidents that resulted in civilian casualties or may have violated the laws of war.

- Assist governments undertaking their own investigations of alleged laws-of-war violations.

- Make full use of the investigatory tools available. This should include military intelligence, operational information, and targeting videos. Where feasible obtain information from the target site and interview witnesses. If on-site investigations are not feasible, explore ways to meet or otherwise communicate with witnesses.

- Provide public information on JIAT members, including their position, any relevant legal or military experience, and reporting structures.

To Houthi and Allied Forces

- Abide by the laws of war, including the prohibitions on attacks that target civilians and civilian objects, that do not discriminate between civilians and military objectives, and that cause civilian loss disproportionate to the expected military benefit.

- Appropriately punish commanders and fighters responsible for abuses of international law.

- Ensure all persons taken into custody are treated humanely and have access to lawyers and family members. Individuals should only be detained if they are captured combatants or for imperative security reasons.

- Do not use explosive weapons with wide area effects in populated areas. Cease the use of inherently indiscriminate weapons, like antipersonnel landmines, in all circumstances.

- Avoid placing military objectives in densely populated areas and take steps to remove civilians from areas under attack.

To Yemen

- Accede to the Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

To the United States

- Conduct investigations into any airstrikes for which there is credible evidence that the laws of war may have been violated and that the United States participated, including by refueling participating aircraft, providing targeting information and intelligence, or other tactical support.

- Publicly clarify the US role in the conflict, including what steps the US has taken to minimize civilian casualties in air operations and to investigate alleged violations of the laws of war.

To France

- Create a parliamentary inquire into French arms sales to Saudi Arabia and other coalition members.

To Coalition Supporters, including the United States, United Kingdom, and France

- Given the coalition’s continued failure to credibly investigate alleged violations, including through JIAT, as well as ongoing violations of the laws of war, suspend all weapon sales to Saudi Arabia until it curtails its unlawful airstrikes in Yemen and credibly investigates alleged violations.

- Cease the supply of any weapons, munitions, and related military equipment to parties to the conflict in Yemen where there is a substantial risk of these arms being used in Yemen to commit or facilitate serious violations of international humanitarian law or international human rights law.

- Urge coalition members to implement the above recommendations.

To United Nations Security Council Members

- Request the Yemen Sanctions Committee Panel of Experts to produce a special report on individuals responsible for violations of applicable international human rights and humanitarian law or obstructing humanitarian aid, including chains of command and control and command responsibility within the Saudi-led coalition.

- Impose targeted sanctions on Mohammed bin Salman and other senior commanders substantially responsible for military operations that have resulted in widespread violations of the laws of war and without taking serious steps to end the abuses.

To United Nations Human Rights Council Members

- Renew and strengthen the mandate of the Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen, enhancing its reporting structure so that it reports directly to the Human Rights Council and to the General Assembly, and strengthening language on accountability.

Methodology

Since the Saudi-led coalition’s intervention in Yemen’s armed conflict in March 2015, Human Rights Watch has conducted field research in the north and south of the country, including Sanaa, Aden, Saada, and Hodeida governorates, among others. When conducting investigations into possible unlawful airstrikes, Human Rights Watch sought to gather a range of information, including interviews with victims, witnesses, and medical workers in person or by telecommunication, analysis of satellite imagery, and examination of physical evidence such as weapons’ remnants, videos, and photos of the strike site.

For this report, Human Rights Watch also conducted interviews with local activists, domestic and international human rights and humanitarian organizations, lawyers representing victims, and Yemeni government officials. Human Rights Watch analyzed public statements that the Joint Incidents Assessment Team (JIAT) produced over the last two years, as well as statements by coalition officials posted on government websites.

All interviewees provided consent to be interviewed and were informed of the purpose of the interview and how their information would be documented or reported. No one received remuneration for giving an interview.

In 2017, Human Rights Watch wrote to the coalition and its current and former member countries seeking information on any investigations and findings. In 2018, Human Rights Watch wrote to JIAT, and sent a copy to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait, whose nationals sat on JIAT when it was initially announced. No current member of the coalition has responded. Qatar provided a written response in June 2018, which is included as an annex to this report. Future responses from coalition member states will be posted on the Yemen page of the Human Rights Watch website.

Unlawful Coalition Airstrikes Continue

In June 2017, the New York Times reported that Saudi Arabia provided the United States assurances that coalition forces would adhere to stricter rules of engagement and consider specific estimates about potential harm to civilians in targeting—a practice US officials told the Times the coalition had not fully integrated into its operations.[1] These assurances reportedly came ahead of a US$110 billion arms sales package to Saudi Arabia. In the three months after the New York Times reported the changes, Human Rights Watch documented six coalition airstrikes that appeared to violate the laws of war. Together these strikes killed 55 civilians, including 33 children, and wounded dozens more.[2]

Despite repeated promises to minimize civilian harm during their military campaign, the coalition continued to carry out unlawful airstrikes in Yemen in 2018. One apparently unlawful coalition attack investigated by Human Rights Watch is described below. Other human rights organizations, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), and humanitarian agencies reported on additional apparently unlawful coalition strikes on civilians and civilian objects in 2018.[3] In August, OHCHR reported that coalition airstrikes remained the leading cause of civilian casualties.[4]

April 22, 2018, Wedding in Bani Qais, Hajjah

On April 22, 2018, coalition aircraft bombed a wedding in al-Raaqah village in Bani Qais district, Hajjah governorate. The attack killed at least 22 people, including eight children, and wounded at least 54 others, including 26 children, according to witnesses and health workers who received the wounded following the attack.[5] The groom, 25, and bride, 24, survived, but as one wedding guest said, “In a minute, he was a groom getting ready for his wedding, and now he is homeless and lost everything.”[6]

Wedding guests said they noticed coalition aircraft circling the area at about 10 o’clock in the evening. Anas al-Musabi said he left the wedding early and went home, about a 20-minute drive away. While sitting on his roof chewing qat (a popular mild stimulant), he heard an aircraft flying back and forth. At about 10:10 p.m., he saw the plane drop a bomb.[7]

Haydar Masoud arrived at the wedding in the early evening, after the Asr prayer. Masoud, sitting with friends a few meters away from the main wedding tent, noticed aircraft flying above:

Suddenly, I heard something like a wheeze for a few seconds. Then, I didn’t hear anything else— not a blast, nothing.… After that wheeze, everything fell down.... I stood up and started running barefoot toward my house … my friends were running too.… We were speaking to each other … but no one was hearing the other, I was just seeing them moving their mouths.

The bride’s uncle, Abdo Show’ai, a worker in his mid-thirties, was with the men in a tent attached to the groom’s house. He briefly heard the sound of planes, but the wedding was loud. A moment before the attack, a man sitting next to him received a phone call from a friend who worked with the Houthis, warning him the coalition might attack the area. Then, “Everything fell down over our heads.” Show’ai said he didn’t hear a blast, but he felt heat: “I thought I was on fire. I was covered with dust…. I tried to run, but I kept falling.” His wife came toward him:

I stopped her and asked her, ‘Where are my kids? Where are my kids?’ The scene was awful. People without limbs and some, their heads were open and bleeding. My wife was searching and was screaming every time she saw someone she thought was her family members. It was very hard to identify people, due to the dark and most people being disfigured.

His children were scared, and his 8-year-old daughter Ashwaq had fractured her arm.[8]

Ali Omar, 52, a member of Hajjah’s local council who lived nearby, said he heard the blast. He and his 30-year-old nephew immediately drove toward the wedding on their motorbike: two of his adult sons were attending. Three or four people were trying to rescue the wounded, but others were “afraid of another airstrike,” Omar said. It was dark, so he used his phone as a flashlight to look for his sons. He saw his son’s belt, then his phone cover, then his shawl. “I was certain they both died. I kept looking and searching.” That night, Omar pulled at least 10 bodies out from the rubble:

I couldn’t recognize them at all, because of the dark, and the bodies were completely burned.… The last one I saw was a guy, cut into two. Part, over a tree, and the rest hanging from it. I felt so sick when I saw that scene, I even felt that my feet can’t hold me, and I fell.… When I was searching and digging in the rubble, I heard the weeping of the families who are grieving for their people, who they don’t know if they are alive or dead.

Finally, his cousin called. Omar began shouting—he needed the light on his phone to continue searching. When his cousin convinced Omar to listen to him, he told him his sons had fractured limbs, but were alive and safe with him.[9]

Those with serious wounds were taken first to the al-Tour health center and then transferred to al-Jumhori hospital in Hajjah, about two and a half hours away.[10] Dr. Muhammad al-Saoumli, the head of the hospital, said they received more than 50 wounded people from the attack, mostly children. “Most of the cases were critical,” he said, including four people whose lower limbs were amputated.[11]

A wedding guest provided Human Rights Watch a list of the full names and ages of those killed or wounded. The list included 18 wedding guests, including eight children ranging in age from 7 to 15, who were killed. Another four men hired as drummers were also killed, although the guest did not know their names or ages. He provided a separate list of 54 names and ages of those wounded in the attack, all also guests, including 26 children. Other guests and health workers at the clinic and hospital reported similar casualty numbers.[12]

Human Rights Watch was unable to identify any military objective in the area. Three men from the area said there was no military target close to the wedding; it was the first time the coalition had bombed the village since the beginning of the conflict.[13] Anas al-Musabi said, “All people [in their village] were feeling safe, because there is no military site close to us, and we live in a very remote area, very hard to access, very hard to pass through, there is not even an asphalt road to the village.”[14] One man said the closest military target was a Houthi checkpoint about an hour’s drive from the site of the attack.[15]

OHCHR and the UN secretary-general each issued statements condemning the attack.[16] Col. Turki al-Maliki, the coalition spokesperson, announced that the coalition’s joint command was reviewing the incident. At the time of writing, the Joint Incidents Assessment Team had not publicly released information regarding a possible investigation.[17]

On April 30 Abdo Show’ai and his relative provided Human Rights Watch with photographs they had taken of bomb remnants they found near the tent and house. The items in the photographs are remnants of a US-made Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) satellite guidance kit, which is attached to an airdropped bomb prior to use. Human Rights Watch found the same type of remnants after the coalition attack on the al-Zaydiya Security Administration on October 29, 2016.[18]

JIAT’s Failure to Credibly Investigate Possible Violations

International humanitarian law, or the laws of war, requires that states investigate alleged war crimes by their nationals and appropriately prosecute those responsible.[19] Deliberate, indiscriminate, or disproportionate attacks on civilians and civilian objects are serious violations of the laws of war. When committed by an individual with criminal intent – that is, intentionally or recklessly – they are war crimes.[20]

Human Rights Watch’s analysis of Joint Incidents Assessment Team (JIAT) reports has found that they have been seriously flawed, dismissing allegations of coalition violations without adequate basis or severely downplaying the extent of the wrongdoing. Reviewing JIAT investigations has been difficult in large part because its methodology has not been transparent. JIAT does not provide public information on the threshold it uses to determine whether an incident should be investigated; its investigative methodology, including whether and under what circumstances it conducts site visits and witness interviews, or relies on flight recordings; the role in a particular attack of specific coalition members or non-coalition parties to the conflict such as the United States; and the status of its recommendations.

Human Rights Watch examined seven airstrikes in which JIAT’s findings included clear factual discrepancies that call its methodology into question. In two, JIAT concluded that coalition forces did not conduct airstrikes on the day or place in question. In one of the attacks, on a home in Saada in 2017, physical evidence present at the location shows that airstrikes were carried out.[21] In the other, near a factory in Amran in 2016, JIAT did not carry out a full investigation, using an incorrect date—“2015” rather than “2016” in a United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) report—as the basis for concluding the coalition did not carry out the attack; a full review of the document would have made the misprint clear. In 2018, the UN Security Council-appointed Panel of Experts found that while their own “independent investigations found clear evidence of air strikes,” JIAT concluded the coalition did not carry out two additional 2016 strikes on a food factory in Sanaa and a residential complex in Ibb.[22]

The five other attacks discussed below raise questions regarding JIAT’s assessments of civilian casualties. Although JIAT reports often cite other organizations’ findings on civilian harm or damage, JIAT frequently did not conduct its own assessment of civilian harm, left out any of its own, even rough, civilian casualty counts and did not discuss broader “harm” caused by the strike—for example the impact of damaging critical civilian infrastructure. In some cases, JIAT concluded that certain structures were not damaged, or were only partially so—clearly contradicting physical evidence collected from the strike site and available publicly at the time JIAT was conducting its investigations. While JIAT often claimed it was responding to international rights or humanitarian organizations’ reports, including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the UN Panel Experts, JIAT has never contacted Human Rights Watch or Amnesty International to discuss specific findings.

February 15, 2016, Cement Factory, Amran

JIAT concluded for the third of three reported airstrikes on a cement factory in Amran governorate that “the coalition was not established yet.”[23] JIAT was responding to OHCHR reporting about an attack that OHCHR’s August 2016 report stated took place on February 18, 2015—indeed before the coalition had been established.[24] But this was a typographical error on the part of OHCHR: the same sentence cited a February 2016 monthly UN report and the same August 2016 OHCHR report that JIAT referred to discussed an attack on February 19, 2016 when the coalition used cluster munitions on a mountain near the factory. Human Rights Watch also investigated and published information about an attack near the factory in mid-February 2016, after which cement factory workers collected remnants that Human Rights Watch identified as US-supplied cluster munitions. The use of cluster munitions on the mountain, in close proximity to a nearby village, constitutes an unlawful indiscriminate attack.[25] The coalition should have investigated the attack.

August 4, 2017, Mahda Home, Saada

JIAT asserted that, after reviewing flight schedules and satellite images, the coalition did not carry out an airstrike on the Mahda area on August 4, 2017 following reports the coalition bombed a residential home.[26] In an earlier Saudi Press Agency statement, Col. Turki al-Maliki, coalition spokesperson, denied reports the coalition targeted the house, saying the coalition was continuing to investigate in coordination with the government of Yemen and other international partners “on this unfortunate incident,” noting Houthi-Saleh forces store “weapons and explosives inside houses and civilian objects.”[27]

Human Rights Watch also investigated the attack. Videos and photos of the attack show damage consistent with the detonation of a large air-dropped bomb that used a delayed-action fuze.[28] Two witnesses and the director of the local hospital said the attack killed nine members of the same family, including seven children, and wounded three. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), whose staff members visited the village soon after the attack, also reported that the coalition attacked a house, killing nine people.[29]

The coalition airstrike hit a civilian object, killing and wounding civilians, in the absence of any apparent military objective, violating the laws of war. The coalition should conduct a criminal investigation to determine if war crimes had been committed and pay compensation to civilian victims.

March 15, 2016, Mastaba Market, Hajjah

After investigating a March 15, 2016 attack on a market in Hajjah, JIAT concluded – without providing any explanation of its methodology – that the attack complied with the laws of war, as the strike was “based on solid intelligence asserting that a large gathering of Houthi armed militia (recruits), and that the gatherings were near a weekly market, which

does not have any activity except on Thursdays.”[30] The strike occurred on a Tuesday, but residents of the area told Human Rights Watch there were stalls and shops open every day of the week. JIAT went on to note “the claiming party did not provide proof of the claims [of] civilian casualties.” While it is not clear what JIAT intended with this statement, the legal obligation rests with participating states to investigate credible allegations of serious laws-of-war violations.

Human Rights Watch’s findings, as well as those of the UN, which sent a human rights team to visit the site the day after the attack, drastically differed from JIAT. Human Rights Watch conducted on-site investigations on March 28 and interviewed 23 witnesses to the airstrikes, as well as medical workers at two area hospitals that received the wounded.[31] Whereas JIAT appears to conclude there were no civilian casualties, Human Rights Watch and the UN found the two airstrikes on a crowded market killed at least 97 civilians, including 25 children. Two Mastaba residents told Human Rights Watch that many members of their extended families had died – one lost 16 family members, and the other 17 – and a local clinic supported by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, or Doctors Without Borders) received 45 wounded civilians from the market, 3 of whom died.[32]

While the strike may have also killed about 10 Houthi fighters and there was a Houthi military checkpoint manned by two or three fighters located about 250 meters north of the market, the strikes caused indiscriminate or foreseeably disproportionate loss of civilian life, in violation of the laws of war. The Houthis’ possible use of a building in the market as a barracks would have amounted to failure to take all feasible precautions to protect civilians under their control from the effects of attacks but would not have justified the coalition airstrikes as carried out. On March 16, the day after the attack, then-coalition spokesman Gen. Ahmad al-Assiri said the coalition targeted “a militia gathering” and that the area was a place for buying and selling qat, indicating the coalition knew the strike hit a civilian commercial area.[33]

An unlawful attack should be criminally investigated for possible war crimes and to provide redress to civilian victims.

October 26, 2015, Haydan Hospital, Saada

In the immediate aftermath of an attack on a hospital in Yemen in October 2015, then-coalition spokesman Assiri initially denied a coalition airstrike hit the Saada hospital, which was supported by MSF. The same day, the Saudi ambassador to the UN acknowledged the coalition carried out the attack, but called it a “mistake,” claiming the coalition had targeted a field “used by the Houthis for training and ammunition gathering,” and faulting MSF for sending incorrect coordinates.[34] In its analysis, JIAT, which offered no details on the types of evidence examined or sources consulted, acknowledged the coalition struck the hospital on October 26, 2015, but alleged the Houthis were using the hospital as a military shelter. JIAT concluded the coalition should have warned MSF before bombing the building but did not find any other fault on the part of the coalition as, according to JIAT, the hospital had become a military target.[35]

Human Rights Watch interviewed MSF-Yemen country staff the night of the strike and reviewed photos from MSF and other local sources showing damage to the building and the MSF-logo painted clearly on the roof.[36] MSF regularly shared its coordinates with the coalition. In contrast to JIAT’s conclusion that “there was no human damage as a result of the bombing,” Human Rights Watch confirmed that two patients were injured during the evacuation of the hospital. The hospital was also forced to shut down; the attack destroyed or damaged multiple wards. The hospital was the only medical facility for about 200,000 people living within an 80-kilometer radius, which received about 150 emergency cases a week.[37]

Human Rights Watch found no evidence Haydan hospital was being used for military purposes. Hospitals only lose their protection from attack if they are being used outside their humanitarian function to commit “acts harmful to the enemy.”[38] This would include using the hospital as a military barracks, as JIAT alleged the Houthis were doing. Nonetheless, as JIAT acknowledged, before a military force can attack a hospital used by belligerent forces for military purposes, the attacking force first must issue a warning about this misuse and set a reasonable time limit for it to end, and attack only after such a warning has gone unheeded.[39]

JIAT did not identify which states’ forces participated in the attack, but acknowledged the coalition intended to target the location of the hospital in Haydan. An investigation should seek to determine the basis for concluding that the Houthis were using the hospital. An unlawful attack, including by failing to provide the hospital adequate warning, should be criminally investigated for possible war crimes and to provide redress to civilian victims.

The coalition has repeatedly hit hospitals, including MSF-supported facilities, in Yemen. In two additional coalition attacks MSF investigated, the organization found: “Beyond the immediate loss of life and destruction … the attacks led to a suspension of activities that left an already very vulnerable population without access to healthcare.[40]

After JIAT released its findings on an August 2016 attack on an MSF-supported hospital in Abs, Hajjah, MSF stated: “This public declaration does not reflect the conversations MSF had in Saudi Arabia with the JIAT and military forces after the attack.” JIAT found the coalition targeted a Houthi vehicle next to the building; MSF said the car was already inside the hospital when bombed, carrying at least one wounded patient.[41] JIAT referred to seven people killed and another 13 wounded in the attack, appearing to source these numbers to MSF; MSF found the attack killed 19 people, including one MSF hospital worker, and wounded another 24. JIAT claimed the building had “no signs” of being a hospital; MSF said the hospital had a large logo on its roof and the organization had shared the hospital’s coordinates with the coalition at least every three months since July 2015, including five days before the attack. MSF pulled out of six hospitals in the Houthi-controlled north of the country after the attack. JIAT concluded attacking the hospital was an “unintentional error.” MSF responded: “We do not consider this incident an ‘error’, but a consequence of conducting hostilities with disregard for the protected nature of hospitals and civilian structures.”[42]

In June 2018, the coalition again hit an MSF-supported facility, this time a cholera treatment center, and again attempted to shift blame to MSF, including sending a letter from a low-level MSF employee to the US Congress in an attempt to justify the attack. As in past attacks, MSF quickly made clear, including providing relevant photos and documentation, that the roof of the facility had been clearly marked and it had repeatedly shared the facility’s coordinates with the coalition, which the coalition had acknowledged receiving in writing.[43]

May 13, 2015, Abs Prison, Hajjah

JIAT reported that the coalition had attacked two weapons depots in Abs, Hajjah governorate on May 13, 2015, each with a laser-guided bomb. JIAT concluded the nearby prison building was not affected and the coalition complied with international law.[44]

JIAT did not adequately investigate possible civilian harm in the attack, given its conclusion that the prison building was “neither targeted nor affected, at all.” Human Rights Watch visited the site of the attack in July 2015 and interviewed witnesses. One bomb hit the prison’s mosque, at the corner of the compound, collapsing the structure. Thirty-three men convicted of petty crimes were incarcerated in the prison at the time; among those killed were 17 prisoners, a prison guard, and two people in a shop near the prison, according to a local medic. A second bomb hit a nearby home minutes later. The strikes killed at least 25 civilians, including one woman and three children, and wounded at least 18.[45]

Ordinary prisons are civilian objects that may not be targeted unless they are being used for military purposes. Human Rights Watch was not able to determine the intended target of the attack; although one man said he had visited the prison every day to provide food to the inmates and that he not seen any military activity at the prison, such as weapons stored inside or nearby, or Houthi or allied military personnel. Human Rights Watch discovered the chassis and parts of what appeared to be two military jeeps among the dilapidated buildings but found no other signs that the area had been used for military purposes, or that people had recently lived in the buildings. Had the Houthis been using the prison or nearby areas to store weapons, these sites would be legitimate military objectives, though any attack would need to be proportionate. JIAT did not provide evidence to support a claim that the weapons depots were located near the prison.

Coalition forces did not appear to take adequate precautions in the attack, and the attack may have been unlawfully indiscriminate or disproportionate. JIAT did not identify which states’ forces participated in the attack. The attack should be criminally investigated for possible war crimes and to provide redress to civilian victims.

January 24-25, 2016, al-Nahdah neighborhood, Sanaa

JIAT concluded that the coalition complied with international law during airstrikes in Sanaa in late January 2017.[46] According to JIAT, the coalition had intelligence indicating Houthi leaders gathered in a house that thus “lost its legal protection and became a military objective of high value.” JIAT did not provide further evidence or information to support this claim.[47] In the immediate aftermath of the attack, then-coalition spokesperson Assiri denied claims the airstrike targeted a home, telling CNN: “We do not target homes. We are looking for Scud missiles. We always confirm, we do not attack residential sites. We attack storage [facilities].”[48]

JIAT did not acknowledge any civilian harm as a result of the attack, claiming that, after investigation and reviewing aerial footage, damage to the house targeted “did not exceed 30 percent,” and neighboring houses were “not damaged.” Human Rights Watch visited the site and photographed the remains of the three-story house hit—the photographs show the targeted house was completely destroyed and the neighboring building seriously damaged.[49]

JIAT did not identify which states’ forces participated in the attack, but said the coalition bombed the house “with high precision.” Family members of Judge Yahya Muhammad Rubaid, who owned the home, told Human Rights Watch the strike killed Judge Rubaid, his wife, one of his sons, and two of his daughters-in-law, one of whom was six months pregnant. On the day Human Rights Watch visited the home, Houthi fighters were present at a nearby hotel, about 120 meters away from the house.[50] If Houthi leaders were present in the home, the strike may have complied with the laws of war. If not, the coalition appears to have failed to comply with requirements regarding precaution in attack and carried out an unlawfully indiscriminate attack. JIAT did not identify which states’ forces participated in the attack. Those involved should be criminally investigated and civilian victims provided redress.

February 27, 2016, Nihm Market, Sanaa

After investigating a February 27, 2016 airstrike in Nihm, JIAT, which offered no details on the evidence examined or sources consulted, concluded that a coalition aircraft providing back-up to local Yemeni forces struck two Houthi “vehicles full of personnel, ammunition and weapons” and that the vehicles were near “a small natives’ market adjacent to a [sic] small buildings and tents.” JIAT found that the coalition complied with the laws of war, as only seven people were at the site, “deployed in an uninhabited desert area” under Houthi control.[51] Human Rights Watch documented the same attack and came to different conclusions after interviewing three local residents, including a local sheikh who arrived at the site 30 minutes after the strike, and a man who said the airstrike killed three of his cousins, two friends, and five others.[52] The local residents said the vehicles hit in the first strike were carrying civilians. Human Rights Watch found that the first strike hit the cars, which were in the middle of a small, crowded local market, killing at least 10 civilians, including one woman and four children, and wounding at least four more. The second strike landed 150 meters away in a graveyard between five and 10 minutes later, causing no injuries.[53]

The apparently unlawful attack should be criminally investigated for possible war crimes and to provide redress to civilian victims.

JIAT’s Improper Application of International Law

The current fighting in Yemen is considered a non-international armed conflict under the laws of war because it is a conflict between states and a non-state armed group, the Houthis. Applicable law includes Common Article 3 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, Additional Protocol (II) to the Geneva Conventions of 1977, and customary international humanitarian law.[54]

The Joint Incidents Assessment Team’s (JIAT) publicly released findings often appear to conclude that a coalition airstrike was lawful solely because the coalition had identified a legitimate military target, but without providing sufficient details for others to verify this information. JIAT’s public analyses also do not appear to consider whether an attack was unlawfully disproportionate, that is, whether the anticipated harm to civilians from the attack was greater than the anticipated military advantage, or if the coalition took adequate precautions before carrying out an attack. In addition to the six strikes described below, the United Nations Panel of Experts reexamined four strikes it had previously investigated that were taken up by JIAT, and found that, contrary to JIAT’s conclusions, “evidence still strongly demonstrates that the … coalition violated IHL in those incidents.”[55]

July 12, 2015 and February 3, 2016, Cement Factory, Amran

JIAT reported that the coalition did not violate the laws of war in two reported attacks on a cement factory in Amran governorate. It said the coalition bombed the factory on July 12, 2015 after receiving information that Houthi-Saleh forces were using it to support the war effort. The coalition again bombed the factory compound on February 3, 2016 after receiving information Houthi-Saleh forces had gathered in one of the buildings, JIAT said. JIAT did, however, recommend the coalition pay some form of redress to civilian victims of the February 3 attack.[56]

In both attacks, JIAT claimed the coalition had identified, targeted, and struck a military target: in one case a Houthi gathering, in the other a factory used to support the war effort. Human Rights Watch visited the factory and witnesses said that two or three Houthi fighters had used nearby huts belonging to the factory.[57] While Houthi fighters and facilities used to produce or store goods intended for military use are lawful military targets, JIAT did not provide evidence to support their claims, nor details regarding how Houthi-Saleh forces were allegedly using the factory to support the war effort.

In addition, a military target present does not necessarily make an attack legal; it must also not cause disproportionate civilian loss. JIAT did not fully engage in an inquiry regarding civilian harm. JIAT acknowledged that two buildings and nearby cars were damaged in the February 3 attack, but provided no information as to the extent of the civilian property damage on July 12 and did not acknowledge any civilian casualties for either attack.

Human Rights Watch found that in the July 12 strike at least five bombs hit different parts of the factory. The factory had reopened a few days previously and 12 workers were wounded. The February 3 airstrike hit the factory’s main entrance, located on a busy street, killing 15 civilians, including seven workers and two children, and wounding 49. One of the factory employees reported seeing four cars, two shops, a pharmacy, a café, and a call center on fire.[58]

Deliberate or indiscriminate attacks on civilians and civilian structures are serious violations of the laws of war. JIAT did not identify which states’ forces participated in the attack but acknowledged the coalition intended to target the Amran Facility on July 12, 2015 and February 3, 2016. Those involved should be criminally investigated and civilian victims of both strikes provided redress.[59]

October 29, 2016, al-Zaydiyah Prison, Hodeida

JIAT reported that the coalition had intelligence indicating Houthi leaders, accompanied by foreign experts, were using al-Zaydiyah security administration building in Hodeida for military purposes when it was attacked in October 2016. JIAT said the coalition targeted the building in “using precision-guided bombs” as the building “lost its legal protection.”[60]

Human Rights Watch also investigated the attack, visiting the site and interviewing witnesses.[61] Three wards at the prison held about 100 prisoners at the time of the coalition attack, according to a guard and former detainee. The airstrikes hit the roof of the administration building; one of two cells holding male suspects; and the women’s cell, a separate building used to house security detainees. Former detainees described running to their cell doors after the first strike, only to find they were locked in the ward as more bombs fell. The strike killed at least 63 people, including Houthi personnel and civilians, and wounded 67 more. Many of the casualties were criminal and security detainees held at the facility without charge, including at least two children.

A source said the Houthis used the facility as a base for military operations, and the Houthi-controlled Foreign Affairs Ministry said members of popular committees, which would be subject to attack, oversaw some of the detainees.[62] By deploying military forces at a civilian detention facility, the Houthis failed to take all feasible precautions to minimize the risk to the detainees.

JIAT concluded the coalition complied with international law as the coalition had identified a legitimate military target. While any combatants and military equipment at the facility would be legitimate targets, the civilian detainees and detained fighters, in the power of an adverse party and thus hors de combat, would not be subject to attack.[63] If, as JIAT claimed, the coalition had intelligence regarding the use of the complex, the coalition may have known there was a large presence of persons protected from attack in the detention facility: six former detainees told Human Rights Watch they had been held at the facility between several months and more than a year on suspicion of common crimes, including one 15-year-old boy who was severely burned in the airstrike. The facility was widely known in the area as a detention center.

Without providing more or verifiable information on the Houthi leaders and foreign experts allegedly present, the coalition airstrike on the detention facility appears to be an unlawfully disproportionate attack. JIAT did not identify which states’ forces participated in the attack but acknowledged that the coalition intended to target the facility, using laser-guided bombs to do so. Those involved should be criminally investigated and civilian victims provided redress.

January 5, 2016, Dar al-Noor Rehabilitation Center for the Blind, Sanaa

JIAT concluded the coalition had received intelligence that the Houthis had seized Dar al-Noor Rehabilitation Center for the Blind, evacuated those using the building, and begun using it as a military headquarters. JIAT found that the building “thus lost legal protection, becoming a legitimate military target.”[64]

While witnesses told Human Rights Watch, which visited the compound and conducted interviews, that the Houthis had set up an office in the compound, installed guards at the entrance, and regularly had men and vehicles in the compound, they also described the civilian harm that resulted from the strike. JIAT did not acknowledge any civilian harm. The Houthis unlawfully placed the school for blind students at grave risk by basing militia forces in the facility’s compound, but the presence of Houthi fighters did not obviate the coalition’s obligation to consider the potential harm to civilians.

Human Rights Watch found that a three-story building in the three-building compound housed the al-Noor Center for the Care and Rehabilitation of the Blind, which served 250 students, mostly children, who had visual disabilities. A second three-story building was used as the sleeping quarters for 130 students. The third building, where the militia members stayed, included a kindergarten on the second floor. The buildings are about 20 meters apart. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch a single bomb hit the roof of the building that housed the students’ sleeping quarters and penetrated it but did not explode.[65] The strike wounded four civilians and a Houthi guard and damaged the capital’s only center for people with visual disabilities. Had the bomb detonated, damage to the buildings and civilian casualties would have been far greater. JIAT did not identify which states’ forces participated in the attack, but acknowledged the coalition aimed to bomb the building and did so with an “accurate guided bomb.”[66]

December 29, 2015, Coca-Cola Factory, Sanaa

JIAT concluded that the coalition had intelligence indicating the Houthis were using a Coca-Cola factory in Sanaa to store missiles, and that the building was located north of the city, from where the Houthis had launched several missiles toward Saudi Arabia. JIAT said the building was a legitimate military target, and that a December 29, 2015 strike complied with international law.[67]

JIAT did not appear to engage in an analysis of the civilian harm caused by the strike. Human Rights Watch documented the attack and visited the factory on March 31, 2016.[68] According to employees, the bombs hit the factory over several minutes, wounding five employees. Many of the employees had left the building about 10 minutes before the first bomb hit, according to the plant manager. The strikes destroyed raw materials used to produce soft drinks, a generator, and both the glass and plastic bottling lines. Human Rights Watch found no evidence that the factory produced anything other than beverages.

Broken bricks, fallen metal roof beams, and other building debris covered the site. Researchers found broken bottles and large amounts of spilled sugar in the area where workers said they previously stored raw materials.

If the Houthis had been using the factory to store missiles, the strike would likely be in compliance with the laws of war. JIAT did not provide enough information to allow for independent verification of the claim. The al-Dailami Air Force Base is located about 700 meters from the factory, which coalition forces had repeatedly struck, including during the nine months before the factory was struck, according to workers.

August 30, 2015, al-Sham Water Bottling Factory, Hajjah

JIAT acknowledged the coalition carried out an airstrike on al-Sham Water Bottling Factory in Hajjah on August 30, 2015.[69] In its statement, JIAT said that “due to weather conditions” and “some clouds” the laser-guided bomb missed the target. JIAT concluded it was an “unintentional error.” Right after the strike, then-coalition spokesman Gen. Ahmad al-Assiri had told Reuters: “We got very accurate information about this position and attacked it. It is not a bottling factory.”[70] Assiri told CNN, “There is no factory, we attacked a military camp in Hajjah where they train mercenaries to send them to kill our soldiers.”[71]

JIAT recommended the coalition apologize and provide assistance to victims but did not provide a full accounting of the civilian harm caused, stating the coalition hit the factory, causing “destruction … some deaths and injuries.” Human Rights Watch interviewed witnesses to the attack and found the airstrike killed 14 workers, including three boys, and wounded 11 more.[72] Many of the dead and wounded, as well as the owner of the factory, were from the same family. JIAT did not identify which states’ forces participated in the attack, nor who would be responsible for paying redress. Those involved should be criminally investigated for possible war crimes and civilian victims provided redress.[73]

Shielding States from Responsibility for Violations

The Joint Incidents Assessment Team (JIAT) reporting on alleged violations of the laws of war has not included information on the various armed forces involved in specific airstrikes, effectively shielding coalition states and other parties to the conflict that may have been involved in violations, and individuals who may have committed war crimes. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, JIAT has only released information on Yemen armed forces’ participation in attacks JIAT investigated – asserting that faulty intelligence from government of Yemen armed forces led to the attack on a funeral in Sanaa in October 2016.

JIAT’s failure to identify the forces that participated in attacks, including attacks in which JIAT recommended the coalition provide some form of reparations or pursue further action, paired with the lack of transparency of coalition members, make it incredibly difficult for independent observers or Yemeni victims of unlawful attacks to determine whether JIAT’s recommendations have been implemented, or to follow up with JIAT or particular coalition members regarding compensation or accountability.[74] These difficulties have not been limited to human rights investigators but apparently extend to coalition allies. In June 2017, then-United States Secretary of State Rex Tillerson told the US Congress:

The Saudi military … informed us they have changed procedures in line with the recommendations of … [JIAT], though we have not yet been able to verify this. We do not have definitive data at this point to assess whether the Royal Saudi Air Force made improvements in its targeting capabilities.[75]

September 10, 2016, Beit Sahdan Village, Arhab

A year after the attack, JIAT released a statement concluding that a September 10, 2016 airstrike on Beit Sahdan village was an “unintended mistake.”[76] Soon after the attack the coalition spokesperson, Gen. Ahmad al-Assiri, had said that, “All operations in the area were targeting Houthi positions and members.”[77]

According to JIAT, the Houthis launched a ballistic missile from Arhab district toward Saudi territory that morning and a coalition air formation mistook a group of people and two trucks near a drill being used to build a village water well for the ballistic missile launcher. By referring to the attack as an “unintended mistake,” JIAT effectively absolved coalition forces of wrongdoing. Even if the coalition mistook the drill for a missile launcher in the first strike, it does not explain why coalition aircraft returned to the site and bombed it many more times over the course of the morning.

Human Rights Watch also documented the attack, interviewing witnesses who said that before dawn coalition aircraft struck the site of a worker’s shelter near the water drilling rig.[78] After several dozen villagers came to remove the bodies of those killed, coalition planes returned and bombed the area at least 12 more times, about 15 minutes apart, witnesses said, striking the area in widening circles as those gathered attempted to escape. Human Rights Watch visited the site on November 10 and examined the rubble of the workers’ shelter, as well as the burned wreckage of a fuel tanker truck. There were at least 11 bomb craters or impact sites in the immediate area. Over the course of the morning, the multiple coalition strikes killed at least 31 civilians and wounded 42 more, according to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).[79]

JIAT recommended the coalition provide “appropriate humanitarian assistance,” but did not acknowledge the extent of civilian harm. The bombing destroyed the well, which residents had pooled their money together to build in order to supply drinking water to their village. It was near completion. Both people in the village and the company building the well told Human Rights Watch that work had been ongoing on the well for weeks.

The coalition may have violated the laws of war by failing to take all feasible precautions to identify the water drilling well prior to attacking the object, which JIAT said the coalition mistook as a missile launcher. Indiscriminate attacks on civilians and civilian objects are serious violations of the laws of war.

Human Rights Watch identified a piece of a US-made munition with markings indicating it was manufactured by Raytheon in October 2015. Human Rights Watch has identified remnants of US-supplied weapons at the site of two dozen apparently unlawful coalition attacks. Human Rights Watch has identified four attacks in which the coalition used a weapon made by Raytheon.[80]

Neither JIAT nor the coalition provided further information on which state forces participated in the attack. Those involved should be criminally investigated and civilian victims provided redress. Such an investigation should examine the coalition’s continued attacks after civilians had gathered to remove the dead and wounded.[81]

July 24, 2015, Residential Complex, Mokha

After investigating a 2015 airstrike in Mokha, JIAT–without providing any explanation of its methodology–found the coalition had intelligence that four military targets in the area were struck on July 24, 2015, including coastal defense missiles, but that a residential complex was “partly affected by unintentional bombing, based on inaccurate intelligence information.” JIAT did not conclude how many civilians were harmed in the attack, but recommended the coalition provide compensation to victims “after they submit their official and documented claims to the Reparations Committee.”[82]

Human Rights Watch visited the area a day-and-a-half after the attack. Researchers examined the damage, interviewed workers and residents at the compounds, and visited three hospitals that received victims. Contrary to JIAT’s conclusion that the complex was “partly affected by unintentional bombing,” Human Rights Watch found that six of nine bombs had hit the main residential compound, completely destroying large sections of it.[83] A seventh bomb hit another compound for short-term workers. The two residential compounds housed at least 200 families and the attack killed at least 65 civilians, including 10 children, and wounded dozens more. Human Rights Watch found no evidence of a military objective at the scene of the attack.

While JIAT claims the residential complex was affected by “unintentional bombing,” it went on to say the attack was based on inaccurate intelligence information that made the complex the target of the attack. Neither JIAT nor the coalition provided further information on which state forces participated in the attack. Those involved should be criminally investigated for possible war crimes and civilian victims provided redress.[84]

October 8, 2016, Great Hall Funeral Ceremony, Sanaa

After the October 8 bombing of a funeral hall in Sanaa, coalition sources initially denied responsibility for the attack. Immediately after, then-coalition spokesperson Gen. Ahmad al-Assiri wrote in a text message to the New York Times that it was possible there were other causes for the blasts. Assiri later confirmed a report by Saudi-owned Al-Arabiya news network that the coalition had not carried out strikes near the hall.[85] Reuters quoted an unnamed coalition source who said he confirmed with the coalition’s air force command that:

Absolutely no such operation took place at that target. The coalition is aware of such reports and is certain that it is possible that other causes of bombing are to be considered. The coalition has in the past avoided such gatherings and [they have] never been a subject of targets.[86]

The following day the coalition announced it would investigate the incident with support from the US.[87] JIAT “examined all related documents, and assessed evidence, including the rules of engagement (ROEs) and the testimonies of concerned personnel and those involved in the incident,” ultimately concluding that a party to the conflict affiliated with Yemeni President Hadi passed incorrect intelligence to a coalition aircraft and “insisted that the [Great Hall] be targeted immediately.” JIAT went on to note that the Yemen air operations center directed the aircraft to carry out the mission “without obtaining approval from the Coalition command ... and without following the Coalition command’s precautionary measures to ensure that the location is not a civilian one that may not be targeted.” JIAT recommended appropriate action be taken against officials responsible, compensation be offered to the victims, and the coalition’s rules of engagement reviewed. A week later, the coalition accepted the results of JIAT’s investigations and announced it had begun to implement the recommendations.[88] After the attack, the Yemeni government dismissed the Yemeni officers involved in the incident and referred those to the military court, according to the Yemeni National Commission to Investigate Alleged Human Rights Violations.[89]

Neither JIAT nor the coalition provided further information on which state forces participated in the attack on the Great Hall. Human Rights Watch interviewed 14 witnesses to the attack and two men who arrived at the scene immediately after the airstrike to help with rescue efforts, among other sources, and reviewed video and photos of the strike site and weapons remnants. Regardless of the faulty intelligence, coalition forces, both in the Yemen air operations center and in Riyadh, either knew or should have known that any attack on the hall would result in massive civilian casualties. The date and place of the funeral ceremony was publicly available, and the hall would have been known to be crowded with hundreds of civilians at the time of the attack. Human Rights Watch identified the munition used as a US-manufactured air-dropped GBU-12 Paveway II 500-pound laser-guided bomb.[90]

Immediately following the strike, the US National Security Council spokesperson said the US was “deeply disturbed” by the incident, “which, if confirmed, would continue the troubling series of attacks striking Yemeni civilians.” The US “initiated an immediate review of [its] already significantly reduced support” to the coalition and was “prepared to adjust our support.”[91]

The strike was an unlawfully indiscriminate or disproportionate attack on civilians and civilian objects in violation of the laws of war. Those involved should be criminally investigated for war crimes and civilian victims provided redress.[92]

August 25, 2017, Faj Attan Homes, Sanaa

JIAT said the coalition targeted a communications control system used for military purposes located in Faj Attan, Sanaa on August 25, 2017. According to JIAT, three bombs hit the intended target, whereas a fourth, due to a technical error—they claimed the guidance system was not responding— unintentionally hit a nearby building.[93] In an initial statement, the coalition said the civilian casualties were the result of a technical error and that it had targeted a “legitimate military objective” – a command-and-control center that Houthi-Saleh forces built “with the sole purpose of using the surrounding areas as well as its civilians as shields to protect it.”[94] JIAT concluded the coalition complied with international humanitarian law, as the incident was “unintentional.”

While it is possible for precision-guided munitions to malfunction, resulting in a different area being impacted, the coalition has often not provided sufficient technical detail to allow an independent determination as to whether these strikes were in fact the result of a technical error. JIAT did not report how many civilians the attack killed or wounded, merely noting the strike “caus[ed] civilian casualties and injuries and physical damage to civilian objects.”

Human Rights Watch documented the strike in Faj Attan. Witnesses reported four airstrikes, including three on the Faj Attan mountains and one on apartment buildings in a densely populated neighborhood, which killed at least 16 civilians and wounded 17.[95] The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) called the attack “outrageous” and said there was no apparent military target in the area.[96] While JIAT and the coalition made numerous statements on the attack, and JIAT recommended the coalition consider providing assistance to the families, the coalition at no point provided information on which states’ forces participated in the attack. The apparently unlawful attack should be criminally investigated for possible war crimes and to provide redress to civilian victims.[97]

Using the Coalition to Evade Legal Liability

The coalition has not been transparent in its operations, notably with regard to which states’ armed forces were involved in airstrikes, who is in the coalition’s command chain, and who has target engagement authority.

States have an international legal obligation to investigate alleged laws-of-war violations by their forces. Coalition members have instead sought to evade this obligation by hiding behind the coalition and not providing information about their role in possibly unlawful airstrikes. Coalition members are thus implicated both for their role in the violations themselves and for failing to investigate and prosecute wrongdoing as appropriate.

Consistent with Common Article 1 of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, states are obligated to abide by the laws of war and “ensure respect” for the laws of war by using their influence, to the degree possible, to stop all laws-of-war violations.[98] They are responsible for violations by their own armed forces, as well as those committed by forces acting under their instructions, directions, or control. International law recognizes that a state that “aids or assists another state in the commission of an internationally wrongful” act will be responsible for that assistance, provided the state had knowledge of the circumstances and the act would be wrongful if committed by the state.[99]

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross’s (ICRC) 2016 Commentary on Common Article 1, states whose forces participate in military operations with other forces cannot “evade their obligations by placing their contingents at the disposal of … an ad hoc coalition.”[100] In July 2017, the United Nations Security Council Panel of Experts on Yemen expressed concern that coalition members “seek to hide behind ‘the entity’ of the Coalition to shield themselves from state responsibility for violations committed by their forces.… Attempts to ‘divert’ responsibility in this manner from individual States to the … coalition may contribute to further violations occurring with impunity.”[101]

The Coalition

The military coalition supporting the Yemeni government consisted of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Sudan when the coalition launched Operation Decisive Storm in March 2015. Qatar withdrew in June 2017, during the Gulf Crisis.[102] In late 2017 and early 2018, meetings of the coalition included representatives from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Jordan, Bahrain, Sudan, Egypt, Kuwait, and Morocco, as well as Pakistan, Djibouti, Senegal, Malaysia, and Yemen, according to the Saudi state news agency.[103] While incomplete, coalition officials’ statements, published by relevant countries’ defense ministry websites and released by official state news agencies, provide some insight into which countries’ forces and which individuals play a role in the broader coalition structure, in military operations, and in the command chain.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia leads the coalition. A 2017 UN expert panel report found that: “At the operational level … coalition military activities are conducted under the control of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.… Air operations in Yemen are under the operational control of a joint headquarters led by Saudi Arabia and based in Riyadh, with a targeting and control cell for the targeting and tasking processes.”[104]

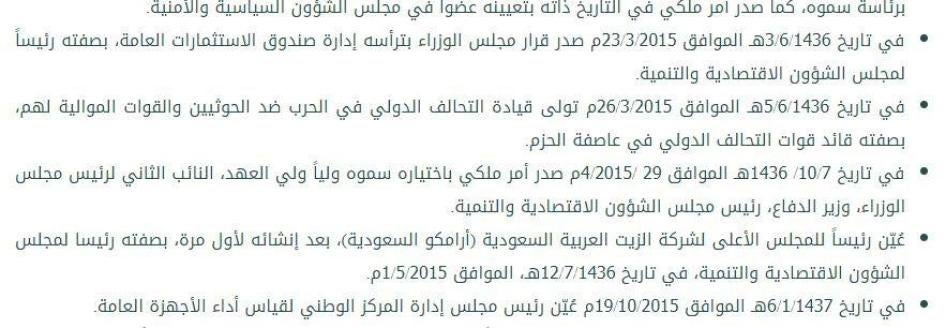

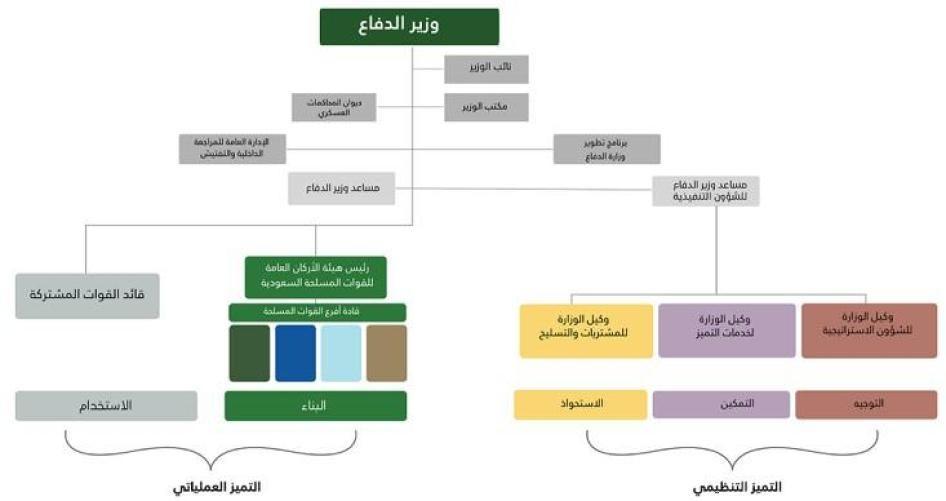

Mohammed bin Salman serves as Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, deputy prime minister, and minister of defense.[105] As defense minister, he oversees all Saudi military forces.[106] In May 2018, Neil Patrick, a Gulf analyst, wrote, “The top brass all report directly to the defense minister, the crown prince himself. At present, there is no deputy defense minister and just one relatively old assistant minister.”[107]

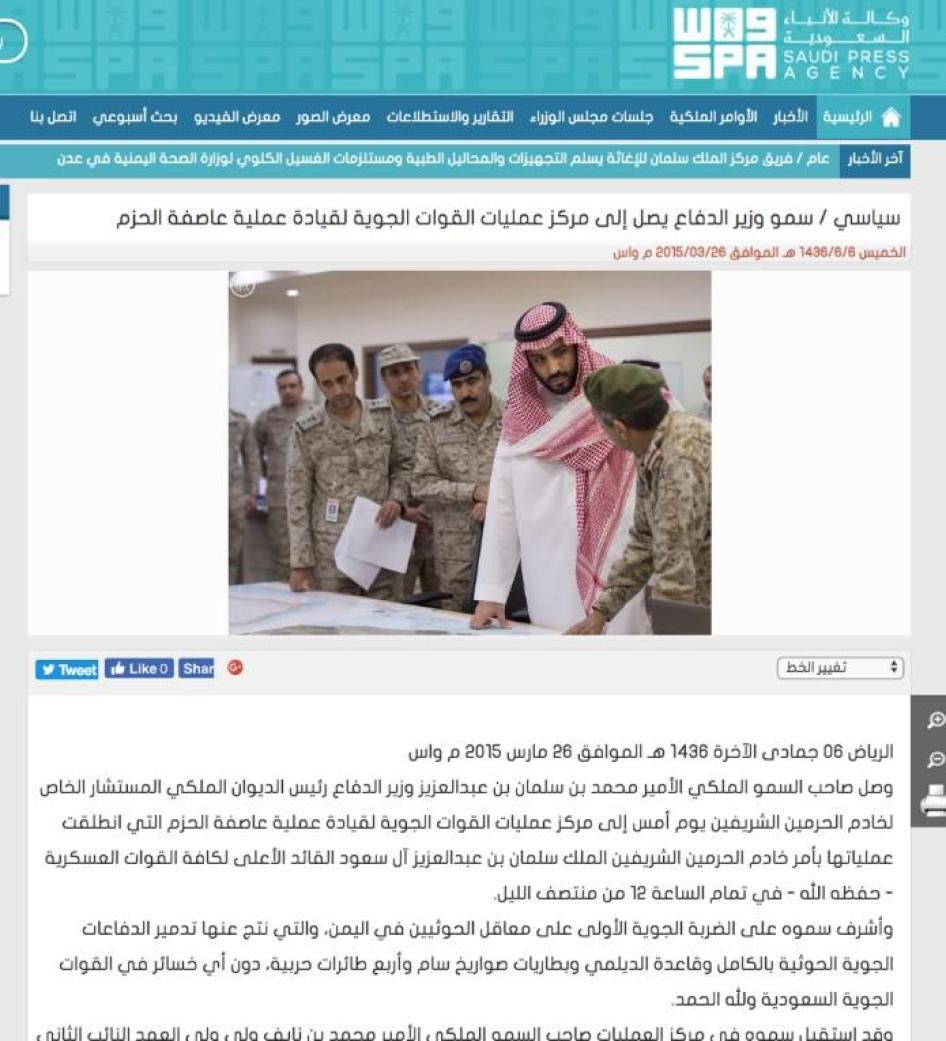

Mohammed bin Salman has served as the commander of the international coalition in the “Decisive Storm” operation—the coalition operating in Yemen—since March 26, 2015, according to the Defense Ministry website.[108] On March 26, the Saudi Press Agency reported that bin Salman had gone to the “Air Force Operations Center to lead the Decisive Storm operations.” Bin Salman, according to the official state news agency, “oversaw the first airstrike” and “briefed [other senior officials] about military plans and operations immediately before the Saudi planes launched.”[109] Other Gulf outlets published photos and videos of the crown prince in the command center.[110]