Summary

Every day I fear for my safety living in this country because of my sexual orientation. I am alive but if anyone ever find out and wanted to find out, they can kill me …I am an easy target for anything.

—Peter, Dominica, February 21, 2017

The majority believes: “absolutely, kill them before they reproduce.” The average man would think to kill, they probably won’t do it because it is murder.

—Michaela, Grenada, February 21, 2017

The main fear is the fear of disclosure. The fear of being found out. They would lose the favor of their family. They may be displaced in church. People would lose respect for them in their work spaces. They have a whole lot to lose.

—Stella, retired nurse from Antigua, February 9, 2017

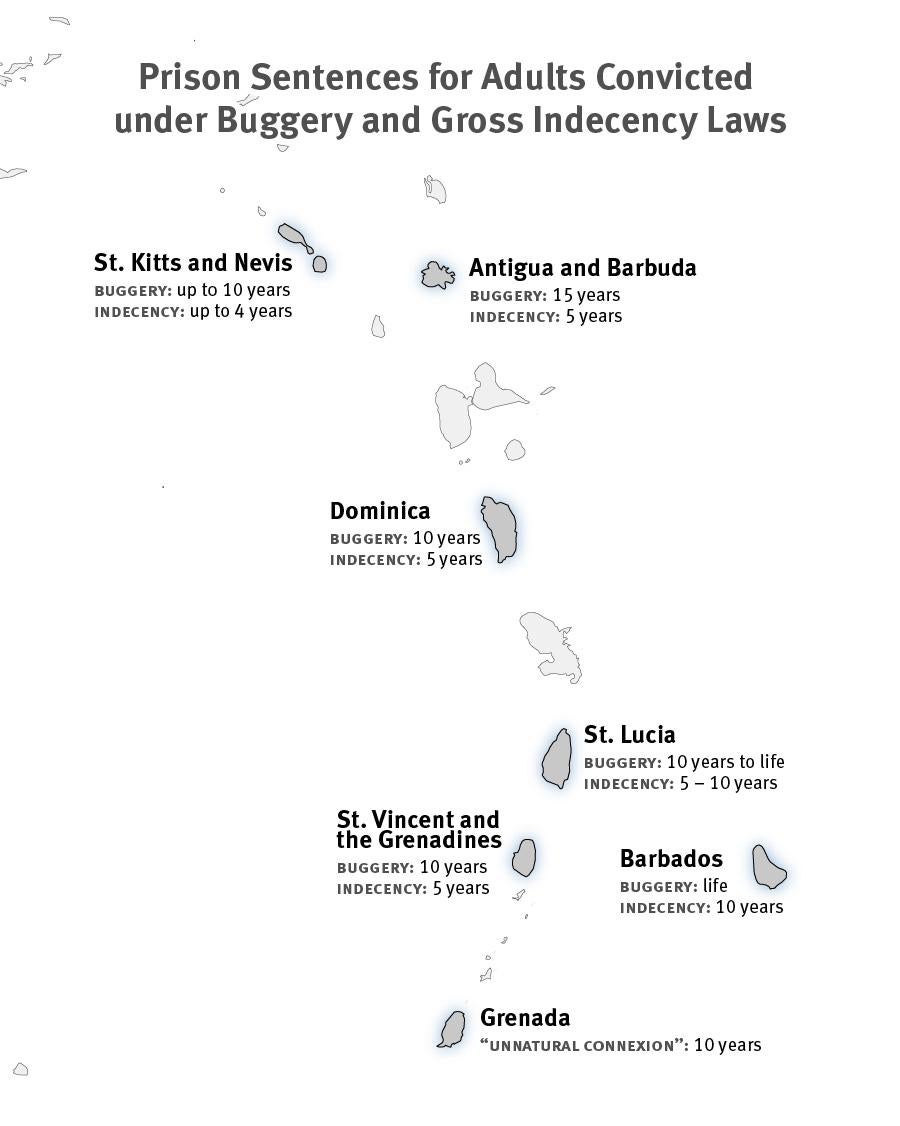

This report focuses on the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in small island states of the Eastern Caribbean. It demonstrates, through individual testimony, how existing discriminatory legislation negatively impacts LGBT populations, making them ready victims of discrimination, violence, and abuse. The report includes seven Eastern Caribbean countries: Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Populations in these countries range from 54,000 in St. Kitts and Nevis to 285,000 in Barbados.

All seven countries have versions of buggery and gross indecency laws, relics of British colonialism, that prohibit same-sex conduct between consenting persons. The laws have broad latitude, are vaguely worded, and serve to legitimize discrimination and hostility towards LGBT people in the Eastern Caribbean. They are rarely enforced by way of criminal prosecutions but all share one common trait: by singling out, in a discriminatory manner, a vulnerable social group they give social and legal sanction for discrimination, violence, stigma, and prejudice against LGBT individuals.

The English-speaking Caribbean is an outlier in the region. The fact that buggery and gross indecency laws are still on the books there is in stark contrast with recent developments in Latin America where states including Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, and Uruguay have been progressive in enacting non-discrimination policies and anti-bias legislation. Latin American countries, including Argentina, Brazil, and Chile have taken an international lead advocating for the rights of LGBT people at the United Nations. Several, including Costa Rica, Mexico, and Uruguay, are members of the Core Group of LGBT friendly states at the United Nations and of the Equal Rights Coalition, a group currently composed of 33 states committed to the rights of LGBT people.

All countries featured in this report are members of the Organization of American States and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM). Except for Barbados, all also belong to the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). CARICOM and the OECS seek regional integration through economic cooperation and shared administrative functions.

Activists and civil society organizations have been at the forefront of efforts to advance the rights of LGBT people in the region, including by challenging discriminatory laws and exposing human rights violations. In some countries, activists have participated in LGBT awareness training for law enforcement agents. In others, civil society groups have challenged discriminatory legislation including by petitioning the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). Regionally groups have participated in strategic litigation initiatives.

In the Eastern Caribbean, family and church are cornerstones of social life. The fear of harassment, rejection, stigmatization, and even physical violence begins in the home and translates to key social spaces, including church and school. Interviewees said that they were afraid to come out in their typically close-knit communities, where social networks are tight and information travels fast. They also face the risk of being ostracized by their own families.

All interviewees described having been harassed by family at some point in their lives because they are LGBT or merely suspected to be. Fear of isolation has led many LGBT people to live in the closet, and prompted some to enter heterosexual marriages. Some report being thrown out of their home or cut off from financial support. Many have experienced homelessness and life at the margins of society, rendering them vulnerable to violence and ill health.

The church plays an especially important role in social welfare, communal life, socialization, and in shaping social attitudes and moral ethics. Many interviewees said that family rejection was often couched in moralistic terms, echoed in local church rhetoric.

Discrimination and stigma against LGBT people seeps into everyday activities, whether it be availing oneself of services such as health care, school, or riding a bus, or social activities such as going to the movies or shopping. Ordinary social encounters can be menacing. Some LGBT individuals described changing their lifestyle and behaviors to avoid contact with hostile members of their family, church, or community, while others described having to endure physical attacks. Some people opted to socialize only with a few trusted friends in the safety of their homes.

Verbal abuse and harassment can quickly escalate into physical assault. Testimonies show that LGBT people are vulnerable to abuse and attacks by neighbors and acquaintances. Interviewees described being stabbed, struck, pelted with bottles and bricks, beaten, slapped, choked and, in one instance, chased with a harpoon. Transwomen are particularly vulnerable to attacks by their partners, as well as strangers.

Discriminatory laws, including buggery and gross indecency laws, inhibit LGBT people from reporting abuse, and strengthen the hand of abusers. Many of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch explained that they did not trust the police enough to report incidents of abuse against them. Those that did described negative experiences, including inefficiency, inaction, and antipathy. The normalization of violence against LGBT people results in the continued marginalization and exclusion of LGBT people from the most basic protections of the law.

Verbal and physical abuse can also have serious long-term consequences by instilling in LGBT people feelings of fear, shame, and isolation, and lowering their self-esteem. Interviewees said they often experienced depression, suicidal thoughts, and self-inflicted harm. Support systems that exist in an increasing number of countries where same sex relations are not or are no longer criminalized do not exist in these seven countries. As a result, LGBT people tend to fall through the cracks, as neither government agencies nor civil society organizations have developed services that can fully address their health or psychosocial needs.

The difficult and extreme nature of the experiences endured by LGBT individuals has led many to consider fleeing their countries. As one interviewee put it “when push came to shove” relocating became a desirable and sometimes the only alternative. One interviewee conveyed the general sentiment by stating: “I have to leave to be me.”

International law protects LGBT persons by prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. International human rights law establishes that matters of sexual orientation and gender identity, including consensual sexual relations, are protected under the rubric of the right to privacy and the right to be protected against arbitrary and unlawful interference with, or attacks on, one’s private and family life and one’s reputation or dignity. Criminalizing same-sex intimacy violates these international obligations.

Countries featured in this report have ratified international and regional treaties that require them to protect human rights without discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. The details of exactly which treaty each country has signed onto vary, and are included in the appendices.

Eliminating laws that discriminate based on sexual orientation is a human rights obligation. Living up to this obligation could go a long way toward freeing part of the Eastern Caribbean population from violence and fear, while affirming human rights and dignity.

Key Recommendations

To the Governments of Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines

- Repeal all laws that criminalize consensual sexual activity among persons of the same sex.

- Ensure that criminal laws and other legal provisions are not used to punish consensual sexual activity among persons of the same sex.

- Pass laws defining the crime of rape in a gender-neutral way so that non-consensual sex between men or between women is included in the definition and subject to equal punishment.

- Consistent with the principle of non-discrimination, ensure that an equal age of consent applies to both same-sex and different-sex sexual activity.

- Pass comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation that prohibits discrimination, including on grounds of gender identity and sexual orientation, and includes effective measures to identify, prevent, and respond to such discrimination.

- Introduce and implement a gender recognition procedure in accordance with international standards and good practices to allow people to change their legal gender on all documents through a process of self-declaration that is free of medical procedures or coercion. Such gender recognition procedure should ensure that changes to documents are made in a way that protects privacy and dignity.

- Enable LGBT people to undergo needs assessments for their health (including mental health) and develop programming to address those needs. Such assessments should be strictly voluntary, provide options for anonymity and other protections for participants’ identities, and be conducted in ways that respect the privacy and dignity of LGBT individuals.

- Conduct awareness-raising campaigns for the general public, journalists, and public officials, including law enforcement officials and medical professionals, that promote tolerance and respect for diversity, including gender expression, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

To the Offices of the Ombudsman

- Establish confidential means whereby LGBT individuals can report abuse, publicize how individuals can report abuse without fear of reprisal, and investigate all such reports.

- Develop plans and allocate adequate resources to ensure systematic documentation and monitoring of human rights violations of LGBT people, including through c0llection of accurate data on acts of violence and discrimination due to real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity.

- Act as a source of human rights information for the government and the public to raise awareness of the human rights impact of buggery and gross indecency laws.

To the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States

- Acknowledge the impact that current laws have on the lives of LGBT people in member states by denouncing and condemning the provisions criminalizing consensual sexual activity among adult people of the same sex, such as buggery laws and serious or gross indecency laws.

- Begin to address LGBT issues head on, in an open and constructive way, by encouraging member states to decriminalize same-sex sexual relationships, and in the meantime, to issue a de facto moratorium to prevent the application of existing laws that criminalize same-sex sexual relationships.

- Offer support to politicians and religious leaders in member states to engage with civil society organizations in the region to work on reviewing, updating, amending, and creating laws on social protection for LGBT vulnerable youth.

- Recognize the role of LGBT organizations as platforms for advancement of human rights in Member States by engaging in dialogue and consultation with them in areas of health, education, and employment protections for LGBT people.

To the Commonwealth Secretariat

- Consistent with the 1971 Singapore Declaration of Commonwealth Principles, which affirms “the liberty of the individual,” “equal rights for all citizens,” and “guarantees for personal freedom,” condemn and call for the removal of all remaining British colonial laws that criminalize consensual sexual activity among people of the same sex.

- Promote the decriminalization of consensual, homosexual conduct.

- Develop models for gender-neutral legislation on rape and sexual abuse and for the protection of children.

- Integrate issues of sexual orientation and gender identity into all human rights educational and training activities, including the Commonwealth Human Rights Training Programme for police.

Methodology

This report is based on field research conducted by Human Rights Watch over a four-week period in the countries of Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines in February 2017, as well as prior and subsequent desk-based research. Interviews took place in the capital cities of the islands: St. John’s, Bridgetown, Roseau, St. George’s, Castries, Kingstown, and Basetterre.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 41 self-identifying LGBT people between the ages of 17 and 53. The interviewees were identified primarily through the Eastern Caribbean Alliance (ECADE) and local LGBT organization networks. Most interviews were conducted individually and in English. Human Rights Watch conducted only one group interview with seven gay men in Kingstown, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. We spoke to people in a variety of settings, including their homes, bus stations, the LGBT group’s office in the capital city of each country, and the homes of their friends.

All persons interviewed provided verbal informed consent to participate and were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions. Interviewees have been given pseudonyms and in some cases other identifying information has been withheld to protect their privacy and safety. No one was compensated for their participation. In some cases, funds were provided to cover travel expenses. The interviewees were mostly economically disadvantaged young adults.

I. Background

National Legislation: Buggery and Gross Indecency Laws in Small Island States in the Eastern Caribbean

All seven states covered by this report criminalize same-sex intimacy between consenting persons. Most of the laws use the terms “buggery” or “gross indecency,” though some outlaw “unnatural connexion” or sodomy. For simplicity’s sake, this report uses “buggery laws” and “gross indecency laws” as shorthands for the laws in all seven jurisdictions.

The reasons for selecting the targeted countries are twofold. First, they are neighboring countries that influence one another and that, as part of regional systems such as CARICOM and OECS, share an overarching judicial review system. Second, as small island states, they are often overlooked.

Buggery and gross indecency laws are seldom enforced against consenting persons. And the specific legal provisions vary from country to country. But they share one common trait: they all give social and legal sanction for discrimination, violence, stigma, and prejudice against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals.

Buggery and gross indecency laws are a residue of British colonialism. They are vaguely worded and enacted with broad latitude. They help create a context in which hostility and violence directed against LGBT people is legitimized, operating as an effective tool to ostracize and single out a vulnerable sector of the population.

In the seven countries covered in this report there is no consistent definition of “buggery” or the penalties imposed. Antigua and Barbuda and Dominica define buggery as “anal intercourse by a male person with a male person or by a male person with a female person.”[1] Most countries, including Barbados, St. Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, leave it undefined, specifying only the prison terms to be imposed.[2] St. Kitts and Nevis criminalizes “sodomy and bestiality” and defines the term by referencing “the abominable crime of buggery, committed either with mankind or with any animal.”[3] Grenada has the most open-ended provision, criminalizing “unnatural connexion,” which is undefined and has been interpreted in past case law to include consensual anal intercourse between same-sex persons.[4] Barbados has the most severe punishment: life imprisonment.[5] Dominica grants courts the power to order that “the convicted person be admitted to a psychiatric hospital for treatment” and St. Kitts and Nevis allows courts to add “hard labor” in the final judicial decision.[6]

Buggery laws do not distinguish between consensual and non-consensual sex. And rape laws in four of the seven island nations featured in this report define rape narrowly as non-consensual penile-vaginal sex. This means that existing rape laws fail to protect people against non-consensual anal or oral sex. There is a gap in the law to protect people both male and female from forced sex, both anal and oral. This is sometimes used as flawed rationale to retain the “buggery laws.” For example, in 2016 Prime Minister Stuart of Barbados claimed that buggery laws are exclusively aimed at non-consensual sex. He said: “The law of buggery has to do with abuse, where A abuses B without his consent… I want you to just equate in your own mind, buggery with rape. Rape is the offence committed against in a heterosexual relationship and buggery is the offence committed in a same-sex relationship. At the kernel of both is the absence of consent and therefore a protesting party who wants to ensure that he or she gets justice through the courts.”[7] This is not the case. Buggery laws draw no distinction between consensual and non-consensual sex, and do not require lack of consent, as noted by Elwood Watts, principal Crown counsel in a buggery case in Barbados.[8]

Indeed, the buggery laws of all seven countries analyzed in this report are silent on consent, thus encroaching on the rights to non-discrimination and the right to privacy of individuals engaging in consensual same sex activity. Indeed, the broad wording of the laws and the way they are interpreted by police, courts, and the public means that consensual sex between members of the same sex is, according to the law, akin to rape.[9] What is needed is a gender-neutral rape law, and a repeal of the buggery laws.

The “gross indecency” provision was introduced in British Law in 1885 to cover all acts of sexual intimacy between men short of anal intercourse.[10] Gross indecency was not defined, but left to court interpretation. Similarly, in the states included in this report, the act of “gross indecency” or in some instances “serious indecency,” is defined in broad terms, if at all. For example, Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, and St. Lucia define gross or serious indecency as: “any act other than sexual intercourse by a person involving the use of the genital organs for the purpose of arousing or gratifying sexual desire.” The vague wording of the law means that LGBT persons are susceptible to arrest and prosecution for a wide range of sexual acts.

|

Buggery Laws and Gross Indecency Laws in the “Commonwealth Caribbean” by Westmin R. A. James[11] The Origin The “Commonwealth Caribbean” refers to those states in the Caribbean Sea and in Central and South America that were British colonies. The independent states in the Commonwealth Caribbean include Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago. It also refers to “British Overseas Territories” (territories that have chosen to remain subordinate to Great Britain rather than becoming formally independent) in the Caribbean and North Atlantic: Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Montserrat and Turks and Caicos Islands. Anti-sodomy laws were a colonial import imposed on the colonies by the British rulers as there was no pre-existing culture or tradition in the Caribbean that required the punishment of consensual same-sex sexual conduct. The first recorded mentions of “sodomy” in English law date back to two medieval treatises called Fleta and Britton.[12] The texts prescribed that sodomites, together with sorcerers, Jews and renegades, should be burnt alive. In the 16th century, a statute of 1533 provided for the crime of sodomy punishable by death. Although this statute was repealed during the reign of Mary I, it was re-enacted by Parliament in the reign of Elizabeth I in 1563, and the statutory offence, so expressed, survived in England in substance until 1861. The Offences Against the Person Act 1861 included the offence of “buggery,” dropping the death penalty for a prison term of (10) years to life. The movement for codification of the criminal law, particularly in the British colonies, gathered pace in the early 19th century when Thomas Macaulay was given the mandate to devise law for the Indian colony. The Indian Penal Code was the first comprehensive codified criminal law produced anywhere in the British Empire. In 1870, R.S. Wright, an English barrister, was asked by the Colonial Office to draft a criminal code for Jamaica, which could serve as a model for all of the colonies. Wright’s Code was not adopted by Jamaica but it was brought into force in Belize (at the time, British Honduras) and later Tobago.[13] Thereafter the buggery law was instituted by the British colonial administration in Jamaica and other Caribbean states in the British Commonwealth in a manner similar to the 1861 British Offences Against the Persons Act. “Homosexuality” is not a crime in the Caribbean but laws criminalize same-sex conduct. Even though colonies in the Caribbean adopted British laws outlawing same-sex intimacy, they vary in language, the types of acts prohibited, and the punishments imposed. Whatever the various incarnations they are often referred to as “sodomy” or “buggery” laws. Many times buggery and sodomy are used interchangeably. Laws criminalizing consensual adult same-sex sexual conduct currently exist in 10 independent countries in the English-speaking Caribbean. Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines have the crime of ‘buggery.’ In 2000, the UK issued an order repealing sodomy laws in its Overseas Territories of Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat, and the Turks and Caicos islands in order to comply with its obligations as a Council of Europe member. After a 2016 successful constitutional challenge the High Court of Belize Supreme Court modified the law in Belize so it no longer applies to consensual sexual acts between persons in private.[14] Savings Law Clauses Barbados presents an added complication to any challenge to these laws. There is a provision in the Constitution of Barbados that prevents the courts from declaring these pieces of legislation criminalizing same-sex intimacy from being in breach of the human rights provisions in the Constitution. This prohibition applies to all laws passed before the Constitution of which the buggery law is one (Belize also had a savings law clause but with a limited life span of five years, which has since expired). |

International Law

The English-speaking Caribbean is an outlier in the region. The continued existence of buggery and gross indecency laws there is in stark contrast with recent developments in Latin America where states including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Uruguay have made rapid advances in family law, as well as in non-discrimination and anti-bias legislation.

In recent years, states including Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Uruguay have opted for same-sex marriage; Argentina and Bolivia have passed legal gender recognition legislation; Chile, Bolivia, and Uruguay have enacted anti-discrimination laws; and El Salvador and Peru have enacted hate-crime laws. Examples of legal measures that have been taken to address violence and discrimination include: in 2012 Argentina became the first state to pass a gender recognition law based entirely on self-identification[15]; in 2010 Brazil enacted the National Human Rights Action Plan (NHRAP), which stipulates specific measures and objectives to address violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity[16]; similarly, in 2014 Mexico established specific teams and units to ensure that homophobic and transphobic hate crimes are investigated and prosecuted to the full extent of the law, and law enforcement officials have been trained accordingly[17]; and in 2016 Uruguay took several measures to address employment discrimination and create job opportunities for marginalized trans people, including a specific call for trans candidates for vacancies at the Ministry of Social Development and within the “Uruguay Trabaja” programme.[18]

Internationally, Latin American states have played a proactive role in protecting people from discrimination and violence based on sexual orientation or gender identity.[19] Several Latin American states, including Argentina, Brazil and Chile are members of the Core Group of LGBT friendly states.[20] The Equal Rights Coalition, a network of states aiming to advance the human rights of LGBT people, was founded in Uruguay in 2016, and includes Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Honduras, Mexico and Uruguay as members.[21]

In recent years, Latin American states have been at the forefront of enhancing protection for LGBT people at the United Nations. The Human Rights Council has adopted three resolutions that reflect the commitment and consistent support of Latin American countries on issues relating to sexual orientation and gender identity. In 2011, a South African led resolution passed by the Human Rights Council, commissioned a global study on discriminatory laws and practices and acts of violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation and gender identity.[22] A follow up resolution in 2014 calling for a report on best practices for countering discrimination was introduced by Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay.[23] A resolution in 2016 led to the appointment of an Independent Expert on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. Seven Latin American states[24]—Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Uruguay—and 41 additional countries jointly presented the text.[25]

The Organization of American States (OAS) and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) have also taken steps to address human rights violations perpetrated against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons in the Americas. All countries covered in this report are members of the OAS. Between 2008 and 2013 the OAS General Assembly approved six resolutions acknowledging and condemning discrimination and acts of violence against members of the LGBTI community, calling on member states, as well as the IACHR and other bodies to take appropriate measures to address the problem.

In its 2015 report "Violence against LGBTI people in America,"[26] the IACHR highlighted that laws criminalizing consensual sex between same-sex persons are incompatible with the principles of equality and non-discrimination. It also underscored the relationship between these discriminatory laws and high rates of violence and discrimination against LGBT people. The IACHR has noted that several states including Barbados, Dominica, and St. Kitts and Nevis, featured in this report, have rejected UN Universal Periodic Review recommendations to decriminalize same-sex acts,[27] citing religious opposition (particularly from evangelical churches[28]) as well as cultural and societal opposition.[29]

Caribbean states have taken steps to increase economic cooperation and regional integration through the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). In 1973, the Treaty of Chaguaramas established the Caribbean Community including CARICOM. And in 1981 the Treaty of Baseterre establishing the OECS economic union. In addition to economic integration, the OECS aims to increase human rights protections. All states covered in this report, with the exception of Barbados, are members of the OECS. [30]

Table 1 – States covered in this report and their membership of CARICOM and OECS systems

|

CARICOM - CSME (Common Single Market and Economy) |

OECS (Organization of Eastern Caribbean States) |

|

Antigua and Barbuda Barbados Dominica Grenada St. Kitts and Nevis St. Lucia St. Vincent and the Grenadines |

Antigua and Barbuda Dominica Grenada St. Kitts and Nevis St. Lucia St. Vincent and the Grenadines |

|

CARICOM & Organization of Eastern Caribbean States |

||

|

CARICOM |

OECS |

|

|

Created |

Treaty of Chaguaramas 4 July 1973 Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas 2001 |

Treaty of Baseterre (6/18/1981) |

|

Member States |

Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname |

Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, British Virgin Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Martinique, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines |

|

Total Population Encompassed |

17,775,192 |

1,049,374 |

Judicial review by supra-national entities, including the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) and the Eastern Caribbean Court, are integral to the sustainability of both regional systems. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) retains jurisdiction for certain countries of the commonwealth.[31] The Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) has original jurisdiction in all matters related to the interpretation of the Treaty of Chaguaramas. It also exercises appellate jurisdiction for commonwealth countries in civil and criminal matters who no longer accept the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) as their appellate court. Barbados, Belize, Dominica, and Guyana have replaced the JCPC's appellate jurisdiction with that of the CCJ.[32] Cases from the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court (ECSC) can be appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The ECSC can only accept cases that have already been considered by the high court of a member state, and thus effectively serves as a supreme court for the OECS.

Appendices I-VII to this report include an overview of country specific legal provisions, treaty ratifications, membership of international organizations, and states’ response to recommendations on sexual orientation and gender identity during the Universal Periodic Review (UPR).

LGBT Activism and Recent Developments in the Region

Activists and civil society organizations have been working intensely on the ground to transform the difficult daily reality faced by LGBT individuals.

The Caribbean Forum for Liberation and Acceptance of Genders and Sexualities (CariFLAGS) has worked for over 18 years to provide LGBTI people in the Caribbean with safe spaces, support services, and stronger communities. Currently based in Trinidad and Tobago, CariFLAGS is composed of several LGBTI NGOs across the Caribbean, including in St. Lucia, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, the Dominican Republic, Belize, Grenada, Guyana, and Suriname.

CariFLAGS has also worked towards policy and cultural change on sexual and gender diversity in the Caribbean. CariFLAGS has as its main stated purpose to: “build a regional LGBTI movement in the Caribbean by strengthening local leadership and organizations, developing shared strategies for social change, coordinating challenges on LGBT rights issues in the courts, addressing underserved needs and groups, and supporting safe environments at the community level.”[33]

Another civil society group active in the region is the Eastern Caribbean Alliance for Diversity and Equality (ECADE), an umbrella body for human rights groups within the small countries of the Eastern Caribbean, such as Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Saint Martin. It serves as a regional hub for the coordination of trainings, strategy meetings, and thematic conferences.[34]

Local and international LGBT organizations have partnered to facilitate LGBTI sensitivity training in the past few years for national police forces in Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Grenada, St. Lucia, and St. Kitts and Nevis, allowing for a more collaborative relationship with police enforcement officials.[35] For example, the Royal Barbados Police Force embarked on sensitivity training regarding the LGBTI community with the intention of bringing Barbados closer to its international human rights commitments. Police officers from Antigua and Barbuda have worked with civil society groups to reinforce the principles of community policing, human rights, professionalism, ethics, and their practical application to the LGBTI community. Diversity trainings in St. Lucia, sponsored by Aids Free World and United & Strong, have focused on managerial skills and senior officer training, providing them with guiding principles to employ in police interactions.[36] Facilitators have gone to some lengths to avoid disputes about morality and religion by focusing instead on HIV prevention and public health.[37]

Civil society organizations have also used the complaints procedure of the IACHR to tackle the criminalization of same-sex relationships in their home countries. Four years ago, Gareth Henry and Ms Simone Edwards filed a petition with the IACHR challenging Jamaican laws that discriminate against LGBT people. The petitioners allege a number of violations by Jamaica of its legal obligations under the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR) and the American Declaration on the Rights of Man (Declaration). At the time of writing, the petition was filed and submissions on admissibility by both Parties were finalized, but an admissibility decision by the IACHR was still pending.[38] The civil society organizations GrenChap and Groundation Grenada filed a petition with the IACHR challenging Grenada’s “unnatural connexion” law. Grenada failed to appear at the hearing. The IACHR urged Grenada to decriminalize same-sex sexual relationships, and in the meantime to issue a de facto moratorium on application of this legislation.[39]

Local and international civil society organizations and individuals have filed lawsuits as well in their efforts to have discriminatory laws in the Caribbean repealed. In 2015, Jamaican activist Maurice Tomlinson filed a challenge against the governments of Belize and Trinidad and Tobago to overturn laws that on their face seek to prevent gay people from entering their countries. The current immigration laws in Trinidad & Tobago and Belize bar "undesirable” persons from entering—a list that includes homosexuals, prostitutes, and members of other marginalized groups.[40] The Caribbean Court of Justice ultimately dismissed the ‘gay travel ban’ case, declaring that the laws, while discriminatory in nature, have not been used in practice.[41] Tomlinson has also brought a fresh challenge to Jamaica’s anti-buggery law; hearings before the Jamaican Constitutional Court started in February 2016.[42]

In 2016 the Belize Supreme Court in the case of Caleb Orozco et al v AG of Belize [43] became the first Commonwealth Caribbean Court to hold that laws that criminalized, inter alia, same-sex intimacy were unconstitutional. The court struck down section 53 of the Criminal Code, which outlawed "carnal intercourse against the order of nature" with punishment of up to 10 years in prison, on the grounds that the law went against the claimant’s rights to human dignity, privacy, and freedom of expression. The court declared that the definition of ‘sex’ in the constitution included ‘sexual orientation,’ protected by the principles of equality and non-discrimination. The court reduced the scope of section 53 of the Criminal Code by excluding sexual activity taking place in private between consenting adults.

In February 2017, Jason Jones, a gay rights advocate, filed a legal challenge in Trinidad and Tobago against laws criminalizing homosexual conduct.[44] Soon thereafter, he claims to have received over 50 death threats.[45]

Two recent referendums, one in Bahamas and the other in Grenada, addressed the prohibition of discrimination based on sex but were defeated by unfounded fears that they would open the legal path to same-sex marriage.[46]

On January 9, 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued Advisory Opinion No. 24[1],[47] in response to a request by the state of Costa Rica, made in May of that same year. In its opinion, the Court advised that state parties to the American Convention should recognize all civil rights for same-sex couples, including the right to civil marriage. The court also advised that states should establish fast, inexpensive and straightforward procedures to ensure legal gender recognition, based solely on the self-perceived identity of a person.

Out of the seven countries considered in this report, only Dominica (1993), Grenada (1978) and Barbados (1982) have ratified the American Convention but neither Grenada nor Dominica recognize the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. This means Barbados is the only country which has a treaty obligation to consider the Court’s opinion, although the opinion should have resonance for all governments that seek to respect and protect universal human rights and equal norms.

Impact on LGBT Individuals

Buggery and gross or serious indecency laws discriminate against LGBT people and have a negative impact on their lives. A 2008 Human Rights Watch report, “This Alien Legacy: The Origins of ‘Sodomy’ Laws in British Colonialism,” traces the history of sodomy laws in former British colonies. The report outlines the effects of these laws on the lives of people most affected by them:

These laws invade privacy and create inequality. They relegate people to inferior status because of how they look or who they love. They degrade people's dignity by declaring their most intimate feelings "unnatural" or illegal. They can be used to discredit enemies and destroy careers and lives. They promote violence and give it impunity. They hand police and others the power to arrest, blackmail, and abuse. They drive people underground to live in invisibility and fear.[48]

The report also refutes the claim that these laws originate in values traditional in former colonies, or reflect deep seated national interests, showing instead that these “Made in Britain” laws were imposed by colonial authorities informed by racist stereotypes and colonialist fears of native sexuality. Whether the laws are enforced or not, their very existence places LGBT people in a perilous situation of vulnerability, inequality, and second-class status in every aspect of life.[49]

Human Rights Watch has published two reports on Jamaica: “Hated to Death” (2004) and “Not Safe at Home” (2014). Both document the negative impact of Jamaica’s anti-LGBT laws, including their role in facilitating discrimination, violence, and barriers to health care.

Recent surveys conducted in Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago have indicated a high level of acceptance for the principle of non-discrimination, including on grounds of sexual orientation, coupled with widespread support for the buggery laws. A survey commissioned by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) Caribbean Regional Support Team in Trinidad and Tobago revealed that most respondents were opposed to discrimination based on sexual orientation. Of the 1,176 interviews conducted during October 2013, 78 percent of the respondents said it was not acceptable for people to be treated differently based on sexual orientation. Additionally, 56 percent of respondents said they were either accepting or tolerant of homosexuals.[50]

Similarly, a survey in Barbados prepared by the Caribbean Development Research Services Inc. (CADRES), showed that 67 percent of respondents were either tolerant or accepting of homosexuals. Most people surveyed, however, thought the buggery laws should be maintained despite “the absence of a clear appreciation of the reasons for the existence of buggery laws.”[51]

As detailed below and in the following chapter of this report, the continued existence of laws criminalizing LGBT conduct, even if infrequently enforced, creates conditions that facilitate abuses in all seven countries covered here. LGBT residents in the Eastern Caribbean interviewed by Human Rights Watch, described how stigma and discrimination permeate all aspects of life, including health care, education, and even everyday activities like going to movies, shopping, and riding the bus. LGBT individuals said that they were reluctant to report abuses for fear of the laws that prohibit same-sex intimacy.

In the countries included in this report, populations are small and social networks insular. Interviewees said that their close-knit communities made it difficult to come out and find acceptance. They were afraid of the negative consequences of being identified or perceived as LGBT. According to CARICOM’s total population estimates for the 2000-2015 period, the populations of the countries included in this report are: 46,398 in St. Kitts and Nevis, 69,393 Dominica, 90,801 Antigua and Barbuda, 110,566 Grenada, 110,255 St. Vincent and the Grenadines, 172,818 St. Lucia and 274,633 in Barbados.

Many interviewees stressed the importance of discretion. Charles, a 24-year-old gay man from Antigua and Barbuda, told Human Rights Watch he would never be openly affectionate in public with another male. He said: “I would never hold hands [with another man]. You couldn’t do that here, because society is just not accepting.”[52] Peter, a 20-year-old gay man from Dominica, said “It saddens me that I have to sneak out and meet someone and can’t bring anyone home.”[53] He said that it was impossible for him to introduce partners to his family, something his heterosexual friends and siblings do at his age. Other interviewees told Human Rights Watch that for discretion and safety they pursued their intimate relationships “off-island,” that is with visitors from other islands in the region, or from further afield. Nicholas, 20, expressed his feeling of constant fear and uncertainty: “you are not safe... you have to hide who you are. Otherwise they will get physical, shouting things. If two men were holding hands people would attack them.”[54]

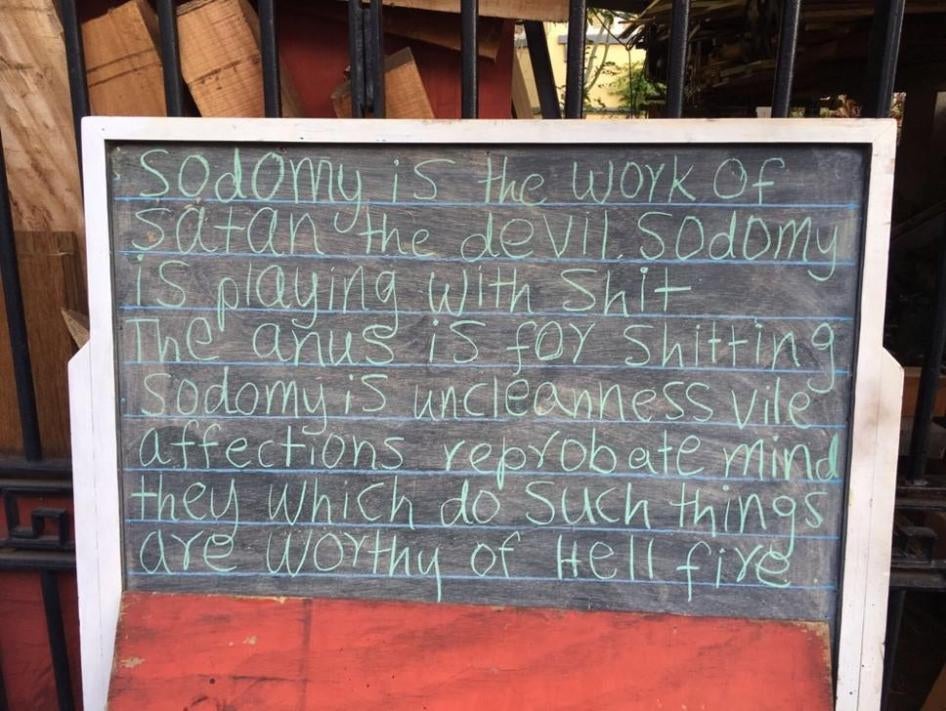

A number of popular dancehall songs, many of which originate in Jamaica, contain strong homophobic language and inflammatory lyrics. This music circulates through the islands and is emblematic of the daily stigmatization and denigration of LGBT people. An extreme example is the decades old, but still popular “Bumbo Red,” a 1990 hit song by dancehall artist Capleton: “Lick a shot inna a battyman head! Lick a shot inna a lesbian head! All sodomite dem fi dead, all lesbian dem fi dead”[55]. It calls for gay and lesbian people to be shot in the head.

A decade later, many popular dancehall songs reiterated the message to kill and maim lesbians and gay men. For example, in 2000, Elephant Man’s “A Nuh Fi Wi Fault,”[56] urged listeners to “When yuh hear a Sodomite get raped/but a fi wi fault/it’s wrong/two women gonna hock up inna bed/that’s two Sodomites dat fi dead” (“When you hear a lesbian getting raped/it’s not our fault/it’s wrong/two women in bed/that’s two sodomites who should be dead”), Beenie Man[57] sings, “I’m dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays,” and Babycham and Bounty Killer’s[58] encourages “Bun a fire pon a kuh pon mister fagoty, ears ah ben up and a wince under agony, poop man fi drown a yawd man philosophy” (“burn gay men ‘til they wince in agony, gay men should drown, that’s the yard man’s philosophy”).[59]

Manage, 35, from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, told Human Rights Watch: “On a daily basis, people see me coming and are very loud calling me ‘Battyman, Faggot, Battyman fi dead’ and using aggressive negative slurs towards me in public. Like in Jamaica, the type of music you listen to, when they talk about gays, the music says ‘kill them.’ Music in St. Vincent is anti-gay.”[60]

Individuals told Human Rights Watch that discriminatory laws had a negative impact on their daily lives. Peter, a 20-year-old gay man from Dominica, said: “the buggery and gross indecency laws say that we can’t be ourselves... These laws allow the negativity towards gay people to exist, the bigotry, [the] law allows people to insult and do anything [to us].”[61]

Florence, a 24-year-old transwoman from Barbados, told Human Rights Watch that the buggery and serious indecency laws “allow people to treat [LGBT] people badly. It steals them into thinking they can get away with it because since the law is ‘on their side’ they think they are being a ‘good’ citizen.”[62]

Jason, a 40-year-old gay man from Barbados, said:

People don’t understand how much pressure it is not to be your true authentic self and how that is such a mental strain. To the point where that is so detrimental to you as a person. If you are living where you are constantly scolded and told that you’re not good for just being you. And it hinders our education opportunities, and work opportunities and taking part in your community, that to me is a human rights violation. It doesn’t have to be physical violence for it to be a human rights violation.[63]

As noted above, one interviewee, a 20-year-old gay man from St. Kitts and Nevis, conveyed the general sentiment about life for LGBT people on the islands when he said: “I have to leave to be me.”[64]

II. Findings

Social Context: A Climate of Homophobia

I don’t come out because my work would be jeopardized.

There is a lack of visibility.

— Nicholas, St. Kitts and Nevis, February 3, 2017

I’ve had coworkers that didn’t want me to use certain things. People who didn’t want to eat off the same plate, cups…They discriminated against me in my job.

— Augusten, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, February 18, 2017

Exclusion from Family

In the islands of the Eastern Caribbean, family and church are at the cornerstone of social life. In these tightly-knit communities and interconnected social worlds, the fear of rejection by family and community runs deep.

For LGBT people homophobic messages are often first heard at home, and amplified in key social spaces, such as school and church. This leaves young LGBT people with a fear of harassment, rejection, stigmatization, and even physical violence. As the following testimonies show, those who are known to be gay or lesbian, or merely perceived to be, have a realistic fear of becoming social pariahs, alienated by family and community. LGBT people can find themselves treated as scapegoats, blamed for social woes such as poverty and AIDS.

Interviewees recounted in painful details the rejection they experienced at home, and the harassment, discrimination, and intolerance they suffered from relatives, neighbors, and friends.

All interviewees described having been harassed or rejected by family at some point in their lives because they are LGBT or perceived to be. Fear of isolation led people to go to extraordinary lengths to conceal their sexual orientation, including by entering heterosexual marriages. Some interviewees reported leaving unbearably hostile home environments. Others were thrown out of home, cut off from family support, and left to fend for themselves. Many experienced homelessness, and lived on the margins of society, vulnerable to rape, violence, and disease.

Those who stayed with their abusive families reported emotional distress as they lived under the shadow of potential rejection and the loss of financial and emotional support.

Coming out was fraught with fear of rejection. Peter, a 20-year-old man from Dominica, now regrets coming out because of the negative reaction from his family. He described his home situation in these terms:

[H]omosexuality in Dominica is taboo, nobody asks about it. Families tend to cover it up. Hiding in Dominica is perfecting the art of acting. Coming out was one of the biggest mistakes I made, if I could turn it back I would… I learn to adapt, I have to put on that fake face.[65]

Florence, a 23-year-old trans woman from Barbados felt compelled to hide her gender identity from her stepfather for fear of being thrown out of her home, although she did confide in her mother:

In the [s]ummer 2010 I confessed to [my] mother that I was attracted to men. My stepdad functioned as dad and was more than extended family. I looked up to him, but his attitudes towards LGBT community let me know that his care to me would be conditional if I told him. He would have kicked me out had I told him anything.[66]

Arthur, an 18-year-old gay man from St. Kitts and Nevis, recalls how his family tried to suppress any expression of effeminacy, from as early as age six:

I was not the most masculine of boys growing up, being called “anti-man” as a result by them….[Whenever] I did something feminine [they would] jump on me…Mother was a very homophobic person, she asked me to change the way I talked and walked, I didn’t like it…. She knew [I was gay] and she was in denial [because of] her feeling embarrassed.[67]

A fear of being shamed or losing face led some families to demand that their LGBT children stay in the closet. Those who chose to be out of the closet faced recurrent threats of violence within their homes. Emily, a 24-year-old trans woman from Antigua, said: “I was threatened by my dad – the first time it happened I was a child, really young. The second time, when I was 16, he found out that I was [LGBT] and told me that he would kill me.”[68]

Nicholas, a 20-year-old gay man from St. Kitts and Nevis, said: “I was threatened by my own mother, [she told her sons that] if any of us is “anti-man” she would kill us. She grew up in a homophobic family.”[69]

The fear of being evicted from his family home led Martin, a bisexual 17-year-old man from St. Kitts and Nevis, to stay firmly in the closet. His 12-year-old cross-dressing brother was shunned by family members who refused to talk to him, so Kevin decided it was prudent to keep quiet about his sexual orientation. He was also mindful of the fact that an openly gay friend of his, aged 18, had been beaten up and had bottles thrown at him by family members and villagers.[70]

Ernest, a 20-year-old gay man from Barbados, suffered a traumatic coming out experience which included physical violence from family members. In 2011 he came out to his mother, who shouted: “how could you like men, that’s nasty, you give up that shit, you’re nasty, you’re nasty!”[71] From that day on, she confronted him with passages from the Bible, while encouraging his brothers to beat him. He said:

I think they were trying to beat it out of me, convert me, but this is who I am, I can’t change it… They’d keep on coming and beating me… Bajans [Barbadians] use the bible to justify their actions. I would call the police, but because my mother knew the police at that station, if I called, then she would call them back and then they would not come. I was a voice in the wilderness and nobody’s paying me any attention.

On one occasion my three uncles beat me up because of being gay. One was in front, one was on the right and one was on the left, and they beat me until I spat blood. They cut my face in all directions. I called my grandfather and he did nothing.

After that my mother put me out. I was on the street for a night. And when my grandmother heard about it she came for me. I had to sleep on grandmother’s floor, she gives me food, but doesn’t support me emotionally. I wish to get away from my family. I have to see my uncles - who beat me - and my mother almost every day.[72]

To avoid stigma and humiliation, and in some cases to spare their families from suffering the same, LGBT people told Human Rights Watch that both gay men and lesbian women maintained relationships with the opposite sex, sometimes getting married, while secretly continuing same-sex relationships.

The desire to belong and be accepted by her family led Sophia, a 35-year-old lesbian from Barbados, to get married to a man. She said:

[A]t 19 I met a guy and he liked me, and I thought “my family would appreciate this.” I decided to get married to him and our relationship lasted for almost 5 years, and that relationship produced one son, he is 14-years-old now. But I was unhappy. I didn’t want to be with him, after 5 years I decided to break it off. My family knew I was unhappy – they would rather have me unhappy with a male than happy with a woman. [They] felt it would ruin their reputation..[73]

After Sophia’s decision to separate from her husband, he and her family tried to deny her access to her son. A government agency in charge of child protection ultimately rejected their efforts as groundless. She recalls:

My sons’ dad and my father decided to take away my son. They placed my boy in a government agency in charge of promoting and protecting children’s rights. They took my son there and started questioning him about what type of treatment he received from me, and if mom had any friends that were LGBT persons. They took him and he endured that for three months. Ultimately, the agency decided “We can’t remove him from his mom. There are no grounds for us to remove him.” At the time my son was 10 years old.[74]

Her alienated former husband continued to make negative remarks about her, saying to their son things like: “if you knew what your mom was you would never go back to her.”[75]

Eviction and homelessness are a staple in the lives of many LGBT individuals. Human Rights Watch interviewed LGBT people who had been forced to move: kicked out of their homes because of the rejection of their family members, driven from home by community members who threatened to kill them, and in some cases violently attacked and forced to seek asylum abroad.

Alfred, a gay 53-year-old man from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, told Human Rights Watch: My mother put me out of my house at age 15–I wasn’t accepted and I struggled on my own.”[76] He roamed the streets from village to village for most of his teenage years in seek of shelter.

Augusten, a 36-year-old gay man and store clerk from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, told Human Rights Watch: “I was 19 when I started to work for my own dollar, I came out and told my grandmother and my cousins that I was gay. At that time I was actually supporting myself. They called me: ‘buller,’ ‘battyman.’ At age 23 [I started dating men and] let myself be and then my uncle and I had a dispute. He forced me to move, he told me to leave on a Wednesday. By Thursday I was out of my grandmother’s house. ”[77]

James, a 24-year-old bisexual man from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, said that he was shunned by his family, thrown out of his home, and beaten by his brothers, even as he sought shelter with friends. He said: “At age 16, I was kicked out of the house. My brothers would go to my friends’ houses and told them that if they see me they would kill me… Black and blue eyes, mainly one of them was doing the bashing, taunting, beating and threatening me. I thought my mother knew [but she played ignorant]. I never spoke about it.”[78]

Thomas, a 34-year-old gay man from St. Lucia, described how his mother wavered between acceptance and rejection, allowing him to stay, and then throwing him out. This left him feeling unstable, insecure, and at times desperate and suicidal:

She keeps accepting me to stay and then she throws me out. I’m homeless right now and there is an apartment right across the street and a lady put me up for a week. I tried to commit suicide, because I am not stable. It’ a hard time – I tried hanging myself in a road near town and somebody stopped me, a stranger. I don’t feel safe, so I decide to stay inside most of the time.[79]

Alanis, a 23-year-old trans woman from Dominica, told Human Rights Watch about her ongoing experience with homelessness and violence within her home due to her gender identity:

I currently stay with my mom. I was homeless a lot of the times, staying on the streets like any vagrant. I try to cope with it, it hurts. I can’t gain employment because of who I am. I got a lot of kicks, jump kicks by my sister, for the simplest things – both my sister and father, always for the simplest things. In terms of my mom, she fractured my arm and slapped me in the face, because of who I am and expressing who I am accordingly. [80]

Toby, a 38-year-old gay man in St. Lucia, recalled his extreme experience of exclusion and ostracism within the home, which drove him to several suicide attempts:

My father found out [I was gay] when somebody told him. When my mom found out – she didn’t speak to me for two years... I could only use one plate, one spoon, I could not touch anything else, it was like I had some contagious disease, they distanced themselves from me. I spent two years in a house where nobody spoke to me. I had nobody to turn to. I was always alone. I tried to commit suicide five times, for some reason it never worked. I left my house, I couldn’t take it anymore after two years of silent treatment.[81]

Erika, a 23-year-old lesbian from St. Kitts and Nevis, told Human Rights Watch that within her community prejudice runs deep and people openly speculate as to whether her son will be gay because he is being raised by a lesbian. Erika had a traumatic rape experience, compounded by social prejudice. She said people assumed that she had been “turned” lesbian because she was raped by a man. She said: “back home they all think that because I was raped, I am a lesbian; and that I fear men. But personally, that wasn’t it. I was raped. I’m a lesbian. I was like that before. I was always attracted to females.”[82]

Exclusion from Church

Interviewees invariably referred to their countries as “Christian” nations. Certainly, church communities are at the center of social life and are ubiquitous across the islands. Churches play an important role in communal life and social welfare. And Christian communities are influential agents of socialization, shaping social attitudes, and moral codes.

Family rejection is often couched in religious terms, leading many interviewees to blame local church rhetoric for the prejudice they encounter within their families and society at large. LGBT people who experienced family rejection on religious grounds said that local pastors reinforced the prejudice that had already alienated them from family members and their communities.

Nicholas, a 20-year-old gay man from St. Kitts and Nevis, reinforced the idea that churches play a significant role in shaping public attitudes towards LGBT people, based on his experience of rejection in his own church community. Nicholas said his church hierarchy perceived him to be too ‘effeminate’ and led pastors to question his ability to take on certain responsibilities in the church choir. He told Human Rights Watch that he received a letter where he was “invited” to take a break from participating in the choir, and soon after taking a trip abroad he was placed on “probation”. Despite his love of the choir, the experience ultimately drove his decision to leave the choir, and the church.

Some individuals have endured extreme situations to stay in their religious communities. Arthur voluntarily submitted to an exorcism ritual conducted by his church pastor in the hope that it would make him straight. His pastor promised to help him “banish the devils” of homosexual desire. It did not work, but Arthur pretended that it did as he was afraid of being outed as gay. He feared being banished from the church “[b]ecause my sexual orientation [did not change after the exorcism]. I could not complain.”[83]

Richard said he avoided participating in certain public activities, including church events, because he is gay. He said: “I was in the church youth. I was very feminine, but I try to hide it…I would just feel strange because of my feminineness.”[84]

Michaela, a 22-year-old artist and lesbian from Grenada, said: “I want the church to do something. The church runs everything. If they become more accepting, like having gay people in the congregation, it would be a step in a better direction.” [85]

In 2017, the archbishop of the West Indies and Anglican bishop of Barbados, Dr. John Holder, spoke out against violence against LGBT people, stating that every human being must be treated equally. He emphasized to believers that an individual’s sexual orientation does not deny their status as a child of God. [86]

|

Statement of the Holy See, Delivered at a UN Side Event in December 2009[87] In 2009 the Holy See participated in a panel discussion at the UN in New York and delivered the following statement about criminalization of homosexual conduct. The Holy See opposes all grave violations of human rights against homosexual persons and is opposed to discriminatory penal legislation which undermines the inherent dignity of the human person. *** Mr. Moderator, Thank you for convening this panel discussion and for providing the opportunity to hear some very serious concerns raised this afternoon. My comments are more in the form of a statement rather than a question. As stated during the debate of the General Assembly last year, the Holy See continues to oppose all grave violations of human rights against homosexual persons, such as the use of the death penalty, torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment. The Holy See also opposes all forms of violence and unjust discrimination against homosexual persons, including discriminatory penal legislation which undermines the inherent dignity of the human person. As raised by some of the panellists today, the murder and abuse of homosexual persons are to be confronted on all levels, especially when such violence is perpetrated by the State. While the Holy See's position on the concepts of sexual orientation and gender identity remains well known, we continue to call on all States and individuals to respect the rights of all persons and to work to promote their inherent dignity and worth. Thank you, Mr. Moderator. ________________________ The Reverend Philip J. Bené, J.C.D. Permanent Observer Mission of the Holy See |

Bullying and Exclusion from School

School bullying is ubiquitous and can affect anyone. But LGBT children are particularly vulnerable to bullying. They experience higher levels of victimization and are at greater risk of being bullied at school.

Interviewees recalled multiple types of bullying and harassment that they encountered at school, and the consequences this had for their safety, sense of belonging, and ability to learn. Interviewees said that teachers were ill-equipped to intervene to stop bullying. And in some cases teachers encouraged verbal harassment, or did little to stop it. Some interviewees recalled that teachers themselves made dismissive or derogatory comments about LGBT people, sometimes passing them off as jokes, sometimes being openly disparaging.

Michaela, a 22-year-old artist and lesbian from Grenada, recalled her teacher’s unwillingness to stop bullying when she was a 16-year old high school student: “when bullying happens, you tell the teachers and they don’t do anything.”[89]

Nicholas, a 20-year-old gay man from St. Kitts and Nevis, found himself and his boyfriend outed on social media when they were both high school students, around age 15. His boyfriend at the time was outed when his picture was circulated on social media. He described his terror as beyond anything he had ever experienced up until then:

When I was still in high school and about 15 years old I was dating this guy even though I was in the closet. I had a profile on social media and someone started outing people. My boyfriend was named in the list. I did not know about it until I went to school the next day. The other boys were laughing, calling me names. I got a call during class from my boyfriend. He explained to me what happened, I got sick. The list had exposed 15 guys as gay before it was taken down.

Thereafter, Nicholas says, he was taunted and aggressively harassed for the remainder of his school days.[90]

Arthur, an 18-year-old gay man from St. Kitts and Nevis, described in poignant detail his feelings of isolation and loneliness as a result of being bullied. He told Human Rights Watch about being severely bullied in his first year of high school. He was terrified of meeting new people and tried his best to pass as straight. He described his fear as so disturbing that after any given school day, he would return home and go over each thing he could do in a more masculine way. Nonetheless, he recalled being taunted and unable to move around the school. In his third year in high school, he came out to two friends who outed him to other classmates. His fell into a depression. “I just wanted someone to talk to,” he said. The constant disdain shown by his classmates impacted his academic performance: “Before a final exam someone made a homophobic remark to me. I got a zero, I didn’t do the exam. The reason why I didn’t do it was because I was literally reflecting on what I did to cause that comment and what I could have done different, and how to change it.”[91]

III. Harassment and Discrimination

Physical Violence, Assaults, and Intimidation

Actual physical and sexual violence, or threats thereof, are part of the fabric of everyday life for many LGBT people. Fifteen out of 41 interviewees reported experiencing physical violence, while nine had more than one experience of physical violence.

The threat of violence keeps many people in the closet, afraid of what might happen if their sexual orientation or gender identity is disclosed. Arthur, 18, told Human Rights Watch that his perception of the violence and his fear of being caught up in it “never stops and it happens almost daily.”[92]

In the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the perpetrators were private actors, including complete strangers, neighbors, acquaintances, or intimate partners, who seemed to think they had the moral authority to target LGBT people, without fear of arrest. Perpetrators of violence against LGBT people do so with impunity because they know that their victims are so afraid of stigma and discrimination that they are unlikely to report to the police. Interviewees said they were reluctant to report incidents due to their perception of police inaction and indifference to the crimes against them. Several said they were ridiculed by police or subjected to inappropriate questioning about their sex lives.

Respondents stated that gay men were more susceptible than lesbians to social rejection and physical violence. Amy, a 29-year-old bisexual female security guard from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, told Human Rights Watch: “violence happens more frequently to the gays. They accept more females than males.” She speculated that lesbians showing affection in public titillated dominant male heterosexual fantasies and that this may explain why lesbians are not targeted as often as gays.[93] Even as she said this, however, she noted that anti-LGBT discrimination can and does fuel violence against both gays and lesbians.

Sexual violence is also an ongoing risk and reporting makes gay men susceptible to ridicule or further questioning by police officers about their sexual orientation, which drives their decision to keep silent about it. Bill, A 31-year-old gay man from Antigua and Barbuda, recalled an episode from 2010 that left him with the impression that he had narrowly escaped being raped by an intruder:

At 3 a.m. a man came into my house with a gun while I was sleeping. I heard my bedroom door open, and at first I thought it was my sister. All I saw in the darkness were his boots, a gun, long sleeves, and a mask. I looked up and there was a gunman over me. I was sleeping naked. He told me not to move, he didn’t ask for money. I asked him what was he doing in my house. He replied: “Are you gay?”

I started to get nervous, it was silent for a moment. It took what felt like 60 seconds for him to move the gun away from me and exit my bedroom door.

A year after that I was on a social media dating app where I had my picture up, and someone with a profile with no picture sent me a message that read “I should have taken it from you a year ago.” I immediately knew it was the person who broke into my house. The text continued: “When I come back. I won’t hurt you, you are a good girl. Why act so nough? [acting better than other people].” I started looking outside, scared that he would be back.[94]

Attacks can happen in the streets, at any hour of the day, including in public spaces and at events, such as carnival. Arthur, an 18-year-old from St. Kitts and Nevis, summed up his daily experiences in one sentence: “[When I am] strolling down the street people start yelling out ‘anti-man.’ Suddenly, they [begin to] throw bottles at me.”[95] Similarly, Toby, a 38-year-old gay man from St. Lucia, told Human Rights Watch that he was pelted with stones in 2015 during carnival celebration. And more recently, in April 2016, he and his partner were attacked as they were entering their home one afternoon: “[I knew] it was motivated by us being gay because the term ‘buller’ was used. As we were entering the house, a car pulled out, two persons jumped out….a gun was raised and they tried to pull the trigger, but the trigger did not work. I told my boyfriend to run. They stabbed me, several times, the deepest one was below the navel. My boyfriend was also attacked with stones.”[96]

|

Random Violence

Charles, a 24-year-old gay man from Antigua and Barbuda told Human Rights Watch about his first and only experience of physical homophobic violence, an episode that occurred in November 2016. It was about 7 p.m., he had finished work and was walking home with a friend – a trans woman named Emily. They took a shortcut to the main road where they encountered a man on a bicycle who seemed to be following them. The man rode past them, before turning into an alley where he left his bike. He then walked past Charles and Emily and threatened them along the lines of “Batty-men must die” or “you are close to death”–Charles could not hear precisely. Charles and Emily separated and Charles crossed to the other side of the street, where the man followed him. When the man walked passed him again, this time very close, he felt what he described as a sharp pinch and sting. He soon realized that he was bleeding. He had been stabbed. Afraid, Emily had run away and Charles had fled from his assailant, who began to chase him until Charles finally escaped through some bushes and hid. Charles tried to call people to tell them what was happening. His mother’s phone was off, but he reached his work supervisor and told her what had happened. He then asked people in the vicinity for help, an ambulance was called, and he spent the next three days in hospital. To this day Charles bears a visible scar, about an inch long on the upper-right-hand side of his body. Charles described his attacker to police officials and explained that he had never seen him before and had no idea who he was. He has not seen him since, but says he would recognize him if he did. Charles had never seen his attacker before the attack. He provided a full description to the police and told officers that the assailant made homophobic insults before he was stabbed. Police took his statement, and clothes as evidence. He is unsure of the progress of the case. He was told to go to the police station to get more information but had not done so when we spoke with him. [97] |

In many cases violence occurs out of the blue, as was the case with Augusten, a 36-year-old gay man and store clerk from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, who blacked out after being attacked by a stranger in public. He said: “I had several instances where people pelted rocks and coconuts at me. One time I was walking home and a gentleman stopped me and slapped [me] in the face because I was gay. I actually blacked out, he caught me unguarded.”[98]

Homophobia permeates every sphere of life for most gay men. Sean, a 35-year-old from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, said:

In my life, I have been bullied, I have been harassed, maligned, terrorized because I am an openly gay person. So, if I’m somewhere, and a DJ would see me, they would announce it by saying something like “we have a battyman in the house” and put on homophobic music and the people would celebrate and respond to that. One night I was walking home, and there was a group of five guys, one shouted: “Battyman, fi dead” [gays should die] and suddenly they started throwing stones and bricks at me.[99]

Ernest, a 20-year-old gay man from Barbados, said he was violently attacked while swimming:

Last week, on Saturday I decided to go to the water and swim. Two young teenagers, aged 11 and 13, passed along the coast and suddenly I saw rocks coming down from the hill, they literally threw rocks at me. They knew who I was. They are from my neighborhood, it is a close-knit community.[100]

Gay men have routinely sought asylum on grounds of the homophobic violence experienced in their home country. Gabriel, a 36-year-old gay man from St. Lucia, sought and was granted asylum in Canada. He told Human Rights Watch: “In late 2009 when I was living in Castries, I could have ended up dead. Because I’m gay it would be swept under the rug.”[101] Two interviewees asked Human Rights Watch researchers how they could flee their country and seek asylum in a safer environment.

Michaela, a 22-year-old artist and lesbian from Grenada, told Human Rights Watch that the violence she experienced was perpetrated by complete strangers. She recalled an episode when she went on a beach swimming date with a girlfriend in July 2016. She told Human Rights Watch that they only hugged twice when a man appeared with a harpoon and chased them. She did not report the incident to the police, because in her view: “the police would have the same reaction, except they have guns.”[102]

She also described a similar incident that took place a few months later while spending an afternoon on the beach with her girlfriend. They were confronted by a team of construction workers. Michaela said: “They saw two girls too close and they began shaking the fence that divided the beach and the construction site while yelling “Stop your nastiness! Don’t do that to her! We don’t do this in our country!”[103] The men threatened the two women with a solid plank of wood.

Florence, 24-year-old a trans woman from Barbados, recounted how in mid-April 2016 she had taken a 5-minute walk from her house to a local store at about 9 p.m. to buy dinner when she was attacked by a group of men nearby. She said: “I heard a group yelling “bunfire pun battyman” [set her on fire]. It’s picked up from Jamaican dancehall and made its way here.”

Verbal assaults soon escalated to violence. As she recalls:

I’m walking, I don’t hear the group, which is strange because they always shout. But I hear a smash. Then I hear another smash, and I see a glass bottle skittling by me. And so I turn, and another glass bottle just missed my face, and I scream at them and start heading home. I keep watching the group. They threw bottles, all of them beer bottles, one broke right in front of my feet. Then I picked up a bottle and threw it back at them. They said nothing. As soon as I turned around, I [saw] they were throwing stones, too. They were about the size of my fist.

She took refuge with a neighbor who had two dogs for protection, and called the police. They arrived about an hour later and interviewed the young men who were then giggling among themselves. She identified one of the perpetrators who denied that he was involved.

“He told the officer: “It can’t be me, they gotta be mistaken.” In the end, the officers gave them a warning, and said ‘don’t bother her again.’”[104]

It is not only random strangers who perpetrate violence against LGBT people. Transgender women report being particularly vulnerable to intimate partner violence. Emily, a 24-year-old trans woman from Antigua and Barbuda, told Human Rights Watch about her first encounter with a suitor:

He made me take my clothes off and suddenly he started to shout “You bein’ a battyman–I am not gay don’t mess with me!” as he threatened me and told me he was not into “hanky-panky.” I only had my jeans and handbag but no shirt and no bra. I started to run up the road to get away until I couldn’t see him and met up with another trans woman friend of mine. It was a really horrible experience. I thought it would be easy, it is not.[105]

Isabella, a 20-year-old trans woman from Barbados, told Human Rights Watch about an incident in January 2016 when she was struck in her face with a bottle, after an altercation with people from her village. She was hospitalized. She said:

It happened very close [to] the police station. Once I went into the police station for help, I was received by an officer who said “do not let your blood on this desk” [but] he wrote the report for me to take to the hospital. In the hospital, I waited for three hours, gushing blood. Eventually a nurse came and wiped my face, the blood had hardened, she cleaned me up, and sent me off.[106]

Alanis, a 23-year-old a trans woman from Dominica, recalled a series of violent attacks on her between 2009 and 2017. These included several physical attacks which led to head injuries on three occasions. The most extreme form of violence that she experienced was being choked on the street by a stranger after a verbal altercation.[107]

Verbal Abuse and Harassment

Almost all interviewees reported being routinely ridiculed, harassed, threatened, and verbally abused based on their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. Indeed, for many the taunts were so commonplace that they did not deem it worthy of mention to Human Rights Watch researchers. Verbal abuse was so much part of the fabric of everyday life that it went unnoticed and unremarked.