Summary and Recommendations

Venezuela is experiencing a profound humanitarian crisis. Severe shortages of medicines and medical supplies make it extremely difficult for many Venezuelans to obtain essential medical care. And severe shortages of food and other goods make it difficult for many people to obtain adequate nutrition and cover their families’ basic needs.

The Venezuelan government’s response to date has been woefully inadequate. Authorities deny the existence of a crisis. They have not articulated or implemented effective policies to alleviate it on their own, and have made only limited efforts to obtain international humanitarian assistance that could significantly bolster their own limited efforts.

While the government continues to argue that the crisis does not exist, Venezuelans’ rights to health and food continue to be seriously undermined, with no end in sight. As UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Prince Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein put it in September 2016, Venezuela has suffered a “dramatic decline in enjoyment of economic and social rights, with increasingly widespread hunger and sharply deteriorating health-care.”

Human Rights Watch examined the scope and impact of this crisis through field research in six states and the capital, Caracas, in June 2016, and subsequent interviews via telephone and other media. We visited public hospitals, as well as locations where people were lined up to purchase goods subject to price controls set by the government.[1] We interviewed more than 100 people, including health care providers, people seeking medical care or food subject to price controls, people who had been detained in connection with protests linked to the shortages, human rights defenders, and public health experts.

We found that the shortages, which have increased over the past two years, are taking a heavy toll on the well-being of many Venezuelans. Our findings are consistent with those of professional organizations from the health sector, academics who have conducted surveys on the extent and impact of food scarcity, and local non-governmental groups. Internal reports from the Venezuelan Health Ministry reviewed by Human Rights Watch include rates of infant and maternal mortality in 2016 that are substantially higher than the rates reported in previous years. According to health professionals interviewed by Human Rights Watch, unhygienic conditions and medical shortages in hospital delivery wards are important contributing factors to the sharp rise in infant and maternal mortality rates.

The Venezuelan government has repeatedly downplayed this crisis and there is no indication that it has moved with sufficient urgency to alleviate it. In June 2016, Foreign Affairs Minister Delcy Rodríguez told the Organization of American States’ (OAS) Permanent Council: “There is no humanitarian crisis in Venezuela. There is not. I say this with full responsibility: there is not.”[2] That same month, Luisana Melo, the health minister, told the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) that “in general, the Venezuelan people have guaranteed access to treat all their illnesses.”[3]

The government has pursued only limited efforts to secure international assistance, and these have not succeeded in alleviating the crisis. At the same time, it has rejected an effort by the National Assembly to facilitate the provision of additional assistance. In May 2016, President Maduro asked the Supreme Court to block a law by the opposition-led National Assembly that would have facilitated international humanitarian aid and authorize the shipment of medicines from abroad. The court—which ceased functioning as an independent check on executive power under President Hugo Chávez—did precisely that. Humanitarian NGOs working in Venezuela told Human Rights Watch that they face obstacles to providing humanitarian relief in the country.

When government officials have acknowledged the existence of shortages, they have claimed that these are the result of an “economic war” being waged by the political opposition, the private sector, and foreign powers.[4] The government has provided no credible evidence to support these accusations. To the contrary, many analysts argue that the government’s own economic policies, combined with collapsing global oil prices, have directly contributed to the emergence and persistence of the crisis.

This narrative of sabotage and “economic war” has provided a public rationale for the government’s use of authoritarian tactics to intimidate and punish its critics. Doctors and nurses at public hospitals have been threatened with dismissal from their jobs in response to public statements regarding the shortages. Local human rights organizations have been threatened with the loss of international funding. Ordinary Venezuelans who have participated in protests—both planned marches and spontaneous demonstrations—have at times been subject to detention, beatings, and unjustifiable prohibitions on further protest activity. Some have been prosecuted in military courts, in violation of their right to a fair trial.

Shortages of Medicine and Medical Supplies

Venezuela’s health care sector has been wracked by shortages of basic medicines and other crucial medical supplies, leading to a sharp deterioration in the quality and safety of care in hospitals visited by Human Rights Watch. The shortages have increased since 2014, according to interviews with health care professionals and patients, and information published by professional, academic, and non-governmental organizations.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 health professionals, including doctors and nurses, who worked at 10 facilities (eight public hospitals, a health center on the border with Colombia, and a foundation that provides health care services to patients). At all of the hospitals we visited, doctors and patients reported severe shortages—and in some cases the complete absence—of such basic medicines as antibiotics, anti-seizure medication, anti-convulsants, muscle relaxants, painkillers, and many others. An unofficial survey by a network of more than 200 doctors in August 2016 found that 76 percent of public hospitals lack the basic medicines that the doctors said should be available in any functional public hospital, including many that are on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) List of Essential Medicines. This represented an increase from 55 percent of hospitals in 2014, and 67 percent in 2015.

Supplies lacking or in short supply in public hospitals included sterile gloves and gauze, antiseptics, medical alcohol, scalpels, needles, catheters, IV solutions, nebulization kits, and surgical sutures. Even basic cleaning products (such as bleach), essential to ensuring a sterile environment at the hospitals, were frequently lacking. Unsanitary conditions have led to preventable in-hospital infections.

Faced with such shortages, doctors ask patients to purchase medicines and supplies on their own. Many patients try their best but come back empty-handed or with only some of what is needed. The president of the nationwide organization Venezuelan Federation of Pharmacies estimated in June that 85 percent of medicines that should be available in private pharmacies were unavailable or difficult to obtain—up from 60 percent at the end of 2014.

Human Rights Watch heard credible reports of scores of cases in which people with such chronic medical conditions as cancer, hypertension, diabetes, and epilepsy—as well as organ transplant patients—struggled to find essential medications. The medicines they need are often unavailable at both public and private pharmacies, are prohibitively expensive if purchased abroad, and are either unavailable or so expensive on the black market—where they also come with no quality guarantees—as to be virtually unobtainable.

Medical staff told Human Rights Watch that shortages often prevent them from carrying out basic medical procedures and providing essential care to patients. For example, they have been forced to delay surgeries, and they have resorted to giving only partial courses of antibiotics and medicines, a practice that can cause relapses and may lead to drug-resistant infections.

The Venezuelan government has largely failed to publish key health care statistics, including on maternal and infant mortality rates, making it difficult to assess the overall impact of the crisis.[5] However, the limited available official statistics paint a dire picture.

The official rates of infant and maternal mortality reported by the Venezuelan government have increased substantially in recent years.

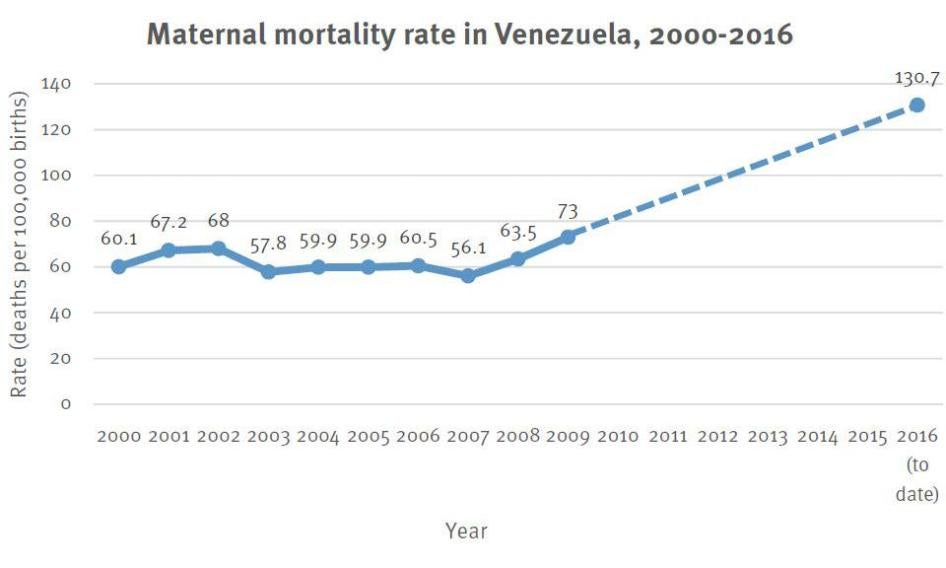

An internal report by the Ministry of Health obtained by Human Rights Watch reported a rate of maternal mortality at 130.7 deaths for every 100,000 births between January and May 2016, a rate that is much higher than for previous years for which the government has made information available. The 2016 rate is 79 percent higher than the most recent rate reported by the Venezuelan government, in 2009, which was 73.1. Between 2003 and 2008, the rate was between 49.9 and 64.8.[6]

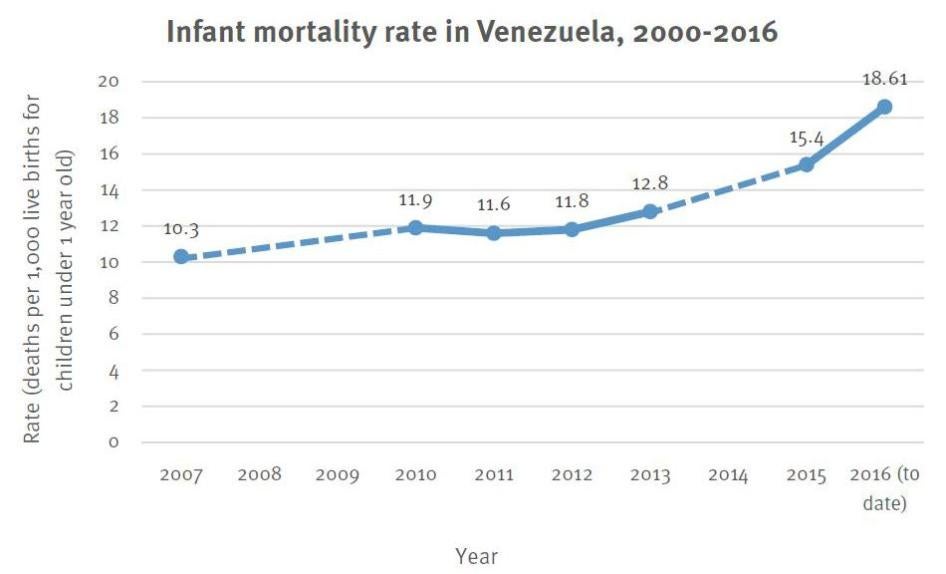

A second internal Ministry of Health report reviewed by Human Rights Watch indicates that that rate of infant mortality in Venezuela for the first five months of 2016 was 18.61 deaths per 1,000 live births. This figure is 21 percent higher than the rate of 15.4 that the government reported to the United Nations in 2015; and 45 percent higher than the rate of 12.8 reported for 2013. No data were reported for 2014. The infant mortality rate was 11.6 in 2011 and 11.8 in 2012.

Human Rights Watch reviewed official data reported by other governments throughout the region since 2000 and found no evidence of similar increases in the reported rates of maternal and infant mortality. However, for most countries no data is publicly available yet for 2014 and after, the years for which Venezuelan data show increased maternal and infant mortality rates.

Shortages of Food and Basic Goods

Venezuela is facing severe shortages of basic goods, including food. It is increasingly difficult for many Venezuelans—particularly those in lower or middle-income families who rely on items subject to government-set maximum prices—to obtain adequate nutrition.

While vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, and some imported basic goods are available in some markets—and certain stores carry such luxury goods as imported olive oils and wines—many Venezuelans can only afford food subject to price controls, which is now in short supply.

Human Rights Watch researchers found long lines forming whenever supermarkets received goods subject to government price controls. Those waiting in food lines told researchers they were trying to buy a small range of items sold at government-set maximum prices, including rice, pasta, and the flour used in the country’s national dish, arepas. Supermarkets often ran out of limited stock long before everyone in line had been served.

The foods and other basic goods—such as diapers, toothpaste, and toilet paper—that people could buy were strictly limited, if available at all. For example, people usually could buy one kilogram of corn flour or rice, or two packs of diapers, per week, if those items were available. Some items, like sugar and toilet paper, have disappeared from supermarkets for months at a time, people in lines told researchers.

A 2015 survey by civil society groups and two leading Venezuelan universities of 1,488 people in 21 cities throughout the country found that 87 percent of interviewees—most of whom belonged to low-income households—had difficulty purchasing food. Twelve percent of interviewees were eating two or fewer meals a day.

Public health scholars have linked food insecurity in several Latin American countries with major physical and mental health problems among adults, and poor growth and socio-emotional and cognitive development in children. In Venezuela, several doctors, community leaders, and parents told Human Rights Watch that they were beginning to see symptoms of malnutrition, particularly in children.

Government Response to Shortages

Since January 2016, the Venezuelan government has announced a series of initiatives aimed at addressing shortages of medicines, foods, and other basic goods. These include measures to increase local production of medicines, medical supplies, and food. If properly implemented, some of these initiatives could help reduce the shortages. So far, however, they have not significantly alleviated the severity of Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis.

The Venezuelan government has sought humanitarian assistance from abroad, but to a very limited degree. So far, the government’s own policy initiatives and its limited efforts to secure international assistance have fallen far short of what is needed to alleviate the shortages. Nonetheless, it does not appear that the Venezuelan government has sought to obtain additional assistance that might be readily available. On the contrary, the government has vehemently denied the extent of the need for help and has blocked an effort by the opposition-led National Assembly to seek international assistance.

Human Rights Watch is not aware of a single large-scale health assistance program run by a major international humanitarian non-governmental organization currently addressing the medical crisis in Venezuela. Human Rights Watch has had confidential discussions with people working for five major humanitarian non-governmental groups and one working for the United Nations, who reported facing significant obstacles to work in Venezuela during the current crisis.

Government Response to Critics

Human Rights Watch documented dozens of cases in which Venezuelans reported being subject to intimidation or violence by government agents in response to public criticism or protests of the government’s handling of the country’s humanitarian crisis.

Doctors and nurses reported being threatened with reprisals, including firing, after they spoke out publicly about the scarcity of medicines, medical supplies, and poor infrastructure in the hospitals where they worked.

Human rights defenders reported a climate of intimidation resulting from measures enacted by the government to restrict international funding and repeated, unsubstantiated accusations by government officials and supporters that they were conspiring to destabilize the country. In May 2016, President Nicolás Maduro issued a presidential decree in response to the “economic emergency” instructing the Foreign Affairs Ministry to suspend all agreements that provide foreign funding to individuals or organizations when “it is presumed” that such agreements “are used with political purposes or to destabilize the Republic.” While national security is of course a proper concern of government, the sweeping language here can be used, and indeed appears to be designed, to undermine the ability of independent civil society groups to operate effectively and free from fear of reprisal.

Even though, to Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, these restrictive legal constructs have not yet been applied in any specific cases, local rights defenders say they have intensified a hostile environment that seriously undermines their work. This is particularly problematic in Venezuela because government policies for more than a decade have curtailed free expression, limiting the availability of critical media outlets and cowing the media into self-censorship.

Ordinary Venezuelans reported being arrested during street protests over food scarcity—some organized and some spontaneous—and being subject to beatings and other mistreatment while in detention. These detentions followed a similar pattern to scores of other cases documented by Human Rights Watch in Venezuela in 2014, when the government launched a widespread crackdown on largely peaceful anti-government protests.

Human Rights Watch obtained credible accounts of new cases in six states between January and June 2016 involving the arrest and prosecution of at least 31 people, at least 20 of whom allege that they were subject to physical abuse while in detention. In a majority of these recent cases, the detainees were charged in military courts, in violation of their right to a fair trial. In most cases, prosecutors failed to provide any credible evidence of criminal activity. As in prior cases documented by Human Rights Watch, all 31 detainees were released on conditional liberty, with charges pending, and most were warned not to participate in any further protest activity.

Recommendations

To the Venezuelan Government

President Maduro and his administration should take immediate and effective steps to address the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela. Specifically, President Maduro should:

- Develop and implement effective policies to address the crisis in Venezuela’s health sector and shortages of food, and make those policies publicly known;

- Provide regular statistical updates on basic health indicators, including maternal and infant mortality rates;

- Ensure that government supporters tasked with the distribution of food and other goods subject to government-set maximum prices do not discriminate against political opponents or critics; and

- Actively explore wider opportunities to secure assistance from international humanitarian aid agencies to alleviate the suffering of Venezuelans who lack proper access to medicines, medical supplies, medical treatment, and food; and facilitate the implementation of programs offered by these organizations.

The president and his administration should end the use of authoritarian tactics to intimidate and punish critics. Specifically, the president should:

- Order the Minister of Health to ensure that doctors and nurses working at public hospitals do not suffer reprisals for criticizing or expressing public concern about shortages of medicines and medical supplies, poor hospital infrastructure, or the government’s response to the crisis;

- Ensure that government officials do not issue unfounded accusations against human rights defenders regarding their alleged participation in “destabilization” plans; and

- Order security forces, including the National Guard and police, to end their mistreatment of detainees and refrain from indiscriminate detention of people participating in organized or spontaneous protests.

To the Attorney General

The Attorney General should undertake prompt, thorough, and impartial investigations into all allegations of abuse documented in this report—including arbitrary arrests and physical mistreatment of detainees, and political discrimination in the distribution of food and other goods.

To OAS Member States

In May 2016, OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro presented a comprehensive report on the humanitarian and human rights crisis in Venezuela, and called for invoking the Inter-American Democratic Charter. The OAS Permanent Council met on June 23, 2016, to discuss Almagro’s report. Rejecting Venezuela’s contention that a debate on the report violated its sovereignty, a majority of member countries voted to move forward and evaluate Venezuela’s compliance with the charter.

OAS member states should:

- Take the findings included in this report into account when evaluating the situation in Venezuela and the nation’s compliance with the Democratic Charter;

- Press President Maduro and his administration to adopt serious, effective, and immediate measures to address the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela, including but not limited to those listed above; and

- Maintain strong international pressure on the Venezuelan government—including through close and continuous oversight of developments in Venezuela within the process of the Democratic Charter—until it shows concrete results addressing the political and humanitarian crisis.

To International Humanitarian Agencies

Even without a request for assistance from the Venezuelan government, UN humanitarian agencies—including the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and UNICEF—should publicly offer humanitarian assistance to the Venezuelan government to help alleviate the crisis in the short term. These agencies should also publish a comprehensive, independent assessment of the situation on the ground, including on the extent and impact of the shortages of medicines, medical supplies, and food. The assessment should offer a detailed explanation of the needs in Venezuela, as well as the different alternatives available for the Venezuelan government to satisfy those needs through existing programs of these agencies.

A Note on Methodology

This report is based on more than 100 interviews with health care professionals, patients suffering an array of illnesses, people standing in line to purchase goods subject to government-set maximum prices, community members, former detainees, and human rights defenders. The interviews were conducted primarily during research missions to Venezuela in June 2016, which included visits to Caracas; Maracay (Aragua State); Valencia (Carabobo State); Barquisimeto (Lara State); San Cristóbal and Capacho (Táchira State); Betijoque, Valera, and Trujillo (Trujillo State); and Maracaibo (Zulia State). Some of the interviews—including with doctors in other locations such as Yaracuy State—were conducted via telephone, email, WhatsApp, or Skype following the fact-finding missions.We also consulted a number of public health experts in Venezuela and abroad to help us interpret the findings of our research.

Interviews were conducted by Human Rights Watch staff in Spanish or with a translator. Interviewees were informed of how the information gathered would be used, and informed that they could decline the interview or terminate it at any point. In some interviews, Human Rights Watch paid reimbursement for transportation. The names of some victims have been replaced with pseudonyms, and the names of some health care professionals have been withheld for security concerns, as indicated in relevant citations.

In all, Human Rights Watch researchers visited eight public hospitals, one health center, and a foundation that provides health care in Caracas and in other cities in four states—Valencia, Carabobo State; Barquisimeto, Lara State; Capacho and San Cristobal, Táchira State; and Betijoque and Valera, Trujillo State. We interviewed 18 doctors and nurses and two hospital staff members, including one hospital director, working in those public hospitals and three others in Caracas and San Felipe, Yaracuy State, which we did not visit ourselves. We also interviewed 38 patients, including 20 who were hospitalized at the time of their interviews.

Human Rights Watch attempted to visit an additional three hospitals in Caracas; Barquisimeto; and Maracaibo, Zulia State, but could not enter the facilities because upon arrival doctors told us that members of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional, SEBIN) and/or armed, pro-government gangs known as “colectivos” were stationed at the entrance of the hospitals to deter unauthorized visits.[7] However, we were able to interview patients who had sought treatment at those locations shortly before our visit.

During field research in June 2016, Human Rights Watch also interviewed dozens of Venezuelans who said they rely on goods and food that are subject to government-set maximum prices, including 20 people while they were standing in lines in Caracas and five states: Carabobo, Lara, Táchira, Trujillo, and Zulia.

In most of the countries where Human Rights Watch works, the practice is to seek meetings with government officials to discuss and seek information regarding the issues on which it is reporting. This has been our practice in Venezuela as well. Between 2002 and 2007, Human Rights Watch staff held meetings with President Hugo Chávez, senior members of his administration, justices of the Supreme Court, the attorney general, members of the National Assembly, and numerous officials in multiple government agencies.However, when conducting research for this report, Human Rights Watch deliberately chose not to establish contact with government officials or otherwise draw public attention to our presence in the country. This decision was made out of concern for possible repercussions for interviewees, the risk of compromising our ability to conduct the research, and the safety of our staff. We also took into account the fact that the Venezuelan government detained and expelled Human Rights Watch representatives from the country in 2008, and declared that our presence would not be “tolerated” there.

To obtain the government’s perspective, we sent a letter to Foreign Minister Delcy Rodríguez requesting information on the government’s views regarding the extent of the crisis and the policies it was implementing to address it. We had not received a response at the time of writing. We also reviewed public statements made by President Maduro and several of his cabinet ministers, as well as statistics and reports by the Health Ministry about maternal and neonatal mortality. We also conducted an extensive review of judicial documents, news accounts in state media outlets, Twitter feeds of government officials, and other official sources to evaluate the Venezuelan government’s position with respect to specific incidents in the report, as well as its assessment of the humanitarian crisis that Venezuela is facing and its response to the shortages.

Shortages of Medicines and Medical Supplies

Clinical conditions that can be treated are cutting people’s lives short because they cannot access medication, neither within the institution nor outside of it.

-Doctor in Valera, Trujillo State, June 2016

People have to buy the majority of supplies because approximately 90 percent of medical and surgical supplies are lacking at our hospital ... and on the black market, the supplies are costing triple or quadruple what they should realistically cost.

-Gynecologist at a general hospital, Valera, June 2016

At all of the hospitals visited by Human Rights Watch—and others where patients we interviewed sought treatment or where doctors we interviewed worked—doctors and patients reported severe shortages of basic medical supplies, sanitary supplies, and medicines. They said that these shortages had become much worse over the past two years.

Their accounts of scarcity were consistent with nationwide shortages reported by Doctors for Health, an independent network of more than 200 doctors working in public hospitals, as well as by the heads of the Venezuelan Medical Federation (Federación Médica Venezolana) and the Venezuelan Federation of Pharmacies (Federación Farmacéutica Venezolana), as described below.

The shortages have taken a heavy toll. Hospital staff told Human Rights Watch that the lack of medicines and equipment often prevented them from carrying out basic medical procedures and providing adequate care. Patients and families spoke of their difficult—and sometimes desperate—struggles to find medicines and supplies to treat chronic conditions or obtain urgent care.

While official information regarding the extent of the shortages and their impact is not publicly available, Human Rights obtained internal documents produced by the Health Ministry that suggest infant and maternal mortality rates may have increased substantially in recent years.

The Scope of the Problem

Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 health professionals, including doctors and nurses, who worked at 10 facilities (eight public hospitals, a health center on the border with Colombia, and a foundation that provides health care services to patients). All reported severe shortages of basic medicines and medical supplies. These included—in some or all of the hospitals—the following:

Essential medicines

- antibiotics (including first-line)

- anti-seizure medications

- anti-convulsants

- muscle relaxants

- adrenaline

- oxytocin

- methergine

- sedatives

- painkillers (ranging from paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to codeine and opiate-based medicines)

Vaccines

- hepatitis A

- rabies

- chicken pox

- rotavirus disease

- meningococcal disease

Surgical and other equipment and supplies

- scalpels

- needles

- catheters

- IV solutions

- tracheal tubes

- nebulization kits

- surgical sutures

- urinary catheters

- urine bags

- yankauer suction cups

Sterilization supplies

- antiseptics

- disinfectants

- medical alcohol

- autoclave tape (used in sterilizing equipment)

Other medical supplies

- surgical scrubs

- surgical shoe covers

- surgical masks

- surgical caps

- surgical brushes

- sterile gloves

- sterile gauze

- bandages

- medical plaster

- disposable bed linens

In addition, most of the hospitals visited by Human Rights Watch had increasing difficulty conducting basic blood analysis tests, according to the doctors interviewed, and they lacked functioning x-ray equipment.

A 2016 study of 86 public hospitals in 38 cities throughout Venezuela, conducted by Doctors for Health (Médicos por la Salud), a professional network of more than 200 medical doctors, and the non-governmental group Venezuelan Observatory of Health (Observatorio Venezolano de la Salud), found severe shortages or the complete absence of basic medicines—including many that the WHO has included on its Model List of Essential Medicines and which should be available in any functional public hospital—in 76 percent of the hospitals surveyed. This represented an increase from 55 percent of hospitals in 2014, and 67 percent in 2015. The survey also found a shortage of surgical supplies in 81 percent of the hospitals, an increase from 57 percent in 2014 and 61 percent in 2015.[8]

The head of the Venezuelan Medical Federation estimated in April 2016 that more than 94 percent of medicines that would normally be routinely stocked were unavailable at public hospitals.[9]

The shortage of medicines and supplies extends as well to the country’s private pharmacies, according to the doctors and patients interviewed by Human Rights Watch. The president of the Venezuelan Federation of Pharmacies estimated in July 2016 that 85 percent of medicines that should be available in private pharmacies were unavailable or difficult to obtain—up from 60 percent in November 2014.[10]

The Venezuelan government has not released any information about the extent of shortages of medicines. While acknowledging that shortages exist—as discussed in the summary of this report—government officials have downplayed their significance, vehemently denying that the situation amounts to a “crisis.”[11]

Consequences of the Shortages

Doctors, nurses, and patients all told Human Rights Watch that, with medicines and medical supplies unavailable at public hospitals, staff must ask patients or their families to purchase elsewhere what is needed for their treatment. For example, patients needing surgery—including cancer operations or caesareans—are required to bring essentials such as anaesthetics, IV fluids, and scalpels.[12] Yet given the shortage in medicines and supplies in pharmacies, it is often difficult or impossible for the patients or their families to obtain the needed medicines and supplies.

Delays are putting the lives or well-being of patients in danger.[13] This situation is particularly dangerous for patients who need emergency surgery or other forms of urgent care.

- Angela Vásquez, 24, arrived at a public hospital in Barquisimeto, Lara State, in June 2016, with severe abdominal pain.[14] The doctors diagnosed her with acute appendicitis and gave her parents a list of supplies they needed to perform the operation, including surgical clothing, sutures, IV solution, and other surgical supplies, she said. Because the pharmacies were closed for the night, the supplies were only found the next day, and Vásquez had to spend the night and most of the next day in acute pain before she could be operated on. Her parents could not find the antibiotics prescribed to prevent post-surgery infection, which placed her at risk for a post-operative infection.

- Carlos Santiago Mijar, a 3-month-old baby with hydrocephalus—an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain—contracted scabies (a skin infection) in May 2016 while hospitalized at the J.M. de los Ríos Children’s Hospital in Caracas, his mother, Idalia Brito, told Human Rights Watch. Doctors prescribed medication to cure the scabies, which was a prerequisite to operate on him and treat his condition, but Brito said she had been unable to obtain the medication, which was unavailable, and it was therefore impossible for her baby to have the operation.[15]

- At a hospital in Barquisimeto, Human Rights Watch researchers found a young boy who had been bitten in the face by a dog. The hospital did not have the rabies vaccine to give to him, and his mother had been unable to find it, so the hospital could not give the boy the rabies shot.[16]

- At a psychiatric hospital that Human Rights Watch visited in Trujillo State, the general absence of adequate health services, including lack of medicines for patients, some of whom had schizophrenia or bipolar condition, made it very difficult to address the needs of some of their patients, hospital staff told Human Rights Watch.[17] The hospital had received virtually no medicines in 2016, according to the head nurse.[18] The shortage of key medicines—and a collapse of community-based services—created a dire situation, infringing on the patient’s right to health. Patients who exhibited aggressive behavior, for example, were permanently locked inside cell-like rooms. “We don’t have antipsychotic drugs, we don’t have anticonvulsants, we don’t have anything at all,” a nurse told Human Rights Watch. “The institution does not have [medicines] to treat patients, which is why the majority end up in the [isolation] area, so that they don’t escape and harm other patients or us.”[19]

The lack of basic supplies and medicines contributed to an increase in medical complications in hospitals, including an increase in post-operative infections, according to doctors working in different hospitals in Caracas and five states.[20] The head of the surgery department at Pedro Emilio Carrillo Hospital in Valera estimated that in six out of 10 operations at that hospital, patients suffered from post-operation, hospital-acquired infections.[21] A gynecologist there confirmed the sharp rise in infections since January 2016, resulting in the deaths of several patients.[22]

Similarly, a doctor from the University Hospital Dr. Ángel Larralde in Valencia told Human Rights Watch that the percentage of infections after surgeries is “very high” and has led at times to the patient’s death, particularly in cases in which doctors did not have access to the proper antibiotic to treat the infection.[23] The doctor said this problem had worsened in recent years.[24] A doctor at the J.M. de los Ríos Children’s Hospital in Caracas reported that at times they find alternative antibiotic treatment, but sometimes “you don’t have anything.”[25]

Another consequence of the lack of medications at Venezuelan hospitals is that doctors are forced to give patients only partial courses of antibiotics, doctors working in different hospitals in Caracas and five states said. This can result in relapses and may lead to the development of drug-resistant bacteria, a public health risk.

- María Cañizalis, a 4-year-old girl with asthma who suffers from frequent fevers and convulsions due to recurring pneumonia and other medical conditions, was hospitalized two weeks before Human Rights Watch researchers visited her home in Maracaibo, Zulia State. At the hospital, she was treated with antibiotics for only two days of a seven-day course before the hospital discharged her, her grandmother told Human Rights Watch. Her family was unable to afford the antibiotic and constantly struggled to find and afford the other medicines she needed, and when Human Rights Watch interviewed her, she had relapsed, suffering from a high fever and convulsions. Her relatives did not know what to do, having run out of money and treatment options, they said. “At times, we had to stop buying food to buy the girl’s medicine. This is how we do it now in Venezuela: stop eating a bit to buy medicine,” her grandmother told Human Rights Watch.[26]

Doctors and nurses told Human Rights Watch that they are often unable to provide basic treatment and care that until several years ago they would have been able to provide.

Infant and Maternal Mortality

The official rates of infant and maternal mortality reported by the Venezuelan government have increased substantially in recent years.

An internal report by the Ministry of Health obtained by Human Rights Watch reported a rate of maternal mortality at 130. 7 deaths for every 100,000 births between January and May 2016, a rate that is much higher than for previous years for which the government has made information available.[27] The 2016 rate is 79 percent higher than the most recent rate reported by the Venezuelan government, in 2009, which was 73.1.[28] Between 2003 and 2008, the rate was between 49.9 and 64.8.[29] It is impossible to know for certain whether the 2016 rate reflects an overall trend or is an outlier—due in significant part to the fact that the Venezuelan government has not made data on maternal mortality rates available for 2010 to 2015.

A second internal Ministry of Health report reviewed by Human Rights Watch indicates that that rate of infant mortality in Venezuela for the first five months of 2016 was 18.61 deaths per 1,000 live births.[30] This figure is 21 percent higher than the rate of 15.4 that the government reported to the United Nations in 2015; and 45 percent higher than the rate of 12.8 reported for 2013. No data were reported for 2014. The infant mortality rate was 11.6 in 2011 and 11.8 in 2012.[31]

The national data suggesting infant mortality rates may have increased substantially is consistent with data and testimony obtained from doctors and nurses at hospitals in various parts of Venezuela. For example, staff at two hospitals provided Human Rights Watch with internal data showing a jump in infant mortality rates in their hospitals. At the Pedro Emilio Carrillo public hospital in Valera, Trujillo state, 5.74 percent of babies born at the hospital between January and August 2016 died, a substantial increase from the rate of 3.74 percent in 2015.[32] (Previously, the rate had declined from 3.69 in 2012, to 3.02 in 2013, to 2.84 in 2014.) In the last few years, between around 5,000 and 5,300 babies per year were born at the hospital.

Similarly, at the Central Hospital in San Cristóbal, Táchira state, 6.65 percent of babies born between January and May 2016 died, a substantial jump from the rate of 2.63 percent in 2015. (Previously, the rate had decreased steadily from 6.5 percent in 2012, to 5.26 percent in 2013, to 5.05 percent in 2014.)[33] In the last few years, between around 3,900 and 5,000 babies per year were born at the hospital.

Independent public health experts from leading universities reviewed this data, as well as the findings from key informant interviews, and all concluded that it is unlikely that the recent increases in Venezuela’s infant and maternal mortality rates reflect a normal fluctuation in these rates. The experts also agreed that it is highly plausible that the shortages in medicines and medical supplies are a major contributing factor to the increases in these rates, and that a humanitarian assistance package including medicines and medical supplies could significantly reduce the infant and/or maternal mortality rates in the short term.[34]

Human Rights Watch reviewed official data reported by other governments throughout the region since 2000 and found no evidence of similar increases in the reported rates of maternal and infant mortality. However, for most countries no data is publicly available yet for 2014 and after, the years for which Venezuelan data show increased maternal and infant mortality rates.

Doctors working in different hospitals in Caracas and five states told Human Rights Watch that they believe that the unhygienic conditions and medical shortages in hospital delivery wards are important contributing factors to this increase. Indeed, UNICEF has said that “timely care in medical facility is often necessary to save the life of a woman experiencing birth complications.” To provide adequate assistance, according to the report, facilities “must have adequate medicines, supplies, equipment, and personnel.”[35]

One doctor told Human Rights Watch that the practice of prenatal medicine had also suffered in his hospital and in many others.[36] According to this doctor:

Preventive medicine is no longer practiced, and in fact, right now, an [expectant] mother finds it difficult to find iron supplements, folic acid, or multivitamins at the pharmacy. Imagine now going to a clinic and getting it for free; that no longer exists. These shortcomings have consequences, including children who are born with a low birth weight or nutritional deficiencies, and for the mothers, infectious problems such as urinary infections that are left untreated. That is why you have a high rate of complications, because these issues are not controlled [by prenatal care]. Then, this results in a high risk of neonatal mortality.[37]

Particularly in the case of premature babies or mothers already suffering nutritional deficiencies, this may increase the risk of death. As a doctor explained to Human Rights Watch:

That is the other side of the story [of the rise in newborn deaths]. Yes, there are neonatal deaths due to a lack of [prenatal care] but also due to the lack of supplies and lack of basic hygiene at the hospital—or due to overcrowding. You may find two, three babies in the same cradle; two or three babies in [the same incubator]. That affects contamination and neonatal mortality.[38]

Another related problem is the transmission of HIV from mother to child. Venezuelan medical protocols to prevent mother-to-child transmission recommend the use of antiretroviral medicines by the pregnant mother before birth, a scheduled caesarean delivery to prevent transmission during birth when needed, and prophylactic treatment of the newborn.[39] A doctor specializing in the prevention of HIV transmission in Venezuela told Human Rights Watch that:

Unfortunately, due to the situation and the humanitarian crisis, there is no compliance with these protocols, or they are not being complied with fully, which ends up exposing the child to possible infection with the HIV virus. We have recent cases of four pregnant, HIV-positive women who underwent vaginal delivery simply because there was no [safety equipment] available for obstetricians to protect themselves from possible infection [during the caesarean].[40]

The Struggle to Obtain Medicines and Medical Supplies

Venezuela’s health crisis affects treatment outside of hospitals as well. Many patients with chronic medical conditions including cancer, hypertension, diabetes, and epilepsy—as well as organ transplant patients—constantly struggle to find medications. The medicines they need are often completely unavailable at both public and private pharmacies, and if they are available on the black market or abroad, they are prohibitively expensive. In addition, medicines and medical supplies obtained on the black market come with no quality guarantees, further undermining patients’ access to adequate health care.

Human Rights Watch interviewed dozens of patients who had struggled to obtain basic medications and medical supplies they needed for a wide range of illnesses. We found case after case in which Venezuelans desperately searched for medications they needed through social media, by creating networks of patients with the same illness to share information when medicines become available, or by exchanging medicines with other people in need. Although some had been able at times to access medication through these means, they are not always successful, and those with more limited resources have found themselves in an even more difficult situation.

Here are some of the stories of Venezuelans interviewed by Human Rights Watch:

- Noel Varela is a 48-year-old man in Valencia, Carabobo State, who suffers from seizures and requires daily doses of anti-seizure medication such as Carbamazepine.[41] A box of 20 pills—which lasts Varela just over 3 days, as he needs to take 6 pills per day—costs just 13 bolivars at the government-set price in pharmacies, but since mid-2015, he has been unable to find them in public and private pharmacies. Varela said that on the black market, a box goes routinely for 100 times the government-set price, and he was able to purchase one in Ecuador for almost 1,700 times the price in Venezuela—which is the equivalent of one and a half times the monthly minimum wage, and over a fourth of his salary.[42]

- Evelin Rosales, a 58-year-old woman from Maracaibo, Zulia State, suffers from severe hypertension, osteoporosis, and vision problems, and was able to obtain medication to treat her conditions until September 2015. Since then, she has been unable to obtain medications to lower her blood pressure from the public pharmacies, and she cannot afford to buy the medication at the higher prices on the informal market, she said. As a result, she suffers from nearly constant headaches and dizziness, and has to be regularly taken to the local hospital to receive an emergency dose of medication (Captopril) to temporarily lower her blood pressure. Rosales fears that without her medication she might suffer a heart attack, she said.[43]

- Carlos Sánchez, a 33-year-old man with cancer in Maracay, Aragua State, was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in October 2015. For his first operation, Sánchez had to purchase and take to the hospital medicines and supplies, including painkillers, antibiotics, and saline solutions, his wife, Ana Vargas, told Human Rights Watch. Vargas said she has used WhatsApp messages and social media, including Instagram and Facebook, to ask for the medicines that Sánchez needed for the operation and has needed since; she has been unable to find them in local pharmacies. Vargas, who works for a government agency, requested that her name be withheld for fear of losing her job or having greater difficulty helping her husband get treatment at public institutions.[44]

- Graciela Giron, a 33-year-old woman with breast cancer in Valencia, Carabobo State, told Human Rights Watch she did not have any trouble accessing her treatment—chemotherapy and an operation—when she was diagnosed in 2013. In October 2015, when she requested her subsequent treatment, which included hormone therapy, through a public pharmacy using her Social Security number, as she had done in the past, she was told that it was unavailable. Giron was able to purchase the medications at a private pharmacy for a few months, but since January 2016, she has been unable to find them in Venezuela. Giron said she needs to purchase the medicines abroad, where they cost 10 times more, and has been organizing events together with other women with breast cancer to raise money to be able to continue with her treatment.[45]

- Lizbeth Hurtado, a 30-year-old patient in Caracas with Crohn’s disease, a chronic gastrointestinal illness, has found it difficult to obtain medication for her treatment since mid-2015. Hurtado said she has had to interrupt treatment, causing a worsening of symptoms including weight and hair loss, intestinal problems, and skin eruptions. Hurtado has been posting her searches for medicine on social media, and has created a network of people who suffer from similar illnesses, through which they share medication when someone finds it. At times, when unable to obtain medication elsewhere, Hurtado has taken expired pills that she got through the network, she said.[46]

- The parents of Carol Jiménez, a 9-year-old girl with diabetes in Valencia, Carabobo State, have found it extremely difficult since mid-2014 to find insulin to control her blood sugar and reactive strips to measure her blood sugar levels, her mother, Deysis Pinto, told Human Rights Watch. Before then, Pinto said, “things were normal, we could go to the pharmacy and even to the laboratories in the hospitals” and find what she needed. Pinto now dedicates her energy to try to find necessary medicines for her daughter, and although she has succeeded, she told Human Rights Watch that the “distress and uncertainty is a daily nightmare.” She said they rely on social networking with other diabetics, including through Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp group messages, to search for medicines at pharmacies in other parts of the country. Because Jiménez has been unable to receive medications shipped from other parts of the country, she has had to wait for someone to travel to Valencia from wherever they were available to deliver her medicines. “That’s how we’ve been able to get the treatment that keeps our children alive,” Pinto said.[47]

- Sandra Silva, the 33-year-old mother of a toddler who frequently develops high fevers with convulsions, the reasons for which are unclear, has been unable to purchase acetaminophen or paracetamol for her son in Táchira State for over a year, she told Human Rights Watch.[48]One of the last times she took her son to a public hospital, doctors were unable to provide him with any medicines. They sent Silva and her son home, and told her she should bathe the boy to stop the fever from going up, she said. Silva told Human Rights Watch that she has bought her son’s medicines in Colombia, where they cost almost 10 times more than in Venezuela.

- Jesús Espinoza, a 16-year-old boy in Valencia, Carabobo State who received three kidney transplants, has been on haemodialysis since 2013, Espinoza and his parents told Human Rights Watch. The mother said they go “from pharmacy to pharmacy to pharmacy” looking for medication, including medicines to control Espinoza’s blood pressure, which is critical to managing his condition. When medication is available, she said, “there’s always a crowd, and when it comes to your turn, they’ve run out. So you can’t get the medicine.” When that happens, mothers at the hospital sometimes exchange various types of medication that their children need, Espinoza’s mother said, which most of the time has helped her secure medication for her son.[49]

Shortages of Food and Basic Goods

We have nothing for lunch.… We have to survive and teach our children that there is no food today, that they should wait until tomorrow, the day after tomorrow … and this is painful because I am old, but they have just started to live [their lives]. [When there is no food] only the two of us [adults] go to bed without having eaten; we try to feed the children bread and a glass of water with sugar, if we have sugar.

-Maria Del Pilar Bosch, Maracaibo, June 2016

In 2003, President Hugo Chávez created the “Mercal Mission,” a program designed to provide low-income Venezuelans access to goods and food whose prices were regulated by the government.[50] Since then, millions of Venezuelans have relied on these items subject to maximum prices set by the government, and it is precisely these people who are suffering the most due to the severe shortages of basic goods, including food, that Venezuela is facing today. While vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, and some imported basic goods are available in some markets—and certain stores carry such luxury goods as imported olive oils and wines—millions of Venezuelans simply cannot afford food that is not subject to price controls, and it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to provide adequate food for their families.[51]

There are no official statistics regarding the levels of scarcity that Venezuela is facing, but the Central Bank of Venezuela reported in January 2016 that the shortage of certain products “is perceived by the people as one of the main problems” in the country.[52] A survey of 1,488 people in 21 cities throughout the country conducted in 2015 by civil society groups, the Central University of Venezuela, and the Catholic University Andrés Bello found that 87 percent of interviewees—most of whom belonged to low-income households—had difficulty purchasing food.[53] Another survey by a well-known Venezuelan private consulting firm evaluated the availability of 42 basic goods, including food and essential household and hygiene products, whose prices are regulated by the government, and found that there were shortages of 74 percent of them in stores. The items of greatest scarcity were cooking oil, flour, milk, grains, and hygiene products, according to the survey.[54] In September, the director of a leading Venezuelan pollster firm reported that 40.6 percent of surveyed Venezuelans spent an average of six-and-a-half hours standing in line to purchase goods whose prices are regulated by the government.[55]

High inflation rates—of 480 percent in April 2016, according to the International Monetary Fund— are eroding buying power.[56] Most workers who receive the monthly minimum wage—of about 22,500 bolivars per month as of September 1, 2016, the equivalent of US$22.50 at the unofficial exchange rate, plus meal benefits valued at almost twice as much[57]—as well as those with informal jobs, must rely on food subject to government-set prices and is thus sold well below market value.

People Human Rights Watch interviewed consistently said that long food lines form whenever supermarkets receive scarce goods, and that the supermarkets often run out of limited stock long before everyone in line has been served. The government’s reaction to complaints and unrest has been to accuse the political opposition and the private sector of generating the food crisis by waging an “economic war.” One key pillar of the government’s response to this crisis has been to grant the military and government supporters broad powers to distribute goods subject to price controls, which would otherwise go to markets where people would have to stand in line to purchase them. As described below, there are credible allegations that this method of distribution has led to political discrimination against government critics.

Public health scholars have found that there is a link between food insecurity and poor health. In different Latin American countries, food insecurity has been linked with major physical and mental health problems among adults, and poor growth and socio-emotional and cognitive development in children. In addition, research has shown that food-insecure individuals are less likely to adhere to medical treatments due to competing limited resources for diverse basic human needs.[58]

Food Lines

During field research in June 2016, Human Rights Watch researchers repeatedly came across long lines wherever goods subject to government-set maximum prices were on sale. Researchers interviewed dozens of Venezuelans who said they rely on these items and food, including 20 people while they were standing in lines in Caracas and five states: Carabobo, Lara, Táchira, Trujillo, and Zulia.

Those waiting in food lines told Human Rights Watch they were trying to buy a small number of food items sold at these prices, such as rice, pasta, and the flour used in the country’s national dish, arepas. Some said that they had not eaten meat in months because it had become unaffordable. Others reported that food subject to price controls was no longer available in rural stores, requiring rural residents to travel to the big cities in search of these food items at the large supermarkets that still received them.

The Venezuelan government has tried to limit the length of food lines through an informal nationwide system under which anyone can wait in line on weekends, but people are only allowed to wait in line one weekday, based on the final digit of their identity number, according to several we people interviewed in lines.[59] Under this system, each weekday is linked to two final digits. Each sale is registered by identity number and fingerprint to prevent people from going to multiple food lines, interviewees said.

The amount of food and other basic goods—such as diapers, toothpaste, or toilet paper—subject to price controls that people can buy is strictly limited, if available at all, some interviewees said. For example, people can usually buy one kilogram of corn flour or rice, or two packs of diapers. (Mothers standing in line told Human Rights Watch that to buy diapers, they had to take the baby or a copy of the birth certificate with them to the store.) Some items, like sugar and toilet paper, have disappeared from supermarkets for months at a time, they said.

In Valencia, Human Rights Watch interviewed people in a line of hundreds waiting to purchase goods subject to price controls. The National Guard members and policemen guarding the line had written consecutive numbers on the arms of those waiting to prevent anyone from cutting the lines.

In Barquisimeto, Omar Monroy, a man in his sixties who was standing in line and had a disability and a heart condition, told Human Rights Watch that he had arrived the previous day at 4 p.m. and had slept on a piece of cardboard to keep his place in line. He said:

I want to buy a bit of everything [that may be available], but we live in a country [where] we have money in our wallets, but can’t find anything to buy. Perhaps after the 14 hours that I spent overnight here, maybe I will get 2 kilos of corn flour for my family. Maybe—because it is a lottery.

My identity card ends in number seven, so I can make purchases once a week on this day. In my case specifically, because of my health, I only come every two weeks.... I’m disabled, and being disabled gives me special access to the line. I should be arriving [in the morning], and not have to spend the entire night here, but with the situation like it is, if I don’t spend 14 hours and sleep here, I can’t even buy what little is available.

[I have never seen a situation like this,] and I am telling you this as a Chávez supporter…. It has been four months since I last ate chicken. I can’t even remember what meat is, what milk is. My grandchildren who are just five years old haven’t had milk in four months.[60]

A 31-year-old pregnant woman told Human Rights Watch that she waited in food lines twice a week, and that “sometimes I wait in line and still can’t get any food.” She said that she “eats two times a day,” and “sometimes I eat, sometimes … I don’t.”[61]

Accessing food subject to price controls is even more difficult for the parents of children with disabilities, who often cannot afford the time away from their children or do not have access to family support services in order to wait in long lines. Elaine Navarro, a 36-year-old mother of four, was 8 months pregnant when Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed her. She had a 16-year-old son, Alejandro José Salcedo, with Down Syndrome and other physical disabilities that demanded intensive support, making it difficult to wait in food lines. She told Human Rights Watch:

We have to wait in lines to buy food, with our children, and the first thing we are told is that we have to leave the child [at home]…. They say to me, “the child is too agitated.” Well, of course, because he has not received his medications for four months.… I am his mother, and in his condition, imagine leaving him [with others].[62]

Impact of Food Scarcity

The impact of food scarcity on the health of Venezuelans remains unclear, as no studies to assess its effects have been conducted to date. A national survey by civil society organizations and two Venezuelan universities published in March 2016 found that in 2015, 12 percent of interviewees were eating twice or fewer times a day.[63]

Another national survey carried out by a consulting firm in August found that 40 percent of those surveyed had eaten twice a day, while 12.5 percent had only eaten once. More than half were unable to go to work because they had to go and search for food, 38.1 percent said their children had to skip school because they did not have enough food to feed them, and 33.6 percent said their children had to skip school to accompany their parents to find food. A total of 85.3 percent of those surveyed feared they would not have enough food in their homes to feed their families.[64]

Several doctors told Human Rights Watch that they were starting to see symptoms of malnutrition in patients that had not been present before the shortages began, particularly children, and that they were concerned about potential serious health consequences. For example, a doctor said that the number of patients diagnosed with malnutrition or with illnesses associated with poor nutrition were on the rise and were reaching levels that he had not seen in the hospital since the 1960s or 1970s.[65]

A doctor at another hospital said that due to the difficulties mothers face in obtaining adequate food, they were currently seeing newborns and babies under 6 months old who were malnourished and required special care.[66]

Similarly, community members and mothers told Human Rights Watch that it has become increasingly difficult to feed children. In Lara State, community members from two neighborhoods where hundreds of families live said children were fainting at school because they were not getting enough food.[67] Navarro, the mother of the 16-year-old boy with Down Syndrome and physical disabilities, said she often had to send her children to bed without dinner:

The situation is not like before, when you could walk down [to the local shop] and buy a pack of flour, bread, rice, whatever. The situation is very hard. And it is painful because it is sad when you have children. [As an adult,] you might be able to put up with it, and just drink a glass of water instead, but how do you say to your children [that there is no food?][68]

Maria Del Pilar Bosch, 59, who lives with her daughter and two grandchildren in Maracaibo, told Human Rights Watch that to buy a kilo of rice, they have to go to the black market, where they cannot afford it, or wait in line for hours, and even then, sometimes they cannot find it. Bosch said that if they do not have food for dinner, they “try to feed the children bread and a glass of water with sugar, if we have sugar.”[69]

Similarly, Morexmar Chirinos, a young mother of two in Valencia, told Human Rights Watch that she needed many things, but “primarily food for my children, because it’s sad when your child comes to you and asks for food, but there isn’t any. That’s the worst thing that can happen, and it’s something that we’ve experienced here.”[70]

CLAPs

In April 2016, in an effort to counter these shortages—or in the government’s words, “counter the economic war” that it blames for the shortages[71]—the government created Local Committees of Provision and Production (Comités Locales de Abastecimiento y Producción, CLAP) that are supposed to function nationwide.[72] A May 2016 presidential decree, which accused the private sector and the political opposition of causing the scarcity of goods, declared a “state of exception and economic emergency,” granting the CLAPs, together with the military and police forces, vaguely defined “vigilance and organization” powers to “guarantee security and sovereignty.”[73]

The CLAPs are charged with distributing, on a monthly basis, bags of goods that generally include limited quantities of items such as oil, corn flour, sugar, milk, pasta, rice, and margarine directly to the homes of Venezuelans who pay the lower, government-set price.[74] Since the creation of CLAPs, goods at these prices have stopped being sold in some supermarkets, according to credible information received by Human Rights Watch, although supermarkets continue to be the main source of such food.[75]

The government claims the CLAPs have provided food to large numbers of people. A national survey conducted by a private consulting firm in August 2016 found that the CLAPs were the primary source of food for only 3.7 percent of those interviewed, while 51.5 percent said it was private supermarkets.[76] Moreover, as the preceding pages show, the initiative has not eliminated pervasive shortages and many Venezuelans still struggle to feed their families.

The Venezuelan media has carried several stories alleging that the CLAPs have discriminated against actual and perceived government critics, including opposition supporters.[77] While we were unable to research most such allegations and do not know how widespread such political discrimination in food distribution might be, the Chávez and Maduro administrations have both previously engaged in such discrimination, for example, by firing or threatening to fire government employees who supported recall referendum petitions against them.[78]

The CLAP distribution process is handled by pro-government groups such as the National Women’s Union (Unión Nacional de Mujeres),[79] the Union of Bolivar-Chávez Battalions (Unidad de Batallas Bolívar-Chávez, UBCH),[80] the Francisco de Miranda Front (Frente Francisco de Miranda),[81] and, in each location, communal councils. Venezuelans who want to acquire a bag of goods subject to price controls fill out a form that asks them, among other things, whether they belong to the ruling party.[82]

Gladys Elena Carreño Mujica, a community member in Moyetones, Lara State, reported to Human Rights Watch that a pro-government leader told her that her community of 600 families would be excluded from distribution programs because it was opposed to the government. She said:

[T]hey go through what they call a political filter, where authorities in each state, each municipality, each district … verify that those who receive CLAP benefits support the government. If not, they are rejected, and benefits don’t come to that community.

Carreño said that as a consequence of such exclusion her community is having greater difficulty in obtaining goods, including flour, sugar, milk, eggs, beans, pasta, rice, and proteins. This, she said, is making it very difficult for parents to feed their children.[83]

This is not to say that all pro-government Venezuelans receive substantial assistance from the CLAPs. Some community members told Human Rights Watch that pro-government and opposition communities are both suffering, and that even in some pro-government areas the CLAPs had not distributed food.[84]

Government Response to Shortages

Since January 2016, the Venezuelan government has announced a series of initiatives aimed at addressing shortages of medicines, foods, and other basic goods. President Maduro has cast these as attempts at “overcoming the economic circumstances generated by the drop of oil prices, and the non-conventional war generated by sectors from the right,” according to the government-funded TV station Telesur.[85] The steps taken include measures to increase local production of medicines, medical supplies, and food.[86] If properly implemented, some of these initiatives could help reduce the shortages. So far, however, their collective impact has clearly failed to blunt the severity of Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis. Some of these initiatives’ impact would only be felt over the medium to long term, if they are successful at all.

The Venezuelan government has sought humanitarian assistance from abroad, but to a very limited degree. The government announced plans starting in February to import medicines from China and Cuba.[87] More recently, a representative of the World Health Organization (WHO) told Human Rights Watch that the agency was assisting Venezuela with the purchase of medicines.[88]

So far, this international assistance has also fallen far short of what is needed to alleviate the shortages. Nonetheless, it does not appear that the Venezuelan government has sought to obtain additional assistance that might be readily available. On the contrary, the government has vehemently denied the extent of the need for help and has blocked an effort by the opposition-led National Assembly to seek international assistance. At the same time, restrictive policies make it difficult for relief agencies and non-governmental organizations to operate in Venezuela.

Government Measures to Promote Health and Access to Food

To address the problems in the Venezuelan health care system, the government announced in March that it would “expand” Barrio Adentro, an initiative launched by President Hugo Chávez in 2003 to provide free primary health care to Venezuelans through Cuban doctors working in local health care centers created to that effect.[89] Since its inception, the program provided medical services to many thousands of poor Venezuelans who had previously had much more limited access to health care. Yet its services reportedly deteriorated after 2006, according to the Venezuelan Human Rights Education-Action Program (PROVEA), a leading organization working on economic, social, and cultural rights since 1988.[90] In 2009, President Chávez announced that his government would “relaunch” the program to address its problems.[91] Yet PROVEA reported receiving hundreds of complaints in 2015 regarding lack of equipment, personnel, infrastructure, and suspension of health services in public hospitals and Barrio Adentro centers.[92]

The government has announced steps aimed at increasing domestic capacity to produce medicines. In July, the health minister reported that six public companies that had been “practically paralyzed” in the past were producing medicines, and that 45 private companies had received special authorization to obtain dollars to purchase raw materials for the production of medicines abroad.[93] The health minister claimed that between January and May 2016, the government had distributed 230 million doses of medicines to treat illnesses with high death rates.[94]

In spite of the actions the government claims to have taken, both doctors and patients described the first half of 2016 as a period in which medical shortages had risen significantly. In follow-up interviews in September, doctors and nurses told Human Rights Watch that the shortages in medicines had not abated.[95]

In response to the food shortages, the minister for agricultural production and lands announced in April that the government had granted credits to 5,000 Venezuelan producers to help them farm their land.[96] The government also announced that it would attempt to ensure the distribution of essential goods subject to government-set price controls through a network of local committees run by the military and government supporters. This method of distribution—called “CLAP” and described in detail in the chapter of this report on shortages of food and other goods—has been dogged by allegations of political discrimination and has not effectively alleviated the shortages, as described in more detail above.

In July, “to increase and strengthen the production” of the agriculture and food sector, the minister of labor adopted a resolution with the aim of “guarantee[ing] the food security of the people, understood as the availability of enough food at the national level and a timely and permanent access to it by the public.” The resolution creates a mandatory system under which public and private entities must “provide” all workers who possess the “adequate physical conditions” or “theoretical or technical knowledge in productive areas” to those entities linked to the agriculture and food sector that are subject to “special measures to increase their production.” Under this special system, the entity where the workers will be forced to work will pay the worker’s salary, and “consequently, the workers must provide the required services” for up to 120 days.[97] Although the decree does not specify whether the worker must agree to being transferred to the new position, after widespread criticism stating it would authorize forced labor in Venezuela, government supporters stated the workers’ transfer would be “voluntary.”[98] Human Rights Watch has not been able to find any official information regarding the decree’s implementation.

International Humanitarian Assistance

In August, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon described the situation in Venezuela as a “humanitarian crisis.”[99] Similarly, in September, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Prince Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein reported that Venezuela had undergone a “dramatic decline in enjoyment of economic and social rights, with increasingly widespread hunger and sharply deteriorating health-care.”[100]

UN humanitarian agencies—including UNICEF, the WHO, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), the FAO, the World Food Programme (WFP), and OCHA—have remained largely silent on the crisis in Venezuela. In July, more than 80 Venezuelan human rights and health non-governmental organizations sent a public letter to Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon criticizing UN agencies for not doing more to address the health and food shortages in Venezuela.[101]

Human Rights Watch is not aware of a single large-scale health assistance program run by a major international humanitarian non-governmental organization currently addressing the medical crisis in Venezuela. However, Venezuela has been receiving some limited support from UN agencies. The WHO has been assisting the government with the purchase of vaccines, as well as medicines and materials for diagnosis of illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and cancer.[102] The FAO has been supporting government programs to “improve the production, distribution and increase consumption of food among people with low income.”[103] It is not possible to determine from the information provided by the WHO and FAO to Human Rights Watch to what extent these programs have effectively contributed to helping mitigate the shortages of medicines, medical supplies, and food that continue to plague the country.

Human Rights Watch has been unable to confirm whether the Venezuelan government has sought international aid beyond the WHO and FAO programs and bilateral agreements with Cuba and China.[104] Yet all available evidence points to the conclusion that the Venezuelan government is not seeking additional assistance on the scale necessary to alleviate the current crisis.

In fact, through its public statements and actions, the government has sent a clear message that such humanitarian aid would not be welcome. In May 2016, President Maduro asked the Supreme Court—which ceased to be an independent check on executive power more than a decade ago—to evaluate the constitutionality of a law by the opposition-led National Assembly that created a special plan to address the “health crisis.” Under the plan, the executive would have been obliged to request international cooperation to address the crisis from key UN agencies, the International Red Cross, and other countries. The law also authorized the shipment of medicines by individuals from abroad. The court struck down the law within two weeks, arguing that only the president had powers to address the shortages, under an executive decree he signed in May declaring a state of emergency. The Supreme Court has also failed to respond to a constitutional appeal filed in May by several human rights organizations in Venezuela, asking it to protect the right to health and order the government to adopt measures to ensure access to scarce medicines and supplies.[105] To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, President Maduro has not made any public statements requesting international humanitarian aid to alleviate the crisis.

In October 2016, pro-government Venezuelan representatives before Parlasur—the legislative body of the regional trade bloc MERCOSUR—voted against a Parlasur resolution calling on member states to send medicines to Venezuela, according to press accounts.[106]

Human Rights Watch has had confidential discussions with five people working for several major humanitarian non-governmental groups and one who works for the United Nations, who say they have faced significant obstacles to work in Venezuela during the current crisis. For example, a reliable source told Human Rights Watch that even leading humanitarian aid groups face difficulties obtaining the registration necessary to legally operate in the country and to import necessary supplies. A source from another organization said that although it has the capacity to implement a program to provide food, school supplies, and personal hygiene items, they had not requested government authorization to implement it for fear of undermining their ability to carry out other activities—already authorized—that do not involve humanitarian aid.

In April 2016, the Venezuelan Episcopal Conference issued a press release stating that “never before have Venezuelans suffered the extreme need of basic goods and products for nutrition and health” and said, “it is urgent that private institutions, such as Caritas” receive authorization to “bring food, medicines, and other goods that come from national and international aid, and organize distribution networks to satisfy the urgent needs of the people.”[107] In June, Caritas reported that it was working to “persuade the government to open a humanitarian corridor in order to allow entry of food and medical supplies” and that the request “had been stalled.”[108]

Government Response to Critics

Human Rights Watch documented dozens of cases in which Venezuelans reported being subject to acts of intimidation or violence by state agents in response to public criticism of or expressions of concern about the government’s handling of the country’s humanitarian crisis.

Doctors and nurses at public hospitals reported being threatened with reprisals, including firing, after they spoke out publicly about the scarcity of medicines, medical supplies, and poor infrastructure in the hospitals where they worked.

Human rights defenders reported a climate of intimidation resulting from measures enacted by the government to restrict international funding—which is critical for their work—and repeated, unsubstantiated accusations by government officials and supporters that they were conspiring to destabilize the country.