Summary

All five fingers are not the same…. People should be respected for who they are.

—Thehan, 43-year-old gay man, Colombo, November 2015

In Sri Lanka, there are two frames: man and woman. Society thinks that if you’re born as a man, you are lucky. If you’re giving up your manhood, you are sinners.

—Bhoomi, 25-year-old transgender woman, Colombo, October 2015

Their words are more piercing than needles.

—Krishan, 40-year-old transgender man, Colombo, October 2015, describing staff at public hospitals and clinics

In Sri Lanka, ideas about the way men and women should look and act are deeply entrenched. Those who challenge gender norms—including many lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people—may face a range of abuses from state officials and private individuals that compromise the quality and safety of their daily lives, and their ability to access services that are central to their realizing basic human rights.

This report, based on interviews that Human Rights Watch conducted in four Sri Lankan cities between October 2015 and January 2016 with 61 LGBTI people, focuses primarily on abuses experienced by transgender people—including arbitrary detention, mistreatment, and discrimination accessing health care, employment, and housing. The report also includes examples of discrimination and abuse experienced by individuals based on actual or perceived sexual orientation, many of which are related to a lack of acceptance of gender non-conformity.

It discusses such abuses within a broader legal landscape that fails to recognize the gender identity of transgender people without abusive requirements; makes same-sex relations between consenting adults a criminal offense; and enables a range of abuses against LGBTI people.

Finally, the report outlines reform measures that the government of President Maithripala Sirisena should take—alongside implementing transitional justice mechanisms and security sector reform and adopting a new constitution—to protect the human rights of LGBTI people so they can live free of violence and discrimination.

Legal Gender Recognition

Sri Lankan law provides no clear path to changing legal gender—although a gender recognition procedure is currently under consideration.

Transgender people in Sri Lanka are rarely able to obtain a national identity card and other official documents that reflect their preferred name and gender, exposing them to constant and humiliating scrutiny about their gender identity—including from police at checkpoints, staff at public hospitals, employers, airport staff, and bank tellers.

Transgender people who wish to change the gender designation on their official identity documents face a bewildering array of bureaucratic obstacles. Government officials handle such applications in an ad-hoc manner, even summarily rejecting applications to change gender on official documents, according to interviewees. In other cases, agencies subject them to arbitrary, invasive, or onerous procedures—including having to produce evidence of gender transition and reassignment surgery, procuring letters from parents explaining how they acted as a child, and having to repeat explanations for different officials of their experience of transitioning.

Frustrated by the situation, some transgender Sri Lankans have filed complaints with the National Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, which in response proposed a “gender recognition certificate” that would allow individuals to change the gender indicated on their official documents, including birth certificates, national identity cards, and passports. In June 2016, the Ministry of Health mailed a circular to various health services and education institutions setting out guidance on issuing the gender recognition certificate to transgender people. As of July 2016, the National Human Rights Commission was awaiting a response to the proposed certificate from the Registrar General’s Department.[1]

The proposed certificate is an important step. However, some of the certificate’s requirements—including evidence of medical treatment and certification from a psychiatrist—fall short of international best practice that recommend that medical, surgical, or mental health treatment or diagnosis should not be necessary for legal gender change.

Unprotected in Law

No laws specifically criminalize transgender or intersex people in Sri Lanka. But no laws ensure that their rights are protected, and police have used several criminal offenses and regulations to target LGBTI people, particularly transgender women and MSM involved in sex work. These include a law against “cheat[ing] by personation,” and the vaguely worded Vagrants’ Ordinance that prohibits soliciting or committing acts of “gross indecency,” or being “incorrigible rogues” procuring “illicit or unnatural intercourse.”

Sections 365 and 365A of the Sri Lankan Penal Code prohibit “carnal knowledge against the order of nature” and “gross indecency,” commonly understood in Sri Lanka to criminalize same-sex relations between consenting adults, including in private spaces. These laws, together with abovementioned criminal offenses and regulations, enable a range of abuses against LGBTI people by state officials and the general public.

Some trans women and MSM said that repeated harassment by police, including instances of arbitrary detention and mistreatment documented by Human Rights Watch, had eroded their trust in Sri Lankan authorities, and made it unlikely that they would report a crime. “They won’t protect someone like me,” said Fathima, a 25-year-old transgender woman in Colombo who does sex work and did not involve police after thugs beat her in 2012.

Discrimination against Gender Non-Conformity

The abuses experienced by transgender people are part of a broader picture of discrimination faced by gender non-conforming people in Sri Lanka. LGBTI people in general may face stigma and discrimination in housing, employment, and health care, in both the public and private sectors. “Their words are more piercing than needles,” one transgender man said of staff at public hospitals and clinics who asked unnecessary personal questions.[2]

This in turn can have serious social and health implications, including inhibiting access to HIV prevention and treatment: Sri Lankan health agencies have identified transgender people and MSM as key populations in addressing the HIV epidemic.[3]

Social standing plays a significant role in the discrimination that LGBTI people face: those who are poor, who engage in sex work, or who obviously do not adhere to rigid gender norms are most vulnerable to abuse, including physical assault or arrest.

***

Sri Lanka has been in the midst of constitutional reform since a new government took office following the electoral defeat of Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2015. This presents an opportunity to expressly incorporate gender identity and sexual orientation into the constitution’s equal protection clause, and other fundamental rights protected under international law that are currently absent from constitutional text, including the rights to life, health, and privacy.

Sri Lanka’s parliament should urgently repeal criminal law provisions that criminalize same-sex sexual relations. Police need sensitivity training and clear guidance on their duty to respect the rights of all people regardless of their gender expression, gender identity, or sexual orientation, and they should be held accountable when they fail to uphold these rights. Doctors, nurses, other medical practitioners, and support staff in the health system need better training, guidelines, and accountability systems to uphold the right to the highest attainable standard of health for LGBTI people in Sri Lanka.

It is the government’s responsibility to ensure the safety of all people within its borders, including by more effectively addressing the violence and insecurity that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people face. Authorities need to send an unambiguous message to law enforcement officials as well as ordinary citizens that all Sri Lankans, regardless of their gender identity or sexual orientation, deserve the same respect, protection, and realization of their rights.

Key Recommendations

To the Parliament of Sri Lanka

- Pass comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation that prohibits discrimination, including on grounds of gender identity and sexual orientation, and includes effective measures to identify, prevent, and respond to such discrimination.

- Repeal sections 365 and 365A of the Sri Lankan Penal Code, which criminalize same-sex relations between consenting adults, and the Vagrants’ Ordinance, which may be used to criminalize transgender people and sex workers.

To the Steering Committee of the Constitutional Assembly

- Explicitly include gender identity and sexual orientation alongside race, religion, language, caste, sex, political opinion, place of birth, and other such grounds as protected characteristics in the non-discrimination provisions of the new constitution.

To the Ministry of Law and Order

- Take all appropriate measures to ensure that all police officers respect the rights to non-discrimination, equality, and privacy, and do not discriminate in the exercise of their functions, including on grounds of gender expression and identity and sexual orientation.

To the Police

- Take all appropriate measures to ensure that all police officers respect the rights to non-discrimination, equality, and privacy, and do not discriminate in the exercise of their functions, including on grounds of gender expression and identity and sexual orientation.

- Stop arbitrarily detaining people based on their gender expression, gender identity, sexual orientation, or sex worker status, including by prohibiting police officers from arresting transgender people for “cheating by personation” under section 399 of the Penal Code.

To the Ministry of Health

- Introduce and implement a gender recognition procedure to allow people to change their legal gender on all documents through a process of self-declaration that is free of medical procedures or coercion.

- Ensure that training for all doctors, nurses, and other health workers includes a component on non-discrimination and health issues affecting LGBTI people.

To the Registrar General’s Department

- Collaborate with the Ministry of Health and other government agencies to introduce and implement a gender recognition procedure to allow people to change their legal gender on their birth certificate through a process of self-declaration that is free of medical procedures or coercion.

- Issue a new birth certificate to people who request to change their legal name and/or gender marker to enable them to avoid constant and humiliating scrutiny about their gender identity triggered by an amended, not reissued, certificate.

To the Department of Registration of Persons, Department of Immigration and Emigration

- Collaborate with the Ministry of Health and other government agencies to introduce and implement a gender recognition procedure to allow people to change their legal gender on their national identity card and passport through a process of self-declaration that is free of medical procedures or coercion.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in Sri Lanka in October and November 2015, and in January 2016. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 61 LGBTI people, of whom 19 were transgender people of diverse sexual orientations. They included individuals from Sri Lanka’s various ethnic groups: 46 were ethnic Sinhalese, 11 were ethnic Tamil, and 4 others were Muslim, Burgher, Sinhalese/Tamil, and Sinhalese/Indian.

Human Rights Watch also spoke with 17 government officials, human rights activists, lawyers, medical professionals, and social services practitioners, and with other marginalized people, including sex workers and drug users, to understand the context and obstacles facing transgender people and MSM.

Research was conducted with the support of Sri Lankan activists and nongovernmental organizations that work with LGBTI people, including EQUAL GROUND, Heart2Heart, and the Family Planning Association. Additional information was gathered from published sources, including laws, United Nations documents, academic research, and media accounts.

Interviews took place in four cities across Sri Lanka: Colombo, the capital; Ambalangoda in the Sinhalese-dominant south; Polonnaruwa in central Sri Lanka; and Jaffna in the predominantly Tamil-dominant north. These were chosen based on geographical diversity and access to networks of LGBTI people or groups conducting HIV work with key populations who were able to help reach out to interviewees. Most interviews were one-on-one or in groups of two or three people, according to the participant’s preference. In addition, three focus groups of 5 to 12 people were conducted. Interviews took place in English with the help of a Sinhala or Tamil interpreter as needed. An open-ended questionnaire guided interviews, but did not strictly limit subjects discussed.

Interviews were conducted in safe locations as suggested by local activists and agreed to by participants. Some follow-up interviews were conducted by phone, email, and Skype between February and April 2016. Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview, how the information would be used, and received verbal consent before interviewing. No remuneration or inducements were provided. In some cases, funds were provided to cover travel expenses. All names have been changed for security reasons, as indicated in the relevant citations, unless an interviewee requested otherwise. In some cases, additional identifying information has been withheld to protect privacy and safety.

Glossary

Bisexual: Sexual orientation of a person who is sexually and romantically attracted to both women and men.

Cisgender: Adjective used to describe the gender identity of people whose birth sex (the sex they were declared to have upon birth) conforms to their lived and/or perceived gender (the gender they are most comfortable with expressing or would express, given a choice).

Gay: Synonym in many parts of the world for homosexual; used here to refer to the sexual orientation of a man whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is towards other men.

Gender: Social and cultural codes (as opposed to sex assigned at birth) used to distinguish between what a society considers “masculine” and “feminine” conduct.

Gender identity: Person’s internal, deeply felt sense of being female or male, both, or something other than female or male. It does not necessarily correspond to the sex assigned at birth.

Gender non-conforming: Behaving or appearing in ways that do not fully conform to social expectations based on one’s assigned sex.

Homophobia: Fear of, contempt of, or discrimination against homosexuals or homosexuality.

Homosexual: Sexual orientation of a person whose primary sexual and romantic attractions are toward people of the same sex.

Intersex: A person born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not seem to fit the typical definitions of “female” or “male.”

LGBT: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender; an inclusive term for groups and identities sometimes associated together as “sexual and gender minorities.”

LGBTI: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex.

Lesbian: Sexual orientation of a woman whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward other women.

Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM): Men who have sexual relations with persons of the same sex, but may or may not identify themselves as gay or bisexual. MSM may or may not also have sexual relationships with women.

Sexual and Gender Minorities: Inclusive term that includes all persons with non-conforming sexualities and gender identities, including lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, transgender people, gender non-conforming people, men who have sex with men, and women who have sex with women.

Sexual Orientation: The way a person’s sexual and romantic desires are directed. The term describes whether a person is attracted primarily to people of the same sex, the opposite sex, both, or neither.

Sex Reassignment Surgery (SRS): Surgical procedures that change a person’s body to better reflect that person’s gender identity. These surgeries are medically necessary for some people; however, not all people want, need, or can have surgery as part of their transition.

Sex Work: The commercial exchange of sexual services between consenting adults.

Transgender Gender (which (also “trans”): identity of people whose assigned gender they were declared to have upon birth) does not conform to their lived gender (the gender that they are most comfortable with expressing or would express given a choice). A transgender person usually adopts, or would prefer to adopt, a gender expression in consonance with their preferred gender, but may or may not desire to permanently alter their bodily characteristics to conform to their preferred gender.

Transphobia: Fear of, contempt of, or discrimination against transgender persons, usually based on negative stereotypes.

Note on Sri Lankan Language Sri Lanka has three official languages: Sinhala, Tamil, and English. The following Sinhala words and phrases appear in this report:

Grama Sevaka: Or grama niladhari, literally “village officer.” The public officer in charge of administrative duties in a divisional area, including issuing character certificates and certifying national identity card applications.

Keri Vasi: Literally means “fucking whore” and is used as an insult.

Para Vasi: Literally means “cheap whore” and is used as an insult.

Ponnaya: Akin to “faggot.” Derogatory term used to describe transgender people, or men who are perceived as “effeminate” or “weak.”

Ponna Wesige Putha: Literally means “faggot son of a whore” and is used as an insult.

Kariya: Literally means “sperm” or “sperm-dog” and is used as an insult.

I. Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation in Sri Lanka

There is no one experience of being lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or intersex in Sri Lanka. Ethnic, educational, religious, regional, and linguistic background can influence how individuals experience daily life, with those further down the economic and social ladder more likely to be targets of mistreatment and discrimination.

However, as discussed below, common social attitudes and systemic barriers underpin violence and discrimination against transgender people, as well as others who do not conform to social expectations of gender and sexuality, including lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and intersex people.

Attitudes toward Gender Non-Conformity and Homosexuality

For many Sri Lankans, attitudes toward gender non-conformity and homosexuality are shaped by social and cultural beliefs about how women and men should look and act, according to which a “normal” sexual relationship is between a woman and man and homosexuality is an illness and “foreign” import counter to national culture.[4]

“I am totally against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual rights. This is not the need of the human being,” said lawmaker Nalinda Jayatissa said in a media interview in December 2015, echoing widely held views. “Same sex marriage is unnatural. It is against the evolution of the human being.”[5]

People who violate gender norms—not just trans people but lesbian and bisexual women who look “masculine,” and gay and bisexual men deemed to be “effeminate”—may be singled out for abuse and discrimination.[6] Transgender and intersex people are often not considered to be “real” men or women. Some said the manner in which they were treated, positively or negatively, depended on whether they looked “convincing” as men or women. However, managing appearance to look more masculine or feminine does not necessarily protect from abuse.

Janitha, a 41-year-old intersex person in Colombo, was assigned male at birth and raised by her parents as a boy, but self-identifies as female. She said that when she approached police over a land dispute in September 2015, an officer insulted her based on her gender non-conformity. Janitha was dismayed that “even after I dressed as a respectable man, he called me all these things.”[7]

Some gay men reported being targeted by the police because of their “feminine” appearance. Geeth said that police have arrested him several times on sex work charges despite the lack of any evidence because he looks “gay” according to Sri Lankan stereotypes.[8] Abeeth, an 18-year-old gay man in Ambalangoda, said that officers forcibly solicited him for sex on one occasion, and arrested and raped him on another, targeting him because he had long hair and was wearing tight pants.[9]

Gender policing often begins at school. Dushan, a 33-year-old transgender man, said that teachers at his girls’ school were so irked by his short hair, they insisted that he wear a bow or a flower in his hair.[10] Maneesha, a 26-year-old lesbian, said there were frequent lesbian “witch-hunts” at her national school in Colombo, and that after two players on her sports team had a relationship, her coach instructed all players to grow their hair to supposedly lessen the risk of lesbianism.

Transgender people are particularly vulnerable to abuse when they begin to adopt a gender expression that aligns with their preferred gender—a time when they are likely to behave and appear in ways that do not conform to social expectations based on their assigned sex. Fathima, a 25-year-old transgender woman in Colombo, said that after she started growing her hair, her family and people in her village told her she needed to behave like a man if she wanted to live there.[11] Eshan, a 37-year-old transgender man in Colombo, said his manager at work pressured him to resign after he began to transition from female to male.[12]

Other LGBTI people also said they were singled out for not conforming to norms related to appearance. Maneesha, a 26-year-old lesbian in Colombo, said: “Whenever people see someone like us, they get uncomfortable.”[13] She said that people in public places openly debate whether she and her gender non-conforming lesbian friends are men or women.[14] Maneesha said that when she had short hair, using public washrooms was a “nightmare” because other women, mistaking her for a man, would stop her entering or ask her to leave[15]—a scenario echoed by other lesbians.[16]

Social and cultural prejudice against homosexuality and gender non-conformity is underpinned by inadequate sexual education in schools, and routinely finds expression in mainstream and social media, as the UN Development Program and others have documented.[17] Dr. Kapila Ranasinghe, a psychiatrist who has worked with transgender people as well as with gay, lesbian, bisexual and intersex people since 2007, said: “Media stigmatize horribly through articles and editorials about sexual minority groups, demonizing these individuals, and misinforming society about medical issues.”[18]

For example, one 2011 editorial titled “MSM to lead HIV/AIDS in Sri Lanka by 2015,” used the high HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Sri Lanka to argue against equal rights for gays and lesbians:

[I]t is pathetic to see that most of [the homosexuals and lesbians and their organisations] are busy fighting for their “rights” and promoting their sexual preference. First of all it is right to safety and health they should fight for.[19]

While there is a school reproductive health curriculum as part of a biology course, interviewees said that teachers sometimes do not teach it and instead ask students to “just read it at home.”[20] One person said the reproductive health chapter was so focused on anatomy and written in such scientific language that “even after reading the chapter, we didn’t know what sex was.”[21] Another recalled being taught about sex by a teacher who was so bashful that she said: “You know what happened to the plant? It also happens to humans.”[22]

|

PENAL CODE |

DEFINITION OF OFFENSE |

MAXIMUM PENALTY |

|

Section 365 |

“Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman, or animal, shall be punished…”[23] |

imprisonment up to 10 years and a fine |

|

Section 365A |

“Any person who.. commits, or is a party to the commission of, or procures or attempts to procure the commission by any person of, any act of gross indecency with another person, shall be guilty of an offence...”[24] |

imprisonment up to two years and a fine |

|

Section 360A

|

Prohibits “procuring” any person to become “a prostitute,” regardless of consent |

imprisonment between two and ten years with the potential for a fine |

|

Section 399 |

“A person is said to ‘cheat by personation’ if he cheats by pretending to be some other person, or by knowingly substituting one person for another, or representing that he or any other person is a person other than he or such other person really is.” [25] |

imprisonment up to one year, or a fine, or both |

Criminalization of Same-Sex Relations, Gender Non-Conformity

Sri Lanka’s Penal Code, a relic of British rule, dates to 1883.[26] Section 365 punishes “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” with imprisonment up to 10 years and a fine.[27] Section 365A punishes “any act of gross indecency” with imprisonment up to two years and a fine.[28]

These provisions are widely understood to criminalize consensual sex between same-sex partners.[29] Section 365A originally criminalized same-sex relations between men; however, the provision was amended in 1995 after the law was criticized for being discriminatory on the basis of sex, so that now it covers same-sex relations between women as well as men.[30]Dr. Yasmin Tambiah, a researcher who has studied the 1995 Penal Code amendments, found that the Technical Committee constituted to draw up recommendations “made a number of progressive recommendations, including the decriminalization of homosexual acts between consenting adults, and therefore a repeal of 365 and 365A, which were usually interpreted as applying to [male] same-sex sexual activity.”[31] Not only were the decriminalization recommendations disregarded, the scope of the law was expanded to include lesbians by making the language gender-neutral.

Although no laws specifically criminalize transgender or intersex people, the offense of “cheat[ing] by personation” under section 399 of the Penal Code has been used to target transgender persons for arrest,[32] based on the assumption that a transgender person taking measures to assume a gender identity that is different from the sex assigned at birth has the malicious intent of cheating others.

Although a number of people who told Human Rights Watch about being arrested did not know the grounds for their arrest, two transgender women from Colombo and Jaffna respectively reported being arrested under “cheat[ing] by personation.”

Interviewees, both transgender and gay men, also said they were arrested under the Vagrants’ Ordinance, a vague regulation dating to 1841 that prohibits soliciting or committing acts of “gross indecency,” or being “incorrigible rogues” procuring “illicit or unnatural intercourse.”

Various provisions in the Vagrants’ Ordinance and the 1885 Brothels Ordinance also criminalize sex work among consenting adults,[33] while section 360A of the Penal Code prohibits “procuring” any person to become “a prostitute,” regardless of consent.[34] A senior police officer affirmed in an interview with Human Rights Watch that police occasionally conduct raids to arrest women and men engaged in commercial sex work in public places.[35] Trans women and other sexual and gender minorities, regardless of whether they are engaged in sex work, are often caught up in these raids.

The criminalization of consensual sex between same-sex partners and the misuse of penal laws to harass gender non-conforming individuals leaves LGBTI people vulnerable to abuses by government officials as well as ordinary people and poses a barrier to LGBTI people reporting abuses to police (see Section III). Nithura, a 31-year-old lesbian, was repeatedly harassed and subjected to death threats by her girlfriend’s father in late 2007 but did not go to the police. “If not for the laws, I would’ve said something,” she said. “I’m a criminal in this country. What’s the point wasting time saying something when the laws are unequal and unjust? I just don’t want to be illegal.”[36]

II. Legal Gender Recognition

Lack of Clear and Simple Gender Recognition

Subject to Scrutiny

Under the laws of Sri Lanka, individuals are considered to be the gender (male or female) registered on their birth certificates. The national identity card (compulsory for all Sri Lankan citizens 16 and older) and passport are issued based on the birth certificate. Such documents are needed to access employment, education, housing, international travel, and public and private services, such as obtaining a driver’s licence or bank account.

Transgender people whose appearance does not match the expectations of others face curiosity about their gender identity as it is. But when transgender people carry documents that list a sex or gender that does not match their identity or appearance, their documents trigger additional scrutiny and pose obstacles navigating everyday life.

Krishan, a 40-year-old transgender man in Colombo, told Human Rights Watch that the first question in job interviews is about his gender, not his qualifications. He recalled one interview in Kandy, Sri Lanka’s second largest city after capital Colombo, that was entirely about his sex change. “We’ve never encountered someone like you,” an interviewer told him right at the start.[37] One look at his documents that identify him as female triggered a barrage of humiliating questions: “Do you have penis?” “Does it get erect?” “Are you able to have babies?” Distressed by a string of demeaning interviews, Krishan gave up looking for full-time work and now works irregular part-time jobs.[38]

Sathya is a 28-year-old transgender rights activist in Colombo whose work sometimes takes her abroad. Every time she returns home to Sri Lanka, she told Human Rights Watch, immigration officials are incredulous when they look at her passport that shows her assigned birth-sex as male. Time after time, they ask the same question: “Why do you have someone else’s passport?”[39] Sathya said she is examined for an additional 30 minutes each time, while other travelers inquire about her.

Sashini was assigned a male gender at birth but started living as female when she was 15, before she had heard of transgender people. “I knew who I was,” she said.[40] But when Sashini tried to get a new birth certificate with a female gender designation, the Registrar

General’s Department rejected her application. In March 2015, Sashini formally petitioned the National Human Rights Commission to urge the government to recognize her as female by issuing her official documents that reflect her lived gender. Her application was pending at time of writing.

In Sri Lanka, transgender rights activists have so far asked to be recognized in the male or female gender with which they identify, as opposed to a third gender. But the underlying principle is the same: Sri Lanka should recognize all citizens according to the gender with which they identify and issue documents that reflect that gender, without medical diagnosis or treatment as a precondition.

|

Acknowledging a Third Gender In October 2015, Bhumika Shrestha, a transgender rights activist in Nepal, became the first Nepali citizen to travel abroad carrying a passport marked “O” for “other” instead of “F” for “female” or M for “male.”[41] In 2007, Nepal’s Supreme Court recognized a third gender category for people who identify as neither male nor female. The court made clear that the ability to obtain documents bearing a third gender marker should be based on “self-feeling,” and not the opinions of medical professionals or courts.[42] In 2013, India’s Supreme Court recognized transgender people constitute a third gender, declaring that this “is not a social or medical issue but a human rights issue.”[43] The court stated that undertaking medical procedures should not be a requirement for legal recognition of gender identity.[44] In 2015, the Delhi High Court reinforced that, “Everyone has a fundamental right to be recognized in their gender” and that “gender identity and sexual orientation are fundamental to the right of self-determination, dignity and freedom.”[45] Similarly, in 2009, the Supreme Court in Pakistan called for a third gender category to be recognized, and in Bangladesh, the cabinet issued a 2013 decree recognizing hijras as their own legal gender.[46] |

Difficult Process

While it is not impossible to change one’s legal gender in Sri Lanka, there is no clear and simple procedure. Dr. Chithramalee de Silva, director of Mental Health at the Ministry of Health, was not aware of any existing standard process by which people may change their legal gender. Dr. de Silva is collaborating with the National Human Rights Commission to develop a gender recognition certificate.[47]

In the absence of a clear and simple procedure, people who want to change their gender do not know if their application will be successful, or even where to begin. As one intersex person said of authorities like the Registrar General’s Department charged with changing documents, “Even the officer doesn’t know what to do.”[48] The situation leaves public officials with unfettered discretion in deciding the requirements and results of applications. As one transgender man in Colombo said, “They can ask for whatever they want.”[49] “It is in the hands of the officer who gets your file,” an intersex person in Jaffna said. “If your officer doesn’t want to give it to you, you’re not going to get it.”[50]

|

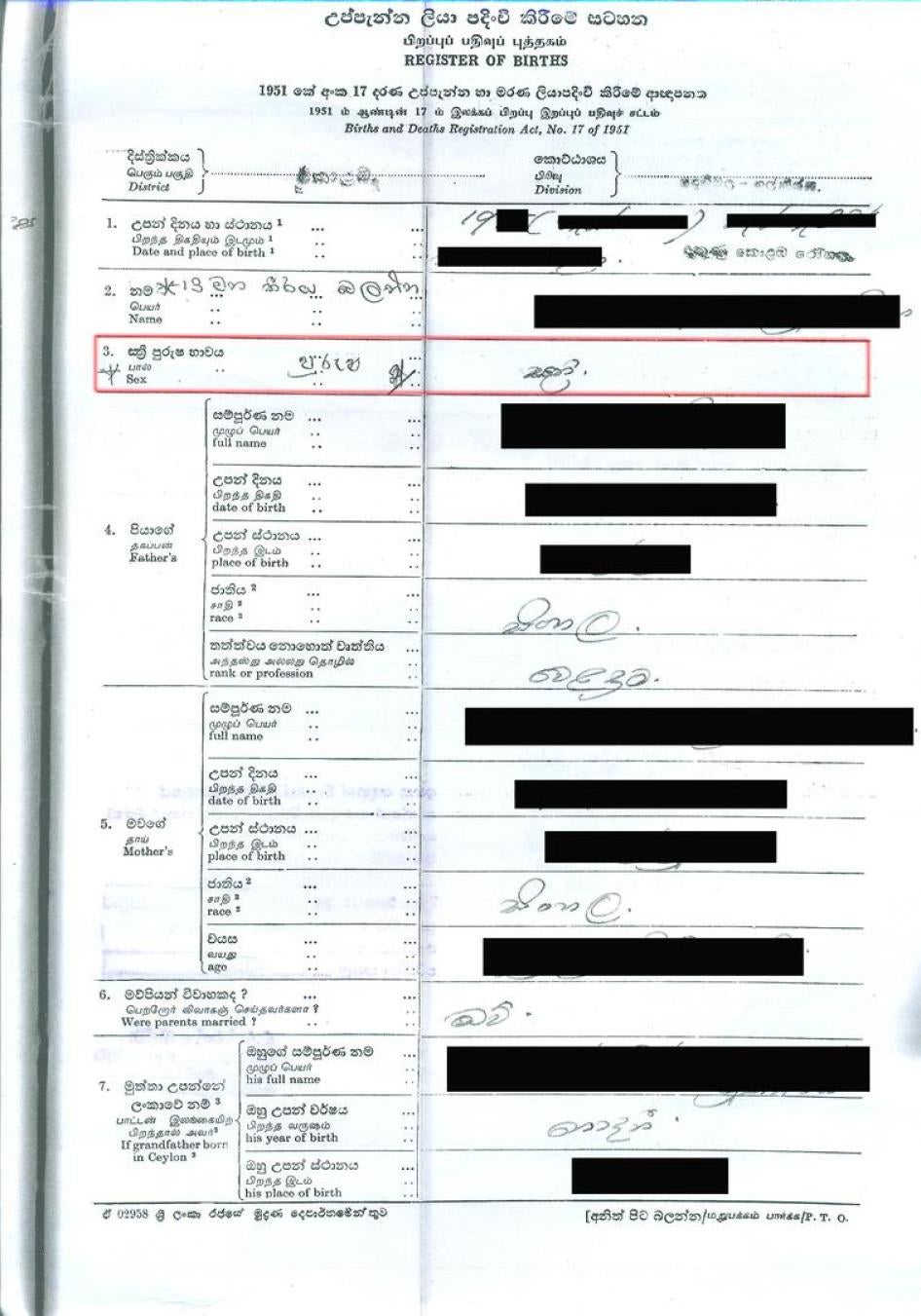

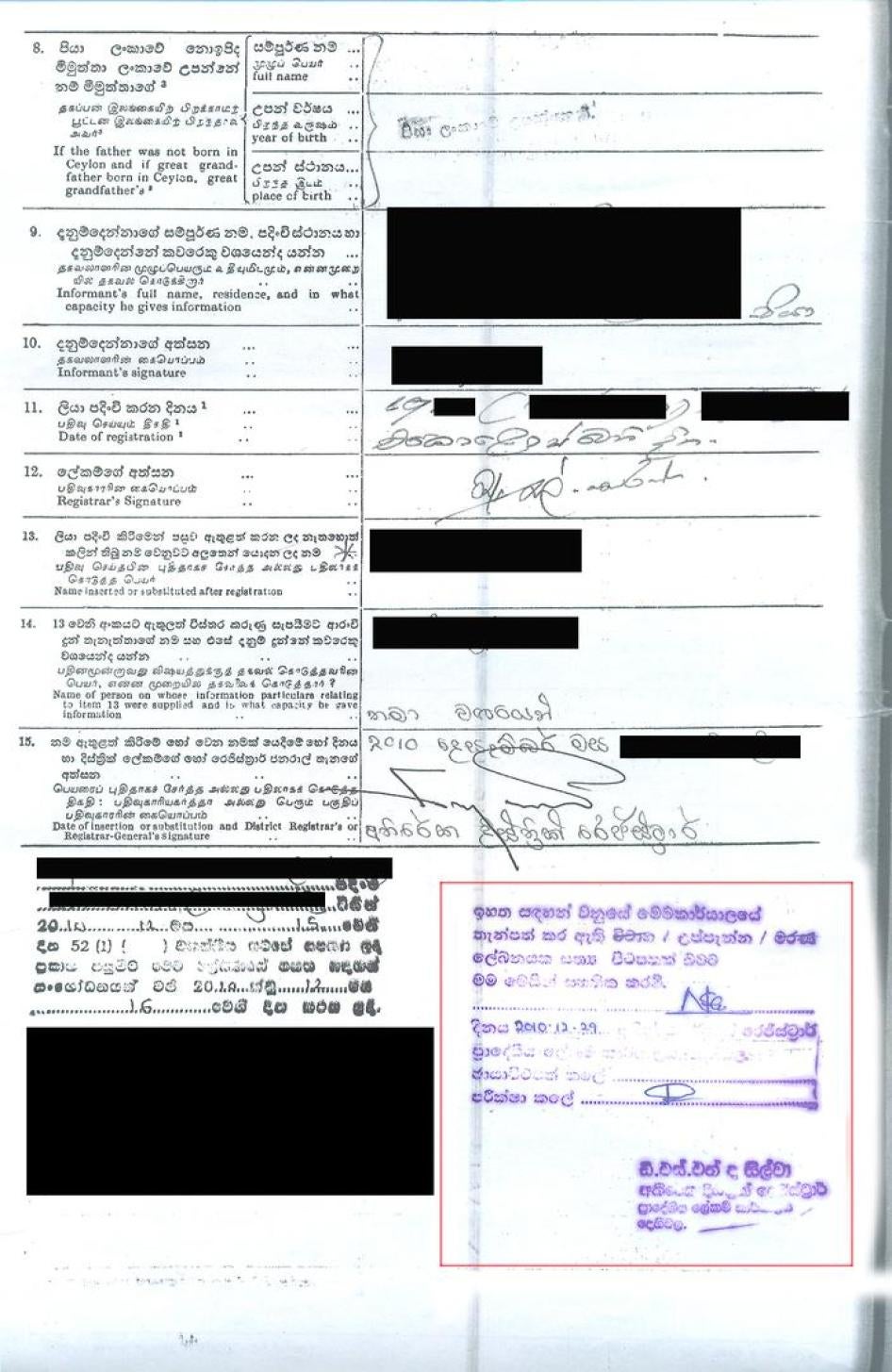

Krishan, a transgender man, told Human Rights Watch that the Registrar General’s Western Zonal office rejected his application to change the gender marker on his birth certificate four times. “Just tell me if you’re a man or woman,” an irritated officer told him.[51] A rejection letter he received from the Registrar General’s office asked him to “take laboratory reports” and “call upon parents on the subject and take verbal evidence.”[52] [See Annex I for a copy of the letter]. In other words, Krishan said, the Registrar General wanted medical documentation and testimony from his parents about how long he has, as he put it, “been like this.”[53] Getting a letter from his parents was “very difficult.”[54] Krishan has a fraught relationship with his family, like many transgender people. “My mother would be happy if I left the country,” he said.[55] |

Other transgender people identified “very onerous”[56] evidentiary requirements for changing their documents—especially having to produce evidence of gender transition, including sex reassignment surgery.

Kavitha, a 27-year-old transgender woman in Jaffna, told Human Rights Watch she had heard anecdotally from other transgender people that she needed evidence of a sex change in order to change her gender on her documents. This would require first getting sex reassignment surgery and then a letter from the surgeon confirming that she is female. Since Kavitha cannot financially afford to get the surgery, “I’m suffering for now,” she said.[57]

Sex reassignment surgery is not accessible to many transgender people in Sri Lanka, and may not be desirable for others. As transgender activist Sathya explained in a media interview, “Most people cannot achieve this due to financial insecurities, social fear, family-related issues and many other reasons.”[58]

Some transgender people reported additional evidentiary requirements. Susan, an intersex person in Colombo who was assigned the male sex at birth, said her district secretarial office asked her to take out an advertisement in a newspaper saying that she would now go by her female name. Along with a paper cutting of the advertisement and letters from doctors indicating that she had undergone sex reassignment surgeries, she had to produce a letter from the grama seveka (village officer) saying that she was a resident of her district and not involved in a crime.[59]

Not only do the requirements for changing documents differ from person to person, the requirements for the same person can change over time. Janitha, who is intersex, has been trying to change her sex (assigned male at birth) on her national identity card. At first, she said, the Department for Registration of Persons asked her to present a psychiatrist’s certificate, and nothing else. But when she submitted the requested certificate, the department asked her for more documents, including her passport and birth certificate that she had lost in a house fire. Janitha said that she felt “disheartened” by the shifting requirements and has given up trying to change her gender on her national identity card: “There are too many complications.”[60]

Dr. Kapila Ranasinghe, a psychiatrist in Colombo, provides a letter to transgender people who seek to change their gender on documents. In spite of the standard form of the letter, public authorities sometimes accept it, sometimes not, he told Human Rights Watch.[61]

Problematic Medical Diagnosis or Treatment Requirements

Requiring medical diagnosis or treatment can make it more difficult for people to obtain documents that reflect their gender. Currently in Sri Lanka, medical professionals act as gatekeepers to people trying to change their legal gender. Fathima, a 25-year-old transgender woman in Colombo, said she has been struggling to change her gender (assigned male at birth) on her birth certificate, national identity card, and school certificate. Her psychiatrist told her to undergo hormone therapy for another year before he would issue her a letter to support her request to change her documents. “There is no one to help me change my documents quickly,” she said.[62]

Susan said that some doctors she dealt with require transgender and intersex women to dress in women’s clothes and be feminine in their looks: “They insist that we put on nail polish and make-up before they put us on hormone therapy. If we do all this and they are satisfied with our looks, then they put us on hormone therapy.”[63] But not every woman—cisgender, transgender, or intersex—wants to wear make-up or nail polish, nor should they be required to do so to be recognized in their gender.

Krishan, a 40-year-old transgender man in Colombo, told Human Rights Watch that the Department for Registration of Persons told him he needed evidence of gender transition in order to change his documents, but his psychiatrist was “scared” to give him hormones while his documents said he was a female. This left him in a terrible bind: he was required to begin hormone therapy before he could change his documents, and at the same time, he needed to change his documents before he could begin hormone therapy. Eventually, he was able to begin hormone therapy with a private doctor who ran a ward in a general hospital.[64]

Gender Recognition Certificate

In March 2015, Sashini, a transgender woman whose application to change her legal gender was rejected by the Registrar General’s Department, brought a complaint to the National Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, followed by two others in January 2016.

Responding to the first complaint, in June 2015, the National Human Rights Commission proposed a gender recognition certificate that would be accepted by all authorities for indicating gender on official documents, including the birth certificate, National Identity Card, and passport. In June 2016, the Ministry of Health mailed a circular to various health services and education institutions setting out guidance on issuing the gender recognition certificate to transgender people. As of July 2016, the National Human Rights Commission was awaiting a response to the proposed certificate from the Registrar General’s Department.[65] [See Annex II for a timeline of the gender recognition certificate.]

The idea of a standardized gender recognition certificate that allows individuals to change all their documents is an important step. But the draft provided to Human Rights Watch falls short of international best practice, which recommends that medical, surgical, or mental health treatment or diagnosis should not be required for legal gender change.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)—an international 700-member strong multidisciplinary professional association aimed at promoting evidence-based care, education, research, advocacy, public policy, and respect in transgender health—has issued a statement on identity recognition that:

[u]rges governments to eliminate unnecessary barriers, and to institute simple and accessible administrative procedures for transgender people to obtain legal recognition of gender, consonant with each individual’s identity, when gender markers on identity documents are considered necessary.[66]

The statement makes clear that “[n]o particular medical, surgical, or mental health treatment or diagnosis” should be required for legal gender change.[67]

Contrary to WPATH’s guidance, Sri Lanka’s draft certificate requires a psychiatrist to certify that a transgender person has been referred to “hormone therapy” and “necessary surgical treatments” and that “the person underwent the gender transformation process.”[68] The psychiatrist must also certify that the person has completed “the social gender role transition as required,”[69] contradicting international best practice because it requires a psychiatric diagnosis, which poses a barrier to transgender people obtaining legal documents that reflect their identity.

As WPATH states: “These legal barriers are harmful to trans people’s health because they make social transition more difficult, put congruent identity documents out of the reach of many, and even contribute to trans people’s vulnerability to discrimination and violence.”[70]

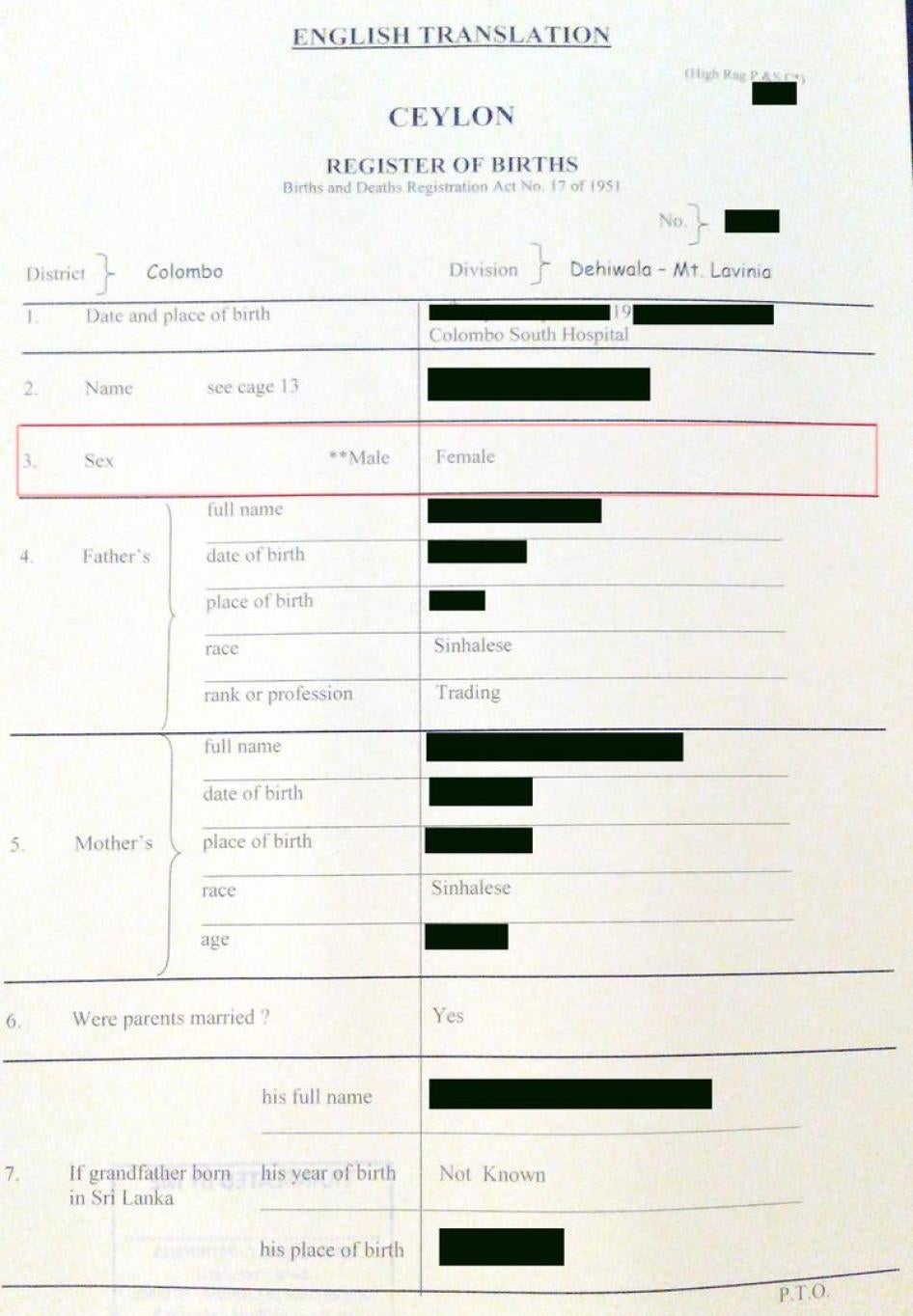

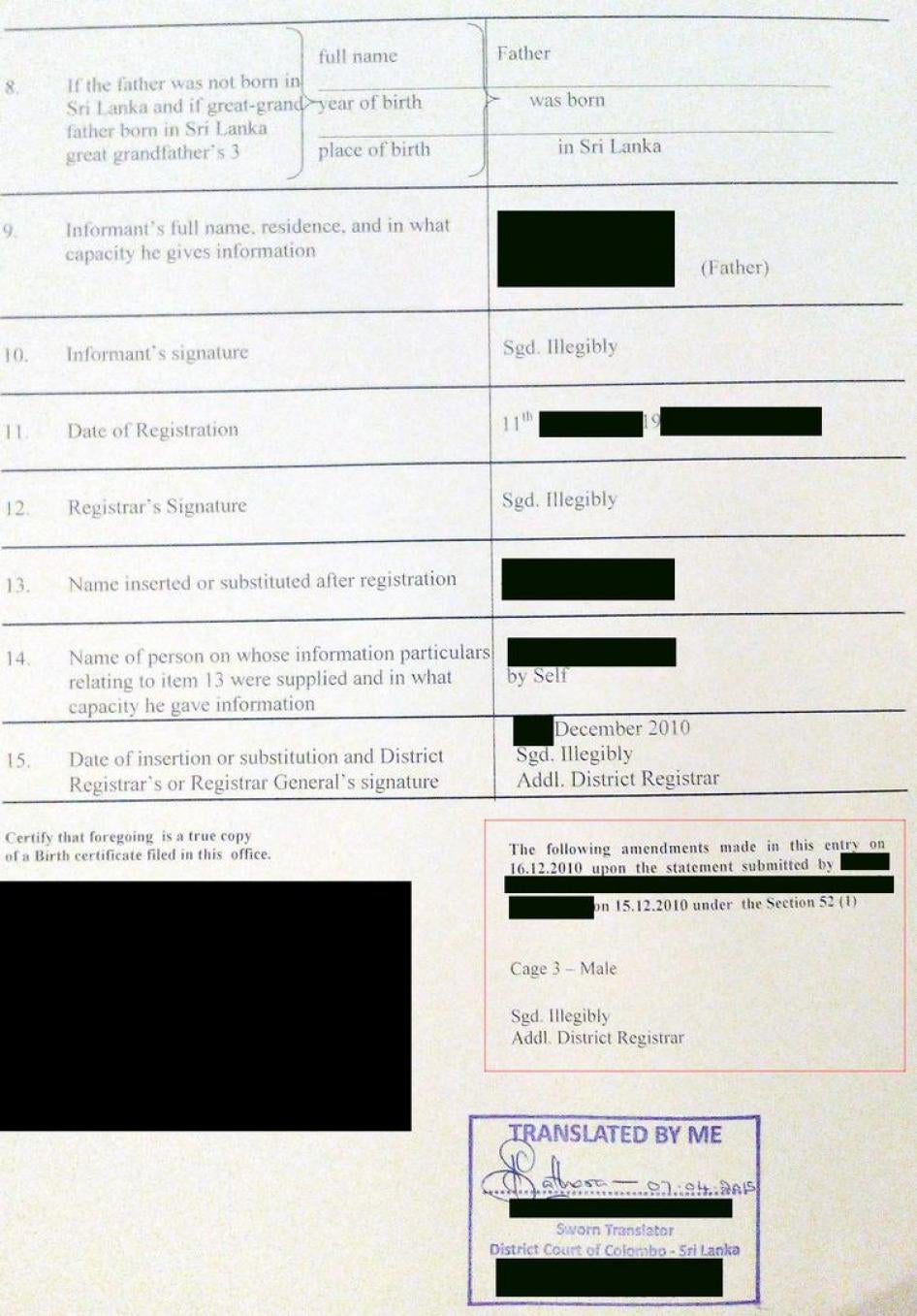

Transgender people who did manage to successfully change their birth certificates told Human Rights Watch that the Registrar General’s Department did not issue them a new certificate. Instead, it amended their birth certificates in such a way that made it obvious that the original gender designation had been changed. As Krishan, a transgender man, explained, “They cut the word ‘male’ and put ‘female.’”[71] [See Annex III for original and translated versions of Krishan’s amended birth certificate.] Susan, an intersex person who had the gender on her birth certificate changed from male to female, stated: “Where it stated male, they put a square mark. On the back under ‘alterations,’ they state the law and that I’ve changed my name and gender.”[72]

Reflecting people’s lived gender in their birth certificates, which can then form the basis for changing their National Identity Card and passport, is an important step. But when the birth certificate is merely amended and not reissued, those who look at it—such as a prospective employer—can tell that a person has changed their legal gender since birth. This in turn may trigger the constant and humiliating scrutiny about gender identity that many interviewees described.

III. Police Abuses

|

The night in 2012 that police raped Adithya, a 42-year-old MSM sex worker in Colombo, began with his arrest as he waited on Colombo’s main thoroughfare, Galle Road, at about 11 p.m. Police took him to Bambalapitiya police station. “They didn’t scold me or speak to me in filth [abusive language],” he said. “They didn’t tell any other officers about me. They took me behind their barracks. One by one, two of them had sex with me. Then they let me go.” Adithya said he did not say anything because he feared being put in jail or taken to court.[73] Other police officers have tried to have anal or oral sex with him, Adithya said. Police officers he encounters at night are often drunk, and seem to think that sex workers crave sex. “They say we keep coming back to do sex work because we can’t get enough sex,” he said. “They want us to have their penis because they say we can’t get enough penis.”[74] Adithya reported being beaten by the police on a number of occasions, sometimes when looking for clients, sometimes when doing nothing illegal. In May 2015, police officers in a jeep stopped to question Adithya while he was waiting for a bus at about 10 p.m., he said. The police searched his bag and found condoms, and said: “Here we have the stuff.” When Adithya tried to explain that “having a condom isn’t illegal” and that he works on HIV prevention with a local organization, including distributing condoms to trans people and MSM, the police officers became aggressive. “You have a good mouth,” one of the younger officers said, and then beat Adithya while others watched, while calling him kariya (sperm dog), ponnaya (faggot), and ponna wesige putha (faggot son of a whore). The two officers warned Adithya to move away from the bus stop or face arrest.[75] Adithya also reported being arrested and harassed by police while he was not engaged in sex work. One time, he was walking on Dickmans Road in Colombo at about 7 p.m. when a police jeep slowed down and an officer asked, “Why are you early today?” When Adithya did not respond, two police officers got out of the jeep, grabbed him, and pushed him in, he said. Once inside, he begged them not to arrest him. He explained that he was shopping, and showed them the clothes he had just bought. Adithya told Human Rights Watch that one officer responded, “You are shopping men,”[76] meaning they assumed that he was a sex worker. When the officers found condoms in Adithya’s bag, one said, “We know what you’re doing.” When they saw money in his wallet, another added: “This must be from your ‘deals.’” The officers took him to Narahenpita police station, wrote a complaint, and released him after he paid a LKR100 (US$0.67) fine, he said.[77] |

Sri Lanka’s police have a long history of committing serious human rights violations with impunity. They have been implicated in arbitrary arrests, torture and other ill-treatment, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and other abuses in both ordinary criminal cases and political cases.[78] During Sri Lanka’s 26-year civil war from 1983 to 2009, Human Rights Watch and other organizations documented cases of police involvement in killings and “disappearances” and an unwillingness to seriously investigate complaints filed by victims’ families.[79]

Human Rights Watch has documented cases in which police have tortured detainees of ordinary crimes such as theft, including using severe beatings, electric shock, suspension from ropes in painful positions, and rubbing chili paste in the genitals and eyes.[80] In May 2016, the UN special rapporteur on torture, Juan Mendez, reported after visiting Sri Lanka that “torture is a common practice carried out in relation to regular criminal investigations in a large majority of cases by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of the police.”[81]

Following the publication of a Human Rights Watch report on police torture, “We Live in Constant Fear”: Lack of Accountability for Police Abuse in Sri Lanka,[82] in November 2015, police claimed to have investigated some cases documented in the report, but there has been little or no action on most of the cases. And even before the election of the Sirisena government, the police had expressed intent to improve their practices with regard to marginalized groups, including transgender people.[83]

LGBTI people arrested based on their gender expression, gender identity, or sexual orientation are typically detained without proper cause or evidence, and consequently are rarely detained for extended periods of time. As a result, they may have less overall exposure to police officials in detention and may experience less abuse than Sri Lankans arrested for other crimes.

Nevertheless, nearly two dozen of the LGBTI people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said they had suffered sexual, physical, or severe verbal abuse by the Sri Lankan police—nearly all of those reporting police abuse being transgender people or men who have sex with men (MSM). More than half of this group said that police had detained them without cause at least once. Sri Lankan nongovernmental organizations, including EQUAL GROUND and Women’s Support Group, have also documented cases of police abuse against LGBTI people and expressed similar concerns.[84]

Targeting the Vulnerable

Several people told Human Rights Watch that LGBTI people’s experience with police depends largely on their gender expression and class background. They suggested that police target for mistreatment people who appear most vulnerable—those who are poor, involved in low-level criminal activity such as drug dealing and sex work, and unconnected to elite society—because they are more likely to get away with abuses. Targeting the most vulnerable may be true more generally corrupt and abusive police.

Some transgender people and MSM who are sex workers told Human Rights Watch that they felt police targeted them. Sakuni, a 36-year-old transgender sex worker in Colombo, has been arrested three times, at least once under the Vagrants’ Ordinance and once for “cheat[ing] by personation.” Each time, she said, she was not engaged in sex work.[85]

Geeth, a 35-year-old gay man in Colombo, said that police target him for arbitrary arrest because he looks “gay” according to Sri Lankan stereotypes. During his most recent arrest in October 2015, Geeth pleaded with the police officers arresting him. “We earn for the day. When you falsely accuse us, we have to spend money on courts, and we lose work that whole day,” he said. “That is not our concern; take it up with the courts,” a police officer allegedly told him.[86]

Maneesha, a 26-year-old lesbian in Colombo, said that a police officer questioned her and her lesbian friend in a public park because they were together and gender non-conforming, both with short hair and dressed in jeans and shirts. To escape police scrutiny, she said, “We pretended that we don’t speak Sinhala. We spoke in English; we acted like we’re from abroad, like we have money.… If we didn’t act like that, we’d be in trouble.” [87]

Neelanga, a 36-year-old lesbian in Colombo, said “class and gender are elements in police abuse; anyone who looks butch is a suspect.”[88] Jake, a 34-year-old bisexual man in Colombo who was questioned by the police along with a partner in 2000, highlighted the “privileges and security” that being middle class affords him. As he reflected: “Police read class into LGBT people, so my experience was much better than most.”[89]

Sexual Abuse

Seven LGBTI people told Human Rights Watch that police officers raped, threatened to rape, sexually assaulted, or sexually harassed them.[90]

Jeewani, a 20 year-old transgender woman from Ambalangoda, told Human Rights Watch that police officers in Colombo had raped her in 2013 when she was 17. She was waiting at a bus stand when two male officers told her to get into a police jeep. They took her to a small police post, where one raped her without a condom while the other waited outside. Forcible anal sex “was so, so painful, I screamed,” she said.[91]

Her friend, Abeeth, a gay man from Ambalangoda, said that in 2014, when he was 17, police officers arrested him and took him to the nearby Karandeniya police station and demanded to have sex with him. Although they threatened to arrest him again, he resisted them.[92] About a year later, one night in May 2015, Abeeth was walking with Jeewani at about 10 p.m. when two officers in a police jeep stopped them. One officer told Abeeth to get in. “He was very aggressive,” Abeeth said, demanding that he, “Come, come, come with me.” The officers took Abeeth to a beach, where one of them raped him. “I was so scared,” he said, “I let him do anything.” He remembered it lasting about 15 minutes. After the officer had finished raping him anally, Abeeth ran. He told Jeewani what had happened but did not report it to the police due to fear of retribution.[93]

Physical Abuse

Several people described police officers physically abusing them.

In addition to the cases of Adithya, Jeewani, and Abeeth described above, Diyana, a 20-year-old transgender woman and a university student in Colombo, told Human Rights Watch that police arrested her twice in 2015 when she had done nothing wrong. Both times, officers physically and verbally abused her during her arrest. [94]

The first arrest took place in January 2015 at the Colombo Fort station at about 7 p.m. Diyana said she was waiting for a bus when she saw five police officers harassing her friend and four other transgender women. Her friend called out to her for help.[95] She said that when one police officer saw this, he came over to Diyana and said, “Oh, you’re one of them.” He grabbed her by her hair, dragged her, and kicked her in the back. Diyana protested. “You can’t abuse me…. You’re violating human rights. How can you do this?” she said. “How dare you speak to me about rules,” he said. The officer wrote a complaint against her, and detained her and the others at the police station.[96] On that occasion, Diyana was able to rely on her family’s contacts to get the police to release her. She also asked for the other transgender women to be released. The police released her friend, but not the others.[97]

Since being assaulted, Diyana has suffered from chronic back pain, and cannot bend without pain, she said.[98]

Diyana’s second arrest took place in May 2015 when she and three friends were returning from a dance around midnight. Near Baseline Road station, five male police officers in a jeep stopped them and told them to get in. When Diyana refused, she said the officers grabbed their hands, forced them into the car, and took them to Borella police station.[99]

Once there, officer called Diyana and her friends ponnaya and asked, “Are you giving your ass to men?” When Diyana said that they had done nothing wrong, one officer raised his hand and tried to hit her, she said. Another officer stepped in. They spent the night in jail in a male cell, without food, water, or a female police officer present.[100]

In the morning, Diyana and her friends were taken to the Maligawatta court, where the police testified to the judge that they were caught in a sexual act, Diyana said. After Diyana and her friends’ lawyer had a conversation with the police’s lawyer, their lawyer advised them that unless they pleaded guilty, they would receive a 14-day jail sentence. Following their lawyer’s advice, they pleaded guilty and each paid a fine of LKR 1,500 (US$10).[101]

Kamal, a 33-year-old gay man in Colombo who does sex work, described being physically abused during each of his four arrests. Police officers pulled and dragged him by his hair, slapped his face, pushed him on the floor, and stomped on him with their shoes, he said. While beating him on one occasion in December 2012, police called him ponnaya and told him not to come to Pettah, a neighborhood in Colombo. “This is a Buddhist country,” they said.[102] “I support my family at home with my earnings,” Kamal said. “Please tell the police in Pettah to stop harassing us.”[103]

Police Responsibility

Personal experiences of police abuse—or even hearing about abuses against others—may contribute to fear and distrust of police among LGBTI people. When that happens, LGBTI people become reluctant to report crimes to the police. As a result, those crimes—including hate crimes committed based on the perceived gender identity or sexual orientation of the victim—may go unreported and unaddressed. This contributes to a climate of impunity, in which private citizens believe that they can engage in homophobic or transphobic violence with no consequences.

Sankavi, a 22-year-old transgender woman in Jaffna who works as a lab assistant, said she would not go to the police with a problem. “The police don’t care because they think we’re prostitutes,” she said.[104]

Kavitha, a 27-year-old transgender woman who owns a shop in Jaffna, said that in July 2010 she was physically and sexually assaulted by drunk men on Beach Road about 7 p.m. They pulled her by her hand, hit her in the face, and stripped off her clothes. Then they forced her onto the ground, tried to put their penises in her mouth, and two men had “thigh sex” with her (where the men placed their penises between her thighs and ejaculated). Kavitha did not report the incident to the police because she felt that they would not help her. “They are the ones who really make fun of us,” she said. “How are they going to help us?”[105]

Fathima, a 25-year-old transgender woman in Colombo who started doing sex work after a tea factory where she worked closed down, said that in 2012 she was beaten by thugs in her village who came to her home, held her down, and cut her hair. She decided not to involve the police, believing “they won’t protect someone like me.”[106]

On another occasion, a group of men chased and beat Fathima and her friends while they were on the street looking for clients. She said that she and her friends ran into the Thalwatta police station and pleaded for protection to no avail. The thugs chased and beat her, she said, causing her to lose consciousness. Her friends escaped. When she regained consciousness, she had on “just bra and panties.” Bystanders took her to Negombo general hospital, which treated her wounds and released her the next day. “What’s the point in telling the police?” Fathima said. “We asked them to save us. They refused to save us.”[107]

Diyana, a 20-year-old trans woman, said she was afraid to complain to police when she was beaten by police officers in Borella because “they wouldn’t do anything about it.”[108] Nithura, a 31-year-old lesbian, feared going to the police when she was being harassed and threatened by her girlfriend’s father. “Their first question would be, ‘Why are you being harassed?’” she said.[109]

Not all encounters with police that LGBTI people reported to Human Rights Watch were negative. In some cases, individual police officers stepped in to protect people from abuse from private citizens and other police officers.

Luwina, a 32-year-old transgender woman in Colombo, told Human Rights Watch that when she went to a musical show in Maharagama with a friend, some teenage boys started harassing her—pulling her hair, pinching her, elbowing her. When she scolded the boys and they did not stop, Luwina complained to a police officer securing the show: “I was born in this condition, and these boys are not allowing me to have fun, so that’s why I’m coming to you.” The officer asked her to identify the boys, and ordered the boys to stop harassing the transgender women: “Don’t do anything to them; they are innocent. Let them enjoy the show.”[110]

When three police officers arrested Fathima, a 25-year-old transgender woman in Colombo, on her way to her parents’ house and threatened to take her to court if she did not have sex with them, the officer in charge of the station (OIC) came to her rescue, she said. The OIC gave her a chance to explain that she had not done anything wrong. The OIC then reprimanded the officers and released Fathima. He gave her his phone number, asking her to call him if she ran into trouble.[111]

In September 2015, Janitha, a 41-year-old intersex person in Colombo, was called to the police station over a personal land dispute. When she showed the plans for the disputed land to the officer-in-charge (OIC), she told Human Rights Watch, he threw them away and said, “I don’t need your plans, you bitch.” He told her to shut up, she said, and called her keri vasi (fucking whore), para vasi (cheap whore), and ponna vasi (faggot whore). “He didn’t give me a chance to talk,” she said. “He kept saying these words.”[112]

After the OIC in Janitha’s private land dispute berated her, another officer from the same police station told her that “injustice had been done” to her and encouraged her to lodge a complaint about the OIC. Encouraged by his words, Janitha did so. The officer to whom Janitha complained assured her that he would talk to the offending OIC. When Janitha returned to the original police station, the OIC respectfully called her “Ms.” and apologized, telling her, “I’ve made a mistake. I’m sorry.”[113]

Police Training

An official dialogue about police treatment of transgender people in Sri Lanka is now emerging—an important first step toward protecting the rights of all LGBTI Sri Lankans.

Ajith Rohana, senior superintendent of police of Colombo-North, told Human Rights Watch that he was aware of concerns that transgender people have expressed about police mistreatment. Specifically, he acknowledged that police have arrested people for loitering in a public place and carrying condoms. He further noted that police occasionally arrested transgender people for “cheating by personation,” which is illegal under section 399 of the Penal Code. When this happened, transgender people were generally taken to a police station for questioning and held there for five to six hours, he said. In addition, some transgender people reported verbal abuse from police officers.[114]

Rohana said that the national police training curriculum has addressed some of these concerns since 2011, initially incorporating them into refresher courses for advanced officers, and now introducing such concerns to new officers.[115] “We are teaching our officers that carrying a condom is not a crime,” he said.[116] He said that the training incorporated some of the concerns of transgender people in 2014, and felt that it has been “very successful.” He noted a significant drop in the number of arrests under the Vagrants’ Ordinance: from 1,755 in 2008 to 472 in 2014, although he did not specify how many of these arrests were of LGBTI people.[117]

Human Rights Watch requested a copy of the police training curriculum and was told that it was “not available.”[118]

Rohana said that “police are not going to make further arrests for being transgender.”[119] He added that “all laws should be tallied with Chapter III of the Sri Lankan Constitution,” which deals with fundamental rights.[120]

The National Human Rights Commission’s Education Division, together with the Family Planning Association, held a meeting in 2015 with transgender people who had expressed concerns about mistreatment by police. In response, the commission proposed guidelines about how police should treat transgender people, which, as of July 2016, were pending submission to the Police Service.[121] The draft guidelines provided to Human Rights Watch call on Sri Lankan police and citizens to treat transgender persons equally and without discrimination and to protect their rights and freedoms.[122]

It is important that the Sri Lankan authorities address transgender peoples’ concerns about police abuse. However, it should be recognized that these concerns are broader and deeper than arbitrary detentions and are not limited to transgender people, but extend to a range of police behavior affecting LGBTI people, as well as others.

IV. Public and Private Sector Discrimination

Transgender people face discrimination in accessing health care, including being labelled mentally ill, extra inquisitiveness and lack of privacy from medical staff, and unwillingness by some medical staff to tend to them. Human Rights Watch also documented several cases of discrimination against people based on their actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity when working or looking for work, or trying to find a place to live. This requires additional research beyond the scope of this report.

Discrimination in Health Care

Sri Lanka has an extensive network of public clinics and hospitals across the island. However, doctors and other medical staff are often unaware of, and insensitive to, the health needs of LGBTI people.

Transgender people, in particular, told Human Rights Watch that medical professionals in Sri Lanka tend to consider them as mentally ill. They reported that very few doctors address transgender health issues such as access to hormones or sex reassignment surgery, and most of them are in large cities, like Colombo and Kandy. Identifying a doctor who is able and willing to work with transgender people is a significant barrier to health, some said.

A transgender man in Colombo said that in his experience there was no privacy in government clinics,[123] so that everyone can hear when doctors examine patients, a concern relevant to all patients, but particularly significant for transgender patients given the humiliation and inquisitiveness to which they are frequently subjected. Worse, he added, doctors and other staff sometimes showed his body to others.[124]

“Being a trans woman, I face so many troubles in the healthcare sector,” said Jeewani, 20, in Ambalangoda. “They just want to know about what happened to me, why I’m growing my hair, why I dress like a woman. They don’t care about my sickness, just these other things.”[125]

Dr. Kapila Ranasinghe, a Colombo psychiatrist, sensed a greater openness from the Ministry of Health about addressing transgender health issues with the change of Sri Lankan government in January 2015. The National Human Rights Commission has also been more proactive since the change, he added. However, Dr. Ranasinghe said it was important to address the social and legal discrimination faced by all LGBTI, not only transgender, people. “All sexual minorities are vulnerable,” he said.[126]

Some LGBTI people reported opting for private clinics and hospitals that are more expensive but where staff treat them with courtesy as paying “customers.” As a result, they must pay for services that would virtually be free in public facilities—services not everyone can afford. “With the stories I hear about public hospitals”—as recounted below—“I’d rather go with a private hospital,” one lesbian in Colombo said.[127]

One doctor in Colombo admitted that all staff at her public clinic were reluctant to treat LGBTI people at first. “Then you start to realize that they are human beings,” she said.[128]

Sex Reassignment Surgery[129]

“I felt like an animal in the zoo.”

—Eshan, a 37-year-old transgender man, Colombo, October 2015

WPATH, the international professional association for transgender health, publishes Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender- Nonconforming People, which are available for free on its website (http://www.wpath.org). In its Standards of Care, WPATH highlights the importance of sex reassignment surgery for many transgender and gender-nonconforming people:

Surgery—particularly genital surgery—is often the last and the most considered step in the treatment process for gender dysphoria. While many transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming individuals find comfort with their gender identity, role, and expression without surgery, for many others surgery is essential and medically necessary to alleviate their gender dysphoria.[130]

Sex reassignment surgery is not accessible to many transgender people in Sri Lanka.

|

Eshan, a transgender man from Kandy, was assigned female at birth and began transitioning into male at age 28. “When I would get my salary, I would separate it into travel fees and doctor fees,” he said.[131] In 2008, Eshan went to the government-run Gampola General Hospital, in Kandy district, to get a hysterectomy. After a gynecologist came to examine him in a male ward, his surgery quickly became the talk of the hospital; by the time he underwent the procedure, the entire hospital staff knew about it, he said. While he lay in bed recovering, staff lifted his clothes to show his body to other patients’ visitors. “I felt like an animal in the zoo,” he said.[132] It was just the start of his humiliation. Next, Eshan went to the government-run Colombo General Hospital for a mastectomy. The doctor he saw admitted and discharged him four times but refused to operate, telling him, “I see you as a girl”—despite the steps Eshan had already taken to transition. The doctor tried to dissuade him from continuing, he said, by telling him that he was a girl, girls are supposed to have breasts, and that he should not cut himself up when he does not have an illness.[133] The doctor eventually performed the mastectomy but it was done poorly; Eshan had to go to a different doctor who completed the operation. During the recovery period, Eshan said there was no gynecologist that he felt he could approach in Kandy.[134] |

Eshan’s ordeal is not unique. After being on a waiting list for six months, Krishan was admitted to a government-run general hospital for his mastectomy. Like Eshan, he was questioned about his gender identity by curious nurses. His surgery was also botched.[135]

Krishan reported that his hysterectomy cost LKR 142,000 (US$1,000) and his mastectomy cost LKR 241,000 ($1,700). Redoing the mastectomy would have cost him another LKR 100,000 ($700). Like other transgender people Human Rights Watch interviewed, Krishan had struggled to find full-time employment; his friends had contributed toward his medical expenses up to that point. Unable to afford another surgery, he did not pursue it. “My nipples are gone,” he said.[136]

“We haven’t learned about these things,” conceded one doctor who works with transgender patients.[137] When patients come in after having had sex reassignment surgery, the doctor said, she has to search the Internet to know if what has been done is correct.

A number of surgeries have been done incorrectly, the doctor said: “In Sri Lanka, doctors are willing to perform the final surgery, but they’re learning through you. Somebody needs to know how to help these people… we don’t.”[138] Dr. Ranasinghe said he had treated a very depressed patient whose neovaginal reconstruction was “horrible looking, painful, infected.”[139]

The cost of a mishandled surgery can be emotional as well as financial. Sathya, a transgender woman, told Human Rights Watch that when surgeries go wrong, there are few options for counseling and no recourse for the transgender person.[140]

Such stories from government hospitals were well-known to transgender people who spoke to Human Rights Watch. Out of fear of discrimination and medical negligence, some said they avoided public hospitals and clinics altogether. Sathya feels she cannot go to a public hospital for regular health checks because “they don’t know about transgender people.”[141] When we interviewed her in October 2015, she said she had not seen any doctor since her sex reassignment surgery in March 2015.[142]

Hormone Replacement Therapy

While WPATH, the international professional association for transgender health, does not endorse a particular feminizing or masculinizing hormone regimen, it strongly recommends that “hormone providers regularly review the literature for new information and use those medications that safely meet individual patient needs with available local resources.”[143]

In Sri Lanka, some transgender people identified the unavailability of hormones and the lack of guidance on hormone replacement as barriers to their health.

Transgender women and health practitioners reported that in the absence of medically prescribed estrogen, prescription oral contraceptives are used for male-to-female hormone replacement therapy. However, oral contraceptives are not suitable for every patient, including those with high blood pressure, one doctor cautioned.[144]

Sakuni, a transgender woman, said that without governmental guidance on or regulation of hormone replacement therapy, doctors can decide how and when to start treatment, “often based on their judgment of how masculine or effeminate the trans person looks.” She said she self-medicated with a cocktail of contraceptive pills in an attempt to accelerate her own transition.[145]

Malith, a transgender man in Colombo who is unemployed, said that after an endocrinologist refused to treat him, a physician started his hormone replacement therapy, which lasted five years.

Barriers to HIV Prevention

Transgender people and MSM have been identified by Sri Lankan health agencies as key populations in addressing the HIV epidemic.[146] In the National HIV/AIDS Policy, the government of Sri Lanka has committed itself to “reducing stigma and discrimination in relation to HIV/AIDS … in order to promote appropriate health care seeking behaviors.”[147]

However, some transgender people and MSM told Human Rights Watch that the experience or fear of stigma and discrimination remained a barrier to them getting tested for HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Kavitha, a transgender woman, said that she and her friends do not trust clinics in Jaffna and instead travel to Colombo (about 400 kilometers away) to get tested for HIV. “We don’t like to be exposed—as transgender people and as people getting HIV tests,” she said.[148] “We believe doctors and nurses would treat us badly, and since we have that fear, we are not going.”[149]

Human Rights Watch heard a range of experiences of people getting HIV and STI tests in government clinics. In positive experiences, people felt treated with respect. In negative experiences, people felt judged for getting tested and discriminated against for being homosexual or gender non-conforming.

Criminalization of same-sex conduct and gender non-conformity, which gives police wide powers to arrest and harass LGBTI people, creates barriers to HIV prevention. Sri Lanka’s National STD/AIDS Control Programme, in a mid-term review of its 2013-2017 strategic plan, notes that “continued criminalization of sexual activity between members of the same sex is likely to marginalize these individuals and promote stigma and discrimination,” and recommends decriminalization.[150]

Dr. Sisira Liyanage, director of the National STD/AIDS Control Programme, told Human Rights Watch that transgender people and MSM have reported being arrested for carrying condoms. Responding to these concerns, his team has developed a three-day training program to educate mid-level police officers not to arrest people with condoms, he said. “The police need to understand that transgender people have rights, too.”[151]

Aversion Therapy

In March 2016 the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), which represents over 200,000 psychiatrists worldwide, stated that it “accepts same-sex orientation as a normal variant of human sexuality,” and that “same-sex sexual orientation, attraction, and behaviour and gender identity are not seen as pathologies.”[152] The WPA also issued a statement declaring so-called “treatments of homosexuality” ineffective, potentially harmful, and unethical.[153]

In Sri Lanka, some families seek “aversion” or “conversion” therapy for their children, including for those above the age of 18—treatments that are aimed at turning them away from homosexuality or gender non-conformity, or toward heterosexuality. Dr. Pinnawala reported seeing a young man whose parents wanted aversion therapy for him. “We can’t have our son being gay; fix this,” she said the parents told her. Dr. Pinnawala refused, trying to explain to the parents that aversion therapy does not work and that it is unethical.[154]

Maneesha said that she went to a psychiatrist at 15 because she wanted to speak with someone about her newly discovered feelings for women. When she revealed to the psychiatrist that she had feelings for women, the psychiatrist offered her a “choice” between conversion therapy or “going ahead with it.”[155] When Maneesha replied that she did not want to have feelings for men, the psychiatrist referred her to Heart2Heart, an organization that works with gay and bisexual men, transgender people, and MSM. “Even when doctors are gay friendly, they think conversion is an option,” Maneesha said.[156]

Mental Health

Although Human Rights Watch could not identify academic studies on the mental health of LGBTI Sri Lankans, studies conducted elsewhere suggest that higher levels of discrimination may adversely impact the mental health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender people.[157]

Dr. Chithramalee de Silva, director of Mental Health at the Ministry of Health, said no government programming currently takes into consideration the special mental health needs of LGBTI people and the sensitivities involved in addressing their concerns when they seek mental health services.[158]

A significant issue that threatens the mental health of LGBTI people is the treatment of homosexuality and gender non-conformity as an illness that can and should be cured. Dr. Pinnawala, a clinical psychologist, told Human Rights Watch that some transgender people she treats have been misdiagnosed as having psychosis. Before they come to her, she said, they do not know that they do not have an illness and do not need medication.[159]

A number of LGBTI people who spoke to Human Rights Watch reported suffering from depression and contemplating or attempting suicide, or knowing people who had done so.

Jeewani, a 20-year-old trans woman in Ambalangoda, said that after her father burned all her female clothes and compelled her to behave like a man, she attempted suicide by overdosing on pills. She was hospitalized and survived, but spent the next year hiding from everybody, she said.[160]

Malith said one of his transgender friends committed suicide because of pressure from his family. “He was overwhelmed, and couldn’t take it anymore,” Malith said, adding that many other transgender friends had also considered suicide—as had he.[161]

Susan, who is intersex, is a devout Christian. For a long time, she had been confused about her sex and sexual orientation. Her parents had raised her as a boy. At 15, she became attracted to men. At 16, she started to develop breasts, and fell in love with a boy. By 17, she felt overwhelmed. “I wrote a letter to God,” she said, “that if he didn’t tell me by the next day if I was a boy or a girl, I’d take my own life.” When a response did not arrive the next day, she drank poison, she said.[162]