Children Detained as National Security Threats

The rise of extremist armed groups such as the Islamic State and Boko Haram has brought renewed attention to the plight of children—both as victims of abuses, and as fighters and militants. All too often, the concern and assistance governments offer abuse victims does not extend to those children caught up on the wrong side of the law or front line.

Human Rights Watch field research around the world increasingly finds that in countries embroiled in civil strife or armed conflict, state security forces arrest and detain children for reasons of “national security.” Often empowered by new counterterrorism legislation, they apprehend children who are linked to non-state armed groups or who pose other perceived security threats, and often hold them without charge or trial for months or even years. Their treatment and conditions of detention frequently violate international legal standards.

Since 2011, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has repeatedly raised concerns regarding the detention of children who are perceived to be a threat to national security, suspected of participating in violent activity, or alleged to belong to armed groups. In 2014, he reported that such detention took place in 17 of the 23 situations of armed conflict or concern covered by his annual report on children and armed conflict.[1] In countries including Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel, Nigeria, Somalia, and Syria, hundreds of children may be detained at any given time for alleged conflict-related offenses.

Many children are detained on the basis of groundless suspicion, flimsy evidence, or broad security sweeps. Some are detained because of alleged terrorist activities by family members. They are often denied access to lawyers and relatives, and the opportunity to challenge the basis of their detention before a judge. Many have been subjected to coercive interrogations and torture, and in places like Syria, an unknown number have died in custody.

Conditions of detention are frequently appalling, with grossly inadequate food or medical care. Children often share overcrowded cells with unrelated adults, putting them at additional risk of physical and sexual violence.

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has urged countries to avoid bringing criminal proceedings against children within the military justice system, but some countries allow for the detention of children by military authorities and prosecution of children before military courts even when civilian courts are functioning. Military courts typically do not have provisions for alleged juvenile offenders.

Security forces have carried out torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment against children to elicit confessions, extract intelligence information, or as punishment. Former child detainees report being subject to beatings, electric shocks, prolonged stress positions, forced nudity, rape, and threats of execution. In some countries a significant proportion of detained children report such abuse. As discussed below, in some circumstances, security forces may be more likely to torture children than adults.

The impact of security-related detention on children can be profound. Children are separated from their families and communities, and typically denied access to education, leaving them further behind their peers once released. In cases of indefinite detention, with no knowledge of when they might be released, children may experience depression and despair. Detention with adults also offers more opportunities to learn criminal behavior from older detainees. Large-scale research studies in criminal justice have found that children detained with adults are significantly more likely to engage in future criminal activity than children held with their peers.[2] In general, juvenile justice research finds that children who have been subjected to detention end up with lower educational achievement, lower rates of employment, higher suicide rates, and higher re-arrest rates than peers who have committed offenses but are placed in community-based alternative programs.[3]

During armed conflict and situations of extremist violence, children who are ill-treated in detention may easily become alienated and seek retaliation by joining armed groups. The UN secretary-general has said that depriving children of their liberty because of their association with armed groups “is contrary not only to the best interests of the child, but also to the interests of society as a whole,” and notes that such detention can lead to the creation of community grievances.[4] When children who have no association with armed groups perceive that they may be subject to detention based on mere suspicion of involvement, they may be more likely to join such groups, seeking protection. Rather than reducing threats, the practice of detaining children may actually increase them.

International human rights and humanitarian law provide special protections for children during peacetime and situations of armed conflict. Children who have committed illegal acts need to be treated in accordance with international juvenile justice standards, which emphasize alternatives to detention, and prioritize the rehabilitation and social reintegration of the child. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) states that, regardless of the circumstances, the arrest, detention, or imprisonment of a child should be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.[5]

International law recognizes the recruitment of anyone under 18 by armed groups as a violation of children’s rights, and stress that child soldiers should be treated primarily as victims, with a focus on their rehabilitation and reintegration into civilian life, including those responsible for war crimes.[6] The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict obligates countries to provide children who have been illegally recruited and used as child soldiers “all appropriate assistance for their physical and psychological recovery and their social reintegration.”[7]

The United Nations has often played an important role in protecting children during armed conflict. In some situations it has advocated successfully for the release of children or negotiated protocols to ensure the transfer of children from detention centers to child protection agencies that can assist in their rehabilitation and reintegration into society. In far too many cases around the world, however, detention remains the norm.

The following country discussions highlight recent patterns in the detention and treatment of children for alleged conflict-related and other national security offenses. The cases cited are not exhaustive. Other countries also routinely detain children as perceived security threats. Somalia, for example, detained over 1,000 children in 2013, many suspected of belonging to the Islamist armed group Al-Shabaab.[8] The UN secretary-general has also highlighted concerns regarding the detention of children in Mali, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sudan, Thailand, and Yemen.

Afghanistan

Since January 2015, Afghan security forces have detained hundreds of children on suspicion of being Taliban fighters, attempting suicide attacks, manufacturing or placing improvised explosive devices (IEDs), or otherwise assisting opposition armed groups. According to the Ministry of Justice, 214 boys were detained in juvenile rehabilitation centers on national security-related charges as of December 2015.[9]

The overall number of children in detention for security-related charges may be significantly higher. Afghanistan maintains over 200 detention facilities run by various entities, including the Afghan National Police, the National Directorate of Security, and the Afghan National Army. For example, the Parwan detention facility, under the authority of the Ministry of Defense, held 166 detainees arrested as children for security-related offenses in 2015, including 53 still under age 18.[10] According to government figures, a total of 7,555 individuals were held in Afghan detention facilities or prisons for alleged conflict-related offenses in October 2014, nearly four times the number in 2011. Random interviews conducted by the UN in dozens of these facilities suggest that up to 13 percent of these detainees—more than 900 individuals—may be children under the age of 18.[11]

Torture is routine in many Afghan detention facilities. The UN found that of 790 detainees randomly interviewed in 2013 and 2014, 35 percent provided credible and reliable accounts of torture or ill-treatment. The detainees described over a dozen methods of torture, including prolonged and severe beating with cables, pipes, hoses or wooden sticks (including on the soles of the feet), punching, hitting and kicking (including jumping on the detainee’s body), twisting of genitals (including with a wrench-like device), and threats of execution and sexual assault. Detainees also reported suspension, electric shocks, being forced to stand for prolonged periods (including in extremely hot or cold temperatures), being forced to drink excessive amounts of water, and being denied food, water, and prayer time.[12]

Afghan security forces may subject children to torture more frequently than adults. The UN’s 2013-2014 interviews found that 42 percent of the children interviewed provided credible accounts of torture or ill-treatment, 7 percent higher than for adults.[13] Similarly, random interviews conducted by the UN between October 2010 and August 2011 found that 46 percent of all detainees reported torture or ill-treatment, while 62 percent of detained children did so.[14]

Afghan security forces typically use torture to extract confessions or other information. Detainees reported that if they refused to confess to the crime they were accused of, or provide the information interrogators wanted, authorities would vary the methods of torture to escalate the levels of pain. Most of the detainees who said they were tortured reported that they eventually made a confession to stop the abuse.[15]

Impunity for members of the security forces who are responsible for torture and other ill-treatment was also the norm. In February 2013, a boy reported that Afghan National Police in Kandahar raped him while he was in detention. The case was referred for investigation to the same authorities that were alleged to have committed the rape. The victim withdrew his allegation, later saying that he had done so after members of the police threatened him.[16] In 2013 and 2014, the UN found only one case where security force personnel were prosecuted for torture of detainees. The two officials involved were each sentenced to eight months’ imprisonment.[17]

The Constitution of Afghanistan and the 2014 Criminal Procedure Code include due process guarantees intended to protect detainees from the use of torture. However, these protections are often disregarded. According to the UN, judges and prosecutors routinely ignore legal prohibitions against using evidence gained through torture for prosecution, and deny detainees their right to mandatory access to defense counsel.[18] A September 2015 presidential decree further undercut protections by amending the Criminal Procedure Code to permit indefinite detention of security suspects without trial. Under the amended code, Afghan authorities may detain for a renewable one-year period anyone suspected of “crimes against internal or external security,” or believed “likely to commit such a crime.”[19]

Democratic Republic of Congo

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), security forces have arrested and detained hundreds of children suspected of association with armed groups. According to the UN, Congolese armed forces arrested and detained at least 257 children during 2013 and 2014. Forty percent of the children interviewed by the UN said they had been subjected to ill-treatment during their detention. Officials released the children only after advocacy by the UN.

In December 2015, Human Rights Watch interviewed 29 children detained in appalling conditions in a military prison in Angenga, northwest DRC.[20] Congolese authorities alleged the boys were members of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a rebel armed group, though none had been formally charged with any crime. Seventeen of the boys told Human Rights Watch they had never been affiliated with the FDLR, while others said they had belonged to the group, but had demobilized months or years previously and reintegrated into civilian life. Only two children said they were active FDLR fighters at the time they were apprehended. The commander of the Congolese army regiment who carried out the arrests denied that children or civilians were among those detained at Angenga and claimed all detainees were FDLR fighters “captured on the front lines.”[21]

One 15-year-old boy told Human Rights Watch:

I was never with the FDLR. One day, I was on my way to the market to buy some things. On my way I ran into Congolese army soldiers, and they arrested me…. They transferred me to Bukavu, then Goma, and finally to Angenga. I don’t know what they want from me. Maybe they just want to say they arrested FDLR. I don’t know.[22]

Another 16-year-old whom the FDLR forcibly recruited managed to escape two months later and surrender to the FARDC. “I handed myself over to the Congolese army in Kitchanga so the FDLR wouldn’t find me,” he said. “They put me in prison and now I’m in Angenga.”[23]

Some of the children, all boys between 15 and 17, had been held for more than a year. None had access to lawyers. They were co-mingled with adult detainees during the day, and had little access to food, clean water, or medical care. Because Human Rights Watch was able to interview only a small number of the 750 detainees at Angenga prison, we believe the actual number of children detained is likely much higher than the 29 interviewed.[24] Several weeks after Human Rights Watch publicized the children’s detention, the government and the UN in a joint mission removed nearly all of the children.

Iraq

Iraqi security forces have detained children on suspicion of armed activity, including association with the armed extremist group Islamic State (also known as ISIS). Iraq’s 2005 Anti-Terrorism Law permits the death penalty for “those who commit … terrorist acts,” and “all those who enable terrorists to commit these crimes.”[25] According to the UN, at least 314 children, including 58 girls, had been charged or convicted of terrorism-related charges under the law and were being held in detention facilities as of December 2015.[26] Some had been detained for more than three years.

Security authorities commonly hold suspects, particularly terrorism suspects, incommunicado for weeks or months following arrest. Detainees have no access to lawyers or their family, and are cut off from the outside world in a detention system rife with corruption.[27] In cases in which the government provides no information about the fate or whereabouts of those detained, it amounts to a forced disappearance that violates international law.

Iraqi security forces also arrest and detain women and children for alleged terrorist activities by male family members, without evidence of their own wrongdoing. Arresting family members because of their relationships to suspects, without evidence they have committed a crime, violates international law and amounts to collective punishment.

For example, in February 2013, Human Rights Watch interviewed two girls, ages 11 and 12, who were held at the Karrada juvenile detention center in Baghdad under suspicion of terrorism. They were arrested in November 2012 when federal police broke into 11 homes in the town of al-Taji, 20 kilometers north of Baghdad, and rounded up 11 women and 29 children. The police held the group overnight, and the next day took 10 women and the 2 girls to the Kazhimiyya police station. Some of the women said that police tortured each detainee with electric shocks and placed plastic bags over their heads until they began to suffocate, seeking information about their male family members.[28]

The two girls were detained for six weeks at the police station, and then moved to the juvenile detention center. Both girls said that they had not seen a lawyer or their parents during their detention, and had not been told of charges against them. A senior official told Human Rights Watch that the 11-year-old was charged with “covering up” terrorist acts, and was accused of taking documents from a locker and hiding them in her clothes. The women who had been arrested at the same time were also charged with terrorism for “covering up” for their husbands.[29]

In some cases, authorities have detained young children and infants with their mothers. They have subjected family members to threats and physical abuse, including severe beatings, burns with cigarettes, and electric shocks, to coerce confessions implicating husbands, brothers, or other male family members.

For example, in September 2012, federal police arrested a woman with her three young children, ages 6, 4, and 5 months. Her 6-year-old son told his aunt that he saw police blindfold, beat, and electrocute his mother, as they sought information about his father. “She started to turn around and around and shake from the electricity,” he told her.[30] The children were detained for 40 days before they were released.

In September 2012, security forces arrested a couple from their car, together with their 14-year-old daughter with a disability, and 10-year-old son. The couple’s 17-year-old son was arrested later that day. The 10-year-old later told his grandmother that when the security forces arrested him with his parents, they held his head near a car tire and threatened to run him over if he did not tell them “where they hid the weapons.” The father died in detention, but police continued to detain the mother and her three children for a total of three months at the Qanaa General Security office in Baghdad. The daughter, who is paralyzed, told her grandmother that “when the human rights groups would come to the prison, they would take us and hide us in the bathrooms.”[31]

In a case documented by Amnesty International, security forces detained 13-year-old Mundhir al-Bilawi and his father, Samir Naji ‘Awda al-Bilawi, at a checkpoint in Ramadi in September 2012. Mundhir said that security forces took them first to a local police station where they were both assaulted, and then to the Directorate of Counter-Crime in Ramadi, where they were both tortured with electric shocks. Mundhir said that interrogators forced him to implicate his father in terrorism, including in front of an investigating judge.[32]

Iraqi security forces have also raped and sexually assaulted girls along with women in detention. Even girls who have not been raped experience the stigma resulting from being raped, because of the societal presumption that female detainees have been sexually assaulted.[33]

Pro-government militias have also detained children. In March and April 2015, after the Iraqi government dislodged ISIS forces from the city of Tikrit and other areas northeast of Baghdad, pro-government militias looted, torched, and blew up hundreds of civilian houses in the area and unlawfully detained approximately 200 men and boys, witnesses told Human Rights Watch. At least 160 were still unaccounted for in September 2015 and feared to have been forcibly disappeared.[34]

In January 2016, Human Rights Watch spoke to three Sunni Arab women in northern Iraq who had fled ISIS. They said that in November 2015, the military of the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq, known as the Peshmerga, had detained 10 of their close male relatives, including a 16 and a 17-year-old, for alleged links to ISIS. The men and boys were held without charge, some for more than a month. One woman said her husband called her from a Kirkuk prison, and said that internal security forces had tortured him and their 17-year-old son during interrogation by pulling out their fingernails.[35]

In March 2015, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child expressed serious concerns regarding the large number of children indicted or convicted of terrorism-related charges in Iraq, and reports of ill-treatment and torture during their detention. The committee said that children detained under terrorism charges were reportedly held in extralegal facilities, including those run by the Iraqi National Intelligence Service, and that children who were relatives of terrorism suspects were also subject to wrongful arrest, held without charge, or charged with covering up terrorist acts. The committee also found that children’s families were not notified of the child’s detention, and that when detainees turned 18, they were transferred to death row.[36] Human Rights Watch learned several years ago of the impending execution of a Yemeni child in custody that was only stopped by diplomatic intervention at the highest level of the Iraqi government.

In September 2015, the Committee against Torture also expressed deep concern at reports suggesting a consistent pattern “whereby alleged terrorists and other high-security suspects, including minors, are arrested without any warrant, detained incommunicado or held in secret detention centers for extended periods of time, during which they are severely tortured in order to extract confessions.”[37]

Israel/Palestine

Israel prosecutes between 500 and 700 Palestinian children in military courts each year, charging the vast majority with throwing stones at Israeli soldiers or settlers in the occupied West Bank. The Israeli military court system tries Palestinian children from the West Bank, with the exception of East Jerusalem, for security-related offenses. As of 2009, children are tried in a designated juvenile military court, whose judges receive special training. The military justice system, however, does not focus on rehabilitation and social reintegration for children, as required under international law.[38]

In 2015, Israel held an average of 220 Palestinian children in custody each month, an increase of 10 percent over the previous year, according to data provided by the Israel Prison Service.[39] As violence in the West Bank increased in late 2015, the number of Palestinian children in Israeli prisons increased to the highest level since 2009. A total of 422 Palestinian children were in the Israeli prison system at the end 2015, including 116 children between the ages of 12 and 15.[40] In 2015, the Israeli military also placed six Palestinian children under administrative detention, which allows for prolonged detention without charge or trial. This is the first time the measure has been used against Palestinians under 18 in nearly four years.[41]

Large numbers of former child detainees have reported ill-treatment by Israeli security forces, including beatings, kicking, strip-searches, verbal abuse, and threats of sexual violence.[42] In 2013 and 2014, the UN obtained affidavits from over 200 Palestinian children regarding treatment by Israeli security forces during arrest, transfer, interrogation, or detention. Of 208 affidavits, 171 children said they were subject to physical violence and 168 said they were not informed of their rights to a lawyer or to remain silent during interrogation.[43] Fifteen formal complaints were lodged with Israeli authorities regarding abuses against Palestinian children during arrest, interrogation, and detention in 2013, but none resulted in dismissal, indictment, or arrest of the security force personnel involved.[44]

In several cases investigated by Human Rights Watch, children reported that police officers had hit and kicked them in custody, and forced them to spend hours outside in the cold in the early morning and at night, handcuffed to chairs in police compounds. One 14-year-old boy told Human Rights Watch that his interrogators threated to revoke his parents’ residency rights in East Jerusalem and told him to sign papers written in Hebrew, a language he could not read. When he asked what the papers said, he was told it was a statement declaring that he had not been beaten.[45] Another boy, 16, said he was arrested in November 2015 at a friend’s home by soldiers who accused him of having a knife. He was blindfolded, handcuffed, and taken to a police station for interrogation, and then to a military compound, where he said six or seven soldiers forced him onto the ground and started hitting and kicking him. “I was hit on my back and legs, with kicks and blows to my head,” he told Human Rights Watch. “I don’t know how long it lasted, but it was painful and the time passed slowly.” He was released six days later, without charge, after DNA testing failed to link him to a knife that had been found.[46]

Between 2012 and 2015, Defense for Children International-Palestine (DCI-Palestine) documented 66 cases of Palestinian children subjected to solitary confinement. The longest period of time spent in solitary was 45 days, and the average was 13 days. Israeli security forces used solitary confinement almost exclusively before trial, possibly to obtain confessions and intelligence. DCI-Palestine reported that in 60 out of the 66 cases it documented, children held in solitary confinement provided a confession.[47]

The primary military order relevant to the arrest and detention of Palestinian children, Military Order 1651, was adopted in November 2009. This order gives Israeli military courts jurisdiction over any person 12 years and older, and allows authorities to arrest and imprison Palestinians for “security offenses,” such as causing death, assault, personal injury or property damage, kidnapping, and harming a soldier. [48]

Throwing stones—the charge against the vast majority of Palestinian children detained in Israeli military detention—can carry penalties of up to 20 years in prison, depending on the age of the child, plus fines. Many children maintain their innocence, but plead guilty in order to avoid prolonged detention before trial. Most receive plea deals of less than 12 months, and are ordered to pay fines averaging US$400. If families are unable to pay this amount, the child is detained longer.[49]

Israel’s Youth Law and military orders applicable in the West Bank require police to notify parents of a child’s arrest and to allow the child to consult with a lawyer before interrogation. The Youth Law also entitles children to have a parent present during interrogation. The law formally applies to Israel and East Jerusalem, but Israeli military authorities have told Human Rights Watch they also implement its provisions in the West Bank.

In practice, the provisions of the Youth Law are often disregarded. A lawyer who has represented hundreds of children in 2015 and 2016 told Human Rights Watch that senior police officers can grant interrogators an order allowing interrogations without a child’s parents present. He said, “This order, as far as we see, is used against Palestinian children in political cases only, and it gives the interrogators the freedom to harass, scream, threaten the children and push them to confess to crimes they have not committed out of fear.”[50]

In July 2013, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child found that Palestinian children arrested by Israeli forces were systematically subjected to degrading treatment, and often torture, and that Israel had “fully disregarded” previous recommendations to comply with international law. The committee urged Israel to “dismantle the institutionalized system of detention” and open an immediate independent inquiry into all alleged cases of torture and ill-treatment of Palestinian children.[51]

Nigeria

Since it began its attacks in 2009, the extremist armed group Boko Haram has recruited hundreds, and possibly thousands, of boys and girls for its military operations, used dozens of children—mostly girls—as suicide bombers, and launched increasingly brutal attacks against civilians. Between 2009 and 2015, Boko Haram’s attacks destroyed more than 910 schools and forced at least 1,500 more to close. The group has abducted more than 2,000 civilians, many of them women and girls, including large groups of students.

In its efforts to counter Boko Haram, the Nigerian government has rounded up and detained thousands of individuals—mostly men and boys—for suspected participation in the group, or support for its activity. Arrests are often based on flimsy evidence provided by unreliable informants. Military officers said that informants have provided false information simply to get paid.[52] Security forces, including members of the government-allied Civilian Joint Task Force, also conduct large sweeps, arresting people en masse. According to Amnesty International, since 2009, Nigerian military forces have arbitrarily arrested at least 20,000 people, including children as young as 9.[53]

In May 2013, then-President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency in three northeast states. He issued regulations allowing him to order the detention of any person, whether in the emergency area or elsewhere,[54] and stated that the armed forces and other security agencies involved in countering Boko Haram “have orders to take all necessary action... to put an end to the impunity of insurgents and terrorists."[55] A witness from Borno state told the Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict:

As soon as the insurgents attack an area, the military will come and start arresting men. They arrest old, middle, and even young ones but only men.... Once you hear a gunshot you run because if the military comes they will arrest every person.[56]

Local residents told Human Rights Watch that soldiers would pound on doors at 5 a.m., ordering young males out of their homes. One woman said that eight soldiers ordered her 10-year-old son to lie down, beat him with batons and tied him up, piled him face down with 22 others in an open-back vehicle, and then drove them away. Another woman described how security forces had arrested her seven sons, ages 12 to 30, as they gathered in front of their home for evening prayers. [57]

Security forces hold the majority of detainees in barracks and detention centers in Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa states. Former detainees held in the Giwa barracks and in military detention centers in Damaturu described horrific conditions. They said the facilities were extremely overcrowded, with hundreds of detainees packed into small cells. Because of lack of space, former detainees said they had to take turns sleeping or even sitting on the floor. They said they received a small amount of rice once a day and had no access to medical assistance, even for life-threatening conditions.[58] Torture and ill-treatment was common. A former child detainee in Yobe state said he was among a group of 50 people, mostly between ages 13 and 19, who were arrested in March 2013 and held in Sector Alpha (also known as “Guantanamo”) in Damaturu. He said that while he was in custody, security forces beat him with gun butts, batons, and machetes, forced to him to walk and roll over broken bottles, and poured melted plastic on his body.[59]

Former detainees have reported that large numbers of detainees have died as a result of dehydration, starvation, illness, and torture, and that many others were executed.[60] Amnesty International estimates that more than 7,000 men and boys died in detention between March 2011 and June 2015, based on visits to mortuaries, internal military reports, statistics recorded by local human rights activists and interviews with witnesses, victims, former detainees, hospital staff, mortuary personnel and military sources.[61] In June 2013 alone, more than 1,400 corpses were delivered from the Giwa barracks to one of the mortuaries in Maiduguri.[62]

Authorities arrest many children on their own, and also detain young children and babies together with their mothers. Between February and May 2016, 11 children under the age of 6, including four babies, died in Giwa barracks due to disease, hunger, and dehydration, according to Amnesty International. One witness said that they had seen the bodies of eight dead children including a 5-month-old baby. In February 2016, the military released 275 people who it said had been wrongfully held on suspicion of being involved in terrorist or insurgent activities. Among the 275 were 72 children, including 50 who had been arrested and detained with their mothers.[63]

Nigeria’s Terrorism Prevention Act, adopted in 2012 and amended in 2013, gives the military wide powers to arrest and detain people. Section 27 allows the arrest and detention of a person “found on any premises or places or in any conveyance” by the “relevant law enforcement officer of any agency until the completion of the search or investigation under the provisions of this act.” The act appears to allow for indefinite detention, allowing the court to grant an order for the detention of a suspect for 90 days, and to renew the order for additional 90-day periods until “the conclusion of investigation and prosecution.” Under the act, anyone who engages in, attempts, threatens or assists an act of terrorism, or “omits to do anything that is reasonably necessary to prevent an act of terrorism” may be guilty under the act and subject to penalties including up to life imprisonment.[64] Children are not excluded from the act.

While some detainees have been released, many remain unaccounted for. Very few have faced trial. Between December 2010 and 2015, only 24 court cases were concluded, involving fewer than 110 people.[65] Amnesty International estimated that in May 2016, at least 120 children remained in Giwa barracks, making up at least 10 percent of the barrack’s detained population.[66] According to a credible source, as of early 2016, hundreds of children were still detained, many having been held for months or even years.[67]

Syria

Since the beginning of the Syrian conflict in 2011, Syrian authorities have detained tens of thousands of people in dozens of detention centers scattered across the country. According to the Violations Documentation Center in Syria, at least 1,433 of these detainees have been children.[68] In cases documented by Human Rights Watch, detained children were usually between the ages of 13 and 17, but some witnesses and defectors have reported seeing boys as young as 8 in Syrian detention centers.[69]

During 2011, 2012, and parts of 2013, intelligence services, often assisted by the military, apprehended people following anti-government protests in large-scale house-to-house “sweep” operations and at checkpoints on roads. Defectors from the Syrian military told Human Rights Watch that anyone over 14 was liable to be arrested and detained. In 2011, a lieutenant colonel deployed in Douma with the 106th Brigade of the Presidential Guard told Human Rights Watch that his brigade arrested about 50 people, any male between ages 15 and 50, at his checkpoint after each Friday protest.[70] Security forces also targeted specific activists for arrest, and if they were not at home, arrested family members, including children, instead.

A former officer with the 46th Special Forces Regiment said that 10 to 30 detainees were brought to his camp in Idlib every evening, lined up, blindfolded, put on their knees, and beaten. He said, “Most of them were between 16 and 18 years old, but there were some kids that looked much younger.” He asked two boys who looked particularly young when they were born, and discovered one was 13. The former officer said, “I think many kids were caught because they didn’t know how to escape.”[71]

In 2011 and 2012, Human Rights Watch conducted 200 interviews with former detainees, including children, and defectors from the Syrian military and intelligence agencies. Almost all the former detainees interviewed said they had been subjected to torture or witnessed the torture of others. Syrian security forces used a broad range of torture methods, including prolonged beatings, often with objects such as batons and wires, holding the detainees in painful stress positions for long periods, electrical shocks administered with stun guns and electric batons, use of improvised metal and wooden “racks,” burning with car battery acid, sexual assault and humiliation, the removal of fingernails, and mock execution.[72] Of the cases Human Rights Watch documented, 27 involved children. One 13-year-old boy, “Hossam,” said he had been tortured for three days at a military facility near Tal Kalakh:

Every so often they would open our cell door and yell at us and beat us. They said, ‘You pigs, you want freedom?’ They interrogated me by myself. They asked, ‘Who is your god?’ And I said, ‘Allah.’ Then they electrocuted me on my stomach, with a prod. I fell unconscious. When they interrogated me the second time, they beat me and electrocuted me again. The third time they had some pliers, and they pulled out my toenail. They said, ‘Remember this saying, always keep it in mind: We take both kids and adults, and we kill them both.’ I started to cry, and they returned me to the cell.[73]

Former detainees described appalling detention conditions, with grossly overcrowded cells, where at times detainees could only sleep in turns. They said they received very little food. One former detainee told Human Rights Watch that he had lost nearly half his body weight during just six months of detention.[74]

“Ala’a,” a 16-year-old from Tal Kalakh said that Syrian security forces detained him for eight months, starting in May 2011, after he participated in and read political poetry at demonstrations. He was released in January 2012 after his father bribed a prison guard with 25,000 Syrian pounds (US$436). During his detention he was held in seven different detention centers, including at the Military Security branch in Homs:

When they started interrogating me, they asked me how many protests I had been to, and I said ‘none.’ Then they took me in handcuffs to another cell and cuffed my left hand to the ceiling. They left me hanging there for about seven hours, with about one-and-a-half to two centimeters between me and the floor—I was standing on my toes. While I was hanging there, they beat me for about two hours with cables and shocked me with cattle prods. Then they threw water on the ground and poured water on me from above. They added an electric current, and I felt the shock. I felt like I was going to die. They did this three times. Then I told them, ‘I will confess everything, anything you want.’

He said that in the Homs Central Prison, he was kept in a large cell with some 150 boys under age 18, as well as about 80 men over 50.[75]

Many detainees, including children, have died in Syrian custody. In August 2013, a military defector code-named Caesar smuggled over 50,000 photographs out of Syria, depicting at least 6,786 detainees who died in detention or after being transferred from detention to a military hospital. Caesar said that he had served as an official forensic photographer for the Military Police, and been responsible for photographing the bodies of dead detainees, as well as members of security forces who died in attacks by armed opposition groups. A doctor working for the Syrian Association for Missing and Conscience Detainees reviewed all of the photographs and estimated that at least 100 of the dead were boys under age 18.[76]

Human Rights Watch was able to locate and interview 33 individuals who said they had identified relatives or friends among the Caesar photographs. Among the cases Human Rights Watch verified was one of a 14-year-old boy, Ahmad al-Musalmani, from Namr, Daraa. Ahmad was arrested in August of 2012 while traveling in a minibus to attend his mother’s funeral. According to fellow passengers, officers from Air Force Intelligence stopped the car at a checkpoint and an officer asked Ahmad why he was crying. Ahmad answered, ‘I am crying because my mother died.’ The officer took the passengers’ phones and began to search them. When he found an anti-Assad song on Ahmad’s phone, he began to insult Ahmad and dragged him into a small room at the checkpoint. The other passengers were allowed to travel on, and later contacted Ahmad’s family to report what had happened.

Ahmad’s family members tried for nearly three years to locate the boy. After the Caesar photographs were released, Ahmad’s uncle found photos of Ahmad’s body among them, in a folder dated August 2012—the month of Ahmad’s arrest. He told Human Rights Watch, “It was a shock. Oh, it was the shock of my life to see him here. I looked for him, 950 days I looked for him. I counted each day.”[77] Forensic pathologists who examined the photos reported marks of blunt force trauma on Ahmad’s body.[78]

Of the 1,433 children the Violations Documentation Center in Syria has identified as being detained by Syrian authorities, only 436 are known to have been released.[79] The status of the remainder is unknown.

United States

During US military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, US forces apprehended and detained thousands of boys suspected of participating in armed activities. In Iraq alone, the US confirmed that between 2003 and 2008, it detained at least 2,400 children. According to the US, these children were captured engaging in anti-coalition activity, such as planting improvised explosive devices (IEDs), operating as lookouts for insurgents, or actively fighting against US or coalition forces.[80]

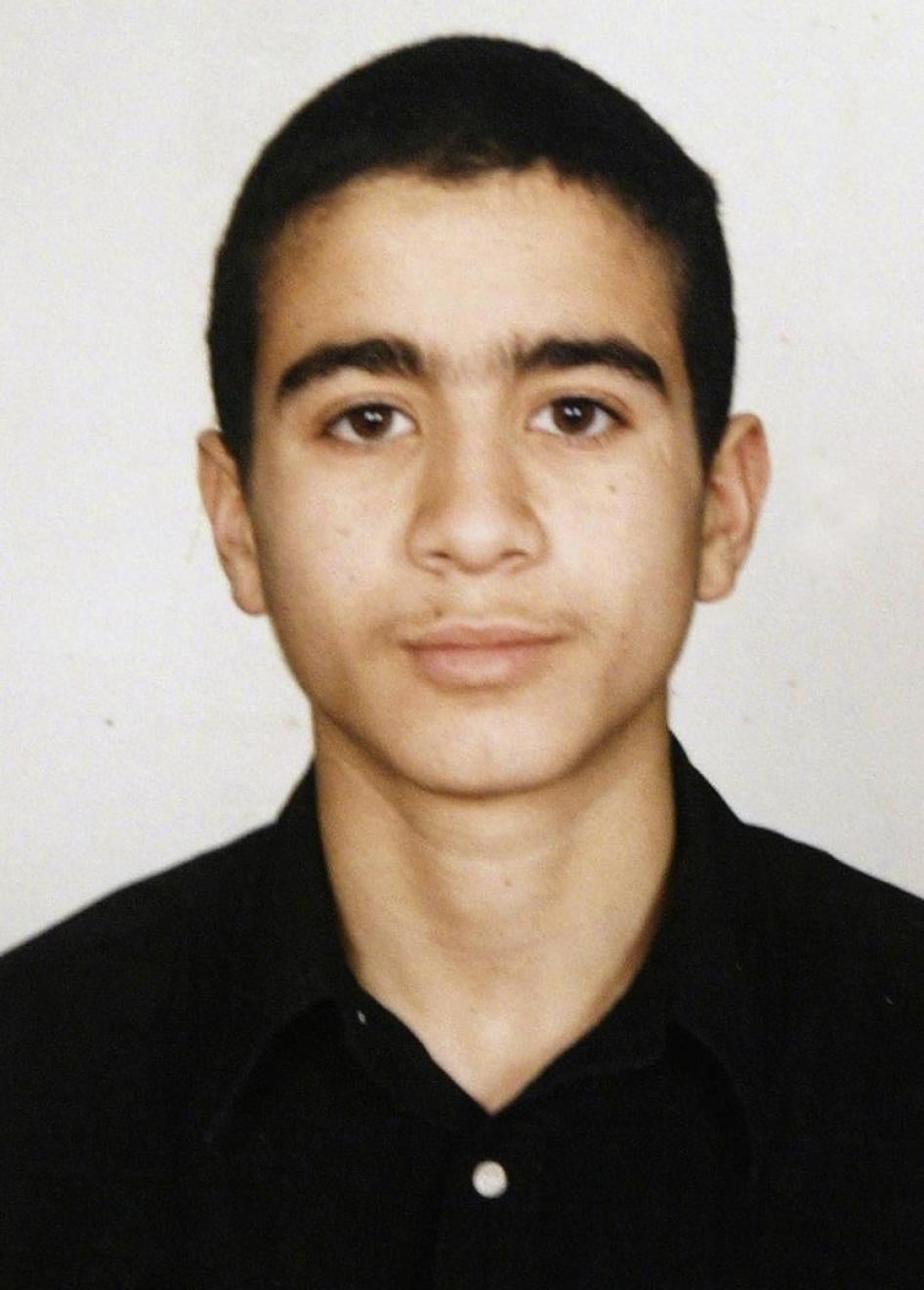

After the 9/11 attacks, the US military took into custody at least 15 children and brought them to the Guantanamo Bay detention facility where they were detained for periods ranging from a few months to 10 years.[81] Several of the child detainees alleged torture, including threats of rape, sleep deprivation, and shackling in painful positions, before and after being sent to Guantanamo.

At least two child detainees attempted suicide while at Guantanamo, and according to US government documents, one other former child detainee committed suicide at Guantanamo at age 21.[82] Two child detainees, Omar Khadr and Mohammed Jawad, were charged with offenses before the US military commissions. Jawad was detained for six years before a federal judge ordered his release back to Afghanistan in 2009. Khadr accepted a plea bargain and after 10 years at Guantanamo, was repatriated to Canada in 2012 to serve the remainder of his sentence.[83] He was released in May 2015.

During the US troop “surge” in Iraq in early 2007, US military apprehensions of children there rose to an average of 100 per month, compared to 25 per month the previous year.[84] In September 2007, US military officials reported that 828 children were held at Camp Cropper in Iraq, including some as young as 11.[85] The US opened a non-residential facility called Dar al-Hikmah to provide 600 child detainees with education services pending their release or transfer to Iraqi custody, but excluded an estimated 100 children from participation in the program, reportedly on the grounds that they were “extremists” and “beyond redemption.”[86] US soldiers stationed at US-run detention centers and former detainees described abuses against child detainees, including the rape of a 15-year-old boy at Abu Ghraib prison, forced nudity, stress positions, beating, and the use of dogs.[87]

In 2010, the US told the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child that it had “gone to great lengths” to reduce the number of children held in detention and that as of December 31, 2009, the US held fewer than five detainees under the age of 18 in Afghanistan and Iraq.[88] However, when Human Rights Watch visited the main US-operated detention facility in Parwan, Afghanistan, in March 2012, facility representatives told Human Rights Watch researchers that they held 250 detainees under the age of 18, including 11 children who were 15 years old.[89] They stated, contrary to international law, that only those under 16 were considered “children” and were separated from the adult population.

Detainees aged 16 or 17 were typically held with adult detainees in rooms holding up to 34 people. Detainees who exhibited good behavior were allowed to participate in rehabilitation programs, including gardening, masonry, and metalwork, but no special programs or education were available for the 16 and 17-year-olds. Although US military representatives said that no children under 15 were detained at Parwan, a lawyer representing several Pakistani detainees told Human Rights Watch that one of her clients was picked up and taken to the facility at age 14. The US rejected requests by the UN children’s fund, UNICEF, to have access to the children in detention.

According to the US government, children detained by the US in Afghanistan received a review through a Detainee Review Board after 60 days and every six months thereafter. However, these review boards did not meet international due process requirements for individuals apprehended in a non-international armed conflict, which was the situation in Afghanistan by 2002. For example, detainees did not have access to counsel and did not see all the evidence used against them.

According to the US government, the average length of detention for children at Parwan was approximately one year.[90] The US asserted that detention was “preventative” rather than punitive, and that the detention of “enemy combatants” for the duration of an armed conflict “is a fundamental incident of waging war.”[91] It said that because detention was to prevent a combatant from returning to the battlefield, a detainee would generally not be provided legal assistance, as would be the case if the detainee were charged with a crime.[92] This approach ignored that during a non-international armed conflict—involving one or more countries fighting a non-state armed group—the home country’s criminal laws remain in effect.[93]

In 2014, the United States and Afghanistan reached an agreement in which Afghanistan took responsibility for detention facilities as of January 1, 2015.[94] Currently, US forces that capture individuals, including children, suspected of security-related offenses may detain them for a few hours to several days at an international military facility before turning them over to Afghan authorities.[95]

Legislation

In recent years, a growing number of countries have introduced, enacted, or amended laws allowing authorities greater scope to detain individuals, including children, who are perceived to be security threats. As shown above, these laws increase the periods of time that suspects can be detained without charge, allow preventive and indefinite detention, and expand the scope of military courts and detention under military authority. Below are additional examples of such laws that are likely to affect children.

In late 2015, the Australian government proposed counterterrorism legislation that would reduce the age for children who are subject to a control order from 16 to 14.[96] The justice minister stated that the government would also consider extending control orders to children as young as 12.[97] Such control orders could include electronic tagging, curfews, requirements to report to police, and restrictions on movement and association. The following month, parliament enacted the Australia “allegiance” act, allowing the immigration minister to strip Australian citizenship from dual nationals as young as 14 if they are alleged to have engaged in terrorism abroad or are outside Australia at the time the allegations surface, even if they have not been convicted of any crime.[98]

In Indonesia, after ISIS carried out attacks in Jakarta in January 2016, the government introduced a counterterrorism bill allowing preventive detention of terrorist suspects for up to six months. The law at the time allowed for seven days’ detention before suspects must be charged or released and required evidence of a criminal act. The proposed bill increased the period of pre-charge detention to 30 days, and increased the maximum period of detention for investigation purposes from six months to 8 to 10 months.[99]

In January 2016, a counterterrorism law was passed in Brazil, with vague and overbroad language that could be used against peaceful advocacy groups. Under the law, damaging any public or private property, and “taking over” various sites, including schools and bank offices, can be considered terrorist acts. The law also establishes the crime of “promoting,” “forming,” “joining” or “aiding” terrorist organizations without providing a definition of what constitutes a “terrorist organization.” The crime is punishable with a prison sentence of five to eight years for adults, and up to three years’ confinement for children.[100]

In Egypt, after a 2014 attack killed dozens of Egyptian soldiers in the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt’s president issued a decree vastly extending the reach of the country’s military courts.[101] Between October 2014, when the decree was issued, and April 2016, military courts tried at least 7,420 Egyptian civilians, including at least 86 children.[102] In one case, a high school student arrested on the street outside his school told his mother that National Security agents stripped him, walked on him, extinguished cigarettes on his skin, and gave him electric shocks on various parts of his body, including his genitals, to make him confess to belonging to a “terrorist cell” that planted explosives and burned electricity stations. A military court sentenced him to three years in prison. In another case, a military court sentenced a 15-year-old to three years in a juvenile detention facility for allegedly participating in an illegal protest.[103]

The following year, Egypt enacted a new counterterrorism law,[104] increasing authorities’ power to impose harsh sentences, including the death penalty, for crimes under a definition of terrorism that is so broadly worded it could encompass peaceful civil disobedience. The new law also gave prosecutors greater power to detain suspects without judicial review and order wide-ranging and potentially indefinite surveillance of terrorist suspects without a court order.[105]

Conclusions and Recommendations

As governments respond to armed conflicts and violence by extremist armed groups, they have detained thousands of children for actual or suspected association with non-state armed groups, participation in conflict-related offenses, or as perceived threats to national security. Governments have expanded counterterrorism laws and given military and other authorities greater leeway to detain suspects, including children, often indefinitely and without charge.

Children are often rounded up in massive sweeps, or arrested based on flimsy or baseless accusations. Large numbers of children detained for national security reasons are subject to torture and other ill-treatment, often to coerce confessions or intelligence information. They frequently are denied access to lawyers, other due process guarantees or protections established under international juvenile justice standards. They are often held with adult detainees in severely overcrowded cells, lacking adequate water, food, or medical care. Rarely do they have access to education or any rehabilitative programs. In the most extreme cases, detained children have died from starvation, dehydration, lack of medical care, or as a result of torture.

To uphold the rights of the child, governments should immediately end all use of detention without charge for children. They should ensure that children associated with armed groups are transferred to child protection authorities for rehabilitation, and in cases where children may have committed illegal acts, ensure their treatment is consistent with international juvenile justice standards.

Recommendations for governments:

- Release all children detained for alleged security related offenses unless they have been charged with a recognizable criminal offense.

- Strictly comply with international legal obligations to detain children only as a last resort and for the shortest possible period of time.

- When prosecuting children alleged to have committed illegal acts, treat children in accordance with international juvenile justice standards. In particular, ensure that children enjoy full due process guarantees, including access to counsel, the right to challenge their confinement, contact with their families, and separation from adult detainees. Ensure that any punishment for criminal offenses be appropriate to their age, and be aimed at their rehabilitation and reintegration into society.

- Investigate all allegations of torture and ill-treatment against children in detention, and appropriately prosecute those responsible.

- Allow independent humanitarian agencies, including UNICEF, unrestricted access to all children in all detention facilities.

- Develop protocols to hand over children suspected of association with armed groups to UNICEF or appropriate child protection authorities for rehabilitation and reintegration.

Acknowledgments

This report was written by Jo Becker, advocacy director for the Children’s Rights Division at Human Rights Watch, based on research by Ida Sawyer, senior researcher for the Democratic Republic of Congo; Timo Mueller, researcher for the Democratic Republic of Congo; Erin Evers, former researcher in the Middle East and North Africa Division; Mausi Segun, Nigeria researcher; Sari Bashi, Israel/Palestine country director; Ashira Ramadan, research assistant in the Middle East and North Africa Division; Ole Solvang, deputy director of the Emergencies Division; Anna Neistat, former associate director of Program and Emergencies; Priyanka Motaparthy, researcher in the Emergencies Division; Nadim Houry, deputy director of the Middle East and North Africa division; and other researchers at Human Rights Watch.

The report was edited by Michael Bochenek, senior counsel for the Children’s Rights Division; James Ross, legal and policy director; and Danielle Haas, senior editor in the Program Office. Additional specialist review was provided by Sari Bashi; Nadim Houry; Mausi Segun; Hadeel al-Shalchi, Syria researcher; Bill van Esveld, senior researcher in the Children’s Rights Division; Heather Barr, senior researcher in the Women’s Rights Division; Patti Gossman, senior researcher on Afghanistan; Laura Pitter, senior national security counsel in the US Program; Christoph Wilcke, senior researcher in the Middle East and North Africa Division; Maria Laura Canineu, Brazil director in the Americas Division; Andreas Harsono, Indonesia researcher; and Georgie Bright, Australia associate.

Design and production assistance was provided by Susan Raqib, associate in the Children’s Rights Division; Olivia Hunter, photo and publications associate; Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager; and Jose Martinez, senior administration coordinator.