Summary

Two years ago my left hand got paralyzed from the tumor and I started to develop severe pain. It felt as though it was burning, as if my arm was on fire. It was hellish pain. . . . Now I have pain 24 hours a day, but at night it becomes unbearable, when pain gets even worse, and I just start screaming. Two months ago I was prescribed one ampoule of injectable omnopon [opioid pain medication]. It was then enough to sooth my pain for four hours, but now it helps only for maximum of two. I keep it for nights, so that I can sleep for those two hours. The pain attacks start unexpectedly and I start screaming and become a different person. … When it starts I [can’t speak], I have pain attacks every night.… It’s inhumane pain, unbearable pain for a human being….[1]

This is how Lyudmila, a 61-year-old retired kindergarten teacher in Armenia, described to Human Rights Watch the pain she had been enduring for about two years from her inoperable breast cancer. Her words were deeply personal. But her experience is not an exception. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 80 percent of people with advanced cancer worldwide develop moderate to severe pain at the end of life.

Cancer is on the rise in Armenia. Some 8,000 people die from it annually, and many of them do so in excruciating pain. But it does not have to be this way. Most of the pain endured by Lyudmila and others like her can be easily alleviated. Morphine, the mainstay medication for treating severe pain, is inexpensive and easy to administer, but widely inaccessible to people who need it in Armenia. Other palliative care services that help people ease pain and end-of-life suffering are also largely unavailable in Armenia.

Palliative care is a field of medicine that seeks not to cure disease but to prevent suffering and improve quality of life. It focuses on treating pain and other physical symptoms, and providing psychosocial support, complementing curative treatment. The two should be provided in parallel from the moment of diagnosis. Palliative care may even help curative treatment to succeed, for example, by enabling a patient to eat, exercise, communicate, or adhere to a medication regimen.

The lack of palliative care in Armenia condemns thousands of patients with life-limiting illnesses to chronic pain and great suffering. Most patients with advanced cancer in Armenia are simply sent home when curative treatment is no longer effective. Abandoned by the health care system at arguably the most vulnerable time of their lives, they face pain, fear, and anguish without professional support. This is particularly devastating given that over half of all cancer patients in Armenia are at a late stage of the disease when they receive their diagnosis, when curative treatment is ineffective and palliative care and pain management are the only services that may still benefit them.

In recent years, the government of Armenia has recognized the need for palliative care and taken important steps to develop it. But much remains to be done. This report documents these gaps: overly restrictive government regulations on accessing strong pain medication, ingrained practices among health care professionals that impede adequate pain relief, the lack of training and education of health care professionals on palliative care, and the overall absence of palliative services in Armenia. It focuses on the devastating impact of untreated pain and lack of support services for cancer patients and their families on the quality of their lives. It is based on dozens of interviews with patients, their families, health care professionals, government officials, and patients’ advocacy groups, and other nongovernmental organizations from 2012 to 2o14.

Medicines Availability

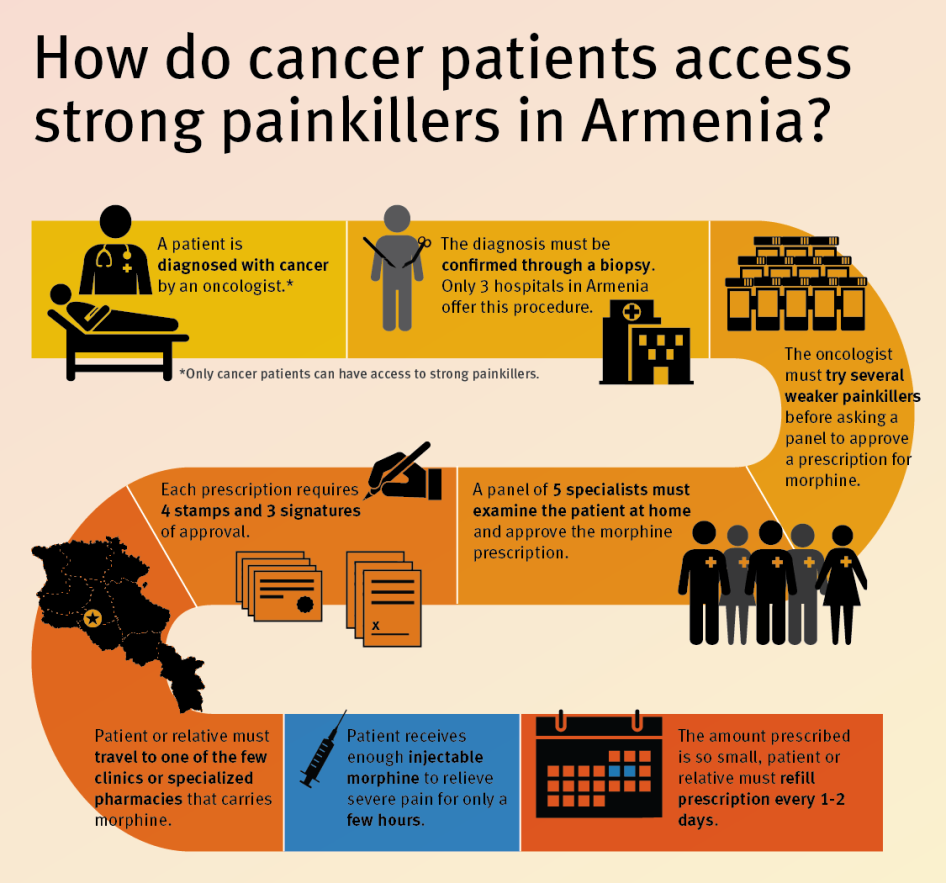

The key obstacle to effective pain treatment in Armenia remains an overly restrictive legislative basis governing the distribution of opioids for medical purposes. The country’s pain treatment practices deviate fundamentally from World Health Organization (WHO) standards on pain management. Oral morphine, the medicine of choice for the treatment of severe chronic pain, is unavailable in Armenia. Oncologists lack awareness, guidance, and training on the medicinal use of opioids and often perceive morphine as dangerous.

Under current government regulations, the procedure for prescribing injectable opioids is complex, time-consuming, and involves significant bureaucracy. Only oncologists may prescribe opioids to outpatients, and only to cancer patients. Oncologists can prescribe opioids only after multiple doctors have signed off on the decision; and even after that multiple signatures and seals are necessary for each prescription.

Another problem is inadequate dosage. Although Armenian regulations do not establish maximum dosages, the standard practice is to start a patient on a single opioids injection per day and then add a second daily injection after about two weeks. The analgesic effect of injectable morphine lasts up to four hours, leaving even patients like Lyudmila, who are fortunate enough to have been prescribed opioids, without adequate pain relief for most of the day. While doctors often supplement opioids with weaker pain medicines and other medications for the intervals, these are not potent enough to provide effective relief and expose patients to unnecessary side effects.

Once opioid analgesics are prescribed, cancer patients or their caregivers must go to the clinic to collect the prescription with its four different stamps, fill it at one specialized pharmacy in Yerevan or at large regional medical centers outside of the capital, and return the empty ampoules before a new prescription is issued. They must repeat the process every other day or in some cases every day because in practice doctors will prescribe only enough strong opioids to last 24 or 48 hours. This is enormously time-consuming and takes a severe toll on patients’ families, who are often already under severe emotional distress.

Police control over the prescription and dispensing process is tight, invasive, and generates a sense of trepidation among oncologists and pharmacists. All oncologists interviewed for this report said that they provide written monthly reports to the police about patients who receive opioid painkillers. In violation of patient confidentiality, such reports include the patient’s name, address, ID number, diagnosis, prescribed dosage and the name and other information of the person who picks up the prescription and fills it. Police also conduct regular, informal inspections at polyclinics, participate in destruction of full ampoules and sometimes also empty ampoules. While police and other law enforcement bodies have a legitimate interest in ensuring opioid analgesics do not enter black markets, the right to health protects against improper interference with appropriate medical practice. Under the right to privacy, law enforcement officials may not routinely require confidential medical information on patients who receive opioid analgesics from hospitals, clinics or pharmacies.

Training and Education

At Armenia’s medical schools medical and nursing students receive virtually no training on palliative care and adequate pain treatment. As a result, health workers lack skills in assessing and treating pain, and communicating appropriately with patients and their families about the patient’s illness. Oncologists often do not disclose a cancer diagnosis and often hide key medical information, leaving the patient to suffer without knowing the cause, unable to ask questions and find answers, deprived of the chance to put their affairs in order.

Since at least 2012 independent groups have been providing palliative care and pain management trainings for oncologists in Armenia, but it is neither systematic, nor mandatory. The mandatory curriculum in medical schools does not include any specific instruction on palliative care. Palliative care residency or fellowship programs that would lead to specialization in palliative care have not yet been implemented in Armenia’s medical schools.

Policy Reforms

The WHO has recommended that countries establish a national palliative care policy or program and that palliative care services be made available at the community level and in specialized hospitals for low- and middle-income countries. The Armenian government has clearly recognized the need for palliative care. In 2009, palliative care services were for the first time included in the government’s list of recognized medical services. In 2010, the government established a palliative care working group, consisting of relevant government agencies and expert civil society groups, which developed a concept paper and a national strategy for palliative care. In August 2012, the government approved the concept paper, which is largely a needs-assessment study on palliative care. In 2013, the working group developed the national strategy, an operative plan for implementing palliative care, but the government has yet to approve it. From 2011 to 2013, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, together with the Open Society Institute Assistance Foundation Armenia and the Health Ministry ran four palliative care pilot projects in order to estimate the costs of eventually incorporating palliative care into the public health care system.

In December 2014, the Ministry of Health approved three policy documents establishing the structure and organization of palliative care services and professional qualifications for doctors and nurses in palliative care; the standards for palliative medical care and services; and clinical guidelines for pain management. These steps are important but without reforms of policies on controlled substances and education of health care workers on palliative care, the impact of these measures on the availability of palliative care will be limited at best.

Barriers to effective pain treatment place Armenia in violation of the right to health and create a risk that patients will be subjected to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment in violation of Armenia’s international obligations. Moreover, the World Health Assembly, the WHO’s governing body, unanimously adopted a resolution in May 2014, calling the provision of palliative care an “ethical responsibility of health systems” and urging UN member states to integrate palliative care into their health care systems. The Armenian government therefore should take the lead in addressing the barriers that currently impede the availability of good palliative care and pain treatment in Armenia.

Most importantly, the government of Armenia should adopt without further delay and implement the national strategy on palliative care, which addresses all major areas of palliative care policy: education, medicines availability, and implementation of palliative care services. It should also urgently address serious gaps in education of health care professionals on palliative care.

Key Recommendations to the Government of Armenia

On Availability of Medicines

- Work with manufacturers and importers to facilitate the registration of oral opioid painkillers. The public health care system should carry oral morphine, once it is registered, at all levels of care.

- Abolish the restriction that allows only oncologists to prescribe opioid painkillers. Allow all physicians with proper clinical training and working in palliative care to prescribe opioid painkillers.

- Remove the restriction that allows only outpatients with cancer to receive prescriptions for opioid painkillers. Any patient with a life-limiting condition with moderate to severe pain should have access to adequate pain medication.

- Reform the overly onerous procedure for the prescription of opioid painkillers by allowing doctors to make individual decisions to prescribe opioids medications and reducing bureaucratic requirements.

- Cease excessive police interference in the prescription process. Doctors should stop the current practice of filing reports on patients’ prescriptions with police. Police should make clear to doctors that they do not require such reports, formally or informally, and will no longer accept them, unless there is evidence that a crime has been committed.

On Policy Development

- Without further delay, adopt the National Strategy and Action plan for the Introduction of Palliative Care and Services in Armenia.

- Develop and incorporate palliative care services throughout the public health care system.

On Awareness Raising and Education

- Introduce palliative care instruction into medical and nursing curricula.

- Ensure that doctors and other relevant health care workers are trained in how to communicate to patients about their diagnoses and other information on life-limiting illnesses. Ensure that they are trained and supported in holding end-of-life conversations with patients and their families.

- Raise public awareness around the right to pain relief and on the availability of treatment for severe pain.

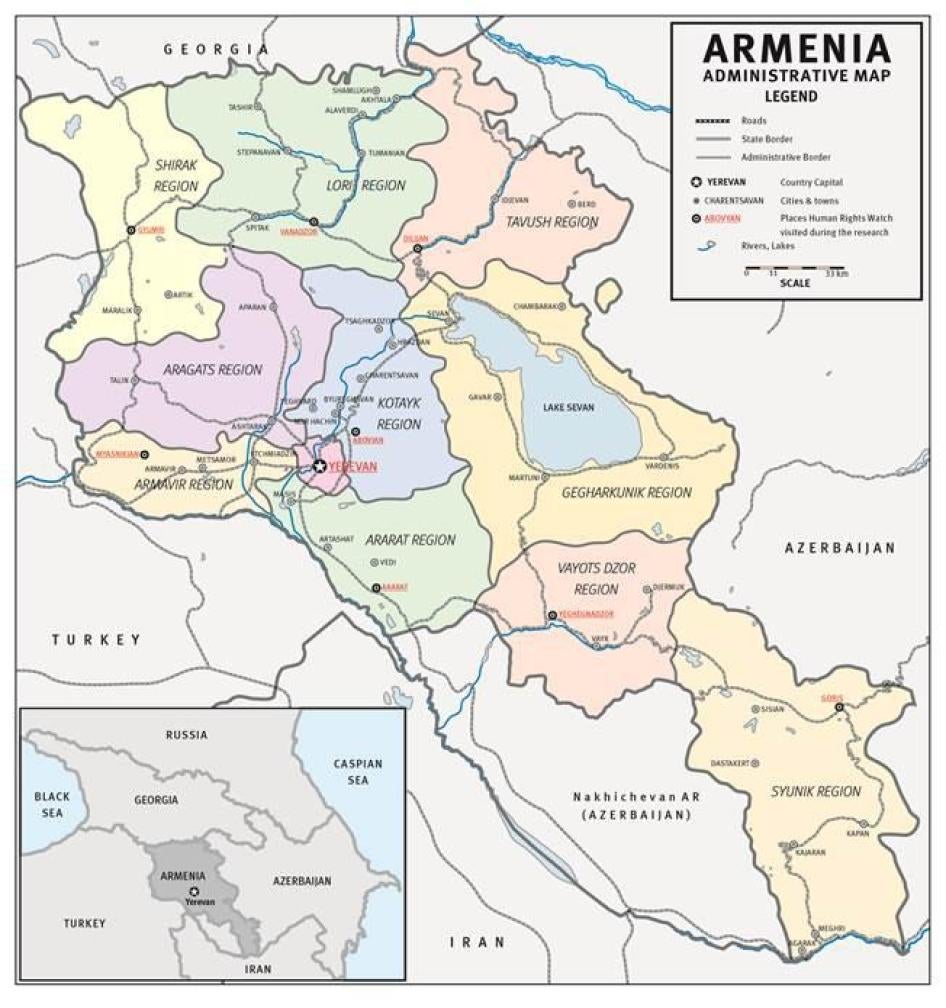

Map of Armenia

Key Terms in Palliative Care and Pain Treatment

Palliative care: Health care that aims to improve the quality of life of people facing life-limiting illness, through pain and symptom relief, and through psychosocial support for patients and their families. Palliative care can be delivered in parallel with curative treatment, but its purpose is to care, not to cure.

Life-limiting illness: A broad range of conditions in which painful or distressing symptoms occur; although there may also be periods of healthy activity, there is a strong possibility of premature death.

Psychosocial support: A broad range of services for patients and their families to address the social and psychological issues they face due to life-limiting illness. Psychologists, counselors and social workers often provide these services. Many kinds of psychosocial support can be performed by volunteers.

Hospice: A specialist palliative care program for patients close to the end of life. There are no specialized hospices in Armenia.

Chronic cancer pain: Defined in this report as pain that occurs over weeks, months, or years rather than a few hours or days. Because of its duration, moderate to severe chronic cancer pain should be treated with oral opioids rather than repeated injections, especially for people emaciated by the disease.

Analgesic: medicine used to relieve pain. In the plural form (analgesics) they denote a class of medicines that relieve pain. Analgesics provide symptomatic relief, but have no effect on the cause.

Opioid: Substance derived from the opium poppy and similar synthetic drugs. All strong pain medicines, including morphine, are opioids. Weaker opioids include codeine, tramadol, and dihydrocodeine.

Morphine: A strong opioid medicine and the mainstay medication for treatming moderate to severe pain. Morphine is considered an essential medicine by the World Health Organization in its injectable, tablet, and oral solution formulations. Oral solution mixed from morphine powder is the cheapest formulation. At this writing Armenia has registered only injectable morphine.

Dependence: In 1964, a WHO Expert Committee introduced the term “dependence” to replace the terms “addiction” and “habituation.” Dependence refers to both physical and psychological elements. Psychological or psychic dependence refers to the experience of impaired control over drinking or drug use while physiological or physical dependence refers to tolerance and withdrawal symptoms.

Dependence or physical dependence is also used in the psychopharmacological context in a narrower sense, referring solely to the development of withdrawal symptoms on cessation of use of drugs or medications.

Internationally controlled substances: Substances that are listed as subject to international control in one of the three international drug control conventions: the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961 as amended by the 1972 Protocol; the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971; and the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988.

Diversion: The movement of controlled drugs from licit to illicit distribution channels or to illicit use.

Curative treatment or curative care: Health care given for medical purposes when a cure is considered achievable or possibly achievable, and directed to this end.

Polyclinic: a health care facility in Armenia that is primarily devoted to the care of outpatients; it typically covers the primary health care needs of populations in local communities, in contrast to hospitals and clinical centers, which offer specialized treatments and admit inpatients for overnight stays.

Dispensary: a medical institution in Armenia for specialized hospital and outpatient care, such as oncology, mental health, endocrinology, etc.

Symptomatic treatment: a medical therapy that seeks to alleviate symptoms. It is usually aimed at improving the comfort and well-being of the patient. Symptomatic treatment largely focuses on physical symptoms, while palliative care also includes psychosocial and spiritual care.

A pain scale: a numeric scale for measurement of patient’s pain intensity, based on self-report mostly, with zero being no pain and 10 being the worst pain imaginable. This measurement approach is the most common method used internationally for determining patient reported pain. Pain severity of 5 to 6 is considered a moderate pain and generally interferes significantly with daily living activities; pain severity of 7 and higher is considered severe pain, which is generally disabling, and often renders a patient unable to perform basic everyday activities.

Essential medicines: Those medicines that are listed on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Model List of Essential Medicines or the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children. Both model lists present a list of minimum medicine needs for a basic health care system, listing the most efficacious, safe, and cost-effective medicines for priority conditions.

Misuse (of a controlled substance): Defined in this report as the non-medical and non-scientific use of substances controlled under the international drug control treaties or national law.

Over-the-counter pain medicines: Non-opioid pain medicines suitable for mild pain, including paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen), aspirin, and ibuprofen that can be obtained without a prescription.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between July 2012 and October 2014, including three field visits to Armenia in July and November 2012 and October 2014. Field research was conducted in the capital, Yerevan, and other towns and villages throughout Armenia, including Ararat, Yeghegnadzor, Goris, Abovyan, Dilijan, Vanadzor, Gyumri, and Myasnikyan.

While this report is about palliative care generally, our research focuses on people who have cancer and who need pain treatment. The need for palliative care is most visible in people with cancer because of their sheer numbers and the severe and chronic pain and suffering they endure; and we focus mostly on the pain treatment component of palliative care because it is often the first symptom on patients’ minds.

During the three field research trips, Human Rights Watch researchers conducted 90 interviews with a wide variety of stakeholders, including 17 oncologists, 18 nurses and other medical professionals, including anesthesiologists and hospital administrators, and 26 people with cancer or their relatives.

Most interviews with patients and their relatives were conducted in their homes; some were conducted at hospitals. Interviews with patients were conducted in private whenever possible; in some cases the patient’s relatives were also in the room. All ages of the patients interviewed are as of the date of the interview.

Interviews were semi-structured and covered a range of topics related to palliative care and pain treatment. Before each interview we informed interviewees of its purpose, informed them of the kinds of issues that would be covered, and asked whether they wanted to participate. We informed them that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific questions without consequence. Human Rights Watch made no promises of personal service or benefit to those whom we interviewed for this report and told all interviewees that the interviews were completely voluntary and confidential.

We concealed the identities of all patients, relatives, and health care workers interviewed to protect their privacy, except when they specifically asked for their identity to be used. Similarly, we have concealed the names of health care workers who, as government employees, may have legitimate concerns about possible negative consequences to their speaking out about problems with pain treatment.

We also met health officials, including the chief of staff of the Health Ministry, the deputy health and justice ministers, the head of the Parliamentary Committee on Health, and high-level officials from Police of the Republic of Armenia, including a deputy police chief, to present and discuss preliminary findings of our research. We also requested and obtained cancer morbidity statistics from the National Oncology Center.

Most interviews were conducted in Russian by Human Rights Watch researchers who are fluent Russian speakers. Some interviews were conducted in Armenian, during which a translator for Human Rights Watch (a native speaker of Armenian) translated into Russian or English.

All documents cited in this report are publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch.

I. Background

The Importance of Palliative Care and Pain Treatment

Palliative care seeks to improve the quality of life of patients, both adults and children, facing life-limiting or terminal illness. Its purpose is not to cure a patient or extend his or her life. Palliative care prevents and relieves pain and other physical and psychosocial problems. In the words of Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the first modern hospice and a lifelong advocate for palliative care, palliative care is about “adding life to the days, not days to the life.” The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes palliative care as an integral part of health care that should be available to those who need it.[2] While palliative care is often associated with cancer, a much wider circle of patients with health conditions can benefit from it, including patients in advanced stages of neurological disorders, cardiac, liver, or renal disease.[3]

One key objective of palliative care is to offer patients effective treatment for their pain. Chronic pain is a common symptom of cancer and HIV/AIDS, as well as other health conditions, especially in the terminal phase of illness.[4]The WHO estimates that around 80 percent of both cancer and AIDS patients and 67 percent of patients with both cardiovascular diseases and chronic pulmonary diseases will experience moderate to severe pain at the end of life.[5] A recent global review of pain studies in cancer patients found that 60 to 90 percent of patients with advanced cancer experience moderate to severe pain.[6]

Moderate to severe pain has a profound impact on quality of life. Persistent pain has a series of physical, psychological, and social consequences. It can lead to reduced mobility and consequent loss of strength; compromise the immune system; and interfere with a person’s ability to eat, concentrate, sleep, or interact with others.[7] A WHO study found that people who live with chronic pain are four times more likely to suffer from depression or anxiety.[8] The physical effect of chronic pain and the psychological strain it causes can even influence the course of disease: as the WHO notes in its cancer control guidelines, “Pain can kill.”[9] Social consequences include the inability to work, care for oneself, children or other family members, participate in social activities, and find closure at the end of life.[10]

According to the WHO, “Most, if not all, pain due to cancer could be relieved if we implemented existing medical knowledge and treatments” (original emphasis).[11] The mainstay medication for the treatment of moderate to severe pain is morphine, an inexpensive opioid that is made of an extract of the poppy plant. Morphine can be injected, taken orally, delivered through an IV or into the spinal cord. It is mostly injected to treat acute pain, generally in hospital settings. Oral morphine is the medicine of choice for chronic cancer pain, and can be taken both in institutional settings and at home. Morphine is a controlled medication, meaning that its manufacture, distribution, and dispensing is strictly regulated both at the international and national levels.

For decades, medical experts have recognized the importance of opioid pain relievers. The 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the international treaty that governs the use of narcotic drugs, explicitly states that “the medical use of narcotic drugs continues to be indispensable for the relief of pain and suffering” and that “adequate provision must be made to ensure the availability of narcotic drugs for such purposes.”[12] The WHO has included morphine in its Model List of Essential Medicines, a list of the minimum essential medications that should be available to all persons who need them, since it was first established.[13]

Yet, approximately 75 percent of the world population has either no or insufficient access to treatment for moderate to severe pain and tens of millions of people around the world, including around 5.5 million cancer patients and one million end-stage HIV/AIDS patients, suffer from moderate to severe pain each year without treatment.[14]

Palliative care is broader than just relief of chronic physical pain. Other key objectives of palliative care include the provision of care for other physical symptoms and psychosocial and spiritual care to both the patient and his or her family. Life-limiting illness is frequently associated with various other physical symptoms, such as nausea and shortness of breath, that have significant impact on a patient’s quality of life. Palliative care seeks to alleviate these symptoms.

People with life-limiting illness and their relatives often confront profound psychosocial and spiritual questions as they face life-threatening or incurable and often debilitating illness. Anxiety and depression are common symptoms.[15] Palliative care interventions like psychosocial counseling have been shown to considerably diminish incidence and severity of such symptoms and to improve the quality of life of patients and their families.[16]

The WHO has urged countries, including those with limited resources, to make palliative care services available. It recommends that countries prioritize implementing palliative care services in the community—providing care at people’s homes rather than at health care institutions—where it can be provided at low cost and where people with limited access to medical facilities can be reached, and in medical institutions that deal with large numbers of patients requiring palliative care services.[17]

In recent years, the WHO and the World Bank have urged countries to implement free universal health coverage to ensure that all people obtain the health services they need without suffering financial hardship when paying for them.[18] Palliative care is one of the basic health services that the WHO and the World Bank say should be available under universal health coverage, along with “promotive, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative” health services.[19]

In May 2014, the World Health Assembly, the WHO’s governing body, unanimously adopted the resolution “Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive treatment within the continuum of care,” calling the provision of palliative care an “ethical responsibility of health systems.” It made detailed recommendations to UN member states with regard to development of policies supportive of palliative care; the provision of training and education for health care workers; and drug regulatory reforms to ensure the adequate availability of opioid analgesics.[20]

Background on Armenia

Armenia’s Health Care System

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Armenia inherited a centralized health care system with free medical care for the entire population and access to a comprehensive range of primary, secondary, and tertiary services funded by general government revenues.[21] Since then, Armenia has undertaken extensive health care reforms to decentralize the health care system, to make it more efficient, and implement new approaches to health care financing, including through privatization.[22] One of the core elements of the reform was changing the primary care system and the introduction of the family doctor. Armenia still has a highly centralized health care system, in which the central government makes most decisions on resource allocations.

Institutional Structure of Health Care

Primary outpatient health care services in Armenia consist of city polyclinics, regional health centers, small village health clinics, and nursing/obstetric units. Provision of services is based on the population levels in a given community. Secondary care is provided by regional hospitals and dispensaries, or facilities that provide both inpatient and outpatient care in a single field of specialization, such as oncology, mental health, endocrinology, etc. National hospitals and specialized national institutions, such as the National Oncology Center in Yerevan, provide tertiary or further specialized care.[23]

Oncology services in polyclinics are free of charge. They perform cancer prevention and early detection, refer patients to specialized secondary and tertiary institutions for surgery and other curative treatment, and provide symptomatic treatment to oncology patients after curative care becomes ineffective. Polyclinics also register and keep track of oncology patients in the community and report statistics to the National Oncology Center.

The state is the exclusive provider of opioid pain medications. It purchases them from importers and provides them free of charge to pharmacies and health care facilities, which in turn do not charge patients for them.

Financing

Health care is financed by the state from tax revenues. Data on public spending on health care are difficult to assess because “[l]egislation does not require the systematic collection of comparable data, and existing data collection systems are fragmented.”[24] World Bank data estimates health care spending at 1.9 percent of Armenia’s GDP for the period 2010-2014.[25] The IMF estimated that public health care spending stood at 2.5 percent in 2012, but also noted the figure was an estimate because data on government spending by functional classification was not available for Armenia. [26]

While the government has almost doubled its health care expenditures since 2008, current spending still amounts to a small percent of the overall government spending budget and reflects a low priority in public spending.[27] Inadequate health care financing has increased institutional dependency on both formal and informal payments by patients. Formal payments include fees for medical services set by law; informal payments are usually “gratuities” to doctors, as well as purchases by the patients themselves of medicines that are not state-subsidized. Private health expenditures compose 48.3 percent of total health expenditures, with 84.6 percent paid out of pocket at the point of service.[28] With 35.8 percent of Armenians living below the poverty line in 2010, poverty is a large barrier to health care access for many Armenians. As a result, people often postpone necessary consultations or do not make use of medical services in first place.[29]

Noncommunicable and Chronic Illnesses and Palliative Care Needs

Like other low- and middle-income countries, Armenia faces both an increasing burden of chronic illness and major challenges in responding to them. As of 2013, Armenia’s population was 2,977,000.[30] According to World Health Organization statistics, the majority of deaths are due to non-communicable diseases (92 percent, total deaths 37,000): cardiovascular diseases (54 percent), cancers (22 percent), chronic respiratory diseases (5 percent), diabetes (3 percent), and other NCDs (non-communicable diseases) (8 percent).[31] According to 2012 data, the age-standardized mortality rate for malignant neoplasms for both Armenian males and females was 219.6 per 100,000 of the population.[32] In 2012, the top three causes for mortality per 100,000 of the population were: 1. noncommunicable diseases (847.5); 2. communicable diseases (45); and 3. injuries (49.2).[33] In addition, there is prevalence of lifestyle-associated health problems, such as tobacco smoking, with, according to WHO data, 47 percent of males and 2 percent of females engaging in this practice in 2011.[34] Tuberculosis (TB) continues to be a public health issue with 2,000 TB cases in 2013.[35] The prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the adult population aged 15-49 was 0.1 percent from 2001-2009 and increased to 0.2 percent in 2013.[36]

In Armenia, knowledge about noncommunicable diseases and cancer is limited, leading to frequent misdiagnosis and late referral of patients. It should be noted that Armenia does not have a national cancer registry, and data on cancer mortality varies. According to a WHO estimation, 8,100 people died of cancer in Armenia in 2012.[37] Data also shows that a high percentage of cancer is diagnosed only in advanced stages. According to the deputy head of the National Oncology Center, about 46 percent of patients are diagnosed at stage three or four in Armenia, when treatment is ineffective and palliative care is needed.[38] That figure, however, does not appear to include a significant number of those diagnosed post-mortem. According to statistics provided by the National Oncology Center, 7,911 people were diagnosed with cancer in 2013 in Armenia. Of these 2,949 were diagnosed at stage three and four, while 1,274 were diagnosed post-mortem (see Table 1).[39]

Table 1. Malignant Neoplasm Morbidity Rate[40]

1. Number of newly registered patients with malignant neoplasm:

|

2012 |

Armenia – 7,877 |

Men – 3,961 |

|

Women – 3,916 |

||

|

Yerevan – 2,747 |

Men – 1,301 |

|

|

Women – 1,446 |

||

|

2013 |

Armenia – 7,911 |

Men – 3,942 |

|

Women – 3,969 |

||

|

Yerevan – 2,863 |

Men – 1,341 |

|

|

Women – 1,522 |

2. Number of patients who died from malignant neoplasm:[41]

|

2012 |

Armenia |

TOTAL |

Registered |

Discovered post-mortem |

|

5,705 |

4,377 |

1,328 |

||

|

Yerevan |

1,992 |

1,411 |

581 |

|

|

2013 |

Armenia |

5,581 |

4,307 |

1,274 |

|

Yerevan |

2,085 |

1,464 |

621 |

3. Number of newly registered patients with malignant neoplasms based on stage of the disease:

|

2012 |

Stages one and two – 2,261 |

|

Stage three – 1,119 |

|

|

Stage four – 1,903 |

|

|

2013 |

Stages one and two – 2,247 |

|

Stage three – 985 |

|

|

Stage four –1964 |

II. The Plight of Patients

Cancer patients in Armenia, their family members, and health workers told Human Rights Watch of experiences of untreated pain and lack of psychosocial support and the impact of pain on the quality of their lives. They described how untreated pain led to reduced mobility, loss of strength, inability to eat, speak, concentrate, sleep, or interact with others, as well as anxiety, despair, and in some cases thoughts of suicide. Pilot projects in palliative care that ran in Armenia in 2011 through 2013 showed that such suffering can be largely avoided.

Availability of and Need for Palliative Care in Armenia

A needs-assessment study on palliative care commissioned by the Open Society Foundations and conducted in 2012 estimated that approximately 18,000 patients, including 5,500 cancer patients, need palliative care annually in Armenia.[42] In addition, at least twice as many family members require palliative care support.[43] The same study estimated that up to 60 palliative homecare teams are needed for the country, including 24 for Yerevan.[44]

However there are essentially no publicly-funded palliative care services in Armenia. Private palliative care services are available in at least two hospitals in Yerevan but they are unaffordable for most Armenians.

It is currently standard practice in Armenia that when cancer patients are no longer curable, they are sent for “symptomatic treatment” with oncologists at primary health facilities, who provide only minimal and mostly inadequate pain treatment.

People with advanced cancer have extensive health care needs, even if their disease can no longer be cured. They are likely to face various physical and psychosocial symptoms, including pain, difficulty breathing, bed sores, and anxiety. In Armenia, families traditionally care for their ill relatives at home. However, families are generally poorly equipped to do so because the health care system does not provide them any support.

There are no services for outpatients and their caregivers to provide psychosocial support and information about the course of the disease and potential symptoms; to teach family members about basic care and help them provide it; or to prepare the patient and family for what may/will come. Also, despite years of health care reform, Armenia’s health care system is still not set up to deliver general, regular homecare services, except for a mobile ambulance service, which does rapid assessment of patients and if need be transfers them to a hospital. As a result, families often have to scramble to try to take care of a dying loved one without any knowledge of how best to do so, leading to tremendous suffering for both patients and caregivers.

Furthermore cancer patients in Armenia are not getting adequate opioid pain treatment. As noted above, the WHO estimates that around 80 percent of cancer patients will experience moderate to severe pain at the end of life and will require morphine for an average period of 90 days before death.[45] In contrast to these estimates, from 2010 through 2012 Armenia consumed an average of 1.1 kg of morphine per year.[46] This is sufficient to adequately treat moderate to severe pain in about 180 patients with terminal cancer or AIDS, which is about 3 percent of those estimated to require such treatment in Armenia.[47]

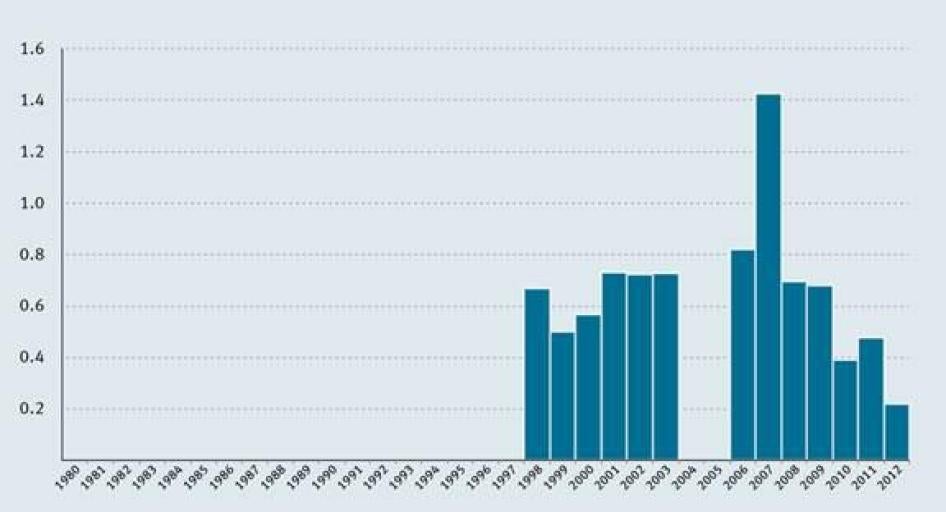

Consumption data reported by the Armenian government to the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) shows a clear decline in per capita consumption of morphine in the country in the last five years, in contrast to significant increases in the use of the medicine globally and in the region over the same period (see Chart 1. Armenia Morphine Consumption 1980-2012). In 2012, Armenia used less than 0.25 milligrams of morphine per person, 50 times less than the European average and 25 times less than the global average.[48] Given rising cancer mortality, the decline in morphine usage suggests that the gap between the need for opioid medications among cancer patients in Armenia and actual access is growing rapidly.

Chart 1. Armenia Morphine Consumption (mg/capita) 1980-2012[49]

Data collected by Human Rights Watch from nine polyclinics throughout Armenia shows that only 47 patients (i.e. less than 8 percent) out of 594 who died of cancer in 2011 received strong opioids before they died (see Table 2).

Moreover, as described elsewhere in this report, those who do receive opioid analgesics in Armenia generally do so for far fewer than 90 days. This suggests that many patients in Armenia who face moderate to severe pain are started late on opioids, do not receive the medication in sufficient quantities, or do not receive the medication at all even when it is available.

Table 2. Population, Cancer Morbidity, and Access to Opioids[50]

|

District |

Population Residing in the Area[51] |

Number of Registered Cancer Patients for 2012 |

Cancer Mortality for 2011 |

Number of Patients Who Received an Opioid Analgesic in 2011 |

|

Yerevan Polyclinic no.1 |

25,000 |

177 |

41 |

2 |

|

Polyclinic no. 4 |

26,000 |

400 |

18 |

4 |

|

Polyclinic no. 17 |

44,000 |

492 |

98 |

6 |

|

Polyclinic no. 9 |

20,000 |

239 |

73 |

12 |

|

Polyclinic no. 14 |

80,000 |

>2,000 |

132 |

3 |

|

Ararat Clinical Center |

40,000 |

340 |

No data |

2 |

|

Yeghegnadzor town polyclinic |

No data |

288 |

29 |

6 |

|

Abovyan District |

112,000 |

937 |

153 |

12 |

|

Dilijan Medical Center |

22,000 |

250 |

50 |

2 |

The Suffering Caused by Untreated Pain

Patients’ Suffering

Sixty-one-year-old Lyudmila, the retired kindergarten teacher quoted at the beginning of this report, discovered a lump in her breast around 2002, but did not seek medical help for about five years. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2007, when the tumor was inoperable and the cancer had already spread to her armpit and left shoulder. Lyudmila started to develop severe pain in 2010. When Human Rights Watch interviewed Lyudmila in 2012 she was receiving one ampoule of omnopon (an opioid analgesic similar to morphine) per 24 hour period, which was enough to sooth her pain only for two hours, while she continued to experience excruciating pain for the rest of the day.

Lyudmila explained that pain never fully leaves her, but when it decreases she feels like a normal person, able to communicate with her children and do some household work, but she said:

[when] pain attacks start unexpectedly and I start screaming and become a different person. When my hand starts burning like I hold it over a fire, I know the pain attack is about to start. When it starts I lose verbal communication skill and can only point to things with my right hand. I have the pain attacks every night, but sometimes it happens also during the day. Often I drink really hot water as it helps me to forget about the pain for a bit. It’s inhumane pain, unbearable pain for a human being.[52]

Seventy-five-year-old Tigran T., a Vanadzor resident, is a father of two and grandfather of five. He developed sudden pains in the shoulder area in 2011, and was soon thereafter diagnosed with a malignant tumor. He explained to Human Rights Watch that usually he had a high tolerance for pain, but never before had he felt anything like the pain from the tumor:

The pain starts in the back then the shoulder, continues to the right hand and I can’t move my fingers any more. I’ve seen a lot of pain in my life, but this pain is nothing I’ve felt before. I can’t lie on my side longer than five minutes. The pain gradually goes away when I get an injection [with an opioid analgesic], but never fully, and in about four hours it comes back again. I can’t do without strong pain killers.[53]

In 2008, Gayane G., a 46-year-old widow, was diagnosed with a rectal tumor that later spread to her bones. She had two surgeries and underwent a round of chemotherapy and eight rounds of radiation therapy, before she was referred for symptomatic treatment in 2011. That was when she developed severe pains. At the time Human Rights Watch visited her, Gayane was receiving tramadol pills (an opioid analgesic that is generally not sufficiently potent to treat severe pain), which did little to mitigate her pain. She explained:

The pains are unbearable; I cry, scream, feel like I’m walking on fire all the time. My left side fully and my left leg would ache. I try to endure the pain when someone is at home, but when I am alone, all I can do is cry… I can’t sleep at nights and can only do so after several sleepless nights, when I am fully exhausted. I live in pain all the time, as if the pain is with me always. It’s part of my life.[54]

Karine K., a resident of Ararat, has four children and six grandchildren. She worked as a nanny in a local kindergarten her entire adult life. She had surgery in 2009, when she was 57, for an abdominal tumor, and was in remission for three years. In 2011 she developed severe pain, 8 on a scale of 10, as she described to Human Rights Watch:

I felt like I was walking on needles. The pain would start from my hip and extend down to the entire right leg. I felt really bad, crying all the time. I did not know what sleep was during those pains. All I could dream of was a time when the pain would disappear, so that I would feel free. I felt so bad that I wanted to die; once I even asked to be given something so that I could die.[55]

Like Karine, several others told us that they wanted to end their lives to stop the pain, prayed for death, or told doctors or relatives that they wanted to die. As a doctor involved in a palliative care pilot project explained, often patients ask him for enough medication to allow them to die without pain. He said: “I tell them that I’ll prescribe you pain medication and let’s get back to the issue afterwards. And when the pain is gone, they don’t remember it anymore.”[56]

Families’ Suffering

The toll on family members caused by their loved ones’ untreated pain can be severe. As a daughter of 62-year-old Syranush S., who was suffering from an abdominal tumor, explained to Human Rights Watch, she feels she wants to die when seeing a person so dear to her in excruciating pain. She went on to say that her mother experiences sudden mood swings associated with pain:

My mother is a very kind person, loves to play with her grandchildren, when not in pain, she is lively, jokes, takes care of herself, makes coffee or something sweet for everyone, but when pain strikes she can’t cope, she becomes very nervous, does not want to see anyone, including kids.[57]

Another person who lost two family members to cancer, told Human Rights Watch, “When someone is sick in a family, everything is on the shoulders of his or her relatives, finding doctors, treatment, drugs…. You really need someone to support the relatives in such situations. When we were sent for symptomatic treatment, we did not get any guidance, any instructions on what to expect or how to help.”[58]

The Positive Effect of Palliative Care Pilot Projects

From 2011 to 2013 the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, together with the Open Society Institute Assistance Foundation Armenia and the Health Ministry, ran four palliative care pilot projects in Armenia.[59] Two operated in Yerevan (one in the National Oncology Center, and another one at the University Hospital), while two others operated in the towns of Ararat and Vanadzor. The projects’ main goal was to establish model palliative care programs, and estimate its costs and effectiveness in order to eventually replicate them throughout Armenia’s public health care system.[60]

In the first year, the pilot project offered symptomatic treatment and psychological support services to a total of 132 patients and their families, and dispensed pain medication, including opioids, in line with WHO guidelines.[61] An assessment of the project conducted in 2012 found improvement in the patients’ pain management and quality of life.[62] The assessment report, however, acknowledges the limitations of its own findings, stating that patients’ experiences were not measured against those of a control group.[63]

Human Rights Watch visited all four pilot project sites and interviewed doctors, nurses, and other medical personnel involved in the project implementation. We also interviewed over a dozen of patients who participated in the projects. All patients and families spoke highly of the care they were receiving and described the transformative impact palliative care had on their quality of life. They described stark differences before and after they started receiving palliative care. One family member of a patient suffering from cancer told Human Rights Watch that she found pain treatment to be the “key and most important component of palliative care,” which had a transformative effect on everyone involved.[64]

Fifty-five-year-old Satenik Alexanyan discovered a tumor in her breast in 2011. Because the tumor was inoperable, she underwent six rounds of chemotherapy, after which a wound opened up on her breast that would not heal. At that point she developed severe pain in her left arm and hand:

It was a constant pain. I wanted to sleep, but could not, the pain would not let me. This lasted for a year or so. I bought some [over-the-counter] pain killers myself, but they would not help for long. When I told my doctors about the pain, they were telling me that it was normal; that’s how it should be.[65]

Satenik’s oncologist referred her to the palliative care pilot project in the Ararat Regional Hospital. When Human Rights Watch interviewed Satenik, she was still a patient with the pilot project and was getting tramadol, a weak opioid, and benefitting from psychosocial services, the combination of which helped her manage her pain:

I did not want to see anyone or do anything before. I was in another world. When I had pain, I could not feel anything else. I could not even hear anything. Then these people [referring to medical personnel involved in the pilot project] started to come, talk to me. They helped me to come back to this world. It’s good that there is such a group. They helped me a lot. I feel better.[66]

Karine K., whose experience with pain, as described above, led her to feel suicidal, also participated in the pilot project in Ararat.[67] She started receiving opioids after enrolling in the program in June 2012. Karine described the stark difference the pain medication and palliative care made in her life:

I used to be very depressed. I find the talks with them [palliative care group members] very useful. They make me want to live longer. I now want to live for my grandchildren.[68]

While relieving pain is a critical part of palliative care, many patients participating in the pilot projects highlighted human attention and interaction as key components they appreciated most.[69] For example, a patient from town of Ararat said that staff of the palliative care group brought “hope and faith” and she particularly valued “human interaction.” “They come and talk to me, spend time with me,” she explained.[70]

The family member of one patient recalled how surprised she was when palliative care staff members were calling proactively, inquiring, and listening to what the caregivers had to say; “she [palliative care group nurse] was always very calm, very supportive. I particularly liked their humanity,” she said.[71]

III. Comparing Armenia’s Pain Treatment Practices with WHO Principles

The WHO Cancer Pain Ladder, a treatment guideline first published in 1986, is an authoritative summary of international best pain treatment practices.[72] Based on a wealth of pain treatment research that spans decades, it has formed the basis for cancer pain treatment in many countries around the world. It has also been used successfully to treat other types of pain.[73] The treatment guideline is organized around five core principles for treating pain (see Table 3). The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) have also developed cancer pain treatment guidelines that follow these same core principles.[74] If followed, WHO estimates, the ladder can result in good pain control for 70 to 90 percent of cancer patients.[75]

Under the right to health, governments must ensure that pain treatment be not only available and accessible, but also that it be provided in a way that is scientifically and medically appropriate and of good quality.[76] This means that health care providers should provide pain management in a way that is consistent with internationally recognized standards. Governments, in their turn, should create conditions which allow health care providers to provide such treatment.

This chapter describes the five core principles and summarizes how standard pain treatment practices in Armenia deviate fundamentally from them.

Table 3. Comparing the Core Principles of Cancer Pain Treatment with Armenia’s Pain Treatment Practices

|

WHO Recommendation |

Armenia’s Practice |

|

Principle 1: Pain medications should be delivered in oral form (tablets or syrup) when possible. |

Patients receive morphine by injection only. Oral morphine is not available or registered. |

|

Principle 2: Immediate release pain medications should be given every four hours. |

Most patients interviewed by Human Rights Watch received morphine once or twice per day. Oncologists could recall only a few cases of higher dosages. |

|

Principle 3: Morphine should be started when weaker pain medications prove insufficient to control pain. |

Many oncologists in Armenia interviewed by Human Rights Watch suggested that strong opioids can be prescribed only to a dying patient in his/her last days of life. Cancer mortality and opioid prescribing data from nine Armenian polyclinics show that in 2011 only 7.9 percent of terminal cancer patients attended by those clinics received a strong opioid analgesic, whereas research suggests about 80 percent of people with advanced cancer suffer from moderate to severe pain and may require opioid analgesics. |

|

Principle 4: Morphine dose should be determined individually. There is no maximum daily dose. |

All oncologists interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that when they start patients on morphine they start them with one ampoule, irrespective of need. If they were to increase the dosage to two ampoules they would do so only after two weeks. |

|

Principle 5: Patients should receive morphine at times convenient to them. |

Patients can take the little morphine they are given at a convenient time for them. Most said they take it at night so they can at least sleep for some hours. This means many suffer with inadequate pain management throughout the day. |

Principle 1: “By Mouth”

If possible, analgesics should be given by mouth. Rectal suppositories are useful in patients with dysphagia [difficulty swallowing], uncontrolled vomiting or gastrointestinal obstruction. Continuous subcutaneous infusion offers an alternative route in these situations. A number of mechanical and battery operated pumps are available.

—WHO Treatment Guideline[77]

The first principle of the WHO cancer pain treatment guideline reflects a fundamental principle of good medical practice: the least invasive medical intervention that is effective should be used when treating patients. As injectable analgesics provide no benefit over oral pain medications for most patients with chronic cancer pain, the WHO recommends the use of oral medications. Also, using oral medications eliminates the risk of infection that is inherent in injections and is particularly elevated in patients who are immuno-compromised due, for example, to HIV/AIDS, chemotherapy, or certain hematologic malignancies. Hence, oral morphine, which the WHO considers an essential medicine that must be available to all who need it, is the cornerstone of the treatment guideline.[78]

When patients cannot take oral medications and injectable pain relievers are used, it recommends subcutaneous administration (under the skin) to avoid unnecessary repeated sticking of patients.[79]

Principle 2: “By the Clock”

Analgesics should be given “by the clock,” i.e. at fixed [four hours for immediate release] intervals of time. The dose should be titrated against the patient’s pain, i.e. gradually increased until the patient is comfortable. The next dose should be given before the effect of the previous one has fully worn off. In this way it is possible to relieve pain continuously.

Some patients need to take “rescue” doses for incident (intermittent) and breakthrough pain. Such doses, which should be 50-100% of the regular four-hourly dose, are in addition to the regular schedule.

—WHO Treatment Guideline[80]

The second principle reflects the fact that the analgesic effect of immediate release morphine lasts four to six hours. Thus patients need to receive doses of morphine at four-hour intervals to ensure continuous pain control. Slow release morphine, which is often used once a patient is titrated to the proper dose, should be given at the manufacturers recommended intervals (usually 8 to 12 hours).

Principle 3: “By the Ladder”

The first step is a non-opioid. If this does not relieve the pain, an opioid for mild to moderate pain should be added. When an opioid for mild to moderate pain in combination with non-opioids fails to relieve the pain, an opioid for moderate to severe pain should be substituted. Only one drug of each of the groups should be used at the same time. Adjuvant drugs should be given for specific indications….

If a drug ceases to be effective, do not switch to an alternative drug of the same efficacy but prescribe a drug that is definitely stronger.

—WHO Treatment Guideline[81]

According to the WHO guideline, the intensity of the pain should determine what type of pain medications a patient receives.

For mild pain, patients should receive over-the-counter medications like Ibuprofen or Paracetamol; for mild to moderate pain a weak opioid, like codeine or tramadol; and for moderate to severe pain a strong opioid, like morphine or methadone. If over-the-counter pain medications or weak opioids are ineffective or pain is severe, a stronger type of pain medication should be provided.

The guideline emphasizes that “the use of morphine should be dictated by the intensity of pain, not by life expectancy.”[82]

Principle 4: “For the Individual”

There are no standard doses for opioid drugs. The “right” dose is the dose that relieves the patient’s pain. The range for oral morphine, for example, is from as little as 5 mg to more than 1000 mg every four hours. Drugs used for mild to moderate pain have a dose limit in practice because of formulation (e.g. combined with ASA or paracetamol, which are toxic at high doses) or because of a disproportionate increase in adverse effects at higher doses (e.g. codeine).

—WHO Treatment Guideline[83]

Pain is an individual experience. Different people perceive pain differently; they metabolize pain medications in different ways; and cancers vary from person to person, leading to vastly divergent types and intensities of pain. With so many variables, only an individualized approach to pain treatment can ensure the best relief to all. The WHO therefore recommends that doctors “select the most appropriate drug and administer it in the dose that best suits the individual.”[84]

Finding the right dose of morphine for the individual patient is crucially important: if the dose is too low, the patient's pain will be poorly controlled, if too high, the patient will experience unnecessarily severe side effects, including drowsiness, constipation, and nausea. With the right dose, relief is maximized, side effects are minimized.

Slow release morphine (currently not available in Armenia) is often used once a patient’s dose has been properly titrated. It is much more convenient for patients and their care givers as it provides relief over a longer period of time, allowing them, for example, to have a full night’s sleep without having to take medications in the middle of the night.

Principle 5: “Attention to Detail”

Emphasize the need for regular administration of pain relief drugs. Oral morphine should be administered every four hours. The first and last dose should be linked to the patient’s waking time and bedtime. The best additional times during the day are generally 10:00, 14:00 and 18:00. With this schedule, there is a balance between duration of analgesic effect and severity of side effects.

—WHO Treatment Guideline[85]

To ensure quality of life for patients with pain, it is important not only to get pain medications regularly but to get them at times that fit their schedule. In order to maximize sleep at night, for example, patients should take their medications shortly before bed time.

Principle vs. Practice

Due to the many obstacles documented in Chapter IV of this report, few patients have the luxury of taking opioid medication in a manner that allows them to benefit maximally from its effects.

First, oral morphine is not available at all in Armenia. In fact, it is not even a registered medication.[86] Clinical palliative care guidelines clearly recommend against the use of intramuscular injections for pain relief in favor of oral medications.[87] The authorities briefly allowed the use of methadone—an oral synthetic opioid often used in substitution therapy for drug addiction—at two palliative care pilot project sites. Marine Khachatryan, whose mother participated in one of the pilot projects, recalled how her mother suffered from severe pain for almost a year because she would panic at the thought of needles and could not take injectable opioids. She was diagnosed in 2010 with stage four abdominal cancer and underwent several rounds of chemotherapy that were not successful. In 2011 she developed severe pain, “it was a permanent pain,” Marine recalled.

She could not walk and she would scream from pain. She was prescribed injectable Tramadol, but we could not administer it as she was so afraid of needles. It was only after she was included in the pilot project and started receiving methadone that she started to feel normal again. For six hours after taking methadone, she would be calm and communicate with us again. She died a month after she started to receive methadone, but that was the only month in several years that she slept like a normal person.[88]

Second, while the WHO recommends that injectable pain relievers should be injected under the skin, standard practice in Armenia is to give morphine by intramuscular injection, which often results in a large number of unnecessary intramuscular injections. Such injections can become difficult as some patients are emaciated due to their illness and have little muscle tissue left. As one doctor put it, “sometimes you don’t know whether you end up injecting in muscle or bone. If there’s no muscle tissue at all, which also happens, then it’s a problem.”[89] One oncologist told us that she does not like prescribing injections, as she herself dislikes injections and does not want others to suffer from them.[90] Another explained that there are cases when relatives of a patient refuse it, as injections are associated with pain and they do not want to cause further pain to the patient, and prefer to use weaker, oral pain killers.[91]

Human Rights Watch interviewed several patients and family members of patients, like Marine Khachatryan, who refused to take injections because of their severe fear of needles.

Third, in stark contrast to principles 2 through 5, doctors almost never perform clinical titration of pain medication; in other words, they do not seek to determine the right dose for each individual patient. Nearly all oncologists interviewed for this report said that if they start a patient on opioids, they more or less automatically start with a dose of one ampoule daily, even though there is no regulation limiting the initial daily dose of opioids. Almost all patients Human Rights Watch spoke to who were prescribed opioids received an initial dose of one ampoule per day which, they said, was not enough to mitigate their pain around the clock. A few said they were started on two ampoules.

Many doctors said they would increase the dosage to two per day only about two weeks later, even if it was clear that the single ampoule was insufficient to control the patient’s pain prior to two weeks. An oncologist in one of Yerevan’s polyclinics explained to Human Rights Watch:

We start with one ampoule of morphine and increase later if need be. In about two weeks or twenty days we usually increase the dosage. This might not be very humane, but that’s how it is. We know that 1 ampoule is enough for 4 to 6 hours, but we always start with 1 ampoule and give other painkillers too. I might not agree with it, but that’s how it is.[92]

Although Armenian regulations do not set out a dosage limitation for opioids, in practice there is an informal understanding among oncologists that no more than 10 ampoules can be prescribed per prescription.[93]

Another Yerevan-based oncologist said that in order to extend the effects of morphine, oncologists split one ampoule into two parts and have it administered twice during a day, supplemented with other weaker pain medications: “We start with one ampoule and then increase gradually, maybe in a month or 20 days. With one ampoule, we prescribe half in the morning and half in the evening. The minimum period before we can increase is one week.”[94]

Health care workers and patients told Human Rights Watch that they often supplement opioids with weaker pain medications, weak opioids, muscle relaxants and sedatives, to try to dull the pain in the intervals between morphine doses. However, these are often not potent enough or even appropriate to provide effective relief and expose patients to unnecessary side effects. For example, a physician in a southern town of Armenia told Human Rights Watch: “One ampoule is not enough, we know. But we combine opioids with other analgesics, like Ketonal, Diclofenac, and others.”[95]

While the WHO treatment guideline provides for the use of weak pain medications and other adjuvant medications in addition to a strong opioid analgesic to enhance the latter’s analgesic effect or treat specific problems, they are not recommended to be used as an alternative as they are incapable of providing adequate relief.[96]

Because of these practices, many patients with life-limiting illnesses have to make hard choices about how to use their dosages. For example, Lyudmila L., who was prescribed only one ampoule of opioid per 24-hour period, kept it only for nights as the dose was hardly enough for two hours and she preferred to sleep those hours. She explained:

During the day I endure the pain. What else can I do? I have a prescription only for one ampoule. I take it the way it’s prescribed.[97]

A doctor at a medical center in Abovyan, a town 16 kilometers northeast of Yerevan, who confirmed the dosage pattern described above, recalled that in the first seven months of 2012, six out of about 950 registered oncology patients received opioid analgesics, five of whom had passed away.[98] The remaining patient had had both of his legs amputated and was already receiving five ampoules of opioids a day at the time when he was registered with the clinic. The doctor felt clearly uncomfortable about this patient and explained to Human Rights Watch that once every 10 days, a family doctor would visit him unannounced, write up a report on how many empty and full ampoules he had remaining, and inform police if he had consumed more than his prescribed dose.[99]

Another doctor confirmed that it is very rare for a patient to receive opioids for an extended period of time, reflecting the common belief in Armenia that opioids can be prescribed only to a dying patient in his or her last days of life. “Usually, our patients get opioids for a week, some even less, we had a case when a patient got it for only a day before she died,” explained the doctor.[100] A pharmacy official also referred to the informal understanding among medical personnel to prescribe opioids as late as possible and at the lowest possible dosage.[101] According to the main importer of opioids, it is rare for any patient to receive opioids for longer than a month. Usually, the importer said, a patient only receives opioids for a few days or a week.[102]

Finally, pain affects not only terminal cancer patients. However, in Armenia patients who are still receiving outpatient curative treatment are not eligible for opioids; only terminal cancer patients who are referred for “symptomatic treatment” can receive opioids, and only after going through an extremely onerous process described in this report in chapter IV. Several medical personnel interviewed by Human Rights Watch stressed the prevalent belief in Armenia that opioids can only be prescribed to a dying patient for limited time.[103]

Some of the doctors interviewed by Human Rights Watch explained their reluctance to prescribe morphine out of fear that patients will become drug dependent. This fear was also expressed by some patients who refused higher doses of morphine. However, these fears are scientifically unfounded. The WHO treatment guidelines state that “wide clinical experience has shown that psychological dependence [drug dependence] does not occur in cancer patients as a result of receiving opioids for relief of pain.”[104]

IV. Medicines Availability

The WHO recommends that countries adopt a “medicines policy in order to ensure the availability of essential medicines for the management of symptoms, including pain and psychological distress, and in particular, opioid analgesics for relief of pain and respiratory distress.”[105] In 2013, the WHO created sections on pain and palliative care in its Model List of Essential Medicines and its Model List of Essential Medicines for Children. These sections contain medicines and specification for formulations that the WHO considers essential for pain management and palliative care. The 2014 World Health Assembly resolution on palliative care urges countries to “review and, where appropriate, revise national and local legislation and policies for controlled medicines, with reference to WHO policy guidance, on improving access to and rational use of pain management medicines, in line with the United Nations international drug control conventions.”[106]

Under the right to health, countries are required to ensure the availability and accessibility of all medicines included in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights holds that providing essential medicines as determined by the WHO is a core obligation that cannot be limited by claims of constraints on resources, but that states should fulfill immediately.[107]

For an opioid analgesic to be available in Armenia (or any other country), the medication first needs to be registered. As noted above, oral morphine is currently not registered in Armenia and can thus not be imported, produced, prescribed, or sold. In fact, not a single strong oral opioid analgesic (except for methadone, which is used in substitution therapy for drug addiction) is currently registered in the country, meaning that these medicines are only administered by injection, which is inconsistent with WHO recommendations.

Table 4. Opioid Analgesics Registered in Armenia

|

Name |

Dosage, Prescription Form |

Recommended Use |

Producer |

Registration Date |

Valid through |

|

Morphine hydrochloride 1% solution for infusion |

10 mg/ml; (100/20x5/) 1 ml ampoule |

Management of moderate to severe pain |

“Zdorovye narodu”, Ukraine |

05/12/2011 |

05/12/2016 |

|

Omnopon-ZN (Morphine hydrochloride, papaverine hydrochloride, codeine, noscapine, thebaine) |

11.5mg/ml + 0.72mg/ml + 1.44mg/ml + 5.4mg/ml + 0.1mg/ml; (100/20x5/) 1 ml ampoule |

Management of moderate to severe pain |

“Zdorovye narodu”, Ukraine |

07/09/2012 |

05/12/2016 |

|

Promedol-ZN (Trimeperidine hydrochloride) |

20mg/ml; (100/20x5/) 1 ml ampoule |

Management of moderate to severe pain |

“Zdorovye narodu”, Ukraine |

07/09/2012 |

05/12/2016 |

|

Fentanyl |

0.05mg/ml; (100/20x5/) 2 ml ampoule |

Anesthesia |

“Zdorovye narodu”, Ukraine |

05/12/2011 |

05/12/2016 |

|

Tramadol, solution for injection |

100 mg/2ml; (5) ampoules 2ml |

Management of moderate pain |

CRCA, Novo Mesto, Slovenia |

27/03/2012 |

27/03/2017 |

|

Tramadol, solution for injection |

100mg/2ml; (5) ampoules |

Management of moderate pain |

Hemopharm AD – Serbia |

14/09/2011 |

14/09/2016 |

|

Methadone Oral Tablets (Methadone hydrochloride) Tablets, USP |

5, 10, and 40 mg tablets |

Used in substitution therapy for drug addiction; also in 2012 it was used at palliative care pilot sites for pain management. |

Mallinckrodt Inc., USA |

26/11/2014 |

26/11/2019 |

Barriers to the Accessibility of Opioid Medications

Armenia’s drug regulations are at the heart of problems with availability and accessibility of palliative care and pain management identified in this report. The procedure for prescribing opioids is complex, time-consuming, and involves significant bureaucracy.[108] Only oncologists may prescribe opioids to outpatients, and only to cancer patients. Pharmacies and polyclinics that dispense opioids do so free of charge but must install costly security measures at their own expense. Police control over the prescription and dispensing process is tight, invasive, and generates a sense of trepidation among oncologists and pharmacists.

Such onerous regulations appear to contribute to the reluctance among many oncologists to prescribe opioid pain medication. As one former Health Ministry official explained, “One of the main problems in our system is that doctors are afraid to prescribe opioids or prescribe [inappropriately] low dosages.”[109]

This excessively restrictive and non-evidence based approach to dosage also negatively affects demand for strong pain medication and impedes suppliers from importing more opioids or registering oral opioids, as the demand is highly unpredictable.[110] According to Arpharmacia, the only company that imports injectable morphine, the usage of morphine in the country has been declining in the past five years.[111]

Limiting Prescribing of Opioids to Oncologists and Cancer Patients Only

Under regulations issued by the Health Ministry in 1994, only oncologists at local polyclinics can prescribe opioid medicines for outpatients with cancer.[112] The directive clearly states that only cancer patients under the supervision of polyclinics could be prescribed opioids and provides detailed instruction on the prescription process.[113]

In 2002 Armenia passed a revised law “On Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances,” which sets out a broad framework for the release of such medications for medical use, and authorizes the government to establish the procedures for doing so.[114] However, all oncologists interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they follow the 1994 regulations.[115] Indeed, Human Rights Watch was not able to identify any implementing regulations pursuant to the 2002 law that have changed the opioid prescription process as it is described in this report.

The 1994 regulations exclude patients with moderate or severe pain due to diseases other than cancer from receiving these medicines. Even the palliative care pilot projects described elsewhere in this report could not prescribe opioids for the 13 participating non-cancer patients who reported moderate to severe pain.[116] As noted above, moderate to severe pain is a common symptom in numerous health conditions other than cancer and the legal ban on prescribing opioid analgesics to outpatients with these conditions condemns thousands of Armenians to needless suffering each year.

Equally problematic is the unusual provision that limits prescribing of opioid analgesics to oncologists only. A 2009 study on opioid regulations in 43 countries in Europe, which did not include Armenia, found that only Montenegro and Ukraine restricted prescribing of opioids to oncologists.[117] Human Rights Watch interviewed several physicians, including anesthesiologists, who teach students and train oncologists on pain management, but who themselves are not authorized to prescribe opioids to outpatients.[118]

Armenia’s restrictive regulation goes against WHO guidance on nationally controlled substance policies, which says that “when balancing drug control legislation and policies, it is wise to leave medical decisions up to those who are knowledgeable on medical issues.” In other words, medical professionals should make clinical decisions on what medications to prescribe to what patients. The guidance also holds that “countries should ensure that availability and accessibility of controlled medicines is addressed for the following disease-specific policies: cancer control, HIV/AIDS, and mental health.”[119] Furthermore, the WHO guidance stipulates that “access to controlled medicines should not be restricted to the above groups only.”[120]

Requirement of a Biopsy-Confirmed Cancer Diagnosis

As noted above, polyclinic oncologists are responsible for registering cancer patients and providing curative or symptomatic treatment. However, in order for a local polyclinic to register cancer patients, and therefore be able to eventually prescribe strong opioid analgesics, the health care system must first confirm their diagnosis through a biopsy. In other words, a diagnosis based on clinical observation is not sufficient to initiate pain management with opioid analgesics. This highly unusual requirement condemns thousands of cancer patients to unnecessary suffering.

Only three institutions, the National Oncology Center in Yerevan and two oncology dispensaries in the towns of Gyumri and Vanadzor, have the necessary equipment and specialists to establish such diagnosis. In practice this means that in order for patients to receive opioid medication they must go to one of these three centers to have their diagnosis confirmed.