Operation Likofi

Police Killings and Enforced Disappearances in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo

TABLE OF CONTENTS

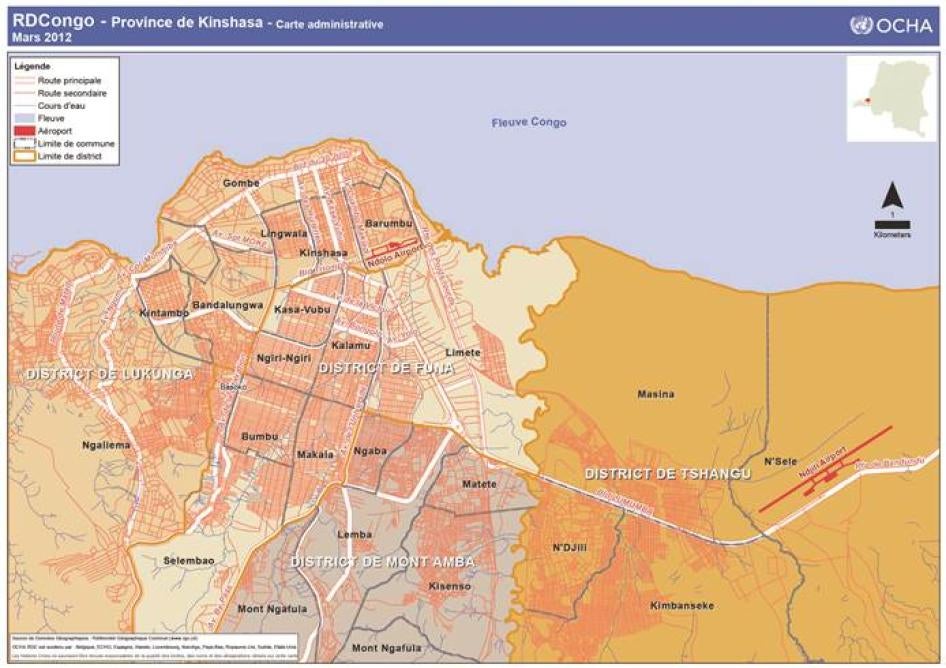

Map of Kinshasa

© 2012 OCHA. Map provided courtesy of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Summary

On November 15, 2013, the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo launched “Operation Likofi,” a police operation aimed at ending crime by members of organized criminal gangs known as “kuluna.” The kuluna had been responsible for a surge of armed robberies and other serious criminal acts across the country’s capital, Kinshasa, since 2006. They were known to carry machetes, broken bottles, or knives, and to threaten or exact violence to extort money, jewelry, mobile phones, and other valuables. The kuluna have also been used by political leaders for protection or intimidation of their opponents during elections.

Following a public commitment by Congo’s president, Joseph Kabila, in October 2013 to end gang crime in Kinshasa, the police embarked on Operation Likofi. (Likofi means “iron fist” or “punch” in Lingala, one of Congo’s national languages.) The three-month operation, between November 2013 and February 2014, showed little regard for the rule of law. The police officers who participated in the operation frequently acted illegally and ruthlessly, killing at least 51 young men and teenage boys and forcibly disappearing 33 others.

Operation Likofi reinforced a climate of fear in Kinshasa. In raids across the city, uniformed police who had covered their faces with black masks dragged suspected kuluna at gunpoint out of their homes at night with no arrest warrants. In many cases, the police shot and killed the unarmed youth outside their homes, often in front of family members and neighbors. Others were apprehended and executed in the open markets where they slept or worked or in nearby fields or empty lots. Five of those who were killed during Operation Likofi were between the ages of 14 and 17. Many others were taken to unknown locations and forcibly disappeared.

This report documents abuses committed by police who took part in Operation Likofi, including extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances, and threats against family members and other witnesses of abuses. The report is based on interviews conducted in Kinshasa between November 2013 and November 2014 with 107 witnesses to abuses, family members of those killed and forcibly disappeared, police officers who participated in Operation Likofi and other Kinshasa-based police officers, government officials and members of parliament, human rights activists, and social workers who work with street children and other vulnerable children and young adults in Kinshasa. The actual number of victims of extrajudicial execution and enforced disappearance during Operation Likofi is likely significantly higher than the 51 extrajudicial executions and 33 enforced disappearances documented by Human Rights Watch.

Congolese police taking part in Operation Likofi in Kinshasa on December 2, 2013. © 2013 Private

During the operation, police raids were widespread, and many who were targeted had nothing to do with the kuluna. Some were street children, while others were youth falsely accused by their neighbors in unrelated disputes. Some happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. In all the cases investigated by Human Rights Watch, those who were killed posed no imminent risk to life that would have justified the police’s use of lethal force.

Initially the police appeared to use their brutal tactics as a warning to others. Many of the victims were beaten and humiliated by the police in front of a crowd before being killed, and in some cases they were handcuffed and blindfolded. When the police executed a suspect, they sometimes called people to come look at the body. In many cases, they left the body in the street, perhaps to frighten others, and only later collected it for transfer to the city’s morgues.

The mother of one victim–a young man who sold clothing accessories in one of Kinshasa’s main markets–told Human Rights Watch that after the police tied up and fatally shot her son in the chest and hips, one policeman called out to onlookers in the street: “Come look, we killed a kuluna who made you suffer!” She said they then put his body in the police pickup and drove off.

When the United Nations (UN) and local human rights organizations publicly raised concerns, the police changed their tactics: instead of executing their suspects publicly, they took those arrested to a police camp or an unknown location. According to police officers interviewed by Human Rights Watch who participated in Operation Likofi, as well as a confidential foreign government report, some of the suspected kuluna abducted by the police were later killed clandestinely and their bodies thrown in the Congo River.

Suspected kuluna, or gang members, who were arrested and taken to a police camp during Operation Likofi, Kinshasa, December 2, 2013. © 2013 Private

Police involved in Operation Likofi went to great lengths to cover up their crimes. Police warned family members and witnesses not to speak out about what happened, denied them access to their relatives’ bodies, and prevented them from holding funerals. Congolese journalists were threatened when they attempted to document or broadcast information about Operation Likofi killings. Police told doctors not to treat suspected kuluna who were wounded during the police operation, and government officials instructed morgue employees not to talk to anyone about the bodies piling up in the morgue because it concerned a “confidential government matter.” A military magistrate who wanted to open a judicial investigation into a police colonel who allegedly shot and killed a suspected kuluna detained during Operation Likofi received oral instructions from a government official to “close [his] eyes” and not follow-up on the case.

Command of Operation Likofi officially alternated between Gen. Célestin Kanyama and Gen. Ngoy Sengelwa. General Kanyama was the police commander for Kinshasa’s Lukunga district until his promotion to provincial commissioner for Kinshasa in late December 2013. General Sengelwa is commander of the police force’s National Intervention Legion (Légion nationale d’intervention, LENI). Police officers who participated in the operation and a senior police official interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that, in practice, General Kanyama was the primary commander of Operation Likofi who gave the orders on how the operation should be conducted.

According to the UN as well as Human Rights Watch research, Kanyama has a long record of alleged involvement in human rights abuses, garnering him the nickname “esprit de mort” (“spirit of the dead”). He was implicated, for example, in violence committed during the 2011 electoral period, when police and other security forces killed scores of opposition supporters on the streets of Kinshasa. Kanyama officially reports to the national police commissioner, Gen. Charles Bisengimana, but also allegedly takes direction from other senior Congolese security officials.

Gen. Célestin Kanyama, the primary commander of Operation Likofi explaining the operation to residents in Kimbanseke commune, Kinshasa, November 21, 2013. Human Rights Watch urged that he be immediately suspended, pending a judicial investigation into the serious crimes committed during Operation Likofi. © 2013 Private

In a meeting with Human Rights Watch in August 2014, Kanyama rejected all allegations of extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances of suspected kuluna during Operation Likofi. He said that the cases of police misconduct during the operation only involved extortion, dismissing the reports of killings and enforced disappearances as “rumors.”

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, other senior government and police officials had a different view. They acknowledged that there were cases of police misconduct during Operation Likofi, including killings, and said that those responsible for these abuses would be held accountable.

Congo’s interior minister, Richard Muyej, and senior police officials told Human Rights Watch in October and November 2014 that some police officers had been investigated, arrested, and convicted for crimes committed as part of Operation Likofi. However, according to six magistrates assigned to the operation, interviewed by Human Rights Watch, no police officers who took part in Operation Likofi were arrested or convicted for killings or abductions, although some were arrested and convicted for extortion and other lesser crimes. Human Rights Watch is aware of eight lower-ranking police officers who are either on trial or already convicted for the crimes of murder, assassination, homicide due to imprudence or involuntary homicide committed in Kinshasa. The magistrates said none of these cases were of police officers assigned to the operation, though in some cases police and soldiers carried out murders and other crimes in Kinshasa while pretending to be part of Operation Likofi.

On the basis of the in-depth research detailed in this report, Human Rights Watch believes that the killings and enforced disappearances documented in this report were carried out by police assigned to Operation Likofi, and were not people pretending to be part of the operation.

In late September 2014, following a Human Rights Watch meeting with Congo’s interior minister, the police inspector established a commission to investigate allegations of human rights abuses committed during Operation Likofi. While a step in the right direction, the commission does not have judicial authority and lacks independence, given that it is only made up of members of the police force–the same institution responsible for the abuses and threats against family members and other witnesses, as documented in this report.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Congolese government to improve the credibility and independence of the commission, including through the involvement of civil society and international observers, and to provide information to family members on the fate or whereabouts of the victims. The government should also fulfill its international legal obligations to hold those responsible for these abuses to account, including as a matter of command responsibility. Given the gravity of the allegations regarding General Kanyama’s role in the abuses, he should be suspended immediately pending a judicial investigation.

Human Rights Watch also calls on Congo’s National Assembly to establish a parliamentary commission of inquiry, independent of the government’s commission, to investigate allegations of extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances of suspected kuluna and the government’s response.

International donors who support police reform in Congo should also take steps to ensure their funds do not contribute to human rights abuses and support efforts to prevent further human rights violations by the police.

On October 15, 2014, the United Nations published a 21-page report documenting nine summary executions and 32 enforced disappearances during Operation Likofi and calling on the government to “carry out prompt, independent, credible, and impartial investigations” and “to prosecute all alleged perpetrators of these violations, regardless of rank.” The report acknowledged that “the number of violations could be much higher since [UN] human rights officers were not able to verify several allegations due to various difficulties, in particular access to certain sites, and the unwillingness of witnesses and victims’ relatives to provide information for fear of reprisals.” The day after publication of the UN report, Congo’s interior minister said in a news conference that the UN human rights director in Congo, Scott Campbell, might be expelled. The next day the UN received an official diplomatic letter demanding Campbell’s departure from Congo.

Human Rights Watch, whose findings echo and go beyond those of the UN, calls on the Congolese government to reverse its decision to expel Campbell and to ensure that human rights investigators are able to do their work in Congo unimpeded.

Recommendations

To Congo’s Government

Protect the Rights of Suspected Kuluna in Detention

- Ensure that all criminal suspects, including suspected kuluna, are detained in recognized places of detention and are provided prompt access to a lawyer and family members;

- Ensure that all adults in detention who are suspected kuluna and credibly charged with a criminal offense are promptly brought to justice in a fair and public trial before a competent, independent, and impartial court. Release those in custody who have not promptly and credibly been charged with a criminal offense;

- Ensure that all children under 18 in detention who are suspected kuluna and credibly charged with a criminal offense receive a trial before a competent, independent and impartial child court, in accordance with Congo’s 2009 child protection law and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Release those in custody who have not promptly and credibly been charged with a criminal offense and those under Congo’s age of criminal responsibility, which is 14. Children found responsible for a crime should only be incarcerated as a last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time, and be separated from adults.

Accountability for Abuses during Operation Likofi

- Immediately suspend General Kanyama, the primary commander of Operation Likofi, and launch a judicial investigation into his alleged role in the abuses committed during the operation;

- Improve the independence and credibility of the police commission established by the police inspectorate to investigate allegations of human rights abuses committed during Operation Likofi, including through the involvement of a representative of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights and a civil society representative. The UN peacekeeping mission in Congo (MONUSCO) should be invited to participate as an observer and provide support. The commission should identify where those who were killed are buried and the fate or whereabouts of those “disappeared,” provide information to family members, and make recommendations for prosecutions. The commission should be empowered to subpoena government officials and have adequate resources and expertise to investigate individual cases, and its findings should be transferred to judicial authorities as soon as possible;

- Investigate and prosecute as appropriate, in fair and credible trials, those police officers responsible for extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, and arbitrary arrests of suspected kuluna as part of Operation Likofi, including officials who may bear command responsibility;

- Suspend with pay police officers implicated in human rights abuses during Operation Likofi pending disciplinary action or criminal prosecution. Those found to be responsible for serious abuses should be removed from the Congolese police force in addition to any other punishment they receive.

Support Families of Victims, and Protect Their Rights

- Urgently provide information to families on the fate or whereabouts of all suspected kuluna who were forcibly disappeared under Operation Likofi;

- Ensure that families of suspected kuluna who were killed be provided information about the death of their relatives and be allowed to hold funerals and mourning periods without government interference;

- Provide assistance to families of victims to obtain redress.

Improve Police Procedures

- Ensure that police carrying out arrests do not wear masks covering their faces, that they wear identifiable nametags on their uniforms, and that they drive in well-marked vehicles with license plates;

- Ensure that police carry out arrests on the basis of arrest warrants as required by law;

- Ensure that police inform those they arrest of their rights, including their right to be assisted by a lawyer.

Address the Kuluna Phenomenon through Lawful Means

- Support programs that provide education, shelter, skills training, sports, and cultural activities for street children and other vulnerable children and young adults in Kinshasa as part of a broader effort to decrease criminal activities by kuluna;

- Take appropriate legal action against politicians and their supporters who provide weapons or bribe youth in Kinshasa to disrupt their opponents’ activities.

Ensure Protection of Street Children and Other Vulnerable Children and Young Adults

- Assign the Ministry of Gender, Family, and Children as a focal point to promote the protection of street children and other vulnerable children and young adults and to monitor law enforcement practices related to street children;

- Investigate and appropriately prosecute cases of police violence against street children;

- Encourage the Ministry of Youth, Sports, Culture, and Arts to organize recreational activities and other pastimes for street children and other vulnerable children and young adults.

To Congo’s National Assembly

- Establish a parliamentary commission of inquiry, independent of the government’s commission, to investigate allegations of extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances of suspected kuluna and the government’s response. The findings should be made public and include recommendations to the government to ensure those responsible are held to account and to prevent further abuses.

To Congo’s International Donors and the United Nations

- Publicly and privately urge the Congolese government to take concrete steps to investigate, arrest, and prosecute those responsible for Operation Likofi abuses, including those bearing command responsibility. Monitor the progress of these steps regularly;

- Ensure support to Congo’s police force–including training, logistics, and other material support–does not go to units or commanders who took part in Operation Likofi, and ensure that human rights training and support to investigations and prosecutions of police abuses are central components of police reform efforts;

- Publicly and privately denounce serious human rights abuses committed by the police;

- Support the establishment of an independent commission, as described above, to provide information on the fate or whereabouts of those killed and forcibly disappeared during Operation Likofi and to support judicial proceedings against those allegedly responsible for the abuses;

- Support the establishment of a special vetting mechanism to remove police found responsible for serious human rights abuses, including during Operation Likofi;

- Support programs that provide education, shelter, skills training, sports, and cultural activities for street children and other vulnerable youth in Kinshasa as part of a broader effort to decrease criminal activities by kuluna.

I. Background

“Kuluna”

Kuluna is a term for members of organized criminal gangs in Kinshasa. They have been responsible for numerous serious crimes, including murder, armed robbery, and other violent offenses. They often carry machetes, broken bottles, or knives, and threaten violence to extort money, jewelry, mobile phones, and other valuables. They sometimes injure or kill those who resist.

Organized criminal gangs, some of whom have been used by politicians to silence or threaten their opponents, have existed in Kinshasa for at least several decades. In the 1970s, there were the “bana mayi” (“water children” in Lingala), and in the 1980s the “balado” (“thieves” in Lingala). The most notorious in recent memory were the “hibou” (“owl” in French), who operated in the 1990s during the final years of President Mobutu Sese Seko, Congo’s dictator from 1965 to 1997. The “hibou” gang members operated at night with Pajero jeeps, given to them by members of Mobutu’s regime, and were instructed to assassinate and intimidate Mobutu’s opponents. When Laurent Desiré Kabila’s rebel forces overthrew Mobutu in 1997, criminal gangs called the “pomba” (“strong, athletic” in Lingala) emerged, with athletic youth armed with machetes carrying out criminal activities, often with the encouragement of the authorities who used them for their own purposes.[1]

The kuluna phenomenon began around the time of Congo’s national elections in 2006. Joseph Kabila, Congo’s current president, came to power in 2001 following the assassination of his father, Laurent Kabila, and claimed victory during the 2006 and 2011 elections. In both elections, Kabila’s majority alliance and members of the political opposition used the kuluna to provide physical protection to candidates, disrupt demonstrations of rival parties, or target supporters of political rivals. Politicians have also paid the kuluna to participate in political demonstrations and inflate the number of their supporters. Politicians on both sides reportedly distributed money, machetes, motorcycles, and other materials to kuluna to gain their support.[2]

The kuluna are mostly teenage boys and young men in organized criminal gangs of about 10 to 20 members.[3] The gangs have names such as Armée Rouge (red army), Câble Noir (black cable), Pas d’Entrée (no entry), Etats-Unis (United States), and Cinquantenaire (fiftieth anniversary). The leader of the gang is often called the “general” and tends to be a member who is seen as the strongest, most daring, and invincible member of the group. In some cases, these leaders have committed a serious or noteworthy crime, have been arrested multiple times but escaped prison, or have a close connection to an influential political actor or police officer. The “general” is often surrounded by a ceinture (“belt” in French) of trusted bodyguards.

The “general coordination” of the gang is a group of kuluna responsible for maintaining good relations with the influential administrative authorities, police, politicians, and businessmen in their area of operation, and for getting gang members out of prison by collecting money or getting their political allies to intervene. The gang members are all those who carry out the orders of the general. Kuluna often use codes that only initiated members of their gang will understand. Some members of the police and army cooperate with kuluna on operations, and the gang members at times include relatives of police or army officers. While gangs operating in the same general area sometimes collaborate with each other, there are also rivalries among the various gangs.

The kuluna mainly operate to extort money and other valuables. In addition to carrying out armed robberies, they also disrupt public gatherings, such as funerals, weddings, concerts, and official demonstrations, yelling obscenities and stealing food, plastic chairs, and the attendees’ personal belongings. In some neighborhoods, people pay kuluna to guard a wedding or other ceremony to prevent members of rival gangs from disrupting the party. Wealthy people sometimes hire kuluna to serve as bodyguards and protect them from other kuluna.

Many kuluna come from poor families, are not in school or in regular jobs, and are frequently high on drugs when they operate at night. Some are orphans, and many grew up on the street or have older family members who are kuluna and who brought them into the gang at a young age.

Many kuluna live at home with their families, unlike Kinshasa’s street children who sleep outside or in shelters. Some kuluna are former street children who are now adults. There are an estimated 20,000 children, defined as anyone under 18, in Kinshasa who live or work on the streets.[4] While some street children commit robbery, they are rarely armed or violent; frequently they are subject to police violence and other abuses.[5] Although street children are distinct from kuluna, many were targeted by the police during Operation Likofi.

Operation Likofi

In his address to the nation in October 2013, President Joseph Kabila referred to a “new form of criminality” that was increasing in urban areas, especially Kinshasa, “creating a psychosis” among the public. “All legal means must be used by the police and judiciary,” he said, “in order to end it, quickly and definitively.”[6]

Following this statement, Kabila called meetings of the High Defense Council (Conseil Supérieur de la Défense) to discuss the government’s response to insecurity in Kinshasa and other cities. Instructions were given by Kabila to Prime Minister Augustin Matata Ponyo Mapon and the ministers of interior, justice, and defense to end the kuluna phenomenon. Acting in response to instructions from the interior minister, on November 15, 2013, the police launched a three-month operation known as Operation Likofi.[7]

In a meeting with Human Rights Watch in September 2014, Interior Minister Richard Muyej, who oversees the police, explained the rationale for the operation:

The city [Kinshasa] had become a jungle. People didn’t have the right to walk around freely, and there were serious incidents of rape, assassinations, and lots of other exactions [by the kuluna]. So we decided to start a campaign to eradicate the kuluna phenomenon. We established the cartography with all the details on the kuluna–their names, nicknames, where they operated, etc. We spent several months doing this work before the operation began. The objective was to eradicate evil, conquer the territory, defeat the fear, and make sure that it was no longer Kinshasa’s residents who were afraid but the kuluna who were afraid.[8]

Gen. Célestin Kanyama, the then-police commander for Kinshasa’s Lukunga district, was named the first commander of Operation Likofi.[9] According to UN and Human Rights Watch research, Kanyama has reportedly been involved in numerous repressive operations and serious human rights violations over the past several years, garnering him the nickname “esprit de mort” (“spirit of the dead”).[10]

Command of Operation Likofi officially alternated every 15 days between Kanyama and Gen. Ngoy Sengelwa, commander of the police force’s National Intervention Legion (Légion nationale d’intervention, LENI).[11] However, according to police officers who participated in the operation and a senior police official interviewed by Human Rights Watch, General Kanyama was the primary commander throughout the operation.[12] The operation was soon expanded to include “Likofi II,” targeting soldiers and police responsible for criminality in Kinshasa. On February 25, 2014, Congo’s interior minister announced the start of “Likofi Plus,” extending the fight against urban criminality to all of Congo’s provinces.[13] On October 16, 2014, the interior minister announced the launch of “Likofi III” to fight against the resurgence of kuluna.[14]This report focuses on abuses committed during the Likofi I phase of the operation in Kinshasa, from November 2013 to February 2014.

According to senior government officials, civilian and military magistrates were assigned to the operation to respond to cases of misconduct by police taking part in Operation Likofi.[15] Before the operation began, the police conducted a 10-day awareness-raising campaign to create fear among the kuluna and to encourage people to cooperate with the police in identifying the kuluna in their neighborhoods.[16] Many neighborhood chiefs and other local authorities provided lists of names to the police.

Following the awareness-raising campaign, when Operation Likofi began, many kuluna fled Kinshasa to other provinces or to neighboring Brazzaville, the capital of the Republic of Congo, across the Congo River. The presence of some kuluna in Brazzaville was reportedly one of the pretexts used by Brazzaville authorities to brutally expel over 130,000 citizens of the Democratic Republic of Congo since April 2014.[17]

II. Police Abuses during Operation Likofi

The police conduct in Operation Likofi was ruthless and often illegal. Around 350 police took part in the operation from various Kinshasa-based police units, including many from the National Intervention Legion (Légion nationale d’intervention, LENI) and the Mobile Intervention Group (Groupement mobile d’intervention, GMI).[18] They committed widespread human rights violations, including extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests, looting, extortion, and intimidation of family members and witnesses to abuses.

Those targeted during the operation were teenage boys and young men. The youngest victim uncovered by Human Rights Watch’s investigations was 14. They included actual kuluna as well as people accused of being local gang members, often to avenge a private dispute, and people just in the wrong place at the wrong time. A social worker for Kinshasa street children told Human Rights Watch: “The operation has often been used to settle scores. Two people can have a dispute–one will call Likofi, and the other is sacrificed.”[19] Some men and boys, including street children, appear to have been targeted solely because of their age and the way they dressed.

One resident told Human Rights Watch that local authorities spread the following message in Kinshasa neighborhoods: “If you see young men and boys in your neighborhoods who don’t belong there, that means they are running away from Operation Likofi, and you must report them.”[20] He said that local-level police commanders told the youth in their neighborhoods such things as to “be clean, and if you sleep on the street, you need to be careful–anyone who is dirty will be arrested.”[21]

Neighborhood chiefs and other local authorities drew up lists of names of suspected kuluna that they gave to the police. The police reportedly made payments to neighborhood chiefs who provided information about suspected kuluna, including information on where they lived and when they were usually at home.[22] While those listed included actual kuluna, some of those named were apparently targeted because of unrelated neighborhood disputes. Police taking part in Operation Likofi appeared to target these individuals without the police or judicial authorities having conducted any preliminary investigations.

Congo’s national police commissioner, General Bisengimana, told Human Rights Watch:

The population was sensitized that they should help the police find the kuluna, so all of those arrested were people that members of the population had denounced. Based on this, we had a very exact cartography of where all the kuluna were, their full names, and exactly where they lived and operated… I can’t say the police did any investigations after the population denounced people. The police just arrested everyone whom the population denounced and handed them over to the judicial authorities.[23]

Police taking part in Operation Likofi typically conducted raids at night and in the very early morning, between 8 p.m. and 4 a.m. Groups of 6 to 20 uniformed police officers arrived at the suspect’s home, often in blue police pickups without license plates and sometimes with L30 or L33 inscribed on the side. Police frequently wearing black face masks knocked on the door. Residents who asked who they were would typically be told “state agents,” “Operation Likofi,” or “police.” If the residents resisted, the police forced their way in. Others suspected of being kuluna were taken into custody from markets or other public places where they slept or worked.

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that the police frequently ransacked the suspect’s home, taking cell phones, money, jewelry, handbags, and other items before identifying the person on their list and dragging him out. If the individual sought after was not at home, the police sometimes took other young men or teenage boys who were at the house instead.

Those taken into police custody might be immediately shot dead outside or close to their home, or driven away in police pickup trucks to an uncertain fate. Others were arrested, jailed, and released only after their family members paid bribes. Some were eventually prosecuted in mobile court hearings, in trials that reportedly lacked credibility and fairness. [24]

Almost all of the extrajudicial killings documented by Human Rights Watch took place in November 2013, during the first two weeks of Operation Likofi. The enforced disappearances mostly took place thereafter, between late November 2013 and February 2014. According to police officers interviewed by Human Rights Watch who participated in Operation Likofi, as well as a confidential foreign government report, the police changed their tactics in December 2013 after the United Nations and local human rights organizations publicly raised concerns about the summary executions. Instead of executing their suspects publicly, those they arrested were taken to a police camp and some were later killed clandestinely on the outskirts of Kinshasa and their bodies thrown in the Congo River. The change seems to suggest that senior officials knew about the killings, but rather than act to stop them and bring those responsible to justice, authorities instead became more secretive and attempted to cover up the abuses.

The extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances took place in numerous communes[25] in Kinshasa. The majority of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch were in Kinshasa’s Funa district (including Kasa-Vubu, Kalamu, Bandalungwa, Ngiri-Ngiri, Selembao, Bumbu, and Makala communes) and Mont-Amba district (including Ngaba, Matete, Limete, and Lemba communes). Other cases were in Tshangu district (Kimbanseke, Ndjili, and Masina communes) and Lukunga district (Kinshasa, Kintambo, Mont-Ngafula, and Ngaliema communes).[26]

Extrajudicial Executions of Suspected Kuluna

Human Rights Watch confirmed 51 extrajudicial executions of suspected kuluna in Kinshasa by police who took part in Operation Likofi between November 2013 and February 2014, including of 5 boys between the ages of 14 and 17. In many of these cases, victims were shot at night in front of family members, neighbors, friends, or other witnesses. The police often returned at dawn to remove the bodies.

In some cases, the police made no attempt to hide their participation in the killings. Instead, they would call residents to gather around and look at the alleged kuluna they had killed. The mother of one victim–a young man who sold clothing accessories in Kinshasa’s main market–told Human Rights Watch that after the police tied up and fatally shot her son in the chest and hips, one policeman called out to onlookers in the street: “Come look, we killed a kuluna who made you suffer!” She said they then put his body in the police pickup and drove off. [27]

Many of the victims were beaten and humiliated by the police in front of a crowd before they were killed, and in some cases they were handcuffed and blindfolded. [28] A teacher from Selembao commune who witnessed how the police beat and killed a suspected kuluna told Human Rights Watch: “I was shocked when I saw how the police beat these young people, hitting them with the butts of their guns and making them cry out. They then threw water on their bodies, saying they were being baptized to remove their sins, and then they shot dead one of the young men.” [29]

Police frequently warned family members not to look for their loved ones’ bodies or hold a funeral or mourning period, or they would face repercussions. The father of one of the victims who was killed told Human Rights Watch that police came to his house several times to warn him not to hold a funeral or mourning period. “They told me not to bring people together for the funeral, and if I do, I would have problems with the state. Other police told me that if I organized a funeral, there would be reprisals against me.” [30]

The grandfather of another victim told Human Rights Watch:

Since our grandson was killed by the police during Operation Likofi in November 2013, my family and I, we tried again and again to organize the funeral. But whenever the aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, cousins, grandchildren, and other acquaintances and neighbors came to console us and take part in the mourning, we were visited by the police who came in police jeeps and prevented us from mourning. They told us that what we were doing was forbidden, that people weren’t allowed to gather here [at our home], and that we didn’t have the body of someone who was killed–so how could we organize a funeral?

I’ve already suffered a stroke, and there’s a risk that I might die before we organize the funeral for my grandson. What country are we in where we can’t organize a funeral when someone dies? It’s the way we can honor his memory and all he did on this earth, since we’ll never see him again.[31]

The actual number of suspected kuluna executed during Operation Likofi is likely much higher than the number of cases confirmed by Human Rights Watch. A police officer who participated in the operation said the total number of people killed during the operation far exceeded 100. He told Human Rights Watch about the orders they were given:

During all of our police parades [for the police units in Operation Likofi], they told us that if we arrested a kuluna or anyone who says something bad about the president, even if there were three or four together, they must be killed.… When we arrived at the indicated locations, we took the youth, arrested them, and, if they were stubborn, we killed them on the spot.

It was a “commando” operation, and if you refused to execute the orders, then you too were considered a kuluna and killed. In the pickup, there were six of us including the driver, the officer who sat in the front, and four who were in the back of the pickup. Among the four of us, there was one professional shooter. Before we killed someone, we had to call General Kanyama himself. He would ask where we found the person and then tell us whether we should send him to prison or kill him.

During this operation, lots of innocent people were killed, even more than the actual kuluna. It’s true that the kuluna also exaggerated, and they did bad things to people, robbing them, wounding them with machetes, and traumatizing them. But I know that if someone does something wrong, he should be arrested, tried, and convicted–not killed the way we did.[32]

The police officer said that they were ordered to shift tactics in December 2013, after public denunciations of the killings in November, including by United Nations agencies. [33] The new tactic, he said, was to abduct suspected kuluna, kill them in the outskirts of Kinshasa, put their bodies in sacks with rocks, and throw the sacks into a deep section of the Congo River. [34]

Another police officer who participated in the operation told Human Rights Watch:

The order was given to us to get all the kuluna under our control, and if they put up the least amount of resistance, to neutralize them. To kill them, we brought them to isolated or dark places, shot them dead, and then tried to get their bodies out as soon as possible. We put the bodies in sacks and took them to the morgue in our police pickups and said they were indigent when we got to the morgue. Other bodies were thrown in the [Congo] river because there were too many bodies for the morgue to handle.

The authorities gave us the orders to do this because they said these young people committed a lot of crimes in Kinshasa. There were some kuluna who we arrested in their homes, and I know there were other young people who were mistakenly identified as kuluna and they were killed too. There were many people killed, maybe 100. There are some I wouldn’t know about because we worked with a very closed system– guard the secrets and erase all proof.[35]

A third police officer who participated in the operation told Human Rights Watch:

We had to wear masks and gloves so we didn’t leave any marks and we were told to never talk about what happened during the operations. Everything was done in secret like the other police operations that are of particular importance. The order was given to us to eliminate any [kuluna] who resisted or tried to flee. During the operation, the police authorities gave us drinks, water, and food since we were working all the time. After each operation, they told us to clean our bodies well before returning to our homes.[36]

Another Kinshasa-based police officer told Human Rights Watch that many of the teenage boys and young men were first taken to a police camp called Camp Lufungula,[37] and that some were then taken out of the camp at night, executed, and their bodies were later thrown into the Congo River.[38] A witness who passed by a room at Camp Lufungula during Operation Likofi told Human Rights Watch they saw a number of dead bodies inside, possibly around 20.[39]

A social worker who works with street children in Kinshasa, including some who were targeted by Operation Likofi, told Human Rights Watch in February: “The operation is now done in a clandestine way. They take you, and you ‘disappear.’” [40]

A confidential foreign government report following an investigation by a diplomatic mission in Kinshasa, on file with Human Rights Watch, reached the following conclusions:

The first phase [of Operation Likofi] was characterized by a lot of violence without much distinction between “good or bad.” Being regarded as Kuluna was enough to be targeted by the LIKOFI units. Dozens of bodies were left behind in the streets after execution to frighten others. Hospitals were forbidden to help victims of the LIKOFI ops and the morgues were gradually filled. Resistance of the international community against the barbaric way of slaughtering people publically obliged the police to change tack.

The new approach was to arrest Kulunas, transfer them to Camp Lufungula, triage them and then transfer them to another camp along the [Congo] river where they were killed and thrown in the river. Several partially undressed bodies were picked up from the river or found along the riverbank in that period.… Figures for [those killed in] Kinshasa go from 50 up to 500.

There were obviously a lot of “slippages” like the arbitrary executions of people that had nothing to do with the whole LIKOFI issue.[41]

For the 51 extrajudicial executions documented by Human Rights Watch, the suspected kuluna were killed in front of family members, neighbors, or other witnesses at or near the place of arrest. Human Rights Watch documented 24 extrajudicial killings in Kinshasa’s Funa District, including two in Kasa-Vubu commune, 13 in Kalamu commune, two in Bandalungwa commune, four in Selembao commune, one in Ngiri-Ngiri commune, one in Makala commune, and one in Bumbu commune. 15 cases were documented in Tshangu district, including five in Kimbanseke commune, five in Ndjili commune, and five in Masina commune. In Mont-Amba district, Human Rights Watch documented six extrajudicial killings, including two in Ngaba commune, two in Lemba commune, one in Matete commune, and one in Limete commune. Six cases were documented in Lukunga district, including four in Kinshasa commune, one in Mont-Ngafula commune, and one in Kintambo commune.

It is likely that the actual number of victims is much higher than the number of cases documented by Human Rights Watch.

Threats to Journalists and Medical Staff

Journalists, doctors, morgue employees, and others were threatened by the police and other state agents and warned not to spread information about police abuses during Operation Likofi. In a number of instances reported to Human Rights Watch, the police also warned witnesses and family members of those killed not to speak to journalists or human rights activists about what had happened. After a local television station broadcast footage of a suspected kuluna who had been killed by the police during Operation Likofi, a journalist from the station said they were contacted by senior police and government officials who told them their station would be closed down if they continued to expose the police.[42] Another journalist was beaten and had his camera stolen by the police after he visited and filmed suspected kuluna at a clinic in Kinshasa who had been wounded as part of Operation Likofi.[43] A photographer said he received several threatening phone calls after he took pictures of police officers who participated in Operation Likofi.[44]

The police also issued warnings to those seeking to take the injured to local hospitals or other medical professionals. A doctor at a Kinshasa hospital told Human Rights Watch that during Operation Likofi, police told hospital workers to call them if they received young men or boys who had suffered bullet wounds. He said that when he received three such cases one evening, the police arrived early the next morning in a police pickup truck. They took the wounded young men away and said, “Doctor, don’t touch these people.” The doctor said he heard the commander of the group make a call and tell the person on the line: “Chief, we’ve picked up two packages here.” The doctor said he then exclaimed, “Two packages!” and the police officer replied to the doctor, “Yes, the order is official. We will eliminate them.”[45]

Another doctor told Human Rights Watch:

In November 2013, we received instructions from the intelligence services and the police that we weren’t allowed to treat the wounded kuluna who came to our hospital. They also said that if we had cases of wounded people who appeared to be kuluna, we should contact the authorities and they would ensure the appropriate measures were taken. During this period when they were going after the kuluna in Kinshasa, we received a lot of cases of wounded people, as well as some who were dead when they arrived. State agents in civilian clothes came to our hospital all the time to try to verify who we were treating. As a doctor, it was a very difficult situation to manage. We are health workers and the Hippocratic Oath requires us to treat the sick without any discrimination.[46]

An employee at a morgue in Kinshasa said that the bodies of people killed during Operation Likofi piled up at the morgue. The grandmother of a teenager who was killed during Operation Likofi said that when she went to get her grandson’s body from the morgue for burial, the morgue employees told her they had been instructed by government officials not to allow bodies of people who had been killed by gunfire to leave the morgue.[47] The mother of a young man who was killed during Operation Likofi told Human Rights Watch that she had wanted to go to the morgue to look for her son’s body, but people in the neighborhood warned her not to or else she too might be arrested.[48] Morgue employees also said that unidentified state agents in civilian clothes had instructed them not to talk to anyone about these cases because they concerned a “confidential government matter.”[49]

Witness Accounts

Following is a selection of accounts from family members and other witnesses of those killed during Operation Likofi. The names of victims have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect their relatives and other witnesses.

Sébastien, 15, and Arthur, 14On the early morning of November 23, 2013, police executed two boys, Sébastien and Arthur, outside a shelter for street children, near Kinshasa’s Djakarta market. A former street child, who now has his own home but continues to visit the shelter to see his friends, told Human Rights Watch: It was Saturday, around 3 a.m. I had just left the shelter when I heard a loud commotion outside. I saw a police pickup, and then the police started to fire. They hit a boy, Sébastien, who was really innocent. He sold things in a shop next to the hospital. The other, Arthur, who went by the name “Dollar,” was actually a thief. Sébastien died right away. Dollar was hit in the stomach. He cried and asked that we look for his money and take him to the hospital, but since we knew it was a government matter, we couldn’t do anything and we didn’t touch him. At 5 a.m., seven masked policemen returned, took the two bodies, and put them in the back of their pickup.[50] |

Pablo, 15Pablo, a street child who walked with a limp after being hit by a car, was killed by police who took part in Operation Likofi in November 2013. He used to spend his days at Kinshasa’s Zikida market, where he survived day to day by collecting beans that had fallen on the ground in the market and reselling them. A woman who worked at the market and knew Pablo told Human Rights Watch: He slept at Bar Ekanga [near the Zikida market], where lots of street children sleep. They took him at around 4 a.m., and then they killed him. I saw his body in the morning, at around 6 a.m. I was very upset when I learned he’d been killed. With his handicap from the accident, there’s no way he could have been a kuluna. It was [the local police commander] who had identified him, and then the Likofi police targeted him.[51] |

Willy, 19Police executed Willy, a carpenter’s apprentice, outside his family’s home early on the morning of November 25, 2013. His grandmother told Human Rights Watch: It was when I had just gotten back from a funeral wake around 12:45 am when they knocked on the door and shouted, “Open the door!” My husband asked who was there. They said they were “state agents.” My husband refused and they said, “If you don’t open the door, you will see [what happens].” My husband opened the door, and there were seven or eight policemen wearing balaclavas so we couldn’t see their faces. I started to cry and to scream. They saw one of my grandsons and said immediately, “That’s him.” I said he’s not a kuluna, and I explained that the son of one of my younger brothers, Nsimba, is a kuluna, but he wasn’t in our house. They asked my grandson if he’s Nsimba, and he said, “No, I’m Willy.” He didn’t want to go, and he said to them, “Leave me, I’m sick. It’s not me.” They replied, “We’re going,” and they dragged him out of the house. Then we heard three gunshots. I lost consciousness and the kids in the house started to cry. He didn’t die right away. He could still breathe a bit and he tried to drag himself to the other side of the avenue, just in front of our house. We couldn’t take him to the hospital because we knew that the hospitals weren’t treating people like him. He died there, and then at 6 a.m., the police pickup came. They took his body and left. Since then, we haven’t had any news, and we don’t know what they did to his body.[52] Willy’s father went to the police and asked for his son’s body back so that they could bury him. The police told him that Operation Likofi deals with the bodies themselves and would not give them back to the families.[53] |

Cédric, 25Cédric was killed during the night of November 26 to 27, 2013, near the house where he lived with his parents. His cousin was with him when he was executed: We were at a shop when we saw the Likofi police arrive and ask us, “Who are you? What are you selling?” There were about eight of them. They kicked and tripped the elderly storekeeper. He fell down and my cousin and I fled. They started to follow us, yelling at us to stop and firing their guns at us at the same time. I took one direction, and my cousin fled in another direction. The Likofi police went in the direction he took, and they caught and killed him. Cédric was shot twice in the hip and once in his arm. Another police pickup came later to take his body away.[54] When Cédric’s father tried to get his son’s body from the morgue for burial, it wasn’t there. He was told that on a prior Sunday, government officials had come to the morgue to pick up more than 25 bodies and dispose of them themselves. |

Bienvenue, 30Bienvenue, a storekeeper, was executed by the police in November 2013. His father told Human Rights Watch how the Likofi police came to their house around 1 a.m., took Bienvenue out, and shot him on the football field next to their house. Around 2 a.m., another police pickup came to take Bienvenue’s body away. When Bienvenue’s uncle asked the police authorities in his neighborhood why Bienvenue had been killed, they just told him it was part of Operation Likofi and sent him away. When the family tried to hold a mourning period for Bienvenue, intelligence agents came to the house and told them they were not allowed to organize a wake. “If my son did something bad, they need to tell us,” his father said. “But ask them why they are killing us like this. The state should protect us, but what has this become now? How are they going to compensate us? They shot dead my eldest son.”[55] |

Robert, 25In November, six police vehicles arrived at Kimbanseke bus terminus early in the morning. Some of the policemen, with masks hiding their faces, got out of their vehicles and walked towards the Kimbanseke cemetery, where they arrested a group of about 10 suspected kuluna. Lots of people were woken up by the screams of the suspected kuluna and they came out of their homes to see what was going on. One of the witnesses from the neighborhood, a 19-year-old student, told Human Rights Watch: Before the police took them to their vehicles, they threw the kuluna on the ground and started beating them with the butts of their guns and batons. The police also started tying them up. During this time, [one of the suspected kuluna] Robert tried to flee. The police caught him, and then they separated him from the group and took him to the cemetery where they shot him dead. Everyone panicked when we heard the gunshots and people starting running every which way to hide. Later we went back and I saw Robert’s body lying on the ground. His body lay there for a while in the cemetery, and then the police came back to take it away. We never learned what they did with his body.[56] |

Gilbert and Boniface, About 18 to 20 Years OldLikofi police executed Gilbert and Boniface, who lived on the street near Ngabela market, in late November 2013. A 15-year-old street child who often slept on the roof of a building overlooking the market told Human Rights Watch: When we were sleeping in Ngabela, on top of the Planet building next to the trash heap, we saw the Likofi police enter the market. There were four policemen with masks hiding their faces. They took our two older friends and tied them up, with their hands behind their backs and their legs tied together. Then they stabbed them with knives and shot them dead, each with a bullet to the chest.[57] |

Joseph, 19On November 18, 2013, around 2 a.m., seven police forced their way into the home of Joseph, a 19-year-old electrician, where he lived with his family. They found Joseph, dragged him out of the house, and shot him dead.[58] Joseph’s grandmother told Human Rights Watch: I was asleep when I heard people knocking on the door. I said it’s late, what type of people come at night like this? They responded that they were the police and that I didn’t have the right to ask any questions. What was important was to open the door or they would do it themselves. Then they broke the door open and came into our house. Everyone in the house panicked. The police then started to round up all the young men in the house and beat them. When they found Joseph, they let the others go. My grandson Joseph was the only one they took. They brought him outside the house, and a few moments later, he was shot dead in the chest. They left his body there on the avenue in front of our house, covered in blood. I cried for my grandson, and our neighbors came out to ask what had happened. We later brought his body to the morgue at Mama Yemo. A few days later, we went back to get his body for burial, but the morgue agents told us they had received orders from the government not to allow bodies of people who had been killed by bullets to leave the morgue. I got angry when they said this, and I was then arrested by police officers at the morgue who kept me there from 10 a.m. until 5 p.m. and blocked me from leaving. I then returned back home, but felt empty because we couldn’t see Joseph’s body again and cry for him as is called for in our tradition. It’s very difficult to support all of this.[59] “What I want is for justice to be done,” Joseph’s father later told Human Rights Watch, “and for the police who killed my son to be judged.” He added, “We couldn’t even organize his mourning period because the police came and told me we would be arrested if we did. They came more than four times. It’s very hard for me as his father; it’s unbearable.”[60] |

Enforced Disappearances of Suspected Kuluna

Human Rights Watch documented 33 cases of enforced disappearances of suspected kuluna by police taking part in Operation Likofi between November 2013 and February 2014. These include the enforced disappearance of four boys, ages 15 to 17. In most cases examined by Human Rights Watch, the police forced their way into the victims’ homes, dragged the suspects out of the house, and drove off with them in police pickup trucks. The police did not have arrest warrants for those they picked up. In some cases, family members were warned not to follow the police vehicle taking their relative away.

Human Rights Watch documented 15 enforced disappearances in Mont-Amba district, including 11 in Ngaba commune and four in Lemba commune. Fourteen cases were documented in Funa district, including ten in Kalamu commune, three in Makala commune, and one in Kasa-Vubu commune. In Tshangu district, Human Rights Watch documented two enforced disappearances, both in Kimbanseke commune. Two cases were documented in Lukunga district, one in Ngaliema commune and one in Mont-Ngafula commune.

Enforced disappearances are defined under international law as the arrest or detention of a person by state officials or their agents followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty, or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts. In all of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, family members have tried without success to locate their relatives or learn of their fate, visiting prisons, detention facilities, morgues, and hospitals across Kinshasa. Requests for information by the families from police officials and other government authorities have largely been ignored. In some cases, police officers demanded money, promising to provide information to family members about the whereabouts of those who disappeared, but even after the family members paid them, the police did not provide them with any information.

Following a meeting with Human Rights Watch and Interior Minister Richard Muyej, the government established a police commission in late September 2014 to investigate allegations of enforced disappearances and other abuses committed during Operation Likofi. While the commission said it had begun its work, at time of writing, family members of those who disappeared have yet to receive information about the whereabouts of their loved ones.

The UN Declaration on Enforced Disappearances describes enforced disappearances as the arrest, detention, or abduction of a person against their will or otherwise deprived of liberty by government officials, or by organized groups or private individuals acting on behalf of, or with the direct or indirect support, consent, or acquiescence of the government, followed by a refusal to disclose the fate or whereabouts of the persons concerned or by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of their liberty, which places such persons outside the protection of the law.[61]

Although a discrete crime in and of itself, enforced disappearances constitute “a multiple human rights violation.”[62] They violate the right to life, the prohibition on torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, the right to liberty and security of the person, and the right to a fair and public trial. These rights are set out in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention against Torture, and Congo, as a party to both treaties, is obligated to respect them. However, Congo has not ratified the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.[63]

An enforced disappearance is also a “continuing

crime”: it continues to take place so long as the disappeared person

remains missing, and information about their fate or whereabouts has not been

provided.

An enforced disappearance has multiple victims. Those close to a disappeared

person suffer anguish from not knowing the fate of the disappeared person,

which amounts to inhuman and degrading treatment. They may also be further

treated in an inhuman and degrading manner by authorities who fail to investigate

or provide information on the whereabouts and fate of the disappeared person.

These aspects make disappearances a particularly pernicious form of violation,

and highlight the seriousness with which the authorities should take their

obligations to prevent and remedy the crime.

Witness Accounts

Following is a selection of accounts from family members and other witnesses about suspected kuluna who were forcibly disappeared during Operation Likofi. The names of victims have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect their relatives and other witnesses.

Michel, 15On January 28, 2014, Michel was taken from his home at around 2 a.m. by a group of at least seven armed police officers in uniform with black masks covering their faces. His mother told Human Rights Watch: We were asleep in the house when we heard people knock on the door. Then they entered directly. My son was sleeping in the living room, and the police immediately handcuffed him and took him away. We asked where they were taking our son, and they told us we would never know. We looked everywhere, but we haven’t found any sign of him. My son used to work at the market with me where we sold shoes together. He had just had his 15th birthday before they took him.[64] |

Jean-Paul, 17, and Romain, 20On February 6, 2014, police arrested two cousins from their home at night: Jean-Paul, who had a mental disability, and his older cousin Romain who was studying in secondary school. The police said they were looking for a kuluna nicknamed “Pasta,” but when they didn’t find him, they took Jean-Paul and Romain instead. Their aunt told Human Rights Watch: It was at night, around 1 a.m., when we heard people entering the compound without even knocking on the door. They broke open the windows of our living room, stuck a rifle into our dog’s muzzle, grabbed my sister’s purse, and even tried to rape her. I asked them what they had come to do. They replied that they were looking for the kuluna. They asked Jean-Paul if he knew Pasta, and we said that Jean-Paul’s head isn’t well, and they should ask Romain. But instead of asking him, they started to beat Romain with their boots and the butts of their guns. They said to him, “Are you Pasta?” He said no and explained that he’s a student and could show them his school. They were wearing blue uniforms with black masks. There were more than 20 of them and they came in more than four pickups. They looked everywhere in the house for Pasta, and when they couldn’t find him, they took Jean-Paul and Romain instead. Before they left, they took off Jean-Paul’s shirt and used it to blindfold him. They also took our television, our curtains, the chairs in our living room, and 45,000 Congolese francs [US$50] from my sister. We looked for them [Jean-Paul and Romain] everywhere, but we couldn’t find them. The next day we heard that the police had killed people in another neighborhood, but when we went to check, we found it wasn’t them.[65] |

Gauthier, 24On December 18, 2013 at 3 a.m., about 20 uniformed policemen with black masks covering their faces arrived at Gauthier’s house, asking for him. His mother asked them, “What is this? What did he do? He didn’t kill anyone. He never robbed anyone.” They grabbed him and took him away, and she started to follow them. The police told her: “Leave or else we’re going to kill you.” They put Gauthier in the police pickup and left with him.[66] His mother later asked the police commander in her neighborhood why the police had taken Gauthier away. He told her he knew her son wasn’t a criminal, but said Gauthier had had a problem with other youth in the neighborhood who had called Operation Likofi to arrest him.[67] Gauthier’s parents looked in all the prisons of Kinshasa to try to find their son, to no avail. “If it’s true that he was a kuluna, they need to bring witnesses who can say that our son killed or robbed so and so,” his father told Human Rights Watch. “He has a passport, he was getting ready to travel to France, and we want to have our son back in good health.”[68] |

Matthieu, 19Matthieu, who was studying biochemistry in secondary school, was at home with his parents on December 24, 2013, when police arrived and took him away at about 3:30 a.m. His mother told Human Rights Watch: We were sleeping when they [the police] came. They said, “We’re looking for the assassins.” I replied, “There aren’t any assassins here.” There were four [policemen] in the house, and 10 or 15 outside. They had four pickups, two white and two blue. Then they saw my son. He was just wearing his boxers and a singlet, and he said to them: “We don’t have kuluna here. I have my father and mother, I study, I’m in my sixth year of biochemistry, and I’m going to take my state exams. I’m not a criminal. My father is blind, and I’m the one who takes him to the hospital. I’ve never been arrested.” I held my son close to me. Then they said to me, “If you don’t want him to go, then we will shoot you.” My child said, “Mama, let me go, they’ll try me, and since I’m not a kuluna they’ll let me go.” So they left with him like that. I went inside and got some clothes for him, and then I went to the neighborhood police office, but he wasn’t there. Nor was he at the district prison, the prosecutor’s office, Camp Lufungula, the PIR [rapid intervention police], the ANR [national intelligence agency], Kin Mazière [a former intelligence agency office]. Until today, I haven’t found him anywhere. He’s our only son.[69] |

Godé, 21Godé, a salesman at a cosmetics store in Kinshasa who recently finished his high school studies, was taken from his home by police at about 2 a.m. on December 18, 2013. When his father tried to follow the police after they dragged Godé out of their compound, a police officer warned him: “Don’t follow us or we’ll fire our guns at you.” Then they entered their police pickups and drove off with Godé. Godé’s father searched in all the prisons where he thought suspected kuluna were being held, but found no sign of his son. “The Congolese justice system calls for someone who is arrested to be tried, not killed or disappeared,” he told Human Rights Watch.[70] |

Marc, 22On December 23, 2013, Marc spent the day painting the walls of his church in preparation for his baptism ceremony. At about 3 a.m. the next morning, police arrived at his home bringing along a young man. Marc had had a dispute about a girl with the young man, who had brought the police to Marc’s home. Marc was then taken away by the police. On December 31, a policeman told Marc’s sister that if she paid him US$500, he would release Marc. Two policemen then came back to see her and she gave them US$400. They told her to wait and that they would come back with her brother. They never did. When Marc’s sister asked a senior police commander who she knew from church about what had happened to Marc, she was told that there were a lot of youth like Marc, that many of them were killed, and that in other cases, the police were awaiting orders about what to do with them. He said the place where they were being held was a “secret code” he couldn’t reveal to her. She never got any further information about the whereabouts of her brother.[71] |

Juvénal, 22On January 31, 2014, at about 3 a.m. police arrested Juvénal and several other young men who were attending a funeral wake at the neighborhood chief’s house. A few weeks later, the police came to Juvénal’s house at about 3 a.m. His mother told Human Rights Watch: There were at least 15 of them, well-armed, wearing police uniforms and black masks. They broke the light outside and told me to open the door. I opened it, and they asked, “Where’s your son?” I told them they had already taken my son, so what could they possibly want now? They told me to show them my son’s photo, so I did. They looked at Juvénal’s photo, threw it on the ground, and said they were only looking for boys. Then they held a gun to my neck and made my husband lie down on the ground. They told me to give them money. I said I didn’t have any. Then they left. I want to know where my son is. If they killed him, I want to know. If he’s in prison, I also want to know. He’s my son.[72] |

III. Government Response to Operation Likofi Abuses

The command of Operation Likofi officially alternated between Generals Kanyama and Sengelwa every 15 days. While both officers were responsible for the operation, various sources, including five police officers, told Human Rights Watch that General Kanyama was the primary commander throughout Operation Likofi who gave orders on how the operation should be conducted.[73] Three of these told Human Rights Watch that Kanyama gave orders to kill suspected kuluna.[74] One police officer said that Kanyama himself was present during some of the attacks.[75]

Kanyama has a long record of alleged involvement in human rights abuses, including during the 2011 electoral period when scores of opposition supporters were killed on the streets of Kinshasa by police and other security forces.[76] A senior government official told Human Rights Watch that although Kanyama officially reports to the national police commissioner, General Bisengimana, he “is difficult to control” and “takes orders” from other senior security officials outside the police hierarchy.[77]

In a meeting with Human Rights Watch on August 22, 2014, Kanyama rejected all allegations of extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances of suspected kuluna during Operation Likofi. He said that the cases of police misconduct during the operation only involved extortion, and he dismissed the reports of killings and disappearances as rumors. “Operation Likofi did not have the mission to kill or to execute people,” he said. “There weren’t any cases of executions. Everything that people tell you doesn’t come from the Bible. There are rumors.”[78]

Given the serious allegations regarding Kanyama’s role in the abuses, Human Rights Watch calls on the Congolese government to immediately suspend Kanyama pending a judicial investigation.

General Sengelwa declined to meet with Human Rights Watch or respond to the allegations of extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances during Operation Likofi.

General Bisengimana, Congo’s national police commissioner, told Human Rights Watch he first heard about alleged extrajudicial executions during Operation Likofi in late November 2013 when he was in the east of the country. “The orders for the operation were clear. They did not have the mandate to kill people,” he told Human Rights Watch. “Those responsible [for such killings] should be arrested and brought to justice. When we heard about the abuses … I gave the order to General Kanyama to verify the allegations and end such misconduct immediately. He gave us a report saying that, according to him, no one had been killed.”[79]

Bisengimana said he later called Kanyama to his office three times–in January, February, and April 2014–to tell him not to allow misconduct during Operation Likofi. He also said he suggested to senior government officials that a judicial investigation be opened into the actions of all commanders involved in the operation, including Kanyama, but that he was still awaiting a response.[80]

On December 9, 2013, during a meeting with Interior Minister Richard Muyej, ambassadors from countries supporting police reform and decentralization in Congo raised concerns about Operation Likofi and called on the government to ensure it was carried out in the full respect of human rights.[81] In his response to the diplomats, Muyej stated that the magistrates assigned to Operation Likofi were ensuring “strict respect of the law, relating to procedures for summons, arrest, questioning and treatment of delinquents and accused persons. They enable a certain speed in the treatment of case files.” He added: “But Kinshasa […] is also a city prone to the wildest rumors. It is therefore not surprising that you hear all sorts of things and that myths are being built around Operation Likofi.”[82]

Two days later a member of parliament asked Muyej at a National Assembly hearing about allegations of summary executions during Operation Likofi. Muyej said that there was misconduct in some cases but that in others the police were acting in legitimate self-defense.[83] Provincial parliamentarians also raised concerns with Kinshasa’s provincial interior minister during a provincial assembly meeting.[84]

During a news conference on February 25, 2014, Muyej declared Operation Likofi a success and announced that, in total, during Operation Likofi I and II (targeting kuluna as well as uncontrolled police and soldiers in Kinshasa), 925 people were taken in for questioning, of whom 593 were brought to court.[85]

At a September 4, 2014 meeting in which Human Rights Watch presented the findings of its research, Muyej maintained his position about the benefits of the operation: “After the first week of the attack, all the kuluna who were left in the city fled because they knew we had their addresses. Most fled to Equateur, Bas Congo, Bandundu, and Brazzaville. As long as the kuluna know we know who they are, they won’t have the courage to return.”[86]

Muyej, who has responsibility over the police force, conceded to Human Rights Watch that there were “some cases of misconduct, including killings,” during Operation Likofi, but said that these were isolated cases of police not following orders. He said “there was no strategy to carry out secret operations and kill people.”[87]

Regarding the large number of deaths of suspected kuluna, Muyej said:

We know there were cases of misconduct [during the operation], and we ensured that the police responsible were arrested. But you have to also admit that there are cases of popular justice, where kuluna are killed by members of the population.… There are also cases of bandits pretending to be police.… And a lot of the allegations are the result of members of the opposition and civil society trying to smear an operation that was supported by residents and the parliament.[88]

Muyej said that some policemen had been arrested and convicted for misconduct during Operation Likofi, and that he would put in place a commission under Police Inspector General Jean de Dieu Oleko Komba to investigate additional allegations of misconduct, including extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances, and ensure that family members of victims are given information about their relatives. He said that the commission would also ensure that those responsible for abuses are arrested and brought to justice.[89]

The commission was established in late September, soon after Human Rights Watch’s meeting with Muyej. Human Rights Watch met with the seven members of the commission, all police inspectors, on September 30. The head of the commission, Gen. Justin Bulowa, said: “We were instructed by the interior minister to evaluate Operation Likofi and to verify allegations of human rights violations committed during the operation.” He said he hoped their investigations would enable them “to interrogate General Kanyama and bring to justice all those responsible for these human rights violations.”[90] In mid-October, commission members said they had started to collect testimony from witnesses. While it was a step in the right direction to establish the commission, the commission does not have judicial authority and would appear to lack impartiality given that it is only made up of members of the police force–the same institution responsible for the abuses and the threats against family members and witnesses to alleged abuses.

In a meeting with Human Rights Watch on November 5, 2014, Interior Minister Muyej said that the commission was finalizing its report and that judicial proceedings were ongoing and would continue against police officers who allegedly committed crimes during Operation Likofi.[91]

Human Rights Watch is aware of nine police officers who have been on trial since the start of Operation Likofi for killings committed in Kinshasa. Of those, four were convicted of murder, assassination, homicide due to imprudence, or involuntary homicide. They received sentences ranging from two years in prison to a sentence of the death penalty.[92] One police officer was acquitted, and four trials are ongoing at the time of writing in early November 2014. Human Rights Watch also knows of one police officer who was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison for abduction and another who is on trial for abduction.[93]

The interior minister and senior police officials suggested to Human Rights Watch that the police officers arrested and convicted for these crimes were police officers who took part in Operation Likofi. Magistrates assigned to Operation Likofi gave a different explanation. In a meeting with Human Rights Watch at the Ministry of Interior on November 6, 2014, six military and civilian magistrates assigned to Operation Likofi told Human Rights Watch that the police officers who had been arrested or tried for killings or abductions had not participated in Operation Likofi. They said that, in some cases, other police and soldiers in Kinshasa who did not take part in the operation carried out murders and other crimes while pretending to be part of Operation Likofi. According to the magistrates, no police officers who participated in Operation Likofi had been arrested or tried for killings or enforced disappearances, although some had been tried for extortion.[94]

While police officers and soldiers who did not take part in Operation Likofi may have carried out murders and other crimes in Kinshasa while Operation Likofi was ongoing, Human Rights Watch’s research found that the killings and disappearances documented in this report were carried out by police assigned to the operation. Witnesses described how police came to their homes to apprehend or execute young men and boys in pickup trucks with “L30” or “L33” inscribed on the side, and some witnesses recognized police officers who were known to have participated in Operation Likofi among those carrying out the killings or disappearances.