No Time to Waste

Evidence-Based Treatment for Drug Dependence at the United States Department of Veterans Affairs

Summary

They tell us not to do drugs, but how do I sleep? How do I forget what I saw? —Theresa, 44, Gulf War Veteran, Davis, California[1]

This briefing paper examines the response of the Department of Veterans Affairs to veterans struggling with drug and alcohol dependence, highlighting three programs that use evidence-based models to prevent overdose, treat opioid dependence and end chronic homelessness. These approaches incorporate harm reduction principles that “meet veterans where they are” and provides services along a spectrum to help veterans reduce the negative consequences of drug misuse, including the harm of infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis. Continued support for these programs is critically important, both within the Department of Veterans Affairs and in the form of essential funding from the United States Congress.

Research for this briefing paper was conducted between January and April 2014 and included interviews with dozens of veterans and their advocates. Human Rights Watch also spoke with doctors, administrators and social workers from the Veterans Health Administration as well as harm reduction and housing service providers. Human Rights Watch research indicates:

Expanding Veterans’ Access to Naloxone is Critical to Saving Lives from Overdose

Naloxone is a life-saving medication that can reverse opioid overdose if given to someone in the early stages of an overdose. At the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), three pilot programs informed development of a national overdose education and naloxone distribution program to provide this life-saving medication to veterans at high risk of overdose. The VHA’s plans to expand these programs should be prioritized, supported and funded without delay.

Medication-assisted Therapy is an Effective Treatment for Opioid Dependence that Should Be Accessible to Greater Numbers of Veterans

Methadone and buprenorphine are medications that, when combined with behavioral therapies, have proven to be the most effective treatment for opioid dependence while reducing HIV transmission and other negative consequences of injecting drugs. Methadone has been available to VHA patients since the 1970s, and buprenorphine has been available for more than a decade. But demand has outpaced supply, and today, only 1 of 3 veterans in VHA care who need them has access to these effective treatments. The VHA has made progress in ensuring access, particularly with increasing use of office-based buprenorphine, and veterans in VHA care have greater access to these medications than do non-veterans in the community. However, serious gaps in use of evidence-based treatment for opioid dependence should be addressed without delay.

Focusing on “Housing First” Gives Veterans a Chance to Stabilize and Rebuild their Lives

“Housing First” is a model that provides housing to the chronically homeless not as a reward for “good” behavior- usually abstinence- but as a first step toward stabilizing individuals and surrounding them with supportive services to improve their health and well-being. In 2010, the VA tested the “Housing First” model and found that the pilot programs successfully housed more chronically homeless veterans, including many with substance use and severe mental health conditions. “Housing First” is now the official policy of the VA’s partnership with the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. The VA’s plan to expand “Housing First” vouchers through this partnership should be prioritized, supported, and funded without delay.

The Department of Veterans Affairs has adopted evidence-based models because they are effective. Veterans have placed their lives on the line for their country, and their country should protect their right to health, and to life, when they come home. But implementing evidence-based responses to drug dependence is a matter of human rights as well as public health. Under international human rights law, governments are obligated to apply proven standards, best practices and evidence-based models to prevent disease, treat illness, and protect the right to health. Everyone has the right to be free of discrimination, including people who use drugs. Housing is a human right, not a reward for “good” behavior. These are principles that apply to all people regardless of whether they have served in the nation’s military. The VA provides the three models highlighted here to veterans, but they are essential for all who are drug dependent and may be at risk of overdose, in need of treatment, or without a home. By expanding and sustaining these programs the Department of Veterans Affairs can set a precedent that ultimately could be a significant contribution to protecting the right to health not only for veterans but for all Americans.

Recommendations

To the Department of Veterans Affairs and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Expand the availability of vouchers for housing using the “Housing First” model through the Housing and Urban Development-Department of Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) program without delay, ensuring that permanent housing and supportive services are available for the most vulnerable chronically homeless veterans.

- Expand outreach efforts to ensure that women veterans and others not currently engaged with VA or VHA services have access to the HUD-VASH program.

- Improve data collection on women veterans and homelessness in order to plan more effectively for the housing needs of female veterans and their families.

To the Veterans Health Administration

- Expand the naloxone distribution program without delay, ensuring that veterans at high risk of opioid overdose have access to this life-saving medication. Consider conducting outreach not only in Vet Centers but in partnership with community groups in order to facilitate easy, low-threshold access to this life saving medication for veterans, including those who may not be currently engaged with the VHA.

- Coordinate with HUD-VASH and other non-medical programs targeting veterans using alcohol and drugs in order to ensure availability of naloxone to this population.

- Intensify efforts to expand access to methadone and buprenorphine to veterans who are dependent on opioids, including expansion of telemedicine and other modalities designed to increase access to veterans in rural areas.

- Expand outreach efforts to increase utilization of health services by female veterans and ensure accessibility of gender-sensitive drug and alcohol dependence programs.

To the United States Congress

- Ensure adequate funding for initiatives to end veteran homelessness including the expansion of vouchers for the HUD-VASH program.

- Ensure adequate funding for the Veterans Health Administration to sustain expanded access to naloxone to veterans at risk of opioid overdose.

- Ensure adequate funding for the Veterans Health Administration to expand access to methadone and buprenorphine for opioid dependence treatment and harm reduction.

Introduction

Since 2001, more than 2.2 million United States men and women have served in Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation New Dawn) and Afghanistan (Operating Enduring Freedom). These campaigns represent the most sustained US combat operations since the Vietnam War, with nearly 7,000 members of the military dead and 52,000 wounded in action.[2] This all-volunteer force has experienced more repeated deployments, for longer periods of time, than any other members of the military in US history.[3] Advances in medical technology, emergency care and body armor have led to a record number of combat veterans surviving severe trauma, including burns, amputations, and other serious injuries.[4]

Many veterans are also experiencing a different kind of injury in the form of “invisible wounds” such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury (TBI) and chronic pain.[5] To treat pain, doctors are prescribing analgesic medications, primarily opioids, at unprecedented rates.[6] At the same time, there has been a dramatic increase in opioid dependence,[7] due to both prescription pain medicine and illicit opioids such as heroin,[8] and an epidemic of overdose, both accidental and intentional. In 2012, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) estimated that every day 22 veterans committed suicide.[9]

Drug and alcohol use also contribute to an epidemic of homelessness among veterans that Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) officials have called “a national tragedy.”[10]

The Veterans Health Administration

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is a part of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, also known as the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The VHA is the United States’ largest integrated health system, providing health care services to nearly 6 million veterans each year. Care is available at 151 hospitals and approximately 1400 community-based clinics, residential living sites and nursing homes. The VHA also operates approximately 300 “Vet Centers” throughout the country where veterans and their families can gather for counseling, programming, help with benefit applications and other support services. The US is divided into 21 Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISN), each of which includes major hospital facilities as well as community-based care.[11]

Generally, any veteran who served in the US military and received a discharge status other than dishonorable is eligible for VHA services. Members of the National Guard or Reserves who were called to duty under a federal court order and completed the full period for which they were called can also be eligible for VHA benefits. Levels of benefits, including whether care is provided for non-service-related conditions, differ according to categories of priority based on degree of disability, medals and distinctions earned, length and location of service as well as whether it was combat-related, and other factors.[12]

Due to lack of information, geographical location, or ineligibility, it is estimated that 1.3 million veterans do not use VHA services and have no health insurance.[13] Many are excluded based upon discharge status. A “dishonorable” discharge disqualifies a veteran from VHA benefits; discharges that are categorized as “other than honorable” discharges must be reviewed to determine whether the veteran committed certain disqualifying acts such as desertion, illegitimate absence without leave, conscientious objection, and other behavior set out by statute. [14] “Bad conduct” discharges, often based on drug and alcohol use, may be appealed for benefit eligibility but such applications are complex, time consuming, and according to advocates, rarely granted.[15]

The disqualification of veterans from pension and health care benefits based on discharge status has become increasingly controversial in recent years. High rates of PTSD, military sexual trauma, substance use disorders and other mental health issues among active duty members of the military are being recognized as important factors that influence behavior during service and impact the nature of military discharge.[16] The disqualification of veterans for health care, due to conditions stemming from their service and experiences while serving their country, is problematic and currently a topic of intense debate.

Veterans at Risk of Drug Overdose

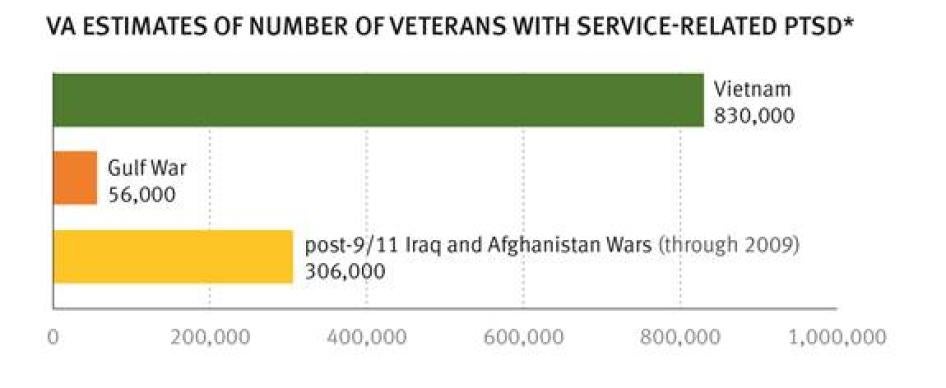

At Veterans Health Administration hospitals, half of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans report symptoms of mental illness.[17] Since 2002, more than 300,000 servicemen and women have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder at VHA hospitals and as many as 40 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans treated at VA facilities receive a triple diagnosis of PTSD, TBI and pain.[18] Post-traumatic stress disorder is a condition that can develop after experiencing or witnessing extreme emotional trauma that involves threat of injury or death.[19] Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder include intrusive memories, hyper arousal and extreme anxiety, or avoidance and emotional numbing.[20] But PTSD is not limited to veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan; the Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that 30 percent of Vietnam veterans suffer from the disorder.[21]

The chart on the following page shows the estimated numbers of veterans, who served during the Vietnam and Gulf wars, and in Afghanistan or Iraq, diagnosed with service-related PTSD.[22]

*Vietnam war estimate developed from survey taken 1986-88, Gulf war estimate from survey conducted 1995-97, and Iraq/Afghanistan estimate from survey conducted 2008. See: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp

Post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury are strongly associated with substance use and substance use disorders, both among active military personnel and among veterans upon their return home. Substance use disorders are patterns of symptoms- including increased tolerance, inability to stop using, and withdrawal- resulting from use of a substance that an individual continues to take despite experiencing problems as a consequence.[23] A study of nearly 500,000 patients at VHA hospitals during the period 2001-2009 indicated that veterans diagnosed with PTSD or depression were 4 times more likely to suffer from drug or alcohol use disorders than patients without a PTSD or depression diagnosis.[24] Among Vietnam combat veterans with PTSD, 3 of 4 have been co-diagnosed with substance use disorder.[25]

Opioids, including hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone and morphine, are controlled substances frequently prescribed for pain. Opioid use among veterans, both medical and non-medical, is on the rise, particularly among young veterans.[26] A recent study estimated that nearly 1 million veterans are taking prescription opioids and more than half use them “chronically” or beyond 90 days.[27]

In many cases, military members engaging in chronic opioid use first received them from military physicians. The Army Surgeon General reported in 2010 that more than 76,000 soldiers, nearly 14 percent of the force, were prescribed some form of opiate drug; 95 percent were taking the painkilling medication oxycodone.[28] At the VHA hospitals, 64 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with chronic and severe pain complaints were prescribed at least one opioid medication.[29] Between 2001 and 2009, pain prescriptions from military physicians quadrupled to nearly 4 million.[30]

An article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association recently reported that veterans with mental health conditions are more likely to receive prescriptions for opioids at Veterans Health Administration facilities than patients without a mental health diagnosis, and more likely to receive opioids in higher doses.[31] The prescription of pain medicines to individuals with mental health issues can be complicated. Veterans with a mental health diagnosis who are taking opioids may be more likely to engage in “high risk” opioid use- for example, mixing the opioid with alcohol or other medications- and may be more susceptible to overdose, accidents, and self-inflicted injury.[32]

Indeed, the risk of death by accidental overdose among patients at Veterans Health Administration facilities is nearly twice that among the non-veteran population.[33] Researchers attribute this elevated risk to unique factors present among veterans, including combat trauma and high prevalence of substance use disorders, but also note that this is a population with greater access to medications than the general public, as the study included only veterans actively engaged with VHA health services. Given increasing rates of overdose among the general population in the United States, which have more than quadrupled since 1990 and are now deemed an “epidemic” by the US Centers for Disease Control, any higher risk among veterans is cause for concern.[34]

In the past few years, the Food and Drug Administration has tightened regulations for prescription opioids. The Veterans Health Administration issued new policy guidelines for pain management in 2009 and guidelines for opioid prescriptions in 2010. New policy represents an effort to increase control over dosage, duration and refill procedures.[35] However, implementation varies among the 140 VHA hospitals and reports of prescriptions to veterans that appear problematic in volume or duration continue to be documented in the media.[36] The VHA also launched an Opioid Safety Initiative in October 2013 at eight VHA sites in Minneapolis. This initiative is a comprehensive program designed to monitor dispensing practices and treat pain with alternative approaches including acupuncture and behavioral therapy. The VA reports a 50 percent reduction in high-dosage opioid prescriptions since the program began.[37]

Some prescription opioid users move to heroin use.[38] This may be a result of increasingly restricted availability of prescription opioids, simple cost considerations (heroin is generally cheaper than opioid medications) or lack of access to effective treatment for opioid dependence such as methadone and buprenorphine.[39] Heroin use may further increase overdose risk among veterans as the rate of heroin overdose in the US is on the rise, increasing by 45 percent between 2006 and 2010.[40]

Opioids can be implicated in non-accidental overdose as well. Suicides among active duty military personnel have doubled since 2005, hitting a high of 350 in 2012, more than the number of troops killed in combat during that period.[41] An estimated 1,000 veterans receiving care from the VHA and 5,000 veterans overall commit suicide each year, and the Department of Veterans Affairs reported in 2012 that 22 veterans commit suicide each day.[42] Untreated mental health conditions have been identified as the primary factor associated with suicide, but homelessness has also been linked to suicide in veterans.[43]

In 2010, 63 percent of attempted suicides among active duty soldiers involved drug or alcohol overdose.[44] Drugs or alcohol toxicity also accounts for one-third of the fatal suicide attempts among soldiers.[45] Of accidental deaths among soldiers during the period 2006-2009, nearly one half were caused by substance overdose, and in 74 percent of the cases, the substance was prescription drugs.[46] Of course, the distinction between suicide and accidental or undetermined death is not a clear one in many cases. The Army Suicide Task Force notes that suicide is often under-reported due to the attendant stigma, complication of life insurance issues, religious beliefs, and the lack of evidence of intent, such as a note.[47] What is clear is that drug overdose is a primary contributor to death rates among both active duty and veteran members of the military. In a special report entitled “Uncounted Casualties: Home, But Not Safe,” the Austin American-Statesman conducted a comprehensive review of hundreds of deaths of Texas veterans during the period 2003-2011. They found that 1 of 3 had died of drug overdose, either intentionally or by accident. Most had prescriptions for the medications that killed them.[48]

For many veterans, the risk of drug overdose is heightened by the stress of readjustment to civilian life, particularly the challenge of finding jobs and housing. More than 700,000 veterans nationwide are unemployed, with African-American and Hispanic veterans out of work at higher rates than whites. Among post-9/11 veterans, the unemployment rate is 9 percent, with 246,000 out of work. One in three young veterans ages 18-25 is unemployed.[49] Estimates vary, but 100-400,000 veterans experience homelessness at some point each year, and more than 57,000 were homeless in a “point-in-time” snapshot taken in January 2012.[50] An estimated 70 percent of homeless veterans are dependent on drugs or alcohol.[51]

Recent research has focused on the heightened overdose risk of young veterans returning to low income, low opportunity, mostly minority neighborhoods.[52] These veterans describe a confluence of mental and physical pain, often treated with prescription opioids, such as the stress of finding jobs and housing, and a strong feeling of social isolation. The researchers found significant use of opioid medications both prescribed and recreational, as well as heavy alcohol use that often reflected heavy drinking patterns developed during active duty in the military. Combining opioids and alcohol is a primary risk factor for overdose, yet awareness of this lethal mixture was low among most of the study participants.

One study participant, a 22-year-old veteran with disabilities called “Jared,” had recently returned from Afghanistan:

You can’t work, you don’t have a home or apartment, you’re always in pain, you’re not making money. You’re really partying, you don’t have a life… Drink and drugs. I could see how people overdose and commit suicide or want to do more drugs, drink and other things because you don’t have anything else.[53]

The authors concluded that the narrative accounts offered by their veteran participants made a powerful case for bolstering existing educational and therapeutic programs and developing new, targeted overdose prevention efforts, in both VA and community settings.[54]

Veterans who use opioids actively told Human Rights Watch that drug use was a strategy for coping with the trauma of war:

I’ve seen things that will haunt me for the rest of my life. Of 150 guys in my unit, I was one of 8 left. I laid under dead bodies for 3 days. And they’re telling me not to use? – James, 70, Vietnam veteran, New York City[55]

How can I ‘just step up’ and stop when I have voices in my head, anxiety, and anger? —Donald, 60, Vietnam veteran, New York City[56]

It’s grief. And I have the right to grieve the way I want to. Even if that means I self-medicate. —Brian, 65, Vietnam veteran, New York City[57]

You can’t BS a veteran. Vets have been through enough already. ‘Just be straight and suck it up’ is not going to work because they’ve been through what other people can’t even imagine. —Michael, 43, Gulf War veteran, New York City[58]

Overdose Prevention at the Veterans Health Administration

My buddy Leon did two tours in Iraq. Now he ‘rocks his cardboard’ [sign] during the day and parties with heroin at night. I gave him a [naloxone] kit so he always has it on him. —Michael, 43, Gulf War veteran[59]

In response to concerns of rising opioid use, misuse and overdose among veterans, the Veterans Health Administration has initiated a national Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) program to distribute naloxone to patients. Naloxone is a life-saving medication that reverses overdose from opioids if administered in time. As overdose incidents evolve within the course of 1-3 hours there is often time to intervene.[60]. An opioid agonist, naloxone is a safe non-controlled prescription medication that has no potential for abuse or overdose. For more than four decades, emergency rooms have administered naloxone routinely for opioid overdose patients. Naloxone can be safely and easily administered by medical and non-medical personnel either by intranasal application (like a nasal spray) or intramuscular injection via syringe.[61] The World Health Organization, the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Medical Association and other health experts have endorsed making naloxone widely available to medical personnel and trained lay persons in order to prevent death from opioid overdose.[62]

The VHA began distributing naloxone kits to veterans at risk of overdose in August 2013 at the Louis Stokes Cleveland Veterans Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Eric Konicki, Chief of Psychiatry at the medical center, described the origins of the program:

We had a number of veterans returning from the Middle East who were in residential treatment for opioid dependence. They were free to come and go during reasonable hours when they were not in programming. We had several distressing incidents of these patients obtaining heroin when off the unit, and several overdoses that required transfer to intensive care.[63]

Dr. Konicki began training the doctors, nurses, and staff of the residential treatment programs to become providers of naloxone. Patients whom they considered to be at the highest risk of overdose- those with histories of opioid use disorder who had passed outside of the facility during treatment or were being discharged- each received a naloxone “kit.” Specifically, these patients were provided a brochure containing overdose prevention information, including warnings on the danger of mixing opioids and alcohol; a pocket-sized naloxone “kit” containing 2 mg vials of naloxone for intranasal application; and training for themselves and family members (if requested) on how to use the naloxone in case of overdose.[64] Patients were advised that if they are going to use opioids, they should try to have someone else present who can assist them in case of an overdose incident. As of April 2014, more than 30 kits had been distributed at the Cleveland VA facility, and at least one has been used to reverse an overdose.[65]

Naloxone pilot programs that informed the OEND program include those in California (San Francisco and Palo Alto), Georgia (Atlanta), Ohio (Cincinnati, Cleveland and Dayton), Rhode Island (Providence) and Utah (Salt Lake City). These programs largely target patients in residential drug treatment centers at the VA who are deemed to be at high risk of opioid overdose. Dr. Elizabeth Oliva, health sciences specialist and program evaluator for the VA, leads the OEND Work Group which has undertaken the mission of expanding the VA’s naloxone distribution capabilities. In addition, Dr. Oliva has received a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs to evaluate the results of the initial OEND pilots in order to identify barriers to expanded implementation and to inform the development of a national plan for implementing naloxone distribution throughout the VHA system. Dr. Oliva is optimistic about the political will and capacity to scale up the naloxone program, perhaps even by the end of 2014. “I can’t give you a specific timeline,” said Dr. Oliva, “but we are moving fast.”[66]

The VHA is making both the intranasal and intramuscular applications of naloxone available to accommodate patient preference.[67]Many consider the nasal application, similar to a nasal spray into each nostril, more accessible for patients and non-medical personnel than the injection of a syringe into an arm or leg muscle.[68] However, the intramuscular injection is the format that has been most widely used in the last decade, as the intranasal format is relatively new. Cost estimates vary and depend on purchasing methods but generally the intramuscular and intranasal kits cost from 35-50 dollars.[69] Training for both the intranasal and intramuscular applications can be accomplished in minutes.[70]

Between 1996 and 2010, naloxone in both the intramuscular and intranasal injection formats was distributed to more than 50,000 persons in 15 states and the District of Columbia primarily through community organizations. More than 10,000 individuals who overdosed were treated with naloxone during that period.[71] Today, 23 states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation expanding access to naloxone for emergency first responders and lay administrators.[72] As the VHA program expands, targeted groups should include veterans in outpatient treatment programs, those who use opioids recreationally, and those who have stopped using for periods of time and then return to opioid use, as people in each of these categories are at risk for overdose.[73] For example, veterans released from jail or prison are at risk for overdose upon release as a result of reduced tolerance after periods of abstinence.[74] Outreach can be conducted not only in Vet Centers but in partnership with correctional facilities and community groups whose members include veterans in order to facilitate easy, low-threshold access to this life saving medication, particularly for veterans who may not be currently engaged with the VHA.

Most importantly, the naloxone pilot programs demonstrate awareness at the VA that veterans are in urgent need of harm reduction services in response to increasing opioid use and risk of overdose. For many veterans, opioid dependence will be a chronic, relapsing condition.[75] The VA rightly recognizes that treatment is important, but the first priority should be to keep veterans alive. Dr. Konicki told Human Rights Watch, “We want to educate veterans so if they are going to use, they use more safely.”[76]

Evidence-Based Treatment for Opioid Dependence at the Veterans Health Administration

I’ve been on methadone for years now. Some people say to get off it, but I don’t think I would live long if I did. —Barry, Vietnam veteran, 59, New York City

Medication-assisted therapy (MAT) for opioid dependence, for example with methadone or buprenorphine, prevents opioid withdrawal, decreases opiate craving, and diminishes the effects of illicit opioids. Often called opioid substitution therapy or opiate agonist therapy, MAT is one of the most effective and best-researched treatments for opioid dependence. Once a patient is stabilized on an adequate dose it relieves cravings and permits a person to function normally.[77] According to the American Society for Addiction Medicine, “Pharmacotherapies for opioid addiction, used in concert with behavioral therapies and other recovery services (commonly known as medication-assisted therapies) have been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of opioid addiction.”[78] National and international studies have consistently found medication-assisted therapy to reduce heroin use and retain patients in treatment more effectively than other therapies.[79]

While medication-assisted therapies are among the most effective treatment for opioid dependence, they also play a crucial role in reducing the transmission of disease among injection drug users. A recent review of studies from nine countries found a 54 percent reduction in transmission of HIV among people who inject drugs attributable to the use of medication-assisted therapy.[80] The World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) have each supported the expansion of MAT because it has proven effective for HIV and hepatitis C prevention, as well as reducing illicit opioid use and deaths due to overdose, improving uptake and adherence to antiretroviral treatment for HIV-positive people who use drugs, and is cost-effective to society.[81]

The most widely used medications for opioid dependence are methadone and buprenorphine. Methadone is a synthetic opioid used to treat long-term opioid dependence and can also be used for chronic pain. Methadone typically is dispensed to patients onsite at clinics operating under strict federal licensing requirements. Methadone clinics have operated in the United States for more than three decades and there are nearly 2000 facilities in the United States.[82] Buprenorphine is a more recently developed medication that is a partial opioid agonist/blocker that is used for pain, for detoxification purposes, and in combination with naloxone for longer-term maintenance therapy. Both are controlled substances regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, but buprenorphine can be prescribed directly to patients, thus eliminating the need for daily visits to a specialty clinic and avoiding the stigma that can attach to these facilities.[83]

Despite an ever-increasing body of evidence supporting its efficacy, medication-assisted therapy remains severely underutilized in the United States.[84] Lack of training for medical professionals, abstinence-driven approaches and misinformation regarding MAT act as barriers to more widespread implementation, and in the US today, fewer than 1 in 4 individuals diagnosed with opioid use disorder is receiving this form of treatment.[85] Recent studies indicate that inconsistent and complex state Medicaid reimbursement regulations as well as requirements for physician involvement and training also keep many community-based organizations and non-medical treatment facilities from using MAT.[86] Security concerns, primarily diversion of medications to non-patients, have been found to largely preclude MAT adoption in US prisons and jails, though MAT is widely used in European and other international correctional facilities.[87] Drug treatment courts, designed as alternatives to jails for people charged with non-violent drug offenses, often fail to provide medication-assisted therapy as a treatment option.[88]

Perhaps the leading argument against medication-assisted therapy is that patients are simply “substituting one drug for another.” The US National Institute on Drug Abuse has addressed this argument as part of its effort to expand utilization of methadone and buprenorphine:

Because methadone and buprenorphine are themselves opioids, some people view these treatments for opioid dependence as just substitutions of one addictive drug for another. But taking these medications as prescribed allows patients to hold jobs, avoid street crime and violence, and reduce their exposure to HIV by stopping or decreasing injection drug use and drug-related high risk sexual behavior. Patients stabilized on these medications can also engage more readily in counseling and other behavioral interventions essential to recovery.[89]

Medication-assisted therapy is also underutilized at the Veterans Health Administration, where 500,000 of its total 6.4 million patients have been diagnosed with substance use disorders. Of these, an estimated 52,000 veterans have been diagnosed with opioid use disorder. The VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend methadone, buprenorphine and other pharmacotherapies as first-line treatments for substance use disorders.[90] However, in 2010, only 38 percent of the VHA hospitals offered methadone and buprenorphine in specialized licensed clinics, either at VHA hospitals or in community clinics under contract with the VHA. Buprenorphine was more readily available at 118 facilities within the VHA system.[91] Recognizing that limited availability in clinical settings left many veterans without access to MAT, the VHA took steps to promote availability of buprenorphine in less formal settings including mental health and primary care settings in an effort to expand access to MAT to new patients nationwide. This effort has produced results. Currently, all but 9 of 151 VHA facilities provide some level of buprenorphine availability, either onsite or through referrals to community providers.[92]

Buprenorphine treatment is expanding particularly among younger veterans, with Iraq and Afghanistan veterans more likely to be treated with MAT than their older counterparts, and more likely to be treated with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. Efforts to increase buprenorphine availability have enabled the VHA to currently treat 27 percent of veterans with opioid disorders with some form of MAT.[93] However, 38,000 patients still lack access to what both the US National Institute on Drug Abuse and the World Health Organization consider an essential component in treatment of opioid dependence.[94] The VHA acknowledges that “MAT is insufficiently available to veterans with opioid use disorders at some facilities.”[95]

The level of MAT should be understood within a context of growing demand for MAT services: the percentage of patients with opioid disorders at the VHA increased 45 percent between October 2003 and September 2010. During this period the VHA has managed to maintain the percentage of patients treated with MAT at 30 percent rather than sliding backwards, a result that would not have been possible without the concerted effort to expand access to buprenorphine.[96] The VHA study concludes by highlighting the importance of continued implementation of buprenorphine as a treatment modality preferred by a growing population of opioid-dependent veterans who “seek treatment in less stigmatizing contexts (e.g. office-based care).”[97]

Many of the barriers faced by the VHA in expanding access to MAT are similar to those encountered in the wider community. In order to dispense methadone, VHA clinics must have sufficient numbers of patients as well as the required infrastructure to meet strict federal regulations. Hospitals in large cities can accomplish this but coverage is frequently poor in rural areas, a problem that has been documented in the non-veteran population.[98] Buprenorphine is easier to access but some doctors, both at the VHA and in the community, are reluctant to undergo the eight-hour training required for permission to prescribe the medication if they are not addiction specialists. Others are concerned about diversion of the drug by their patients.[99] In addition, patients can be resistant to medication-assisted therapies; ambivalent or negative attitudes of opioid-dependent individuals toward methadone in particular are well documented, and include patients at the VHA.[100]

Despite these obstacles, VHA officials told Human Rights Watch that they remain committed to MAT and are taking steps to expand access. Specifically, internal pharmacy policies for buprenorphine prescription have been clarified to promote increased participation by non-addiction specialists and promote its integration into the primary care setting.[101] In California VHA hospitals, MAT (including medications for alcohol and tobacco dependence) specialists regularly consult with primary care doctors and nurses to answer questions, provide feedback and serve as resources for implementing this model of treatment. Video and telemedicine formats have been successfully implemented in Montana and will soon be extended to New England VHA facilities to assist rural veterans in receiving MAT prescriptions and consultations.[102] The VHA should maintain and intensify these efforts, as increasing numbers of veterans are in urgent need of the highly effective treatment provided by MAT.

As Timothy, a 65-year-old Vietnam veteran told Human Rights Watch, “Before I was on methadone I was nothing more than the walking dead. Being on methadone gave me my life back.”[103]

“Housing First” Programs for Homeless Veterans

I’d been homeless for years before this program found me. If I didn’t have this apartment [through HUD-VASH], I’d be living in the streets or in the subway. —Gary, 29, Iraq veteran, New York City[104]

Eric Shinseki, former Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs, has said that even one homeless veteran is “a national tragedy.”[105] In January 2013 the US Department of Housing and Development (HUD), estimated that 57,849 veterans were homeless for at least one night that month.[106] While this estimate provides a sense of the scale of homelessness, it also underestimates the crisis of homelessness and unstable housing that exists. The estimate excludes cities that fail to report and does not include those who are unstably or temporarily housed. By contrast, the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans estimates that 400,000 veterans experience homelessness at some point each year.[107] Most homeless veterans are not newly returned from the military; more than half of homeless veterans are over age 55, veterans of military service during and before the Vietnam war.[108] However, members of the military returning from Iraq and Afghanistan are becoming homeless at a higher rate than veterans from other wars, and female veterans are the fastest-growing segment of the homeless population in the US.[109]

Mental health disorders, including PTSD, TBI and substance use disorders, are strongest predictors of homelessness among all veterans, including those returning from Iraq and Afghanistan.[110] The VA has found that female veterans are “at much higher risk of homelessness” than male counterparts due to both physical and mental health impairments including Military Sexual Trauma (MST).[111] Homelessness has been linked to risk of suicide among veterans.[112]

With a declaration in 2009 that “no one who has served this nation should ever be living on the streets,” the Obama administration launched an initiative to end veteran homelessness by 2015. The government’s “Five Year Plan to End Veteran Homelessness” established a multi-agency effort that sought to increase resources, coordinate services, and to integrate mental health and medical care with housing and homelessness prevention programs. Working closely with the US Intra-agency Council on Homelessness, the plan calls for partnerships with community and non-governmental organizations, faith-based groups, and tribal councils to ensure that “no veteran falls through the cracks” and there is “no wrong door” for veterans to enter in an attempt to receive services. The plan includes a National Call Center hotline and a criminal justice component that recognizes that among the hundreds of thousands of incarcerated veterans, many become homeless upon re-entry to the community.[113]

Congress responded to the Five Year Plan with nearly a billion dollars in funding support for the VA’s programs to end veteran homelessness and has sustained funding for these programs each fiscal year since 2009. Congress also increased funding for medical care for homeless veterans in response to the initiative and these targeted programs now receive approximately 3 billion dollars per year. Federal investments appear to be producing results, as the number of homeless veterans has declined 24 percent since 2010.[114]

Buoyed by tangible impact, the President’s FY2015 budget seeks a 6.5 percent increase in funding for the Department of Veterans Affairs that includes a 1.6 billion dollar request for VA homeless programs.[115] Congress has thus far responded with bipartisan support for the Five-Year Plan. However, with returning veterans at continued risk of homelessness, maintaining federal funding for veterans’ housing initiatives remains vitally important.[116]

A key element of the Five-Year Plan is the conversion of transitional and shelter-based housing to permanent housing solutions. The primary vehicle for this conversion is the US Housing and Urban Development-Veteran Affairs Supported Housing (HUD-VASH), a program that combines “Section 8” housing vouchers from HUD with intensive case management services provided by the VHA.[117] Since 2008, approximately 57,000 veterans have received HUD-VASH housing vouchers.[118] To enter the program, veterans must be eligible for VHA services based on their discharge status, meaning they cannot have been dishonorably discharged.[119] In addition, HUD requires veterans to fall within specified income limits, possess a birth certificate, military discharge papers and other documentation. Notably, HUD waived its long-standing ban on tenants with felony histories specifically (and only) for the HUD-VASH program but sex offenders continue to be ineligible.[120]

The HUD-VASH program was intended to target the most vulnerable veterans, the chronically homeless who are likely to have acute physical and mental health conditions. However when it began, the program utilized a “housing readiness” model that moved a veteran gradually from homelessness to a shelter placement to transitional housing toward the final achievement of permanent housing.

This “traditional HUD-VASH” model assumes that transitional housing provides the opportunity for programming aimed to help people become “housing ready,” primarily by achieving sobriety and abstinence from drugs and alcohol. But substance use disorder among homeless veterans has been estimated to be as high as 70 percent, reflecting similar estimates for drug and alcohol dependence among the general adult homeless population.[121] The VA found that under this model, the HUD-VASH program was serving a low percentage of chronically homeless veterans and taking a long time- 6 months or more- to achieve a placement into permanent housing. In 2010, the Veterans Administration piloted a “Housing First” model for HUD-VASH.[122]

Housing First is a model for housing chronically homeless people with mental health conditions that provides permanent housing as a first step and then surrounds the individual with a range of supportive and therapeutic services. The Housing First model has developed a strong evidence base for both its ability to end the cycle of chronic homelessness for those with acute mental health conditions and its cost-effectiveness in reduced public health and emergency services for this population.[123]

According to Sam Tsemberis of Pathways to Housing, the organization credited with originating the Housing First model in the US:

Some people think that when you give housing away you are enabling people rather than helping them get better. Our experience has been that the offer of housing first, then treatment, actually has more effective results in reducing addiction and mental health symptoms, than trying to do it the other way.[124]

The initial pilot for a Housing First approach for HUD-VASH recipients in Washington, DC produced promising results. Using a Housing First model, the VA was able to target more vulnerable, chronically homeless veterans and place them more rapidly into permanent housing. After one year, 98 percent of these veterans maintained this housing, and emergency room and inpatient mental health usage dropped significantly.[125]

In 2012, the VA decided to expand the Housing First model to 14 additional sites throughout the US and conduct a thorough evaluation and analysis of the results. Crucial to this effort was the VA’s National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans, a research group created in conjunction with the Five Year Plan to identify, develop and promote evidence-based and best practices for the initiative to end veteran homelessness. This commitment to data and science-driven solutions enabled the VA to launch a comprehensive three year study of the expanded demonstration project using the Housing First model. The VA also requested technical assistance for the project from Pathways to Housing, establishing a productive partnership with the acknowledged experts in the field.[126]

The results from the nationwide demonstration project are incomplete, but interim results were presented at a 2014 Housing First conference. The Housing First model reached 948 veterans in 15 cities, 94 percent of whom were chronically homeless prior to entering the program. Of these veterans, 87 percent are still housed, despite high levels of mental health diagnosis (87 percent) and substance use (80 percent). VHA emergency room use dropped 27 percent among this population, and use of VHA inpatient mental health services was reduced by 33 percent. Overall, these veterans spent 7,400 fewer days as inpatients in a VHA facility, a 71 percent reduction that lowered VHA healthcare costs dramatically.[127]

The Housing First model is now official policy for the entire HUD-VASH program and will be utilized in all of the program’s approximately 100 sites nationwide.[128] In addition, veterans in Housing First HUD-VASH programs may be some of the earliest recipients of naloxone kits as the program expands.[129] Outreach efforts to women veterans are critical as female veterans are the fastest-growing population among homeless persons in the US.[130]

Female veterans comprise 10 percent of veterans nationwide, and 8 percent of HUD-VASH vouchers went to women veterans. But the program’s effectiveness in reaching homeless female veterans remains unclear due to a lack of information. The US General Accounting Office (GAO) recently found that women veterans appear to wait longer than their male counterparts for HUD-VASH housing, but that lack of data hindered comprehensive evaluation of women veterans and homelessness.[131] According to the report from the US General Accounting Office:

Absent more complete data, VA does not have the information needed to plan services effectively, allocate grants to providers, and track progress toward its overall goal of ending veteran homelessness by 2015. According to knowledgeable HUD and VA officials we spoke with, collecting data specific to homeless women veterans would incur minimal burden and cost.[132]

Veterans receiving HUD-VASH vouchers told Human Rights Watch of the enormous impact the Housing First model had made to their lives.

Before I found this program I lived everywhere and nowhere- moving around constantly, never had my own place. It was stressful. I was depressed. I had goals, but there was no way to get there.—Alan, 57, Vietnam veteran, San Francisco[133]

I was homeless for a year and a half before I found this program. Honestly, I’d be screwed if I didn’t have this housing. I’d probably be dead. Now I’m in treatment and doing okay. —Evan, 28, Iraq veteran, New York City[134]

|

Women Veterans Women now represent 20 percent of new military recruits and approximately 15 percent of current US armed forces. More than 100,000 female members of the military have returned from deployment in Iraq and Afghanistan.[135] Like their male counterparts, many are reporting symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. But for female veterans, the primary cause of PTSD is not combat related. Rather, 1 in 5 female veterans and 1 in 100 male veterans report an experience of military sexual trauma (MST), defined by the Veterans Administration as sexual assault or severe threatening sexual harassment.[136] In 2013, more than 5,000 active duty members of the military, both male and female, reported having been sexually assaulted, a 45 percent increase over the previous year.[137] Some of the increase can be attributed to greater willingness to report assaults, but the Department of Defense acknowledges that most sexual assaults in the military still go unreported.[138] Military sexual trauma is considered a stressor and not a diagnosis, but it is strongly and persistently associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Even in the absence of a PTSD diagnosis, military sexual trauma is linked to anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders. Veterans reporting military sexual trauma experience more physical health problems and more problems adjusting to civilian life, including high rates of unemployment.[139] There is also a strong correlation of MST with homelessness among female veterans; 87 percent of homeless female vets using VHA services have received a diagnosis of MST.[140] Military sexual trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder have been correlated with high risks of both suicide and drug overdose among women veterans. Female veterans are 3 times more likely than their civilian counterparts to commit suicide.[141] Homeless women veterans are at particularly high risk of taking their own lives, committing suicide at a higher rate than homeless male veterans. [142] Research currently underway by the National Development and Research Institutes in New York City suggests the need for targeted and gender-specific interventions, both within the VA and within community settings, for female veterans who may be at high risk of drug overdose. Of 40 female veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan surveyed, 30 percent reported PTSD and 20 percent reported an unwanted sexual encounter during their military service. Half of the female veterans surveyed were unemployed. Thirty five percent said they were taking prescription opioids for pain since separation from the military and 6 had experienced a non-fatal overdose. The study includes a narrative interview with a 29-year-old veteran of the Iraq war who described the treacherous link between alcohol, drugs and MST: After I was raped, I didn’t report it and I was sort of…I didn’t care. I slacked lots. I got in some trouble. I started using lots of drugs, anything, alcohol to numb or feel better.[143] —Keisha Susan, a 33-year-old Iraq veteran, said many women veterans have PTSD and the alcohol and drugs are used as “coping skills.” Susan told Human Rights Watch about her lieutenant in the Air Force, a 40-year-old veteran who got into drugs when she came out of the military. She was my supervisor but also my friend, and she was very dynamic-- the last person in the world I would think would have problems when she came home. She died of a drug overdose, or suicide, I don’t really know. She left two little kids. To this day I wish I could have helped her.[144] Though nearly half of younger women veterans are receiving care at VHA facilities, women veterans overall are not substantially engaged with the VHA health care system. Of an estimated 1.5 million female veterans in the US, only 15 percent utilize VHA health care compared to 22 percent of male veterans. [145] Lack of awareness of veterans’ benefits, including health care, is commonly cited as a serious problem for female veterans. This issue is the focus of several current initiatives at the Department of Veterans Affairs, including a long-term study on the causes and possible remedies for underutilization of health services by women veterans. [146] A recent study conducted by the Rand Corporation that surveyed veterans not enrolled in the VHA found that the most common barrier was “lack of information about what services were available, how to access them, and how helpful the services were.” [147] The Service Women’s Action Network reports that many female veterans who do seek services at the VHA have negative experiences ranging from an “unwelcome” atmosphere, absence of gender-specific services to re-traumatization and increased symptoms of PTSD and depression. [148] Some women veterans reported to Human Rights Watch that drug treatment programs at the VHA are not inclusive or relevant to their needs. At my VA they offered me only a group with all male Vietnam vets. That just does not work for me. —Theresa, 44, Gulf War veteran, Davis, California[149] |

Drug Dependence and Human Rights

All persons have the right to the means to protect their health and well-being, and governments must protect these rights without discrimination. As essential components of human dignity, the right to health information, prevention and care, as well as housing and necessary social services are fundamental principles are enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[150] Everyone, including people with mental health conditions, is entitled to medication necessary to control and alleviate pain.[151] Similarly, patients are entitled to chronic pain management even if they have a history of illicit drug use or dependence. If patients develop dependence on pain medications, the answer is not to deny access but to provide treatment in accordance with recognized principles, proven standards and established best practices.[152] Evidence-based approaches to drug dependence, including overdose prevention and access to methadone and buprenorphine, are key elements of both the right to health and the right to life.

Numerous international instruments address the meaning and scope of the right to health, and international bodies have specifically recognized harm reduction practices as a vital element of the right to protect one’s health. The United States has signed but not yet ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the key treaty that protects the right to health, and is obligated to act in ways that do not undermine its purpose and effect.[153] Governments are obligated to ensure, at a minimum, a range of harm reduction interventions including overdose prevention, opioid substitution therapy and harm reduction for people who use drugs.[154] The United Nations special rapporteurs on the right to health and the right to be free from torture have stated:

Harm reduction is essential to the progressive realization of the right to the highest attainable standard of health for people who are using drugs and, indeed, for communities affected by drug use.[155]

Naloxone, methadone and buprenorphine are all on the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines.[156] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the body charged with monitoring compliance with ICESCR, has identified access to essential medicines as key to realization of the right to health.[157] Access to naloxone, a drug that can reverse a fatal overdose, is also a component of the most fundamental of human rights, the right to life. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which the United States is a party, guarantees to every person the right to life, a right that is implicated in governmental response to what Attorney General Eric Holder has called “the urgent public health crisis” of drug overdose.[158]

Housing is also a fundamental human right. As stated by the special rapporteur on adequate housing:

The right to adequate housing is the right of every woman, man, youth and child to gain and sustain a secure home and community in which to live in peace and dignity.[159]

Housing is also a key element of the realization of the right to health, for without shelter most prevention and treatment services remain limited or out of reach.[160] In addition, drug dependence is a medical condition that for some persons can be a disability, and as such it is protected by both the right to health and the right to live free from discrimination. International human rights law prohibits discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability and requires states to ensure equal access to housing for people with disabilities.[161] The International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), a treaty signed by the United States, specifically mandates access on an equal basis to “public housing programmes.”[162] The “traditional HUD-VASH” program excluding veterans with drug dependence from permanent housing until they achieved sobriety was not only ineffective but incompatible with international human rights law.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Megan McLemore, senior researcher in the Health and Human Rights Division. The report was reviewed at Human Rights Watch by Joseph Amon, director of the Health and Human Rights Division, Diederik Lohman, senior researcher in the Health and Human Rights Division, Meghan Rhoad, researcher in the Women’s Rights Division, Sara Darehshori, senior counsel in the US Program, Dinah PoKempner, general counsel, and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director in the Program Office. Production assistance was provided by Jennifer Pierre, associate, Kathy Mills, publications specialist, Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, and José Martinez, senior coordinator.

Human Rights Watch gratefully acknowledges the invaluable assistance of Alexander Bennett at the National Development and Research Institutes, Dr. Sharon Stancliff at the Harm Reduction Coalition, Daniel Robelo at the Drug Policy Alliance, Juan Cortez at the New York Harm Reduction Educators, and Jazmin Breaux at West Bay Housing.

Most of all, Human Rights Watch thanks the veterans who shared their experiences for this report.

[1] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Theresa A., Davis, California, March 3, 2014. Pseudonyms are used in this paper for veterans interviewed in order to protect confidentiality.

[2] US Department of Defense, “Casualty Status Report,” dated April 9, 2014, http://www.defense.gov/news/casualty.pdf (accessed April 10, 2014).

[3] Terri Tanelian and Lisa Jaycox, Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery (Santa Monica: Rand, 2008).

[4] Congressional Research Service, “A Guide to US Military Casualty Statistics: Operation New Dawn, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation Enduring Freedom,” February 19, 2014, http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS22452.pdf (accessed April 10, 2014).

[5] Terri Tanelian and Lisa Jaycox, Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Post-traumatic stress disorder is a type of anxiety disorder that can develop after experiencing or witnessing extreme emotional trauma that involved the threat of injury or death. US National Institute of Health, “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” May 16, 2014, http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000925.htm (accessed May 27, 2014); Traumatic Brain Injury occurs when an external mechanical force causes brain dysfunction. Mayo Clinic, “Traumatic Brain Injury Definition,” undated, http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/traumatic-brain-injury/basics/definition/con-20029302 (accessed May 27, 2014).

[6] National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Drug Facts: Substance Abuse in the Military,” March 2013, http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/substance-abuse-in-military (accessed April 10, 2014); Tara Macey et al, “Patterns and Correlates of Prescription Opioid Use in OEF/OIF Veterans with Non-Cancer Pain,” Pain Medication 12 (2011): 1502-7, accessed April 10, 2014, doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01226.x.

[7] For the purposes of this report the term “dependence” will be used as a general reference to describe a condition that may or may not have been diagnosed as an opioid use disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (DSM-V), published by the American Psychiatric Association.

[8] Elizabeth Oliva et al, “Trends in Opioid Agonist Therapy in the Veterans Health Administration: Is Supply Keeping Up with Demand?” American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Use, 39 (2013): 103-107, accessed April 10, 2014, doi:10.3109/00952990.2012.741167.

[9]US Department of Veterans Affairs, Mental Health Services Suicide Prevention Program, Suicide Data Report 2012, Washington DC 2012.

[10]US Department of Veterans Affairs, “Homeless Veteran Treatment Programs,” December 9, 2013, http://www.nynj.va.gov/homeless.asp (accessed April 28, 2014).

[11] US Department of Veterans Affairs, “The Veterans Health Administration,” June 10, 2014, http://www.va.gov/health/aboutVHA.asp (accessed April 29, 2014). Nine Million veterans are enrolled in VHA health care plans, but nearly 6 million utilize services in a given year.

[12] US Department of Veterans Affairs, “Health Benefits, Veterans Eligibility,” April 15, 2014, http://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/apply/veterans.asp (accessed April 29, 2014).

[13] Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Urban Institute, “Uninsured Veterans and Family Members: Who Are They and Where do They Live?: Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues,” May 2012, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412577-Uninsured-Veterans-and-Family-Members.pdf (accessed April 29, 2014).The 1.3 million figure excludes elderly veterans who may have Medicare or other health coverage.

[14] Character of Discharge, 38 CFR 3.12; Certain Bars to Benefit, 38 USC 5303; US Department of Veterans Affairs, “Health Benefits, Veterans Eligibility,” http://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/apply/veterans.asp; US Department of Veterans Affairs, “Other Than Honorable Discharges: Impact on Eligibility for VA Health Benefits,” December 2011, http://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/assets/documents/publications/IB10-448.pdf (accessed April 29, 2014).

[15] Urban Justice Center Veteran Advocacy Project, “VA Benefits and Discharge Status, Slide Presentation.” On file with Human Rights Watch.

[16] National Public Radio, “Path to Reclaiming Identity Steep for Vets with Bad Paper,” December 11, 2013, http://www.npr.org/2013/12/11/249962933/path-to-reclaiming-identity-steep-for-vets-with-bad-paper (accessed April 29, 2014); Rebecca Izzo, “In Need of Correction: How the Army Board for Correction of Military Records is Failing Veterans with PTSD,” Yale Law Journal, 123 (2014): 1118-1625, accessed April 10, 2014, http://yalelawjournal.org/article/in-need-of-correction-how-the-army-board-for-correction-of-military-records-is-failing-veterans-with-ptsd.

[17] Veterans Health Administration, “Analysis of VA Health Care Utilization Among Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation New Dawn (OND) Veterans, 2002-2012”, 2012, http://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/epidemiology/healthcare-utilization-report-fy2012-qtr1.pdf (accessed April 10,2014); Department of Veterans Affairs, “Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain,” May 2010, http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/ (accessed April 14, 2014).

[18] Ibid; For detailed data regarding numbers of veterans diagnosed with specific physical and mental conditions see, Veterans Health Administration, “Analysis of VA Health Care Utilization Among Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation New Dawn (OND) Veterans, 2001-2013,” March 2014, http://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/epidemiology/healthcare-utilization-report-fy2014-qtr1.pdf (accessed June 9, 2014).

[19] US National Institute of Health, “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000925.htm. Traumatic Brain Injury occurs when an external mechanical force causes brain dysfunction. Mayo Clinic, “Traumatic Brain Injury Definition,” http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/traumatic-brain-injury/basics/definition/con-20029302.

[20] Mayo Clinic, “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder,” undated, http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/basics/symptoms/con-20022540 (accessed April 10, 2014).

[21] US National Institute of Health, “PTSD: A Growing Epidemic,” undated, http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/magazine/issues/winter09/articles/winter09pg10-14.html (accessed April 10, 2014.)

[22] US Department of Veterans Affairs, “PTSD and the Military,” undated, http://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/PTSD-overview/basics/how-common-is-ptsd.asp (accessed May 10, 2014).

[23] American Psychiatric Association, “Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders,” 2013, http://www.dsm5.org/Documents/Substance%20Use%20Disorder%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf (accessed May 27, 2014); US Department of Veterans Affairs, “Mental Health: Substance Use,” April 2, 2014, http://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/substanceabuse.asp (accessed May 27, 2014).

[24] Suzy Gulliver and Laurie Steffen, “Towards Integrated Treatments for PTSD and Substance Use Disorders,” PTSD Research Quarterly, 21 (2010); Karen Seal et al, “Substance Use Disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans in VA Healthcare 2001-2010: Implications for Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 116 (2011): 93-101, accessed April 14, 2014, doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.027. American Psychiatric Association, “Using Medication-Assisted Treatment with Veterans for Opioid, Alcohol and Tobacco Use Disorders,” February 11, 2014, Webinar presentation by Dr. Andrew Saxon, Director, Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education, Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/professional-interests/addiction-psychiatry/using-medication-assisted-treatment-with-veterans-for-opioid-alcohol-and-tobacco-use-disorders (accessed April 11,2014); Karen Seal, et al, “Association of Mental Health Disorders With Prescription Opioids and High-Risk Opioid Use in US Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan,” Journal of the American Medical Association, 307 (2012): 940-947, accessed April 14, 2014, doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234.

[25] US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Co-Occurring Disorders in Veterans and Military Service Members,” undated, http://samhsa.gov/co-occurring/topics/military/index.aspx (accessed April 10, 2014.)

[26] Phipson Wu et al, “Opioid Use in Young Veterans,” Journal of Opioid Management, 6(2010), p. 133-9.

[27] Mark Sullivan et al, “National Analysis of Opioid Use Among Veterans,” (Presented at the American Academy of Pain Medicine Annual Conference 2014). On file with Human Rights Watch.

[28] US Army, “Health Promotion, Risk Reduction and Suicide Prevention Report,” July 29, 2010, http://csf2.army.mil/downloads/HP-RR-SPReport2010.pdf (accessed April 14, 2014).

[29]Macey et al, “Patterns and Correlates of Prescription Opioid Use in OEF/OIF Veterans with Non-Cancer Pain,” p.1502-7. The study excluded cancer patients and included only patients with at least three elevated pain screening scores in a 12 month period.

[30] National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Drug Facts: Substance Abuse in the Military,” http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/substance-abuse-in-military.

[31] Karen Seal et al, “Association of Mental Health Disorders with Prescription Opioids and High-Risk Opioid Use in US Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan,” p. 940-947.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Amy Bohnert et al, “Accidental Poisoning Mortality among Patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health System,” Medical Care, 49 (2011): 393-396, accessed April 10, 2014, doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202aa27.

[34] US Centers for Disease Control, “Public Health Grand Rounds: Drug Overdoses, an American Epidemic,” May 21, 2014, http://www.cdc.gov/about/grand-rounds/archives/2011/01-February.htm (accessed April 14, 2014).

[35] US Veterans Health Administration, “Pain Management,” October 28, 2009, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/799962-pain_management.html (accessed April 29, 2014); Department of Veterans Affairs, “Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain,” http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/. Some experts have expressed concern that the revised FDA regulations are too restrictive and may reduce access to pain medication for those whose need for pain relief is legitimate and are at low risk of misuse. See, e.g. David Wild, “Efforts Increase to Curb Rise of Illegitimate Pain Clinics in Florida,” November 2010, Anesthesiology News, http://www.anesthesiologynews.com/ViewArticle.aspx?d_id=2&a_id=16125 (accessed April 14, 2014); Maia Szalavitz, “FDA Action on Vicadin May Mean More Pain, Not Less Addiction and Overdose,” January 31,2013,Time, http://healthland.time.com/2013/01/31/fda-action-on-vicodin-may-mean-more-pain-not-less-addiction-or-overdose/ (accessed April 14, 2014).

[36] See, e.g., Center for Investigative Reporting, “VA Opiate Overload Feeds Veterans’ Addictions, Overdose Deaths,” September 28, 2013, http://cironline.org/reports/vas-opiate-overload-feeds-veterans-addictions-overdose-deaths-5261 (accessed April 29, 2014); Alex Bennett et al, “Opioid and Other Substance Misuse, Overdose Risk and the Potential for Prevention Among a Sample of OEF/OIF Veterans in New York City,” Substance Use and Misuse, 48 (2013): 894-907, accessed April 14, 2014, doi:10.3109/10826084.2013.796991; Ted Hart, “Veterans Vulnerable to Drug Overdoses,” October 10, 2013, http://www.nbc4i.com/story/22210001/veterans-vulnerable-to-drug-overdoses (accessed April 29, 2014).

[37] US Department of Veteran Affairs, “VA Initiative Shows Early Promise in Reducing Use of Opioids for Chronic Pain,” February 25, 2014, http://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=2529 (accessed April 10, 2014).

[38] Pradip Muhuri et al, “Associations of Non-Medical Pain reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use in the United States,” August 2013, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Data Review, http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DataReview/DR006/nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-2013.pdf (accessed April 14, 2014).

[39] See, e.g. Theodore Cicero et al, “Effect of Abuse-Deterrent Formulation of OxyContin,” New England Journal of Medicine, 367(2012):187-189, accessed April 10, 2014, doi:10.1056/NEJMc1204141; Benedict Carey, “Prescription Painkillers Seen as Gateway to Heroin,” New York Times, February 10, 2014.

[40] Kim Krisberg, “Fatal Heroin Overdoses on the Increase as Use Skyrockets,” undated,The Nation’s Health,http://thenationshealth.aphapublications.org/content/44/4/1.1.full (accessed April 14, 2014).

[41] US Department of Veterans Affairs, Mental Health Services Suicide Prevention Program, Suicide Data Report 2012, Washington DC 2012; Robert Burns, “2012 Military Suicides Hit a Record High of 349,” Associated Press, January 14, 2013.

[42] US Department of Veterans Affairs, Mental Health Services Suicide Prevention Program, Suicide Data Report 2012, Washington DC 2012.

[43] VA National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans, “Housing Placement and Suicide Attempts Among Homeless Veterans,” 2012, http://www.dcoe.mil/content/Navigation/Documents/SPC2012/2012SPC-Hill-Housing_Placement.pdf (accessed April 28, 2014).

[44] US Army, “Army 2020: Generating Health and Discipline in the Force Ahead of the Strategic Reset,” 2012, http://usarmy.vo.llnwd.net/e2/c/downloads/232541.pdf (accessed April 14, 2014).

[45] US Army, “Health Promotion, Risk Reduction and Suicide Prevention Report,” http://csf2.army.mil/downloads/HP-RR-SPReport2010.pdf.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Austin-American Statesman Investigative Team, “Uncounted Casualties: Home, But Not Safe,” September 29, 2012, http://www.statesman.com/news/news/prescription-drug-abuse-overdoses-haunt-veterans/nSPLW/ (accessed April 29, 2014).

[49] Institute of Medicine, “Returning Home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Assessment of Readjustment Needs of Veterans, Service Members and Their Families,” March 2013, http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2013/Returning-Home-Iraq-Afghanistan/Returning-Home-Iraq-Afghanistan-RB.pdf (accessed April 14, 2014); The White House, “The Employment Situation in October,” 2013, http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2013/11/08/employment-situation-october (accessed April 14, 2014); US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Situation of Veterans Summary,” March 2014, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/vet.nr0.htm (accessed April 14, 2014).

[50] National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, “Homeless Veteran Fact Sheet,” undated, http://www.nchv.org/images/uploads/HomelessVeterans_factsheet.pdf (accessed April 14, 2014) ; US Department of Housing and Urban Development, “2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report,” undated, https://www.onecpd.info/resources/documents/ahar-2013-part1.pdf (accessed April 28, 2014).

[51] National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, Homeless Veteran Fact Sheet, undated, http://www.nchv.org/images/uploads/HomelessVeterans_factsheet.pdf (accessed April 14, 2014).

[52] Alex Bennett et al, “Opioid and Other Substance Misuse, Overdose Risk and the Potential for Prevention Among a Sample of OEF/OIF Veterans in New York City,” p.894-907.

[53] Bennett, p. 900.

[54] Bennett, p. 907.

[55] Human Rights Watch interview with James D., New York City, January 29, 2014.

[56] Human Rights Watch interview with Donald A., New York City, January 29, 2014.

[57] Human Rights Watch interview with Brian S., New York City, January 29, 2014.

[58] Human Rights Watch interview with Michael H., New York City, March 7, 2014.

[59] Human Rights Watch interview with Michael H., New York City, March 7, 2014.

[60] Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Sharon Stancliff, Medical Director, Harm Reduction Coalition, New York City, June 3, 2014.

[61] Daniel Kim et al, “Expanded Access to Naloxone: Options for Critical Response to the Epidemic of Opioid Overdose Mortality,” American Journal of Public Health, 99(2009): 402-407, accessed April 14, 2014, doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.136937.

[62] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, “Community-Based Opioid Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone- United States 2010,” February 17, 2012; Bridget Keuhn, “Back from the Brink: Groups Urge Wide Use of Opioid Antidote to Avert Overdoses,” Journal of the American Medical Association, 311(2014): 560-561, accessed April 14, 2014, doi:10.1001/jama.2014.481; US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit,” http://store.samhsa.gov/product/opioid-overdose-prevention-toolkit/all-new-products/sma13-4742 (accessed April 29, 2014).

[63] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Eric Konicki, MD,Chief of Psychiatry, Louis Stokes Cleveland Veterans Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, April 2, 2014.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Elizabeth Oliva, PhD. Health Sciences Specialist at the Program Evaluation and Resource Center, Veterans Administration, Palo Alto, California, March 3, 2014.

[67] Human Rights Watch email communication with Elizabeth Oliva, PhD, Health Sciences Specialist at the Program Evaluation and Resource Center, Veterans Administration, June 5, 2014.

[68] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Elizabeth Oliva, Health Sciences Specialist at the Program Evaluation and Resource Center, Veterans Administration, Palo Alto, California, March 3, 2014; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dr. Andrew Saxon, Director, Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education, Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, February 20, 2014.

[69] Phillip Coffin and Stan Sullivan, “Cost-effectiveness of Distributing Naloxone to Heroin Users for Lay Overdose Reversal,” Annals of Internal Medicine, 158(2013): 1-9, accessed April 14, 2014, doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00003.

[70] Human Rights Watch email communication with Elizabeth Oliva, PhD, Health Sciences Specialist at the Program Evaluation and Resource Center, Veterans Administration, June 5, 2014.

[71] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, “Community-Based Opioid Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone- United States 2010,” February 17, 2012.

[72] Network for Public Health Law, “Legal Interventions to Reduce Overdose Mortality: Naloxone Access and Overdose Good Samaritan Laws,” undated, https://www.networkforphl.org/_asset/qz5pvn/network-naloxone-10-4.pdf (accessed June 5, 2014).

[73] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “Opioid Overdose Prevention and Management for Injection Drug Users,” 2012, http://www.unodc.org/documents/southasia/publications/sops/opioid-overdose-prevention-and-management-among-injecting-drug-users.pdf (accessed April 14, 2014).

[74] Ingrid Binswanger et al, “Return to Drug Use and Overdose After Release From Prison: A Qualitative Study of Risk and Protective Factors,” Addiction Science and Clinical Practice, 7 (2012): accessed April 14, 2014, doi:10.1186/1940-0640-7-3.