Uncontrolled Pain

Ukraine’s Obligation to Ensure Evidence-Based Palliative Care

Map of Ukraine

Glossary

Ambulatoria: An outpatient clinic that together with the feldshersko-akusherski punkt (FAP) is often the only source of healthcare available to patients in rural areas.

Analgesic: A medicine that reduces pain.

Central District Hospital: The main health facility and administrative center for the public healthcare system. Each of Ukraine’s 490 districts has one.

Chronic pain: Defined in this report as pain that occurs over weeks, months, or years rather than a few hours or days. Because of its duration, moderate to severe chronic pain should be treated with oral opioids rather than repeated injections, especially for people emaciated by diseases such as cancer and HIV/AIDS.

Controlled medicines: Medicines that contain controlled substances.

Controlled substances: Substances that are listed in one of the three international drug control conventions: the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961 as amended by the 1972 Protocol; the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971; and the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988.

Dependence: Defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) Expert Committee on Drug Dependence as a “cluster of physiological, behavioral and cognitive phenomena of variable intensity, in which the use of a psychoactive drug (or drugs) takes on a high priority. The necessary descriptive characteristics are preoccupation with a desire to obtain and take the drug and persistent drug-seeking behavior. Determinants and problematic consequences of drug dependence may be biological, psychological or social, and usually interact.”[1] Dependence is clearly established to be a disorder. For Dependence syndrome, WHO’s International classification of diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10), requires that three or more of the following six characteristic features have been experienced or exhibited:

- A strong desire or sense of compulsion to take the substance;

- Difficulty controlling the onset, termination, and levels of use of substance-taking behavior;

- Physiological withdrawal state when substance use has ceased or been reduced, as evidenced by: the characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; or use of the same (or a closely related) substance with the intention of relieving or avoiding withdrawal symptoms;

- Evidence of tolerance, such that increased doses of the psychoactive substance are required in order to achieve effects originally produced by lower doses;

- Progressive neglect of alternative pleasures or interests because of psychoactive substance use, increased amount of time necessary to obtain or take the substance or to recover from its effects;

- Persisting with substance use despite clear evidence of overtly harmful consequences, such as harm to the liver through excessive drinking, depressive mood states after periods of heavy substance use, or drug-related impairment of cognitive functioning; efforts should be made to determine that the user was actually, or could be expected to be, aware of the nature and extent of the harm.

The Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (ECDD) concluded “there were no substantial inconsistencies between the definitions of dependence by the ECDD and the definition of dependence syndrome by the ICD-10.”

Diversion: The movement of controlled drugs from licit to illicit distribution channels or to illicit use.

Essential medicines: Those medicines that are listed on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines or the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children. Both model lists present a list of minimum medicine needs for a basic healthcare system, listing the most efficacious, safe, and cost-effective medicines for priority conditions.

Feldshersko-akusherski punkt(FAP): A local health clinic that provides basic procedures, including prenatal care and first aid. These health centers are run by feldshers, physician assistants trained in vocational medical schools. They provide routine checkups, immunizations, emergency first-aid, and midwifery services. There are no physicians at these clinics.

Hospice: A specialist palliative care facility. In Ukraine, hospices are exclusively in-patient facilities.

Life-limiting illness: A broad range of conditions including cancer, HIV/AIDS, dementia, heart, renal, and liver disease, and permanent serious injury, in which painful or distressing symptoms occur; although there may also be periods of healthy activity, there is usually at least a possibility of premature death.

Misuse (of a controlled substance): Defined in this report as the non-medical and non-scientific use of substances controlled under the international drug control treaties or national law.

Morphine: A strong opioid medicine that is the cornerstone for treatment of moderate to severe cancer pain. The WHO considers morphine an essential medicine in its injectable, tablet, and oral solution formulations.

Narcotic drugs: A legal term that refers to all those substances listed in the Single Convention.

Opioid: The term means literally “opium-like substance.” It can be used in different contexts with different but overlapping meanings. In pharmacology, it refers to chemical substances that have similar pharmacological activity as morphine and codeine, i.e. analgesic properties. They can stem from the poppy plant, be synthetic, or even made by the body (endorphins).

Over-the-counter pain medicines: Non-opioid pain medicines suitable for mild pain, including paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen), aspirin, and ibuprofen.

Palliative care: Health care that aims to improve the quality of life of people facing life-limiting illness, through pain and symptom relief and psychosocial support for patients and their families. Palliative care can be delivered in parallel with curative treatment but its purpose is to care, not cure.

Psychosocial support: A broad range of services for patients and their families to address the social and psychological issues they face due to life-limiting illness. Psychologists, counselors, and social workers often provide these services.

Strong opioid analgesics: Pain medicines that contain strong opioids, such as morphine, methadone, fentanyl, and oxycodone and are used to treat moderate to severe pain.

Weak opioid analgesics: Pain medicines that are generally used to treat mild to moderate pain, including codeine, dihydrocodeine, and tramadol.

Prologue: The Story of Vlad Zhukovsky

Born in 1983, Vladislav (Vlad) was in many ways a young Ukrainian no different than many others. He lived with his mother and sister in a two-bedroom flat in a Soviet-style apartment park on the outskirts of Cherkassy in central Ukraine. He loved playing his guitar and taking walks along the River Dnepr. He faithfully attended church with a tight knit group of friends and had a knack for computers, a talent he hoped to turn into a career.

Vlad’s ordinary life abruptly ended in 2001 when he was a second-year student of computer technology. One day in class, he developed a headache that was so severe that, according to his mother, he fell down, crying in pain. “We gave him analgin [a commonly used pain medication] but nothing worked,” said Nadezhda (Nadya), Vlad’s mother. “He just grabbed his head and screamed.”[2] She called an ambulance to take Vlad to the hospital, where brain scans revealed a large medulloblastoma of the cerebellum, a malignant tumor.

A fierce battle with cancer ensued. Radiation initially forced the brain tumor into remission. But the cancer kept coming back. Over the next nine years, tumors formed in Vlad’s lower spine, again in his head, his chest, and eventually again his spine. With each new tumor, the periods of remission grew shorter and Vlad weaker.

Throughout this ordeal, Vlad and his mother fought a second battle: with pain. This battle, at least, should not have been a losing one. The World Health Organization (WHO) says that “[m]ost, if not all, pain due to cancer could be relieved if we implemented existing medical knowledge and treatments.”[3] But as Vlad learned, the way Ukraine’s healthcare system treats cancer pain has little in common with current medical knowledge.

In 2007 Vlad developed persistent, severe pain that over-the-counter pain medicines could no longer relieve. According to his mother, who devotedly took care of her son, the pain was so bad that he often screamed in agony, sometimes so loud that it disturbed their neighbors. She told Human Rights Watch: “Hearing his pain, how he struggled, how he howled, it was just impossible to be in the [same] room.” The pain deprived him of sleep, made him moody, disrupted normal interaction with family and friends, and—possibly worst of all for a young man who liked to be active—reduced him to passively lying in bed and staring at the ceiling. Indeed, the pain incapacitated Vlad more than his cancer.

While Vlad’s doctors did prescribe a strong pain medication to treat Vlad’s pain, they did so with inadequate regularity and insufficient doses to offer full relief. The WHO recommends that morphine or a pain medication of similar strength be given every four hours to ensure continuous relief and that “the ‘right’ dose is the dose that relieves the patient’s pain.”[4] Yet, Vlad’s doctors initially prescribed just three doses per day, leaving him without relief half of the time.

Nadya Zhukovski kisses her sleeping son Vlad before going to the local pharmacy for medical supplies. © Scott Anger & Bob Sacha for the Open Society Foundations.

One day, in June 2008, Vlad’s pain became so severe that he could no longer bear it and decided to jump from his hospital window. While his mother was pleading with nurses to give him more pain medications, Vlad climbed into the open window. Most of his body was already outside—his fall imminent—when his roommate, a retired police officer, noticed what was happening, grabbed him by the leg, and forced him back in. He later told his mother that he had wanted to fall “head down and be dead right away so it wouldn’t hurt anymore.” Vlad, who was very religious, was deeply troubled by his suicide attempt. He repeatedly told his mother afterwards that he worried that the pain might make him do something sinful that would prevent him from seeing her again in heaven.

No matter how obvious it was that Vlad’s pain was not under control, doctors met Nadya’s subsequent pleas for more pain medications with great reluctance, sometimes bordering on hostility. When she pleaded for a fourth dose, doctors at one hospital accused her of selling the medications on the street. A year later, as she tried to convince doctors at another hospital that her son needed a fifth dose, doctors claimed more of the medication would lead to an overdose and they would then face prosecution “like Michael Jackson’s doctor.”

Supported by his mother and a small, local nongovernmental palliative care organization called Face-to-Face, Vlad battled with the pain and the cancer. He tried to stay positive and enjoy those moments when he was not in pain. Even after the cancer invaded his spinal cord and paralyzed him from the waist down, his church friends would occasionally take him in a wheelchair to the River Dnepr for a short walk.

Vlad died in October 2010. A few months before his death, he said he hoped to be remembered as “an ordinary, happy person, as normal, sociable Vlad.”[5]

During this nine year ordeal, Vlad and his mother frequently spoke of the need for change in Ukraine’s healthcare system that caused him so much unnecessary suffering. Vlad did not want his agony to be in vain or suffered again by tens of thousands of Ukrainians battling cancer each year.

***

This report is dedicated to Vlad’s courage and memory, and to his mother Nadya.

Summary

Patients with life-limiting illnesses need curative treatment, but they also need palliative care, which aims to address pain and improve life quality diminished by debilitating symptoms such as shortness of breath, anxiety, and depression.[6]

Every year almost half a million people in Ukraine may require palliative care services to alleviate the symptoms of life-limiting illnesses.[7] These include circulatory system illnesses such as chronic heart disease (almost 489,000 deaths per year), cancer (100,000), respiratory illnesses (28,000), tuberculosis (10,000), neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (6,500), and HIV and AIDS (about 2,500).[8]

Relieving pain is a critical part of palliative care. About 80 percent of patients with advanced cancer develop moderate to severe pain, as do significant numbers of patients with HIV and other life-limiting illnesses. With existing medical knowledge physical pain can be successfully treated in most cases. But while these symptoms are treatable, limitations in Ukraine’s health policy, education, and drug availability; lack of cohesion, urgency, and coordination on the part of the government; unnecessarily onerous drug regulations; inadequate training and a dearth of exposure to palliative care services for Ukrainian healthcare providers mean the country’s public health system offers poor pain treatment and little support for families dealing with life-limiting illnesses.

The country has 9 hospices with a total of about 650 beds, which provide services to inpatients.[9] The government has also assigned palliative care beds in some other public hospitals, and the national cancer control plan envisions a total of 36 hospices by 2016, although it does not allocate a budget for this.[10] Despite this, most patients with life-limiting illnesses in Ukraine die at home; indeed, hospitals are not supposed to admit patients with cancer who are no longer receiving curative treatment. Yet there are no full-fledged home-based palliative care services.[11] Some nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) provide home-based care but cannot offer pain management with opioid analgesics, including morphine, which WHO guidelines for cancer pain emphasize, should be used to treat moderate to severe pain. Most AIDS centers do not offer palliative care services.[12] According to a 2011 International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) report, the amount of opioid analgesics Ukraine uses per year is “very inadequate.”[13]

In 2010 Human Rights Watch—together with the Institute of Legal Research and Strategies in Kharkiv and the Rivne and Kiev branches of the All-Ukrainian Network of People Living with HIV—researched the availability of pain treatment and palliative care in Ukraine. We found that Vlad’s unnecessary suffering was not an unfortunate anomaly. Rather, it was in many ways representative of the fate of patients who endure pain due to life-limiting diseases.

In dozens of interviews, patients, families, doctors, nurses, and government officials painted a picture of a healthcare system that systematically fails patients who are in severe pain because pain treatment is often inaccessible, best practices for palliative care are ignored, and anti-drug abuse regulations hamstring healthcare workers’ ability to deliver evidence-based care. Those healthcare workers who try to provide the most effective pain treatment possible must often operate, as one oncologist said, “on the edge of the law.”[14] These doctors and nurses ignore legal restrictions and provide patients with a take-home supply of strong pain medications or leave the day’s supply with patients to administer themselves. In doing so, these doctors and nurses expose themselves to administrative and criminal charges for putting patients’ well-being first.

The situation is particularly devastating in rural areas—home to about one-third of Ukraine’s population of 46 million—where strong opioid analgesics are often hard to access or simply unavailable.[15] Only central district hospitals have the necessary license to stock and dispense morphine and other strong opioid analgesics, according to doctors in rural districts who said requirements for obtaining such licenses are too onerous and costly for many smaller hospitals and health clinics.[16] As a result, people in rural towns and villages often live far from health centers with strong pain medications.

Distance might be surmountable if healthcare providers could give patients and their families a supply of strong opioid analgesics for at least a week or two. However, under Ukraine’s drug regulations healthcare workers must directly administer injectable strong opioid pain medications to patients, a requirement that is medically unnecessary. As oral morphine is unavailable in Ukraine, a nurse or other healthcare worker must travel to the patient’s home up to six times a day to administer pain medications (the WHO recommends that morphine is administered every four hours). This burden is too great for healthcare workers, leaving patients with severe pain in remote areas “doomed,” according to one nurse.[17]

Patients in urban areas face a different problem. Here, hospitals generally do have the license for strong opioid analgesics, but pain treatment is still often woefully inadequate, as healthcare workers routinely ignore the core principles for effective pain treatment that the World Health Organization has identified.[18] This leaves individuals with inadequate and inconsistent relief from excruciating pain.

There is no acceptable reason why Ukraine cannot deliver proper palliative care and pain management to patients with life-limiting illnesses. Although under-resourced, Ukraine has a healthcare system that is able to deliver effective treatment for various other health conditions.

Failure to address barriers to effective pain treatment identified in this report places Ukraine in violation of the right to health guaranteed by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and in possible violation of the prohibition on torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. It also ensures that Ukraine continues to remain out of step with its neighbors—including Belarus, Moldova, Russia, and Turkey–which have less restrictive drug regulations and with European countries that all (except for Armenia and Azerbaijan) have oral morphine available for patients.[19] Lack of action also means that Ukraine will continue to deviate fundamentally from World Health Organization recommendations in standard pain treatment practices, that healthcare workers will have to break the law to provide evidence-based care, and that patients will continue to suffer.

All medical students should receive basic instruction on palliative care and pain treatment. Those specializing in disciplines that frequently care for people with life-limiting illnesses should receive detailed instruction and exposure to clinical practice. Ukraine must urgently amend the restrictive and problematic licensing requirements for healthcare institutions and workers to stock, prescribe, or dispense opioid analgesics and must simplify the prescribing procedure that currently creates a barrier to timely treatment with morphine for patients with pain. Problematic dispensing procedures should be revised, and the current complex and wasteful record keeping system improved. Inspections of healthcare institutions that work with opioid analgesics should be conducted so as to minimize their impact on the provision of and access to medical care, and Ukraine’s criminal code should be amended to differentiate between intentional and unintentional violations of the rules of handling opioid medications.

***

Our research found that when strong opioid analgesics are available, they are provided in a way that fundamentally deviates from WHO recommendations, with each of the five core principles it has identified routinely ignored.[20]

Principle 1: Pain medications should be given orally whenever possible. If a patient cannot take medications by mouth, rectal suppositories, or under-the-skin injections should be used.In Ukraine no oral morphine is available. Doctors use only injectable strong opioids for pain treatment. Instead of injecting morphine under the skin, as the WHO recommends, injections are given into muscles. This results in large numbers of unnecessary intramuscular injections, which are unpleasant for patients and carry a risk of infection. Throughout the three years he was on strong pain medications, Vlad received thousands of unnecessary injections with pain medications. His mother compared his bottom, where most of the injections were administered, to a “mine field.”

Principle 2: Pain medications should be given every four hours to ensure continuous pain control.While the WHO recommends that patients receive strong pain medications every four hours, most patients in Ukraine get them only once or twice per day. As the effects of morphine last for four to six hours, this means that such patients are without adequate relief for most of the day. While doctors prescribe weaker pain medicines and other medications for the intervals, these are not potent enough to provide effective relief and expose patients to unnecessary side effects. Our research suggests this practice is largely due to the requirement in Ukrainian law that healthcare providers directly administer injectable strong opioid analgesics to patients. Doctors at various health facilities told us that they do not have the resources for a nurse to visit patients at home six times per day.

Principle 3: The type of pain medication (basic pain reliever, weak opioid, or strong opioid) should depend on severity of pain. If a pain medication stops providing effective relief, a stronger medication should be used. International research suggests that about 80 percent of terminal cancer patients need a strong opioid pain medicine for an average period of 90 days before death.[21] Yet figures we received from various hospitals in Ukraine about the percentage of cancer patients who receive morphine or other strong opioid analgesics and the average number of days patients receive them suggest that many patients are started on strong opioid analgesics late, if at all. In the six hospitals and one polyclinic department of a city hospital for which we received such data, we found that in the best case only about one-third of terminal cancer patients received a strong opioid analgesic—in most cases it was far less—and in some cases for far less than 90 days.

Principle 4: The dose of medication should be determined individually. There is no maximum dose for strong opioid pain medications. While the WHO treatment guideline specifically states there should be no maximum daily dose for morphine, both Ukraine’s Ministry of Health and the Zdorovye Narodu pharmaceutical company, the only manufacturer of morphine in Ukraine, recommend a maximum daily dose of 50 mg of injectable morphine. This dose is far below levels of morphine used safely and effectively for the treatment of severe pain in other countries. We found that many doctors in Ukraine, though not all, adhere to the recommendation and cap the dose even when the patient is still in pain.

Principle 5: Pain treatment should be delivered according to the patient’s needs. Because nurses have to come to patients’ homes to administer morphine injections, it is not the patient’s schedule but that of the healthcare worker that determines when the patient receives his medications. As a result, patients wait in agony for nurses to arrive or do not need the medicine when the nurse is present.

While our research focused mostly on the plight of cancer patients, we also documented a number of cases of people who had severe pain due to other diseases or health conditions. We found that these patients face even greater challenges in getting access to good pain treatment. General practitioners and other specialists are rarely trained in treating pain and often worry about prescribing strong opioid medications to non-cancer patients. Several patients with non-cancer pain told us that their doctors ignored their complaints about pain or told them it would simply go away by itself once the cause had been treated.

***

Three areas—health policy, education, and drug availability—contribute to the limited availability of palliative care and pain treatment in Ukraine. The World Health Organization sees each of these three areas as fundamental to the development of palliative care and pain management services and has urged countries to take action in each, observing that measures in each area cost little but can significantly impact the availability of palliative care.[22]

Health Policy The WHO has recognized palliative care as an integral and essential part of comprehensive care for cancer, HIV/AIDS, and other health conditions and recommends that countries establish a national palliative care policy or program.[23] While the Ukrainian government has established the Institute of Palliative and Hospice Medicine in the Ministry of Health and created a number of hospices and palliative care beds, no national palliative care policy exists at this time and the government has not undertaken a coordinated effort to address barriers to palliative care. The government’s failure to address critical issues like the lack of oral morphine and the need to develop home-based palliative care are particularly problematic.

Education The World Health Organization recommends that countries adequately instruct healthcare workers on palliative care and pain treatment.[24] Yet in Ukraine official curricula for undergraduate and postgraduate medical studies do not provide any specific education on palliative care and pain management. The WHO cancer pain treatment guideline is barely taught in medical or nursing schools, if it is taught at all. Many healthcare workers interviewed did not understand the basic principles of pain management and palliative care.

Drug availability The WHO recommends that countries establish a rational drug policy that ensures availability and accessibility of essential medicines, including morphine. Under the UN drug conventions countries must ensure adequate availability of opioids for medical purposes while also preventing their misuse.[25] However, Ukraine’s primary focus has been to prevent misuse of these medications. Human Rights Watch recognizes that such prevention is particularly important in countries that, like Ukraine, face major problems with illicit drug use—the country is home to an estimated 230,000 to 360,000 injecting drug users—and corruption in the healthcare sector.[26] But these efforts should not interfere with adequate availability of controlled substances for legitimate, medical purposes.

Ukraine’s drug regulations are far more restrictive than required under the UN drug conventions and contain numerous provisions that directly interfere with the delivery of good pain care, discourage doctors from prescribing opioid medications due to excessively burdensome bureaucratic requirements, and generate fear among doctors of the legal repercussions of prescribing these medications.

To its credit, Ukraine’s government recognizes the need for reform to ensure effective pain treatment and palliative care services. It has established the Institute of Palliative and Hospice Medicines in the Ministry of health, created hundreds of hospice beds, and removed some problematic provisions from its drug regulations in 2010.[27] In an October 2010 meeting with Human Rights Watch the then head of the National Drug Control Committee expressed concern about the lack of narcotics licenses at pharmacies in rural areas and said his committee was exploring solutions.[28]

***

Under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Ukrainian government is obligated to take steps “to the maximum of its available resources” to progressively realize the right to health. In keeping with this, the government should formulate a plan for the development and implementation of palliative care services, ensure the availability and accessibility of morphine and other medications that the World Health Organization considers essential, and ensure that healthcare providers receive training in palliative care. The Ukrainian government’s failure to do so violates the right to health.

Under the prohibition of torture and ill-treatment, the Ukrainian government has an obligation to take steps to protect people under its jurisdiction from inhuman or degrading treatment, such as unnecessary suffering from extreme pain. As the UN special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment has noted, “failure of governments to take reasonable measures to ensure accessibility of pain treatment … raises questions whether they have adequately discharged this obligation.”[29] The fact that public healthcare facilities in Ukraine offer pain treatment in a way that fundamentally deviates from well-established international best practices and that the government has not taken steps to change this calls into question whether the government has fulfilled this obligation. It may thus be liable under the prohibition of torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

This report focuses specifically on the poor availability of palliative care services in Ukraine. Human Rights Watch fully recognizes the problems that exist with availability and accessibility of other health services in Ukraine. The fact that this report focuses on a specific area of healthcare does not suggest that government authorities in Ukraine do not have an obligation under international human rights law to take reasonable steps to address problems in other parts of the healthcare system.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Ukraine:

- Ensure the availability of oral morphine throughout the public healthcare system.

- Amend licensing provisions of drug regulations to ensure that all rural healthcare clinics and hospitals can obtain licenses for strong opioid analgesics.

- Amend drug regulations to ensure that patients or their relatives can receive a reasonable take-home supply of strong opioid analgesics that realistically enables them to enjoy continuous pain relief.

- Disseminate WHO pain treatment guidelines to all healthcare facilities and roll out in-service training for all oncologists and other relevant healthcare workers.

In consultation with all relevant stakeholders, develop an action plan to ensure access to palliative care and pain management nationwide that provides for:

- Developing a national palliative care and pain treatment guideline, consistent with international best practices.

- Introducing instruction on internationally recognized pain treatment best practices in all medical and nursing schools and as part of continued medical education programs.

- A review process for Ukraine’s drug regulations aimed at ensuring adequate availability and accessibility of strong opioid medications for medical use while preventing their misuse.

To the Zdorovye Narodu Pharmaceutical Company:

- Amend product information for injectable morphine to bring it in line with available evidence.

- Start manufacturing oral morphine.

To the International Community:

- Raise concern with the government of Ukraine about the limited availability of quality palliative care and pain treatment services.

- Offer technical and financial assistance to implement the recommendations contained in this report.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between March 2010 and 2011, including field visits to Ukraine in April and October 2010. Field research was conducted primarily in the Kharkiv and Rivne provinces and in Kiev. Research in these provinces and Kiev was conducted jointly with the Institute of Legal Research and Strategies in Kharkiv and the Rivne and Kiev branches of the All-Ukrainian Network of People Living with HIV. We chose these locations for research because of their geographic diversity. Additional research was conducted in the cities of Lviv and Cherkassy. We also conducted desk research regarding palliative care availability in various other parts of the country.

During four weeks in Ukraine a researcher from Human Rights Watch and each partner organizations conducted more than 67 interviews with a wide variety of stakeholders, including 20 people with cancer, HIV/AIDS, and other life-limiting health conditions, or their relatives; 35 healthcare workers, including oncologists, AIDS doctors, anesthesiologists, palliative care doctors, and administrators of hospitals, hospices, and palliative care programs; and a dozen drug control and health officials.

Most interviews with patients and their relatives were conducted at their homes. Interviews were conducted in private.

Interviews were semi-structured and covered a range of topics related to palliative care and pain treatment. Before each interview we informed interviewees of its purpose, informed them of the kinds of issues that would be covered, and asked whether they wanted to participate. We informed them that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific questions without consequence. No incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed.

We have disguised the identities of all patients, relatives, and healthcare workers interviewed to protect their privacy, except when they specifically asked for their identity to be used. Similarly, we have disguised the names of the districts we visited to protect healthcare workers who, as government employees, may have legitimate concerns about a possible negative official response to their speaking out about problems with pain treatment.

All interviews were conducted in Russian by the Human Rights Watch researcher, a fluent Russian speaker. Most interviewees had no difficulty speaking Russian. Researchers from partner organizations provided translation where necessary.

In October 2010 Human Rights Watch presented preliminary findings to the Ministry of Health, the National Drug Control Committee, the section for the licit circulation of narcotic drugs of the Ministry of Interior, and the State Expert Center of the Ministry of Health. In March 2011, Human Rights Watch wrote a detailed letter summarizing the report’s findings to the pharmaceutical company Zdorovye Narodu, inviting it to respond to the findings and to present comments in this report. A copy of the letter is included in this report in Annex 1. No response had been received by the time the report went to print in late April 2011.

All documents cited in the report are publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch.

I. Overview: Palliative Care and Pain Treatment

Palliative care seeks to improve the quality of life of patients facing life-limiting or terminal illness. Its purpose is not to cure a patient or extend his or her life. Palliative care prevents and relieves pain and other physical and psychosocial problems, “adding life to the days, not days to the life,” in the much-quoted words of Dame Cicely Saunders, founder of the first modern hospice. The World Health Organization recognizes palliative care as an integral part of healthcare that should be available to those who need it.[30] While palliative care is often associated with cancer, a much wider circle of patients with health conditions can benefit from it, including patients in advanced stages of neurological disorders, cardiac, liver, or renal disease or chronic and debilitating injuries.

One key objective of palliative care is to offer patients treatment for their pain. Chronic pain is a common symptom of cancer and HIV/AIDS, as well as other health conditions.[31]Research consistently finds that 60 to 90 percent of patients with advanced cancer experience moderate to severe pain.[32] Prevalence and severity of pain usually increase with disease progression: several researchers have reported that up to 80 percent of patients in advanced stages of cancer experience significant pain.[33] Pain symptoms are a problem for a significant proportion of people living with HIV as well, even as the increasing availability of antiretroviral drugs in middle and low-income countries prolongs lives.[34] With the advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART), the international AIDS community has understandably focused on treatment for people living with HIV. Unfortunately, this has led to a widespread but incorrect perception that these people no longer needed palliative care. In fact, various studies have shown that a considerable percentage of people on ART continue to experience pain and other symptoms that improve with simultaneous delivery of palliative care and ART.[35]

Moderate to severe pain profoundly impacts quality of life. Persistent pain has a series of physical, psychological, and social consequences. It can lead to reduced mobility and consequent loss of strength; compromise the immune system; and interfere with a person’s ability to eat, concentrate, sleep, or interact with others.[36] A WHO study found that people who live with chronic pain are four times more likely to suffer from depression or anxiety.[37] The physical effect of chronic pain and the psychological strain it causes can even influence the course of disease, as the WHO notes in its cancer control guidelines, “Pain can kill.”[38] Social consequences include the inability to work, care for oneself, children, or other family members, participate in social activities, and find emotional and spiritual closure at the end of life.[39]

According to the WHO, “Most, if not all, pain due to cancer could be relieved if we implemented existing medical knowledge and treatments” (original emphasis).[40] The mainstay medication for treating moderate to severe pain is morphine, an inexpensive opioid made of poppy plant extract. Morphine can be injected, taken orally, delivered through an IV, or into the spinal cord. It is mostly injected to treat acute pain, generally in hospital settings. Oral morphine is the drug of choice for chronic cancer pain and can be taken both in institutional settings and at home. Morphine is a controlled medication, meaning that its manufacture, distribution, and dispensing is strictly regulated at both international and national levels.

Medical experts have recognized the importance of opioid pain relievers for decades. The 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the international treaty governing use of narcotic drugs, explicitly states that “the medical use of narcotic drugs continues to be indispensable for the relief of pain and suffering” and that “adequate provision must be made to ensure the availability of narcotic drugs for such purposes.”[41] The WHO includes both morphine and codeine (a weak opioid) in its Model List of Essential Medicines, a roster of the minimum essential medications that should be available to all persons who need them.[42]

Yet, approximately 80 percent of the world’s population has either no, or insufficient, access to treatment for moderate to severe pain and tens of millions of people around the world— including around 5.5 million cancer patients and 1 million end-stage HIV/AIDS patients—suffer from moderate to severe pain each year without treatment.[43]

But palliative care is broader than just relief of physical pain. Other key objectives may include provision of care for other physical symptoms and psychosocial and spiritual care for patients and family members who face life-threatening or incurable and often debilitating illness. Anxiety and depression are common symptoms.[44] Palliative care interventions like psychosocial counseling have been shown to considerably diminish incidence and severity of such symptoms and to improve the quality of life of patients and their families.[45]

Palliative care also seeks to alleviate other physical symptoms, such as nausea and shortness of breath, which are frequently associated with life-limiting illness and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.

The WHO has urged countries, including those with limited resources, to make palliative care services available. It recommends that countries prioritize implementing palliative care services in the community—providing care in medical institutions that deal with large numbers of patients requiring palliative care services and in people’s homes rather than at healthcare institutions—where it can be provided at low cost and where people with limited access to medical facilities can be reached.[46]

II. Rural Areas: Unavailable or Hard-to-Access Strong Pain Medications

Patients who live in remote places are doomed.

—Nurse, District 1, April 16, 2010.

The Story of Konstantin Zvarich

Konstantin, a 67-year-old pensioner from Poltava province in central Ukraine, was in many ways a typical Ukrainian from the countryside. Born in 1943, he grew up amid the hunger and devastation caused by World War II. As a young man, he served in the Soviet army before joining a collective farm, where he worked for 46 years. Konstantin was married, had a daughter, and a grandson.

Konstantin developed problems urinating in January 2009. When the pain became so severe he could no longer pass urine, he went to the local clinic where a doctor diagnosed prostate cancer. Two rounds of surgery provided temporary relief from the pain but were unable to remove all the cancerous cells which soon began to metastasize.

A sudden onset of intense pain in his hands and fingers alerted Konstantin that all was not right. He had further tests which revealed the cancer had spread to his bones, a condition often associated with severe pain. Konstantin told Human Rights Watch:

The pain was so bad that my whole body seemed to break. We would call the ambulance every two to three hours because I could not stand it.[47]

Doctors briefly hospitalized Konstantin and then sent him home with a prescription for tramadol, a weak opioid pain medication. Because few pharmacies in Ukraine stock tramadol—the result of the government’s 2008 decision to treat tramadol essentially like morphine—Konstantin’s relatives had significant difficulty obtaining the medication. When Konstantin was finally able to get tramadol, it turned out to be far too weak to control his excruciating pain. He used all ten ampoules of tramadol—the maximum allowed under Ukrainian law per prescription—in a day without bringing his pain under control.

Konstantin’s daughter, a medical doctor in Kharkiv, a city in eastern Ukraine, advised him to take a variety of over-the-counter pain medications, none of which provided much relief. Although he complained to his doctors of severe pain, Konstantin’s doctors never prescribed morphine. The local clinic did not have the necessary license. (See Chapter III for detail on licensing requirements and procedures.) For four or five months Konstantin suffered ongoing, severe pain. Describing one particular episode, he broke down in tears saying:

It was unbearable. I came home and the pain grabbed me so strongly. It was so bad that I didn’t know what to do with myself. It is so difficult to live like this.[48]

One day in late summer, Konstantin’s pain was so bad that his grandson, who was staying with him in the village, called his mother, telling her that his grandfather was “bouncing of the walls” from pain. The daughter decided she could no longer leave her father in the village and managed to arrange a bed for him at Kharkiv’s hospice. There, Konstantin finally received morphine for his pain. When Human Rights Watch interviewed him in April 2010, he said that his pain was finally under control at the hospice.

Konstantin died in June 2010 at the hospice.

Lack of Narcotics Licenses at Health Clinics and Pharmacies

Tens of thousands of patients with pain across Ukraine’s vast rural areas, where one-third of its population of approximately 46 million people lives, face a similar fate to Konstantin’s every year.

Local health clinics—known asambulatoria and feldshersko-akusherski punkt (FAP)—and even many small hospitals do not have the narcotics licenses necessary to stock and prescribe strong opioid analgesics.[49] Even when patients receive a prescription, few pharmacies in rural areas are licensed to fill prescriptions for opioid medications. Although most of these facilities could apply for a license, Ukraine’s drug regulations require that they have a separate room to store these medications, which is specially equipped to prevent break-ins and theft. The associated cost and lack of spare rooms are the main reasons that few health clinics and small hospitals obtain narcotics licenses.

During its research, Human Rights Watch and local partners visited the main hospitals in five districts in Kharkiv and Rivne provinces, in eastern and western Ukraine respectively. Known as central district hospitals, these are the main health facilities and administrative centers for the public healthcare system in their districts. While all the central district hospitals had narcotics licenses, doctors at each location told us that none of the clinics did. As Table 1 shows, this means that many patients live dozens of kilometers away from health facilities that are authorized to prescribe strong pain medications, even if their own village or town has a health facility. A health official in Rivne province told us that the same was true for all other districts in the province: all 15 central district hospitals have the license but none of the 92 ambulatorias or the 613 FAPs in the province do.

TABLE 1

District |

Size[50] (in sq. km) |

No. of district hospitals (with license) |

No. of ambulatories (with license) |

No. of FAPs (with license) |

District 1[51] |

467 |

1 (1) |

2 (0) |

5 (0) |

District 2[52] |

1,149 |

4 (1) |

13 (0) |

10 (0) |

District 3[53] |

1,011 |

1 (1) |

6 (0) |

8 (0) |

District 4[54] |

693 |

1 (1) |

4 (0) |

33 (0) |

District 5[55] |

659 |

2(1) |

6(0) |

27(0) |

District 6[56] |

695 |

1 (1) |

43(0) |

6(0) |

A Broken Pain Treatment Delivery System

The lack of licensed health facilities in rural areas means that patients or their relatives have to travel long distances to fill prescriptions for strong pain medications, often on poor roads and infrequent public transport. This already problematic situation is exacerbated by a pain treatment delivery system that does not allow clinics to provide patients and their relatives with a take-home supply of injectable morphine.

In general, doctors do not write prescriptions for strong opioid analgesics for patients to fill at pharmacies. Instead, patients receive morphine from hospital stock. While this has the advantage that patients do not have to pay for their medications, Ukraine’s drug regulations require healthcare workers to administer injectable strong opioid analgesics from hospital stock directly to the patient.[57] In other words, health facilities are not allowed to give the medication to patients or their relatives to take home and administer themselves. Instead, healthcare workers are supposed to visit patients at their homes for every prescribed dose of injectable morphine, often multiple times per day. The regulations do allow self-administration of oral opioid analgesics but none are available in Ukraine due to a lack of effort by the government to offer them through the public healthcare system.

This system is a major barrier to evidence-based pain care in Ukraine’s urban areas and often an insurmountable obstacle in rural areas, where healthcare facilities lack the resources for staff to travel to central district hospitals to pick up strong pain medications and then visit patients at home several times per day. As a result, many patients end up without access to the pain medications they need. Some patients may get pain medications once or twice per day. And only a very few—those who live in districts where doctors are willing to ignore government regulations—might get reasonably effective pain treatment.

In each of the five districts visited for this research, we found that healthcare providers struggled to deliver strong pain medications to patients. Their approaches (Table 2) varied from not providing strong opioid analgesics to patients outside district centers to trying to accommodate them. But even in the best scenario major and unnecessary obstacles remained to evidence-based pain care. In each district, doctors and nurses openly admitted that many patients, particularly those who live outside the district centers, were not getting the care they needed.

TABLE 2

Districts |

Approach to delivering pain treatment |

Districts 1, 2, 5, 6 |

Nurses from the central district hospital are responsible for delivering injections with pain medications during the day to patients who live in the district center; ambulances administer the injections during evening hours. Nurses and feldshers from local health clinics are responsible for delivering pain treatment to patients outside the district center.[58] They have to travel to the central district hospital every day to pick up the daily supply of medications for their patients and then visit them at their homes for each injection. Ambulances do not provide pain care outside the district center. |

District 3 |

Ambulances are responsible for delivering strong pain medications to all patients irrespective of where they live and at any time of the day. |

District 4 |

Healthcare workers provide patients or their relatives with a three-day supply of morphine and allow them to administer the medication themselves, in contravention of Ukraine’s drug regulations. Every third day, in return for the empty ampoules, patients or their relatives receive their medications for the next three days. Nurses and feldshers at local health clinics are instructed to check in on patients regularly to ensure that they are using the medications appropriately and are achieving adequate pain control. |

In districts 1, 2, 5, and 6, patients living outside the district center often had no access to strong opioid analgesics. The oncologist in district 2 expressed his frustration with the system:

Prescribing is not the issue; it’s delivering the medications. If possible, injections are done daily. If the area is close, the nurse can come every day to pick up morphine. They may come in the car of the FAP or ambulatoria and return the empty ampoules the next day. But not all FAP and ambulatoria have cars or they don’t have money for gas … If people live far away, the reality is that we make do with tramadol [a weak opioid] and dimedrol [an antihistamine]. We try the best we can. It is a tragedy for such patients. I look at them and I want to do something for them but I can’t.[59]

He added there were currently 30 end-stage cancer patients in his district, 20 of whom should have been receiving strong opioid analgesics. Instead, only three were.

The oncologist in district 5 said it was problematic for nurses and feldshers to travel to the central district hospital: “The rural healthcare system is poorly funded so they [nurses and feldshers] talk to the relatives who pay for their travel or bring the feldsher in their own cars.”[60] A nurse in district 1 said that staff at health clinics in her district cannot travel to the central district hospital to pick up morphine due to lack of transportation and time.[61] She took us to the house of a cancer patient who had been prescribed one injection of morphine per day, which was delivered via an ambulance that drove to his house every evening. The patient said he was in significant pain during the day and that “it would be very good to have a second injection. They make me feel so much better.”[62] The nurse said this was unlikely to happen:

If they prescribe an injection during the day, I will have to go to the patient’s home myself. That would mean that when I come to work at 8 a.m. I would pick up the ampoule from the chief nurse and then to walk to the patient’s home because there is no transportation. That takes 30 to 40 minutes. I would do the injection and then have to walk back. So it takes more than an hour to do one injection. That’s why we try not to prescribe during the day.[63]

|

Poland’s Rural Areas: A Different Story In Poland, morphine and other strong opioid analgesics are readily available in rural areas. Oral morphine is included in Poland’s essential medicines list, and pharmacies and health clinics are required to stock them. Although pharmacies may apply for a waiver to this rule—and quite a few do for opioid medications—there is a dense network of pharmacies with narcotics licenses throughout the country. When a pharmacy does not have opioids in stock, it can request them from a wholesaler and generally receive new supply within half a day. Opioid medications are provided free of charge at pharmacies. Doctors can prescribe a 30-day supply of oral morphine per prescription. The prescription can be filled at any pharmacy that has a narcotics license. Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Tomasz Dzierzanowski, palliative care physician |

Most patients in the district, she said, receive just one injection of morphine per day at most, leaving them in pain for most of the day. The nurse noted that occasionally patients get a second injection. She could remember only one patient in her eight years at the hospital who received three injections of morphine per day.[64]

Asked if they ever simply gave ampoules, small glass vials that contain morphine, to patients or their relatives to take home, healthcare workers in districts 1 and 2 said that they never did because of the strict control over these medications. The nurse in district 1 said: “The chief nurse [who is responsible for keeping records] is very strict with narcotic drugs. She has to protect herself because there can be an inspection anytime and if ampoules are missing she is in trouble.”[65] The oncologist in district 5 said that she and her colleagues sometimes provide patients from villages with a two or three-day supply.[66]

In district 3, where ambulances deliver pain medications to all patients, access to pain medications is significantly better. However, the ambulance service is not able to visit patients every four hours, so most receive two doses of morphine per day.[67] The chief doctor noted that poor weather—much of Ukraine sees significant snowfall in winter—can undermine the delivery of pain medications. He recalled difficulties during the winter of 2010 when major snowfall made many roads inaccessible:

If there is no road [accessible] we drive to the farthest point and then go on foot. But in some cases, getting to the village—not to speak of the house—was impossible this winter. We would contact the road service … We had three patients in [rural villages] and asked if they could at least open up the roads there. So we didn’t leave them without help. Of course we couldn’t stick to the timing of the injections.[68]

In district 4, healthcare workers violate Ukraine’s drug regulations—and potentially expose themselves to disciplinary and criminal sanctions—to improve patients’ accessibility to strong opioid analgesics. Here, patients and their relatives are responsible for obtaining pain medications from the central district hospital themselves. This gives them the option of getting more doses of the pain medications, and flexibility to administer it when most convenient for them. But it also places a significant burden on families who have to travel every three days to the central district hospital to collect medications.

The deputy chief doctor at the central district hospital recalled an elderly lady who had been coming to the central district hospital every three days for the last 18 months to pick up pain medications for her husband, a cancer patient. Even though there is a health clinic a kilometer from her house, she has to travel 20 kilometers every third day to the district center because the local clinic does not have a narcotics license.[69] A nurse at the central district hospital recalled a woman who had to leave her village at 4 a.m. every third day in order to catch a minibus to the district center and be able to make it back home the same day.[70]

Svitlana Bulanova told us of her sister’s plight caring for her daughter, Irina, a young woman with cervical cancer. She said that after Irina’s cancer had metastasized to her bones, she often screamed in agony due to the pain. Her doctors prescribed morphine but their local clinic did not have a narcotics license. So Irina’s parents had to travel the 25 kilometers to the district center every third day on public transport, a five-hour round trip that involved walking to the main road, waiting for a mini-bus to the district center, walking to the central district hospital to get the medications, and then repeating the journey on the way back.[71]

Pharmacies and Opioid Analgesics

Pharmacies play a limited role in distributing strong opioid analgesics to patients in Ukraine because most doctors prescribe these medications from hospital stock. But they do play a significant role in distributing tramadol, a weak opioid analgesic widely used in Ukraine.

Pharmacies must have a narcotics license before they can stock and dispense medications like morphine or tramadol. Yet, few pharmacies in rural areas have such licenses. The head of Ukraine’s National Drug Control Committee, the government agency responsible for issuing licenses, told Human Rights Watch in October 2010 that in Kirovohradskaia province there were only four pharmacies with such a license for 1.1 million people.[72] He said the situation in other provinces was somewhat less extreme but still highly problematic.[73]

This means that patients or their relatives often have to travel to district centers to fill their prescriptions, encountering the same challenges as described above. The chief doctor at the central district hospital in district 3, for example, said that in his district there is not a single pharmacy with a narcotics license so patients have to travel to the next district to fill prescriptions for tramadol. The doctor noted that there are just two buses per day to the town, making the trip very burdensome for people without their own transportation.

Ukraine’s drug regulations impose a strict limit on the amount of medication that can be prescribed per prescription. Table 3 shows the maximum amounts for several medications commonly used in pain management. This means that the patient or relatives have to obtain a new prescription every few days and then travel to the licensed pharmacy to fill it.

TABLE 3

Medication |

Maximum amount per prescription[74] |

In special cases of “lingering and chronic forms of disease” |

Typical daily dose |

Average time covered per prescription (in special cases) |

Tramadol injectable (1 ml – 50 mg; 2 ml – 100 mg) |

10 ampoules |

20 ampoules |

Up to 600 mg/day |

2 (4) days |

Tramadol tablets (50mg) |

30 tablets |

60 tablets |

Up to 400 mg/day |

4 (8) days |

Morphine (8.6 mg) |

10 ampoules |

20 ampoules |

20-25 mg / day[75] |

4 (8) days |

III. Throughout Ukraine: Ensuring Quality of Pain Treatment Services

The Story of Lyubov Klochkova

Lyubov, a woman in her mid-forties, was a tireless advocate for health rights. In her native city in Western Ukraine, she set up and ran successful health and legal service programs. But she spent much of her time traveling around Ukraine, Russia, and other parts of the former Soviet Union to share her expertise with others.

In 2008, as she was attending a conference, Lyubov suddenly felt desperately ill. Back home, medical tests found metastatic cervical cancer for which she was immediately treated. Several months later Lyubov returned to work; doctors thought her cancer was in remission.

But in early 2009 it became clear that all was not well. Rarely sick before, Lyubov now suffered colds that she could not seem to shake. By March a problem urinating sent her back to her doctor. Examinations showed that her cancer had recurred and that a tumor was blocking her kidney.

At around the same time Lyubov developed increasingly severe pain. At first her doctors tried to treat it with over-the-counter drugs and weak opioids that provided limited relief. Although her doctor recommended morphine Lyubov was ambivalent. She was worried that her body would get used to the medication and it would not be effective when she needed it most. A stoic woman, she continued to work, taking taxis to meetings to avoid having to walk. But by the end of May she had become too sick to leave the house.

With the pain now too great to bear, Lyubov agreed to take morphine.[76] “Why did I doubt for so long whether or not to start morphine?” she said when she got her first dose.

But the relief did not last long. Her doctor had prescribed one shot of morphine per day giving her relief for just about four hours. Over the next few weeks, as Lyubov kept complaining of persistent pain, doctors added an extra shot each week until she finally received five ampoules of morphine per day. Every morning, a nurse would visit the apartment and, in violation of Ukraine’s drug regulations, left the supply of morphine for the day. Lyubov’s husband would administer the medication when she needed it.

But five ampoules per day were not sufficient to control Lyubov’s pain. Her relatives were forced to ration the medication for when she needed it most. Lyubov would try to tolerate her pain. Her daughter told Human Rights Watch:

The daily dose was sufficient at most for three [effective] doses; in other words, for twelve hours. Because they brought us too little morphine we tried to save most of it for the night. During the day, we gave her drugs from the pharmacy and a minimal dose of morphine. Most of it we left for the night.[77]

By the morning, the morphine would be finished and Lyubov would anxiously wait for the nurse to come. Lyubov’s daughter said:

The nurse [normally] came at 10 or 11 a.m., but sometimes she was late. Mama would slumber at night. By 8 a.m. she would sit up rigid [from the pain] and wait for the nurse to [arrive with the morphine].[78]

A few weeks before her death Lyubov made an unpleasant discovery: she had reached the maximum daily dose for morphine and her doctor would not be able to prescribe any more ampoules. As Lyubov’s pain intensified the five ampoules gave her less and less relief. Lyubov and her daughter left no stone unturned trying to get a larger morphine dose:

We of course asked for a sixth ampoule. When they told us that five was the maximum we tried to find out through [a palliative care expert] whether that’s true, how that’s determined, and how we could get more of the medicine. Unfortunately, nothing worked out. The doctors said that they don’t have the right to prescribe more. We discussed it with the oncologist, the gynecologist, with all of them. We tried to mobilize everyone we could.[79]

But the doctors would not budge. Lyubov had to somehow make do with an increasingly inadequate amount of morphine. For several weeks she faced great suffering until, during her last few days, her kidneys could no longer clear the morphine from her body and her pain seemed to subside. She died in late July 2009.

Comparing Ukrainian Pain Treatment Practices with WHO Principles

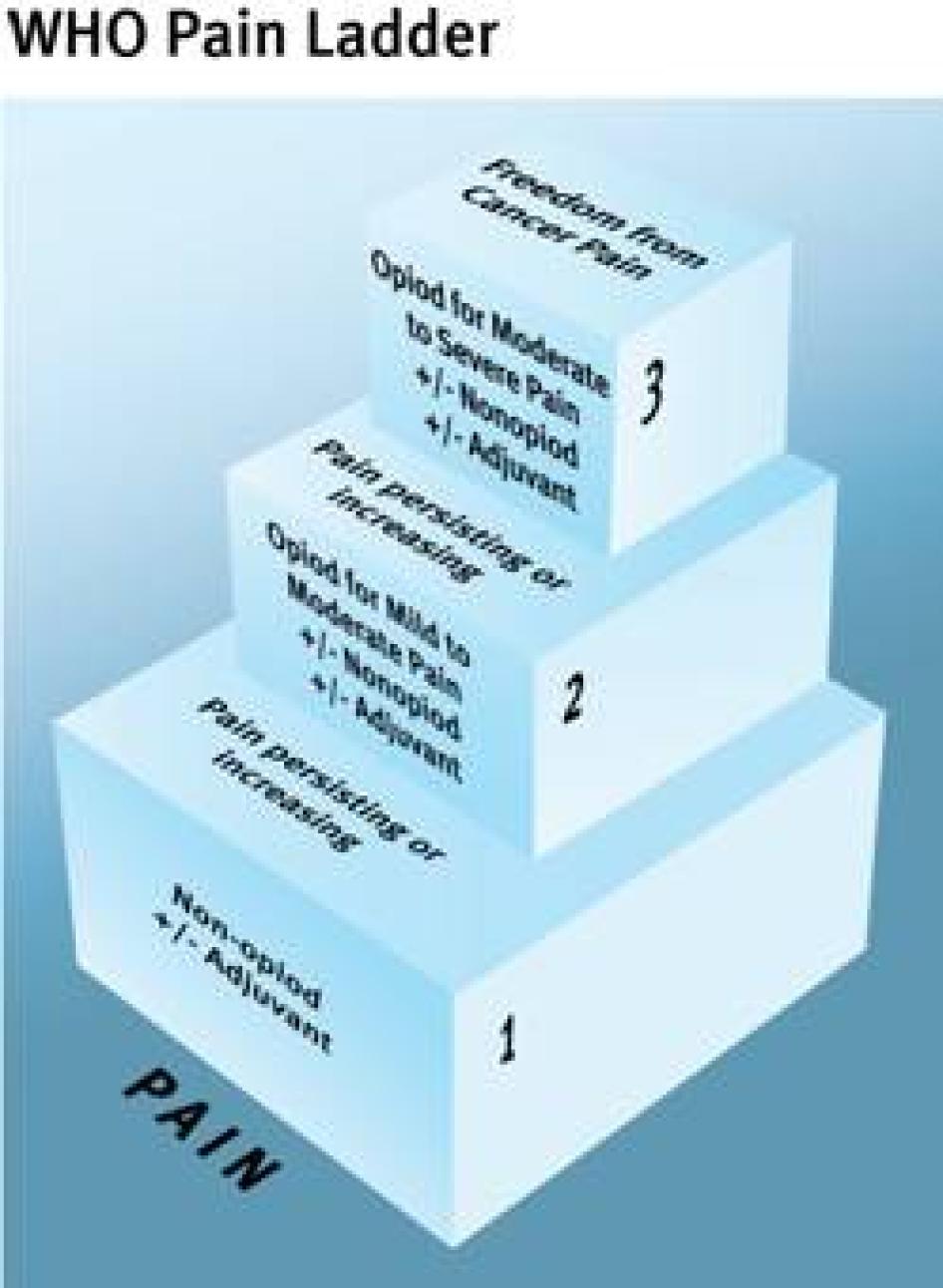

The WHO Cancer Pain Ladder, a treatment guideline first published in 1986, is an authoritative summary of international best pain treatment practices available.[80] Based on a wealth of pain treatment research that spans decades, it has formed the basis for cancer pain treatment in many countries around the world. It has also been used successfully to treat other types of pain.[81] The treatment guideline is organized around five core principles for treating pain (see Table 4). The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) have also developed cancer pain treatment guidelines, which follow these same core principles.[82] If followed, WHO estimates, the ladder can result in good pain control for 70 to 90 percent of cancer patients.[83]

Our research has found that standard pain treatment practices in Ukraine deviate fundamentally from World Health Organization recommendations, with all five core principles articulated in the treatment guideline widely ignored.

Under the right to health, governments must ensure that pain treatment be not only available and accessible, but also that it be provided in a way that is scientifically and medically appropriate and of good quality.[84] This means that healthcare providers should provide pain management in a way that is consistent with internationally recognized best practices. Governments, in their turn, have to create conditions which allow healthcare providers to do so.

TABLE 4: Comparing the Core Principles of Cancer Pain Treatment with Ukrainian Pain Treatment Practices

WHO Recommendation |

Ukraine’s Practice |

Principle 1: Pain medications should be delivered in oral form (tablets or syrup) when possible. |

Patients receive morphine by injection only. |

Principle 2: Pain medications should be given every four hours. |

Most patients receive morphine once or twice per day, in exceptional cases three or four. |

Principle 3: Morphine should be started when weaker pain medications prove insufficient to control pain. |

Patients are often started on morphine only when curative treatment is stopped, irrespective of pain levels. |

Principle 4: Morphine dose should be determined individually. There is no maximum daily dose. |

Patients are routinely injected with one ampoule of morphine at the time, irrespective of whether this is too little or too much. Many Ukrainian doctors observe a maximum daily dose of 50 mg of injectable morphine, even if it is insufficient to control the patient’s pain. |

Principle 5: Patients should receive morphine at times convenient to them. |

Administration of morphine depends on work schedules of nurses. |

Principle 1: “By Mouth”

If possible, analgesics should be given by mouth. Rectal suppositories are useful in patients with dysphagia [difficulty swallowing], uncontrolled vomiting or gastrointestinal obstruction. Continuous subcutaneous infusion offers an alternative route in these situations. A number of mechanical and battery operated pumps are available.

—WHO Treatment Guideline[85]

The first principle of the WHO cancer pain treatment guideline reflects a fundamental principle of good medical practice: the least invasive medical intervention that is effective should be used when treating patients. As injectable analgesics provide no benefit over oral pain medications for most patients with chronic cancer pain, the WHO recommends the use of oral medications. Also, using oral medications eliminates the risk of infection that is inherent in injections and is particularly elevated in patients who are immuno-compromised due, for example, to HIV/AIDS, chemotherapy, or certain hematologic malignancies. When patients cannot take oral medications and injectable pain relievers are used, it recommends subcutaneous administration (under the skin) to avoid unnecessary repeated sticking of patients.[86] Hence, oral morphine, which the WHO considers an essential medicine that must be available to all who need it, is the cornerstone of the treatment guideline.[87]

In Ukraine, however, oral morphine is not available at all. In fact, it is not even a registered medication. A recent survey of European countries found that Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Ukraine are the only countries in Europe where oral morphine is altogether unavailable. Armenia is currently looking for a supplier of oral morphine.[88] The only non-injectable strong opiod analgesics available in Ukraine are Fentanyl patches that release the analgesic through the skin but at a cost of about 267 to 467 hryvna (US$33.75 to 58.38) per patch (active for three days). They are unaffordable for most Ukrainians and are not available in government clinics and most pharmacies.[89]

While the WHO recommends that injectable pain relievers should be injected under the skin, standard practice in Ukraine is to give morphine by intramuscular injection. This means that patients who get morphine every four hours, as recommended, are unnecessarily injected six times per day. On average, patients with advanced cancer who have severe pain require 90 days of treatment with morphine, so a typical patient receiving morphine every four hours would get injected in the muscles 540 times over that period. In interviews, patients and their families said that receiving multiple injections in the muscles was unpleasant, but they were also resigned to the fact that the alternative—unrelieved cancer pain—was far worse.

Patients who are emaciated due to their illness face particular difficulties with intramuscular injections as they have little muscle tissue left. In such patients it may be challenging to vary the place of injection and there is a risk that part of the morphine will end up outside the muscle tissue, resulting in poor absorption of the medication and inadequate pain control. In interviews, both healthcare workers and patients spoke of these difficulties. Lyubov’s daughter, for example, told Human Rights Watch:

The last two weeks we didn’t inject in the behind anymore. The morphine was no longer absorbed. So we started doing intravenous injections in the hand but that’s painful … Of course, if you compare the pain from the injection to the cancer pain it’s not comparable…[90]

Vlad’s mother, Nadya, said that multiple injections of morphine and other medications over the course of several years had turned her son’s behind into a “mine field.” “There was nowhere to inject anymore. It no longer absorbed the medication. The last months we injected in the legs, from the thigh to the knee and in the hand,” she said. One of the injection sites became infected and developed a small hole in the hand. “We only just cured it when he died.”[91] Svitlana Bulanova said that toward the end of her niece Irina’s life, they “had no place left to inject.”[92]

Healthcare workers acknowledged occasional problems due to emaciation. Some said that they alternated the place of injection in such cases. For example, a nurse in district 4 said that they would do one injection “in the shoulder, another in the hip. We switch around.”[93] Several others said that they would switch to subcutaneous injections in such situations.[94] Most healthcare workers we interviewed said that they wished they had oral morphine tablets, saying it would significantly simplify their work. The oncologist in district 5 said: “Patients often ask for strong pain medications in tablets but we [don’t have them].”[95]

Principle 2: “By the Clock”

Analgesics should be given “by the clock,” i.e. at fixed [four hour] intervals of time. The dose should be titrated against the patient’s pain, i.e. gradually increased until the patient is comfortable. The next dose should be given before the effect of the previous one has fully worn off. In this way it is possible to relieve pain continuously.

Some patients need to take “rescue” doses for incident (intermittent) and breakthrough pain. Such doses, which should be 50-100% of the regular four-hourly dose, are in addition to the regular schedule.

—WHO Treatment Guideline[96]

The second principle reflects the fact that the analgesic effect of morphine lasts four to six hours. Thus patients need to receive doses of morphine at four-hour intervals to ensure continuous pain control.

This principle is not followed in rural areas because of the requirement in Ukraine’s drug regulations that a healthcare provider administers the morphine to the patient.[97] Our research also found the same to be true in urban areas. Even in places where population density is much greater and distances smaller, Ukraine’s healthcare system does not have the capacity—or is unwilling to dedicate the resources—to visit patients at home every four hours. So most patients get just one or two doses of morphine, leaving them without adequate pain control for sixteen to twenty hours every day. Even the “lucky” patients who get three or four doses of strong pain relievers daily face significant intervals between injections when their pain is not properly controlled.[98]

Table 5 shows the frequency with which morphine injections are provided to out-patients through a number of hospitals that we and our partners visited.

TABLE 5

Hospital |

Maximum frequency |

Delivery System |

Therapeutic department of a Kharkiv polyclinic |

Nor more than two injections per day. |

A team of nurses and drivers delivers pain medications to patients. |

Rivne polyclinic |

Generally two injections, morning and evening. Maximum is four. |

A team of nurses and drivers delivers the injections to patients. |

District 1 |

Generally one injection, rarely two. |

Ambulance delivers injection in evening. If second injection is prescribed, nurse has to administer. |

District 2 |

One or two. |

Ambulance delivers injection in evening. If second injection is prescribed, nurse has to administer. |

District 3 |

Up to three. |

Ambulance delivers throughout district. |

District 4 |

Three to five. |

Ampoules are given to patients or relatives for self-administration. |

District 5 |

One or two (up to six if nurse offers take-home supply). |

Nurses visit; occasionally, a take-home supply is provided. |

District 6 |

One or two. |

A team of nurses and drivers delivers injection to patients at home but only in the district town. |

While the requirement that healthcare workers administer every dose of morphine to the patient poses the greatest barrier to following the WHO recommendation that morphine be administered every four hours, insufficient training of healthcare providers is another significant obstacle.

Our interviews with healthcare workers suggest that most are unaware of the WHO’s recommendation for four-hourly administration of morphine. Standard procedure appeared to be to start patients on a single shot of morphine in the evening and then add a second injection and more if patients complain of persistent pain. None of the healthcare workers interviewed felt that this was inappropriate or substandard medical practice. For example, the nurse at a polyclinic in Rivne told us:

Patients generally get two ampoules per day: in the morning and evening. It usually begins with an evening dose at 9 or 10 p.m. Sometimes it happens that the next day, the patient already asks for more because it was enough for the night but [not for] the whole day … Before 10 p.m. severe pain syndrome begins again. Then a new prescription is prepared for an extra dose.[99]

A man whose mother died of cancer in 2008, explained how doctors prescribed morphine:

They registered us. Then the panel of doctors met [to discuss my mother’s case] and a decision was made to prescribe morphine. At first… one injection per day. Then, if after a week it isn’t enough in the opinion of the panel, the dose is increased. So there is a correction of the dose over time. So we eventually got two milliliters per day, one milliliter in the morning, one in the evening.[100]

Bridging the Intervals between Morphine Injections

|

The Case of Tamara Dotsenko: The Difference Regular Administration Can Make Tamara Dotsenko, a 61--year-old breast cancer patient, developed severe pain in her spine and back when her cancer metastasized to the spinal cord. In her home village, the health clinic managed her pain by giving her an injection in the evening. Tamara told Human Rights Watch: “In the evening they would give me a shot. I would sleep well and didn’t feel pain. But then during the day it was a different story: pain, pain, pain and pain … I wanted to cry the whole time …” The pain medications they gave her during the day wore off too quickly to provide much relief. When Tamara could no longer take care of herself, she was referred to the hospice in Kharkiv. There, she got pain medications regularly. She said: “Here I get totally different pain treatment. Every six hours they give me an injection. It does not fully control my pain but it is much better than what I had at home. It’s better than having to bear that pain.” Human Rights Watch interview with Tamara Dotsenko (not her real name), Kharkiv, April 16, 2010. |

Healthcare workers and patients told Human Rights Watch that they use a large array of medications, including basic pain medications, weak opioids, muscle relaxants and sedatives, to try to dull the pain in the intervals between morphine doses. For example, a nurse at a polyclinic in Kharkiv told Human Rights Watch: “We never visit patients more than twice a day [to administer morphine]. But a regular nurse will visit to do other injections, other analgesics or muscle relaxants.”[101] She added, erroneously: “After all, morphine … injecting it three times per day is not really all that recommended.” The oncologist in district 3 said that if the three injections of morphine that the ambulance service can deliver each day are insufficient, “we use cocktails: dimedrol with analgin [an antihistamine with a weak pain medication], baralkhin [a weak pain medication], sibazon [diazepam, a sedative].”[102]

While the WHO treatment guideline provides for the use of weak pain medications and other adjuvant medications in addition to a strong opioid analgesic to enhance its analgesic effect or treat specific problems, they are not recommended to be used as an alternative as they are incapable of providing adequate relief.[103] Medications like antihistamines and tranquillizers may be appropriate to treat specific health conditions, such as allergies, nausea, or anxiety, but in Ukraine they appear to be used often primarily to make patients drowsy and dull the pain. Such use is not consistent with the WHO treatment guideline.

Principle 3: “By the Ladder”