From the Tiger to the Crocodile

Abuse of Migrant Workers in Thailand

Summary

I am Burmese and a migrant worker that is why the police don’t care about this case.... [M]y husband and I are only migrant workers and we have no rights here.

—Aye Aye Ma, from Burma, who was raped by two unknown Thai assailants after they shot and killed her husband on November 5, 2007, in Phang Nga province

As “Thailand” means the “land of the free,” it is our Government’s policy to ensure that migrants can enjoy their freedom and social welfare in Thailand while their human rights are duly respected.... [M]igrant workers, regardless of their legal status, can seek justice in Thailand’s court system for any violent abuses to which they have been subjected, and which are covered by these laws.

—Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva, on October 5, 2009, Bangkok

The thousands of migrant workers from Burma, Cambodia, and Laos who cross the border into Thailand each year trade near-certain poverty at home for the possibility of relative prosperity abroad. While most of these bids for a better life do not end as tragically as that of Aye Aye Ma, almost all play out in an atmosphere circumscribed by fear, violence, abuse, corruption, intimidation, and an acute awareness of the many dangers posed by not belonging to Thai society.

From the moment they arrive in Thailand, many migrants face an existence straight out of a Thai proverb—escaping from the tiger, but then meeting the crocodile—that is commonly used to describe fleeing from one difficult or deadly situation into another that is equally bad, or sometimes worse. Migrant workers are effectively bonded to their employers and at risk of rights violations from government authorities. In many cases, police, military, and immigration officers, and other government officials threaten, physically harm, and extort migrant workers with impunity. Those detained face beatings and other abuses. And whether documented or undocumented, migrants in Thailand are especially vulnerable to abusive employers and common crime, which the Thai authorities are very reluctant to investigate and sometimes are complicit in.

In interviews in Thailand from August 2008 to May 2009 and in follow-up research through January 2010, we found evidence of widespread violations of the rights of migrant workers from Burma, Cambodia, and Laos. The violations are not limited to one or two areas but range the entire length of the country from the Thai-Lao border gateway towns in Ubon Ratchathani to the seaports on the Gulf of Thailand to remote crossroads in areas on the Thai-Burma border. Many types of abuses are either embedded in laws and local regulations, such as restrictions on freedom of movement, or are perpetrated by officials, such as extortion by the police.

Human rights violations inflicted on migrants by police and local officials are exacerbated by the pervasive climate of impunity in Thailand. Migrants suffer silently and rarely complain because they fear retribution, are not proficient enough in the Thai language to protest, or lack faith in Thai institutions that too often turn a blind eye to their plight.

An in-depth interview with a long-time police informant, a Burmese migrant named Saw Htoo, provided alarming insight into the workings of the Thai police. Saw Htoo described beatings of migrant workers in detention, sexual harassment, and extortion. Saw Htoo told Human Rights Watch, “When they are doing the beating, usually the police use their hands. They like to slap the cheeks of the people. Mostly they hit with hands and kick. They don’t use weapons in the beatings. When the migrant who is arrested talks to the police, he needs to keep his head down when talking—because if a migrant looks at the police’s face while talking, the police will hit him.”

Beyond threats of ill-treatment, extended detention, and deportation, migrants constantly fear extortion by the police. Nearly all migrants held in police custody that we interviewed said that police had demanded money or valuables from them or their relatives in exchange for their release. Migrants reported paying substantial bribes depending on the area, the circumstances of the arrest, and the attitudes of the police officers involved. It is not uncommon for a migrant to lose the equivalent of one to several months’ pay in one extortion incident. And if they do not possess enough money to be released, frequently the arresting officers ask whether they have relatives or friends willing to pay to secure their release.

Migrants’ daily lives are restricted in many other ways as well. Migrant workers are prohibited from forming associations and trade unions, taking part in peaceful assemblies, and face restricted freedom of movement. Often they cannot leave the area where their work is located without written permission from employers and district officials. The government prohibits migrants from obtaining driver’s licenses. Governmental decrees in the provinces of Phang Nga, Phuket, Surat Thani, Ranong, and Rayong sharply curtail basic rights of migrants, including by prohibiting migrants from registering motor vehicles, owning mobile phones, or being outside their work or living premises after designated curfew hours. In December 2009, the Department of Land Transport made an important decision to permit registered migrant workers to apply for and receive motorcycle ownership documents, but the Thai government has yet to rule on the legal relationship of this new policy and the restrictions in the provincial decrees.

As a result, migrants find themselves arbitrarily stopped by police—or police imposters—searched, and relieved of their motorcycles, cell phones, and other valuables. As Burmese worker Say Sorn said, “It feels like I’m caged here. I have gone to Bangkok on a few trips ... but I am worried that if I am stopped by a police checkpoint ... I will be arrested because I am not Thai.”

Thai police often fail to actively investigate ordinary crimes against migrants as well as human rights violations by authorities. Migrants’ lack of trust in police is underscored by the frequent number of instances, several documented in this report, in which Thais who have committed beatings or other physical abuses against migrants have then called the police to arrest and detain the migrant.

Migrant workers from Burma, Cambodia, and Laos make up a significant portion of the workforce in Thailand, with estimates ranging from 1.8 million to as many as 3 million workers and accompanying family members, roughly equivalent to 5 to 10 percent of the workforce. Partly due to the vagaries of registration, there are more undocumented than documented migrant workers in Thailand. But documented workers said they too are vulnerable to arbitrary arrest, financial shakedowns for release, and physical abuse. Employers often hold migrants’ worker ID cards, the keys to their legal presence in the country. They also retain the power to sign—or not sign—the crucial transfer forms that allow migrants to change jobs and retain their legal status.

Human Rights Watch found many serious abuses of migrants’ rights in the workplace. Workers who sought to organize and collectively assert their rights were subject to intimidation and threats by their employers, and retaliation if they filed grievances with Thai authorities. Both registered and unregistered migrant workers complained of physical and verbal abuse, forced overtime and lack of holiday time off, poor wages and dangerous working conditions, and unexplained and illegal deductions from their salary. When migrant workers miss a day or more of work, they often forfeit whatever outstanding wages are owed them. And migrant workers who might complain of mistreatment must always be on guard against employers who would take advantage of their lack of citizenship by calling in immigration officials, police, and even well-connected local thugs who act with impunity.

Police commonly extort money and valuables from migrants, either when they are stopped by police or while the migrant is in police detention. Migrants reported paying bribes ranging from 200 to 8000 baht or more, depending on the area, the circumstances of the arrest, and the attitudes of the police officers involved. For detained migrants who do not possess enough money to be released, frequently the arresting officers asked whether they had relatives or friends willing to pay to secure their release.

The Thai Constitution of 2007 guarantees basic human rights. And Thailand is a party to the major human rights treaties, which provide that non-citizens are entitled to the same rights as citizens, except for political rights such as voting or running for office. Unfortunately, the Thai government has done little to ensure basic rights are extended to migrant workers and their families.

Thai government policies on migrant worker registration and residence are complex and frustrating for many migrants and their advocates. The requirements, conditions, and costs to migrants of remaining in Thailand legally have undergone significant changes since 1996. New formal migration channels have so far been underutilized due to the complexities and slowness of procedures, and higher costs involved.

A policy announced in 2008 requires registered migrant workers to verify their nationality with officials of their own government. This means more than one million registered Burmese migrant workers must apply before February 28, 2010 to return to Burma and seek the approval of the Burmese military government to receive a temporary passport, and complete the process before February 28, 2012. To date very few have applied, with many justifiably citing fears of possible criminal sanction in Burma for originally leaving the country illegally. A crackdown on undocumented migrant workers, and those registered workers who fail to enter the nationality verification process, may begin in March 2010. In preparation, on December 29, 2009, Deputy Prime Minister Sanan Kachornprasart issued an order that established a high-level inter-agency committee led by the police who will lead efforts to arrest and prosecute migrants.

Thai government policy towards migrant workers has been largely shaped by national security concerns, as reflected in the language used in the five provincial decrees analyzed in this report and provisions of the Alien Employment Act of 2008. Government officials often regard migrant workers from neighboring countries as a potential danger to Thai communities, the interests of Thai workers, and national sovereignty. Public statements by senior Thai military and police officials, provincial decrees severely restricting migrants’ rights, and provisions of law all reflect this policy orientation, which manifests itself most concretely in the nearly absolute control that the Thai migration registration system grants to employers over migrant workers.

Corruption and criminal behavior by local police and other officials fuels a system of impunity in which rights violations by the authorities and common crimes against migrants frequently are either not investigated or fail to receive proper follow-up.

In the case of Aye Aye Ma, the woman quoted at the start of this report who was raped and whose husband was killed, for example, the police launched an investigation but the case has languished. Despite the discovery of semen at the crime scene that could be submitted for DNA testing and a police report that identified a Thai man from the area as a suspect, the case apparently never advanced beyond the initial stage. Aye Aye Ma, migrant advocates working on her case, and her Thai employer all told Human Rights Watch they believe her migrant status is the primary reason for the lack of police follow-through on the case.

Aye Aye Ma’s experience with law enforcement is not uncommon. While it is possible for migrant workers to achieve a measure of justice in certain high profile cases, the norm is one in which police discretion is paramount, and impunity for abuses against migrants is pervasive.

As the quotation of the Prime Minister on October 5, 2009, shows, the Thai government at the highest levels has been vociferous in asserting its commitment to upholding human rights for migrant workers. At the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva in June 2009, the Thai government declared its support for migrant worker rights, responding to an intervention by Human Rights Watch by stating “The Thai Government stands ready, ... to cooperate with all stakeholders in guaranteeing the basic rights of migrant workers, including, but not limited to, the NGOs and international mechanisms such as the [UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants].”

Human Rights Watch welcomes this commitment and looks forward to engaging with the Thai government on its treatment of its migrant population. But our research shows that the Thai government is violating the civil and economic rights of migrant workers set forth in the core human rights treaties to which Thailand is party.

The Thai government is reforming its policies towards migrants by adopting nationality verification procedures and revamping the use of government-to-government recruitment schemes. But so far only a small percentage of registered migrant workers have gone through nationality verification, and even fewer have entered Thailand through the formal recruitment channel set out in each bilateral agreement between Thailand and its three neighbors—Burma, Cambodia, and Laos. Serious difficulties with the nationality verification policy may make it hard for employers to legally maintain their migrant workforces in the near future.

Our research found government sanctioned discrimination and denial of status to migrants creates the conditions for flourishing corruption and extortion by local police and other officials which remain all too easily hidden from national authorities. Neither employers nor their migrant workers benefit from a situation in which corrupt officials have greater leeway to extort money in exchange for ignoring undocumented workers. But decisions on migration policies remain strongly influenced by national security agencies and their focus on maintaining structures and rules that permit close and continuous control of migrants, and effectively discourage migrants’ rights to freedom of assembly, association, expression, and movement. How the Thai government resolves the relationship between migrants’ human rights and security concerns will determine the course of its policies.

Key Recommendations

To address the human rights violations faced by migrants, the Royal Thai government should promptly:

- Establish a special commission to independently and impartially investigate allegations of systematic violations of the basic rights of migrants by police and other Thai authorities across the country. The commission should have the power to subpoena witnesses and compel provision of documentary evidence, and produce a public report. It should be empowered to make recommendations for criminal investigations in specific cases and for changes in laws, regulations, and policies that adversely affect the human rights of migrants.

- Immediately revoke provincial decrees restricting migrant worker’s rights in Phang Nga, Phuket, Ranong, Rayong, and Surat Thani provinces, and institute all necessary measures to ensure that the governors of all Thai provinces respect the fundamental rights of both documented and undocumented migrants.

- Take all necessary measures to end torture and ill-treatment of migrants in custody. Ensure that all allegations of mistreatment are promptly and thoroughly investigated and that all those responsible are appropriately prosecuted.

- Amend articles 88 and 100 of the Labor Relations Act of 1975 to allow for persons of all nationalities to apply to establish a trade union and serve as a legally recognized trade union officer, and ensure that the revised Labor Relations Act is fully in compliance with the standards set out in International Labor Organization Convention No. 87 (Freedom of Association).

Maps

|

© 2010 Giulio Frigieri/Human Rights Watch |

Northern Thailand

© 2010 Giulio Frigieri/Human Rights Watch |

Ubon Ratchathani

© 2010 Giulio Frigieri/Human Rights Watch |

Rayong and Eastern Seaboard

© 2010 Giulio Frigieri/Human Rights Watch |

Southern Thailand

© 2010 Giulio Frigieri/Human Rights Watch |

Bangkok and Surrounding Areas

|

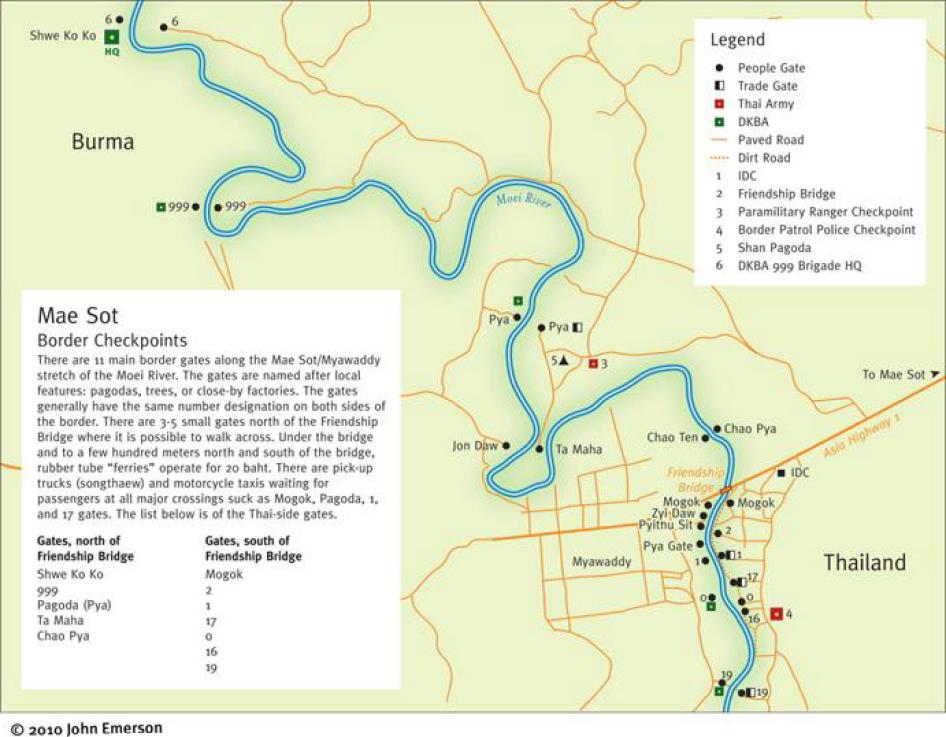

Mae Sot and Myawaddy

© 2010 Giulio Frigieri/Human Rights Watch |

Mae Sot Border Checkpoints

|

|

The ease in crossing the Thai-Burma border is demonstrated by Burmese migrants wading across the Moei River approximately 500 meters south of the Friendship Bridge connecting Mae Sot in Thailand and Myawaddy in Burma. © 2009 Human Rights Watch |

|

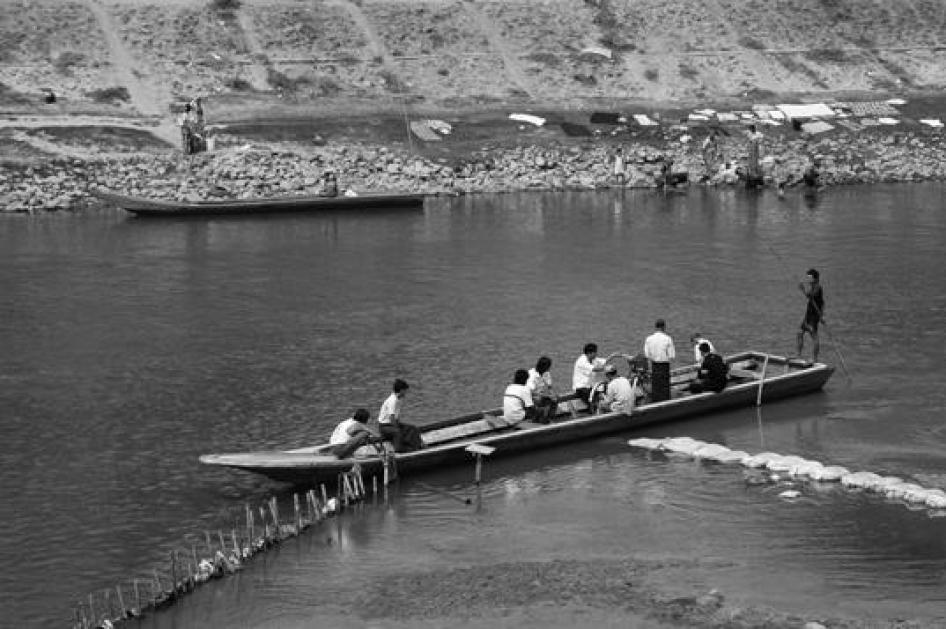

Burmese boatmen ferry passengers back and forth across the Moei river border between Thailand and Burma in Mae Sot, with crossings costing little and proceeding without travel documents. © 2009 Human Rights Watch |

Methodology

This report is based on interviews conducted between August 2008 and May 2009 by a team of researchers from Human Rights Watch, MAP Foundation, and the Yaung Chi Oo Workers Association (YCOWA). A total of 82 detailed individual interviews were conducted with migrants residing in Thailand, comprising 67 Burmese, 8 Laotian, and 7 Cambodian migrants. This work was supplemented by additional research and follow-up telephone interviews with migrant workers, NGO advocates, and government officials through January 2010.

We conducted interviews in Bangkok and in 10 different provinces so that our findings would reflect the different areas where migrants live and work across the country and the varying government policies in effect. Provincial government decrees in the provinces of Phang Nga, Phuket, Surat Thani, Ranong, and Rayong severely limit migrant workers’ rights. The provinces of Tak, Trad, and Ubon Ratchathani are major gateway provinces where migrants enter Thailand from Burma, Cambodia, and Laos. Samut Sakhon province is a major migrant-receiving province in the central plains of Thailand, subject to increased controls because of its close proximity to the capital city of Bangkok. Chiang Mai province has a significant influx of ethnic Shan from Burma, and has experienced high-profile police crackdowns on migrant worker use of motorcycles. The abuses described in this report reflect events that took place after December 1, 2006, when the major provincial decrees restricting migrant workers came into effect.

Wherever possible and in most cases, the interviews were held in private, but several were in the presence of relatives and friends of the interviewee. Human Rights Watch also conducted four group interviews with migrant workers in Chiang Mai, Phang Nga, Ubon Ratchathani, and Samut Sakhon. Interviews were generally conducted in the migrants’ language, sometimes with translation into Thai or English. All interviews used a questionnaire jointly developed in July 2008 by the research team, which is included as an appendix to this report. Researchers selected migrants for interview according to their knowledge of local migrant communities and their experience of human rights violations. Many were referred to us by local migrant organizations and other NGOs.

We have disguised the identity of all migrants we interviewed with pseudonyms and in some cases have withheld certain other identifying information to protect their privacy and safety.

Human Rights Watch and its research partners ensured that all interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the data would be collected and used. All orally consented to be interviewed and all were told that they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time.

To supplement formal interviews with migrants, we also conducted interviews with around two dozen NGO staff members working with migrant workers, lawyers and legal advocates, United Nations officials, and Royal Thai government officials, including those from the National Human Rights Commission, Ministry of Labor, Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, and Ministry of Interior. Contacts with the Royal Thai police took place in Bangkok, Pattani, Ranong, and Songkhla provinces but were deliberately limited because of security concerns.

In preparing this report, Human Rights Watch also closely reviewed Thai government documents and laws regarding migration and we consulted reports written by UN and intergovernmental agencies, NGOs, and migrant worker associations.

I. Failures of Thai Migration Policy

Labor Migration to Thailand

Migrant workers from Burma, Cambodia, and Laos make up a significant portion of the workforce in Thailand, with estimates ranging from 1.8 million to as many as 3 million workers and their family members, roughly equivalent to five to ten percent of Thailand’s workforce, plus their families.[1]

Long porous borders, ubiquitous networks of brokers and people smugglers, and the promise of high wages attract many Burmese, Cambodians, and Laotians to migrate to Thailand. In areas along Burma’s eastern border, Burmese ethnic minority migrants are fleeing human rights abuses by the Burmese government and armed forces and ethnic minority armies, as well as the economic hardship endemic to the region.[2]

Significant wage differences between Thailand and migrants’ home communities are factors encouraging migration. Migrants find they can earn more in Thailand, even when employers pay sub-minimum wages in violation of Thailand’s Labor Protection Act of 1998 (LPA).[3] Youth unemployment and underemployment in Burma, Cambodia, and Laos remain higher than in Thailand, as do current birth rates and the numbers of youth as a percentage of overall population.[4] Migration to Thailand has increasingly become an economic survival strategy for numerous rural families in neighboring countries.[5]

Thai employers complain it is becoming harder to find and recruit Thais into low-wage, labor-intensive work. Yet rather than upgrading workplace safety and improving wages, working conditions, and management practices, these same Thai employers turn to migrant workers who offer a fully flexible and cheaper workforce willing to do dirty, difficult, and dangerous jobs. Given the poverty that many migrants are fleeing and lack of protection offered by Thai authorities, employers frequently compel migrants to work long, exploitative hours, including through the night and on holidays. Employers find them easier to control because they either do not know of or are too intimidated to assert their rights under Thai labor laws.[6] They can be fired at will, and are less likely to organize a union or association to contest employer prerogatives. Employers often force migrants to accept daily wages and overtime rates below the legal minimum wage or intimidate and cheat them out of wages.[7]

Numerous Thai industries such as fishing and seafood processing, construction, agriculture and animal husbandry, and manufacturing (garment, textiles, and footwear) have essentially become dependent on documented and undocumented migrant workers as the core of their workforce. These low-cost workers in turn help maintain Thai export competitiveness.[8]

Regulatory Gaps and Failures

The majority of Burmese, Cambodian, and Laotian migrants to Thailand are undocumented, heightening the risk of abuse while compromising their access to legal protections and redress mechanisms. Undocumented migration is abetted by a weak migrant registration system in Thailand and ineffective or poorly implemented bilateral migration management schemes between Thailand and each of its three neighbors, defined in written memorandums of understanding (MOUs) on employment. Securing official travel documents is typically difficult, time-consuming, and expensive and most migrants do not obtain such documents.[9] A symbiotic relationship between people smugglers and corrupt government officials facilitates movement of migrants and placement in jobs, and, in some cases, contributes to human trafficking.[10]

While recognizing the continued importance of migrant workers to the Thai economy and the right of Thailand to regulate its workforce, Thai government policy continues to be dominated by national security concerns with little regard to workers’ basic rights. Provisions of the Alien Employment Act of 2008 illustrate clearly this undue emphasis on national security considerations. The act determines what work can be done by non-Thai workers and requires the location and duration of that work be determined in ministerial regulations that must explicitly take into consideration concerns of national security.[11] It provides broad discretion for investigators to conduct searches without court warrants if they believe there are undocumented workers on the premises.[12] The law imposes stiff criminal penalties, including imprisonment up to five years, on undocumented workers.[13]

Particularly worrisome are regulations accompanying the law that provide payments to informers for providing information or assistance in locating and leading to the arrest of undocumented migrant workers. NGO advocates continue to raise concern about this provision as providing an avenue for vigilantism against migrant workers.[14] The law also provides authority for an alien worker levy that is designed to discourage the use of migrant workers, though this legal provision has not yet been implemented. Reflecting the government’s insistence that migrant workers are temporary, the Alien Employment Act also requires employers to make deductions from migrant workers’ pay into a government-controlled fund to cover the costs of deporting migrant workers.[15]

In principle, migrant workers are accorded the same rights under Thai labor laws as Thai nationals except for specific exclusions on the right to establish and lead a labor union. In each of the bilateral MOUs on employment of migrant workers between Thailand and its three neighbors, there is a specific provision guaranteeing that migrant workers will be protected in accordance with all laws of the receiving state.[16]

A new Thai migration policy requires that by February 28, 2010, all documented migrant workers in Thailand must formally apply to go through a nationality verification process with officials of their own government. All workers who do not apply will become undocumented from March 1, 2010, onwards.[17] After verification, migrants will receive a temporary passport from their own government in which a visa issued directly by Thai Immigration will be placed, thereby legalizing their entry into Thailand. Migrants with a temporary passport and visa will be permitted to travel throughout Thailand without restriction, which is a positive development for migrants’ rights. Unlike arrangements with Cambodia and Laos in which verification is done by consular officials of those countries in Thailand, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) government in Burma insists that all Burmese migrants must return to one of three border towns in Burma—at Kawthaung, Myawaddy, or Tachilek—to apply for nationality verification. By September 25, 2009, 118,916 migrant workers had completed the nationality verification process—57,609 Cambodians and 58,430 Lao, but only 2,877 Burmese.[18]

Nationality verification for Burmese started on July 15, 2009,[19] but since verification is determined by the SPDC, the procedures exclude ethnic Rohingya, a Muslim minority population in Burma that has long been denied citizenship by the Burmese government.[20] Burmese migrant workers report they are gravely afraid of being forced to reveal information to the SPDC about their relatives and family in Burma, subjecting them to possible reprisals or extortion.[21] Many long-term migrants, especially those from the Shan and Karen ethnic groups whose political leadership has been involved in long-term insurgencies against the Burmese military government, also expect they will not be included on SPDC citizenship registration lists. Finally, migrants express fear that they could face retaliation for returning to Burma without a passport or other appropriate document, which is a violation of Burma’s Immigration Act of 1947 (Emergency Provisions) and can involve penalties of six months to five years in prison, and a fine.[22]

A coalition of Thai trade unions and NGOs filed a complaint with the UN special rapporteur on the human rights of migrants concerning the Thai government’s failure to provide accurate information about nationality verification or to rein in illegitimate brokers who defraud and overcharge workers.[23] Refugee advocates have expressed concerns about mixed flows of migrant workers and persons fleeing persecution from Burma who are shut out from asylum procedures because of the Thai government’s unwillingness to allow screening of migrants for refugee status, including the more than 200,000 ethnic Shan long excluded from consideration as refugees as a matter of Thai policy.[24]

Both nationality verification and the opening of new, formal migration channels have far underperformed expectations, raising fundamental concern about whether these mechanisms are able to effectively replace the current migrant registration scheme. Efforts to persuade new migrant workers to enter Thailand through formal channels set out in bilateral MOUs also have foundered because of higher costs, longer delays in placement than the informal migration processes, weak implementation, and disagreements on issues related to recruitment and use of agencies. By the end of December 2007, just 14,151 migrant workers (7,977 Cambodians, 6,174 Laotians, but no Burmese) had traveled through formal government-to-government migration channels to be placed in jobs in Thailand.[25]

The Thai government’s national security concerns appear to extend to migrant children and newborns. Gen. Sonthi Boonyaratglin, the deputy prime minister who led the 2006 military coup d’etat, reportedly said on a visit to Samut Sakhon in November 14, 2007, that Thailand would solve the problem of migrant children by arranging for deportation of all pregnant migrant women and that Thailand’s National Security Council (NSC) would take the lead in this initiative. General Sonthi, who at the time was also the head of Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC), stated:

There have been many problems concerning high birthrates, disease control, conflicts with Thai people and among themselves along with social issues, which will all become long-standing problems. They [the migrants] may demand more and more for their rights. These problems may become unsolvable one day.[26]

NGOs, mainstream media, lawyers, and other groups strongly condemned the proposal, which was quietly allowed to lapse when Prime Minister Gen. Surayudt Chulanont’s military-appointed government stepped down in December 2007.[27] But the initial proposal reaffirmed the perception among registered migrant workers that Thai government policy is discriminatory, and government officials cannot be trusted to ensure that their basic rights are respected. Even though Gen. Sonthi was unable to implement his proposed policy, there was a chilling effect on pregnant migrant women’s willingness to seek medical assistance.[28]

In a positive move made in October 2009, the Thai government began permitting registration of children of registered migrant workers holding work permits. However, in some cases, local officials insist on onerous documentation requirements that effectively frustrate this benefit.[29]

Migrants Rights under International Law

Thailand is party to the major international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),[30] the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR),[31] the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD),[32] and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention against Torture).[33] Thailand has also ratified many, but not all, of the major labor rights conventions of the International Labor Organization (ILO).

International human rights law protects the rights of non-citizens as well as citizens. Under the ICCPR, a state is obligated to respect and ensure the human rights of “all individuals within its territory.”[34] Non-citizens who have entered and reside in a state are entitled to all rights under the ICCPR except political rights, such as the right to vote and run for office.[35] Thus while article 25 of the ICCPR limits political rights to “[e]very citizen,” article 26 ensures that “All persons are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to the equal protection of the law”[36]

These protections for migrants extend to economic, social, and cultural rights. According to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in its General Comment No. 20 on non-discrimination, “The ground of nationality should not bar access to Covenant rights.... The Covenant rights apply to everyone including non-nationals, such as refugees, asylum-seekers, stateless persons, migrant workers and victims of international trafficking, regardless of legal status and documentation.”[37]

While the convention against racial discrimination, ICERD, provides for the possibility of differentiating between citizens and non-citizens,[38]the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) in its General Recommendation on discrimination against non-citizens, noted that this provision “must be construed so as to avoid undermining the basic prohibition of discrimination” as set out in other human rights treaties, such as the ICCPR and the ICESCR.[39]Thus while some political rights may be confined to citizens, states are under an obligation to guarantee equality between citizens and non-citizens as recognized under international law.[40]Therefore, “differential treatment based on citizenship or immigration status will constitute discrimination if the criteria for such differentiation, judged in the light of the objectives and purposes of the [ICERD], are not applied pursuant to a legitimate aim, and are not proportional to the achievement of this aim.”[41]

Of particular relevance to the administration of justice in Thailand, the CERD recommends that states “[e]nsure that non-citizens enjoy equal protection and recognition before the law and ... ensure the access of victims to effective legal remedies and the right to seek just and adequate reparation for any damage suffered as a result of [discriminatory] violence.”[42]The CERD also calls for states to “[c]ombat ill-treatment of and discrimination against non-citizens by police and other law enforcement agencies and civil servants by strictly applying relevant legislation and regulations providing for sanctions and by ensuring that all officials dealing with non-citizens receive special training, including training in human rights.”[43]Claims of discrimination brought by non-citizens should be “investigated thoroughly,” and those against officials should have “independent and effective scrutiny.”[44]

The CERD also urges states to remove obstacles that prevent the enjoyment of economic, social, and cultural rights by non-citizens, notably in the areas of education, housing, employment, and health.[45]States should also “[t]ake measures to eliminate discrimination against non-citizens in relation to working conditions and work requirements, including employment rules and practices with discriminatory purposes or effects,”[46] and “to prevent and redress the serious problems commonly faced by non-citizen workers, in particular by non-citizen domestic workers, including debt bondage, passport retention, illegal confinement, rape and physical assault.”[47]The CERD noted that while states may refuse to offer jobs to non-citizens who lack a work permit, all individuals working are entitled to the enjoyment of labour and employment rights, including the freedom of assembly and association.[48]

II. Provincial Decrees—Controls on Migrant Workers

The overwhelming emphasis on presumed national security considerations in Thai government policy on migrant workers is also demonstrated by draconian decrees restricting migrants’ rights in five provinces (Phang Nga, Phuket, Ranong, Rayong, and Surat Thani).[49] All five provinces host significant numbers of migrant workers. Anusit Kunnagorn, a representative of the National Security Council (NSC), testified to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) that the NSC and Ministry of Defense believed it necessary to extend these decrees to all the other provinces because of problems with the existing migrant registration system.[50]

Three of the five provincial decrees cite concerns for “national security,” “security of society,” or “safety of life and assets” as a rationale for the measures, while the Rayong decree declares that certain groups of migrants “engage in behavior that make them a danger to society or will cause harm to public order and peace, and the lives and property of the citizenry.” The provincial decrees require employers to closely monitor and control their migrant workers. Some make employers financially responsible for any damages caused by the migrant workers they have registered, creating an incentive for employers to confine workers to their workplace. Others decree that failure to control migrant workers will result in the loss of hiring privileges for the employer and deportation of the workers concerned.

The provincial decrees violate basic rights due all persons under international law. Among the key provisions of the provincial decrees are restrictions on migrant worker gatherings and curfews and severe restrictions on migrants’ use of mobile phones, motorcycles, and cars.

Even in provinces without specific provincial decrees, Human Rights Watch found restrictions on rights to freedom of movement, association, assembly, and ownership of property, though such restrictions were not formally promulgated in government decrees.

In Samut Sakhon province in central Thailand, a major receiving area for migrant workers from Burma, the provincial governor, Wirayuth Euamampa, took steps short of a provincial decree. The governor’s October 26, 2007 letter to the provincial Department of Employment and to employers stressed the need to control migrant workers more closely. The letter posited that “Burmese migrants give rise to many problems, such as those involving public health, stateless children, as well as problems of crime and lawlessness.” Furthermore, the letter continued, “currently there is the spreading of migrants’ culture through festivals and other various events and this is not appropriate and should not be supported because it will give rise to the feeling of community belonging and ownership which could cause national security problems and are against the Government’s objective of allowing migrant workers to reside temporarily to work only.” The letter concluded by stating employers would be held accountable for ensuring proper, lawful behavior of their migrant employees, including through charges and court action if needed.[51]

A backlash from migrant worker representatives and NGOs criticizing Governor Wirayuth of racial bias and lack of cultural sensitivity[52] compelled him to issue a clarifying letter on November 28, 2007. This letter informed employers that they could let migrant employees arrange cultural activities as long as they did not jeopardize Thai national security or have a negative impact on Thai diplomatic relations with other countries—essentially banning migrants’ political protests against their home governments.[53] The NHRC has called for the provincial government of Samut Sakhon to revoke these two letters, but it has failed to do so.[54]

Migrant workers residing in provinces with these decrees told Human Rights Watch that since the promulgation of the decrees, police harassment and extortion has increased, particularly in connection with the seizure of migrants’ mobile phones and motorcycles. Besides the personal inconvenience, migrants who are denied mobile phones face greater difficulties calling for rapid assistance in emergencies. NGOs and migrant worker groups say that some migrant workers, such as live-in domestic workers, face higher risks of abuse because of inability to own and use a mobile phone.[55]

Deprived of motorized transport, migrants stated they find it more difficult to escape violence and access health care in emergencies. They have fewer options for conducting daily tasks like purchasing food at the market, sending children to migrant learning centers, or taking classes after work. For those working in remote agricultural work settings the restrictions are particularly onerous.[56]

Restrictions on Freedom of Association and Assembly

Various restrictions limit the basic rights of migrant workers in violation of international law. In Phang Nga, Phuket, and Ranong, a gathering of five or more migrant workers requires advance written permission from the government district chief. In Rayong and Surat Thani, any migrant gathering is prohibited, unless it is cultural or religious.

However, in Surat Thani, even religious activities are shut down if they have any political characteristics. A Burmese migrant worker reported the severe reaction of local police from the Muang district station in Surat Thani province when a local Burmese migrant worker association organized a religious merit-making event at a Buddhist temple on June 19, 2008, to honor the 63rd birthday of detained Burmese democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi.[57] With the support of the temple’s abbot, approximately 150 migrants came offering gifts to Thai monks resident at the temple. Some migrants wore shirts or other pieces of clothing with Suu Kyi’s visage and the migrants held a short procession inside the temple grounds holding several signs and two large photos of Suu Kyi.

Following a tip-off that the police were coming, the migrants stopped the procession and everyone retreated inside the templeand waited. Within minutes, the police district commander, accompanied by 12 policemen in eight vehicles, arrived and demanded to know where the protest was taking place. A test of wills between the abbot and the police commander ensued: the commander’s insistence that a protest had taken place was met with denials, while the abbot refused permission for the police to enter the wiharn[58] to arrest migrants. The police finally agreed that they would only check a number of migrants selected by the abbot who volunteered to come out of the wiharn but then seized the migrant worker ID cards of five migrants for further inspection at the police station.[59]

The association later surreptitiously distributed copies of a video of the procession taken by migrants. The migrant worker told Human Rights Watch:

People kept asking me “Wow did you do that?” It is so hard to do any sort of group activity like that because the police are always looking out. I know that our association will have a problem with the police in the future.... They have asked many questions about the association because they worry we are going to organize the migrants...They always look at these issues from the security view.[60]

A PowerPoint presentation created by provincial Ranong police identifies political activities by migrant workers that the police are seeking to prevent. A video of a protest held by Burmese monks and exiles in Mae Sot on May 24, 2009, was displayed in a slide entitled “Guarding against Burmese Buddhist monks entering to perform political activities as in Mae Sot district, Tak province, leading the Burmese people to demand the release of Aung San Suu Kyi.”[61]

Restrictions on Freedom of Expression

Whenever we are walking and talking on the street, if the police see us using the phone they will stop us and take it. If you want to talk to me about these kinds of cases, you will not be able to finish the interview today....It happens every day.

—U Win, a migrant worker from Burma in Surat Thani, August 27, 2008.

While migrants with money can easily secure a mobile phone and phone number in Thailand through a prepaid SIM card, their ability to use their phones is heavily restricted.

In Phang Nga and Ranong, decrees forbid migrants from using mobile phones and explicitly authorize government authorities to seize such phones on sight, while Phuket requires mobile phone usage to comply with an unspecified provincial “security policy.”[62] In Rayong and Surat Thani provinces, the provincial announcements use identical language stating that migrant workers are not permitted to use mobile phones because a mobile phone is not considered “a tool for work but instead is a tool that can convey information easily and quickly, which can impact national security.”[63]

According to migrants, both government officials and private citizens seize migrants’ mobile phones in these provinces. Even in remote villages, like the one in Phang Nga where Burmese migrant worker Soe Myo lives, the village chief has ordered migrants not to use phones. Soe Myo told Human Rights Watch, “I sneakily use it [mobile phone], I don’t let them know or see that I use phone, and when I walk on the street I turn off my phone and put it in my underwear.”[64] Soe Myo added that either the village chief or ordinary Thai villagers will confiscate his phone if they see it. U Ko Nai, from Burma, confirmed he also takes these precautions but on July 18, 2008, officers from the Highway Police Division stopped him on a road near his house in Kuraburi district. They extorted 2600 baht (roughly US$78)[65] and confiscated his mobile phone despite his pleas that he needed it for work. U Ko Nai said, “The next time I saw that policeman he smiled at me ... I saw that he carried my phone and used it.... It’s normal for the police, if they see a good phone they will take it.”[66]

Restrictions on Freedom of Movement

There are many dangers for workers who work at night. For example, when the workers meet Thai teenager gangs, they are robbed and beaten....The danger we face is invisible. If we were able to have mobile phones and motorcycles, we might manage to escape from the danger.[67]

—U Win, migrant worker from Burma, Muang district, Surat Thani province

All five provinces with provincial decrees on migrants impose nighttime curfews restricting migrant workers to their workplaces or residences. The curfew start times vary from 8 p.m. to 10 p.m. All of the decrees state that migrant workers may not move within the province without express written permission from the provincial Department of Employment.

Under all the provincial decrees, migrants are prohibited from using motorcycles or cars. Thais are not allowed to let migrant workers drive their vehicles either. When migrant workers are caught with a motorcycle, the police are likely to make them pay a hefty bribe, lose their motorcycle, or both. Zaw Zaw, a registered migrant worker from Burma in the construction industry in Surat Thani described how local police at a checkpoint on June 11, 2008, first took 4500 baht from his wallet, and then confiscated his motorcycle.[68] In some cases, local authorities allow the use of motorcycles provided the migrant is prepared to pay a regular bribe. Kyaw Win, also from Burma, said where he lives in Surat Thani migrants must pay 500 baht a month to the nearest local police post or their motorcycle will be seized.[69]

In remote areas, such as rubber plantations, provincial restrictions on migrants’ use of phones and motorized transport can cause major difficulties in cases of medical emergencies, such as accidents, poisonous snake bites, pregnancy and birth, and severe illnesses. Purchasing food and other daily necessities are made more difficult and expensive by migrants’ inability to drive motorized vehicles.

Without the ability to communicate or move about by motorcycle, migrants are more vulnerable to common dangers such as assaults and extortion by criminal gangs and persons posing as police or other authorities.

Several other provinces, including Chiang Mai and Chumpon, considered issuing similar decrees but finally abandoned their plans in the face of intensifying opposition from human rights groups and the media. Yet restrictions similar to those in the provincial decrees, particularly against migrants using motorcycles and mobile phones, are enforced by local police in many places. For instance, in Surat Thani, a documented Burmese worker, Ko Shwe, told Human Rights Watch how two police arrested him around 11 a.m. one day in July 2007, searched him, found his mobile phone, and confiscated it. He said, “The police told me ‘We are allowing you to work in Thailand—not to be happy, and go around, like you are on a picnic.’”[70]

Article 41 of the Thai Constitution of 2007 provides all persons with the right to own property and the Vehicle Act B.E. 2522 (1979) contains specific provisions regarding non-nationals’ vehicle registration for registered migrant workers. Throughout the duration of the research for this report, vehicle registration was effectively denied to migrant workers.[71] But on December 13, 2009, an important step forward was taken when the Department of Land Transport issued a decision that allows registered migrant workers to apply for and receive ownership documents for a motorcycle.[72] However, vehicle ownership is still denied to undocumented migrants, and no final decision has been made on permitting migrant workers from Burma, Cambodia, and Laos to apply for and receive a driving license. Furthermore, restrictions on migrants using motor transport under the five provincial decrees have yet to be rescinded or altered.

Complications involved in ownership and registration of motorcycles put migrants seeking to own motorcycles at risk. Mi Mi, a migrant from Burma, said police jailed her husband for receiving stolen property when a Burmese broker working for a Thai policeman sold him the policeman’s motorcycle and then failed to give the money to the policeman. Mi Mi said that even though her husband knew nothing about the arrangements with the policeman, it was her husband and not the broker who was jailed for two years.[73]

In 2008 Thailand’s National Human Rights Commission ruled that the provincial decrees violate several core articles of the Thai Constitution of 2007.[74] The NHRC declared that the decrees contravene article 30, which provides “All persons shall be equal before the law and shall enjoy equal protection under it....Unjust discrimination against a person on grounds of difference in origin, race, language, sex, age, physical conditions or health, economic or social status....shall not be permitted.” The NHRC also determined that bans on use of mobile phones in the decrees violate article 36 of the Constitution where it is determined that “A person shall enjoy the liberty to communicate with one another by lawful means.” And it found that the curfews and restrictions on gatherings of more than five migrants are contrary to article 63 of the Constitution, which states: “A person shall enjoy the liberty of peaceful and unarmed assembly.”[75] However, the provincial governors and Ministry of Interior have so far ignored the NHRC’s ruling, which the NHRC lacks the legal authority to enforce.

III. Human Rights Abuses against Migrants

If you pay money [to the police], you can do anything in our region. If you want, you can kill people ... I have seen dead bodies many times by the side of the road ... Our area is like a fighting zone ... when the police hear the sounds of gunshots, they will not come ... [later] the police will come ask what happened, and write down the information and then they go away, and that is all that happens.

—Saw Htoo, Burmese migrant worker who provided information to the Thai police, Mae Sot district, Tak province

Both documented and undocumented migrants in Thailand are vulnerable to arbitrary acts of violence, intimidation, and extortion from state authorities including police, military, and immigration officers as well as private individuals. These abuses include killings, beatings, sexual harassment and rape, forced labor, abductions and other forms of arbitrary detention, death threats and other forms of intimidation, and various types of extortion and theft.

Killings, Torture, and Physical Abuses against Migrants

When I saw this [killing], I felt that we Burmese people always have to be humble and have to be afraid of the Thai police. I feel that there is no security for our Burmese people [in Thailand] or for myself.[76]

—Su Su, Burmese migrant worker, August 24, 2008, Ranong province

Migrant workers and their families in Thailand are at particular risk of human rights violations by members of the security forces. Because of their precarious legal status, they also have far less effective avenues for redress in the event of killings, torture, and other ill-treatment in custody, or other abuses by the security forces. This fosters an environment of impunity and fear that exacerbates the tenuous circumstances in which migrants live.

In many cases, migrants have reported common crimes to the authorities only to have the police fail to conduct a genuine investigation, treat the matter with far less seriousness than they do comparable crimes committed against Thai nationals, or simply refuse to arrest alleged perpetrators despite detailed information from eyewitnesses. In other cases, migrants express grave fears that if they report a crime to the police, particularly when the police are involved, they themselves may be subject to retaliatory violence.

Killings by Security Forces

Su Su told Human Rights Watch that she witnessed the beating death of a Burmese migrant worker from Rangoon whom she estimated to be only 16 or 17 years old. She said he had traveled to the Thai port of Ranong to work on a fishing boat during a school break in order to earn his school fees. She told Human Rights Watch what happened near her home in early 2007:

He was coming out of the shop. There were two police officers on a motorcycle who stopped him and asked him if he had a work permit. But he could not speak Thai and so he did not reply....Those two police started to beat him and they kicked him in the chest until he died there. Many Burmese were watching and nobody went and helped because all of the people were afraid of those police, so nobody said anything about this killing, and nobody informed the police station. When the two police saw that the boy died, they went away on their motorcycle. I saw the next morning that the rescue foundation came and took the boy’s dead body and no police officer was with them ... I really wanted to help but I am afraid of those police.[77]

While violence against migrants is most prevalent among local police, a wide variety of police and paramilitary forces operate in Thailand, especially in the border areas. Often migrants cannot differentiate between them.

Maung Cho, a supervisor at a textile factory in Mae Sot close to the Thaungyinn River bordering Burma, told Human Rights Watch that “soldiers” were involved in the drowning death of his friend and co-worker, Ye Htun, on August 21, 2008. It is not clear whether these were Thai Army soldiers or members of another armed force under the Thai government but it is clear that they were present to try to break up a migrant worker rally.

As Maung Cho described the situation, a labor dispute had escalated when a factory manager called in soldiers from a nearby village checkpoint to deal with striking workers. The soldiers arrived armed with a shotgun and pistols. The workers outside the factory immediately fled, and soldiers fired in the air and yelled for them to stop—which produced the exact opposite effect. Many of the workers panicked and jumped into the swift-running Thaungyinn River to escape by swimming across the river to Burma. Maung Cho, who swam across the river, described Ye Htun’s death by drowning:

I turned around and could see Ye Htun struggling and he was trying to keep his face above the water ... He was maybe about 20 meters from the Thai side. There were about 10 workers who were already on the other river bank with me but we did not dare to go back and rescue him because the Thai soldiers were standing on the bank, looking at us, and pointing their guns at us. They were also walking back and forth on the riverbank near where Ye Htun was swimming and they pointed their guns at him. I could not hear what they were saying to him, but they were saying something—but it looked to me like they did not want him to come back to the Thai side.... Some of the workers who did not cross the river told me later that when Ye Htun’s head was going under water, one of the Thai soldiers said “Give him the bamboo,” meaning to use a piece of bamboo to help him. But the Thai soldiers did not help and by that time, Ye Htun’s head had gone underwater.

Maung Cho said Ye Htun’s body was never recovered. [78]

Torture and Ill-Treatment by Thai Authorities

Police torture of suspects in pre-trial detention in Thailand is well documented.[79] Migrant workers detained at police stations report similar practices, including frequent beatings and other forms of ill-treatment during pre-trial detention. The police use violence against detained migrants when they seek a confession of guilt or other information from a suspect or as a form of punishment, such as if a detainee looks directly at a police officer or fails to speak or comprehend Thai.

Sai Tao, from Burma, told Human Rights Watch that officers at the Saraphee district police station in Chiang Mai severely beat his brother Sai Aye after arresting him in December 2007 on suspicion of theft. A police officer called Sai Tao and told him to come to the police station to meet his brother. When Sai Tao arrived, the police immediately arrested and searched him, and confiscated his motorcycle.

During the initial questioning by police, Sai Tao said he stood close to his brother and was able to speak to him. His brother denied any involvement in theft and said the visible bruise behind his ear was from a beating inflicted by the police at the station. The police then took them both on a search of his brother’s room, but turned up no evidence of larceny.[80] Soon thereafter, Sai Tao was released, but his brother was held for further investigation. Sai Tao requested that the police call him when his brother was released so that he could pick him up.

Around 4 p.m. the next day, Sai Tao received a phone call from the police station saying they released his brother the previous night, but that he then stole something else, and while he was being chased, he fell off an apartment building. Sai Tao’s desperate search of hospitals led him to his brother at Maharaj Nakorn Hospital in the Suan Dok area. He was suffering severe head trauma and was unable to speak. His injuries required two operations and over 50 days of hospitalization. To this day Sao Tao’s brother remains severely disabled, unable to speak or walk by himself. Sai Tao believes the police were directly responsible:

I am sure that the police physically beat and abused my brother and made up the story of the apartment. I told them to call me if they released my brother and it makes no sense that they released him that same night after me.... My brother has never been involved in any criminal activity.... The story they told is just a lie, a cover story for what they did to my brother... I would like to take a case against the police, to hold them responsible....[81]

Aung Aung, a registered Burmese migrant worker, was traveling by train from Chiang Mai to Bangkok on the evening of August 2, 2009, when a railway policeman inspected his ID card and forced him to get off the train at the Lamphun province train station. When Aung Aung protested that his card was in order with the correct authorization and signatures, the railway policeman punched him in the face, and then repeatedly kicked Aung Aung until he collapsed on the ground.[82] The railway policeman and a colleague took Aung Aung back to the Chiang Mai railway police station, searched him, then “fined” him 1200 baht. On August 4, with support from MAP, Aung Aung filed a complaint against the police with the Chiang Mai provincial governor’s office. Since the case was filed, Aung Aung learned from neighbors in his old neighborhood in Sankampaeng district that the railway police have searched for him multiple times. Aung Aung now fears for his life and his case was taken up by the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand.[83]

Migrant workers who attempt to flee arrest are often beaten by the police. On August 5, 2008, Border Patrol Police (BPP) arrested Maung Kyi, an undocumented Burmese day laborer in Mae Sot, close to the village where he worked. According to Maung Kyi, he then jumped off the moving BPP pickup truck in an attempt to escape. Four BPP officers chased and caught him, repeatedly kicked him, and beat him severely on his legs with their batons. They dragged him back to the truck and another BPP officer kicked him in the chest, making it hard, Maung Kyi said, for him to breathe. The BPP released him part way between Mae Sot and his village, but he could not work for days because of his injuries. Twenty days later he still had bruises and scars from the beating he suffered.[84]

Oem Borey, a fisherman from Cambodia, told Human Rights Watch how his physical altercation with a Thai fishing boat captain resulted in his being further severely ill-treated by Thai police. Oem Borey described a fight that he had on board a boat in the Gulf of Thailand off the coast of Trad province on August 25, 2008. He says the captain accused him of disobedience, hit him with a metal pipe, and, when he fought back, the captain radioed other boat captains for assistance, who then arrived and beat him severely. When the boat returned to dock at Klong Makam in Trad province, the captain called the police and told them Oem Borey was drunk and had tried to steal the boat. Police from the nearby Klong Yai district station arrived, and Oem Borey says police beat him at the pier at least four more times on the back using their wooden batons until he lost consciousness.[85]

Oem Borey suffered a deep gash on the head, a broken nose, possible broken ribs, and other injuries, but he said the Klong Yai police refused to send him to the hospital. Instead, they held him without medical treatment in the police station lock-up for 13 days.[86] Oem Borey reported that during his detention, the police interrogated him once and accused him of attempting to steal the fishing boat. He said he was too scared to respond so he said nothing. The following day, the police forced him to fingerprint a Thai language document that he could not read. He received no explanation from the police about the content or purpose of the document. His sister negotiated a 2000 baht payment to the police for his release, plus an additional 300 baht to compensate the police for agreeing to help him find a new job.

Thailand’s ratification of the Convention against Torture in October 2007 has not resulted in more energetic efforts to combat torture and ill-treatment or to revise Thailand’s laws to conform to the requirements of the treaty. [87] And although the Thai Constitution of 2007 prohibits torture,[88] Thailand lacks a specific law on torture, which complicates efforts by migrants (and advocates for migrants) who undertake to raise a complaint of torture against a government official.[89]

Police Abuses: An Insider’s Account

Saw Htoo is an ethnic Karen migrant worker who worked closely for some 10 years as a member of a gang led by a police sergeant[90] in the area of Kilometer 48 village in Pop Phra district, Mae Sot province. Originally self-employed, Saw Htoo became vulnerable when police confiscated his legitimate passport in 2003, claiming it was fake. With no documentation, and as his overseas business partners had left the area, he progressively fell into working for the police sergeant. His duties as a gang member included providing information, collecting money from enterprises for the gang leader, and acting on the orders of the sergeant, who employs gang members to intimidate and extort migrant workers. In exchange, senior gang members like Saw Htoo had the opportunity to run profitable enterprises—in his case, operating an illegal lottery and managing the beer and wine shop at the sergeant’s compound and snooker hall—and receiving a percentage of the proceeds. Gang members frequently serve as intermediaries between migrants and police, negotiating payments for release of migrants from detention.

Saw Htoo performed all these functions and more. By his own admission, he physically beat migrants, served as a middleman for police to extort money from migrant families, and joined raids to detain migrant workers who were then brought to the police sergeant’s compound for interrogation. While he claims not to have killed anyone or witnessed any killings, he believes that they occur.

Gang membership offers police protection for some migrants and their families, power within the migrant community, and impunity for illegal acts and abuses. Saw Htoo said:

Many migrants in this area want to become [sergeant’s name withheld] luk nong [follower or employee] because this would make them free from being arrested because he will protect them. Also, when there are fights between the migrants, it is the police luk nong that have the upper hand and everyone is scared of them.[91]

However, with membership come dangers if a migrant gang member knows too much about his boss’ business, or if he crosses the boss. In May 2009, the police sergeant repeatedly beat Saw Htoo in different public locations in the Kilometer 48 area and conducted a mock execution.[92] Saw Htoo is now in hiding on the Thai-Burma border.

As a gang member, Saw Htoo said he saw and in some cases participated in police abuses against migrants, including beatings and torture while in detention, rape, sexual harassment, forced labor, and systematic looting of migrant workers’ money and valuables.

Saw Htoo said that the police in the area physically abused migrants on a regular basis. Interrogations at the house of the police sergeant heading the gang and the police post at 48 Kilometer village routinely included slapping, punching, and kicking the suspects. Saw Htoo said:

I saw it so many times when the migrants were arrested, they would be beaten by the police at the police station. Usually the arrested migrants didn’t understand what the policeman was saying because they did not speak good Thai—and so the policeman would kick the migrants.... I saw often the police use their hands to slap the faces of the migrants.... If any migrant looks up at the police while they are being beaten, that’s it—they will definitely be hit again.

The area is also a major transit route for workers moving from Burma into Thailand. Saw Htoo said that the police sergeant and his gang members detained and beat migrants and their guides who allegedly had not paid police bribes to transit the area. Beatings of migrants occurred at the sergeant’s compound[93] every two or three days. Saw Htoo recounted the severe beating that he, the sergeant, and two other gang members inflicted on three migrant workers in April 2009.

Saw Htoo believes the primary reason for these beatings is to force migrants to pay money to gain their release, “Really, he [the police sergeant] is just interested in extorting money from the migrants and he knows he can do this by catching them and beating them.”

Saw Htoo said he regularly saw migrant women coerced to sleep with police officers outside the station in exchange for their freedom, and spoke to women who had been raped in 48 kilometer police post. He stated that “If there is a young, good-looking woman, especially if the police think that she might be a virgin, she will be taken to sleep with the police.” Over the course of 10 years working with police at Kilometer 48, he said he knew of more than 20 instances during which migrant women were raped by police in a back room in the police post. He said, “I am the one who the relatives will send with the money to get the woman out of jail.... After they are released, those women are crying and telling me the story of what happened to them. Usually, the girls will be raped in the police station. In the 48 Kilometer police station, there is a small, narrow room with a bed that is used for this. They are just taking the girls out of the lock-up, and raping them in that room.”

Saw Htoo said that often the women are released after the police rape them, but in other instances, the policeman will pressure the woman to become his mistress.

Saw Htoo said police regularly steal valuables from migrant workers if they find them, and extort money from migrants and their families to release arrested migrants. He said, “I have seen police take money, and they also like to steal gold necklaces and other gold jewelry.... If a migrant worker does not have a migrant worker ID, the police will sometimes take that person’s mobile phone too.” Saw Htoo said he played the role of an intermediary between police and the families of arrested migrants. Police compelled migrants to call their relatives or friends to bring money for their release, and the families used Saw Htoo to serve as a negotiator because they were too afraid to talk directly with the police. He said:

At the police station, the police demand 3000, 4000, or even 5000 baht from each of the migrants.... If police ask for 3000 baht and the family of the migrant cannot afford that, they might propose to pay 2000 baht instead, and I have to help with this bargaining. If the money is paid, then the migrant will be let go.

Saw Htoo also described the use of forced labor over the course of approximately 20 days in March 2009. Each day the police sergeant arbitrarily apprehended Burmese migrants and forced them to dig a fish pond in his compound. Saw Htoo witnessed the sergeant accosting three migrants walking past the compound on their way to market, threatening them, and forcing a man to work for the day. He said the sergeant told the man’s wife, “You can go now and do what you want, come back at 5 p.m. and I will release him then.” He did not pay the man for his day’s work.

Saw Htoo’s detailed accounts shed light from an “insider’s” perspective on what migrant workers from Burma, Cambodia, and Laos have told Human Rights Watch about abusive treatment they receive from corrupt police in places in other areas of Thailand, and the impunity with which police are able to take advantage of migrants.[94]

Failure to Investigate Crimes against Migrants

The Thai police often fail to actively investigate ordinary crimes as well as human rights violations by the authorities against migrants. Migrants’ lack of trust in police is underscored by the frequent number of instances in which Thai’s who have committed beatings or other physical abuses against migrants have then called the police to arrest and detain the migrant.

This was evident in the case of Aye Aye Ma, a registered migrant worker from Burma, and her husband, Cho, in Phang Nga. According to Aye Aye Ma, around 3 a.m. on November 5, 2007, two men armed with hunting rifles, wearing masks and head flashlights[95] appeared where they were working in a rubber plantation and demanded money. Aye Aye Ma told Human Rights Watch:

My husband looked at me. Then that man who was talking shot my husband in the head, and I saw him fall ... I couldn’t believe it, I was shocked.... I started crying and yelled to my husband but I was also so afraid that I could not run to my husband ... And then those two men came over and grabbed me, and they ripped off my clothes. I think that they killed my husband because they wanted to rape me ... I kept yelling “Please don’t kill me! Please don’t kill me!” ... The whole rape took maybe 10 minutes, one raped me and then the other raped me. When they were finished raping me, they just walked away like nothing happened. They also stole our head flashlights and the rubber tree tapping knives from me and my husband.[96]

After the assailants left, Aye Aye Ma called friends for assistance, and they in turn contacted the Thai Muang district police and the Migrant Assistance Program (MAP). The police came to the crime scene, took photographs, and collected two used condoms with semen inside as evidence, and later interviewed Aye Aye Ma at the police station. A commanding officer, police Lt. Col. Kittichet Kittiratanasombat, ordered in the investigation report dated November 9, 2007, that a DNA test should be performed on the semen,[97] in line with standard police procedure that such tests should be done within three days of the collection of the evidence. But when MAP staff later went to inquire about the test, officers at the police station said the test had not been carried out because of budgetary constraints.[98] No results of any DNA test were ever shared by the police, who later admitted to MAP that one division in the police ordered the DNA test but then never provided any further information about the test to the police actually in charge of the investigation. At an interview at Thai Muang district two weeks after the crime, police showed two grainy photocopies of photographs in a police file to Aye Aye Ma, but she could not identify them because the men had worn masks and it was dark. As a result, the police investigators told MAP representatives that after one year they decided to suspend the case until new evidence is found.[99]

Besides the real possibility that police did not conduct a DNA test as ordered by their superior officer, Thai Muang police apparently did not pursue a suspect whose name and address were in the police report as one of the probable perpetrators.[100] Aye Aye Ma believes the police know who the perpetrators are because they may be individuals who have been implicated in the area for serious crimes in the past. For instance, her employer, a former sub-district chief, after hearing Aye Aye Ma’s description of the assailants, told her that those responsible could have been two men from a nearby village suspected in previous similar offenses.

Said Aye Aye Ma:

If the police really want to arrest the men that did it [murder], then they can do it. But they do not want to do it.... I am Burmese and a migrant worker that is why the police don’t care about this case ... I feel very bad about all of this, that the police have done nothing for me.... Really they know that I can’t do anything.... My husband and I are only migrant workers and we have no rights here.[101]

Since the last interview with the police two weeks after the murder and rape, police investigators have not contacted Aye Aye Ma or representatives of MAP, who accompanied her to file her case and who she designated as her official representatives. A follow-up letter from MAP to the police commander of Thai Muang district station did not receive a reply.[102]

U Win, from Burma, told Human Rights Watch that he and his co-workers witnessed the murder of his friend Thwar Sin in a vegetable field in Donsak district, Surat Thani province, on December 11, 2007, and that the police did not investigate the crime. For reasons they do not know (they were aware of no prior provocation), their Thai employer’s nephew hit Thwar Sin in the left shoulder and then in the head with a long-handled scythe. His fellow workers rushed Thwar Sin to Donsak Hospital, and then Surat Thani Provincial Hospital, where he died of his injuries. While U Win and several migrant workers were at the hospital, the local village headman and two policemen arrived and informed them the employer’s nephew was under arrest. However, on December 13, Thai villagers in the area told U Win that the police had released the assailant without filing any charges. No police officer ever contacted U Win or any of the other Burmese workers in the field who witnessed the attack, or the family of Thwar Sin, to investigate the murder. U Win said that without a sympathetic Thai to accompany them, they were too afraid to file a complaint with the police. He and the other migrant workers hoped that their employer would take responsibility, but the man did not take any action against his nephew. No compensation was paid to Thwar Sin’s wife, who was living in Thailand and pregnant at the time, and caring for her four-year-old son. U Win said:

I have no experience in filing a complaint with the police and I can face problems with the police if I do that. We are Burmese staying in Thailand. We should not go to the Thai police station—really, we do not believe that they will do anything for us ... We, in our conscience, wanted Thai authorities to take care of this case correctly. Though we come and work here as alien workers, we want to be treated with equally and justice before law. This is normal when Burmese workers are killed. The Thais never take any action and most of the cases disappear like this.[103]

Myo Myo, a Burmese migrant, told Human Rights Watch that she witnessed the killing of a newly arrived Burmese migrant worker in November 2007 by a Thai shop owner in Paknam sub-district in the Muang district of Ranong. She saw a dispute erupt between the shop owner and the Burmese man. The shop owner hit the Burmese man with a large piece of wood on his back and head, and he collapsed and died. His body lay on the ground for several hours until one of the Thai rescue foundations[104] retrieved the corpse. Myo Myo said that the police never came to investigate the killing. No one in the Burmese community reported the incident to the police because they were worried about having problems with the shop owner, who she believes has influence with the local police. She told Human Rights Watch:

Many Burmese saw this incident but nobody dared to say anything ... or inform the police. All of the Burmese people are afraid of him [the shop owner]. Sometimes I see the police come and talk to him and visit him, so I think he might work together with police. I have seen the police eat with him several times, and sometimes they drink beer in his shop. Sometimes there are two or three police who come and drink with him and their police car is parked right out front.[105]