Courting History

The Landmark International Criminal Court's First Years

Glossary

ASP |

Assembly of States Parties |

AU |

African Union |

BTF |

Belgian Task Force |

CAR |

Central African Republic |

CBF |

Committee on Budget and Finance |

CBO |

Community-based organization |

DRC |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

DSS |

Defence Support Section |

ECCC |

Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia |

EU |

European Union |

Ex-Comm |

Executive Committee, Office of the Prosecutor |

FNI |

Nationalist and Integrationist Front |

FRPI |

Ituri Patriotic Resistance Forces |

GCU |

Gender and Children Unit, Office of the Prosecutor |

GTA |

General Temporary Assistance |

ICC |

International Criminal Court |

ICCPP |

ICC Protection Program |

ICTR |

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda |

ICTY |

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia |

IDP |

Internally Displaced Person |

IRS |

Initial Response System |

JCCD |

Jurisdiction, Complementarity and Cooperation Division |

LRA |

Lord's Resistance Army |

MONUC |

United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo |

NGO |

Nongovernmental organization |

OPCD |

Office of Public Counsel for the Defence |

OPCV |

Office of Public Counsel for Victims |

OTP |

Office of the Prosecutor |

P1-P5 |

Professional (excluding management) grades of ICC staff (where P5 is the most senior) |

PIDS |

Public Information and Documentation Section |

SCSL |

Special Court for Sierra Leone |

SoP |

Standard Operating Procedure |

TFV |

Trust Fund for Victims |

UN |

United Nations |

UNHCR |

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

UNICEF |

United Nations Children's Fund |

UPC |

Union des Patriotes Congolais/Union of Congolese Patriots |

UPDF |

Uganda Peoples' Defence Force |

VPRS |

Victims Participation and Reparations Section |

VWU |

Victims and Witnesses Unit |

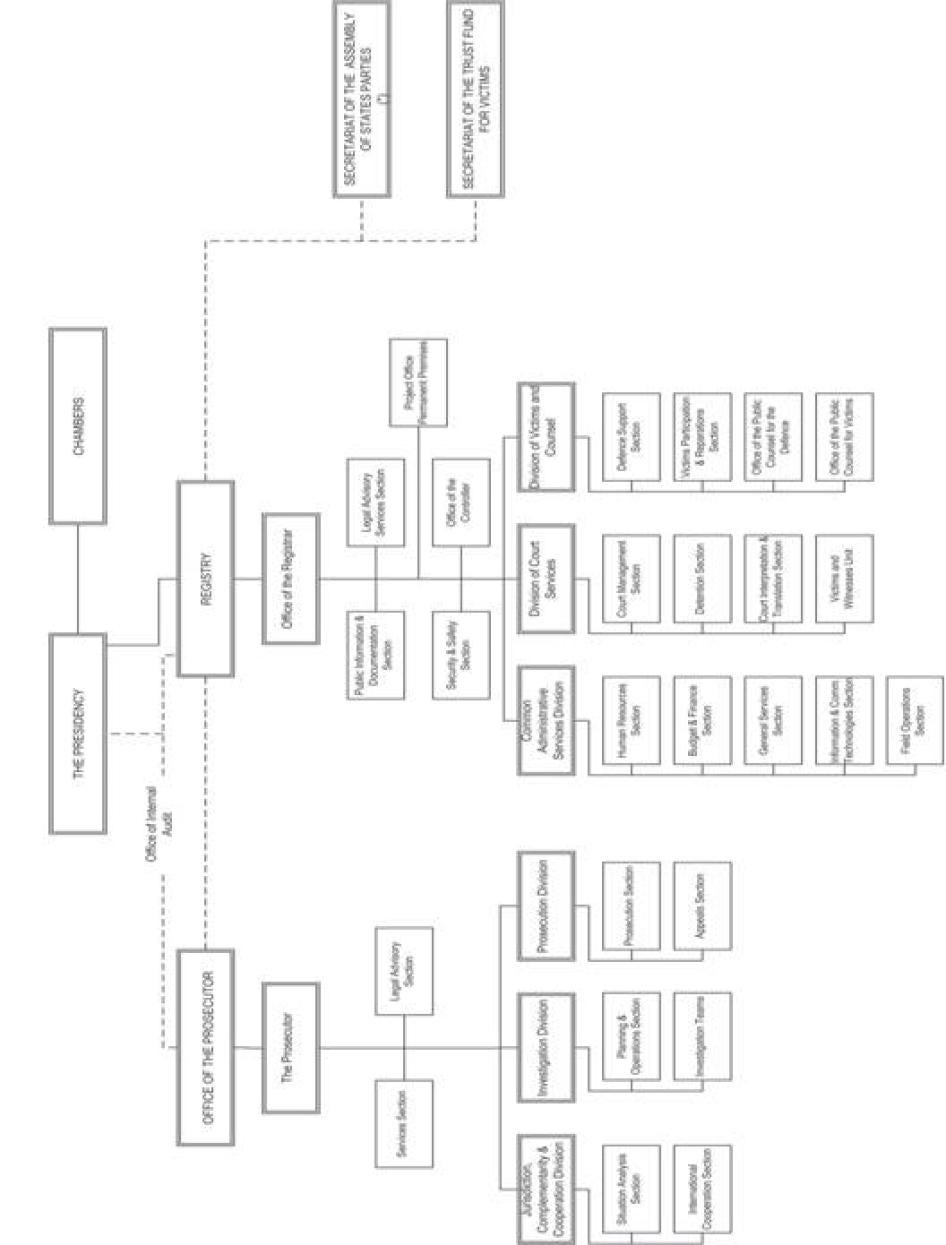

ICC Organizational Chart*

Summary

A. Introduction

On July 17, 1998, after five intense weeks of negotiations during the Rome Diplomatic Conference, representatives of 120 states from all regions and legal traditions achieved an historic development in the struggle against impunity. They agreed on a treaty creating the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, the world's first permanent court mandated to bring to justice the perpetrators of the worst crimes known to humankind-war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide-when national courts are unable to do so.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court entered into force on July 1, 2002, following its unexpectedly swift ratification by the required 60 states.[1] The selection of the court officials needed to implement the ICC's mandate soon followed. In March 2003 the first 18 judges of the court's bench were sworn in. The ICC prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, took office in June 2003 following his election by states parties to the Rome Statute. The institution's first chief administrator, the registrar Bruno Cathala, assumed office shortly thereafter. The ICC, once an aspiration, was finally becoming a reality.

Since then, the ICC has made significant progress. The prosecutor has opened investigations in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), northern Uganda, the Darfur region of Sudan, and the Central African Republic (CAR). These investigations-all of which have been conducted in situations of instability or ongoing conflict-have led to criminal charges against at least 12 alleged perpetrators "bearing the greatest responsibility" for horrific crimes, crimes for which not long ago they would have very likely enjoyed complete impunity (12 arrest warrants are publicly known; there may be other sealed warrants in existence). At this writing, four of these alleged perpetrators are in ICC custody in The Hague, and the others are stigmatized as accused war criminals evading justice. The ICC's establishment sends a strong signal to current and would-be perpetrators that complete impunity for the worst crimes will not be tolerated.

The ICC's progress is not limited to prosecutions. Against many odds and in the face of innumerable difficulties, the Registry has established field offices in sometimes unstable environments in relation to all four country situations under investigation to maintain ongoing contact with victims, witnesses, and affected communities. Court officials have made efforts to convey important information about the ICC's mandate and its work to affected communities in refugee camps, internally displaced person (IDP) camps, and remote villages. Witnesses have stepped forward to provide evidence, some of them so enabled because of the court's capacity to protect them from the threats that they face in doing so. Victims from Darfur, Uganda, and Congo have applied and have been accepted to participate in ICC proceedings. Defense attorneys have at their disposal an independent office set up and funded by the court to provide them with essential legal support to help promote their clients' right to a fair trial.

Not surprisingly, in grappling with the enormous challenges of setting up an unprecedented judicial institution, ICC officials have made mistakes. Indeed, Trial Chamber I's June 2008 decision to "stay" the proceedings against Thomas Lubanga-thus suspending, in all respects, the court's first-ever trial-

because of the prosecution's inability to disclose to the court and to the defense potentially exculpatory information collected under the Rome Statute's confidentiality provision emphasizes this point. In this report, Human Rights Watch identifies some of these failings and makes recommendations aimed at improving the fairness and effectiveness of ICC operations. We have also stressed how important it is for the court-including the prosecutor-to more proactively engage with affected communities to make its work meaningful and relevant to them. This will require a complete and deeply rooted shift from the ICC's prior ambivalence to doing so, which was evident in the court's early approach to outreach and field operations, and the prosecutor's investigations. It will mean an approach that fully embraces the importance of these communities in realizing the court's mandate. Indeed, these are the very communities that the ICC was created to serve.

These problems notwithstanding, the biggest challenge facing the court in executing its mandate is primarily outside of its control: apprehending suspects. Without its own police force, the ICC must rely on the cooperation of the international community to enforce its orders. International justice institutions have benefitted from some meaningful cooperation from states to date, but the ICC's mandate to investigate the worst crimes in situations of ongoing conflict tests their willingness to cooperate to a much greater degree. Traveling from capital to capital, the prosecutor has been an increasingly outspoken advocate for the cooperation that the ICC needs from states and intergovernmental organizations. Unfortunately, while there have been some positive developments, much more is needed. The international community, including states parties, has too often downplayed justice amid other important diplomatic objectives, such as peace negotiations and the deployment of peacekeeping forces. However, experience shows that failing to adequately prioritize justice contributes to instability or renewed cycles of violence. It is the responsibility of the Rome Statute's states parties (106 at this writing) and multilateral institutions like the United Nations (UN) to respond to the ICC's requests for cooperation. The very success of the court depends on it.

This report sets out Human Rights Watch's assessment of certain aspects of the ICC's operations to date. We have made a number of recommendations aimed at improving the court's effectiveness in executing its mandate, particularly as it relates to human rights issues. The confidential nature of many of the court's operations also influenced our analysis and evaluation. In addition to urging the international community to provide more cooperation, key recommendations include:

- We urge the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) to improve its capacity to conduct investigations by recruiting more investigators, especially those with considerable experience. This is particularly important to build cases against those in senior leadership positions. In addition, a recurring feature of many of our recommendations is the need for the Office of the Prosecutor to step up its engagement with affected communities to explain the non-confidential aspects of its investigations, so as to manage expectations and combat misinformation.

- While progress has been made in the court's outreach to affected communities to answer questions about the court and to explain its work, we believe that the ICC should embark on a more robust, tailored, and targeted outreach campaign to increase its impact. This will very likely require additional resources, which we urge states parties to provide as needed.

- We urge the court to enhance its level of field engagement. This includes making field offices more accessible to communities most affected. It also means increasing the involvement of field-based staff in devising and developing outreach and other strategies that implicate members of affected communities, such as victims' participation and witness protection. The offices should also have a head of office to facilitate more effective field engagement.

Our recommendations are presented throughout the text of this report and are summarized in its concluding chapter. Taken together, Human Rights Watch's recommendations will take time to implement and will significantly increase the ICC's operating budget. We appreciate the importance of ensuring efficiency in the court's operations, and we recognize the court's responsibility to properly manage its resources. At the same time, we wish to underscore that to be effective, justice for the worst crimes cannot be done "on the cheap." We therefore urge states parties, upon careful consideration, to provide additional resources as necessary.

Despite its shortcomings, the International Criminal Court has made strong progress in the first years of its operations. Moving forward, Human Rights Watch urges ICC officials to continue to apply the lessons learned from past experience to improve the court's fairness and effectiveness, but also to make its work relevant to the communities most affected by the crimes in its jurisdiction. The victims deserve nothing less.

B. Methodology

Human Rights Watch has been closely monitoring the work of the ICC since the beginning of its operations in 2003. Human Rights Watch researchers participated in numerous consultation meetings with ICC officials, together with other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) under the umbrella of the Coalition for the International Criminal Court (CICC), as well as bilaterally. The International Criminal Court has been uniquely open in its interaction with civil society.

Human Rights Watch carried out the field research for this report throughout 2007. In February and March 2007, researchers traveled to Kampala and northern Uganda (Gulu, Lira, and Kitgum) and conducted a number of interviews with local journalists, representatives of nongovernmental and community-based organizations (CBOs), government officials, and field-based ICC staff. Researchers also held a number of discussions with members of affected communities in IDP camps around northern Uganda. During April-May 2007, researchers traveled to the Ituri district and North Kivu and in July 2007 to Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo and met with persons including local journalists, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, government officials, field-based ICC staff, officials in the United Nations peacekeeping mission and other international agencies, and diplomats. In Ituri, Human Rights Watch researchers also traveled to small villages and interviewed members of affected communities. In July 2007, researchers visited two refugee camps in Chad and met with affected communities from Darfur, as well as United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) officials and ICC field staff. In all of our field research, when it was required to conduct interviews in local languages, this was done with the assistance of translators.

In addition, Human Rights Watch conducted telephone and in-person interviews with ICC staff in The Hague and in New York throughout 2007 and up to May 2008. Additional information for this report was gathered in New York and Brussels between September 2007 and July 2008 through phone and in-person interviews, email communications, and desk research.

Many of the individuals that we interviewed wanted to speak candidly but did not wish to be cited by name, so we have used generic terms throughout the report to respect the confidentiality of these sources.

I. Chambers

A. Overview

In courtrooms everywhere, an impartial, independent, and competent bench is essential to conducting all trials, and especially those entailing complex legal issues, while maintaining scrupulous fidelity to the rights of the accused and while managing proceedings efficiently. At the International Criminal Court, the bench shares with other organs of the court responsibility for meeting unique challenges including shaping the practice and policy of an international treaty-based institution, making meaningful a new model of victims' participation, protecting witnesses and victims in diverse, conflict-affected regions, and building support for the work of the court through representational activities, all while developing the nascent field of international criminal law.

These responsibilities are carried forward by the 18 judges of the court's Chambers, elected by the Assembly of States Parties (ASP)[2] to staggered, non-renewable nine-year terms and split between an appeals, trial, and pre-trial division.[3] In addition, the Presidency, comprised of a president, first vice-president, and second vice-president elected by the judges from among their ranks, forms a separate organ of the court and has responsibility for administration of the Chambers and for overseeing the Registry.[4]

The Rome Statute prescribes a diverse and experienced bench. Judges must be nationals of the states parties, but no two judges may be nationals of the same state.[5]The statute instructs the ASP to balance the bench as to gender, geography, and type of legal system.[6] Consideration is to be given to the need to include "judges with legal expertise on specific issues, including … violence against women or children,"[7] but all judges must have established competence either in criminal law and procedure (known as "List A" judges) or "relevant areas of international law such as international humanitarian law and the law of human rights" (known as "List B" judges).[8] Judges are to be assigned to the different divisions of the court in a manner that achieves a balance of criminal and international law expertise within each division, with trial and pre-trial divisions weighted in favor of judges with criminal trial experience.[9]

Drawing from the experience of other tribunals, Human Rights Watch believes that it is vitally important for the court to have judges with prior experience in criminal proceedings whether as judges, prosecutors, or defense attorneys. Requiring criminal trial experience among the judges of the pre-trial division has already born evident fruit in the confirmation of charges hearing before Pre-Trial Chamber I for Thomas Lubanga, the court's first such hearing. The pre-trial chamber's presiding judge, Judge Claude Jorda, a List A judge and past president of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), balanced a determination to move the proceedings along with flexibility when the parties needed changes to the ordered schedule. Judge Jorda was also able to fairly and efficiently manage what was, at times, a combative defense.

It is premature, however, to make a conclusive assessment of the performance of the Presidency and Chambers. Although the judges of the court have already carried out many substantial tasks since the bench was first constituted in 2003,[10] at this writing, pre-trial proceedings have been completed in only one case, and the court is on the eve of its second confirmation of charges hearing and first trial.[11] This section is limited accordingly to the efforts of the Presidency to promote coordination among the court's organs and to the working-out by the pre-trial division of its innovative mandate.

B. The Presidency: Coordination key to court's success

The responsibilities of the Presidency under the court's statute, rules, and regulations are varied.

Chiefly responsible for court administration,[12] the Presidency has varied duties including constituting pre-trial and trial chambers;[13] replacing judges, designating alternative judges, and making temporary assignments to the three divisions of the Chambers;[14] reviewing certain Registry decisions;[15] concluding agreements on international cooperation;[16] inspecting the court's detention center;[17] and carrying out many of the court's functions in connection with the enforcement of sentences.[18]

The court's first president, Judge PhilippeKirsch of Canada, has additionally assumed a representational role. In numerous private meetings, conferences, seminars, and speeches, Judge Kirsch has effectively worked to promote broader ratification of the Rome Statute and pressed for increased international cooperation and support for the court, including through communications with the ASP focal point on cooperation[19] and with the Committee on Budget and Finance (CBF). The president's work to press for broader ratification of the Rome Statute has had an impact: for example, Mexico ratified the Rome Statute within one year of a personal visit by the president.[20] Human Rights Watch welcomes the example set by the current president and encourages his successor-to be elected early next year-to continue efforts to marshal support for the court through these and other activities.

Consistent with his administrative responsibilities, the president plays a role in improving the court's internal functioning. Early concerns were expressed about division and lack of coordination between the court's organs, including by the CBF in its March 2004 report.[21] In response, the court's organs committed themselves to a "One Court" principle prioritizing coordination on administrative matters while respecting the independence of each organ.[22] Nonetheless, the CBF reiterated its same concerns in its August 2004 review of the court's 2005 draft budget.[23] As Human Rights Watch also observed at the time, the draft budget did not reflect any common approach toward the core functions of the court, and, in fact, the plans of the different organs seemed to duplicate rather than complement one another's work.[24]

Such tensions and duplications may have been inevitable in a developing institution working out complicated issues of policy and practice. In response to these expressions of concern, the president asserted institutional unity of purpose[25] and took concrete steps to improve coordination. These included increasing the frequency of meetings of the Coordination Council[26]-a body composed of the president, prosecutor, and registrar which facilitates administrative coordination[27]-and establishing inter-organ working groups.[28] The working groups now include the Strategic Plan Project Group-which led to the court's 2006 Strategic Plan, discussed below-and the Victims' Participation Working Group.

The president's interventions have gone some way toward increasing dialogue and cooperation, but further efforts are required. In key areas including outreach and field operations where the organs of the court share overlapping responsibilities, a coordinated approach has not always been evident, limiting the court's ability to maximize its impact with affected communities.[29] And a lack of communication between the organs is palpable to external actors who must interact with the court on issues including international cooperation.

While the independence of the prosecutor and the bench should not be compromised, the president should continue his leadership efforts to underscore the importance of internal coordination. Such coordination is essential to meeting the court's unique responsibilities and challenges as an international treaty-based institution of a fundamentally different character to national courts and prosecutions.

In addition, Human Rights Watch encourages the president to exercise continued leadership in the development of a shared vision among the court's organs. The court's 2006 Strategic Plan aims at identifying common institutional goals, guiding budgeting, and increasing states parties' understanding of ICC operations.

Human Rights Watch placed great emphasis on the opportunity presented by the development of a strategic plan. This was, in our view, a chance for the court's organs-deeply immersed in their day-to-day challenges-to step back and project a long-term vision for the court. Instead of reviving the spirit that animated the 1998 Rome conference and setting a course that would ensure the court's impact on those communities affected by crimes within the court's jurisdiction, the Strategic Plan focused primarily on in-court proceedings and court management, with a limited contribution to a shared sense of purpose among the organs.[30]

The court has continued to develop subsidiary strategic documents in key areas, including a prosecutorial strategy, outreach strategy, counsel strategy, and victims' strategy.[31] The development of these documents offers the court continued opportunities to develop and articulate a shared vision. The president can encourage this approach through the Coordination Council. In addition, we note that the Presidency has been provided with a budget to hire a Strategic Planning Coordinator, but this position remains vacant.[32] We encourage the Presidency to make use of this position to consolidate progress on the Strategic Plan.

C. Pre-trial division: Uncharted waters

ICC situations[33] are assigned by the Presidency to a three-judge pre-trial chamber following information received from the prosecutor that a situation has been referred either by a state party or the United Nations Security Council or that the prosecutor intends to request authorization for an investigation.[34] Cases[35]arising from situations remain with the pre-trial chamber through the confirmation of charges hearing which concludes pre-trial proceedings.[36] There are currently three pre-trial chambers: Pre-Trial Chamber I is assigned to the Democratic Republic of Congo and Darfur situations and cases; Pre-Trial Chamber II is assigned to the northern Uganda situation and case; and Pre-Trial Chamber III is assigned to the Central African Republic situation.[37]

The pre-trial division at the ICC is the first for any international criminal justice mechanism; it represents one important innovation of the Rome Statute. At the tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, trial chamber judges have shouldered responsibility for pre-trial court proceedings and, apart from orders of the court required to aid investigation, there is little provision for judicial control during investigations until the prosecutor's presentation of an indictment for confirmation.[38] The Rome Statute, by contrast, establishes a pre-trial division with responsibility not only to carry cases forward to trial by issuing arrest warrants;[39] presiding over a defendant's initial appearance before the court and safeguarding his or her rights;[40] and making rulings on early admissibility challenges;[41] but also with substantial responsibilities even during investigations.

These include issuance of orders as requested by the prosecutor in aid of investigations,[42] oversight of the prosecutor through authorization of investigations initiated by the prosecutor proprio motu,[43] and review of decisions by the prosecutor not to pursue investigations or prosecutions.[44] Such a review may be undertaken at the request of a state or the Security Council,[45] and where a decision not to proceed is based on the prosecutor's determination that it would not be in the "interests of justice," the pre-trial chamber may also review the prosecutor's determination on its own initiative.[46]

Cases brought by the prosecutor are not automatically committed to trial; instead, the pre-trial chamber must first conduct a confirmation of charges hearing to "determine whether there is sufficient evidence to establish substantial grounds to believe that the person committed each of the crimes charged."[47] Charges that are not confirmed by the pre-trial chamber are dropped.[48]

The pre-trial chamber is also responsible alongside the prosecutor for the protection and privacy of victims and witnesses and for the preservation of evidence.[49] At the request of the prosecution, the pre-trial chamber may take measures to ensure the integrity and efficiency of any proceedings in connection with a "unique investigative opportunity," that is, "a unique opportunity to take testimony or a statement from a witness or to examine, collect or test evidence, which may not be available subsequently for purposes of a trial."[50] But where the prosecutor fails to request such measures, the pre-trial chamber-which must be informed by the prosecution of any such investigative opportunity-can also take measures on its own initiative if it concludes that the prosecutor's failure to request measures is unjustified.[51]

Finally, under regulation 48 of the Regulations of the Court, the pre-trial chamber "may request the Prosecutor to provide specific or additional information or documents in his or her possession, or summaries thereof, that the Pre-Trial Chamber considers necessary" to carry out its functions under articles 53(3)(b), 56(3)(a), and 57(3)(c).[52]

The pre-trial chamber harnesses common and civil law traditions to provide oversight of the prosecutor's investigations, set up cases for trial, and conserve judicial resources. Although it is still too early in the court's development to make a comprehensive assessment, the pre-trial chamber's unique responsibilities may help to increase the efficiency of proceedings.

1. First decisions steer ICC's course

The utility of formalized judicial oversight provided by the pre-trial chambers at an early phase of proceedings is already apparent.

For example, the pre-trial chamber has acted to protect the interests of the defense on discrete issues, even prior to the issuance of arrest warrants or to the initial appearances of defendants before the court. In the DRC situation, pursuant to article 56 of the Rome Statute,[53] Pre-Trial Chamber I appointed ad hoc counsel to represent defense interests with regard to forensic examinations requested by the prosecution.[54] In the Darfur situation, Pre-Trial Chamber I appointed ad hoc counsel to represent the interests of the defense when, under rule 103, it invited expert observations on the protection of victims and on the preservation of evidence.[55] Ad hoc counsel of the Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD), discussed in part III.B.1, below, have also been appointed by Chambers to review applications for victims' participation during investigations[56] and to represent any defense interests implicated by notice of proposed activities by the court's Trust Fund for Victims (TFV).[57]

In addition, the pre-trial division has acted to facilitate proceedings by requesting state cooperation pursuant to article 87 of the Rome Statute. Pre-Trial Chamber II, for example, sought information from the government of Uganda as to the impact of an agreement providing for national accountability measures, signed between the government of Uganda and the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), on the chamber's outstanding arrest warrants against LRA commanders.[58] At a time when Uganda's commitment to genuine accountability for crimes committed by the LRA was in question,[59] the chamber's request was a useful reminder of Uganda's obligations under the Rome Statute and prompted an official clarification by the government of the agreement's provisions.[60]

Perhaps most significantly, early decisions by the pre-trial chambers have created a foundation for interpretation of the Rome Statute.

In the DRC situation, Pre-Trial Chamber I provided a first interpretation of certain of the statute's admissibility criteria in issuing its arrest warrant for Thomas Lubanga, the head of the Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC), a prominent militia group accused of committing atrocities during conflict in the northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo district of Ituri. The chamber held that national proceedings that can preempt the court's jurisdiction under article 17(1)(a)-consistent with the Rome Statute's emphasis on the court as "complementary to national criminal jurisdictions"[61]-must encompass "both the person and the conduct which is the subject of the case before the Court."[62] The chamber also gave content to article 17(1)(d), which requires that a case be of "sufficient gravity to justify further action by the Court." The chamber indicated that only the "most senior leaders suspected of being the most responsible" for crimes within the jurisdiction of the ICC should be tried before the court.[63] By providing one interpretation of the boundaries of the ICC's jurisdiction, this decision has shaped perceptions of what cases ought to be investigated by the prosecutor and to be heard by the court.

When Pre-Trial Chamber I subsequently confirmed the charges against Lubanga, it again reached several issues of first impression. For example, under article 61(7), to confirm charges, the pre-trial chamber must, on the basis of a hearing, determine whether "there is sufficient evidence to establish substantial grounds to believe that the person committed each of the crimes charged." Navigating between competing interpretations set forward by the prosecutor, defense, and a victim's legal representative, the chamber determined that the language "substantial grounds to believe" required the prosecutor to bring forward "concrete and tangible proof demonstrating a clear line of reasoning underpinning its specific allegations," and for the chamber to assess that evidence as a whole in making its determination as to whether to send the suspect to trial.[64] The pre-trial chamber also laid out the elements that must be met for a finding of co-perpetration, a basis of individual criminal liability provided for in article 25(3)(a) of the Rome Statute.[65]

As discussed elsewhere more extensively in this report,[66] the Rome Statute provides victims with a novel right of participation in court proceedings that goes beyond the narrow role of prosecution witness.[67] Victims have appeared only as witnesses before the ICTY and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) (and also before the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), established subsequent to the Rome Statute in 2002, although the 2001 law establishing the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) provides for victims' participation more broadly). Working out the details of victims' participation before the ICC, however, has proved to be among the most significant challenges confronted thus far. The pre-trial chambers have expended much effort in setting up and managing systems of victims' participation. Although the Chambers have sometimes differed in their approaches, decisions by Pre-Trial Chambers I and II have granted victims procedural status during investigations, sketched out modalities of victims' participation in situations and cases, enumerated criteria for establishing victim status, and made arrangements for legal assistance to victim participants and applicants (see Part VII.B.1, below).

Decisions of the pre-trial chambers-some of which are discussed in more detail in Human Rights Watch's March 2007 summary of the court's early jurisprudence[68]-may come under review by the appellate division after a final judgment in the case, or, in certain circumstances, through interlocutory appeal.[69] Indeed, the substantial efforts of the pre-trial chamber in working out the scope and modalities of victims' participation have been revised by the trial chamber in one case and are now under review in a number of respects by the appeals division (see Part VII.B, below). Taken together, however, these early decisions provide an important starting point for the difficult task of working out the statute's many novel provisions, and from which subsequent interpretations may be drawn.[70]

2. Navigating intersecting roles

The ICC's blend of common and civil law traditions creates a unique intersection between the roles of the pre-trial division and the prosecutor. While it stops short of creating a true investigative judge in the tradition of civil law, the Rome Statute confers on the pre-trial division powers and functions as described above at the investigation phase and during charging proceedings that would be out of place in a common law system. Efforts by the pre-trial chamber to work out the limits of its role in respect of the prosecutor's mandate has at times led to obvious tension between the two organs, particularly where the pre-trial chamber has taken a proactive approach.

For example, across the situations, the pre-trial chambers' use of various provisions of the court's statute, rules, and regulations to engage the Office of the Prosecutor on the progress and direction of his investigations has met with the prosecutor's strong response.

In the first-ever decision rendered by the pre-trial division in February 2005, Pre-Trial Chamber I decided to convene a status conference-that is, a hearing before the chamber-in the DRC situation.[71] The chamber was apparently concerned that action was required on its part to protect witnesses and to preserve evidence, and it relied on its responsibilities for these activities under article 57(3)(c) to convene the status conference.[72]

The OTP filed a submission in response, terming the pre-trial chamber's intervention unwarranted under the circumstances and unauthorized as a general matter during the investigative stage.[73] The OTP prefaced its submission by noting that "the interplay between Pre-Trial Chamber and Prosecution is a sensitive matter that lies at the heart of the compromises reached in Rome between different legal traditions and values." The OTP described the relationship between the two organs as one in which investigation is "entrusted to the Prosecution" while the pre-trial chamber is permitted "to engage in specific instances of judicial supervision over the Prosecution's investigative activities," and the OTP urged that "this delicate balance between both organs must be preserved at all times in order to honour the Statute, and to enable the Court to function in a fair and efficient matter."[74]

Pre-trial chambers now routinely convene status conferences during investigations. For example, several months later, Pre-Trial Chamber II convened a conference on the status of investigations in the Uganda situation, apparently concerned that the prosecutor may have decided against prosecution of alleged crimes committed by Ugandan government forces on the basis of certain comments of the prosecutor to a meeting of legal advisors of foreign affairs ministries and of his statement at the fourth session of the ASP. The chamber cited its ability under article 53(3)(b) to review on its own initiative decisions of the prosecutor not to proceed with a prosecution under article 53 because it would not be in the "interests of justice,"[75] as well as its specific request in an earlier decision to be informed "promptly" and "in writing" of any such decision.[76] The OTP's public submission in advance of the status conference clarified that no decision had been reached under article 53(3) and that analysis of alleged crimes committed by the Ugandan national army was ongoing.[77]

Although it did not convene a status conference, Pre-Trial Chamber III also relied on its supervisory role under article 53(3) to seek an update from the OTP on its analysis of the situation in the Central African Republic. The situation was referred to the prosecutor by the CAR government on December 22, 2004; two years later no determination had been made by the OTP as to whether to initiate an investigation.[78] Prompted by a request of the CAR government for an update, the pre-trial chamber directed the prosecutor to provide it and the CAR government with a report on the status of his office's analysis.[79] The prosecutor objected, arguing that the pre-trial chamber's reviewing powers under article 53 are not triggered in the absence of a decision by the prosecutor not to proceed with an investigation under article 53(1), but complied with the chamber's request, "reserv[ing] its position on the proper scope of the legal provisions cited by the Chamber in its 30 November 2006 Decision, the division of competences between the OTP and Pre-Trial Chambers and the rights of States who have referred situations to the Court."[80] The prosecutor subsequently announced his decision to open an investigation in the CAR on May 22, 2007.[81]

In the Darfur situation, the prosecutor had adopted a policy of conducting his investigation wholly outside of Darfur, citing security conditions that prohibited the establishment of a system of victim and witness protection there.[82] Pre-Trial Chamber I, again citing its responsibilities for protection under article 57(3)(c) and 68(1), as well as evidence preservation under article 57(3)(c), invited the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Louise Arbour, and the former chairperson of the UN International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur, Sudan, Antonio Cassese, to make rule 103 submissions on the protection of victims and on the preservation of evidence in Darfur.[83]

Both Arbour and Cassese had made clear, public comments about the Darfur investigation, and their submissions disagreed on various grounds with the prosecutor's decision not to conduct his investigations within Darfur.[84] Cassese additionally made a number of specific suggestions about investigative and prosecutorial strategy, including the desirability of locating criminal responsibility up the chain of command in the Sudanese military.[85] In his responses, the prosecutor rebuffed these comments as attempts to influence his strategy.[86]

In addition to these specific actions within individual situations, Pre-Trial Chambers I and II have taken a series of decisions on the modalities of victims' participation during investigations. While these decisions primarily aim at making meaningful rights of victims' participation guaranteed by the Rome Statute, arguably they also reflect an attempt to obtain other independent information in aid of the chamber's substantial responsibilities during investigations. Pre-Trial Chambers I and II have rejected arguments by the OTP that victims' participation in the situation phase jeopardizes the integrity of investigations.[87]

Finally, the pre-trial chambers have offered a restrictive interpretation of some aspects of the prosecutor's authority. First, in issuing arrest warrants in the Uganda situation, Pre-Trial Chamber II rejected the prosecutor's application to transmit requests for the arrest and surrender of the suspects to Uganda and other states. The OTP apparently considered itself to be the organ best situated to obtain cooperation with the requests.[88] Characterizing the warrants and requests as requests for cooperation made by the Chambers, Pre-Trial Chamber II relied in its decision on rule 176(2), which provides that while the OTP is responsible for transmitting requests for cooperation made by the prosecutor, the registrar is responsible for transmitting requests of the Chambers. The Chamber also cited provisions in the court rules and regulations addressed to the registrar's role in transmitting requests for arrest and surrender (regulation 111) and in making arrangements for surrender (rule 184) in support of its ruling.[89] The pre-trial chamber denied the prosecutor leave to appeal its ruling.[90]

Second, on its own initiative, Pre-Trial Chamber I acted to amend before confirming the charges brought by the prosecutor against Thomas Lubanga. The chamber changed the legal characterization of the facts, replacing the prosecutor's charges under article 8(2)(e)(vii) of the Rome Statute with crimes punishable under article 8(2)(b)(xxvi). Although both articles make punishable the conscription, enlistment, and use of child soldiers, the charges brought by the prosecutor require their conscription and enlistment into armed forces or groups in the context of an armed conflict not of an international character. By contrast, the charges substituted by the pre-trial chamber refer to conscription and enlistment into national armed forces in the context of an international armed conflict. The chamber also reduced the temporal scope of the charges.[91]

Human Rights Watch agrees with the chamber that the Ituri conflict should not have been classified by the prosecutor as a non-international (internal) armed conflict: Uganda was an occupying force in Ituri between August 1998 and May 2003.[92] At the same time, however, the Rome Statute does not appear to grant the pre-trial chamber authority to amend charges. Instead, where the pre-trial chamber considers that the "evidence submitted [during a confirmation of charges hearing] appears to establish a different crime within the jurisdiction of the Court," the statute provides for the chamber to adjourn the hearing and to request the prosecutor to consider amending a charge.[93]

The pre-trial chamber denied the prosecutor leave to appeal its decision but noted that the trial chamber may act under regulation 55 to recharacterize the facts.[94] The prosecutor, in fact, sought review of the pre-trial chamber's decision before Trial Chamber I, arguing that either the trial chamber could overturn the pre-trial chamber's decision, or it could proceed to recharacterize the facts under regulation 55. The trial chamber declined the prosecutor's invitation to review the decision of Pre-Trial Chamber I and found that it was premature to take any action under regulation 55. Consequently, the prosecution is faced with taking a case to trial on charges an element of which it has maintained it is not in a position to prove.[95]

This clear division between the prosecutor's authority to bring charges and the pre-trial chamber's authority to commit an individual to trial by confirming those charges is exceptional in a statute which often leaves ambiguous the precise boundaries between the Office of the Prosecutor and the pre-trial division. It is perhaps inevitable that there have been differences of opinion in the working out of these ambiguities. Maximizing the contribution of both bodies to achieving the shared goal of effective investigations conducted with integrity will require continued attention to their relationship and respective roles. The pre-trial division can assist in this process by articulating as fully and as clearly as possible the reasoning and legal basis for the role that it is shaping for itself out of the Rome Statute.

D. Maintaining judicial dialogue key to meeting challenges ahead

In the months and years ahead as trials go forward, the work of the court's Chambers will take on increasing importance within the framework of the ICC and in influencing perceptions of the court's success. With the anticipated start of the court's first trial in the case against Lubanga, the eyes of the international community as well as of those communities affected by crimes within the court's jurisdiction will be trained on the court. Whether its proceedings are fair and expeditious will be the first real test of whether a long-desired permanent, international criminal tribunal can deliver on the promise of justice.

Key benchmarks in assessing the court's future performance will include the Chambers' ability to manage trials efficiently, to safeguard the rights of defendants, and to ensure the safety of court witnesses, as well as its continued working out of the many innovative aspects of the Rome Statute, including victims' participation and the role of the pre-trial division. In meeting these challenges, Human Rights Watch encourages the judges of the court to draw on existing work in the development of court-wide strategies and to benefit from the considerable efforts of the court's organs during these initial years of institution building.

Given the Rome Statute's many innovations, and, in particular, its mix of common and civil law traditions with a bench of judges drawn from these different traditions to match, it is perhaps inevitable that there have been some delays in the court's first proceedings.[96] Although charges were confirmed against Lubanga in January 2007, at this writing, his trial had been suspended, and the court's second confirmation of charges hearing in the case against Germain Katanga and Mathieu Ngudjolo, two other Ituri militia leaders, had been delayed until June 2008.[97]

In addition to delays, the difficult task of developing substantive and procedural law uniquely suited to the ICC is evident from a creeping discord in the interpretations and solutions offered by the court's Chambers to the issues before them. Differences in approach are evident from decisions (and dissents) on fundamental issues including victims' participation,[98] witness protection,[99] and disclosure practices in connection with a defendant's fair trial rights.[100]

To a certain extent, such differences are inevitable: the Rome Statute does not make the decisions of Chambers binding on one another.[101] Persons from the Office of the Prosecutor, Registry units, and counsel (among others), who appear repeatedly before the different Chambers and divisions, will have an interest in litigating and relitigating issues. As the Chambers confront various country situations with unique requirements, different approaches in the application of the law to the facts may be both expected and necessary. Indeed, bringing many legal minds to bear on the novel issues that face the court may build a stronger jurisprudence over time.

While judges should remain free to reach whatever they consider to be the correct legal resolution of the issues in the specific cases before them, it will aid the gradual convergence of the court's jurisprudence on agreed-to procedures and principles if the Chambers are more transparent in their legal reasoning, particularly where departing from that of their colleagues. Some of the court's decisions allude to an ongoing dialogue between them, to a willingness in some instances to follow one another's interpretations,[102] as well as to revisit and revise their interpretations in light of another chamber's subsequent determination.[103] In other decisions, however, Chambers have moved away from prior interpretations without an explanation as to why a different approach has been adopted.[104]

It is far preferable that decisions reflect relevant existing court decisions and, where there is disagreement, the basis for that disagreement. Such a practice would help to bring greater coherence to the court's jurisprudence with time, and, in the meantime, would make the work of the court more accessible to counsel, defendants, and victims.

II. Office of the Prosecutor

A. Overview

The Office of the Prosecutor is the driving engine of the court. The prosecutor's investigative and trial strategy is central to the court's relevance and its impact in the communities most affected. Indeed, the court's ability to bring justice for serious crimes is largely shaped by the prosecutor's selection of situations for investigation and ultimately by the selection of cases for trial. For victims, the prosecutor's selection strategy provides the earliest and most visible measure of how the court will address the suffering that they have endured. The prosecutor's selection of alleged perpetrators and charges also has practical implications for victims: it determines which victims will be eligible to have their voices heard as participants in proceedings.[105] The office's ability to conduct effective investigations and prosecutions is, therefore, of paramount importance.

1. The structure of the Office of the Prosecutor

The current prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, was elected by the Assembly of States Parties and assumed office in June 2003. He was elected for a term of nine years.[106] Beyond the prosecutor and his immediate staff, the Office of the Prosecutor is organized into three main divisions: the Investigation Division; the Prosecution Division; and the Jurisdiction, Complementarity and Cooperation Division (JCCD).

The Investigation Division is responsible for, among other tasks, conducting investigations, analyzing information and evidence collected prior to and during investigations, defining investigation plans, providing investigative support, and, in collaboration with the Victims and Witnesses Unit (VWU) in the Registry,[107] preparing the necessary security plans and protection policies for each investigation to ensure the safety of victims and witnesses involved in the office's investigations.[108] Within the Investigation Division there are four units executing a number of essential functions: Operations Services, Analysis, Gender and Children, and Forensics. The staff of the Investigation Division represents approximately 50 percent of the Office of the Prosecutor overall.[109]

The Prosecution Division, led by the deputy prosecutor for prosecutions, now Fatou Bensouda of Gambia, participates in the determination of the investigative strategy and provides legal advice on issues that arise during the investigation, prepares litigation strategies, and prosecutes cases in court.

The Jurisdiction, Complementarity and Cooperation Division has a number of functions, two of which relate to novel-and central-features of the Rome Statute: the International Criminal Court's broad territorial jurisdiction and its complementary role to national proceedings. The JCCD plays a central role in analyzing referrals and communications in multiple potential situations simultaneously, reflecting the reality of the court's wide-reaching jurisdiction.[110] Further, the JCCD monitors national proceedings involving ICC crimes in situations under examination to advise the prosecutor on whether ICC intervention is appropriate. In addition to these important functions, the JCCD coordinates networks for information sharing and facilitates the cooperation of states and others to carry out the functions of the office.

In addition to these divisions, there are also two sections within the OTP: the Legal Advisory Section and the Services Section. The responsibilities of the Legal Advisory Section include providing legal advice to the prosecutor as needed, facilitating legal research, and providing legal training to office staff. The Services Section handles important administrative functions for the office, such as managing evidence and information, providing oral and written translations, and preparing the office's budget.

Coordinating all of the activities of the office and providing strategic guidance is the Executive Committee, or "Ex-Comm." In addition to providing advice to the prosecutor, the Ex-Comm is responsible for the development and adoption of the strategies, policies, and budget of the office. It is composed of the prosecutor and the heads of the divisions of the office.[111]

In addition, we note that a post of senior gender advisor had been created in the OTP, but this post was never filled. Human Rights Watch believes that recruiting a gender adviser could enhance efforts to mainstream issues relating to gender, including sexual violence crimes, in its prosecutorial strategy. We, therefore, urge the office to fill this vacancy with a qualified candidate.

2. Significant progress in the face of enormous challenges

The challenges facing the ICC prosecutor in investigating war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide cannot be overstated. The ICC's broad geographic jurisdiction means that the prosecutor can act in a number of unrelated country situations simultaneously. Within each country situation, the practical difficulties are considerable. To effectively conduct investigations on the ground and to build cases for trial, staff in the prosecutor's office must become intimately familiar with the history of the respective conflicts, the applicable national criminal law, and relevant cultural norms to communicate with victims and witnesses, among other responsibilities. These investigations require operating in a number of different languages, thus making them even more demanding for the OTP.

A significant complicating factor is the fact that the Office of the Prosecutor executes its mandate in situation countries where the conflict is still ongoing. This reality presents a number of logistical hurdles for staff security in the field and in protecting witnesses, victims, and others at risk because of their interaction with the court. Weaknesses in the infrastructure in the various country situations, such as the lack of reliable and secure transportation or haphazard communications systems, add to these hurdles.

Further, the ICC's lack of police or other enforcement unit means that it must rely on the cooperation of states to effectively investigate and prosecute cases. This cooperation may not always be forthcoming, particularly in conflict-ridden or otherwise unstable situations. In those circumstances, the prosecutor may be subject to enormous pressure from states and intergovernmental actors who, in pursuit of other objectives (such as peace negotiations or peacekeeping deployment), do not always provide the cooperation and support that his office needs to conduct its investigations and to execute its warrants. Where cooperation by national authorities in situation countries is more forthcoming, it must be managed carefully to avoid negative perceptions about the ICC's impartiality or independence.[112]

On this difficult landscape, the prosecutor's office has made considerable progress in its investigations and prosecutions. To date, the office has initiated investigations in four country situations: the Democratic Republic of Congo, northern Uganda, the Darfur region of Sudan and, most recently, the Central African Republic. In Congo, the court has issued arrest warrants against four senior militia members, three of whom are in custody. There are currently four outstanding arrest warrants against senior leaders of the Lord's Resistance Army in northern Uganda.[113] The court has issued two arrest warrants against suspects in Sudan, a sitting minister and a former militia leader, although no arrests have yet been made. Jean-Pierre Bemba, former vice-president of Congo and leader of the country's main opposition party, was arrested in Belgium on the basis of the ICC's arrest warrant against him for crimes allegedly committed in the Central African Republic and transferred to The Hague. In all but two of the above cases, the prosecutor has selected charges that reflect the scope of alleged victimization in the incidents identified. In addition, the prosecutor's office is conducting preliminary examinations pursuant to article 15(2) in several country situations where serious crimes have been or are being committed, such as Côte d'Ivoire, Kenya, Colombia, and Afghanistan.

3. Advancing key policies: The interplay of peace and justice and state cooperation

Recently, the prosecutor's office has made a number of strong policy statements in two significant areas that directly affect the execution of its judicial mandate. The first area involves the prosecutor's interpretation of the "interests of justice" pursuant to article 53 of the Rome Statute. Under this provision, the prosecutor has the discretion not to investigate or prosecute crimes that could otherwise fall under the ICC's jurisdiction if he decides that investigation or prosecution would not be in the "interests of justice." This discretion is subject to pre-trial chamber review.[114] Human Rights Watch believes that this discretion should be interpreted narrowly to avoid practices that could lead to impunity for some of the worst crimes, under the inappropriate claim of preserving stability, peace, and security.[115]

Indeed, discussions on the "interests of justice" are intimately connected to the interface between peace processes and justice for the most serious crimes. The Office of the Prosecutor had initially suggested that it might consider peace and stability as one of the factors underlying article 53.[116] Early in his investigation in Uganda, international actors, including states parties and representatives of humanitarian organizations, as well as Ugandan members of civil society, argued that the prosecutor should invoke article 53 to renounce the prosecution of Lord's Resistance Army leaders since such action would not be in the "interests of justice," conflating justice with concerns of peace and security. By exerting considerable pressure on the prosecutor in this manner, it was hoped that he would cede his role in light of the peace process there.

However, the OTP has since publicly clarified its interpretation of the "interests of justice" in the prosecutor's exercise of his discretion not to investigate or prosecute. Notably, the OTP has stated that it will not consider the broader concerns of international peace and security in the independent pursuit of the prosecutor's judicial mandate.[117] The Rome Statute vests political actors such as the United Nations Security Council with the authority to address these concerns.[118]

The prosecutor has additionally made strong statements that there can be no political compromise on legality and accountability in the context of peace negotiations.[119] This is a significant development and one that we welcome. Indeed, Human Rights Watch believes that the prosecutor's public statements affirming the narrow scope of his discretion under article 53 are consistent with the object and purpose of the Rome Statute and with the requirements of international law.[120] By affirming his judicial mandate in this manner, the prosecutor has sent a strong message that he will not submit to the pressure of those seeking to circumvent the ICC and justice more generally in the face of other competing concerns. Importantly, the prosecutor has stressed publicly the strong conviction underpinning the creation of the ICC: justice for the most serious crimes is a fundamental component of durable peace.[121]

The prosecutor has also made important statements regarding another factor central to the successful execution of his mandate: state cooperation. As noted above, the ICC lacks a police force and, therefore, relies heavily on state cooperation to enforce its orders, including the execution of arrest warrants. The ICC's lack of enforcement capacity underscores how important it is for the prosecutor to press states to fill this crucial function. At the same time, states may not always be immediately willing to provide necessary cooperation for various reasons, including political considerations. This reality means that the ICC-including the prosecutor-must consistently urge states to cooperate with the court to execute its mandate. Indeed, the ICC's decisions and orders are only as effective as their enforcement.

In this regard, the prosecutor has recently taken a more active role in lobbying states and intergovernmental organizations to cooperate with the ICC.[122] For example, the prosecutor has urged states in the UN Security Council to pressure Sudan to arrest the two Sudanese suspects wanted by the ICC.[123] The prosecutor has held meetings with numerous representatives of governments and intergovernmental organizations in New York and has traveled to capitals in Europe and the Middle East to enlist political support and assistance in the execution of the warrants. The ICC prosecutor has also given notice of Sudan's non-cooperation to Pre-Trial Chamber I,[124] which could then submit a request for cooperation to the UN Security Council for enforcement.[125] Raising the profile of cooperation on the international stage helps to engender a sense of urgency-and responsibility-among states, including those that may have suspects in their jurisdiction, to execute the court's orders and decisions.

4. The importance of outreach and communications: An overview

Despite the considerable progress made to date, Human Rights Watch has identified several policy areas of the Office of the Prosecutor's work that raise concerns because of their negative impact on perceptions of the ICC as an independent and impartial institution. As discussed below, while some of these policies may need to be adjusted, in addition, a consistent feature of many of our recommendations is the importance of developing and maintaining an effective outreach and communications strategy in the communities most affected.[126] The prosecutor's selection of cases offers victims their first "benchmark" to assess the ICC's relevance in addressing their experiences. At the same time, for those opposing the court's work, including alleged perpetrators, there is incentive to spread or exploit negative rumors about the work of the prosecutor's office and the court in order to diminish the ICC's impact in affected communities.

Of course, the nature of the court's work, its operation in conflict-ridden or otherwise unstable country situations, and reliance on state cooperation means that to a certain extent, misperceptions and dissatisfaction about the prosecutor's strategy and the court's work are unavoidable. Nonetheless, some of these misunderstandings can be addressed with a robust outreach and communications strategy in the field. Effectively conveying important information about the OTP's work to affected communities, including non-confidential developments in investigations and prosecutions, can help address expectations of what can be achieved and combat misinformation. Ultimately, this will maximize the ICC's credibility among these communities.

B. The Office of the Prosecutor's selection of situations

1. Situation selection: Legal requirements

The ICC's jurisdiction is triggered in one of three ways. First, a state party can refer a "situation"-meaning a specific set of events-to the court where it appears that crimes within the jurisdiction of the court have been committed.[127] The crimes alleged may have been committed on the territory of the government referring the situation to the ICC. The ICC opened investigations in the DRC, Uganda, and the CAR following such "voluntary referrals." A state party can also refer a situation to the ICC involving another state, provided the crimes alleged somehow implicate a state party to the Rome Statute: either the alleged crime took place on the territory of, or the suspected perpetrator is a national of, a state party.[128]

Second, the Security Council can refer to the ICC a situation that it determines presents a "threat to international peace and security" under its Chapter VII mandate of the UN Charter. The authority of the Security Council to do so extends to non-states parties and was used to refer the situation in Darfur, Sudan to the ICC.[129]

Third, the prosecutor can initiate a preliminary examination proprio motu on the territory of a state party on the basis of information about crimes within the ICC's jurisdiction and, if a pre-trial chamber agrees, the prosecutor can open a formal investigation.[130]

Not all situations brought to the prosecutor's attention will be selected for formal investigation, however. Once identified, the OTP must analyze the set of events in question to determine whether they meet the legal requirements under the Rome Statute to proceed.[131] First, there must be a reasonable basis to believe that a crime within the jurisdiction of the court has been or is being committed. Even where an ICC crime or crimes have been committed, the OTP must determine whether they would be admissible. There are two components of admissibility: gravity and complementarity.

The prosecutor has indicated that in selecting situations, his office is guided by the standard of gravity. To assess gravity, his office considers the scale, nature, manner of commission, and impact of the crimes. These criteria are considered jointly, and a gravity determination will be reached on the facts and circumstances of each situation.[132]

The complementarity component involves assessing the national authorities' willingness and ability to investigate the abuses in question for the purposes of prosecution.[133]

From July 2002 until February 2006, the Office of the Prosecutor received 1,732 communications from individuals or groups in at least 103 different countries. Eighty percent of these communications were found to be outside of the court's jurisdiction. The OTP moves potential situations to a phase of "active monitoring" (the "analysis" phase) on the basis of 1) communications that pass through this initial review; 2) referrals; and 3) media and open-source reports.[134] The JCCD plays a central role in analyzing whether a situation meets the admissibility requirements for selection and provides input to the Ex-Comm. The Ex-Comm then makes recommendations to the prosecutor on the selection of situations.

Finally, even if the situation is considered admissible, the prosecutor must still assess whether there are substantial reasons to believe that an investigation would not serve the interests of justice.[135] As discussed earlier, the prosecutor's recent strong policy statements on the interests of justice make clear that considerations of political stability will not interfere with his office's judicial mandate of holding perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide to account. We welcome this development.

2. Managing perceptions in the selection process

In analyzing the information gathered, the prosecutor has outlined the four principles that guide his office in the selection process: independence, impartiality, objectivity, and non-discrimination.[136]The prosecutor has stated that independence means ensuring that the this process "is not influenced by the presumed wishes of any external source, nor the importance of the cooperation of any particular party, nor the quality of cooperation provided."[137] These principles deserve emphasis because the OTP and court's credibility-and the ICC's impact-hinge on their actual and perceived implementation of them.

Explaining the application of these principles requires concerted efforts by the OTP to address deliberately negative distortions. The decision to open an investigation may be subject to questions about the prosecutor's independence and impartiality by those seeking to undermine the court's work. Establishing and consistently applying objective criteria to guide the office's selection process can provide a measure of transparency in this process and can clarify misunderstandings that may otherwise arise. This can help those affected by the OTP's work better understand the office's decisions.

However, while a welcome development, such criteria alone are not sufficient to effectively address criticisms that the ICC is biased. We have identified below examples of the challenges that the ICC prosecutor faces in selecting situations that may have implications for the perceptions of his independence and impartiality.

a. Minimizing the pitfalls of voluntary referrals

The ICC has been seized of the situations in northern Uganda, the DRC, and the CAR on the basis of voluntary referrals.[138] The prosecutor opened an investigation in northern Uganda in July 2004 following the Ugandan government's referral to the ICC in December 2003. The Congolese government referred the alleged ICC crimes committed there in April 2004, and the prosecutor opened an investigation in June 2004. In the CAR, the government referred the crimes committed during the 2002-2003 rebellion in December 2004. In April 2006 the CAR's highest court confirmed that the national justice system was unable to pursue the alleged crimes. The prosecutor opened an investigation there in May 2007.[139]

In selecting situations, the prosecutor has stated his policy of inviting voluntary referrals because it promotes "the likelihood of important cooperation on the ground."[140] Consistent with that policy, the Office of the Prosecutor actively sought the referrals in the DRC and Uganda. Human Rights Watch recognizes that there may be practical advantages to conducting investigations in situations that have been voluntarily referred. These include securing state cooperation and support in gathering evidence in the course of an investigation, as well as in executing arrest warrants. We, therefore, do not oppose their selection or the practice of inviting them where the other criteria under the Rome Statute have been satisfied.However, to ensure compatibility between the prosecutor's independence and his policy of inviting self-referrals, the prosecutor should clearly state "that the possibility of voluntary referral will not be given preference in determining which situations should be selected for investigation."[141]

Selecting situations that have been voluntarily referred may have negative implications for perceptions of the prosecutor's independence and impartiality in affected communities. This likelihood is increased in those country situations where the alleged ICC crimes have been committed along ethnic or political lines and implicate actors in the referring government (voluntary referral should not deflect attention from alleged government crimes, for example). There is a substantial risk that any collaboration between the referring government and the ICC in these polarized country situations will be perceived negatively by those affected by the crimes. The court must be sensitive to this reality and should actively seek to address the negative misperceptions that may follow a decision to open an investigation. Ultimately, the OTP should ensure investigation of state actors in the context of voluntary referrals to determine if there is sufficient evidence to do prosecute and the other requirements are satisfied. We note that the only arrest warrants issued to date in voluntary referral situations are for rebel leaders.

Our field research in Uganda illustrates the dangers of failing to anticipate and adequately address such misperceptions. The Ugandan government voluntarily referred the situation in northern Uganda to the ICC for the purpose of investigating abuses committed by the LRA, an insurgent group at war with the government. The prosecutor announced the government's referral to the ICC at a joint press conference with President Yoweri Museveni. This public appearance fed perceptions of the ICC as a "tool" being manipulated by Museveni to serve his political interests.

Since the referral, we note that the prosecutor has made some efforts to combat these damaging perceptions. For example, the prosecutor's decision to open an investigation references the "situation in [n]orthern Uganda," thus clarifying that the scope of the ICC's investigation is not limited to alleged perpetrators from one group.[142] He has also stressed the impartiality of his investigation and has made an effort to contextualize the decision to issue arrest warrants against LRA leaders.[143] In more recent statements, the prosecutor has emphasized that his office continues to seek information about crimes allegedly committed by the government army, the Uganda Peoples' Defence Force (UPDF).[144] We welcome such efforts.

However, we wish to underscore the importance of adequately conveying these messages to the communities most affected by the crimes in the conflict. Our research reveals shortcomings in this regard. Representatives of civil society and community-based organizations that we interviewed in Kampala and northern Uganda in March 2007 consistently criticized the ICC's failure to either investigate and prosecute UPDF abuses or to explain why this was not being done.[145] As a result, the prosecutor's work in Uganda is perceived by many of those in affected communities as one-sided and biased. Sources point out that despite additional outreach efforts to affected communities in northern Uganda overall, more could be done to clarify and better convey the key messages about the ICC's approach to alleged crimes by Ugandan army personnel.[146]

Of course, no amount of explanation will eliminate all of the criticism from those in polarized societies. Also, we can appreciate that the focus and substance of investigations are confidential and cannot be shared with the public. Nonetheless, there are a number of objective factors that the prosecutor's office could better and more frequently explain to local communities. For instance, the prosecutor's office could improve efforts to explain its policy regarding the gravity threshold in selecting cases, as well as the limits imposed by its temporal jurisdiction in pursuing cases against alleged UPDF perpetrators. This is significant as it is believed that some of the most serious abuses allegedly implicating Ugandan forces were committed prior to 2002. Providing clear explanations would go a long way to better inform affected communities.

b. Affirming prosecutorial independence: The proprio motu authority

The significant disadvantages associated with pursuing situations that have been voluntarily referred provide a good illustration of the kinds of challenges to the prosecutor's independence that can arise. These challenges also highlight the benefits of the prosecutor's use of other avenues in the selection of situations, such as his proprio motu power, when possible. Under this authority, the prosecutor can actively monitor a country situation on his own initiative to gather information in order to determine whether to pursue an investigation there.[147] With the authorization of a pre-trial chamber, this information can lead to the opening of an investigation.[148]The exercise of the proprio motu authority-literally "on his own initiative"-is a vital route for the prosecutor to exercise his independence.

To date, this prosecutor has not used this authority in the selection process. The prosecutor made reference to its use in selecting the situation in the DRC at the second session of the Assembly of States Parties in 2003, but instead decided to encourage the Congolese authorities to refer the situation there voluntarily.[149] He has recently started acknowledging that this authority is a "critical aspect of his office's independence."[150] More recently, he emphasized his proprio motu powers under the Rome Statute as conferring on him the status of a "new autonomous actor on the international scene."[151] We urge the prosecutor to use this authority where appropriate.

We note that in the decision to open an investigation in the CAR, the prosecutor stated that his office continues to monitor violence and crimes being committed in the northern areas of the country bordering Chad and Sudan. Human Rights Watch's recent research there indicates that government troops-particularly those in the presidential guard-have carried out hundreds of unlawful killings and have burned thousands of homes during the counterinsurgency campaign there. This campaign has forced tens of thousands to flee their villages.[152] The office's analysis of the crimes allegedly committed by the referring government will likely be closely scrutinized by affected communities and others to ensure the consistent application of the prosecutor's own gravity criteria.

It is unclear whether the terms of the initial referral, which relates to crimes committed during the 2002-2003 rebellion, would encompass these newer alleged crimes. If not and if the more recent crimes are considered admissible, we urge the prosecutor to consider using his proprio motu power to open an investigation. The majority of these crimes were allegedly committed by forces affiliated with the government that voluntarily referred crimes to the ICC.

c. Addressing the criticism that the ICC is a "court for Africa"

As noted above, the prosecutor is currently investigating crimes in four situations in Africa. The gravity of the crimes in each of these situations cannot be disputed. Nevertheless, the court's exclusive focus on Africa at present has led to criticism among some African states and ICC observers that the continent is the court's main target,[153] with the prosecution strategy being intentionally geographically-based.[154] Underlying this criticism is the perception that the ICC is a European court designed to try African perpetrators because they are believed to be politically and economically "weak." Among these critics, the ICC is perceived as a biased institution.

Assessing the validity of these criticisms requires examining whether the facts support them. The ICC can only investigate crimes that implicate a state party to the Rome Statute unless there is a referral by the Security Council or a non-state party submits itself to the ICC's jurisdiction. This reality is reflected in the current situations under investigation: three of the four ICC country situations were voluntarily referred, while the fourth situation, Darfur, was referred to the court by the UN Security Council. In addition, the ICC's temporal jurisdiction restricts the Office of the Prosecutor from investigating crimes that occurred before July 1, 2002. This has the effect of excluding many situations from the court's jurisdiction. Even where it has temporal jurisdiction, the crimes at issue must still meet the admissibility requirements-gravity and complementarity-under the Rome Statute.