"As If They Fell From the Sky"

Counterinsurgency, Rights Violations, and Rampant Impunity in Ingushetia

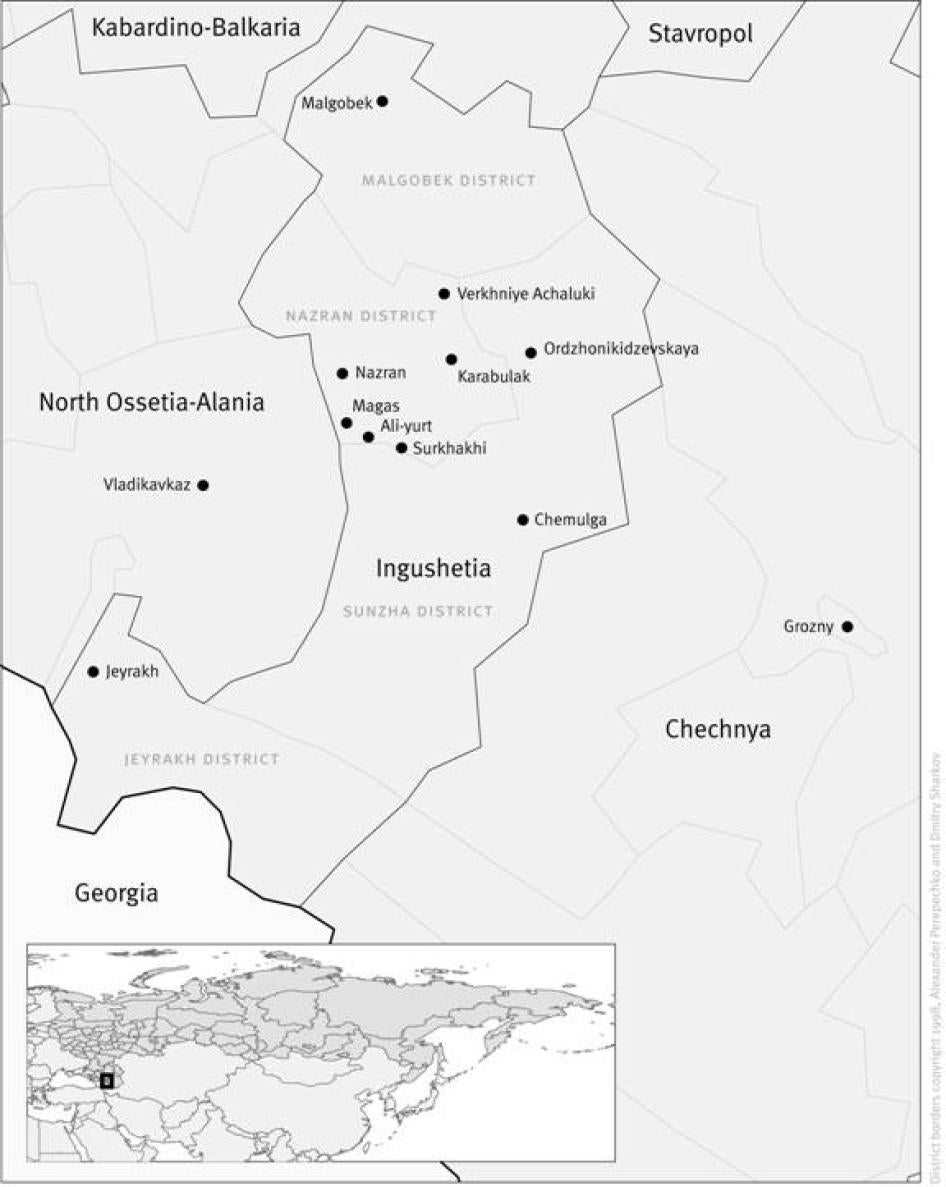

Map of Region

I. Summary

It really hurts! Supposedly, neither the leadership of the republic nor the leadership of the Russian military knows who did it. Here are men in uniforms and armed to the teeth coming into the village, abusing masses of people, and leaving. And then no one is able to explain what happened. As if they fell from the sky.

-An Ingushetia resident seriously assaulted, along with his pregnant wife and his neighbors, during a July 28, 2007 counterterrorism sweep operation at the village of Ali-Yurt

The Chechnya armed conflict affected stability and the security of communities across the North Caucasus region of Russia, and continues to do so. In Ingushetia, the republic into which Chechnya's conflict overflowed, the grave conflict dynamics of its larger neighbor have arisen. For the past four years Russia has been fighting several militant groups in Ingushetia, which have a loose agenda to unseat the Ingush government, evict federal security and military forces based in the region, and promote Islamic rule in the North Caucasus. Beginning in summer 2007, insurgents' attacks on public officials, law enforcement and security personnel, and civilians rose sharply.

Human Rights Watch condemns attacks on civilians and recognizes that the Russian government has a duty to pursue the perpetrators, prevent attacks, and bring those responsible to account. Attacks on civilians, public officials, and police and security forces are serious crimes. Russia, like any government, has a legitimate interest in investigating and prosecuting such crimes and an obligation to do so while respecting Russian and international human rights law. Regrettably, Russia is failing to respect or to adhere to these laws. Law enforcement and security forces involved in counterinsurgency have committed dozens of extrajudicial executions, summary and arbitrary detentions, and acts of torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

These practices evoke, albeit on a far smaller scale, the thousands of enforced disappearances, killings, and acts of torture that plagued Chechnya for more than a decade. They are antagonizing local residents and serve to further destabilize the situation in Ingushetia and more widely in the North Caucasus.

In order to prevent Ingushetia from turning into the full-blown human rights crisis that has characterized Chechnya, prompt and effective measures must be taken by the Russian government to end these human rights violations and hold accountable their perpetrators.

This report, based on extensive field research, documents these human rights violations and describes the legal and political contexts in which they have occurred.

A leading Russian human rights nongovernmental organization (NGO), the Memorial Human Rights Center (Memorial)-which has an office in Ingushetia-estimates that in 2007 alone, security personnel were responsible for up to 40 extrajudicial executions of local residents in counterinsurgency operations. This report documents eight. The youngest victim, six-year-old Rakhim Amriev, was killed in a raid on his parents' home, where security forces believed an alleged insurgent was hiding. An investigation into his death is ongoing. That investigation is exceptional, however, and can be explained only by Amriev's young age, which precluded the authorities from alleging his involvement in insurgency. In most cases, the authorities do not investigate killings of alleged insurgents. In summer 2007, for example, security forces opened fire on Islam Belokiev one afternoon at a car market; they then surrounded him, barred medical help from reaching him, and let him slowly bleed to death. Charges of membership in an illegal armed group and attempt at the life of law-enforcement personnel were filed against him posthumously, and his killing was never investigated.

Law enforcement also forcibly and arbitrarily detain, without a warrant, those suspected of insurgency. While officials acknowledge that suspected insurgents have been detained, detainees are kept in incommunicado detention and their relatives are not informed of their whereabouts. This practice is referred to in the region as "abductions." According to Memorial, 29 people were thus "abducted" in 2007; three of those individuals subsequently disappeared, while one was killed. Typically, those detained by security and law-enforcement services are young males suspected of involvement with illegal armed groups and terrorism. Three categories of young men are especially vulnerable to such detention: individuals related to or acquainted with presumed insurgents or terrorism suspects; those previously detained and whose names are in police and security forces' databases, regardless of whether they were charged with or cleared of any alleged wrongdoing; and strictly observant Muslims. Many of those so detained are also tortured, or disappear.

For example, in September 2007 security forces took Murad Bogatyrev from his home without a warrant. Several hours later, his family watched as his naked body, which was covered in bruises, was carried out of a local police station. Police told them Bogatyrev died of a heart attack. Despite credible evidence, including a forensic medical report registering bodily harm and photographs taken by relatives, the investigation into his death (a case categorized as "abuse of office") has to date not yielded any indictments or prosecutions. One month before Bogatyrev's death,

30-year-old Ibragim Gazdiev "disappeared" after he was detained by security forces in August 2007. Several months prior, Gazdiev's home had been searched by the Federal Security Service (FSB) looking for evidence of collaboration with militants. Nothing was found. The investigation into Gazdiev's disappearance has not yielded any results, and he is missing to this day.

Abduction-style detentions and killings in Ingushetia often happen during "special operations," which generally follow the pattern of sweeps and targeted raids seen in earlier years in Chechnya. Groups of armed personnel-security services, local police and federal Ministry of Internal Affairs troops-arrive in a given area, often wearing masks and riding in armored personnel carriers and other vehicles that in many cases lack license plates. They surround a neighborhood or an entire village and check peoples' dwellings. Because they do not identify themselves, residents can refer to them only as "servicemen." They do not show official warrants or provide the residents with any explanation for the operations. In the four cases of special operations documented in this report, they forced entry into homes, beat some of the residents, and damaged their property.

News of abductions, "disappearances," killings, and abusive special operations spread quickly among Ingushetia's population of 300,000. People in Ingushetia voiced their distress at these violations-and the government's failure to hold anyone accountable-in a series of relatively small, largely spontaneous public protests. With the president of Ingushetia, Murat Zyazikov, consistently referring to the situation in the republic as normal and stable, by autumn 2007 local authorities did their utmost to prevent further protests from happening and to silence media coverage. Local officials refused to grant protest organizers permission for two rallies, which were subsequently violently dispersed.

In a striking move to intimidate independent observers, 16 human rights advocates and journalists were variously abducted, detained, and expelled from Ingushetia by security forces as they attempted to monitor two planned public rallies in November 2007 and January 2008.

Counterinsurgency operations in Ingushetia are regulated by Russia's federal counterterrorism legislation. This legislation allows broad restrictions to be placed on fundamental rights and freedoms with no judicial or parliamentary oversight. It gives special provision for the detention of individuals suspected of terrorism for 30 days without charge. It also allows the security services to establish a "counterterrorism operations regime," during which the authorities may search homes without warrants and ban public assemblies and the work of the press. The security services may impose these restrictions for any duration of time, in any area they determine as relevant, and without having to demonstrate that the restrictions on rights are proportionate to the threat of terrorism. The law also sets out no terms for proportionality on the use of lethal force in counterterrorism activities.

The counterterrorism operations regime is problematic, but often not invoked in Ingushetia. Far more problematic, in practice, is that law enforcement and security forces have every reason to believe they may act with impunity when carrying out any operation related to counterterrorism or counterinsurgency. Law enforcement and security forces responsible for human rights violations in Ingushetia are not brought to justice. If criminal cases into those abuses are opened at all, the prosecutors fail to mount meaningful investigations. Such investigations in most cases cannot even determine which agency-the police, the military, the FSB-is responsible for killings and other violations.

Many of those who have sought justice as well as eyewitnesses to the abuses have been subjected to verbal and physical threats. The failure of justice in Ingushetia is evidenced by the rising number of applications to the European Court of Human Rights by Ingushetia residents.

II. Recommendations

To the Government of the Russian Federation

Stop human rights violations in counterinsurgency operations

- Immediately stop the practice of extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, abductions, and other abuses perpetrated in particular by security services, military, and law enforcement agencies.

- Inform all detainees immediately of the grounds of detention and any charges against them. Inform the families of detained persons of their detention, and the reason for and location of the detention. Allow families of detained persons regular contact with detainees.

- Require all personnel on search-and-seizure operations to identify themselves and provide their military, law enforcement, or security branch affiliation.

Ensure accountability and transparency

- Ensure meaningful accountability mechanisms to bring perpetrators of serious violations to justice and ensure transparency regarding investigations and/or prosecutions undertaken, including their outcome.

- Conduct thorough and independent investigation of all killings that have taken place and may take place in special operations. In doing so, adhere to the UN Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-Legal, Arbitrary and Summary Execution.

- Foster a favorable climate for journalists and human rights defenders to do their work in the region.

- Put an end to disproportionate restrictions on freedom of assembly in Ingushetia and stop harassment of organizers of public protests.

Legal reform

- Amend the counterterrorism legislation to:

oEnsure everyone detained is promptly charged with an offense or released;

oEstablish clear limits on the duration and territorial boundaries of a counterterrorism operation within which the security services may restrict fundamental rights and freedoms;

oEstablish principles of proportionality for imposing restrictions on fundamental rights and freedoms during counterterrorism operations;

oEnsure that lethal force is only authorized when absolutely necessary and that all security and law enforcement officers permitted to use lethal force are adequately trained to understand and respect the standards on when lethal force may be used.

- Sign and ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances.

Ensure access to the region for international monitors

- The Russian government should recognize and commit to respecting the terms of reference of the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, whom the Russian government issued a long-awaited invitation in 2006. The special rapporteur should be allowed to meet in private with detainees held on accusations of involvement in insurgency in Ingushetia and should have unfettered access to detention facilities in the North Caucasus where these detainees are held.[1]

- Issue an invitation to the UN Working Group on enforced and involuntary disappearances, which has a request pending with the Russian government.

- Issue an invitation to the special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, in full agreement with the mandate's terms of reference.

- Issue an invitation to the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on the situation of human rights defenders, in full agreement with the mandate's terms of reference.

To Russia's International Partners

- Governments, in particular those of European Union member states and the United States, should advance the recommendations contained in this report in multilateral forums and in their bilateral dialogues with the Russian government.

- Call for the Russian government to provide access to international monitors to the region, including the UN special rapporteur on torture and the special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions.

- Urge Russia to fully implement rulings handed down by the European Court of Human Rights regarding violations in Chechnya, an instrumental step for preventing such violations from being perpetrated more widely in the North Caucasus.

To the Council of Europe

- The Parliamentary Assembly should put the developing human rights crisis in Ingushetia on its agendawith a view to adoptinga resolution acknowledging the deteriorating situation in Ingushetia and calling on Russia to stop human rights abuses in Ingushetia, hold the perpetrators accountable, and ensure that any law enforcement operations conducted in Ingushetia conform with Russian and international law.

- The Secretary General should call on the Russian prosecutor's office to fully investigate abuses committed by military, security, and police forces in Ingushetia, including extrajudicial executions, abductions, enforced disappearances, and torture. The Secretary General should insist that these investigations fully comply with the standards for investigations into alleged human rights violations developed in the case law of the European Court of Human Rights.

- The Commissioner for Human Rights should visit Ingushetia to address the deteriorating human rights situation in the republic.

- The Committee for the Prevention of Torture, which visited Ingushetia in the spring of 2007, should put repeat periodic visits to the region on its agenda.

- All relevant Council of Europe bodies should urge Russia to amend the 2006 Counterterrorism law to bring it into full conformity with Council of Europe standards.

A family home after an FSB raid in the village of Chemulga, Ingushetia. 2007 Human Rights Watch

III. Methodology

This report is based primarily on field research conducted in December 2007 during a Human Rights Watch mission to Ingushetia. In the course of the mission, Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 53 individuals, mostly victims of human rights violations and their relatives. One interview with a victim was conducted prior to the mission, in October 2007, when a Human Rights Watch consultant was traveling in the region on another assignment. Additionally, some interviews were done in Moscow or by phone from Moscow. In order to reflect the official position of the Ingushetia authorities Human Rights Watch researchers also traveled to Ingushetia in May 2008 and met with the president, the prosecutor, the minister of internal affairs, the deputy head of parliament, and the ombudsman of the republic.[2] A request to meet with the head of the Federal Security Service's Ingushetia branch was not accommodated.

All interviews were conducted in Russian by Human Rights Watch researchers who are native speakers of Russian.

In addition, Human Rights Watch examined official documents, including search reports, prosecutor's office decrees, forensic medical reports, public statements by federal and Ingush officials, analytical reports published by Russian human rights groups, and media accounts.

IV. Background: How the Conflict in Ingushetia Has Unfolded

Note on Ingushetia[3]

Ingushetia, the smallest of Russia's republics in the North Caucasus, covers an area of 3,210 square kilometers (1,240 square miles), and has a population of approximately 300,000.[4] With Chechnya to the east, North Ossetia to the north and west, and Georgia along its southern border, Ingushetia has been a frontier land between Chechnya and its neighbors to the west.[5] The population of Ingushetia is relatively young; the average age is approximately 29 years. Its unemployment rate, which in July 2007 officially exceeded 32 percent, is one of the highest in Russia.[6]

Although the Ingush and Chechen cultures are distinct, their extensive contact has kept their cultural and religious developments inextricably linked. Until the 16th century, the Ingush inhabited the middle and highland areas of the Assa Valley, but throughout the following two centuries, driven by climate change and repeated Russian incursions, they migrated from the Caucasus Mountains into the plains, where further association with the Chechen people continued.[7]

During the Soviet era, the two national provinces were merged (from 1917-1924, 1934-1944 and 1957-1991), divided as autonomous provinces (1924-34), and, for a time, even legally abolished (1944-56) when both nations suffered a mass deportation on the orders of Joseph Stalin. The forced deportations during World War II claimed the lives of one-quarter to, perhaps, even one-half of their populations. When Chechnya declared its independence in 1991, Ingushetia formed a republic within the Russian Federation.[8]

Ingush and Chechens are also close linguistically, religiously, and socially. Although the two languages are formally distinct, they are sufficiently similar that Chechens and Ingush can easily understand each other; fluency in Russian is also widespread within both nations. The Ingush and Chechen converted to Islam in the 17th to early 19th centuries; both follow one of the two traditional Sufi orders: the Qadiri and the Naqshbandi.[9] At the end of the 20th century, with an influx of foreign Muslim preachers into the region, a small minority of the Ingush and Chechens adopted Salafite Islam.[10]

Ancient mountain traditions still play a significant role in the life of both nations. They share a similar social organization in the form of tribal and clan divisions. The latter still acts as a significant determinant of one's social relationships and conduct.[11]

In November 1992, Ingush and the neighboring Ossetians clashed over the disputed Prigorodny district, which both ethnic groups claimed as their own but which is officially a part of North Ossetia. The conflict brought about the destruction of a total of 2,728 Ingush and 848 Ossetian homes, and drove between 43,000 and 64,000 people from their homes.[12] While the majority of the displaced Ossetians have since returned to their homes, successive decrees to return the Ingush displaced persons to North Ossetia have met with little success. At this writing, 10,000 displaced persons from Prigorodny district continue to live in Ingushetia.[13]

Crisis Spillover to Crisis Nexus: The Unfolding Conflict in Ingushetia

1999: Ingushetia and the second Chechen War

From the beginning of the second Chechen conflict in autumn 1999, Ingushetia hosted thousands of internally displaced persons who fled Chechnya. According to official figures, between 1999 and 2003 as many as 308,000 displaced persons were registered at one point or another in Ingushetia.[14] The vast majority of them eventually returned to Chechnya or left for other regions. During periods of the most intensive fighting, however, the displaced almost outnumbered the population of Ingushetia.

Chechen internally displaced persons enjoyed relative safety and stability in Ingushetia until 2002, when Murat Zyazikov, a former Federal Security Service (FSB) general who had strong Kremlin support, succeeded Ruslan Aushev as president.[15] Shortly after Zyazikov's election in April 2002, federal authorities adopted a detailed plan for returns to Chechnya. Zyazikov implemented the plan, which resulted in massive returns, some of them forced, of displaced people to Chechnya and the final closure in June 2004 of tent camps housing thousands of them.[16] At this writing, about 38,000 people displaced from Chechnya continue to live in Ingushetia, in private dwellings, dormitories, and makeshift housing.[17]

Human rights and security dynamics in Ingushetia 1999-2003

When the second Chechen war started, international scrutiny was focused on Chechnya. Compared to its neighbor, Ingushetia appeared a peaceful haven, and was the subject of international attention almost entirely in connection with Chechen refugee issues. By the end of 2003, attention started to shift to a rise in attacks on Ingush police and security forces.

Federal and Ingush authorities repeatedly claimed that rebel fighters pushed out of Chechnya found safe refuge in settlements and tent camps, hiding among the large numbers of internally displaced people.[18] Nonetheless, the Russian military presence was almost non-existent in Ingushetia, and the activity of Chechen rebels mostly imperceptible.[19] The first large clash between federal forces and Chechen rebels in Ingushetia took place in September 2002, when almost 200 Chechen fighters entered Ingushetia, shot down a Russian helicopter, and killed at least 17 soldiers.[20]

The security situation in Ingushetia deteriorated in late 2002, with numerous attacks on Ingush law enforcement personnel. According to an Ingush government official, at least 11 Ingush policemen were shot dead in 2002 "in criminal incidents related to Chechnya in one way or another."[21]

Also in 2002, security and law enforcement agents in Ingushetia carried out abduction-style detentions and enforced disappearances, which had become hallmarks of the Chechnya conflict.[22] At this time, these violations affected only Chechen displaced person, and therefore, outside observers perceived them as an extension of the human rights crisis in Chechnya.[23]

After the October 2002 "Nord-Ost" hostage crisis at the Dubrovka Theater in Moscow,[24] the federal government deployed more troops to Ingushetia, an indication of Russia's decision to broaden the scope of its "counterterrorism operation" in the North Caucasus region. While previously sweep operations were very rare in Ingushetia, by summer 2003 they became frequent. In June 2003 alone, seven were carried out in displaced persons' settlements and Ingush villages.[25]

2003: Sweep operations and insurgent attacks

The operations followed the pattern of sweep operations or targeted raids seen in Chechnya: large groups of armed personnel, often arriving in armored personnel carriers and other military vehicles without license plates, surrounded a neighborhood or an entire village and conducted either sweep or random checks at peoples' dwellings. The armed personnel, who were in most cases masked, did not identify themselves or provide the residents with any explanation for the operations. During the operations, many civilians were subjected to beatings and other forms of ill-treatment; some houses were looted.[26]

The year 2003 also saw a marked rise in the number of abductions. Human rights defenders documented 52 abduction-style detentions, of which 41 of the victims were Chechen displaced persons.[27] The authorities demonstrated unwillingness to acknowledge that the abuses even took place, let alone to investigate them and punish the security forces responsible for them. The military, security, and law enforcement agencies participating in the Ingushetia operations enjoyed complete impunity, which had long been a characteristic of the Chechnya conflict.[28]

Mid-2004: Severe deterioration

Insurgent raid on Nazran and Karabulak

The human rights situation and security situation in Ingushetia deteriorated sharply in 2004. On the evening of June 21, a group of insurgents stormed the towns of Nazran and Karabulak, attacked law enforcement facilities, and exerted control over both towns until early the next morning.[29] The insurgents were led by the infamous Chechen rebel commander Shamil Basaev, who had been the mastermind behind some of the worst terrorist attacks in Russia's history. Basaev's group, which led the raid, numbered several hundred, including ethnic Chechen, but also many Ingush fighters.[30]

The casualties in the ranks of Ingush law enforcement personnel were overwhelming. The insurgents, dressed in camouflage uniforms and wearing masks, looked no different from military and security servicemen. They stopped people in the streets and road intersections, asking for their identification documents, and killed all those who had law enforcement personnel ID. According to official data from June 23, 2004, insurgents had killed 24 members of the Ingushetia police force, 12 officers of the republican FSB branch, and 16 policemen temporarily deployed to Ingushetia from other regions of Russia.[31] The acting minister of internal affairs of Ingushetia, his deputy, and the Nazran municipal and district prosecutors also lost their lives during the raids.[32]

The insurgents inflicted significant civilian casualties too, particularly as they killed not only security and law enforcement personnel but generally those who had official ID, including, for example, the head of the Ingushetia postal service, a staff member of the republican Ministry of Agriculture, and a staff member of the republican Ministry of Transport. On June 23, the overall number of killed civilians was quoted as 44.[33]

According to the official website of Ingushetia, the final total of the casualties from the armed raid was 98 killed and 104 wounded, including law enforcement and security personnel, officials, and civilians.[34]

For a small republic like Ingushetia such losses were staggering. Most local residents were also shocked by the fact that many of the members of Basaev's group were Ingush. In the wake of Basaev's raid, the public at large rallied around the government and urged the authorities to take prompt and strong measures to prevent such attacks from happening again. Thus, the intensification of counterinsurgency operations as of mid-2004 initially enjoyed widespread public support.[35]

Ensuing counterinsurgency operations

Sweep operations were immediately carried out in areas heavily populated by Chechen displaced persons. No large-scale abuses occurred, and most of the people detained during those operations were promptly released. However, the sweeps were followed by targeted raids, in which individuals suspected of involvement with the insurgents were summarily and arbitrarily detained by federal or local security and law enforcement servicemen. Some of the detained individuals "disappeared." Others were tortured and forced to confess to involvement in insurgent groups and attacks, including, but not limited to, the raid on Nazran.[36]

Counterinsurgency operations and human rights violations intensified in the wake of the September 2004 hostage-taking atrocity in Beslan, North Ossetia.[37]

According to the leading Russian human rights NGO, Memorial, 75 people were "abducted" in Ingushetia by law enforcement and security agencies in 2004, half of them residents of Ingushetia.[38]Eventually, one of those individuals was found dead, 23 disappeared, and the others were either released after protracted interrogations and torture or appeared in remand prisons. Many of the latter were held in the remand prison of Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia, having confessed to grave crimes and incriminated other residents of Ingushetia, who would then suffer the same fate.[39]Memorial documented many of these cases and asserts that during counterinsurgency operations security and law enforcement servicemen did not identify themselves or explain the reasons behind the raids. They would seize individuals allegedly involved with an illegal armed group; their families were not made aware of their respective fates or whereabouts. Those detained were tortured and subjected to psychological pressure in both legal and illegal places of detention. They were generally denied access to independent legal counsel, and were forced to sign confessions and other incriminating statements.[40]

Security forces targeted strictly observant Muslims in particular, assuming their religiosity would make them likely insurgents. As described below, the insurgency in Ingushetia has a broad Islamic agenda, and a large proportion of insurgents adhered to strict interpretations of Islam. According to numerous reports, law enforcement agencies in the North Caucasus were tasked with putting together lists of so-called Wahhabis, the term being misused to describe any followers of Salafite Islam and more broadly to brand alleged supporters of insurgency and terrorism. Those on the list would generally become the first obvious victims of counterinsurgency operations.[41]

2006 and beyond: insurgents' agenda and operations in Ingushetia, and the counterinsurgency

The Basaev raid in 2004 clearly demonstrated that insurgent and rebel groups operating in Ingushetia included Ingush residents. Subsequent insurgent attacks in the region also relied on major involvement of Ingush fighters.[42] Insurgent attacks intensified in Ingushetia in the wake of the post-Beslan counterterrorism operations. These attacks targeted law enforcement personnel, government officials, and local religious leaders who spoke against Salafite Islam.

As for the counterinsurgency response and related human rights abuses, Memorial's research findings for 2006 evidence a marked shift from abduction-style detentions to extrajudicial executions: 15 civilians were abducted and about 40 were killed in counterinsurgency operations.[43]

2007: Dramatic increase in insurgent attacks on servicemen and officials

2007 saw a dramatic rise in insurgent activity. The beginning of the year was marked by assassination attempts on the mufti of Ingushetia and two other religious leaders, and an attack on a military convoy in the part of North Ossetia's Prigorodny district populated by Ingush. The attack on President Zyazikov's family residence in the village of Barsuki on July 16, the alleged shelling of President Zyazikov's motorcade on July 21,as well as the attack on the FSB building and the presidential palace in Magas on July 27 received particularly broad media coverage.[44] While in 2006 there were 37 attacks on law enforcement personnel that resulted in deaths of 15 police officers and four civilians,[45] in 2007, according to statistics provided to Human Rights Watch by Ingushetia Minister of Internal Affairs Musa Medov, 86 attacks were made on members of law enforcement agencies.[46] The resultant casualty toll, according to Prosecutor of Ingushetia Yuri Turygin, was 65 servicemen killed in 2007.[47]Memorial reported more than 50 insurgent attacks on law enforcement and military officers and civilian servicemen in the period June through September alone.[48] Among those killed were the deputy head of Plievo district administration, a republican civil servant, four Ingush policemen, and an FSB colonel who had investigated the abductions of Ingush and Chechens in North Ossetia.

Interior Minister Medov's statistics show another 28 attacks on members of law enforcement agencies during the first three months of 2008.[49]

Attacks on non-Ingush

A particularly disturbing development in insurgent activity was a wave of killings of non-Ingush residents of Ingushetia (hereafter referred to as Russian-speakers of various ethnic backgrounds).

The first series of such attacks were carried out between January and March 2006 and, according to Memorial, three people were killed and three others wounded. Additionally, six Russian-speaking families had petrol bombs thrown into or at their homes.[50] Another series of attacks were perpetrated in 2007 and reached a shocking level in the months of July to November, when 24 Russian-speaking residents were killed allegedly by insurgents. Among them were ethnic Russians, Roma, and Koreans. The majority of the victims were long-term residents of Ingushetia who enjoyed respect in the local community. Relatives of some of the victims fled Ingushetia in fear of further attacks.[51]

A series of killings in summer 2007 of Russian-speaking families sparked public outrage in Ingushetia. A Russian school teacher, Ludmilla Terekhina, and her children Marina and Vadim, were killed in the village of Ordzhonikidzevskaya on July 16. Two days later, an improvised mine exploded by their gravesite at their funeral, wounding 10 people. On August 31 another Russian teacher, Vera Draganchuk lost her family to another such attack: her husband Anatoly and her sons Mikhail and Denis were killed in the town of Karabulak soon after .[52] The authorities pledged to bring the perpetrators of these crimes to justice without delay. However, subsequent operations by law enforcement and security forces resulted in extrajudicial executions of local residents suspected of involvement in the killings of Terekhina and her children and the family-members of Draganchuk. This also caused a major public outcry and contributed to rising tensions in the republic.[53]

Many residents of Ingushetia refuse to believe that the killings of Russian-speakers in Ingushetia were perpetrated by the rebels and attribute them to the security services. That in itself testifies to the growing antagonism towards the FSB, as a result of the accumulating abusive operations.[54] The involvement of insurgents, however, appears very plausible in light of a statement by one of the leading commanders of the insurgents published by the key rebel website, CaucasusCenter, in May 2006. The statement asserted that the militants had recently carried out a series of successful operations, "including against Russians in the territory of the North Caucasus, and Ingushetia in particular" because the insurgency leadership "now view Russians as military colonists, with all relevant consequences."[55] The same concept was reinforced by the chief insurgent leader, Doku Umarov, in a statement on November 21, 2007.[56]

2007-08 counterinsurgency operations

In attempts to suppress the growing insurgency, a "special preventative operation" began in Ingushetia as of July 25, 2007: the local police force was put on permanent alert and 2,500 troops of Russia's Ministry of Internal Affairs were deployed to the region along with several dozen armored personnel carriers (APCs). At this writing, the operation is still ongoing.[57] However, it has proved to be ineffective under the circumstances, as the specially deployed servicemen soon became additional targets for the insurgents. Generally, from July to early autumn 2007, insurgent attacks were occurring several times per week and sometimes on a daily basis.[58] This frequency of rebel attacks decreased a little with the arrival of colder weather but rose to the same level in the spring of 2008.[59] Insurgents' attacks continue to plague Ingushetia as of writing of this report.[60]

Human rights violations perpetrated during the ongoing "special preventative operation," as well as prior operations in 2007, are documented in this report, and have clearly contributed to a further growth in tensions. According to Memorial, in 2007 alone 29 civilians were "abducted" and approximately 40 killed by military, security, and police officials.[61]

Parliamentary acknowledgment of abuses during counterinsurgency operations

Ingushetia's parliament has acknowledged the abusive nature of counterterrorism efforts in Ingushetia. A Temporary Parliamentary Commission was formed in Ingushetia to analyze the human rights situation and released a report in February 2008, stressing that the lawless comportment by law enforcement and security largely contributed to the overall deterioration of the situation in the republic. The commission noted, in particular, that from 2004 through 2007, 149 individuals were subjected to extrajudicial executions in Ingushetia. The commission also stated this figure was based on information it received from law enforcement bodies.[62]

General Characteristics of Insurgents in Ingushetia, Links to Chechnya

The number of insurgents in Ingushetia is unclear. Law enforcement agencies and the media have made strikingly low estimates ranging from 50 to 100 militants in the territory of the republic. While little is known about the insurgents' structure and agenda, it appears inseparable from the insurgency in Chechnya.

According to media reports, three major rebel groups operate in Ingushetia-Barakat ("Bliss"), Nazran, and Taliban-and are joined under the command of Akhmed Yevloev, also known as Commander Magas.[63] According to CaucasusCenter, "Magas"[64] initially received his mandate directly from Doku Umarov,[65] a prominent Chechen commander and former president of the unrecognized Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. Umarov dissolved Ichkeria in October 2007 and proclaimed himself "Emir of the Caucasus Emirates."[66] "Magas's" appointment by Umarov can be viewed,inter alia, as corroboration of the widespread opinion that the insurgents in the North Caucasus have a centralized command, the so-called Majlisul Shura (council of field commanders) led by Umarov.

In his October 2007 statement, Umarov specifically condemned "all names that the faithless [non-Muslims] use to divide Muslims," that is any ethnic or territorial division of the Caucasus.[67] It therefore appears that after several years of symbiosis between Islamist and separatist tendencies within the armed groups, the Chechen separatist project lost to the militant Islamist approach.[68]

One expert on the insurgency emphasized that the insurgency movement in the North Caucasus is of a "clearly Jihadist" nature.[69] Among new recruits there may be individuals initially unfamiliar with strict interpretations of Islam and motivated by revenge for family members killed by security services, personal experiences of abduction and torture, etc. However, once such individuals join the rebel forces they become indoctrinated in strict and militant Islam.[70] The insurgents' proclaimed long-term goal is to create an Islamic state in the Caucasus.[71] Their short-term agenda is far from distinct, and can be generally described as destabilizing the situation in the North Caucasus region and ousting the authorities.

Perhaps in an effort to gain public support, since 2004 the insurgents have been generally avoiding killing Ingush or otherwise Muslim civilians in Ingushetia.[72] In response to the insurgents' attacks on law enforcement servicemen and public officials, the law enforcement and security forces carry out counterinsurgency operations that result in the killing and abduction of local residents. This only makes Ingushetia's residents believe the insurgents are, at minimum, no worse than the authorities.[73]

The dramatic rise in insurgent attacks in Ingushetia may be explained largely by Ramzan Kadyrov's grip on Chechnya and his successful strategy of recruiting insurgents into his security forces in exchange for personal security guarantees. This has made it increasingly difficult for the insurgents to operate in Chechnya. One result is that by 2007 their efforts became largely focused on neighboring Ingushetia, whose authorities are too weak to effectively exert control over the situation and whose residents have been so frustrated by violent and lawless actions by security and law enforcement agencies that the base of support for insurgency on the ground is gradually growing.[74]

V. Domestic Legal Framework for Counterterrorism

Counterinsurgency operations in Ingushetia are governed by Russia's federal counterterrorism legislation. This legislation allows fundamental rights and freedoms to be severely restricted or suspended during counterterrorism operations, and allows the security services to determine-without judicial oversight-the circumstances under which such restrictions will apply and the extent to which they should be applicable. The legislation extends the amount of time a person suspected of participation in illegal armed groups and involvement in terrorist crimes may be held in custody before being charged. It also allows for searches of homes without warrants, use of lethal force in case of unspecified necessity, and bans on public assemblies and the work of the press as possible elements of counterterrorism operations. The FSB, which is put in the lead of counterterrorism efforts, may invoke these restrictions for any duration of time, in any area it determines relevant, and without having to demonstrate that the restrictions on rights are proportionate to the threat of terrorism.

2006 Norms

Russia's counterterrorism framework includes a federal counterterrorism law and a range of other laws, including criminal, administrative, and criminal procedure norms.[75] In 2006 this framework was updated essentially to incorporate a range of counterterrorism practices that had evolved in Chechnya and were expedient for security and law enforcement personnel.[76]

The cornerstone of these legislative changes was the adoption in May 2006 of Federal Law No. 35 on Counteracting Terrorism,[77] which replaced the 1998 Law on Fighting Terrorism.[78] The new law expanded on the old definition of terrorism-attempts to influence decisions by state authorities by means of inciting fear among the public and/or committing other unlawful and violent actions[79]-to include propagating terrorism, disseminating materials that call for engaging in terrorist activity or include justifications of terrorism,[80] and carrying out "informational and other[81] collaboration" with terrorists and in planning of terrorist attacks.[82] These provisions have had a distinctly negative impact on freedom of expression, particularly with regard to media coverage of terrorist attacks. Their vague formulation leaves them open to broad and arbitrary interpretation and therefore to a breach of Russia's obligations to respect freedom of expression as guaranteed under both article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights and article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).[83]

The new law also redefines the concept of a "counterterrorism operations regime." Whilst the old law provided for territorial limitations on a counterterrorism operation zone (a specific part of a territory, a building or vehicle and the territory adjacent to it, etc), under the 2006 law counterterrorism operations are bound neither by territory nor duration. Both are defined by the head of the counterterrorism operative headquarters in the region where the operation is conducted.[84]

Restrictions on rights in counterterrorism operations

Under the 2006 law, during counterterrorism operations security services and law enforcement may conduct document checks and personal searches and impose limits on the free movement of people and vehicles.

Also, in 2004 the criminal procedure code was amended to allow individuals detained on allegations of terrorism to be held for 30 days without being charged, as opposed to 10 days applicable in all other situations.[85]

The 2006 law also allows counterterrorism security personnel, without a judicial warrant, to have unhindered access to people's homes, conduct random surveillance of communications (telephone, internet, etc.), and suspend communication services.[86] These provisions permit serious interference with the right to privacy, and to the home and correspondence, as protected by article 8 of the European Convention, article 17 of the ICCPR, and article 23 of the Russian Constitution (which additionally stipulates that restrictions on these rights can be imposed solely on the basis of a judicial sanction).

The new law places significant restraints on freedom of expression, particularly freedom of the press, by enabling the authorities to deny journalists and independent reporters access to the counterterrorism operations zone. As described below in this report, the authorities have invoked this provision to prevent journalists from reporting on developments in Ingushetia. [87]

The above restrictions are similar to those invoked under a state of emergency. But in contrast to a state of emergency, counterterrorist operations are not subject to either parliamentary or international control.[88]

Lack of specific preconditions for counterterrorism operations

The law does not specify preconditions that must exist for launching a counterterrorism operation. It only stipulates that a "counterterrorism operation is conducted to repress a terrorist attack if there is no way to do so by other means."[89]Article 12.2 gives local security services the right to launch counterterrorism operations in their respective territories and exclusive rights and responsibility to determine the targets, timing, scope, and subjects of the operation. Article 9 provides for large-scale use of military forces in counterterrorism operations.[90]

The overly broad definition of terrorism, combined with the wide powers security services have to define counterterrorism operations and restrict rights, have prompted concern that the law can be misused to suppress dissent or to advance the interests of the governing authorities even in the absence of a genuine threat of terrorism. As noted earlier, for instance, the Ingush government invoked the counterterrorism regime to justify banning a protest rally.

Authorized use of lethal force

The law sets out no standards of proportionality for the use of lethal force by law enforcement and security servicemen. A June 2007 implementing decree stipulates that weapons and military equipment in counterterrorism operations can be used during a detention "if the detention cannot be carried out by other means."[91] Before an officer is authorized to use his weapon, he is required to declare his intention to do so, unless such a warning would "endanger life" or is "impossible." However, no guidance is provided on the circumstances in which such an eventuality may occur.

At the same time, according to authorities in Ingushetia, in 2007 and 2008 a counterterrorism operation regime has been in force in Ingushetia on only two occasions: in July 2007 to conduct a sweep in the village of Ali-Yurt as a follow up to the insurgents' attack on Magas,[92] and in January 2008 to prevent a protest rally which, according to police intelligence, created a threat of terrorist attacks.[93] Numerous "special operations" conducted in the territory of the republic are not classified as counterterrorism operations but are deemed to be regular law enforcement operations aimed at preventing crimes of a terrorist nature, involving for example the arrest of alleged members of illegal armed groups.[94] However, large armed units are frequently deployed during those operations and resort to the use of lethal force.[95] The prosecutor of Ingushetia, Yuri Turygin, told Human Rights Watch that law enforcement personnel "use lethal force if they're under threat." Turygin also maintained that the prosecutor's office views "threat to personnel" as a key criterion in identifying a potential terrorist attack.[96]

Structure of Counterterrorism Operations

As described below in this report, a variety of agencies can be involved in counter-terrorism operations. Article 15.3 of the counterterrorism law enumerates the agencies that may be deployed in such operations, including the FSB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Emergency Situations, Fire Department, Water Safety Department, and other executive personnel.

The law provides little clarity about the chain of command over counterterrorism operations but puts the FSB firmly in control of all aspects of counterterrorism operations. The Federal Operative Headquarters (whose head is appointed by the FSB director) on the federal level[97] and the local operative headquarters on the regional level, controlled ex officio by heads of local branches of the FSB,[98] remain the key decision-making and implementing agencies with full control over concrete operations in the relevant territories. The operative headquarters develop the operation's plan, ensure coordination between different enforcement agencies involved, and are responsible for the actual conduct of the operation.[99]The operative headquarters chief, in turn, has overall control of the execution of the operation[100] and determines which personnel need to be deployed[101] and which resources are needed for the operation. A federal National Counterterrorism Committee (chaired by the FSB director) and similar regional commissions (chaired by regional governors) were created by President Putin's decree to coordinate the work aimed at preventing terrorism and minimizing consequences of terrorist attacks in general but they are not tasked with overseeing specific operations.[102]

Ingushetia's president, Murat Zyazikov, told Human Rights Watch that the republican Counterterrorism Commission under his leadership holds meetings "on a regular basis," discusses strategies aimed at preventing and countering terrorist activity "but does not plan specific operations, as this is the task of the professionals," namely the FSB. Ingushetia's minister of internal affairs, who is also the deputy head of the republican Counterterrorism Commission, said that an operative headquarters meeting chaired by the head of the FSB discusses available intelligence and determines whether that intelligence warrants a counterterrorism operation, and the republican Counterterrorism Commission follows the headquarters guidance.[103]

Other Laws Amended by Counterterrorism Legislation

Other laws amended to accommodate the needs of the counterterrorism operations include the Federal Law on the Mass Media and the Federal Law on the Federal Security Service.[104]

The amendments to the Law on Mass Media ban the media from publicly justifying terrorism.[105] They also stipulate that "the procedure for collection of information by journalists in the territory of a counterterrorism operation shall be defined by the head of the counterterrorism operation."[106] Under the amendments, mass media outlets covering counterterrorism operations are forbidden from disseminating information on special means, techniques, and tactics used in connection with the operation.[107] Likewise, mass media cannot be used "for dissemination of materials containing public incitement to terrorist activity, of providing public justification of terrorism, or of other extremist materials."[108]

The amendments to the Law on the Federal Security Service provide for the conduct of military operations with the aim of "obtaining information about events or actions, which create a terrorist threat" and "identifying persons connected with the preparation and conduct of a terrorist attack."[109]In practice, this accounts for the heavily militarized sweeps and targeted raids of houses by security services.

VI. Extrajudicial Executions

Memorial estimates that security personnel were responsible for up to 40 killings of civilians in counterinsurgency operations in Ingushetia between January and December 2007.[110]In this report Human Rights Watch documented eight such cases of unlawful killings by law enforcement officials, and one case of attempted unlawful killing, in Ingushetia in 2007,[111] and identified a pattern of extrajudicial executions there. In all but one of those eight cases, security services justified the killing by claiming the victim had been violently resisting arrest. Immediately after the killing, the authorities would bring criminal charges against the deceased of attempting to kill law enforcement agents, membership in an illegal armed group, and illegal weapons possession. The investigation of those charges was then promptly closed in light of the suspect's death.

Witnesses to the killings to whom Human Rights Watch spoke generally denied government allegations that the victims were armed or used violence. However, most witnesses dare not provide official testimony, fearing repercussions from security services. Human Rights Watch is not in a position to confirm these witness accounts or assess the government's claims. But in none of these cases did the authorities launch effective investigations into whether security forces' use of lethal force was justified. Also, Human Rights Watch is not aware of any forensic or ballistic examination that would have substantiated the government's claims.

Extrajudicial executions constitute a clear violation of the right to life, a fundamental right forming part of Russia's international human rights obligations. The deprivation of life by state authorities is considered a matter of utmost gravity.[112] As a consequence, circumstances in which deprivation of life may be justified must be strictly construed.[113]The European Court of Human Rights has consistently held that it will subject deprivations of life to the most careful scrutiny, particularly where deliberate lethal force has been used.[114] The force used must be strictly proportionate to the attainment of the legitimate aims listed in article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights.[115]European Court judgments have stressed that detained individuals are considered to be in a particularly vulnerable position. For this reason, the authorities' obligation to account for the treatment of a detained person is particularly strict in cases where that individual dies. The burden of proof may in such cases be considered to rest on the authorities to provide a plausible explanation.[116] The Court has applied these principles to several cases involving extrajudicial executions in Chechnya, in which it has found a violation of the right to life.[117]

The government's failure to investigate extrajudicial killings in Ingushetia is also a violation of its international obligations to investigate suspected killings and to hold those responsible criminally accountable.[118] Families of the deceased must be ensured access to effective remedies.[119] An investigation will only be considered effective if it is independent and capable of leading to a determination of whether the use of force was or was not justified as well as to the identification and punishment of those responsible.[120] The European Court of Human Rights has in a number of cases held Russia responsible for failure to conduct effective investigations into extrajudicial executions in Chechnya.[121]

Killing of Islam Belokiev

Islam Belokiev and his parents bought and sold spare car parts at a market in Nazran. On August 30, 2007, security forces killed 20-year-old Islam Belokiev at the market. According to witnesses, at around Belokiev was heading for the market exit when several men in a car parked near the market called out to him. They opened fire as soon as he turned in their direction.

Witnesses saw the wounded Belokiev fall to the ground and then be immediately surrounded by armed plainclothes security personnel, who prevented anyone from approaching the scene.[122] Soon other uniformed security personnel in masks, armored vests, and helmets appeared, and were joined by armed servicemen who arrived in an armored personnel carrier. Witnesses report that Belokiev was still alive and moving feebly, but the armed personnel neither gave him medical assistance nor allowed anyone to come to his aid.By the time medical professionals and officials from the prosecutor's office were allowed to enter the market, Belokiev had bled to death.

According to one eyewitness, Aslan N. (not his real name) one of the servicemen planted a gun and a grenade on Belokiev.[123] Aslan N. recounted for Human Rights Watch the entire incident,[124]

There were gun shots and everyone ran from all directions to see [what was happening] Those people were in masks and camouflage. The boy was killed like a quail He did not die right away. For 40 minutes or so, they [the servicemen] were standing around him, they closed everything off People were crowding here and they could see this whole picture. We had automatic guns pointed at us. No one could come near. The boy was thrashing about for a while. Everyone was afraid to do anything because of those guns. Someone wanted to take a picture with his cell phone, but one armed man screamed obscenities at him, took the phone away, and broke it

On the following day, August 31, three family-members of ethnic Russian teacher Vera Draganchuk were shot dead in the nearby town of Karabulak (see Chapter IV, above). In comments to the media, Zinaida Tomova, first assistant to the prosecutor of Ingushetia, alleged that Draganchuk's husband and their two sons were killed in retaliation for the killing of Belokiev. Tomova confirmed that Belokiev "was killed during the operation aimed at his detention" and that the operation was carried out by staff members of the Anti-TerroristCenter of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and personnel of the FSB branch in Ingushetia. She also asserted that Belokiev opened fire when these servicemen attempted to seize him.[125]

All of the witnesses to Belokiev's killing interviewed by Human Rights Watch insist that he was not armed and showed no resistance. Murad C. (not his real name), an acquaintance of Belokiev working at the same market, also claimed that one of the servicemen insisted there were explosives hidden in Belokiev's stall. However, a colleague of Belokiev immediately opened the stall for the police to examine, and they did not find anything.

Murad C. stressed that Belokiev could not have fired at the attackers: "How could he do any such thing? There were three to four gun shots, and it was evident that one man was shooting from the same weapon. And there was a burst of submachine gun fire. He [Belokiev] definitely did not have a submachine gun!" Murad C. gave a statement with this and other relevant details to the prosecutor's office.

It is unclear what weight, if any, the prosecutor's office gave that witness account. It is certain, however, that the circumstances of Islam Belokiev's killing were not effectively investigated.

Human Rights Watch is not in a position to determine whether Islam Belokiev was armed. Forensic evidence, if collected, could have determined whether, in fact, Belokiev had fired a weapon, but it is unclear whether any effort was made to collect such evidence. At the same time, based on witness accounts, the security services clearly acted with excessive and unlawful force by shooting at Belokiev without appropriate warning and when there was no immediate danger to any other individual.This was compounded by the actions of the security forces in letting him bleed to death.

Compounding a lack of proactive investigation is an environment in which it is not conducive for witnesses to come forward with evidence. Most of the witnesses to the killing were too frightened to give evidence to the prosecutor's office. Among those who refrained from testifying was Aslan N., who explained his behavior, and that of many others, in his interview to Human Rights Watch: "Everyone saw this scene. But if I tell about it and then go home, they will take me away in one hour without investigation or trial, and I'll just disappear. And why would I bring this on myself? I have a family. This is how things stand. Absolute lawlessness."[126]

Killing of Apti Dalakov

On September 2, 2007, 22-year-old Apti Dalakov and several friends were walking out of a video games club on Oskanov Street in Karabulak when two Gazel minibuses without license plates stopped next to them. After up to 30 armed servicemen jumped out of the vans and aimed their weapons at them. The young men tried to run away. The servicemen immediately started chasing them.

The incident was witnessed by many bystanders who later told the Dalakovs that Apti Dalakov crossed Jabagiev Street and rushed into the yard of a former kindergarden, called Ryabinka.[127] Two of the servicemen caught up with him and started shooting. Dalakov was wounded and fell. One of the servicemen, who was dressed in civilian clothes and masked his face with his own shirt, fired at Dalakov several times and finished him off with a shot to the head before placing a small object in his hand.

Local police and riot police arrived at the scene of the killing, searched the unknown servicemen, identified them as Federal Security Service (FSB) officers, and took them to the Karabulak police department. However, high-level officials of the FSB's Ingushetia branch arrived shortly thereafter and demanded that police release the servicemen and return their weapons and ammunition, including the shells collected at the site of the crime.

As a riot police officer told Human Rights Watch,[128]

We were told on the radio that Karabulak was being attacked, and that there was shooting next to the kindergarten, close to School No. 1. When we were approaching, we heard the sounds of automatic gunfire. We got there and saw the bloodied body of a young guy and around 12 armed men standing next to it. Four or five of them were in plainclothes. The others were in masks and camouflage uniforms. Some appeared to be Ingush, some were Russian. There also seemed to be Chechens and Ossetians. We did not know who they were ... The dead guy had no gun or anything. We later discovered that he had a used grenade in his fist, but the locals were saying they saw how that grenade was planted.

So, anyway, we had to seize those armed [individuals]. They resisted, and yelled obscenities, and threatened us, but we were greater in number, so they had to yield in the end. Several of them had FSB IDs. We took them to the police department and then-I was not there at this point-but they were basically rescued by their higher-in-command. And in the end, we are getting blamed for this.[129]

The Southern Federal District's prosecutor's office launched charges of abuse of office against the police who detained the security officials. In addition, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ingushetia was reprimanded by the then-presidential plenipotentiary in the Southern Federal District, Dmitry Kozak, for having interfered with an FSB operation.[130]When asked by Human Rights Watch to comment on this situation, Ingushetia's prosecutor, Yuri Turygin, said that he could not provide any information as the investigation was ongoing.[131]

As early as September 2, prosecutorial authorities opened a posthumous criminal case against Apti Dalakov for an attempt on the life of law enforcement personnel[132] and illegal possession of weapons,[133] and then closed the case, as Dalakov was dead. Having received relevant notification from the prosecutor's office,[134] Apti Dalakov's family members submitted a counter-complaint asking for an effective investigation into the circumstances of his killing to be launched and for the perpetrators to be brought to justice.[135] The complaint specifically refers to witnesses who confirmed that Apti Dalakov was unarmed and his actions were nonviolent. However, to this writing, no inquiry into this complaint has been initiated.

Apti Dalakov's killing was also officially declared to be connected with the murder of Vera Draganchuk's family (making it apparently a third link in a chain of killing and reprisal killing beginning with Islam Belokiev). On September 3 the FSB's Ingushetia branch explained to the media, including all-Russian television, that Apti Dalakov and his friend Iles Dolgiev, who was detained by security personnel on the day of Dalakov's killing, were both "Wahhabis" and active members of "the Karabulak bandit underground." The FSB claimed the two young men were responsible for the murder of the teacher's family members, as well as for a range of other grave crimes.[136] However, Dolgiev was released from custody and cleared of all allegations,[137] providing strong grounds to believe that Dalakov was killed entirely arbitrarily.

Killing of Rakhim Amriev, age 6

The killing that created the greatest resonance in Ingushetia and caused vocal public protests was that of a six-year-old boy named Rakhim Amriev. Security personnel killed him and wounded his mother in the course of an operation allegedly aimed at detaining a distant relative of his parents.

Early in the morning of November 9, 2007, up to 100 military and security personnel arrived in the village of Chemulga, in the south of Ingushetia, in three APCs and numerous other vehicles. They closed off several streets, including the street where the Amriev family lived.

The Amrievs were awoken by the noise at around and heard a command on a loudspeaker: "Women and children, come out!" By the time the four children and their parents approached the door, three armed servicemen broke into their house and immediately opened fire. Rakhim Amriev was instantly killed; his mother, Raisa, was wounded in her arm. The family, including the wounded woman, was then forced to leave the house barefoot and in their nightclothes. The servicemen started shooting and throwing grenades at the empty house.

Ramzan Amriev, Rakhim's father, gave Human Rights Watch the following account of the events,[138]

As soon as they [servicemen] broke in, they started shooting sporadically. All hell broke loose I was trying to cover one of my sons with my right arm, and another one with my left arm. I heard my wife screaming, and then suddenly I saw blood on Rakhim's forehead. They hit him right in the forehead, and he just died before I noticed.

We were forced to leave the house. The servicemen did not let me take my son's body. He was left there all alone For some time, they kept us on the street next to our neighbors' gates, and then several servicemen took me back to our house. They said, "You only have a second to pick up the boy, you son of a bitch!" So I went, wrapped Rakhim in a blanket, so that the other kids wouldn't see, and carried him out. They told me to go away, but I still saw how they were throwing grenades at the house. They even drove an APC into the wall.

With Rakhim's body in his arms, Ramzan Amriev joined his family members and neighbors who were all gathered on a small hill close to the Amrievs' house. The half-dressed men, women, and children[139] were forced to stand outside in the cold for several hours, until approximately

One of those people, Malika Khatsieva, described the special operation to Human Rights Watch,[140]

When we heard the order for women and children to come out, it was in the morning. My family went into the yard, and we were all forced to lie flat on the ground. We lay like that for 10 to 15 minutes. The kids were undressed, and the ground was so cold. Then, we were told to walk to the back end of the village where all their APCs and other vehicles stood. Women and kids just walked surrounded by servicemen, but men were made to crawl in the mud. We were all blue from cold, but they wouldn't let us go back and get some clothes, not even for the kids. Raisa [Amrieva] was also brought there. She was crying, "They killed my child!" Her hand was bleeding badly but they did not even call a doctor.We saw from a distance how grenades were thrown at Ramzan [Amriev]'s house, how they shot at the walls, and how that APC rode right into the house. Children were so frightened; they still cannot get over this.

At , officials from the civilian and military prosecutor's office arrived in Chemulga. They took Ramzan Amriev into his house, showed him an automatic gun lying close to the doorstep and asked if the gun belonged to him. Amriev said that he had never seen that weapon. Later, prosecutor's office had his fingerprints taken but did not mentioned the gun again.

The day after Rakhim Amriev's murder, the military prosecutor's office in the village of Tkoitskaya[141] opened a criminal case "on the death of a child during an operation." The investigator noted in the investigation file that the personnel of the FSB's Ingushetia branch conducted the special operation in Chemulga in order to detain R. Makhauri, a suspect in several grave crimes, including organizing an illegal armed group.[142] Though Makhauri is a distant relative of Ramzan Amriev, the Amrievs insist that they have not seen him in the past six years.

Ingushetia's prosecutor, Yuri Turygin, told Human Rights Watch in May 2008 that he considered the scale of the operation at the Amriev household and the use of weapons justified by the fact that Makhauri is suspected of 11 particularly grave insurgency-related crimes, including killings of ethnic Russians. He also said that the unintentional killing of the six-year-old boy was being duly investigated and the investigation was attempting to identify the serviceman from whose weapon the fatal shot had been fired.[143] Apparently, the authorities have made no attempt to hold accountable any other servicemen involved in the operation, or the FSB officer who commanded it.

So despite the fact that it is officially established that those responsible for the killing of Ramzan Amriev are from the FSB, they have not even been individually identified, let alone held accountable. Human Rights Watch can only speculate why it has not been possible in the six months since the crime to identify by which weapon Rakhim Amriev was killed and who was using the weapon at the time.

Adding to the doubts about the seriousness of the investigation, Ramzan Amriev's cousin Aslan Amriev, who used to work in the administration of Chemulga, told us that he lost his job because of his refusal to provide false testimony regarding the special operation in the village,[144]

Two prosecutorial officials approached me; one was in plainclothes, the other one in grey camouflaged uniform. They asked, "Who was shooting from the [Amrievs'] house?" I said, "No one!" Then, the man in camouflage said, "I'll take you outside now and will empty the cartridge of my gun into you No, I'll disappear you!" But I still refused to lie. So, when they were leaving, the officer in military uniform asked, "Where do you work?" I said that I worked at the local administration as a manager. Then, he promised, "You won't be working there any more." And on December 14 of this year I was fired. I worked there for eight years, and everything was fine. They must've forced the administration to fire me because of this case.

Killing of Said-Magomed Galaev and Ruslan Galaev

Two brothers, Said-Magomed Galaev (born 1983) and Ruslan Galaev (born 1986) were killed on September 27, 2007, in the village of Sagopshi, as a result of a special operation conducted by federal and local policemen.

According to their mother, Fasiman, and their elder brother, Tagir, the operation started at when the family was sleeping. Said-Magomed's wife, Madina, was awakened by a noise outside the house. She woke Said-Magomed and asked him to see what was happening. He went to the window near the front door, looked outside and yelled, "There are servicemen at the door!" The other family members were awakened by his cry and immediately heard gunshots outside.[145]

About a dozen of the servicemen broke into the house and continued shooting. Fasiman, dazed by the shooting, was still sitting on her bed in the room that she shared with her youngest son, 11-year-old Said-Akhmet, when Ruslan, already wounded, stumbled into the room and fell on the floor close to the bed. He was followed by several servicemen who continued to fire their guns. Several bullets hit the walls, one of them flying just above the head of Said Akhmet, who was crouching by the corner of a couch. Said-Magomed was killed near the door to his bedroom.[146]

The servicemen took Fasiman, Madina, Tagir, and Said-Akhmet into the yard without allowing them to get dressed. The Galaevs saw them throw several grenades into the house. The attackers had Tagir take the bodies of his brothers outside and ordered the crying women and the boy to sit by the corpses.

The Galaevs' yard was surrounded by two APCs and a dozen armored UAZ vans. The servicemen numbered about 100.Several of them seized Tagir and dragged him from the yard, beating him on the way. They refused to tell Fasiman where her elder son was being taken.

While the Galaevs were kept outside, the servicemen searched their house without a warrant and with no witnesses present. When they finished the search, they came out with a bag containing a grenade, two guns, a submachine gun, and some ammunition they allegedly found inside. The Galaevs insist that they had no weapons in the house.[147]

Fasiman Galaeva told Human Rights Watch,[148]

When Ruslan fell on the floor by my bed I thought-this boy of mine is dead, but the other two are still alive, and the little one is here with me. Then another son was killed. I pleaded with them, "You have already killed two of my children, please leave me those who still remain, but they took Tagir away without explanation. My daughter-in-law, my little son, and I were forced to sit on the ground with automatic guns pointed at us. I asked the servicemen, "Let me go. I need to bury my boys!" And they just brushed me off: "You might as well sit here-your sons won't go anywhere." So I sat next to their bodies and watched the blood flow out of them. One of the servicemen was nice to me-he allowed me to hold Ruslan's hand. I could feel it getting colder and colder under my fingers and I was praying that Tagir was still among the living."

Later that day, Fasiman and Madina were taken to the Malgobek district police department, where they found Tagir. Each member of the Galaev family was questioned separately by an investigator from the prosecutor's office. The investigator wanted to know where the weapons in the house came from and which illegal armed groups Ruslan and Said-Magomed were involved with. Tagir Galaev was also asked specifically where he and his brothers were on the night of September 8 when military unit #3733 stationed in the town of Malgobek was attacked by insurgents.

That afternoon relatives and neighbors of the Galaev family gathered at the police department to demand their release. Late in the evening the family was finally allowed to return home.

Tagir Galaev told Human Rights Watch,[149]

They took me away at in the morning and released me after On the way to the police station the servicemen beat my legs and head. They were yelling that I was an insurgent and a Wahhabi. The investigator also accused me of attacking a military unit along with my brothers. I explained that on that night they were all at our relatives' house at a large prayer gathering, and many people could confirm it. If not for the pressure from our relatives, who organized a picket by the police building, they would not have let me go.

A posthumous criminal case was initiated against Ruslan and Said-Magomed for alleged participation in an illegal armed group, unlawful possession of weapons, and armed resistance to law enforcement officials.[150] In November 2007 Fasiman Galaeva filed a complaint with the prosecutor's office regarding unlawful actions by the law enforcement personnel. The response by the prosecutor's office stated that a preliminary inquiry into her complaint had been conducted, and "the actions of the servicemen of the Temporary Operative Group of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in the Malgobek district of Ingushetia and the personnel of the Malgobek district police department, who conducted a search in the house belonging to Galaeva F.Kh., were legitimate and involved no violations." Fasiman Galaeva's request to initiate a criminal case was refused.[151]

Commenting on the decision not to launch a criminal investigation into Fasiman Galaeva's complaint, Yuri Turygin told Human Rights Watch that the law enforcement officials had a judicial sanction to search the Galaev household. They noted that when they entered the house, they saw the Galaev brothers watching a video of the October 2002 Nord-Ost theater hostage-taking in Moscow, and this allegedly evidenced their support of terrorism.[152] He also claimed that Ruslan Galaev and Said-Magomed Galaev opened fire on the servicemen, who then had no other choice but to fire in response.[153] Although Human Rights Watch has no evidence to confirm whether the Galaev brothers put up armed resistance, based on the Galaevs' description of the special operation-servicemen breaking into the house, shooting without warning-the law enforcement personnel would have been responsible for excessive use of force, and in particular unjustified use of lethal force. Further, there is no evidence that any ballistic examination was carried out to confirm that the Galaev brothers in fact fired weapons at the servicemen.

Killing of Khusein Mutaliev

On March 15, 2007, in the town of Malgobek, Khusein Mutaliev (born 1980) was mortally wounded by unidentified federal servicemen. According to Mutaliev's relatives, between 5 and , around 20 armed servicemen in camouflage uniforms broke into their home. Some of them were masked. Several servicemen jumped over the fence and opened the gates for the rest of the group. They forcibly entered the house, did not identify themselves or explain the reasons for their actions, and forced all the family members face down on the floor.

Khusein Mutaliev's mother told Human Rights Watch,[154]