Darfur 2007: Chaos by Design

Peacekeeping Challenges for AMIS and UNAMID

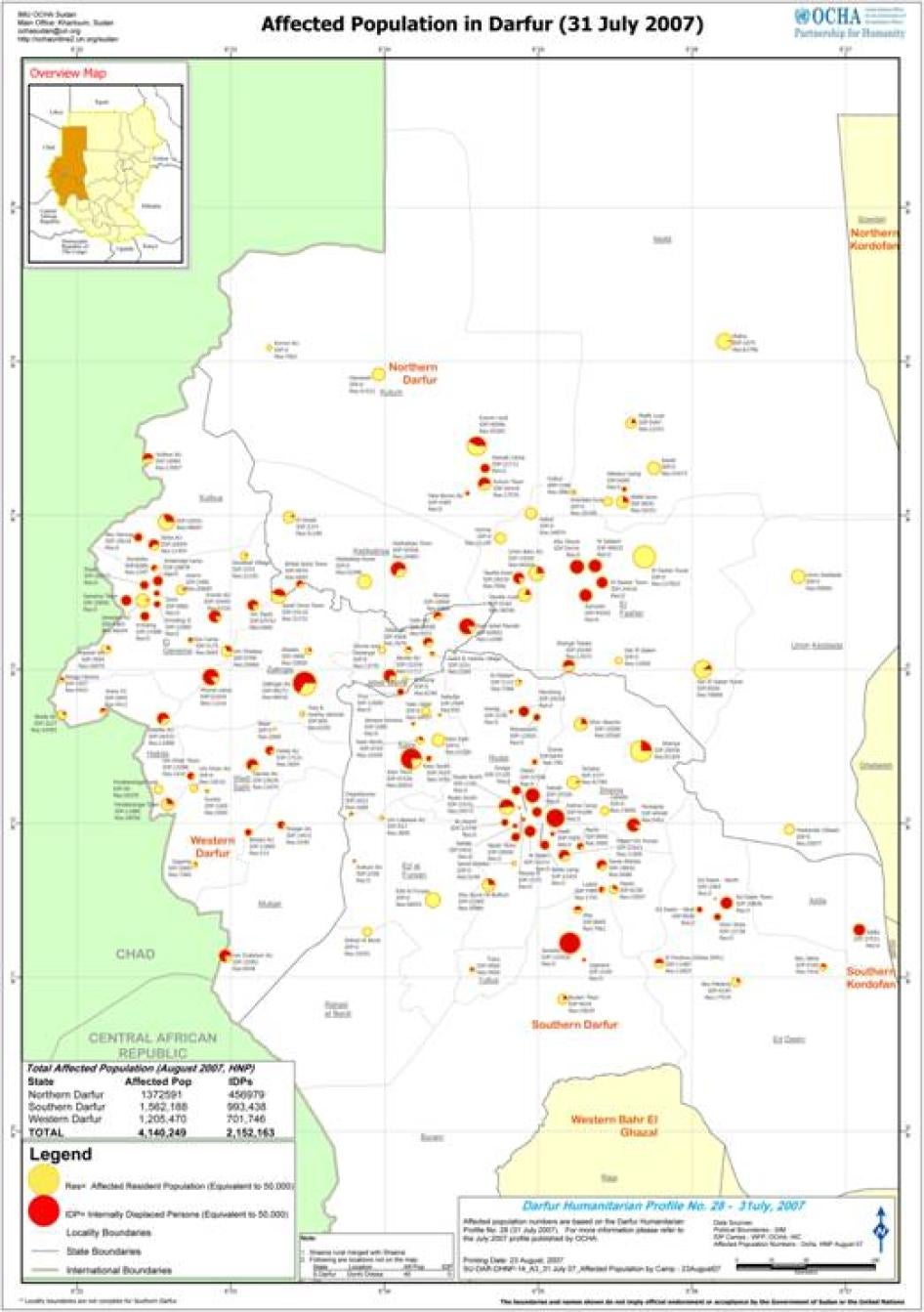

Maps

2007 United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)

Summary

The Sudan government's campaign of "ethnic cleansing" in the Darfur region has gained widespread international attention since it began four years ago. Today, the situation is transforming from a highly destructive armed conflict between rebels and the government into a violent scramble for power and resources involving government forces, pro-government militias known as "Janjaweed," various rebel and former rebel factions, and bandits. Despite its complexities, this chaotic situation must not deflect attention from the Sudan government's primary responsibility for massive civilian deaths and for the displacement of some 2.4 million people since 2003, including 200,000 refugees.[1]

While the Darfur conflict is often characterized as a clash between "Arab" and "non-Arab" African people, this radically oversimplifies and mischaracterizes the conflict. Rather, the ways in which both the rebel movements and primarily the Sudanese government have manipulated ethnic tensions have served to polarize much of the Darfur population along ethnic lines. These tensions create shifting alliances among the government, Arab and non-Arab tribes, and rebel groups as well as internecine conflicts among competing Arab groups and among rebel factions. Rebels and former rebels have directly targeted civilians from other non-Arab groups and attacked African Union (AU) peacekeepers and humanitarian workers trying to provide assistance to Darfurians. These subsidiary conflicts themselves contribute to the mass displacement and deaths of people. The government continues to stoke the chaos and, in some areas, exploit intercommunal tensions that escalate into open hostilities, apparently in an effort to "divide and rule" and maintain military and political dominance over the region.

On July 31, 2007, the United Nations (UN) Security Council, with the consent of Sudan, agreed to deploy a peacekeeping force of up to 26,000 military and police personnel in Darfur. This combined African Union and UN "hybrid" force (UNAMID) is mandated to take over from the beleaguered AU peacekeeping mission, AMIS, which has been operating in Darfur since 2004. The new mission will be equipped with greater resources to protect civilians and humanitarian workers, and to oversee implementation of a tenuous peace agreement.

Expectations are high for what UNAMID could accomplish, but it will face many challenges. It is therefore imperative that alongside the peacekeeping operation, the international community maintains continual pressure on the Government of Sudan, as well as other parties to the conflict, to reverse abusive policies and practices that contribute to civilian insecurity. These policies include deliberate and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, continuing support for abusive militia/Janjaweed and the failure to disarm them, obstructing the deployment and work of AMIS peacekeepers and humanitarian workers, failing to address the culture of impunity (including by failing to abolish laws providing immunity or otherwise strengthen the justice system) and refusing to cooperate with the International Criminal Court, and allowing the consolidation of ethnic cleansing through land use and occupation.

The most important task for the international peacekeepers will be to improve security for the civilian population and make freedom of movement possible for the 2.2 million displaced persons inside Darfur and the millions of others who remain in their towns and villages. It is unlikely that the mere presence of international peacekeepers will be enough to deter attacks on the civilian population from government forces, Janjaweed, rebels, and others. In order to contribute to the protection of civilians, Darfur will require a proactive and mobile peacekeeping operation.

The peacekeeping force will also have to create a secure enough environment so that humanitarian groups can reach the estimated 4.2 million people in desperate need. Finally, the force must support the government's law enforcement and justice systems through monitoring, constructive criticism, and capacity building initiatives to enable state institutions to provide protection to Darfur's beleaguered populations rather than serving as an element of their oppression.

Moreover, Darfur's civilians need protection now, and cannot wait for UNAMID to become fully operational. Currently, AMIS is not an effective protection force. Recent efforts to strengthen it with additional resources (such as additional police and logistical capabilities and two additional battalions) have the potential to improve security, as well as ease the transition from AMIS to UNAMID. In this interim period, AMIS protection initiatives that have ceased in certain areas, including daytime, nighttime and firewood patrols, should resume immediately.

The situation in Darfur remains grave. The violations of international human rights and humanitarian law that Darfurians suffered in recent years have continued into 2007. Government air and ground forces have repeatedly conducted indiscriminate attacks in areas of rebel activity, causing numerous civilian deaths and injuries. Looting, beatings, murder, and rape perpetrated primarily (but not exclusively) by government forces, Janjaweed, and former rebels have created a climate of fear that impinges on everyday life for millions of people in towns, villages, and displaced persons camps.

People forced to flee their homes who make it into the camps invariably find themselves trapped there. If they venture outside to collect firewood, farm, or attempt to return to their villages they risk being harassed, robbed, beaten, or murdered by Janjaweed or other armed men. Women and girls attempting to carry out the routine activities of daily life are often sexually harassed and raped by these armed men, who include government forces or even former rebels who once claimed to be fighting on behalf of their victims. Insufficient security in the camps has exacerbated problems of domestic violence and sexual exploitation.

Humanitarian assistance for populations at risk remains precarious. Rebels, former rebels, government forces, and the Janjaweed have hijacked, robbed, harassed, or physically abused humanitarian workers, hindering the delivery of aid. The government also continues to threaten and place unnecessary bureaucratic obstacles in the way of humanitarian organizations.

The Government of Sudan's systematic failure to address these abuses is reflected in its reluctance to take genuine steps to protect civilians, end the impunity of perpetrators, or undertake other meaningful measures to ensure accountability for the crimes committed in Darfur. The government has failed to invest in its own police force, which is far too weak to disarm the Janjaweed, let alone protect people from rape and robbery and other crimes. Some police themselves commit such abuses with impunity. Thus, the militia forces that rain violence on Darfur remain strong, active, and unchallenged. Some former militiamen have been incorporated into civil defense forces, such as the Central Reserve Police, whose duty is to protect displaced persons and other civilians.

Although the intense government military operations that caused massive death and displacement in 2003 and 2004 have declined, the government's abusive policies continue through many of the same mechanisms as before, both in overt and more subtle ways. The current conflict with its many actors and agendas may be more complex and opaque than the crisis of 2003-2004, but it is no less threatening to the lives, security, and livelihoods of millions of Darfurian civilians who remain vulnerable to violence.

This ongoing violence prevents hundreds of thousands of displaced people from returning home. Meanwhile, the land on which displaced persons and refugees once lived has become free for the taking, open to use and occupation by the ethnic groups comprising the Janjaweed, by new arrivals fleeing a linked conflict in neighboring Chad, and by others. Land occupation serves to consolidate the ethnic cleansing campaign, and greatly threatens the prospects for long-term peace in the region.

Much depends on the success of the transition from AMIS to the new peacekeeping mission. However, an enhanced peacekeeping presence alone will not end the abuses described in this report. The government and other parties to the conflict are ultimately responsible for bringing an end to widespread rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law. Structural changes leading to disarmament, accountability, and improved law enforcement are all needed, along with long-term economic and social development programs. Unless these issues are addressed together the future of the people of Darfur will remain in peril.

Recommendations

To the Government of Sudan

- Government forces and government-sponsored and supplied militia/Janjaweed must immediately (1) cease their campaign of ethnic cleansing and (2) stop all deliberate or indiscriminate ground and aerial attacks against civilians and civilian property in Darfur.

- Do not obstruct, and cooperate fully with, AMIS and UNAMID (1) to expedite the arrival and full deployment of the AMIS "Light Support Package" (LSP) and "Heavy Support Package" (HSP) and the UNAMID peacekeeping force and (2) to ensure that AMIS and UNAMID can carry out their mandates unhindered, including having freedom of movement throughout Darfur.

- Facilitate the full, safe, and unimpeded access of humanitarian personnel and the urgent delivery of humanitarian assistance to all populations in need in Darfur. Expedite entry visas and travel permits for all humanitarian aid organizations and workers, and fully cooperate with such organizations so that they can perform their humanitarian functions. Immediately cease jeopardizing the security of humanitarian personnel by using white aircraft and vehicles that may be mistaken for humanitarian transport.

- Enable the voluntary return of refugees and displaced persons to their homes in safety and dignity, including by ensuring security and freedom of movement in and out of camps and along key roads, and the urgent distribution of adequate grain and other food items, such as seeds and tools, and basic reconstruction materials to all populations in need. Publicly announce that official or unofficial occupation or settlement of land belonging to displaced persons will not be permitted.

- Seek international expertise to strengthen Darfur's law enforcement system by implementing professional training and providing adequate resources so that (1) victims of criminal offenses, especially victims of sexual violence, have access to justice and (2) law enforcement officials implicated in abuses are disciplined or prosecuted in accordance with international legal standards.

- Cease military, financial, and political support to, and recruitment of, abusive militia/Janjaweed and immediately implement militia/Janjaweed disarmament programs in accordance with relevant international standards.

- Investigate crimes against humanity, war crimes, and other violations of international law committed in Darfur since 2003, including those committed by the Sudanese armed forces and militia/Janjaweed, try alleged perpetrators in accordance with international fair trial standards, and confiscate all property unlawfully obtained and return it to the owners.

- Investigate, prosecute, and suspend from official duties pending investigation Sudanese officials alleged to be involved in the planning, recruitment, and command of abusive militia/Janjaweed.

- Fully cooperate with the International Criminal Court, as per UN Security Council Resolution 1593, including handing over Ahmed Haroun and Ali Kosheib in accordance with the arrest warrants issued by the Pre-Trial Chamber on April 27, 2007. Undertake legal reforms and other steps to strengthen Sudan's justice system, such as amending legislation and revoking the presidential General Amnesty Decree No. 114 of 2006 that confers immunity upon perpetrators of abuses.

- Take significant steps, including by engaging in substantial development projects, to help halt resource competition and conflict in Darfur.

To the "non-signatory" rebel groups and former rebel groups

- Cease all indiscriminate or targeted attacks against civilians, regardless of their ethnicity or political affiliation.

- Facilitate the full, safe, and unimpeded access of humanitarian personnel and the urgent delivery of humanitarian assistance to all populations in need in Darfur.

- Cease all attacks against AMIS peacekeepers and allow AMIS and UNAMID to carry out their mandate unhindered, including freedom of movement throughout Darfur.

- Immediately communicate the abovementioned orders to field commanders.

To the African Union Mission in Sudan

- Bolster civilian protection and freedom of movement including by actively patrolling along the main roads and in key areas such as markets, and reengage with the communities to build support and trust for reinstating "firewood" patrols and other short- and long-distance patrols inside and outside camps and towns.

To the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations and the AU Peace and Security Directorate's Darfur Integrated Task Force (DITF)

- UNAMID should be widely and strategically dispersed in stations throughout Darfur, so that it has access to the civilian population and to especially volatile areas. Peacekeepers should also be equipped and authorized to construct and deploy to temporary bases for short- and medium-length stays while permanent bases are being constructed.

- Ensure that UNAMID has strong rapid response capabilities, including sufficient personnel, attack helicopters, and armored personnel carriers (APCs), and real-time and accurate information gathering and analysis technology to carry out daytime and nighttime activities that could include reconnaissance missions, placing peacekeepers in positions to protect civilians prior to expected attacks, providing armed protection to civilians who come under attack, conducting search and rescue missions if humanitarian or other convoys are hijacked, or investigating ceasefire violations immediately after they occur.

Ensure that UNAMID carries out, in coordination with the local community, regular "firewood" patrols, market day patrols, foot patrols inside camps, as well as other day and night patrols inside and outside camps and towns, especially in volatile areas.

Ensure that UNAMID puts a particular focus on its civilian police component, and deploys well trained and well resourced police to monitor government and rebel policing activities and to engage in capacity building activities aimed at strengthening Sudanese police. Ensure the police are trained to investigate human rights abuses (in particular sexual violence) and that adequate numbers of female civilian police officers and interpreters are deployed. Police versed in children's rights issues should also be deployed.

Increase the number of human rights officers in Darfur, disperse them in satellite offices, provide them with sufficient interpreters and other necessary resources, and ensure that adequate numbers of female human rights officers are deployed. Ensure that human rights officers have a dual reporting line to the Office of the UN High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR) and UNAMID and continue to allow OHCHR to publicly report their findings.

Ensure that UNAMID maintains ongoing contact with humanitarian agencies to understand where UNAMID assistance is needed to secure humanitarian relief, and respects the space that humanitarian agencies require to carry out their activities in a neutral fashion.

- In accordance with Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000), ensure that UNAMID has a strong gender component at all levels, and that peacekeepers are held accountable for any acts of sexual harassment, exploitation, or violence.

To UN member states and AU member states

- Establish and closely monitor benchmarks for all parties to the conflict for compliance with their obligations under international humanitarian and human rights law, and impose unilateral or multilateral sanctions for non-compliance. These benchmarks should include (1) ending attacks on civilians and the unlawful use on aircraft of UN and AMIS colors or markings, (2) ending support to abusive militia/Janjaweed and initiating militia/Janjaweed disarmament programs, (3) facilitating the expeditious deployment of AMIS and UNAMID and ensuring they can carry out their mandate unhindered, including having freedom of movement throughout Darfur, (4) ending impunity and promoting accountability through full cooperation with the International Criminal Court, and undertaking legal reforms and other steps to strengthen Sudan's justice system, (5) increasing humanitarian access, and (6) ending the consolidation of ethnic cleansing through land use and occupation. (For a more detailed list of these benchmarks see "International response" below).

Ensure that AMIS and UNAMID have adequate personnel, equipment, technical expertise, and other resources, noting that improved security in Darfur will be contingent upon their rapid response capabilities, patrolling activities, and police mandate.

- Provide assistance and support to the voluntary return and effective reintegration of Dafurian refugees and displaced persons into their home communities.

- Support international humanitarian assistance and human rights monitoring and investigations in Darfur.

- Contribute to the economic and social reconstruction of Darfur.

To the United Nations Security Council

- Establish and closely monitor benchmarks for all parties to the conflict for compliance with their obligations under international humanitarian and human rights law and impose sanctions for non-compliance. (For a detailed list of these benchmarks see recommendations to UN member states and AU member states above.)

Background

In April 2003 a simmering low-intensity conflict dramatically escalated when rebel groups attacked the airport in El Fashir, the capital of North Darfur, destroying several Sudanese air force planes.[2]In response to this and subsequent rebel attacks the Sudanese government launched massive military operations against civilian populations primarily of the Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit ethnic groups-the same ethnicities as the majority of the rebel Sudan Liberation Army/Movement (SLA) and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM). The campaign was carried out by government forces and by militias known as the Janjaweed, whom the government recruited, supported, armed, and coordinated in many of the attacks.[3] By mid-2004 tens of thousands of civilians had been killed and more than a million people displaced, and hundreds of villages had been burned and looted.[4] Rape and sexual violence against women and girls has been a prominent feature of the ethnic cleansing campaign carried out by government forces and militias, both during and following displacement in Darfur.[5]

Ethnic distinctions in Darfur are highly politicized and complex. The region is home to numerous groups who generally identify themselves as either "Arab" or "non-Arab," and tensions between people belonging to these broad categories have existed for decades. In the 1960s Darfur was used as a base by largely "Arab" Chadian rebel groups fighting to overthrow their country's government. In the 1970s Libyan leader Col. Mu`ammar al-Qadhafi, bent on "Arabizing" Chad and Sudan, created and supported militant "Arab" groups in Darfur whose aim was to overthrow the governments of both countries. Neither plan succeeded, but the population of Darfur continued to become polarized into opposed "Arab" and "non-Arab" groups.[6]

In the 1980s climate change, famine, and the intensifying conflict in southern Sudan brought further political instability to Darfur. During the dry season nomads from the northern Sahel have long migrated south into the fertile belt of central Darfur mainly occupied by non-Arab farmers. Disputes over trampled crops and grazing land have been common, but in the past were usually settled through traditional reconciliation methods. In the mid-1980s the government of Sudan began arming Arab militia groups to aid its campaign against southern Sudanese rebels and the communities perceived to be supporting them. The introduction of modern weaponry, along with a severe drought, further polarized ethnic relations in the Darfur region. Clashes over land, grazing, and water resources intensified in the 1990s, and the underfunded and under-resourced Sudanese police rarely responded appropriately; nor did the central government invest in the type of development activity that might have calmed and prevented further conflict. Some non-Arab communities, particularly the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa, perceived the federal government as biased in favor of Darfur's Arab communities for both racial and political reasons.[7] It was these non-Arab grievances that culminated in the attacks on the El Fashir airport.

In 2003 the Sudanese government exploited tensions in the region further by mobilizing thousands of desperately poor men, most of whom identify themselves as Arabs, from land severely scarred by desertification and water shortages, into Janjaweed militias. The Janjaweed went on to commit widespread atrocities against the largely non-Arab African communities of settled farmers throughout the region, reaping the war booty and causing mass flight into internally displaced person (IDP) camps and over the border into Chad. The ongoing terror prevents displaced people from returning home.

International attention in Darfur often focuses on aerial bombardments and the burning of villages in violation of international humanitarian law. While such attacks continue to drive people into camps, it is constant harassment and abuses primarily by the government, Janjaweed, and former rebels that keeps them there. Police, who are responsible for protecting people inside and outside camps, lack the political will and resources to prevent these abuses, and on numerous occasions have themselves committed abuses. The climate of fear, along with the land occupations and almost total lack of accountability for war-related crimes, is essentially consolidating the ethnic cleansing campaign and allowing it to continue.

During the past three years, Darfur has experienced changes in the dynamics of the conflict, but there has been no dramatic or sustained improvement in security for civilians. Attacks may subside during the dry season, when farms are idle and nomads and farmers are in less contact with each other, and people have also learned to avoid provoking attacks by remaining indoors or traveling to and from markets at night. While this temporarily lowers the number of reported abuses, it does not indicate that the situation is improving.

In April 2004 the Sudanese government and the two rebel movements signed a humanitarian ceasefire agreement mediated by the Chadian government with support from the African Union. This led to the establishment of an AU peacekeeping mission, the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS), which was at first mandated to provide military observers to monitor and report on the ceasefire; an armed force to protect civilians and humanitarian aid workers; and an unarmed civilian police force and support teams were added later.[8] Since that time, AMIS has increased its forces to over 7,000 personnel (including 612 military observers, 5,202 force protection personnel, and 1,425 civilian police).[9] This is now being supplemented by a "Light Support Package" (LSP) and a "Heavy Support Package" (HSP) that will provide additional personnel and resources as a build up to the eventual transition of AMIS to UNAMID.

Most of the LSP has been deployed, which included small numbers of military, police, and civilian personnel, as well as medical and public information equipment, and armored personnel carriers (APCs). The HSP includes 2,250 military personnel to focus their efforts on transport, engineering, logistics, surveillance, aviation, and medical service, as well as 301 police and three police units. Civil affairs, humanitarian liaison, public information, mine action, and political support officers are also included, as well as military, police, and civilian support staff. The HSP also includes attack helicopters. As of September 2007 at least 35 percent of the HSP civilian personnel were deployed and countries had pledged to provide nearly all the additional resources, with the exception of the helicopters.[10]

In an effort to strengthen the international response to the crisis, the UN Security Council has passed various resolutions imposing an arms embargo and calling for an end to offensive military flights and for the disarmament of the Janjaweed.[11] Resolution 1593, passed in March 2005, referred the situation in Darfur to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and imposed an obligation on Sudan to fully cooperate with the court's investigations. On April 27, 2007, the ICC's Pre-Trial Chamber issued arrest warrants for Sudan's state minister for humanitarian affairs, Ahmed Haroun, and the Janjaweed militia leader, Ali Kosheib, for a series of attacks in West Darfur in 2003 and 2004 (see also below).[12]

A second Security Council resolution established a sanctions committee that has imposed travel bans and asset freezes on four individuals from different sides of the conflict (see also below).[13] The US government has also placed unilateral sanctions on three Sudanese individuals and 30 companies owned or controlled by the Government of Sudan, and one other Sudanese air transport company that violated the arms embargo.[14]

A third Security Council resolution established the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) and provided additional UN non-military resources to the Darfur region. At first it was envisaged that UNMIS would only facilitate the implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which brought an end to the 21-year civil war between north and south Sudan, but it was also mandated to provide non-military resources to Darfur as well.[15]

At the same time, the situation on the ground in Darfur has grown increasingly complicated as the number of actors has proliferated. From the start, AMIS has been understaffed, under-resourced, and beset with command and control problems, and the fighting, displacement, and abuses continued. Then, in October and November 2005, the SLA rebel movement, which constituted the main military rebel force on the ground, began to splinter significantly at a conference in the eastern Darfur village of Haskanita that was supposed to unify the movement-instead, it did the opposite. Abdul Wahid Mohamed al Nour, a prominent rebel leader with support from the Fur ethnic group, refused to attend and Minni Arku Minawi, who drew support mainly from the Zaghawa, was elected leader. Three months later, the resulting rift culminated in heavy fighting in North Darfur between SLA fighters loyal to these two leaders.[16] Many civilians were killed in the fighting and others were forced to flee, as each group targeted not only fighters but also civilians from the opposing tribes.[17]

The SLA fractured further in the run up to, and aftermath of, the signing of the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) between the government and Mini Minawi's SLA faction (SLA/Minawi) in Abuja, Nigeria in May 2006. Thereafter, Minawi was appointed special assistant to the president of Sudan and moved to Khartoum. The DPA further inflamed relations among rival "signatory" and "non-signatory" rebel groups, and the government also escalated attacks against non-signatories. Since then a small number of other rebel leaders and their followers have entered into agreements with the government, including Abul Gassim Imam Elhag Adam, who was subsequently appointed governor of West Darfur.

Meanwhile, Chadian rebels bent on deposing Chadian President Idriss Dby have been operating out of West Darfur, and Sudanese rebels have been operating out of Chad. In 2006 and 2007 Libya and Saudi Arabia brokered peace agreements committing the governments of Sudan and Chad to cease providing support to the other country's rebel groups.[18] The February 2006 Tripoli Agreement proposed a mechanism to enforce these commitments in the form of joint patrols that would be deployed to both sides of the Chad-Sudan border.[19] Libya also hosted peace talks between Dby's government and the Chadian rebels, but on July 2, 2007, after having dropped their demands that Chad's political parties be included in the negotiations and that President Dby step down, the rebels threatened to return to all-out hostilities due to lack of progress.[20]With peace in Chad far from secure, United Nations and European Union (EU) personnel traveled to Chad in August 2007 to assess the prospects for deploying a proposed joint UN-EU civilian protection force to eastern Chad (the force is also designed to have a presence in the northeastern region of the Central African Republic). The EU is making preparations for sending the force and President Dby has agreed to the force in principal.

An often overlooked aspect of the Darfur conflict is the political and social dynamics of the Arab communities in the region. While some Arab militia are still being organized, armed, and supported by the government and often do its "dirty work," some Arab communities have remained neutral. Some individuals have spoken out against government and militia abuses and some joined the rebels. Groups with a predominantly Arab base have also taken up arms against the government independently, in protest against underdevelopment and the exploitation of their grievances for political ends. On August 14, 2007, the secretary-general of one of these rebel groups, the Democratic Popular Front Army (DPFA), informed Reuters they had kidnapped 12 Sudanese soldiers.[21] "The government took advantage of our sons and paid them and gave them arms and used them to fight against others," he said, "We want them to stop, [we want the Popular Defense Force] to leave people to live their lives and be able to farm and feed their cattle and eat and live in peace."[22] The government denied the kidnapping allegations.[23] Since January 2007 Darfur has also been the site of intense inter-tribal fighting amongst members of various Arab groups, many of whom belong to Sudan's security forces.

It would be impossible to list every human rights abuse and violation of international humanitarian law that has taken place so far in Darfur in 2007.[24] The accounts in this report sketch the broad contours of the conflict in Darfur's three main states and in the especially volatile Jebel Marra region. The final sections of the report attempt to convey the everyday experience of millions of Darfurians caught up in the conflict, the obstacles faced by humanitarian groups and peacekeepers trying to assist them, and the steps UNAMID and the international community should take to improve the human rights situation in Darfur. This report is based on information not only about the situation of the 2.2 million people in Darfur who fled their homes, but also about the approximately 4 million people who have not been displaced from their towns and villages, around half of whom also have humanitarian needs resulting from the conflict (see "Everyday Life for Civilians in Darfur," below). UNAMID will face huge challenges in trying to fulfill its mandate to provide civilian protection, create a safe environment for humanitarian workers, and support the implementation of a fragile peace agreement, but for Darfur's civilians successful implementation of these tasks could be the difference between life and death.

North Darfur

In 2007 most of the fighting in North Darfur involved government forces, SLA/Minawi fighters, and various rebel splinter groups. In March 2006 a predominantly Zaghawa-based SLA splinter group known as the Group of 19 (G-19) came into existence. Another rebel group known as the National Redemption Front (NRF), a coalition of members from other rebel groups (including G-19 and the Justice and Equality Movement), emerged in June 2006 but later disintegrated. Both had strongholds in North Darfur and carried out attacks on the government.

The government launched an offensive against the NRF in late August conducting aerial bombing and land attacks with blatant disregard for civilian lives.The government also launched indiscriminate air and ground attacks on Birmaza in November and Abu Sakin in December 2006, with reports of dozens of fatalities.[25]Government aircraft indiscriminately using unguided "dumb" bombs from medium and high altitudes caused civilian casualties and mass displacement-20 civilians were killed and over 1,000 displaced in the late August offensive noted above, for example[26]-and obstructed the work of humanitarian groups.[27] Those whose villages were not attacked often fled in fear that they might be. A confidential correspondence by a munitions expert, seen by Human Rights Watch, states that bombs were typically rolled out of the back of an aircraft, endangering everyone within a 150-meter radius of the detonation.[28] Such imprecise bombings of populated areas violate the prohibition under international humanitarian law of attacks that do not discriminate between military targets and civilians.[29]Persons knowingly or recklessly conducting or ordering such attacks are responsible for war crimes.[30]

One of the most notorious bombing campaigns of 2007 occurred in and around the village of Um Rai between April 19 and 29. Government helicopter gunships and Antonov aircraft attacked the village and killed and wounded civilians and destroyed property and livestock. A school filled with some 170 children was hit, injuring several of them. Two civilian adults were also killed in the attack.[31] Both the UN secretary-general and the high commissioner for human rights condemned these bombings as indiscriminate because they failed to distinguish between military targets and civilians.[32]

Government forces have used military aircraft painted white-the color used by UN and AMIS forces-for reconnaissance, supply operations, and attacks.[33] At a distance, the aircraft resemble United Nations and AMIS planes and Mi-8 helicopters; sometimes they even have UN markings.[34] Use of these white aircraft for military purposes is a violation of international humanitarian law, specifically the improper use of the United Nations emblem, and, when simulating the protected status of peacekeeping forces and humanitarian operations to conduct attacks, the prohibition against perfidy.[35] Use of these planes puts genuine UN, humanitarian, and AMIS flights at risk because rebels might mistake them for legitimate military targets. People in desperate need of aid may flee from humanitarian flights if they cannot distinguish them from government military aircraft.[36]

Residents of North Darfur have increasingly complained to the international community about abuses carried out by forces aligned with former rebel leader Mini Minawi.[37] The abuses stem primarily from the split between Minawi and Abdul Wahid after the Haskanita conference in late 2005 (see Background, above). Mini Minawi's mainly Zaghawa forces soon began battling Abdul Wahid's mainly Fur forces and many civilians were attacked by fighters from both sides simply for their ethnicity. In April 2006 many civilians fled rebel fighting in the especially fertile area around Korma, where each group was trying to gain a stronghold.[38]

In 2007 Minawi's men have been responsible for numerous attacks on civilians. After concluding a July 2007 visit to Sudan, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Sudan Sima Simar stated, "I have recently received allegations of serious violations of human rights in areas under SLA/MM [SLA/Minawi] control. In particular harassment, extortion, torture, and sexual violence in Tawila and Shangil Tobayi, North Darfur. I also received information about forced disappearances and killings in Gerida, South Darfur [caused by SLA/MM in September 2006]."[39] Abdel Aziz Salim, legal advisor to SLA/Minawi, told journalists that these were "nonsensical accusations,"[40] but Human Rights Watch has received confidential information from knowledgeable sources corroborating Sima Simar's allegations.[41] These abuses against civilians, as well as clashes between SLA/Minawi fighters and rebel groups, have also caused substantial displacement, especially of people from Korma and Tawila, to various displaced persons camps in the area.[42]

The people of North Darfur have also had to contend with ongoing militia attacks, including in the context of the government attacks on Birmaza and Abu Sakin, described above.[43] In April 2007 there was a militia attack (with government officials participating) on Abu Jokha market and other villages inhabited by the Dorok ethnic group. The conflict within which these attacks occurred was unusual in that the militia mainly comprised Gimir men who, like the Dorok, are commonly regarded as non-Arab. As has often been the case, the most brutal acts were carried out by the side most closely allied to the government-in this case the Gimir, many of whom are also members of official government forces.[44]

The conflict was sparked when some Gimir men accused some Dorok men of livestock theft at the Abu Johka market, but the roots of it seem to lie in deeper disputes over land.[45] The Dorok and Gimir both live in the area and the attacks may have been an attempt by the Gimir to evict the Dorok. The Gimir militia may also have suspected the Dorok of providing support to rebels.[46]

As a result of the livestock theft accusation a Dorok man was shot and killed.[47] Intense violence ensued. At first there were casualties on both sides, but on the second day Gimir militia brutally attacked the market and outlying Dorok villages. Hundreds of armed men in vehicles with mounted guns and on horse- and camel-back looted houses and killed civilians. Some 10,000 people fled.[48]

According to eyewitnesses, the officer in charge of police in the town of Saraf Umra participated in the attack and distributed weapons while the attack was taking place.[49] Other members of Sudan's security forces were also involved.[50] UNMIS reported that in addition to the market, "seven other villages were also attacked and 40 civilians were killed and 25 others were wounded."[51] Confidential sources suggest the number of villages attacked was much higher, but the number killed may have been slightly lower.[52]

Conflicts such as this one, which appear to revolve around land and livestock, enable the government to claim the fighting is "inter-tribal" and not their responsibility. However, as in so many cases, the facts show that government agents were involved in the attack. The government's failure to protect civilians and bring perpetrators to justice is not a passive failing, it is systematic policy.

South Darfur

In February 2005 Darfurian children drew for Human Rights Watch researchers scenes of armed men on horses and camels attacking their villages.[53] The drawings included images of people fleeing attack helicopters and falling bombs. Large-scale air and ground attacks are less frequent today, but they are not unknown. Buram locality in South Darfur has been the site of two recent campaigns that recall images from the height of the conflict in late 2003 and 2004.

In 2006, as various rebel groups were negotiating with the government and others were splintering off into increasingly numerous factions, a former SLA/Minawi rebel fighter named "Siddiq" founded a new group and settled in Buram locality. The presence of his group further destabilized an area where many Arab and African groups had been living together in relative harmony prior to the conflict. Siddiq's group and other rebels launched small-scale attacks against government targets in the locality. Arab tribal leaders felt threatened and blamed non-Arab groups for allowing the rebels into the area.

Before long, Arab militias comprising mostly men from the Habbania ethnic group launched what one observer described as a "ridiculously brutal" attack on dozens of villages, in which the militia "went out of their way to torture people-tying men to horses and letting the horses run; throwing people into burning houses; killing many young children."[54] The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that militia claiming to have material support from government authorities burned and looted villages, displacing thousands of people primarily from the Zaghawa, Masalit, and Misseriya-Jebel tribes, and killing possibly hundreds of civilians.[55] Some people from the area believed the real motivation behind the attack was to "change the demography of the region before the arrival of international troops."[56]

Fighting started up again on May 12, 2007, this time with far more direct government involvement, after rebels ambushed a large convoy of police and Popular Defense Force vehicles that was heading to Buram locality to confront Siddiq's group about its alleged involvement in marijuana trade.[57] In retaliation the government launched an air attack on several villages, claiming they were aiming at rebels. Meanwhile, Gimir members of the Popular Defense Force went on a rampage, looting property, raping several women, and beating and shooting others.[58] Entire villages including Um Bereida and Sessaban, which had already received people fleeing the 2006 attacks, were targeted for their support or perceived support of the rebels.[59] An international observer told Human Rights Watch, "The second attack was a carbon copy of the first, but without the high casualty figures. This time people fled from what they remembered in 2006."[60]

An emerging feature of the conflict in South Darfur is the rising intensity of inter-Arab fighting. Small skirmishes over political power and land rights as well as accusations of murder and abduction are common among various Arab groups in Darfur.[61] But the level of violence dramatically increased after many Arab men were recruited into government security forces, primarily the Popular Defense Force and Border Intelligence force, each of which are notorious for carrying out attacks against civilians.[62]

The governor of South Darfur downplayed the violence, describing to a journalist how the clashes were "just a natural part of the life of the tribes," and said the fighting was predictable.[63] But this "natural" fighting exploded to new levels in 2007 and the government was unwilling to protect civilians and prevent members of its Popular Defense Force and Border Intelligence from engaging in predictable attacks that resulted in death, beatings, looting, and mass displacement.

While Arab communities bore the brunt of these internecine conflicts, the hostilities have broader repercussions because they contribute to the general climate of insecurity that is preventing Darfur's 2.2 million internally displaced persons from leaving their camps or returning home. As one humanitarian worker told Human Rights Watch, "This is happening at a seasonal time when displaced people want to be farming."[64]

In January 2007 the intense inter-tribal fighting broke out between the Tarjum and Rizeigat Abbala groups in the Bulbul area of South Darfur. Both have members in Sudan's security forces. A number of Tarjum men are enlisted in, and were armed by, the Popular Defense Force, and many Rizeigat Abbala are enlisted in, and were armed by, the Border Intelligence force.[65] By March over 100 people had been killed or injured, thousands of civilians had been displaced, their property stolen and houses burned.[66] The immediate tensions of the conflict can be traced to the Rizeigat Abbala accusing the Tarjum of murders and the Tarjum accusing the Rizeigat Abbala of abductions.[67] But political maneuvering, land competition, and government favoritism towards the Rizeigat Abbala probably lies at the root of this conflict.

In 1995 the Tarjum, a traditional farming and cattle-herding Arab group, had been granted stewardship over part of the traditional land of the non-Arab Fur tribe. The Rizeigat Abbala are pastoralists and camel herders, and Bulbul is on their traditional migratory route. Small Rizeigat Abbala settlements have proliferated on the land over the years, creating tensions with the Tarjum. The Rizeigat Abbala have no land of their own, and, according to OHCHR, this may be why they entered the Darfur conflict on the government side.[68] Indeed, some Rizeigat Abbala have even settled on land from which the Tarjum have been displaced.[69]

In early 2007 the government tried to calm tensions by facilitating a reconciliation agreement between the Tarjum and Rizeigat Abbala and sending security forces to the area, but the agreement was soon broken and fighting resumed.[70] The intense fighting finally subsided in March, but started again three months later and has now spread to West Darfur, with reports of scores of casualties on both sides, including the killing of Tarjum civilians at a funeral procession on July 31, 2007.[71] A Tarjum tribal leader told journalists that a temporary ceasefire agreement was signed in mid-August,[72] but history has shown that these agreements are very fragile, and the looting of a few cattle or the murder of one person may spark a return to all-out conflict.

In early 2007 fighting also erupted between the Salamat and Fallata on one side and the Habbania on the other-all Arab groups-in South Darfur and then broke out again in late August.[73] A South Darfur observer explained to Human Rights Watch, "The government is totally unable to deal with these tribal conflicts because the government supported the Habbania and Fallata with guns and helped build their militias. Just like the Tarjum and Rizeigat Abbala fighting, the government doesn't want to take concrete actions to stop the violence."[74] As long as the Sudanese government continues to selectively recruit, arm, or otherwise support militia on an ethnic basis, Darfur's communities will continue to be divided and destroyed.

West Darfur

West Darfur has less of a rebel presence than other states and its militias are considered to be more community based rather than government-controlled. The political situation in West Darfur is heavily influenced by its border with Chad. For years, rebel movements from each country have used the other as a base for attacks. Thousands of Darfurians have fled into Chad since the current conflict began and in 2007 Darfur saw an influx of approximately 30,000 Chadians, mostly Arabs, crossing the same border into West Darfur.[75] In January 2006, due to the fragile border situation, the UN temporarily raised the security level in much of the western part of West Darfur to "Phase IV," meaning its agencies were permitted only to carry out emergency life-saving operations. Some humanitarian NGOs also reduced their staff and activities.[76]

The northern corridor from the capital city of El Geneina to Jebel Moon is frequently attacked by government and militia forces. It is home primarily to the Messeriya Jebel and Erenga people-both regarded as non-Arab tribes. Rebels are based in the Jebel Moon area and they do visit and communicate with the civilian populations in the area. But when the government and militia attack, they often deliberately target civilians or launch attacks against rebels that result in looting of properties and cause disproportionate civilian casualties in violation of humanitarian law.

Lately, this northern corridor has been plagued by militia attacks on civilians and civilian abductions to which police and government forces seldom respond, attributing the violence to "inter-tribal" tensions. A spike in incidents of harassment, beatings, sexual violence, and extortion in the small village of Bir Dagig from April to July 2007 corresponded to a police withdrawal that left the town with no government presence. In April 2007 several women and girls from the village of Seleia were abducted by militia. The kidnappers claimed the community had stolen their camels, and demanded compensation. All the hostages were eventually released or escaped, although one girl was held for two months. Even though government officials in El Geneina knew the perpetrators, they chose to enter into "dialogue" with them, instead of arresting them and rescuing the girl.[77]

From late October to December 2006 militia and government forces attacked villages and IDP camps north of El Geneina. Some 50 civilians were killed in one attack in October alone.[78] Then on November 11, Sudan Armed Forces attacked civilians in the town of Sirba, burning over 100 houses. Eight civilians were killed in the attack, including one woman who burned to death in her house, and at least eight others received gunshot wounds, according to reports citing UN sources.[79] In December militia on horseback ambushed a truck transporting medicine and passengers, killing some 30 civilians.[80]

Jebel Marra

Jebel Marra, a mountainous area at the junction of North, South, and West Darfur, has been a rebel stronghold since the conflict began. At first, the rebels had such tight control over parts of the area that some areas were largely free of government and militia attacks. Now the area has been carved up by the fracturing rebel groups and former rebel groups, making the groups more susceptible to government and militia attacks.[81] Both civilians and rebels face beatings, rapes, and robbery from government forces and militia.[82] In the past year, many people from eastern Jebel Mara, especially around the village of Dobo, have fled to camps such as Abu Shouk and Shangil Tobaya in North Darfur while others have gone into hiding in the mountains.[83] The UN estimated that in July 2007 alone at least 12,000 people fled Jebel Marra due to insecurity.[84]

An exhaustive understanding of the abuses taking place in Jebel Marra is difficult to obtain, however: access to the region by observers has been severely limited at times due to ongoing insecurity. Some reports received by Human Rights Watch suggest that there have been serious crimes by both government and rebel forces that have not been adequately investigated. Information about rebel abuses in Jebel Marra, as well as other locations in Darfur, is likely to be further limited by the fact that victims, witnesses, and other informants are often reluctant to report abuses either out of a sense of loyalty or for fear of reprisals in rebel-held territories.

Although many attacks remain uninvestigated, a particularly vicious attack occurred in the Deribat area of eastern Jebel Marra in December 2006. Large numbers of militia and government forces killed civilians and abducted and raped dozens of women and girls. One survivor told OHCHR, "Three of the attackers came to my house. They forced me on the ground. One of them held my legs, while the other two raped me."[85] The rebel commander with whom Human Rights Watch spoke claimed that the attackers were members of government and militia forces, as well as members of Abdul Gassim's forces, the former rebel leader who sided with the government in late 2006 and was appointed governor of West Darfur in 2007.[86] A public report issued by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights confirmed this allegation. The report also attributed the attack to the fact that the Fur community in Jebel Marra is perceived to sympathize with the SLA/Abdul Wahid or SLA/Abdul Shafi factions, both of which opposed the Darfur Peace Agreement.[87]

Everyday Life for Civilians in Darfur

Consolidation of Ethnic Cleansing

In July 2007 the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that 160,000 people had been newly displaced since January 2007,[88] putting the total number of displaced at 2.2 million and the total number of people receiving relief assistance at 4.2 million, nearly two-thirds of Darfur's population. OCHA reported that many of Darfur's IDP camps can no longer absorb new arrivals.[89]

Beyond direct attacks on civilians, the confused nature of the recent hostilities-with inter-tribal fighting and groups switching sides-has contributed to the displacement of civilians. Yet in July and August 2007 government officials told international agency staffers based in Darfur that Darfur's 2.2 million internally displaced persons were beginning to return home and the international community should cooperate.[90] But what the government described as "voluntary returns" were in fact only brief excursions out of the camps on market days or during the farming season. Few displaced persons left the camps for more than a few days and even fewer returned permanently to their villages.[91] One person working with displaced people in Darfur described the government's discussion of voluntary return as "smoke and mirrors."[92] Another noted that last year the government tried to convince the relief community that its assistance to the camps was not needed because people were ready to go home. "Women want to go home, but can't," she told Human Rights Watch. "They sit in the camps and sing songs about their villages and draw pictures of their crops and flowers."[93]

Sexual Violence and Other Violence

Members of militia forces regularly perpetrate crimes of sexual violence against women and girls engaged in income generating activities, such as farming or collecting firewood, grass, and water. Market days are especially dangerous: armed men will intercept people coming to or from their homes to buy or sell goods.[94] Attackers are often dressed in a variety of military uniforms and travel in small groups of men on horses and camels. They demean women and girls because of their African ethnicity, calling them "slaves" and "Tora Bora," meaning "rebel," as they beat them with whips, gun butts, or fists. Victims of these abuses have been told to get off the land and stop collecting wood. Fighters from the SLA/Minawi former rebel group are also implicated in sexual violence, especially in the area of Tawila and Korma in North Darfur in 2007.[95] Women and girls are often targeted because of their ethnicity and accused of supporting the SLA/Abdul Wahid rebel faction.[96] Government soldiers and other state actors have also committed acts of sexual violence both in large attacks against entire populations, as was the case in Dereibat, and in small attacks against women and girls inside and outside camps and villages.

The issue of sexual violence remains shrouded in silence. Social stigmatization prevents many victims from telling relatives, doctors, or police what has happened to them. Some government officials deny that rape is a serious problem in Darfur, and humanitarian aid workers are afraid of jeopardizing their work if they speak out about the issue.[97] This allows the police to ignore victims or seek to punish them by countering their claims with charges of adultery.

Other government officials, however, have openly recognized the problem of sexual violence in the conflict. When a group of human rights experts appointed by the UN Human Rights Council requested information about exactly what steps the government had taken to address it, they were given a list of public events and workshops that had taken place, and told of the enactment of Criminal Circular No. 2 in 2004 that allowed, among other things, victims of sexual violence to receive medical treatment without first reporting to the police.[98] The government also provided information on the number of female police in Darfur and indicated that it would be increasing their numbers.[99] But these measures have yet to improve the situation for women and girls in Darfur. Perpetrators are rarely brought to justice and many of the mechanisms the state has established to combat sexual violence, such as the State Committees on Combating Gender-based Violence, function poorly and have had little impact.[100]

Although women and girls are the ones primarily collecting firewood and hay, militiamen also target men and boys who farm, travel to markets, or leave their villages or camps for other reasons. In these incidents the victims are often accused of being rebels and have been shot, robbed, harassed and beaten. Men and boys from non-Arab communities have also come to fear being subjected to extortion, beatings, and arbitrary arrests when they have to pass through formal and informal checkpoints manned by government security forces that are located outside villages and camps.[101]

Many Darfurians face violence inside camps and villages as part of everyday life as well. Each camp has its own dynamics, some being relatively calm while in others there is a considerable rebel or Janjaweed presence. Nighttime gunfire is regularly heard in many camps, and even when no casualties result it instills fear among the populace. Armed Janjaweed come and go from many of the camps, especially on market days. There have been numerous cases of robbery, murder, sexual violence, and harassment inside the camps, often perpetrated by Janjaweed, but also by rebels and former rebels, and displaced persons themselves. Government soldiers often act as thugs and harass and beat people in towns and at markets, as illustrated by the cases of two shopkeepers who were attacked by Border Intelligence in separate incidents in North Darfur in late July 2007.[102]

Land Use and Occupation

Far from the camps, back in the villages where displaced persons used to farm and graze their cattle, there is nothing to prevent the expropriation of land from its legal owners. Displaced persons regularly speak about how nomads and settlers are destroying their crops, dismantling thatched roofs and stick fences, and taking over their land.[103] This greatly threatens the prospect for sustainable peace.

Land use and occupation gained heightened international attention when approximately 30,000 mainly Chadian Arabs crossed the border into West Darfur in 2007. Many Chadians told an assessment team commissioned by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Sudan government's Commissioner for Refugees (COR) that they were fleeing attacks and abuses, actual or feared,by Chadian non-Arab militias and Chadian government forces. UNHCR recommended that Sudan grant the new arrivals refugee status, excluding those who were active or former combatants.[104]

But UNHCR was also concerned that many Chadian Arabs were settling on land abandoned by internally displaced Darfurians and refugees. According to the UNHCR/COR report, some families occupied fertile land "in areas that used to be predominantly Masalit villages before the Darfur conflict broke out in 2003."[105] Many settlers along West Darfur's Wadi Azoum riverbed informed the UNHRC/COR team that they intend to settle there permanently and would not be returning to Chad. They said that Sudanese nationals gave them specific directions as to where to settle. UNHCR has urged the Sudanese government to clarify land ownership issues, and ensure that those who own the land-mainly displaced persons in Darfur and refugees in Chad-will eventually be able to return home.[106]

It should not be assumed that this influx is mere opportunism on the part of the Chadian Arabs, who have given testimony to UNHCR of persecution in Chad. However, many people in West Darfur are suspicious of the Sudan government's motives, which further erodes the tenuous relationship between the government and many Darfurians. Some assume the male Chadian arrivals will be recruited into armed groups, that the influx ensures displaced people cannot return home, and that this new Chadian presence will result in tens of thousands of extra votes for the ruling National Congress Party in the Sudanese national elections scheduled for 2009.

Policing Darfur

Darfur is a vast territory that provides many hiding places for armed groups and ordinary bandits. There are few roads, most of which are unpaved. In the rainy season they are all but impassible. Communication is extremely limited, primarily to mobile phones, which have weak or no signals outside major towns. All this makes policing difficult even with a motivated, adequately staffed, and resourced force. The problem is especially severe in rural areas, where police lack vehicles or staff to patrol or respond to criminal activity, whether inside or near villages and IDP camps.

The Ministry of Interior and Darfur state officials have done little to ensure that Darfur's regular police-as opposed to auxiliary police forces such as the Central Reserve Police-have even minimal capabilities. This is a longstanding problem that predates the Darfur conflict. The many weaknesses of the police, in and of itself, are indicative of the government's lack of commitment to ameliorating the dire human rights situation in Darfur. In fact, one of the reasons the government relied on Janjaweed militia to fight rebels and attack civilians was because Darfur's police force was comprised heavily of local non-Arab men who would have likely opposed the government's political agenda and war tactics, and the government simply did not trust them. As a result, the regular police continues to be severely outmatched by all armed groups, including the pro-government militia. In one incident on March 7, 2007, over 20 Janjaweed in a vehicle and on horses entered Ardamata IDP camp in West Darfur and abducted at least two men in connection with the killing of one of their relatives. They confronted and threatened police who tried to intervene, and eventually handed the captives over to the military in the camp.[107]

In July 2007 OHCHR appealed to the Sudanese government to send police to the small village of Bir Dagig, approximately 30 kilometers north of the West Darfur state capital El Geneina, after a spike in violence was reported there, most of it committed by men in military uniform.[108] The police had been absent since April 2007, but in late July the government sent a group of officers to the village, as well as a police vehicle to conduct patrols along the road to the village of Kondobe, which was especially dangerous on market days.[109] But this small force, as well as the police in Kondobe, has as yet been unable to stop the abuses.[110]

The police lack staff, resources, political will, and basic competence to effectively protect civilians from armed groups or bandits. They often fail to register cases, visit crime scenes, or interview victims and witnesses. Even when cases are registered, most remain unsolved and leads are not followed up. When perpetrators are unidentified, police often expect victims or witnesses to follow up the leads themselves, but even when community members have tracked the footprints of suspected perpetrators, the police have ignored their findings.

In some areas, refusal to follow up investigations or even outright involvement by police officers in human rights violations has led local communities to regard the police as the agents of state abuses rather than the protectors of their security. (The same is true in some SLA/Minawi areas where the former rebels carry out policing activities and have subjected people to ill-treatment and have detained people in squalid conditions.[111]) Some communities have even banned government police from entering the camps, preferring to rely on untrained community members to provide security. In May 2005 displaced persons threw the police out of Kalma camp, one of Darfur's largest displaced persons camps, located close to Nyala, the capital of South Darfur. The following year, the police returned to the outskirts of the camp, but were still banned from entering.[112]

Many people are afraid to report crimes committed by state agents for fear of retribution, and others despair of reporting cases that they assume will not be properly investigated. Therefore, the number of cases reported to police provides little sense of the true scale of criminal and armed group activity. Cases of sexual violence are especially likely to go unreported because of fear of ostracism and stigmatization. Under-reporting in turn permits police to claim, disingenuously, that they cannot investigate crimes of which they are not aware.

There are many criminal complaints that do, however, make it into Darfur's justice system. The system, like law enforcement, is unfortunately fraught with a lack of resources and political will. In the first quarter of 2006 there was one prosecutor for the whole state of West Darfur, and for extended periods of time the state had no more than two or three prosecutors. In July 2007 more prosecutors reportedly arrived to relieve the burden. However, most prosecutors are based in large towns. Therefore detainees and complainants in remote towns and villages throughout Darfur are effectively cut off from a fair and functional justice system.

Numerous committees have been established to investigate specific incidents and special courts have been introduced to deal with conflict related crimes.[113] Regular courts are also operational in some areas. But very few footsoldiers and no high-level commanders have been convicted.[114] In numerous cases, police have refused to intervene or investigate members of Sudan's security forces committing human rights abuses because they were protected by domestic immunity provisions. On June 11, 2006, the president issued General Amnesty Decree No. 114 of 2006, which provided immunity from domestic criminal prosecution for various groups of people who had been involved in the conflict.

Humanitarian Access

Humanitarian groups are providing food, medical care, education, water, sanitation, and other assistance to some 4.2 million Darfurians in need of humanitarian relief. But these humanitarian workers have themselves increasingly come under attack. In June 2007 one in every six relief convoys that left provincial capitals in Darfur was hijacked or ambushed.[115] Between January and July 2007, 64 relief vehicles were hijacked and 132 staff members were temporarily abducted at gunpoint, 35 relief vehicles were ambushed and looted, and aid agencies were forced to suspend operations and relocate staff due to security concerns 15 times.[116] Attacks on the relief community have increased 150 percent in the past year.[117] Despite these problems, humanitarian groups are struggling to reach more people mainly by resorting to more air transport and other means.[118] According to UN estimates, in February 2007 some 900,000 people were inaccessible. That number apparently fell to 560,000 during May and June 2007, but the number remains staggering.[119]

While it is not always known who is responsible for particular attacks on humanitarian workers and hijackings of their vehicles, Sudanese government forces, rebel groups, former rebel groups as well as militia and/or bandits have all on various occasions been responsible.[120]Looting and hijacking of convoys appear to be aimed primarily at gaining resources such as vehicles and goods. But some of the worst attacks have targeted humanitarian personnel directly. In Nyala, the capital of South Darfur, Sudanese police and security officials raided a social gathering at an international nongovernmental organization (NGO) compound on January 19, 2007, and arrested some 20 NGO, United Nations agency and AMIS staff, severely assaulting several of them and sexually abusing one woman.[121]The authorities released them the next day, but charged them with consuming alcohol and creating a public disturbance. Some of the defendants were ordered to pay a fine and one remained under investigation for indecent and immoral acts. Others were acquitted for lack of evidence or had the charges dropped. Several NGO staff left the country and their case was temporarily closed.

In Gereida, an SLA/Minawi stronghold with some 130,000 displaced persons, SLA/Minawi forces attacked six humanitarian compounds on December 18, 2006.[122] The NGO Action Contre La Faim working in Gereida reported that one employee was raped, others were sexually assaulted, and a mock execution was performed.[123] The NGO staff was subsequently forced to withdraw, leaving the largest IDP camp in Darfur with only limited assistance.[124]

All the parties to the conflict in Darfur have delayed or denied humanitarian assistance to populations in need in violation of their obligations under international humanitarian law.[125] Humanitarian groups also face numerous government-imposed procedural hurdles. Some relief convoys have been denied access to camps and villages by military personnel, rebels, and former rebels. It was only on June 11, 2007, that SLA/Minawi soldiers in the Haskanita area of North Darfur agreed to provide safe access to humanitarian workers after services were halted at the end of 2006.[126]

In March 2007 Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator John Holmes tried to visit the Kassab IDP camp in North Darfur, but government military forces blocked him at a checkpoint.[127] The government later apologized and signed a communiqu pledging to reduce the administrative burdens on humanitarian agencies.[128] However, relief groups continue to contend with arbitrary limitations on personnel recruitment, delays at customs, denial of access to IDP camps and other areas, and other bureaucratic obstacles.[129]

Lessons Learned from Darfur's Peacekeepers

The success of UNAMID, the new UN-AU hybrid peacekeeping force, hinges crucially on its ability to overcome the limitations of AMIS, which has been criticized both by analysts and by displaced persons themselves.[130] Some residents of IDP camps have even held demonstrations against it and barred AMIS troops from entering.[131] Currently, much of this hostility is due to the view of many people in Darfur that AMIS is a key implementer of the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA), which they see as flawed. However, criticism began even before the DPA and was largely due to AMIS's inadequate resources to carry out a civilian protection mandate that was given a less-than-robust interpretation.

AMIS troops are deployed in permanent camps in all three Darfur states. They have a mandate to patrol the region and protect civilians and humanitarian operations from imminent danger. AMIS also provides armed escorts to humanitarian agencies on request. However, AMIS is a small force of some 7,000 peacekeepers that is not properly equipped with adequate material and human resources to carry out its protection mandate in such a vast, rugged, and hostile region. It has had no attack helicopters, which are necessary for rapid response activities, such as conducting real-time surveillance, immediate ceasefire violation investigations, and search and rescue missions. Armored personnel carriers provided by Canada were blocked from entering the country for months by the Government of Sudan. Equipment for nighttime activities has largely been absent. There has also been a persistent lack of interpreters and experienced female staff to address issues of sexual and gender-based violence. AMIS's various elements-military observers, protection force, and police-do not always share information and lack intelligence gathering technology and analysis techniques. These inadequacies have also left AMIS unable to defend itself. Between January and July 2007, AMIS lost 11 personnel to armed attacks and several of its vehicles were ambushed and hijacked.[132]

The African force's mandate states that AMIS should protect civilians "under imminent threat and in the immediate vicinity" and within its "resources and capability." While resources appear to have been the critical factor in AMIS's response to civilian protection needs, the loose language may have also camouflaged a lack of political will to undertake robust operations that might result in peacekeeping casualties. Additionally, AMIS's Rules of Engagement and Standard Operating Procedures-which provide commanders and troops guidance on how and when to use force-were unclear. In May 2006 the DPA outlined more detailed responsibilities for AMIS to undertake, which caused additional confusion.

In 2005 NGOs lobbied AMIS to conduct "firewood" patrols to reduce sexual violence against women and girls traveling outside camps to collect wood, hay, and water, and to farm. In some areas women welcomed the troops and believed they did help reduce sexual violence. However, in many instances, these and other patrols were cancelled because AMIS had too few armed soldiers, or gaps existed between the time when one group of soldiers left their duty station and their replacements were operational. In other instances the patrols have failed since people distrust AMIS because its patrols are accompanied by the much-distrusted Sudanese police, and because they believe that the patrols merely displace, rather than prevent, violence.

The civilian police component of AMIS was given the crucial role of monitoring Sudan's police force, investigating conflict related crimes, and conducting capacity building activities to help strengthen the police. AMIS police have no powers of arrest and are not mandated to serve as a domestic policing force. It too was plagued by insufficient personnel, including a limited number of female staff with expertise in sexual and gender-based violence and too few interpreters. AMIS police also failed to communicate effectively with the people they were mandated to serve. According to analysts, displaced persons, and international workers AMIS police are often inexperienced and ill-prepared, not trained in the laws of Sudan and international policing standards, suffered from an inability to work with international humanitarian and human rights groups, and failed to report on police misconduct. People living in camps also accuse AMIS police of commingling too closely with the Sudanese police and not exerting enough pressure on the government to improve their practices.

Along with a protection force and police, AMIS also has military observers to monitor the ceasefire agreements. The 2004 N'Djamena ceasefire commission that the observers fed into was active at first, but made little progress in the run up to the signing of the Darfur Peace Agreement, which established a new ceasefire commission. The new commission has not yet addressed many substantive issues, but became bogged down in debates over the government's refusal to allow non-signatories to join the commission and the insistence by non-signatory rebels that the commission judges them only on commitments of the 2004 ceasefire agreement that they signed.

Given the task before it and the limited resources available, AMIS was handicapped from the beginning in its efforts to meet the expectations of the population of Darfur. AMIS, however, also contributed to the distrust and in some cases hostility of Darfurians though its own actions. Consequently, many displaced persons have been altogether dismissive of AMIS even when it offers services that could improve the security situation. The fact that AMIS was tasked with helping to implement the DPA worsened its already tarnished image with the large number of Darfurians who did not support the DPA.

The Future of UNAMID

UNAMID may have up to 26,000 military and police peacekeepers, which should improve matters, but the challenges will remain enormous. The lessons learned from AMIS demonstrate that boots alone will not be enough to ensure UNAMID's ability to carry out its civilian protection mandate.[133] UNAMID will need to be widely and strategically dispersed throughout Darfur, have strong rapid response capabilities, carry out regular daytime and nighttime patrols-including firewood and market day patrols-employ well trained and well resourced policing units, and contain human rights officers who can publicly report on their findings. UNAMID should have a large number of staff who are experts in sexual and gender-based violence, as well as children's rights. UNAMID should also be equipped to provide a safe environment for humanitarians to work in.

Geographic coverage

Similar to AMIS, UNAMID should be widely and strategically dispersed in stations throughout Darfur, so that its forces have access to the civilian population and to especially volatile areas. Wide deployment to remote rural areas also acts as a deterrent for attacks and is necessary for increasing the potential for people to move more freely and for displaced persons to return home. It will take considerable time to complete permanent bases for the large force and even then there will be a number of areas with no permanent base. Peacekeepers should therefore be equipped and authorized to deploy to temporary bases for short- and medium-length stays. These peacekeepers, which will include military observers, armed soldiers, and police, will need to be mobile, with the ability to travel outside these temporary or permanent bases. A sufficient number of land vehicles and aircraft, including helicopters, will be needed since traveling through Darfur by road is always difficult and can be all but impossible in the rainy season.

Rapid response capabilities

UNAMID must have strong rapid response capabilities-much stronger than ever achieved by AMIS-that could include carrying out reconnaissance missions, placing peacekeepers in positions to protect civilians prior to expected attacks, providing armed protection to civilians who come under attack, conducting search and rescue missions if humanitarian or other convoys are hijacked, or investigating ceasefire violations immediately after they occur. This will require sufficient personnel, attack helicopters and APCs, and real-time and accurate information gathering and analysis technology. They must also have the capacity and equipment to carry out rapid response activities after dark and in the early morning. UNAMID's police, military observers, protection forces, and other relevant actors will need to establish effective lines of communication and share information for all these resources to be utilized effectively.

Day and night patrols