"Still critical"

Prospects in 2005 for Internally Displaced Kurds in Turkey

The soldiers emptied our village on a cold day in November 1993. They not only burned the place but fired on it with artillery. There were one hundred and ten families and now there are just fifteen people there. Now it still is not safe. I have been deprived of my home and my productive life for ten years. We received no assistance from the state to return. Now we want to be compensated. We villagers are open to negotiation. We are not taking these actions out of enmity. We worked out a project for the re-establishment of the village, including reconstruction of the houses, a health centre, a school. For all this we need infrastructure – a sewage system for example. People will laugh at this – a village in the southeast hoping for a sewage system – but the state should provide these basics.

-Villager from Kırkpınar, near Dicle, Diyarbakır province, interviewed in Diyarbakır, November 25, 2004

Summary

On December 17, 2004, the European Union (E.U.) decided that Turkey should continue to the next stage of its application to join the union by setting a date for the start of formal negotiations for full membership. An impressive track record of human rights reforms-including the abolition of the death penalty, new protections against torture, greater freedom of expression, and increased respect for minorities-prompted the positive decision. Unfortunately the reforms did not help the 378,335 people who were internally displaced in Turkey during the 1990s.

In May 2003, the E.U.'s Accession Partnership with Turkey required "the return of internally displaced persons to their original settlements should be supported and speeded up." Almost two years later, the Turkish government's performance remains poor. The 2004 European Commission Regular Report on Turkey's progress observed that: "[t]he programme for the return to villages proceeds at a very slow pace. Serious efforts are needed to address the problems of internally displaced persons" and warned that their situation is "still critical."[1]

In place of policy or program achievements for internally displaced people (IDPs), the Turkish government supplied the E.U. with statistics suggesting that returns are proceeding at a regular pace. If a third of the displaced had returned to their homes, as the government claimed, this would be a respectable performance. In fact, progress has been much more limited. Human Rights Watch has compared some of the government statistics with the situation on the ground. Our analysis found that the official statistics are not entirely reliable, and that permanent returns are running at a much lower rate than indicated.

The practical obstacles to return remain: villagers are slow to return because their homes and villages have been destroyed and the security situation in the remote countryside remains precarious. Many of the villagers who return live in primitive shelters located in settlements without electricity, telephone, education, or health facilities. Assistance with reconstruction and support in re-establishing agriculture is minimal or non-existent.

Village guards-paramilitaries, usually Kurdish, armed and paid by the government to fight the PKK (Kurdish Workers' Party, now known as Kongra Gel)-have not been disarmed, and are implicated in attacks on returning IDPs. Regular security forces have also committed extrajudicial executions of IDPs.

Current conditions in Turkey do not permit the return of internally displaced persons "in safety and with dignity," in accordance with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (U.N. Guiding Principles).

There are signs that the Turkish government is preparing to take a new and more constructive approach toward the return of IDPs. The government has announced plans to establish an agency to reshape the failed Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project and disarm the village guard corps. It has begun, tentatively, to share its work on IDPs with intergovernmental organizations, and in response the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has submitted a modest plan to collaborate with the Turkish government in meeting the needs of IDPs. The July 2004 Compensation Law adopted by the Turkish Parliament may provide some restitution for the losses suffered as a result of the scorched earth policy implemented in the southeast during the 1990s, although obstacles to its success are already emerging.

However, these are untried initiatives, and with the exception of the Compensation Law, not past the planning stage. The past decade is littered with widely-touted initiatives for IDPs that were starved of funds, lacked political commitment, and were eventually discarded. If the government's new approach is to count for something, it needs to move quickly to operationalize plans for the government IDP agency and approve and implement the UNDP project. Success will also depend upon close scrutiny by the international community throughout 2005 to keep the government on track and avoid a repeat of earlier failures.

Recommendations

To the Turkish government:

Government Agency for Internally Displaced Persons

·Promptly establish the proposed government agency for IDPs. This body should:

-publish a clear statement of government policy vis-à-vis IDPs;

-prepare a timetable for the return process;

-clarify government commitments to provide infrastructure to returnee communities, including electricity, water, sanitation, telephone connection, road access and access to health care and education;

-ensure that adequate resources are available to ensure that all returning families have sufficient building materials to establish warm, and dry accommodation; and,

-publish detailed budget provisions to cover payments under the Compensation Law, infrastructure reconstruction, income support for returning villagers, and support for the integration of IDPs who choose to remain in the cities.

Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project

·Begin immediate reform of the Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project. This reform need not await the findings of the Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies, but may benefit from the data emerging during the course of the study.

Village Guard Corps

·Develop a comprehensive plan and timetable for disarming and demobilizing the village guards corps.

UNDP project

·Approve the UNDP project for the support of IDPs, and ensure its swift implementation.

Compensation Law

·Enhance the independence of Compensation Law assessment commissions, and ensure their work is timely, fair, and consistent.

·In order to ensure that those who have relevant information are willing to come forward, Commissions should undertake not to disclose the identity of witnesses or the content of their evidence to other government agencies where witnesses have asked for these details to be withheld, and should make arrangements to safeguard anonymity in commission hearings where witnesses request this. Commissions should also undertake to investigate thoroughly any reports of intimidation of, or reprisals against, witnesses or proposed witnesses, and refer evidence of any abuses to the judicial authorities.

·Create an independent appeals body to review decisions by Compensation Law assessment commissions.

·Ensure that sufficient funds are provided to meet payments under the Compensation Law.

·Conduct a review of the operation of the law in mid-2005 after provincial assessment commissions have processed an initial group of applications.

Persons who remain displaced

·Ensure that those villagers who cannot return due to the continuing risks posed by the armed activities of Kongra Gel, or other illegal armed organizations, receive support, access to medical care and compensation, in accordance with the U.N. Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement

To the European Union and its Member States:

·Task the European Commission Delegation to Ankara withmonitoring the new government agency for IDPs, to ensure that its work is in conformity with the recommendations of the The United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary General for Internally Displaced Persons (SRSG) on internally displaced persons and the U.N. Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. The delegation should provide an evaluation of reform to the Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project in mid-2005 for inclusion in the next regular report on Turkey.

·Task the European Commission Delegation to Ankara with monitoring the operation and working methods of Compensation Law assessment commissions. The delegation should provide an evaluation on the work of the assessment commissions in mid-2005 for inclusion in the next regular report on Turkey.

·Ensure that the revised Accession Partnership planned for mid-2005 continues E.U. scrutiny and support for the return and integration of IDPs.

·Urge the Turkish government to ensure that the work of the Compensation Law assessment commissions is timely, fair, and consistent.

·Consider funding directly projects for return of IDPs and support of the integration of IDPs in cities.

To the United Nations Country Team in Turkey:

·Monitor the new government agency for IDPs to ensure that its work is in conformity with the recommendations of the SRSG on internally displaced persons and the UN Guiding Principles, and provide an evaluation in mid-2005 on reform of the Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project to donor governments and the Turkish authorities.

Introduction

Security forces in Turkey forcibly displaced Kurdish rural communities during the 1980s and 1990s in order to combat the Kurdish Workers' Party (PKK) insurgency, which drew its membership and logistical support from the local peasant population. Turkish security forces did not distinguish the armed militants they were pursuing from the civilian population they were supposed to be protecting. That failure can in part be explained by the fact that Turkish security forces knew that the civilian population included people who were supplying and hiding the militants, willingly or unwillingly. The local gendarmerie (soldiers who police rural areas) required villages to show their loyalty by forming platoons of "provisional village guards," armed, paid, and supervised by the local gendarmerie post. Villagers were faced with a frightening dilemma. They could become village guards and risk being attacked by the PKK or refuse and be forcibly evacuated from their communities.

Evacuations were unlawful and violent. Security forces would surround a village using helicopters, armored vehicles, troops, and village guards, and burn stored produce, agricultural equipment, crops, orchards, forests, and livestock. They set fire to houses, often giving the inhabitants no opportunity to retrieve their possessions. During the course of such operations, security forces frequently abused and humiliated villagers, stole their property and cash, and ill-treated or tortured them before herding them onto the roads and away from their former homes. The operations were marked by scores of "disappearances" and extrajudicial executions. By the mid-1990s, more than 3,000 villages had been virtually wiped from the map, and, according to official figures, 378,335 Kurdish villagers had been displaced and left homeless.

In the intervening decade, Turkey has embarked on a convincing program of human rights reform which has been internationally recognized and welcomed. However, that reform has not yet significantly benefited IDPs in Turkey. Most are in much the same situation as they were a decade ago: still displaced and living in harsh conditions in cities throughout the country. Declining political violence has improved security in the region, but in many areas the countryside is still not safe, and certainly not welcoming. Government assistance for return continues to be arbitrary, lacking in transparency, inconsistent, and insufficient.

In 2004, the Turkish government announced three initiatives to assist the displaced: the creation of a government agency with special responsibility for IDPs; a project for IDPs to be jointly undertaken by UNDP and the Turkish government; and the Law on Compensation for Damage Arising from Terror and Combatting Terror (Law 5233 – "Compensation Law"). While the measures look like positive steps, past experience suggests caution. Earlier return schemes, introduced over the last decade, have fallen short of the claims the government made for them.[2]

As of February 2005, the government had not established the proposed IDP agency, had not approved the UNDP project, and had made no rulings under the Compensation Law. After a decade of disappointments, IDPs and the nongovernmental organizations concerned with their plight, are keen that these initiatives are implemented promptly and fairly, and that they are accorded sufficient political support and funding to make a serious impact on the problem.

Turkish government efforts to resolve the situation of IDPs are coming under increasing international scrutiny. The SRSG visited Turkey in May 2002, and submitted a series of recommendations to the Turkish government in November of that year.[3] In May 2003, the E.U. revised its Accession Partnership with Turkey to include a requirement that "the return of internally displaced persons to their original settlements should be supported and speeded up."[4] In June 2004, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe recommended that the government should "move from a dialogue to a formal partnership with U.N. agencies to work for a return in safety and dignity of those internally displaced by the conflict in the 1990s."[5]

International attention to Turkey's IDP problem has worked to the extent that it has persuaded the Turkish state to share its plans with the United Nations, European Union and other intergovernmental organizations, and to acknowledge the standards embodied in the U.N. Guiding Principles in developing those plans. But the pressure also seems to have led the government to present an over-optimistic picture of the progress on return. It has taken ten years to focus international attention on internal displacement in Turkey, and it would be disappointing if that attention were to waver because of official statistics suggesting that the problem is well on the way to a resolution. It is not.

Obstacles to Return

Destruction of Infrastructure

The violence that was used during the forced evacuation of the villages, coupled with a decade of neglect, means that villagers face return to near wilderness punctuated with piles of stones where their homes once stood. Their fields are overgrown, and their pasture turned to ungrazeable scrub. Many villages in the former conflict areas have no telephone connection, no electricity supply, no school, no health centre, no water or sanitation system, and often no passable road.

Civil servants sometimes cite the extremely primitive conditions in some villages to argue that the settlements are fundamentally and intrinsically non-viable, but it is important to note that fifteen years ago, prior to their destruction, the villages had electricity and telephone connections. In most cases, road access deteriorated as a result of a decade of neglect. Most villages also had ready access to schools before the late 1980s, when the PKK began its policy of killing teachers, and the state began destroying school buildings and other infrastructure.

Most villagers were not rich, even at the beginning of the 1990s. But they were impoverished by the wholesale destruction at the point of evacuation, and grew poorer still during ten years in internal exile. Today, most of the displaced lack the resources to properly resume their previous lives as farmers and stockbreeders. For return to be viable, displaced villagers need the ruined infrastructure of their communities restored, assistance with rebuilding their homes, and support during the transition stage while they are re-establishing their livelihoods.

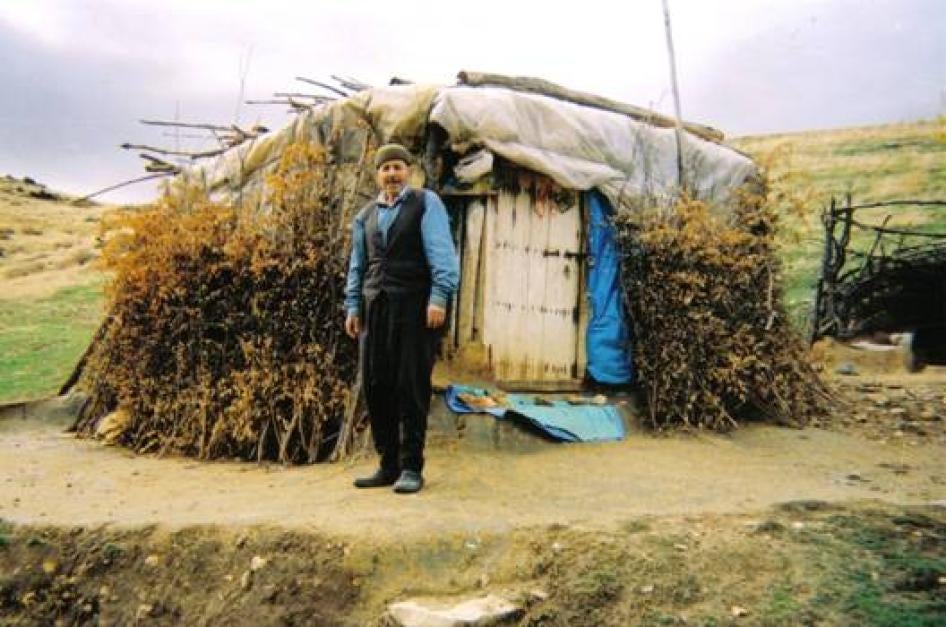

Recently returned villager in front of a makeshift shelter. Security forces destroyed his home and the rest of the village in Diyarbakir province in 1992. (c) 2004 Jonathan Sugden/Human Rights Watch

The challenges were illustrated starkly during a November 2004 visit by Human Rights Watch to Koçbaba village, near Hazro ın Diyarbakır province. The village lacks the basic elements needed to be a viable community. The population of Koçbaba consists almost entirely of ageing villagers because, in the absence of a local school, families with children have to stay in Diyarbakır. Several elderly villagers were living in huts constructed of branches and plastic. The average nightly temperature during January in Diyarbakir province is consistently below freezing.

Apart from an earth road and a stream, infrastructure at Koçbaba was non-existent. Koçbaba inhabitants described a deadlock over the village's telephone and electricity connection, since the governor and suppliers expected the villagers to erect the poles to carry the supply, whereas the villagers felt that this was not their job since they had not destroyed them.

Destruction of housing and infrastructure was total for most cleared villages, but the degree of current recovery varies considerably. Recovery depends on the natural advantages of the village, including its proximity to a road, the energy of its village muhtar[6]and his relationship with the sub-governor. The reconstruction and re-opening of the village school seems to be a determining factor. In villages with access to schooling, the population seems much more likely to stay the whole year round and include residents across the range of ages. Çiftlibahçe village, near Hazro, Diyarbakır province, for example, is clearly thriving with high morale and plenty of youngsters around. The village school had been destroyed during the forced evacuation, but a new school building has been constructed with funds provided by Galatasaray, one of Istanbul's leading football (soccer) clubs.

Insecurity in Areas of Return

Security is a crucial factor in returns. There would be no returns at all if personal security in the rural areas of southeast Turkey had not improved much in recent years. All villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch affirmed that the atmosphere was much less tense attributable to the decline in political violence, although the degree of improvement varies from province to province, and from district to district. Returning villagers told Human Rights Watch that their villages are no longer being visited by armed militants looking for food and recruits, and that relations with the local gendarmerie have improved. While some mentioned harsh words and threats from the military, most indicated that the routine brutality of the past had, in general, been replaced by a level of tolerance and respect.

It is important to emphasize that the relative improvement in personal security mentioned by returned villagers will evaporate very quickly if there is a return to open conflict in the region. It was the PKK's exploitation of Kurdish villagers for food, money, and recruits that made those villagers, in turn, targets of state persecution. Kongra Gel's return to armed activities in June 2004 risks provoking a heavy-handed government response that may harm Kurds and derail the whole process of return. That risk was identified by the nongovernmental organization Göç-Der[7] in an October 2004 report examining the situation of the displaced. The report urged Kongra Gel to renew its unilateral ceasefire and pursue peaceful means in the interests of the displaced.[8]

Village Guard System

The continuing presence of village guards in some communities constitutes a major impediment to improved security and confidence among displaced villagers. This in turn has a major impact on their willingness to return. In Sirnak province, for example, where the village guard system is particularly strong, the government's own statistics indicate that returns are running at less than half the rate of the best-performing province.

Displaced persons are understandably reluctant to return to remote rural areas where their neighbors, sometimes from a rival clan, are licensed to carry arms, as members of the village guard.[9] Many villagers were originally displaced precisely because they refused to become village guards. Most village guards, like the displaced, are Kurds. As of August 2004, there were 58,416 village guards in Turkey.[10] Village guards were involved in the original displacement, and in the intervening years have continued to commit extrajudicial executions and abductions. In some cases, village guards are now occupying properties from which villagers were forcibly evicted. They are sometimes prepared to use violence to protect their illegal gains. The failure of successive Turkish governments to hold accountable members of the security forces and village guard for abuses has created a climate of impunity.

In 2002, village guards allegedly killed three villagers who returned to Nureddin village, in Muş province.[11] In June 2004, village guards were implicated in killing of five villagers in pastures near Akpazar village, near Diyadin, in Ağrı province.[12] On September 25, 2004, a village guard in Tellikaya village in Diyarbakır province allegedly shot and killed Mustafa Koyun, a returnee villager.[13] On or about October 7, 2004, villager İshak Tekin was wounded in an attack by village guards at his home in the settlement of Axçana, near Varto in Muş province.[14] He was shot at close quarters, and lost an eye in the attack.

The October 6, 2004 European Commission Regular Report on Turkey describes the village guard system as one of the "major outstanding obstacles" to the safe return of IDPs. There have been repeated calls for the abolition of the village guard system both inside and outside Turkey. Those recommending the abolition of the system include: the Turkish Grand National Assembly's parliamentary commission on political killings in its 1995 report, the Turkish Grand National Assembly's parliamentary commission on internal migration in its 1998 report, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions in her 2002 report on her visit to Turkey, the UN Special Representative on Internal Displacement in his 2002 report on his visit to Turkey, and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in its resolution on Turkey of June 2004. Returns will continue to be slow unless and until the village guard system is dismantled and its members disarmed.

Unlawful Killings by Security Forces

In addition to security concerns arising from the village guard system, attacks on civilians by the gendarmerie discourage return. Three unlawful killings by security forces in late 2004, underscored the continued potential for lethal state violence against civilians in general, and IDPs in particular.

On November 21, security forces shot dead Ahmet Kaymaz, a villager displaced from Köprülü village in Mardin province, and his twelve-year-old son Uğur Kaymaz in the nearby town of Kızıltepe.[15] Neighbors told the Human Rights Association of Turkey (HRA) that Kaymaz and his son had been preparing their commercial vehicle for a forthcoming journey and were unarmed at the time of the shooting. The provincial governor issued a statement that "two terrorists have been captured dead following a clash."[16] An HRA delegation investigated the incident and concluded that there was little evidence to suggest that Kaymaz and his son had been involved in an armed clash with security forces, as the official incident report claims. The HRA noted that since Kaymaz was a full-time truck driver and that his son had an uninterrupted attendance record at his local primary school, they were unlikely to be members of any guerrilla force. Kaymaz had recently appointed a lawyer to deal with his application for compensation for his displacement, and the autopsy report noted that related documents were on his person at the time of death.

A week after the Kaymaz killings, on November 28, gendarmes shot dead Fevzi Can, a shepherd who resided in the partially evacuated village of Ortaklar, in Şemdinli, Hakkari province.[17] A local newspaper reported claims by Fevzi Can's uncle that the military authorities had taken the body away and refused to release it unless Can's relatives signed a statement saying that "a terrorist who failed to respond to a call to halt was killed."[18] Official statements described Can as a livestock smuggler[19] but the village muhtar and Fevzi Can's brother denied this, and pointed out that the animals in his possession had not been confiscated by the authorities, as is usual in smuggling cases, following Fevzi Can's death. Efforts to coerce the relatives and conflicting stories about "terrorism" and "livestock smuggling" have provoked suspicions that this was an unlawful killing.

Four members of the Turkish Army Special Operations Team were indicted in December 2004 by the Mardin Chief Prosecutor's Office for the killings of Ahmet and Uğur Kaymaz. The first hearing was held on February 12 at Mardin Criminal Court No. 2. The trial continues.An investigation has been opened against gendarmes thought to be responsible for the death of Fevzi Can. Prosecutions in southeast Turkey for similar crimes in the past have rarely resulted in convictions, giving cause for scepticism about whether those responsible for these offences will be held to account.

The discovery on November 4, 2004, of a common grave containing the bones of eleven people in the Kepre district of Alaca village has renewed awareness of the region's history of violence and impunity. DNA samples are currently being tested, but clothing and objects indicate that the remains belong to eleven villagers detained by soldiers and "disappeared" at the time of the forced evacuation and destruction of Alaca in 1993.[20] In 2001, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) found the Turkish government responsible for violations of the right to life in respect of the eleven men. In its judgment, the Court was "struck by the lack of any meaningful effort" by public prosecutors to investigate the "disappearances" at Alaca.[21] Villagers told the court that commandos from Bolu took the villagers away, but no soldiers from that unit were indicted.

According to the U.N. Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-Legal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions, killings such as those described above should be investigated by independent expert commissions.[22] The Turkish authorities have consistently resisted this route, preferring to leave the job to the public prosecution service that, over the past two decades, has proven itself either unable or unwilling to hold the members of the security forces to account.

Unless the Turkish government radically alters the manner in which allegations of killings by the security services and the village guard are investigated, and the perpetrators brought to account, impunity will continue, and many internally displaced will lack the confidence to return to their homes.

Assessing the Scale of the Problem

Unreliable Government Figures on Return

Accurate and detailed statistics about movements of IDPs are a precondition for the Turkish government to begin planning how it can meet its obligations and commitments in relation to the internally displaced, and for the outside world to evaluate what is being done. For years, government figures have been increasingly upbeat but also contradictory and inconsistent. Moreover, because they never listed the settlements to which villagers returned, the statistics were impossible to verify.

In 1999, the government commissioned the Turkish Social Sciences Association to carry out a large survey of the displaced. After four years, the survey failed to produce statistics on the overall scale of displacement or the rate of return. Independent efforts to develop statistics have been unwelcome. In 2001, for example, the central government blocked an attempt by Diyarbakır municipality to collect reliable data about the number, conditions, and aspirations of the displaced.[23] The authorities prosecuted the organization Göç-Der for publishing a similar survey in April 2002, and in January 2004, as publisher of the report, Göç-Der director Şefika Gürbüz was sentenced to ten months' imprisonment (converted to a fine) for "incitement" under article 312 of the Turkish criminal code.

The European Commission's October 6, 2004 Regular Report on Turkey stated that the Turkish government had provided information that "since January 2003, 124,218 IDPs (approximately one third of the official total of 350,000) have returned to their villages."[24] Surprised at this unexpectedly brisk rate of return, Human Rights Watch visited the Turkish Embassy in Brussels on October 7, 2004, and requested a breakdown of the statistics provided to the European Commission, in order to evaluate their accuracy. On November 25, 2004, the Turkish Foreign Ministry supplied a list of villages and hamlets to Human Rights Watch with columns for pre- and post-displacement populations. Human Rights Watch wrote to the government formally on December 8, 2004, to welcome the list, which contains the first detailed and verifiable data about the return process.

In late November 2004, Human Rights Watch visited a small sample of the villages and hamlets listed, to compare the official numbers of pre-displacement and returned populations with figures given by village inhabitants. Human Rights Watch also looked at returnees' conditions, and the extent of official support to individual returnees and communities.

Our evaluation indicated that the government's return figures are not accurate, and identified two particular shortcomings. First, the statistics under-record the number of inhabitants in communities prior to displacement and therefore underestimate the scale of the displacement. Second, the statistics overstate the number of returnees. In some settlements, the government list reports substantial numbers of returns that were either temporary, or did not take place at all.

Under-recording Initial Displacement

Nobody knows for sure how many people were displaced in the 1990s. In 1998, the governor of the south eastern provinces-then under state of emergency-stated that 378,335 villagers had been displaced from 820 villages and 2,345 smaller settlements.[25] The Turkish government rounded this down to 350,000 in the figures supplied to the European Commission for the 2004 Regular Report. The U.S. State Department report for 1998 considered 560,000 a credible estimate.[26] The Diyarbakır Bar Association suggests that as many as two million may have been displaced.[27] At any rate, the estimate of 377,882 derived from provincial displacement figures is almost certainly too low.

In almost every case, inhabitants of villages and village muhtars interviewed by Human Rights gave a much higher figure for the number of inhabitants at the time of displacement than was indicated in the government list.[28] The following are some examples of such discrepancies:

·Çalışkan village in Gercüş, Batman province, is recorded in the government list with twenty-two households prior to displacement, whereas local sources assert that there were one hundred and forty households.[29]

·Dereli village in Gercüş, Batman province. According to the government list: twenty-two households; according to local sources: one hundred and forty households.

·Gündüz village in Kozluk, Batman province. According to the government list: eighteen households; according to local sources: forty-six households.

·Şeman hamlet of Beşkonak village in Kozluk, Batman province. According to the government list: five households; according to local sources: thirty-five households.

·Sağgöze in Genç, Bingöl province. According to the government list: 133 households; according to local sources:three hundred households.[30]

·Kurşunlu village in Dicle, Diyarbakır province. According to the government list: thirty-eight households; according to local sources: at least one hundred and twenty households.[31]

·Kırkpınar village in Dicle, Diyarbakır province. According to the government list: sixty-four households; according to local sources: one hundred and ten households.

·Kayaş hamlet of Kırkpınar village in Dicle, Diyarbakır province. According to the government list: ten households; according to local sources: twenty-five households.

·Küpetaşı hamlet of Kırkpınar village in Dicle, Diyarbakır province. According to the government list: eight households; according to local sources: twenty households.

Local inhabitants interviewed by Human Rights Watch agreed that the government figures for Laleyran, Valdere, and Vankom hamlets of Kırkpınar were correct. It is difficult to account for the discrepancy between official statistics and local estimates in such a large number of cases. There is no reason why villagers and muhtars should exaggerate the predisplacement figure. They are relying on memory, but insisted that their accounts of pre-displacement figures were correct and could be verified by records of electricity supplies in the year of the displacement.

In some cases, settlements whose populations were displaced were omitted from the government list altogether. The Bismil district section of a 2003 survey carried out by the Diyarbakır branch of Göç-Der gives details of temporary and permanent returns to twenty-six evacuated settlements.[32] The government list shows only seventeen such settlements. The Göç-Der list for Silvan district shows twenty-six evacuated settlements while the government list shows twenty-two.

Other examples of villages that were forcibly evacuated but which do not appear on the list include: Erenköy village, near Eruh in Siirt province, where there were approximately one hundred households prior to displacement, and Çölköy village, near Eruh in Siirt province, where there were approximately fifty households prior to displacement. Both villages are now reportedly occupied by village guards.[33] In Hakkari central district, further examples of villages evacuated but not included in the government list include the villages of Ağaçdibi, Akkuş, Baykoy, Boybeyi, Demirtaş, Doğanyurt, Geçimli and its four hamlets. The town of Uzundere and its associated villages of Alkan, Çiftkonak and Haydaran in Hakkari were evacuated in 1995, and formally abolished on December 30, 1998, and therefore do not appear on the government list.[34]

Some villages are not included in the list because they occurred in provinces outside the emergency zone, including for example, Yastık village, near Tercan, Erzincan province and which was evacuated and bulldozed flat in 1994, together with its hamlets Kurubey and Mazan.[35]

The failure to correctly record settlements on government records as having been evacuated was identified as a problem as early as 1998. In that year, Orhan Veli Yıldırım, parliamentary deputy for Tunceli province, informed the Turkish Parliamentary Migration Commission that: "The official statistics on the number of evacuated villages are wrong. For example, Baylık village [in central Tunceli] is my own village and it is currently empty….it is shown as full. But it is empty. Çemçeli, another central village, is also supposed to be full, but that is empty also. Yeşilkaya is close to where the mayor [of Tunceli] comes from, and it is shown as full, but it is empty."[36] The three villages identified by Yıldırım in 1998 as having been wrongly recorded were not included on the government list of evacuated settlements.

Some villages are recorded as having had no inhabitants at all prior to displacement. In the case of Siirt province, the underrecording of the original population seriously distorts the picture for the province as a whole. Siirt suffered heavy displacement. Local sources indicate that the rate of permanent return has been low. Yet according to the government figures, 53.36 percent of the inhabitants have returned. The illusion of a respectable return rate derives from inaccurate government statistics. The government list shows returns to the following villages in Siirt with a zero population prior to displacement:

- Central district: Aktaş.

- Baykan district: Çevrimtepe/Ulukapı.

- Eruh district: Bilgili; Cintepe; Çizmeli; Dağdöşü; Dikboğaz; Kekliktepe/Karabıyık; Üzümlü; Yanılmaz; Yelkesen; Yokuşlu.

- Kurtalan district: Karabağ; Uluköy.

- Pervari district: Aşağıbağcılar; Ayvalıbağ; Belemoluk; Beğendik; Çatköyü; Çavuşlu; Çobanören; Çukurköy; Doğanköy; Dolusalkım; Düğüncüler; Ekindüze; Gümüşören; Güleçler; Gölgeli, Gökbudak; Karasüngür; Kocaçavuş; Köprüçay; Köprüçay/Yenimahalle; Merkez; Narsuyu; Okçular; Ormandalı; Sarıdam; Söğütönü; Taşdibek; Tuzcular; Yapraktepe; Yeniaydın;Yukarıbağcılar.

- Şirvan district: Demirkapı; Kömürlü/Yelken; Özyurt; Suluyazı; Yedikapı.

These settlements account for a total of 1,111 households and 7,249 individuals within the return figure. The failure to include the populations of these villages in the total pre-displacement population in Siirt province, creates a misleading impression about the rate of the return in the province. When this error is discounted, the average return rate for Siirt falls to 29.76 percent even before other patterns of inaccuracy noted in this evaluation are taken into account. The figures for Bingöl show the same form of inaccuracy, listing several villages as having had zero population prior to displacement. For example, Yeniyazi village in Bingöl province is shown on the government list as having no inhabitants prior to displacement, and yet 487 inhabitants are shown as having returned there.

Over-recording the Number of Returns

In some settlements, the government statistics show substantial numbers of returns that upon inquiry by Human Rights Watch appear either to be significant overestimates, or to include returns that were only temporary.

On November 18, Human Rights Watch visited Koçbaba village, near Hazro in Diyarbakır province. The government list indicates that there are currently twenty-seven households with 278 inhabitants. Human Rights Watch counted thirteen households with a total population of just sixty-nine. In the nearby village of Çiftlibahçe, by contrast, the government list figure of forty-nine households returned was accurate.

Some interviews with local displaced inhabitants produced figures which differ widely from the government list. A former muhtar of Yolaçtı village near Genç in Bingöl province, and now living in Genç, reported that his village currently has eleven households with approximately fifty inhabitants, whereas the government list shows ninety-nine households with 449 inhabitants.[37] A former inhabitant of Yeniyazı village told Human Rights Watch that eight families have returned, whereas the government list indicates that sixty families have returned.[38]

According to official government figures, in Duru village in Lice, Diyarbakır province, there are now 207 households comprising 346 inhabitants, but two displaced former inhabitants of Duru told Human Rights Watch that there are currently fewer than ten households living in the village.[39] According to the government list, there are sixteen households at Dibek, Lice, whereas an inhabitant of a neighboring villager interviewed by Human Rights Watch strongly asserted that there are no permanent dwellings in Dibek and no families living there year-round.[40]

According to the Siirt branch of the Human Rights Association (HRA), the figures for Siirt province are accurate for some villages, but seriously inaccurate for others. Siirt HRA provided the following examples from the Eruh district: in Yerliçoban village, government statistics indicate that there are sixty-eight households but to the HRA's knowledge there are fewer than twenty; in Ballıkavak village, the government list states that there are twenty-two households but the HRA reports that only two houses in the village are occupied; in Yorulmaz village, the government list states there are fourteen households but the HRA indicates that the village has no permanent residents.[41]

According to the Muş branch of the HRA, the government list records significant returns in several communities where there are no permanent returns and currently no permanent residents at all, including: Yongalı, where the government records the return of eighty-four households with a population of 500; Ilıca where the list records the return of thirteen households with a population of seventy-six; and Demirci, in Korkut, where the list records the return of thirty-two households with a population of 213.[42]

According to the Bingöl branch of the HRA, fifteen households have returned to Inandık village, near Solhan in Bingöl province, while the government list records forty-four households as having returned. The government list states that forty-two families have returned to the Aşağı Yayıklı and Yukarı Yayıklı hamlets of Mutluca village, but Bingöl HRA reports that no families have returned permanently.[43]

In some cases, the inhabitants of villages are shown as having returned when the villages have in fact been occupied by other communities, often members of the village guard. Çizmeli village in Siirt province, for example, is shown on the government list with thirty-two households and 230 villagers, while Siirt HRA report that the village is occupied by village guards who lease the lands to migrant livestock herders.

The government list also inflates the rate of return by including villages that were never evacuated. These entries generally relate to communities that joined the village guard corps. For example, according to Vetha Aydın, president of Siirt Human Rights Association, the villages of Otluk, Yayladağ, and Meşecik near Şırvan, and Karasüngür near Pervari were never evacuated. On the government list the entire population of these villages is shown as having been evacuated and successfully returned. According to Bingöl HRA, the villages of Esmataş and Kırık were never evacuated. These also appear on the government list as having been evacuated and repopulated.

At present, official government statistics do not give a reliable picture either of the original displacement or the current state of returns. The Turkish government's claim that a third of the displaced are now back in their homes is based on inaccurate figures. It presents an over-optimistic picture that is not warranted by facts on the ground.

Improving the Quality and Accuracy of Return Statistics

The Turkish Foreign Ministry informed Human Rights Watch in November 2004 that the State Planning Organization and Hacettepe University signed a contract on November 2, 2004, for a new IDP survey.[44] The university's Department of Population Studies will carry out the research. Human Rights Watch understands that the research will include an overall estimate of the number of the original displacement, generated using statistical methods, presumably from government data. If the current government list is used without efforts to verify its content with independent sources, it is likely to produce another underestimate.

It is essential that, at the very least, the list of settlements that suffered displacement is a full one. This can only be done by checking the existing list with local sources, including nongovernmental organizations working on displacement and municipalities. Many districts have local associations-such as the Association of People from Tunceli (Tuncelililer Derneği) and Kayy-Der (Kığı-Karakoçan-Adaklı-Yayladere-Yedisu Social Solidarity, Development and Culture Association)-which could also assist in developing an accurate list.

Even if the raw numbers contained in government statistics were correct, the mere fact that displaced persons have returned to their home communities provides insufficient information fully to evaluate the returns process. In order to properly evaluate the success of the return process, qualitative data is required. Specifically, information must be collected on the conditions in which returnees are living, the state of the infrastructure in return communities, and the levels and types of assistance provided to them by the state. Only then will it be possible for observers to determine whether or not returns are taking place "in safety and with dignity."

In particular, efforts must be made to assess whether those who return remain permanently in their villages. One reason for the wide discrepancy between the government list and local sources is that the government list has counted temporary summer returnees, who visit the village during the warm months in order to earn some money by raising a crop, and to live cheaply during the long school holiday. Several village leaders pointed out to Human Rights Watch that it is not possible to assess the success of the return process merely by comparing the number of those originally displaced with those who have returned, even if the figures were 100 percent accurate on the day of the count. A population count on August 1 might differ from a count on February 1 by a factor of ten or more. For example, according to the former muhtar of Yolçatı village in Bingöl, 90 percent of the village's six hundred inhabitants returned in the summer of 2004, most of them living in tents.[45] By November 2004, fewer than fifty people were living in the village.

Many IDPs now stay temporarily in their village during the long summer school holiday and return to urban areas during the winter, leaving a much smaller number of permanent residents. Villagers reported that the main reason for the winter exodus was not that they could not resist the attractions of city life, but that winter in an unrehabilitated village is unsustainable and dangerous. Many villages lack access to electricity and telephone services, water and sanitation systems, and are inaccessible by road for up to three months a year. They also lack medical facilities and, most importantly, schools. The fact that any villagers choose to remain in such villages over the winter reflects just how miserable conditions are for the displaced in urban areas.

Some argue that wide seasonal fluctuations indicate that villagers are abandoning village life in line with the general process of urbanization since 1950, and that villages are becoming mere summer residences. The individual motivations of villagers are difficult to assess, but many reported to Human Rights Watch that they had no choice but to return to the city at the end of the summer because they wanted to put the children in school. Furthermore, they could not afford to reconstruct their ruined houses in order to make them habitable during the extremely harsh winter months. The muhtar of Sağgöze village, near Genç, in Bingöl province said "I cannot speak for others, but I know that if our village was provided with water, a road, and a school, it would be completely full."[46]

Turkish Government Policy toward IDPs

The Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project

The Turkish government's current chosen vehicle for providing assistance to IDPs is the Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project. Successive governments have produced various return initiatives since 1995, all of them hobbled by a lack of fundıng and insufficient political drive.[47] These initiatives appear largely to have been motivated by a desire to create the impression of government action, in order to deflect questions from petitioning villagers, parliamentary deputies from the southeast, and foreign diplomats. The plans may also have served to relieve pressure on the government from metropolitan populations and municipalities concerned about the influx of peasants squatting on vacant land and erecting gecekondu (shanty dwellings).

In March 1999, then prime minister Bülent Ecevit launched the Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project with the following description: "Within the framework of the project, those families who wish to return to their villages will be identified; infrastructure facilities of the villages will be completed; housing developments will be increased with the labor of families; and social facilities will be completed to increase the standard of living of the local people, especially in [the areas of] health and education. Moreover, activities such as beekeeping, farming, animal husbandry, handicrafts and carpet weaving will be supported so that these families can earn a living."[48]

The Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project has now been running for almost six years. Human Rights Watch has long criticized its poor performance. In 2001 and 2002, Interior Ministry officials said that the government would expand and formalize assistance to returning displaced persons once a survey had been completed and a returns model established. The survey was finished in 2002, but no model for return was ever developed, and governors continue to dole out meagre assistance through the project on an ad hoc basis.

Between 1999 and 2002, the state allocated approximately U.S. $19 million to the scheme, but in the villages visited by Human Rights Watch, there was not much to show for the expenditure.

Returning residents in Koçbaba village had received no assistance for the reconstruction of their houses. At Seren village, situated by the main road in Hani, Diyarbakir, several villagers had reconstructed their homes, but they had paid for the work out of their own pockets. The village muhtar stated that many villagers had signed petitions for assistance under the Return to Village and Rehabilitation project "but shame upon them [the government], only three families received anything. They received seventy bags of cement each, and 500 kg of reinforcing steel. We are none of us rich, but these were the poorest of the families. I have made more than a hundred petitions for assistance [on behalf of villagers]."[49] The sub-governor of Hani told Human Rights Watch that he had applied to the Interior Ministry for urgent assistance for reconstruction, and hoped that this would be allocated soon.[50]

The former muhtar of Yolaçtı village and the muhtar of Sağgöze near Genç in Bingöl told Human Rights Watch that their villages had received no government reconstruction assistance.[51] Government assistance in the Genç district consisted of twenty bags of cement and a hundred tabaka (timber sheets) each to 250 families, but the government list indicates that 1,280 families have returned in that area.[52]

According to the Siirt Human Rights Association, villages in the Eruh district of Siirt province received no assistance for reconstruction. Villages in the Şırvan district have received some material assistance, but the amounts received by each villager were insufficient to rebuild a home.[53]

The Return to Village and Rehabilitation project has also failed to restore damaged and destroyed infrastructure in villages to which populations are returning. The Sağgözemuhtar stated that his village had no road, water, electricity, or school.[54] According to the former muhtar of Yeniyazı, and the muhtar of Büyükçağ near Genç in Bingöl, their villages still have no road.[55]

The Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project is supposed to provide income support to returnees. Yet such support has been sporadic and insufficient. In the village of Koçbaba, for example, returning residents arrived without livestock (sold at the time of displacement in 1991 in order to pay for accommodation and food) to find that their orchards had been burned annually until they died at the roots. Several villagers told Human Rights Watch that they could not afford to purchase any livestock.[56] They said that in 2003 the gendarmerie had distributed five kilos each of oil, sugar, and rice to each family on one occasion, and that in 2004 the local governor had distributed 150 NTL (approximately U.S. $113) to each family. The Koçbaba residents were grateful for the assistance, but regretted that it was much too little to meet their needs. No inhabitants from any other village interviewed by Human Rights Watch in November 2004 had benefited from income support grants, though several villagers were aware of other communities who had received assistance in the form of livestock or sapling trees.

Clearly, the Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project is not doing its job in its current form. The project is under-funded. There are no clear guidelines about what a community or a particular villager can expect. Assistance is distributed in an arbitrary and inconsistent manner. Work in repairing infrastructure has not even kept up with the existing slow rate of return.

Other assistance programs also seem to be missing their target. For example, farmers receive agricultural assistance money from the Ministry of Village and Agricultural Affairs based on the area of their arable land. In Seren village, however, agricultural support for the entire village was stopped on the grounds that some villagers had made claims relating to non-arable areas. The village muhtar pointed out that these areas were arable fields that had returned to scrub because for a decade the villagers had been given no access to farm the land. Other villagers in the province reported that after they had been forced off their lands, inhabitants of neighbouring villages had illicitly claimed agricultural support in respect of the lands left vacant.

Promising New Initiatives

There are signs that the Turkish government is beginning to recognise that its existing policy on returns will require a major overhaul if real progress is to be achieved. The government acknowledged as much in an October 2004 letter to Human Rights Watch:

The Turkish government recognizes the need for improving the Return to Village Program and will continue to make every effort towards this end. Increased transparency, greater coordination, as well as better funding of the project's implementation in particular would seem to be the reasonable requirements.[57]

There are further indications of a new direction on the part of the government. During 2004, the government opened a dialogue with the United Nations, World Bank, and European Commission representatives in order to identify areas of cooperation, and gave nongovernmental organizations an opportunity to submit their views.[58] Perhaps more importantly, two formal initiatives were launched during 2004: a new government agency to coordinate IDP policy and joint UNDP project with the Turkish government.

A new government agency for internally displaced persons

In November 2004, the Turkish Foreign Ministry informed Human Rights Watch of plans to establish a new government agency to coordinate policy and activities on behalf of IDPs. The new agency would formalize the Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project with a new policy guideline document that would define eligibility and disbursement criteria, principles, rules, and participating institutions. The agency would also develop a new national framework to coordinate this integrated strategy in accordance with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, and to develop a policy for demobilizing the village guard corps.[59]

The creation of a coordinating agency, and the concrete activities envisaged for it, are welcome and long overdue steps. The Return to Village and Rehabilitation Program has so far been little more than an empty shell. Its aims or objectives have never been made clear, and there has never been a government ministry or agency with clear responsibility for overseeing it. The announcement that the new agency will develop a plan for demobilising the village guard corps is particularly significant. To date, there have been no steps toward disarming the village guards, despite near unanimity that this is a necessary precondition for return in safety.

Joint UNDP-Turkish government project to support IDPs

The second initiative, described to Human Rights Watch at a meeting with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Ankara on November 11 2004, is a joint UNDP-Turkish government project on behalf of IDPs. According to UNDP, the project will include UNDP monitoring of the Hacettepe survey (referred to above) to establish the true scale of the original displacement and current needs of the displaced; disseminating the U.N. Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement; and building awareness and capacity among local nongovernmental organizations on how to apply those principles.

Human Rights Watch understands that the project will also include a pilot scheme in a selected province or district. The pilot would consist of a needs assessment and the development of a planning approach, involving return communities or communities of displaced persons seeking to stay and integrate in towns or cities. The aim would be to inform the government and other agencies involved in the IDP issue about relevant mechanisms. Ultimately, the information gained from the pilot could be used in the development of a larger scale return and integration program. The pilot is also intended to introduce the "participatory planning process" into local development planning, so that the needs and concerns of IDPs returning or integrating into their communities are adequately addressed. The aim would be to develop good practices which could be followed in other provinces.

UNDP has proposed a contribution of $215,000, with a $50,000 contribution from the Brookings Institution for the component dealing with raising nongovernmental organizations' awareness of the Guiding Principles. This is a fairly modest project, albeit one that has the potential to inform a much larger scale process. Its significance lies in the government's willingness to share its management of this problem with international actors in setting a model for the broader return program.

As of February 2005, neither the new agency nor the joint project with UNDP have progressed beyond the planning and proposal stage. If the goverment's consultations with intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations develop into a genuine partnership, and if the new initiatives are implemented with energy, commitment, and good faith, they have the potential to bring real benefits for the internally displaced.

There is reason for caution, however. The past decade is littered with widely-touted government initiatives for IDPs that were starved of funds, lacked political commitment, and were eventually discarded. In the spring of 2005 IDPs will once again weigh the prospects for return. It would bolster their confidence to see these two proposals approved and operationalised by the time they decide whether to continue subsisting in the cities or gamble on rebuilding their lives in the countryside.

Even if fully implemented, however, these proposals alone will not be sufficient. In June 2004, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) recommended that the government should "move from a dialogue to a formal partnership with U.N. agencies to work for a return in safety and dignity of those internally displaced by the conflict in the 1990s."[60] If the government intends to start a genuine returns process in accordance with the recommendations of the U.N. Special Representative and PACE, then its relationship with relevant intergovernmental bodies and nongovernmental organizations must become a genuine partnership and not be limited to one relatively small-scale pilot project with UNDP.

Turkey's desire to join the European Union, makes the E.U. a significant player in reform and development in Turkey. The European Commission has already signalled E.U. interest in the fate of IDPs through the reference to the issue in its regular reports on Turkey. Deeper E.U. commitment could significantly improve the chances of real progress on returns. In that regard, the Commission's representatives in Turkey should play a role in the planning of return and support of IDPs, and the monitoring of such provision. Rather than supporting for IDPs only through regional development programs, the Commission might consider encouraging and accepting smaller-scale projects in the cities from local nongovernmental organizations or local village-based community organizations. This direct connection with the return process would help to keep the Commission aware of developments in the field.

The Compensation Law

The Turkish government's implementation during 2005 of its new Compensation Law will be a key test of its commitment to a new approach toward IDPs. Introduced as a reform to meet the political requirements for E.U. candidacy, the law is intended to provide compensation to displaced persons for material damage caused between 1987 and 2004 by armed opposition groups as well as by government security forces.

Recently returned villagers by the remains of destroyed houses in Diyarbakir province.

(c) 2004 Jonathan Sugden/Human Rights Watch

The Law on Compensation for Damage Arising from Terror and Combatting Terror (Law 5233) was passed by the Turkish parliament on July 17, 2004. Regulations for implementing the law were published in the Official Gazette on October 20, 2004.

Villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch view the Compensation Law with a mixture of hope and trepidation. On the one hand, it offers the possibility of full compensation for material losses in the context of the displacement, potentially a far more powerful and effective mechanism for restitution than anything previously offered. On the other hand, the law and regulations provide ample scope for claims and payments to be avoided, minimised, and delayed.

The Compensation Law compensates for material damage inflicted by armed opposition groups and security forces combatting those groups. Damage assessment commissions established on a provincial level will investigate deaths, physical injury, damage to property and stock, and loss of income arising from inability of the owner to access their property between July 19, 1987, and July 17, 2004. The commissions comprise of: a deputy provincial governor, five civil servants responsible for finance, housing, village affairs, health, and commerce, and a board member of the local bar association. Damage assessment commissions will propose a figure for compensation on the basis of principles laid down in tables of compensation levels and, for damage to property, levels established in laws on compulsory purchase.

The commission will deduct any state payments or benefits already received in respect of the losses, and produce a detailed account with a proposed figure for compensation. The claimant may accept or reject the proposal. If the claimant rejects or fails to respond within twenty days, the proposal will be counted as void. Claimants have one year from the introduction of the law to submit their claims, and commissions must process claims within nine months. Although the mechanism lacks any internal appeals procedure, claimants can challenge the ruling in the courts if they regard the sum offered by the commission as insufficient.

The provisions of the law were substantially improved during the course of consultation prior to legislation. Nevertheless there are still concerns about the operation of the scheme, including lack of independence and composition of the assessment commissions, criteria for excluding applications, limits on acceptable forms of evidence to support claims, the lack of legal support to help people to make claims, and inadequate mechanisms to appeal against decisions by the commssions.

Lack of independence in assessment commissions

The ability of assessment commissions to reach fair conclusions depends very much on whether they are principally motivated to award compensation to people who suffered damage during the relevant period or concerned more with reducing state liability for such claims. Clearly, with a membership of six state employees and just one nongovernmental representative, independence will be a problem. The lawyer Abdullah Alakuş of the Bingöl assessment commission observed that an executive commission staffed with civil servants is not a particularly appropriate body to fulfill what is essentially a judicial process, and thought that there was a risk that injustices might result.[61]In most cases of internal displacement, state security forces working under the authority of the Interior Ministry inflicted the damage. The Interior Ministry will also be footing the bill. This conflict of interest may encourage assessment commissions to underestimate the extent of a loss or to suppress information about security force responsibility for damage during the displacement.

In some cases, the sums for damage and loss of income are very large. The lawyer Ahmet Kalpak, president of the Diyarbakır branch of Göç-Der, described a client whose loss amounted to 16,000 poplar trees and 1,000 fruit trees destroyed by fire. At a conservative estimate of $24/tree, the value of the poplars alone would be $384,000.[62] The Diyarbakır lawyer Cihan Avcı described the case of a local farmer who was unable to access his fields of 2,000 hectares for a decade. The lawyer calculated that if sown with barley during that period it could have provided an income of five million dollars.[63] Civil servants may feel that disbursing large sums of state funds to displaced Kurds from the southeast, a group long viewed with official suspicion, is not going to advance their career, and may seek ways to force payments down unfairly. As detailed below, the law and regulation provide a variety of mechanisms that would permit such reductions.

Automatic exclusions from compensation

The law prohibits the provision of compensation to those who damaged their own property; for damage arising from offences under the Anti-Terror Law committed by the claimant; and for "damage arising from economic or social factors not connected with terrorism."[64] In some cases, these ostensibly justifiable reservations may result in unfair exclusions.

If there were any official records of the destruction of villages, they would have been kept by local gendarmerie units who were in most cases responsible for the displacement. It is not known whether such records exist or what they might contain, but in order to cover up their abuses, it is possible that gendarmes may have recorded that villagers destroyed their own property intentionally or negligently. In some cases, gendarmes forced villagers to destroy their own property. Çiftlibahçe villagers, for example, told Human Rights Watch that gendarmes made them pull up their extensive and valuable tobacco crop with their own hands.[65]

The destruction of a village generally followed frequent large scale security operations in which the males of the village were detained and interrogated under torture, and then tried in state security courts for "sheltering members of an armed organization." The pattern of torture and unfair trial was extensively documented by nongovernmental organizations and in judgments at the European Court of Human Rights. As a consequence of these judgments, state security courts were abolished in June 2004. Automatic exclusion of an applicant simply on the grounds of a conviction in a state security court for "sheltering" would be unfair.

After the Return to Village and Rehabilitation Project was established in 1999, villagers who wanted to apply for assistance were required to sign a special printed form, and tick a box indicating the reason for their original migration, choosing alternatives ranging from "employment" and "health" to PKK-instigated "terror." There was no option for indicating that the reason was intimidation or forced evacuation by state forces. Many villagers resisted signing this form, and as a consequence some were threatened, beaten, and denied access to the village.[66] Rıdvan Kızgın, president of the Bingöl branch of the Human Rights Association, believes that some villagers may have checked boxes indicating social or economic reasons simply to regain access to their property.[67] Automatic exclusion on the basis of these unreliable documents would be unfair.

Inappropriate limitations on acceptable forms of evidence

The implementing regulation for the Compensation Law requires that information about the extent of damage should be collected from "public bodies and organizations,"[68] "the declaration of the person who has suffered the loss, and information from judicial, administrative and military bodies."[69] It also states that, in cases of property damage, assessment commissions will work on the basis of "incident reports describing how the damage occurred and its extent…and all forms of document relating to the assessment of damage."[70]

Since the testimony of fellow villagers who were eye-witnesses to the destruction is potentially excluded from this list because such evidence is not mentioned explicitly in the regulation, the testimony of the muhtar (the government representative elected in all villages) will be critical. There is, however, a long history of muhtars being subjected to various forms of pressure by gendarmerie and governors. At the peak of the displacements, several muhtars were murdered. Mehmet Gürkan, muhtar of Akçayurt in Diyarbakır province, forcibly evacuated on July 7, 1994, held a press conference and reported that gendarmes had tortured him to tell television journalists that the PKK had destroyed his village. In fact, he said, security forces had burned Akçayurt. When he returned to the village a month later an eye-witness saw soldiers detain him and take him away in a helicopter. He was never seen again.[71] Since that time, pressures ranging from threats of violence to withdrawal of official favour and funding have remained common. As a result, some muhtars may be reluctant to provide evidence to the commissions concerning the destruction of villages by state security forces.

Assessment Commissions should be aware that witnesses who give evidence may fear reprisals if they implicate security forces or village guards in house destruction and forced evacuation. Commissions should offer appropriate protective measures for witnesses, and investigate thoroughly any allegations of intimidation.

The regulation requires assessment commissions to use documentary evidence to establish the nature and extent of damage. In its initial work, the Bingöl assessment commission appears to be taking an approach which may result in unfairly restrictive assessments. The lawyer Abdullah Alakuş, bar association representative on the commission, told Human Rights Watch that the provision of documentary evidence was being treated as a requirement for damage assessment. The commission expected some form of certification of displacement, and an incident report on the destruction of property.[72] But applicants had no such documentation. They had initially tried to obtain documents from the gendarmerie who had refused to issue them. Alakuş emphasized that the assistant governor presiding over the commission had made positive and constructive efforts to resolve this by writing to the gendarmerie asking that they make any documentation available, but Alakuş added that he doubted that the documentation the commission was looking for existed at all. All of the villagers Human Rights Watch interviewed in Bingöl province said that they had been forced out of their homes by the gendarmerie, and it seems unlikely that the gendarmerie kept an accurate record of their own unlawful acts. Making damage assessments entirely conditional on contemporary documentary evidence, particularly if the preference is for official documents, will leave the vast majority of IDPs automatically ineligible for compensation.

No compensation for suffering and distress

In judgments against Turkey for house destruction, the European Court of Human Rights has ordered what it describes as non-pecuniary damages as compensation for the suffering and distress of the plaintiff and their family in consequence of the violation. In Akdivar v Turkey, for example, it awarded £8,000 in non-pecuniary damages to each plaintiff.[73] The Compensation Law excludes the payment of compensation for suffering and distress. This distress was substantial for IDPs who saw their homes and crops burned and their livestock machine-gunned, quite aside from the ill-treatment, torture, and "disappearances" which often accompanied the clearances.

That IDPs have suffered psychological trauma is well documented. A 1998 medical study carried out on a group of internally displaced found that 66 percent were suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, with 29.3 percent showing profound depression.[74] Another survey recorded that 9.5 percent of displaced were suffering from mental illness arising during or after displacement.[75]

Lack of legal support for applicants

The Compensation Law contains no provision for legal aid to assist applicants in preparing their claims, or assessing an amount of compensation proposed by a commission. It expects poorly educated farmers from a region with 35 percent illiteracy to assemble comprehensive and complex documentation in order to establish their eligibility for compensation.[76] Unsurprisingly, the standard of applications is poor. The lawyer and commission member Abdullah Alakuş told Human Rights Watch that most of the petitions received by the Bingöl assessment commission were improperly submitted.[77]

The Sezgin Tanrıkulu, president of the Diyarbakir bar association, and Erdal Aydemir, president of the Bingöl bar association, have strongly criticised the Compensation Law for failing to include any provision for representation by a lawyer to the commission.[78] In fact, some villagers have appointed lawyers to handle their claims. Others have asked for their applications to be handled by the Human Rights Association or Göç-Der in spite of official advice to community leaders not to involve nongovernmental organizations.A group of muhtars in the Genç district of Bingöl province told Human Rights Watch that the local sub-governor had called them to a meeting where he suggested that they help villagers to apply independently rather than with the assistance of civil society organizations.[79]

Limited capacity to process claims

It seems likely that the commissions-if they take their work seriously-will be overwhelmed by the volume of work. By November 2004, for example, the Bingöl assessment commission had received 3,000 applications, and expected up to 10,000. It had completed four meetings and looked at (but not necesssarily resolved) 150 cases.[80] The Compensation Law requires the commission to complete its work on each application within nine months.At this rate, it will take five years to examine the full 10,000 claims made in Bingöl. This situation is likely to be mirrored elsewhere, particularly since commission members who have other jobs can only work part-time.

Lack of clarity regarding payments

The Diyarbakir and Bingöl bar presidents have both expressed unease that, to their knowledge, no allocation has been made in the central government budget for possible payments under the Compensation Law, and that the law provided no time limit for the government to settle agreed claims.[81] They also raised concerns as to whether the requirement in the legislation that payments of more than 20,000 YTL ($15,000) require Interior Ministry approval is likely to cause delays or obstruct payments, particularly since most claims are likely to exceed that figure.

Inadequate appeals mechanism

There is no appeals mechanism built into the Compensation Law, either to challenge the amount of compensation awarded or for those who miss the deadline for applications. However, it is open to an internally displaced family to bring an action directly against the government through the courts.

In order to find for a claimant, the court must be satisfied that the state is criminally liable for the damage suffered, and that the sum proposed by the commission is insufficient to cover that damage. However, it is unlikely that assessment commission rulings will conclude any criminal liability on the part of the state, and villagers will therefore have to prove such liability in court, as well as demonstrate the need for a higher level of compensation. Moreover, villagers will have to pay a substantial sum to pursue their court challenge, a factor likely to discourage many from going to court.

The risks are illustrated by the story of the Kırkpınar village association. Kırkpınar was forcibly evacuated in 1993. The villagers brought a criminal action against the state for the destruction of their homes, but the court ruled that the villagers themselves, and not the state, was responsible for the damage. The villagers then planned to bring an action in the local administrative court for compensation for their lack of access to their homes and lands in the subsequent decade. They prepared 260 files in respect of losses between $35,000 and $55,000. However, under the rules of the administrative court, each plaintiff was required to pay into court approximately U.S. $1,000 before the action could go ahead. In the event that the suit is unsucessful, the court will seize the deposit to meet costs. This is a nearly prohibitive sum for IDPs who are already close to destitute. The Kırkpınar villagers were relieved when, just as they were deliberating this grave step, parliament passed the Compensation Law.[82]

Any Kırkpınar villager with a strong case for substantial compensation that is not recognized by the assessment commission, and whose claim was unfairly rejected by the administrative court might be able to bring an action at the European Court of Human Rights. However, given the inevitable delays of law and administration, it seems likely that yet another decade would have passed before justice was done.