Brazil

"REAL DUNGEONS"

Juvenile Detention in the State of Rio de Janeiro

MAP A

MAP B

I. SUMMARY

They talk about socio-educational measures, but this has nothing to do with education.

-Miguel L., age twenty-one, Instituto Padre Severino

Those places [the juvenile detention centers] are real dungeons. Anyone [can] go to the Educandário Santo Expedito or to Padre Severino and see for themselves. Those institutions don't fulfill their socio-educational function, they reproduce a prison subculture that condemns officials and youths to physical, mental, and moral suffering, and even promotes crime. To fight against this sad situation is to fight for the end of violence and for compliance with the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent.

-Maria Helena Zamora, letter to the editor, Jornal do Brasil (Rio de Janeiro), September 25, 2003.

Juvenile detention centers in Rio de Janeiro are overcrowded, filthy, and violent, failing in virtually every respect to safeguard youths' basic human rights. Beatings at the hands of guards are common. "They beat us for any reason," said Dário P., an eighteen-year-old in the Centro de Atendimento Intensivo-Belford Roxo (known as CAI-Baixada). "They'll come into the cells, and that's where they'll beat us." He told us that guards hit him hard enough to leave him with a bloody mouth; once, he said, they hit him in the genitals. "They'll call out your cell numbers-four, five, six!-and we have to undress [to be searched], and if we don't, they beat us."[1]

With some 15 million inhabitants, the state of Rio de Janeiro is larger in population than thirteen Latin American countries. The city of the same name evokes iconic images of the white sands of Ipanema's beach, the gondola to Sugarloaf Mountain, and the outstretched arms of the statute of Christ overlooking the southern part of the metropolis. Rio de Janeiro is also the setting for brutal killings of street children (one infamous case in 1993 took place in the shadow of the Candelária church in the city center), armed violence among rival drug gangs and police, and, as this report documents, the routine detention of youths in cruel and degrading conditions.

Brazil's national juvenile justice law, contained in the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente), is among the most progressive in Latin America. The statute guarantees youths in detention the right to treatment with respect and dignity, the right to be housed in conditions that meet an adequate standard of health and hygiene, the right to receive weekly visits, and the right to education and vocational training, among other rights. The state's Department of Socio-Educational Action (Departamento Geral de Ações Sócio-Educativas, DEGASE), a branch of the state justice secretariat, is the authority responsible for maintaining Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers in conformity with the statute and in a manner that is consistent with international standards.

In fact, DEGASE runs a juvenile detention system that is grossly deficient. Noting that many states are not yet in compliance with the statute, Nilmário Miranda, Brazil's special secretary for human rights, told Human Rights Watch, "The implementation of the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent is still underway, and DEGASE is the most serious case." Referring to São Paulo's infamous juvenile detention system, run by the state Foundation for the Well-Being of Minors (Fundação Estadual do Bem-Estar do Menor, FEBEM), he said, "Before [the worst] was FEBEM in São Paulo, but today it is DEGASE."[2]

Human Rights Watch visited five detention centers in Rio de Janeiro in July and August 2003. One of these facilities, the Instituto Padre Severino, is technically a pretrial detention center for boys, although it held sentenced youths as well when our researchers inspected it. A second, the Educandário Santos Dumont, houses girls who have been sentenced as well as those in pretrial detention. The three remaining facilities, CAI-Baixada, the Educandário Santo Expedito, and the Escola João Luis Alves, are exclusively for sentenced youths.

In addition to beatings and frequent verbal abuse, Human Rights Watch found that youths in many of these detention centers are locked in their cells for one to two weeks at a time as punishment for possession of contraband and other offenses that detention center officials consider severe. The determination is solely at the guards' discretion; there is no hearing, no right to appeal, and apparently no guidelines for guards to follow in meting out punishment. "Due process is nothing," the stepfather of a sixteen-year-old in detention told Human Rights Watch.[3] For lesser offenses-getting out of line, taking food out of the dining hall, or talking during a meal-youths often have to stand or sit in uncomfortable positions for hours at a time.

In spite of the commonplace nature of physical abuse, particularly in the Padre Severino, CAI-Baixada, and Santo Expedito boys' detention centers, most complaints are never investigated by DEGASE. No guard has ever been sanctioned for abusive conduct. One parent of a youth in detention highlighted the disparity between the treatment accorded to youths who resort to violence and that given to guards who engage in similar behavior, asking, "When the kids hit a guard, they take him to the police station. Why don't they do the same with the guards who beat our kids?"[4]

Over one-third of youths arrested in the state of Rio de Janeiro are charged with drug offenses, including drug trafficking. Youths are increasingly involved in the illicit drug trade, and their involvement begins at earlier ages, recent studies have concluded. The use of children under the age of eighteen "for the production and trafficking of drugs" and other illicit activities is unequivocally recognized as one of the worst forms of child labor, meaning that youth involvement in drug trafficking is both a juvenile justice issue and a child labor concern. Strategies to reduce youth involvement in drug trafficking include improving children's access to education, reducing the role of the drug gangs in their lives, providing them with vocational training, and working with employers to develop job programs that give them real alternatives to involvement in the drug trade. If Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers were fulfilling their "socio-educational" mission, they would make efforts to address youth involvement in drug trafficking through rehabilitation programs, in line with a key purpose of the juvenile justice system.

But many of the youths in CAI-Baixada, Padre Severino, and Santo Expedito receive no education whatsoever, in violation of their rights under the Brazilian Constitution and international law. Nor were they receiving vocational training, the rehabilitative service that youths and their parents most often identified as one of their top priorities. "I would give them [professional] courses in there, something to give them an opportunity when they leave. On the street, they'll need a lot. What is the opportunity for employment out there? They need some services, some sort of courses," the mother of a seventeen-year-old in Santo Expedito told us.[5]

The state's juvenile detention centers do not meet basic standards of health and hygiene. Youths often wear the same clothes for three weeks before they are laundered. Many share tattered foam mattresses; others sleep on the floor. At night, they must defecate and urinate in plastic jugs because guards will not let them out of their cells to use the toilets. They may not be able to bathe for several days at a time, either because the guards do not allow them to use the showers or because of a lack of running water. Youths in most facilities must depend on their family members to bring them soap, toothpaste, and toilet paper; those who do not have visitors must do without these necessities.

These problems are compounded by the cavalier attitude of many detention center officials, starting with the system's director. "There is a lot less in these children's houses," DEGASE director general Dr. Sérgio Novo said, telling us that Rio's detention centers were cleaner than many of their homes.[6]

As an indication of the lack of cleanliness in Rio de Janeiro's detention centers, youths and staff must endure periodic outbreaks of scabies, a contagious parasitic disease easily transmitted in the overcrowded and unhygienic conditions found in most facilities. Detention centers do not treat youths who contract scabies, increasing the likelihood that it will spread throughout the detainee population. Human Rights Watch wrote to the governor of Rio de Janeiro state in August 2003, urging her to direct DEGASE and the state Secretariat of Health to take immediate steps to provide adequate medical treatment to detained youths suffering from scabies.[7] As of this writing, we have not received a response. The consequence of such conditions in Rio de Janeiro's detention centers and inaction on the part of its public officials is that "scabies is a problem in all of the facilities in the system," as one public defender told Human Rights Watch.[8]

* * *

This report is based on a two-week fact-finding mission in Rio de Janeiro in July and August 2003, as well as additional information gathered by our researchers between August 2003 and November 2004. During the fact-finding mission, our researchers visited five juvenile detention centers in the state, including the state's only detention center for girls, and conducted private interviews with fifty-three youths, six of whom were girls. Our researchers were able to take photographs in every facility.

This is the seventeenth Human Rights Watch report on juvenile justice and the conditions of confinement for children. In the Americas, Human Rights Watch has investigated and reported on juvenile justice issues in Brazil, Guatemala, Jamaica, and the U.S. states of Colorado, Louisiana, Georgia, and Maryland. Elsewhere in the world, Human Rights Watch has documented detention conditions for children in Bulgaria, Egypt, India, Kenya, Northern Ireland, Pakistan, and Turkey. In addition, Human Rights Watch has published a book-length report on conditions in Brazil's adult prisons, one of at least thirty reports in a series on prison conditions in countries around the world.[9]

Prisons, jails, police lockups, and other places of detention pose special research problems because detainees, especially children, are vulnerable to intimidation and retaliation. In the interests of accuracy and objectivity, Human Rights Watch bases its reporting on firsthand observation of detention conditions and direct interviews with detainees and officials. Following a set of self-imposed rules in conducting investigations, Human Rights Watch undertakes visits only when our researchers, not the authorities, can choose the institutions to be visited, when they can be confident that they will be allowed to talk privately with the detainees of their choice, and when they can gain access to the entire facility to be examined. These rules ensure that our investigators are not shown "model" detention centers, "model" inmates, or the most presentable parts of the facilities under investigation. In the rare cases in which entry on these terms is denied, Human Rights Watch may conduct its investigations on the basis of interviews with former detainees, relatives of detainees, lawyers, prison experts, and detention center staff, as well as a review of documentary evidence.

Human Rights Watch takes particular care to ensure that interviews of children are confidential, conducted with sensitivity, and free from any actual or apparent outside influence. It does not print the names or other identifying information of the children in detention whom researchers interview. In this report, all children are given aliases to protect their privacy and safety.

Human Rights Watch assesses the treatment of children according to international law, as set forth in the Convention on the Rights of the Child; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; and other international human rights instruments. The U.N. Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice, the U.N. Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty, and the U.N. Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners provide authoritative guidance on the content of international obligations in detention settings.

In this report, the word "child" refers to anyone under the age of eighteen. The Convention on the Rights of the Child defines as a child "every human being below the age of eighteen years unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier."[10] This use differs from the definition of "child" in Brazil's juvenile justice law, which makes a distinction between persons under the age of twelve (who are considered "children") and those between twelve and seventeen years of age ("adolescents"). For this reason, and because Brazil's juvenile detention center may hold both adolescents and young adults between up to the age of twenty-one, this report uses the term "youth" to refer to any person between age twelve and twenty-one.[11]

II. RECOMMENDATIONS

Rio de Janeiro's Department of Socio-Educational Action (Departmento Geral de Ações Sócio-Educativas, DEGASE), a branch of the state justice secretariat, has primary responsibility for the administration of the state's juvenile detention system. It should implement Brazil's Statute of the Child and the Adolescent in a manner consistent with international juvenile justice standards. In doing so, it should be informed by the recommendations of the National Council on the Rights of Children and Adolescents (Conselho Nacional dos Direitos da Criança e do Adolescente, CONANDA), the U.N. special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, the U.N. special rapporteur on torture, and the Committee on the Rights of the Child.[12]

Brazil's federal government provides much of the funding that enables states to maintain detention centers, hire guards and provide services to detained youths. Under a presidential action plan announced in December 2003, the federal government committed additional funding to expand states' capacity to investigate and punish cases of torture, violence and other abuses in juvenile detention centers. Many of the objectives of the action plan remained unfulfilled at this writing one year later.[13]

Human Rights Watch recommends that DEGASE and, as appropriate, other state and federal entities, take the following steps in order to protect the human rights of youths in the state's juvenile detention system.

Pretrial Detention

Judges, DEGASE, police, public prosecutors, and the public defender's office should ensure that youths are held in pretrial detention for no more than the forty-five days authorized by the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent, including any period of time spent in police lockups. Time in police lockups should never be more than the five-day legal limit and should be strictly monitored to ensure respect for youths' rights, including their right to be free from torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment.

Disciplinary Practices

DEGASE should establish clear rules of behavior for youths in detention; these rules should specify the consequences of breaking each rule. It should take the following specific measures to ensure that disciplinary practices are in conformity with international standards:

- Prohibit the use of disciplinary measures that involve closed or solitary confinement or any other punishment that may compromise the physical or mental health of the youth.

- Use cell confinement only when absolutely necessary for the protection of a youth. Where necessary, it should be employed for the shortest possible period of time and subject to prompt and systematic review.

- Provide clear guidelines for detention center staff who impose discipline.

Complaint Mechanisms and Monitoring

DEGASE should establish a complaint system independent of guards. All complaints should be investigated thoroughly. Detention center staff who perpetrate violence should be appropriately disciplined and removed from duties that bring them in contact with youths. Particularly serious cases should be referred to the prosecutor's office and judicial authorities for investigation. In addition, DEGASE should permit independent monitoring of detention conditions, either by nongovernmental organizations that promote the human rights of children or by community committees formed for this purpose.

DEGASE should also overhaul its recordkeeping systems to enable it to track allegations of abuse against particular guards and any disciplinary actions taken against them. Accurate and complete employment history files can serve as a powerful deterrent to abuses as well as a useful management tool.

Prosecutorial Oversight

Consistent with their role in monitoring and protecting the rights of children and adolescents, public prosecutors in the child and youth section of the prosecutor's office (Promotoria da Infância e da Juventude) should regularly inspect juvenile detention centers without notice. They should meet with detention center directors to report deficiencies in detention conditions and should take appropriate action against directors who fail to remedy such deficiencies. When they receive reports alleging that guards have committed abuses against youths in detention, they should investigate those reports and, where appropriate, bring charges against those found to be responsible.

Public Defenders

Public defenders play a vital role in assisting youths with their defense to charges of delinquency and in aiding them with complaints of abusive treatment or substandard detention conditions. Adequate compensation and training are critical to enable public defenders to carry out their mission. The state legislature should provide that public defenders be paid on par with public prosecutors.

Conditions of Confinement

DEGASE and other appropriate state authorities should ensure that conditions of confinement for youths meet all of the requirements of health, safety, and human dignity and comply with the requirements of the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent. As a matter of priority, DEGASE should ensure that youths are housed separately according to their age, physical development, and severity of offense, as required by Brazilian law and international standards; young adults between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one should be housed in separate detention centers or in separate sections of detention centers holding youths under the age of eighteen. DEGASE and other authorities should guarantee youths' rights to receive schooling and professional training, be treated with dignity and respect, receive visits on at least a weekly basis, and have access to items necessary for the maintenance of hygiene and personal cleanliness, as required by article 124 of the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent. Because rehabilitation is served by regular contact with family members and the community, DEGASE should work with other state and nongovernmental institutions to provide external activities for appropriately screened youths, as authorized by article 121, section 1, of the statute.

Many detention facilities in Rio de Janeiro are overcrowded and in an extreme state of disrepair, with the result that they cannot offer conditions of health, safety, and dignity for youths in detention. These facilities should be renovated or replaced. In doing so, DEGASE should observe the following principles:

- Any new detention facilities should be designed for a maximum of forty youths, as recommended by CONANDA.

- New facilities should be "decentralized"; that is, located throughout the state in or near communities in which youths live rather than being clustered in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

- When existing facilities are renovated and new facilities built, living areas should be designed as small dormitories or bedrooms rather than cells, with sanitary facilities accessible from the living areas.

- Common areas should be provided that facilitate interaction among youths. Areas for educational and rehabilitative programming should be available.

Health and Hygiene

DEGASE and the Secretariat of Health should take the following steps as a matter of priority to ensure basic conditions of health and hygiene for youths in detention:

- Conduct thorough medical examinations of all youths in the Escola Santo Expedito, the Instituto Padre Severino, and the CAI-Baixada detention center.

- Provide immediate treatment to all youths found to be infected with scabies and any other infectious diseases, with follow-up treatment as necessary.

- Wash all clothing, bedding, and towels in boiling water and follow the other steps outlined by DEGASE's health unit to prevent a recurrence of the disease.

- Provide youths with sufficient soap and adequate opportunity to bathe.

- Provide every youth with his or her own mattress and bedding.

- Ensure that living areas and sanitary facilities are cleaned frequently enough to meet all requirements of health and human dignity.

DEGASE and the Secretariat of Health should also ensure that qualified medical professionals are available in each detention facility to attend to the health needs of youths. Following the recommendation of the U.N. special rapporteur on torture, qualified medical professionals should examine every person upon entry to and exit from a place of detention.

In addition, qualified personnel should provide youths with information and instruction on the prevention and control of health concerns most relevant to adolescents, with special attention to the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases and drug abuse. In particular, all youths in detention should have access to HIV-related prevention information, education, voluntary testing and counseling, and means of prevention, including condoms. Following international standards, HIV testing of youths in detention should only be performed with their specific informed consent, and pre- and post-testing counseling should be provided in all cases.

Education and Vocational Training

In accordance with Brazilian law and international standards, DEGASE and state educational authorities should provide every person held in a juvenile detention facility with an education suited to his or her needs and abilities and designed to prepare him or her for return to society and entry into the work force. DEGASE should work with state educational authorities to ensure that education provided in juvenile detention centers is recognized by schools outside of the detention system so that youths may continue their education in regular schools once they have completed their sentences.

Drug Gangs

Over one-third of youths arrested in Rio de Janeiro state are charged with drug offenses, including drug trafficking. Detention centers should provide these youths with vocational training and other specialized programming to give them alternatives to the drug trade, in line with the rehabilitative purpose and "socio-educational" mission of the juvenile justice system.

Detention centers should take steps to break down the influence of drug gangs on detained youths. In particular, those that automatically segregate youths by actual or perceived factional allegiance should consider gradually integrating youths on a pilot basis, giving due regard for institutional security. As part of this effort, DEGASE should increase the number of staff assigned to units to be integrated, and it should offer those staff members additional specialized training on adolescent behavior management techniques. As smaller, decentralized detention centers are opened, they should be integrated, following the model of the CAI-Baixada and João Luis Alves detention centers.

Girls in Detention

DEGASE should provide appropriate basic medical services for girls, including routine and timely gynecological examinations, and should provide prenatal care for girls who require it. Vocational training should be available to girls in detention, as required by the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent. Girls should have sufficient opportunities for recreation and exercise, including large-muscle exercise.

Data Collection

DEGASE should work with the juvenile court to gather accurate, comprehensive, and uniformly recorded statistics on youths charged in the juvenile court, the sentences they receive, and the detention centers to which they are assigned in order to understand the dimensions of juvenile offenses more fully. These data should be available to the public in a form that fully respects the privacy of the youths concerned. As an example of such an initiative, Rio de Janeiro authorities can look to the efforts by the state of Pernambuco's Secretariat of Administration and Reform (Secretaria de Administração e Reforma) through its InfoINFRA program to collect data for the national child and adolescent information system (Sistema de Informação para a Infância e Adolescência).

Federal Funding

The federal Special Secretariat of Human Rights (Secretaria Especial dos Direitos Humanos) should explicitly take international standards into account in directing federal funds to DEGASE and other states' juvenile detention agencies. It should dedicate a portion of these funds for training of juvenile detention staff on the relevant international standards, the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent, and strategies for dealing with youths in a manner that is appropriate and consistent with these standards. As a condition of federal funding for the construction of new detention units or the renovation of existing facilities, the special secretariat should require that proposed construction or renovation meet the requirements of health and human dignity and the rehabilitative aim of residential treatment and take into account youths' needs for privacy, sensory stimuli, opportunities for association with peers, and participation in sports, physical exercise, and leisure activities.

III. THE JUVENILE JUSTICE SYSTEM IN RIO DE JANEIRO

Just over 1,700 youths between the ages of twelve and twenty-one were in Rio de Janeiro's juvenile justice system in January 2004. Of that total, nearly 900 were awaiting trial or had been sentenced to periods of detention; the rest were on probation or completing community service.[14]

These youths are detained under Brazil's national juvenile justice law. Adopted in 1990 in a comprehensive overhaul intended to implement Brazil's obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the juvenile justice law is on paper a model statute. "The problem is the practice," said Eliana Rocha of the nongovernmental organization Brazilian Family Welfare (Bem-Estar Familiar no Brasil, BEMFAM).[15] Juvenile detention facilities in the state of Rio de Janeiro are overcrowded, understaffed, dangerous, and filthy. Although these institutions are officially termed "socio-educational" centers, they have almost no capacity for or commitment to providing education, vocational training, or rehabilitative services.

The gulf between law and practice is not lost on youths or their parents. As the mother of one detainee told Human Rights Watch, in an ironic play on the Portuguese words "educativo" (educational) and "espancativo" (relating to a bashing), "The system is not socio-education, it is social beating."[16]

The Statute of the Child and the Adolescent

Brazil's national juvenile justice law is found in the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent.[17] (The adult criminal justice system is also governed by a single national law.[18]) Under the statute, youths aged twelve through seventeen, whom it terms "adolescents," are charged under Brazil's juvenile justice law. The provisions relating to detention provide that youths may be held in juvenile detention centers up to the age of twenty-one. Delinquent children under the age of twelve are not criminally responsible; instead, they are treated as children in need of protection.[19]

Once arrested, a youth under the age of eighteen should be released to a parent or a responsible adult; deprivation of liberty should be limited to serious cases in which the youth's safety or the public order requires it.[20] If they are detained, youths may be held in police lockups for no more than five days, after which they must be released or transferred to a juvenile detention center.[21] Youths who are held in police lockups must be placed "in a section isolated from adults and with appropriate installations."[22]

As Human Rights Watch has found elsewhere in Brazil, the five-day limitation does not provide youths with effective protection from mistreatment. Police stations are subject to less independent oversight than juvenile detention centers, and both youths and adults routinely report that they are subjected to beatings and torture at the hands of police during and after arrest.[23] Such abuses often go unreported, as illustrated by one account from the stepfather of a sixteen-year-old boy held in Santo Expedito. The man told Human Rights Watch that his son was not permitted to call him for more than twelve hours after he was arrested. "He was arrested between 11 a.m. and noon, and he didn't call until midnight. He told me that he didn't have a way to call. The police didn't let him," the boy's stepfather said. "I think he was beaten." When asked how he knew, he replied, "Because he had marks on his face, very visible. He couldn't talk because the officer was right next to him, with his truncheon (cassetete) in his hand. [My son] said he hit his head on the car door."[24]

Youths may be held in pretrial detention "for a maximum period of forty-five days";[25] the statute further provides that if an adolescent is placed in pretrial detention, "the maximum and nonextendable period for conclusion of the [judicial] proceedings shall be forty-five days."[26] Despite this legal requirement, Human Rights Watch interviewed youths who told us that they had been held pending trial far in excess of forty-five days. Vitor M., fifteen, told us that he had been in Padre Severino for over ninety days in pretrial detention. He had not spoken to his mother or any other family member during that time, and he feared that they did not know where he was.[27] Similarly, sixteen-year-old Romário N. told us that he had been in Padre Severino for ninety days without a sentence.[28] Patrícia K., a sixteen-year-old held in Santos Dumont, told us that she had been held for more than 120 days without a sentence.[29] A study by the Universidade Candido Mendes and the Rio de Janeiro State University (Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro) found that the forty-five day limitation on pretrial detention was often not observed by state authorities.[30]

Delinquent youths may be sentenced to any of six "socioeducational measures": warning, reparations, community service, probation (liberdade assistida), semiliberty, and confinement in a detention center.[31] The strictest of these measures, detention (internação), should be imposed only when individually warranted, in exceptional circumstances, and for the shortest possible time.[32] This principle conforms to the standard set forth in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which provides that arrest, detention, and imprisonment of a child "shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time."[33]

Under Brazilian law, detention of a youth may last no more than three years and may not extend beyond the age of twenty-one.[34] Regardless of the length of the sentence, the judge must reevaluate the decision to detain a child at least every six months. As part of this review process, social workers with the detention centers must file reports twice yearly on each youth in detention. Human Rights Watch heard frequent complaints from social workers and public defenders that judges tend to renew detention regardless of the recommendations contained in the reports. "The judges only do a pro forma evaluation," one public defender told Human Rights Watch.[35]

Legal Representation

Brazilian law guarantees youths the right to legal representation, including free legal assistance to those in need.[36] Most of the youths interviewed by Human Rights Watch were represented by public defenders. Sir Nigel Rodley, then the U.N. special rapporteur on torture, observed in 2001 that "in many states public defenders . . . are paid so poorly in comparison with prosecutors that their level of motivation, commitment and influence are severely lacking."[37] Many of the public defenders we spoke with in Rio de Janeiro reiterated this point, and in October 2004 the state's public defenders went on strike briefly to draw attention to the lack of parity in pay between public defenders and public prosecutors.[38]

Juvenile Detention in Rio de Janeiro

Juvenile detention centers in Brazil are administered by state rather than by federal authorities. Each of the twenty-six states and the federal district has its own organizational structure, develops its own policies, and manages a separate set of juvenile detention facilities. In the state of Rio de Janeiro, juvenile detention centers are administered by the Department of Socio-Educational Action (Departamento Geral de Ações Sócio-Educativas, DEGASE), an agency of the Secretariat of State for Justice and the Rights of Citizens (Secretaria de Estado de Justiça e Direitos do Cidadão).[39]

Human Rights Watch visited the state's five juvenile detention facilities. All but one of these centers, CAI-Belford Roxo, are located in the metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro. In addition to these facilities, the state of Rio de Janeiro administers a triage and reception facility (Centro de Triagem e Recepção) and sixteen centers for youths serving the lesser sanction of semi-liberty, a measure that allows youths some freedom to work in the community and have overnight visits with family members (Centros de Recursos Integrados de Atendimento ao Menor, CRIAMs).

Efforts to Reduce the Age of Criminal Responsibility

There is popular support in Brazil, as in other countries in the region, for reducing the age at which children can be charged in adult criminal courts instead of in specialized juvenile courts. A nationwide poll in December 2003 by the Folha de S. Paulo, Brazil's largest newspaper, found that 84 percent of respondents supported a proposal that would charge fifteen-year-olds in the adult system.[40]

Such views stem in part from the inaccurate perception that youths under age eighteen are responsible for the majority of violent crimes.[41] In fact, when São Paulo's Public Security Office examined violent crimes in that state, it found that youths under the age of eighteen were responsible for 1 percent of all homicides, 1.5 percent of robberies by threat or force (roubos), and 2.6 percent of armed robberies resulting in death (latrocínios).[42] "These numbers are breaking down the myth of the dangerousness of youths and show that a reduction in the age of criminal responsibility will have a very small, ineffective impact," said Túlio Kahn, a sociologist with the Special Secretariat for Human Rights, speaking of crime rates in São Paulo.[43]

Figures for the city of Rio de Janeiro show similarly low rates for violent offenses committed by juveniles. Youths under the age of eighteen were identified as responsible for approximately 2.2 percent of homicides and 1.6 percent of robberies by threat or force in 2001, according to data from the state public security secretariat.[44] These numbers do not include unsolved cases or other cases in which the age of the responsible party is not known. Even so, these data suggest that youths under the age of eighteen commit only a small share of the city's violent crime.

In fact, the data indicate that youths under eighteen are responsible for disproportionately fewer violent offenses than their share of Rio de Janeiro's population would suggest. In 2000, for example, youths between the ages of ten and eighteen accounted for 12.5 percent of the city's population but committed only 1.5 percent of homicides and 1.7 percent of robberies by threat or force. Even if all of these offenses were attributed to youths aged fifteen to seventeen, who constituted 4.9 percent of the city's population in 2000 and who might be expected to be responsible for most violent juvenile offenses, the juvenile crime rates for these offenses are still lower than would be expected if fifteen- to seventeen-year-old youths committed crimes in direct proportion to their share of the population. The same is true even accounting for fluctuations in the crime rates: Even at their peaks, homicides and robberies by threat or force attributed to youths under eighteen never reached 3 percent in any year between 1991 and 2001, as illustrated by the chart below.[45]

SOURCE: Núcleo de Pesquisa e Análise Criminal, Secretaria de Estado de Segurança Pública, Coordenadoria de Segurança, Justiça, Defesa Civil e Cidadania, Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Anuário estatístico do núcleo de pesquisa e análise criminal (Rio de Janeiro: Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2002), http://www.novapolicia.rj.gov.br/f_aisp2.htm (viewed November 1, 2004). See also Dowdney, Children of the Drug Trade, p. 119.

A related misperception is that the vast majority of youths in Brazil's juvenile facilities are detained for acts of violence. In fact, most youths charged under the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent in Rio de Janeiro are detained for nonviolent offenses. In September and October 2002, for example, 537 cases were serious enough to warrant detention in a closed facility (internação), the most restrictive of the six "socio-educational measures" authorized by law. Of that total, 148 youths (27.6 percent of the total) were convicted of robbery by threat or force and 46 (8.6 percent) were convicted of homicide. Thirty-one (5.8 percent) were convicted of petty theft. Two hundred thirty-six youths, or 43.9 percent, were convicted of drug trafficking-offenses that are often accompanied by acts of violence but not themselves crimes of violence. (When drug trafficking involves homicide or other violent crimes, those crimes should appear as separate charges.) Including those convicted for drug offenses, at least 315 youths, nearly 60 percent the total number of youths in detention in September and October 2002, were held for nonviolent offenses.[46] These figures are likely to overstate the prevalence of violent youth crime because they include only the most serious offenses and include all youths in detention during the two-month period without regard to the length of time they have served. In that regard, it is all the more significant that three of every five youths serving sentences in the state's most restrictive facilities were held for nonviolent offenses.

These data indicate that adults, rather than youths under the age of eighteen, are responsible for the vast majority of violent crime in Rio de Janeiro and elsewhere in Brazil. Even so, Brazilian lawmakers periodically propose measures that would lower the age of criminal responsibility, either to permit youths under eighteen to be prosecuted as adults or to allow children under twelve to be adjudicated in the juvenile justice system. To date, President Lula da Silva's administration has energetically rejected such proposals. "Lowering the age of criminal responsibility will not solve anything," Márcio Thomasz Bastos, Brazil's minister of justice, said in remarks to the press in November 2003. Instead, he argued, "The way to lower crime is to increase the effectiveness of the police, the efficiency of the judiciary, and to improve conditions in the prison system."[47] Nilmário Miranda, minister in chief of the Special Secretariat for Human Rights, has made similar remarks. "Reducing the [age of] criminal responsibility doesn't tackle the roots of violence. Offering more severe penalties for those who lead adolescents into criminal activities is a good proposal to restrict violence," he said in a statement released the same month.[48]

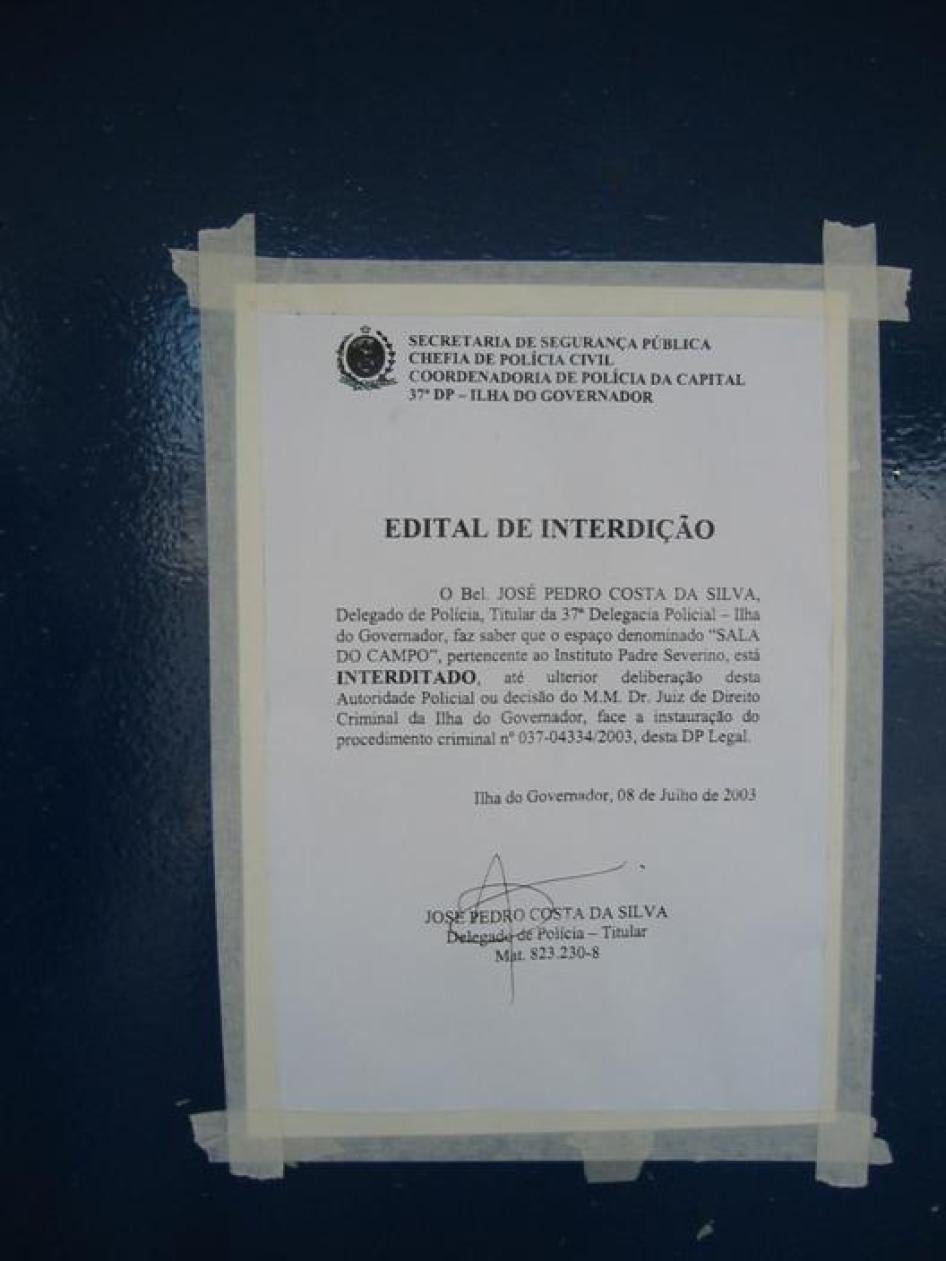

During a surprise inspection in July 2003, prosecutors discovered thirteen youths in this dimly lit, poorly ventilated Padre Severino punishment cell, viewed here from the outside. Locked inside for days in close quarters, the youths slept on the concrete floor with no mattresses or bedding.

© 2004 Stephen Hanmer/Human Rights Watch.

Police sealed Padre Severino's punishment cell after prosecutors concluded that it was "inhumane," a finding which DEGASE director general Sérgio Novo dismissed as "fantasy."

© 2004 Stephen Hanmer/Human Rights Watch.

IV. MISTREATMENT BY GUARDS

There are some [guards] who think, who see that they have sons, who know that tomorrow their sons might end up here. They're cool; they understand our situation. . . . With others, it's only hitting. They hit in the face . . . four or five come to hit me. This happens daily.

-Alfonso S., fifteen, CAI-Baixada, July 28, 2003

Once children are transferred to detention centers, they often endure violence at the hands of guards. Contrary to statements by DEGASE director general Sérgio Novo that guards were not generally abusive,[49] Human Rights Watch heard of repeated cases of abuse that were exacerbated by a lack of an effective system of accountability.

Abusive guards generally enjoy impunity, both in Rio de Janeiro and elsewhere in Brazil. In a striking exception to this rule in May 2004, a former juvenile detention center director and seven other detention center officials in the state of São Paulo were sentenced to seven to ten years in prison for acts of torture they committed in 2001 against five youths.[50] And in Rio de Janeiro, DEGASE removed the director of Padre Severino and several guards in October 2004 in response to allegations of detainee mistreatment, although at this writing none had been charged criminally.[51]

These examples illustrate that impunity need not be the rule. Public prosecutors in Rio de Janeiro have already shown a willingness to investigate abusive conditions of detention in Padre Severino and elsewhere. Their commendable efforts should be reinforced by a committed and sustained investigation of abusive officials, followed by prosecution and punishment where appropriate.

The lack of adequate staffing probably also contributes to abuses against youths. Padre Severino had on average one guard for every thirty youths, a detention official there told Human Rights Watch.[52] In CAI-Baixada, ten staff members, including the driver and the porter, were assigned to each shift to cover a population of 187 youths. And not all guards were in the detention center on any given day. Coverage was particularly sparse when several youths have their hearings on the same day. "We have to send one agent for each one," CAI-Baixada's director told us.[53]

Finally, the dearth of effective training is likely to be a factor contributing to abusive practices. Many guards have no prior experience with youths apart from the one week training course they receive before they begin to work in a detention center, Peter da Costa, director of João Luis Alves, told us.[54] Flávio Moreno, the president of ASDEGASE, a union that represents some of the guards in Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers, reported that detention center personnel have few training opportunities; those that are offered are superficial, he said.[55] In the view of Sidney Telles da Silva, former director of DEGASE, the lack of adequate training leads to "detention center officials who are not educators, but instead repressors."[56]

Beatings by Guards

We heard reports of physical abuse by guards in all detention centers we visited. "The guards are very violent," said a volunteer with a nongovernmental organization that works with detained youths.[57]

In particular, we heard from many youths that such mistreatment was common in Padre Severino. "Padre Severino was very bad," said Jorge N., a seventeen-year-old who had spent one month there in 2002. "The guards hit the guys. They spoke rudely to us. They lacked respect."[58] Vitor M., fifteen, told us that he saw guards in Padre Severino punching youths with their fists and hitting them with wooden sticks.[59]

We heard accounts of beatings by guards in other detention centers. For example, Luis A., sixteen, told us that guards in CAI-Baixada beat him and other youths.[60] Fernando R., seventeen, also reported that guards frequently beat him and other youths in Santo Expedito.[61]

Reports of such physical abuse were less common in Santos Dumont, the girls' detention center. Mayra J., sixteen, told us that she had not seen any beatings,[62] while Patrícia K., sixteen, described beatings as rare.[63] But other girls gave accounts that were similar to those we heard in the boys' detention centers. "They hit with their fists," eighteen-year-old Flávia L. said of the guards. "That has happened to me twice. The first time it was because I didn't answer. The second time, the guard yelled at me, and I talked back."[64] And Valéria I., fifteen, reported that she was beaten in a way that did not leave marks on her body during her time there.[65]

The accounts of youths themselves were not the only indication we had of abuse. In some cases, the youths we interviewed showed us cuts and bruises that were consistent with their descriptions of beatings. And when Human Rights Watch talked to a group of parents of detained children, they described seeing visible signs of abuse while visiting their children. For example, one parent spoke of a visit to Santo Expedito in May 2003:

The guards had gone in and hit everybody, beat them up. The boys were bruised, with broken arms, broken legs, covered with blood. I saw this. Fifteen boys called me over to look inside and see how they were. I saw them inside a bathroom. They lifted their shirts to show me the injuries.[66]

In addition to physical violence, verbal abuse by guards appears to be very common, based on the number of complaints we heard from youths. Sixteen-year-old Luis A. told us that guards called him and other children "bandits" and "vagabonds."[67] Miguel L., twenty-one, reported that guards routinely referred to him as a "bandit," "vagabond," "lowlife," and "devil."[68] Vitor M., fifteen, said that guards repeatedly shouted at him and other youths, "Devils, lower your heads."[69]

Finally, many of the youth we interviewed expressed fear that they would be beaten for talking with us. After Gilberto P., a nineteen-year-old in Santo Expedito, described being beaten by guards, he told Human Rights Watch that he expected to be hit later that day because he had spoken with us.[70] We heard similar remarks from other youths in that detention center. (After we toured Santo Expedito, we notified the public defender's office that a large number of youths in that detention center told us that they expected to suffer abuse in retaliation for meeting with us.)

Under international standards, detention center officials may only resort to force restrictively to prevent a youth from inflicting self-injury, injuries to others, or serious destruction of property. The use of force should be limited to exceptional cases, where all other methods have been exhausted and failed; it should never cause humiliation or degradation.[71] Detention center officials should always inform family members of injuries that result from the use of force. In cases where the use of force results in serious injuries or death, a family member or guardian should be notified immediately.[72]

Abusive Disciplinary Practices

Excessive Use of Lockup

In addition to beatings and frequent verbal abuse, many youths reported that they were subjected to excessively lengthy periods of lockup.[73] In one extreme example, when the public prosecutor's office conducted a surprise inspection of Padre Severino in July 2003, prosecutors found thirteen youths confined to a cramped and windowless cell. Describing the cell as "inhumane," officials in the prosecutor's office told us that guards had beaten the youths repeatedly and that many had respiratory and skin problems resulting from the close quarters in which they had been confined.[74] Refuting these statements, DEGASE director Sérgio Novo told Human Rights Watch that the prosecutors' claims were "fantasy." He added, "All they found were thirteen to sixteen children in a room that differed from other rooms in that the door was locked."[75]

We heard of instances of lengthy cell confinement in Santo Expedito and Santon Dumont as well. In Santo Expedito, youths told us that serious infractions led to isolation for one to two weeks in one of two unused wings of the detention center. "I have a friend who was in Gallery E. He was there two weeks ago," Luciano G. told us. "A guard put him in E, he spent a week in E, because the guard accused him of having dope." [76] Similarly, girls in Santos Dumont told us that they were placed in a punishment cell for one week if they were caught with marijuana.[77] When we asked Luciano whether there was a hearing or a right to appeal such a decision, he told us he had never heard that youths could take such steps.[78]

Elsewhere, youths reported that they were sent into lockup for much shorter periods. In those instances, the time spent in lockup was apparently completely discretionary. When we asked youths in João Luis Alves what happens if youths fight, for example, youths told us that there was no standard length of time for cell confinement. "You go into lockup, into confinement. That's so you can think about the shit you've done," said Eric T., a fifteen-year-old in João Luis Alves. "You stay there as long as you don't obey the guards. Some stay for one day. Others are there for four days."[79]

Other Punishments

Youths reported the use of other disciplinary measures that may violate international juvenile justice standards. One such practice was to force youths to stand for long periods of time in uncomfortable positions. "We had to stay like this, with our hands up," said Alfonso S., placing his hands on his head to demonstrate. "We stayed like this for eleven hours." He reported that this punishment was imposed in CAI-Baixada after a rebellion by youths in June 2003.[80] Dário P., an eighteen-year-old in CAI-Baixada, told us that similar punishments were routinely imposed for lesser infractions. "Sometimes you have to sit in a chair for a long time or stand against the wall with your head against the wall, bent over," he said. "It's generally as a punishment. I've had to do these things various times. You do it if you get out of the line. That's one of the reasons for having to do that." When we asked Dário if there were other reasons for imposing these punishments, he replied, "If you take food out of the dining hall. If they see that you were talking during the meal."[81] Suspending parental visits was another common punishment, youths told us.[82]

Legal Standards for Disciplinary Practices

Under international standards, disciplinary practices should maintain safety in a manner that upholds the detainee's inherent dignity and the rehabilitative purpose of detention.[83] In particular, these standards forbid the use of closed confinement, placement in a dark cell, "or any other punishment that may compromise the physical or mental health of the juvenile concerned."[84]

More generally, disciplinary practices should take into account the fact that contact with peers, family members, and the wider community counteracts the detrimental effects of detention on a child's mental and emotional health and promotes his or her eventual reintegration into society.[85] Reflecting this reality, international standards call for the placement of children in the least restrictive setting possible, with priority given to "open" facilities over "closed" facilities.[86] Every facility, whether open or closed, should give due regard to children's need for "sensory stimuli, opportunities for association with peers and participation in sports, physical exercise and leisure-time activities."[87] In this regard, the U.N. Rules call for detention centers to provide youths with "adequate communication with the outside world"[88]; permit daily exercise, preferably in the open air;[89] and integrate their education, work opportunities, and medical care as far as possible into the local community.[90] Consistent with this approach, the "denial of contact of family members should be prohibited for any purpose."[91]

In addition, disciplinary sanctions should be imposed in strict accordance with established norms, which should identify conduct constituting an offense, delineate the type and duration of sanctions, and provide for appeals.[92] Youths should have an opportunity to be heard in their own defense before disciplinary sanctions are imposed and on appeal.[93]

When these standards are not met, particularly when youths are confined in close quarters for extended periods of time, disciplinary practices may rise to the level of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, in violation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Convention against Torture.[94]

Impunity

When the kids hit a guard, they take them to the police station. Why don't they do the same with the guards who beat our kids?

-Parent of a youth in detention, Rio de Janeiro, August 1, 2003

Human Rights Watch found that most detention centers failed to investigate complaints of abuses; indeed, most centers had no meaningful complaint mechanism. Abuses persist in part because of the lack of effective and safe complaint procedures, the failure of authorities to investigate reports of abuse promptly, and the resulting lack of accountability for those who commit such abuses.

Exacerbating the lack of a complaint system, DEGASE does not keep centralized records of staff performance and disciplinary actions. "Right now, [DEGASE] doesn't know if official A, B, or C has a prior record, a performance history of assaults or other incidents," Dr. Simone Moreira de Souza, a public defender, told Human Rights Watch in November 2004. Such records, she said, "do not exist."[95]

Afraid of retribution, children rarely press charges; the few who do frequently drop the charges soon afterward, Dr. Souza told Human Rights Watch. In addition, she reported, social workers and defense lawyers are faced with a difficult choice: they either report the physical abuse or they stay quiet to keep the children safe and expedite their release.[96]

A 2002 case reported in the Jornal do Brasil, a Rio de Janeiro newspaper, provides an example of a situation in which the fear of retribution contributed to prosecutors' inability to secure a conviction.[97] In that case, the prosecutor's office brought charges of torture against ten guards at the Centro de Triagem e Reabilitação, a temporary detention center located next to the DEGASE headquarters. Prosecutors accused the guards of placing youths in solitary confinement cells strewn with feces and awash in sewage. The guards reportedly beat the youths and threatened to force the youths to eat the feces. In addition, the guards also instigated fighting among the youths, placing bets on the fights.[98]

The prosecutors' inspection report detailed the evidence they found to corroborate the accounts of these abuses, including "broom handles and wooden sticks with the extremities covered in cloth" to prevent leaving marks when hitting the children. In addition, the prosecutors reported, "Many of the detainees presented physical lesions that they alleged were caused by beatings from the guards."[99]

Although the guards were initially removed from work, they were all eventually acquitted.[100] Erika da Rocha Figueiredo, the public prosecutor who filed the initial charges, explained, "No one wanted to testify, and the excuse given [for youths' bruises] was that they slipped. If there is no proof, there is nothing that can be done."[101]

In other situations in which investigations do take place, their slow pace may hamper resolution of the cases. Dr. Souza recounted a 2004 case in which five guards faced criminal charges for abuses they were accused of having committed. The five were acquitted for lack of evidence, she said. "That means that none of the youths was found. The process took so long that by the time it reached the evidence-gathering stage, the youths had been released, so it was much more difficult to find them."[102]

Punishment for abusive guards is supposed to range from receiving a warning to being suspended, fired, and imprisoned.[103] Such sanctions are rarely imposed in practice, although the director and several guards were removed from Padre Severino in October 2004 after they were accused of committing abuses against detained youths.[104] And the sanction may not preclude these officials from taking a similar position at another juvenile detention center. When guards are found to have physically abused youth they are "fired" by being transferred to other centers, another official in the public defender's office told Human Rights Watch. "To be fired means to be transferred from one center to another," he told us. In one case in which a youth had been beaten by a guard, he reported, the youth was sent to Padre Severino for his protection, and the "fired" guard was transferred to the same detention center several months later.[105]

No guard has been criminally sanctioned for abusive conduct. "There is no history of condemnation of torture [by guards] in Rio de Janeiro," Dr. Souza told Human Rights Watch in February 2004. "To this day, no guard has been imprisoned for torture. Pretrial detention is sometimes ordered but later revoked under habeas corpus."[106] When we spoke with her in November 2004, she confirmed that no guard had ever been convicted for abuses committed against youths in detention. "I have never heard of an actual conviction" in such a case, she said.[107]

International standards call for the establishment of effective complaint mechanisms in each detention center. At a minimum, in addition to providing the opportunity to present complaints to the director and to his or her authorized representative, each detention center should guarantee the following basic aspects of an effective complaint process:

- The right to make a request or complaint, without censorship as to substance, to the central administration, the judicial authority, or other proper authorities.[108]

- The right to be informed of the response to a request or complaint without delay.[109]

- The right to regular assistance from family members, legal counselors, humanitarian groups, or others in order to make complaints. In particular, illiterate children should receive the assistance they need to make complaints.[110]

In addition, international standards recommend the establishment of an independent office, such as an ombudsman, to receive and investigate complaints made by children deprived of their liberty.[111]

But as the 2002 case illustrates, the mere existence of complaint mechanisms is not enough. State authorities must also conduct thorough and independent investigations of complaints. The perpetrators of violence should be appropriately disciplined by measures that should include the possibility of dismissal and criminal charges, where warranted. Cases of death, grievous bodily harm, or allegations of retaliation, in particular, should be referred to judicial authorities for investigation and, as appropriate, prosecution and punishment.

V. "FACTIONALIZATION" AND VIOLENCE AMONG YOUTHS

Youths and adults agreed that fights between rival drug gangs, particularly between members of the Comando Vermelho (Red Command) and the Terceiro Comando (Third Command), were the primary cause of violence among youths in Rio de Janeiro's detention centers.[112] With the exception of CAI-Baixada and Santos Dumont, the institutional response to the presence of members of rival drug gangs has been to separate youths according to their declared or presumed factional allegiances.

To protect youths and maintain order, it is essential to separate detainees by age, physical maturity, and severity of crime, as recommended by international standards. Housing youths of particular drug gangs together, a policy known as "factionalization," is intended to serve the same public order purpose. But separation has not worked; serious acts of violence, usually between members of rival gangs, occur frequently in Rio de Janeiro's detention centers. Moreover, separation does not address the root causes of violence. Instead, separating youths by drug gang reinforces those factional allegiances and runs counter to the rehabilitative purpose of the juvenile justice system. In some cases, the administrative division of youths by faction may create such allegiances by forcing youths to choose to live with a particular faction even if they were not originally affiliated with one.

For this reason, experts on the involvement of youths in Rio de Janeiro's drug trade recommend that juvenile detention centers take steps to break down the influence of the drug gangs on detained youths. Ending the automatic segregation of members of rival drug gangs is one step toward reducing the role of the factions in the lives of youths, provided that integration is undertaken gradually and with due regard for institutional security. The "decentralization" of detention facilities-that is, gradually moving toward smaller detention centers located closer to the communities from which youths come-is another step that will increase the likelihood of success of efforts to integrate youths. In addition, detention centers and the juvenile courts must ensure that detention is a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time, as required by international standards and Brazilian law.

Persistent and widespread violence is the result of a failure of management, not an inevitable feature of juvenile detention. Sufficient staff, adequate training, careful monitoring, and a willingness to address the role that drug trafficking plays in youths' lives will help reduce the unacceptably high level of violence in Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers.

Inter-Gang Violence

A large proportion of youths held in DEGASE institutions are detained for infractions related directly or indirectly with the drug trade, and many youths consider themselves loyal to one of the large drug gangs in the city. At least as far back as 1995, there were reports detailing the rivalry among youths in juvenile detention centers belonging to drug gangs in Rio de Janeiro, principally between the members of the Comando Vermelho and the Terceiro Comando. In 1995, the Jornal do Brasil reported on the "representation of criminal factions within the [DEGASE] complexes," bringing the issue to the attention of Judge Geraldo Mascarenhas Prado, at that time the adjudicator responsible for overseeing disciplinary measures under the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent.[113] In 1998, another Rio de Janeiro judge, Murilo Kielling, suggested that the presence and danger of the gangs in Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers justified sending a youth to be detained in another state for safety reasons. "Nowadays, [youths in Rio de Janeiro's detention centers] organize themselves into factions like those imprisoned in the penal system," Judge Kielling stated in his decision.[114] While some public officials have downplayed or refuted the existence of gangs within the state's juvenile detention system, most concur that drug gangs play a significant role in most of Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers. In 2002, for example, referring to the Instituto Padre Severino, state secretary for human rights Wania Sant'Anna rejected the notion that internal conflicts were being caused by factional rivalries,[115] but the same day, prosecutor Márcio Mothé in the 2d Branch of Infancy and Youth related the problems in Padre Severino to "war between rival [drug] factions."[116]

With the exception of CAI-Belford Roxo and Santos Dumont, the rule in DEGASE centers is of factional division. All have experienced and continue to experience serious episodes of violence among youths and between youths and staff that often result from or are related to gang disputes. Even in the wake of a staff torture scandal in September 2003, Judge Vianna considered violence among youths linked to gang allegiances to be the principal source of violence suffered by detainees.[117] At its most intense, the problem of factionalization has been the cause or aggravating factor in numerous fights and rebellions leading to escapes, injuries, deaths, and even hostage situations. The disturbances that result can also disrupt classes and other activities in the centers.

Educandário Santo Expedito

Bordering the Bangu adult prison complex, Santo Expedito has had the most violent history of gang disputes of all the DEGASE centers. Different gangs were housed apart, sometimes at the requests of the youths themselves. Those threatened by the Terceiro Comando and the Comando Vermelho were kept in a third area of the center. At the time of our visit, these quarters were separated from the Terceiro Comando quarters by a fragile plaster wall that could be easily torn down. Luke Dowdney, the coordinator of Viva Rio's program on children in organized armed violence and the author of a major study on youth involvement in Rio de Janeiro's drug trade, blames the numerous gang-related incidents at Santo Expedito to the lack of integration that is reinforced by the housing segregation. "In March 2002," he noted, "during a rebellion within the facility, a group of faction members killed an adolescent from a rival faction."[118]

Such violence is not uncommon in Santo Expedito. In November 2002, another boy was killed and two were injured in a rebellion ignited after a confrontation between Comando Vermelho and Terceiro Comando members during their school hours.[119] The housing facilities were reportedly destroyed following the police action aimed at regaining control of the center. The same night, another boy suffered burns to over 80 percent of his body after crossing a barricade of mattresses set alight by members of the Terceiro Comando.[120] Three adults linked to the Comando Vermelho, aged eighteen through twenty-one and serving sentences they received prior to reaching the age of eighteen, were identified as leaders of the disturbance and transferred to a penitentiary in Bangu.[121] Among other charges, one of these transferred youths was indicted for the attempted murder of the seventeen-year-old burn victim.[122]

An earlier rebellion in November 2001 also involved disputes between members of the Comando Vermelho and the Terceiro Comando.[123] At least four DEGASE staff members were reportedly taken hostage by detainees as Comando Vermelho members attempted to escape.[124] And there were at least three rebellions in 2000. The first, in May, was definitively linked to a gang dispute during lunch hour when the groups typically meet; it left eleven detainees injured and one police officer in the hospital.[125] As reported by O Globo, sources in the Justice Secretariat claimed in 2001 that Santo Expedito was the center that originated the practice of dividing detainees along factional lines following the May 2000 rebellion; after that mutiny, staff allegedly tried to placate the detainees by segregating them, in compliance with one of the demands made the leaders of that mutiny.[126] During a July 2000 disturbance, youths aged sixteen to twenty-one reportedly secured their escape through the front gates of the detention center by brandishing pistols and hand grenades.[127] The third disturbance, in November of that year, involved some 200 detainees and resulted in considerable property damage.[128] One of several conflicting accounts of the incidents attributes the disruption to a fight between members of the Comando Vermelho and the Terceiro Comando.[129]

Instituto Padre Severino

At the time of Human Rights Watch's visit, the detainees at Padre Severino were split along factional lines, with 90 percent identified as Comando Vermelho and 10 percent as Terceiro Comando. Padre Severino has a violent recent history of conflicts arising from or aggravated by gang disputes. In May 2002, for example, public prosecutors interviewed a sixteen-year-old boy who had serious injuries resulting from fights with members of rival gangs, according to a news account that appeared in O Globo.[130] Days later, an inter-gang quarrel led to a general rebellion in which at least forty and possibly as many as sixty youths escaped.[131] Less than a month later, in what appeared to be a gang-related act, a sixteen-year-old boy reported that twenty-two other youths attacked him, raped him, and carved the initials "CV" (for Comando Vermelho) onto his buttocks and left wrist. The boy described the attack as punishment for his failure to repay a debt on time, and he told O Globo that the carving of initials on the buttocks is used in Padre Severino to signal that a person has been raped.[132]

Escola João Luis Alves

Marcelo F., a thirteen-year-old in João Luis Alves, told Human Rights Watch that youths are housed according to gang membership but participate in activities together during the day.[133] When Human Rights Watch asked Peter da Costa, the detention center's director, about the level of violence, he suggested that the center did not have a serious problem with violence. "There are a lot of scuffles, but they're kids' things," he said, although he conceded that fights were most likely to break out between members of rival gangs.[134] Nevertheless, in June 2002, press accounts reported that youths associated with the largest gang began a disturbance in which one boy from an opposing gang sustained stab wounds, four DEGASE agents were held hostage, and various youths were victims of excessive smoke inhalation in a fire that broke out during the disturbance.[135]

Centros de Recurso Integrado de Atendimento ao Menor (CRIAMs)

Perhaps the strictest segregation along gang lines occurs in the Centros de Recurso Integrado de Atendimento ao Menor (CRIAMs), facilities for youths sentenced to semi-liberty. Luke Dowdney found that "only the offenders of a particular faction are sent to a particular facility."[136] Press accounts are consistent with his finding. In 2001, for example, a boy in the CRIAM in Santa Cruz told O Globo, "In the Bangu CRIAM only Terceiro Comando and Amigos dos Amigos boys stay. Here in Penha and on Ilha do Governador, the Comando Vermelho dominates."[137] In 2001, a Justice Secretariat source told O Globo that Bangu CRIAM staff ask the children about their factional allegiance upon arrival and recommend that Comando Vermelho members either request a transfer or jump the low walls to escape.[138] Of the Bangu CRIAM, a mother of a child in DEGASE custody asserted in 2001, "They do not accept youths who reside in a geographic region dominated by the enemy faction."[139] Indeed, also in 2001, a child who arrived at the Bangu CRIAM tattooed with the letters CV was allegedly transferred by the center's directors.[140]

Segregation by Drug Faction

In response to these security problems, youths from different gangs are housed separately in most of Rio de Janeiro's detention centers. In some cases, they may be treated as if they belong to a gang regardless of whether they were involved in one before their detention. A public defender told Human Rights Watch that any youth arrested, regardless of the crime of which he is accused, will be asked about his allegiance to a drug gang. If the youth does not belong to one, the officer will classify the youth as belonging to the gang that controls the neighborhood in which he lives.[141]

We heard the same from the youths we interviewed. For example, seventeen-year-old Flávio S. was assigned to the Comando Vermelho cells in the Centro de Triagem e Recepção in October 2004 even though he was not a member of any gang. "They ask, 'Where do you live?,'" he told us. Staff at the center place youths with the dominant gang in their neighborhood, he said. "Only if they have a doubt do they ask, 'Is it Comando Vermelho or Terceiro Comando there?'"[142] In a similar account appearing in an O Globo article, a sixteen-year-old boy from a well-off neighborhood without a significant gang presence reported that at Padre Severino, "When asked by the social worker as to which faction I belonged, I responded that I did not belong to any . . . so she told me that, unfortunately, there were no neutral cells and that I would have to choose."[143]

The factional segregation policy varies from one detention center to another. Padre Severino, Santo Expedito, the Centro de Triagem e Recepção, and some CRIAMs are internally divided by gang, with certain sections designated as Comando Vermelho and others reserved for the Terceiro Comando. Other CRIAMs effectively house only members of a particular gang.[144] Except in those centers reserved in their entirety for particular gangs, complete segregation is nearly impossible. "There's no way. You always meet," Flávio S. told Human Rights Watch.[145] Youths of different gangs may come into contact with each other at mealtimes, on their way to and from court hearings, or at other times when they are moved from one part of the detention center to another.

Two of the detention centers visited by Human Rights Watch do not separate youth by drug gang. In one of these, CAI-Baixada, "Everyone is mixed together," a volunteer who works in the detention center told us. "They're in the same rooms. They lose their identity" as a member of the gang, she said.[146] This appeared to be related both to the director's attempt to prevent factionalization and the fact that the majority of adolescents come from the interior of the state, where there are not as many problems with drug gangs. The other detention center, the Educandário Santos Dumont, a girls' detention center housing both pre- and post-trial detainees, was reported in 2000 by Jornal do Brasil to be free from conflicting factional allegiances; instead, the girls formed their own groupings. Violence still occurred, and instances of self-inflicted injuries were more frequent than in the boys' facilities.[147] Nevertheless, the experience in Santos Dumont suggests that difficulties arising from factional allegiances are largely limited to boys' detention centers; this is probably related in part to the fact that mainly men and boys do the more violent work within the drug trade.[148]

Detention officials divide youths by gang allegiances (or presumed gang allegiances) out of a legitimate concern for security. Flávio S. told us that even if he had not been placed with the Comando Vermelho, youths affiliated with the Terceiro Comando would have treated him as if he were associated with the Comando Vermelho because that gang was dominant in his community. "If suddenly they throw me into the Terceiro Comando cell, they would kill me," he said.[149] The public defender's office takes the position that "we always want to preserve the physical integrity of the adolescent even if that means dividing by factions," Dr. Souza told Human Rights Watch.[150]

But Luke Dowdney expresses concern that in separating youths by gang, the government legitimizes the authority and power of these factions and hinders long-term efforts to foster rehabilitation both inside and outside of the juvenile detention system. On the basis of a series of interviews with juvenile detention center staff and detainees, Dowdney concluded that the "need for complete integration of offenders" was one of several necessary reforms of the state's juvenile detention system.[151]

Some officials have voiced agreement with this view. In April 2001, for example, prosecutor Márcio Mothé stated, "If we want to re-socialize these adolescents, we cannot create the faction culture within the [juvenile detention] centers."[152] That same month, Judge Guaraci de Campos Vianna, Rio de Janeiro's head adjudicator in child criminal cases, criticized any form of segregation, saying that "This distortion [separation by factions], admitted by some and negated by others, cannot be."[153] For his part, DEGASE director general Sérgio Novo pledged to investigate "the involvement of [DEGASE] staff in the division of internees by factions."[154] Other public prosecutors and the Justice Secretariat followed suit announcing that they would also look into reports that gangs existed in DEGASE's detention centers.[155] Officials voiced similar sentiments in response to a wave of mass escapes in mid-2002-many related to gang disturbances-that led to the flight of 30 percent of DEGASE's detainees in the span of sixty days. Public prosecutor Asterio Pereira dos Santos pledged to issue a request to then DEGASE director Sidney Teles da Silva to cease segregating centers on the basis of gang membership.[156]

If such a request was made, it was never acted on, and by 2003 the official position on the issue appeared to have shifted dramatically. Dr. Novo stated in February 2003 that youths in detention must be separated by gang for reasons of security, according to accounts in the Folha de S. Paulo.[157]

The experience of the João Luis Alves and CAI-Baixada detention centers suggest that it may be possible to integrate youths gradually without endangering security. Such efforts should be undertaken on a pilot basis in other institutions with small groups of youths who have undergone an initial period of observation and evaluation. For such an effort to succeed, DEGASE will need to increase the number of staff assigned to integrated units, and it must offer those staff members additional training on adolescent behavior management techniques. Ultimately, integration is likely to be most successful in small detention facilities located in or near the communities in which youths live.

With 175 youths in detention when Human Rights Watch visited in July 2003, Santo Expedito appeared on paper to be only slightly over its capacity of 166. But three of the center's seven cellblocks, including the one above, were destroyed in a November 2002 fire, leading to severe overcrowding in the remaining four cellblocks.