Summary

[Probation is] like a prison sentence outside of jail. You walk around with a rope tied around your leg to the prison door. Anything can lead to revocation.

–James Yancey, Georgia defense attorney

I asked for programs but . . . [probation] didn’t want to hear that I need help; they just gave me time.

–Monique Taylor (pseudonym), who has served years on probation in Pennsylvania for conduct related to a long-standing drug dependence

Probation, parole, and other forms of supervision are marketed as alternatives to incarceration in the United States. Supervision, it is claimed, will keep people out of prison and help them get back on their feet.

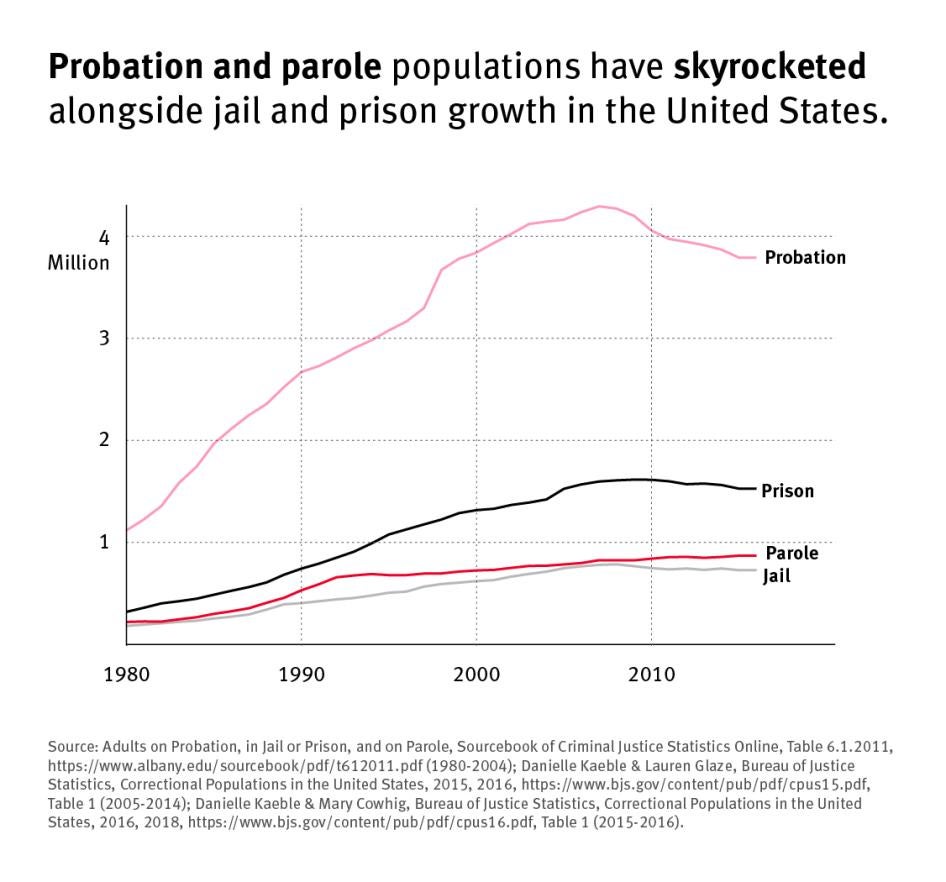

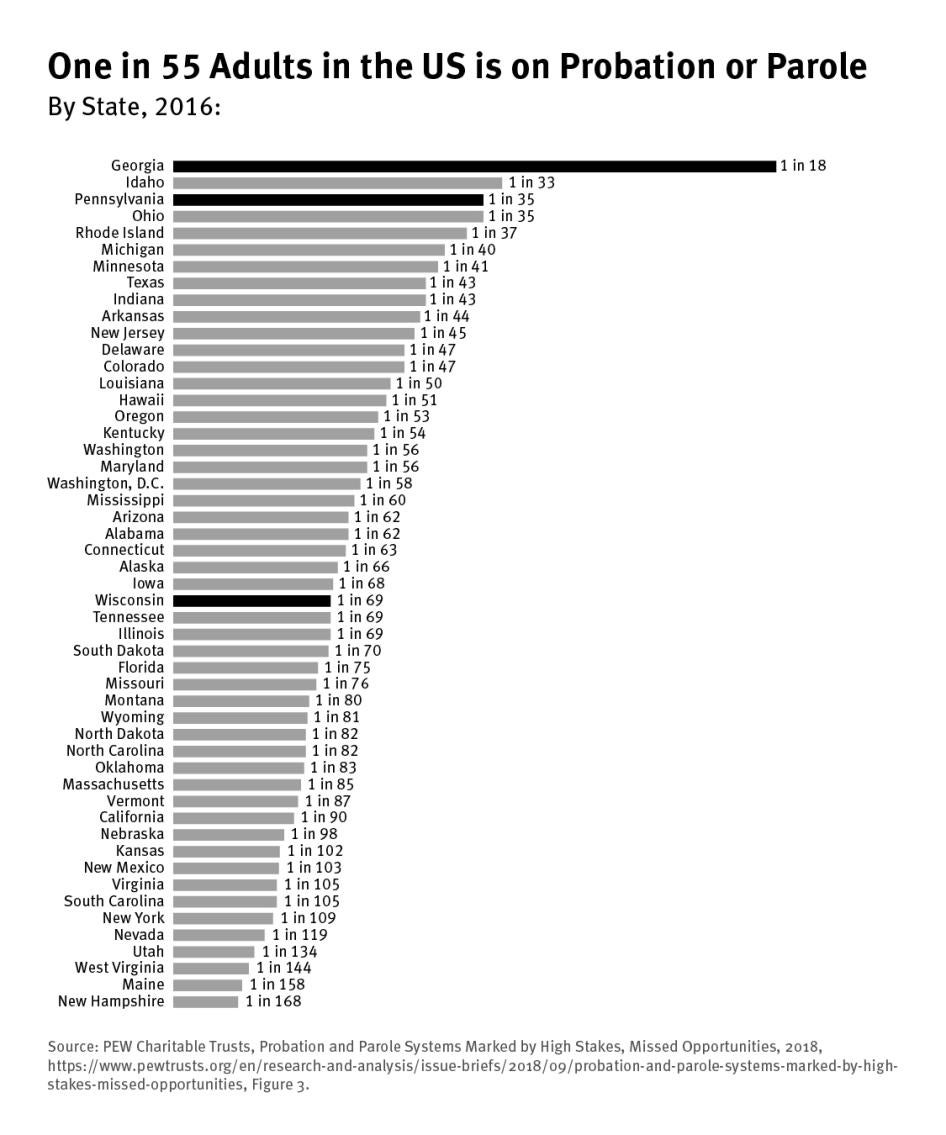

Throughout the past 50 years, the use of probation (a sentence often imposed just after conviction) and parole (served after incarceration) has soared alongside jail and prison populations. As of 2016, the last year for which supervision data is available, 2.2 million people were incarcerated in United States jails and prisons, but more than twice as many, 4.5 million people—or one in every 55—were under supervision. Supervision rates vary vastly by state, from one in every 168 people in New Hampshire, to one in every 18 in Georgia.

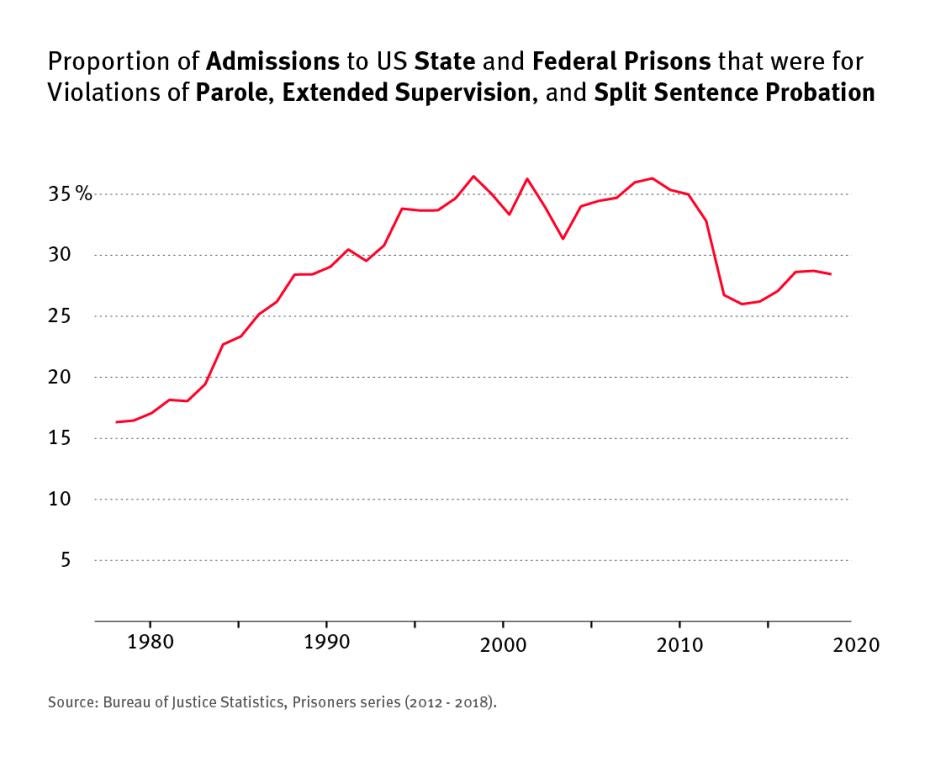

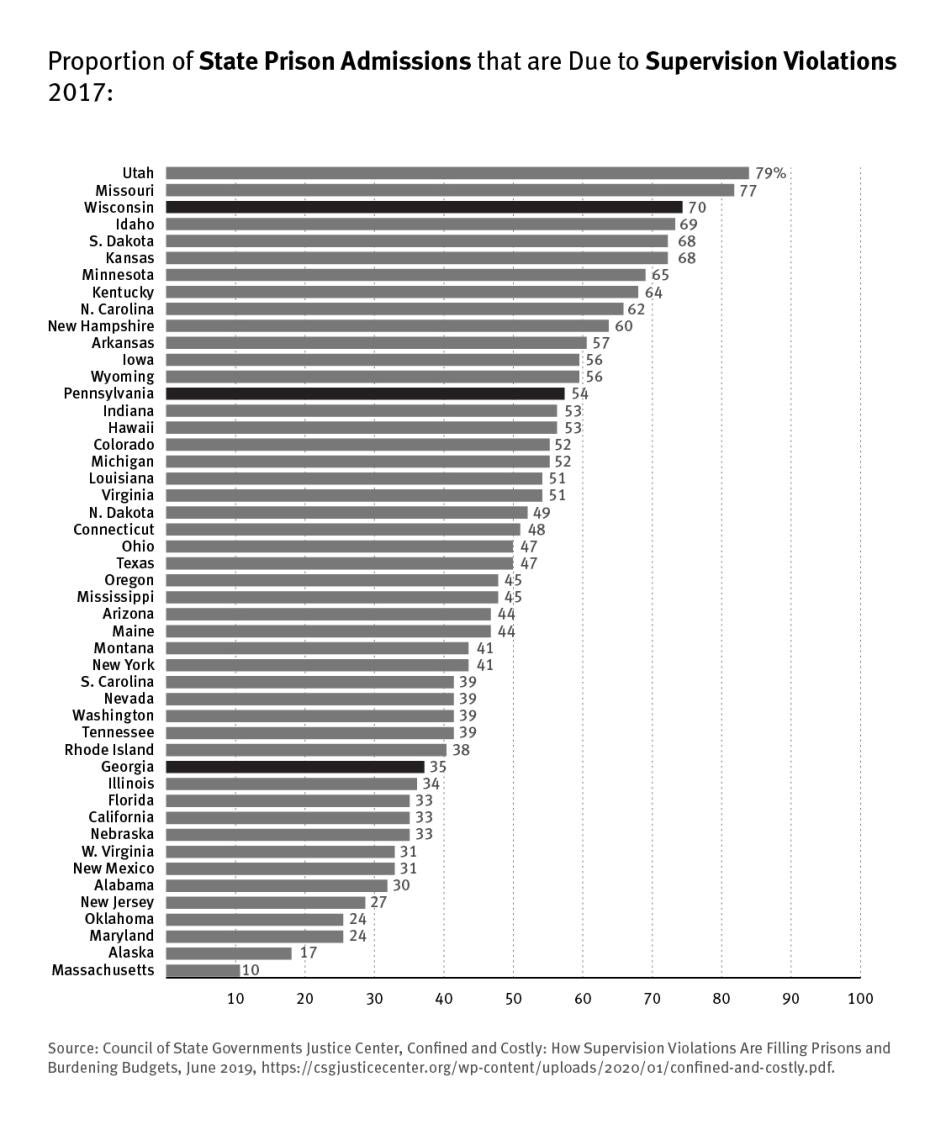

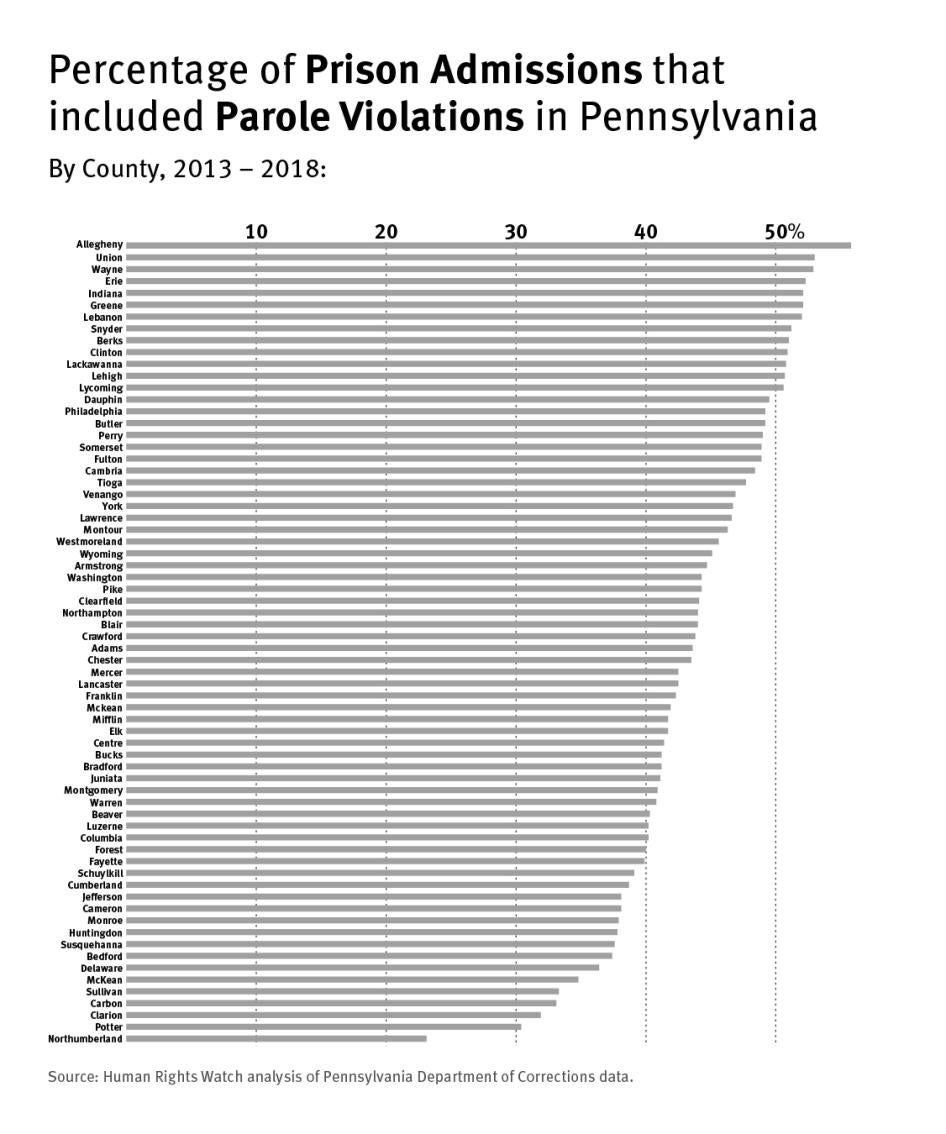

Over the past several decades, arbitrary and overly harsh supervision regimes have led people back into US jails and prisons—feeding mass incarceration. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), in the late 1970s, 16 percent of US state and federal prison admissions stemmed from violations of parole and some types of probation. This number climbed to a high of 36 percent in 2008, and, in 2018, the last year for which data is available, was 28 percent. A different set of data for the previous year from the Council of State Governments, which includes all types of probation violations—but is limited to state prison populations—shows that 45 percent of all US state prison admissions stemmed from probation and parole violations. These figures do not include people locked up for supervision violations in jails, for which there is little nationwide data. Black and brown people are both disproportionately subjected to supervision and incarcerated for violations.

This report documents how and why supervision winds up landing many people in jail and prison—feeding mass incarceration rather than curtailing it. The extent of the problem varies among states, and in recent years multiple jurisdictions have enacted reforms to limit incarceration for supervision violations. This report focuses on three states where our initial research indicated that—despite some reforms—the issue remains particularly acute: Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Drawing on data provided by or obtained from these states, presented here for the first time, and interviews with 164 people incarcerated for supervision violations, family members, government officials, practitioners, advocates, and experts, we document the tripwires in these states leading to incarceration. These include burdensome conditions imposed without providing resources; violations for minor slip-ups; lengthy incarceration while alleged violations are adjudicated; flawed procedures; and disproportionately harsh sentences for violations.

The report shows that, nationwide, most people locked up for supervision violations were not convicted of new offenses—rather, they were incarcerated for breaking the rules of their supervision, such as for using drugs or alcohol, failing to report address changes, or not following the rules of supervision-mandated programs. Of those who were incarcerated for new offenses, in our focus states, many were for conduct like possessing drugs; public order offenses such as disorderly conduct or resisting arrest; misdemeanor assaultive conduct; or shoplifting. The distinction between “rule” and “new offense” violations is sometimes blurry, as some jurisdictions do not track whether people incarcerated for rule violations also had pending criminal charges, though some data that we obtained and analyzed for this report did not have this issue.

The root causes of these violations, the report documents, are often a lack of resources and services, unmet health needs, and racial bias. The report also draws attention to marked racial disparities in who is subjected to supervision and how authorities enforce it.

In practice, supervision in many parts of the US has become a system to control and warehouse people who are struggling with an array of economic and health-related challenges, without offering meaningful solutions to those underlying problems.

There is a better way forward. States around the country are enacting reforms to reduce the burdens of supervision, while investing in community-based services. Human Rights Watch and the ACLU urge governments to build on this momentum, and divest from arrests and incarceration for supervision violations while investing in increasing access to jobs, housing, social services, and voluntary, community-based substance use disorder treatment and mental health services—services that have a record of improving public safety and that strengthen people and their communities.

Set Up to Fail

People under supervision, lawyers, and even some judges and former supervision officers recognize that supervision often sets people up to fail. People must comply with an array of wide-ranging, sometimes vague, and hard-to-follow rules, including rules requiring them to pay steep fines and fees, attend frequent meetings, abstain from drugs and alcohol, and report any time they change housing or employment.

People must follow these rules for a long period of time. While numerous experts agree that supervision terms should last only a couple of years, many states allow probation sentences of up to five years. In states including Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Georgia, probation terms can be as long as the maximum sentence for the underlying offense, in some cases 10 or 20 years, or even life—and consequences for failing are severe.

Navigating supervision is difficult and in many cases not possible without money, reliable transportation, stable housing, and access to health services. Yet few people under supervision have these resources—and supervision departments are in many cases failing to provide them. “They just gave us a sentence and put us on the street with nothing and expect us to follow rules and make stuff happen,” a man incarcerated for violations in Wisconsin told us. A young mother in Pennsylvania, who had long struggled with substance use disorder, explained, “I asked for programs but . . . [probation] didn’t want to hear that I need help; they just gave me time."

Many supervision officers interviewed for this report said that they regularly connect people with services, and that re-entry resources have increased in recent years. Yet even more officers we spoke to, and several judges, said that they wished they had more resources. Some people under supervision that we interviewed did report that certain programs were helpful, but the vast majority did not feel that way.

Conduct Triggering Violations

Supervision officers say they generally give people multiple chances before pursuing revocation. But the root causes of the violations, discussed below, often go unaddressed. It is thus no surprise that many people continually engage in the same prohibited behavior, ultimately leading to incarceration—even for minor conduct.

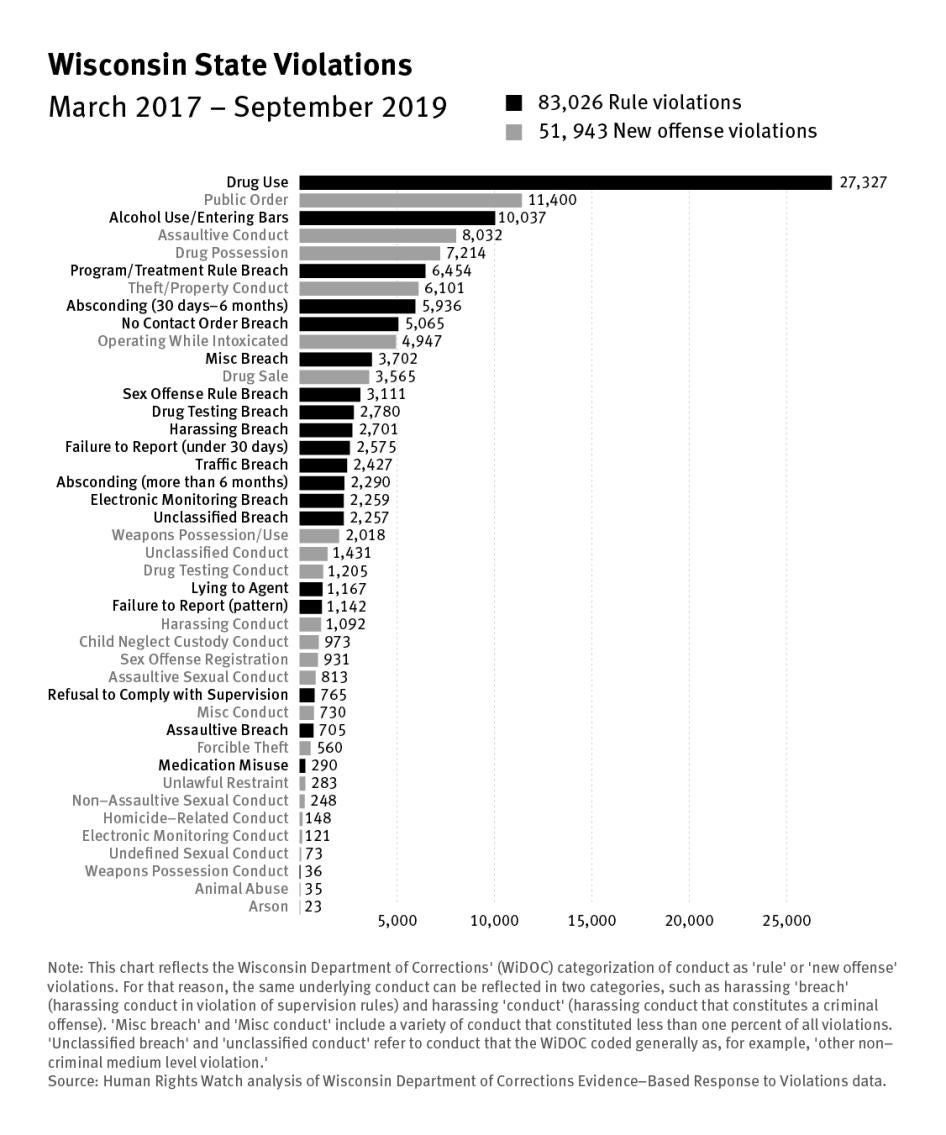

According to our data analysis, the most common rule violations that trigger incarceration in Wisconsin are using drugs and consuming alcohol or entering bars. In Pennsylvania, state parole violations largely result from people failing to report address changes and using drugs. Anecdotal evidence from Georgia (state authorities in Georgia said they could not provide the data sought) suggests that failing to report address changes and drug use are likewise driving incarceration there.

Data from Wisconsin reveal that where new offenses, as opposed to rule violations, led to violation proceedings, the vast majority were for public order offenses like disorderly conduct or resisting arrest, misdemeanor assaultive conduct, shoplifting, and drug offenses. Anecdotal evidence from Georgia and Pennsylvania showed similar trends. If drug offense arrests in these states are consistent with national arrest data, then the overwhelming majority of such drug offenses are for nothing more than possessing drugs for personal use—conduct that Human Rights Watch and the ACLU believe should not be criminalized. Our report also raises concerns about the handling of supervision violations across the board, including those that stem from serious violent conduct.

Few Procedural Protections, Disproportionate Penalties

Basic rights in criminal proceedings, such as the exclusion of illegally obtained evidence and burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, generally do not apply during “revocation hearings,” which determine whether someone violated their supervision conditions and the appropriate punishment. Many jurisdictions also limit access to lawyers for revocation proceedings.

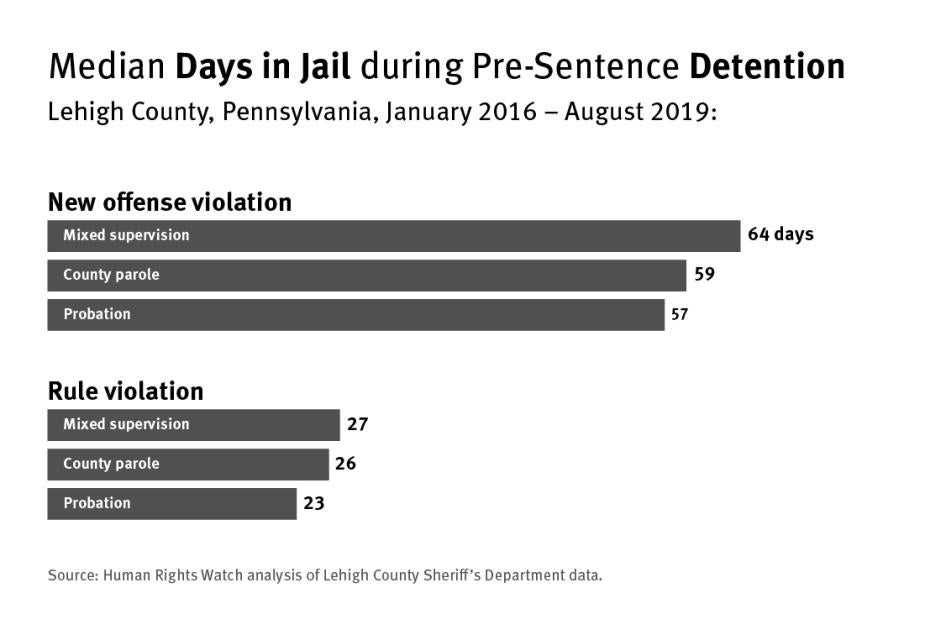

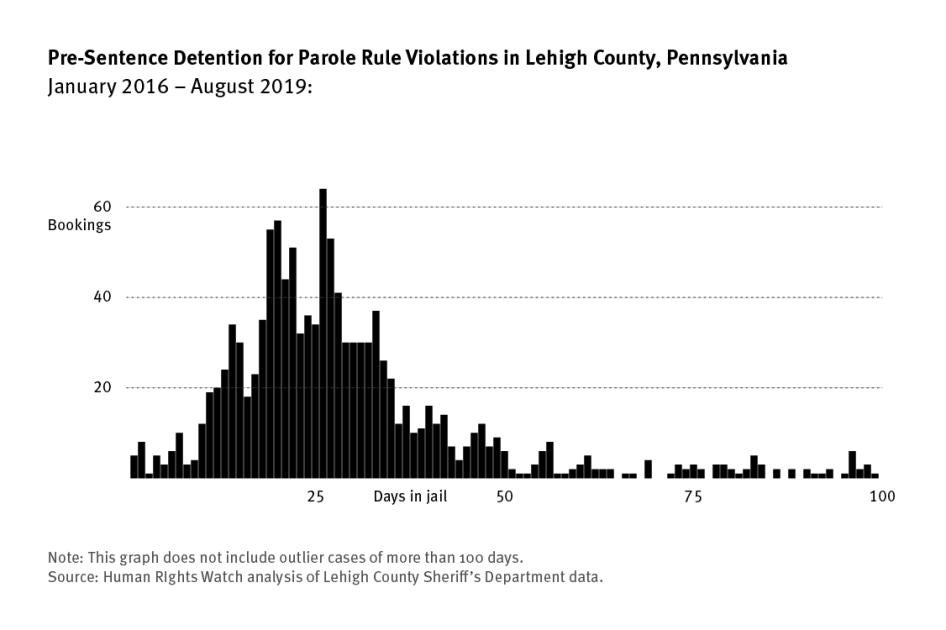

In states such as Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Georgia, people are generally incarcerated while they fight revocation, even for minor violations. Detention in parts of these states regularly lasts for months before any hearing, in violation of international human rights standards. Sometimes detention occurs in jails that are overcrowded, unsanitary, and lack adequate mental health services or access to effective drug treatment, and where staff have been accused of mismanagement and violence. These circumstances place immense pressure on people to admit to the violations in the hope they can then get out of jail.

Violations often lead to harsh penalties. In our focus states, many people are sentenced to prison-based treatment programs or additional supervision, keeping them under correctional control—at risk of more imprisonment for any slip-up—for years or decades. Other people receive disproportionately severe incarceration terms.

Feeding Mass Incarceration

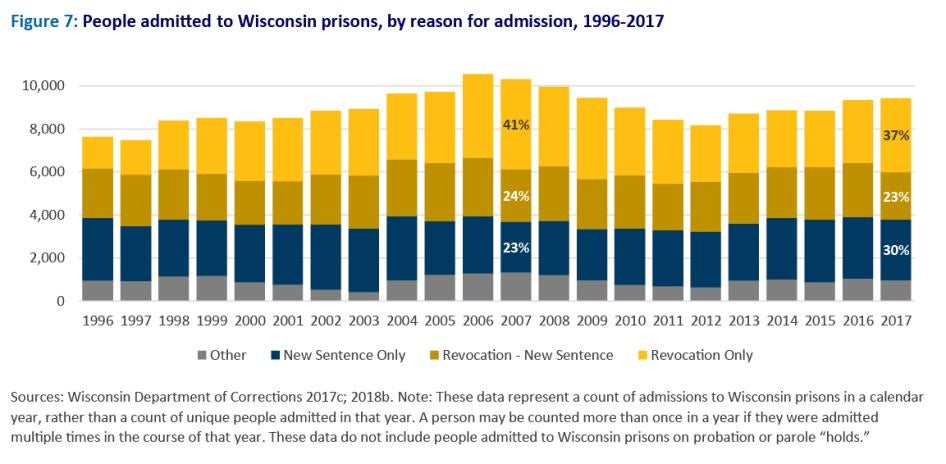

Currently, supervision is feeding mass incarceration in the United States. In 20 states, more than half of all state prison admissions in 2017 stemmed from supervision violations. In six states—Utah, Montana, Wisconsin, Idaho, Kansas, and South Dakota—violations made up more than two-thirds of state prison admissions.

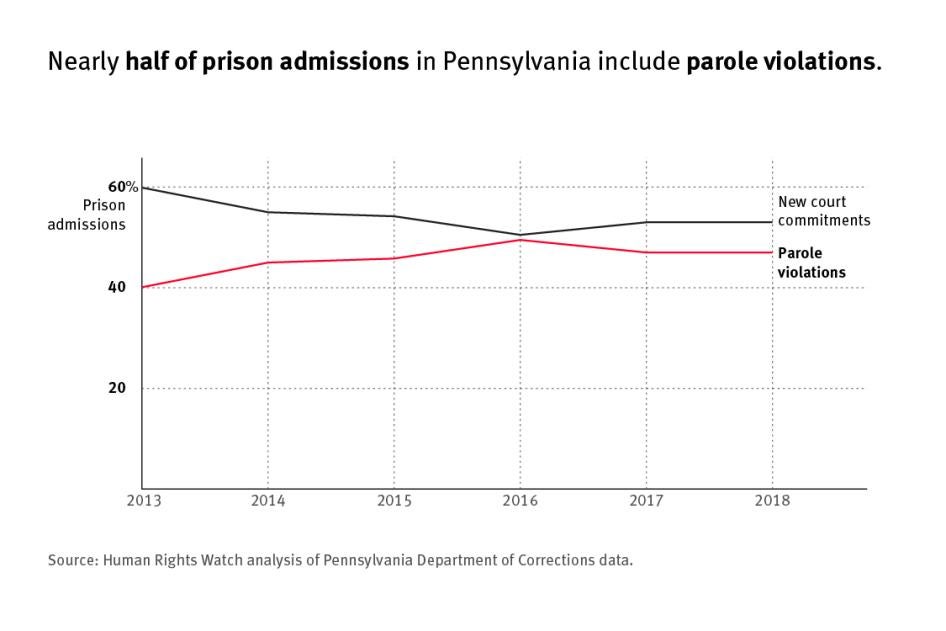

In many states, admissions for supervision violations are rising even as prison populations are otherwise falling. For instance, from 2008 to 2018, Pennsylvania reduced prison admissions for conduct other than parole violations by 21 percent, while admissions from parole violations grew by 40 percent.

Nationwide, most people incarcerated for supervision violations were locked up for violating supervision rules, not new convictions—though, in the states where we focused our research, we document problems with how violations for new offenses are handled as well.

In Wisconsin from 2017 to 2019, rule violations accounted for more than 61 percent of all supervision sanctions. In Pennsylvania, rule violations comprised 41 percent of prison admissions for state parole violations and 78 percent of probation revocations from 2016 to 2019. We were only able to obtain limited data for Georgia.

Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people are disproportionately incarcerated for violations. For instance, in Wisconsin, the proportion of Native Americans sanctioned for violations is seven times higher than their proportion of the state population; for Black people, it is four times their proportion of the population.

Rooted in Disadvantage

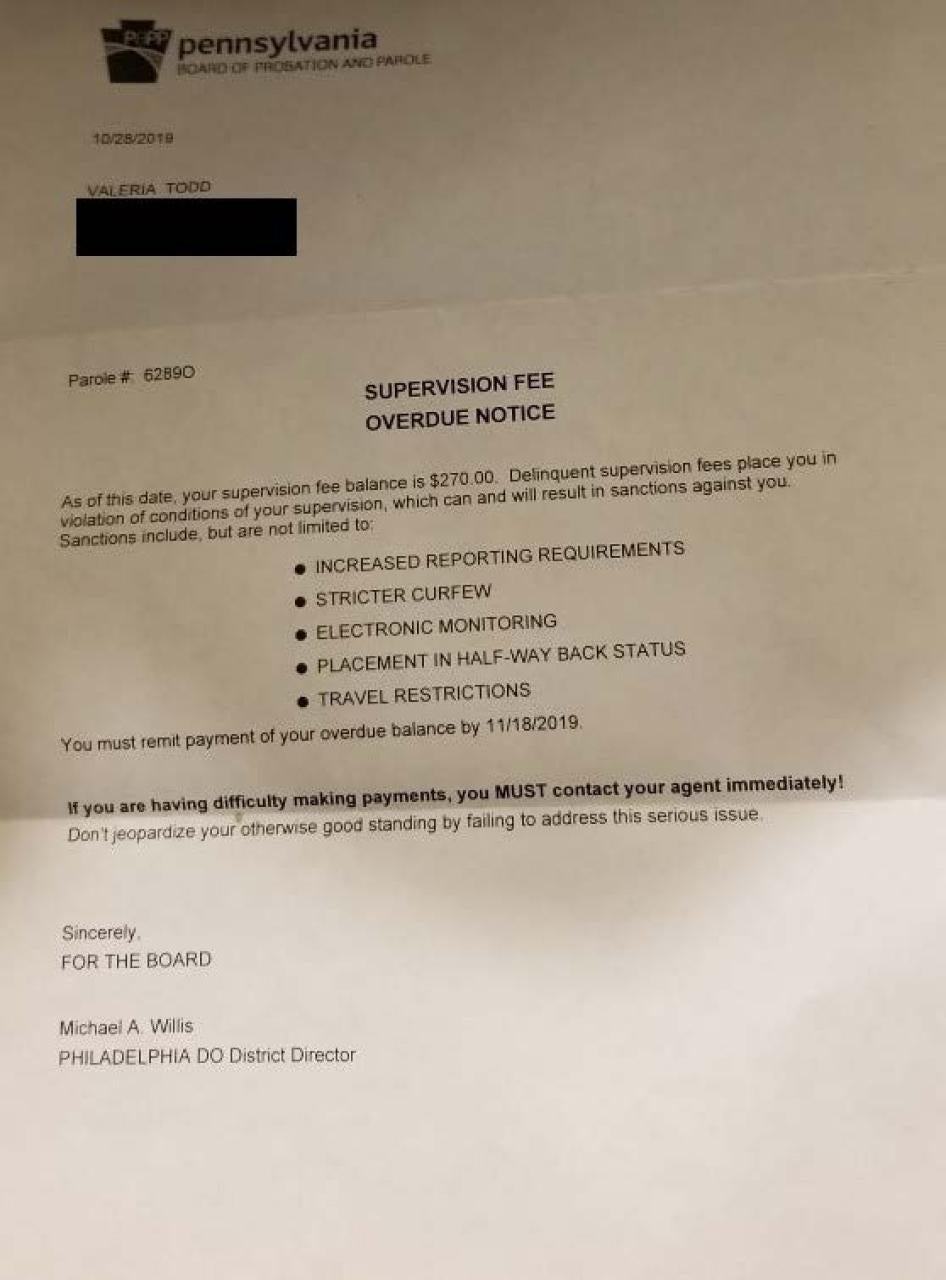

Our research demonstrates that violations often stem from disadvantage. Many people cannot afford to pay their supervision fees or other court costs while supporting themselves and their families. As a result, people often do not make their required payments. While the US Supreme Court forbids courts from jailing people solely because they are poor, judges often fail to adequately assess whether someone can pay. Additionally, many people we interviewed said they stopped reporting to supervision because they did not have the money to pay their required fees for supervision or program requirements, eventually leading to violation proceedings for failure to report.

Many people we interviewed also said that the lack of stable housing impeded their ability to comply with supervision conditions. Housing instability and homelessness often contribute to physical and mental health issues, making it harder for people to hold down jobs, attend supervision-mandated meetings, and regularly update their supervision officer on where they live.

Further, people under correctional control are disproportionately likely to have mental health conditions, which can create added barriers to navigating supervision. Meanwhile, many communities lack accessible, voluntary mental health services and treatment options.

High numbers of people are incarcerated for using drugs, including people who are struggling with substance use disorder. Many judges and supervision officers we spoke to argue that jailing people is necessary to stop them from harming themselves or others. But incarceration is, per se, a disproportionate response to personal drug use. It’s also ineffectual public health policy; health experts largely disagree that incarceration helps people recover from substance use disorder. Rather, they assert, governments should invest in voluntary, community-based, harm-reduction services and evidence-based treatment, such as Medication-Assisted Treatment and programs that do not mandate abstinence, since relapse is a normal and expected part of recovery.

Racial bias plays an outsized role in supervision violations. Generations of ongoing systemic discrimination throughout the United States have left Black and brown people less likely to have resources that make navigating supervision feasible, such as financial security, stable housing, reliable transportation, and access to drug treatment and mental health services, compared to their white counterparts. When Black people violate conditions, studies show they are more likely to face sanctions.

Meanwhile, studies show that police disproportionately stop, search, and arrest Black and brown people—making it more likely that they will be arrested in the first place and later be deemed in violation of supervision terms. Nationwide, Black drivers are more likely to be pulled over and searched than white drivers, but less likely to be found with contraband. While Black and white adults use drugs at similar rates, nationwide Black adults are two-and-a-half times as likely as whites to be arrested for possessing drugs for personal use. Disparities are even starker in some places Human Rights Watch studied. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vehicle and pedestrian stop rates for Black people are five times what they are for white people.

In addition, many states, including Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Georgia, use risk assessment tools (RATs) to set conditions and sanctions, which studies show can disproportionately label Black and brown people “high risk”—triggering tougher levels of supervision and enforcement.

A man who pled guilty to a probation term in Georgia in the hopes of avoiding prison time—only to wind up jailed, once for failure to pay and another time for using and possessing drugs—told us, “[Probation] took all my money, kept me incarcerated for simple little mistakes. It’s really been a lot of pain.”

The Path Forward

While judges and prosecutors often argue that supervision provides them with an alternative to incarceration, supervision is also imposed in cases that otherwise may have triggered less severe sanctions. Regardless, in too many cases it leads people right back into jail and prison, particularly those with limited resources. And supervision is not necessary to prevent serious crime: most violations stem from rule violations and relatively minor offenses for which there is little or no evidence that incarceration enhances public safety or reduces recidivism.

Where people on supervision engage in serious crime, moreover, law enforcement already has mechanisms in place to arrest those allegedly responsible and file charges. In the jurisdictions we examined, pursuing supervision violations in addition to criminal prosecutions for the same conduct often subjects people to lengthier detention and more sanctions, in proceedings that fail to adequately protect their fair trial rights.

Many aspects of the supervision systems we documented violate US and international law, which bar disproportionate punishment, discrimination based on race, poverty, and disability, and arbitrary detention, and which require governments to protect the right to life of people in their custody, including by providing them with necessary medical care free of charge. Various practices we documented in revocation proceedings also raise serious fair trial concerns or are inconsistent with the rights under international law to an adequate standard of living, housing, food, health, and other basic needs.

Communities have an opportunity to choose a better path. In recent years, numerous states, including Georgia and Pennsylvania, have made positive reforms—shortening supervision terms, imposing less burdensome conditions, reducing incarceration for violations, and expanding community-based services.

Additionally, court systems are increasingly diverting people charged with certain crimes away from criminal prosecutions. Meanwhile, for certain behavior that causes harm, some communities are developing restorative justice processes, which aim to hold people accountable for their actions and support those who have been harmed but encourage measures like service in and for communities, restitution, and acknowledging and apologizing for wrongdoing, over incarceration as a solution.

Across the country, community-led organizations are helping to improve people’s access to re-entry supports and services. Many people on supervision credit these organizations—often which, unlike most supervision-mandated programs, use harm-reduction models and offer assistance without preconditions—with helping them get on the right path. But such programs are sorely underfunded, and non-existent in many, particularly rural, areas.

Human Rights Watch and the ACLU call on governments to build on existing reforms, and divest from supervision and incarceration while investing in jobs, housing, education, and voluntary, community-based substance use disorder treatment and harm reduction services and mental health services. Investing in communities will help to break the cycle of incarceration and facilitate access to the resources people want and need.

|

Supervision Amidst Covid-19 The research for this report was completed before the World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a global pandemic in March 2020.[1] Since then, the danger posed to those on supervision and in jails and prisons has become abundantly clear, making the findings of this report even more urgent. As of July 2020, nine out of the ten largest clusters of Covid-19 in the United States are in jails and prisons.[2] Nearly 57,000 people incarcerated in US jails and prisons, including in some facilities examined for this report, have been infected with Covid-19, while at least 681 have died.[3] Given limited Covid-19 testing in correctional facilities, the true number is likely higher..[4] As explained in Section III, “Harsh Conditions,” US jails and prisons are at extreme risk of uncontrollable outbreaks of infectious diseases like Covid-19, given conditions of confinement including cramped quarters and a general lack of adequate sanitation and hygiene.[5] Even when people on supervision are not incarcerated, frequent in-person reporting requirements put them at greater risk of exposure and infection.[6] These concerns prompted 50 current and former supervision executives to issue a statement calling on supervision departments to limit reporting requirements, reduce probation and parole conditions and sentence lengths, and suspend or severely limit incarceration for rule violations during the pandemic.[7] Human Rights Watch and the ACLU recently called on governments to facilitate reductions in jail and prison populations.[8] Multiple jurisdictions have taken some of these steps, but high numbers of people still remain in US jails and prisons, or at risk of incarceration for any slip-up.[9] |

Key Recommendations

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union call on federal, state, and local governments to enact the following reforms to reduce the harms of supervision and help people access resources they want and need:

- Divest from probation, parole, and incarceration and invest in access to jobs, housing, education, and voluntary, community-based substance use disorder treatment and mental health services.

- Reduce the use of supervision sentences and instead impose true alternatives to incarceration, such as unconditional discharges or proportionate and flexible community service requirements.

- Where supervision terms are imposed, shorten the length of supervision terms, reduce the number and nature of conditions imposed, and strictly limit incarceration for violations, both before and following violation proceedings.

Definitions and Terms

Supervision

We generally use the term “supervision” to refer to sentences that require people to abide by a set of conditions outside of jail or prison. Conditions often include reporting as directed, staying away from drugs and alcohol, and paying all court costs. Violating any of these conditions can lead to sanctions, including incarceration, sometimes for prolonged periods of time.

This report focuses on the two most common types of supervision, probation and parole, but it also touches to a lesser extent on a third type, extended supervision.

Each state and the federal government use some form of supervision. All three focus states of this report—Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Georgia—use probation. Pennsylvania and Georgia also use parole, while Wisconsin abolished parole and replaced it with extended supervision. Pennsylvania additionally uses a form of extended supervision in some cases.

Probation

Probation accounts for the overwhelming majority of supervision terms. Courts sentence people to probation after they have been convicted of a crime, either pursuant to a plea deal or after trial. Courts may impose probation on its own, as an alternative to incarceration, or following a period of incarceration—generally called a “split sentence.”

Most states place some limits on the lengths of probation terms, but some states place no such constraints – probation can be a few months, 20 years, or in some cases, life.

Parole

Most states allow people to be released early from prison based on good behavior while incarcerated. People released in this manner typically must serve the rest of their sentence under parole supervision. For instance, if someone is sentenced to 10 years in prison, and released on parole after serving five years, they must serve the remaining five years of their sentence on parole.

Extended Supervision[10]

Extended supervision is a type of mandatory supervision imposed in some jurisdictions—typically those that have abolished parole. In these jurisdictions, people must serve a period of extended supervision after they complete their full prison terms. It is essentially a mandatory form of parole, but without early release. The state legislature generally sets the length of extended supervision terms. For instance, in Wisconsin, people must serve a period of extended supervision that is at least 25 percent of the length of their prison sentence.

Federal Supervision

The federal system, which houses about 10 percent of the total US jail and prison population,[11] uses probation and, since abolishing parole in 1987, extended supervision. This report focuses on state supervision systems and detailed discussion of the federal system is beyond its scope.[12]

State vs. County Supervision

State and/or county agencies operate supervision departments. In Pennsylvania, the state Department of Probation and Parole (PBPP) oversees people serving “state parole”—meaning parole for sentences of at least two years in prison—while counties run “county parole,” meaning parole for sentences of less than two years in prison, and probation. Wisconsin’s state Division of Community Corrections, which is housed within the state Department of Corrections, oversees all forms of supervision. In Georgia, the state Department of Community Supervision handles parole and “felony probation,” meaning probation imposed for felony offenses, while individual counties are responsible for “misdemeanor probation,” meaning probation imposed for misdemeanor crimes.

Some counties in at least eight states, including Georgia, contract with private probation companies to manage and carry out supervision monitoring and compliance. Human Rights Watch has previously documented distinct human rights concerns related to private probation.[13]

Supervision Officers

This term refers to people who enforce compliance with supervision terms. Since probation and parole are the most common forms of supervision, we sometimes write “probation officer” or “parole officer.” Some of those we interviewed use the term “PO” as shorthand.

Violation

A “violation” occurs when someone does not follow the rules of supervision. If a supervision officer believes that someone has violated supervision rules, they generally have wide discretion to determine next steps. This ranges from issuing warnings; to imposing sanctions, such as mandated treatment, a few days or months in jail, or electronic monitoring; to pursuing revocation of their supervision, which generally means incarceration.

Revocation is the most serious consequence available for violations of supervision. It withdraws the grant of what is viewed as an alternative to incarceration; as a result, the individual faces not only sanctions like those listed above, but also potential sentences of years or even decades in prison. As discussed in Section IV, “Sentencing for Violations,” in many states, revocations of parole and extended supervision can trigger incarceration for the entire remainder of the individual’s sentence. Meanwhile, in some states, probation revocation can lead to incarceration for up to the maximum sentence available for the original offense. As discussed in Section IV, many states, including Georgia and Pennsylvania, place some limits on sentences following revocation in certain contexts.

This report uses the term “violation proceedings” to refer to all proceedings related to violation of a person’s supervision, up to and including revocation. Where the fact that a person is facing revocation is relevant, we refer to the latter as “revocation proceedings” to avoid potential ambiguity.

Detainer

A detainer is essentially an order that requires someone to be detained in jail. While detainers are also used in other contexts, such as immigration proceedings, we use the term here to refer to orders requiring people to be confined pending violation proceedings.

Sometimes, judges must approve detainers, while in other cases, supervision departments can simply file them. Either way, there is no hearing prior to such detention in the three focus states covered in this report and, to our knowledge, in any jurisdiction in the US.

As detailed in Section III, “Pre-Revocation Confinement,” detainers often result in people sitting in jail for weeks or months pending violation proceedings.

Revocation Proceedings

Revocation proceedings are proceedings to determine if an individual’s supervision term should be revoked and, if so, the appropriate sentence. Sentences could include incarceration, sometimes for years or decades (see Section IV, “Sentencing for Violations”); a community- or incarceration-based treatment program; or an alternative to incarceration, such as a return to supervision with added requirements.

Proceedings begin with the filing of a “revocation petition” by the supervision officer, which outlines the alleged violations of supervision. Generally, the supervision officer also files a detainer.

Judges typically oversee probation revocation proceedings, while parole boards generally conduct these proceedings for parole violations. In some states, such as Wisconsin, Administrative Law Judges handle all revocation proceedings.

The US Supreme Court has outlined a two-step hearing process for revocation proceedings: a “preliminary” hearing followed by a “final” hearing.[14] Many states follow this two-step process,[15] while others have carved out numerous exceptions to the preliminary hearing requirement,[16] and some have even said that one hearing can be sufficient.[17]

Preliminary Hearing

The preliminary hearing is supposed to happen promptly and determine, first, if there is probable cause to believe that a violation has occurred, and second, if the person should be detained until their final hearing (see below).[18]

However, as discussed in Section III, in practice, preliminary hearings are seldom held in our focus states and, when hearings do occur, few people are released.

Final Hearing

The final hearing determines whether someone violated their supervision and the appropriate sentence. As discussed in Section III, few evidentiary protections apply and, in most states, the revocation determination is based on the preponderance of the evidence standard.[19]

As discussed in Section III, many people waive their final hearings in exchange for a set sentence.[20]

Types of Violations

Most jurisdictions differentiate between violations of supervision rules (often called “technical” violations and referred to in this report as “rule” violations) and violations involving new offenses (referred to here as “new offense” violations).

These categories sometimes overlap. For instance, using or possessing drugs can constitute both a rule violation and a new offense. Definitions of what is included in these categories also vary between and even within jurisdictions.

Data provided by the Wisconsin Department of Corrections (WI DOC) that we analyzed for this report categorized conduct as a rule violation only if the underlying conduct did not allegedly constitute a criminal offense, regardless of whether charges were filed or a conviction resulted.[21] However, data provided by the Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole (PBPP), as well as data in some national datasets mentioned in the report, categorized conduct as a rule violation so long as it did not result in a conviction for a criminal offense.[22] (See “Methodology” section.)

People can be incarcerated for both rule and new offense violations.

Incarceration

The term “jail” refers to county-run facilities that typically incarcerate people who are awaiting trial or revocation, awaiting transfer to another jurisdiction, are sentenced to shorter terms of incarceration (usually one year or less), or sentenced and awaiting transfer to prison.

The term “prison” refers to state-run facilities where people who have been convicted of a crime are serving sentences, usually of more than one year.

We use the term “incarceration” to refer to forms of confinement from which people are not permitted to freely leave, including jails, prisons, and other facilities, such as “probation detention centers” and treatment programs housed within correctional facilities.

Methodology

This report is the product of a joint initiative—the Aryeh Neier Fellowship—between Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to strengthen respect for human rights in the United States.

This report is based on extensive desk research into national trends related to the use of supervision in the United States and in our focus states of Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Georgia; 164 interviews conducted between September 2019 and June 2020; and data on incarceration for supervision violations provided to Human Rights Watch in response to public information requests or obtained through publicly available databases online.

Interviews and Observations

We conducted in-person interviews in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Georgia with 47 people who were, or had been, incarcerated for alleged violations of their supervision. We also spoke to ten of their relatives or partners. Of these individuals, 38 were Black, 17 were white, one was Native American, one identified as Latino,[23] 41 were men, and 16 were women. We additionally corresponded via e-mail and letter with 14 people confined in Wisconsin prisons, whom we could not interview in person.

Additionally, we interviewed 42 lawyers and six judges in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Georgia, and one lawmaker in Wisconsin. We also interviewed 23 community advocates in these states.

We spoke with five supervision department officials in Georgia, four supervision department officials in Wisconsin, one correctional officer in Pennsylvania, and one federal supervision department official. On May 20, 2020, the Pennsylvania Department of Probation and Parole declined our March 6, 2020 request to interview Pennsylvania supervision officers, stating they did not have sufficient resources to speak with us. Supervision departments in Montgomery County, Delaware County, and Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, did not respond to our March 6, 2020 request for interviews.

In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed eight supervision experts, one addiction psychiatry specialist, and one journalist.

With respect to the interview procedures used, most interviews were conducted in person and in private, in correctional facilities, courthouses, meeting spaces, or offices, and some were conducted via telephone. Human Rights Watch researchers took notes during interviews and generally recorded interviews where the setting permitted recordings.

We followed an interview guide and asked interviewees a series of questions regarding their background, involvement in the supervision process, the purposes of supervision and whether supervision is fulfilling those purposes, and recommendations for improving supervision systems. We also asked individuals customized questions based on their role.

Human Rights Watch researchers wrote interview memos following each interview and then conducted content and thematic analysis.

Human Rights Watch identified people to interview through a variety of sources, including court observations, defense attorneys, community organizations, and online court case databases.

All individuals interviewed provided verbal informed consent to participate and did not receive any compensation for participating in interviews. In some cases, we paid transportation or meal expenses. Individuals interviewed were offered the option of using their real name or a pseudonym in the report.

Where possible, we reviewed public court records and case documents provided by individuals we interviewed.

In addition to interviews, Human Rights Watch observed numerous supervision violation proceedings on nine separate days in Chatham County and Lowndes County, Georgia; Philadelphia County, Delaware County, and Montgomery County, Pennsylvania; and Milwaukee County and Brown County, Wisconsin. Human Rights Watch also attended community meetings regarding supervision reform in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Green Bay, Wisconsin.

We did not research supervision connected to juvenile justice systems. Accordingly, all figures in the report refer to people who were charged and prosecuted as adults. Since all states allow children under age 18 to be charged as adults in some circumstances, these figures may include children.[24] In this report, the terms “child” and “children” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law.

Data Requests and Quantitative Analysis

Human Rights Watch conducted original analysis of data available online through the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Further, Human Rights Watch submitted a series of data requests to state and local correctional agencies in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Georgia. The requests sought policies, procedures, and guidelines related to the imposition of supervision, as well as individual-level data for people admitted to jail or prison for supervision violations, including biographical information, their supervision sentence, conduct triggering violation proceedings, length of incarceration pending violation proceedings, and the outcome of those proceedings and sentence imposed.

We received requested policies, procedures, and guidelines regarding supervision practices from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections; Georgia Department of Community Supervision; Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole; and Bucks, Lehigh, Allegheny, Lancaster, Potter, and Sullivan counties in Pennsylvania. Agencies that responded to our requests for individual-level data, and limitations on the data provided, are described below. Numerous counties in all three states did not respond to our request.

Wisconsin

Human Rights Watch analyzed three Wisconsin Department of Corrections (WI DOC) datasets. The first we received from WI DOC in response to a public records request drawn from a body of data called the Wisconsin Evidence-Based Response to Violations (EBRV), which is a database that contains all sanctions—from warnings, to months in jail, to revocation—for supervision violations (“sanctions dataset”). In the sanctions dataset, supervision officers coded violations as “rule” or “new offense” violations based on their perception of the individual’s underlying conduct: If a supervision officer believed that the underlying conduct constituted an alleged rule violation, they coded it as a rule violation. If the supervision officer believed that the underlying conduct constituted an alleged new offense—regardless of whether charges were filed—they coded it as a new offense violation.[25]

We filtered this dataset to only include the months with complete cases (March 2017 – September 2019). The data does not include any information about criminal history before that related to the supervision violations that occurred during this time period. We created grouping variables to aggregate violations and government responses to the violations. We grouped 147 distinct violations into 42 different violation categories and 58 distinct response types into 14 response categories.

Human Rights Watch also analyzed WI DOC data that was publicly available, not the result of our public records request, about the reasons for admission to state prison—which included revocation for a rule violation, revocation for a new offense violation,[26] a new sentence (unrelated to revocation), and a category called “other”[27]—from 2000 to 2019 (“prison admissions dataset”). Unlike the sanctions dataset, in this dataset the WI DOC coded conduct as a rule violation as long as it did not result in a new conviction and sentence.[28] Accordingly, people imprisoned for rule violations in the prison admissions dataset may or may not have been accused of conduct that allegedly constituted a crime.

Human Rights Watch additionally received raw data from the WI DOC, in response to our records request, that merged information from the sanctions and prison admissions datasets. The WI DOC cautioned that “[b]ecause there is no way to match exactly the admission movement to the violation record the resulting data should be considered an ‘estimate’ as the violations associated with the admissions may not be the right violations,” and noted that “not all admissions had associated violation records from EBRV due to the timing of when the DOC started recording violation records from EBRV.”[29] Given these limitations, Human Rights Watch did not analyze this data.

However, a Wisconsin lawmaker provided Human Rights Watch with a preliminary processed version of similar merged data, which he obtained through a public records request (“merged dataset”). The merged dataset contains a subset of people admitted to prison following revocation for rule violations between January 2017 and June 2018, drawn from the prison admissions dataset, and includes the alleged underlying conduct that triggered revocation of their supervision, based on the sanctions dataset. WI DOC officials warned that “this data should be interpreted with caution as there are still a number of data entry errors that have yet to be corrected.”[30]

Additionally, in response to a public records request, Dane County, Wisconsin, provided data on everyone booked into jail between January 2016 and January 2019 who had a probation or parole violation. With this data, Human Rights Watch was able to estimate time spent in jail for each individual. However, because the data did not differentiate between people held pending violation proceedings and people incarcerated following violation proceedings, we could not meaningfully analyze this data and thus it was not included in the research for this report.

Pennsylvania

Human Rights Watch downloaded data on Pennsylvania state prison admissions from the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. Data provided statewide and county level numbers regarding admissions for state parole violations.

Additionally, we acquired data from the Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole (PBPP) regarding all state parole violation hearings between January 2016 and July 2019 in response to a public records request. Information on conditions that were violated was stored within a long string variable. We used text searching to identify the codes for different types of conditions violated for each case. Additionally, we created grouping variables for data on hearings and offenses. Beyond the generic code for violation types, we could not analyze the specific types of new offense violations because of a lack of standardized data entry. The dataset did not provide information on the penalties imposed for violations.

In this dataset, the PBPP coded conduct as a “new offense” violation if the conduct resulted in a criminal conviction.[31]

In addition, Human Rights Watch received data regarding all county jail admissions for parole and probation violations from 2016 to 2019 from Lehigh County, Pennsylvania. Human Rights Watch coded violation and charge types into categories. This data provided dates for initial incarceration and sentencing, allowing for a computation of the length of detention before sentencing. Due to a lack of standardized data entry, we could not analyze the underlying conduct that led to incarceration.

Human Rights Watch also received data from the Pennsylvania Sentencing Commission regarding probation revocations between January 2016 and December 2019. However, we did not produce original analysis from this data given the quality of publicly-available analysis of this same data. The publicly-available analysis provided information on sentences following revocation and whether the conduct triggering revocation constituted a “rule” or “new offense” violation. The Sentencing Commission informed us that each county reported data regarding probation revocations absent a standard definition of “rule” and “new offense” violations.[32] Accordingly, some counties may have included alleged criminal conduct that did not result in a conviction as a “new offense” violation, while others may have only considered conduct that resulted in a conviction to be a “new offense” violation.[33] Given broad categorizations, we could not meaningfully analyze the underlying conduct that led to revocation.[34]

Georgia

The Georgia Department of Community Supervision informed us that they could not provide the individual-level data requested because they merged databases in 2015, and the relevant data was not yet mature enough. The Georgia Department of Corrections informed us that relevant laws did not require them to release the requested data.

Human Rights Watch obtained information publicly available on Georgia county jail websites. We worked with computer science and economics students at the University of Georgia to collect information from Georgia. Human Rights Watch was able to examine data scraped from jail rosters for nine Georgia counties during the course of five months of Summer and Fall 2019 (June 1 – October 31). To ascertain the types of charges that led to jail bookings, we removed all bookings that were not for new criminal charges or did not involve probation or parole violations, such as people serving jail sentences. This analysis allowed us to determine what proportion of bookings involved probation and parole violations.

The data analyses, focused on descriptive statistics, were completed in R. R code and data is on file with Human Rights Watch.

Note on State Selection

We spent a month at the start of this project defining its scope and selecting states on which to focus, informed by phone interviews with practitioners and advocates, as well as extensive desk research. We chose to highlight Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Georgia because these states had high numbers and proportions of people incarcerated for supervision violations and racial disparities in their data. Each state also presented advocacy opportunities.

Background: Supervision in the United States

History of Supervision

When first used as part of the criminal legal system, supervision was designed to divert people away from incarceration and help them reintegrate into their communities.[35] It was first used in the United States during the late 19th Century.[36] Courts began sentencing certain people—typically those convicted of low-level crimes, often related to alcohol use, whom they deemed capable of rehabilitation—to “probation.”[37]

As part of probation, a community “sponsor” would watch over the individual, impose regulations on what they could do, and help them “rehabilitate.”[38] After a few weeks, the sponsor would report back to the court.[39] If the judge agreed that the person was “reformed,” they would be set free.[40] Failure to meet probation’s requirements, however, could trigger prison.[41]

Around the same time, US prisons began releasing certain people convicted of crimes and sentenced to prison early on “parole” for good behavior.[42] As with probation, a community member would monitor the individual, set rules, and help them reintegrate, typically for about six months.[43] Those who followed all conditions were set free, while those who violated the rules faced re-incarceration.[44]

Supervision became increasingly popular across the US as a tool of rehabilitation.[45] By the 1950s and 60s, nearly half of the people convicted of crimes were sentenced to probation.[46]

Transformation of Supervision

Beginning in the 1970s, supervision fundamentally changed. Then-US President Richard Nixon had declared a “war on drugs”—which, evidence suggests, was fueled by political concerns and racial bias, rather than public health.[47] Over the next decade, the “war on drugs” combined with a larger “tough on crime” policy, ushering in an era of harsh sentencing laws, including, “mandatory minimum” sentences and “habitual offender” laws for drug-related and other conduct.[48] Amidst this movement, many politicians and practitioners began railing against supervision, which they perceived as too lenient, and pushed to send more people to prison to serve longer sentences.[49] Meanwhile, a widely publicized study argued that “nothing works” to rehabilitate people.[50] As a result, political consensus shifted away from rehabilitation towards punishment and incarceration as a solution to conduct considered criminal.[51]

Legislatures, court systems, and supervision agencies toughened conditions, lengthened supervision terms, increased monitoring, and heightened sanctions for violations.[52] Those tasked with enforcing conditions, who had previously considered themselves “counselors” who helped “clients,” began identifying as “officers” who monitored “offenders.”[53]

Additionally, states began imposing supervision in addition to—rather than instead of—prison or jail terms. By the 1980s, upwards of 20 states had either eliminated or dramatically reduced early release to parole.[54] Many states replaced parole with “extended supervision” – a mandatory supervision term imposed after people complete their full prison sentences.[55] Also around that time, courts increasingly imposed “split” probation sentences after conviction, requiring people to serve jail or prison time followed by a period of probation.[56]

The use of supervision also skyrocketed. As incarceration in the United States grew nearly five-fold between 1980 and 2007, from about 500,000[57] to 2.3 million,[58] the population under parole (220,400 to 826,100) and probation (1.1 million to 4.3 million) grew almost four-fold.[59]

Supervision Today

As of 2016, the last year for which national data on supervision is available, 4.5 million adults—or one in every 55—were under supervision.[60] Of those on supervision, the overwhelming majority—81 percent, or nearly 3.8 million people, were under probation supervision[61]—while the remaining 19 percent were on parole.[62] Rates of supervision in the United States are five to ten times the rates of European nations, similar to incarceration rates.[63]

In Wisconsin, one in every 69 adults, or 66,400 people, were under supervision as of 2016.[64] In Pennsylvania, the number was one in every 35 adults, or 296,200 people.[65] And in Georgia it was one in every 18 adults, or 430,800 people.[66]

Numbers are particularly stark in some counties we studied. In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, one in 23 people is on supervision—the highest rate of any big city in the US.[67] In neighboring Delaware County, Pennsylvania, one in every 20 adults is subject to supervision.[68]

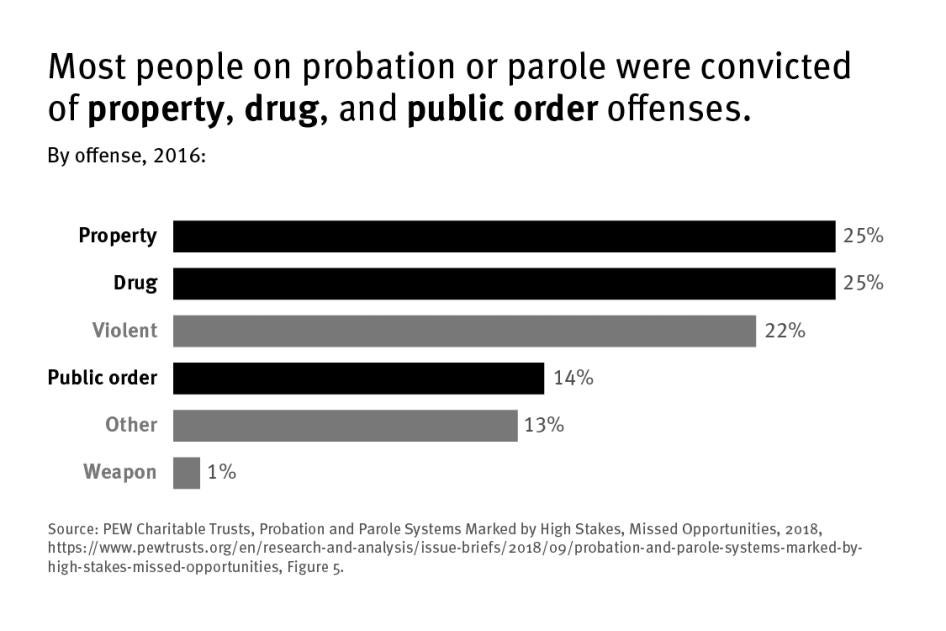

Nationwide, most supervision sentences are imposed for low-level conduct. At the end of 2016, one quarter of probation and parole terms were imposed for property crimes, another quarter were imposed for drug crimes—which, nationwide, are overwhelmingly for personal possession[69]—14 percent were imposed for public order offenses, and 22 percent were imposed for crimes considered violent.[70] Some scholars argue that, rather than using probation instead of incarceration (“leveling down”), judges and prosecutors also use probation in cases that would otherwise have triggered less severe sanctions (known as “leveling up”), such as fines or community service.[71] In Georgia for example, courts routinely sentence people to probation for traffic infractions if they cannot pay the required fines and fees on their court date.[72]

Supervision terms can be lengthy. Once people are released to parole, states often require them to serve the full remainder of their sentence under parole supervision—which can be significant.[73] For instance, Pennsylvania uses “indeterminate” sentences, meaning rather than serving a fixed prison term of, say, 10 years, people receive a minimum sentence and a maximum term that is at least twice as long as the minimum, such as 10 to 20 years.[74] People released after serving the minimum 10 years[75] must then serve the remaining decade of their sentence under parole supervision.[76]

Extended supervision terms can also be long. For instance, under Wisconsin law, whenever a judge sentences someone to prison, they must also impose a period of extended supervision that is at least 25 percent of the length of the prison term.[77]

Probation sentences can be even longer. Sixty-two percent of states cap probation terms for most offenses at five years, but at least five states—California, Georgia, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—place no ceiling on probation sentences.[78] Judges in these states can impose probation terms as long as the maximum sentence for the underlying crime.[79] For example, repeat shoplifting in Georgia carries up to 10 years of probation.[80] In Wisconsin, possessing 40 grams of cocaine with intent to distribute can trigger 40 years of probation.[81] Where people are sentenced for multiple offenses at the same time, judges in some states, including Pennsylvania and Georgia, can sentence people to separate probation terms for each offense and run them consecutively, which can lengthen probation terms.[82]

Most states, including Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, allow for early termination of supervision in certain cases.[83] However, state law often requires people to first pay off all restitution (money they owe to compensate others for losses related to their crime, such as paying back a shop for stolen items), as well as sometimes court costs and fines, including supervision fees.[84] As discussed below, for many people, paying these costs is not possible.[85]

Meanwhile, in at least 13 states, including Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, an individual’s supervision term can be extended for failing to pay certain court debt.[86]

Who is Under Supervision: Race and Class Disparities

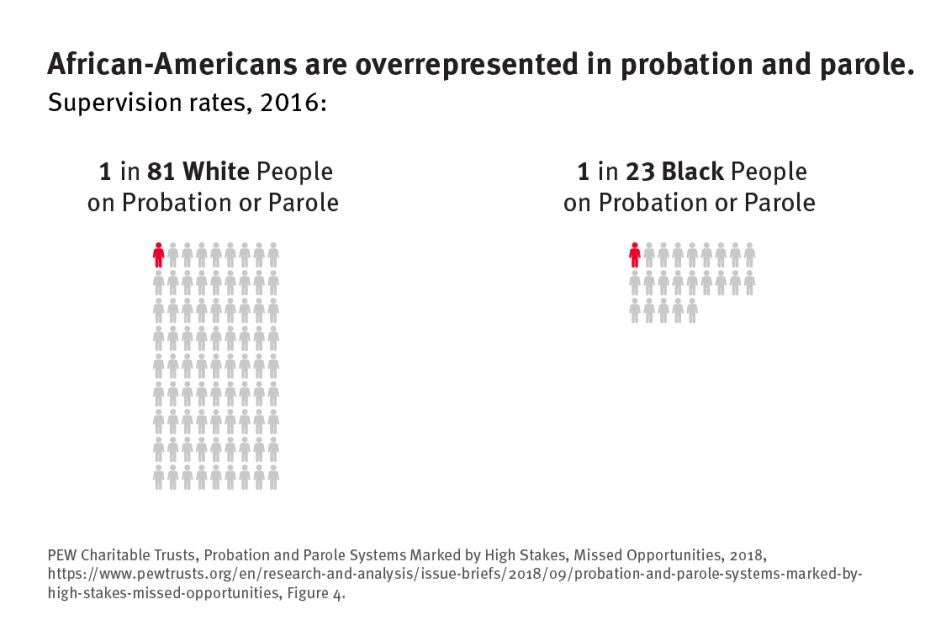

Supervision disproportionately impacts Black and brown people and those with limited financial means. Nationwide as of 2016, one in every 81 white people were under supervision, compared with one in every 23 Black people.[87] Black people comprise 13 percent of the US adult population, but 30 percent of the supervision population.[88]

Disparities are even starker in some jurisdictions where Human Rights Watch conducted in-depth research. In Wisconsin in 2017, the last year for which data is available, one in every eight Black men were on supervision—more than five times the rate for white men.[89] Rates are also high for Native American men, one of every 11 of whom were on supervision, a rate four times that of white men.[90] In Chatham County, Georgia, which contains Savannah, Black people represent 39 percent of the population but 67 percent of the population under felony probation.[91] In Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, which contains Pittsburgh, Black people comprise 13 percent of the population but 42 percent of the supervision population.[92] In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, one in every 14 Black people are under supervision.[93]

People under supervision are also disproportionately low-income.[94] Two-thirds of people on probation make less than $20,000 a year, and two in five people on probation make under $10,000 a year—far below the poverty line.[95]

Poverty in the United States intersects profoundly with race.[96] Nationwide, more than 20 percent of Black people live in poverty—twice the rate of white people.[97] Further, the median Black household wealth is just one-tenth that of white households.[98] These disparities in wealth result from decades of racist policies in areas from the criminal legal system, to housing, to employment.[99]

I. Requirements of Supervision

You’re telling [people on supervision] ‘you need to have employment, you need to have this,’ . . . it’s already life-altering and then you feel like someone’s breathing down your neck.[100]

—Valerie Todd, who served more than a decade on supervision in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Burdensome Conditions

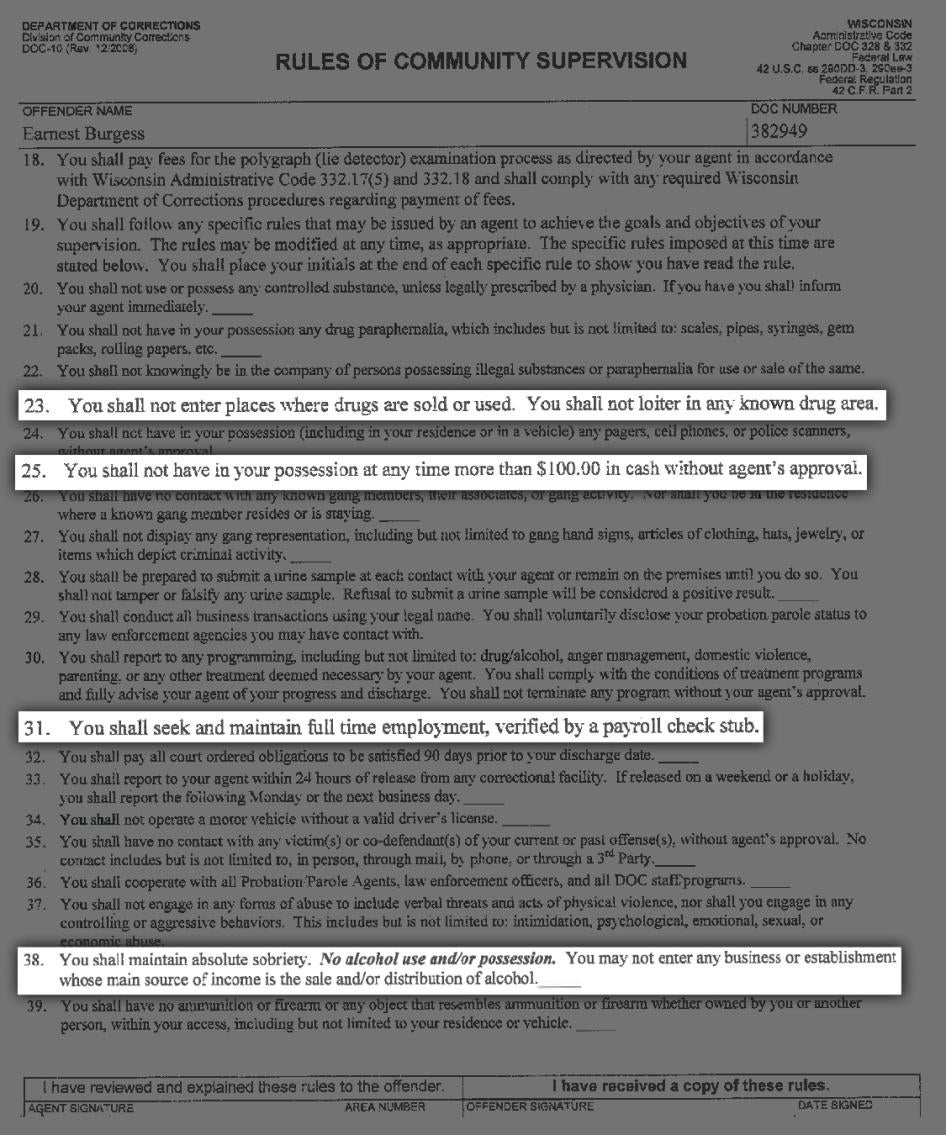

Supervision is daunting. Nationwide, people under supervision must comply with an average of 10 to 20 conditions a day.[101] Courts, parole boards, and/or supervision officers generally impose a set of standard conditions without regard for individuals’ needs or capabilities.[102] Further, they retain vast discretion to impose additional conditions.[103] Some people must comply with upwards of 60 rules.[104]

Common ConditionsCommon conditions of supervision include: |

|

|

Ø Report as directed Ø Abstain from drugs and alcohol Ø Pay court costs Ø Complete court-ordered treatment Ø Submit to drug tests |

Ø Obtain employment Ø Report all address changes Ø Stay away from “disreputable” people Ø Be truthful to supervision officers Ø Submit to warrantless searches |

Children Under SupervisionWhile supervision in juvenile justice systems is beyond the scope of this report, it is important to note that, as of 2017—the last year for which data is available—about 310,800 children were placed on juvenile probation in the United States.[105] This figure does not include children sentenced to probation as adults, meaning the true number of children under supervision is likely much higher.[106] The way children on supervision are treated varies among states, but they are often subjected to a wide array of rules—sometimes more than 30—that would be difficult for any child to comply with.[107] These rules include things that may seem ordinary, such as attending frequent meetings with a probation officer and performing community service.[108] But they also often include attending school, abiding by a curfew, and obeying parents or guardians.[109] Breaking any rule can trigger harsh sanctions, including incarceration.[110] Yet studies show that children’s brains are not fully developed.[111] The pre-frontal cortex—the part of the brain that is responsible for temporal organization of behavior, speech, and reasoning—continues to develop into early adulthood.[112] This makes it harder for children to manage their emotions and behaviors, and makes them more likely to make impulsive, short-sighted decisions and to succumb to peer pressure.[113] As a result, many children break the rules of their supervision, and substantial numbers of them end up incarcerated.[114] Nationwide in 2017, 42,632 children were confined in some type of detention facility—15 percent, or 6,420 of them, for probation rule violations.[115] Children of color are disproportionately impacted. As of 2017, children of color comprised 46 percent of the US population aged 10 to 17,[116] but constituted 55 percent of all juvenile probation dispositions and 67 percent of all children confined for rule violations.[117] Increasingly, some states are reforming their juvenile probation systems by reducing the use of probation and limiting punishments for violations. Instead, these states reward positive behavior and invest in family and community-based supports.[118] |

Vague and Unreasonable Conditions

Rules in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania frequently prohibit people from drinking alcohol or entering bars—in some cases, even when their offenses did not involve drinking.[119]

In Georgia, courts can require people to stay out of entire counties altogether, known as “banishment” provisions, reminiscent of an ancient era.[120]

Many conditions are vague.[121] For instance, in Wisconsin, a standard condition of probation includes: must “avoid all conduct . . . which is not in the best interest of the public welfare or your rehabilitation.”[122] In Georgia everyone under probation must “avoid injurious and vicious habits.”[123]

Many of the people we spoke with said these rules make them nervous to even leave their homes—especially in communities where many people have criminal records and police are a constant presence.[124] Given that one in three Black men have a criminal record—compared with one in 12 people in the general US population—this burden falls particularly hard on Black men.[125] Toriano Goldman, a Black man who served probation in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, explained, “Every time I’m in a car, I’m paranoid about who’s in it—are they a convicted felon? Will this lead to a revocation?”[126] He continued, “I’m from a poor area. Everyone where I live has a criminal background, so where am I supposed to go? It’s impossible to socialize.”[127]

Program Requirements

Another common condition is completing certain types of programs, such as substance use treatment if the underlying offense is drug-related, or anger management programs if, for instance, someone was convicted of assault.[128] These programs can be outpatient, inpatient, or even based within jails and prisons.[129]

Programs can create their own barriers to rehabilitation. In many cases, for example, people must pay for these programs themselves. Anger management courses in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, cost $45 per class plus a $100 intake fee.[130] A violence prevention program in Lehigh County, in southeastern Pennsylvania, costs $240.[131] As Philadelphia Judge Karen Simmons acknowledged, unaffordable fees can lead people right back to court for “failure to pay” violations.[132]

Further, violating any rule of the program is itself a supervision violation. Program rules can be wide-ranging and harsh. Pennsylvania’s Gaudenzia Siena House—an in-patient drug treatment program—prohibits, among other things, “coarse joking or gesturing;” wearing torn clothing; and watching television outside of the specified “news hour.”[133]

Rules are also often subjective: to complete a Milwaukee, Wisconsin, prison-based cognitive behavioral program, people must “actively participate in groups, satisfactorily complete all homework assignments, and demonstrate they have acquired the specific skills taught in the program.”[134] Further, when programs are based inside jails and prisons, people must comply with the correctional facility’s rules.[135] If people violate any of the program or correctional facility rules, they face revocation and incarceration.

As discussed in Section IV, “Sentences to Treatment Programs,” we spoke with multiple people who were kicked out of prison-based treatment programs and incarcerated, sometimes for long periods of time, based on subjective determinations that they did not engage adequately with their treatment program.

Studies show that people who participate in programs through probation are more likely to have their supervision revoked than people who do not participate in these programs.[136] Experts attribute this result to the fact that people who participate are more closely watched, thus giving authorities more surveillance, and more opportunities to detect violations.[137]

Conflicting and Expansive Conditions

Conditions often conflict with each other, for example, requiring people to hold down jobs while also requiring them to attend frequent meetings and treatment programs—typically held during standard work hours.[138] Many people, including some with whom we spoke for this research, reported that supervision interfered with their ability to hold down a job.[139]

Typical supervision conditions also include expansive search provisions, requiring people to submit to searches at any time, in any place, and without a warrant.[140]

Supervision conditions generally require people to frequently report to an officer—monthly, biweekly, or even weekly.[141] We spoke with many people who had to travel upwards of an hour from their home to the supervision office.[142] For example, Romelo Booker explained that he had to take three buses, taking an hour and a half each way, to get to his weekly supervision appointments in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[143]

Many judges and supervision officers interviewed for this report said the conditions placed on people during supervision ensure people get needed services, such as job training, education, and treatment, that they believe will stop them from committing crimes.[144] “I know defendants just want to get out [of jail without conditions] but that doesn’t address the root of the problem,” Lowndes County, Georgia, Judge John Edwards said, explaining why he imposes conditions such as substance use treatment.[145]

Increasingly, supervision departments are reforming their policies and practices to better address peoples’ unique needs—for instance, asking people what services would be useful, or holding meetings in their communities rather than the supervision office, supervision officers said.[146] However, these reforms take time to fully implement, they said.[147] Also, neither supervision officers nor courts usually have significant expertise in addressing people’s health, drug treatment, or other needs.[148] “I didn’t go to school to be a social worker or a teacher, so I don’t have a lot of the background” necessary to connect people with services, said Matthew Ours, a supervision officer in Rock County, Wisconsin, south of Madison.[149] The vast majority of people on supervision interviewed for this report said they did not receive meaningful support from their supervision officers.

Some judges and supervision officers recognize that, given the vast and often irrelevant conditions imposed, supervision frequently sets people up to fail.[150] “I don’t want to say it’s designed to set [people] up for failure . . . but it seems like it comes out that way, keeping them on that tightrope,” said a Supervision Officer in Dodge County, Wisconsin.[151] Philadelphia Judge Simmons reflected that, if she had to report to a judge every week for years on end, she would probably fail at some point. “[T]he odds are that I’m probably gonna do something [wrong], because I’m not perfect.”[152] Similarly, Georgia Department of Community Supervision (DCS) Commissioner Michael Nail admitted, “I’m not sure I’d make it under probation with all these conditions.”[153]

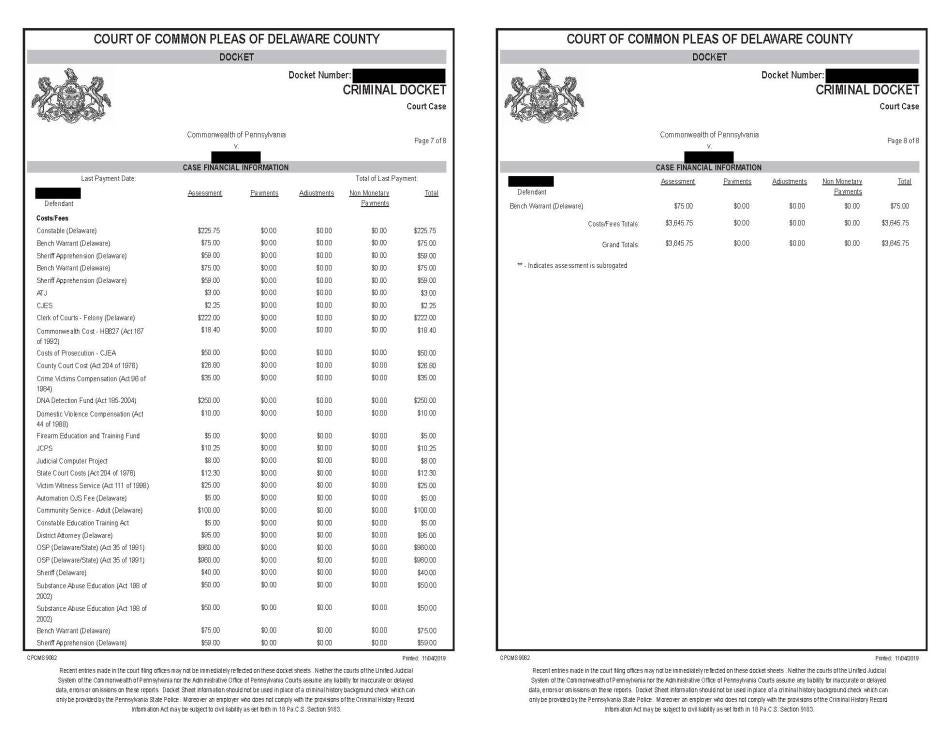

High Costs

Supervision is expensive. Criminal convictions already carry fines, fees, and restitution costs that can easily total thousands of dollars.[154] On top of this, just being on supervision each month costs the person under supervision $20-60 in Wisconsin,[155] $30-49 in Georgia,[156] and $25-65 in Pennsylvania.[157] Electronic monitoring in Wisconsin can cost up to $700 per month.[158] In Sullivan County, in rural northern Pennsylvania, probation can require routine drug testing and each test costs $30.[159] In Dodge County, Wisconsin, north of Milwaukee, a drug and alcohol treatment assessment costs $250.[160] In addition, 43 states, including Georgia and Wisconsin, charge poor people a fee to cover part of the costs of court-appointed lawyers, ranging from $10 in California to $500 in parts of Georgia.[161]

While these fees may appear small in isolation, they regularly total hundreds or even thousands of dollars.[162] Over the last decade in Pennsylvania, the median court costs owed for individuals represented by public defenders, meaning they had limited financial means, was nearly $1,110—on top of fines and restitution.[163]

In Georgia, courts can impose “pay-only” probation, meaning people are under probation solely because they cannot pay their fines and surcharges.[164] As of 2017, over 36,000 people in Georgia were on pay-only probation.[165]

Implications of Court DebtCourt debt carries serious consequences. For instance, 43 states suspend drivers’ licenses over unpaid court costs.[166] Across much of the United States, where public transportation is nonexistent or unreliable, losing a license means losing the ability to report for supervision meetings. It also makes it harder to get to work—and thus pay off debt.[167] Additionally, rather than keeping people on supervision for failing to pay, some courts transfer unpaid court debt to a civil judgment. While freeing people from supervision’s requirements, these judgments can damage peoples’ credit scores, making it more difficult to obtain loans or lines of credit for housing, cars, or education, for example.[168] In many states, court debt can also cost people the right to vote.[169] These barriers add to the already steep consequences people face as a result of criminal convictions, which can include further bars on the right to vote and the ability to obtain jobs, professional licenses, student loans, housing and other public assistance, along with potential immigration consequences.[170] |

Few Resources

Navigating supervision conditions requires financial security, stable housing, reliable transportation, and, often, access to quality healthcare and mental health services. Yet as discussed in Section VI, “Poverty,” people on supervision typically struggle to access these resources.

Supervision departments are supposed to connect people to these resources.[171] Many supervision officers we interviewed in Wisconsin and Georgia said they consider this a vital part of their job, and described increased efforts in recent years to connect people with housing, education, and other support.[172] People on supervision “need homes, they need jobs, they need stability . . . If we’re not offering . . . quality [resources] then we’re really not helping them, all we’re doing is just perpetuating a cycle,” said senior Lowndes County, Georgia, Supervision Officer Melanie Hasty.[173]

Yet across all three focus states, supervision officers, judges, and attorneys largely agree that there are not enough resources to meet peoples’ needs.[174] While the number of people under supervision has soared over the last half century—leading to average caseloads nationwide of above 100 supervisees per officer[175]—the resources for community programs that provide assistance with housing, jobs, and health care have not kept up with the need for them, particularly in rural areas.[176]

Further, according to leading experts on supervision practices, many supervision departments prioritize enforcing conditions over providing resources.[177] Niel Thoreson, Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s chief supervision officer, said that, while his office balances the “sometimes paradoxical responsibilit[ies]” of protecting the public and providing services, “the public safety piece [is] our principal concern.”[178] Wisconsin’s supervision system “is much more about making sure someone isn’t breaking the law than it is about making sure that they’re building a productive or healthy life or actually getting rehabilitated,” said Wisconsin State Representative Evan Goyke.[179] Supervision experts trace this focus, at least in part, to officers’ worries that they will get in trouble if someone commits another crime during supervision. “You only hear about the individuals on probation and parole when they mess up,” Marc Alstatt, a senior Chatham County, Georgia supervision officer, explained.[180] Experts also trace this to high caseloads, and note that enforcement is less time consuming than finding the right set of services for a particular person’s needs.[181]

While a few people we interviewed reported receiving some helpful programming, the vast majority of people we spoke to—along with supervision experts—said that supervision provided little support.[182] “They just gave us a sentence and put us on the street with nothing and expect us to follow rules and make stuff happen,” described Robert Sanders, a 29-year-old man who has been in jail or on probation in Wisconsin since age 17.[183]

Many people reported that, during required meetings, their supervision officers did little to inquire about how they were managing or offer any help. Instead, the officers simply administered drug tests, monitored whether they were employed, and asked if they had been making their required payments.[184] Sarah Martin (pseudonym for last name), a Pennsylvania woman who said she has spent decades on probation due to her longstanding substance use disorder, told us, “Probation officers have never done anything for me . . . They’re there to catch you doing something wrong. They have no resources, no nothing.”[185]

Some people are able to find help and support outside of supervision through community-based organizations, often led by people who have been involved in the criminal legal system.[186] “Nothing the [criminal legal] system did helped me do what I did today,” said Josh Glenn, who spent years on probation and in jail in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for drug-related charges beginning at age 13 before co-founding an organization, the Youth Art and Self-Empowerment Project (YASP) dedicated to helping young people involved in the criminal legal system. “Connecting with community leaders, YASP cofounders, that’s what helped.”[187]

Pleas to ProbationBecause courts often offer probation as an alternative to a sentence that involves incarceration, many people plead guilty to sentences carrying lengthy probation terms without fully understanding the risks involved. Those detained pending trial face particularly strong pressure to plead to probation so that they can get out of jail.[188] By March 2015, Willie White, a middle-aged Black father of seven, had spent six months in a Lowndes County, Georgia, jail, in south central Georgia, waiting for his trial.[189] Eager to get home to his family, White pled guilty to possession of marijuana with intent to distribute in exchange for 10 years of felony probation.[190] Probation would allow White to avoid more incarceration in the short term, but it would also require him to obey a series of rules, including paying all court costs—in his case, a $2,500 fine, $550 in court-appointed attorney fees, a $32 monthly supervision fee, and a $50 crime lab fee—staying away from drugs and alcohol, and completing 120 hours of community service.[191] Less than three months after White pled guilty, he was back in jail for failure to pay his court costs. The judge imposed a five-day jail term, and then released White to continue serving his probation term.[192] In 2017, White picked up another case for several traffic infractions, to which he pled guilty and was sentenced to a separate one-year probation term.[193] In October 2018, White tested positive for marijuana, and his misdemeanor probation officer warned him that the judge would likely send him to jail. Scared, White stopped reporting, he said. Then in October 2019, as White was riding his bicycle, Lowndes County police arrested him for possessing marijuana and a pill capsule that White says contained a lawful substance. White’s probation officers pursued revocation for possessing drugs, along with failure to report, the positive marijuana test, and a failure to complete community service.[194] The officers lodged a detainer, meaning that White had to remain in jail while contesting the revocation and the drug possession charges. When we met White in the Lowndes County jail in December 2019, he had already been held for nearly three months. He told us that probation has only made his life worse: “They took all my money, kept me incarcerated for simple little mistakes. It’s really been a lot of pain.” |

II. Conduct Triggering Violations

There’s a real problem with . . . rule violations. Who doesn’t come late or miss appointments or just has a bad day? Nobody should be going to prison for that, nobody.[195]

—Caliph Muab-El, formerly incarcerated for supervision violations in Wisconsin

This boy just keeps going back to jail, back to jail, back to jail. He don’t never be out a whole year. He missed Christmas, he missed the holidays, [he] miss[ed] all of that.[196]

—Aisha Edwards, whose fiancé, Rashad Yearby, has been repeatedly incarcerated for probation violations in Georgia

A wide range of conduct, such as failing to report to supervision officers when required, failing to inform them that you have moved, or failure to be truthful, can lead to incarceration.

Supervision officers say they generally give people multiple chances before pursuing revocation. But since root causes of the violations, discussed in Section VI, often go unaddressed, many people continue to engage in the same behavior, ultimately leading to incarceration.

Irregularities in EnforcementEnforcement practices can vary widely among supervision officers, both between and even within supervision departments. For instance, some officers disregard low-level violations, while others initiate sanctions for any misstep.[197] In many cases, people have multiple supervision officers over the course of their supervision term, meaning they may face sanctions one day for conduct that their previous officer regularly ignored.[198] |

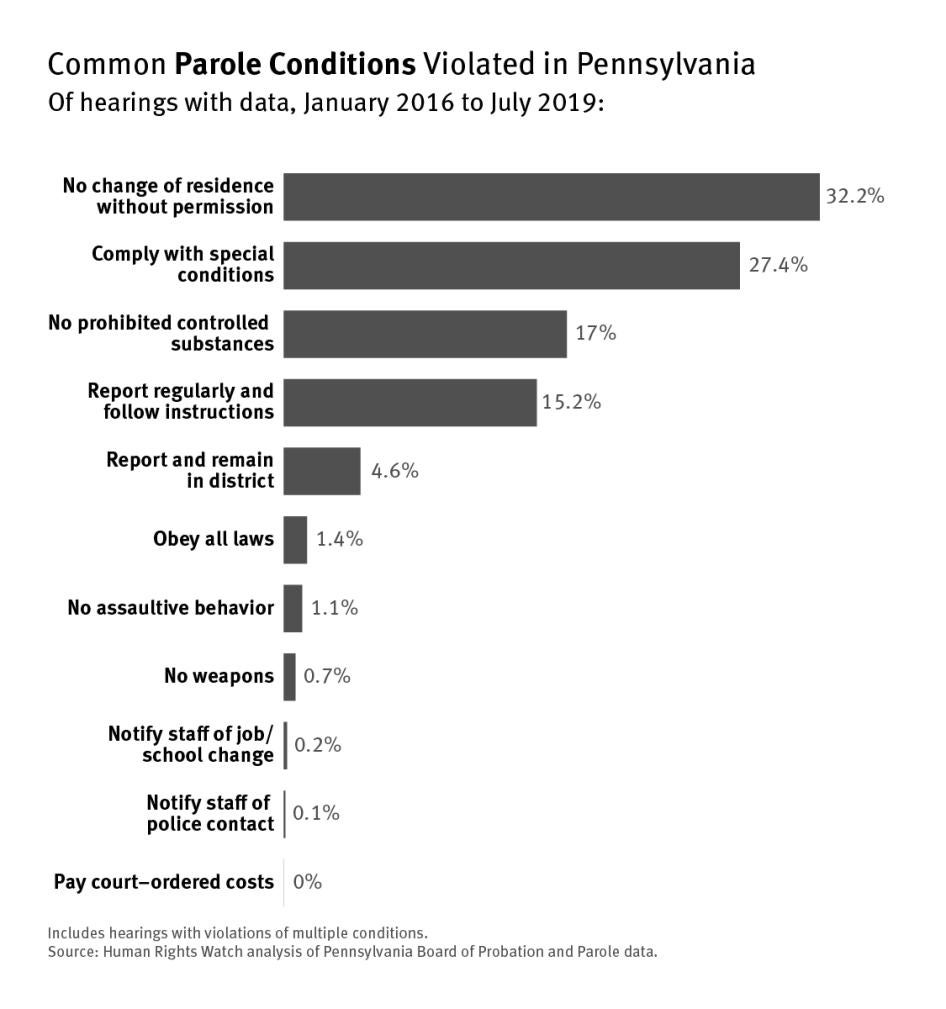

In order to assess the types of conduct that generally leads to supervision violations, Human Rights Watch analyzed supervision violation records provided by agencies in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin as well as jail booking data obtained through publicly available Georgia jail rosters (see “Methodology” section above).

Pennsylvania

Changing residences without permission was the single largest condition that led to state parole violation proceedings in Pennsylvania from 2016 to 2019, accounting for about one third of all violations.[199] Other common violations included violating a “special” condition—which includes conduct such as failing court-mandated programs and drinking alcohol—(27 percent) and using or possessing drugs (17 percent).[200]

Wisconsin

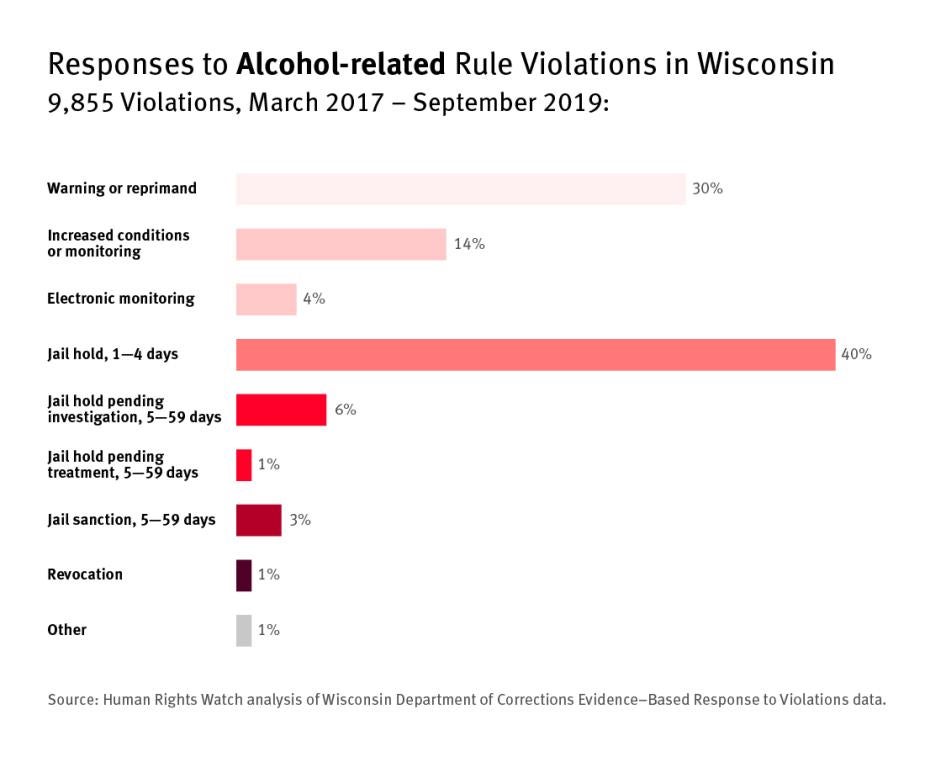

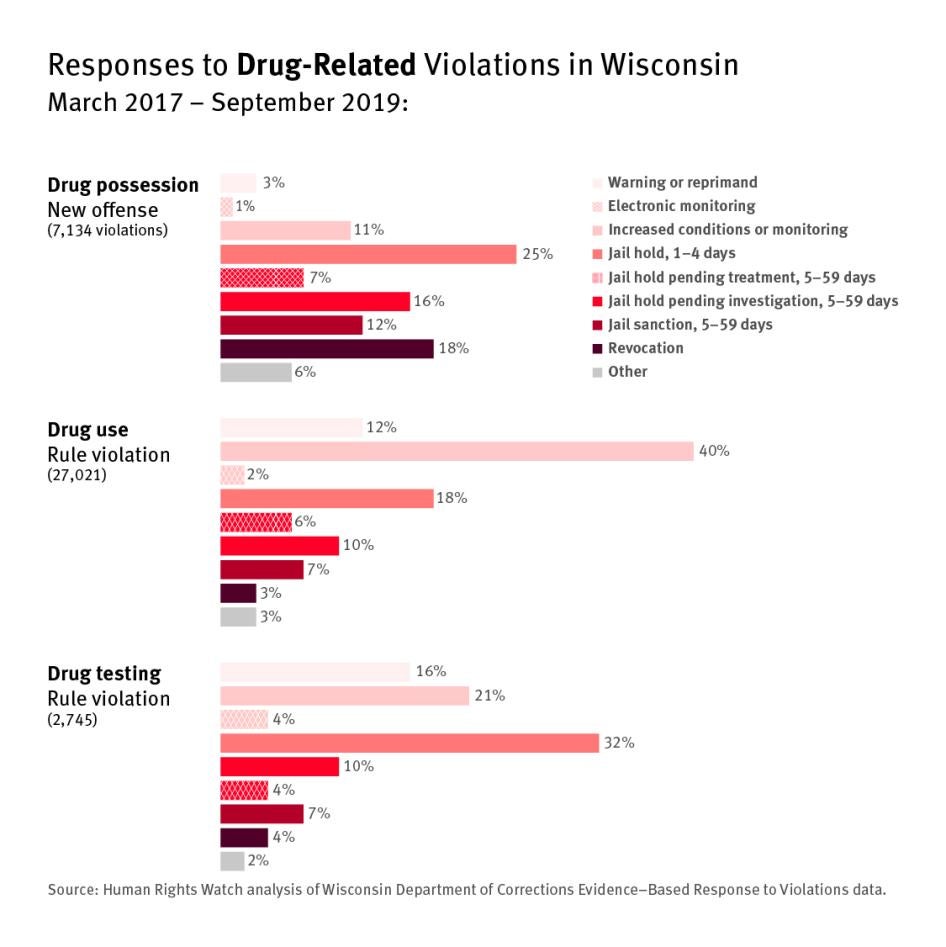

In Wisconsin from 2017 to 2019, drug use was by far the most common violation leading to sanctions up to and including incarceration—accounting for one out of every five violations during that period, or 27,000 violations.[201] The most common rule violations that led to incarceration were drug use (11 percent of all violations leading to incarceration), using alcohol or entering bars (6 percent), and violating mandated treatment rules (5 percent).[202]

Where people were incarcerated for new offenses, most (11 percent of all violations leading to incarceration) were public order-related, largely for disorderly conduct, resisting arrest, or “bail jumping”—meaning violating the conditions of pre-trial release.[203] Others were for assaultive conduct (8 percent), the vast majority of which were misdemeanor-level offenses,[204] drug possession (6 percent), and property or theft offenses (6 percent).[205]

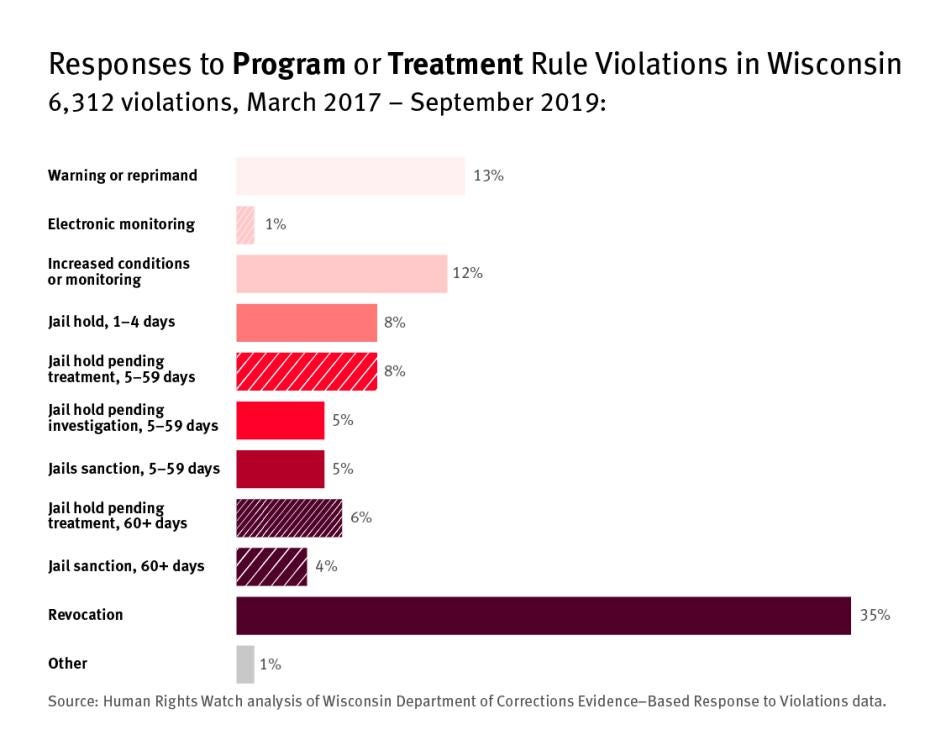

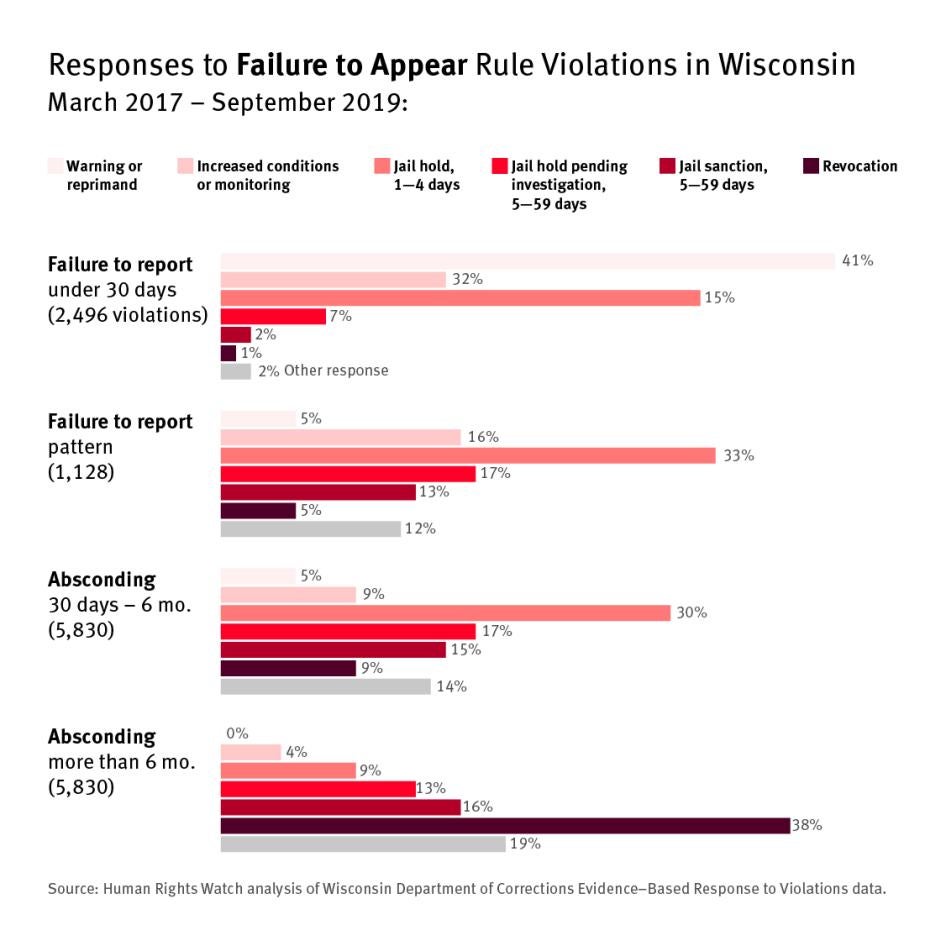

We analyzed the sanctions that resulted from different violations. Sanctions included additional conditions; electronic monitoring; jail sanctions of one to four days, five to 59 days, or 60 days or more; and revocation. Certain conduct, such as using alcohol or drugs, typically led to a few days in jail, while other conduct, like violating rules of mandated programs and failure to appear or “absconding” (described later in this section), more often led to revocation—which, as explained in Section IV, “Sentencing for Violations,” could mean significant time in prison.

|

Incarceration for Common Violations in Wisconsin |

|||||

|

Type |

Category |

Number of violations |

Total percentage of violations |

Percentage of violations resulting in incarceration (jail/prison) |

Percentage of violations resulting in revocation |

|

Rule violation |

Drug Use |

27,327 |

20% |

11% |

3% |

|

New offense violation |

Public Order |

11,400 |

8% |

11% |

11% |

|

Rule violation |